Vanessa Alcaíno & Alejandro Malo

Brown Hooded Kingfisher, (Halcyon albiventris), Chitengo Camp, Gorongosa National Park, Mozambique, 2011. By Joel Sartore

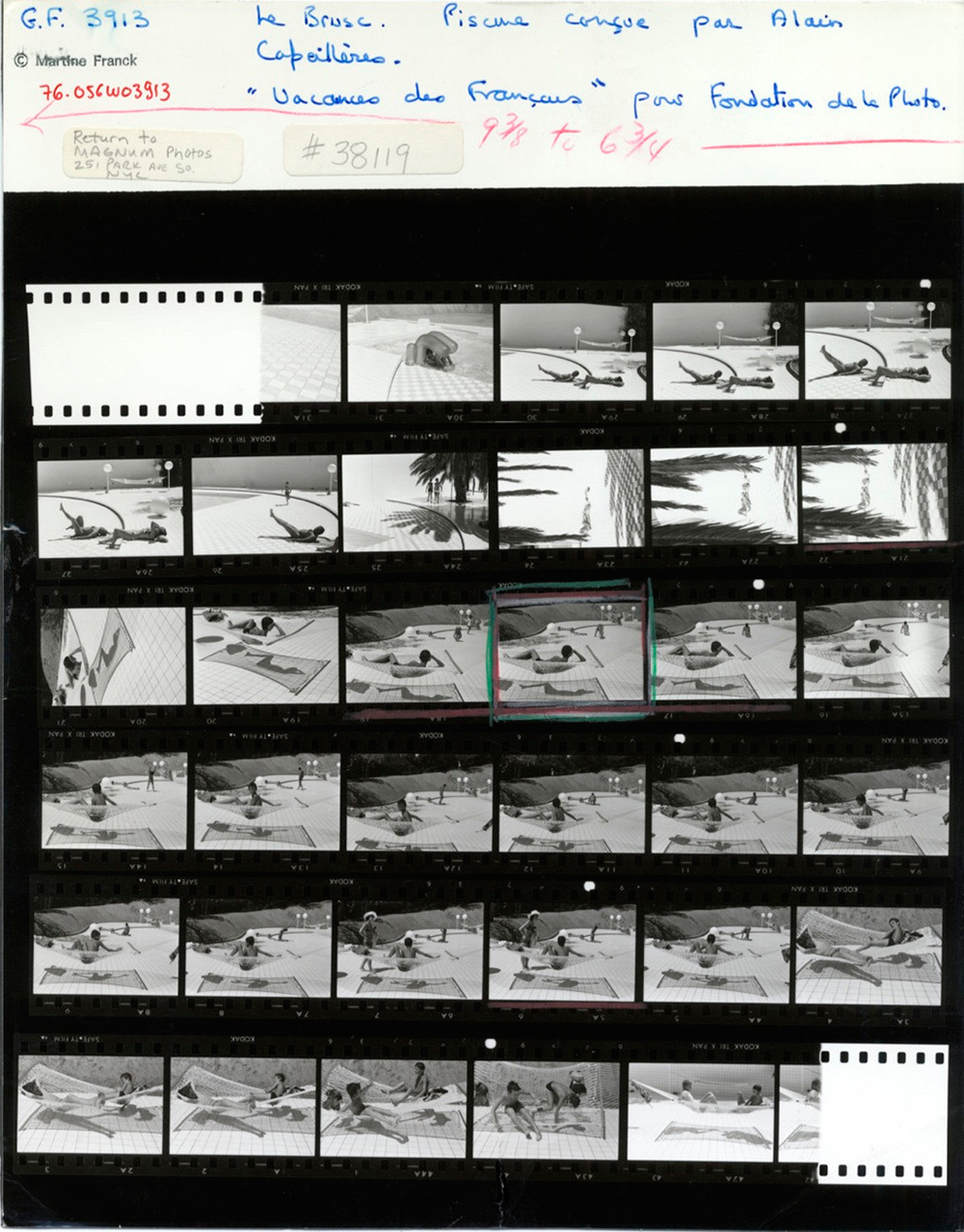

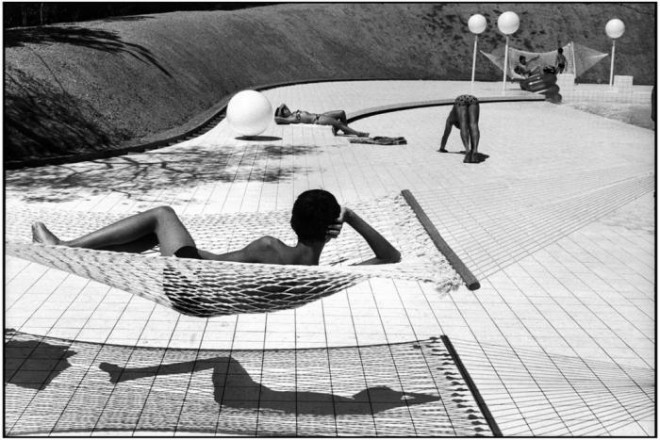

When we choose to address a landscape issue and, soon after, we realized its relationship with the theme of the FotoFest 2016 Biennial: Changing Circumstances: Looking at the Future of the Planet, we thought it appropriate to echo the concerns expressed during the festival. A few contents presented in this issue offer a digital version of the same exhibitions for our audience. However, this observation would be insufficient without emphasizing some of the ideas included in the book of the same name that drives us to insist on the invitation to peer into its pages.

Conceived as a collaboration between Frederick Baldwin and Wendy Watriss, founders of FotoFest, with Steven Evans, Executive Director of the festival, it integrates a diverse and broad mosaic of artists. In his introductory text, Steven Evans highlights the need to promote the exchange of ideas between artists who use different strategies to address the issue. It also contrast the divergence of gazes with the unifying leitmotif of Thomas E. Lovejoy and Geof Rayner essays that show an intrinsic connection between all artist’s concerns. Both essays provide strong arguments on the urgent need for action on climate change; the first, from the perspective of the Earth as a living organism, and the second by demonstrating the decisive role of human beings in their environment.

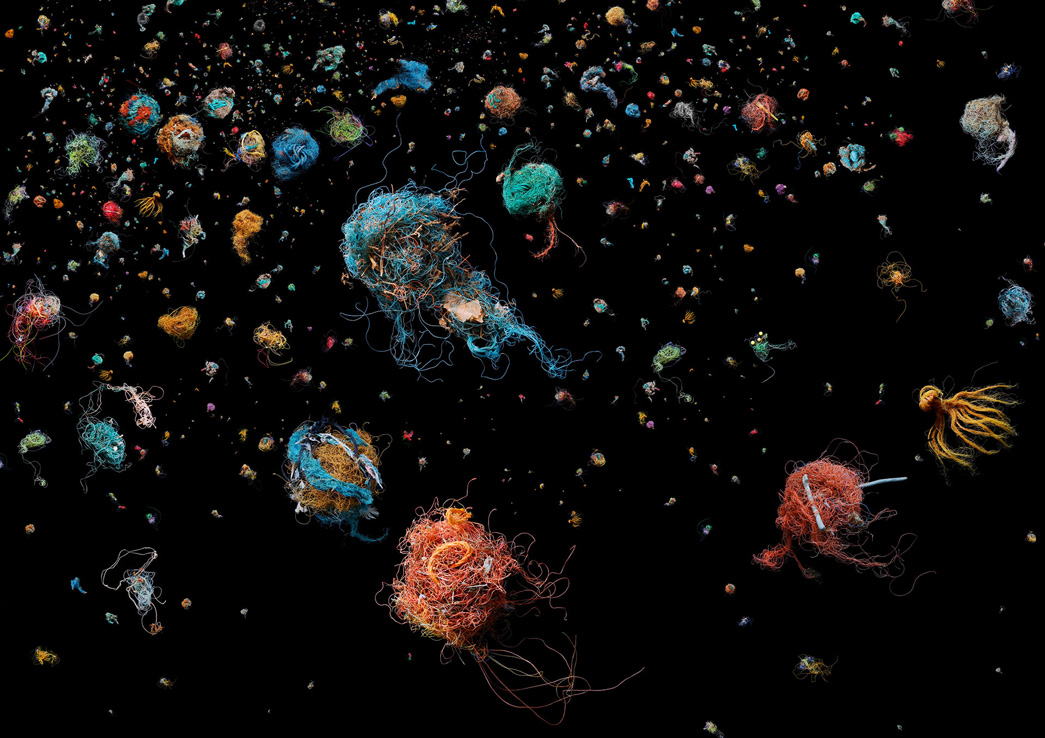

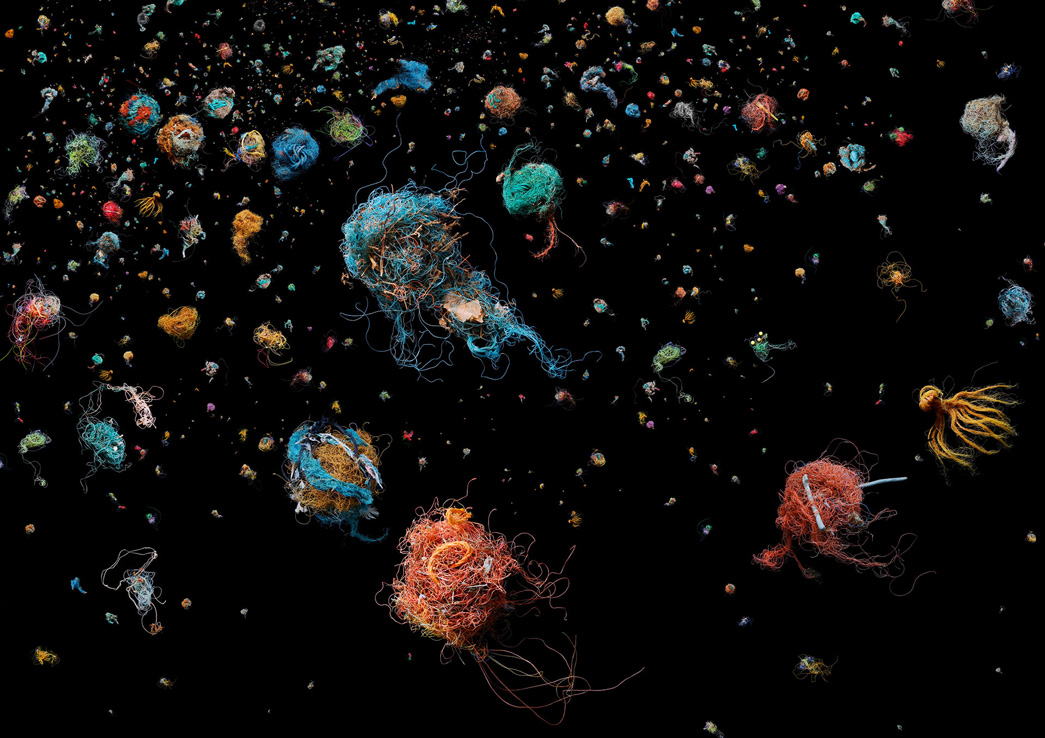

Bird’s Nest, 2011. Por Mandy Barker

Finally, Wendy Watriss gives voice to some questions that resonate with concerns we encountered during our research on the theme of landscape: "We have responsibility not only for our own well-being but that of the rest of the natural world? Can art stimulate new perspectives and new ways of seeing?” Photography has in its hands the potential to share with us realities that otherwise would be inaccessible. The images are not neutral, they feed imagination and foster reflections, being a very effective means to make any problem palpable, visible and close, to the point of being able to bring them into the political sphere and encourage agreements. We agree with Wendy’s view that art can itself stimulate and expand our world view and present innovative ways to address the issue of climate change. We should not allow ourselves to have skewed visions that only address and speak from a knowledge area or a region of the world. We must open to different cultures, include divergent views, draw new and different boundaries, create unique maps, put the world upside down, stir and divide it in various ways. That is the only way to visualize a future where rather than dominate nature, we can collaborate for its survival and ours. And this way of ‘seeing’ the world, and the new paths to our future, is what art may best express.

Vanessa Alcaíno Pizani (Venezuela, 1980). Lives and works in Mexico. Visual artist. She graduated in Philosophy at the Central University of Venezuela and has a Master’s degree in Spanish and Latin American Thought at the Autonomous University of Madrid (UAM). Since 1994, she has worked in the field of photography at various institutions and organisations in Venezuela, Argentina and Mexico. At the moment, she is part of the editorial team of zonezero.com.

Vanessa Alcaíno Pizani (Venezuela, 1980). Lives and works in Mexico. Visual artist. She graduated in Philosophy at the Central University of Venezuela and has a Master’s degree in Spanish and Latin American Thought at the Autonomous University of Madrid (UAM). Since 1994, she has worked in the field of photography at various institutions and organisations in Venezuela, Argentina and Mexico. At the moment, she is part of the editorial team of zonezero.com. Alejandro Malo (Mexico, 1972). Lives and works in Mexico and is the director of ZoneZero. Since 1993, he has taken part in various cultural projects and worked as an information technology consultant. He has collaborated in print and electronic publications, and given workshops and conferences on literature, creative writing, storytelling and technology. In 2009, Malo joined the team of the Fundación Pedro Meyer, where he directs the Archives and Technology departments.

Alejandro Malo (Mexico, 1972). Lives and works in Mexico and is the director of ZoneZero. Since 1993, he has taken part in various cultural projects and worked as an information technology consultant. He has collaborated in print and electronic publications, and given workshops and conferences on literature, creative writing, storytelling and technology. In 2009, Malo joined the team of the Fundación Pedro Meyer, where he directs the Archives and Technology departments.

Brown Hooded Kingfisher, (Halcyon albiventris), Chitengo Camp, Gorongosa National Park, Mozambique, 2011. By Joel Sartore

When we choose to address a landscape issue and, soon after, we realized its relationship with the theme of the FotoFest 2016 Biennial: Changing Circumstances: Looking at the Future of the Planet, we thought it appropriate to echo the concerns expressed during the festival. A few contents presented in this issue offer a digital version of the same exhibitions for our audience. However, this observation would be insufficient without emphasizing some of the ideas included in the book of the same name that drives us to insist on the invitation to peer into its pages.

Conceived as a collaboration between Frederick Baldwin and Wendy Watriss, founders of FotoFest, with Steven Evans, Executive Director of the festival, it integrates a diverse and broad mosaic of artists. In his introductory text, Steven Evans highlights the need to promote the exchange of ideas between artists who use different strategies to address the issue. It also contrast the divergence of gazes with the unifying leitmotif of Thomas E. Lovejoy and Geof Rayner essays that show an intrinsic connection between all artist’s concerns. Both essays provide strong arguments on the urgent need for action on climate change; the first, from the perspective of the Earth as a living organism, and the second by demonstrating the decisive role of human beings in their environment.

Bird’s Nest, 2011. Por Mandy Barker

Finally, Wendy Watriss gives voice to some questions that resonate with concerns we encountered during our research on the theme of landscape: "We have responsibility not only for our own well-being but that of the rest of the natural world? Can art stimulate new perspectives and new ways of seeing?” Photography has in its hands the potential to share with us realities that otherwise would be inaccessible. The images are not neutral, they feed imagination and foster reflections, being a very effective means to make any problem palpable, visible and close, to the point of being able to bring them into the political sphere and encourage agreements. We agree with Wendy’s view that art can itself stimulate and expand our world view and present innovative ways to address the issue of climate change. We should not allow ourselves to have skewed visions that only address and speak from a knowledge area or a region of the world. We must open to different cultures, include divergent views, draw new and different boundaries, create unique maps, put the world upside down, stir and divide it in various ways. That is the only way to visualize a future where rather than dominate nature, we can collaborate for its survival and ours. And this way of ‘seeing’ the world, and the new paths to our future, is what art may best express.

Vanessa Alcaíno Pizani (Venezuela, 1980). Lives and works in Mexico. Visual artist. She graduated in Philosophy at the Central University of Venezuela and has a Master’s degree in Spanish and Latin American Thought at the Autonomous University of Madrid (UAM). Since 1994, she has worked in the field of photography at various institutions and organisations in Venezuela, Argentina and Mexico. At the moment, she is part of the editorial team of zonezero.com.

Vanessa Alcaíno Pizani (Venezuela, 1980). Lives and works in Mexico. Visual artist. She graduated in Philosophy at the Central University of Venezuela and has a Master’s degree in Spanish and Latin American Thought at the Autonomous University of Madrid (UAM). Since 1994, she has worked in the field of photography at various institutions and organisations in Venezuela, Argentina and Mexico. At the moment, she is part of the editorial team of zonezero.com. Alejandro Malo (Mexico, 1972). Lives and works in Mexico and is the director of ZoneZero. Since 1993, he has taken part in various cultural projects and worked as an information technology consultant. He has collaborated in print and electronic publications, and given workshops and conferences on literature, creative writing, storytelling and technology. In 2009, Malo joined the team of the Fundación Pedro Meyer, where he directs the Archives and Technology departments.

