Xtabay Alderete

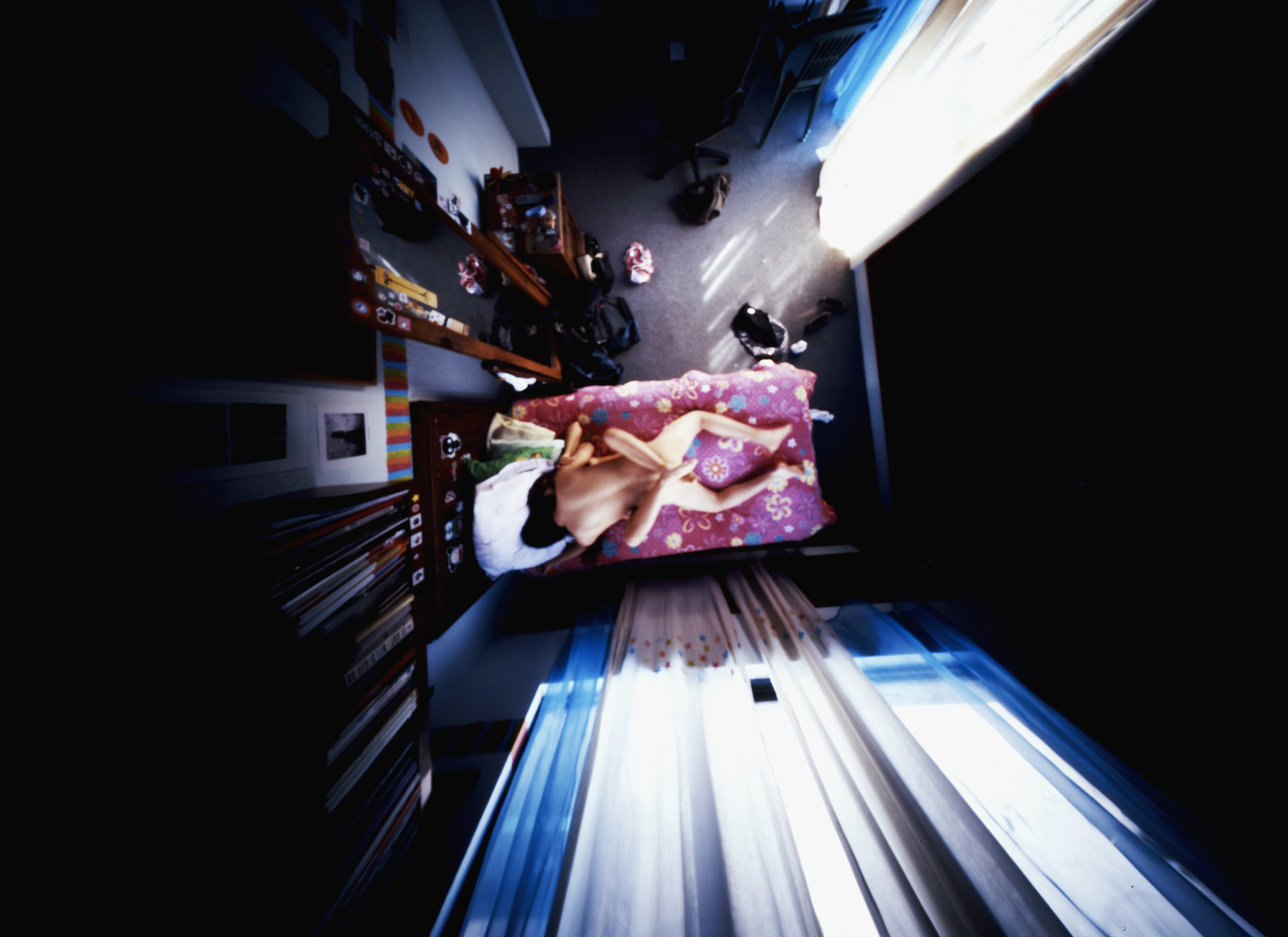

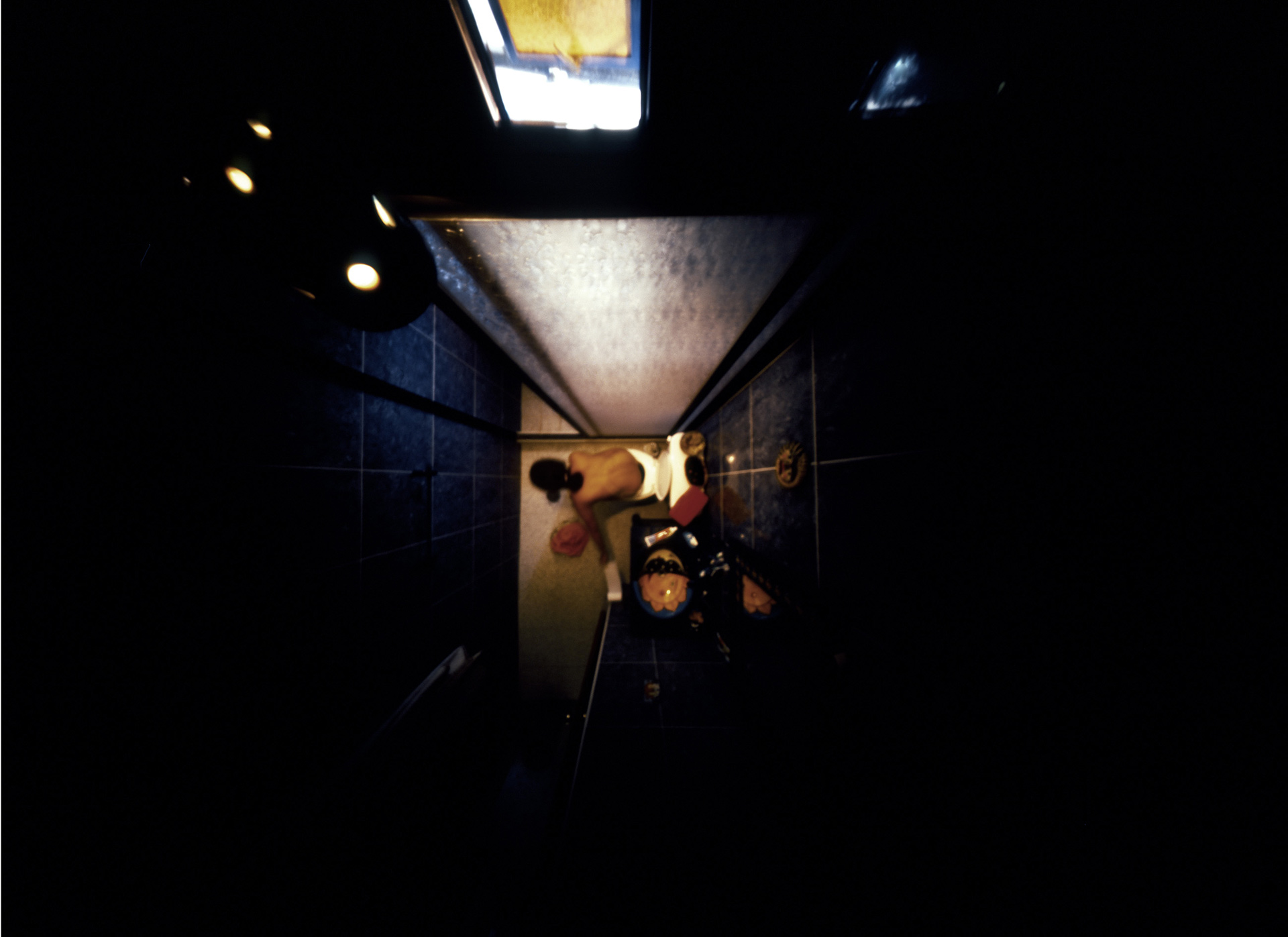

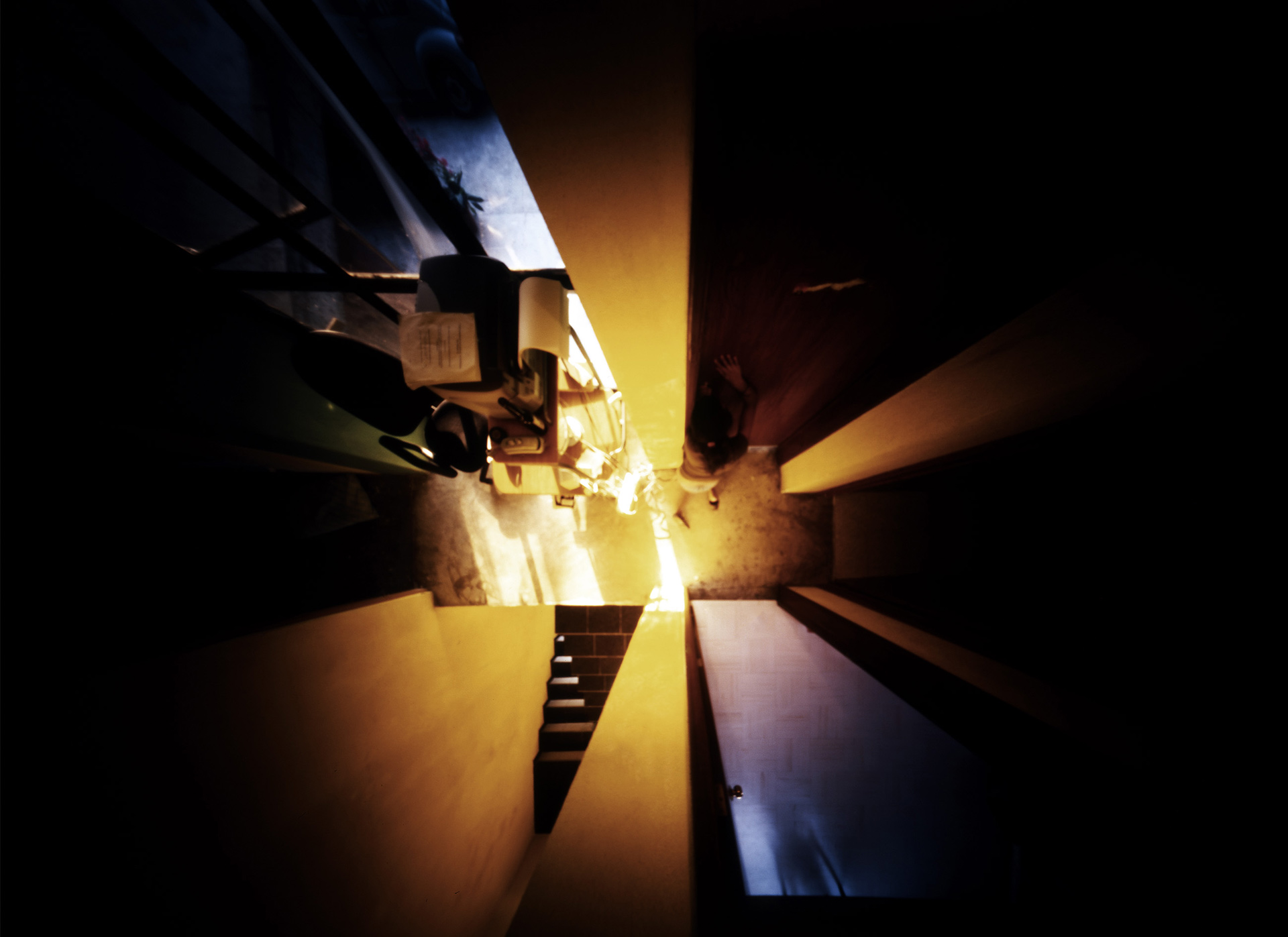

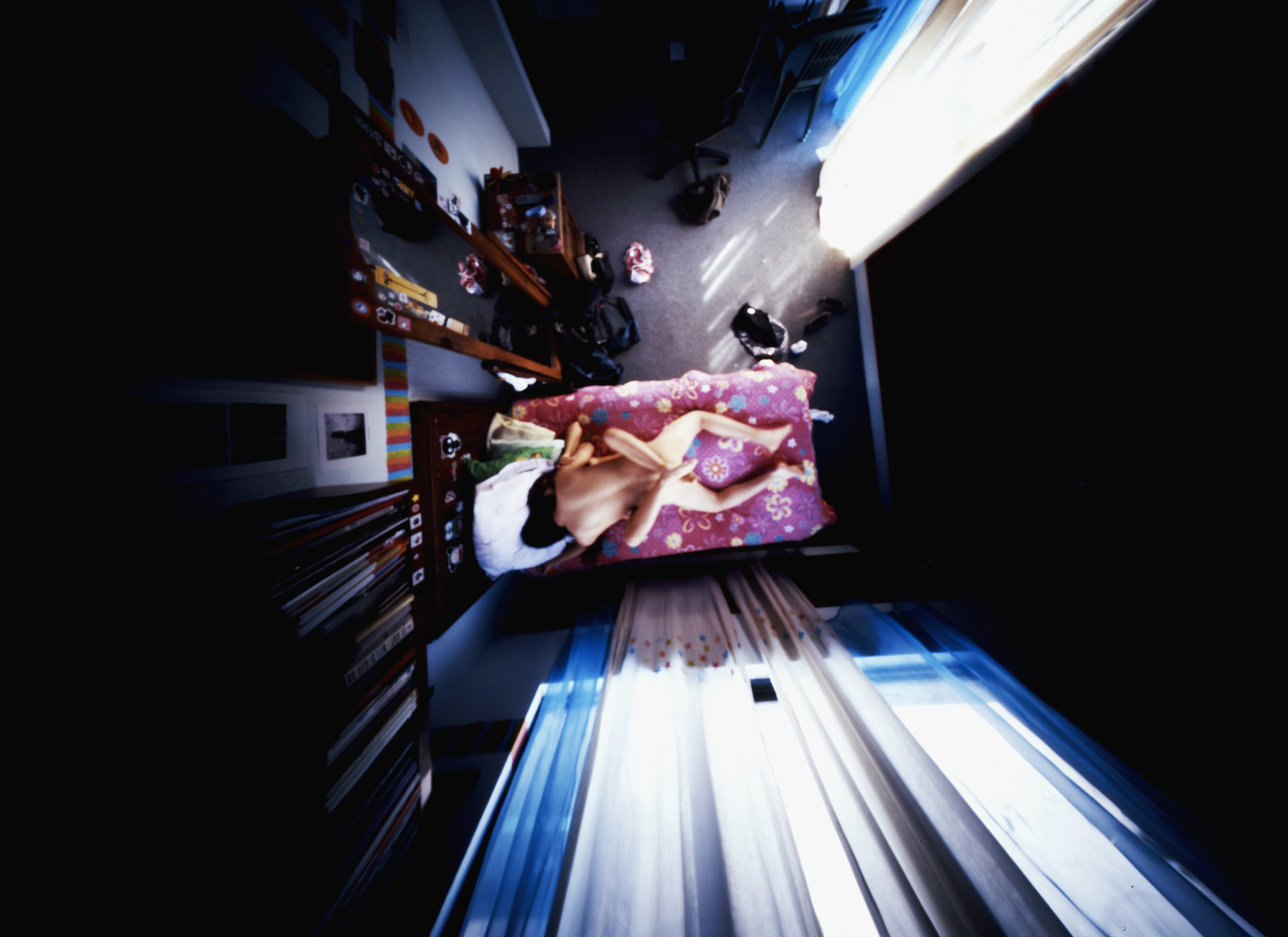

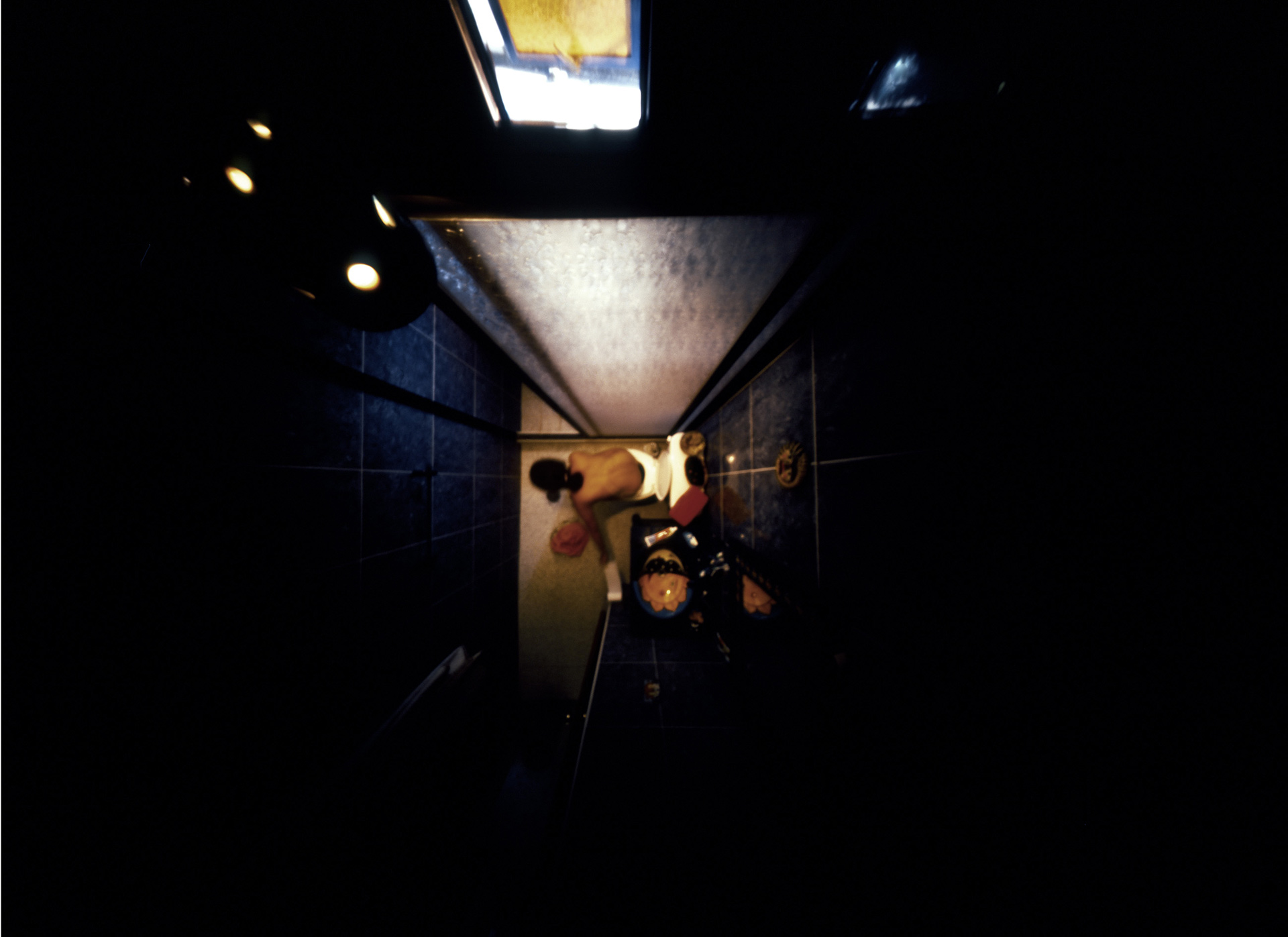

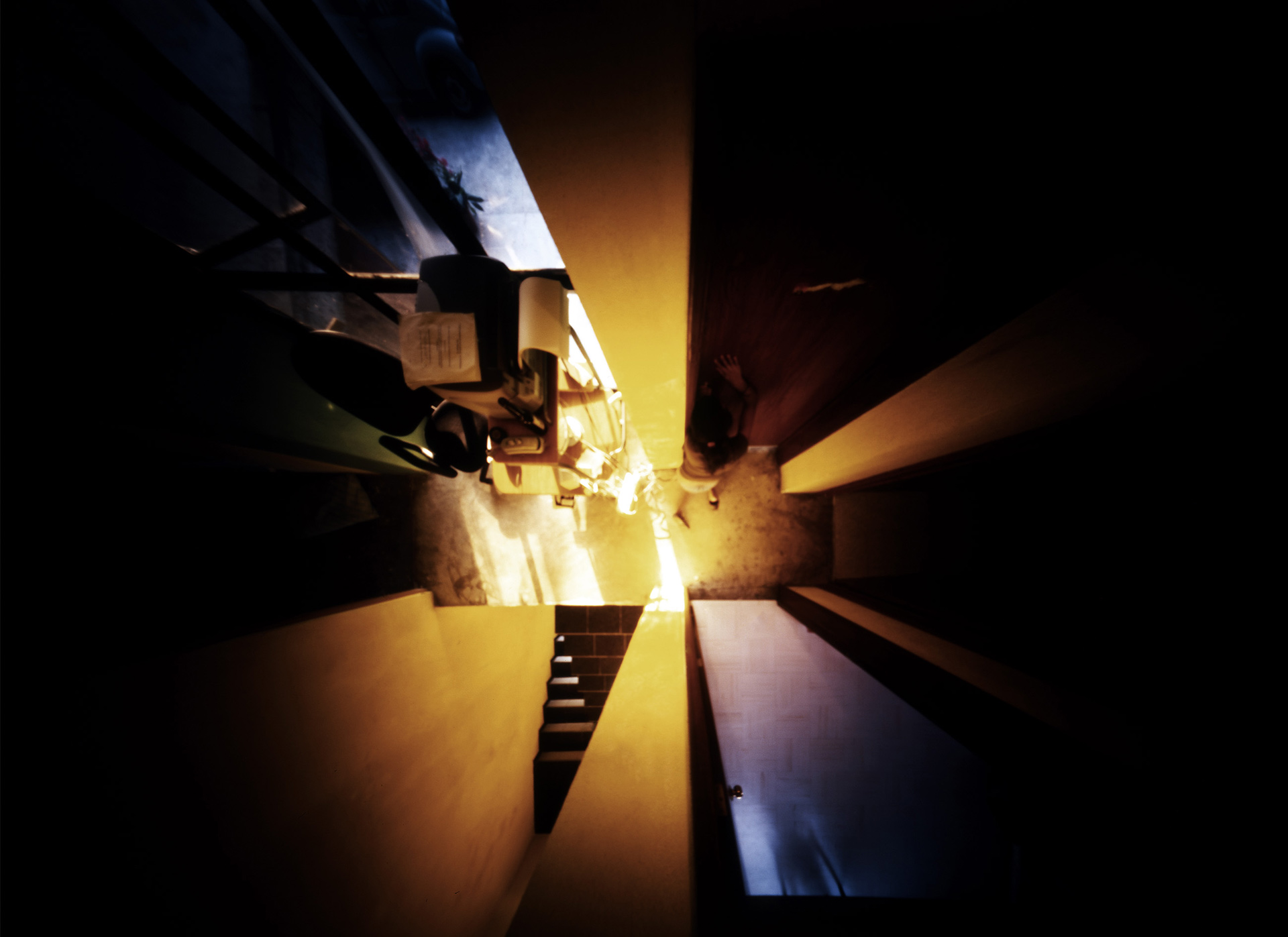

This project is based on the idea of the vigilant eye that threatens us to do no wrong. With this idea in mind, the author depicts her family environment, from conflicts to normal daily life, as if they were being monitored by a divine, human or mechanical being (God, spies or Big Brother). She presents these images from the point of view that each one of us is somehow controlled by a system, which reinforces the moral burden one feels when committing sins, crimes and mistakes.

The work presents daily life through images taken from different angles. With her handmade pinhole camera, the author establishes a certain feeling of omnipresence. She allows us to immerse ourselves in her experiences and the daily life between the walls of her home, giving the spectator a panoptic vision of her family as the so-called social unit of our times. Proving, in the end, that the society of the spectacle has encouraged a certain voyeurism through reality shows, which compel us to take sides and to judge the acts of the observed, and which puts us in the position of the divine being that tilts the scale of judgement towards the good or the bad.

We invite you to learn more about the preoccupations and the questionings of the author through this video.

