Vanessa Alcaíno & Alejandro Malo

Brown Hooded Kingfisher, (Halcyon albiventris), Chitengo Camp, Gorongosa National Park, Mozambique, 2011. By Joel Sartore

When we choose to address a landscape issue and, soon after, we realized its relationship with the theme of the FotoFest 2016 Biennial: Changing Circumstances: Looking at the Future of the Planet, we thought it appropriate to echo the concerns expressed during the festival. A few contents presented in this issue offer a digital version of the same exhibitions for our audience. However, this observation would be insufficient without emphasizing some of the ideas included in the book of the same name that drives us to insist on the invitation to peer into its pages.

Conceived as a collaboration between Frederick Baldwin and Wendy Watriss, founders of FotoFest, with Steven Evans, Executive Director of the festival, it integrates a diverse and broad mosaic of artists. In his introductory text, Steven Evans highlights the need to promote the exchange of ideas between artists who use different strategies to address the issue. It also contrast the divergence of gazes with the unifying leitmotif of Thomas E. Lovejoy and Geof Rayner essays that show an intrinsic connection between all artist’s concerns. Both essays provide strong arguments on the urgent need for action on climate change; the first, from the perspective of the Earth as a living organism, and the second by demonstrating the decisive role of human beings in their environment.

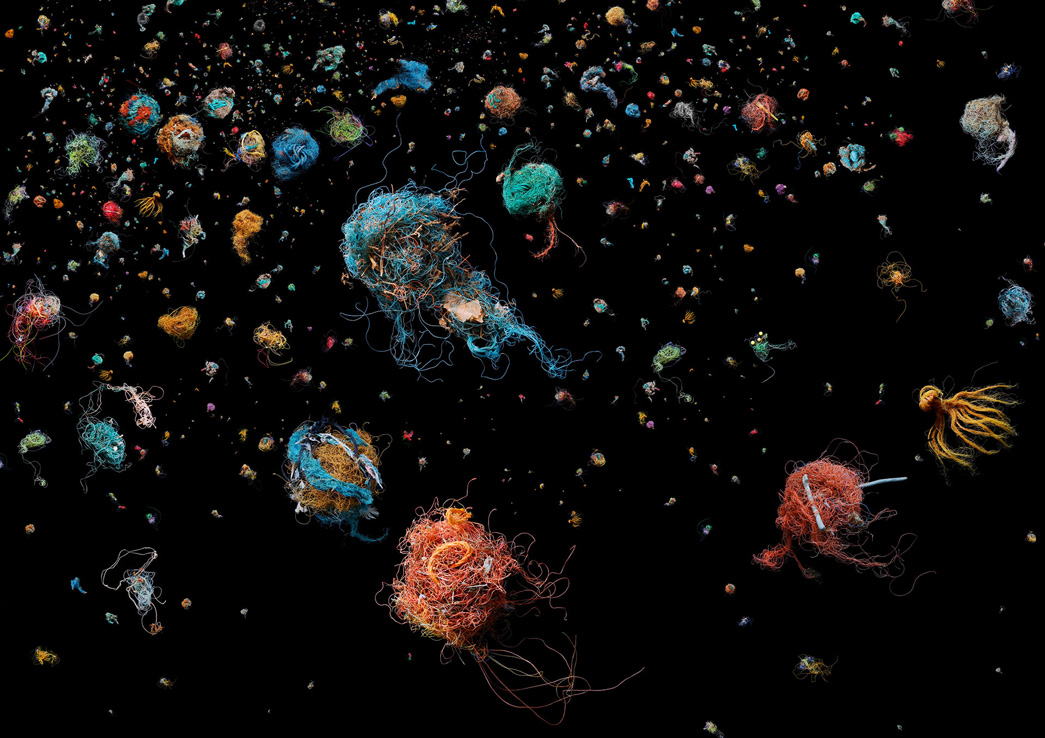

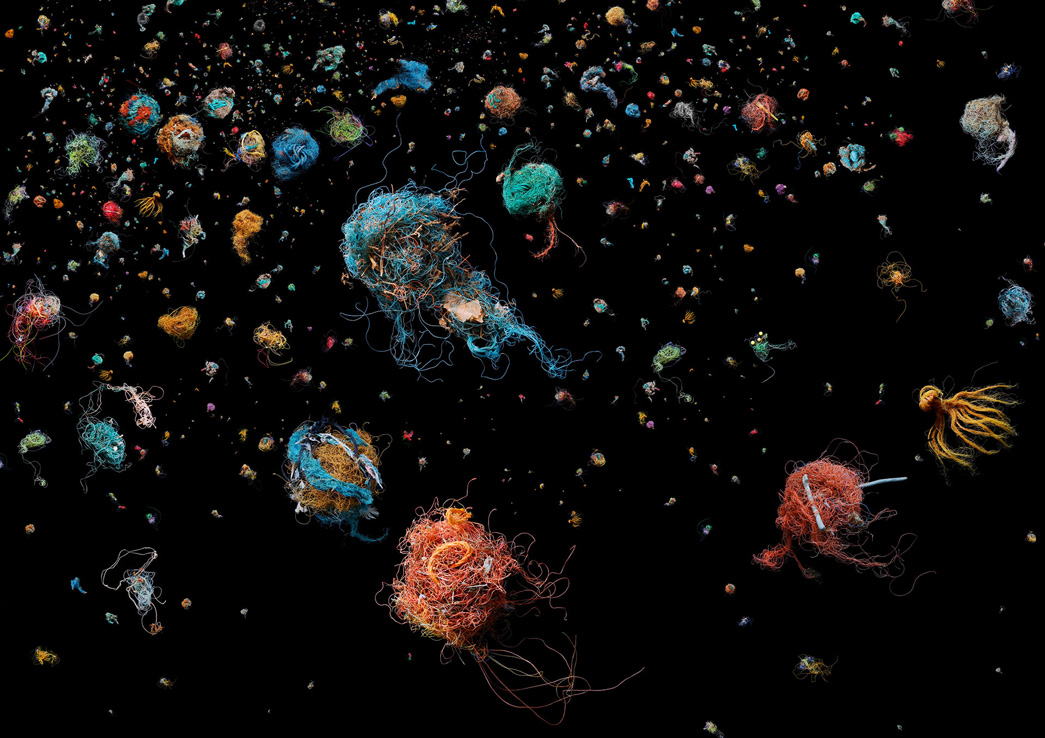

Bird’s Nest, 2011. Por Mandy Barker

Finally, Wendy Watriss gives voice to some questions that resonate with concerns we encountered during our research on the theme of landscape: "We have responsibility not only for our own well-being but that of the rest of the natural world? Can art stimulate new perspectives and new ways of seeing?” Photography has in its hands the potential to share with us realities that otherwise would be inaccessible. The images are not neutral, they feed imagination and foster reflections, being a very effective means to make any problem palpable, visible and close, to the point of being able to bring them into the political sphere and encourage agreements. We agree with Wendy’s view that art can itself stimulate and expand our world view and present innovative ways to address the issue of climate change. We should not allow ourselves to have skewed visions that only address and speak from a knowledge area or a region of the world. We must open to different cultures, include divergent views, draw new and different boundaries, create unique maps, put the world upside down, stir and divide it in various ways. That is the only way to visualize a future where rather than dominate nature, we can collaborate for its survival and ours. And this way of ‘seeing’ the world, and the new paths to our future, is what art may best express.

Vanessa Alcaíno Pizani (Venezuela, 1980). Lives and works in Mexico. Visual artist. She graduated in Philosophy at the Central University of Venezuela and has a Master’s degree in Spanish and Latin American Thought at the Autonomous University of Madrid (UAM). Since 1994, she has worked in the field of photography at various institutions and organisations in Venezuela, Argentina and Mexico. At the moment, she is part of the editorial team of zonezero.com.

Vanessa Alcaíno Pizani (Venezuela, 1980). Lives and works in Mexico. Visual artist. She graduated in Philosophy at the Central University of Venezuela and has a Master’s degree in Spanish and Latin American Thought at the Autonomous University of Madrid (UAM). Since 1994, she has worked in the field of photography at various institutions and organisations in Venezuela, Argentina and Mexico. At the moment, she is part of the editorial team of zonezero.com. Alejandro Malo (Mexico, 1972). Lives and works in Mexico and is the director of ZoneZero. Since 1993, he has taken part in various cultural projects and worked as an information technology consultant. He has collaborated in print and electronic publications, and given workshops and conferences on literature, creative writing, storytelling and technology. In 2009, Malo joined the team of the Fundación Pedro Meyer, where he directs the Archives and Technology departments.

Alejandro Malo (Mexico, 1972). Lives and works in Mexico and is the director of ZoneZero. Since 1993, he has taken part in various cultural projects and worked as an information technology consultant. He has collaborated in print and electronic publications, and given workshops and conferences on literature, creative writing, storytelling and technology. In 2009, Malo joined the team of the Fundación Pedro Meyer, where he directs the Archives and Technology departments.

Brown Hooded Kingfisher, (Halcyon albiventris), Chitengo Camp, Gorongosa National Park, Mozambique, 2011. By Joel Sartore

When we choose to address a landscape issue and, soon after, we realized its relationship with the theme of the FotoFest 2016 Biennial: Changing Circumstances: Looking at the Future of the Planet, we thought it appropriate to echo the concerns expressed during the festival. A few contents presented in this issue offer a digital version of the same exhibitions for our audience. However, this observation would be insufficient without emphasizing some of the ideas included in the book of the same name that drives us to insist on the invitation to peer into its pages.

Conceived as a collaboration between Frederick Baldwin and Wendy Watriss, founders of FotoFest, with Steven Evans, Executive Director of the festival, it integrates a diverse and broad mosaic of artists. In his introductory text, Steven Evans highlights the need to promote the exchange of ideas between artists who use different strategies to address the issue. It also contrast the divergence of gazes with the unifying leitmotif of Thomas E. Lovejoy and Geof Rayner essays that show an intrinsic connection between all artist’s concerns. Both essays provide strong arguments on the urgent need for action on climate change; the first, from the perspective of the Earth as a living organism, and the second by demonstrating the decisive role of human beings in their environment.

Bird’s Nest, 2011. Por Mandy Barker

Finally, Wendy Watriss gives voice to some questions that resonate with concerns we encountered during our research on the theme of landscape: "We have responsibility not only for our own well-being but that of the rest of the natural world? Can art stimulate new perspectives and new ways of seeing?” Photography has in its hands the potential to share with us realities that otherwise would be inaccessible. The images are not neutral, they feed imagination and foster reflections, being a very effective means to make any problem palpable, visible and close, to the point of being able to bring them into the political sphere and encourage agreements. We agree with Wendy’s view that art can itself stimulate and expand our world view and present innovative ways to address the issue of climate change. We should not allow ourselves to have skewed visions that only address and speak from a knowledge area or a region of the world. We must open to different cultures, include divergent views, draw new and different boundaries, create unique maps, put the world upside down, stir and divide it in various ways. That is the only way to visualize a future where rather than dominate nature, we can collaborate for its survival and ours. And this way of ‘seeing’ the world, and the new paths to our future, is what art may best express.

Vanessa Alcaíno Pizani (Venezuela, 1980). Lives and works in Mexico. Visual artist. She graduated in Philosophy at the Central University of Venezuela and has a Master’s degree in Spanish and Latin American Thought at the Autonomous University of Madrid (UAM). Since 1994, she has worked in the field of photography at various institutions and organisations in Venezuela, Argentina and Mexico. At the moment, she is part of the editorial team of zonezero.com.

Vanessa Alcaíno Pizani (Venezuela, 1980). Lives and works in Mexico. Visual artist. She graduated in Philosophy at the Central University of Venezuela and has a Master’s degree in Spanish and Latin American Thought at the Autonomous University of Madrid (UAM). Since 1994, she has worked in the field of photography at various institutions and organisations in Venezuela, Argentina and Mexico. At the moment, she is part of the editorial team of zonezero.com. Alejandro Malo (Mexico, 1972). Lives and works in Mexico and is the director of ZoneZero. Since 1993, he has taken part in various cultural projects and worked as an information technology consultant. He has collaborated in print and electronic publications, and given workshops and conferences on literature, creative writing, storytelling and technology. In 2009, Malo joined the team of the Fundación Pedro Meyer, where he directs the Archives and Technology departments.

Alejandro Malo (Mexico, 1972). Lives and works in Mexico and is the director of ZoneZero. Since 1993, he has taken part in various cultural projects and worked as an information technology consultant. He has collaborated in print and electronic publications, and given workshops and conferences on literature, creative writing, storytelling and technology. In 2009, Malo joined the team of the Fundación Pedro Meyer, where he directs the Archives and Technology departments.Alejandro Malo

Cloud Phenomena of Maloja. Film by Arnold Fanck, 1924

Landscape, long before being image, was literature and longing. Since ancient times, almost every civilization led an educated class that longed to return to the simple life of the countryside, back to nature with its deeper order and less troubled appearance. In the West, despite its widespread tradition against the city life and akin to recover the rural simplicity, it is only during the Renaissance that the joy of those running away from the maddening crowds turns into the full enjoyment of nature, first in poetry and only afterwards as a growing presence in paintings. In the East, at least since China’s Tang Dynasty, a fertile dialogue is established around the landscape between poetry and painting, and the genre develops very soon and evolves in multiple aspects.

Centuries later, while other visual media were confronted by the emergence of photography to take in and emphasize the subjectivity of their gaze over this topic, photographic landscapes devote their attention to exoticism or the magnificence of natural views and offered a deceptive closeness to a naturalist interpretation. The romantic vision of nature took root strongly across images ranging from the Bisson brothers to Ansel Adams. In them, beauty was something external to be captured in each shot, a reserve where solitude was a regained innocence and open spaces offered an inexhaustible source of peacefulness for the contemplative eye under the changing light’s mantle.

Gradually, as these perspectives became advertising and marketing leitmotifs, this genre had to be reinvented and new possibilities sought elsewhere. Already in 1975, with the exhibition New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-Altered Landscape, it became clear that human intervention was inseparable from our new perception of landscape. The aseptic style of the authors gathered in this exhibition, considered almost forensic and where the emotional charge seemed absent, caused the sensation of being somehow close to a crime scene’s lingering memories, but devoid of its dramatic charge. During the following years, some authors, with a similar methodology but against this trend, looked after landscapes as representation of their own temperament, metaphor of an inner life that finds in the environment an affinity and a strong individual expressive capacity. Finally, photography assumed the same subjectivity of other means. As an example, Hiroshi Sugimoto wrote about his Seascapes: "Every time I view the sea, I feel a calming sense of security, as if visiting my ancestral home". In that phrase, anyone can guess a sort of poetic inclination and a strong artistic weight that facilitates dialogue with paintings, as was done in 2012 by exposing this series with Mark Rothko’s work.

However, Eden’s innocence became impossible in a world where human presence outreach tainted glaciers and forests with the same nonchalance. In the second half of the twentieth century, the landscape was transformed from man facing nature, to be a metaphor for our own humanity and, at the same time, scene of our fears, hopes and tragedies. We read as landscape every place where a scenario simulates an open space, no matter whether an emotional or conceptual projection of ourselves, but also we read it under the titanic action of mining, between the megalopolis’ streets or against the inventiveness of major transformation projects. Hybridization of genres has allowed the unreal calm of sensationalist scenes as in Fernando Brito’s pictures and the catastrophe of Chinese dumping sites of Yao Lu to be shown as images of bucolic appearance. We bit the fruit of our pride and today paradise is a shy promise. We need to build works, with concrete actions to transform the announced catastrophe in a redemptive epiphany. The landscape is, with its potential for imagination and denunciation, the much needed tool.