Alejandro Malo (Mexico, 1972). Lives and works in Mexico and is the director of ZoneZero. Since 1993, he has taken part in various cultural projects and worked as an information technology consultant. He has collaborated in print and electronic publications, and given workshops and conferences on literature, creative writing, storytelling and technology. In 2009, Malo joined the team of the Fundación Pedro Meyer, where he directs the Archives and Technology departments.Marcus DeSieno

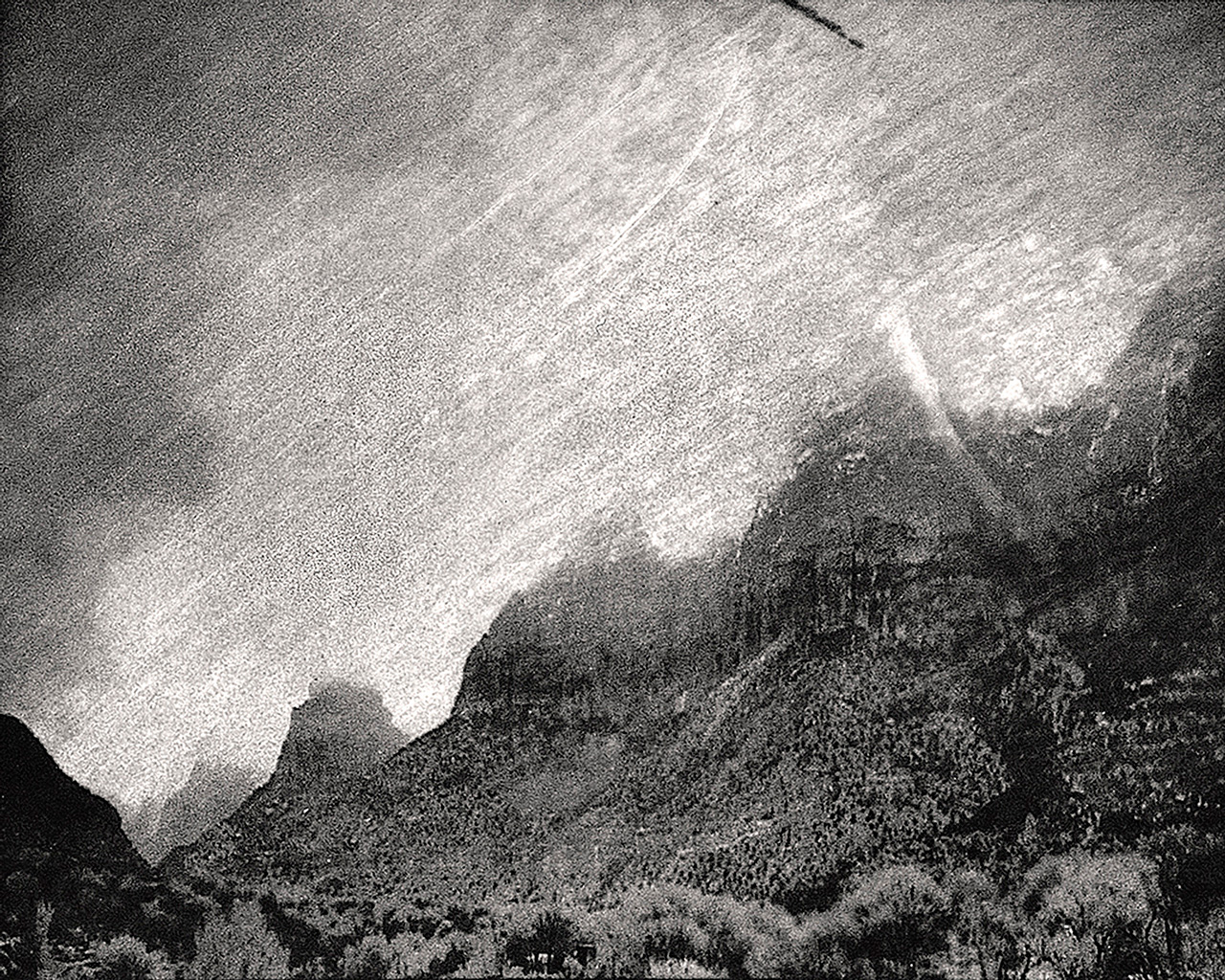

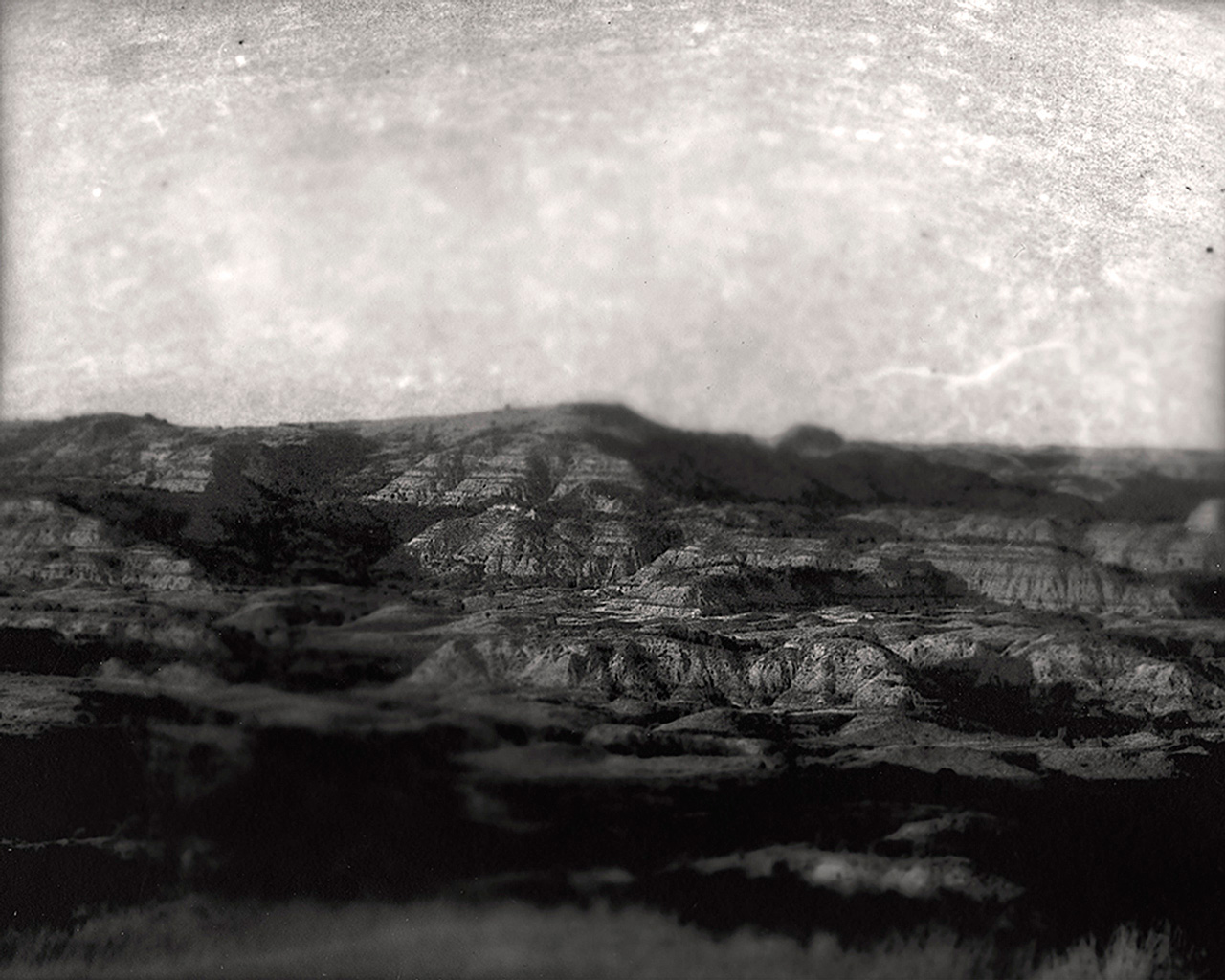

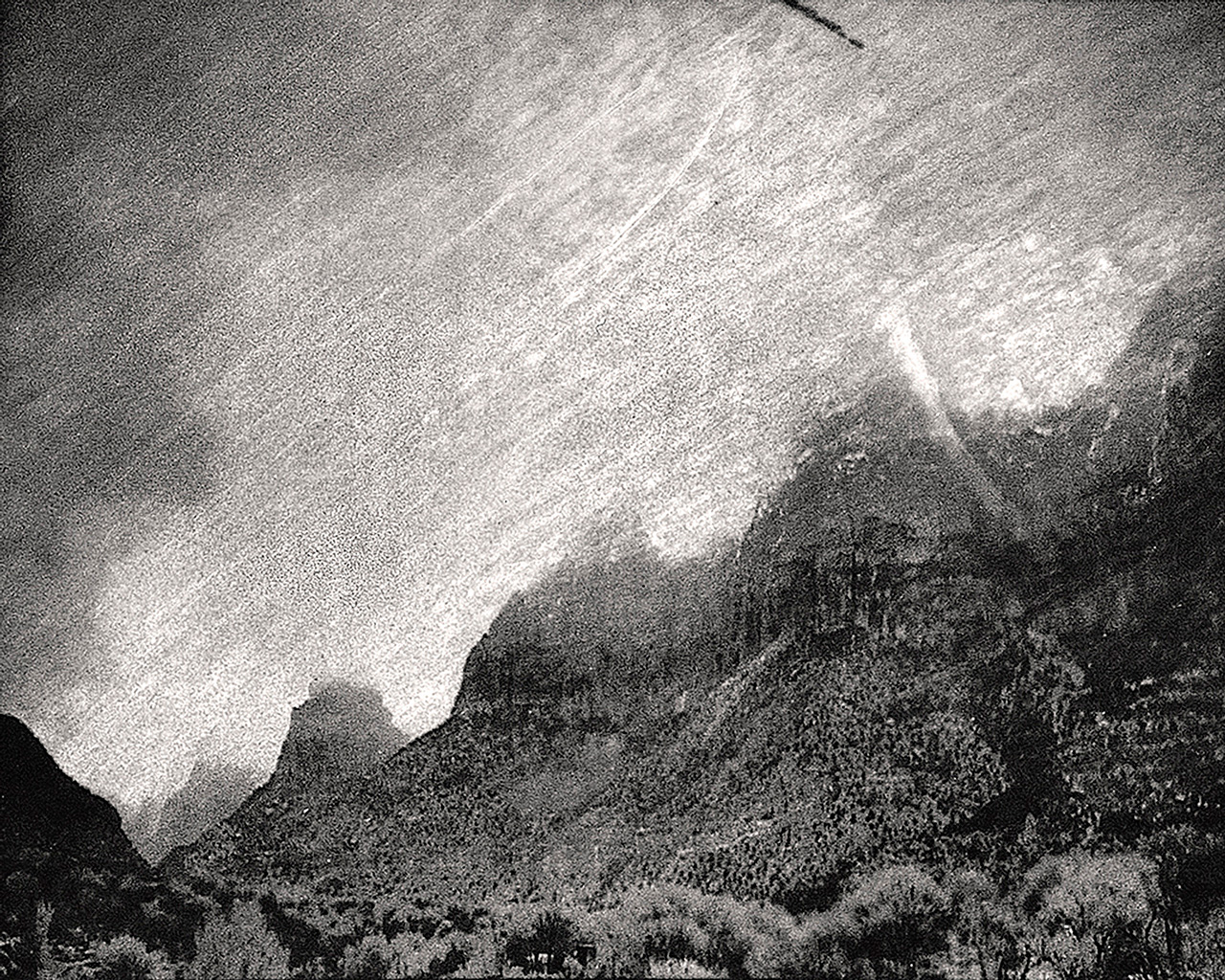

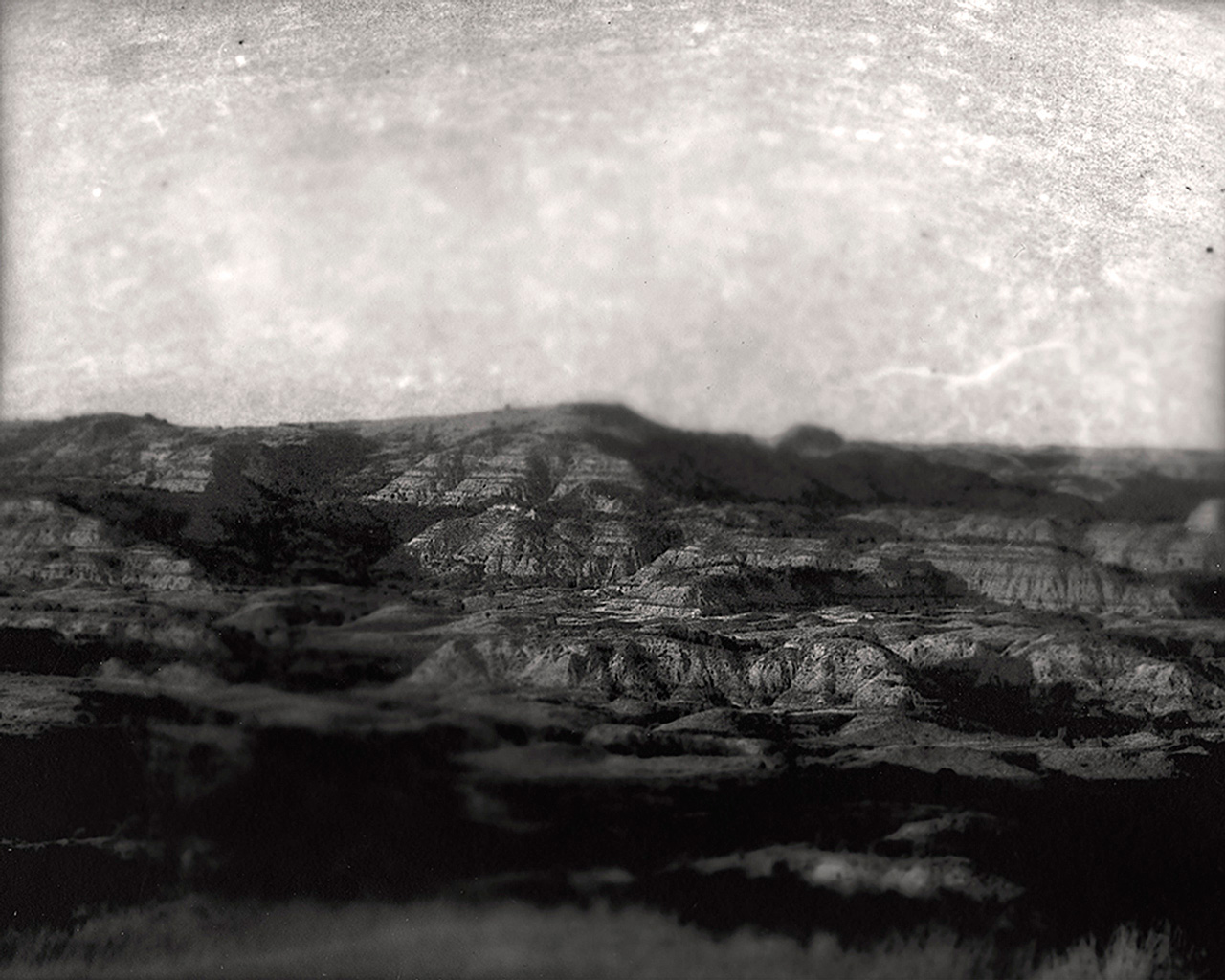

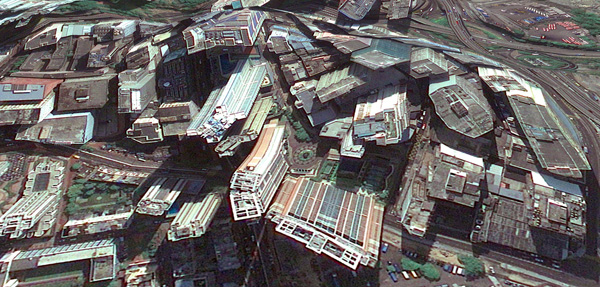

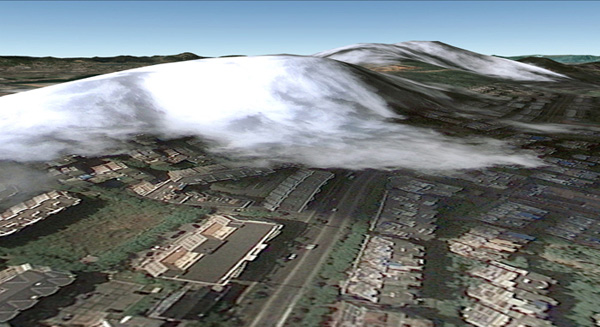

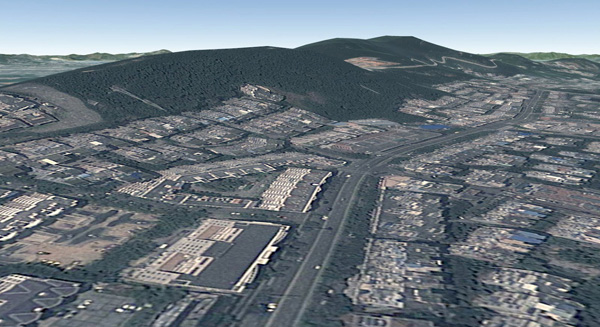

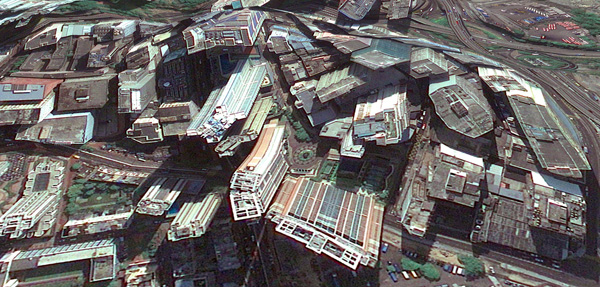

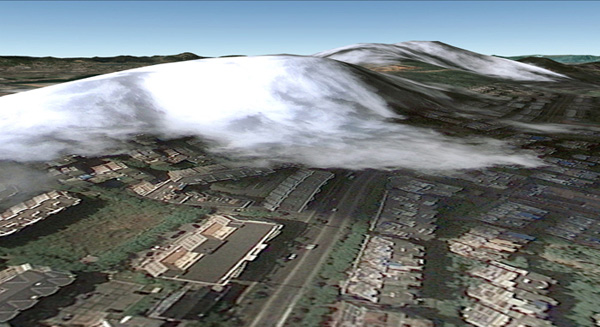

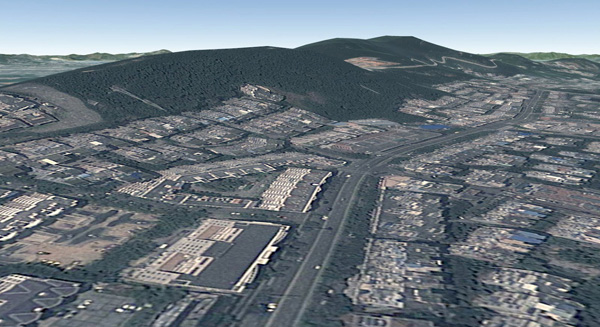

Surveillance Landscapes interrogates how surveillance technology has changed our relationship and understanding of landscape and place in our increasingly intrusive electronic culture. I hack into surveillance cameras, public webcams, and CCTV feeds in a pursuit for the classical picturesque landscape, dislocating the visual product from its automated origins while searching for a conversation between land, borders, and power. The very act of surveying a site through these photographic systems implies a dominating relationship between man and place. Ultimately, I hope to undermine these schemes of social control through the obfuscated melancholic images found while exploiting the technological mechanisms of power in our surveillance society.