Xtabay Alderete (Mexico, 1979). Lives and works in Mexico City. Graduated from the School of Visual Arts, UNAM, with a bachelor´s degree in Visual Arts. At present, she studies a master in Visual Arts at the Academy of San Carlos, UNAM. Her artistic work focuses primarily on photography. In 2013 she took part in the exhibition (Re)Presentations, Contemporary Latin-American Photography, organised by PHotoEspaña, Madrid. Currently, she intervenes in landscapes that contain memory, oblivion, death and devastation, using objects.

Xtabay Alderete (Mexico, 1979). Lives and works in Mexico City. Graduated from the School of Visual Arts, UNAM, with a bachelor´s degree in Visual Arts. At present, she studies a master in Visual Arts at the Academy of San Carlos, UNAM. Her artistic work focuses primarily on photography. In 2013 she took part in the exhibition (Re)Presentations, Contemporary Latin-American Photography, organised by PHotoEspaña, Madrid. Currently, she intervenes in landscapes that contain memory, oblivion, death and devastation, using objects.

This project is based on the idea of the vigilant eye that threatens us to do no wrong. With this idea in mind, the author depicts her family environment, from conflicts to normal daily life, as if they were being monitored by a divine, human or mechanical being (God, spies or Big Brother). She presents these images from the point of view that each one of us is somehow controlled by a system, which reinforces the moral burden one feels when committing sins, crimes and mistakes.