Alejandro Malo (Mexico, 1972). Lives and works in Mexico and is the director of ZoneZero. Since 1993, he has taken part in various cultural projects and worked as an information technology consultant. He has collaborated in print and electronic publications, and given workshops and conferences on literature, creative writing, storytelling and technology. In 2009, Malo joined the team of the Fundación Pedro Meyer, where he directs the Archives and Technology departments.

Alejandro Malo (Mexico, 1972). Lives and works in Mexico and is the director of ZoneZero. Since 1993, he has taken part in various cultural projects and worked as an information technology consultant. He has collaborated in print and electronic publications, and given workshops and conferences on literature, creative writing, storytelling and technology. In 2009, Malo joined the team of the Fundación Pedro Meyer, where he directs the Archives and Technology departments.

Cloud Phenomena of Maloja. Film by Arnold Fanck, 1924

Landscape, long before being image, was literature and longing. Since ancient times, almost every civilization led an educated class that longed to return to the simple life of the countryside, back to nature with its deeper order and less troubled appearance. In the West, despite its widespread tradition against the city life and akin to recover the rural simplicity, it is only during the Renaissance that the joy of those running away from the maddening crowds turns into the full enjoyment of nature, first in poetry and only afterwards as a growing presence in paintings. In the East, at least since China’s Tang Dynasty, a fertile dialogue is established around the landscape between poetry and painting, and the genre develops very soon and evolves in multiple aspects.

Centuries later, while other visual media were confronted by the emergence of photography to take in and emphasize the subjectivity of their gaze over this topic, photographic landscapes devote their attention to exoticism or the magnificence of natural views and offered a deceptive closeness to a naturalist interpretation. The romantic vision of nature took root strongly across images ranging from the Bisson brothers to Ansel Adams. In them, beauty was something external to be captured in each shot, a reserve where solitude was a regained innocence and open spaces offered an inexhaustible source of peacefulness for the contemplative eye under the changing light’s mantle.

Gradually, as these perspectives became advertising and marketing leitmotifs, this genre had to be reinvented and new possibilities sought elsewhere. Already in 1975, with the exhibition New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-Altered Landscape, it became clear that human intervention was inseparable from our new perception of landscape. The aseptic style of the authors gathered in this exhibition, considered almost forensic and where the emotional charge seemed absent, caused the sensation of being somehow close to a crime scene’s lingering memories, but devoid of its dramatic charge. During the following years, some authors, with a similar methodology but against this trend, looked after landscapes as representation of their own temperament, metaphor of an inner life that finds in the environment an affinity and a strong individual expressive capacity. Finally, photography assumed the same subjectivity of other means. As an example, Hiroshi Sugimoto wrote about his Seascapes: "Every time I view the sea, I feel a calming sense of security, as if visiting my ancestral home". In that phrase, anyone can guess a sort of poetic inclination and a strong artistic weight that facilitates dialogue with paintings, as was done in 2012 by exposing this series with Mark Rothko’s work.

However, Eden’s innocence became impossible in a world where human presence outreach tainted glaciers and forests with the same nonchalance. In the second half of the twentieth century, the landscape was transformed from man facing nature, to be a metaphor for our own humanity and, at the same time, scene of our fears, hopes and tragedies. We read as landscape every place where a scenario simulates an open space, no matter whether an emotional or conceptual projection of ourselves, but also we read it under the titanic action of mining, between the megalopolis’ streets or against the inventiveness of major transformation projects. Hybridization of genres has allowed the unreal calm of sensationalist scenes as in Fernando Brito’s pictures and the catastrophe of Chinese dumping sites of Yao Lu to be shown as images of bucolic appearance. We bit the fruit of our pride and today paradise is a shy promise. We need to build works, with concrete actions to transform the announced catastrophe in a redemptive epiphany. The landscape is, with its potential for imagination and denunciation, the much needed tool.

Alejandro Malo (Mexico, 1972). Lives and works in Mexico and is the director of ZoneZero. Since 1993, he has taken part in various cultural projects and worked as an information technology consultant. He has collaborated in print and electronic publications, and given workshops and conferences on literature, creative writing, storytelling and technology. In 2009, Malo joined the team of the Fundación Pedro Meyer, where he directs the Archives and Technology departments.

Alejandro Malo (Mexico, 1972). Lives and works in Mexico and is the director of ZoneZero. Since 1993, he has taken part in various cultural projects and worked as an information technology consultant. He has collaborated in print and electronic publications, and given workshops and conferences on literature, creative writing, storytelling and technology. In 2009, Malo joined the team of the Fundación Pedro Meyer, where he directs the Archives and Technology departments.Alejandro Malo

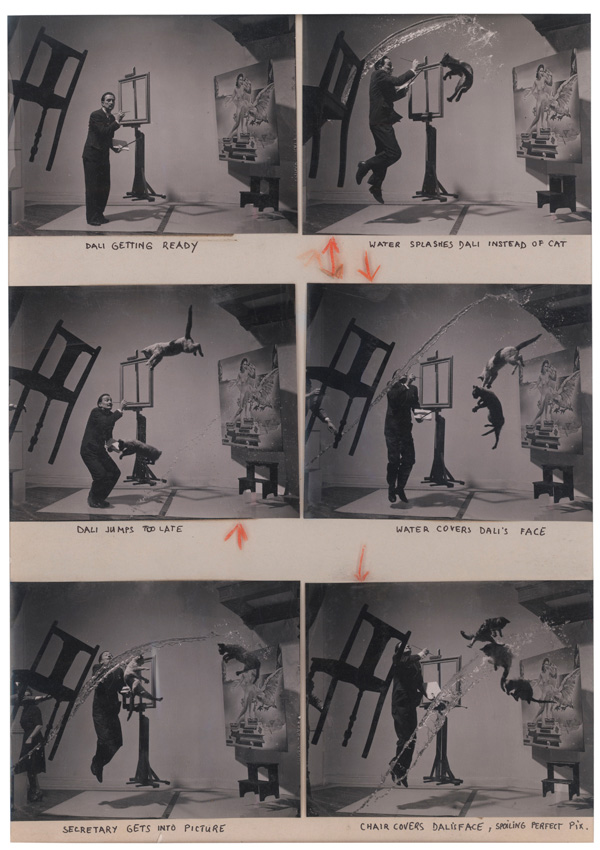

In Postproduction, I try to show that artists' intuitive relationship with art history is now going beyond what we call "the art of appropriation," which naturally infers an ideology of ownership, and moving toward a culture of the use of forms, a culture of constant activity of signs based on a collective ideal: sharing. —Nicolas Bourriaud.

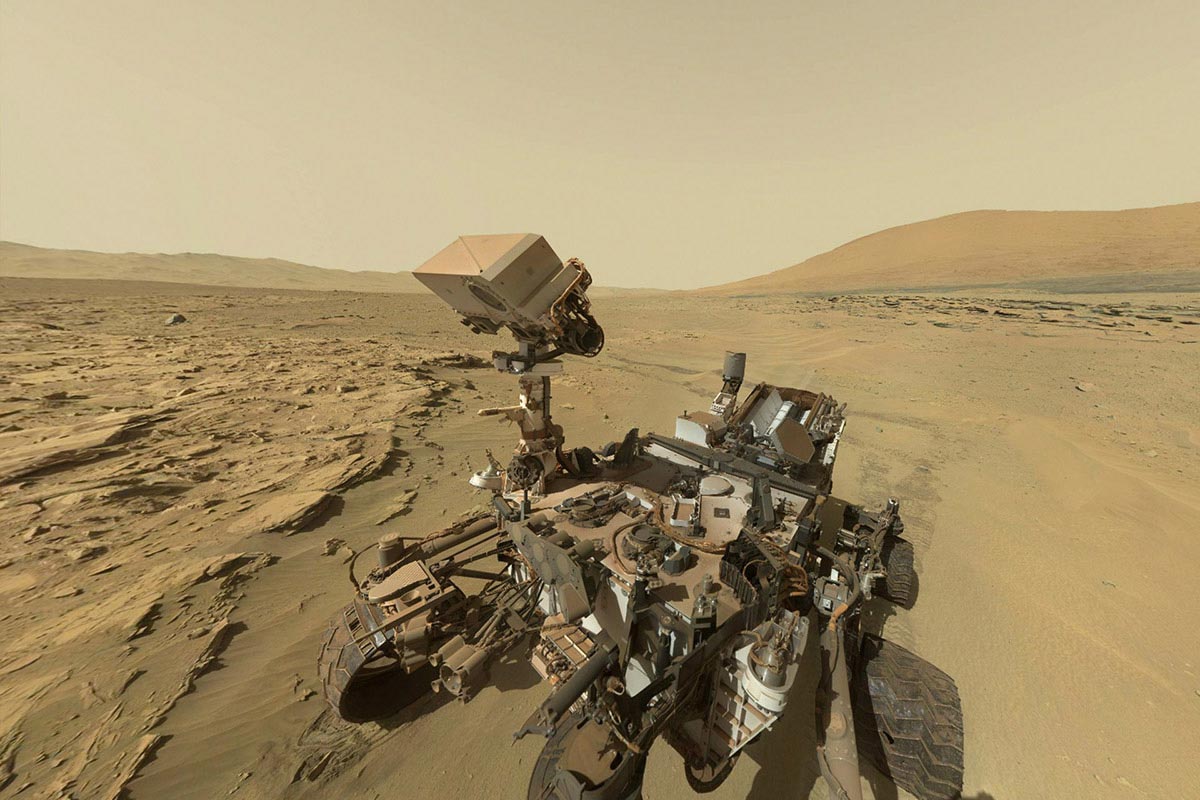

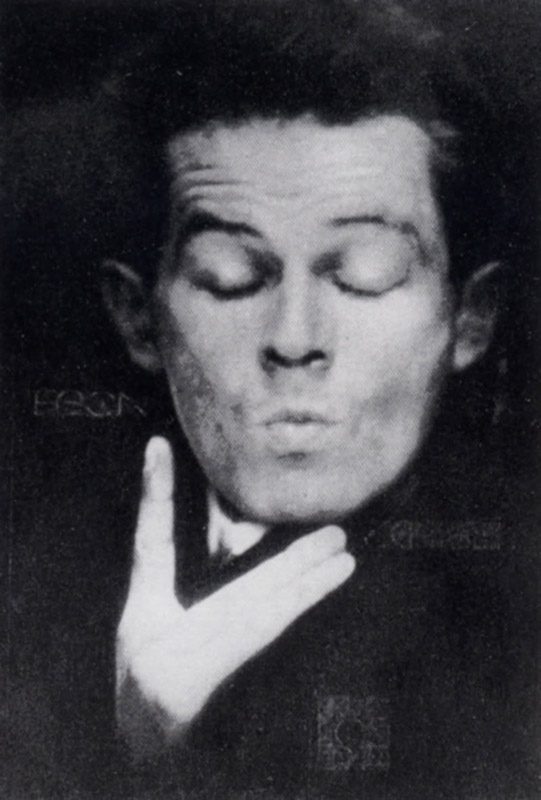

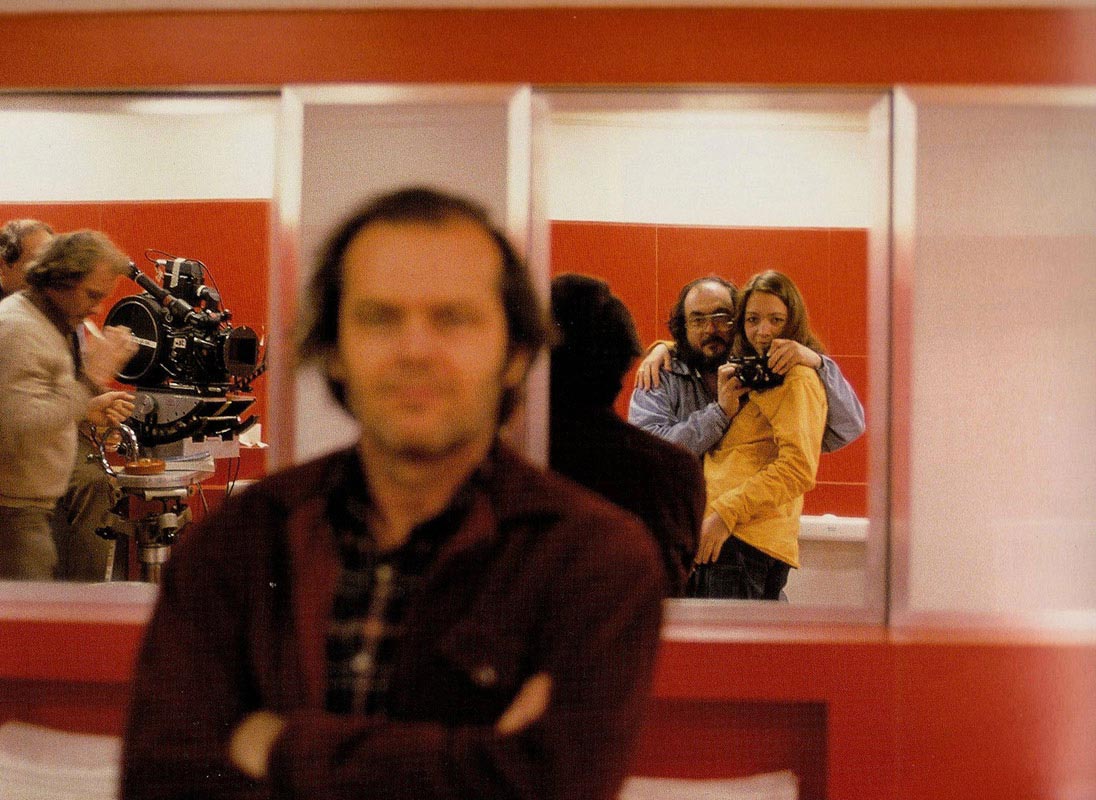

Scene of the film Metropolis by Fritz Lang, 1927.

For some time now, the resource of appropriation in photography has gone from being a subversive and provocative act to being, in many cases, the catch phrase which seeks to associate the prestige of previous artworks and contexts with fresh projects. The very concept of appropriation assumes the possibility of appropriating a material aspect of an image which is becoming more and more intangible. Due to the increasing production, consumption and transformation of images in a digital format, there is now an infinite number of possible reincarnations of not only every photograph, but also of its copies and variants, and of other photographs which it references, parodies or recreates. This never-ending cascade of repetitions and similarities has rendered unnecessary any fight against the concepts of originality and authorship, which only a few decades ago, it seemed essential to question. Originality, at risk of showing itself up with touching naivety, has not evolved from being a different arrangement of very well-known elements. Similarly, authorship hardly ends up as the top hat from which, like a rabbit, a well-edited design made up of materials uploaded from almost indistinguishable references will appear. In such a scenario, what does artwork openly based on somebody else’s material suggest? What question does it raise and what answer does it provide? Or, ideally, what question would it raise and what answer would it give so as not to remain merely a superficial resource?