Marcus DeSieno (USA). His work is concerned with science and exploration in relation to the history of photography. He received his MFA in Studio Art from the University of South Florida in 2015. DeSieno often assumes the role of the amateur scientist in his work in order to investigate photography's historic relationship with science in regards to the notion of the invisible. Antiquated and obsolescent photographic processes are often combined with contemporary imaging technologies to engage in a critical dialog on the evolution of photographic technology in relation to seeing.

Marcus DeSieno (USA). His work is concerned with science and exploration in relation to the history of photography. He received his MFA in Studio Art from the University of South Florida in 2015. DeSieno often assumes the role of the amateur scientist in his work in order to investigate photography's historic relationship with science in regards to the notion of the invisible. Antiquated and obsolescent photographic processes are often combined with contemporary imaging technologies to engage in a critical dialog on the evolution of photographic technology in relation to seeing.

Surveillance Landscapes interrogates how surveillance technology has changed our relationship and understanding of landscape and place in our increasingly intrusive electronic culture. I hack into surveillance cameras, public webcams, and CCTV feeds in a pursuit for the classical picturesque landscape, dislocating the visual product from its automated origins while searching for a conversation between land, borders, and power. The very act of surveying a site through these photographic systems implies a dominating relationship between man and place. Ultimately, I hope to undermine these schemes of social control through the obfuscated melancholic images found while exploiting the technological mechanisms of power in our surveillance society.

Marcus DeSieno (USA). His work is concerned with science and exploration in relation to the history of photography. He received his MFA in Studio Art from the University of South Florida in 2015. DeSieno often assumes the role of the amateur scientist in his work in order to investigate photography's historic relationship with science in regards to the notion of the invisible. Antiquated and obsolescent photographic processes are often combined with contemporary imaging technologies to engage in a critical dialog on the evolution of photographic technology in relation to seeing.

Marcus DeSieno (USA). His work is concerned with science and exploration in relation to the history of photography. He received his MFA in Studio Art from the University of South Florida in 2015. DeSieno often assumes the role of the amateur scientist in his work in order to investigate photography's historic relationship with science in regards to the notion of the invisible. Antiquated and obsolescent photographic processes are often combined with contemporary imaging technologies to engage in a critical dialog on the evolution of photographic technology in relation to seeing.Brad Temkin

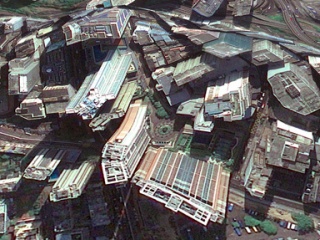

Most of my career has focused on our relationship with nature. I’m interested in how we find ways to accommodate nature, and how it accommodates us. As with most bodies of work, the pictures define my intent. But in the end, I make the pictures I do because of the conversation that occurs between the subject and myself - and this always depends on the light, the weather, how I'm feeling and what I am open to seeing at the moment. It's the moment all things come together for me.

Rooftop draws poetic attention to celebrate and proliferate new ideas in design showing the inventiveness in architecture and accommodating our need for nature. Green roofs reduce our carbon footprint by countering heat island effect and improve storm water control, but they do far more. These pictures symbolize the allure of nature in the face of our continuing urban sprawl. By securely situating the gardens within the steel, stone, and glass rectangularity of urban and industrial buildings, I ask viewers to revel in the far more open patterns, colors, and connection to the sky; and how they become part of a new landscape as well as a framework for positive change. Our ingenuity and grace continues to impress me. It makes me more optimistic about humanity.

Brad Temkin (USA, 1956). Has been documenting the human impact on the landscape. He has exhibited his photographs in museums and galleries throughout the United States and abroad. Temkin’s works are included in numerous permanent collections, including those of The Art Institute of Chicago; Milwaukee Art Museum; Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.; Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; Akron Art Museum, Ohio; and Museum of Contemporary Photography, Chicago, among others. His images have appeared in such publications as Aperture, Black & White Magazine, TIME Magazine and European Photography.

Brad Temkin (USA, 1956). Has been documenting the human impact on the landscape. He has exhibited his photographs in museums and galleries throughout the United States and abroad. Temkin’s works are included in numerous permanent collections, including those of The Art Institute of Chicago; Milwaukee Art Museum; Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.; Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; Akron Art Museum, Ohio; and Museum of Contemporary Photography, Chicago, among others. His images have appeared in such publications as Aperture, Black & White Magazine, TIME Magazine and European Photography.

Most of my career has focused on our relationship with nature. I’m interested in how we find ways to accommodate nature, and how it accommodates us. As with most bodies of work, the pictures define my intent. But in the end, I make the pictures I do because of the conversation that occurs between the subject and myself - and this always depends on the light, the weather, how I'm feeling and what I am open to seeing at the moment. It's the moment all things come together for me.

Rooftop draws poetic attention to celebrate and proliferate new ideas in design showing the inventiveness in architecture and accommodating our need for nature. Green roofs reduce our carbon footprint by countering heat island effect and improve storm water control, but they do far more. These pictures symbolize the allure of nature in the face of our continuing urban sprawl. By securely situating the gardens within the steel, stone, and glass rectangularity of urban and industrial buildings, I ask viewers to revel in the far more open patterns, colors, and connection to the sky; and how they become part of a new landscape as well as a framework for positive change. Our ingenuity and grace continues to impress me. It makes me more optimistic about humanity.

Brad Temkin (USA, 1956). Has been documenting the human impact on the landscape. He has exhibited his photographs in museums and galleries throughout the United States and abroad. Temkin’s works are included in numerous permanent collections, including those of The Art Institute of Chicago; Milwaukee Art Museum; Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.; Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; Akron Art Museum, Ohio; and Museum of Contemporary Photography, Chicago, among others. His images have appeared in such publications as Aperture, Black & White Magazine, TIME Magazine and European Photography.

Brad Temkin (USA, 1956). Has been documenting the human impact on the landscape. He has exhibited his photographs in museums and galleries throughout the United States and abroad. Temkin’s works are included in numerous permanent collections, including those of The Art Institute of Chicago; Milwaukee Art Museum; Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.; Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; Akron Art Museum, Ohio; and Museum of Contemporary Photography, Chicago, among others. His images have appeared in such publications as Aperture, Black & White Magazine, TIME Magazine and European Photography.Barbara Ciurej & Lindsay Lochman