The work presents daily life through images taken from different angles. With her handmade pinhole camera, the author establishes a certain feeling of omnipresence. She allows us to immerse ourselves in her experiences and the daily life between the walls of her home, giving the spectator a panoptic vision of her family as the so-called social unit of our times. Proving, in the end, that the society of the spectacle has encouraged a certain voyeurism through reality shows, which compel us to take sides and to judge the acts of the observed, and which puts us in the position of the divine being that tilts the scale of judgement towards the good or the bad.

We invite you to learn more about the preoccupations and the questionings of the author through this video.

Xtabay Alderete (Mexico, 1979). Lives and works in Mexico City. Graduated from the School of Visual Arts, UNAM, with a bachelor´s degree in Visual Arts. At present, she studies a master in Visual Arts at the Academy of San Carlos, UNAM. Her artistic work focuses primarily on photography. In 2013 she took part in the exhibition (Re)Presentations, Contemporary Latin-American Photography, organised by PHotoEspaña, Madrid. Currently, she intervenes in landscapes that contain memory, oblivion, death and devastation, using objects.

Xtabay Alderete (Mexico, 1979). Lives and works in Mexico City. Graduated from the School of Visual Arts, UNAM, with a bachelor´s degree in Visual Arts. At present, she studies a master in Visual Arts at the Academy of San Carlos, UNAM. Her artistic work focuses primarily