Yang Yongliang

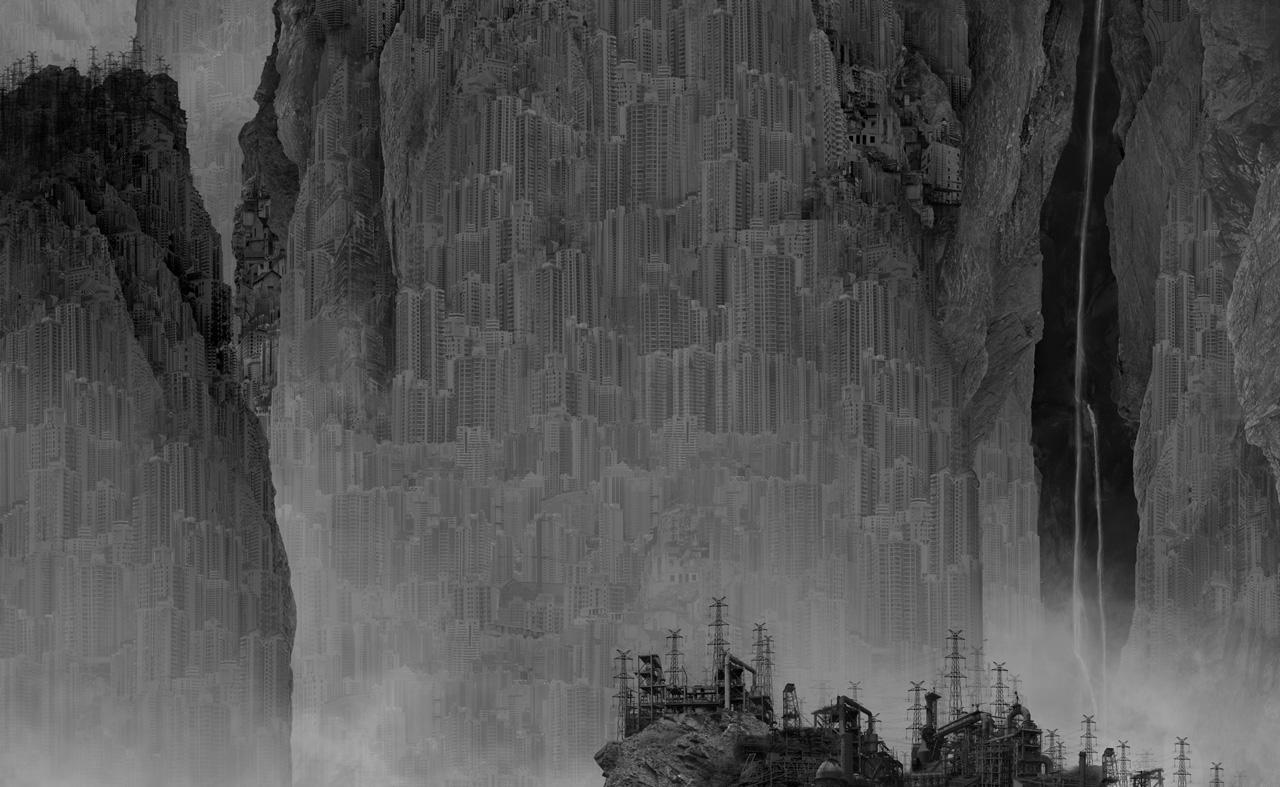

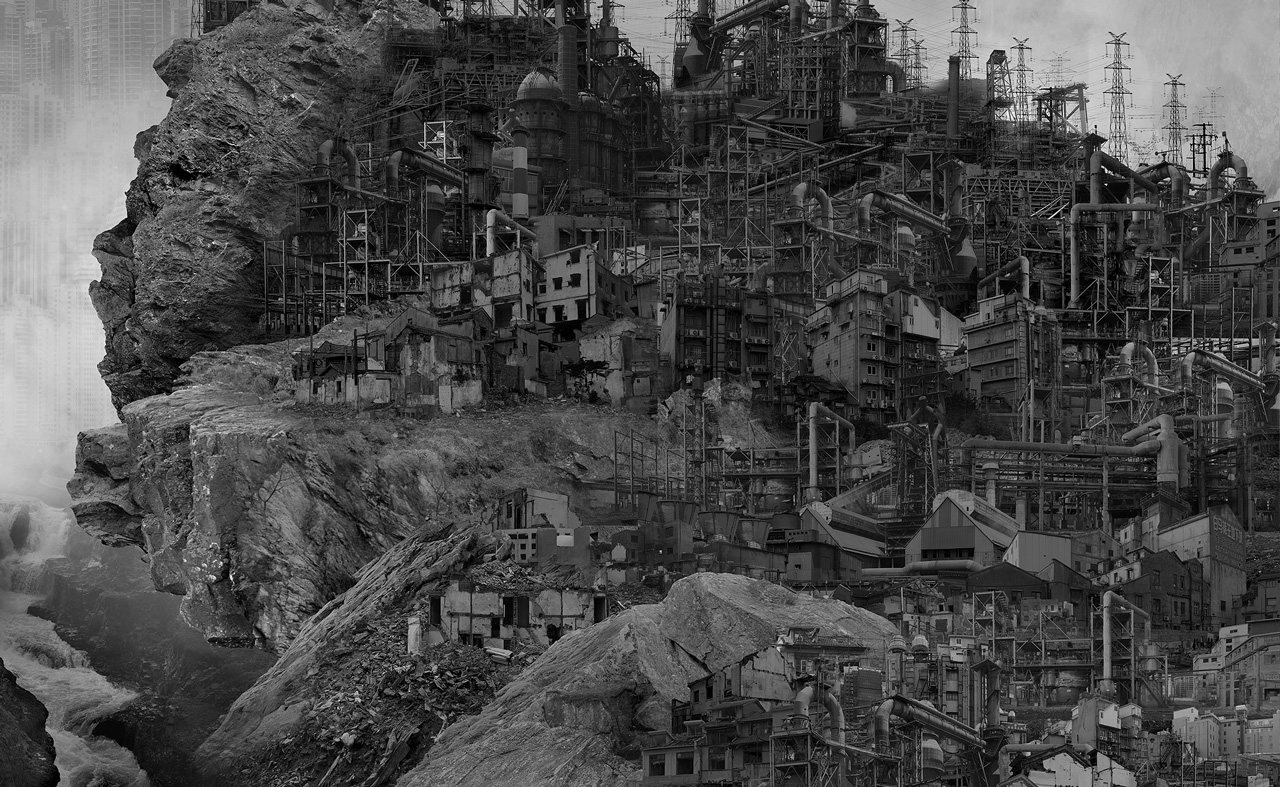

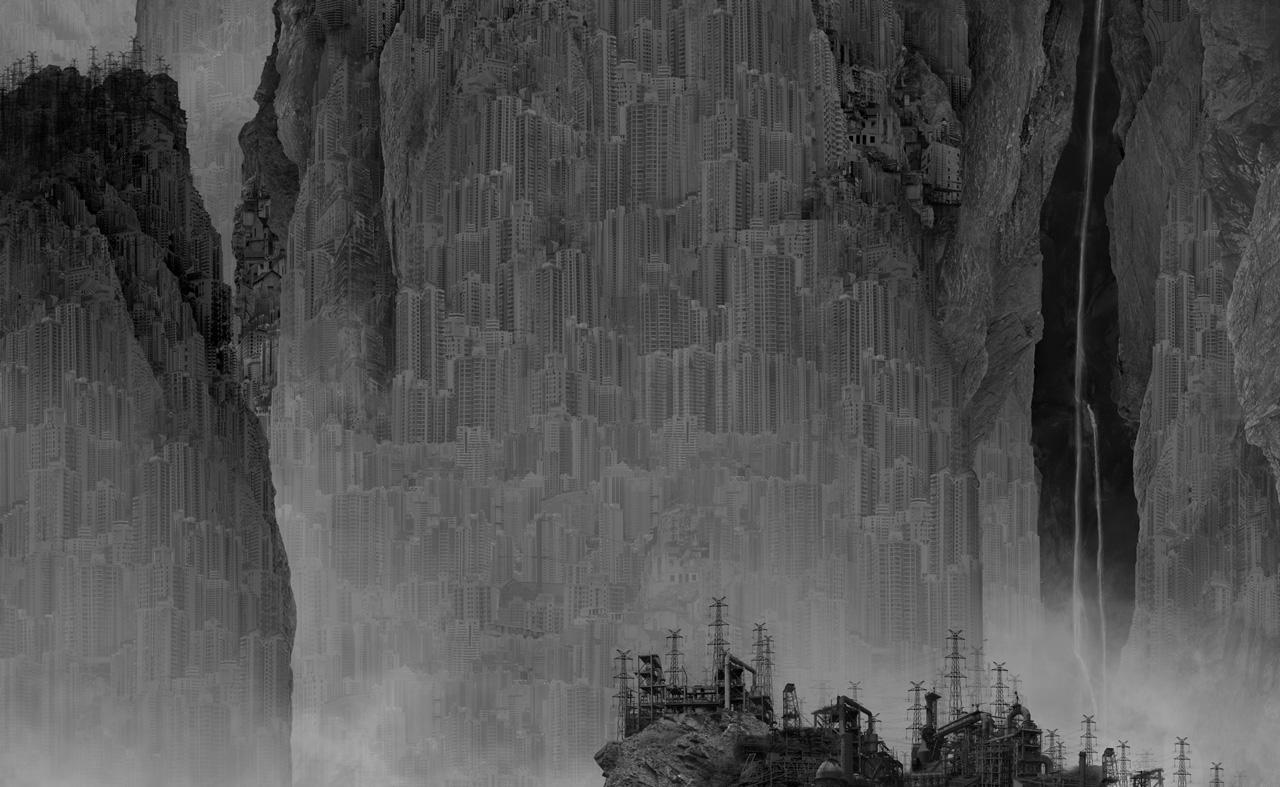

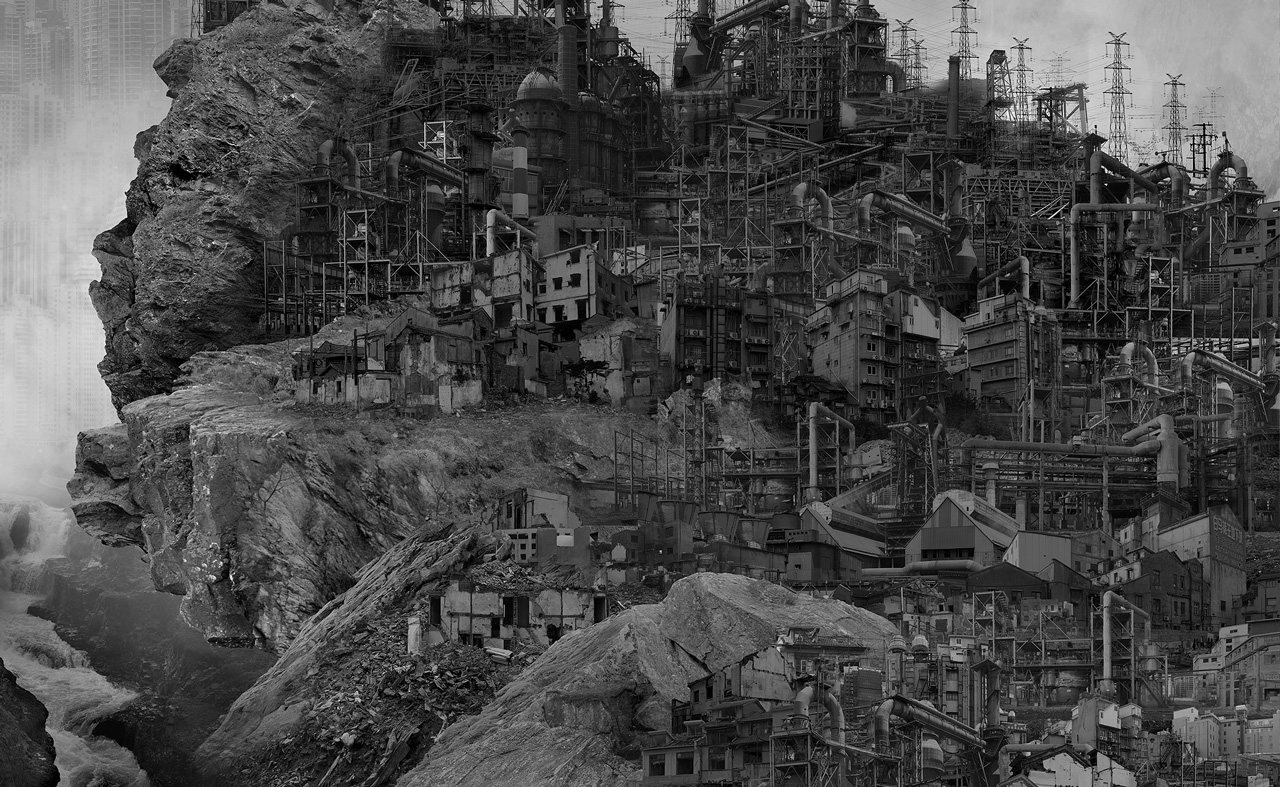

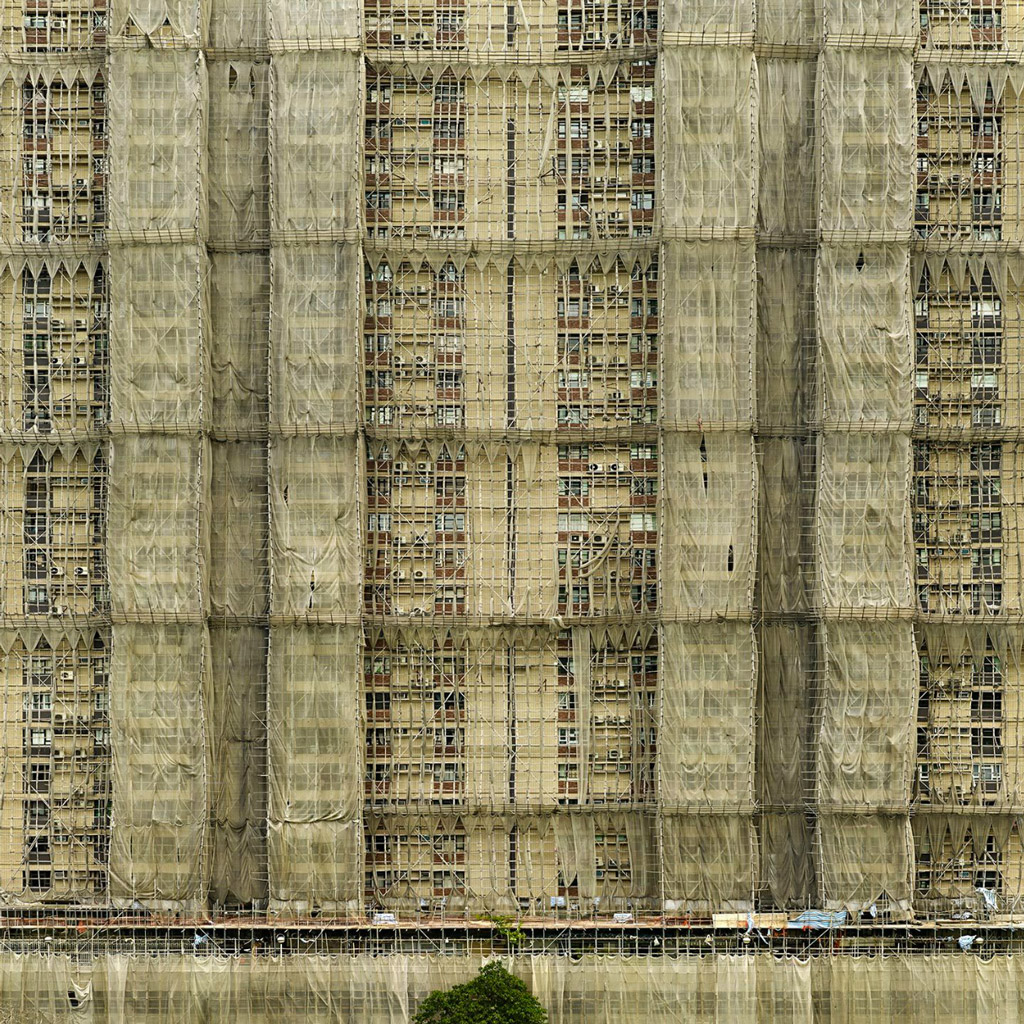

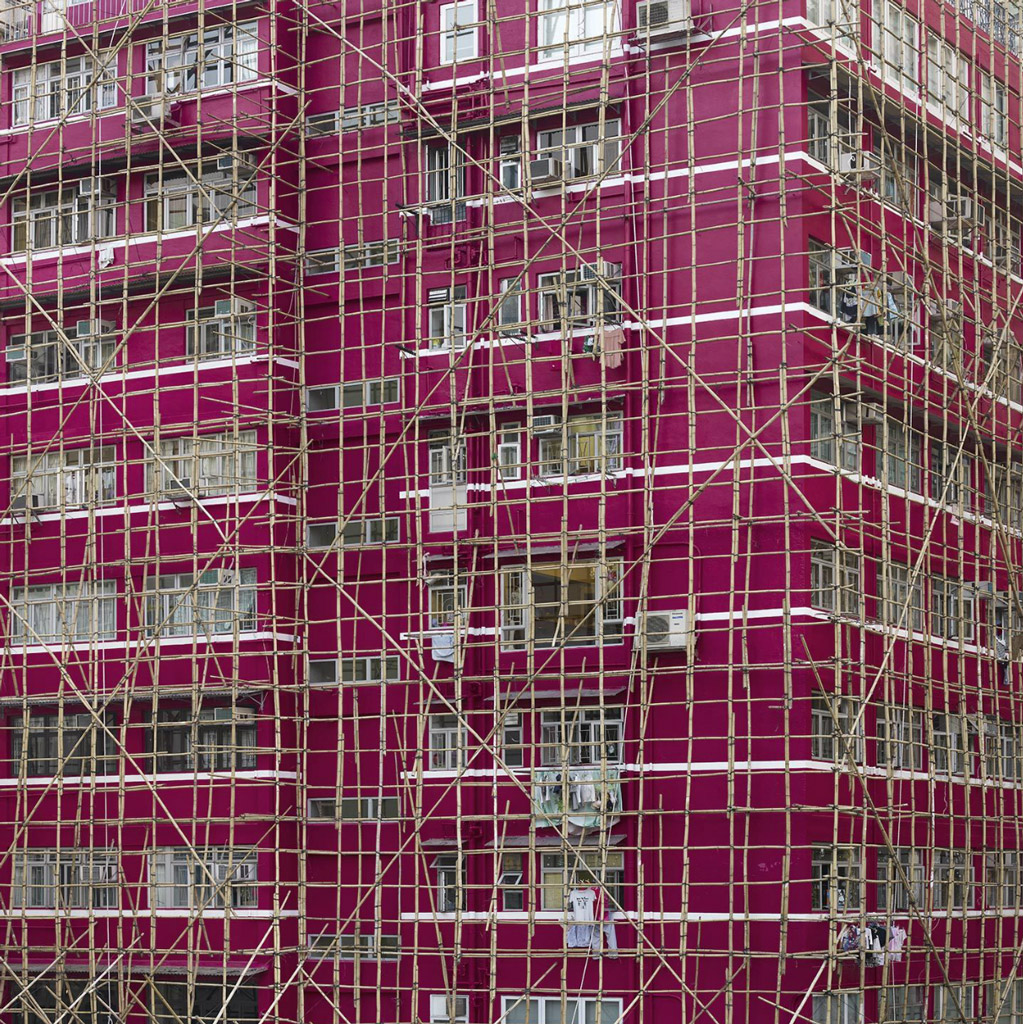

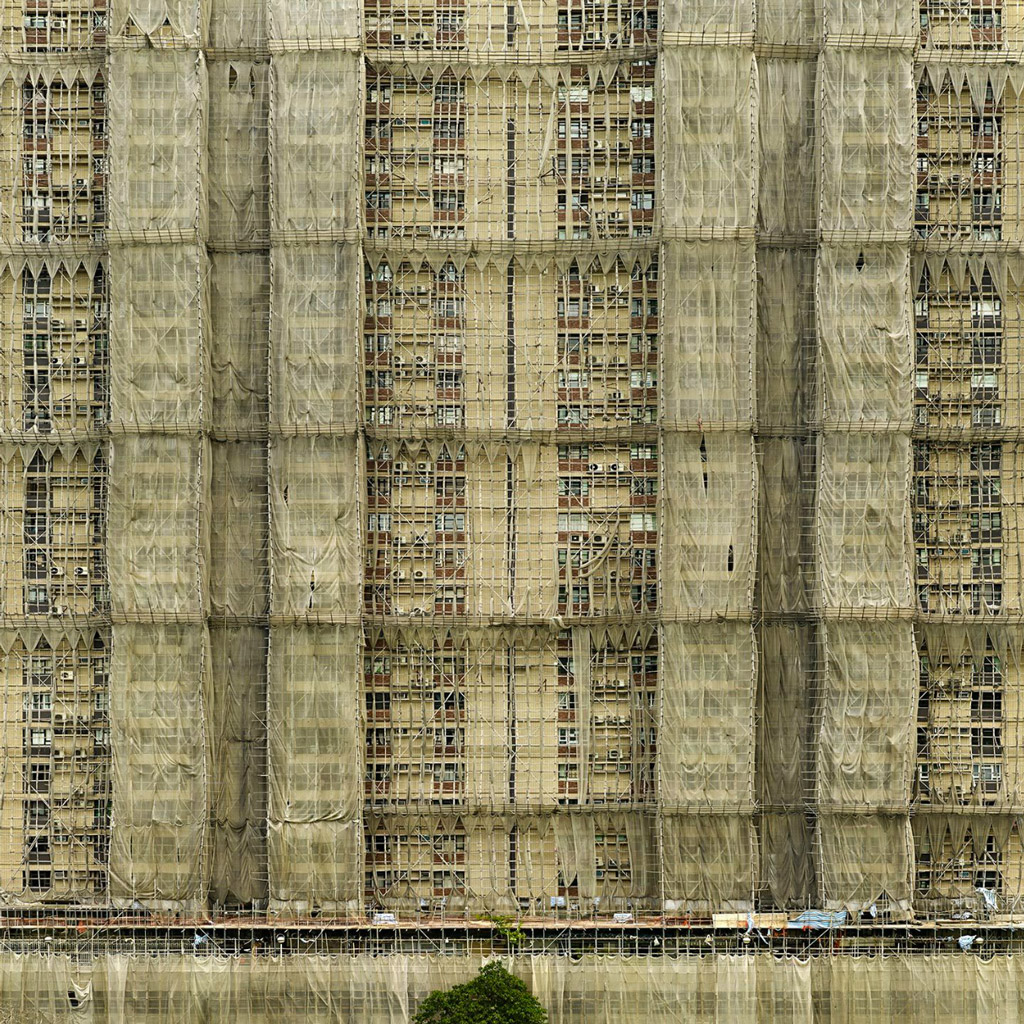

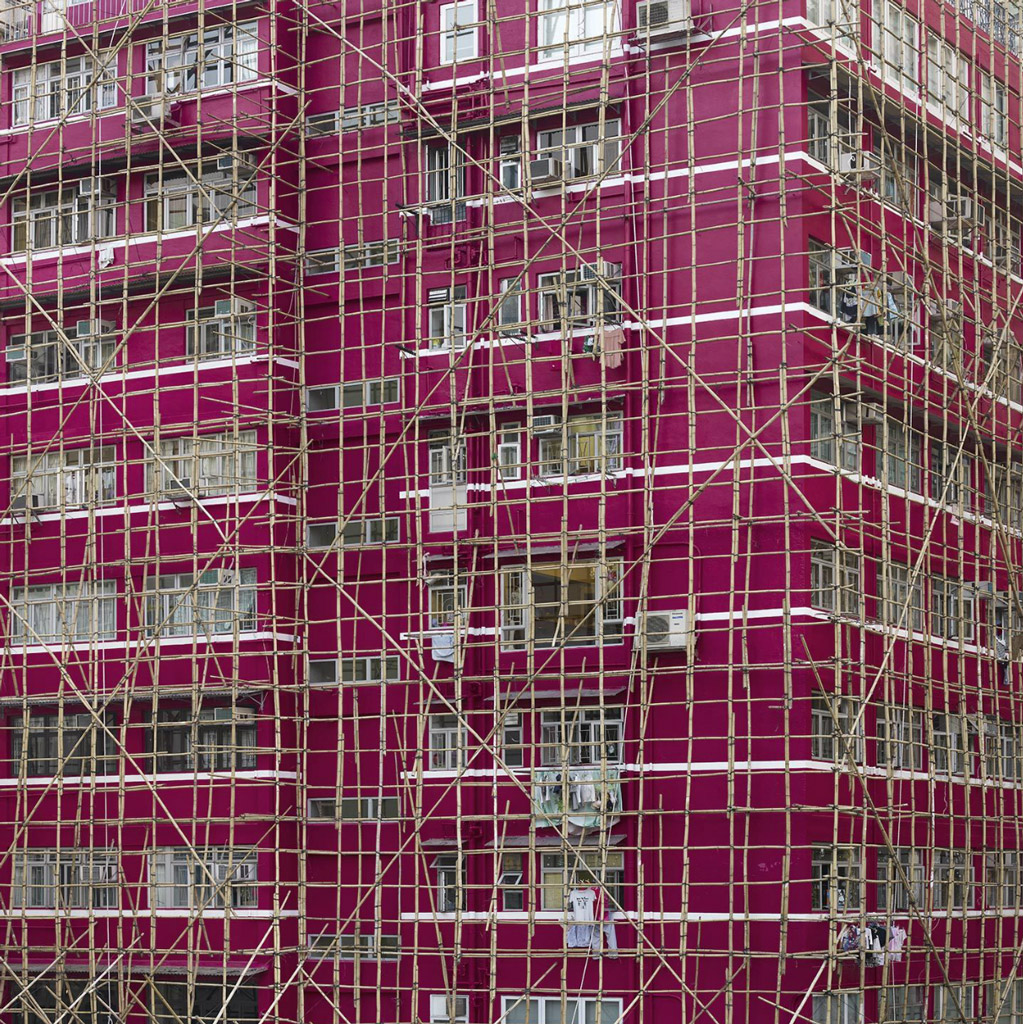

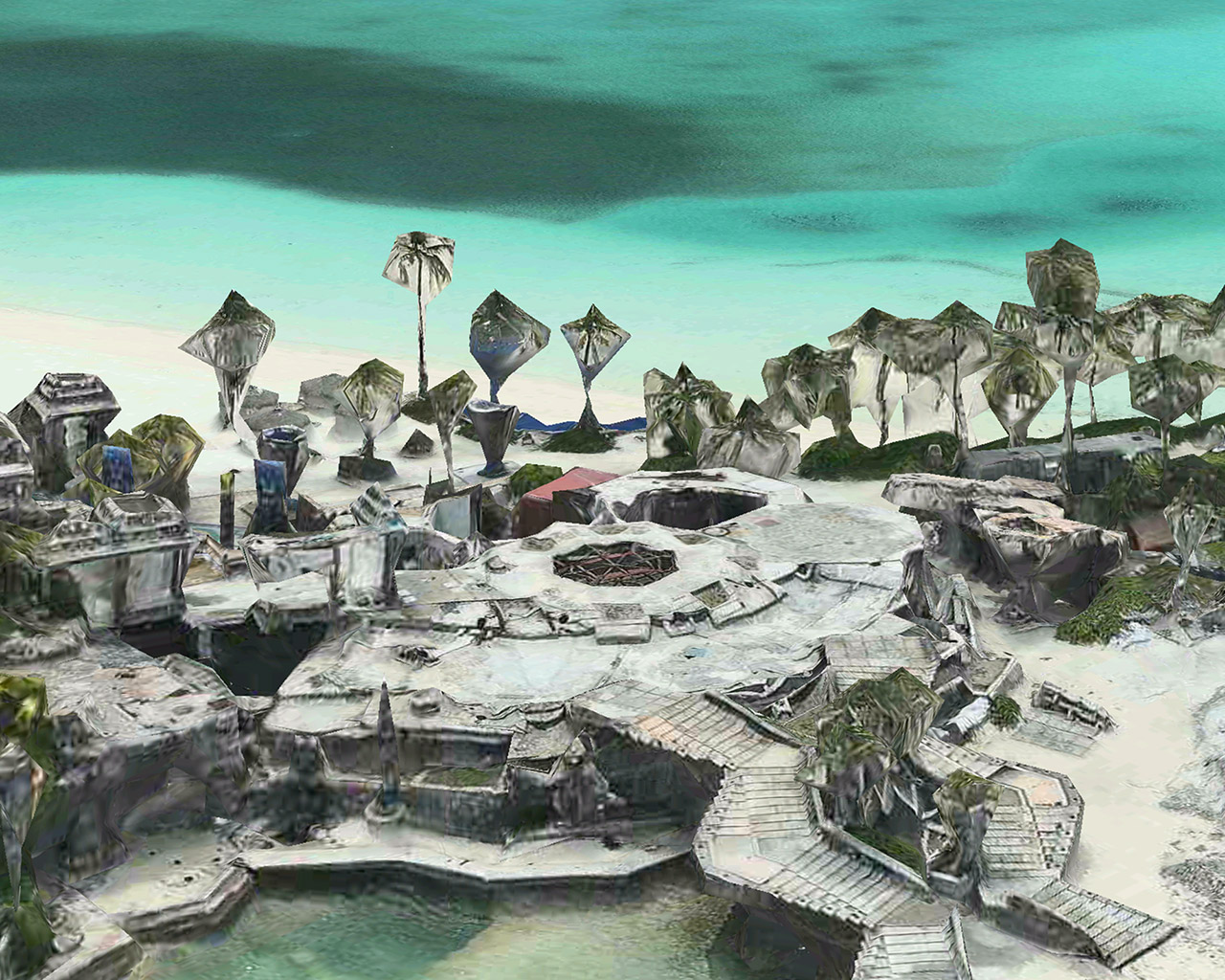

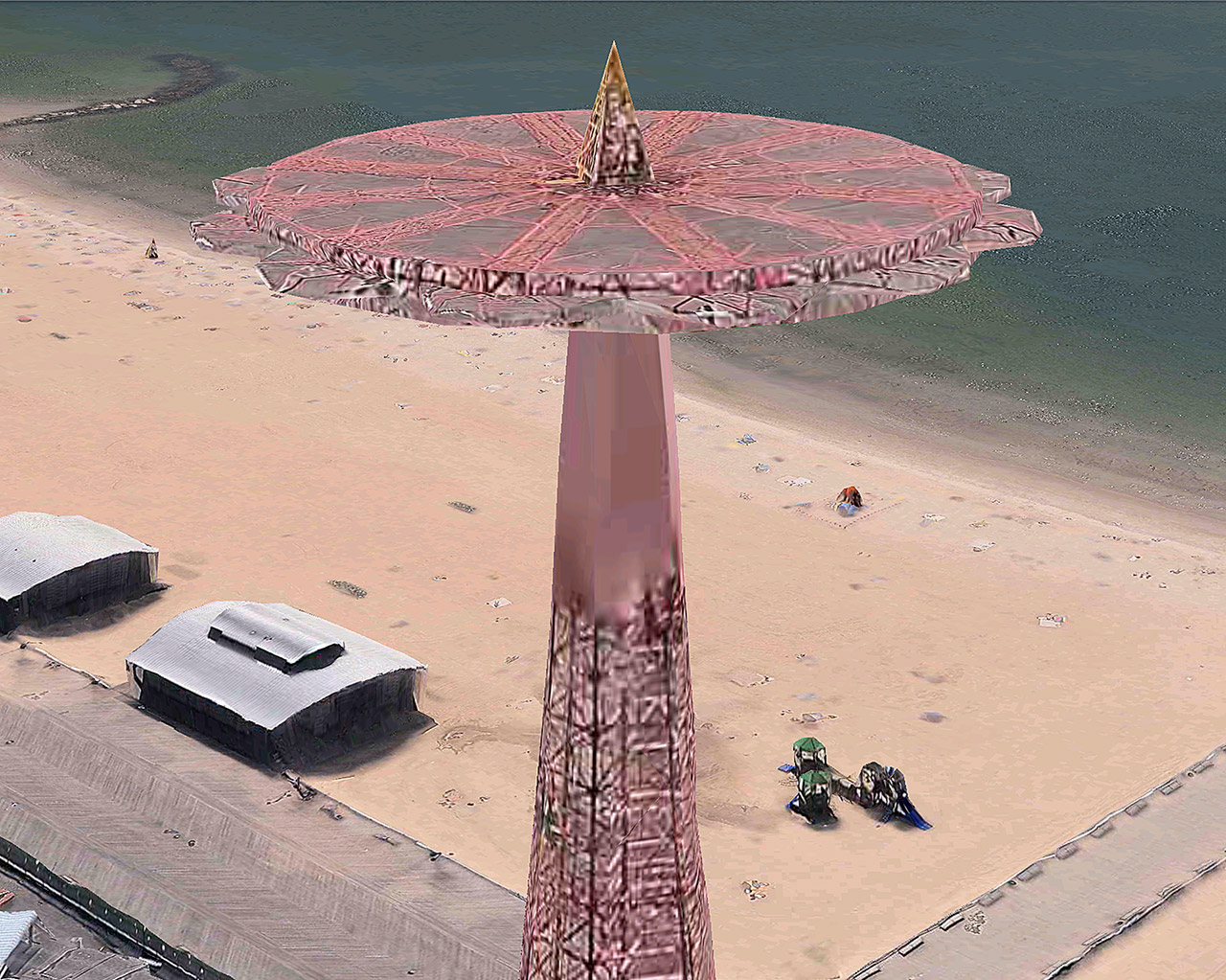

Artificial Wonderland is a series started in 2010. Yang Yongliang uses images of architecture as brushstrokes; heavy mountain rocks with enriched details draw a faithful reference to Song Dynasty landscape painting. Urban development makes life in the city flourish, but it also imprisons these lives; centuries-old cultural tradition in China is profound, but it has also remained stagnant. Ancient Chinese people painted landscapes to praise the greatness of nature; Yang's works, on the other hand, lead towards a critical re-thinking of contemporary reality.

In Artificial Wonderland II (2014), there are digital replicas of two Song Dynasty master paintings, namely Travelers Among Mountains and Steams (Fan Kuan) and Wintery Forest in the Snow (anonymous). Whereas ancient landscapes are often seen as being without time, Yang's interpretation of the latter work is a nocturnal image, titled Wintery Forest in the Night. The 2014 series marks a step forward in terms of digital technique--the piece is larger than ever and enriched with tremendous detail images. Also, Yang conjucted natural mountain rocks into the signature artificial landscape for the first time. Images of the mountain rocks are mostly taken in Iceland and Norway. In 2015, Artificial Wonderland II was shortlisted in the Prix Pictet – the global award in photography and sustainability.

The Day of Perpetual Night and The Night of Perpetual Day, are two pieces that exemplify a line of recent video work by Yang Yongliang. In them, the traditional landscape extends a narrative between a subtle temporality and diffuse timelessness. With the same rigorous technique that characterizes his still images, in these videos he uses time as a tool to emphasize the paradox of our time: the crossroads between necessary nostalgia, our daily chaos and imagination.

The Night of Perpetual Day. Artwork preview here

The Day of Perpetual Night. Artwork preview here

Yang Yongliang (Shanghai, 1980). He graduated from China Academy of Art in 2003, majored in visual communication. He started his experiments with contemporary art in 2005, and his practice involved varied media including photography, painting, video and installation. Yang exploits a connection between traditional art and the contemporary, implementing ancient oriental aesthetics and literati beliefs with modern language and digital techniques. His work as an expanding meta-narrative that draws from history, myth and social culture, and plays out in the context of the city and its ever-changing landscapes.

Yang Yongliang (Shanghai, 1980). He graduated from China Academy of Art in 2003, majored in visual communication. He started his experiments with contemporary art in 2005, and his practice involved varied media including photography, painting, video and installation. Yang exploits a connection between traditional art and the contemporary, implementing ancient oriental aesthetics and literati beliefs with modern language and digital techniques. His work as an expanding meta-narrative that draws from history, myth and social culture, and plays out in the context of the city and its ever-changing landscapes.

Artificial Wonderland is a series started in 2010. Yang Yongliang uses images of architecture as brushstrokes; heavy mountain rocks with enriched details draw a faithful reference to Song Dynasty landscape painting. Urban development makes life in the city flourish, but it also imprisons these lives; centuries-old cultural tradition in China is profound, but it has also remained stagnant. Ancient Chinese people painted landscapes to praise the greatness of nature; Yang's works, on the other hand, lead towards a critical re-thinking of contemporary reality.

In Artificial Wonderland II (2014), there are digital replicas of two Song Dynasty master paintings, namely Travelers Among Mountains and Steams (Fan Kuan) and Wintery Forest in the Snow (anonymous). Whereas ancient landscapes are often seen as being without time, Yang's interpretation of the latter work is a nocturnal image, titled Wintery Forest in the Night. The 2014 series marks a step forward in terms of digital technique--the piece is larger than ever and enriched with tremendous detail images. Also, Yang conjucted natural mountain rocks into the signature artificial landscape for the first time. Images of the mountain rocks are mostly taken in Iceland and Norway. In 2015, Artificial Wonderland II was shortlisted in the Prix Pictet – the global award in photography and sustainability.

The Day of Perpetual Night and The Night of Perpetual Day, are two pieces that exemplify a line of recent video work by Yang Yongliang. In them, the traditional landscape extends a narrative between a subtle temporality and diffuse timelessness. With the same rigorous technique that characterizes his still images, in these videos he uses time as a tool to emphasize the paradox of our time: the crossroads between necessary nostalgia, our daily chaos and imagination.

The Night of Perpetual Day. Artwork preview here

The Day of Perpetual Night. Artwork preview here

Yang Yongliang (Shanghai, 1980). He graduated from China Academy of Art in 2003, majored in visual communication. He started his experiments with contemporary art in 2005, and his practice involved varied media including photography, painting, video and installation. Yang exploits a connection between traditional art and the contemporary, implementing ancient oriental aesthetics and literati beliefs with modern language and digital techniques. His work as an expanding meta-narrative that draws from history, myth and social culture, and plays out in the context of the city and its ever-changing landscapes.

Yang Yongliang (Shanghai, 1980). He graduated from China Academy of Art in 2003, majored in visual communication. He started his experiments with contemporary art in 2005, and his practice involved varied media including photography, painting, video and installation. Yang exploits a connection between traditional art and the contemporary, implementing ancient oriental aesthetics and literati beliefs with modern language and digital techniques. His work as an expanding meta-narrative that draws from history, myth and social culture, and plays out in the context of the city and its ever-changing landscapes.Ellie Davies