The first step in formulating a response is to recognize that the boundaries of this practice are imprecise. It is impossible to define the point at which the reinterpretation of archived material or their intervention turns into a practice of visual recycling and rewriting of its meaning. If we add to this catalogue of practices, collages and photo montages, as well as the found footage and the capture of three- dimensional representations (for example, Street View or Apple Maps), then the territory becomes immeasurable. However, perhaps it is this complexity itself that is the first supporting point: a project that is constructed from a remix does not conceal its debt to other sources, and instead demonstrates its aim of proposing a new interpretation of them, albeit in a modest way. This in itself highlights an ethical concern with respect to the rule of images. Here lies a commitment to not only inviting a reflective way of looking at a universe that already exists but also a desire to add meaning to this universe. This leads us to the following conclusion: a project of this kind calls for contextual boundaries to be fixed. In order to create a new meaning it is fundamental to acknowledge previous meanings and references. Whether this is achieved by means of footnotes, marginal notes or definition by the micro universe itself regarding the selection and shots it comprises, or even the sum of a variety of these resources, the result is always one step further away from the original sources.

Finally, making the effort to acknowledge the fact that an image derives from previous artwork and that it aspires to become part of a context allows us to deduce a final characteristic of these designs, a characteristic that we can call the ecology of photographic recycling. In a world in which images are created at an extraordinary pace and in which every image can be disposable, appropriation acknowledges that images can take on new meanings and be enriched by broader meanings. The unstoppable avalanche of production comes face to face with the reasoned observation of reproduction and the modest judgment of post-production. The decreasing value of originality counters analysis, and the curator’s panoramic vision opposes the author’s perspective.

If we admit that in between the practices of appropriation and remix lies a need for ethics and ecology, which themselves require individual assessment and research, perhaps we can better measure the current relevance of the latest designs and recognize the scope of each one. If we accept that this new economy of shared property adds as much economic value as it does symbolic value, perhaps we will then have more factors related to our notions about intellectual property to adjust to a more progressive framework. The questions from the photographic world - in which there is so much to see and so much to understand - are timely and certainly worth acknowledging. Are we capable of doing so?

Alejandro Malo (Mexico, 1972). Lives and works in Mexico and is the director of ZoneZero. Since 1993, he has taken part in various cultural projects and worked as an information technology consultant. He has collaborated in print and electronic publications, and given workshops and conferences on literature, creative writing, storytelling and technology. In 2009, Malo joined the team of the Fundación Pedro Meyer, where he directs the Archives and Technology departments.

Alejandro Malo (Mexico, 1972). Lives and works in Mexico and is the director of ZoneZero. Since 1993, he has taken part in various cultural projects and worked as an information technology consultant. He has collaborated in print and electronic publications, and given workshops and conferences on literature, creative writing, storytelling and technology. In 2009, Malo joined the team of the Fundación Pedro Meyer, where he directs the Archives and Technology departments.[core_state] => 1 [core_access] => 1 [core_metadata] => {"robots":"","author":"Alejandro Malo","rights":"","xreference":""} [core_created_user_id] => 838 [core_created_by_alias] => [core_created_time] => 2015-10-12 06:02:21 [core_images] => {"image_intro":"images\/categories\/apropiacion\/metropolis.gif","float_intro":"","image_intro_alt":"","image_intro_caption":"","image_fulltext":"images\/categories\/apropiacion\/metropolis.gif","float_fulltext":"","image_fulltext_alt":"","image_fulltext_caption":""} [core_modified_time] => 2016-05-19 17:00:34 [core_language] => en-GB [core_catid] => 63 [core_publish_up] => 2015-10-12 06:02:21 [core_publish_down] => 0000-00-00 00:00:00 [content_type_title] => Article [router] => ContentHelperRoute::getArticleRoute [author] => Elisa Rugo [author_email] => elisa@zonezero.com [link] => index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=331:appropriation-and-remix&catid=63&lang=en-GB [displayDate] => 2015-10-12 06:02:21 [event] => stdClass Object ( [afterDisplayTitle] => [beforeDisplayContent] => [afterDisplayContent] => ) [text] =>

In Postproduction, I try to show that artists' intuitive relationship with art history is now going beyond what we call "the art of appropriation," which naturally infers an ideology of ownership, and moving toward a culture of the use of forms, a culture of constant activity of signs based on a collective ideal: sharing. —Nicolas Bourriaud.

Scene of the film Metropolis by Fritz Lang, 1927.

For some time now, the resource of appropriation in photography has gone from being a subversive and provocative act to being, in many cases, the catch phrase which seeks to associate the prestige of previous artworks and contexts with fresh projects. The very concept of appropriation assumes the possibility of appropriating a material aspect of an image which is becoming more and more intangible. Due to the increasing production, consumption and transformation of images in a digital format, there is now an infinite number of possible reincarnations of not only every photograph, but also of its copies and variants, and of other photographs which it references, parodies or recreates. This never-ending cascade of repetitions and similarities has rendered unnecessary any fight against the concepts of originality and authorship, which only a few decades ago, it seemed essential to question. Originality, at risk of showing itself up with touching naivety, has not evolved from being a different arrangement of very well-known elements. Similarly, authorship hardly ends up as the top hat from which, like a rabbit, a well-edited design made up of materials uploaded from almost indistinguishable references will appear. In such a scenario, what does artwork openly based on somebody else’s material suggest? What question does it raise and what answer does it provide? Or, ideally, what question would it raise and what answer would it give so as not to remain merely a superficial resource?

The first step in formulating a response is to recognize that the boundaries of this practice are imprecise. It is impossible to define the point at which the reinterpretation of archived material or their intervention turns into a practice of visual recycling and rewriting of its meaning. If we add to this catalogue of practices, collages and photo montages, as well as the found footage and the capture of three- dimensional representations (for example, Street View or Apple Maps), then the territory becomes immeasurable. However, perhaps it is this complexity itself that is the first supporting point: a project that is constructed from a remix does not conceal its debt to other sources, and instead demonstrates its aim of proposing a new interpretation of them, albeit in a modest way. This in itself highlights an ethical concern with respect to the rule of images. Here lies a commitment to not only inviting a reflective way of looking at a universe that already exists but also a desire to add meaning to this universe. This leads us to the following conclusion: a project of this kind calls for contextual boundaries to be fixed. In order to create a new meaning it is fundamental to acknowledge previous meanings and references. Whether this is achieved by means of footnotes, marginal notes or definition by the micro universe itself regarding the selection and shots it comprises, or even the sum of a variety of these resources, the result is always one step further away from the original sources.

Finally, making the effort to acknowledge the fact that an image derives from previous artwork and that it aspires to become part of a context allows us to deduce a final characteristic of these designs, a characteristic that we can call the ecology of photographic recycling. In a world in which images are created at an extraordinary pace and in which every image can be disposable, appropriation acknowledges that images can take on new meanings and be enriched by broader meanings. The unstoppable avalanche of production comes face to face with the reasoned observation of reproduction and the modest judgment of post-production. The decreasing value of originality counters analysis, and the curator’s panoramic vision opposes the author’s perspective.

If we admit that in between the practices of appropriation and remix lies a need for ethics and ecology, which themselves require individual assessment and research, perhaps we can better measure the current relevance of the latest designs and recognize the scope of each one. If we accept that this new economy of shared property adds as much economic value as it does symbolic value, perhaps we will then have more factors related to our notions about intellectual property to adjust to a more progressive framework. The questions from the photographic world - in which there is so much to see and so much to understand - are timely and certainly worth acknowledging. Are we capable of doing so?

Alejandro Malo (Mexico, 1972). Lives and works in Mexico and is the director of ZoneZero. Since 1993, he has taken part in various cultural projects and worked as an information technology consultant. He has collaborated in print and electronic publications, and given workshops and conferences on literature, creative writing, storytelling and technology. In 2009, Malo joined the team of the Fundación Pedro Meyer, where he directs the Archives and Technology departments.

Alejandro Malo (Mexico, 1972). Lives and works in Mexico and is the director of ZoneZero. Since 1993, he has taken part in various cultural projects and worked as an information technology consultant. He has collaborated in print and electronic publications, and given workshops and conferences on literature, creative writing, storytelling and technology. In 2009, Malo joined the team of the Fundación Pedro Meyer, where he directs the Archives and Technology departments.[id] => 331 [language] => en-GB [catid] => 63 [jcfields] => Array ( ) ) 1

Ehekatl Hernández

The question is, what is the function of competitions and calls for submissions of activist, documentary or collaborative photography? There are countless initiatives with discourses calling for justice, change and equality, with excellent intentions and attempts to “give a presence to the least fortunate persons worldwide”, with a proposal that stifles these communities’ capacity to represent themselves, or construct their own imagination from the trenches, ghettos, neighborhoods or shanty towns.

The apparent contradiction of these initiatives is reflected in irregular results, often selected solely for their aesthetic value, which undoubtedly reflects the vision, perspective and conceptual and formal decisions of an author. In this regard, it is naïve to seek to “reflect reality”, and it is perhaps worth reconsidering the uses of photography to represent and document from other perspectives, the sum of which approaches offers a more reliable record, and must be completed by a vision from within the communities themselves. After all, it is the individuals immersed in them who experience most closely their own dynamics and value systems, and the aspects of greatest interest to them.

This does not mean that being external makes a vision invalid or unworthy. On the contrary, the reflection proposes that a register be adopted that involves the photographer more actively. Therefore, all these calls for submissions, competitions and participative initiatives, as well as photographers and producers, must distance themselves from traditional documentalism. The context of the individual or community photographed must be understood and assimilated by offering an interpretation that presents the authorial contribution and its specific approach to the topic, thus establishing an authentic dialogue, a means of integration, a to-ing and fro-ing, and ultimately a better understanding of the subject photographed and his environment. Indeed, the greatest value lies in experience and the dialogue established, always assuming that the final result is merely the interpretation and assimilation of this experience, rather than a distant discourse outside the community documented.

This poses a challenge to the entire system of values, conception, production and consumption of documentary photography, and though this idea has already been applied in photojournalism for several decades, it questions the validity of these reflections and criticism in an era in which technology is rethinking all photographic activity. Today, communities are representing themselves as never before thanks to the availability of capture devices and the almost immediate spread and distribution of images, as a first-hand record that is unintentionally documenting events in specific environments in every corner of the world from various angles. Undoubtedly, these competitions and calls for submissions will gradually increase in scope and number, although paradoxically, their selection criteria and consequently, objectives, are increasingly being questioned. Neither renown nor tradition exempts these initiatives from these new reflections and questioning, with targets ranging from the prestigious World Press Photo to modest announcements by NGOs, academic institutions or civil organizations.

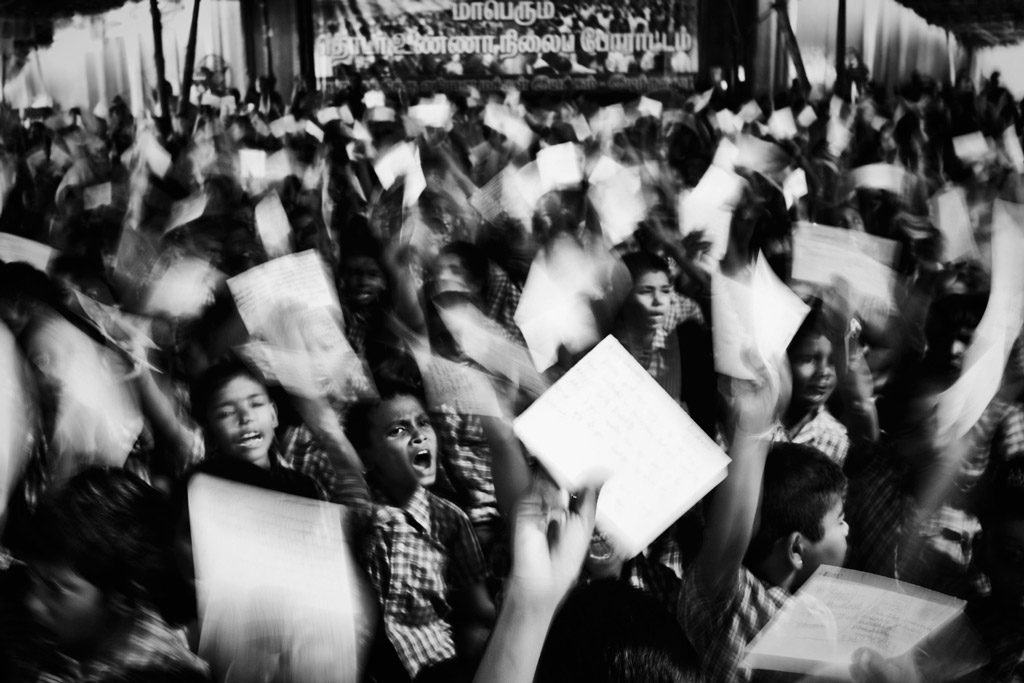

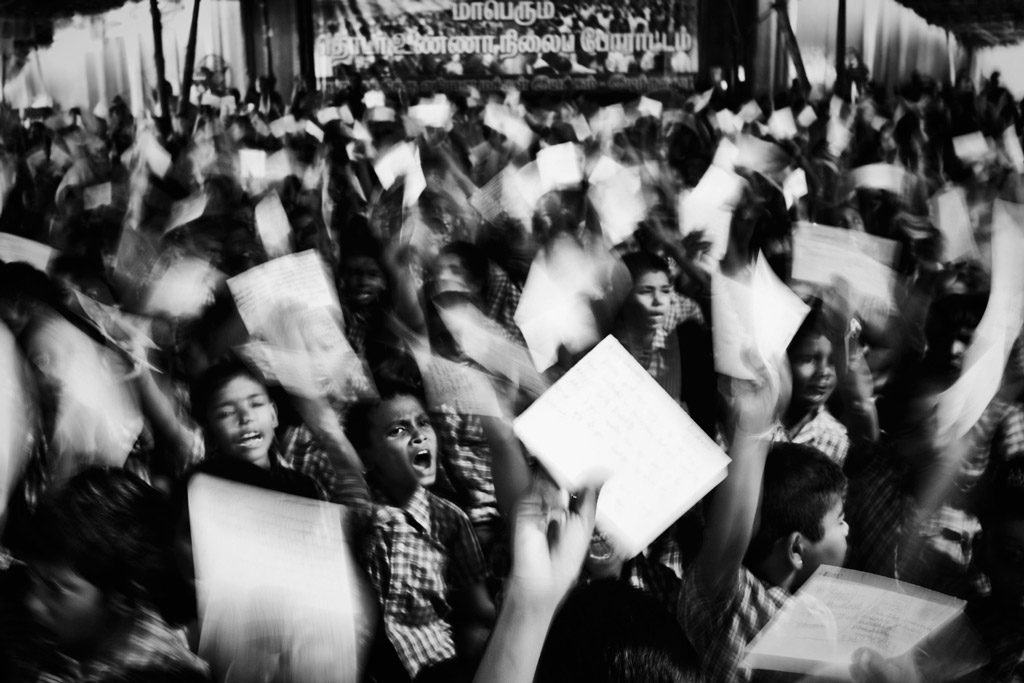

Children from Idinthakarai. Amirtharaj Stephen

This phenomenon does not diminish the importance of those initiatives in which the resources obtained from scholarships and prizes contribute directly to financing NGOs, social organizations and charities, and the management of these funds reflects other spheres. Moreover, there is a clearly-defined market for these projects, whose results correspond perfectly to the particular needs of various governments and official institutions but also social institutions and the public that consumes these images. In any case, what is questionable is the banner under which these works are disseminated, with the false premise of giving a face to the oppressed. This raises the same question: who is being represented, and why? Failing this, do these communities genuinely want to be represented in this manner?