on photography. In 2013 she took part in the exhibition (Re)Presentations, Contemporary Latin-American Photography, organised by PHotoEspaña, Madrid. Currently, she intervenes in landscapes that contain memory, oblivion, death and devastation, using objects.ZoneZero

Interview with Xtabay Alderete about her process of Panopticon series. Visit her gallery here.

July 2014 by ZoneZero.

Xtabay Alderete (Mexico, 1979). Lives and works in Mexico City. Graduated from the School of Visual Arts, UNAM, with a bachelor´s degree in Visual Arts. At present, she studies a master in Visual Arts at the Academy of San Carlos, UNAM. Her artistic work focuses primarily on photography. In 2013 she took part in the exhibition (Re)Presentations, Contemporary Latin-American Photography, organised by PHotoEspaña, Madrid. Currently, she intervenes in landscapes that contain memory, oblivion, death and devastation, using objects.

Xtabay Alderete (Mexico, 1979). Lives and works in Mexico City. Graduated from the School of Visual Arts, UNAM, with a bachelor´s degree in Visual Arts. At present, she studies a master in Visual Arts at the Academy of San Carlos, UNAM. Her artistic work focuses primarily on photography. In 2013 she took part in the exhibition (Re)Presentations, Contemporary Latin-American Photography, organised by PHotoEspaña, Madrid. Currently, she intervenes in landscapes that contain memory, oblivion, death and devastation, using objects.Interview with Xtabay Alderete about her process of Panopticon series. Visit her gallery here.