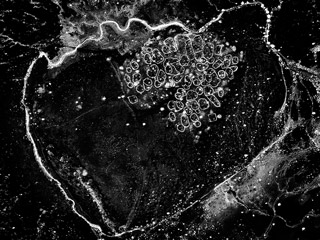

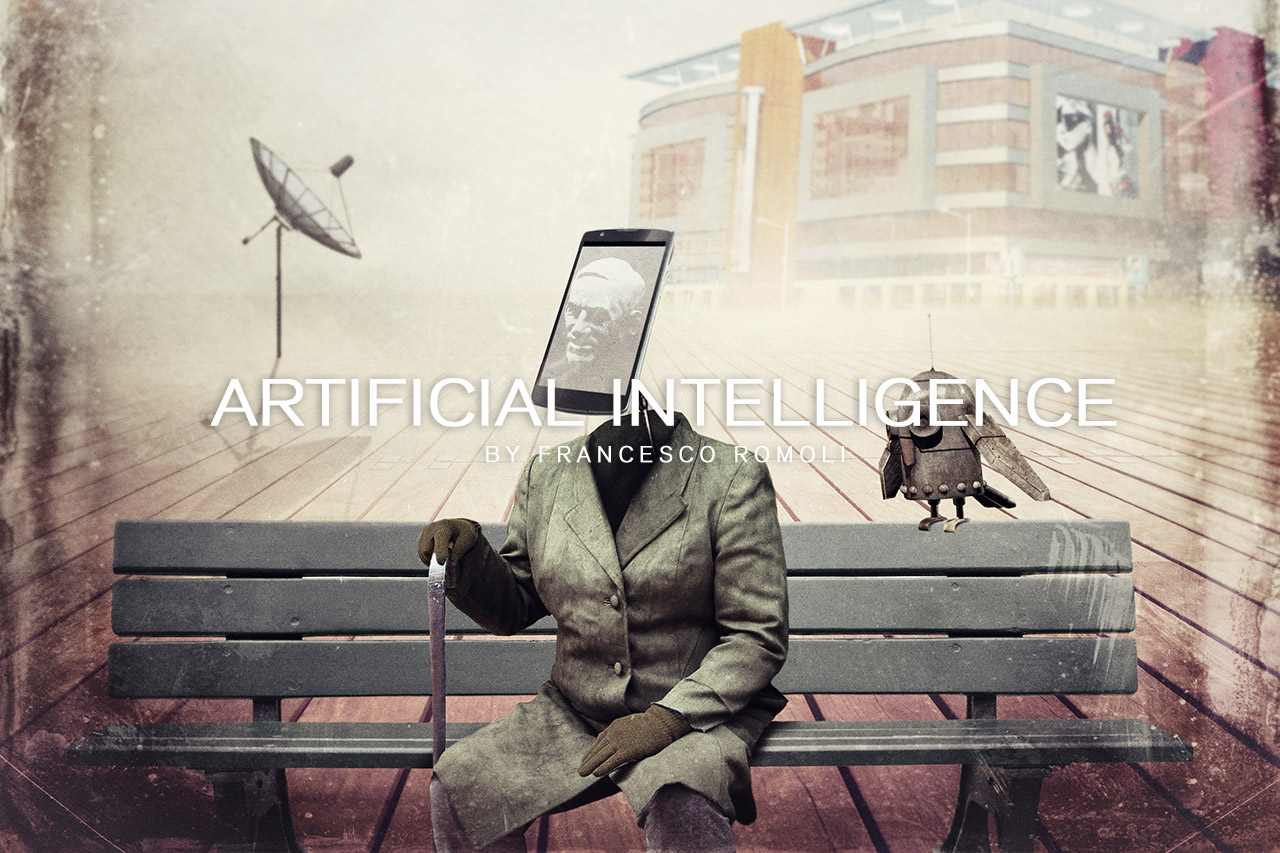

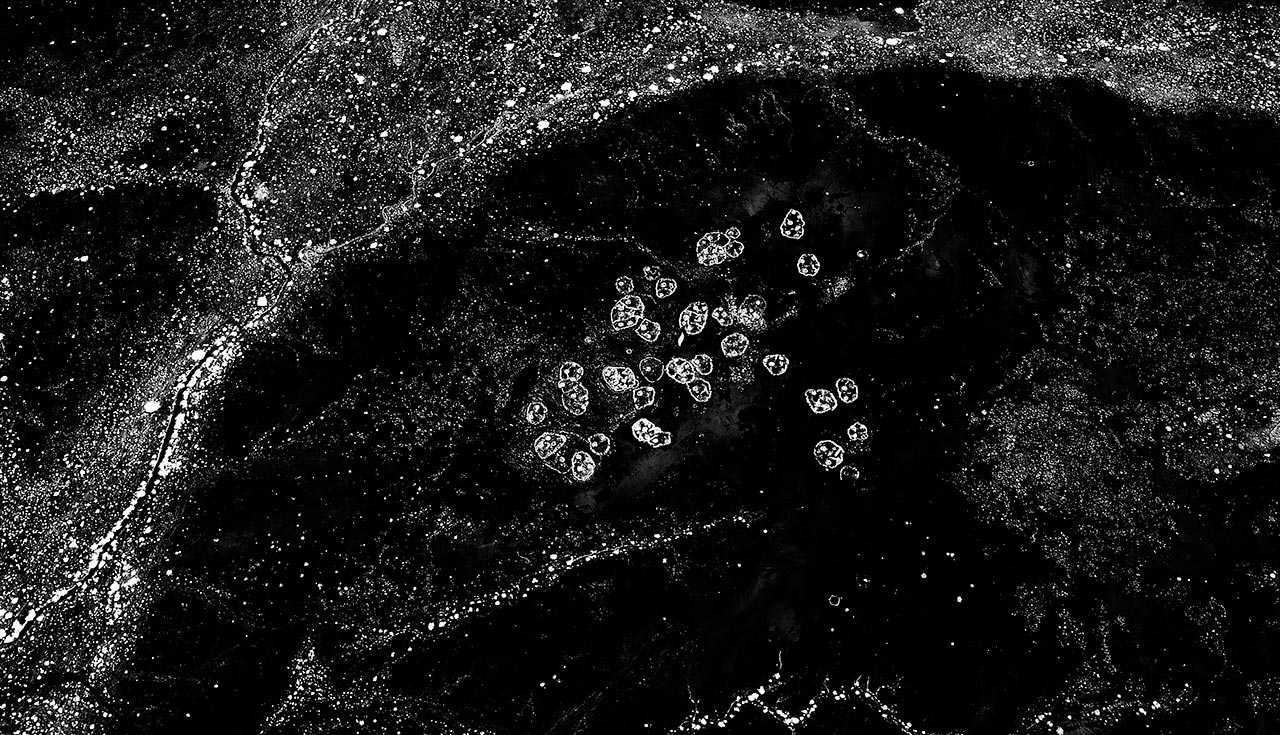

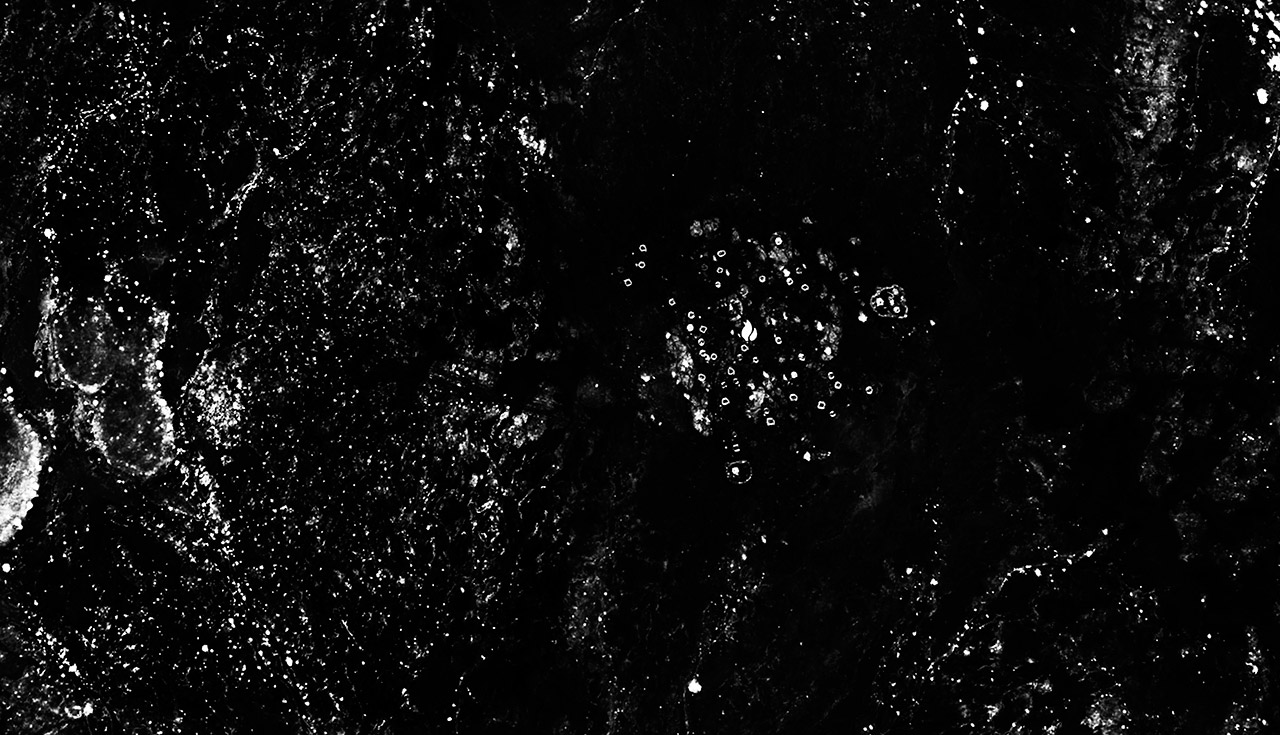

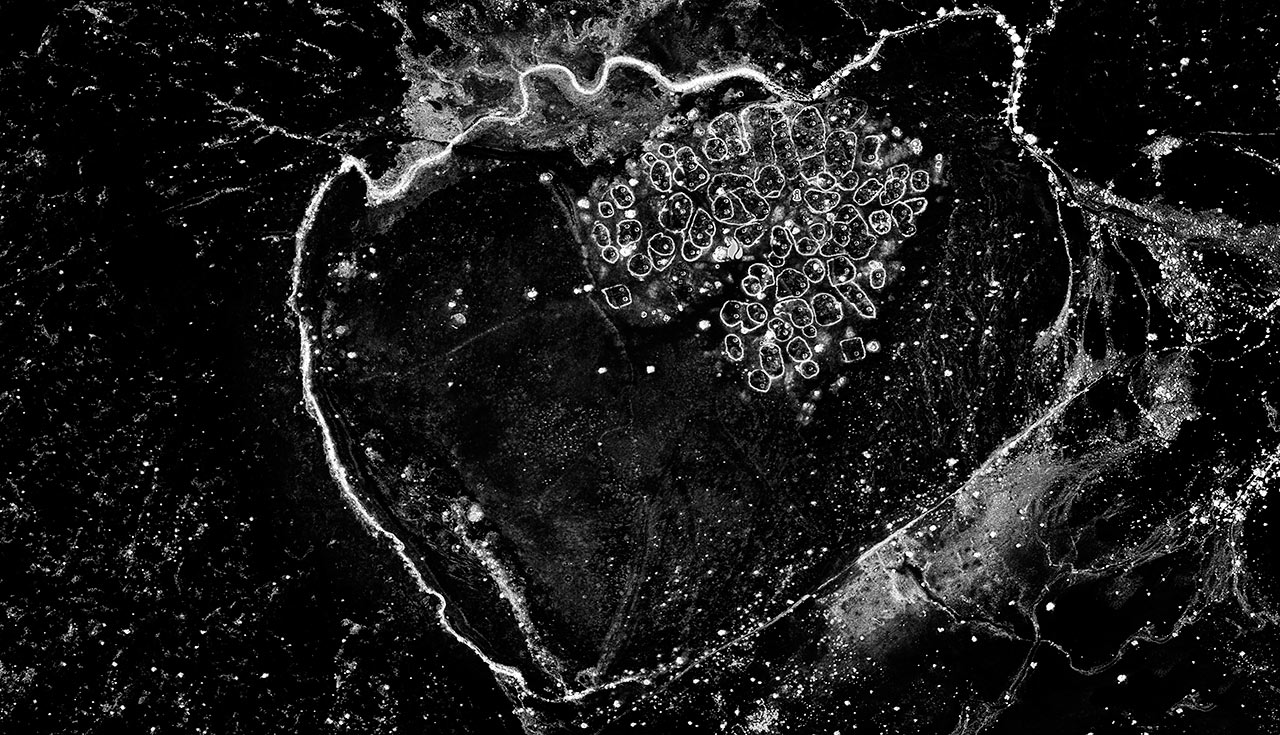

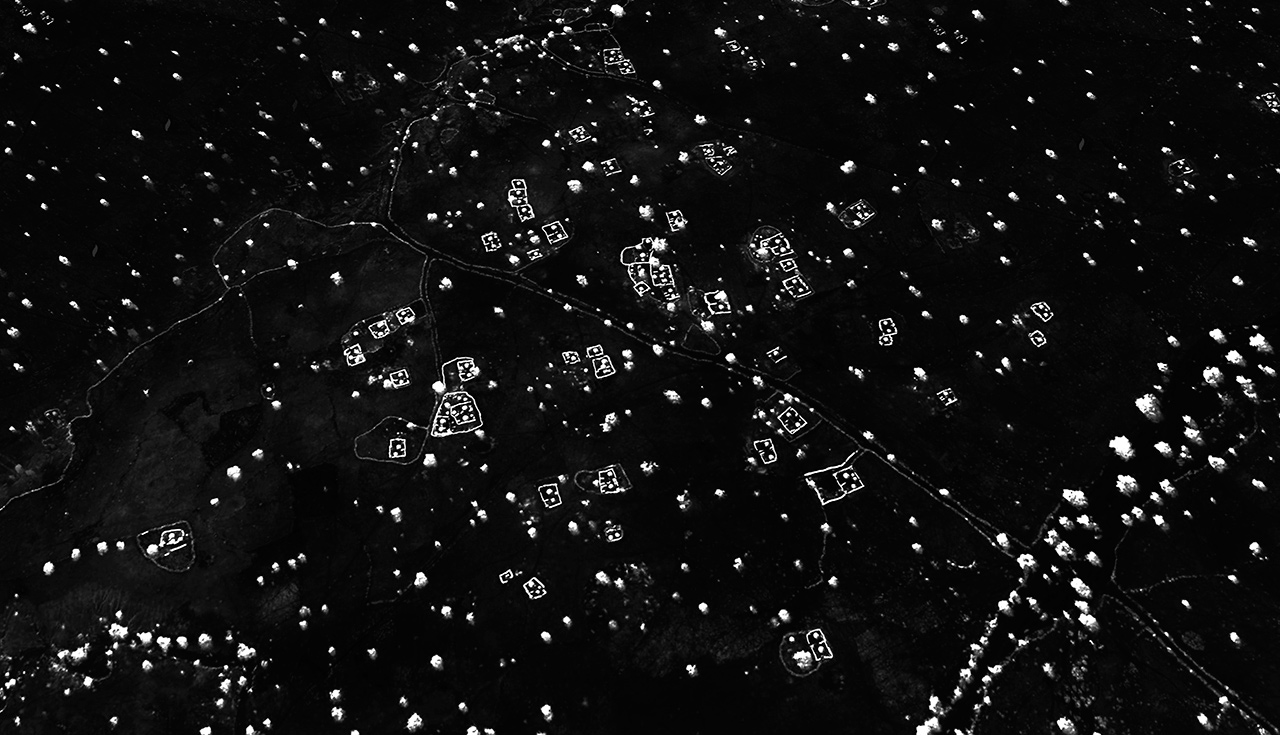

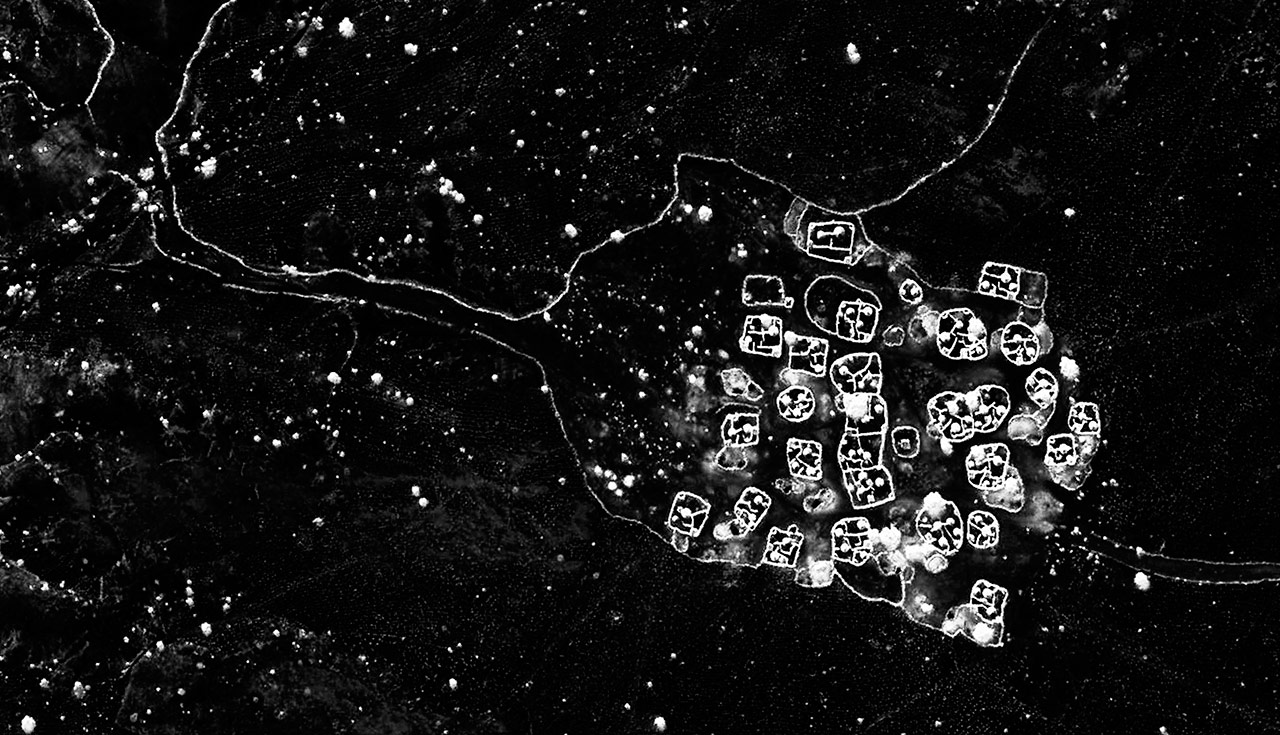

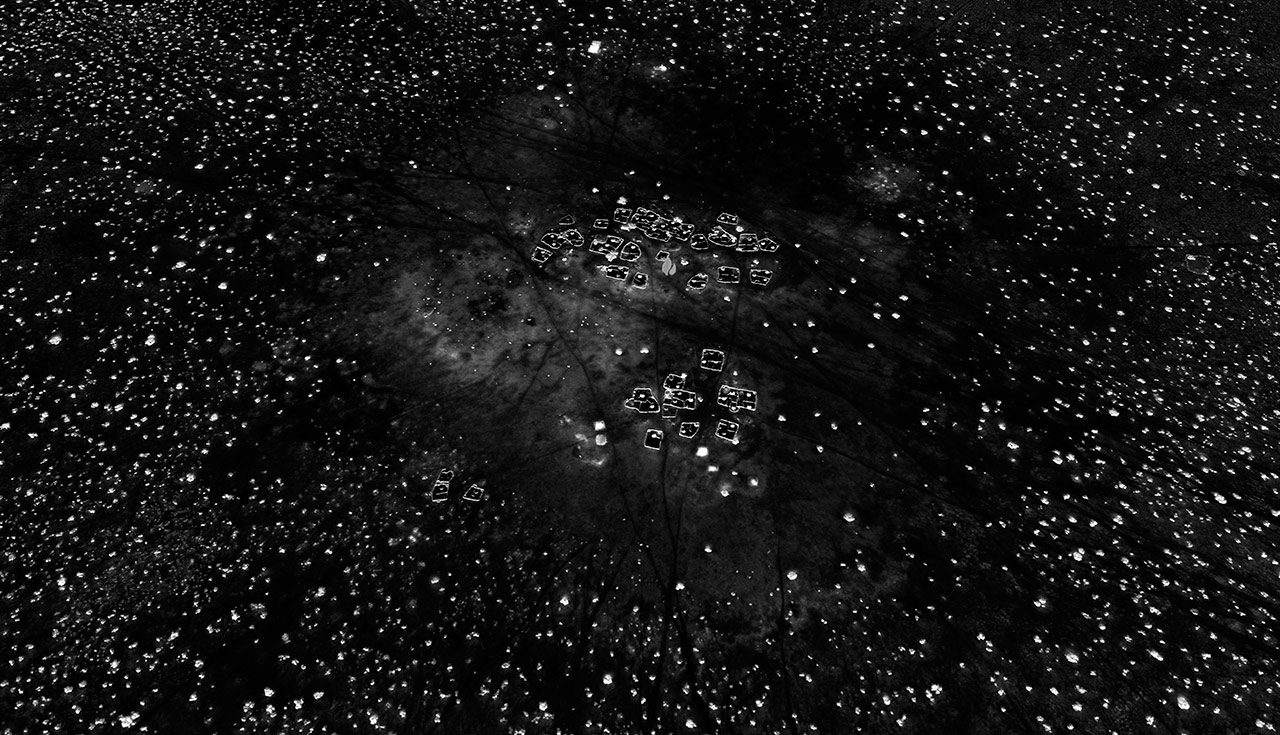

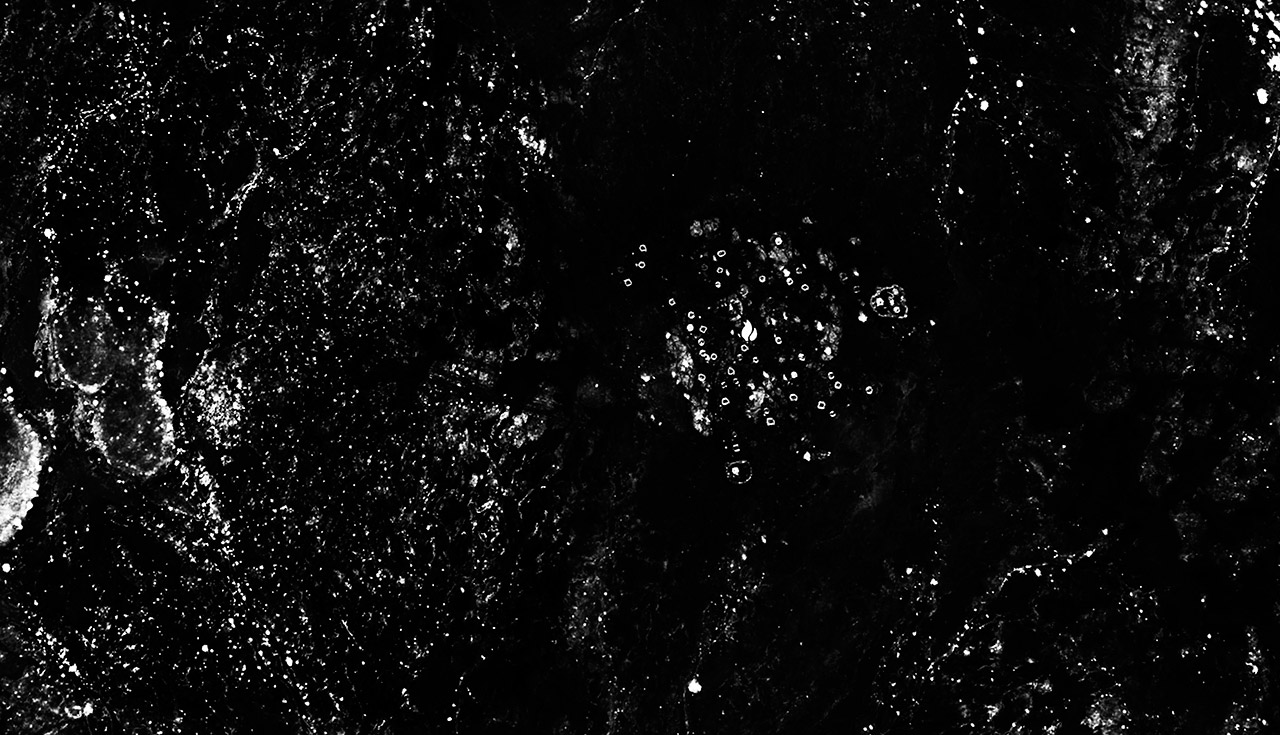

Stars, 2014 explores my desire to find some balance between a relationship with the wild places of my youth, and a pervasive sense of disconnectedness with the natural world.

The Western landscape tradition embodies a pairing that James Elkins calls ‘the subject-object relationship’. Typified by the ‘scenic viewpoint’ or tourist panoramic overlook, we gaze, often through binoculars or telescopes, at wide vistas and dramatic seascapes, awed and overwhelmed. But this landscape experience often alienates the viewer from the scene and, just as the landscape itself becomes an object, a separation arises between them.

Today the majority of people live in urban or semi-urban environments, experiencing the landscape from a distanced position mediated through various media and technology. From this viewpoint the notion of the landscape in all its sensuous materiality, our being within it rather than outside it, seems beyond reach.

Stars, 2014 addresses this distancing by drawing the viewer right into the heart of a forest which still holds mystery, and offers the potential for discovery and exploration. The series considers the fragility of our relationship with the natural world, and the temporal and finite nature of landscape as a human construct.

Mature and ancient forest landscapes are interposed with images of the Milky Way, Omega Centauri, the Norma Galaxy and Embryonic stars in the Nebula NGC 346 captured by the Hubble Telescope. Each image links forest landscapes with the intangible and unknown universe creating a juxtaposition that reflects my personal experiences of the forest; its physicality and tactility set against a profound and fundamental otherness, an alienation that separates us from a truly immersive relationship with the natural world.

(Source Material Credit: STScI/Hubble & NASA)

Ellie Davies (England, 1976). Lives in London and works in the woods and forests of Southern England. She gained her MA in Photography from London College of Communication in 2008. She has recently been selected Landscape Winner in PDN’s The Curator Awards 2016. The six winning artists were exhibited at Foley Gallery in New York from 14 - 24 July 2016. Her Stars series was selected for the Aesthetica Art Prize 2016 and received The People Choice Award and has also been selected for exhibition at the Singapore International Photo Festival in October 2016. The Roe Valley Arts and Cultural Centre in Northern Ireland will host a solo exhibition of her images in April 2017.

Ellie Davies (England, 1976). Lives in London and works in the woods and forests of Southern England. She gained her MA in Photography from London College of Communication in 2008. She has recently been selected Landscape Winner in PDN’s The Curator Awards 2016. The six winning artists were exhibited at Foley Gallery in New York from 14 - 24 July 2016. Her Stars series was selected for the Aesthetica Art Prize 2016 and received The People Choice Award and has also been selected for exhibition at the Singapore International Photo Festival in October 2016. The Roe Valley Arts and Cultural Centre in Northern Ireland will host a solo exhibition of her images in April 2017.

Stars, 2014 explores my desire to find some balance between a relationship with the wild places of my youth, and a pervasive sense of disconnectedness with the natural world.

The Western landscape tradition embodies a pairing that James Elkins calls ‘the subject-object relationship’. Typified by the ‘scenic viewpoint’ or tourist panoramic overlook, we gaze, often through binoculars or telescopes, at wide vistas and dramatic seascapes, awed and overwhelmed. But this landscape experience often alienates the viewer from the scene and, just as the landscape itself becomes an object, a separation arises between them.

Today the majority of people live in urban or semi-urban environments, experiencing the landscape from a distanced position mediated through various media and technology. From this viewpoint the notion of the landscape in all its sensuous materiality, our being within it rather than outside it, seems beyond reach.

Stars, 2014 addresses this distancing by drawing the viewer right into the heart of a forest which still holds mystery, and offers the potential for discovery and exploration. The series considers the fragility of our relationship with the natural world, and the temporal and finite nature of landscape as a human construct.

Mature and ancient forest landscapes are interposed with images of the Milky Way, Omega Centauri, the Norma Galaxy and Embryonic stars in the Nebula NGC 346 captured by the Hubble Telescope. Each image links forest landscapes with the intangible and unknown universe creating a juxtaposition that reflects my personal experiences of the forest; its physicality and tactility set against a profound and fundamental otherness, an alienation that separates us from a truly immersive relationship with the natural world.

(Source Material Credit: STScI/Hubble & NASA)

Ellie Davies (England, 1976). Lives in London and works in the woods and forests of Southern England. She gained her MA in Photography from London College of Communication in 2008. She has recently been selected Landscape Winner in PDN’s The Curator Awards 2016. The six winning artists were exhibited at Foley Gallery in New York from 14 - 24 July 2016. Her Stars series was selected for the Aesthetica Art Prize 2016 and received The People Choice Award and has also been selected for exhibition at the Singapore International Photo Festival in October 2016. The Roe Valley Arts and Cultural Centre in Northern Ireland will host a solo exhibition of her images in April 2017.

Ellie Davies (England, 1976). Lives in London and works in the woods and forests of Southern England. She gained her MA in Photography from London College of Communication in 2008. She has recently been selected Landscape Winner in PDN’s The Curator Awards 2016. The six winning artists were exhibited at Foley Gallery in New York from 14 - 24 July 2016. Her Stars series was selected for the Aesthetica Art Prize 2016 and received The People Choice Award and has also been selected for exhibition at the Singapore International Photo Festival in October 2016. The Roe Valley Arts and Cultural Centre in Northern Ireland will host a solo exhibition of her images in April 2017.Marcus DeSieno