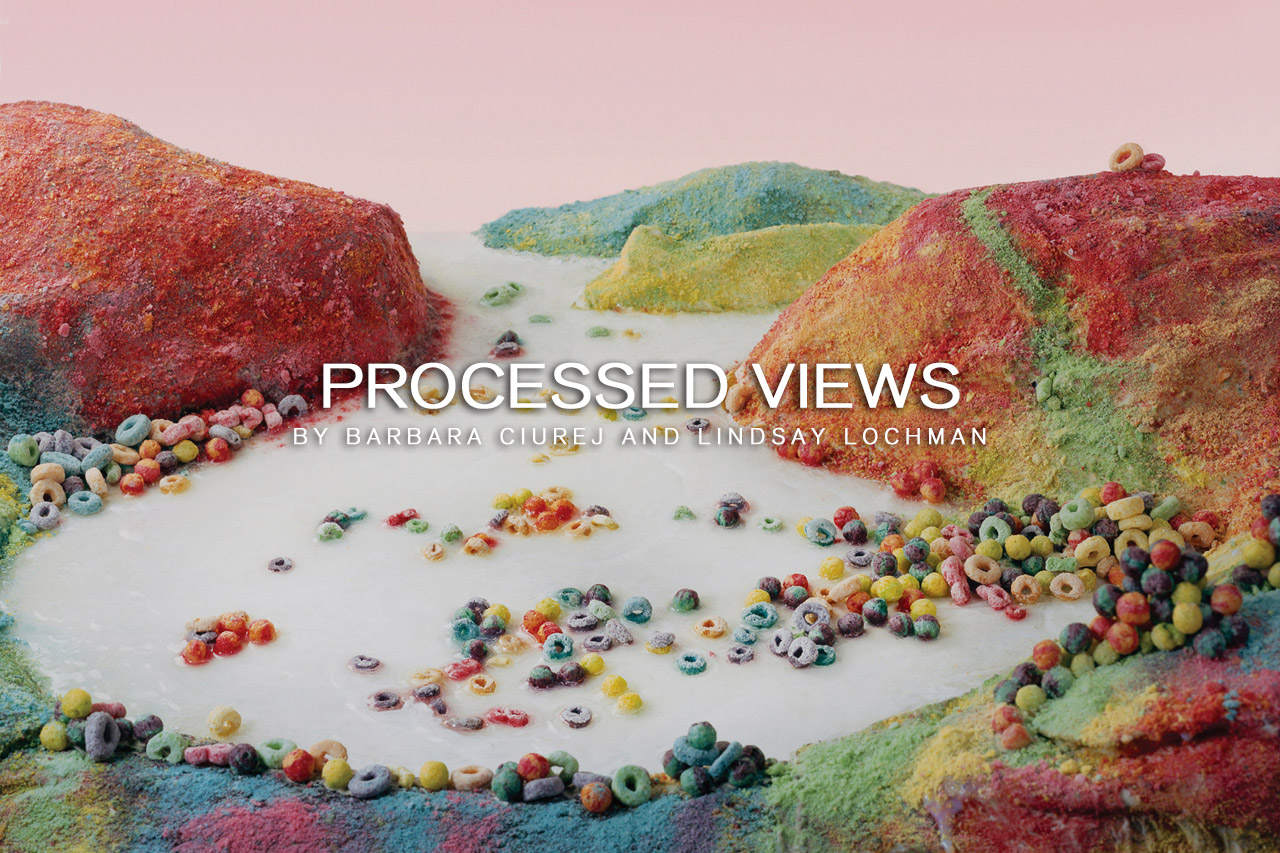

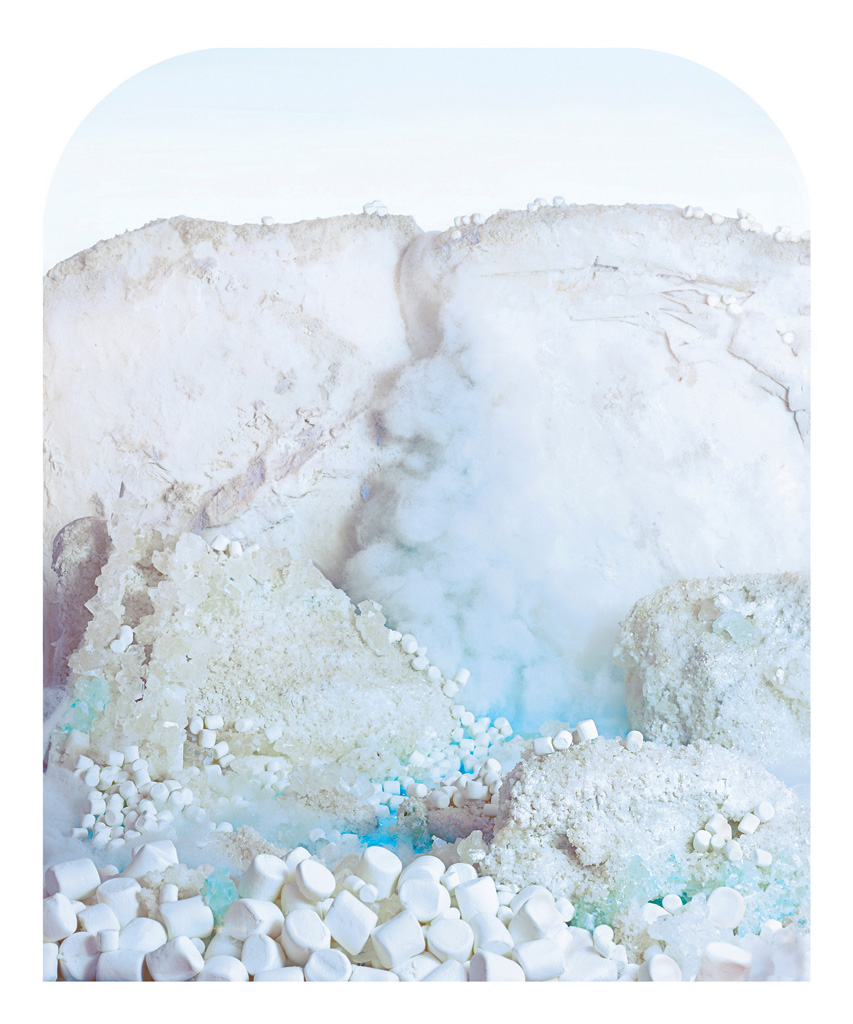

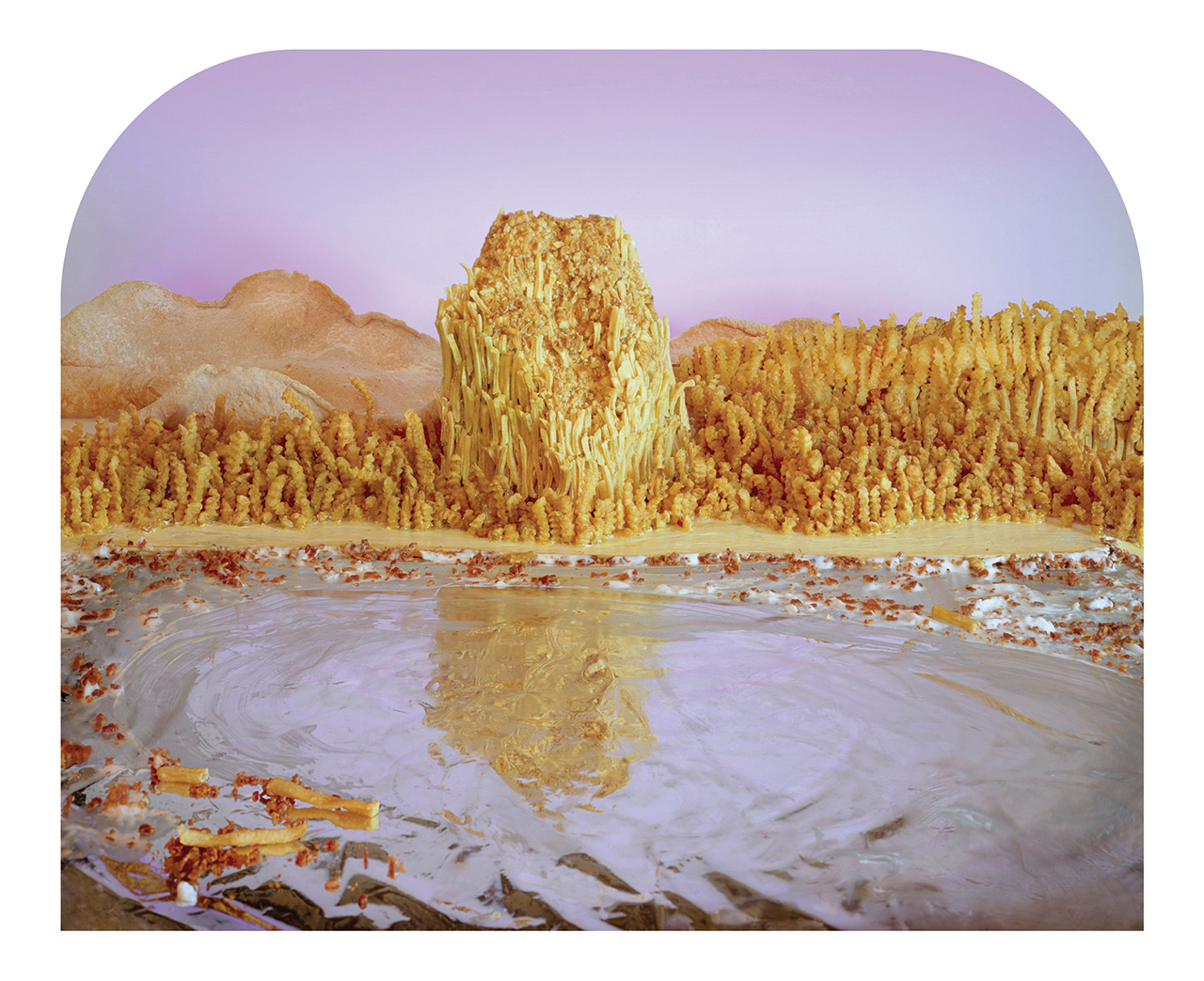

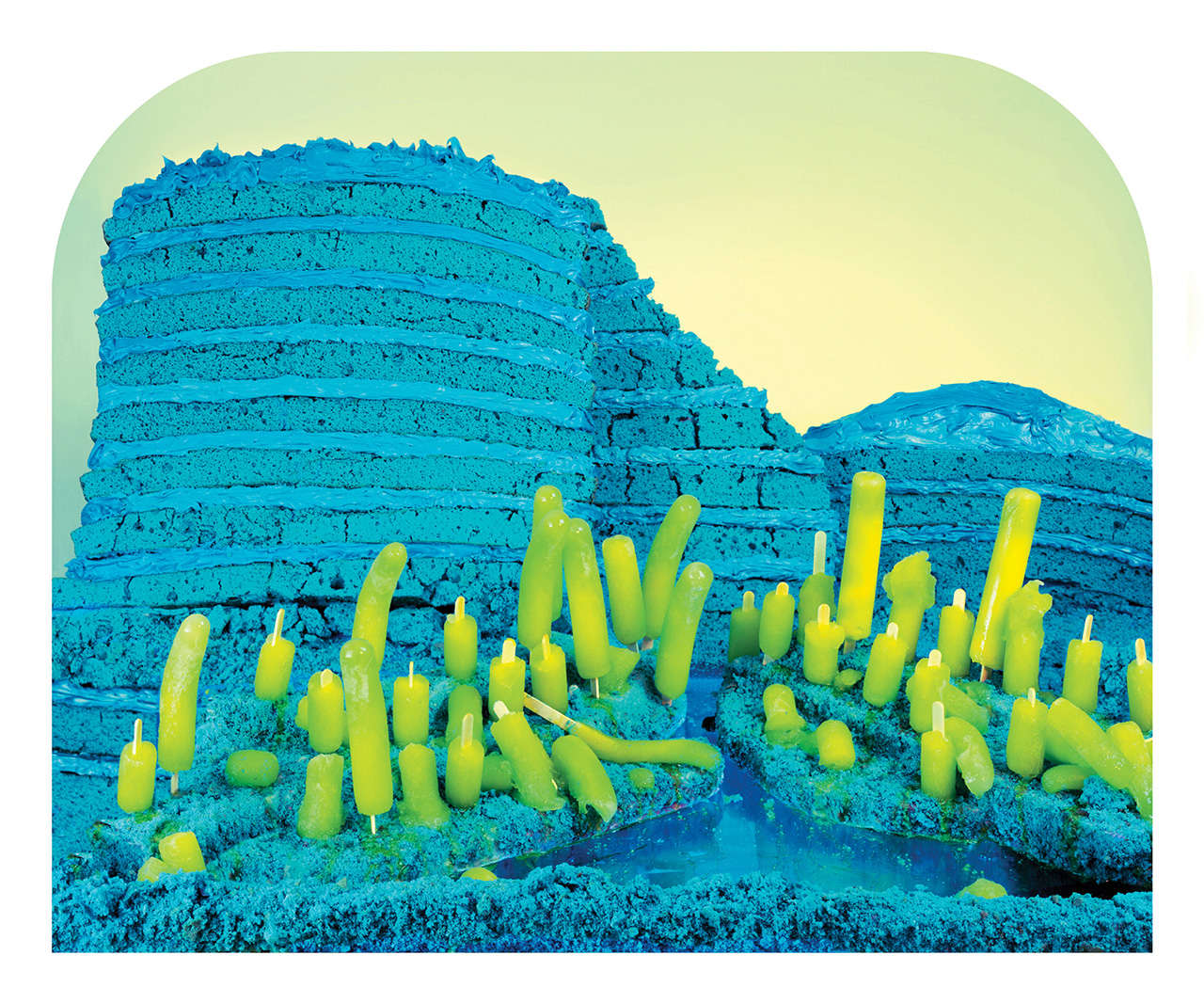

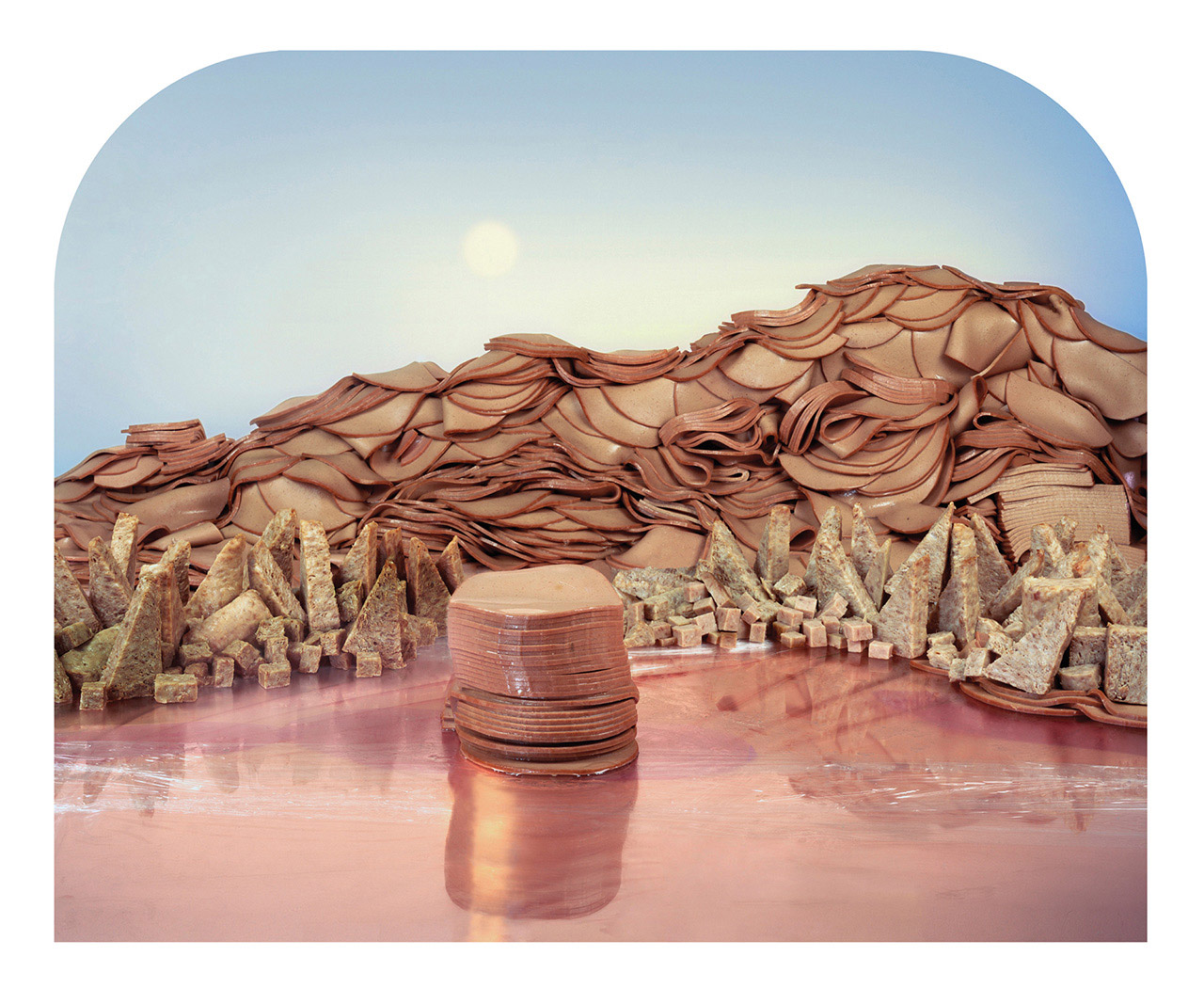

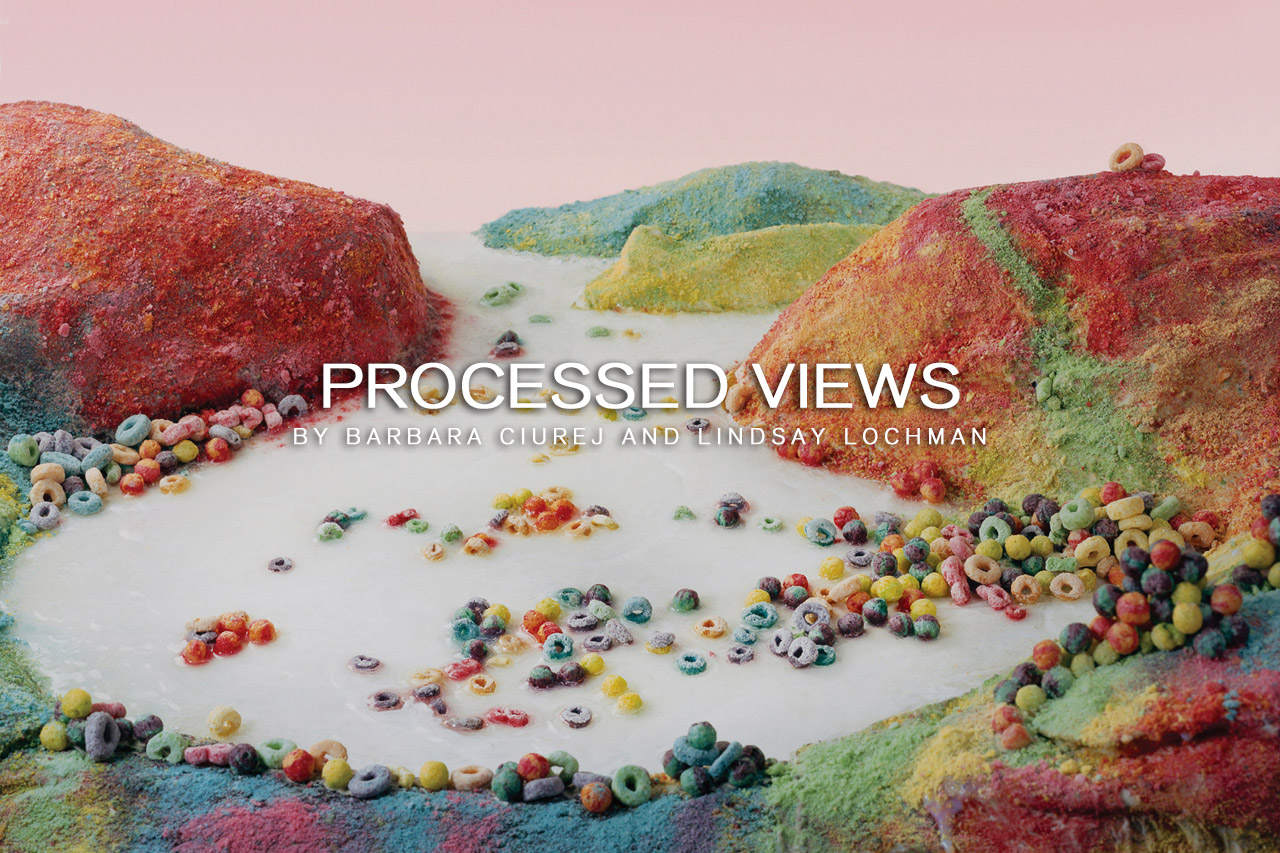

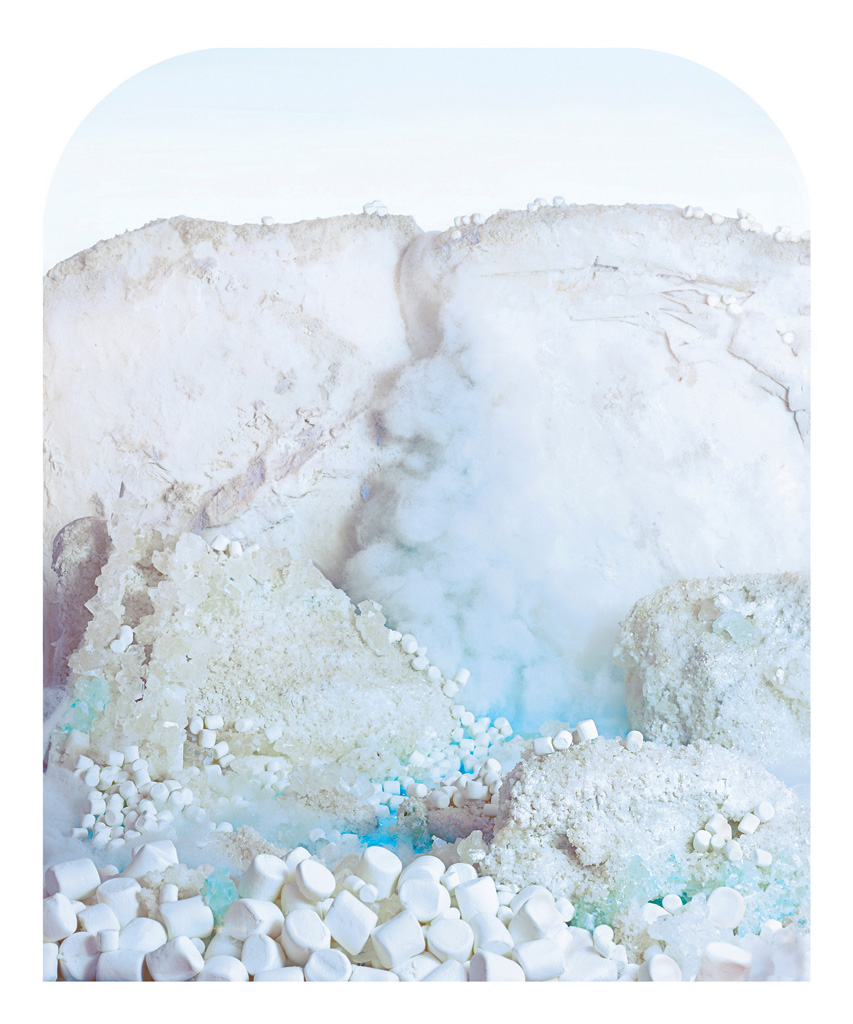

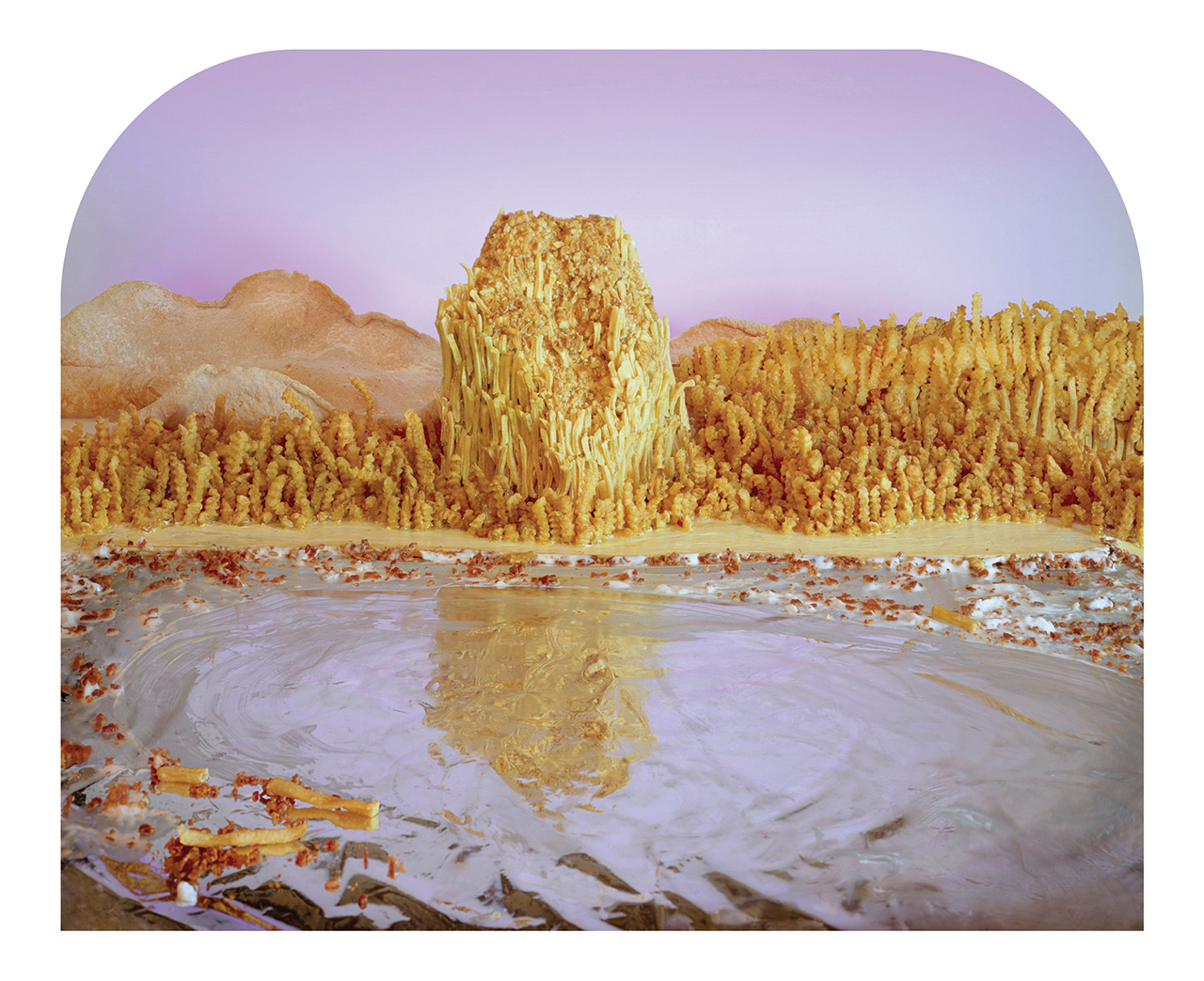

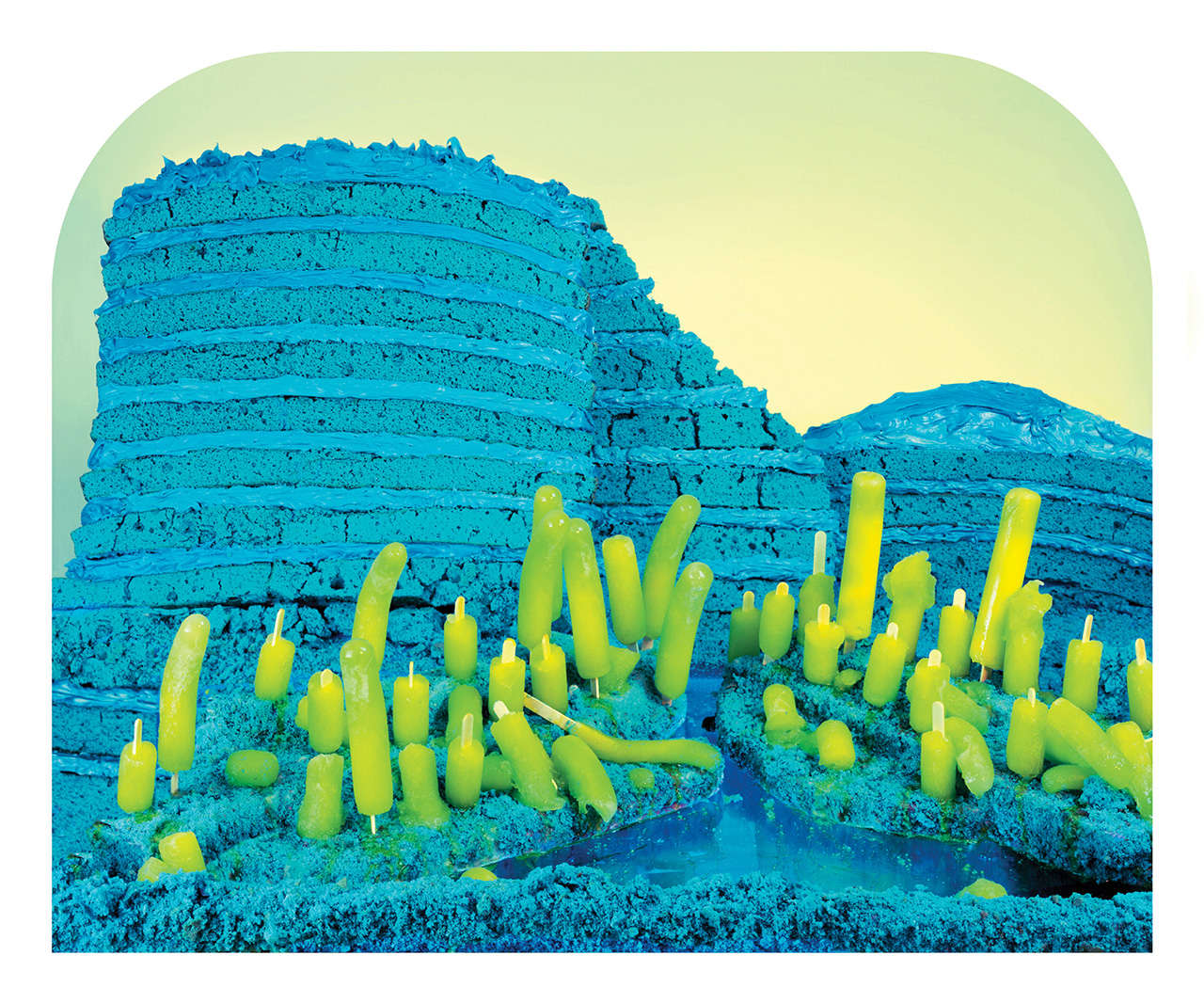

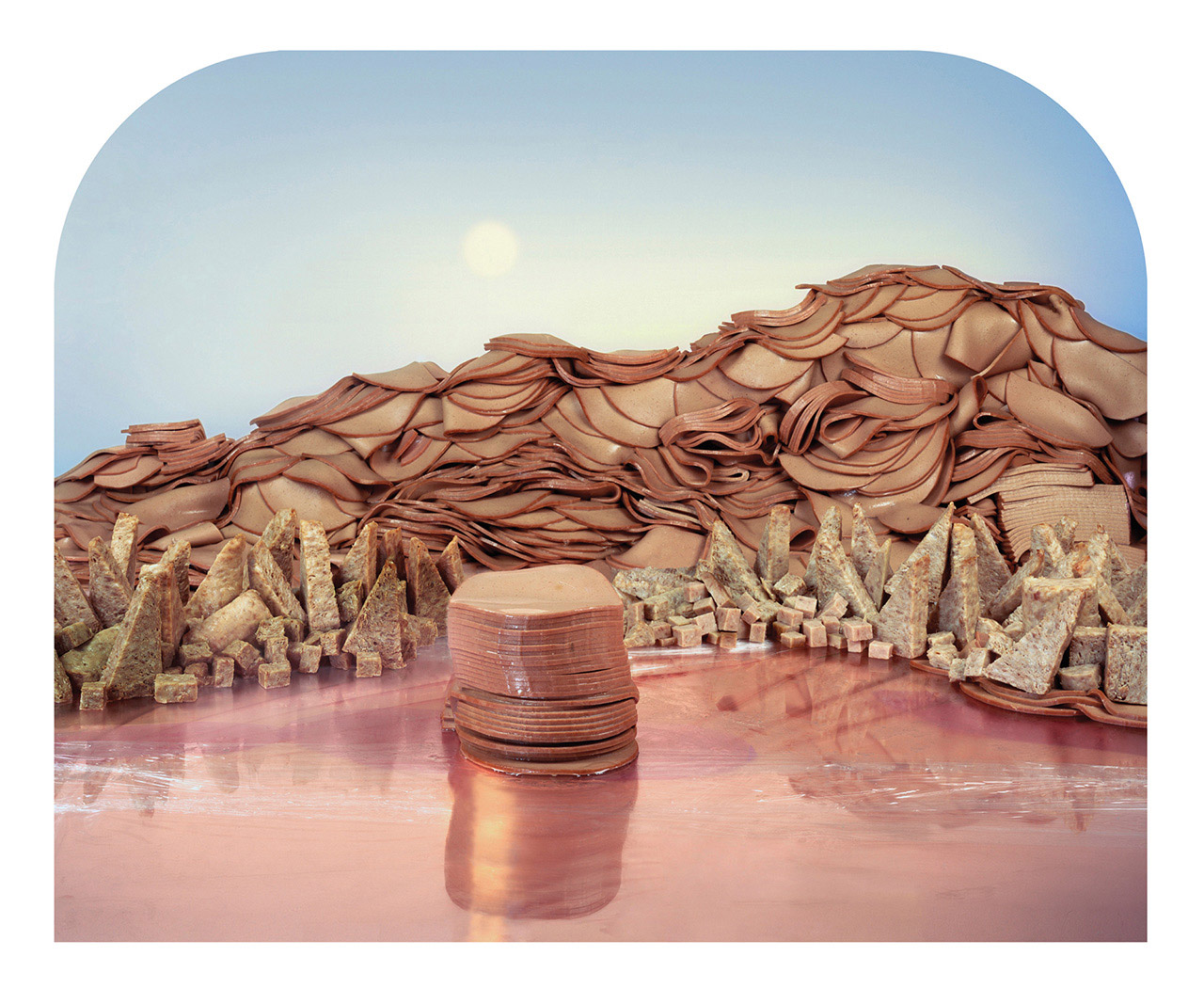

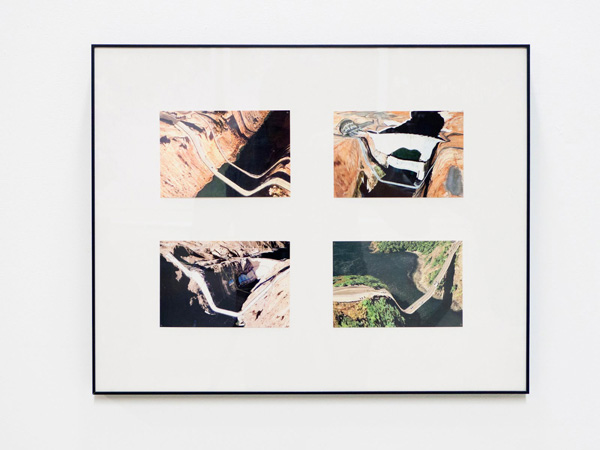

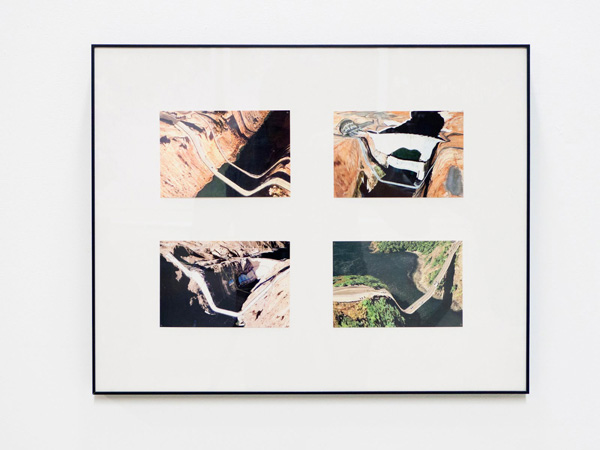

Processed Views interprets the frontier of industrial food production: the seductive and alarming intersection of nature and technology. As we move further away from the sources of our food, we head into uncharted territory replete with unintended consequences for the environment and for our health.

In our commentary on the landscape of processed foods, we reference the work of photographer, Carleton Watkins (1829-1916). His sublime views framed the American West as a land of endless possibilities and significantly influenced the creation of the first national parks. However, many of Watkins’ photographs were commissioned by the corporate interests of the day; the railroad, mining, lumber and milling companies. His commissions served as both documentation of and advertisement for the American West. Watkins’ views expessed the popular 19th century notion of Manifest Destiny – America’s bountiful land, inevitably and justifiably utilized by its citizens.

We built these views to examine consumption, progress and the changing landscape.

Barbara Ciurej & Lindsay Lochman (USA). Collaborate on photographic projects that address the confluence of history, myth and popular culture. Their work has been exhibited widely and their photographs are in public and private collections including the Art Institute of Chicago, Walker Art Center, Museum of Contemporary Photography, Milwaukee Art Museum, and the Beinecke Library at Yale University. They are currently exploring the potential of constructed landscapes to describe social inequality. Processed Views is currently on view at Rick Wester Fine Art ,New York, until July 29, 2016.

Barbara Ciurej & Lindsay Lochman (USA). Collaborate on photographic projects that address the confluence of history, myth and popular culture. Their work has been exhibited widely and their photographs are in public and private collections including the Art Institute of Chicago, Walker Art Center, Museum of Contemporary Photography, Milwaukee Art Museum, and the Beinecke Library at Yale University. They are currently exploring the potential of constructed landscapes to describe social inequality. Processed Views is currently on view at Rick Wester Fine Art ,New York, until July 29, 2016.