July 2014 by ZoneZero.

Xtabay Alderete (Mexico, 1979). Lives and works in Mexico City. Graduated from the School of Visual Arts, UNAM, with a bachelor´s degree in Visual Arts. At present, she studies a master in Visual Arts at the Academy of San Carlos, UNAM. Her artistic work focuses primarily on photography. In 2013 she took part in the exhibition (Re)Presentations, Contemporary Latin-American Photography, organised by PHotoEspaña, Madrid. Currently, she intervenes in landscapes that contain memory, oblivion, death and devastation, using objects.

Xtabay Alderete (Mexico, 1979). Lives and works in Mexico City. Graduated from the School of Visual Arts, UNAM, with a bachelor´s degree in Visual Arts. At present, she studies a master in Visual Arts at the Academy of San Carlos, UNAM. Her artistic work focuses primarily on photography. In 2013 she took part in the exhibition (Re)Presentations, Contemporary Latin-American Photography, organised by PHotoEspaña, Madrid. Currently, she intervenes in landscapes that contain memory, oblivion, death and devastation, using objects.Adriana Raggi

Throughout the history of art, humans have persistently looked at themselves, leading us all to perceive ourselves in an image that is repeated ad nauseam, yet is at the same time entirely essential. During earlier periods of art, whose productions are assumed to be of particular clarity, the self-portrait existed as a form enabling the artist to stand before others and declare who they were. Today, a complex process is taking place and we can therefore not call it self-portraiture, but seek other names, the most common being self-representation.

1.

Regardless of how we refer to it, a moment occurs in representation in which the artist carries out a performative act, in which he sees himself, which entails identification with the spectator. This action involves questioning the audience, the artist and the medium employed. One specific example is the key moment in Cris Birrenbach’s work Identidade, when he destroys himself before the camera, before us, to show us that gender and beauty can be referred to both playfully and violently, and that gender is merely a social construct achieved through performance. We act it out and repeat it, and in the same vein Birrenbach carries out an action before us which involves removing his gender and putting it on. He adopts it, discards it and then takes it up again. We are his mirror. We see him in this process of destruction, and feel strongly attracted to the image of a practice that we have undergone without realizing.

Identidade by Cris Bierrenbach

2.

On the other side of the mirror is Nicola Costantino, in her work Unfinished Rhapsody. In this video-installation presented at the Venice Biennial and embroiled in political controversy – when the Argentinian government wished to give it its own ending1 Argentina’s collective memory to bring us an intimate Evita, who is Eva and yet Nicola. In this work, self-representation is a form of self-destruction and reconstruction of the image of herself and of a historical icon of modern Argentina. It is a mise en scène, a performative construction of the artist’s body within Evita’s body. Costantino uses technology to reconstruct, through scenography and video, the history of the appliance that Eva allegedly used to support her sick body during her last public appearance. This was an Eva striving to maintain an image of strength. Meanwhile, Nicola’s body reveals a wound and a mystery.

Unfinished Rhapsody by Nicola Costantino

3.

The mystery of Eva is encapsulated in the work Meshes of the Afternoon by Maya Deren, in which the artist uses her image repeatedly, thus confronting us with episodes from our daily life and psyche and placing us in terrifyingly familiar spaces. Deren is pursuing a mysterious figure to find herself over and over again. The representations of Maya are ominous yet sumptuously beautiful. They remind us that we are only here for an instant.

Meshes of the Afternoon by Maya Deren

Final

When Guillermo Gómez Peña looks at us in his video performance To Death (Second duel), he says: “I have a surprise for you”, and from that moment onwards a mise en scène begins that enables us to understand the performance. Several questions remain unanswered. He puts on his body, as do Bierrenbach, Costantino and Deren. Here, his body is a self-representation but also a teaching tool. In his hands he holds a gun, the most powerful of tools. He aims it at us and shows us directly what all the other works have subtly demonstrated . A performative self-representation comments on the human being itself, and confronts us with what we are and are not. When we see Deren looking at herself, Bierrenbach destroying himself through violence, Costantino constructing herself in the body of another person, and finally, Gómez Peña aiming a gun at us, we realize that we are viewing out own finitude and fragility. What we are and do is determined by time, by the wound of knowing that we are going to die, the fragility of flesh and the absurd captivity of social limitations. At that moment, we can see each and every one of us.

To Death by Guillermo Gómez Peña

Adriana Raggi (Mexico, 1970). Lives and works in Mexico. She has a Bachelor’s degree in Visual Arts at the National School of Plastic Arts and a Master’s degree and Doctorate in Art History at the Faculty of Philosophy and Literature, UNAM. She also followed the program Photo Narrative and New Media at the Pedro Meyer Foundation. She is professor at the National School of Plastic Arts and a member of the collective Las Disidentes. She has exhibited her work in Mexico and the United States, and also participated in more than twenty collective exhibitions. To see more of her work go to: www.adrianaraggi.net

Adriana Raggi (Mexico, 1970). Lives and works in Mexico. She has a Bachelor’s degree in Visual Arts at the National School of Plastic Arts and a Master’s degree and Doctorate in Art History at the Faculty of Philosophy and Literature, UNAM. She also followed the program Photo Narrative and New Media at the Pedro Meyer Foundation. She is professor at the National School of Plastic Arts and a member of the collective Las Disidentes. She has exhibited her work in Mexico and the United States, and also participated in more than twenty collective exhibitions. To see more of her work go to: www.adrianaraggi.net[core_state] => 1 [core_access] => 1 [core_metadata] => {"robots":"","author":"Adriana Raggi","rights":"","xreference":""} [core_created_user_id] => 841 [core_created_by_alias] => [core_created_time] => 2014-06-20 17:00:00 [core_images] => {"image_intro":"images\/categories\/liquididentity\/raggi.jpg","float_intro":"","image_intro_alt":"","image_intro_caption":"","image_fulltext":"images\/categories\/liquididentity\/raggi.jpg","float_fulltext":"","image_fulltext_alt":"","image_fulltext_caption":""} [core_modified_time] => 2015-09-30 17:48:39 [core_language] => en-GB [core_catid] => 47 [core_publish_up] => 2014-06-20 17:00:00 [core_publish_down] => 0000-00-00 00:00:00 [content_type_title] => Article [router] => ContentHelperRoute::getArticleRoute [author] => [author_email] => [link] => index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=185:self-representation-and-mystery&catid=47&lang=en-GB [displayDate] => 2014-06-20 17:00:00 [event] => stdClass Object ( [afterDisplayTitle] => [beforeDisplayContent] => [afterDisplayContent] => ) [text] =>

Throughout the history of art, humans have persistently looked at themselves, leading us all to perceive ourselves in an image that is repeated ad nauseam, yet is at the same time entirely essential. During earlier periods of art, whose productions are assumed to be of particular clarity, the self-portrait existed as a form enabling the artist to stand before others and declare who they were. Today, a complex process is taking place and we can therefore not call it self-portraiture, but seek other names, the most common being self-representation.

1.