However, we can afford to be optimistic, since several organizations have gradually begun toask themselves these questions, and are redefining their objectives and selection criteria. New participation dynamics for documentary makers and journalists are being established, which record and document the circumstances of their own environments. One example is CatchLigth (formerly Photo Philantropy) a platform for building ties based in California, which goes beyond being a renowned annual prize for photographic activism, basing its selection criteria mainly on the narrative value of the work, while also supporting the directors of audiovisual projects with social content through a system of liaisons with technological sponsors for the production and dissemination of the works produced.

Thus, given this outlook, we may be closer to obtaining an answer to the initial questioning process, which suggests that the true contribution and function of these events and calls for submissions should be to bring together all these points of view, to construct a broader experience based on a three-dimensional record approached from all angles, as is done by Donald Weber and its questioning of the crisis of photojournalism and documentalism. To achieve this new point of view, the objectivity once so zealously pursued must cease to be the canon on which to base the selection and judgment criteria of social competitions and calls for submissions, in order to achieve a closer approximation and better understanding of these other realities.

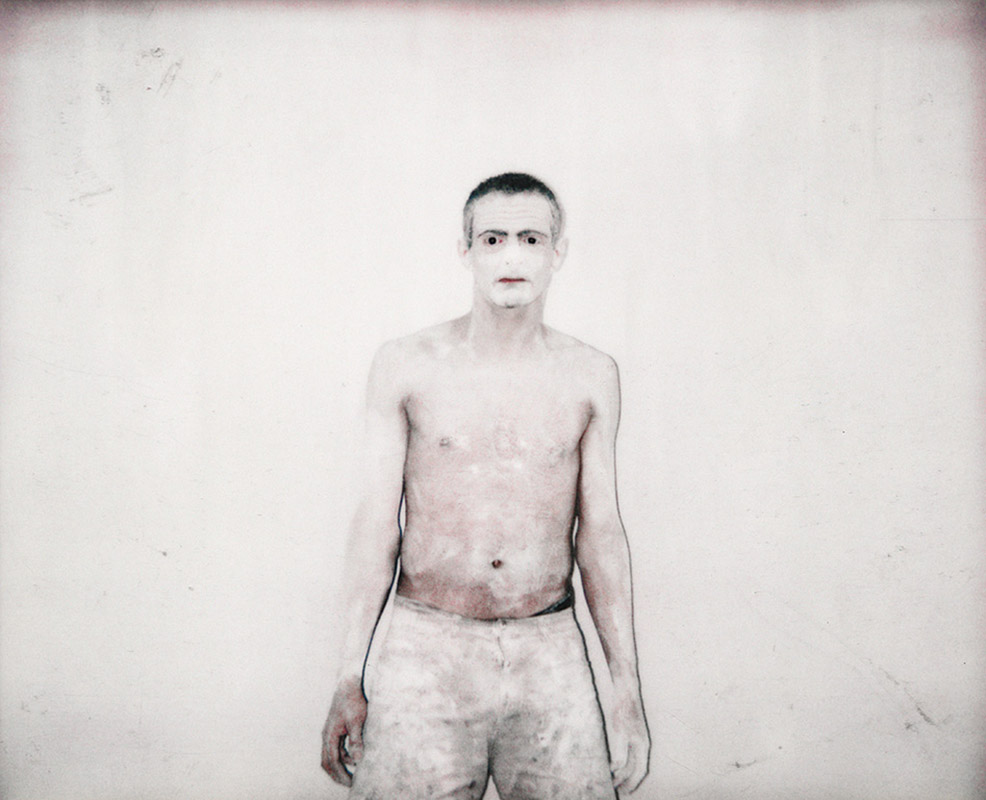

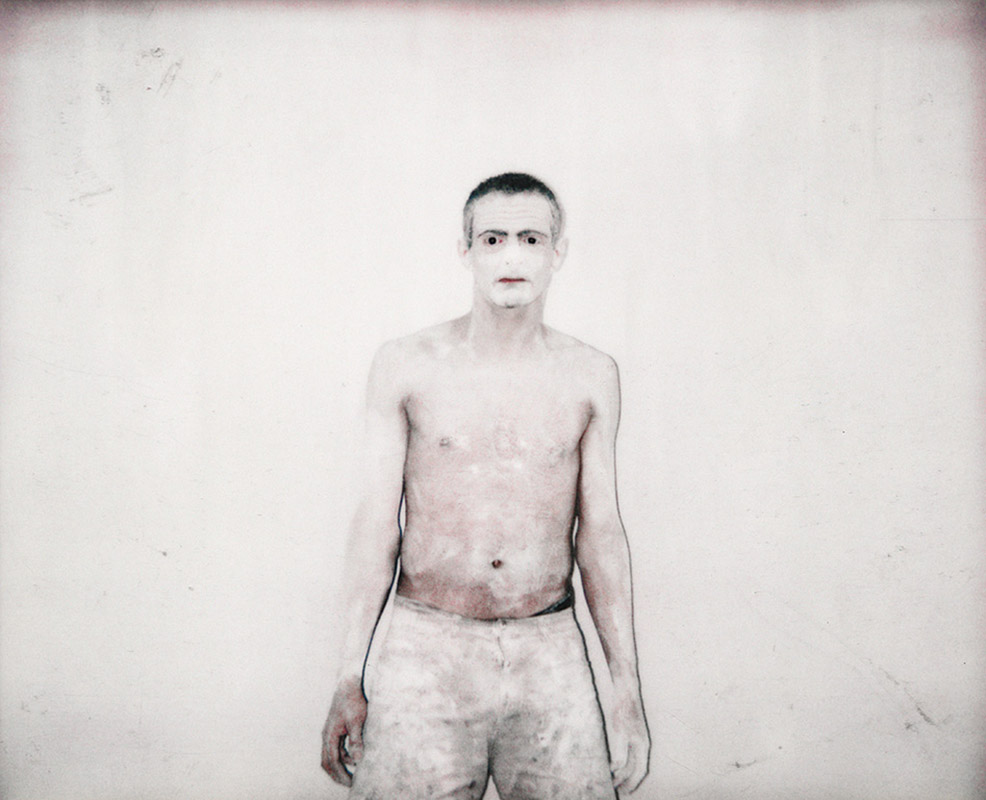

Dmitry Chizhevskiy, 27, had his left eye permanently destroyed by homophobes - Mads Nissen

Ehekatl Hernández (México, 1975) received a Bachelor’s Degree in Graphic Design from the Escuela Nacional de Artes Plásticas at UNAM in Mexico, and a Master’s Degree in Multimedia Applications from the Universidad Poltécnica de Catalunya in Spain. He has over 15 years’ experience in graphic design and planning, developing and implementing web projects. Hernández has given diploma courses in web design at UNAM. He has spent nine years contributing to the web design and multimedia area at zonezero.com, and also works as a consultant for various companies as well as coordinating the e-learning system of the Virtual Campus of the Pedro Meyer Foundation.

Ehekatl Hernández (México, 1975) received a Bachelor’s Degree in Graphic Design from the Escuela Nacional de Artes Plásticas at UNAM in Mexico, and a Master’s Degree in Multimedia Applications from the Universidad Poltécnica de Catalunya in Spain. He has over 15 years’ experience in graphic design and planning, developing and implementing web projects. Hernández has given diploma courses in web design at UNAM. He has spent nine years contributing to the web design and multimedia area at zonezero.com, and also works as a consultant for various companies as well as coordinating the e-learning system of the Virtual Campus of the Pedro Meyer Foundation.[core_state] => 1 [core_access] => 1 [core_metadata] => {"robots":"","author":"Ehekatl Hern\u00e1ndez","rights":"","xreference":""} [core_created_user_id] => 841 [core_created_by_alias] => [core_created_time] => 2015-08-10 19:46:15 [core_images] => {"image_intro":"images\/categories\/collective-representation\/fotocolaborativa.jpg","float_intro":"","image_intro_alt":"","image_intro_caption":"","image_fulltext":"images\/categories\/collective-representation\/fotocolaborativa.jpg","float_fulltext":"","image_fulltext_alt":"","image_fulltext_caption":""} [core_modified_time] => 2018-06-29 16:38:29 [core_language] => en-GB [core_catid] => 59 [core_publish_up] => 2015-08-10 19:46:15 [core_publish_down] => 0000-00-00 00:00:00 [content_type_title] => Article [router] => ContentHelperRoute::getArticleRoute [author] => [author_email] => [link] => index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=316:activist-documentary-and-collaborative-photography&catid=59&lang=en-GB [displayDate] => 2015-08-10 19:46:15 [event] => stdClass Object ( [afterDisplayTitle] => [beforeDisplayContent] => [afterDisplayContent] => ) [text] =>

The question is, what is the function of competitions and calls for submissions of activist, documentary or collaborative photography? There are countless initiatives with discourses calling for justice, change and equality, with excellent intentions and attempts to “give a presence to the least fortunate persons worldwide”, with a proposal that stifles these communities’ capacity to represent themselves, or construct their own imagination from the trenches, ghettos, neighborhoods or shanty towns.

The apparent contradiction of these initiatives is reflected in irregular results, often selected solely for their aesthetic value, which undoubtedly reflects the vision, perspective and conceptual and formal decisions of an author. In this regard, it is naïve to seek to “reflect reality”, and it is perhaps worth reconsidering the uses of photography to represent and document from other perspectives, the sum of which approaches offers a more reliable record, and must be completed by a vision from within the communities themselves. After all, it is the individuals immersed in them who experience most closely their own dynamics and value systems, and the aspects of greatest interest to them.

This does not mean that being external makes a vision invalid or unworthy. On the contrary, the reflection proposes that a register be adopted that involves the photographer more actively. Therefore, all these calls for submissions, competitions and participative initiatives, as well as photographers and producers, must distance themselves from traditional documentalism. The context of the individual or community photographed must be understood and assimilated by offering an interpretation that presents the authorial contribution and its specific approach to the topic, thus establishing an authentic dialogue, a means of integration, a to-ing and fro-ing, and ultimately a better understanding of the subject photographed and his environment. Indeed, the greatest value lies in experience and the dialogue established, always assuming that the final result is merely the interpretation and assimilation of this experience, rather than a distant discourse outside the community documented.

This poses a challenge to the entire system of values, conception, production and consumption of documentary photography, and though this idea has already been applied in photojournalism for several decades, it questions the validity of these reflections and criticism in an era in which technology is rethinking all photographic activity. Today, communities are representing themselves as never before thanks to the availability of capture devices and the almost immediate spread and distribution of images, as a first-hand record that is unintentionally documenting events in specific environments in every corner of the world from various angles. Undoubtedly, these competitions and calls for submissions will gradually increase in scope and number, although paradoxically, their selection criteria and consequently, objectives, are increasingly being questioned. Neither renown nor tradition exempts these initiatives from these new reflections and questioning, with targets ranging from the prestigious World Press Photo to modest announcements by NGOs, academic institutions or civil organizations.

Children from Idinthakarai. Amirtharaj Stephen

This phenomenon does not diminish the importance of those initiatives in which the resources obtained from scholarships and prizes contribute directly to financing NGOs, social organizations and charities, and the management of these funds reflects other spheres. Moreover, there is a clearly-defined market for these projects, whose results correspond perfectly to the particular needs of various governments and official institutions but also social institutions and the public that consumes these images. In any case, what is questionable is the banner under which these works are disseminated, with the false premise of giving a face to the oppressed. This raises the same question: who is being represented, and why? Failing this, do these communities genuinely want to be represented in this manner?

However, we can afford to be optimistic, since several organizations have gradually begun toask themselves these questions, and are redefining their objectives and selection criteria. New participation dynamics for documentary makers and journalists are being established, which record and document the circumstances of their own environments. One example is CatchLigth (formerly Photo Philantropy) a platform for building ties based in California, which goes beyond being a renowned annual prize for photographic activism, basing its selection criteria mainly on the narrative value of the work, while also supporting the directors of audiovisual projects with social content through a system of liaisons with technological sponsors for the production and dissemination of the works produced.

Thus, given this outlook, we may be closer to obtaining an answer to the initial questioning process, which suggests that the true contribution and function of these events and calls for submissions should be to bring together all these points of view, to construct a broader experience based on a three-dimensional record approached from all angles, as is done by Donald Weber and its questioning of the crisis of photojournalism and documentalism. To achieve this new point of view, the objectivity once so zealously pursued must cease to be the canon on which to base the selection and judgment criteria of social competitions and calls for submissions, in order to achieve a closer approximation and better understanding of these other realities.

Dmitry Chizhevskiy, 27, had his left eye permanently destroyed by homophobes - Mads Nissen

Ehekatl Hernández (México, 1975) received a Bachelor’s Degree in Graphic Design from the Escuela Nacional de Artes Plásticas at UNAM in Mexico, and a Master’s Degree in Multimedia Applications from the Universidad Poltécnica de Catalunya in Spain. He has over 15 years’ experience in graphic design and planning, developing and implementing web projects. Hernández has given diploma courses in web design at UNAM. He has spent nine years contributing to the web design and multimedia area at zonezero.com, and also works as a consultant for various companies as well as coordinating the e-learning system of the Virtual Campus of the Pedro Meyer Foundation.

Ehekatl Hernández (México, 1975) received a Bachelor’s Degree in Graphic Design from the Escuela Nacional de Artes Plásticas at UNAM in Mexico, and a Master’s Degree in Multimedia Applications from the Universidad Poltécnica de Catalunya in Spain. He has over 15 years’ experience in graphic design and planning, developing and implementing web projects. Hernández has given diploma courses in web design at UNAM. He has spent nine years contributing to the web design and multimedia area at zonezero.com, and also works as a consultant for various companies as well as coordinating the e-learning system of the Virtual Campus of the Pedro Meyer Foundation.[id] => 316 [language] => en-GB [catid] => 59 [jcfields] => Array ( ) ) 1

Elisa Rugo

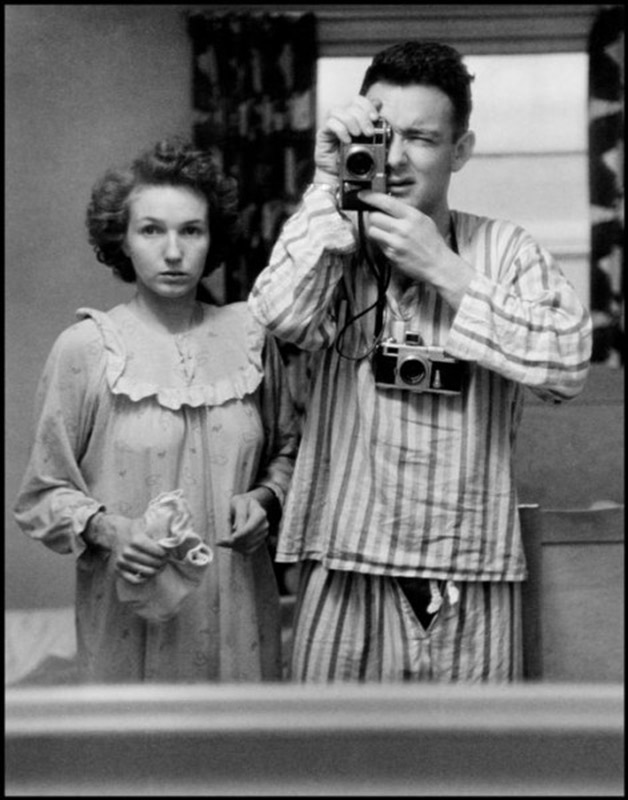

One of the greatest advantages of current photography, through its democratization as a tool and the technological advances in the media, is the guiding thread it establishes for collective representations in visual communication. This is largely the result of databases generated using key words, which provide information by describing and facilitating the identification of files and content. One of the most effective uses of this is the ubiquitous hashtag in social networks (Twitter, Instagram, Tumblr, FB). Eight years after Messina1 using the hashtag to group dialogues in social networks, this resource has produced endless possibilities not only for political and commercial marketing campaigns, but also for categorizing and linking information in a virtual world with millions of simultaneous thematic connections. It has served to increase the understanding of communities that would otherwise be hard to reach, which documentary photographers wish to comprehend and stop portraying from a distance.

everydayafrica. #Lagos fragment. Photo by Tom Saater @tomsaater

To what extent can one formalize and give presence and solidity to a proposal that derives from collaboration and the use of a social network?