Processed Views interprets the frontier of industrial food production: the seductive and alarming intersection of nature and technology. As we move further away from the sources of our food, we head into uncharted territory replete with unintended consequences for the environment and for our health.

In our commentary on the landscape of processed foods, we reference the work of photographer, Carleton Watkins (1829-1916). His sublime views framed the American West as a land of endless possibilities and significantly influenced the creation of the first national parks. However, many of Watkins’ photographs were commissioned by the corporate interests of the day; the railroad, mining, lumber and milling companies. His commissions served as both documentation of and advertisement for the American West. Watkins’ views expessed the popular 19th century notion of Manifest Destiny – America’s bountiful land, inevitably and justifiably utilized by its citizens.

We built these views to examine consumption, progress and the changing landscape.

Barbara Ciurej & Lindsay Lochman (USA). Collaborate on photographic projects that address the confluence of history, myth and popular culture. Their work has been exhibited widely and their photographs are in public and private collections including the Art Institute of Chicago, Walker Art Center, Museum of Contemporary Photography, Milwaukee Art Museum, and the Beinecke Library at Yale University. They are currently exploring the potential of constructed landscapes to describe social inequality. Processed Views is currently on view at Rick Wester Fine Art ,New York, until July 29, 2016.

Barbara Ciurej & Lindsay Lochman (USA). Collaborate on photographic projects that address the confluence of history, myth and popular culture. Their work has been exhibited widely and their photographs are in public and private collections including the Art Institute of Chicago, Walker Art Center, Museum of Contemporary Photography, Milwaukee Art Museum, and the Beinecke Library at Yale University. They are currently exploring the potential of constructed landscapes to describe social inequality. Processed Views is currently on view at Rick Wester Fine Art ,New York, until July 29, 2016.Liz Hickok