Regardless of how we refer to it, a moment occurs in representation in which the artist carries out a performative act, in which he sees himself, which entails identification with the spectator. This action involves questioning the audience, the artist and the medium employed. One specific example is the key moment in Cris Birrenbach’s work Identidade, when he destroys himself before the camera, before us, to show us that gender and beauty can be referred to both playfully and violently, and that gender is merely a social construct achieved through performance. We act it out and repeat it, and in the same vein Birrenbach carries out an action before us which involves removing his gender and putting it on. He adopts it, discards it and then takes it up again. We are his mirror. We see him in this process of destruction, and feel strongly attracted to the image of a practice that we have undergone without realizing.

Identidade by Cris Bierrenbach

2.

On the other side of the mirror is Nicola Costantino, in her work Unfinished Rhapsody. In this video-installation presented at the Venice Biennial and embroiled in political controversy – when the Argentinian government wished to give it its own ending1 Argentina’s collective memory to bring us an intimate Evita, who is Eva and yet Nicola. In this work, self-representation is a form of self-destruction and reconstruction of the image of herself and of a historical icon of modern Argentina. It is a mise en scène, a performative construction of the artist’s body within Evita’s body. Costantino uses technology to reconstruct, through scenography and video, the history of the appliance that Eva allegedly used to support her sick body during her last public appearance. This was an Eva striving to maintain an image of strength. Meanwhile, Nicola’s body reveals a wound and a mystery.

Unfinished Rhapsody by Nicola Costantino

3.

The mystery of Eva is encapsulated in the work Meshes of the Afternoon by Maya Deren, in which the artist uses her image repeatedly, thus confronting us with episodes from our daily life and psyche and placing us in terrifyingly familiar spaces. Deren is pursuing a mysterious figure to find herself over and over again. The representations of Maya are ominous yet sumptuously beautiful. They remind us that we are only here for an instant.

Meshes of the Afternoon by Maya Deren

Final

When Guillermo Gómez Peña looks at us in his video performance To Death (Second duel), he says: “I have a surprise for you”, and from that moment onwards a mise en scène begins that enables us to understand the performance. Several questions remain unanswered. He puts on his body, as do Bierrenbach, Costantino and Deren. Here, his body is a self-representation but also a teaching tool. In his hands he holds a gun, the most powerful of tools. He aims it at us and shows us directly what all the other works have subtly demonstrated . A performative self-representation comments on the human being itself, and confronts us with what we are and are not. When we see Deren looking at herself, Bierrenbach destroying himself through violence, Costantino constructing herself in the body of another person, and finally, Gómez Peña aiming a gun at us, we realize that we are viewing out own finitude and fragility. What we are and do is determined by time, by the wound of knowing that we are going to die, the fragility of flesh and the absurd captivity of social limitations. At that moment, we can see each and every one of us.

To Death by Guillermo Gómez Peña

Adriana Raggi (Mexico, 1970). Lives and works in Mexico. She has a Bachelor’s degree in Visual Arts at the National School of Plastic Arts and a Master’s degree and Doctorate in Art History at the Faculty of Philosophy and Literature, UNAM. She also followed the program Photo Narrative and New Media at the Pedro Meyer Foundation. She is professor at the National School of Plastic Arts and a member of the collective Las Disidentes. She has exhibited her work in Mexico and the United States, and also participated in more than twenty collective exhibitions. To see more of her work go to: www.adrianaraggi.net

Adriana Raggi (Mexico, 1970). Lives and works in Mexico. She has a Bachelor’s degree in Visual Arts at the National School of Plastic Arts and a Master’s degree and Doctorate in Art History at the Faculty of Philosophy and Literature, UNAM. She also followed the program Photo Narrative and New Media at the Pedro Meyer Foundation. She is professor at the National School of Plastic Arts and a member of the collective Las Disidentes. She has exhibited her work in Mexico and the United States, and also participated in more than twenty collective exhibitions. To see more of her work go to: www.adrianaraggi.net[id] => 185 [language] => en-GB [catid] => 47 [jcfields] => Array ( ) ) 1

Melissa Valenzuela y Ehekatl Hernández

Photography has modified not only its devices for recording images but also its range of subjects and of course its means of dissemination. Traditional media such as paper and books were taken over a long time ago by their digital counterparts, which enable thousands of images to be shared on the Internet and mobile devices every day. As time went by and technology evolved, graphic formats emerged with a distinct advantage in terms of image quality, the use of animations and the layer of interaction. Many of these, such as Flash technology, were at first innovative and widely used, but rapidly replaced.

In this context, one of the formats that has existed alongside the Web since its inception, and remains popular, is GIF (Graphic Interchange Format), a form of technology developed in 1987 by the company CompuServe. Long before screen and monitor resolution brought viewers thousands or even millions of colors with sophisticated compression algorithms, such as JPGs or PNGs, the GIF already enabled graphics of a maximum of 256 colors to be inserted. A few years later, an improvement allowed more than one graph to be incorporated sequentially, and for the first time modest animations could be created on the emerging Web, with low weight and rapid display without extra plug-in. And so the ANIMATED GIF was born.

Other formats have gradually fallen into disuse because of incompatibility with new devices, their high processing requirements for proper display and visualization, or their reliance on complex tools to add animation and interactivity. Meanwhile, the GIF has continued to function, thanks to its flexibility and compatibility with many different systems, browsers and even mobile devices. As a result, it has been widely used recently, and is no longer limited to publicists and marketers.

In this context, and as part of the current trend towards immediacy, GIF has established itself as an interesting tool for visual expression and experimentation, because of its particular technical, communicative and expressive qualities. Indeed, ANIMATED GIFs enable users to create authentic moving photographs that record short, repetitive actions. Reproduction in a loop (infinite repetition) emphasizes the idea of the redundancy of the moment, and consequently the instant grows, completes the action and highlights it. Time is no longer suspended for eternity, but is now redundant. This is the case of the so-called “Cinemagraph”, a variation of the animated GIF in which movement is restricted to an area or specific element of the shot. GIFs do not attempt to freeze the instant and instead insist on it, expressing itself time and time again in the image.

This narrows the gap between photography, cinema and video. These frames in movement allude to the first cinematographic films by the Lumière brothers, which captured instants of an action and reproduced the sequence to emulate movement. Unlike that era, viewers are currently not only accustomed to images but oversaturated with them. Observation is no longer guided by surprise, but by identification with an instant that is indefinitely prolonged.

In contrast with the visual quality of cinema and photography, ANIMATED GIFs remind us of the texture of the first video cameras, a pastel-colored, poor quality image lacking depth. Cinema and photography maintain a certain expressive and visual independence from video and GIF. Those media refer to different concepts, as they have varied methods of dissemination and a different form of interaction with the viewer. They establish a relationship with an active spectator who repeatedly gives meaning to the image, reconstructing and reinterpreting in accordance with various factors that range from perception and the relation of each person to time, to external factors such as interface and the device supporting the image.

And yet, the contents manipulated by GIFs often draw on images extracted specifically from photographs, films or videos, and treated to emphasize a concrete action or some elements in movement. GIF narratives are ephemeral but reiterative, describing the instant and action, delving into content and the capacity for seduction and transmitting ideas and feelings. Indeed, action in movement is always the backbone of a visual construction charged with meanings.