Throughout its history, photography has been related to the personal and collective memory. This text will not tackle the debate regarding whether it is a reliable testimony of current reality, but rather concentrate on what visual language is doing, creating, recreating and communicating in the present. One of the current tools to trigger this dialogue is the hashtag, as a complement to the photographic image that has transformed everyday communication and has become a simple, inexpensive, everyday action on a massive, global scale. Simply accompanying an image by two or three words preceded by a hashtag enables others to access photograph albums categorized by location, topic, mood or format (#streetartchilango); to travel and identify in real time to these communities so far removed from our everyday lives yet so close to our language (everydayafrica, everydayiran) , or to concentrate a story in citizen testimonials and produce social movements, thus raising awareness and mobilizing resources in real life (#Egipto, #IranElection, #15-M, #BringBackOurGirls, #YoSoy132). This allows the hashtag to community gaze, offer a panorama of the phenomenon and collective representation online, and show its integrating function. But how can it be conserved?

everydayiran. Young women taking a selfie in the Bazaar of #Isfahan. #Iran. Photo by Aseem Gujar @myaseemgujar

Only two years ago, hashtags were not perceived as content networks, but studied from a mass perspective, leading to the highly ephemeral trending topics. However, there is increasing interest in researching and analyzing this kind of connections, to better understand the social, political, commercial circumstances, and of course, go beyond borders to learn about local and even personal events.

The archives produced by hashtags are real-time records and documents in the cloud that we fear so much, and where we find so it hard to place our entire body of work. It contains our everyday communication and, even if we are not aware of what we deliver, our way of seeing and thinking are latent within it. One option to preserve all this archive would be to produce a local database, or to continue to entrust this virtual universe with our history, to share, modify, increase, exchange, store, read, reread or even eliminate it.

The hashtag can therefore be considered an extension of the light Barthes called the umbilical cord, 2 the skin that we share with those who have photographed themselves to share who they are, what they do and how they live; to represent themselves and join this globalized digital world of metadata in which the photographer is no longer the only means of objective or subjective expression of reality, but now feeds into various disciplines and mediums that democratize it as a tool and a language in itself.

1. Chris Messina, an active defender of open code, suggested using the name hashtag on August 23, 2007, with a simple tweet: "How do you feel about using # (pound) for groups? As in #barcamp [msg]?".

2. A real body, located there, produced radiation that impressed me, located here. It does not matter how long the transmission lasts; the photo of the disappeared being impresses me as would the deferred rays of a star. A kind of umbilical cord joins the body of the object photographed to my gaze: light, though impalpable, is a carnal medium, a skin I share with the beings who have been photographed. – R. Barthes.

Elisa Rugo (México, 1980). Lives and works in Mexico. She is a photographer, videographer and a specialist in visual communication with a degree in Creative Visualisation at the University of Communication. In 2012, she took part in the seminar Contemporary Photography at the Image Centre. She has participated in collective exhibitions in Pachuca, Querétaro, Guadalajara and Mexico-City. At the moment, she is the art director of the websites fpmeyer.com and museodemujeres.com and she is part of the editorial team of zonezero.com. You can see her work at: elisarugo.pro

Elisa Rugo (México, 1980). Lives and works in Mexico. She is a photographer, videographer and a specialist in visual communication with a degree in Creative Visualisation at the University of Communication. In 2012, she took part in the seminar Contemporary Photography at the Image Centre. She has participated in collective exhibitions in Pachuca, Querétaro, Guadalajara and Mexico-City. At the moment, she is the art director of the websites fpmeyer.com and museodemujeres.com and she is part of the editorial team of zonezero.com. You can see her work at: elisarugo.proOne of the greatest advantages of current photography, through its democratization as a tool and the technological advances in the media, is the guiding thread it establishes for collective representations in visual communication. This is largely the result of databases generated using key words, which provide information by describing and facilitating the identification of files and content. One of the most effective uses of this is the ubiquitous hashtag in social networks (Twitter, Instagram, Tumblr, FB). Eight years after Messina1 using the hashtag to group dialogues in social networks, this resource has produced endless possibilities not only for political and commercial marketing campaigns, but also for categorizing and linking information in a virtual world with millions of simultaneous thematic connections. It has served to increase the understanding of communities that would otherwise be hard to reach, which documentary photographers wish to comprehend and stop portraying from a distance.

everydayafrica. #Lagos fragment. Photo by Tom Saater @tomsaater

To what extent can one formalize and give presence and solidity to a proposal that derives from collaboration and the use of a social network?

Throughout its history, photography has been related to the personal and collective memory. This text will not tackle the debate regarding whether it is a reliable testimony of current reality, but rather concentrate on what visual language is doing, creating, recreating and communicating in the present. One of the current tools to trigger this dialogue is the hashtag, as a complement to the photographic image that has transformed everyday communication and has become a simple, inexpensive, everyday action on a massive, global scale. Simply accompanying an image by two or three words preceded by a hashtag enables others to access photograph albums categorized by location, topic, mood or format (#streetartchilango); to travel and identify in real time to these communities so far removed from our everyday lives yet so close to our language (everydayafrica, everydayiran) , or to concentrate a story in citizen testimonials and produce social movements, thus raising awareness and mobilizing resources in real life (#Egipto, #IranElection, #15-M, #BringBackOurGirls, #YoSoy132). This allows the hashtag to community gaze, offer a panorama of the phenomenon and collective representation online, and show its integrating function. But how can it be conserved?

everydayiran. Young women taking a selfie in the Bazaar of #Isfahan. #Iran. Photo by Aseem Gujar @myaseemgujar

Only two years ago, hashtags were not perceived as content networks, but studied from a mass perspective, leading to the highly ephemeral trending topics. However, there is increasing interest in researching and analyzing this kind of connections, to better understand the social, political, commercial circumstances, and of course, go beyond borders to learn about local and even personal events.

The archives produced by hashtags are real-time records and documents in the cloud that we fear so much, and where we find so it hard to place our entire body of work. It contains our everyday communication and, even if we are not aware of what we deliver, our way of seeing and thinking are latent within it. One option to preserve all this archive would be to produce a local database, or to continue to entrust this virtual universe with our history, to share, modify, increase, exchange, store, read, reread or even eliminate it.

The hashtag can therefore be considered an extension of the light Barthes called the umbilical cord, 2 the skin that we share with those who have photographed themselves to share who they are, what they do and how they live; to represent themselves and join this globalized digital world of metadata in which the photographer is no longer the only means of objective or subjective expression of reality, but now feeds into various disciplines and mediums that democratize it as a tool and a language in itself.

1. Chris Messina, an active defender of open code, suggested using the name hashtag on August 23, 2007, with a simple tweet: "How do you feel about using # (pound) for groups? As in #barcamp [msg]?".

2. A real body, located there, produced radiation that impressed me, located here. It does not matter how long the transmission lasts; the photo of the disappeared being impresses me as would the deferred rays of a star. A kind of umbilical cord joins the body of the object photographed to my gaze: light, though impalpable, is a carnal medium, a skin I share with the beings who have been photographed. – R. Barthes.

Elisa Rugo (México, 1980). Lives and works in Mexico. She is a photographer, videographer and a specialist in visual communication with a degree in Creative Visualisation at the University of Communication. In 2012, she took part in the seminar Contemporary Photography at the Image Centre. She has participated in collective exhibitions in Pachuca, Querétaro, Guadalajara and Mexico-City. At the moment, she is the art director of the websites fpmeyer.com and museodemujeres.com and she is part of the editorial team of zonezero.com. You can see her work at: elisarugo.pro

Elisa Rugo (México, 1980). Lives and works in Mexico. She is a photographer, videographer and a specialist in visual communication with a degree in Creative Visualisation at the University of Communication. In 2012, she took part in the seminar Contemporary Photography at the Image Centre. She has participated in collective exhibitions in Pachuca, Querétaro, Guadalajara and Mexico-City. At the moment, she is the art director of the websites fpmeyer.com and museodemujeres.com and she is part of the editorial team of zonezero.com. You can see her work at: elisarugo.proAlfredo Esparza

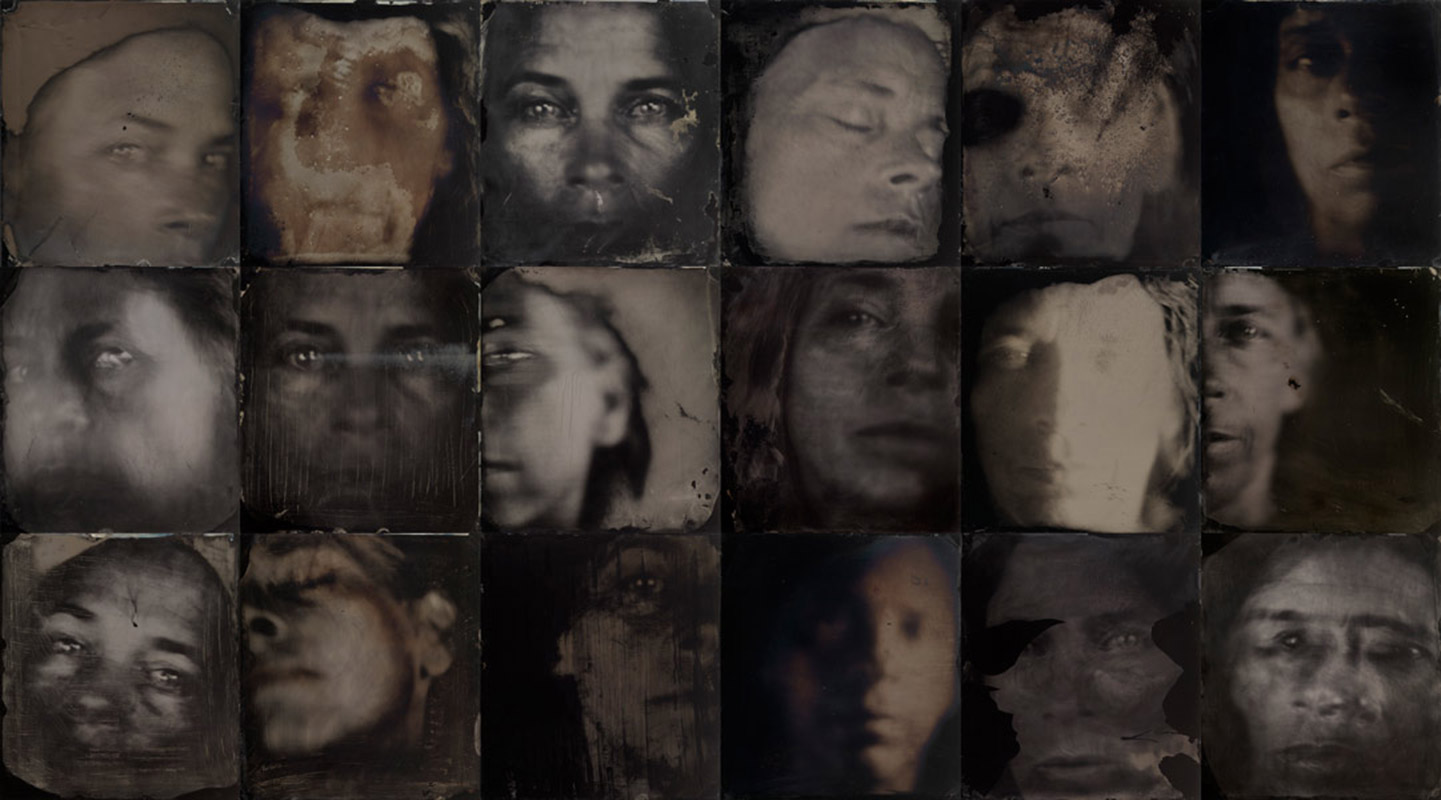

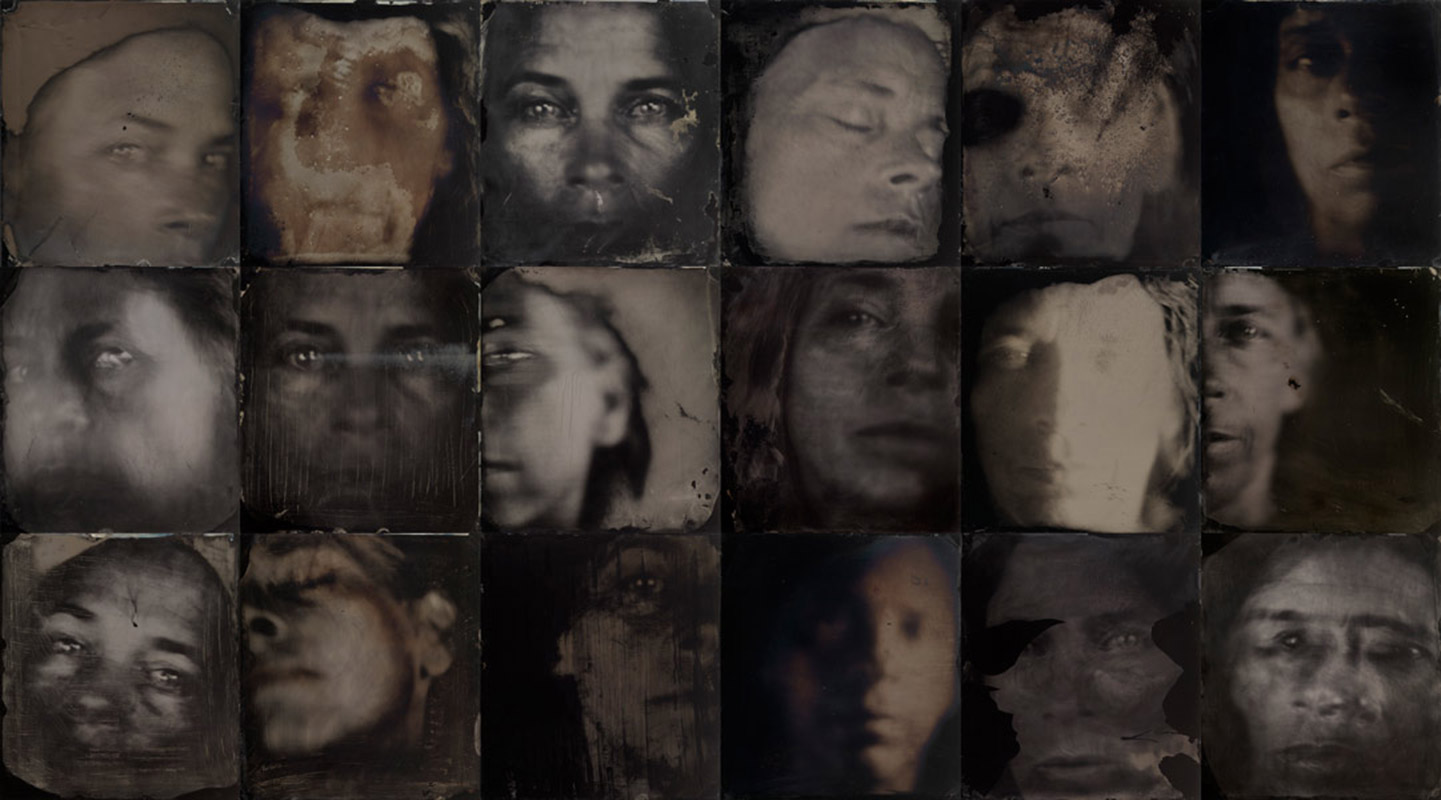

450 videoportraits made with cell phone

Since people daily have to travel long distances in Mexico City to get from home to work or school and then coming back, subway users employ this medium as a temporary extension of their homes, where they can claim as much privacy and intimacy they need; even when the metro is overcrowded.