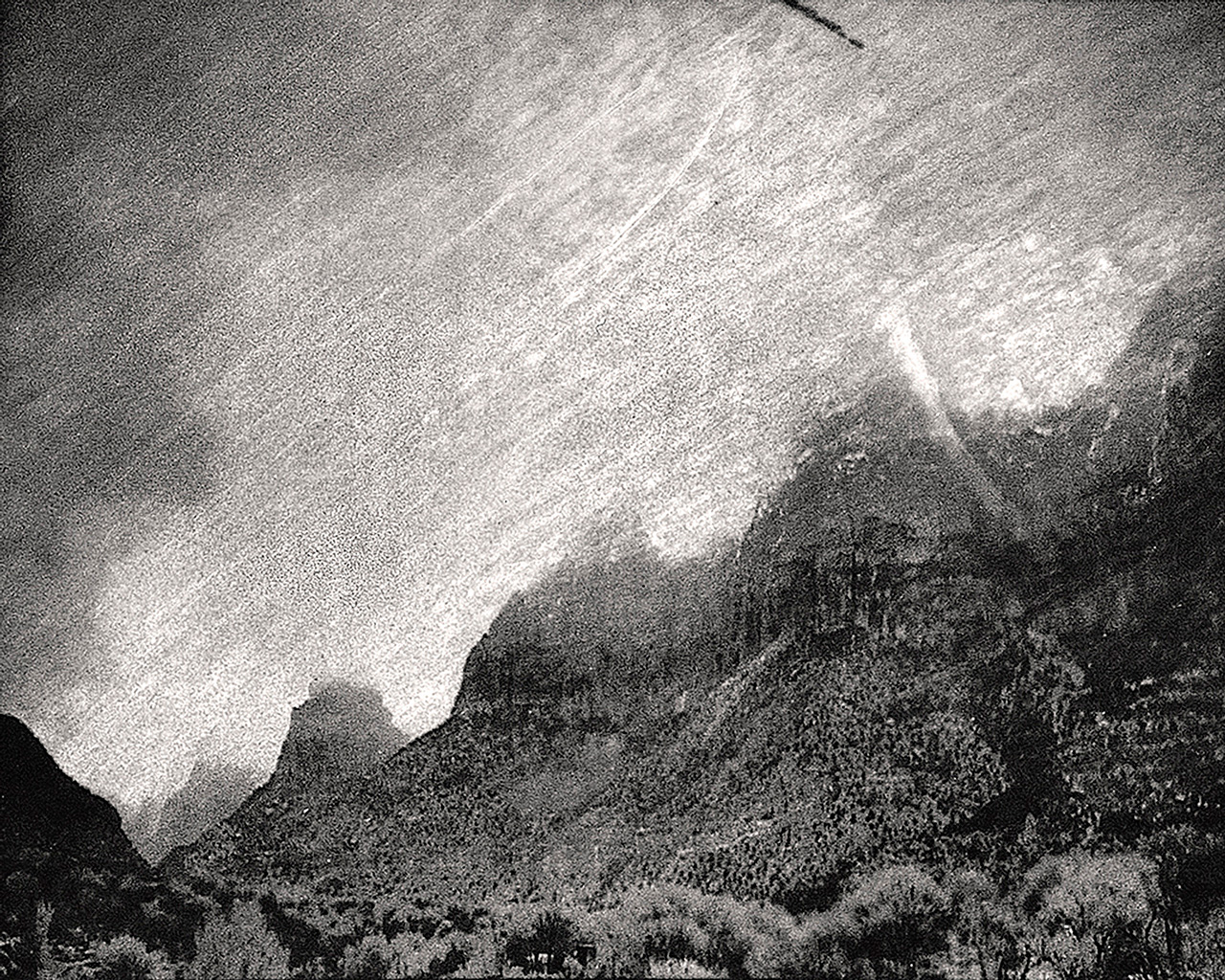

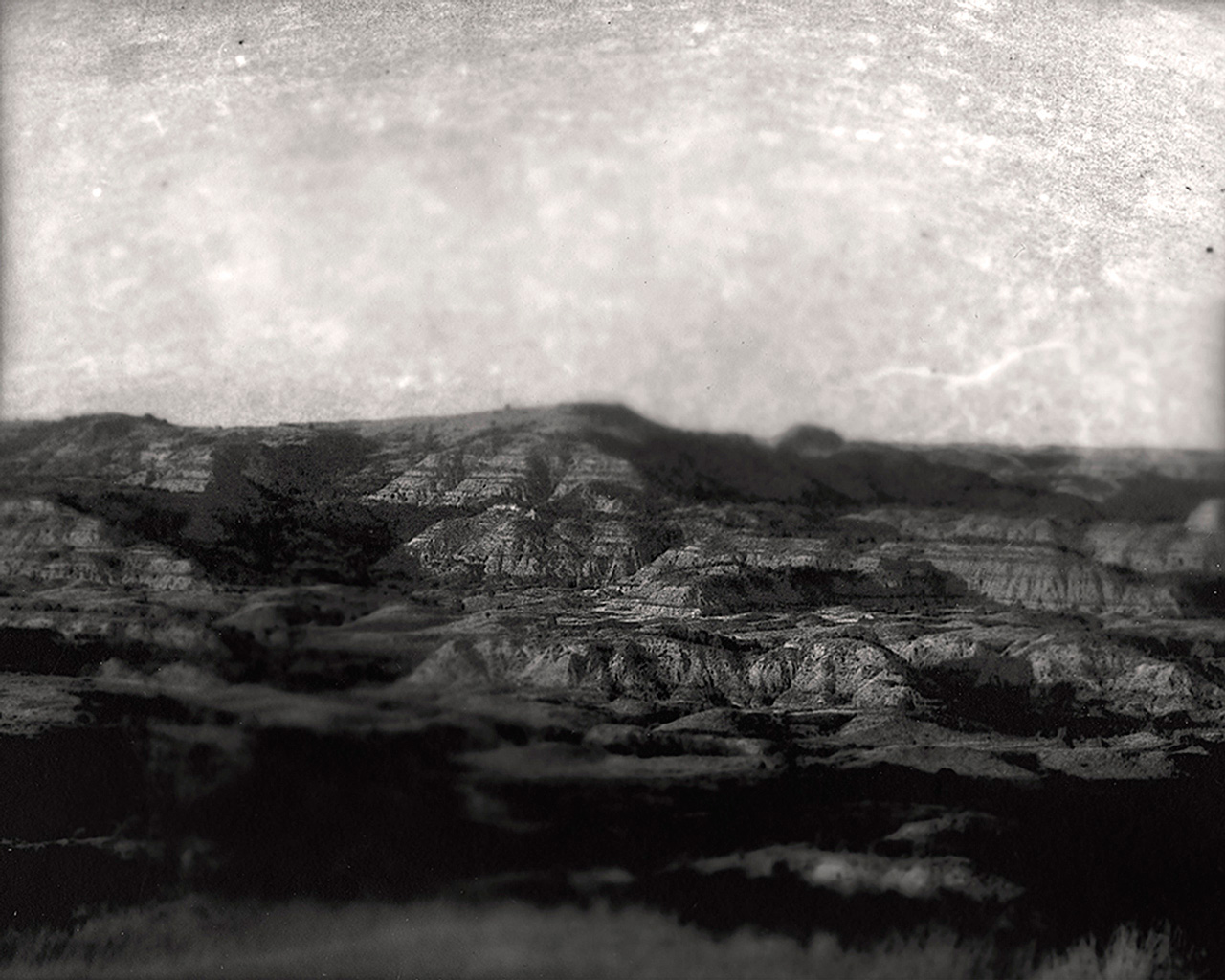

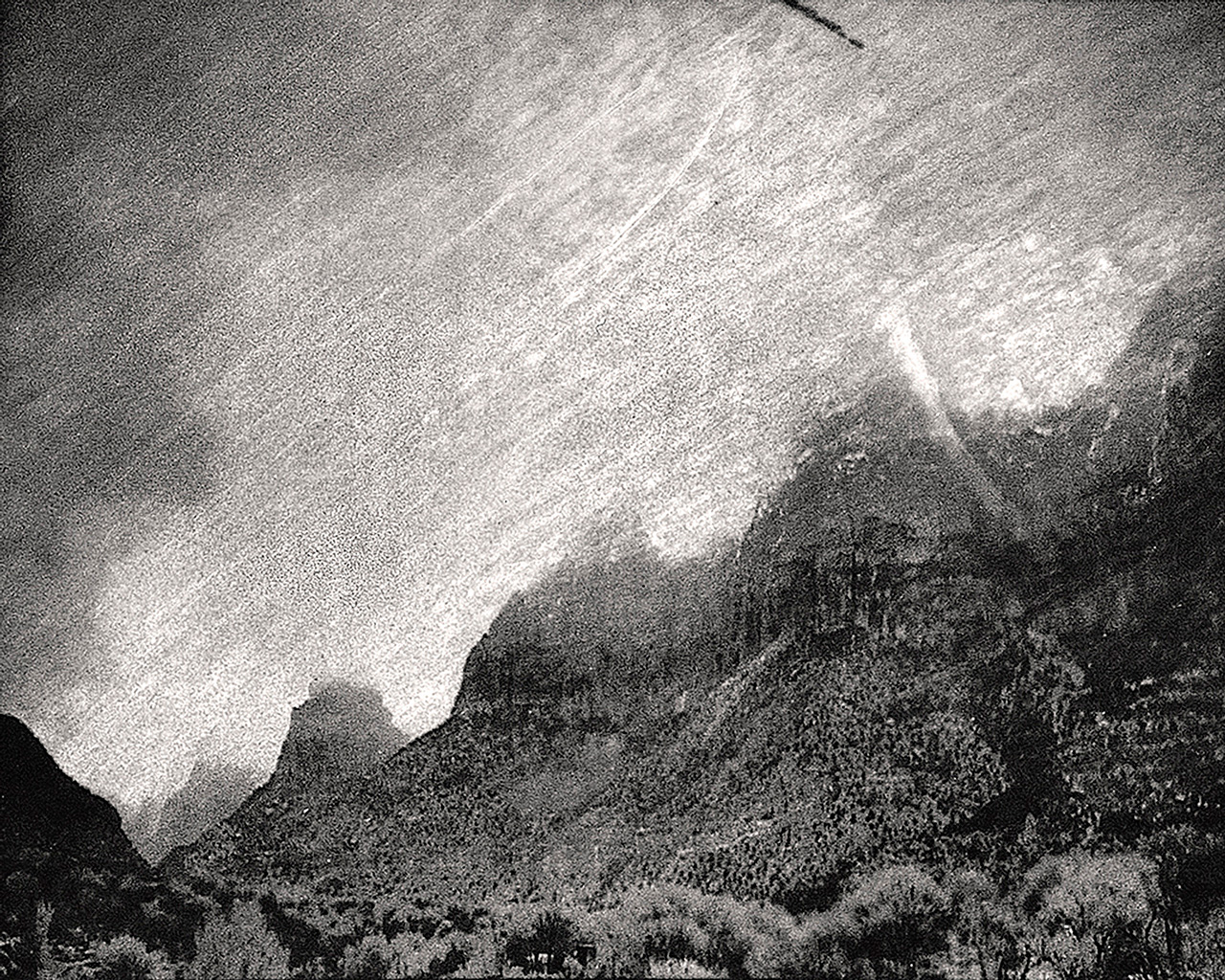

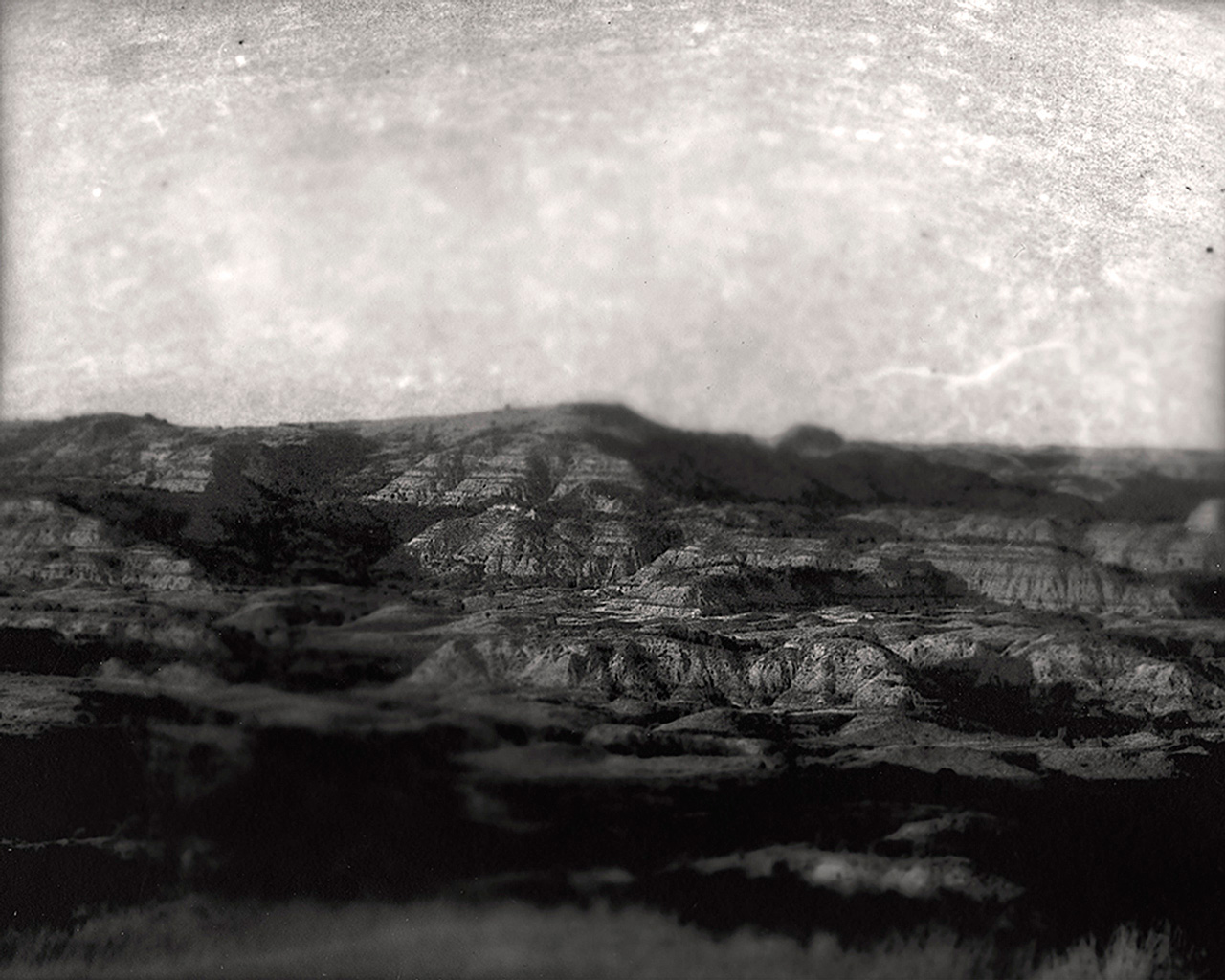

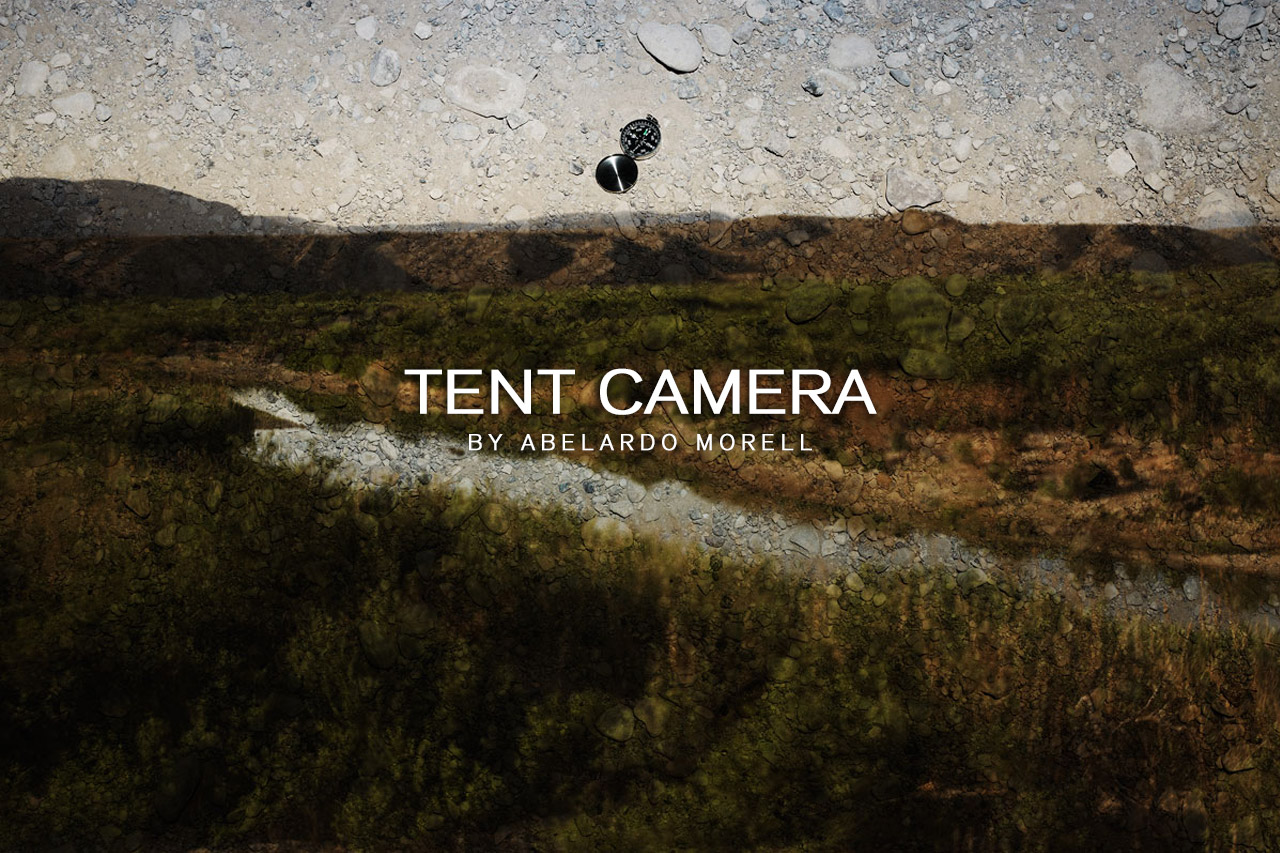

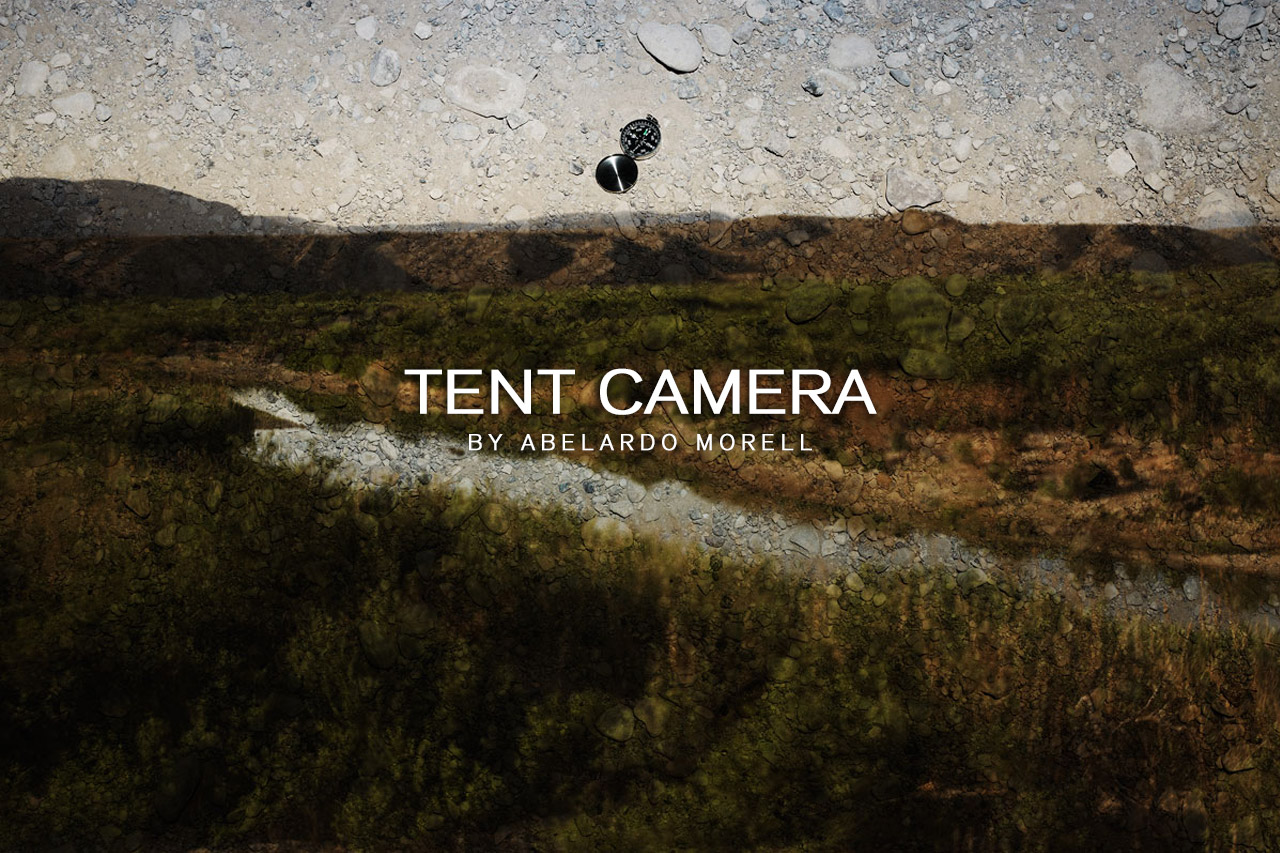

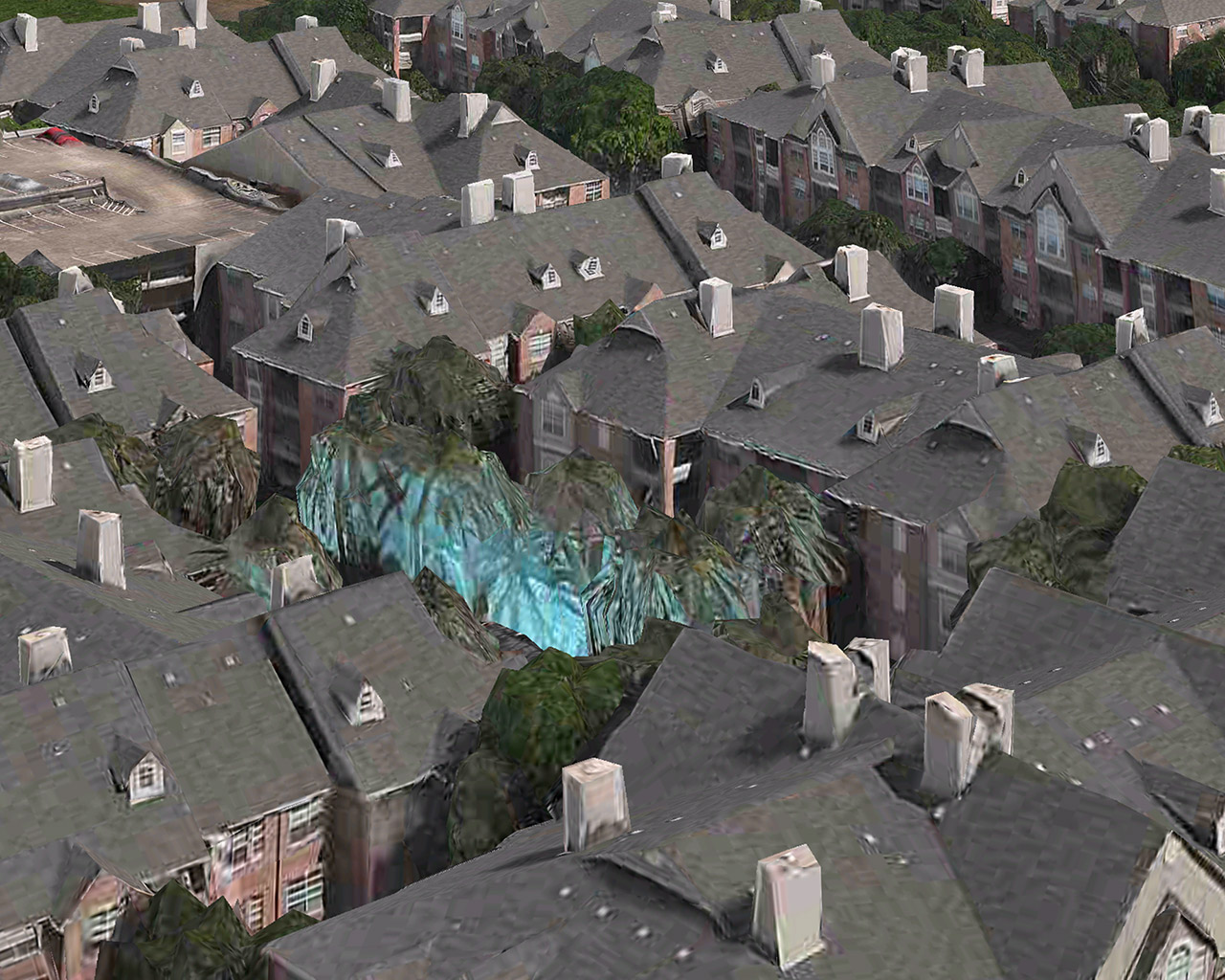

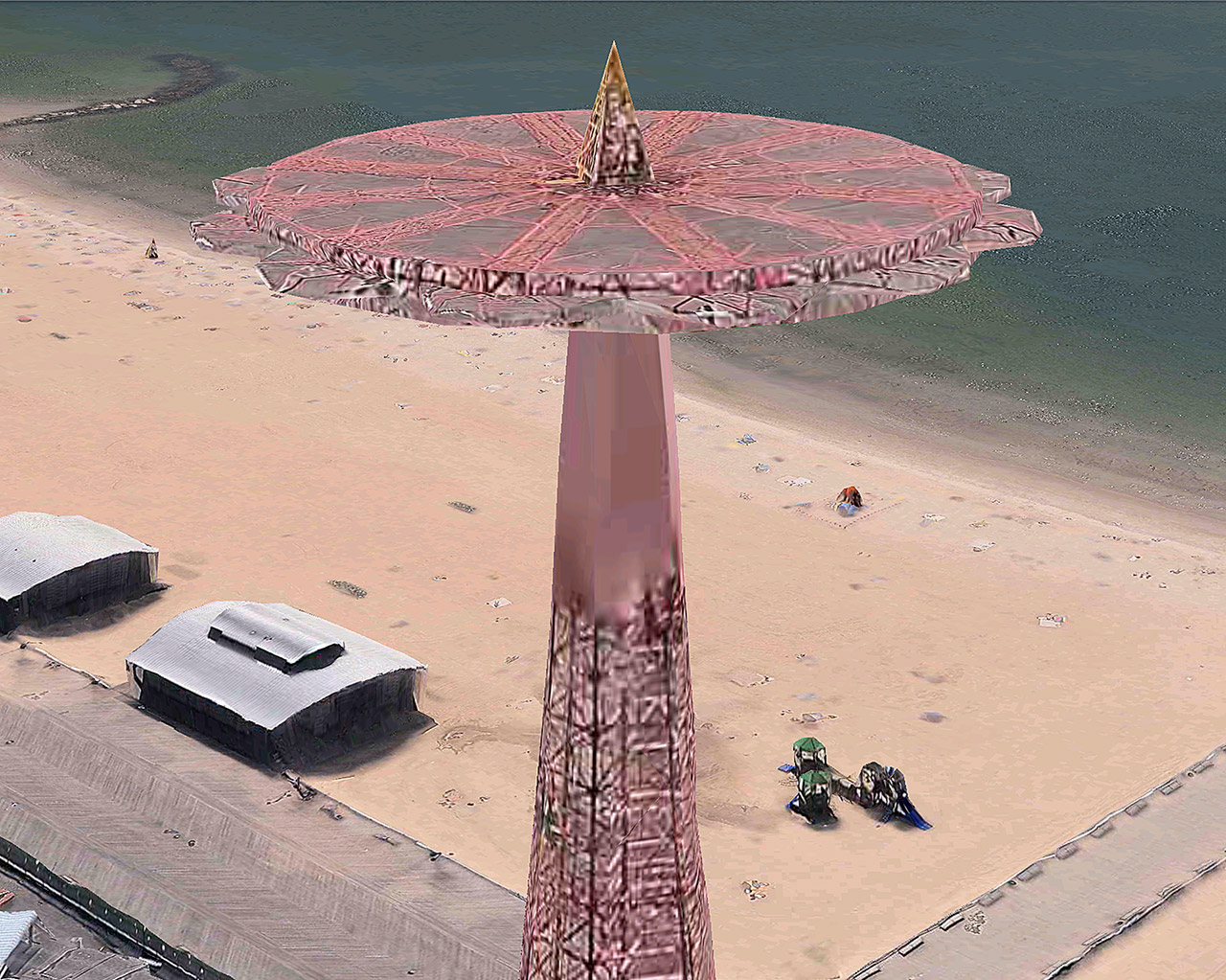

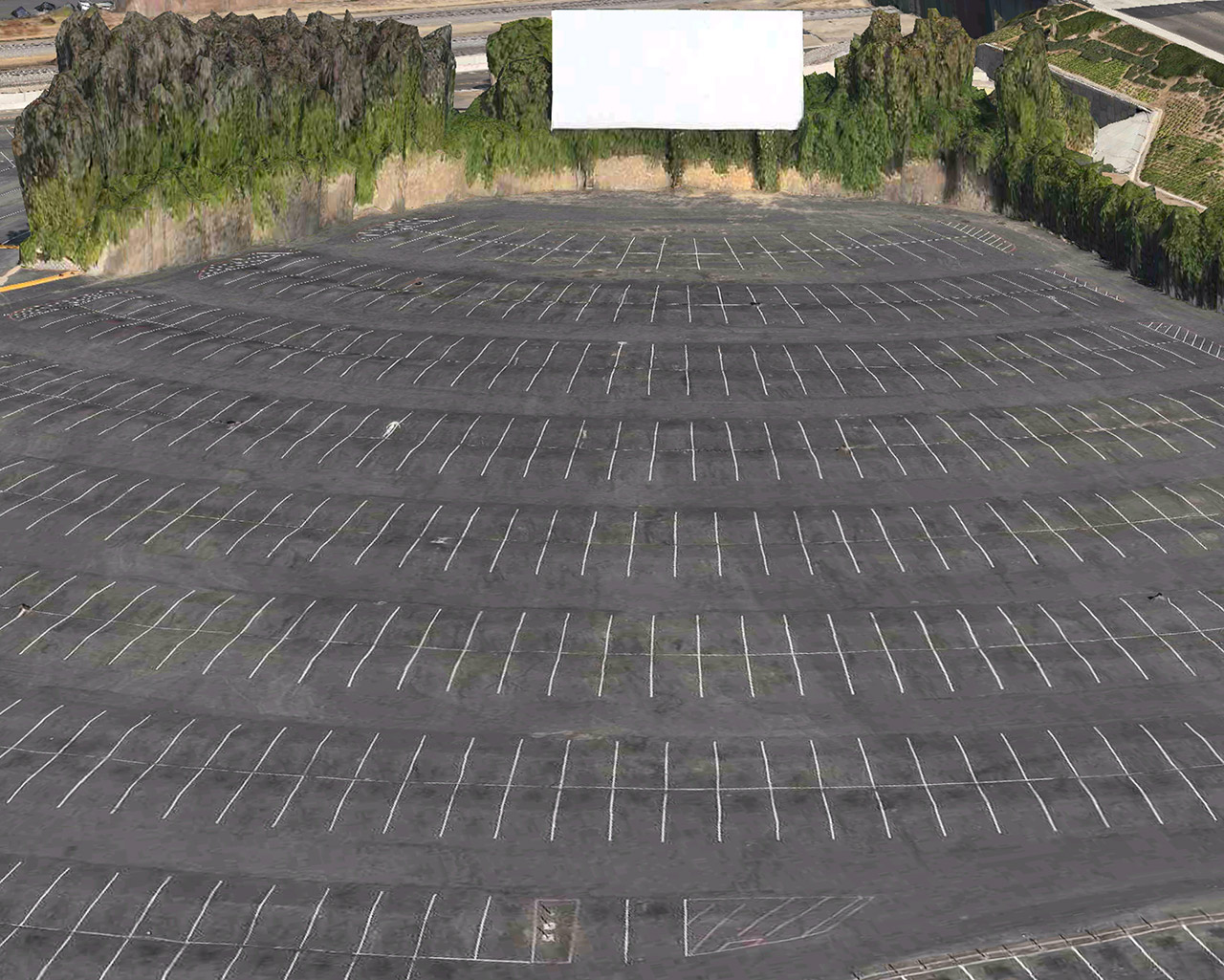

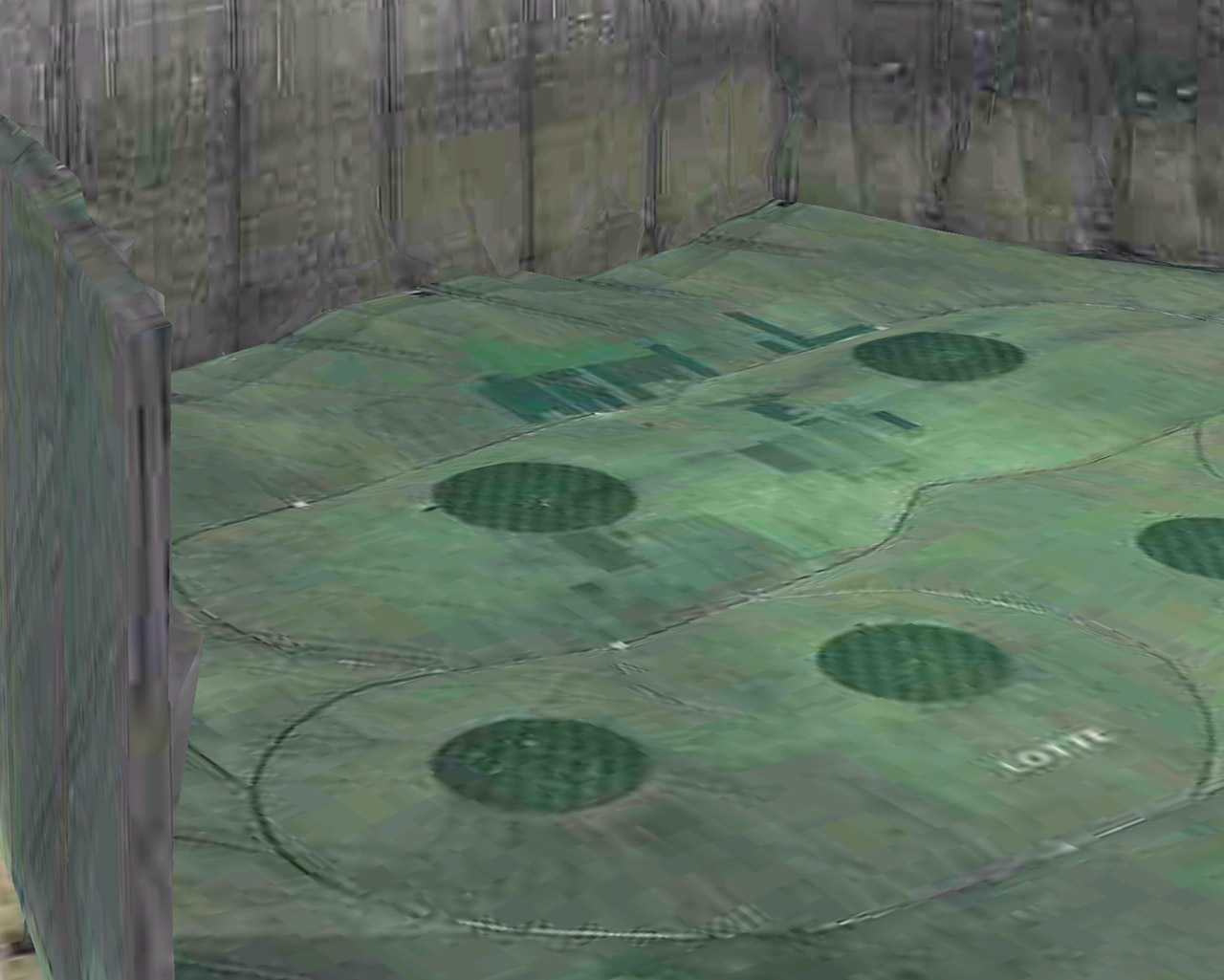

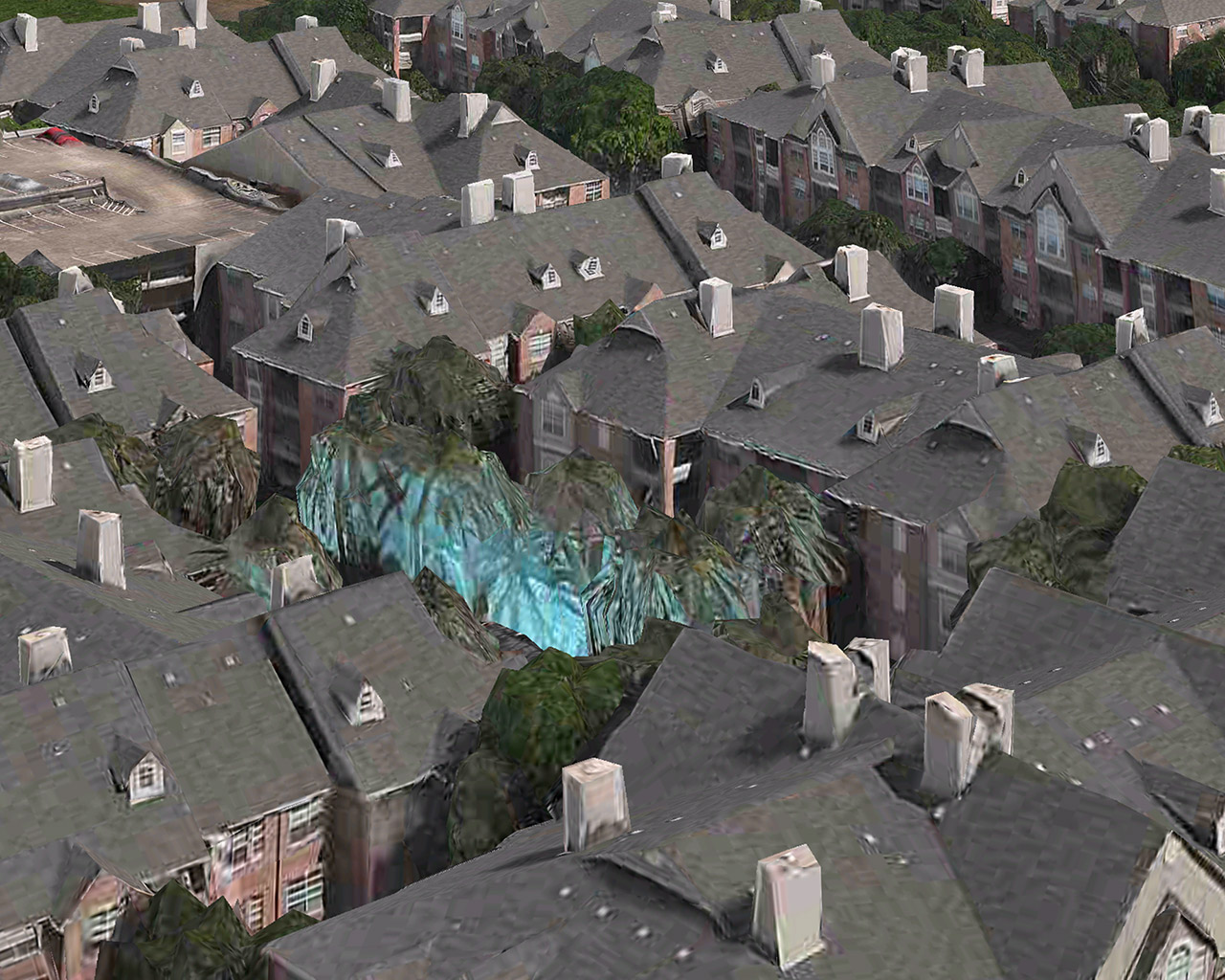

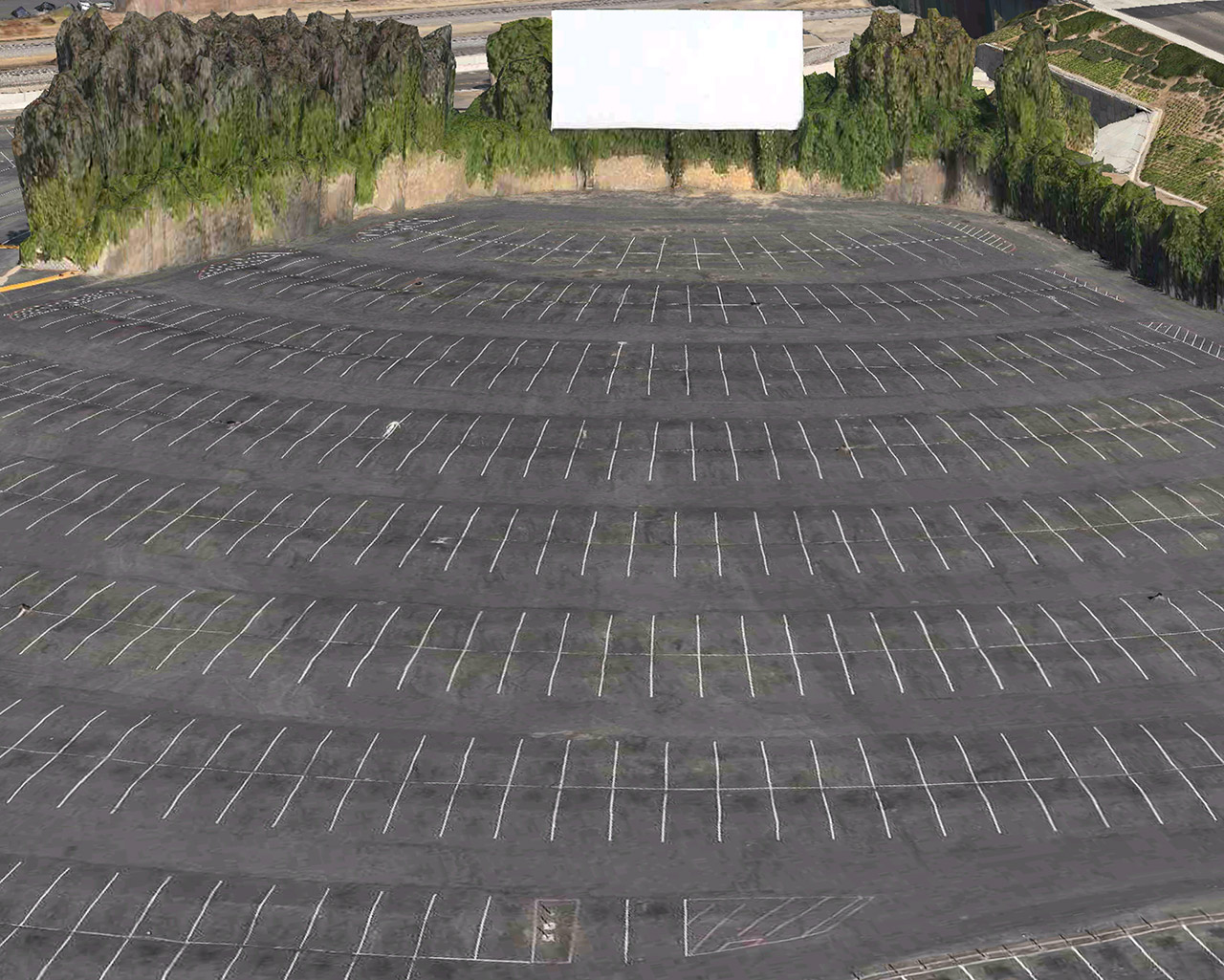

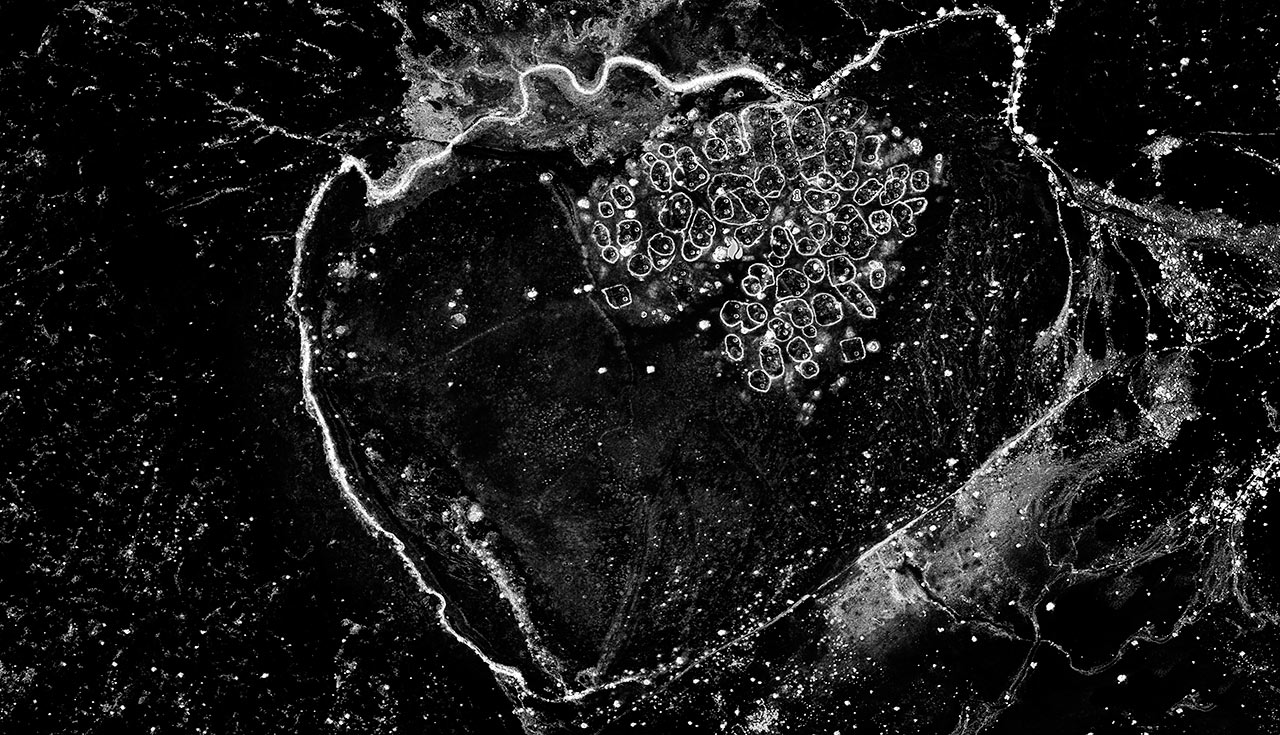

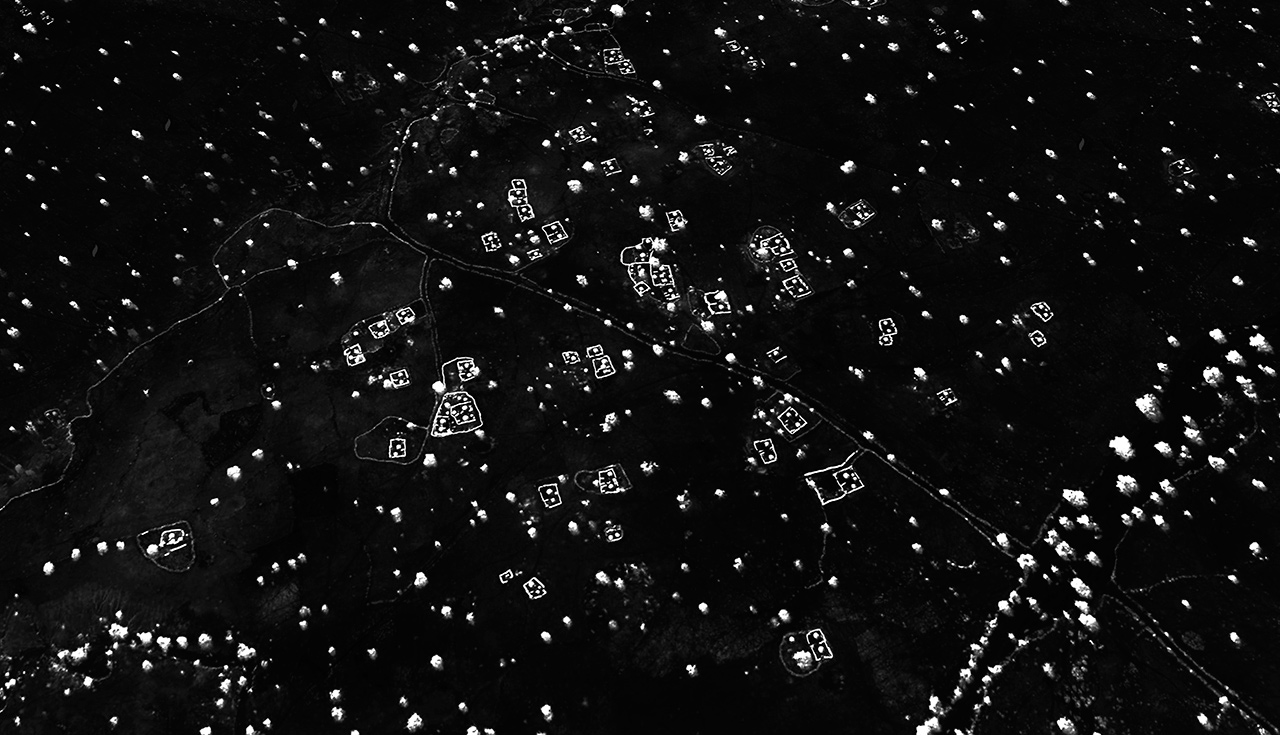

Surveillance Landscapes interrogates how surveillance technology has changed our relationship and understanding of landscape and place in our increasingly intrusive electronic culture. I hack into surveillance cameras, public webcams, and CCTV feeds in a pursuit for the classical picturesque landscape, dislocating the visual product from its automated origins while searching for a conversation between land, borders, and power. The very act of surveying a site through these photographic systems implies a dominating relationship between man and place. Ultimately, I hope to undermine these schemes of social control through the obfuscated melancholic images found while exploiting the technological mechanisms of power in our surveillance society.

Marcus DeSieno (USA). His work is concerned with science and exploration in relation to the history of photography. He received his MFA in Studio Art from the University of South Florida in 2015. DeSieno often assumes the role of the amateur scientist in his work in order to investigate photography's historic relationship with science in regards to the notion of the invisible. Antiquated and obsolescent photographic processes are often combined with contemporary imaging technologies to engage in a critical dialog on the evolution of photographic technology in relation to seeing.

Marcus DeSieno (USA). His work is concerned with science and exploration in relation to the history of photography. He received his MFA in Studio Art from the University of South Florida in 2015. DeSieno often assumes the role of the amateur scientist in his work in order to investigate photography's historic relationship with science in regards to the notion of the invisible. Antiquated and obsolescent photographic processes are often combined with contemporary imaging technologies to engage in a critical dialog on the evolution of photographic technology in relation to seeing.

Surveillance Landscapes interrogates how surveillance technology has changed our relationship and understanding of landscape and place in our increasingly intrusive electronic culture. I hack into surveillance cameras, public webcams, and CCTV feeds in a pursuit for the classical picturesque landscape, dislocating the visual product from its automated origins while searching for a conversation between land, borders, and power. The very act of surveying a site through these photographic systems implies a dominating relationship between man and place. Ultimately, I hope to undermine these schemes of social control through the obfuscated melancholic images found while exploiting the technological mechanisms of power in our surveillance society.

Marcus DeSieno (USA). His work is concerned with science and exploration in relation to the history of photography. He received his MFA in Studio Art from the University of South Florida in 2015. DeSieno often assumes the role of the amateur scientist in his work in order to investigate photography's historic relationship with science in regards to the notion of the invisible. Antiquated and obsolescent photographic processes are often combined with contemporary imaging technologies to engage in a critical dialog on the evolution of photographic technology in relation to seeing.

Marcus DeSieno (USA). His work is concerned with science and exploration in relation to the history of photography. He received his MFA in Studio Art from the University of South Florida in 2015. DeSieno often assumes the role of the amateur scientist in his work in order to investigate photography's historic relationship with science in regards to the notion of the invisible. Antiquated and obsolescent photographic processes are often combined with contemporary imaging technologies to engage in a critical dialog on the evolution of photographic technology in relation to seeing.Rasel Chowdhury

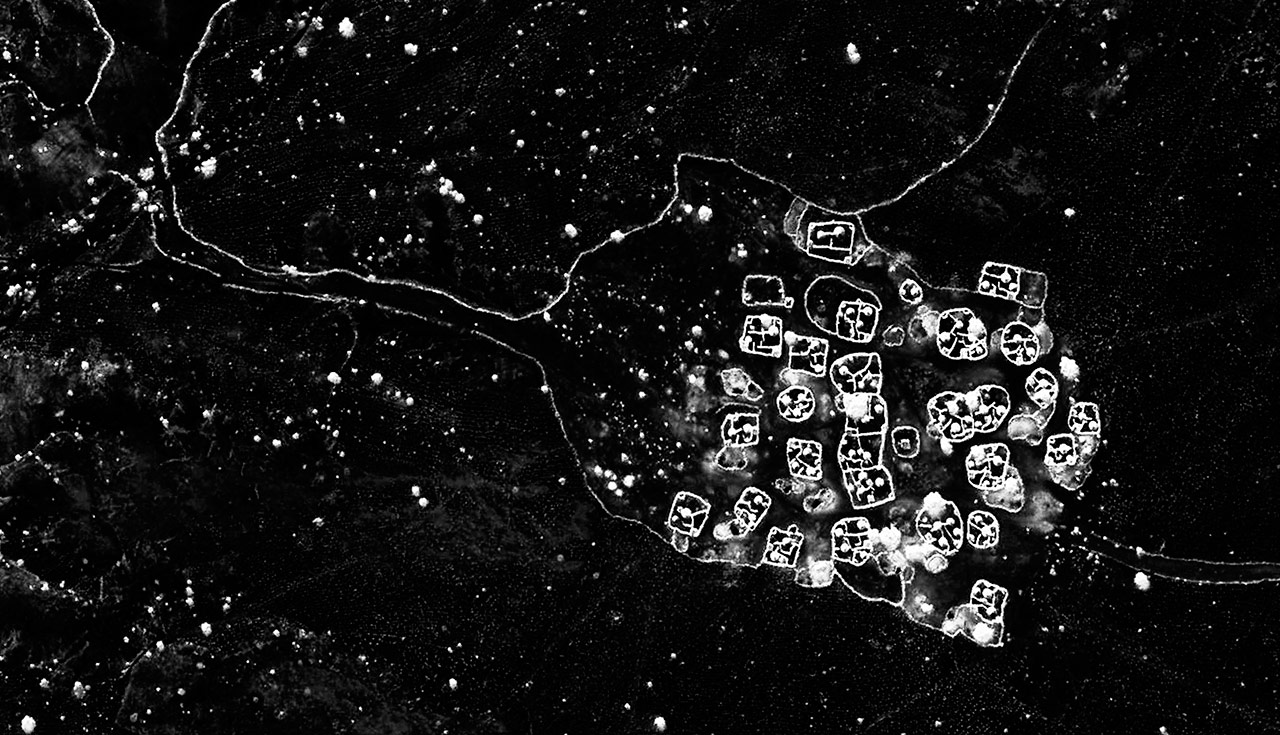

When we are celebrating 400 years of Dhaka City, River Buriganga is fighting to survive. Today, it is nearly dead, can’t run on its natural way. It seems that people of Dhaka are killing the river for their insensitivity.

In Dhaka, people are growing day by day. Working places and various factories are booming constantly. Buriganga River is the one of the most popular way to communicate with another part of the country. Millions of people use the river everyday for bearing their various goods.

Tannery chemical, Mans wastage of whole Dhaka City and Industrial Wastage chemicals directly go down in Buriganga River. Nearly 700 brickfields on the riverside, dockyards and Barn oil from the boats and steamers are the causes of pollution.

This 41 km long river once blessed us with hope and dream to build a new city. But today, the city itself is a cause for the death of Buriganga. We, the Citizens of Dhaka are going to destroy our own river!

As a photographer, I see my role in my engagement with own city. I have an intrinsic relationship with this city and river as I spent most of my life in and around them. As a documentary photographer, my approach was to show the river and its rapidly changing landscape in every possible angle. I explored several corners of the river to have a big picture on people’s destructive involvement. At the same time, divine water of the river, stands alone with its new wave of hope. I just tried to capture all the aspects for a greater concern.

Rasel Chowdhury (Bangladesh, 1988). A documentary photographer. Rasel started photography without a conscious plan, eventually became addicted and decided to document spaces in and around his birthplace, Bangladesh. He obtained his graduation in photography from Pathshala, South Asian Media Institute, and in due course, he found the changing landscapes and environmental issues as few extremely important subjects to document in his generation. Rasel started documenting a dyeing river Buriganga, a dying city Sonargaon, Old People Home, Flood in Bangladesh, Mega City Dhaka and newly transformed spaces around Bangladesh railway to explore the change of the environment, unplanned urban structures and the new form of landscapes.

Rasel Chowdhury (Bangladesh, 1988). A documentary photographer. Rasel started photography without a conscious plan, eventually became addicted and decided to document spaces in and around his birthplace, Bangladesh. He obtained his graduation in photography from Pathshala, South Asian Media Institute, and in due course, he found the changing landscapes and environmental issues as few extremely important subjects to document in his generation. Rasel started documenting a dyeing river Buriganga, a dying city Sonargaon, Old People Home, Flood in Bangladesh, Mega City Dhaka and newly transformed spaces around Bangladesh railway to explore the change of the environment, unplanned urban structures and the new form of landscapes.

When we are celebrating 400 years of Dhaka City, River Buriganga is fighting to survive. Today, it is nearly dead, can’t run on its natural way. It seems that people of Dhaka are killing the river for their insensitivity.

In Dhaka, people are growing day by day. Working places and various factories are booming constantly. Buriganga River is the one of the most popular way to communicate with another part of the country. Millions of people use the river everyday for bearing their various goods.

Tannery chemical, Mans wastage of whole Dhaka City and Industrial Wastage chemicals directly go down in Buriganga River. Nearly 700 brickfields on the riverside, dockyards and Barn oil from the boats and steamers are the causes of pollution.

This 41 km long river once blessed us with hope and dream to build a new city. But today, the city itself is a cause for the death of Buriganga. We, the Citizens of Dhaka are going to destroy our own river!

As a photographer, I see my role in my engagement with own city. I have an intrinsic relationship with this city and river as I spent most of my life in and around them. As a documentary photographer, my approach was to show the river and its rapidly changing landscape in every possible angle. I explored several corners of the river to have a big picture on people’s destructive involvement. At the same time, divine water of the river, stands alone with its new wave of hope. I just tried to capture all the aspects for a greater concern.

Rasel Chowdhury (Bangladesh, 1988). A documentary photographer. Rasel started photography without a conscious plan, eventually became addicted and decided to document spaces in and around his birthplace, Bangladesh. He obtained his graduation in photography from Pathshala, South Asian Media Institute, and in due course, he found the changing landscapes and environmental issues as few extremely important subjects to document in his generation. Rasel started documenting a dyeing river Buriganga, a dying city Sonargaon, Old People Home, Flood in Bangladesh, Mega City Dhaka and newly transformed spaces around Bangladesh railway to explore the change of the environment, unplanned urban structures and the new form of landscapes.

Rasel Chowdhury (Bangladesh, 1988). A documentary photographer. Rasel started photography without a conscious plan, eventually became addicted and decided to document spaces in and around his birthplace, Bangladesh. He obtained his graduation in photography from Pathshala, South Asian Media Institute, and in due course, he found the changing landscapes and environmental issues as few extremely important subjects to document in his generation. Rasel started documenting a dyeing river Buriganga, a dying city Sonargaon, Old People Home, Flood in Bangladesh, Mega City Dhaka and newly transformed spaces around Bangladesh railway to explore the change of the environment, unplanned urban structures and the new form of landscapes.Júlia Pontés