Not surprisingly, this digital format is currently being explored by visual artists and photographers, to produce images in movement as an alternative to the formulas of cinema, video or animation shots. Though it may seem complex to understand the spectrum in which the ANIMATED GIF exists, the format has transformed its limited scope in the use of time into its greatest asset, with extensive expressive and conceptual possibilities. It also provides guidelines to redefine the notions and concepts, even at a theoretical level, involved in the constant evolution of photography, which will certainly not be the same in years to come.

Melissa Valenzuela (Colombia, 1982). Lives and works in Mexico City. She holds a Masters’ Degree in Visual Arts from the Escuela Nacional de Artes Pláticas at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM), and studied Audiovisual Communication at the Pontificia Universidad Javeriana de Bogotá. Valenzuela is an artist, and her work consists of self-portraits and recollections that address various nuances of perception, representation and memory. She also works in curatorship and education to integrate her artistic and research work..

Melissa Valenzuela (Colombia, 1982). Lives and works in Mexico City. She holds a Masters’ Degree in Visual Arts from the Escuela Nacional de Artes Pláticas at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM), and studied Audiovisual Communication at the Pontificia Universidad Javeriana de Bogotá. Valenzuela is an artist, and her work consists of self-portraits and recollections that address various nuances of perception, representation and memory. She also works in curatorship and education to integrate her artistic and research work.. Ehekatl Hernández (México, 1975).received a Bachelor’s Degree in Graphic Design from the Escuela Nacional de Artes Plásticas at UNAM in Mexico, and a Master’s Degree in Multimedia Applications from the Universidad Poltécnica de Catalunya in Spain. He has over 15 years’ experience in graphic design and planning, developing and implementing web projects. Hernández has given diploma courses in web design at UNAM. He has spent nine years contributing to the web design and multimedia area at zonezero.com, and also works as a consultant for various companies as well as coordinating the e-learning system of the Virtual Campus of the Pedro Meyer Foundation.

Ehekatl Hernández (México, 1975).received a Bachelor’s Degree in Graphic Design from the Escuela Nacional de Artes Plásticas at UNAM in Mexico, and a Master’s Degree in Multimedia Applications from the Universidad Poltécnica de Catalunya in Spain. He has over 15 years’ experience in graphic design and planning, developing and implementing web projects. Hernández has given diploma courses in web design at UNAM. He has spent nine years contributing to the web design and multimedia area at zonezero.com, and also works as a consultant for various companies as well as coordinating the e-learning system of the Virtual Campus of the Pedro Meyer Foundation.

Photography has modified not only its devices for recording images but also its range of subjects and of course its means of dissemination. Traditional media such as paper and books were taken over a long time ago by their digital counterparts, which enable thousands of images to be shared on the Internet and mobile devices every day. As time went by and technology evolved, graphic formats emerged with a distinct advantage in terms of image quality, the use of animations and the layer of interaction. Many of these, such as Flash technology, were at first innovative and widely used, but rapidly replaced.

In this context, one of the formats that has existed alongside the Web since its inception, and remains popular, is GIF (Graphic Interchange Format), a form of technology developed in 1987 by the company CompuServe. Long before screen and monitor resolution brought viewers thousands or even millions of colors with sophisticated compression algorithms, such as JPGs or PNGs, the GIF already enabled graphics of a maximum of 256 colors to be inserted. A few years later, an improvement allowed more than one graph to be incorporated sequentially, and for the first time modest animations could be created on the emerging Web, with low weight and rapid display without extra plug-in. And so the ANIMATED GIF was born.

Other formats have gradually fallen into disuse because of incompatibility with new devices, their high processing requirements for proper display and visualization, or their reliance on complex tools to add animation and interactivity. Meanwhile, the GIF has continued to function, thanks to its flexibility and compatibility with many different systems, browsers and even mobile devices. As a result, it has been widely used recently, and is no longer limited to publicists and marketers.

In this context, and as part of the current trend towards immediacy, GIF has established itself as an interesting tool for visual expression and experimentation, because of its particular technical, communicative and expressive qualities. Indeed, ANIMATED GIFs enable users to create authentic moving photographs that record short, repetitive actions. Reproduction in a loop (infinite repetition) emphasizes the idea of the redundancy of the moment, and consequently the instant grows, completes the action and highlights it. Time is no longer suspended for eternity, but is now redundant. This is the case of the so-called “Cinemagraph”, a variation of the animated GIF in which movement is restricted to an area or specific element of the shot. GIFs do not attempt to freeze the instant and instead insist on it, expressing itself time and time again in the image.

This narrows the gap between photography, cinema and video. These frames in movement allude to the first cinematographic films by the Lumière brothers, which captured instants of an action and reproduced the sequence to emulate movement. Unlike that era, viewers are currently not only accustomed to images but oversaturated with them. Observation is no longer guided by surprise, but by identification with an instant that is indefinitely prolonged.

In contrast with the visual quality of cinema and photography, ANIMATED GIFs remind us of the texture of the first video cameras, a pastel-colored, poor quality image lacking depth. Cinema and photography maintain a certain expressive and visual independence from video and GIF. Those media refer to different concepts, as they have varied methods of dissemination and a different form of interaction with the viewer. They establish a relationship with an active spectator who repeatedly gives meaning to the image, reconstructing and reinterpreting in accordance with various factors that range from perception and the relation of each person to time, to external factors such as interface and the device supporting the image.

And yet, the contents manipulated by GIFs often draw on images extracted specifically from photographs, films or videos, and treated to emphasize a concrete action or some elements in movement. GIF narratives are ephemeral but reiterative, describing the instant and action, delving into content and the capacity for seduction and transmitting ideas and feelings. Indeed, action in movement is always the backbone of a visual construction charged with meanings.

Not surprisingly, this digital format is currently being explored by visual artists and photographers, to produce images in movement as an alternative to the formulas of cinema, video or animation shots. Though it may seem complex to understand the spectrum in which the ANIMATED GIF exists, the format has transformed its limited scope in the use of time into its greatest asset, with extensive expressive and conceptual possibilities. It also provides guidelines to redefine the notions and concepts, even at a theoretical level, involved in the constant evolution of photography, which will certainly not be the same in years to come.

Melissa Valenzuela (Colombia, 1982). Lives and works in Mexico City. She holds a Masters’ Degree in Visual Arts from the Escuela Nacional de Artes Pláticas at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM), and studied Audiovisual Communication at the Pontificia Universidad Javeriana de Bogotá. Valenzuela is an artist, and her work consists of self-portraits and recollections that address various nuances of perception, representation and memory. She also works in curatorship and education to integrate her artistic and research work..