Just to win a few minutes a day, travellers keep their minds off from what happens in the carriage during the trip by chatting with their companion, finishing pending work, resting, or having a moment of introspection.

What really matters is that the journey enables travellers to do more than simply move from one place to another, not only by the urge of snatching time in a city where traveling takes so long, but also to take the opportunity to spare some time for oneself.

| videoportrait #32 | videoportrait #41 | videoportrait #56 |

| videoportrait #123 | videoportrait #197 | videoportrait #201 |

| videoportrait #222 | videoportrait #262 | videoportrait #297 |

| videoportrait #360 | videoportrait #363 | videoportrait #375 |

| videoportrait #395 | videoportrait #412 | videoportrait #343 |

| videoportrait #356 | videoportrait #272 | videoportrait #323 |

Alfredo Esparza (Torreon, Mexico. 1980) Visual artist. Uses photography and video as main tools to produce his pieces. He had solo exhibitions in Torreon and Mexico City, and many group shows In US, Italy, Spain and Mexico. Most of his work deals with the tension generated by the interaction between strangers in public or private spaces. His work has been published in magazines such as Vice, Cuartoscuro and Xoo. From 2012 to 2014 he worked as head of exhibitions and resident curator and museographer at the Museo Nacional de Culturas Populares, in Mexico City. He also produced independent exhibitions for both private and public institutions in Mexico City. Since 2012, he is associated curator at .357 Gallery, in Mexico City. Lives and works between Torreon and Mexico City.

Alfredo Esparza (Torreon, Mexico. 1980) Visual artist. Uses photography and video as main tools to produce his pieces. He had solo exhibitions in Torreon and Mexico City, and many group shows In US, Italy, Spain and Mexico. Most of his work deals with the tension generated by the interaction between strangers in public or private spaces. His work has been published in magazines such as Vice, Cuartoscuro and Xoo. From 2012 to 2014 he worked as head of exhibitions and resident curator and museographer at the Museo Nacional de Culturas Populares, in Mexico City. He also produced independent exhibitions for both private and public institutions in Mexico City. Since 2012, he is associated curator at .357 Gallery, in Mexico City. Lives and works between Torreon and Mexico City.450 videoportraits made with cell phone

Since people daily have to travel long distances in Mexico City to get from home to work or school and then coming back, subway users employ this medium as a temporary extension of their homes, where they can claim as much privacy and intimacy they need; even when the metro is overcrowded.

Just to win a few minutes a day, travellers keep their minds off from what happens in the carriage during the trip by chatting with their companion, finishing pending work, resting, or having a moment of introspection.

What really matters is that the journey enables travellers to do more than simply move from one place to another, not only by the urge of snatching time in a city where traveling takes so long, but also to take the opportunity to spare some time for oneself.

| videoportrait #32 | videoportrait #41 | videoportrait #56 |

| videoportrait #123 | videoportrait #197 | videoportrait #201 |

| videoportrait #222 | videoportrait #262 | videoportrait #297 |

| videoportrait #360 | videoportrait #363 | videoportrait #375 |

| videoportrait #395 | videoportrait #412 | videoportrait #343 |

| videoportrait #356 | videoportrait #272 | videoportrait #323 |

Alfredo Esparza (Torreon, Mexico. 1980) Visual artist. Uses photography and video as main tools to produce his pieces. He had solo exhibitions in Torreon and Mexico City, and many group shows In US, Italy, Spain and Mexico. Most of his work deals with the tension generated by the interaction between strangers in public or private spaces. His work has been published in magazines such as Vice, Cuartoscuro and Xoo. From 2012 to 2014 he worked as head of exhibitions and resident curator and museographer at the Museo Nacional de Culturas Populares, in Mexico City. He also produced independent exhibitions for both private and public institutions in Mexico City. Since 2012, he is associated curator at .357 Gallery, in Mexico City. Lives and works between Torreon and Mexico City.

Alfredo Esparza (Torreon, Mexico. 1980) Visual artist. Uses photography and video as main tools to produce his pieces. He had solo exhibitions in Torreon and Mexico City, and many group shows In US, Italy, Spain and Mexico. Most of his work deals with the tension generated by the interaction between strangers in public or private spaces. His work has been published in magazines such as Vice, Cuartoscuro and Xoo. From 2012 to 2014 he worked as head of exhibitions and resident curator and museographer at the Museo Nacional de Culturas Populares, in Mexico City. He also produced independent exhibitions for both private and public institutions in Mexico City. Since 2012, he is associated curator at .357 Gallery, in Mexico City. Lives and works between Torreon and Mexico City.ZoneZero

Geography of Pain is meant to be a virtual geographical space where the user or visitor can take a tour through different regions of Mexico and can listen to various stories about the events that overwhelmed not only the institutional and political system but also the authorities and the citizens of this country; stories about people who lost their lives, people who went missing.

This web documentary exists thanks to the convergence of documentary film with the interactivity that the new digital media offers. Audiovisual language was mixed with programming language and resulted in new interactive ways of storytelling, namely, the interactive documentary. In this way, this project uses a clear and a direct narrative that allows the viewer to understand the experience of insecurity in Mexico and the cases of missing persons.

Mónica González. Photographer. She studied in UNAM (Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México) at the Political and Sociological Sciences Faculty, the major in Communication Sciences and Journalism. She has worked for the Expansión Magazine, The Dallas Morning News, Newsweek Magazine, Nike, HBO Project 48, NOTIMEX, El Economista newspaper, El Centro journal, VICE Mexico, NFB Canada and currently working as a photographer for the Milenio journal. She won the student grant Jóvenes Creativos (Creative Youth) 2009-2010 given by FONCA CONACULTA due to her project El sentido anatómico (The Anatomic Sense), transsexuality, the new nuclear family. She received the National Journalism Award in 2006 under the category of Photography due to her Migration Coverage of Mexicans in the border of Altar – Sasabe, Sonora, through Arizona’s desert. And in 2011 for her documentary work Geografía del Dolor (Geography of Pain)

Mónica González. Photographer. She studied in UNAM (Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México) at the Political and Sociological Sciences Faculty, the major in Communication Sciences and Journalism. She has worked for the Expansión Magazine, The Dallas Morning News, Newsweek Magazine, Nike, HBO Project 48, NOTIMEX, El Economista newspaper, El Centro journal, VICE Mexico, NFB Canada and currently working as a photographer for the Milenio journal. She won the student grant Jóvenes Creativos (Creative Youth) 2009-2010 given by FONCA CONACULTA due to her project El sentido anatómico (The Anatomic Sense), transsexuality, the new nuclear family. She received the National Journalism Award in 2006 under the category of Photography due to her Migration Coverage of Mexicans in the border of Altar – Sasabe, Sonora, through Arizona’s desert. And in 2011 for her documentary work Geografía del Dolor (Geography of Pain)Geography of Pain is meant to be a virtual geographical space where the user or visitor can take a tour through different regions of Mexico and can listen to various stories about the events that overwhelmed not only the institutional and political system but also the authorities and the citizens of this country; stories about people who lost their lives, people who went missing.

This web documentary exists thanks to the convergence of documentary film with the interactivity that the new digital media offers. Audiovisual language was mixed with programming language and resulted in new interactive ways of storytelling, namely, the interactive documentary. In this way, this project uses a clear and a direct narrative that allows the viewer to understand the experience of insecurity in Mexico and the cases of missing persons.

Mónica González. Photographer. She studied in UNAM (Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México) at the Political and Sociological Sciences Faculty, the major in Communication Sciences and Journalism. She has worked for the Expansión Magazine, The Dallas Morning News, Newsweek Magazine, Nike, HBO Project 48, NOTIMEX, El Economista newspaper, El Centro journal, VICE Mexico, NFB Canada and currently working as a photographer for the Milenio journal. She won the student grant Jóvenes Creativos (Creative Youth) 2009-2010 given by FONCA CONACULTA due to her project El sentido anatómico (The Anatomic Sense), transsexuality, the new nuclear family. She received the National Journalism Award in 2006 under the category of Photography due to her Migration Coverage of Mexicans in the border of Altar – Sasabe, Sonora, through Arizona’s desert. And in 2011 for her documentary work Geografía del Dolor (Geography of Pain)

Mónica González. Photographer. She studied in UNAM (Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México) at the Political and Sociological Sciences Faculty, the major in Communication Sciences and Journalism. She has worked for the Expansión Magazine, The Dallas Morning News, Newsweek Magazine, Nike, HBO Project 48, NOTIMEX, El Economista newspaper, El Centro journal, VICE Mexico, NFB Canada and currently working as a photographer for the Milenio journal. She won the student grant Jóvenes Creativos (Creative Youth) 2009-2010 given by FONCA CONACULTA due to her project El sentido anatómico (The Anatomic Sense), transsexuality, the new nuclear family. She received the National Journalism Award in 2006 under the category of Photography due to her Migration Coverage of Mexicans in the border of Altar – Sasabe, Sonora, through Arizona’s desert. And in 2011 for her documentary work Geografía del Dolor (Geography of Pain)Alejandro Malo