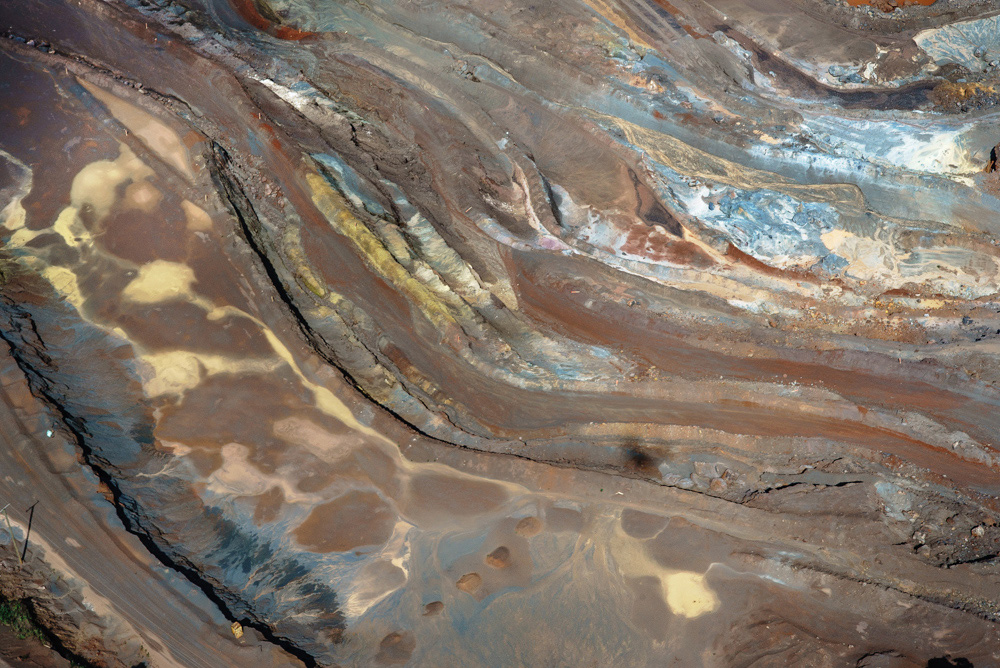

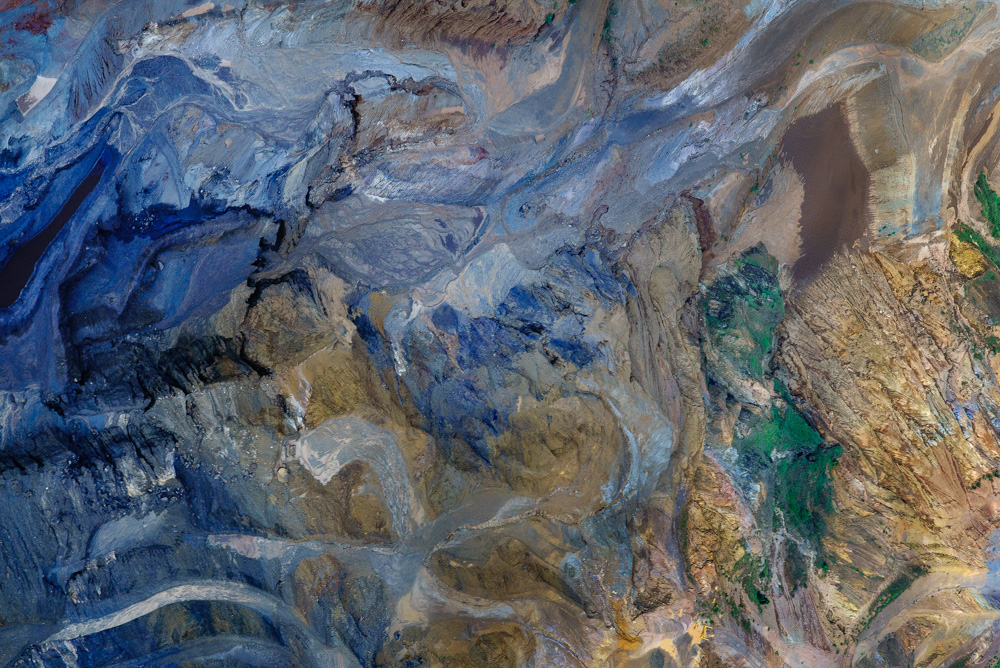

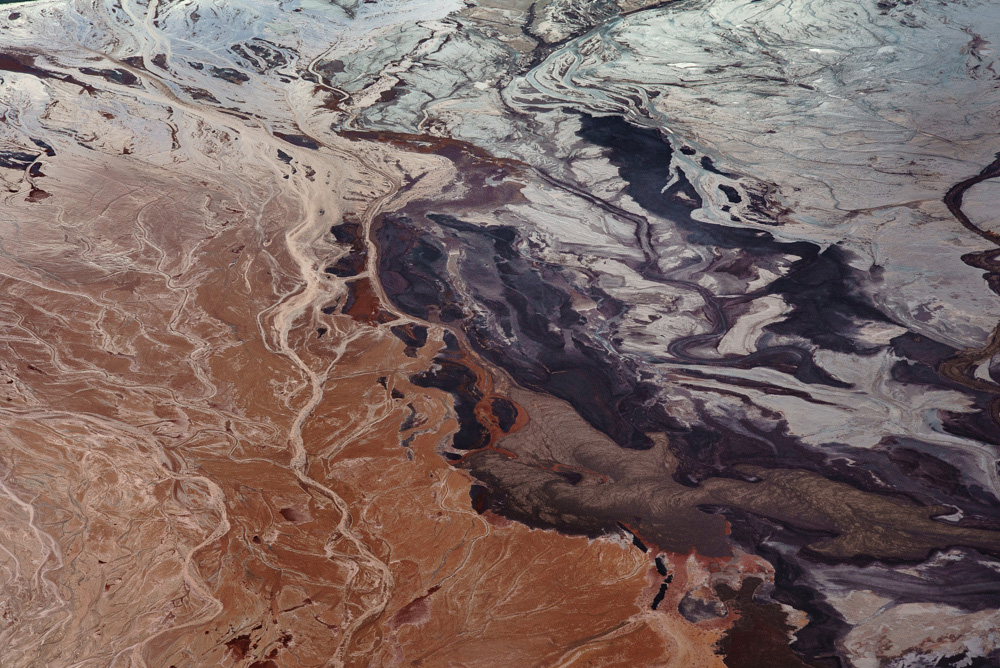

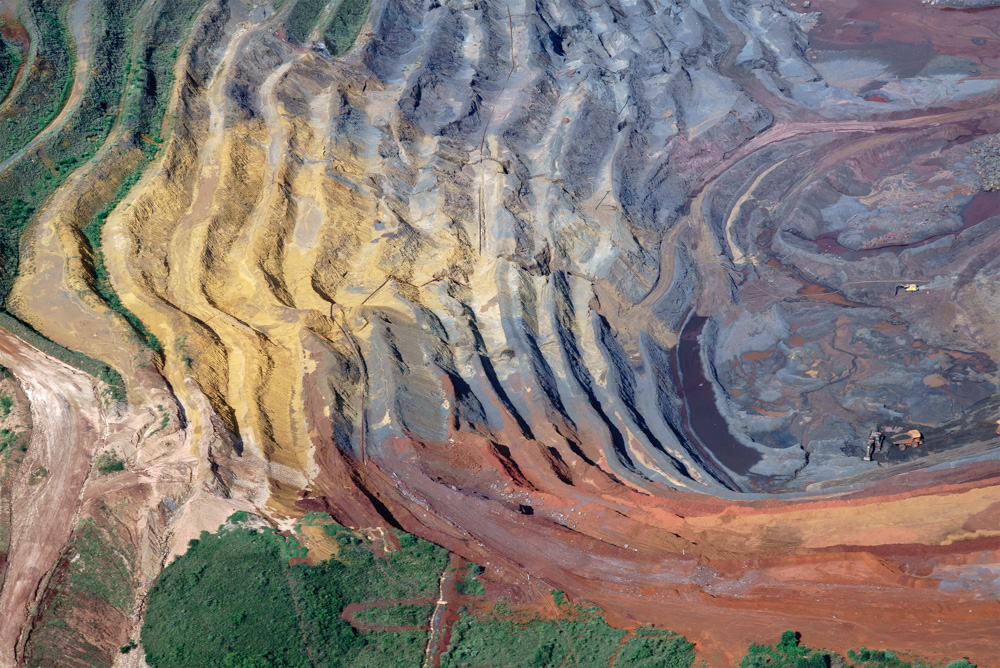

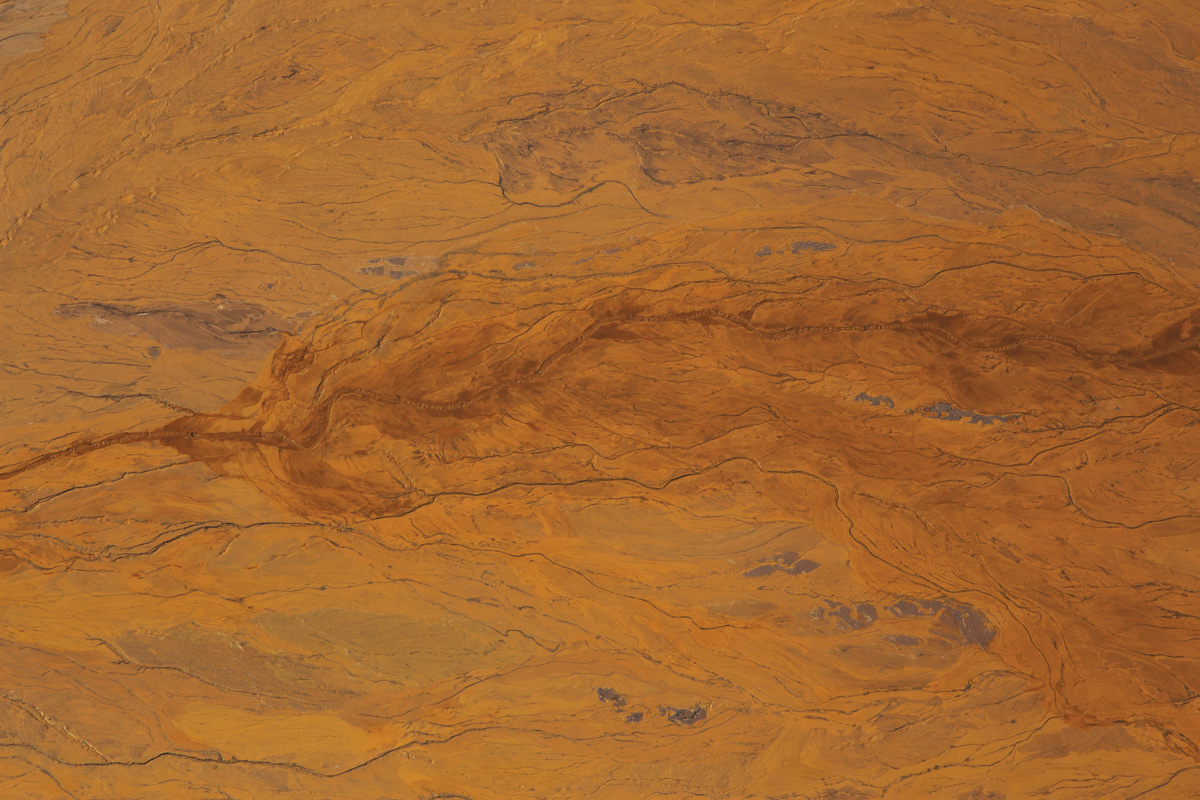

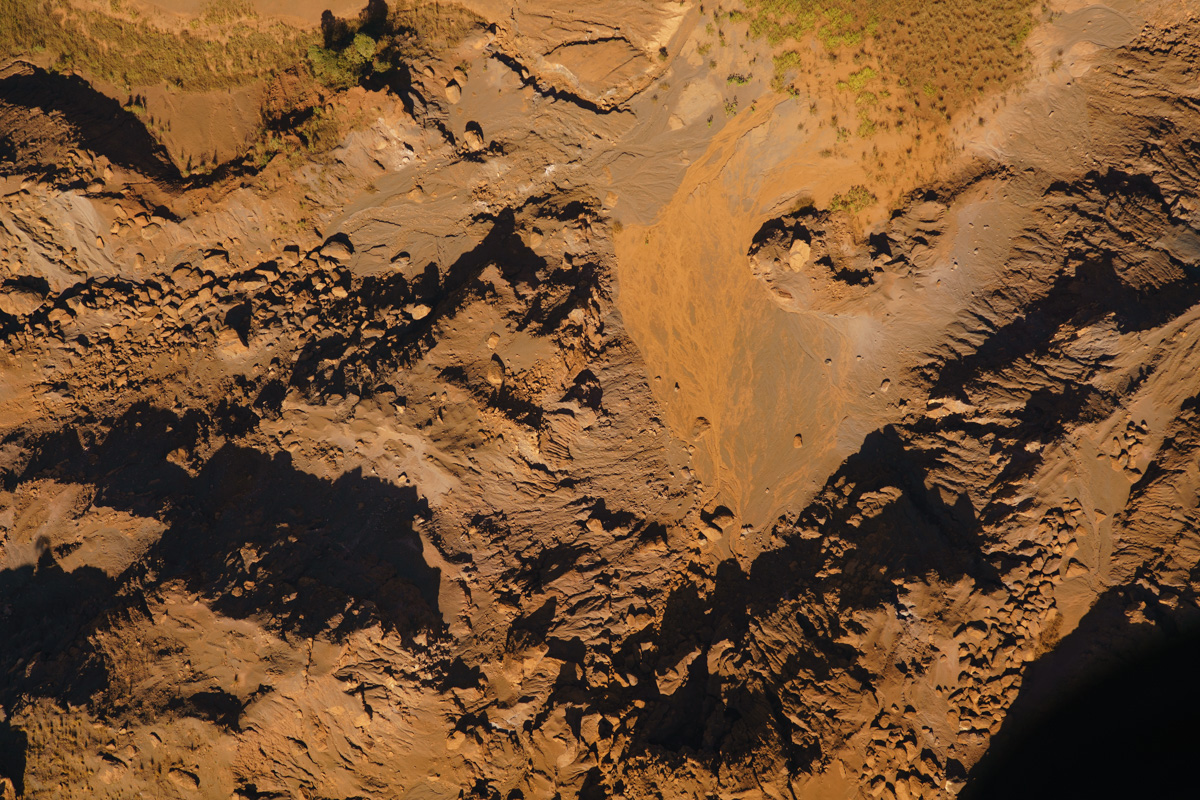

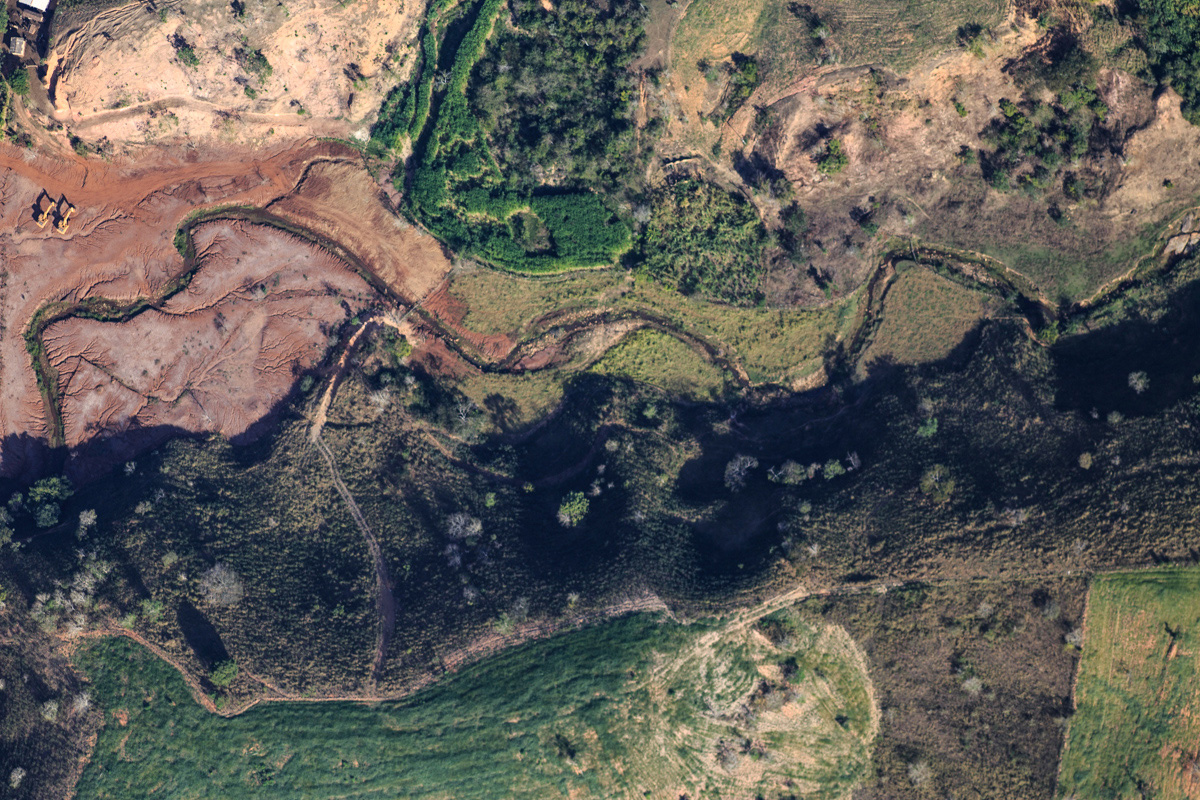

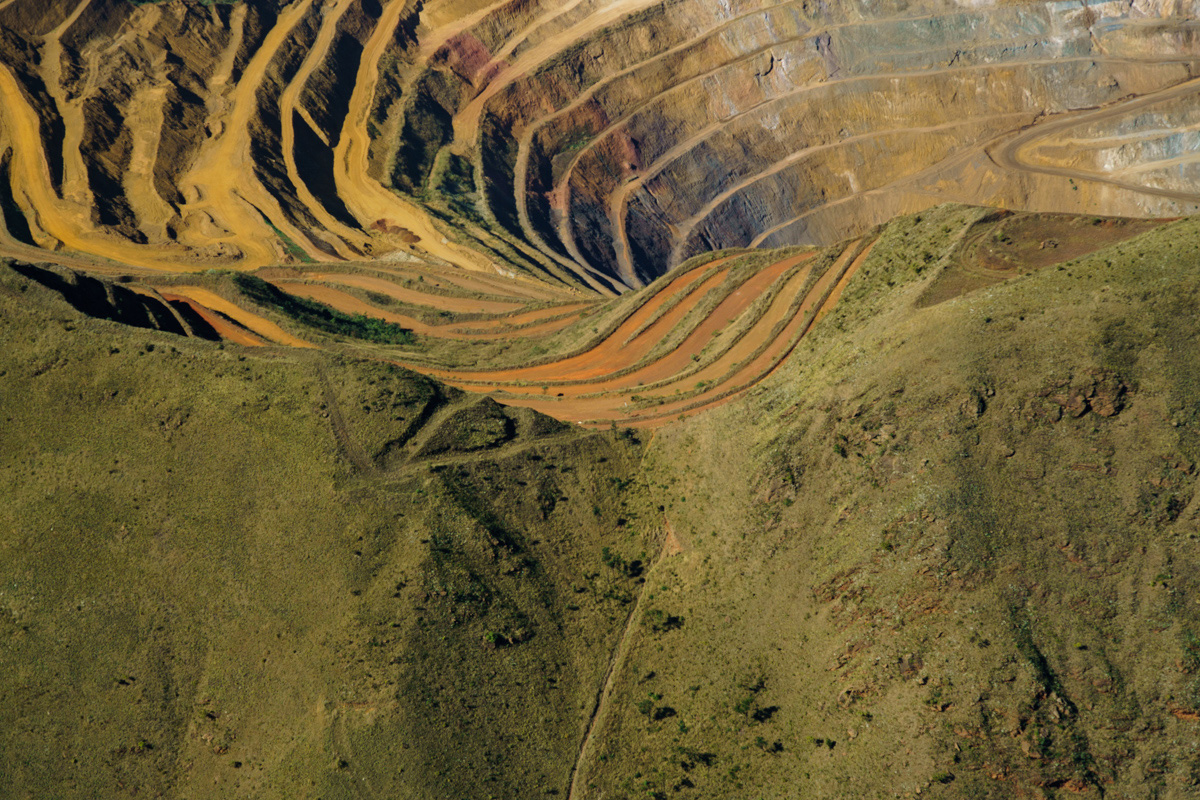

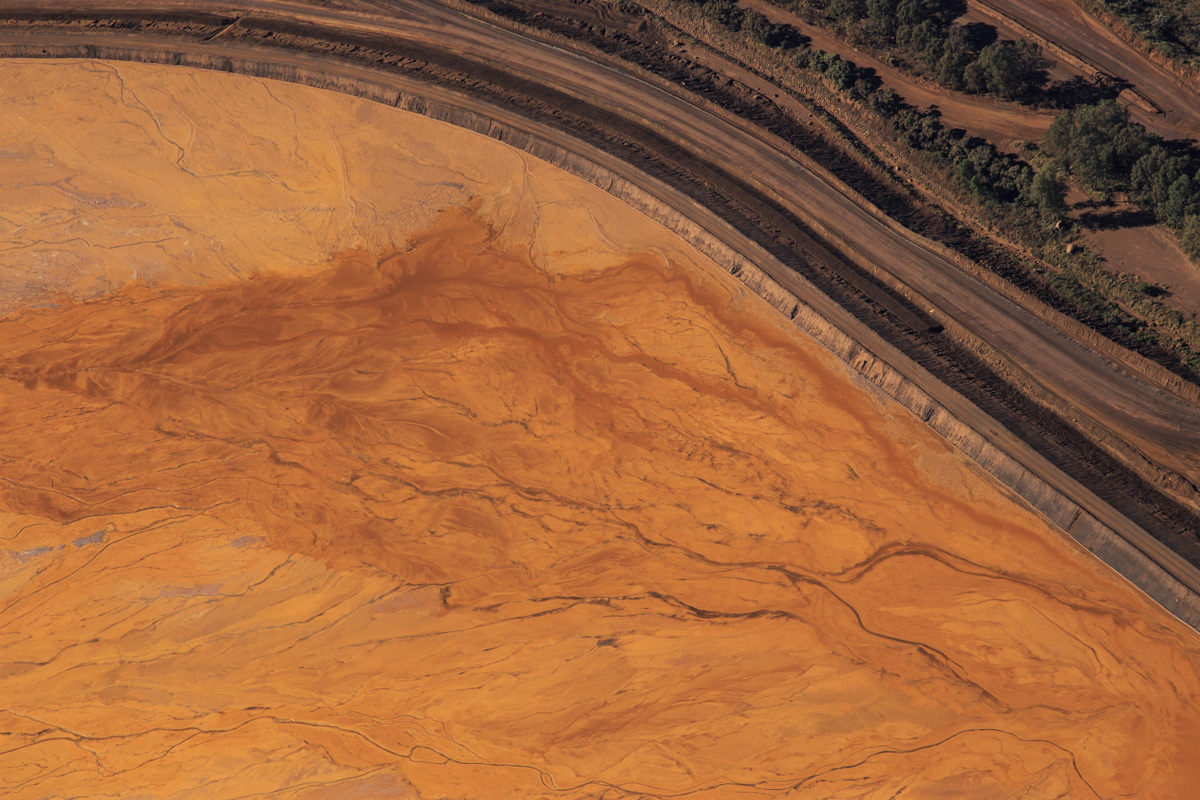

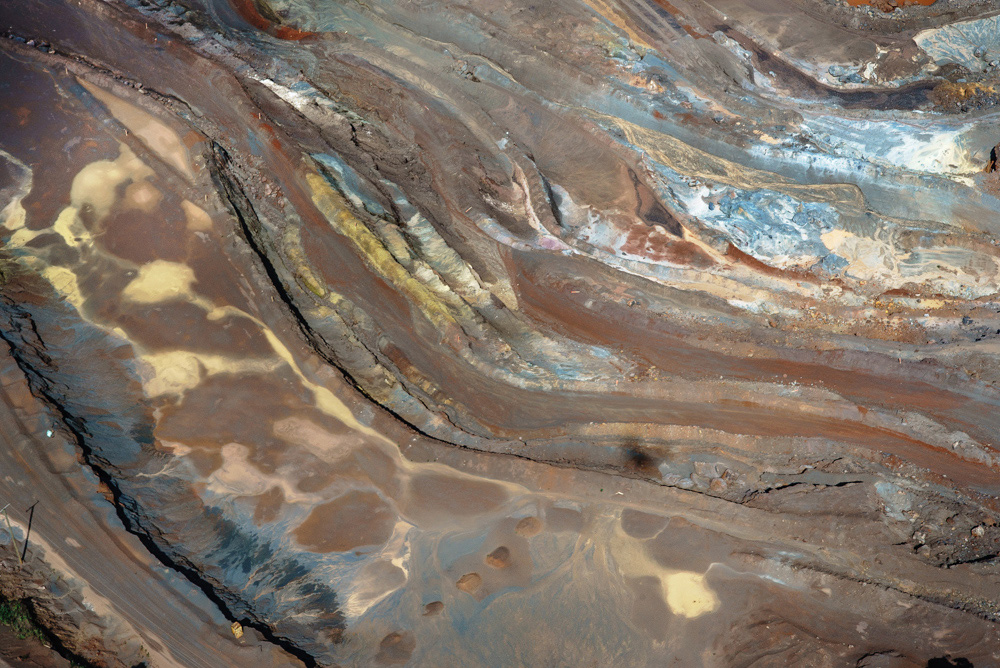

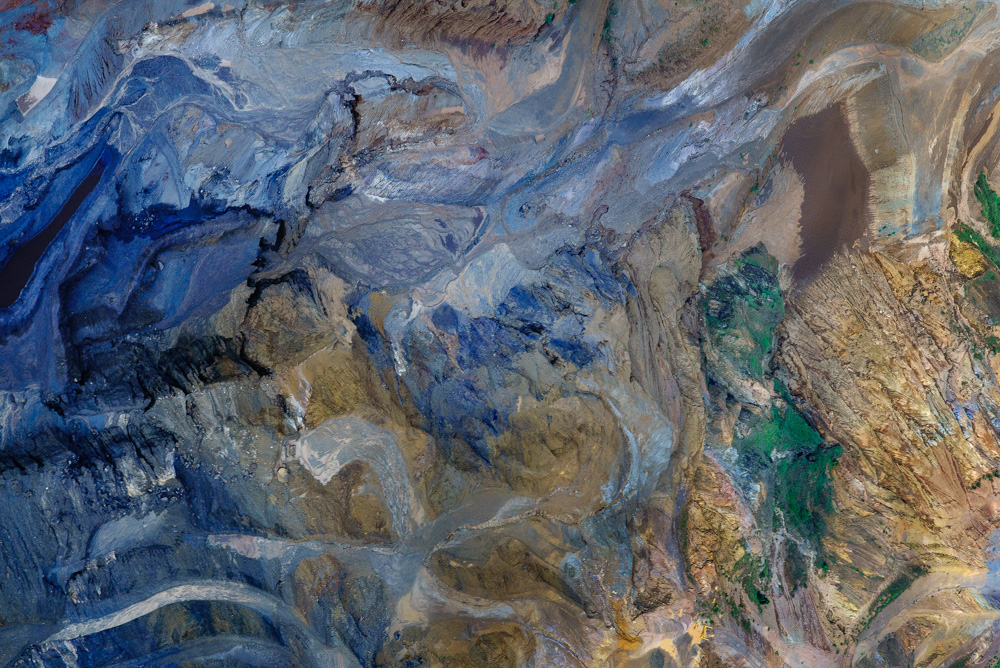

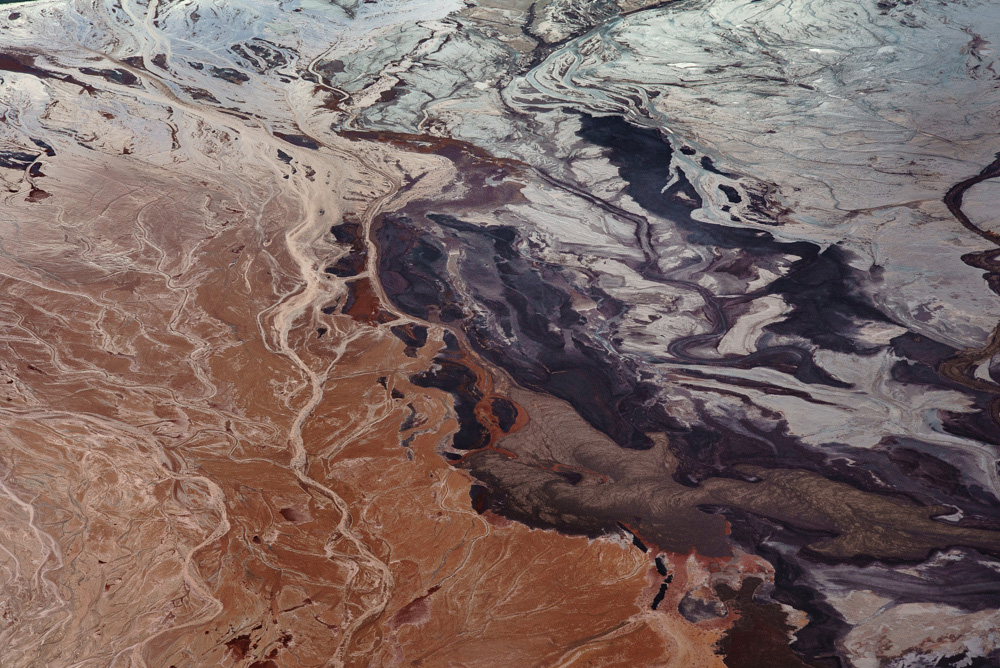

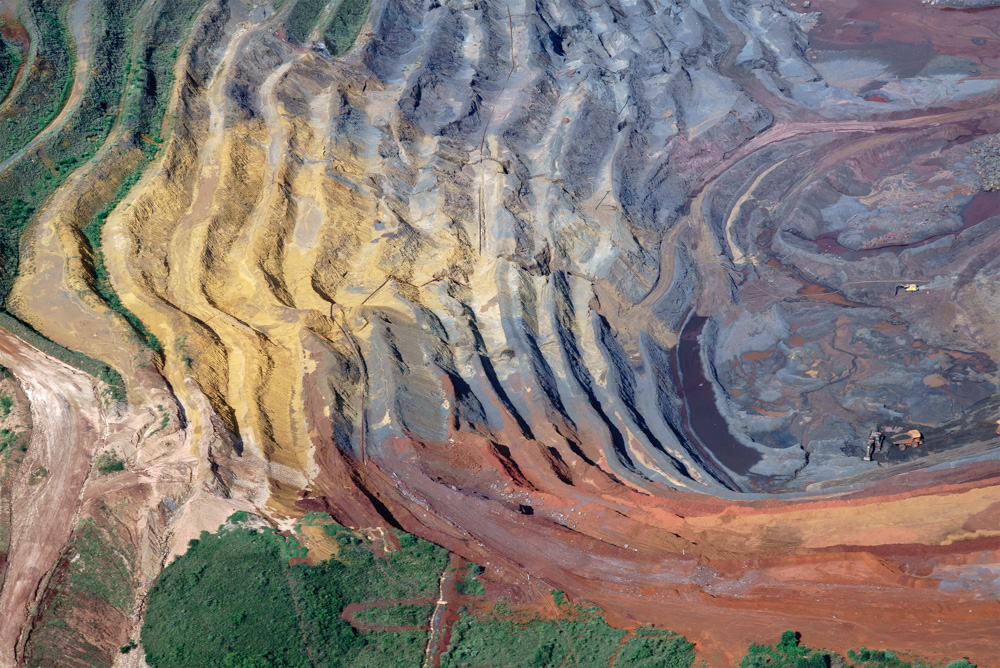

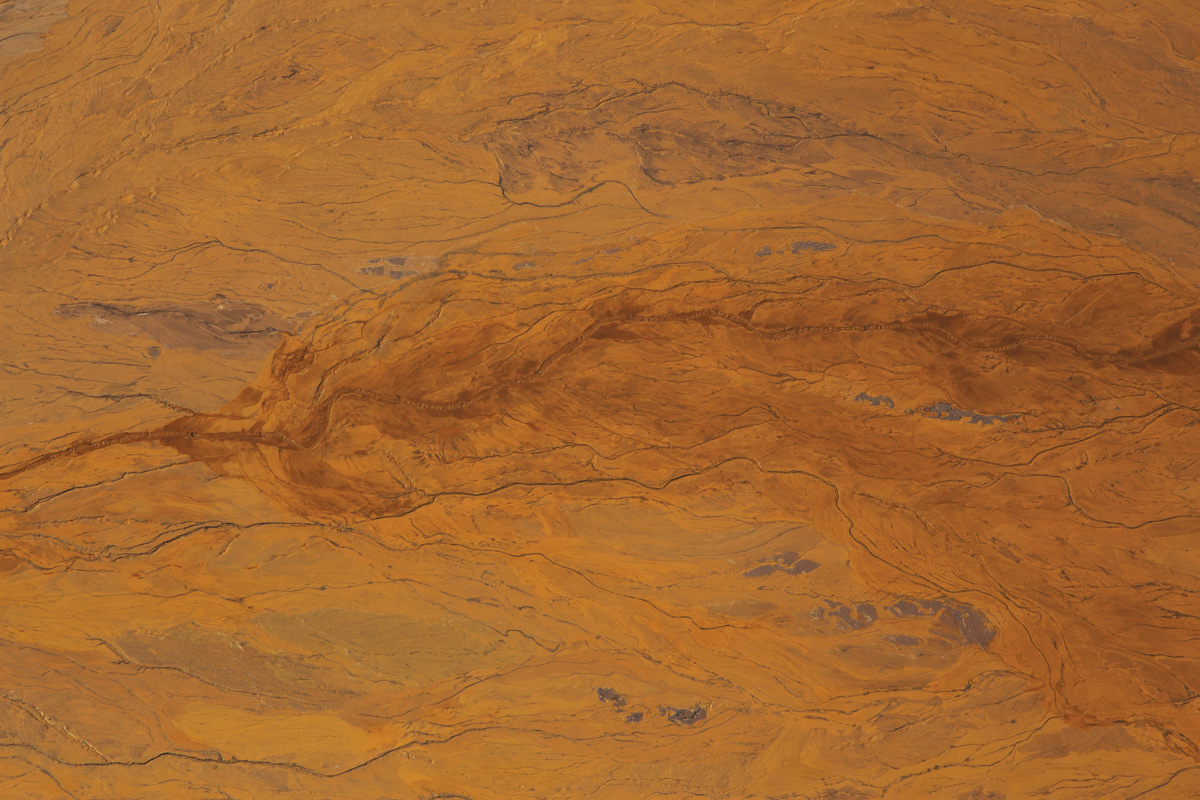

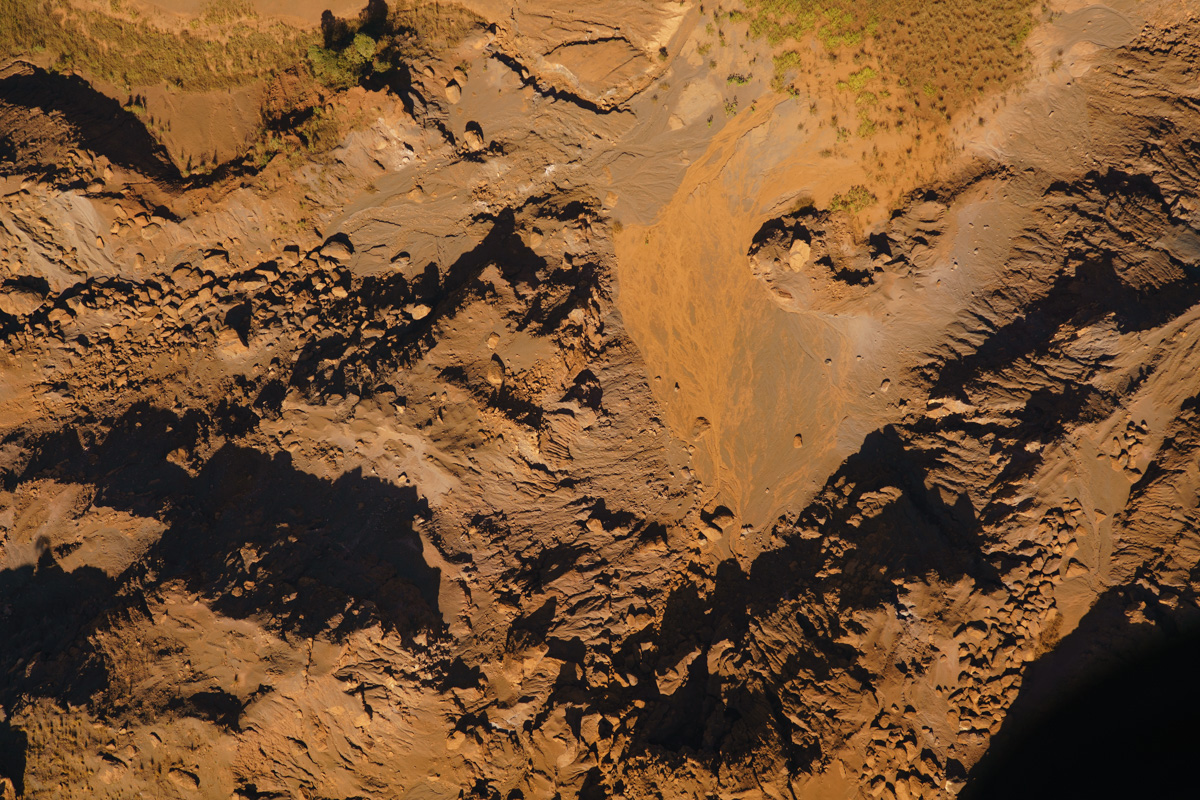

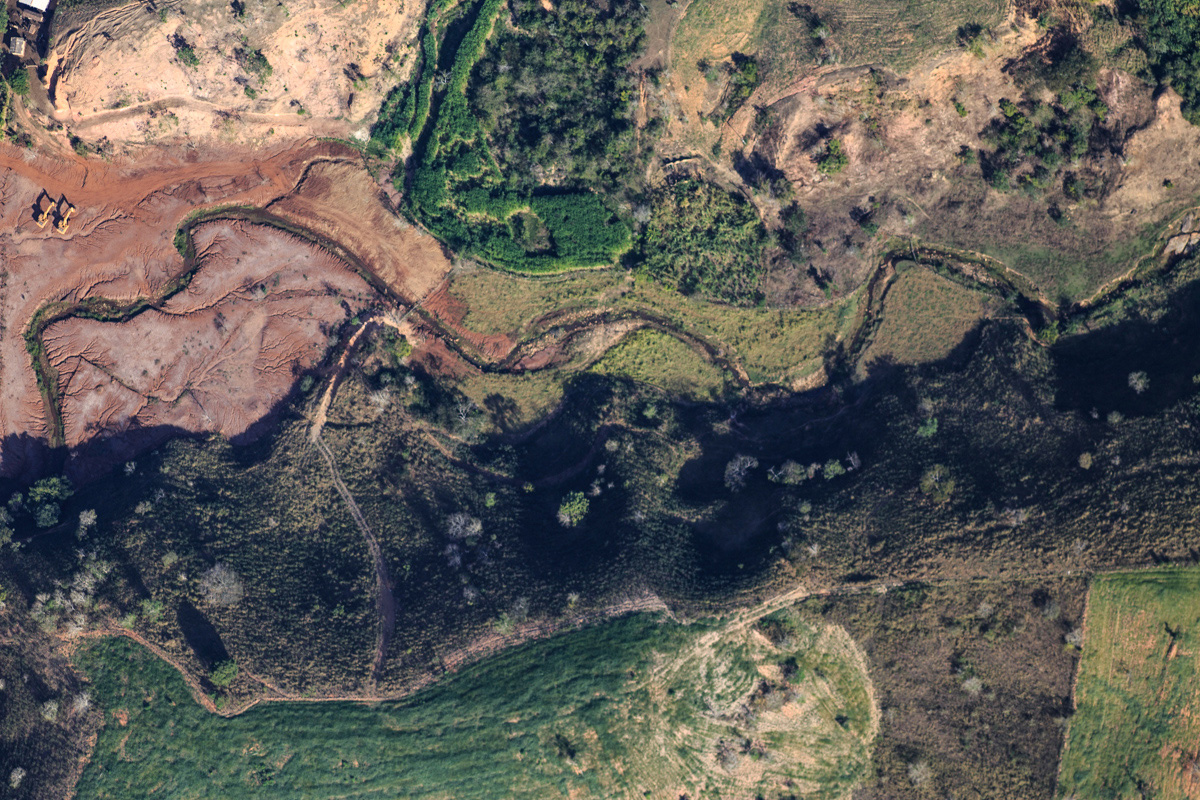

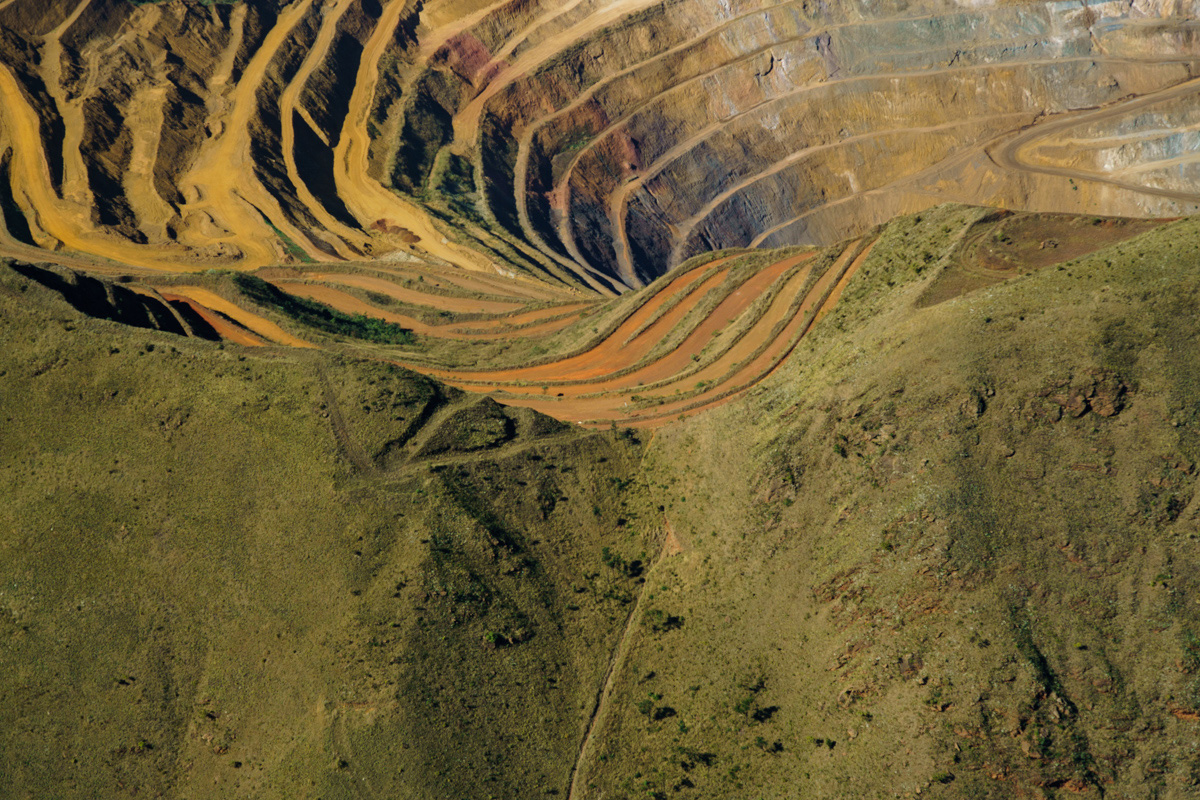

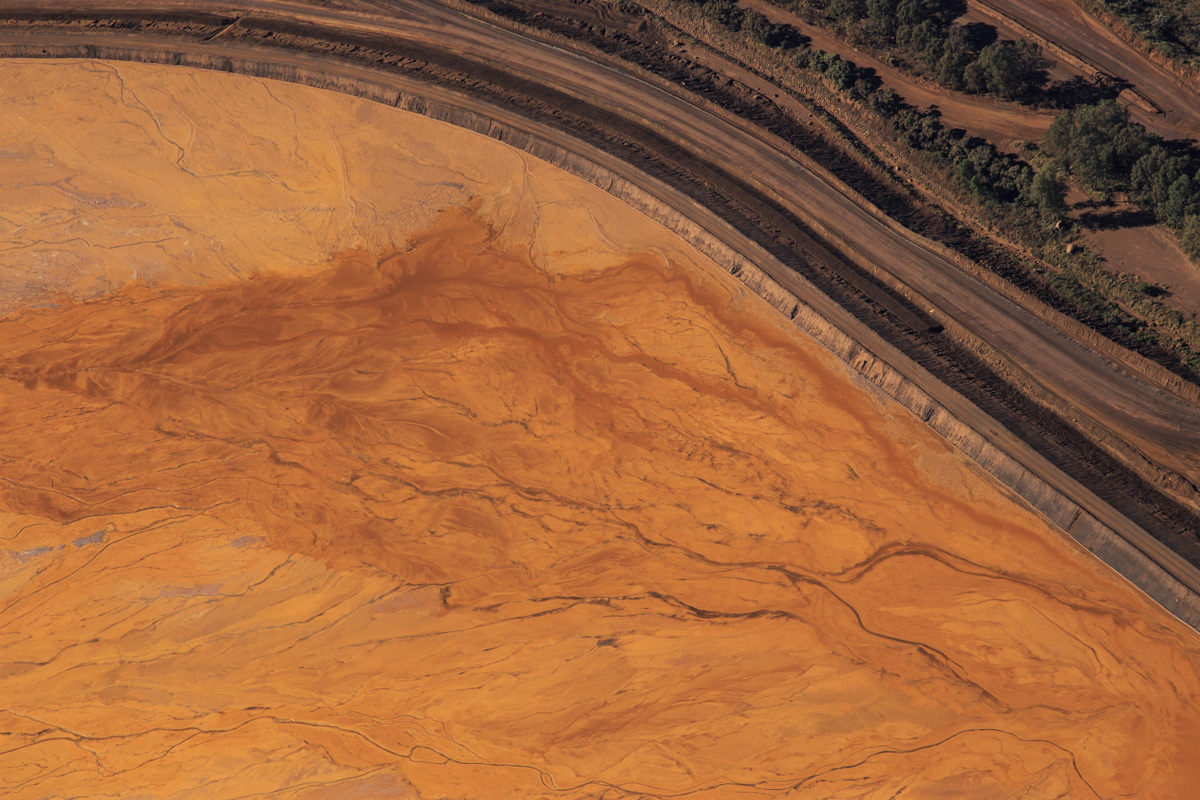

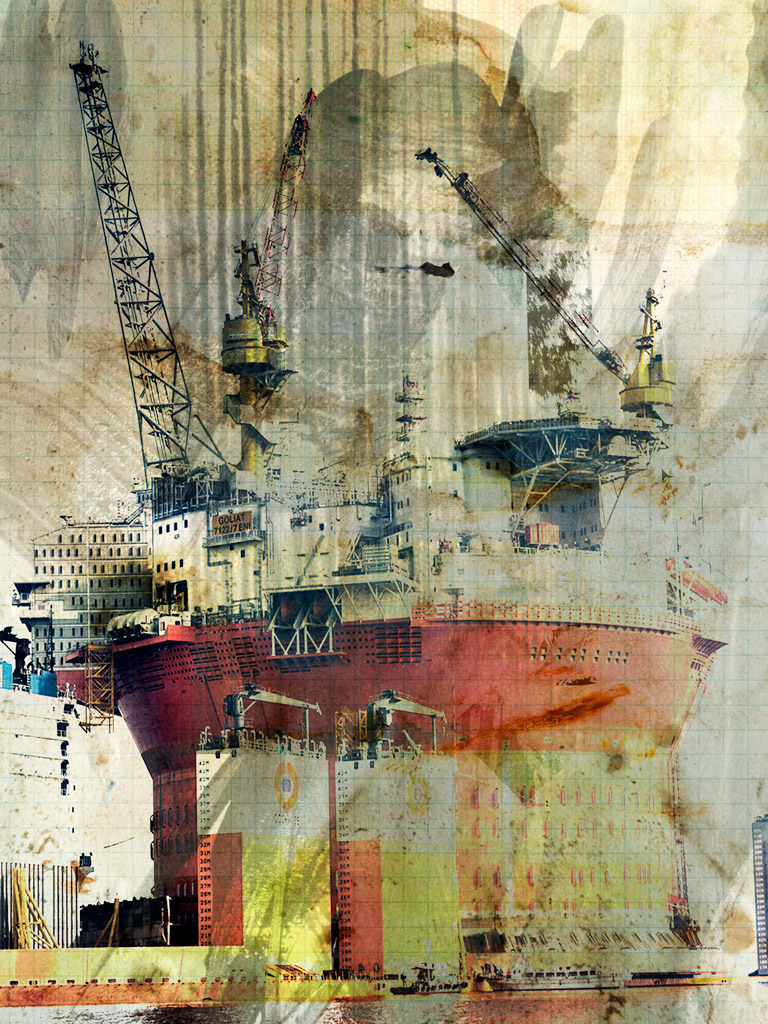

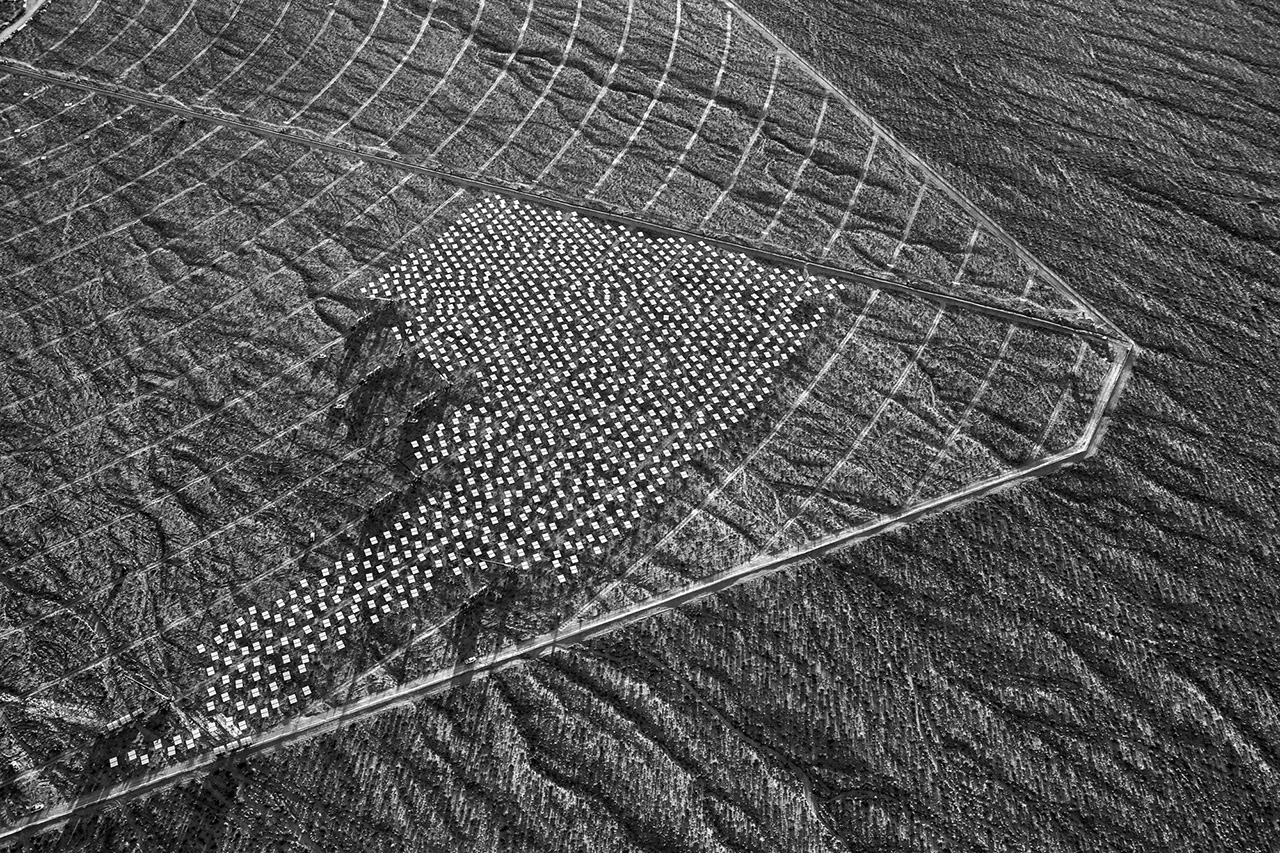

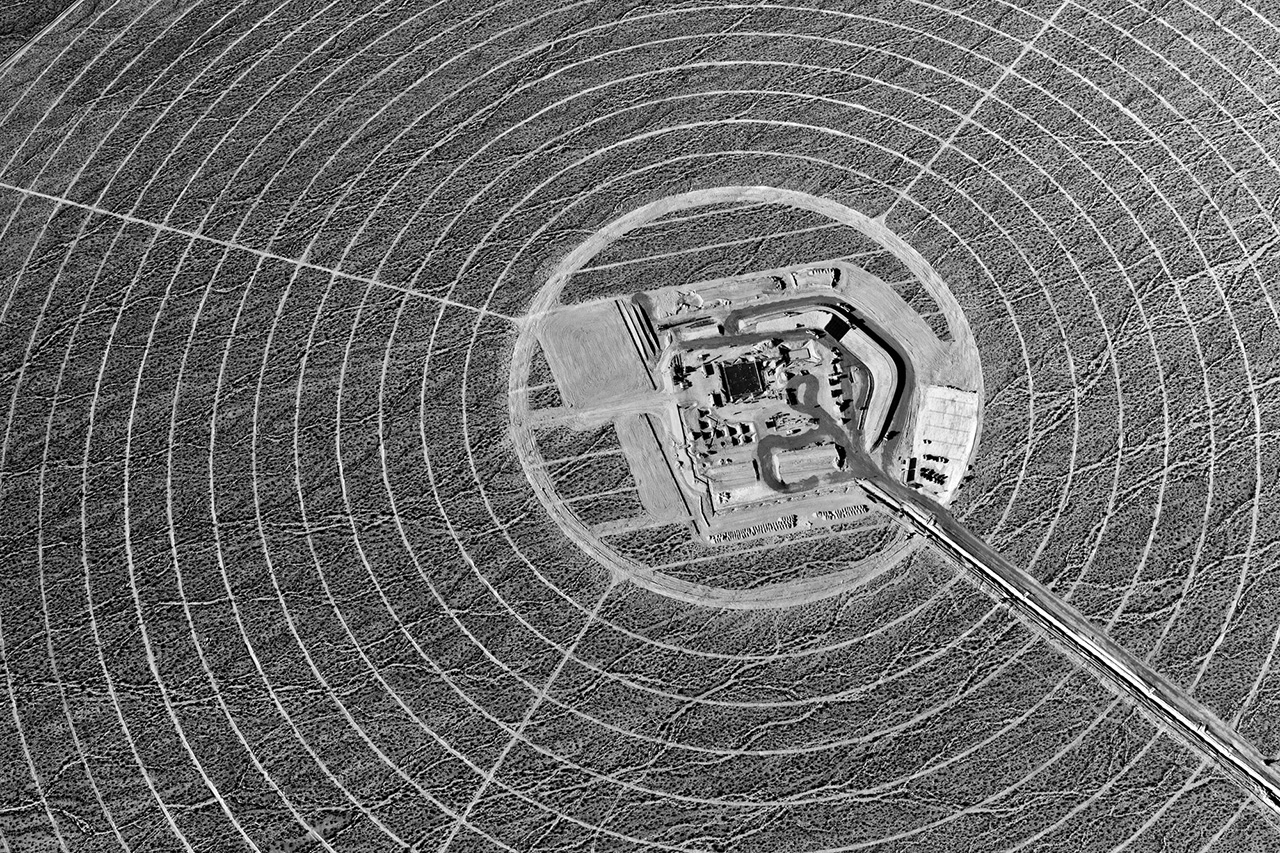

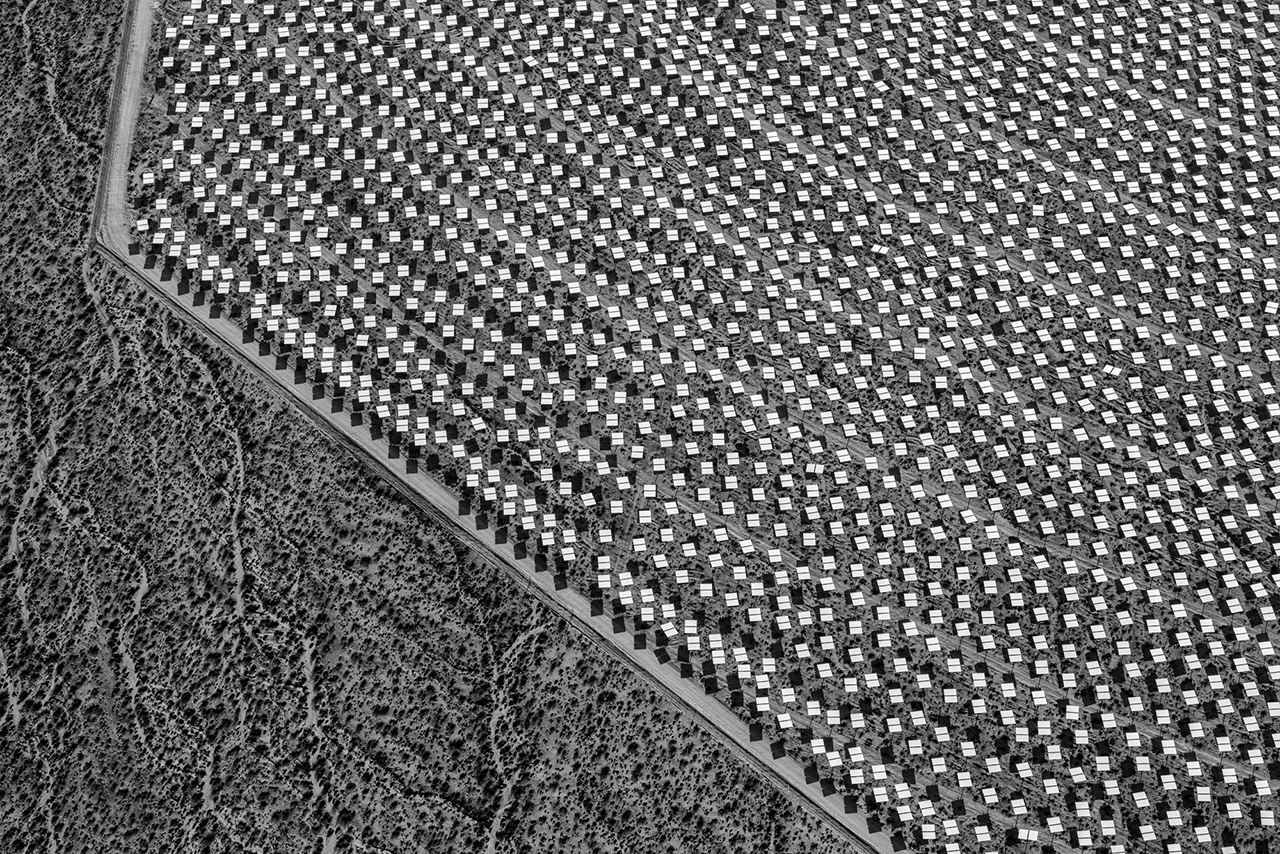

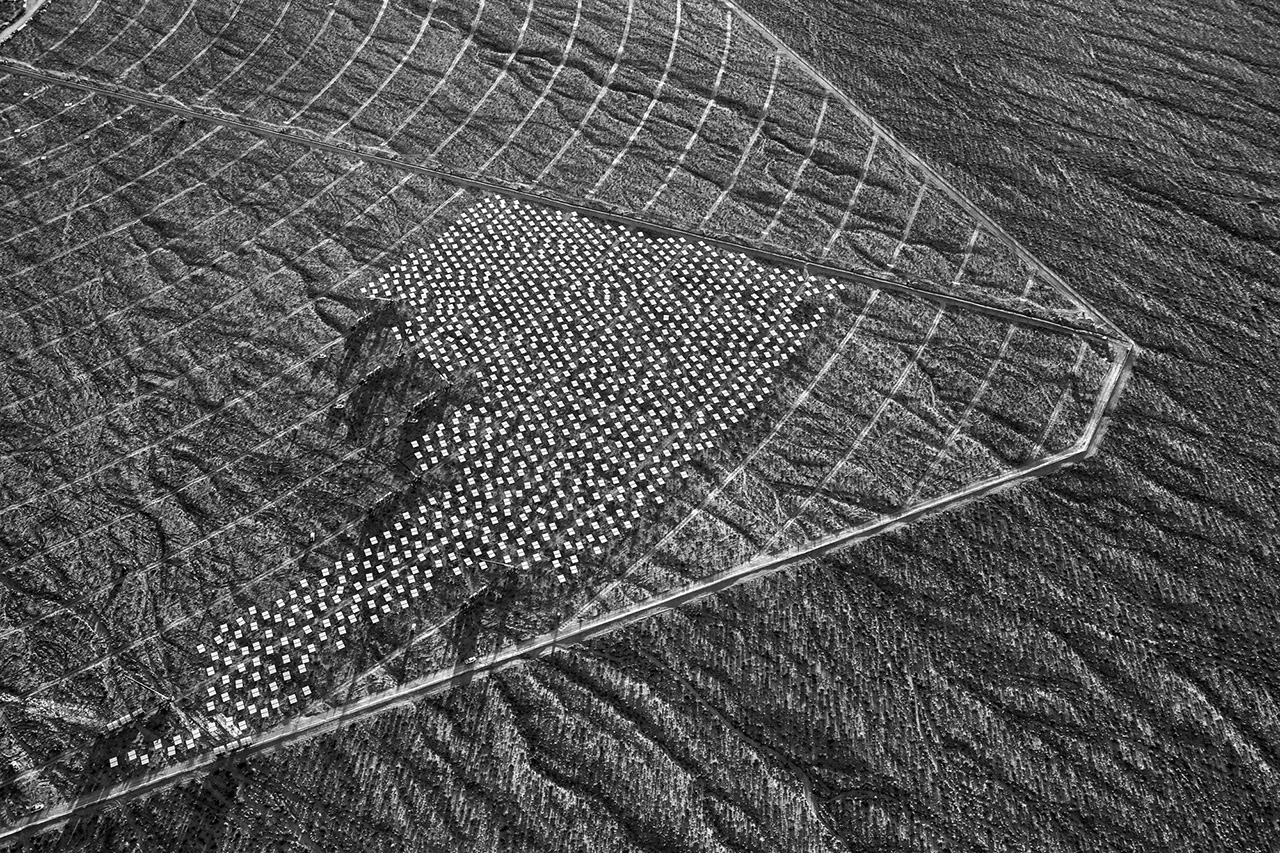

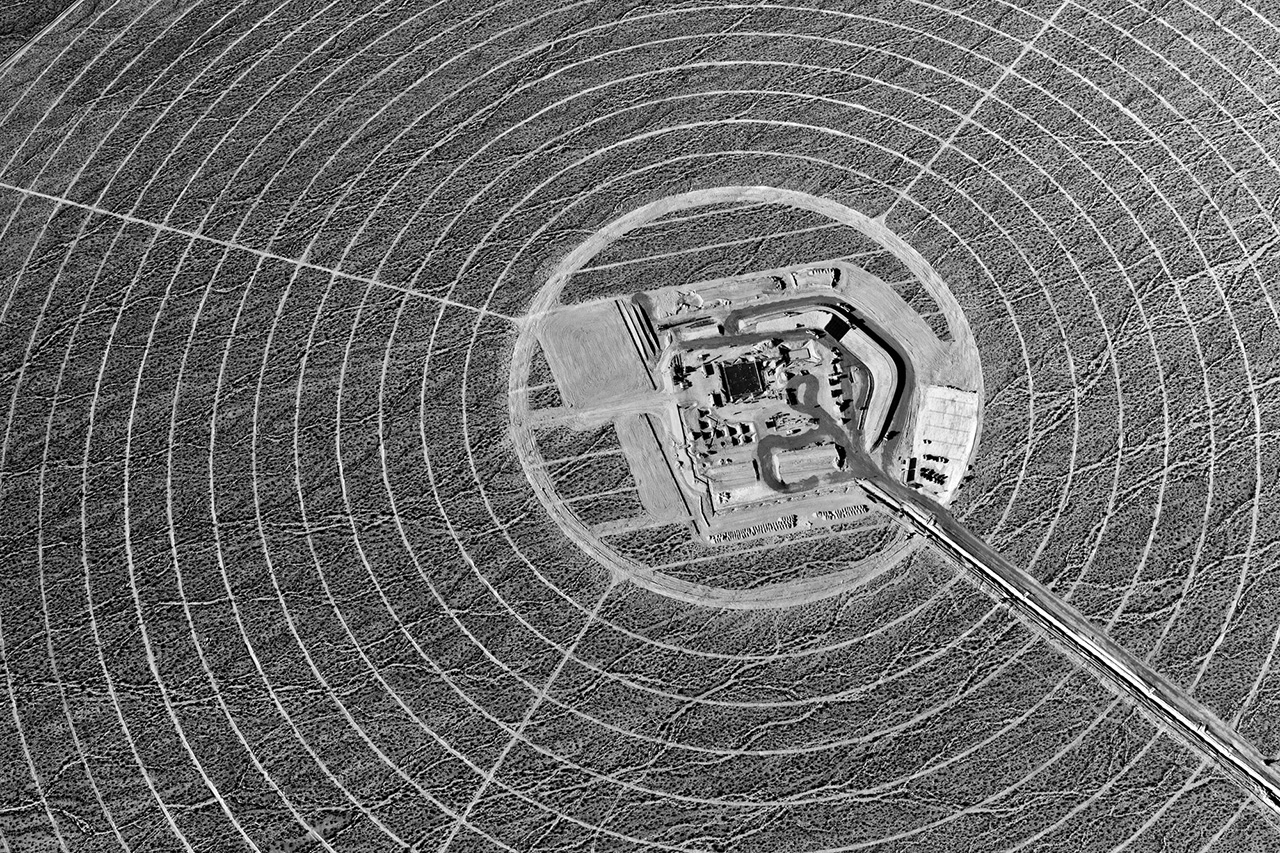

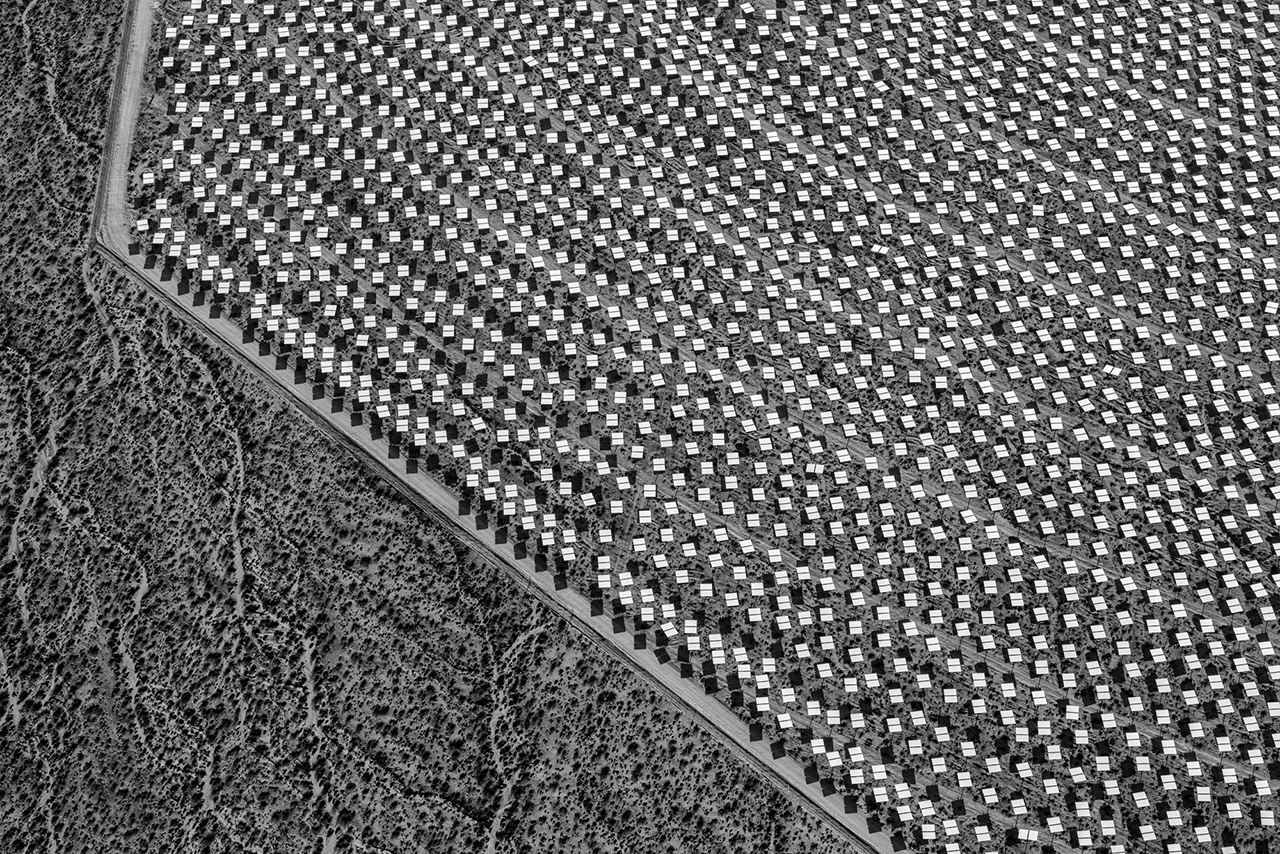

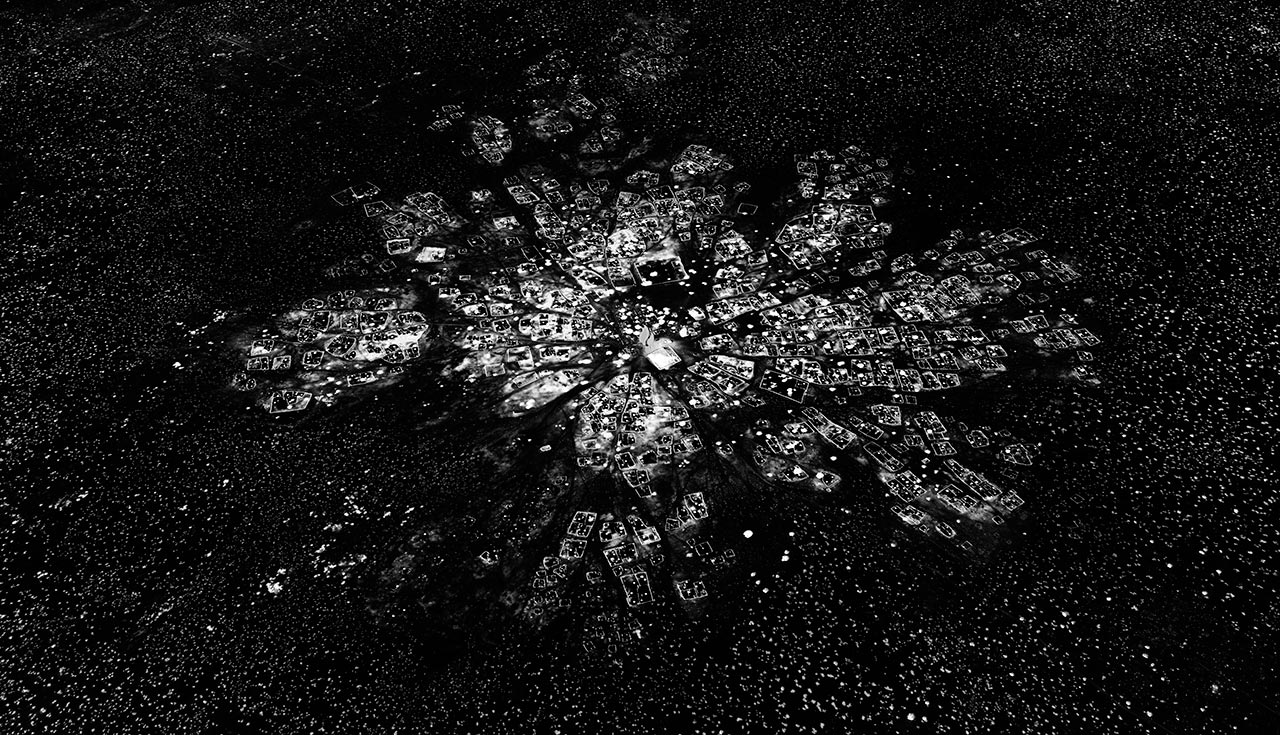

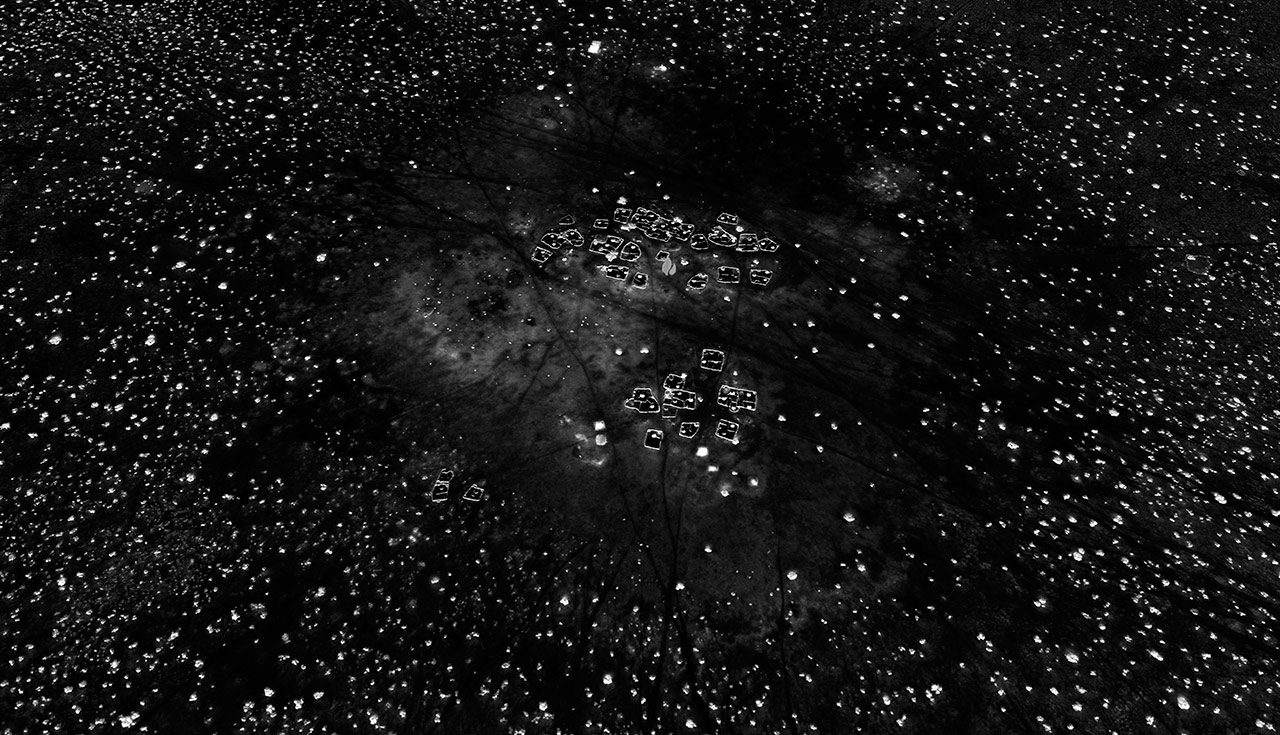

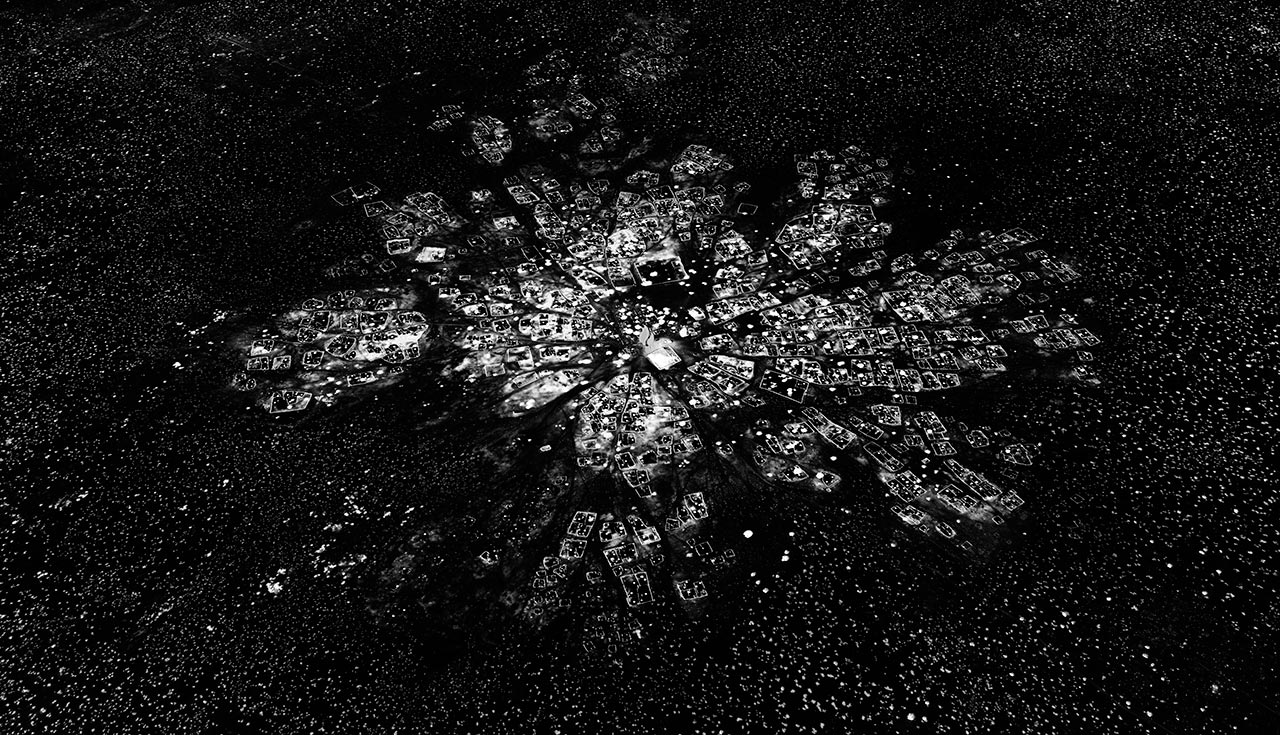

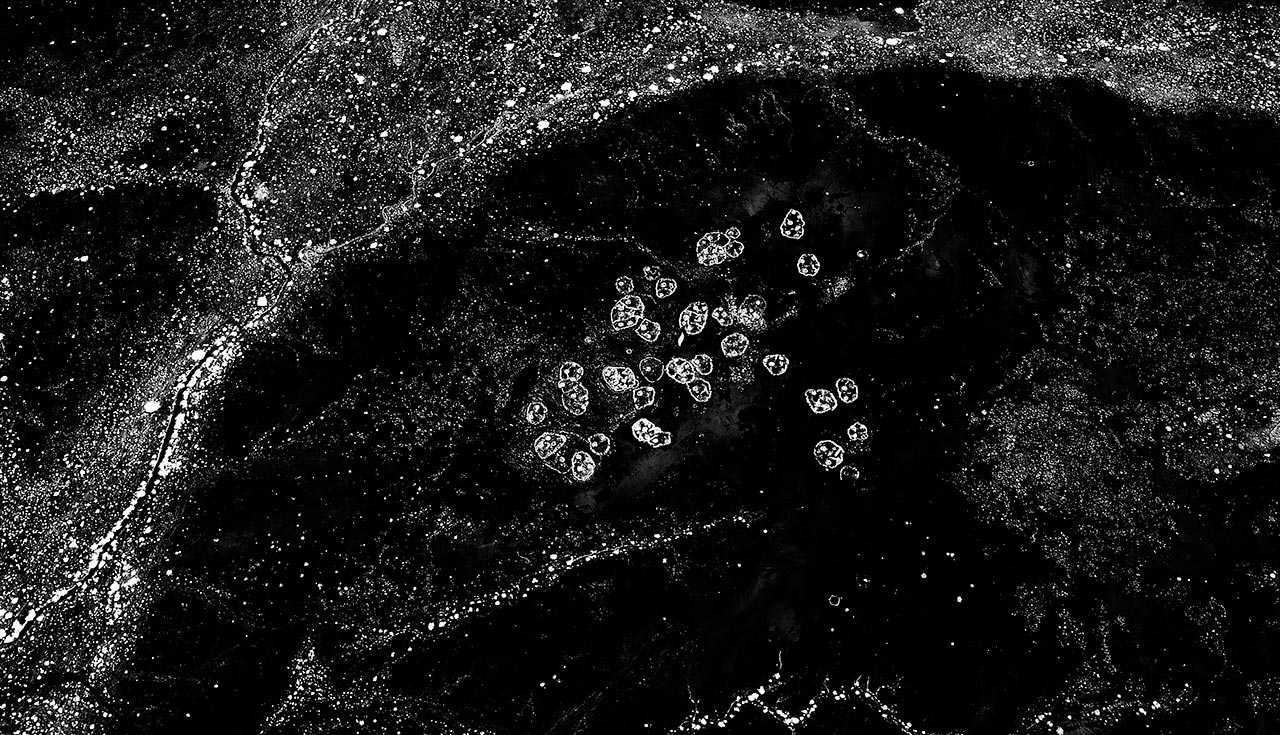

Brazil is facing the largest environmental disaster in its history. Due the lack of specific regulations and low inspection, a mining company’s dam broke throwing 10.5 billion gallons of mud on one of the countries most important rivers and water sheds, covering a whole town and leaving many cities without water.

That breakage served as a groundbreaking for me. While flying over the area I was impressed by the landscape damaged that has been caused by the highly intensive mining activity in the state. Many of the open air mines, are hidden between the state of Minas Gerais’ “mountain” chains , therefore, local population has no sight of its extension. Most of the photographs were taken in a forbidden aerial space, with the plane’s transponder being off.

It is a very delicate subject, mining is the main industry in the state and it is so deeply routed that it is on it’s name. Everyone has a relation to the activity. My family had an iron processing company, one of the multiple stages on the mining commercial chain.

There is a mining regulation bill currently being discussed by Brazilian congressman. 20 out of the 27 congressman responsible for the project received money from mining companies to their campaigns.

This ongoing project is a landscape investigation both of the disaster, the unbounded and poorly regulated use of the soil.

Júlia Pontés (Brazil, 1983).Porteña by choice - Live & work in New York Her interests are influenced by Psychology and Public Policies, in which she holds a Master’s Degree. She graduated at the International Center of Photography and she has been chosen as an Emerging Immigrant Artist by the New York Foundation for the Arts, where she has been a mentee twice. She has a polarized practice that involves documenting stories linked to her own life experiences and, on the other hand, a self portraiture practice. In both she applies experimental techniques, the use of different mediums and archive material.

Júlia Pontés (Brazil, 1983).Porteña by choice - Live & work in New York Her interests are influenced by Psychology and Public Policies, in which she holds a Master’s Degree. She graduated at the International Center of Photography and she has been chosen as an Emerging Immigrant Artist by the New York Foundation for the Arts, where she has been a mentee twice. She has a polarized practice that involves documenting stories linked to her own life experiences and, on the other hand, a self portraiture practice. In both she applies experimental techniques, the use of different mediums and archive material.

Brazil is facing the largest environmental disaster in its history. Due the lack of specific regulations and low inspection, a mining company’s dam broke throwing 10.5 billion gallons of mud on one of the countries most important rivers and water sheds, covering a whole town and leaving many cities without water.

That breakage served as a groundbreaking for me. While flying over the area I was impressed by the landscape damaged that has been caused by the highly intensive mining activity in the state. Many of the open air mines, are hidden between the state of Minas Gerais’ “mountain” chains , therefore, local population has no sight of its extension. Most of the photographs were taken in a forbidden aerial space, with the plane’s transponder being off.

It is a very delicate subject, mining is the main industry in the state and it is so deeply routed that it is on it’s name. Everyone has a relation to the activity. My family had an iron processing company, one of the multiple stages on the mining commercial chain.

There is a mining regulation bill currently being discussed by Brazilian congressman. 20 out of the 27 congressman responsible for the project received money from mining companies to their campaigns.

This ongoing project is a landscape investigation both of the disaster, the unbounded and poorly regulated use of the soil.

Júlia Pontés (Brazil, 1983).Porteña by choice - Live & work in New York Her interests are influenced by Psychology and Public Policies, in which she holds a Master’s Degree. She graduated at the International Center of Photography and she has been chosen as an Emerging Immigrant Artist by the New York Foundation for the Arts, where she has been a mentee twice. She has a polarized practice that involves documenting stories linked to her own life experiences and, on the other hand, a self portraiture practice. In both she applies experimental techniques, the use of different mediums and archive material.

Júlia Pontés (Brazil, 1983).Porteña by choice - Live & work in New York Her interests are influenced by Psychology and Public Policies, in which she holds a Master’s Degree. She graduated at the International Center of Photography and she has been chosen as an Emerging Immigrant Artist by the New York Foundation for the Arts, where she has been a mentee twice. She has a polarized practice that involves documenting stories linked to her own life experiences and, on the other hand, a self portraiture practice. In both she applies experimental techniques, the use of different mediums and archive material.Brad Temkin

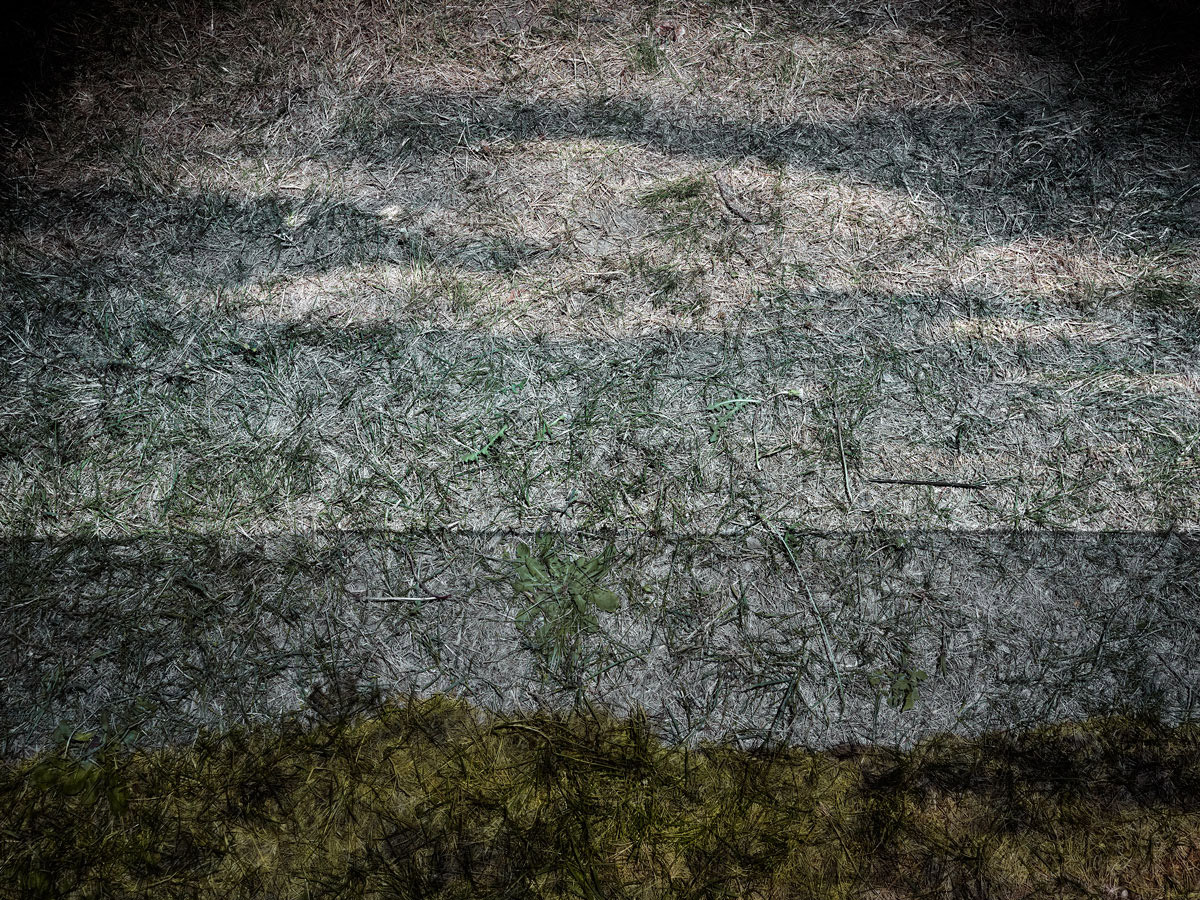

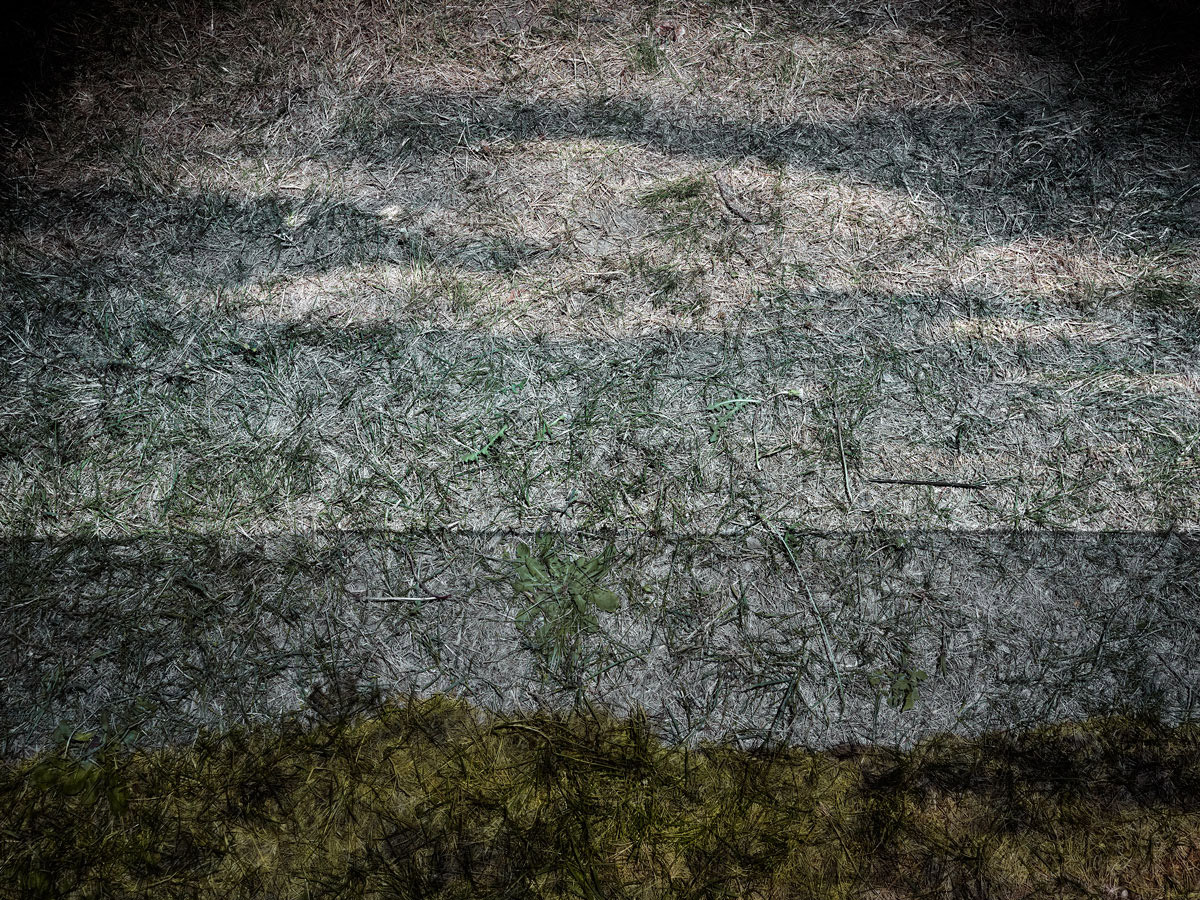

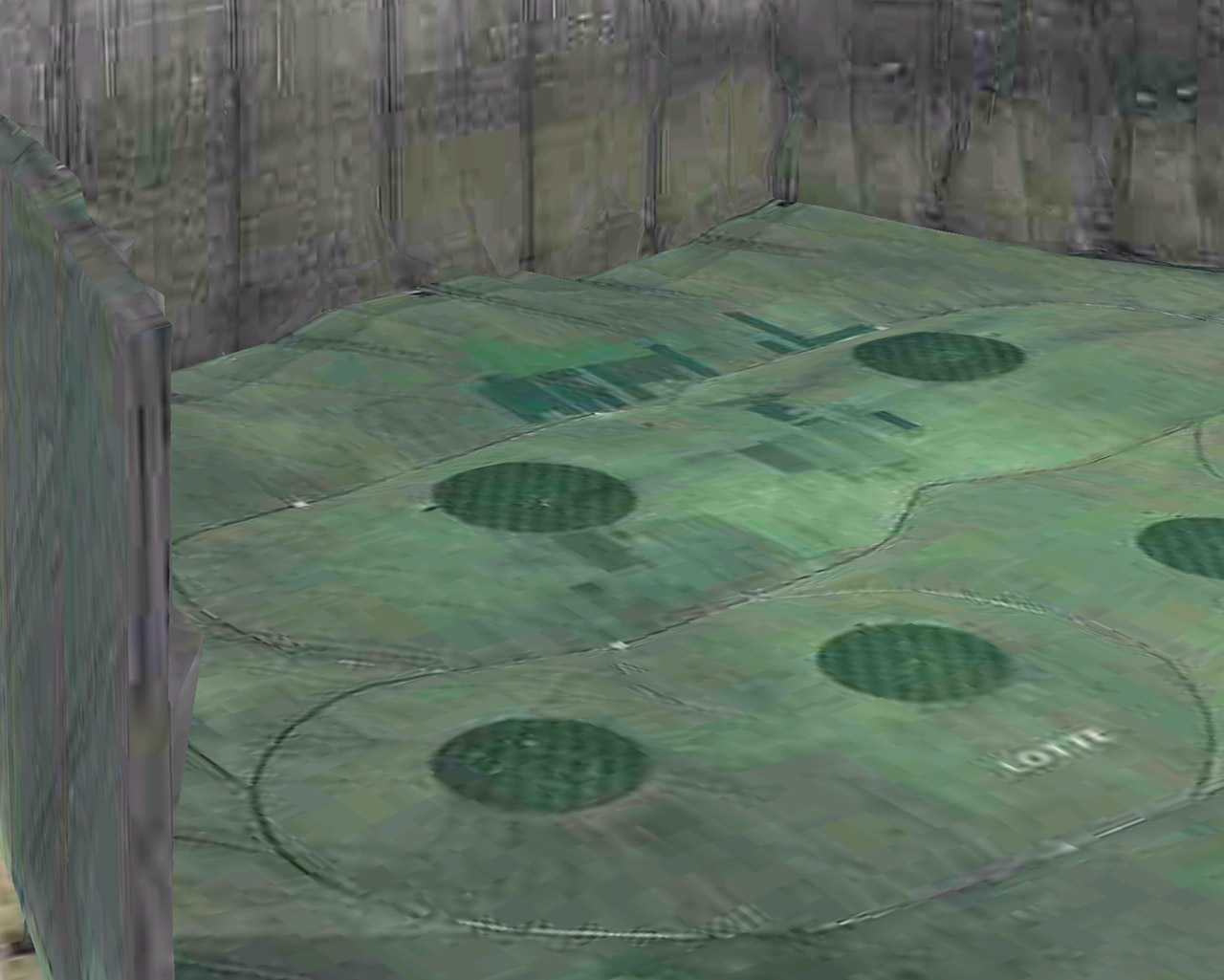

Most of my career has focused on our relationship with nature. I’m interested in how we find ways to accommodate nature, and how it accommodates us. As with most bodies of work, the pictures define my intent. But in the end, I make the pictures I do because of the conversation that occurs between the subject and myself - and this always depends on the light, the weather, how I'm feeling and what I am open to seeing at the moment. It's the moment all things come together for me.

Rooftop draws poetic attention to celebrate and proliferate new ideas in design showing the inventiveness in architecture and accommodating our need for nature. Green roofs reduce our carbon footprint by countering heat island effect and improve storm water control, but they do far more. These pictures symbolize the allure of nature in the face of our continuing urban sprawl. By securely situating the gardens within the steel, stone, and glass rectangularity of urban and industrial buildings, I ask viewers to revel in the far more open patterns, colors, and connection to the sky; and how they become part of a new landscape as well as a framework for positive change. Our ingenuity and grace continues to impress me. It makes me more optimistic about humanity.

