Seeing stories

Photography in the land of narrative

The Devil in New York. 1985. Pedro Meyer

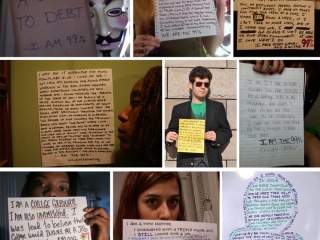

In 2013, just over one billion smart phones came onto the international market, while only a little over sixty million digital cameras sold. Thanks to this push, the number of cameras sold as part of mobile devices will be greater than the number of people inhabiting the planet, which accentuates the visual avalanche we now face. Creating photographic images has become as trivial as chatting on the phone and their meaning, 2,000 millones de nuevasimágenes as they are uploaded and shared online every day is reduced, in many cases, to anecdotal scenes that are incomprehensible to strangers. In the face of this extensive iconographic universe, content runs the risk of being lost, of being confused amidst stylistic similarities, of sinking unceremoniously into the cracks of global networks; and one of the few useful tools for strengthening photographic discourse and emphasizing a relevant visual message is narrative.

Four years ago, in 2010, when ZoneZero's position within the ecosystem of projects at the Pedro Meyer Foundation was only just beginning to be defined, World Press Photo contacted us. They had interviewed a number of people and institutions from the field of photography in Mexico and were looking to define alternative forms of collaboration. Their goal was to develop an educational program designed for photojournalists. Our first exchanges created several points of tension, but each debate served to consolidate points of agreement. These points grew from reflections that are still meaningful today.

The first was a diagnosis that was already evident at that point: the traditional role of photography could not continue unchanged in an environment where the sources of photographic material were multiplied at an unattainable pace. Capturing the exact photograph of an event had become a game of chance that could be won by anyone in possession of a mobile device. Originality paled in the face of quantity and mastery of technique dissipated with each technological advance. The very boundaries of photography we being blurred: the place for photography within interactive media, video, electronic books, websites and more, the relationship between these and other media, the frontier of the curatorial and author-oriented, all became territory for exploration. At that moment we chose to broach the concept of New Media, to emphasize our willingness to experiment with the sum of diverse technological resources, and for lack of another label with the same amount of breadth and flexibility for what we wanted to achieve.

The second reflection identified which tool could be useful both for photojournalists and the wider public that was already engaging in the educational activities at the Pedro Meyer Foundation and adhered to ZoneZero content. The choice was clear and conclusive: storytelling. After being translated, the term was replaced with a new one, photo-narrative, to highlight the photographic component. Pedro Meyer’s story I Photograph to Remember with one of the cornerstones of Digital Storytelling, and his position that everything before a photographer tells a story, were influential in this choice. Nevertheless, it was equally or more important to consider that in an era where images and information are as abundant and immediate as they are now, context is the only thing that distinguishes them from background noise. Every image, in order to be more than ornamental, invites the viewer to interpret a meaning, to head in some direction, to guess the story and imagine the consequences of what it represents. Every memorable photo tells a story, whether in the tension of the elements it depicts, or in how it has been edited, or with the help of accompanying information. Whether it is a single photo, a series, images in movement or interactive formats, an image aspires to be coherent, to suggest a before and an after, to propose or explain change. We are not the same after the party or the childhood accident documented by the photograph, nor after national disaster or glory.

Today, after a number of years collaborating with World Press Photo, three editions of Diplomado de Fotonarrativa y Nuevos Medios and a plethora of technological changes that could only have been imagined, photo-narrative is even more important. During this time we have learned and changed. Our ideas about photography and narrative continue to change. World Press Photo now has multimedia categories that include long feature, short feature and interactive documentary. Photo-narrative’s effectiveness means that it has been used in a number of different fields. Because of this, it is also our task to explore and exhibit examples that, as with other issues, foster dialogue and reflection. Every one of us is the sum of our personal, familiar, collective and even fictional stories. Being understood and understanding one another begins with knowing how to tell these stories.

Alejandro Malo (Mexico, 1972). Lives and works in Mexico and is the director of ZoneZero. Since 1993, he has taken part in various cultural projects and worked as an information technology consultant. He has collaborated in print and electronic publications, and given workshops and conferences on literature, creative writing, storytelling and technology. In 2009, Malo joined the team of the Fundación Pedro Meyer, where he directs the Archives and Technology departments.

Alejandro Malo (Mexico, 1972). Lives and works in Mexico and is the director of ZoneZero. Since 1993, he has taken part in various cultural projects and worked as an information technology consultant. He has collaborated in print and electronic publications, and given workshops and conferences on literature, creative writing, storytelling and technology. In 2009, Malo joined the team of the Fundación Pedro Meyer, where he directs the Archives and Technology departments.