Melissa Valenzuela (Colombia, 1982). Lives and works in Mexico City. She holds a Masters’ Degree in Visual Arts from the Escuela Nacional de Artes Pláticas at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM), and studied Audiovisual Communication at the Pontificia Universidad Javeriana de Bogotá. Valenzuela is an artist, and her work consists of self-portraits and recollections that address various nuances of perception, representation and memory. She also works in curatorship and education to integrate her artistic and research work.. Ehekatl Hernández (México, 1975).received a Bachelor’s Degree in Graphic Design from the Escuela Nacional de Artes Plásticas at UNAM in Mexico, and a Master’s Degree in Multimedia Applications from the Universidad Poltécnica de Catalunya in Spain. He has over 15 years’ experience in graphic design and planning, developing and implementing web projects. Hernández has given diploma courses in web design at UNAM. He has spent nine years contributing to the web design and multimedia area at zonezero.com, and also works as a consultant for various companies as well as coordinating the e-learning system of the Virtual Campus of the Pedro Meyer Foundation.

Ehekatl Hernández (México, 1975).received a Bachelor’s Degree in Graphic Design from the Escuela Nacional de Artes Plásticas at UNAM in Mexico, and a Master’s Degree in Multimedia Applications from the Universidad Poltécnica de Catalunya in Spain. He has over 15 years’ experience in graphic design and planning, developing and implementing web projects. Hernández has given diploma courses in web design at UNAM. He has spent nine years contributing to the web design and multimedia area at zonezero.com, and also works as a consultant for various companies as well as coordinating the e-learning system of the Virtual Campus of the Pedro Meyer Foundation.Pedro Meyer

Pedro Meyer, 2011

The current proliferation of the photographic image is the result of two parallel situations. Firstly, human beings are primarily visual beings, and secondly, we feel the need to tell stories.

The tools to record images permanently are developing in a new and different way, as each click of the shutter is free of cost and can be shared immediately, unconstrained by geographical boundaries. They thus break previous paradigms.

Just as the advent of the printing press transferred the power of reading and writing from a few select monks to the masses, nowadays photography is not only produced by an exclusive group of “image monks" but by a mass of people with a story to share.

There is a very vocal point of view that “we are not all photographers”, expressed as vehemently as the monks would defend their profession of scribes and illustrators of handmade books against those mass-produced by movable type presses. It is clear who triumphed in this debate, and though there are still cases of books being made by hand, history has favored printed books.

There will certainly always be photographers with specific skills and techniques beyond the reach of the mass of “photographers of the people.” The former are concerned that professionals are referred to by the same name as a layman.

We are facing an issue of identity, not photography. "Photography is no longer what it used to be” – the slogan of my Foundation – encapsulates the idea that we need to review what we call things to understand them better. It therefore appears that in the first instance we understand things by defining them.

Pedro Meyer (Mexico, 1935). Lives and works in Mexico. He is a photographer and the creator of the ZoneZero portal. The founder and president of the Photography Council, he organized the first three Latin American Conferences on Photography and produced the first CD-ROM with sound and images, I Photograph to Remember. He simultaneously exhibited Heresies, a retrospective of his work in over 60 museums and galleries throughout the world. In 2007, he established the Fundación Pedro Meyer, and in 2014 he inaugurated the FotoMuseo Cuatro Caminos.

Pedro Meyer (Mexico, 1935). Lives and works in Mexico. He is a photographer and the creator of the ZoneZero portal. The founder and president of the Photography Council, he organized the first three Latin American Conferences on Photography and produced the first CD-ROM with sound and images, I Photograph to Remember. He simultaneously exhibited Heresies, a retrospective of his work in over 60 museums and galleries throughout the world. In 2007, he established the Fundación Pedro Meyer, and in 2014 he inaugurated the FotoMuseo Cuatro Caminos.

Pedro Meyer, 2011

The current proliferation of the photographic image is the result of two parallel situations. Firstly, human beings are primarily visual beings, and secondly, we feel the need to tell stories.

The tools to record images permanently are developing in a new and different way, as each click of the shutter is free of cost and can be shared immediately, unconstrained by geographical boundaries. They thus break previous paradigms.

Just as the advent of the printing press transferred the power of reading and writing from a few select monks to the masses, nowadays photography is not only produced by an exclusive group of “image monks" but by a mass of people with a story to share.

There is a very vocal point of view that “we are not all photographers”, expressed as vehemently as the monks would defend their profession of scribes and illustrators of handmade books against those mass-produced by movable type presses. It is clear who triumphed in this debate, and though there are still cases of books being made by hand, history has favored printed books.

There will certainly always be photographers with specific skills and techniques beyond the reach of the mass of “photographers of the people.” The former are concerned that professionals are referred to by the same name as a layman.

We are facing an issue of identity, not photography. "Photography is no longer what it used to be” – the slogan of my Foundation – encapsulates the idea that we need to review what we call things to understand them better. It therefore appears that in the first instance we understand things by defining them.

Pedro Meyer (Mexico, 1935). Lives and works in Mexico. He is a photographer and the creator of the ZoneZero portal. The founder and president of the Photography Council, he organized the first three Latin American Conferences on Photography and produced the first CD-ROM with sound and images, I Photograph to Remember. He simultaneously exhibited Heresies, a retrospective of his work in over 60 museums and galleries throughout the world. In 2007, he established the Fundación Pedro Meyer, and in 2014 he inaugurated the FotoMuseo Cuatro Caminos.

Pedro Meyer (Mexico, 1935). Lives and works in Mexico. He is a photographer and the creator of the ZoneZero portal. The founder and president of the Photography Council, he organized the first three Latin American Conferences on Photography and produced the first CD-ROM with sound and images, I Photograph to Remember. He simultaneously exhibited Heresies, a retrospective of his work in over 60 museums and galleries throughout the world. In 2007, he established the Fundación Pedro Meyer, and in 2014 he inaugurated the FotoMuseo Cuatro Caminos.Alejandro Malo

Photo: Pedro Meyer, 1985

Alejandro Malo (Mexico, 1972). Lives and works in Mexico and is the director of ZoneZero. Since 1993, he has taken part in various cultural projects and worked as an information technology consultant. He has collaborated in print and electronic publications, and given workshops and conferences on literature, creative writing, storytelling and technology. In 2009, Malo joined the team of the Fundación Pedro Meyer, where he directs the Archives and Technology departments.

Alejandro Malo (Mexico, 1972). Lives and works in Mexico and is the director of ZoneZero. Since 1993, he has taken part in various cultural projects and worked as an information technology consultant. He has collaborated in print and electronic publications, and given workshops and conferences on literature, creative writing, storytelling and technology. In 2009, Malo joined the team of the Fundación Pedro Meyer, where he directs the Archives and Technology departments.

Photo: Pedro Meyer, 1985

Alejandro Malo (Mexico, 1972). Lives and works in Mexico and is the director of ZoneZero. Since 1993, he has taken part in various cultural projects and worked as an information technology consultant. He has collaborated in print and electronic publications, and given workshops and conferences on literature, creative writing, storytelling and technology. In 2009, Malo joined the team of the Fundación Pedro Meyer, where he directs the Archives and Technology departments.

Alejandro Malo (Mexico, 1972). Lives and works in Mexico and is the director of ZoneZero. Since 1993, he has taken part in various cultural projects and worked as an information technology consultant. He has collaborated in print and electronic publications, and given workshops and conferences on literature, creative writing, storytelling and technology. In 2009, Malo joined the team of the Fundación Pedro Meyer, where he directs the Archives and Technology departments.Page 2 of 2

Page 2 of 2