Brad Temkin (USA, 1956). Has been documenting the human impact on the landscape. He has exhibited his photographs in museums and galleries throughout the United States and abroad. Temkin’s works are included in numerous permanent collections, including those of The Art Institute of Chicago; Milwaukee Art Museum; Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.; Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; Akron Art Museum, Ohio; and Museum of Contemporary Photography, Chicago, among others. His images have appeared in such publications as Aperture, Black & White Magazine, TIME Magazine and European Photography.

Brad Temkin (USA, 1956). Has been documenting the human impact on the landscape. He has exhibited his photographs in museums and galleries throughout the United States and abroad. Temkin’s works are included in numerous permanent collections, including those of The Art Institute of Chicago; Milwaukee Art Museum; Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.; Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; Akron Art Museum, Ohio; and Museum of Contemporary Photography, Chicago, among others. His images have appeared in such publications as Aperture, Black & White Magazine, TIME Magazine and European Photography.

Most of my career has focused on our relationship with nature. I’m interested in how we find ways to accommodate nature, and how it accommodates us. As with most bodies of work, the pictures define my intent. But in the end, I make the pictures I do because of the conversation that occurs between the subject and myself - and this always depends on the light, the weather, how I'm feeling and what I am open to seeing at the moment. It's the moment all things come together for me.

Rooftop draws poetic attention to celebrate and proliferate new ideas in design showing the inventiveness in architecture and accommodating our need for nature. Green roofs reduce our carbon footprint by countering heat island effect and improve storm water control, but they do far more. These pictures symbolize the allure of nature in the face of our continuing urban sprawl. By securely situating the gardens within the steel, stone, and glass rectangularity of urban and industrial buildings, I ask viewers to revel in the far more open patterns, colors, and connection to the sky; and how they become part of a new landscape as well as a framework for positive change. Our ingenuity and grace continues to impress me. It makes me more optimistic about humanity.

Brad Temkin (USA, 1956). Has been documenting the human impact on the landscape. He has exhibited his photographs in museums and galleries throughout the United States and abroad. Temkin’s works are included in numerous permanent collections, including those of The Art Institute of Chicago; Milwaukee Art Museum; Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.; Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; Akron Art Museum, Ohio; and Museum of Contemporary Photography, Chicago, among others. His images have appeared in such publications as Aperture, Black & White Magazine, TIME Magazine and European Photography.

Brad Temkin (USA, 1956). Has been documenting the human impact on the landscape. He has exhibited his photographs in museums and galleries throughout the United States and abroad. Temkin’s works are included in numerous permanent collections, including those of The Art Institute of Chicago; Milwaukee Art Museum; Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.; Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; Akron Art Museum, Ohio; and Museum of Contemporary Photography, Chicago, among others. His images have appeared in such publications as Aperture, Black & White Magazine, TIME Magazine and European Photography.Pedro David

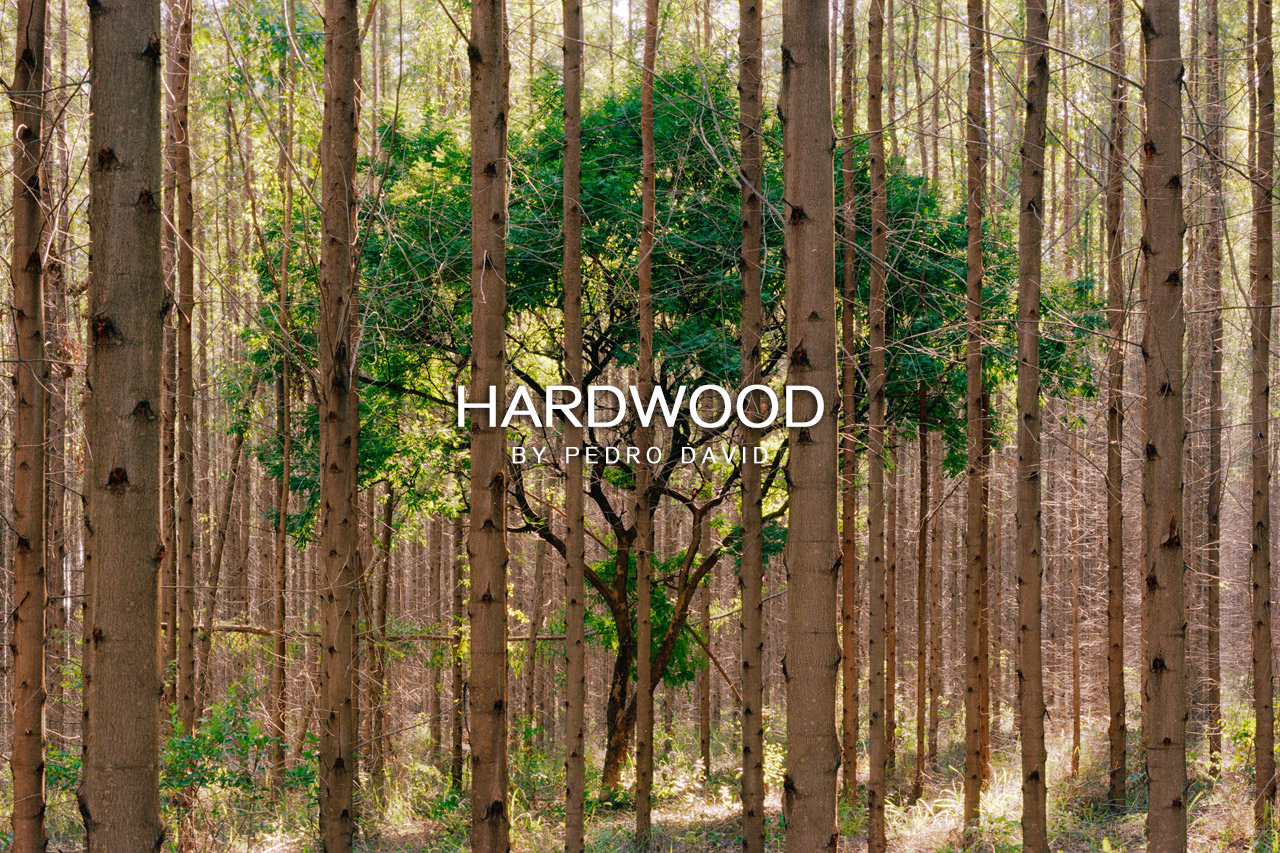

Brazillian country side is being filled with eucalyptus.

The accelerated industrial development and the overtuned importance of steel exportation, lead by sucessive governments, are one of the reasons of the deforestation of the Cerrado, the Brazillian savana, the Atlantic Forest, and even the Amazon.

Several international steel companies, established by the country, buys large portions of land and substitutes the natural vegetation by transgenic eucalyptus trees, a fast growing kind of wood, used to make vegetal coal, an important ingredient in the tranformation of the iron ore to steel.

The eucalyptus charges high the environment for it’s fast growing speed: it consumes too much water and nutrients, leaving the soil exhausted and dry.

I’m working in some regions affected by these monocrops since my beginning as a photographer. The extensive and visually growing areas of the eucaliptus fields always concerned me, because of the environmental and also social impact it brings, changing the landscape as a whole, the geographical references, the natural resources, the economical activities, and the amount of water, now a global issue. I’ve ridden, and walked, a lot inside these fields since 2002.

I’ve photographed several situations trying to discuss this question in the last 13 years. But when, in a recent travel, I passed by road swallowed by an enormous eucaliptus field, I faced one of this hybrid scenes and saw the opportunity to make a representative image of the situation, a straight photograph containing: the past, a native tree, something that is desappearing of those landscapes, the future: those supra-vegetal, eucaliptus clones, in the present of the photography.

Besides this documentary facet, that is being effective to sensibilize people of the problem of the extensive growing of this and other kinds of monocrops, a basic Brazillian problem, I also see this work in a simbolic way. I note that people feel something beyond the direct meaning of these photographs, something like a direct identification with these encaged lifes, struggling to survive in an artificial, oppressive and vanishing world.

Pedro David (Brazil, 1977). He graduated in journalism in 2002. His works are in public and private photographic collections. He has received the Situações Brasília Contemporary Art Prize in 2012 and 2014; Conrado Wessel Foundation Prize of Photography, in 2013, Itamaraty Prize for Contemporary Art in 2012 and 2013; Arte Pará Prize in 2012; Pierre Verger Prize of Photography, in 2011; Latin Union - Martín Chambi Protography Prize, in 2010, and the 5thPorto Seguro Brasil Award. He has published the books: Fase Catarse (Catharsis Phase), 2014; Rota Raiz (Route Root) Tempo D’Imagem, 2013; O Jardim (The Garden) Funceb, 2012 and Paisagem Submersa (Underwater Landscape) Cosac Naify, 2008.

Pedro David (Brazil, 1977). He graduated in journalism in 2002. His works are in public and private photographic collections. He has received the Situações Brasília Contemporary Art Prize in 2012 and 2014; Conrado Wessel Foundation Prize of Photography, in 2013, Itamaraty Prize for Contemporary Art in 2012 and 2013; Arte Pará Prize in 2012; Pierre Verger Prize of Photography, in 2011; Latin Union - Martín Chambi Protography Prize, in 2010, and the 5thPorto Seguro Brasil Award. He has published the books: Fase Catarse (Catharsis Phase), 2014; Rota Raiz (Route Root) Tempo D’Imagem, 2013; O Jardim (The Garden) Funceb, 2012 and Paisagem Submersa (Underwater Landscape) Cosac Naify, 2008.