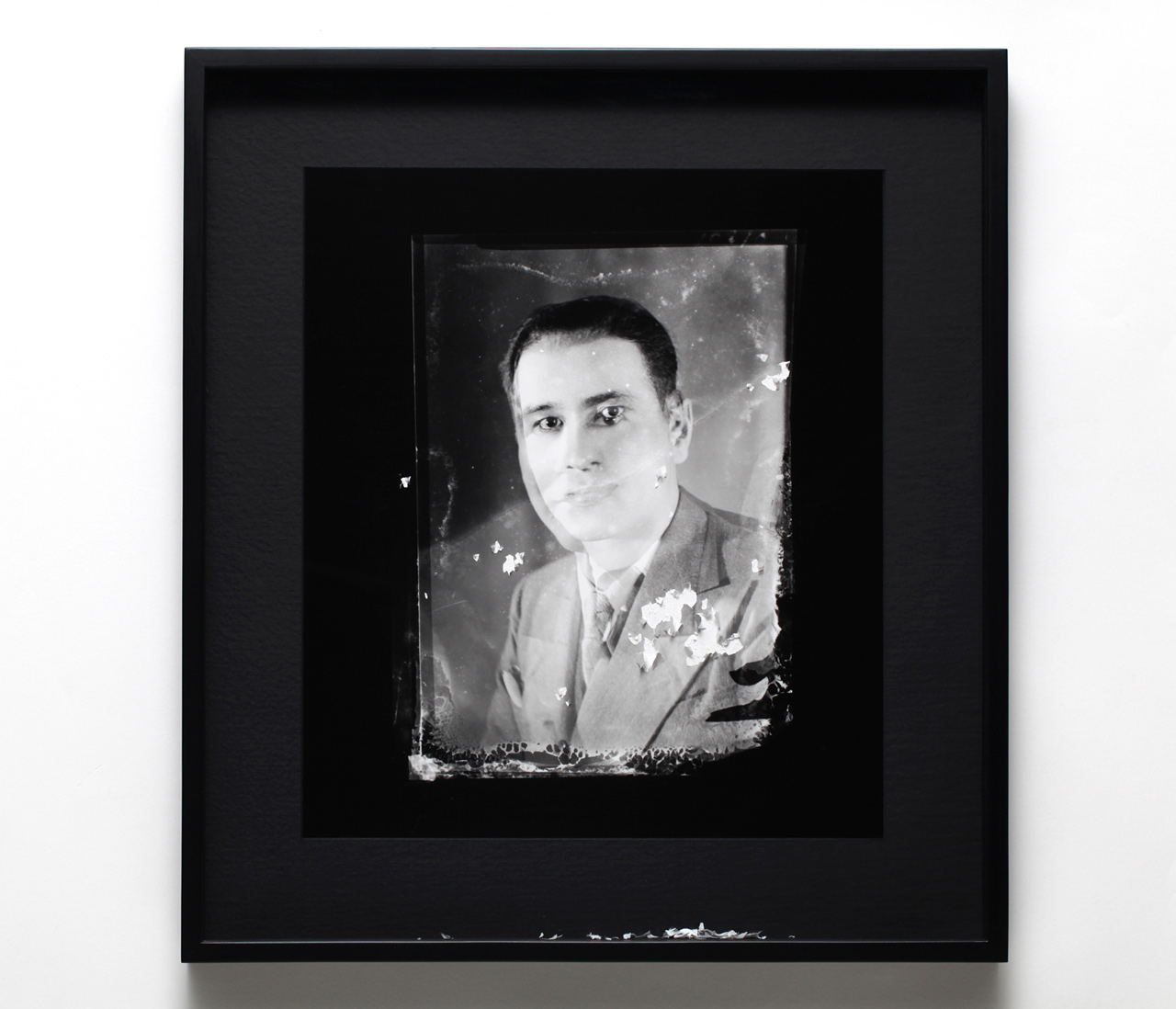

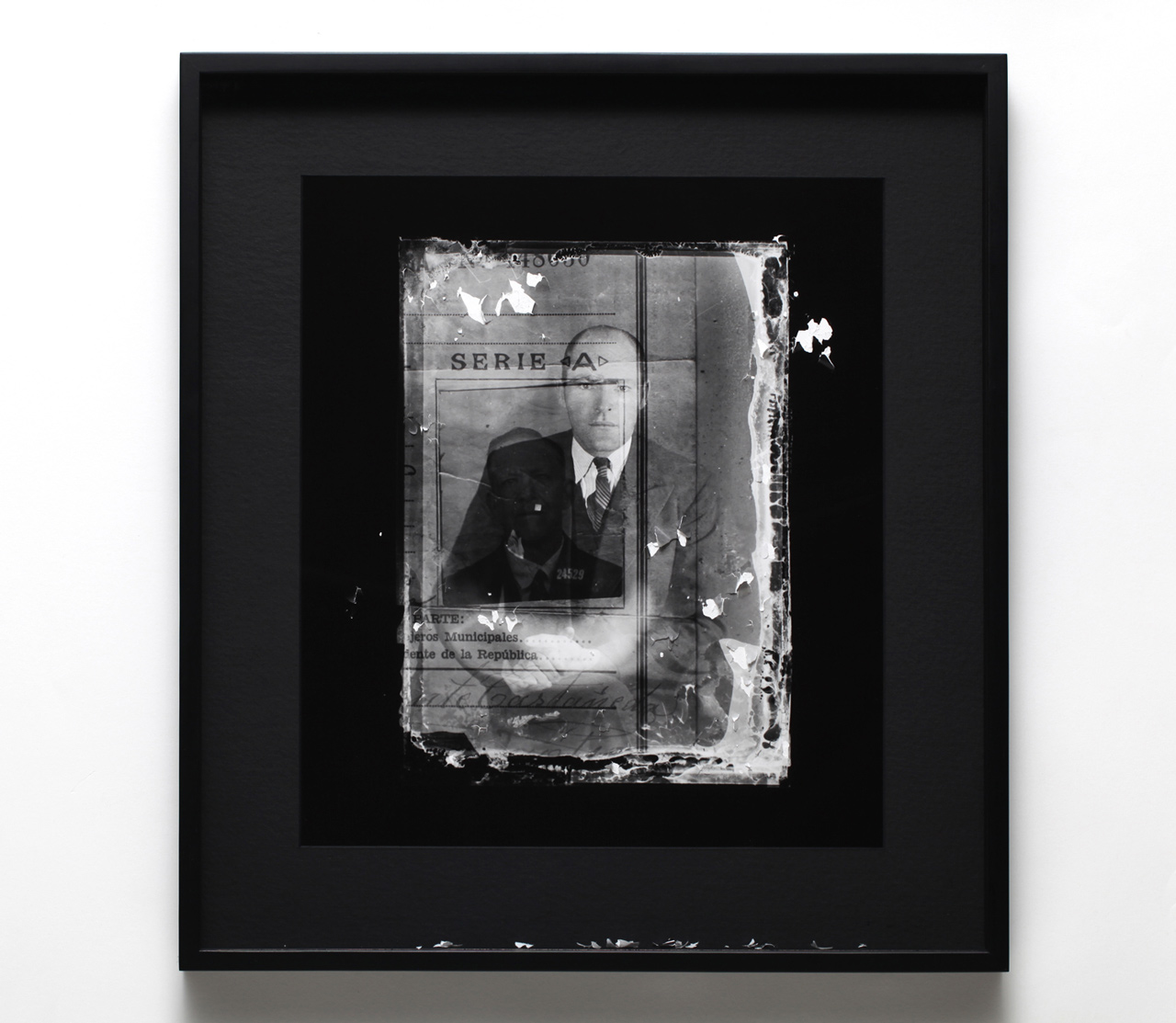

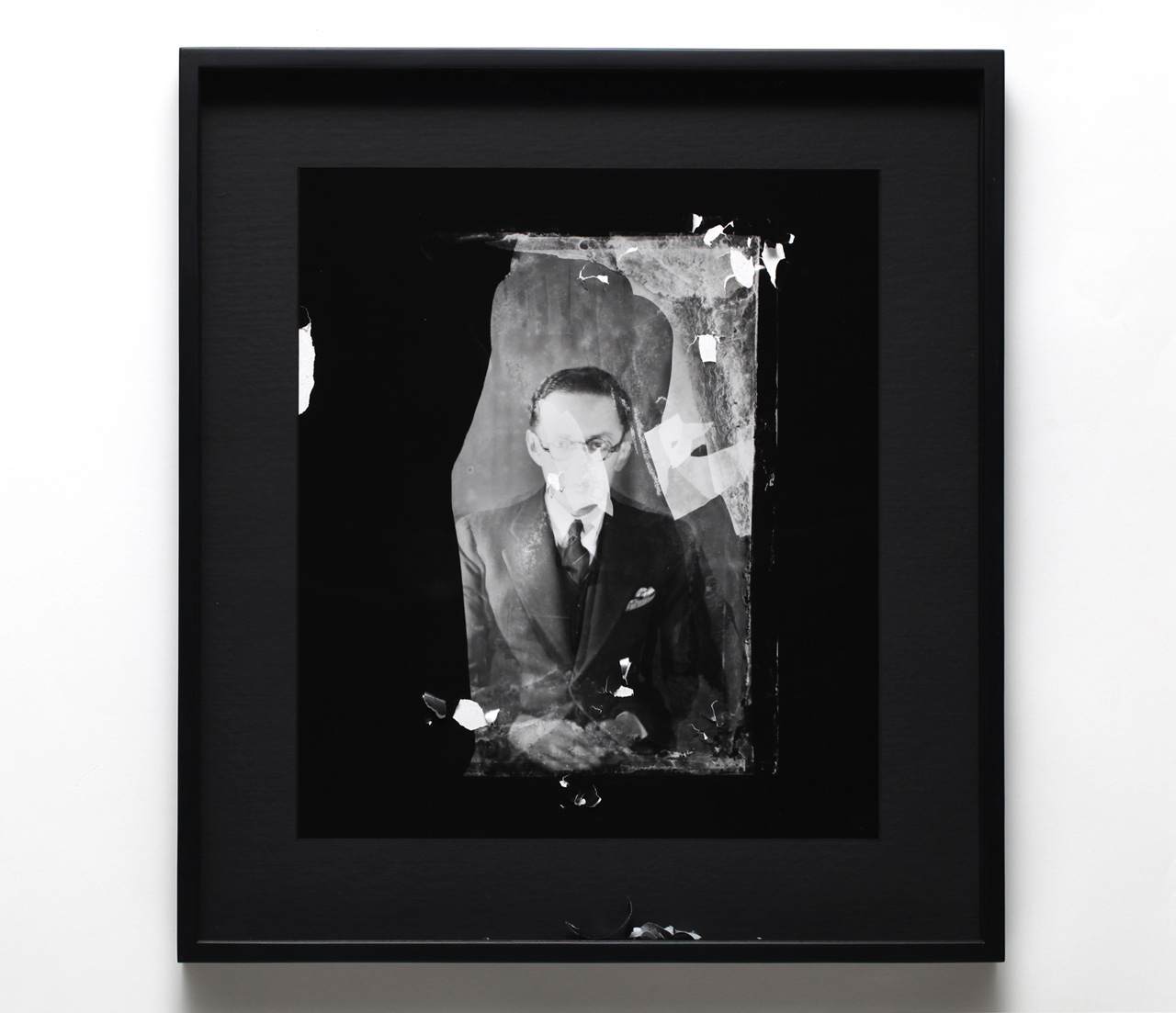

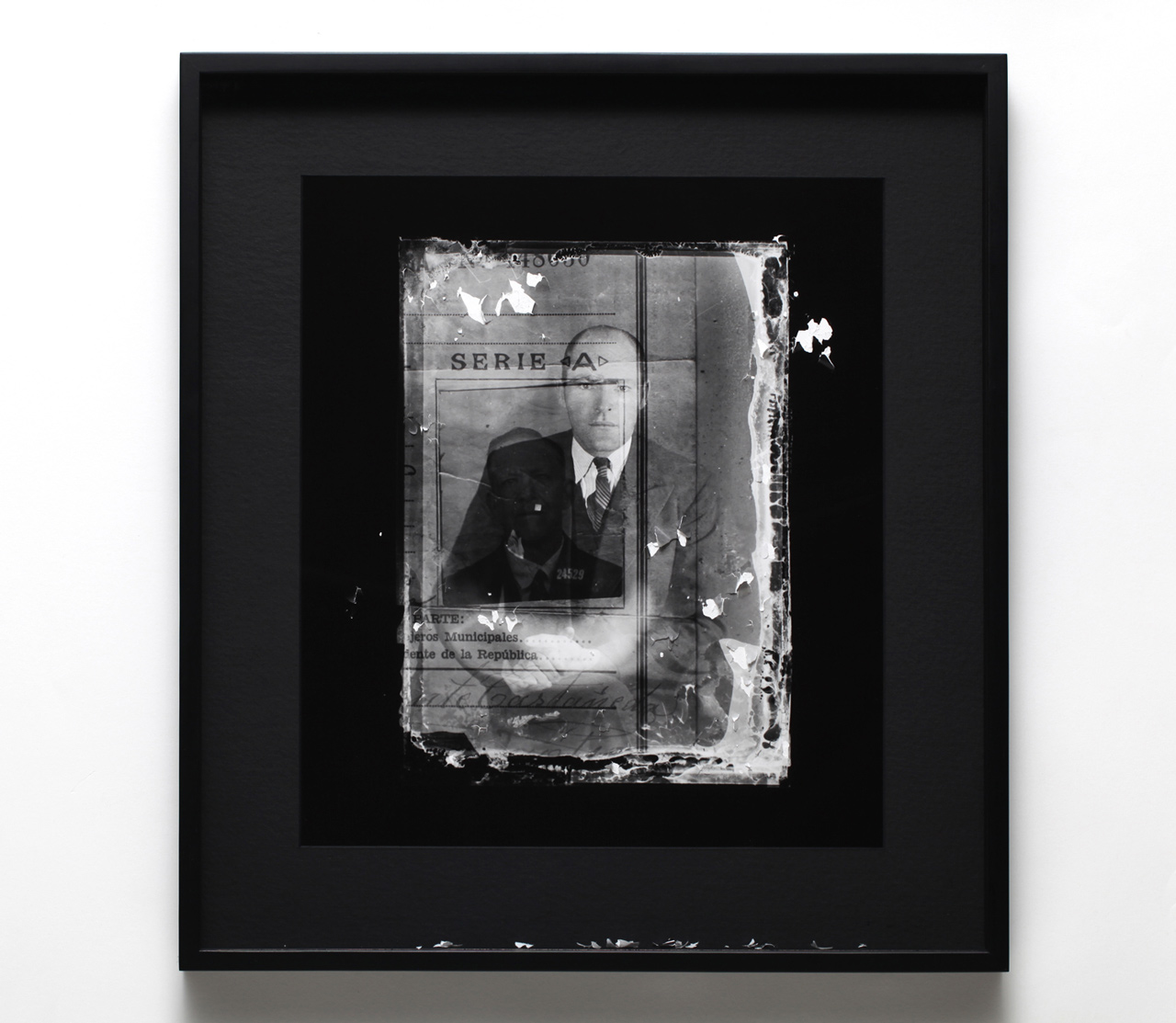

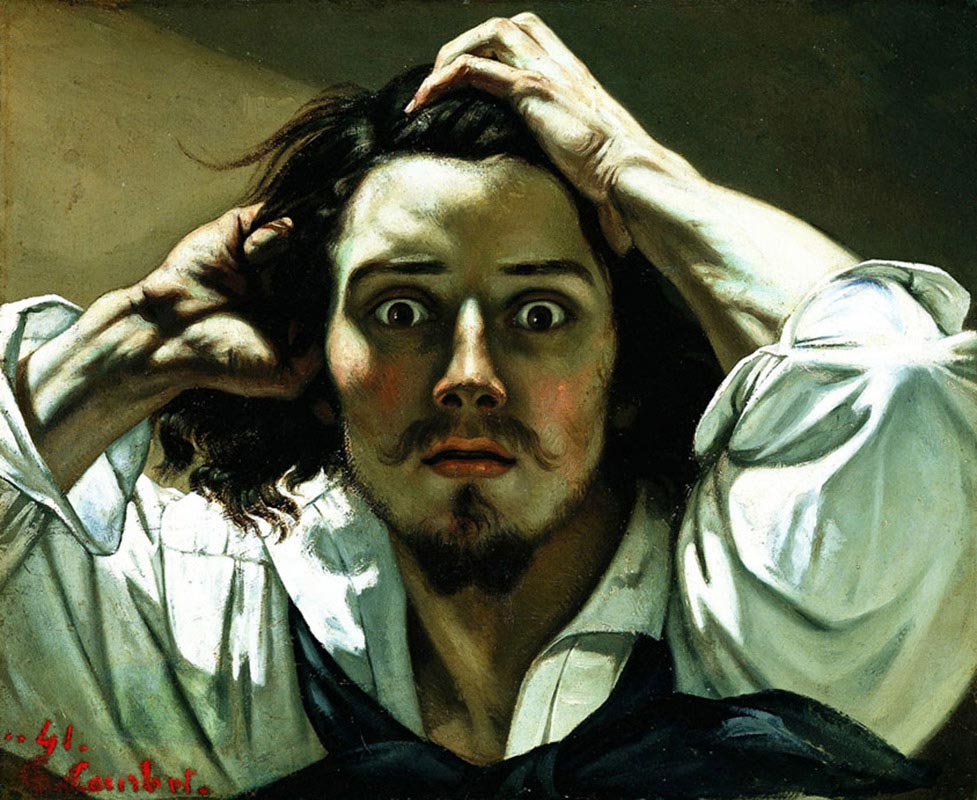

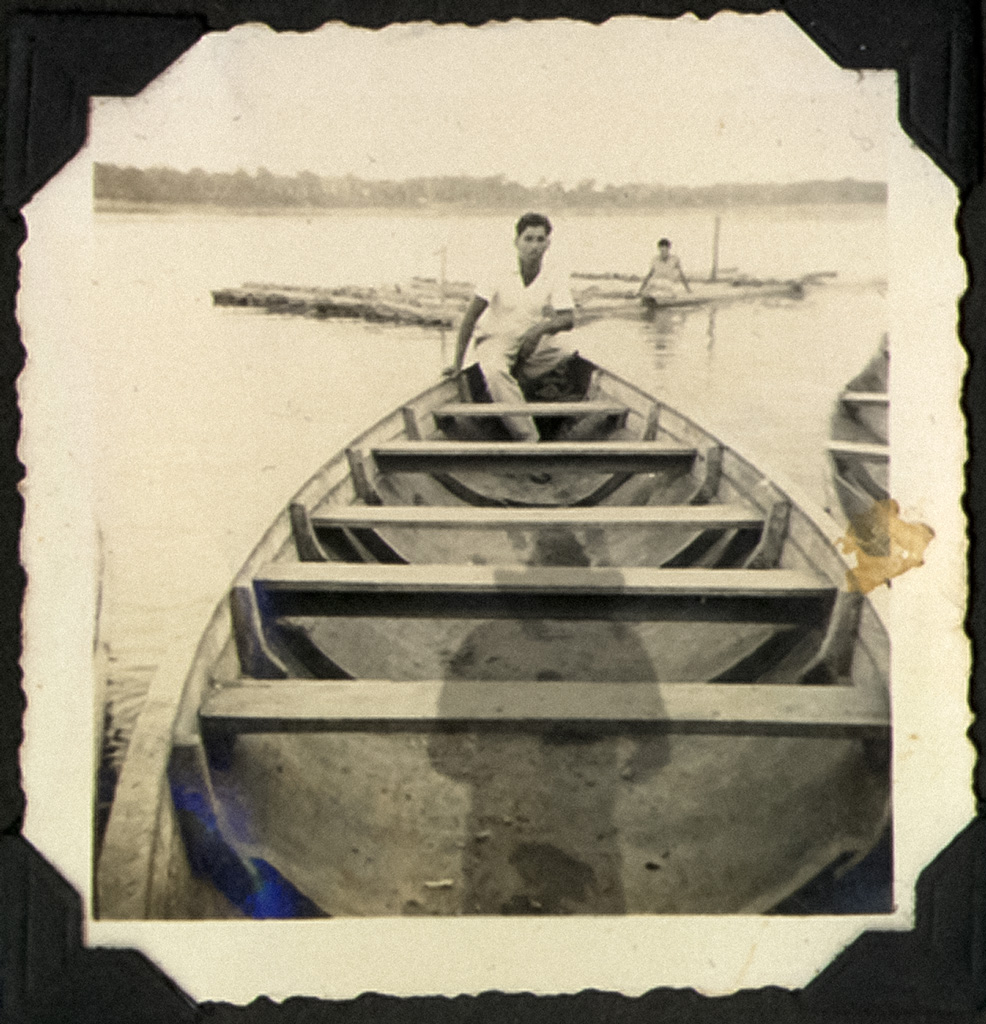

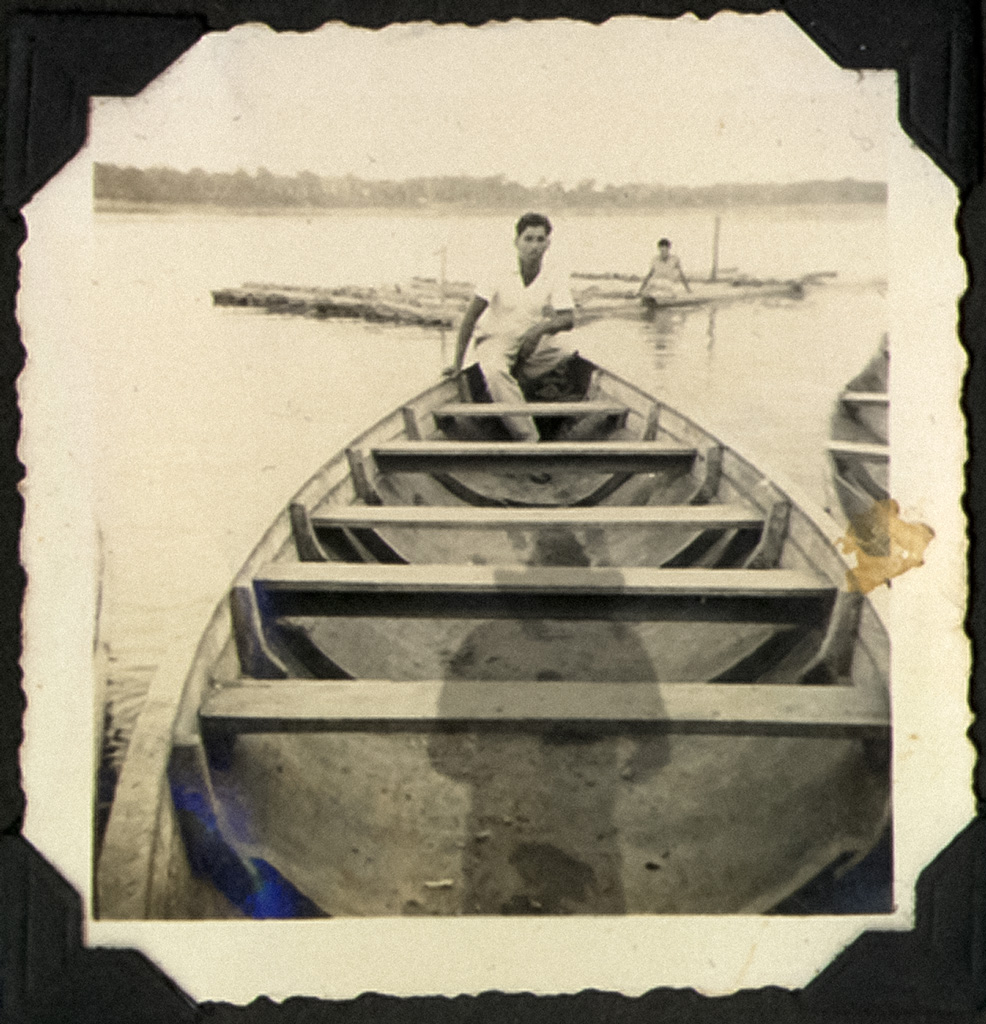

Mexican Family, unknown author, daguerrotype, ca. 1847

Seeing presupposes distance, decisiveness which separates, the power to stay out of contact and in contact avoid confusion.

Seeing means that this separation has nevertheless become an encounter. —Maurice Blanchot.

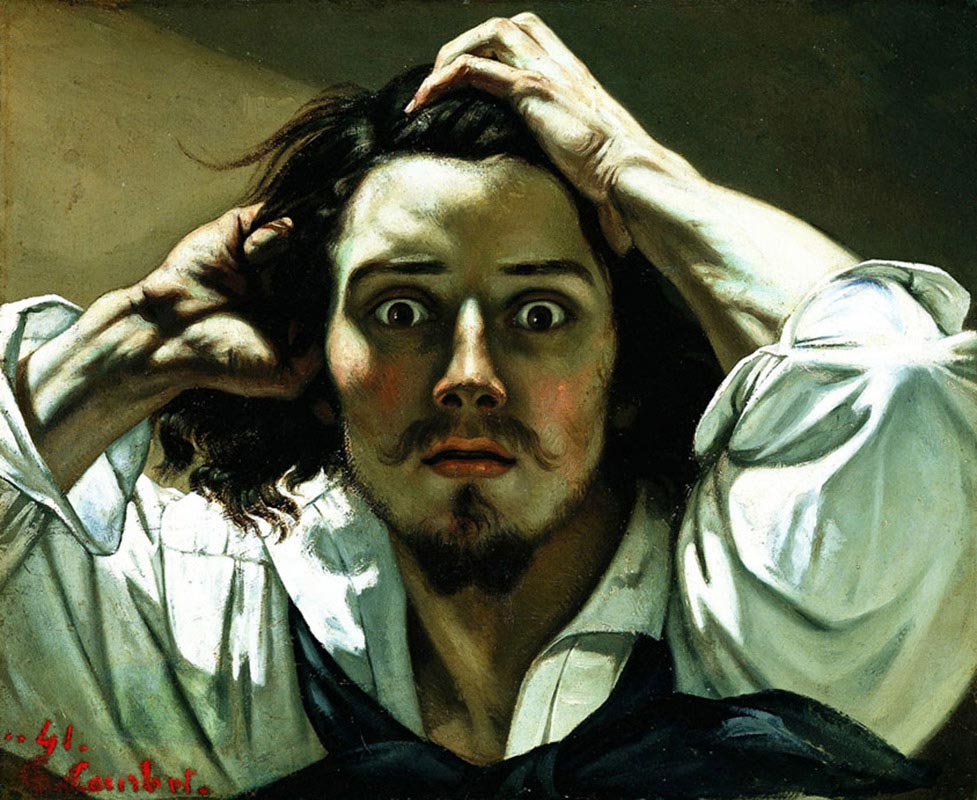

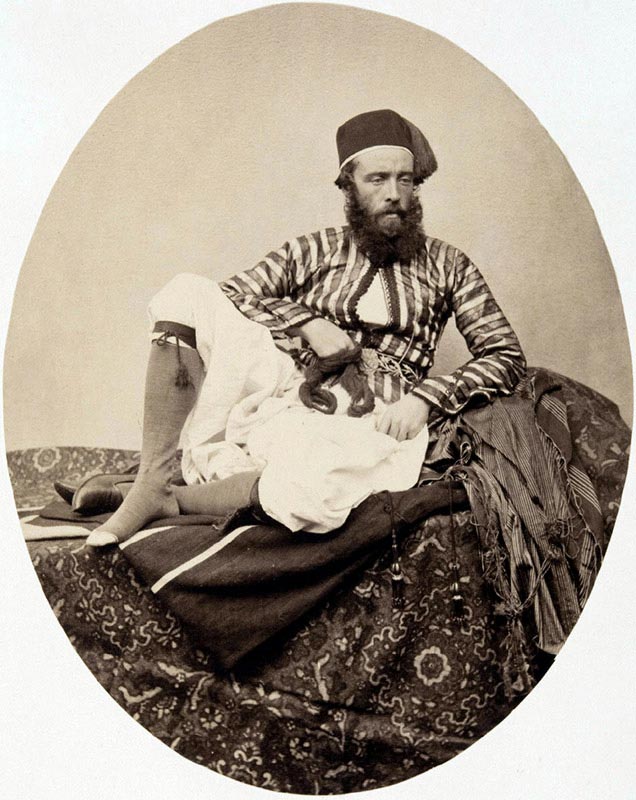

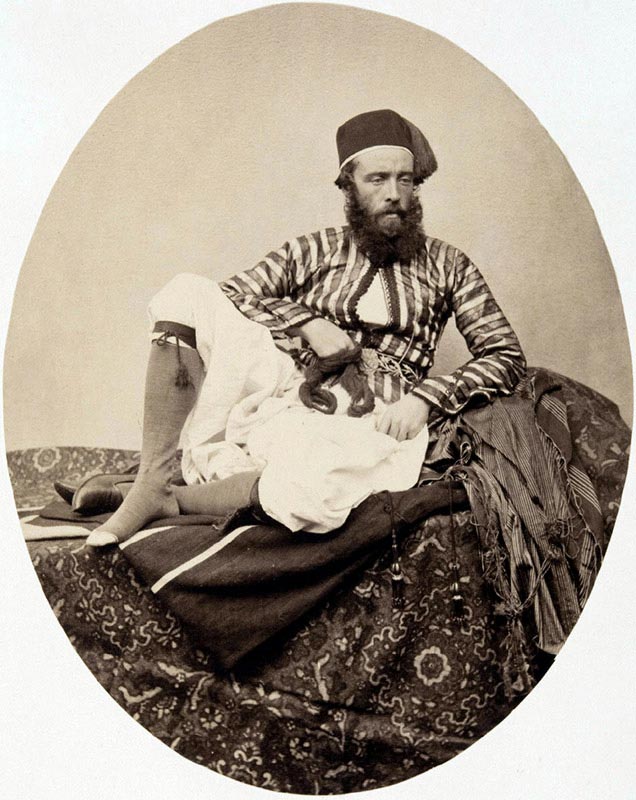

Any representation of a community implies a perspective. Each time we observe a group we become interpreters and with each observation we make, we reveal to which communities we belong. Photography, with its ability to record, was soon considered to be a suitable tool to crystallize these observations and encourage the study of ethnicity and customs. However, being at least as susceptible to ideological bias as any other medium, it immediately revealed its colonialist burden and it is no coincidence that some of the first photographs that try to document a community were taken in company of an army or along trade routes. Images of the Mexico-American War (1846-1848) and the rebellion in India (1857), for example, show the confusion of these early records in the eyes of those portrayed and often leave us with the feeling that those photos were another kind of victory.

In the last decade of the nineteenth century, Ryuzo Torii and Edward S. Curtis introduce a way of using photography on behalf of ethnology, and Jacob Riis published How the Other Half Lives (1890). In those early photo essays on specific communities, there's a clear awareness of the otherness and a sympathetic point of view, but the perspective of the victors or the moral superiority of the observer is also legitimated. That partly naive, partly pretentious attitude of someone assuming to discover or save the others, has permeated much of photojournalism and documentary work since. Arguing a never achieved objectivity, they perpetuated asymmetrical readings and promoted a colonialism that replaced war's firepower with economy and culture. There were reasons for its existence, as an expression of a particular moment in history and a contribution to global integration, but it has been overtaken by a world whose visual center moves across the surface of the globe and where the last word has the duration of a tweet.

Soon documentalists themselves perceived the contradiction and near the beginning of the twentieth century started to explore alternatives to escape this logic: from the numerous attempts to capture the misleading truth in the style of Dziga Vertov's Kino-Pravda, through Cinema Verite, Direct Cinema, Candid Eye in film and their photographic counterparts, all the way to ethnofiction experiments, the long history of participatory documentary or the hopeful outlook of Shahidul Alam's Majority World, which proposes to let those closer to the phenomena and activities hold the camera. All are useful tools to approach the topic, but they don’t offer a final answer.

An image has the chance, as never before, to represent each ethnic, social and tribal group, whether they live in the cities or the most remote regions, and it also has the potential to do so from many different angles. The camera, already present in many devices, is in the hands of almost anyone who wants to register their community. Maybe it’s time to accept once and for all that to represent a community is not to search an objective representation or an intrinsic truth, nor trying to offer a problematic balance. However, in any case we should try to give a fair interpretation and an accurate testimony, where in many cases the sum of multiple perspectives can bring us closer to an elusive reality. This requires more critical reading and analysis from the public, compels the media to hold stronger values than empty veracity and offers the photographer a more honest path to meet the others. This change, like any change, is full of uncertainties, but ends in a space full of opportunities where the image can lead us.

Alejandro Malo (Mexico, 1972). Lives and works in Mexico and is the director of ZoneZero. Since 1993, he has taken part in various cultural projects and worked as an information technology consultant. He has collaborated in print and electronic publications, and given workshops and conferences on literature, creative writing, storytelling and technology. In 2009, Malo joined the team of the Fundación Pedro Meyer, where he directs the Archives and Technology departments.