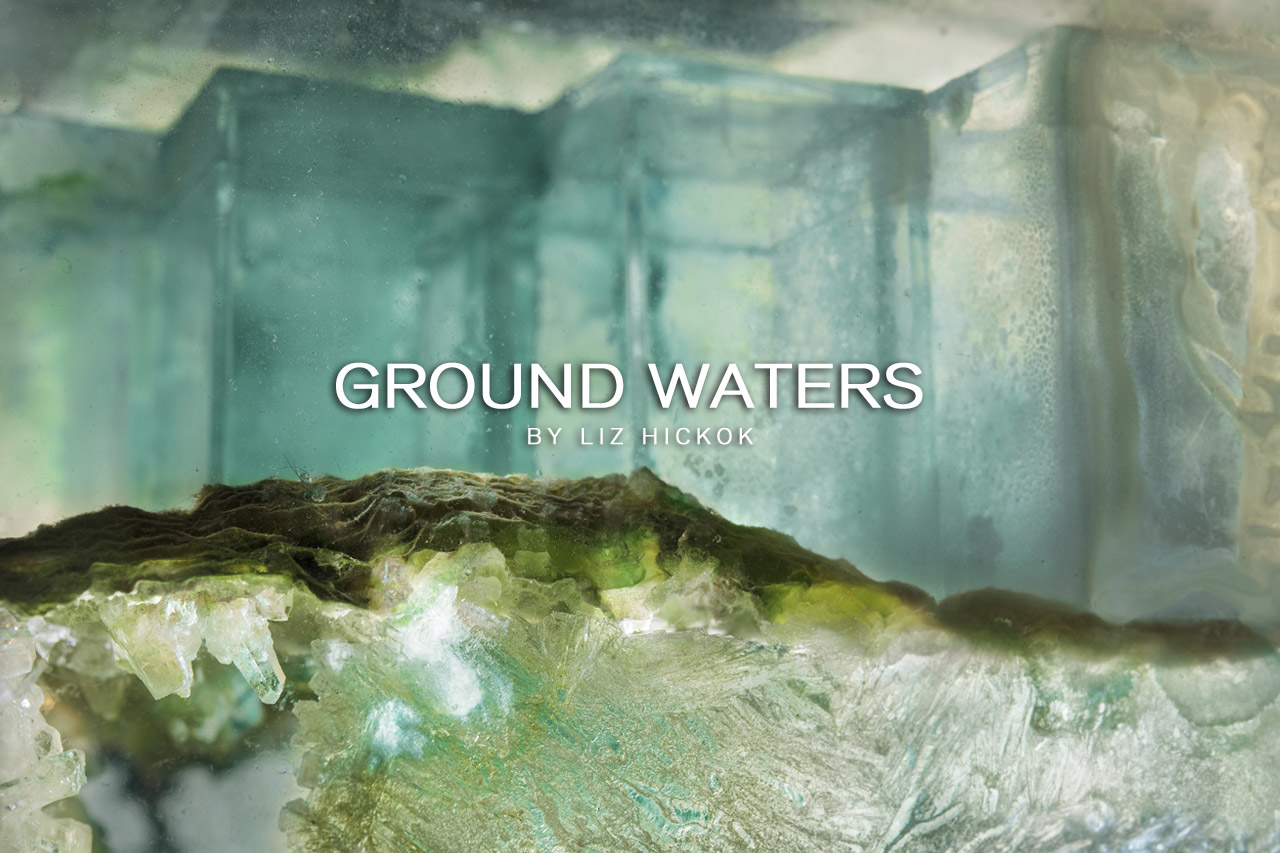

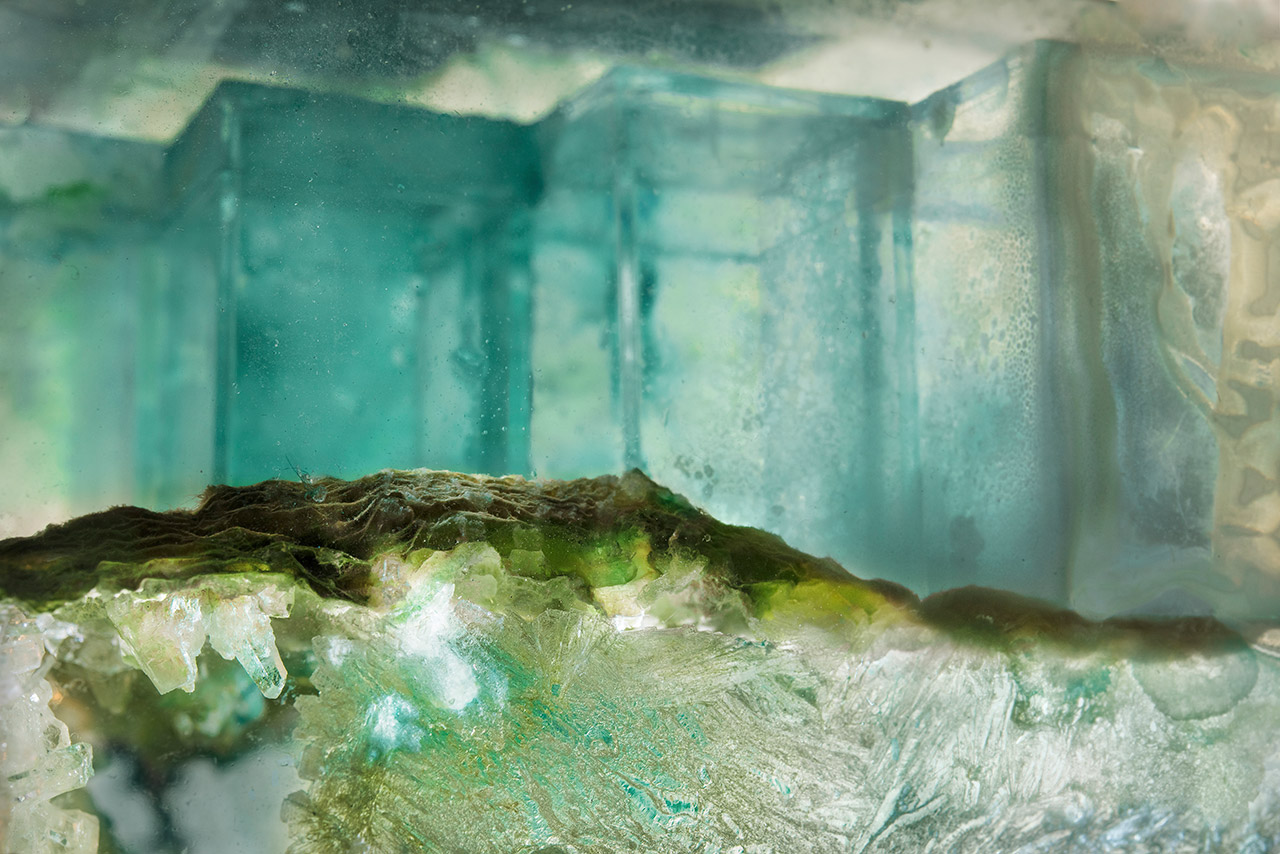

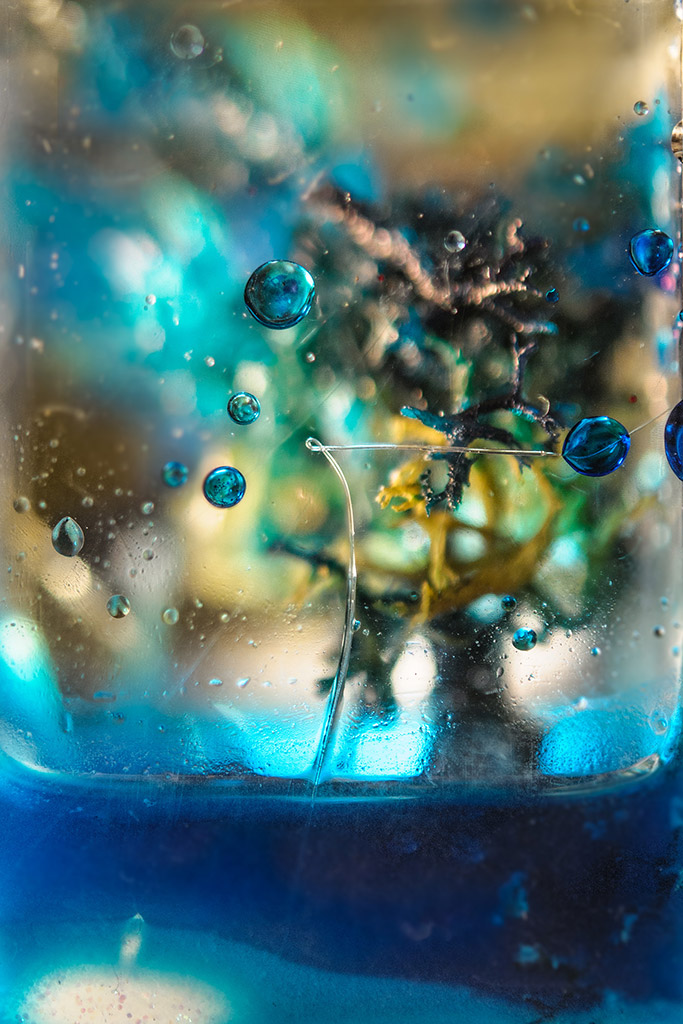

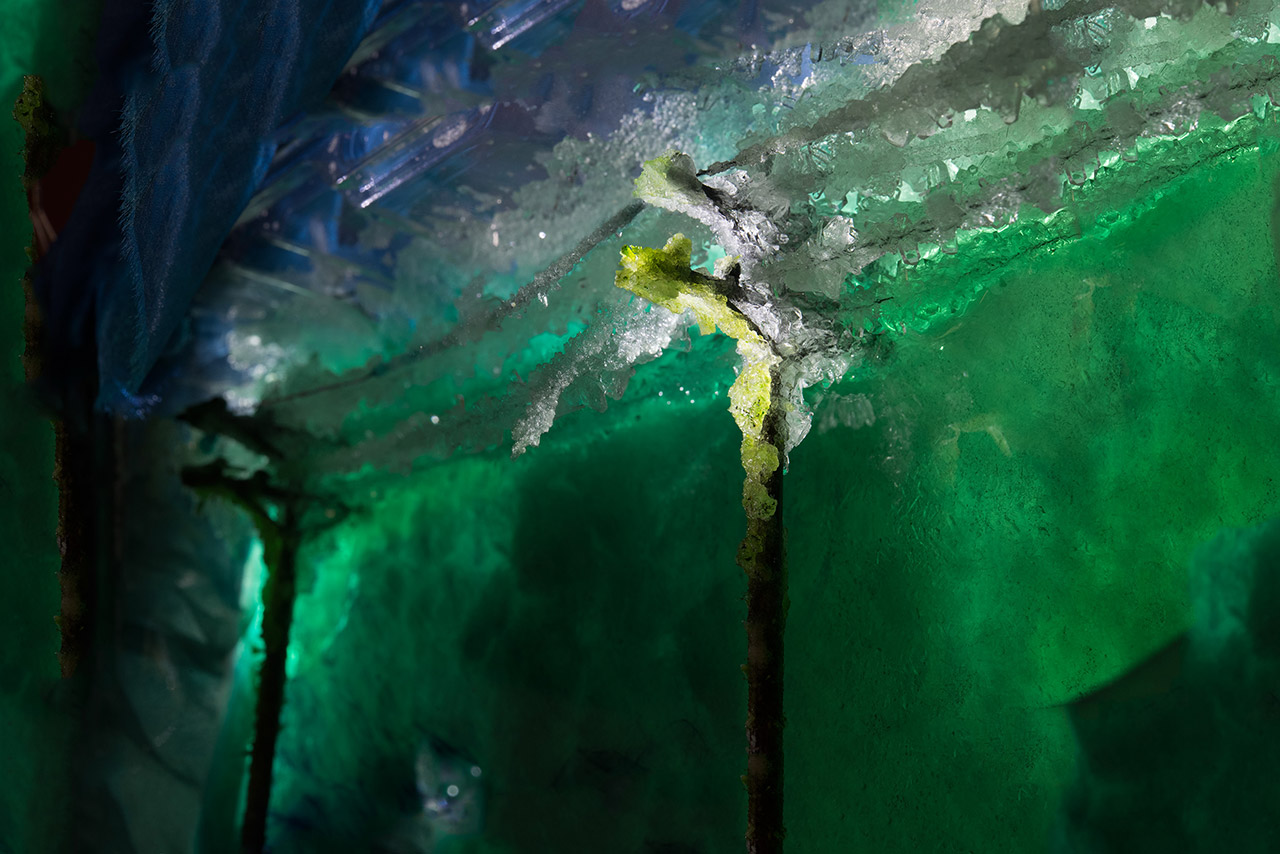

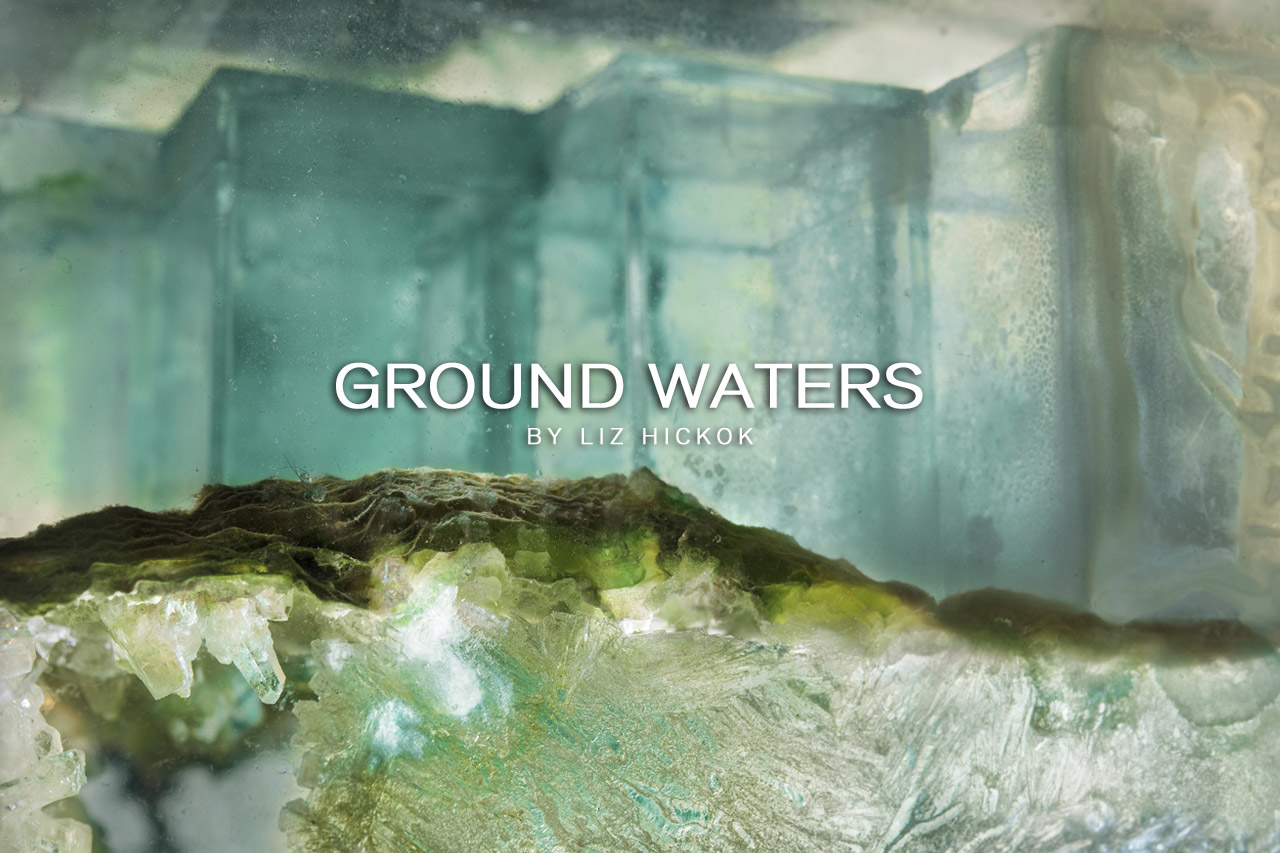

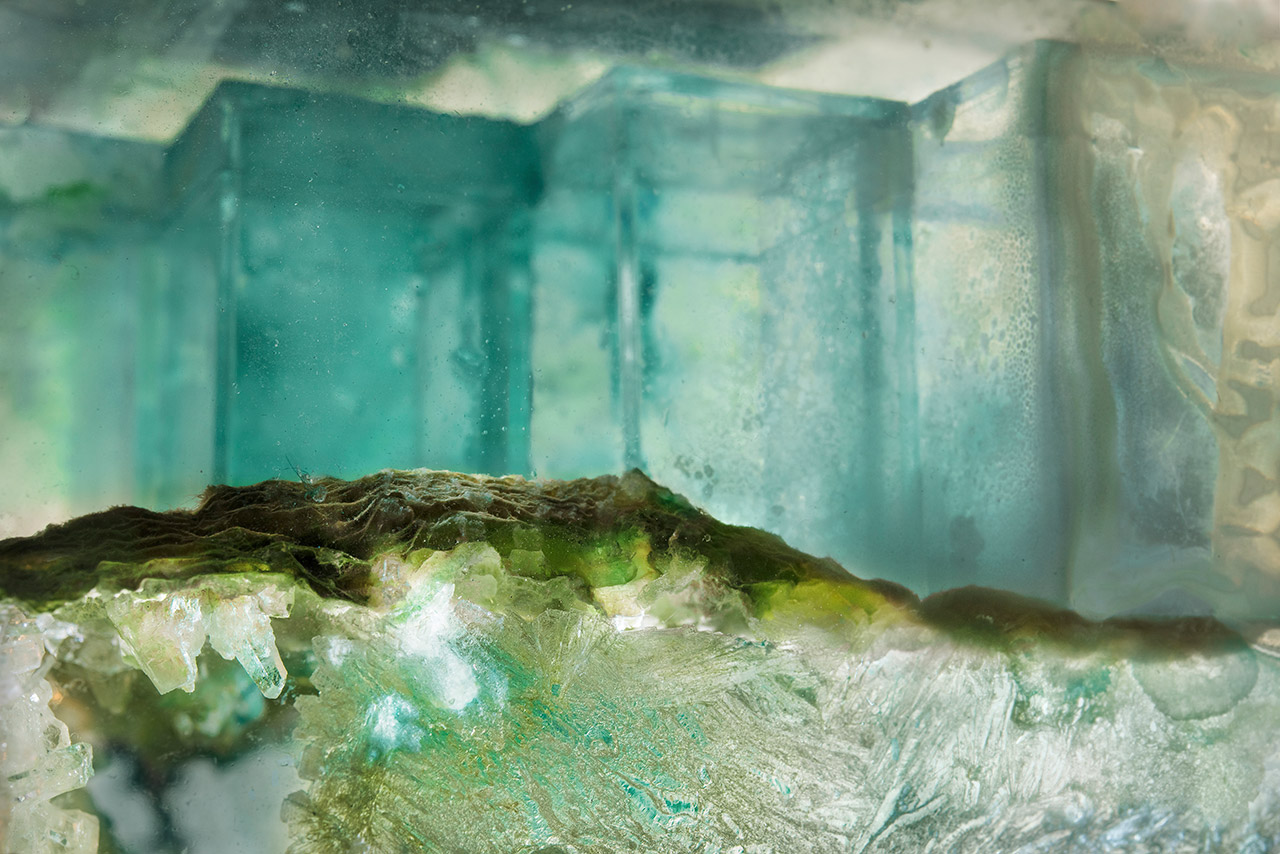

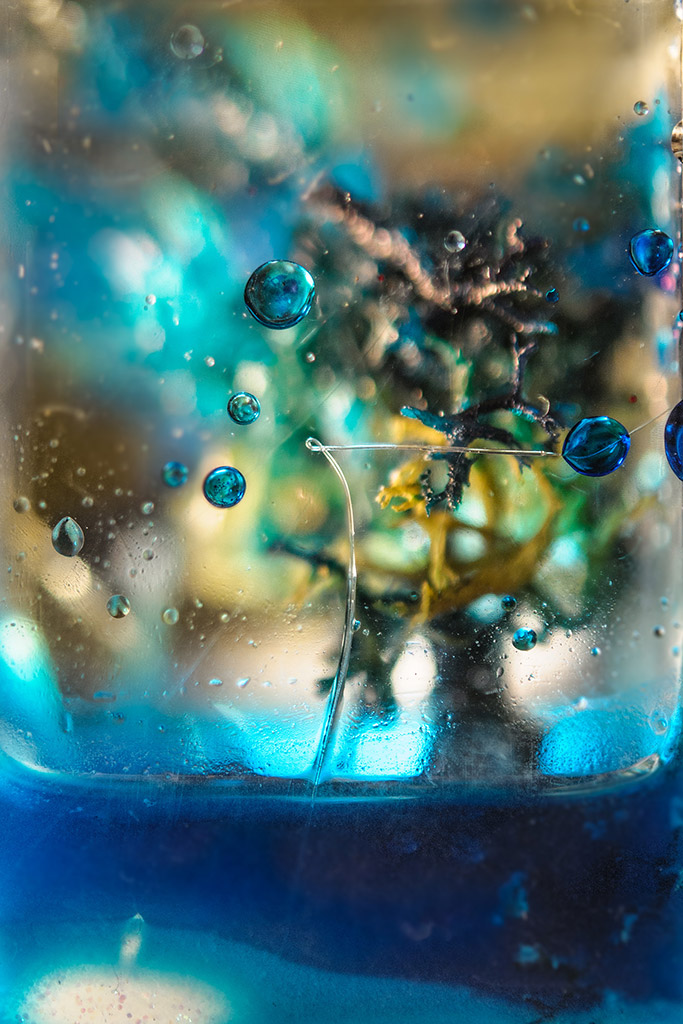

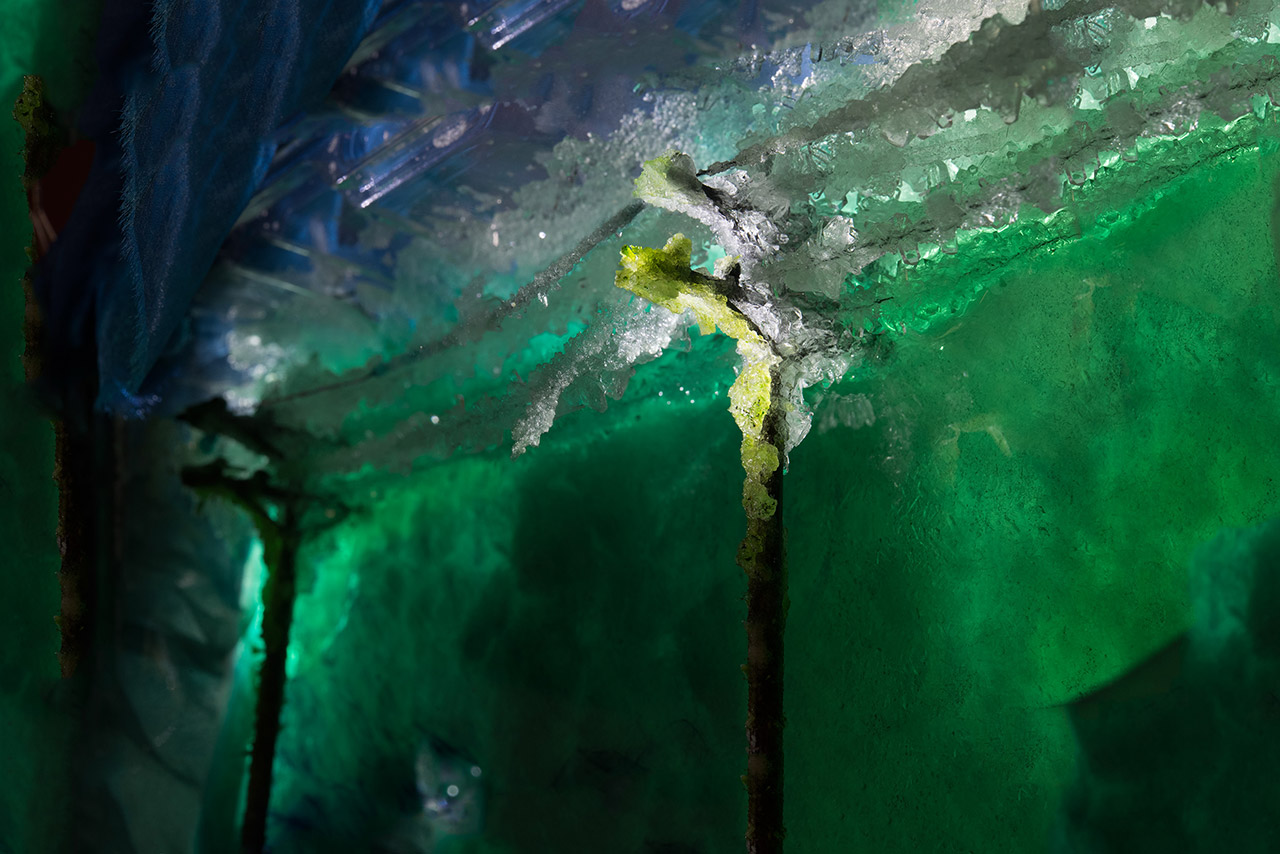

In my Ground Waters series I create miniature worlds where both natural and urban environments are overgrown by strange crystal formations. The colorful tableaux are playful in their materials, but they also allude to our environment being saturated by pollution.

I assemble and combine various elements, like a science experiment, and then I flood the scene with a liquid crystal solution. Over the course of a few hours, days, or weeks, the crystals re-form, permeating the small model. I enjoy the conflicting processes of control and lack thereof.

Liz Hickok (USA). artist working in photography, video, sculpture, and installation. Hickok received her Masters in Fine Arts from Mills College in Oakland, California. She earned a BFA and BA from the School of the Museum of Fine Arts and Tufts University in Boston, Massachusetts. Hickok lived and worked in Boston for over ten years before moving to the San Francisco Bay Area.

Liz Hickok (USA). artist working in photography, video, sculpture, and installation. Hickok received her Masters in Fine Arts from Mills College in Oakland, California. She earned a BFA and BA from the School of the Museum of Fine Arts and Tufts University in Boston, Massachusetts. Hickok lived and worked in Boston for over ten years before moving to the San Francisco Bay Area.

In my Ground Waters series I create miniature worlds where both natural and urban environments are overgrown by strange crystal formations. The colorful tableaux are playful in their materials, but they also allude to our environment being saturated by pollution.

I assemble and combine various elements, like a science experiment, and then I flood the scene with a liquid crystal solution. Over the course of a few hours, days, or weeks, the crystals re-form, permeating the small model. I enjoy the conflicting processes of control and lack thereof.

Liz Hickok (USA). artist working in photography, video, sculpture, and installation. Hickok received her Masters in Fine Arts from Mills College in Oakland, California. She earned a BFA and BA from the School of the Museum of Fine Arts and Tufts University in Boston, Massachusetts. Hickok lived and worked in Boston for over ten years before moving to the San Francisco Bay Area.

Liz Hickok (USA). artist working in photography, video, sculpture, and installation. Hickok received her Masters in Fine Arts from Mills College in Oakland, California. She earned a BFA and BA from the School of the Museum of Fine Arts and Tufts University in Boston, Massachusetts. Hickok lived and worked in Boston for over ten years before moving to the San Francisco Bay Area.Rebecca Reeve

The miracle of light pours over the green and brown expanse of saw grass and of water, shining and slowly moving, the grass and the water that is the meaning and the central fact of the Everglades. It is a river of grass. —Marjory Stoneman Douglas

I began this series during my AIRIE residency in the Everglades in December 2012. It draws inspiration from a ritual described in The Rings of Saturn by W.G. Sebald. In Holland in the 1600s, during the wake of the deceased, it was customary to cover all mirrors, landscape paintings and portraits in the home with cloths. It was believed this would make it easier for the soul to leave the body and subdue any temptations for it to stay in this world.

The ritual seemed, by extension, to be a confirmation of the deeply moving experience that one often feels in the natural environment, and thus provided both a literal and contextual frame within which to shoot the landscape, a portal from the domestic into the wilderness. The curtains, all purchased from Goodwill and Salvation Army stores in south Florida and Utah, represent a ‘social fabric’ with a history already attached to them. In our increasingly urban existence that ever distances us from the wilderness experience, the drapes serve as visual connectors to the familiar.