Brazillian country side is being filled with eucalyptus.

The accelerated industrial development and the overtuned importance of steel exportation, lead by sucessive governments, are one of the reasons of the deforestation of the Cerrado, the Brazillian savana, the Atlantic Forest, and even the Amazon.

Several international steel companies, established by the country, buys large portions of land and substitutes the natural vegetation by transgenic eucalyptus trees, a fast growing kind of wood, used to make vegetal coal, an important ingredient in the tranformation of the iron ore to steel.

The eucalyptus charges high the environment for it’s fast growing speed: it consumes too much water and nutrients, leaving the soil exhausted and dry.

I’m working in some regions affected by these monocrops since my beginning as a photographer. The extensive and visually growing areas of the eucaliptus fields always concerned me, because of the environmental and also social impact it brings, changing the landscape as a whole, the geographical references, the natural resources, the economical activities, and the amount of water, now a global issue. I’ve ridden, and walked, a lot inside these fields since 2002.

I’ve photographed several situations trying to discuss this question in the last 13 years. But when, in a recent travel, I passed by road swallowed by an enormous eucaliptus field, I faced one of this hybrid scenes and saw the opportunity to make a representative image of the situation, a straight photograph containing: the past, a native tree, something that is desappearing of those landscapes, the future: those supra-vegetal, eucaliptus clones, in the present of the photography.

Besides this documentary facet, that is being effective to sensibilize people of the problem of the extensive growing of this and other kinds of monocrops, a basic Brazillian problem, I also see this work in a simbolic way. I note that people feel something beyond the direct meaning of these photographs, something like a direct identification with these encaged lifes, struggling to survive in an artificial, oppressive and vanishing world.

Pedro David (Brazil, 1977). He graduated in journalism in 2002. His works are in public and private photographic collections. He has received the Situações Brasília Contemporary Art Prize in 2012 and 2014; Conrado Wessel Foundation Prize of Photography, in 2013, Itamaraty Prize for Contemporary Art in 2012 and 2013; Arte Pará Prize in 2012; Pierre Verger Prize of Photography, in 2011; Latin Union - Martín Chambi Protography Prize, in 2010, and the 5thPorto Seguro Brasil Award. He has published the books: Fase Catarse (Catharsis Phase), 2014; Rota Raiz (Route Root) Tempo D’Imagem, 2013; O Jardim (The Garden) Funceb, 2012 and Paisagem Submersa (Underwater Landscape) Cosac Naify, 2008.

Pedro David (Brazil, 1977). He graduated in journalism in 2002. His works are in public and private photographic collections. He has received the Situações Brasília Contemporary Art Prize in 2012 and 2014; Conrado Wessel Foundation Prize of Photography, in 2013, Itamaraty Prize for Contemporary Art in 2012 and 2013; Arte Pará Prize in 2012; Pierre Verger Prize of Photography, in 2011; Latin Union - Martín Chambi Protography Prize, in 2010, and the 5thPorto Seguro Brasil Award. He has published the books: Fase Catarse (Catharsis Phase), 2014; Rota Raiz (Route Root) Tempo D’Imagem, 2013; O Jardim (The Garden) Funceb, 2012 and Paisagem Submersa (Underwater Landscape) Cosac Naify, 2008.Max de Esteban

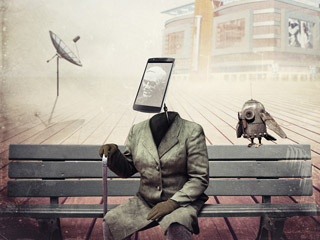

ZZ. What led you to appropriation and remix and how are they significant in your work?

M. Appropriation and remix have a long artistic tradition, beginning with Picasso’s collages. As early as the 1920s, Hannah Hoch and the Dadaists used this mode of expression to create major photographic works. In music, for example, from today’s DJs and Pop to Glenn Gould and Miles Davis, the practice of remix, collage and appropriation has been an essential part of their production. What I mean is that as an artistic concept, appropriation and remix are pretty standard and not particularly groundbreaking.

The interesting question is why their aesthetic power has been reasserted in photography precisely now. And I think one possible answer would be the combination of the formal exhaustion of the linear perspective as a photographic representation of the world and the huge impact digitization is having on every aspect of our lives. I would answer your question by turning it around and saying I find it hard to think of a truly relevant form of photography for the world we live in that continues to respect the Eurocentric, reactionary structure of the dark room.

ZZ. What do you mean by Eurocentric and reactionary?

M. The linear perspective, the visual structure resulting from the dark room, is a very particular and ideological way of visualizing the world. Panofsky has a text about it he wrote in 1927, a real classic, that is a pleasure to read.

But what is really remarkable is that it is an exception in art history. In 10,000 years of history, the linear perspective spans only 500 years and is located exclusively in the West. It has never been of interest to Asian, or pre-Columbian or African art ... it is a European way of seeing in a period beginning in the Renaissance and ending in the 19th century.

And this is no coincidence because its ideological content is well known. The linear perspective arranges the world from the point of view of an autonomous individual whose individuality is the world’s principle of meaning. It is pure Descartes. And we all remember Descartes’ Fifth Meditation, which states that since the essence of matter is its extension, geometry is an essential instrument for understanding nature. Modernity can be defined as the advance of abstraction and the prevalence of the quantitative over the qualitative in which the mathematical-scientific order is regarded as the only source of valid knowledge. There is so much contemporary thought that debunks this narrative that I won't repeat it here.

Thus, surprisingly, my earlier comment is still valid. Why should digital photography continue giving priority to a functionally and ideologically devalued visual structure?

ZZ. Why do you think digital photography changes the way we understand appropriation and remix?

M. Digital technologies are leading us towards the radical transformation of our world. By replacing the industrial economy with a bio-cybernetic system, digitization is modifying our environment, our subjectivity and soon, our bodies. This is the technological phenomenon that will define our era and therefore our culture.

Unlike an analog file, a digital file is invisible. It is a code whose visual expression is a translation highly mediated by default algorithms, whose most prominent feature is precisely its immateriality.

This technical structure fits our current era of abstraction and non-referentiality and the digital financialization of the economy. How do we see the world today? We have the answer on our computer and Smartphone screens. What is the essential aspect of the financial economy? The recombination of existing information units to create new information, in other words, “constructive compositing”. Digitization has definitively invalidated linear narrative, the monocular perspective and the author’s “authority”.

ZZ. You attach a great deal of importance to the concept of technology in your work. Could you explain why?

M. We are moving towards a world as a “technological whole”. Technical manipulation has already invaded our bodies, the last frontier, and no-one doubts that having machines inside our bodies will soon become commonplace.

The cyborg raises more complex issues for our species, which, though somewhat deteriorated, continues to maintain the autonomy of the subject as an essential value. Abstraction, digitization and cyborg are three sides of the same coin that heralds our new world, whether we like it or not. In my opinion, reflecting on technology is necessary, urgent and politically essential.

ZZ. And how do you think technology affects the practice of photography?

M. I’d like to point something out. One of the problems of photography is the confusion between technology and use. Writing is a communication technology that serve to draw up a commercial contract and compose a poem by Virgil. It is the same technology but nobody would ever mistake Virgil for a notary. In photography, we tend to combine uses, which creates enormous confusion in critical discourse. Throughout this interview, I have been referring to the use of photography as a means of artistic expression.

The thing is that photography has always been halfway to a cyborg. It is a machine that affects and to some extent determines human power, thought and expression and is therefore an ideal place for reflecting on the issues I mentioned earlier.

To give you an example: How can you visually depict the abstraction of the economy when the material references of wealth have been replaced by a binary code? That’s what I’m doing at the moment and it forces me to rethink what “representation” means in this new visual regime.

Another example: How does the idea of the cyborg affect art categories? That’s the topic I try to get my teeth into in the text “Cyborg Art: art in the bio-cybernetic era”. And there are a thousand other possible ideas that make photography an exciting medium at this particular historical time. The point is that if photographic practice does not take up the challenge raised by contemporaneity, it will be relegated to banality and antique shops.

ZZ. How do you choose the sources you use and what significance do they have for your series?

M. Like nearly everything in life, it is a combination of determination and chance. In my case, too much planning and/or reflection in my work paralyzes me while dreams or rather daydreams are of paramount importance.

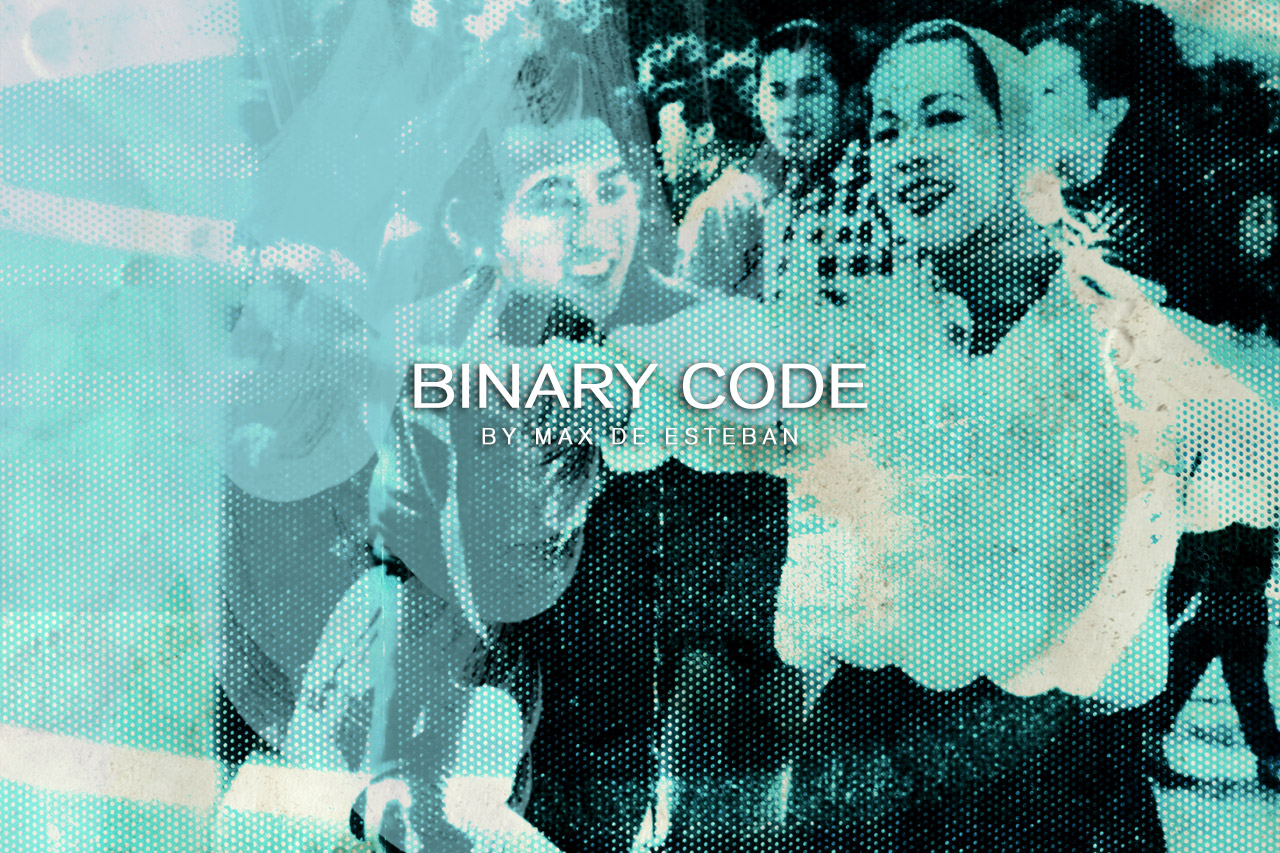

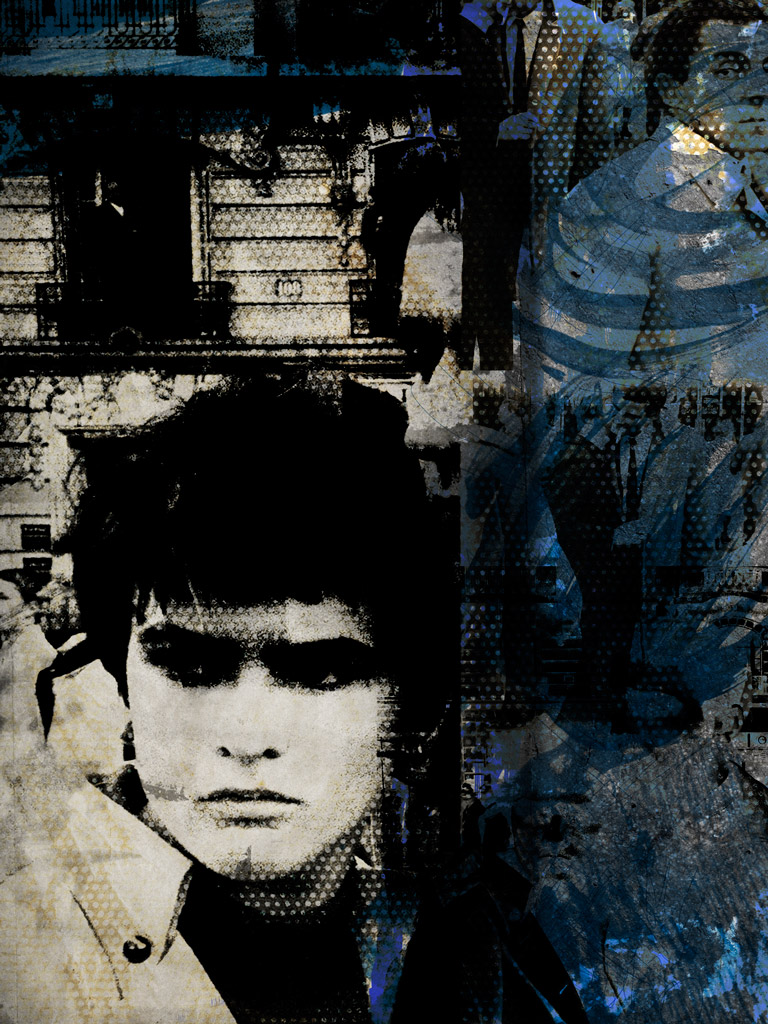

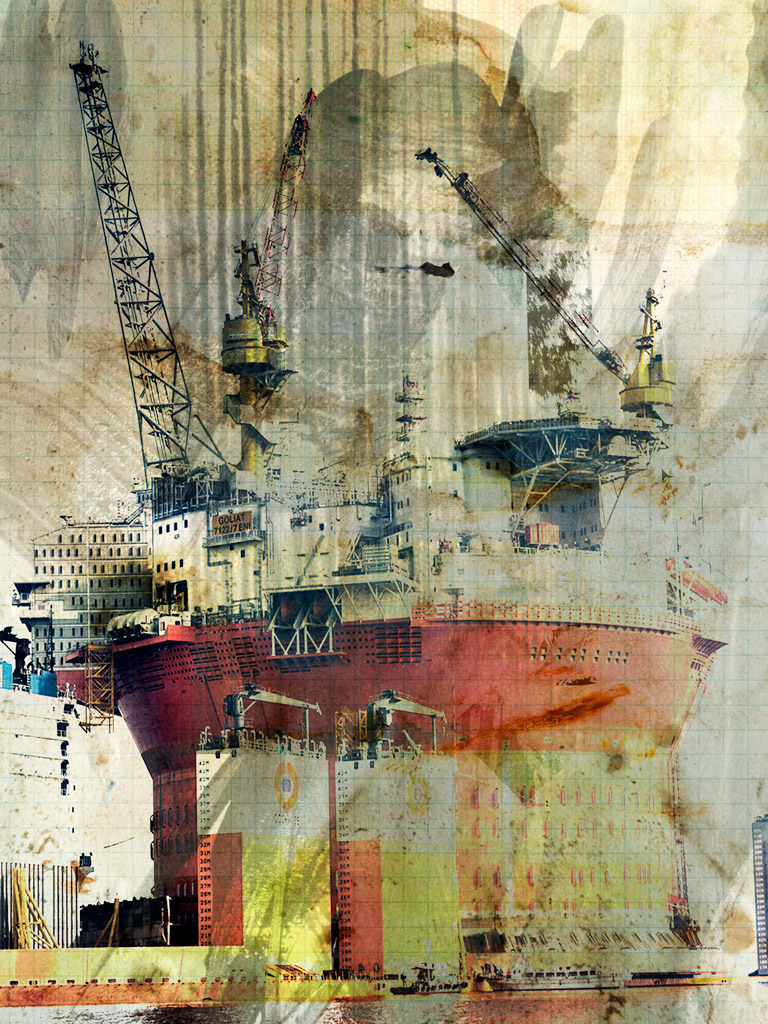

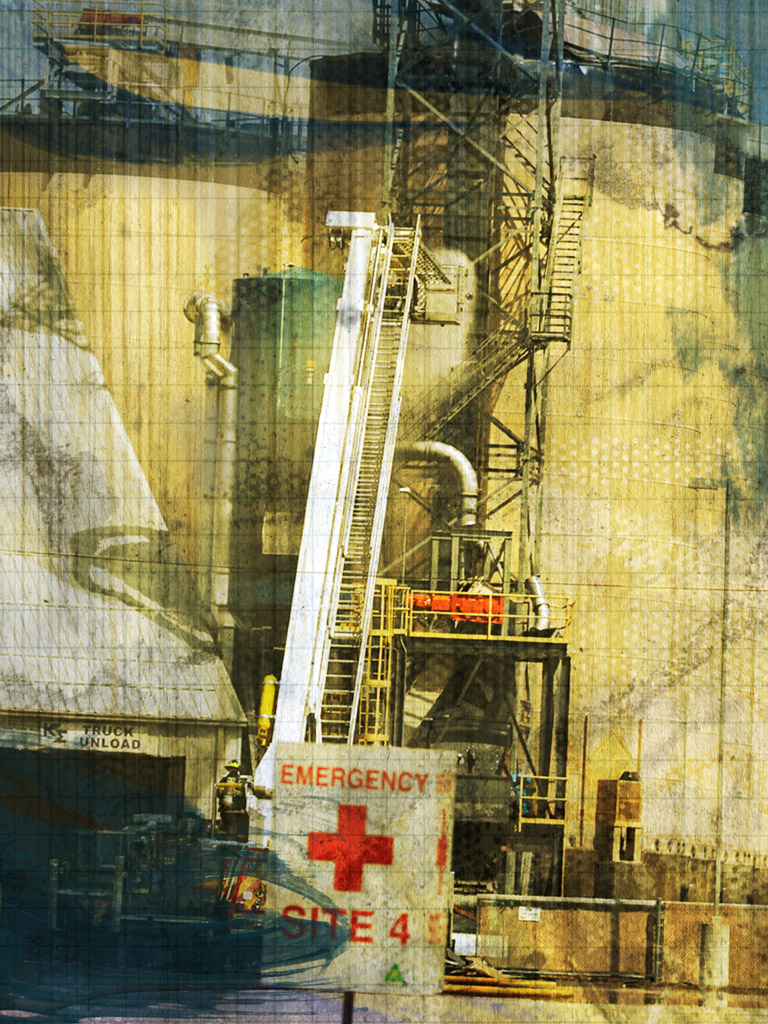

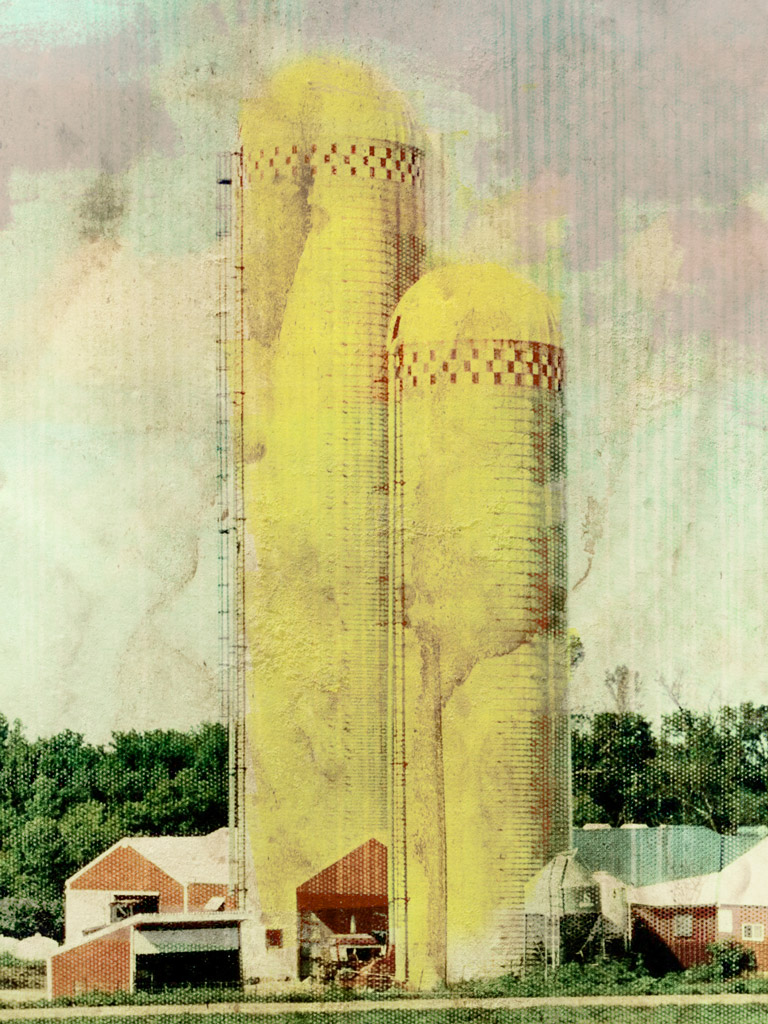

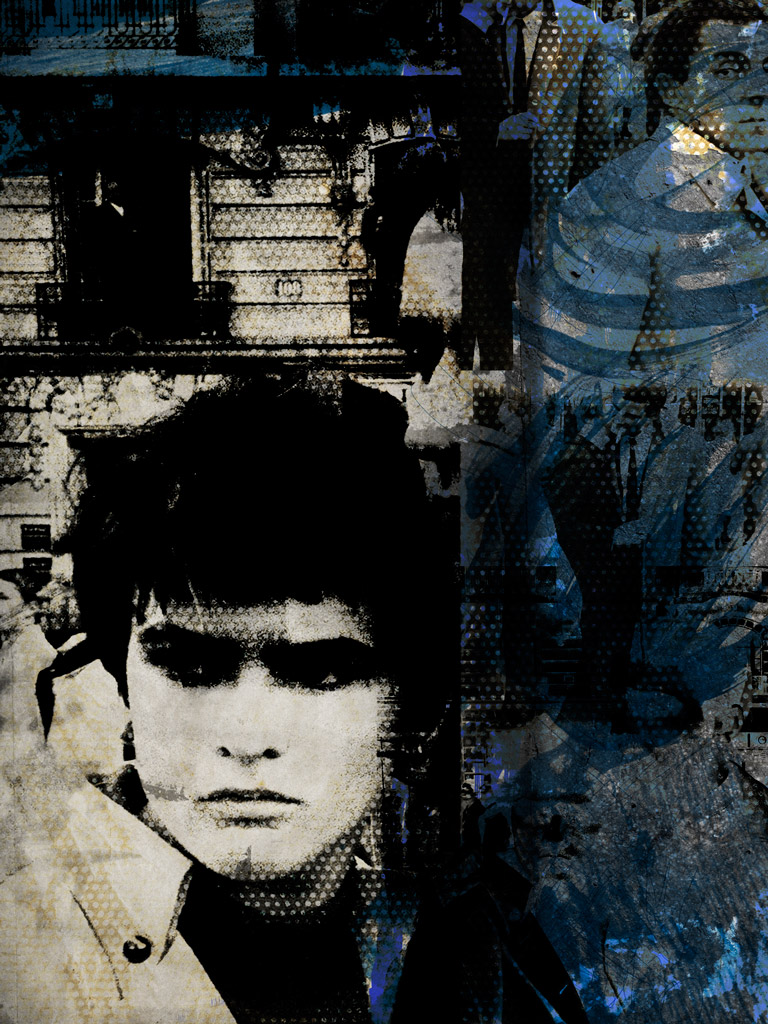

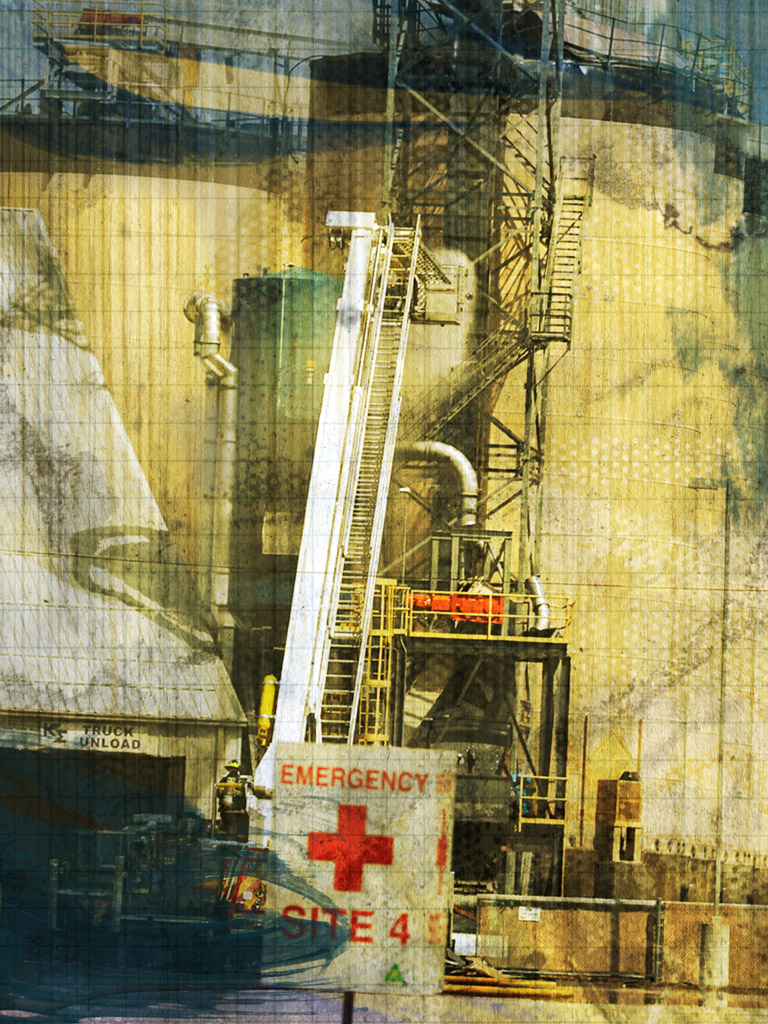

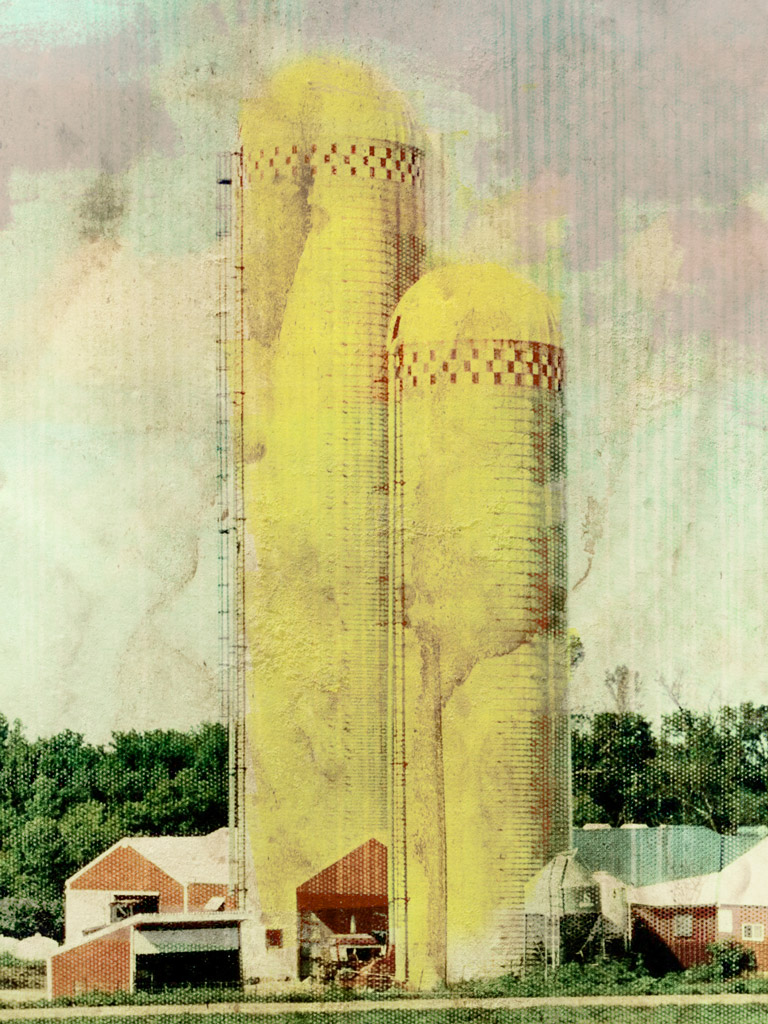

My latest project, called Binary Code, attempts to give visual expression to a world where databases and algorithms determine the ultimate reality, including nature. This is essentially the end of the order of nature as we know it.

And for some reason I can’t explain, the whole series consists of images of women and industrial silos. It could be because my files are full of these images which I have always found fascinating although I could also be trying to justify it as the end of a fundamental symbol where the woman and uterus are no longer relevant symbols for representing fertility, reproduction, beauty or nature.

I would like to comment on an aspect that is important for me. The criteria on the basis of which the artist selects an “appropriate” object may vary but the relationship between artist and subject is never univocal. The artist is only one of the parts. The object rebels and fights for its real nature, reacting to manipulation and boycotting it. The sign-object maintains some of its original nature, however much it fights against it. I think this negotiation between idea and reality is what makes appropriation so interesting.

ZZ. How does having sources with such diverse origins affect the narrative and timing of your images?

M. Nothing has different origins. Our only access to reality is mathematics, and quantum physics has eliminated time as an explanatory element for the behavior of elementary particles. Stripping photography of narrative and temporality is a lofty and necessary goal.

Narrative and temporality can be analyzed from many perspectives. For example, for Cyborg art, time is irrelevant because it can accumulate and eliminate modifications from its code indefinitely, meaning that there is no original or copy. Another less visionary example would be the way we experience the Internet today, jumping from one hyperlink to another, breaking up the original narrative structure of a text. Narrative as a mechanism and source of truth only continues to operate in Hollywood.

But it is a complex topic, because with narrative and temporality, what we are talking about is the issue of meaning. Refuting narrative entails resisting a set meaning that permits redemption (here I am referring to Adorno’s famous essay on Beckett). Eluding narrative prevents access to the comfortable world of history and fable.

In Binary Code there is no narrative. There are simply visual objects seeking to reclaim their meaning in their material specificity. Binary code, from its maximum abstraction, creates objects whose significance is drawn from its materiality rather than the code. The disenchantment of modern nature, its non-meaning, does not prevent nature from speaking through our bodies, desires, suffering and needs. By reclaiming the object, this project calls for a return to aesthetic materialism (albeit in an updated form).

If you think about it for a moment, it may also be time to reclaim the Aztec god Ometeotl as a contemporary symbol. Ometeotl, the immanent, invisible and immaterial god who had no temple, is the creator of all dualities (and therefore predates them): time and space, male and female, day and night, matter and spirit, zero and one. He is the creator of everything. Ometeotl is the binary code.

Max de Esteban (Spain). A fine-art photographer. Holds a Graduate degree from UPC, a Master from Stanford University and a PhD from URL. He is a Fulbright Alumni. His work is organized in two distinct bodies: Elegies of Manumission and Propositions. Awards: the 2010 National Award of Professional Photography (Spain)- Gold LUX.[2] and Grand Prix Jury's Special Award, Fotofestiwal 2010, Poland.

Max de Esteban (Spain). A fine-art photographer. Holds a Graduate degree from UPC, a Master from Stanford University and a PhD from URL. He is a Fulbright Alumni. His work is organized in two distinct bodies: Elegies of Manumission and Propositions. Awards: the 2010 National Award of Professional Photography (Spain)- Gold LUX.[2] and Grand Prix Jury's Special Award, Fotofestiwal 2010, Poland.

ZZ. What led you to appropriation and remix and how are they significant in your work?

M. Appropriation and remix have a long artistic tradition, beginning with Picasso’s collages. As early as the 1920s, Hannah Hoch and the Dadaists used this mode of expression to create major photographic works. In music, for example, from today’s DJs and Pop to Glenn Gould and Miles Davis, the practice of remix, collage and appropriation has been an essential part of their production. What I mean is that as an artistic concept, appropriation and remix are pretty standard and not particularly groundbreaking.

The interesting question is why their aesthetic power has been reasserted in photography precisely now. And I think one possible answer would be the combination of the formal exhaustion of the linear perspective as a photographic representation of the world and the huge impact digitization is having on every aspect of our lives. I would answer your question by turning it around and saying I find it hard to think of a truly relevant form of photography for the world we live in that continues to respect the Eurocentric, reactionary structure of the dark room.

ZZ. What do you mean by Eurocentric and reactionary?

M. The linear perspective, the visual structure resulting from the dark room, is a very particular and ideological way of visualizing the world. Panofsky has a text about it he wrote in 1927, a real classic, that is a pleasure to read.

But what is really remarkable is that it is an exception in art history. In 10,000 years of history, the linear perspective spans only 500 years and is located exclusively in the West. It has never been of interest to Asian, or pre-Columbian or African art ... it is a European way of seeing in a period beginning in the Renaissance and ending in the 19th century.

And this is no coincidence because its ideological content is well known. The linear perspective arranges the world from the point of view of an autonomous individual whose individuality is the world’s principle of meaning. It is pure Descartes. And we all remember Descartes’ Fifth Meditation, which states that since the essence of matter is its extension, geometry is an essential instrument for understanding nature. Modernity can be defined as the advance of abstraction and the prevalence of the quantitative over the qualitative in which the mathematical-scientific order is regarded as the only source of valid knowledge. There is so much contemporary thought that debunks this narrative that I won't repeat it here.

Thus, surprisingly, my earlier comment is still valid. Why should digital photography continue giving priority to a functionally and ideologically devalued visual structure?

ZZ. Why do you think digital photography changes the way we understand appropriation and remix?

M. Digital technologies are leading us towards the radical transformation of our world. By replacing the industrial economy with a bio-cybernetic system, digitization is modifying our environment, our subjectivity and soon, our bodies. This is the technological phenomenon that will define our era and therefore our culture.

Unlike an analog file, a digital file is invisible. It is a code whose visual expression is a translation highly mediated by default algorithms, whose most prominent feature is precisely its immateriality.

This technical structure fits our current era of abstraction and non-referentiality and the digital financialization of the economy. How do we see the world today? We have the answer on our computer and Smartphone screens. What is the essential aspect of the financial economy? The recombination of existing information units to create new information, in other words, “constructive compositing”. Digitization has definitively invalidated linear narrative, the monocular perspective and the author’s “authority”.

ZZ. You attach a great deal of importance to the concept of technology in your work. Could you explain why?

M. We are moving towards a world as a “technological whole”. Technical manipulation has already invaded our bodies, the last frontier, and no-one doubts that having machines inside our bodies will soon become commonplace.

The cyborg raises more complex issues for our species, which, though somewhat deteriorated, continues to maintain the autonomy of the subject as an essential value. Abstraction, digitization and cyborg are three sides of the same coin that heralds our new world, whether we like it or not. In my opinion, reflecting on technology is necessary, urgent and politically essential.

ZZ. And how do you think technology affects the practice of photography?

M. I’d like to point something out. One of the problems of photography is the confusion between technology and use. Writing is a communication technology that serve to draw up a commercial contract and compose a poem by Virgil. It is the same technology but nobody would ever mistake Virgil for a notary. In photography, we tend to combine uses, which creates enormous confusion in critical discourse. Throughout this interview, I have been referring to the use of photography as a means of artistic expression.

The thing is that photography has always been halfway to a cyborg. It is a machine that affects and to some extent determines human power, thought and expression and is therefore an ideal place for reflecting on the issues I mentioned earlier.

To give you an example: How can you visually depict the abstraction of the economy when the material references of wealth have been replaced by a binary code? That’s what I’m doing at the moment and it forces me to rethink what “representation” means in this new visual regime.

Another example: How does the idea of the cyborg affect art categories? That’s the topic I try to get my teeth into in the text “Cyborg Art: art in the bio-cybernetic era”. And there are a thousand other possible ideas that make photography an exciting medium at this particular historical time. The point is that if photographic practice does not take up the challenge raised by contemporaneity, it will be relegated to banality and antique shops.

ZZ. How do you choose the sources you use and what significance do they have for your series?

M. Like nearly everything in life, it is a combination of determination and chance. In my case, too much planning and/or reflection in my work paralyzes me while dreams or rather daydreams are of paramount importance.

My latest project, called Binary Code, attempts to give visual expression to a world where databases and algorithms determine the ultimate reality, including nature. This is essentially the end of the order of nature as we know it.

And for some reason I can’t explain, the whole series consists of images of women and industrial silos. It could be because my files are full of these images which I have always found fascinating although I could also be trying to justify it as the end of a fundamental symbol where the woman and uterus are no longer relevant symbols for representing fertility, reproduction, beauty or nature.

I would like to comment on an aspect that is important for me. The criteria on the basis of which the artist selects an “appropriate” object may vary but the relationship between artist and subject is never univocal. The artist is only one of the parts. The object rebels and fights for its real nature, reacting to manipulation and boycotting it. The sign-object maintains some of its original nature, however much it fights against it. I think this negotiation between idea and reality is what makes appropriation so interesting.

ZZ. How does having sources with such diverse origins affect the narrative and timing of your images?

M. Nothing has different origins. Our only access to reality is mathematics, and quantum physics has eliminated time as an explanatory element for the behavior of elementary particles. Stripping photography of narrative and temporality is a lofty and necessary goal.

Narrative and temporality can be analyzed from many perspectives. For example, for Cyborg art, time is irrelevant because it can accumulate and eliminate modifications from its code indefinitely, meaning that there is no original or copy. Another less visionary example would be the way we experience the Internet today, jumping from one hyperlink to another, breaking up the original narrative structure of a text. Narrative as a mechanism and source of truth only continues to operate in Hollywood.

But it is a complex topic, because with narrative and temporality, what we are talking about is the issue of meaning. Refuting narrative entails resisting a set meaning that permits redemption (here I am referring to Adorno’s famous essay on Beckett). Eluding narrative prevents access to the comfortable world of history and fable.

In Binary Code there is no narrative. There are simply visual objects seeking to reclaim their meaning in their material specificity. Binary code, from its maximum abstraction, creates objects whose significance is drawn from its materiality rather than the code. The disenchantment of modern nature, its non-meaning, does not prevent nature from speaking through our bodies, desires, suffering and needs. By reclaiming the object, this project calls for a return to aesthetic materialism (albeit in an updated form).

If you think about it for a moment, it may also be time to reclaim the Aztec god Ometeotl as a contemporary symbol. Ometeotl, the immanent, invisible and immaterial god who had no temple, is the creator of all dualities (and therefore predates them): time and space, male and female, day and night, matter and spirit, zero and one. He is the creator of everything. Ometeotl is the binary code.

Max de Esteban (Spain). A fine-art photographer. Holds a Graduate degree from UPC, a Master from Stanford University and a PhD from URL. He is a Fulbright Alumni. His work is organized in two distinct bodies: Elegies of Manumission and Propositions. Awards: the 2010 National Award of Professional Photography (Spain)- Gold LUX.[2] and Grand Prix Jury's Special Award, Fotofestiwal 2010, Poland.

Max de Esteban (Spain). A fine-art photographer. Holds a Graduate degree from UPC, a Master from Stanford University and a PhD from URL. He is a Fulbright Alumni. His work is organized in two distinct bodies: Elegies of Manumission and Propositions. Awards: the 2010 National Award of Professional Photography (Spain)- Gold LUX.[2] and Grand Prix Jury's Special Award, Fotofestiwal 2010, Poland.Ellie Ivanova