Alejandro Malo (Mexico, 1972). Lives and works in Mexico and is the director of ZoneZero. Since 1993, he has taken part in various cultural projects and worked as an information technology consultant. He has collaborated in print and electronic publications, and given workshops and conferences on literature, creative writing, storytelling and technology. In 2009, Malo joined the team of the Fundación Pedro Meyer, where he directs the Archives and Technology departments.

Mexican Family, unknown author, daguerrotype, ca. 1847

Seeing presupposes distance, decisiveness which separates, the power to stay out of contact and in contact avoid confusion.

Seeing means that this separation has nevertheless become an encounter. —Maurice Blanchot.

Any representation of a community implies a perspective. Each time we observe a group we become interpreters and with each observation we make, we reveal to which communities we belong. Photography, with its ability to record, was soon considered to be a suitable tool to crystallize these observations and encourage the study of ethnicity and customs. However, being at least as susceptible to ideological bias as any other medium, it immediately revealed its colonialist burden and it is no coincidence that some of the first photographs that try to document a community were taken in company of an army or along trade routes. Images of the Mexico-American War (1846-1848) and the rebellion in India (1857), for example, show the confusion of these early records in the eyes of those portrayed and often leave us with the feeling that those photos were another kind of victory.

In the last decade of the nineteenth century, Ryuzo Torii and Edward S. Curtis introduce a way of using photography on behalf of ethnology, and Jacob Riis published How the Other Half Lives (1890). In those early photo essays on specific communities, there's a clear awareness of the otherness and a sympathetic point of view, but the perspective of the victors or the moral superiority of the observer is also legitimated. That partly naive, partly pretentious attitude of someone assuming to discover or save the others, has permeated much of photojournalism and documentary work since. Arguing a never achieved objectivity, they perpetuated asymmetrical readings and promoted a colonialism that replaced war's firepower with economy and culture. There were reasons for its existence, as an expression of a particular moment in history and a contribution to global integration, but it has been overtaken by a world whose visual center moves across the surface of the globe and where the last word has the duration of a tweet.

Soon documentalists themselves perceived the contradiction and near the beginning of the twentieth century started to explore alternatives to escape this logic: from the numerous attempts to capture the misleading truth in the style of Dziga Vertov's Kino-Pravda, through Cinema Verite, Direct Cinema, Candid Eye in film and their photographic counterparts, all the way to ethnofiction experiments, the long history of participatory documentary or the hopeful outlook of Shahidul Alam's Majority World, which proposes to let those closer to the phenomena and activities hold the camera. All are useful tools to approach the topic, but they don’t offer a final answer.

An image has the chance, as never before, to represent each ethnic, social and tribal group, whether they live in the cities or the most remote regions, and it also has the potential to do so from many different angles. The camera, already present in many devices, is in the hands of almost anyone who wants to register their community. Maybe it’s time to accept once and for all that to represent a community is not to search an objective representation or an intrinsic truth, nor trying to offer a problematic balance. However, in any case we should try to give a fair interpretation and an accurate testimony, where in many cases the sum of multiple perspectives can bring us closer to an elusive reality. This requires more critical reading and analysis from the public, compels the media to hold stronger values than empty veracity and offers the photographer a more honest path to meet the others. This change, like any change, is full of uncertainties, but ends in a space full of opportunities where the image can lead us.

Alejandro Malo (Mexico, 1972). Lives and works in Mexico and is the director of ZoneZero. Since 1993, he has taken part in various cultural projects and worked as an information technology consultant. He has collaborated in print and electronic publications, and given workshops and conferences on literature, creative writing, storytelling and technology. In 2009, Malo joined the team of the Fundación Pedro Meyer, where he directs the Archives and Technology departments.