Images from the Marjory's World series will be on show in the exhibition 'Mise en Scene' opening March 16th at Hazan Projects in New York City.

Rebecca Reeve (England) She received her Bachelor of Fine Arts degree at Bath Spa University and a Masters of Visual Arts at the University of South Wales, Australia. Her photographs have been exhibited nationally and internationally including La Biennale de Montreal, (Canada), Freies Museum, Berlin, (Germany), Museum of Latin American Art, (Buenos Aires), EFA Project Space, (NYC) and the Masur Museum of Art, (Louisiana). In 2013 she was Artist in Residence at AIRIE and the recipient of the Artist in Exploration grant underwritten by Rolex. In 2016 she will be Artist in Residence at Joshua Tree National Park. She lives and works in New York City.

Rebecca Reeve (England) She received her Bachelor of Fine Arts degree at Bath Spa University and a Masters of Visual Arts at the University of South Wales, Australia. Her photographs have been exhibited nationally and internationally including La Biennale de Montreal, (Canada), Freies Museum, Berlin, (Germany), Museum of Latin American Art, (Buenos Aires), EFA Project Space, (NYC) and the Masur Museum of Art, (Louisiana). In 2013 she was Artist in Residence at AIRIE and the recipient of the Artist in Exploration grant underwritten by Rolex. In 2016 she will be Artist in Residence at Joshua Tree National Park. She lives and works in New York City.

The miracle of light pours over the green and brown expanse of saw grass and of water, shining and slowly moving, the grass and the water that is the meaning and the central fact of the Everglades. It is a river of grass. —Marjory Stoneman Douglas

I began this series during my AIRIE residency in the Everglades in December 2012. It draws inspiration from a ritual described in The Rings of Saturn by W.G. Sebald. In Holland in the 1600s, during the wake of the deceased, it was customary to cover all mirrors, landscape paintings and portraits in the home with cloths. It was believed this would make it easier for the soul to leave the body and subdue any temptations for it to stay in this world.

The ritual seemed, by extension, to be a confirmation of the deeply moving experience that one often feels in the natural environment, and thus provided both a literal and contextual frame within which to shoot the landscape, a portal from the domestic into the wilderness. The curtains, all purchased from Goodwill and Salvation Army stores in south Florida and Utah, represent a ‘social fabric’ with a history already attached to them. In our increasingly urban existence that ever distances us from the wilderness experience, the drapes serve as visual connectors to the familiar.

Images from the Marjory's World series will be on show in the exhibition 'Mise en Scene' opening March 16th at Hazan Projects in New York City.

Rebecca Reeve (England) She received her Bachelor of Fine Arts degree at Bath Spa University and a Masters of Visual Arts at the University of South Wales, Australia. Her photographs have been exhibited nationally and internationally including La Biennale de Montreal, (Canada), Freies Museum, Berlin, (Germany), Museum of Latin American Art, (Buenos Aires), EFA Project Space, (NYC) and the Masur Museum of Art, (Louisiana). In 2013 she was Artist in Residence at AIRIE and the recipient of the Artist in Exploration grant underwritten by Rolex. In 2016 she will be Artist in Residence at Joshua Tree National Park. She lives and works in New York City.

Rebecca Reeve (England) She received her Bachelor of Fine Arts degree at Bath Spa University and a Masters of Visual Arts at the University of South Wales, Australia. Her photographs have been exhibited nationally and internationally including La Biennale de Montreal, (Canada), Freies Museum, Berlin, (Germany), Museum of Latin American Art, (Buenos Aires), EFA Project Space, (NYC) and the Masur Museum of Art, (Louisiana). In 2013 she was Artist in Residence at AIRIE and the recipient of the Artist in Exploration grant underwritten by Rolex. In 2016 she will be Artist in Residence at Joshua Tree National Park. She lives and works in New York City.Jamey Stillings