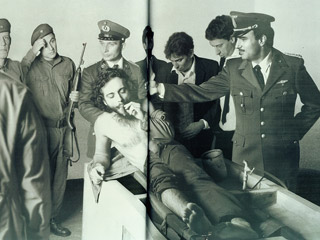

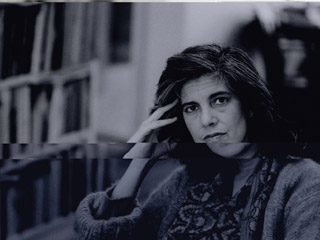

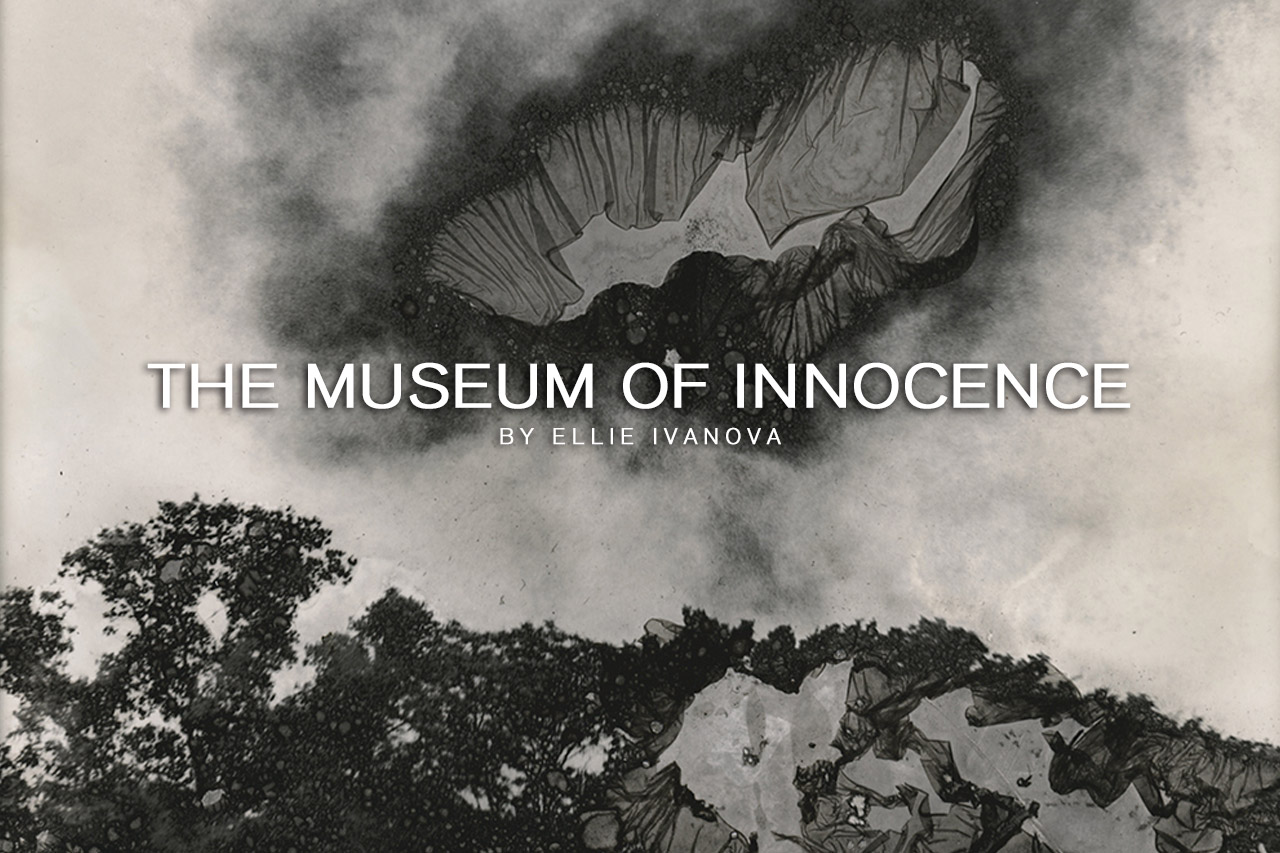

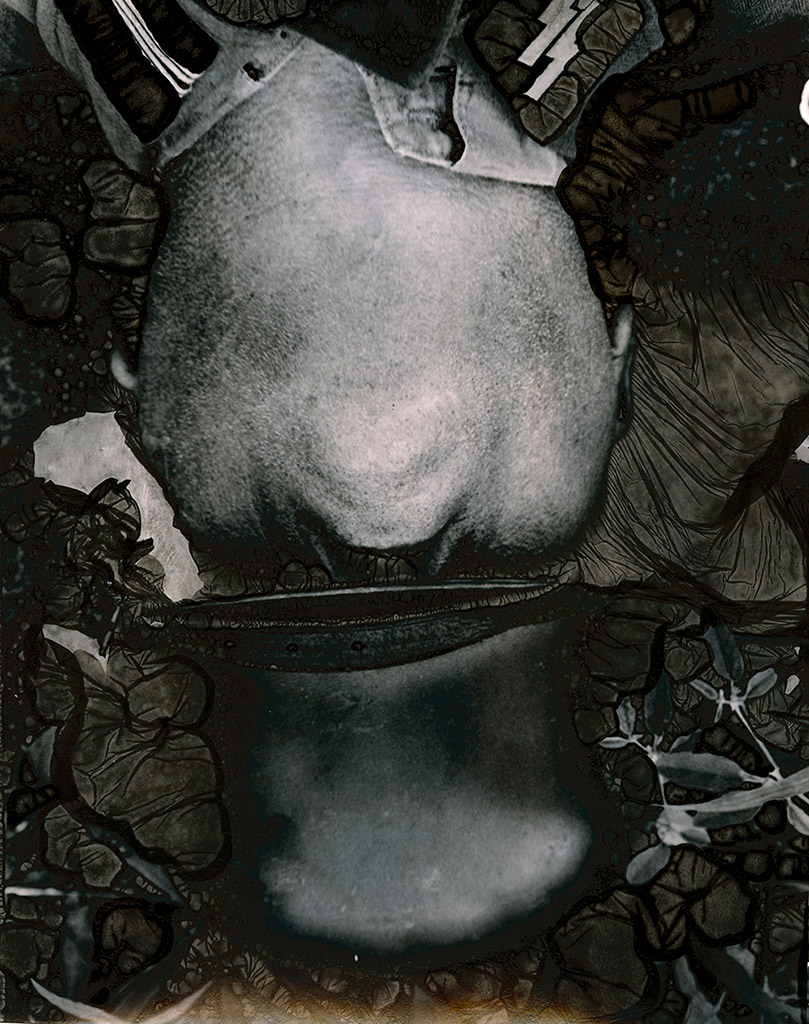

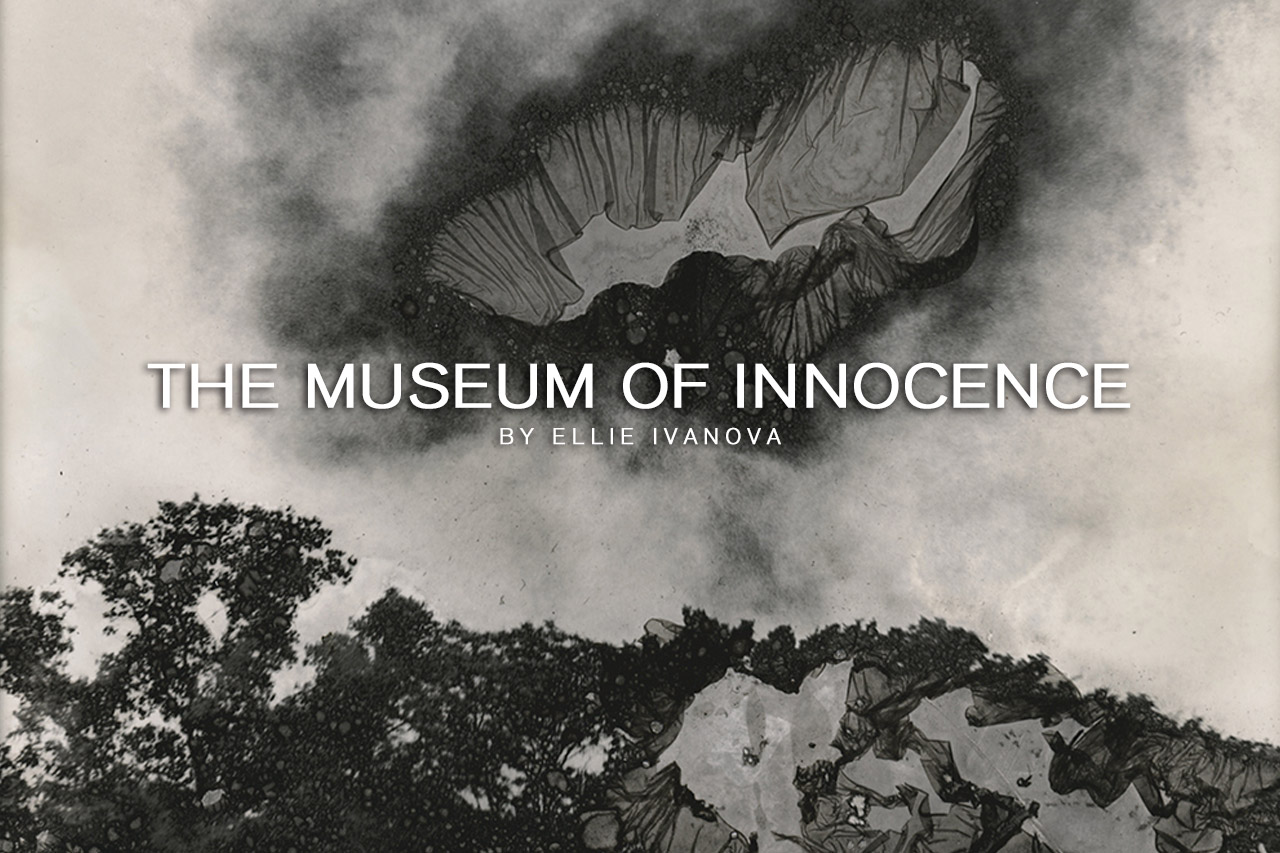

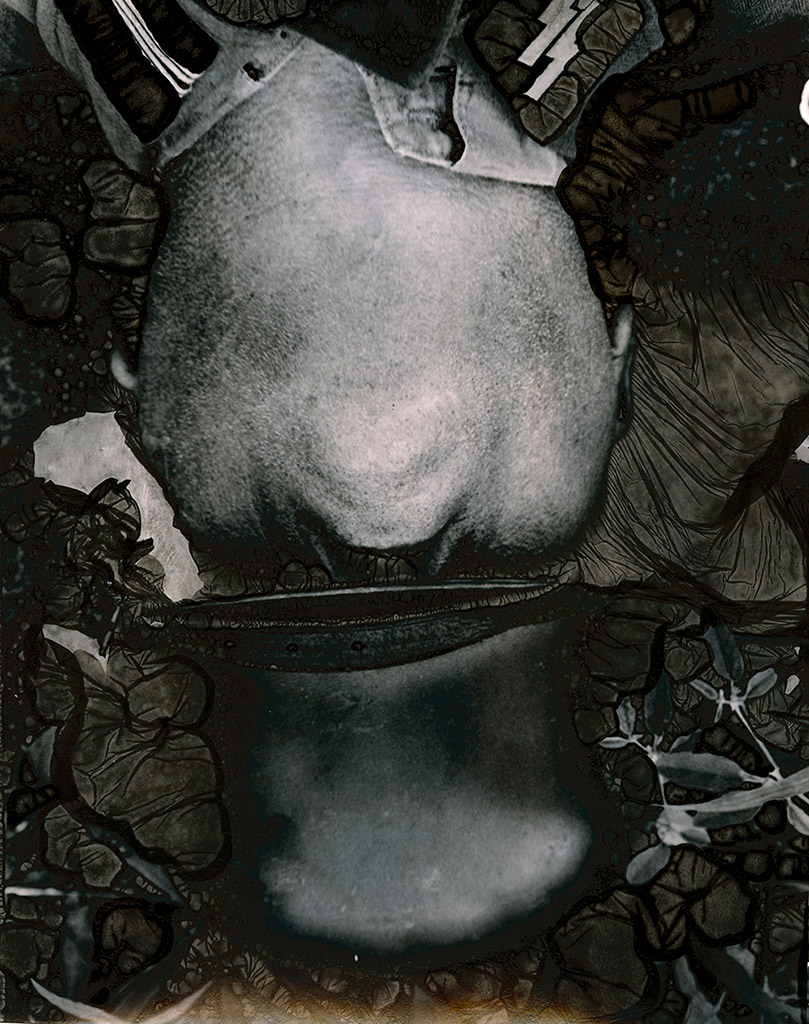

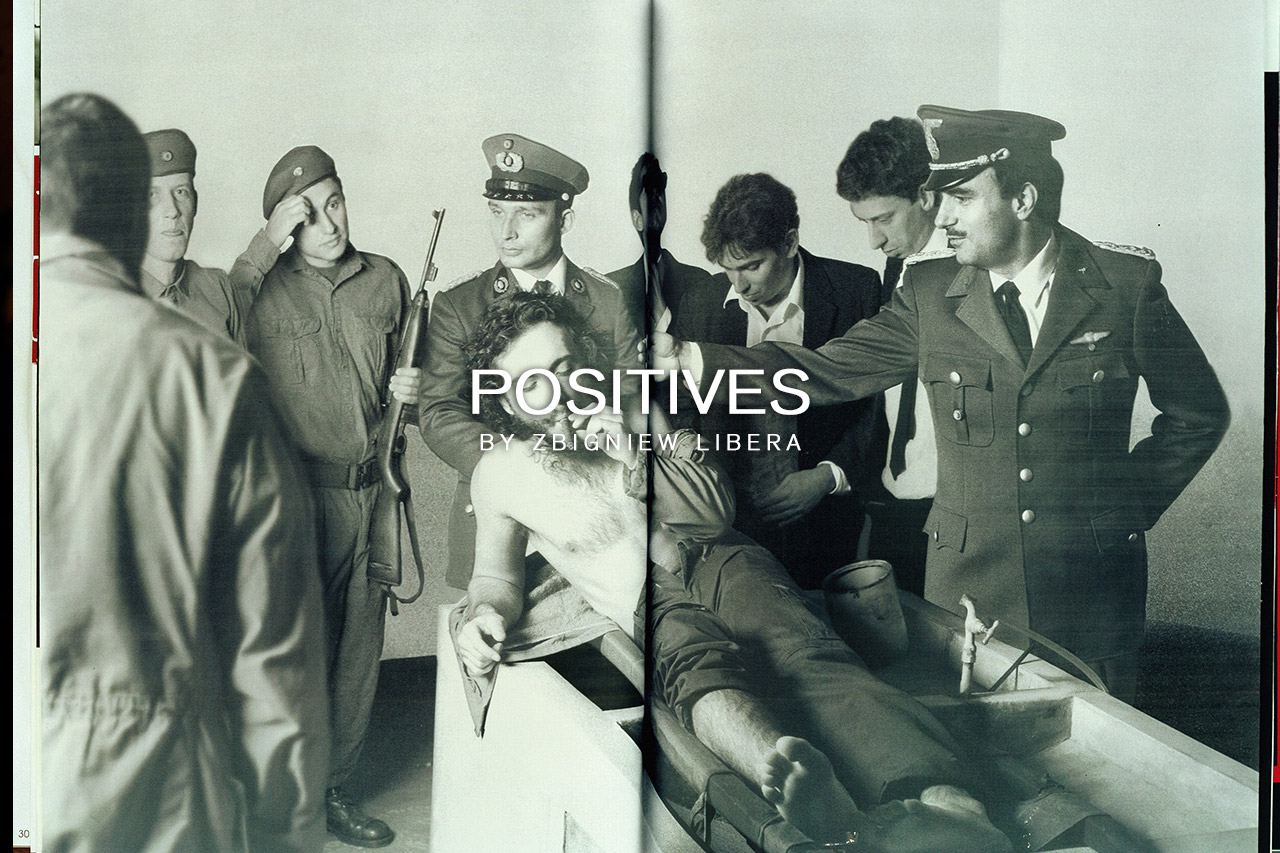

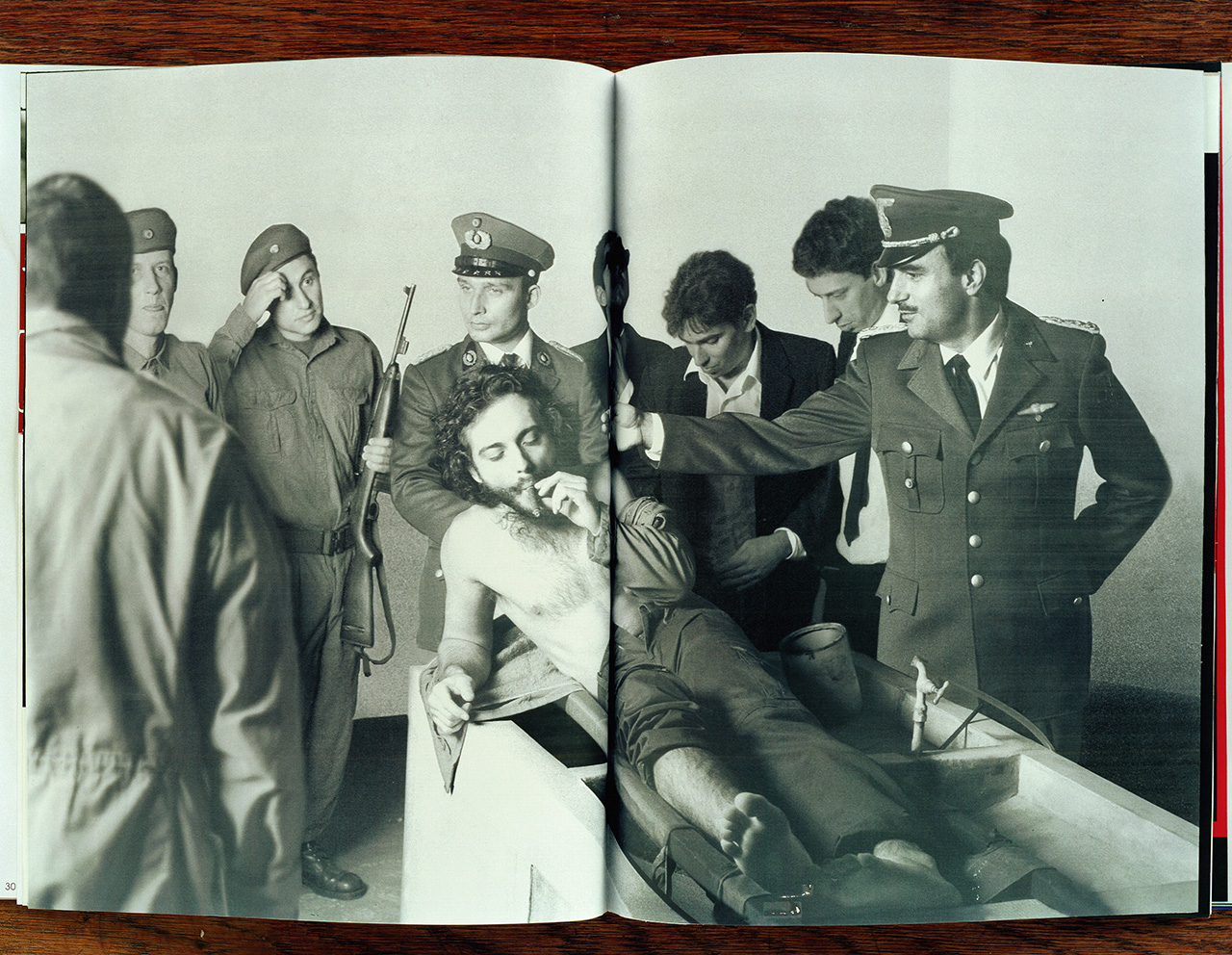

As a photographic artist, I am interested in the fraught relationship between photography and memory that creates a new reality in the gradual process of shifting and distortion. This project explores how memory appropriates history through photography and how it changes our perceptions of the past.

I document World War II reenactments in Texas. This war, which has become part of the foundational myth of the contemporary United States, has remained one of the few unquestioned sources of national identity, justice and masculinity today. Yet even though considered “the good war” that doesn’t need to be embellished in the public consciousness, the past is being constantly reinterpreted and changed through the reenactment movement. Photography plays a significant role in this process as participants recreate historic photographs in their roleplay and then use newly taken pictures of themselves to present their made-up historic persona. This distortion of recreating and personification of history is then reflected in the acid-bath mordancage process through its degradation, toxicity, unpredictability, physicality and surreal final result.

As a process, this project goes against the grain of what photography is. I use it as an ideological reaction to the noncommittal pull of digital culture. Instead of fixing the moment forever, it erases the image and alters the emulsion. Instead of endless multiples, it produces unique, unrepeatable prints. Instead of an objective optic capture, it is a physical object that shows the hand of the artist in its tactile recreation. It is toxic, unpredictable and shifts over time. Just like memory, it reflects the constant battle between preservation and ephemerality.

>

>

Ellie Ivanova (Bulgaria). She holds an MFA in Photography from the University of North Texas. With a background in literature, her photographic interest is the experience of memory and the self-fashioning of identity, in both traditional and experimental formats. She uses processes and conceptual approaches through which images continue to evolve after they have been captured and printed, blurring the edges between the factual and the fictitious. Her photographs have been exhibited throughout the United States in commercial, non-profit and university galleries and are part of the permanent collections of Human Rights Art at South Texas College and Fort Wayne Museum of Art, among others.

Ellie Ivanova (Bulgaria). She holds an MFA in Photography from the University of North Texas. With a background in literature, her photographic interest is the experience of memory and the self-fashioning of identity, in both traditional and experimental formats. She uses processes and conceptual approaches through which images continue to evolve after they have been captured and printed, blurring the edges between the factual and the fictitious. Her photographs have been exhibited throughout the United States in commercial, non-profit and university galleries and are part of the permanent collections of Human Rights Art at South Texas College and Fort Wayne Museum of Art, among others.

As a photographic artist, I am interested in the fraught relationship between photography and memory that creates a new reality in the gradual process of shifting and distortion. This project explores how memory appropriates history through photography and how it changes our perceptions of the past.

I document World War II reenactments in Texas. This war, which has become part of the foundational myth of the contemporary United States, has remained one of the few unquestioned sources of national identity, justice and masculinity today. Yet even though considered “the good war” that doesn’t need to be embellished in the public consciousness, the past is being constantly reinterpreted and changed through the reenactment movement. Photography plays a significant role in this process as participants recreate historic photographs in their roleplay and then use newly taken pictures of themselves to present their made-up historic persona. This distortion of recreating and personification of history is then reflected in the acid-bath mordancage process through its degradation, toxicity, unpredictability, physicality and surreal final result.

As a process, this project goes against the grain of what photography is. I use it as an ideological reaction to the noncommittal pull of digital culture. Instead of fixing the moment forever, it erases the image and alters the emulsion. Instead of endless multiples, it produces unique, unrepeatable prints. Instead of an objective optic capture, it is a physical object that shows the hand of the artist in its tactile recreation. It is toxic, unpredictable and shifts over time. Just like memory, it reflects the constant battle between preservation and ephemerality.

>

>

Ellie Ivanova (Bulgaria). She holds an MFA in Photography from the University of North Texas. With a background in literature, her photographic interest is the experience of memory and the self-fashioning of identity, in both traditional and experimental formats. She uses processes and conceptual approaches through which images continue to evolve after they have been captured and printed, blurring the edges between the factual and the fictitious. Her photographs have been exhibited throughout the United States in commercial, non-profit and university galleries and are part of the permanent collections of Human Rights Art at South Texas College and Fort Wayne Museum of Art, among others.

Ellie Ivanova (Bulgaria). She holds an MFA in Photography from the University of North Texas. With a background in literature, her photographic interest is the experience of memory and the self-fashioning of identity, in both traditional and experimental formats. She uses processes and conceptual approaches through which images continue to evolve after they have been captured and printed, blurring the edges between the factual and the fictitious. Her photographs have been exhibited throughout the United States in commercial, non-profit and university galleries and are part of the permanent collections of Human Rights Art at South Texas College and Fort Wayne Museum of Art, among others.Barbara Ciurej & Lindsay Lochman

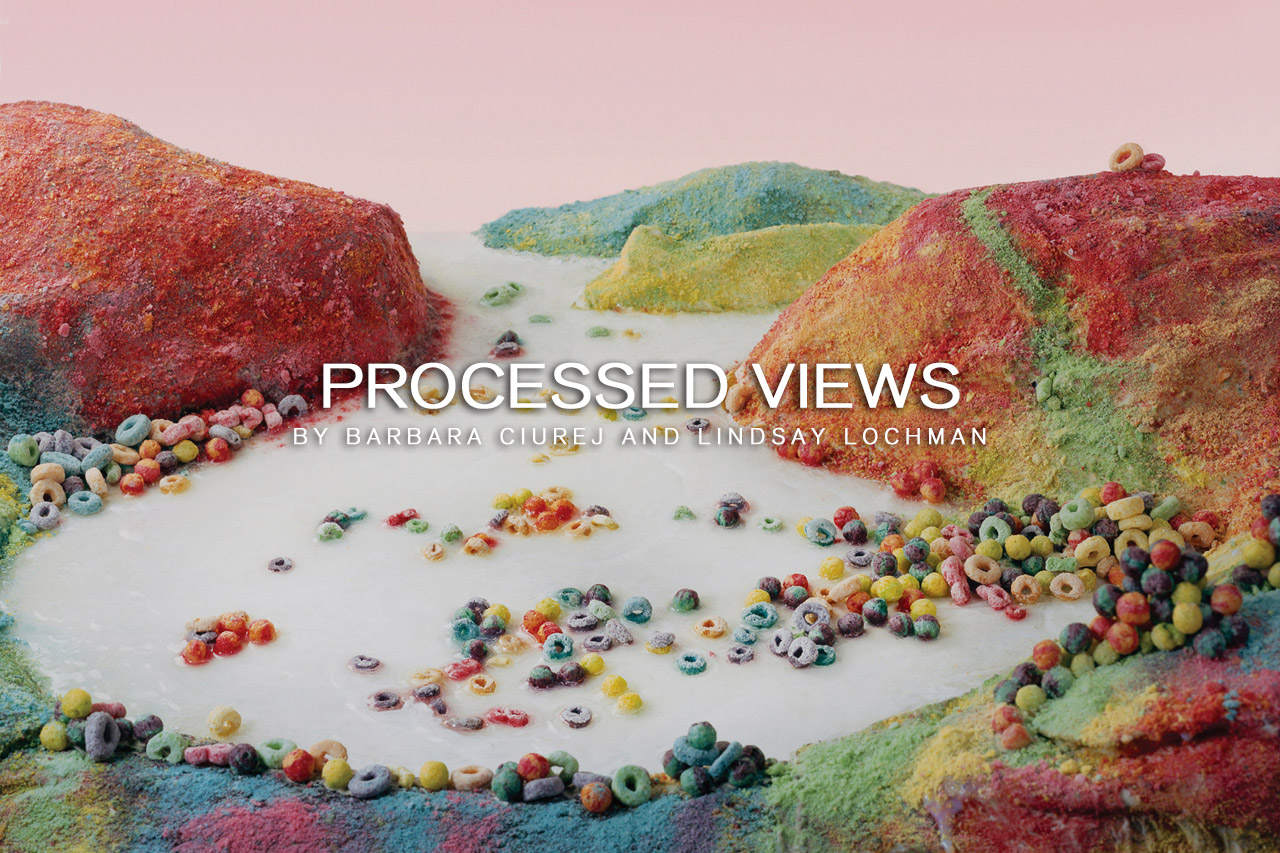

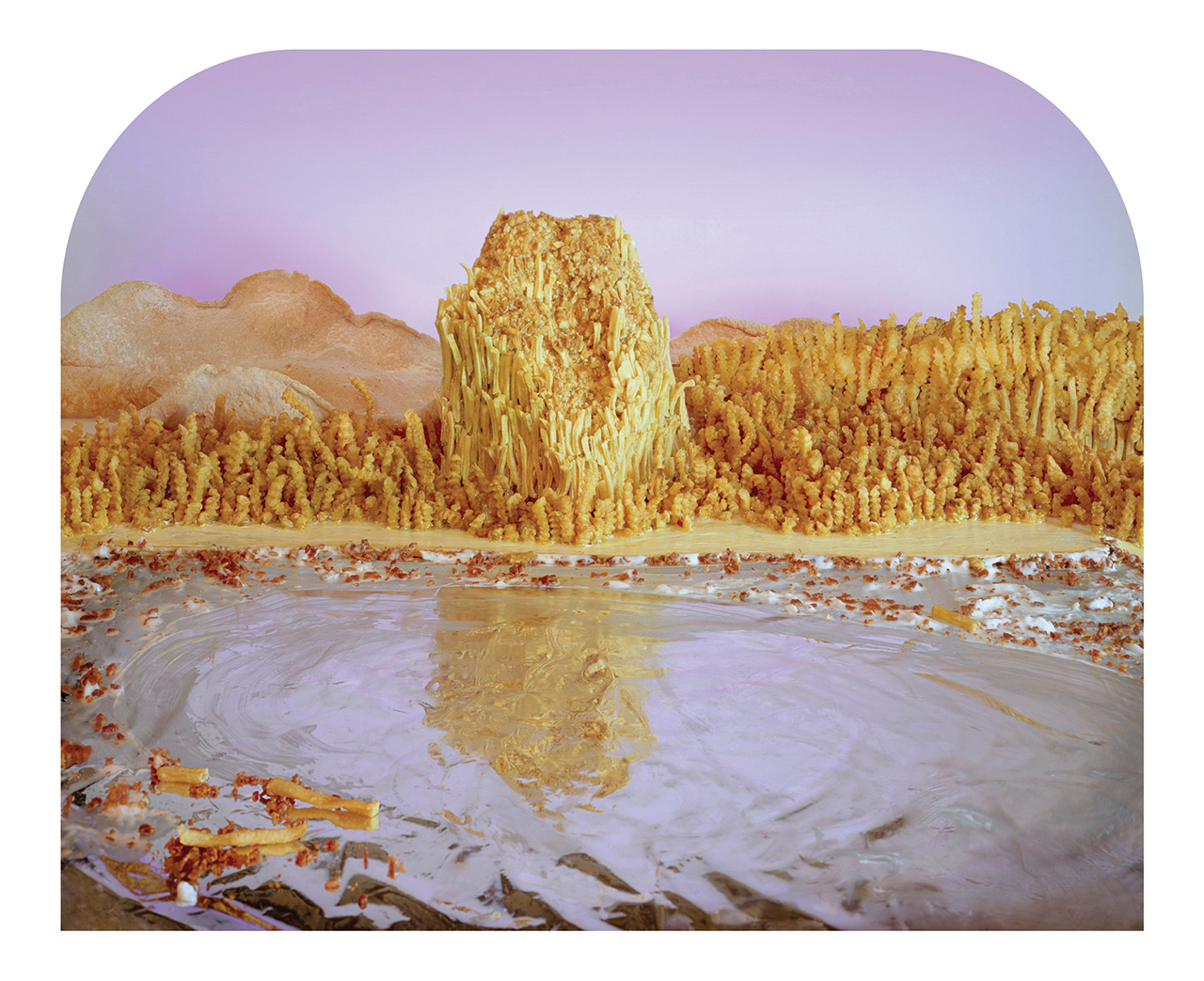

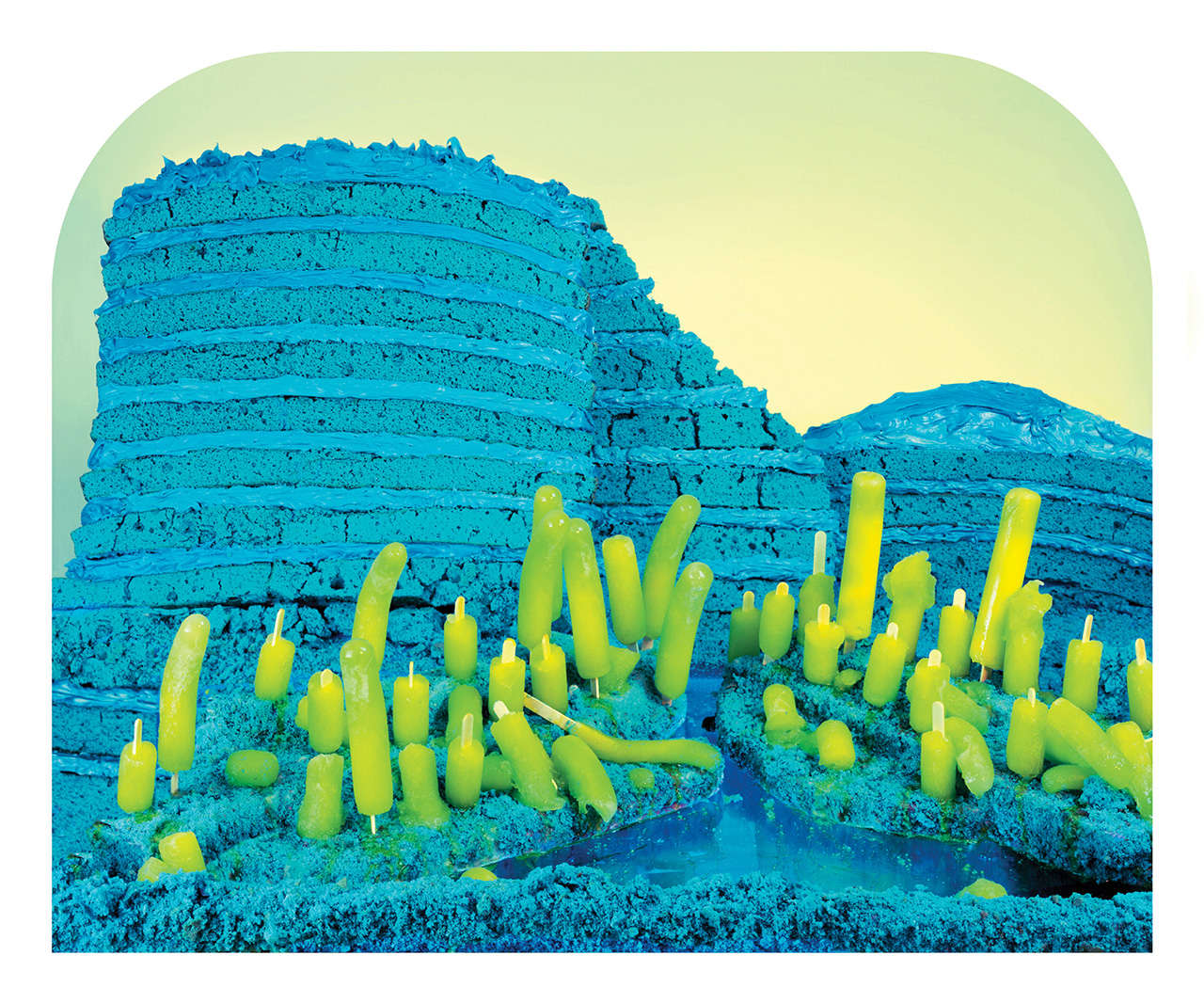

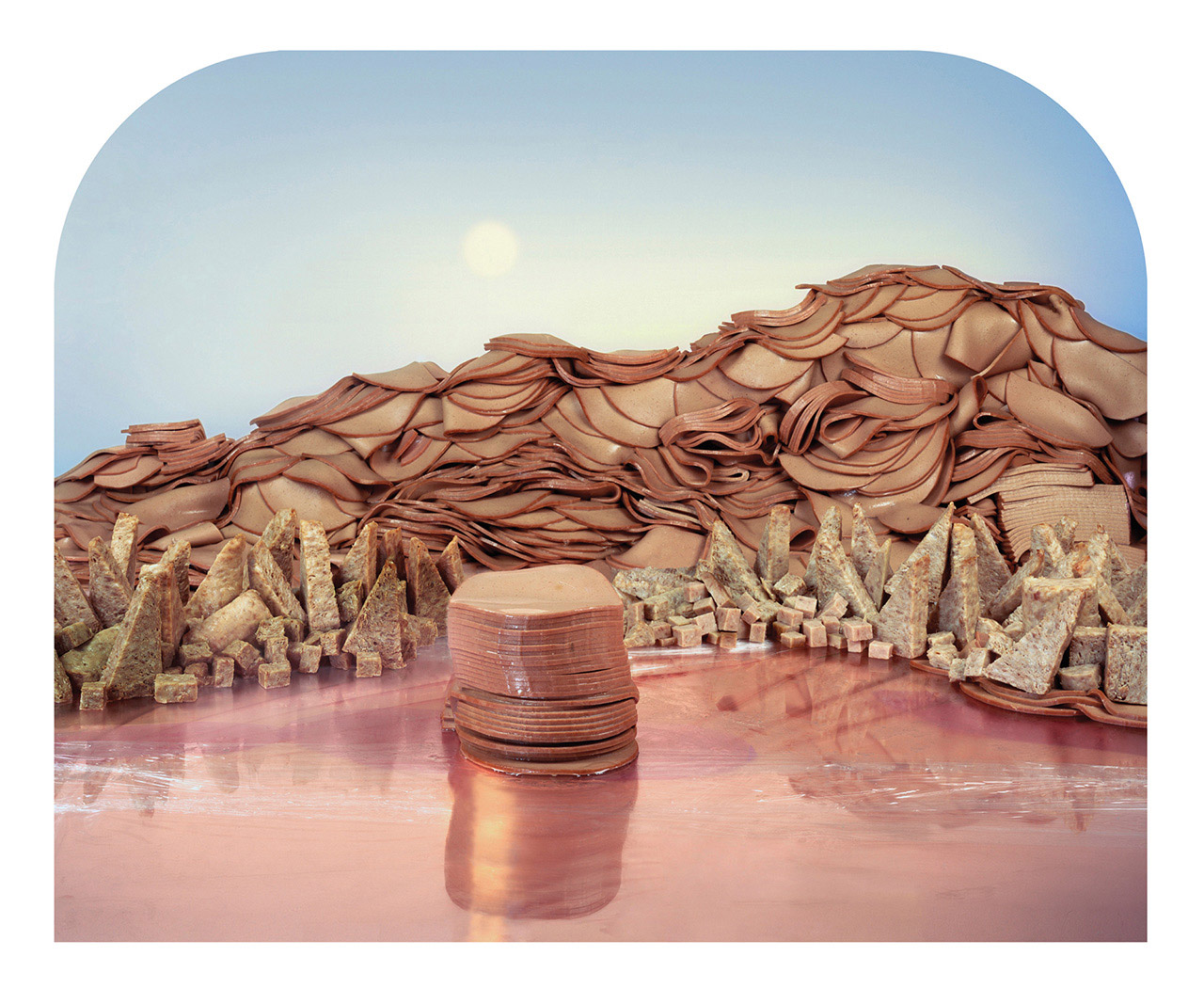

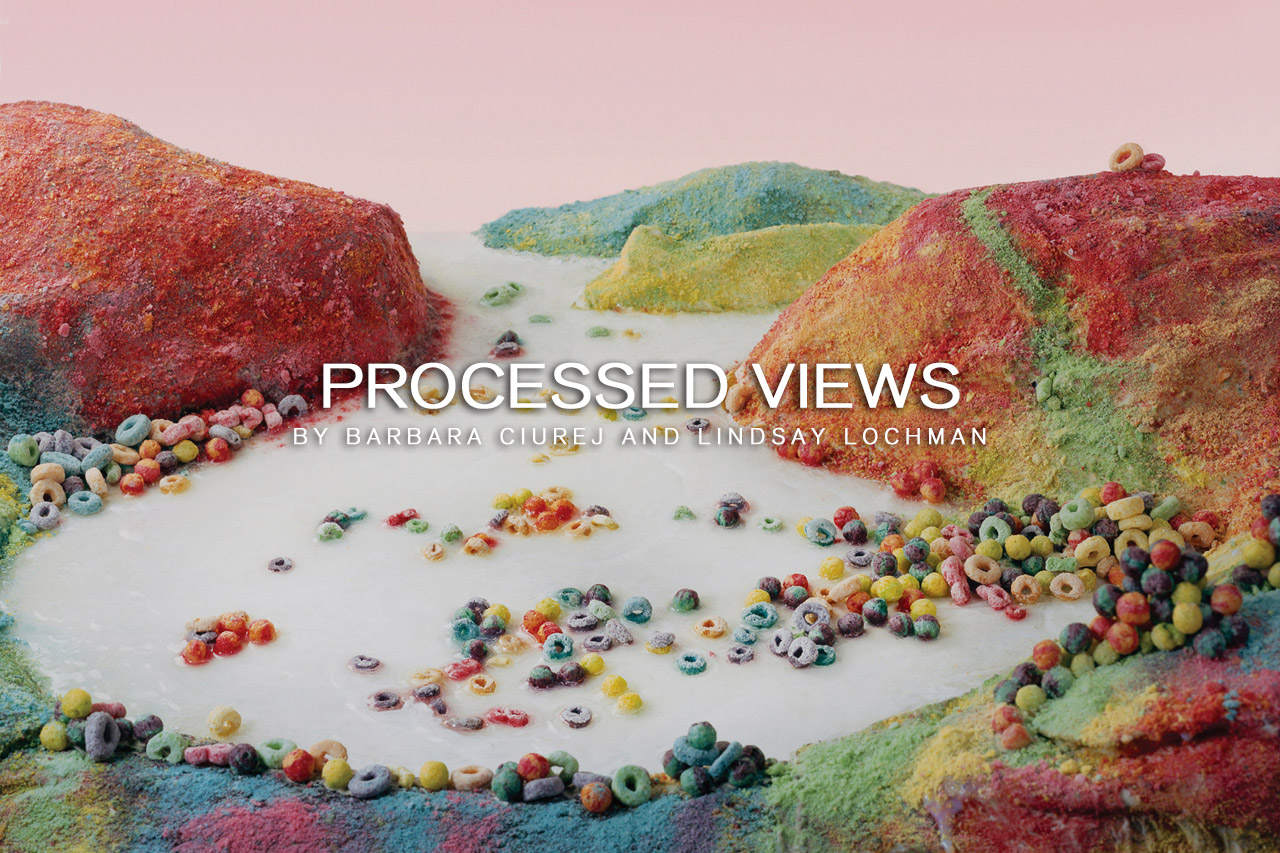

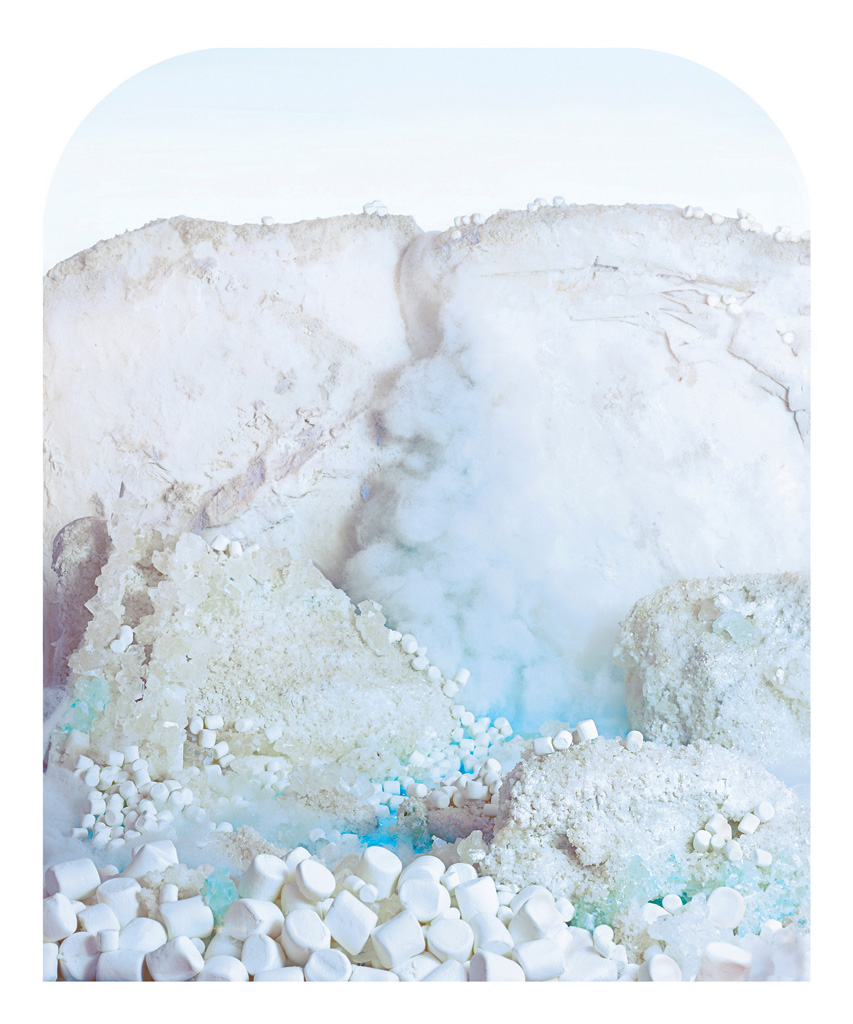

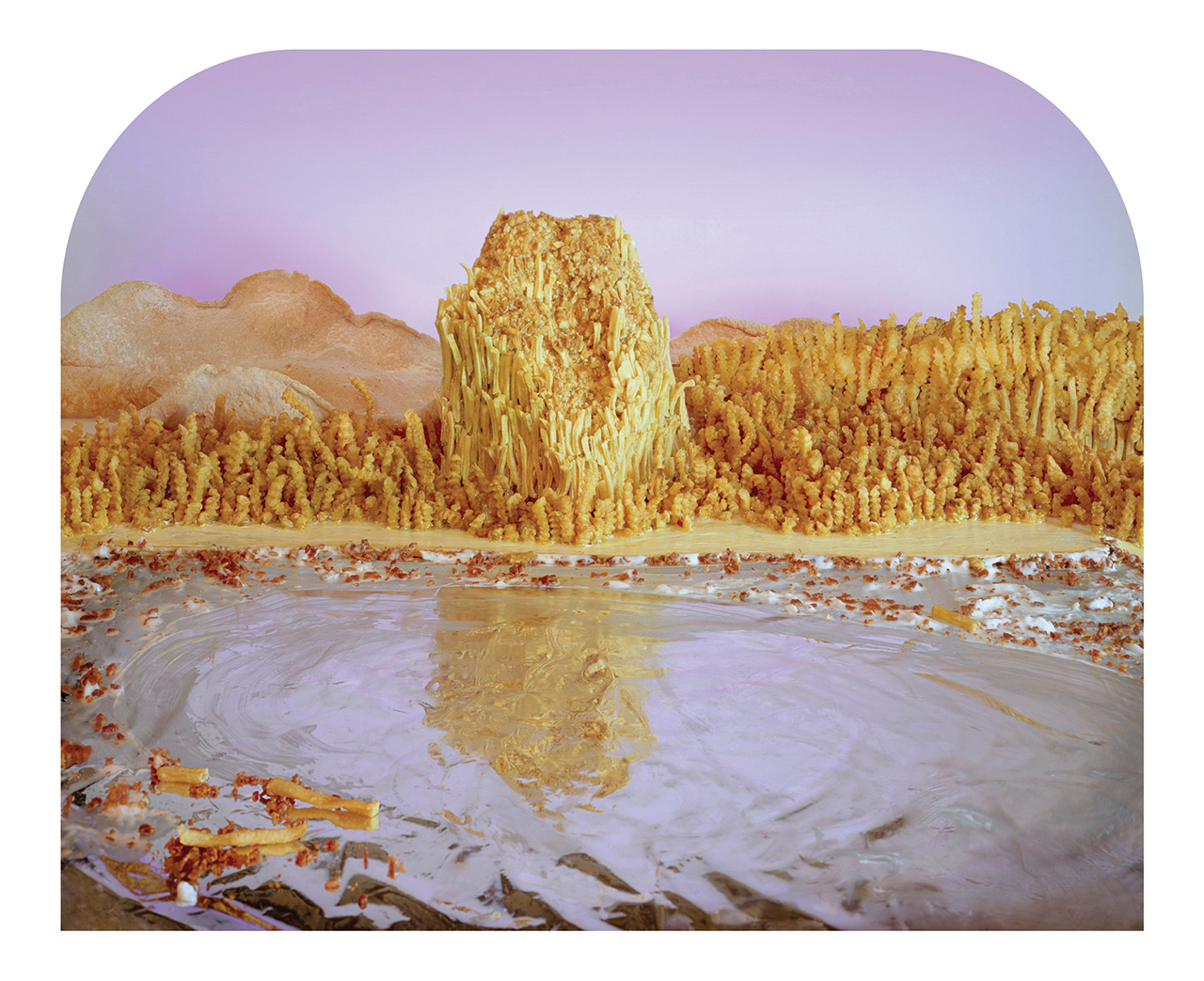

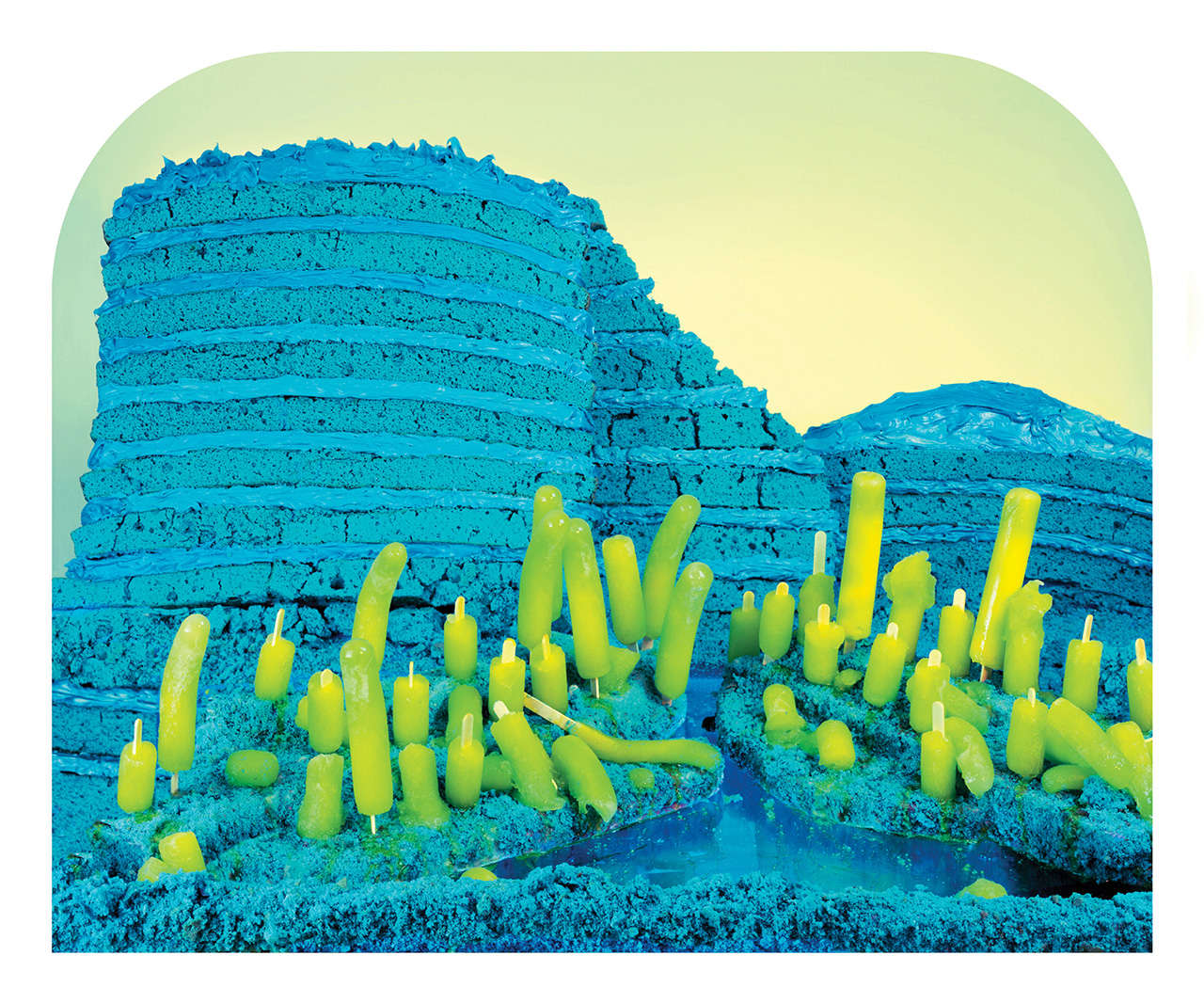

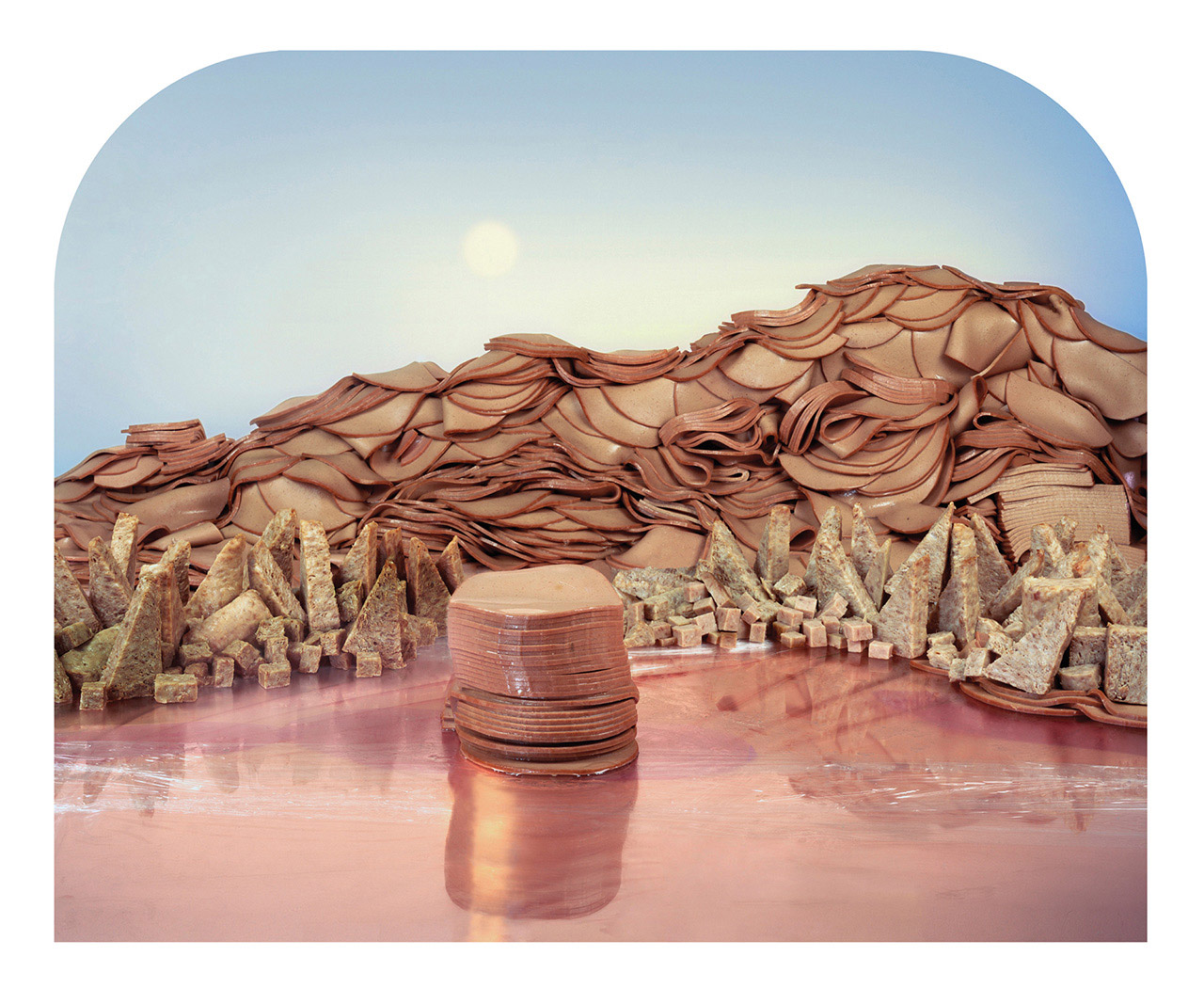

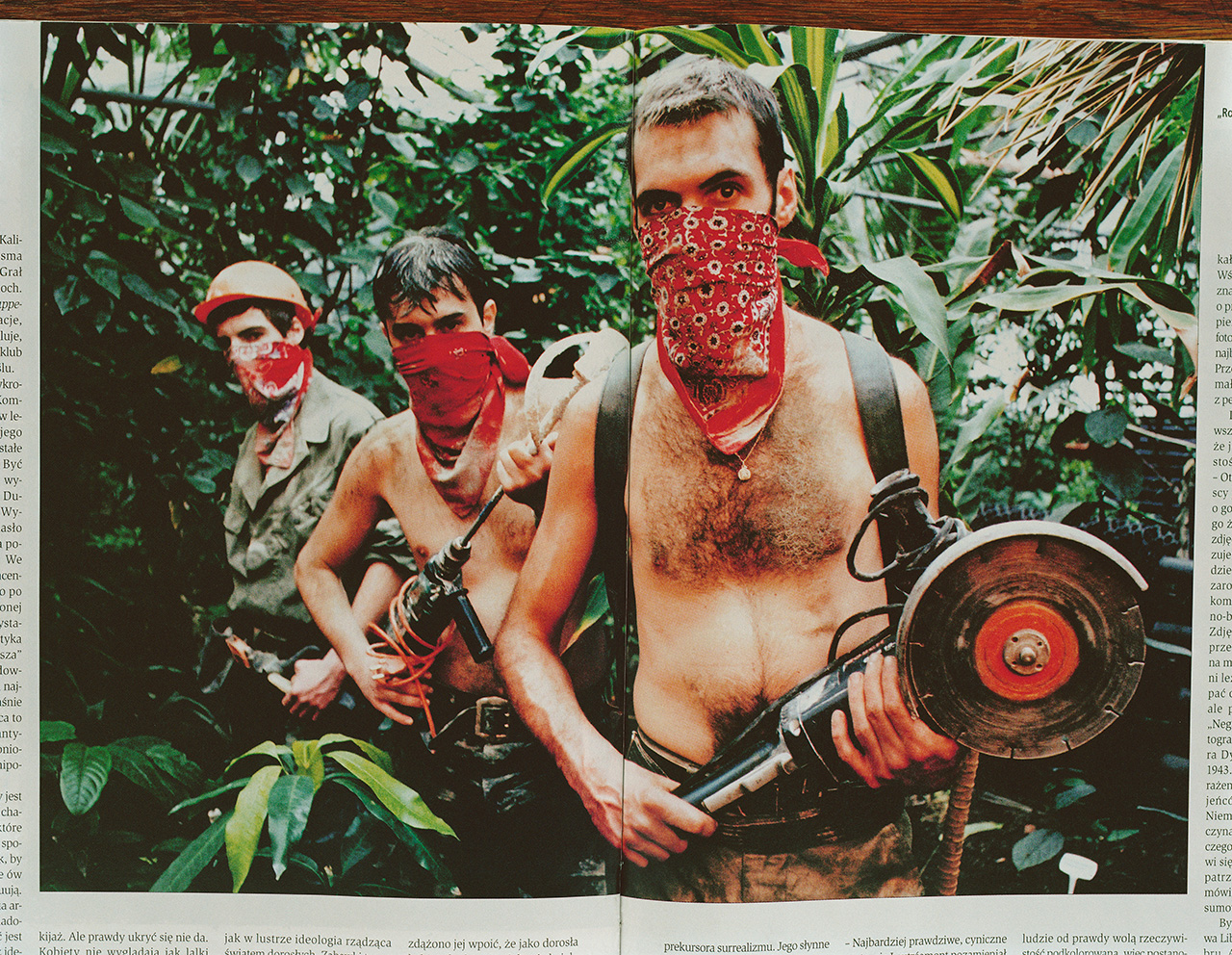

Processed Views interprets the frontier of industrial food production: the seductive and alarming intersection of nature and technology. As we move further away from the sources of our food, we head into uncharted territory replete with unintended consequences for the environment and for our health.

In our commentary on the landscape of processed foods, we reference the work of photographer, Carleton Watkins (1829-1916). His sublime views framed the American West as a land of endless possibilities and significantly influenced the creation of the first national parks. However, many of Watkins’ photographs were commissioned by the corporate interests of the day; the railroad, mining, lumber and milling companies. His commissions served as both documentation of and advertisement for the American West. Watkins’ views expessed the popular 19th century notion of Manifest Destiny – America’s bountiful land, inevitably and justifiably utilized by its citizens.

We built these views to examine consumption, progress and the changing landscape.

Barbara Ciurej & Lindsay Lochman (USA). Collaborate on photographic projects that address the confluence of history, myth and popular culture. Their work has been exhibited widely and their photographs are in public and private collections including the Art Institute of Chicago, Walker Art Center, Museum of Contemporary Photography, Milwaukee Art Museum, and the Beinecke Library at Yale University. They are currently exploring the potential of constructed landscapes to describe social inequality. Processed Views is currently on view at Rick Wester Fine Art ,New York, until July 29, 2016.

Barbara Ciurej & Lindsay Lochman (USA). Collaborate on photographic projects that address the confluence of history, myth and popular culture. Their work has been exhibited widely and their photographs are in public and private collections including the Art Institute of Chicago, Walker Art Center, Museum of Contemporary Photography, Milwaukee Art Museum, and the Beinecke Library at Yale University. They are currently exploring the potential of constructed landscapes to describe social inequality. Processed Views is currently on view at Rick Wester Fine Art ,New York, until July 29, 2016.

Processed Views interprets the frontier of industrial food production: the seductive and alarming intersection of nature and technology. As we move further away from the sources of our food, we head into uncharted territory replete with unintended consequences for the environment and for our health.

In our commentary on the landscape of processed foods, we reference the work of photographer, Carleton Watkins (1829-1916). His sublime views framed the American West as a land of endless possibilities and significantly influenced the creation of the first national parks. However, many of Watkins’ photographs were commissioned by the corporate interests of the day; the railroad, mining, lumber and milling companies. His commissions served as both documentation of and advertisement for the American West. Watkins’ views expessed the popular 19th century notion of Manifest Destiny – America’s bountiful land, inevitably and justifiably utilized by its citizens.

We built these views to examine consumption, progress and the changing landscape.

Barbara Ciurej & Lindsay Lochman (USA). Collaborate on photographic projects that address the confluence of history, myth and popular culture. Their work has been exhibited widely and their photographs are in public and private collections including the Art Institute of Chicago, Walker Art Center, Museum of Contemporary Photography, Milwaukee Art Museum, and the Beinecke Library at Yale University. They are currently exploring the potential of constructed landscapes to describe social inequality. Processed Views is currently on view at Rick Wester Fine Art ,New York, until July 29, 2016.

Barbara Ciurej & Lindsay Lochman (USA). Collaborate on photographic projects that address the confluence of history, myth and popular culture. Their work has been exhibited widely and their photographs are in public and private collections including the Art Institute of Chicago, Walker Art Center, Museum of Contemporary Photography, Milwaukee Art Museum, and the Beinecke Library at Yale University. They are currently exploring the potential of constructed landscapes to describe social inequality. Processed Views is currently on view at Rick Wester Fine Art ,New York, until July 29, 2016.Liz Hickok

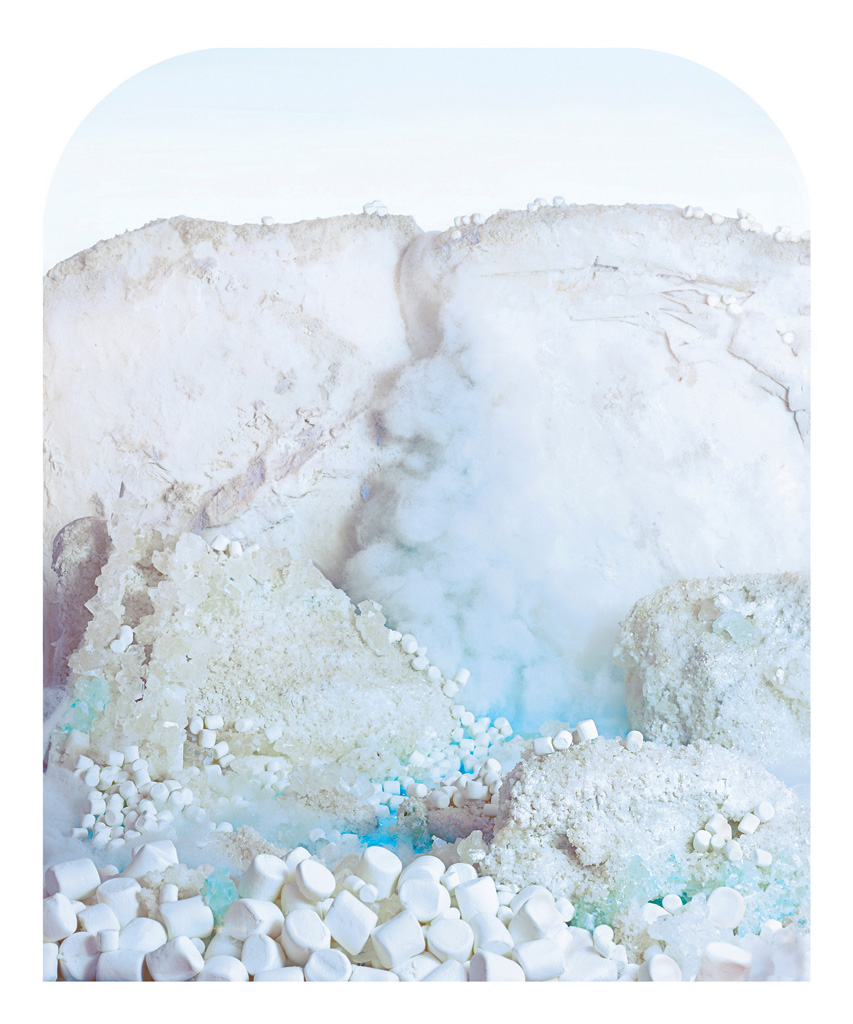

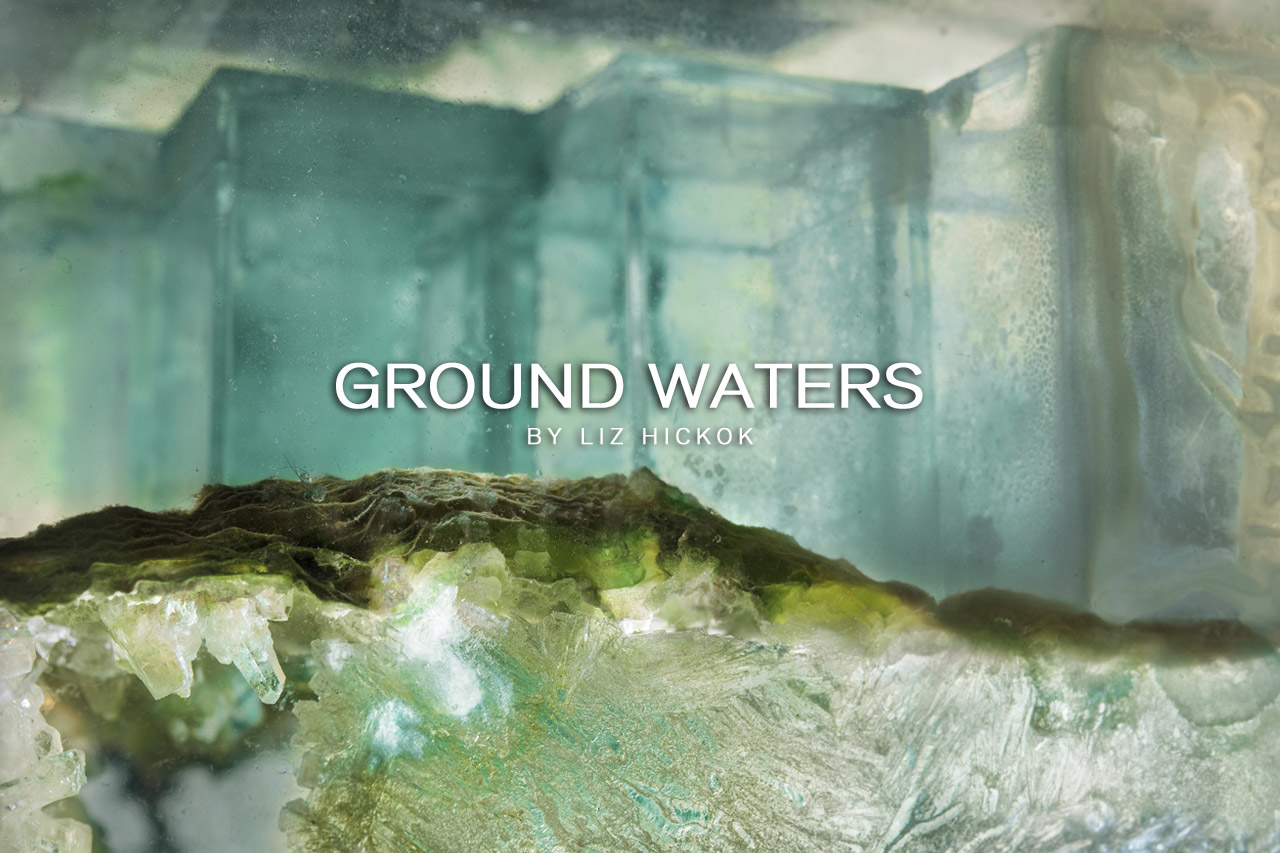

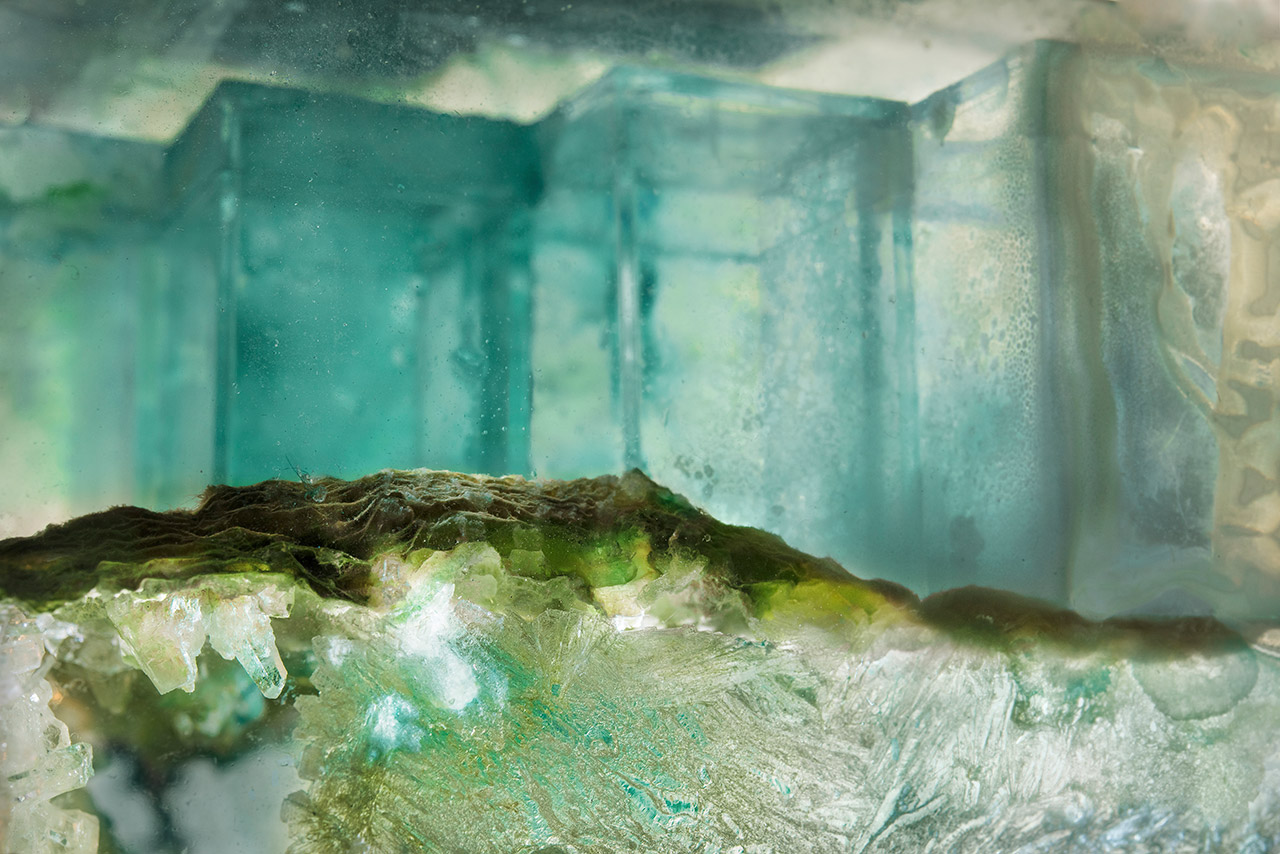

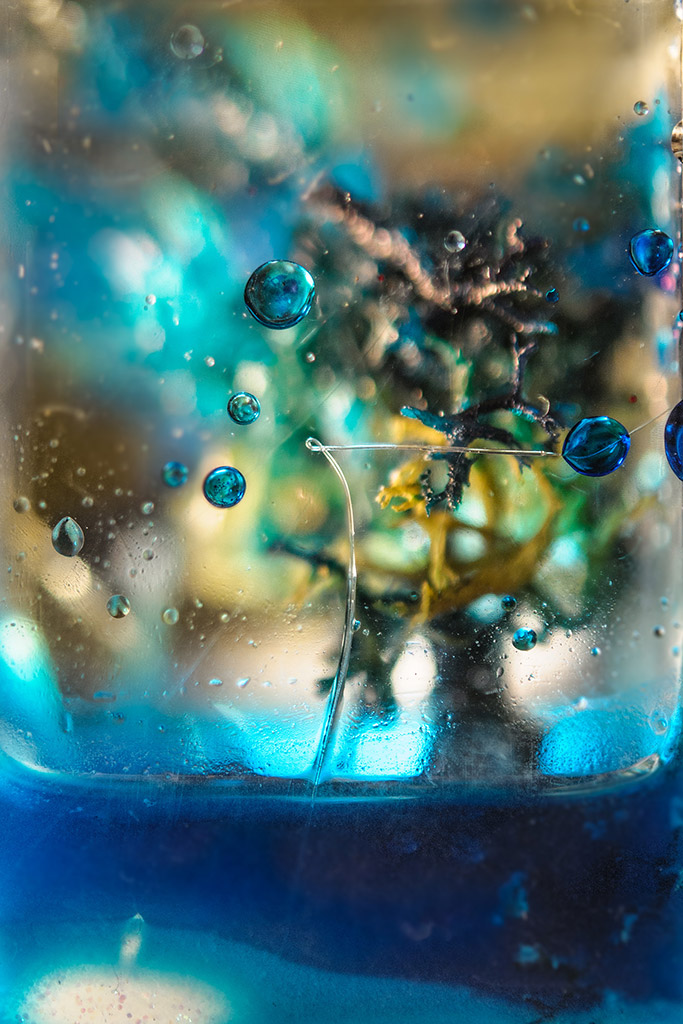

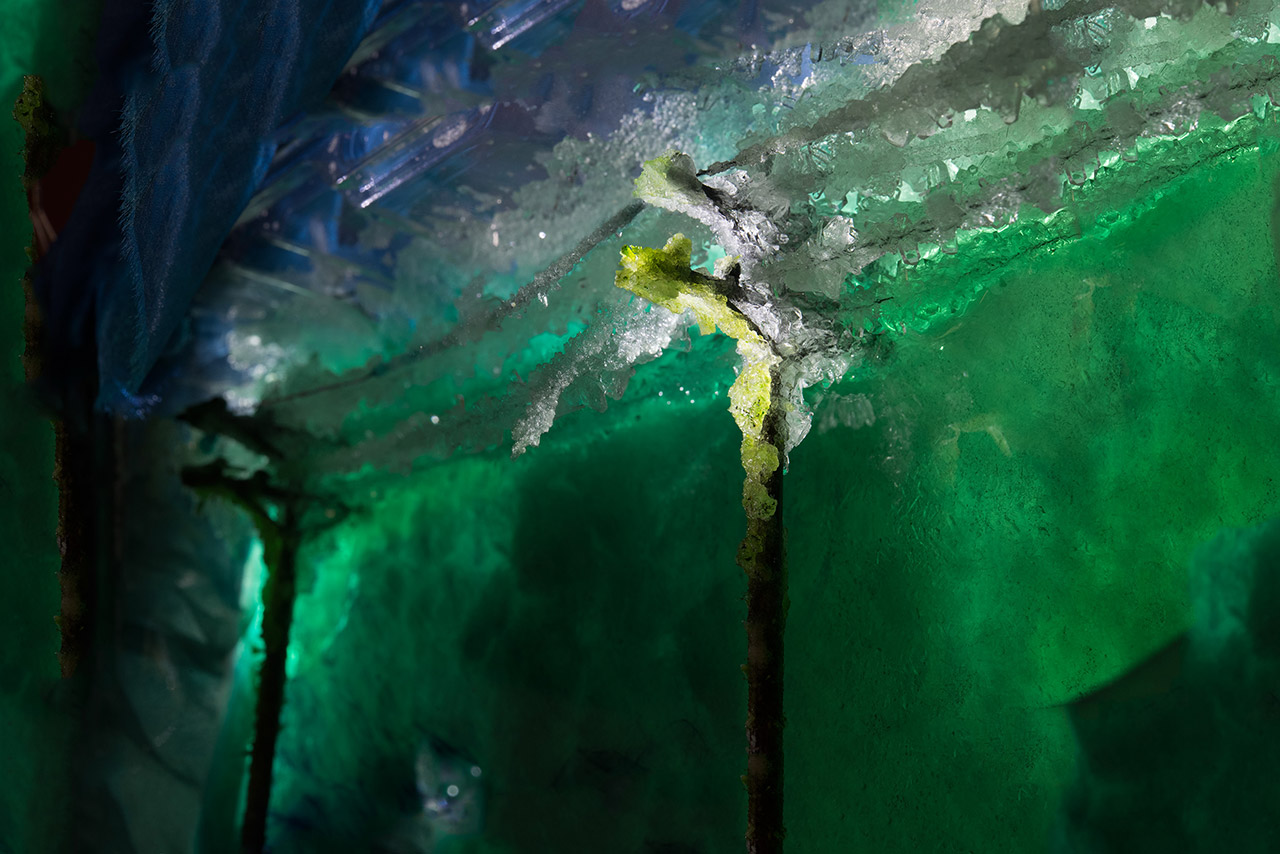

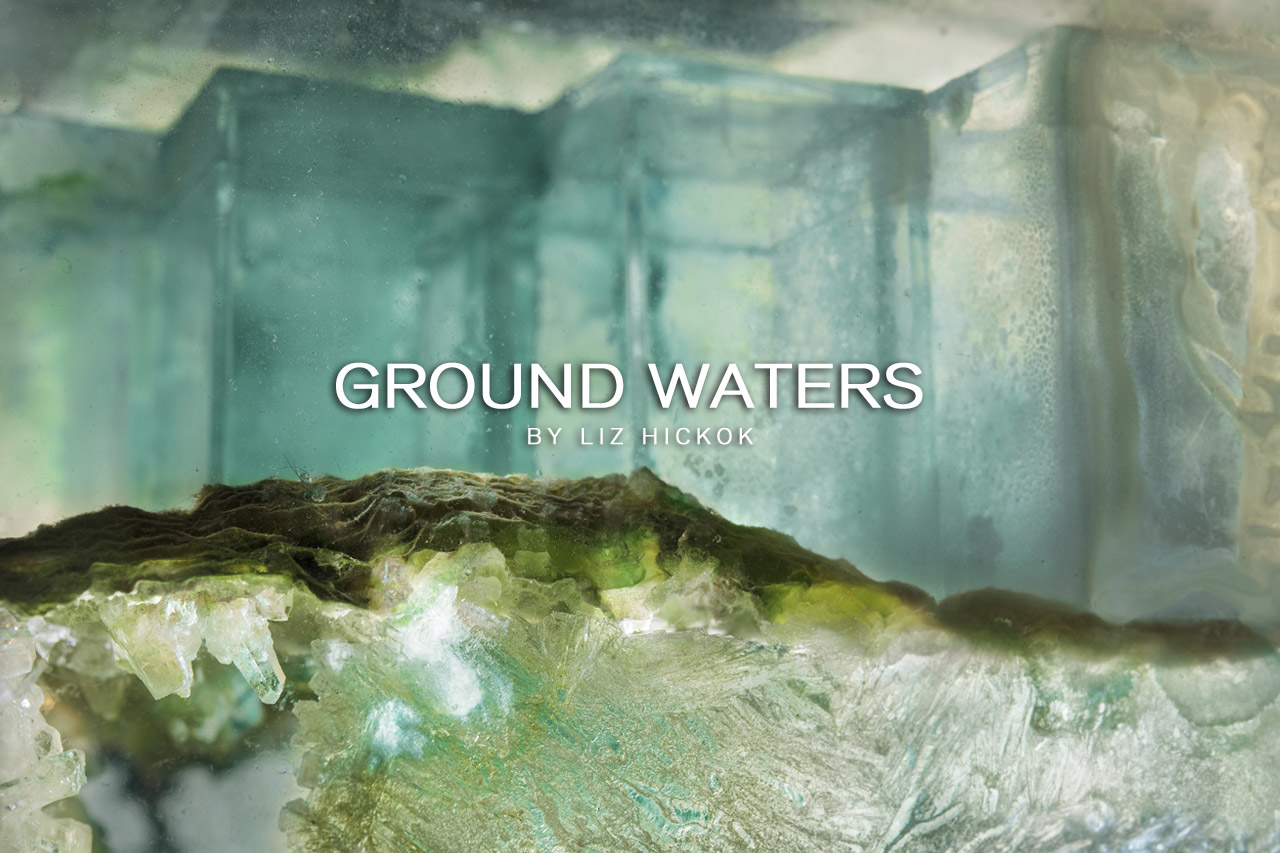

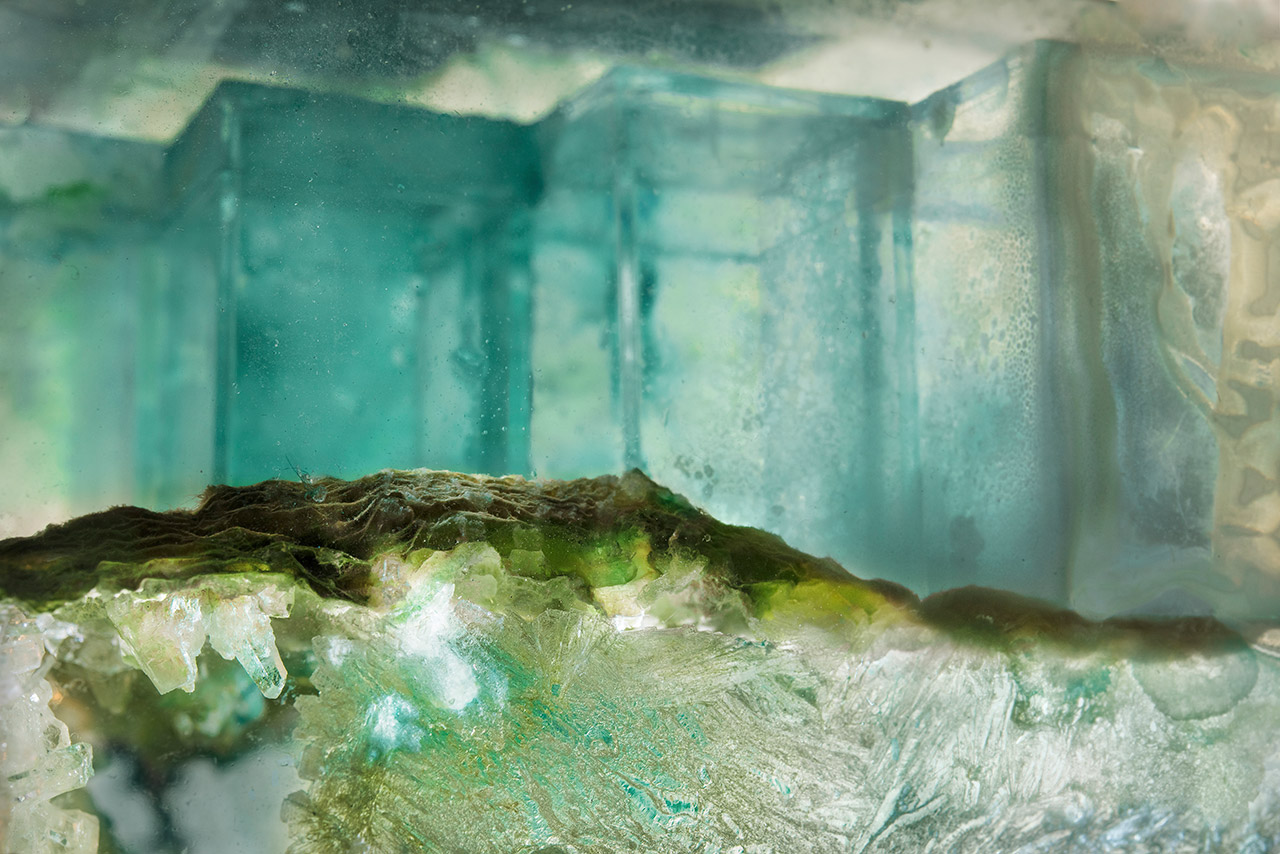

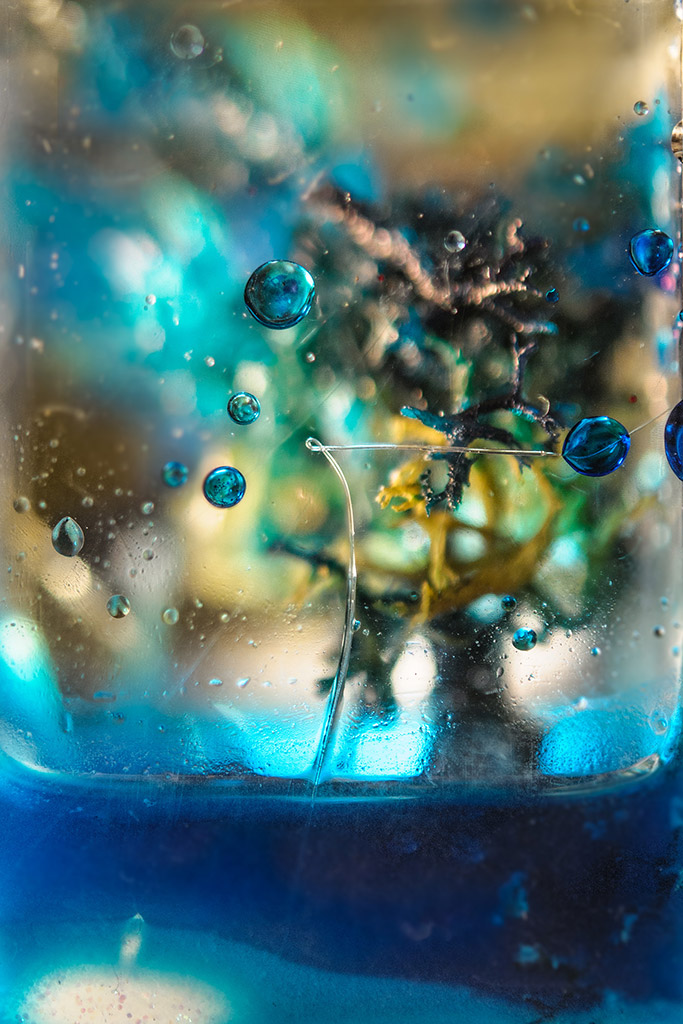

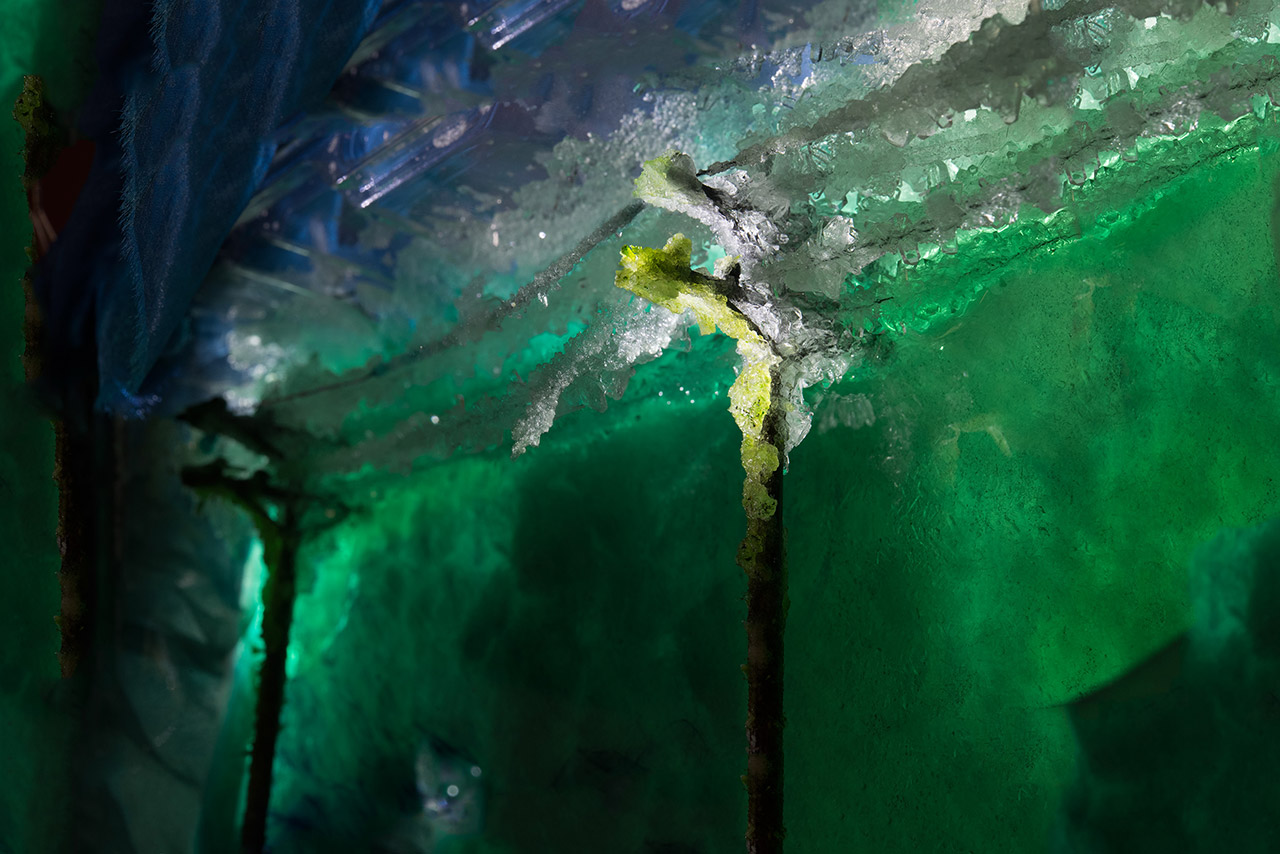

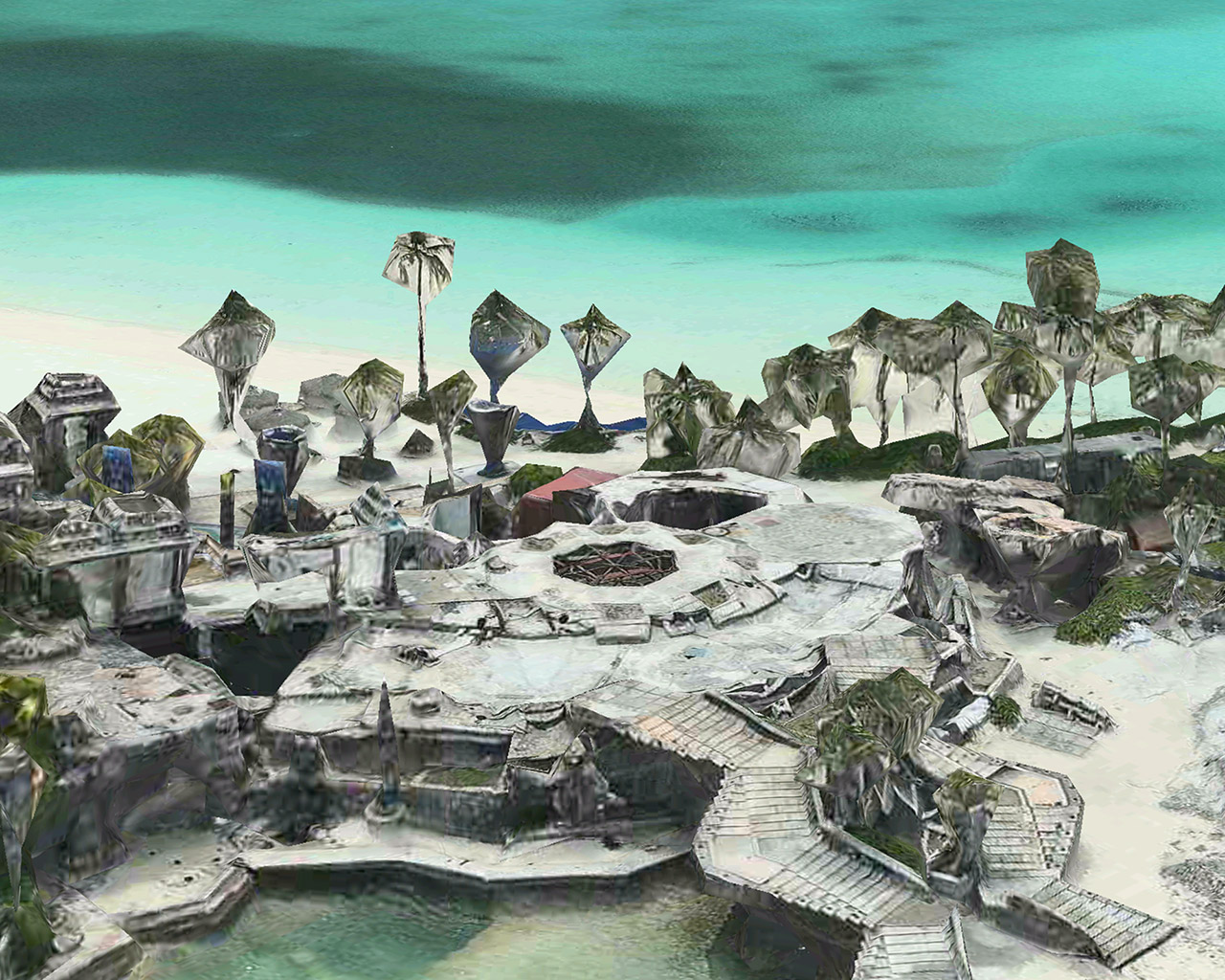

In my Ground Waters series I create miniature worlds where both natural and urban environments are overgrown by strange crystal formations. The colorful tableaux are playful in their materials, but they also allude to our environment being saturated by pollution.

I assemble and combine various elements, like a science experiment, and then I flood the scene with a liquid crystal solution. Over the course of a few hours, days, or weeks, the crystals re-form, permeating the small model. I enjoy the conflicting processes of control and lack thereof.

Liz Hickok (USA). artist working in photography, video, sculpture, and installation. Hickok received her Masters in Fine Arts from Mills College in Oakland, California. She earned a BFA and BA from the School of the Museum of Fine Arts and Tufts University in Boston, Massachusetts. Hickok lived and worked in Boston for over ten years before moving to the San Francisco Bay Area.

Liz Hickok (USA). artist working in photography, video, sculpture, and installation. Hickok received her Masters in Fine Arts from Mills College in Oakland, California. She earned a BFA and BA from the School of the Museum of Fine Arts and Tufts University in Boston, Massachusetts. Hickok lived and worked in Boston for over ten years before moving to the San Francisco Bay Area.

In my Ground Waters series I create miniature worlds where both natural and urban environments are overgrown by strange crystal formations. The colorful tableaux are playful in their materials, but they also allude to our environment being saturated by pollution.

I assemble and combine various elements, like a science experiment, and then I flood the scene with a liquid crystal solution. Over the course of a few hours, days, or weeks, the crystals re-form, permeating the small model. I enjoy the conflicting processes of control and lack thereof.

Liz Hickok (USA). artist working in photography, video, sculpture, and installation. Hickok received her Masters in Fine Arts from Mills College in Oakland, California. She earned a BFA and BA from the School of the Museum of Fine Arts and Tufts University in Boston, Massachusetts. Hickok lived and worked in Boston for over ten years before moving to the San Francisco Bay Area.

Liz Hickok (USA). artist working in photography, video, sculpture, and installation. Hickok received her Masters in Fine Arts from Mills College in Oakland, California. She earned a BFA and BA from the School of the Museum of Fine Arts and Tufts University in Boston, Massachusetts. Hickok lived and worked in Boston for over ten years before moving to the San Francisco Bay Area.Rebecca Reeve

The miracle of light pours over the green and brown expanse of saw grass and of water, shining and slowly moving, the grass and the water that is the meaning and the central fact of the Everglades. It is a river of grass. —Marjory Stoneman Douglas

I began this series during my AIRIE residency in the Everglades in December 2012. It draws inspiration from a ritual described in The Rings of Saturn by W.G. Sebald. In Holland in the 1600s, during the wake of the deceased, it was customary to cover all mirrors, landscape paintings and portraits in the home with cloths. It was believed this would make it easier for the soul to leave the body and subdue any temptations for it to stay in this world.

The ritual seemed, by extension, to be a confirmation of the deeply moving experience that one often feels in the natural environment, and thus provided both a literal and contextual frame within which to shoot the landscape, a portal from the domestic into the wilderness. The curtains, all purchased from Goodwill and Salvation Army stores in south Florida and Utah, represent a ‘social fabric’ with a history already attached to them. In our increasingly urban existence that ever distances us from the wilderness experience, the drapes serve as visual connectors to the familiar.

Images from the Marjory's World series will be on show in the exhibition 'Mise en Scene' opening March 16th at Hazan Projects in New York City.

Rebecca Reeve (England) She received her Bachelor of Fine Arts degree at Bath Spa University and a Masters of Visual Arts at the University of South Wales, Australia. Her photographs have been exhibited nationally and internationally including La Biennale de Montreal, (Canada), Freies Museum, Berlin, (Germany), Museum of Latin American Art, (Buenos Aires), EFA Project Space, (NYC) and the Masur Museum of Art, (Louisiana). In 2013 she was Artist in Residence at AIRIE and the recipient of the Artist in Exploration grant underwritten by Rolex. In 2016 she will be Artist in Residence at Joshua Tree National Park. She lives and works in New York City.

Rebecca Reeve (England) She received her Bachelor of Fine Arts degree at Bath Spa University and a Masters of Visual Arts at the University of South Wales, Australia. Her photographs have been exhibited nationally and internationally including La Biennale de Montreal, (Canada), Freies Museum, Berlin, (Germany), Museum of Latin American Art, (Buenos Aires), EFA Project Space, (NYC) and the Masur Museum of Art, (Louisiana). In 2013 she was Artist in Residence at AIRIE and the recipient of the Artist in Exploration grant underwritten by Rolex. In 2016 she will be Artist in Residence at Joshua Tree National Park. She lives and works in New York City.

The miracle of light pours over the green and brown expanse of saw grass and of water, shining and slowly moving, the grass and the water that is the meaning and the central fact of the Everglades. It is a river of grass. —Marjory Stoneman Douglas

I began this series during my AIRIE residency in the Everglades in December 2012. It draws inspiration from a ritual described in The Rings of Saturn by W.G. Sebald. In Holland in the 1600s, during the wake of the deceased, it was customary to cover all mirrors, landscape paintings and portraits in the home with cloths. It was believed this would make it easier for the soul to leave the body and subdue any temptations for it to stay in this world.

The ritual seemed, by extension, to be a confirmation of the deeply moving experience that one often feels in the natural environment, and thus provided both a literal and contextual frame within which to shoot the landscape, a portal from the domestic into the wilderness. The curtains, all purchased from Goodwill and Salvation Army stores in south Florida and Utah, represent a ‘social fabric’ with a history already attached to them. In our increasingly urban existence that ever distances us from the wilderness experience, the drapes serve as visual connectors to the familiar.

Images from the Marjory's World series will be on show in the exhibition 'Mise en Scene' opening March 16th at Hazan Projects in New York City.

Rebecca Reeve (England) She received her Bachelor of Fine Arts degree at Bath Spa University and a Masters of Visual Arts at the University of South Wales, Australia. Her photographs have been exhibited nationally and internationally including La Biennale de Montreal, (Canada), Freies Museum, Berlin, (Germany), Museum of Latin American Art, (Buenos Aires), EFA Project Space, (NYC) and the Masur Museum of Art, (Louisiana). In 2013 she was Artist in Residence at AIRIE and the recipient of the Artist in Exploration grant underwritten by Rolex. In 2016 she will be Artist in Residence at Joshua Tree National Park. She lives and works in New York City.