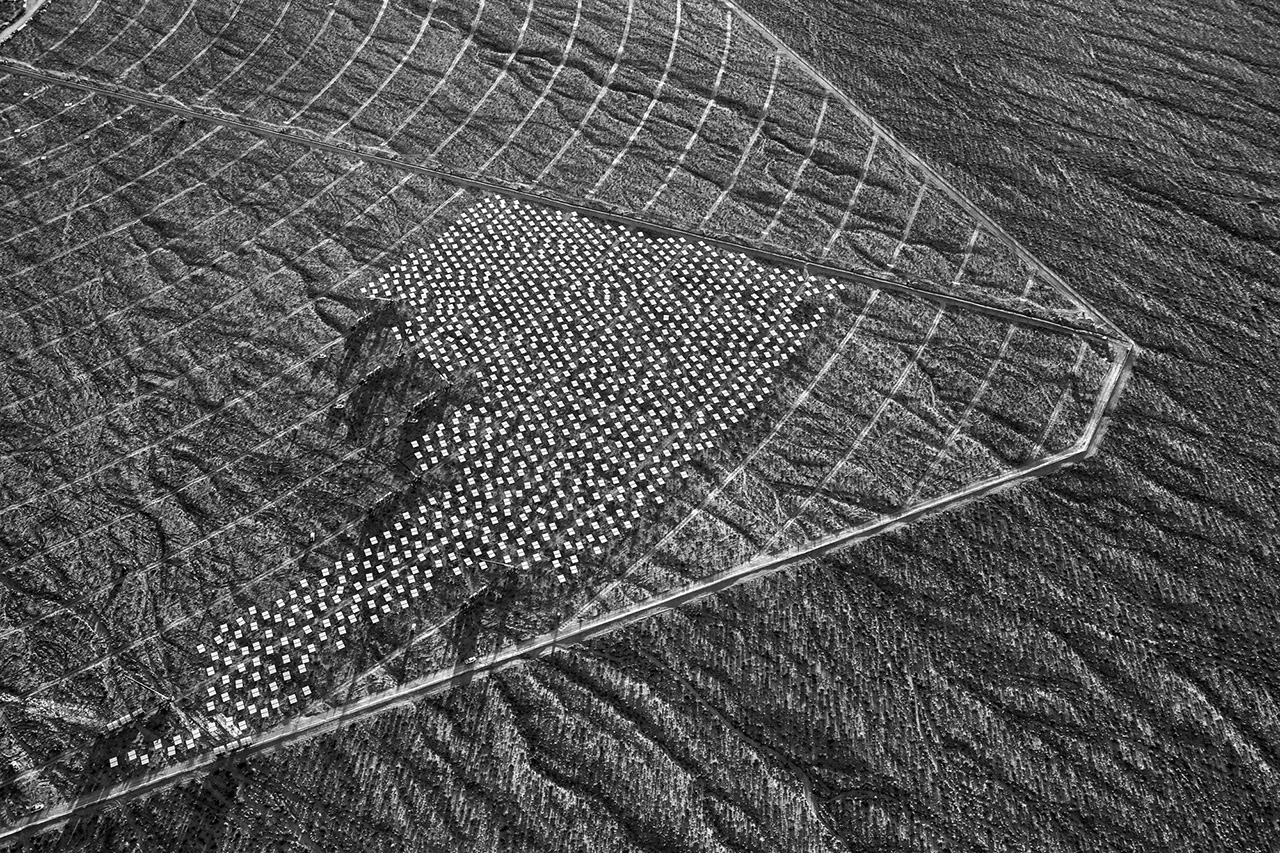

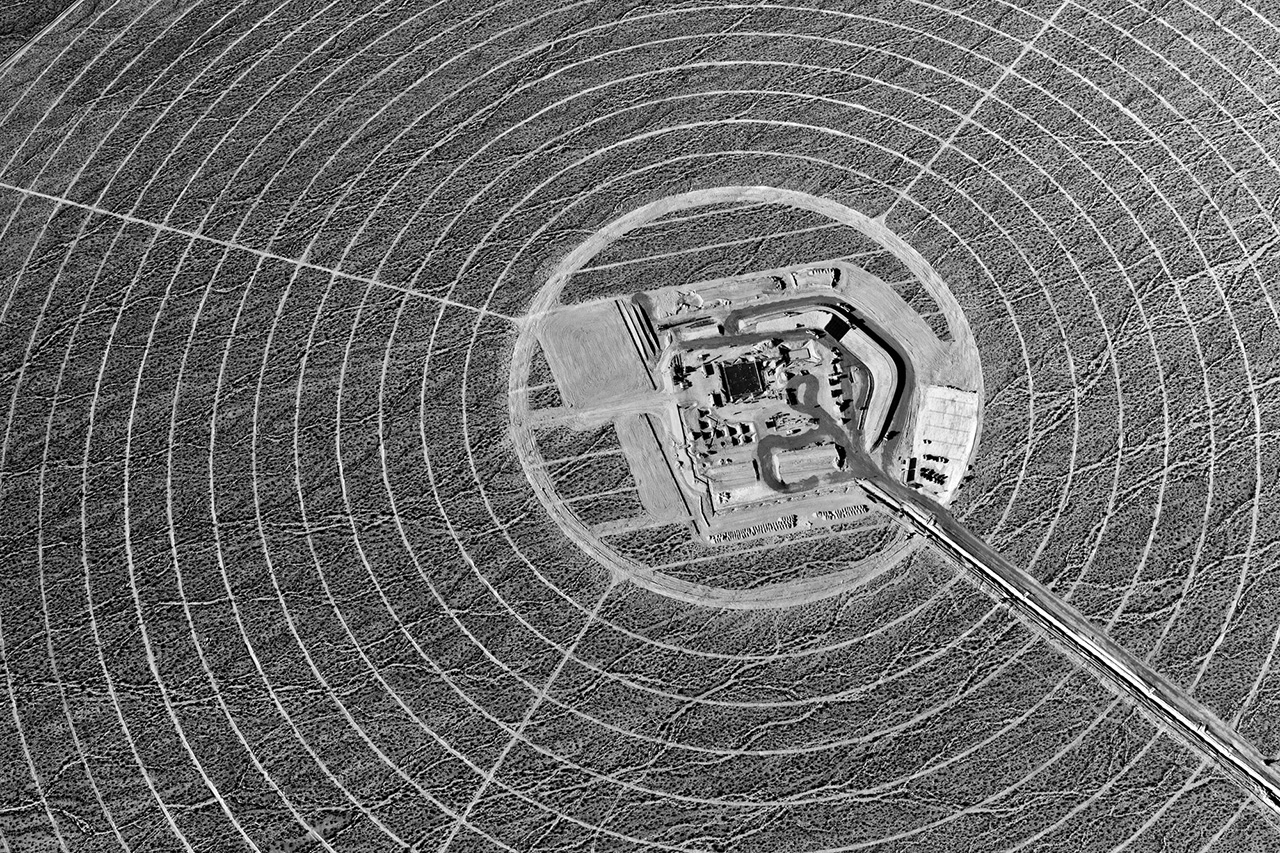

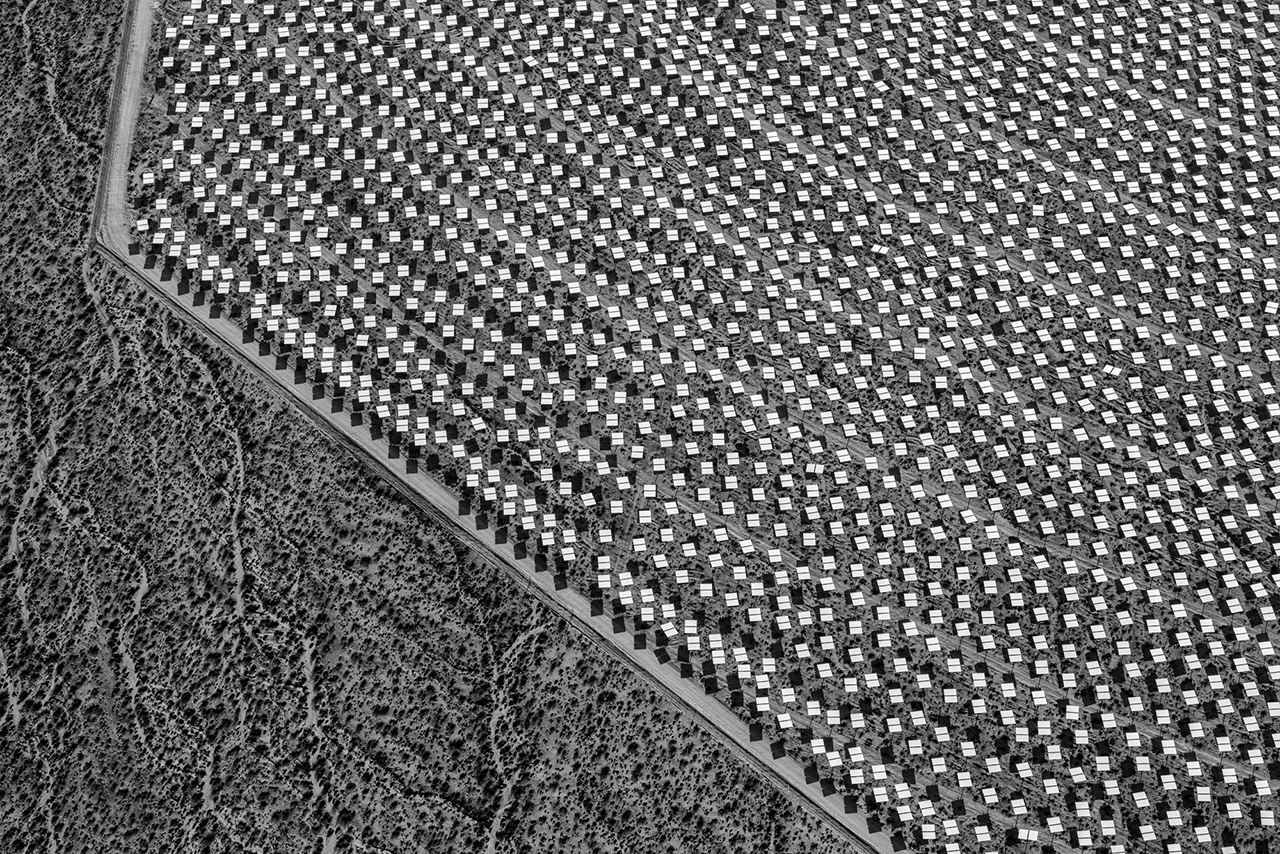

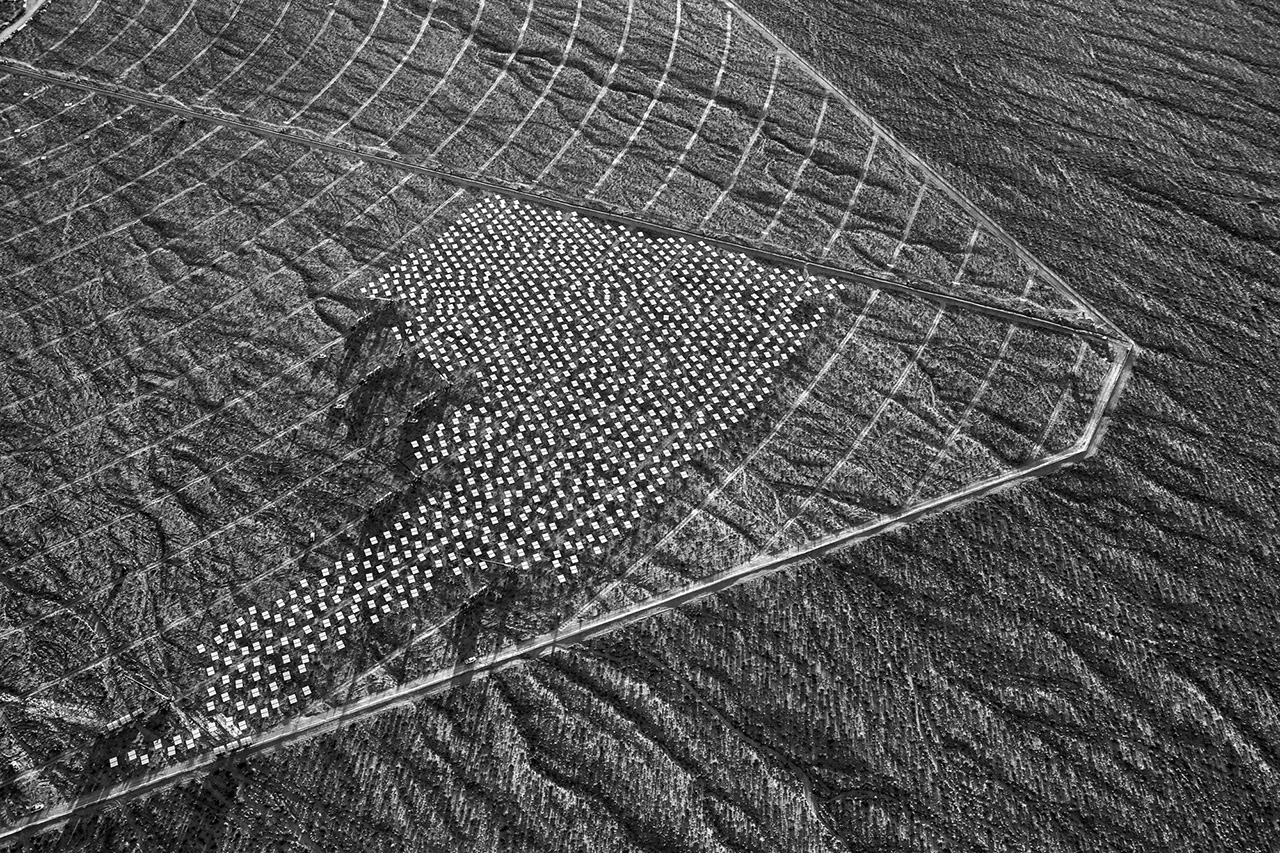

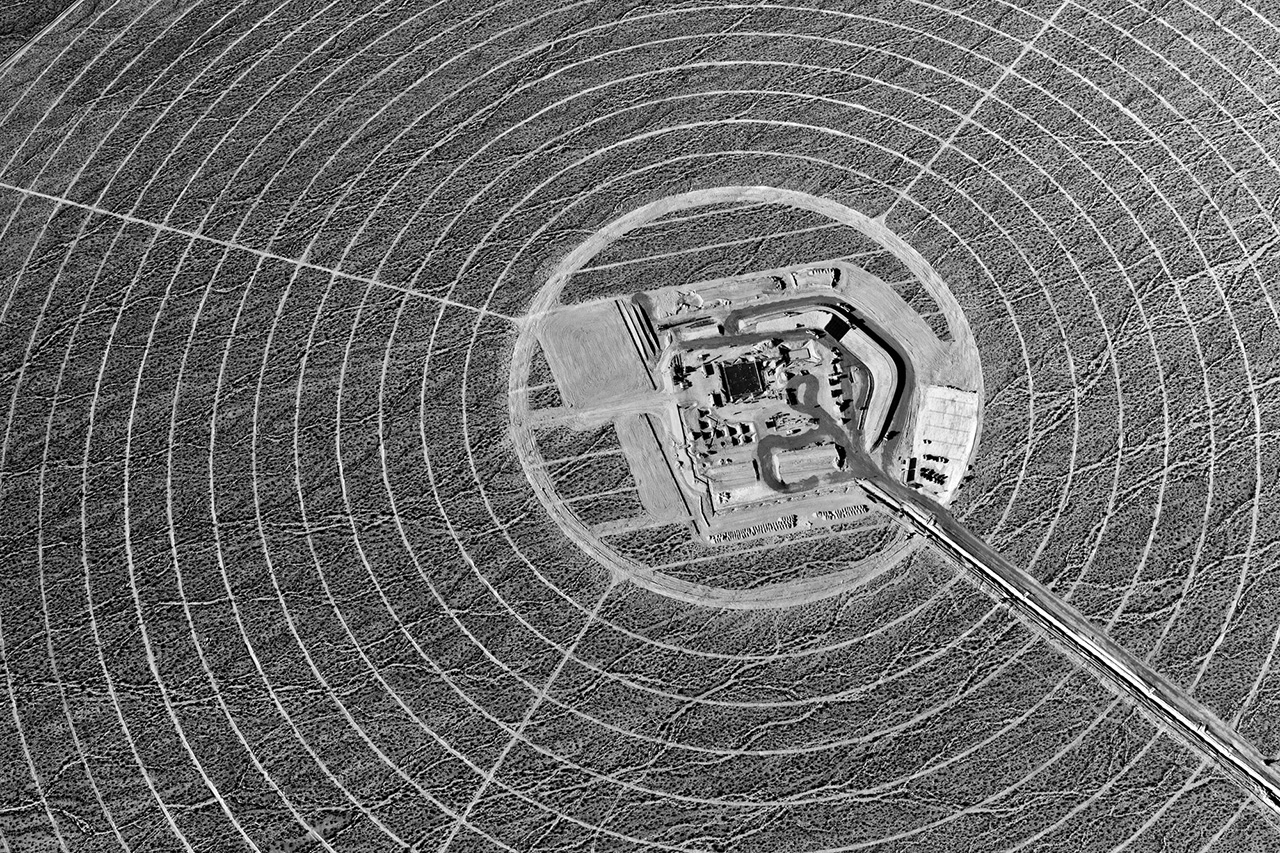

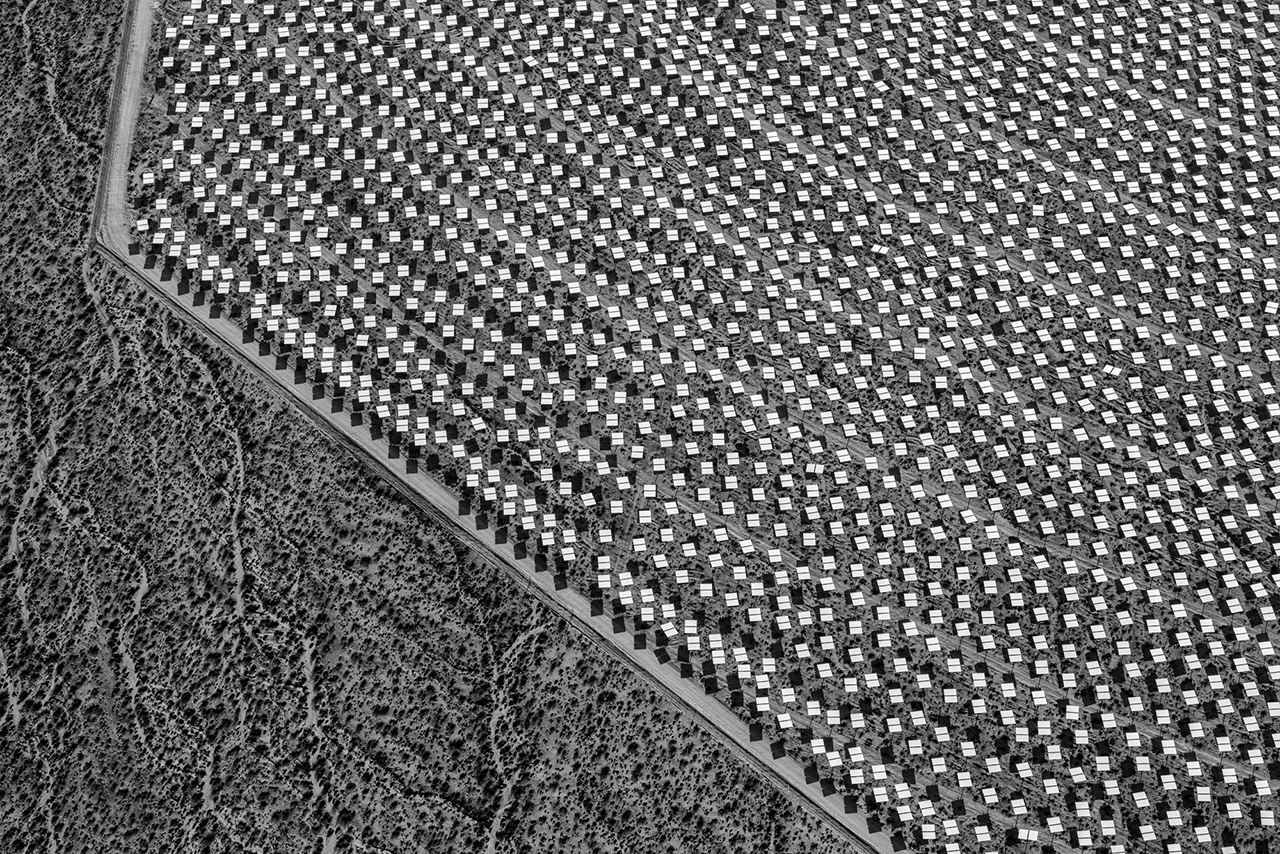

We are at a critical juncture in the evolution of our species. How we choose to live on Earth in the next few decades, with a rapidly growing human population and expanding consumption patterns, may determine not only our prospects for survival, but also the ultimate viability of Earth’s ecosystem.

I have long been intrigued by the tension and visual energy created at the nexus of nature and human activity. Uniquely as a species, we modify and use the environment for our perceived needs or enjoyment. Sometimes we consider the future consequences of our actions. More often, we focus myopically on the short-term utility of land and resource use.

Changing Perspectives is the working title for a connected set of photography projects I will engage in over the next five years. Building upon The Evolution of Ivanpah Solar, a new project, Energy in the American West, will expand my examination of utility-scale renewable energy projects in the United States, while selectively documenting domestic coal, oil, and natural gas energy production.

My primary goal, however, is to develop Changing Perspectives into a project of global scale. New renewable energy capacity is being built around the world at a remarkable pace. Projects, in many countries, on several continents, reflect a growing international commitment to transform our cultures and economies away from a dependence on fossil fuels towards a future that taps the extraordinary sustainable energy of the sun, wind, and tides. I will research and document a select group of renewable energy projects, ones that reflect a proactive commitment to future generations, while also striving to reveal the challenges and compromises such transformations frequently entail.

Jamey Stillings' career spans documentary, fine art and commercial assignment projects. He earned a BA in Art from Willamette University, an MFA in Photography from Rochester Institute of Technology, and has a diverse range of national and international commission clients. Stillings' work is in the collections of the United States Library of Congress, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Nevada Museum of Art, and several private collections.

Jamey Stillings' career spans documentary, fine art and commercial assignment projects. He earned a BA in Art from Willamette University, an MFA in Photography from Rochester Institute of Technology, and has a diverse range of national and international commission clients. Stillings' work is in the collections of the United States Library of Congress, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Nevada Museum of Art, and several private collections.

We are at a critical juncture in the evolution of our species. How we choose to live on Earth in the next few decades, with a rapidly growing human population and expanding consumption patterns, may determine not only our prospects for survival, but also the ultimate viability of Earth’s ecosystem.

I have long been intrigued by the tension and visual energy created at the nexus of nature and human activity. Uniquely as a species, we modify and use the environment for our perceived needs or enjoyment. Sometimes we consider the future consequences of our actions. More often, we focus myopically on the short-term utility of land and resource use.

Changing Perspectives is the working title for a connected set of photography projects I will engage in over the next five years. Building upon The Evolution of Ivanpah Solar, a new project, Energy in the American West, will expand my examination of utility-scale renewable energy projects in the United States, while selectively documenting domestic coal, oil, and natural gas energy production.

My primary goal, however, is to develop Changing Perspectives into a project of global scale. New renewable energy capacity is being built around the world at a remarkable pace. Projects, in many countries, on several continents, reflect a growing international commitment to transform our cultures and economies away from a dependence on fossil fuels towards a future that taps the extraordinary sustainable energy of the sun, wind, and tides. I will research and document a select group of renewable energy projects, ones that reflect a proactive commitment to future generations, while also striving to reveal the challenges and compromises such transformations frequently entail.

Jamey Stillings' career spans documentary, fine art and commercial assignment projects. He earned a BA in Art from Willamette University, an MFA in Photography from Rochester Institute of Technology, and has a diverse range of national and international commission clients. Stillings' work is in the collections of the United States Library of Congress, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Nevada Museum of Art, and several private collections.

Jamey Stillings' career spans documentary, fine art and commercial assignment projects. He earned a BA in Art from Willamette University, an MFA in Photography from Rochester Institute of Technology, and has a diverse range of national and international commission clients. Stillings' work is in the collections of the United States Library of Congress, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Nevada Museum of Art, and several private collections.Peter Steinhauer

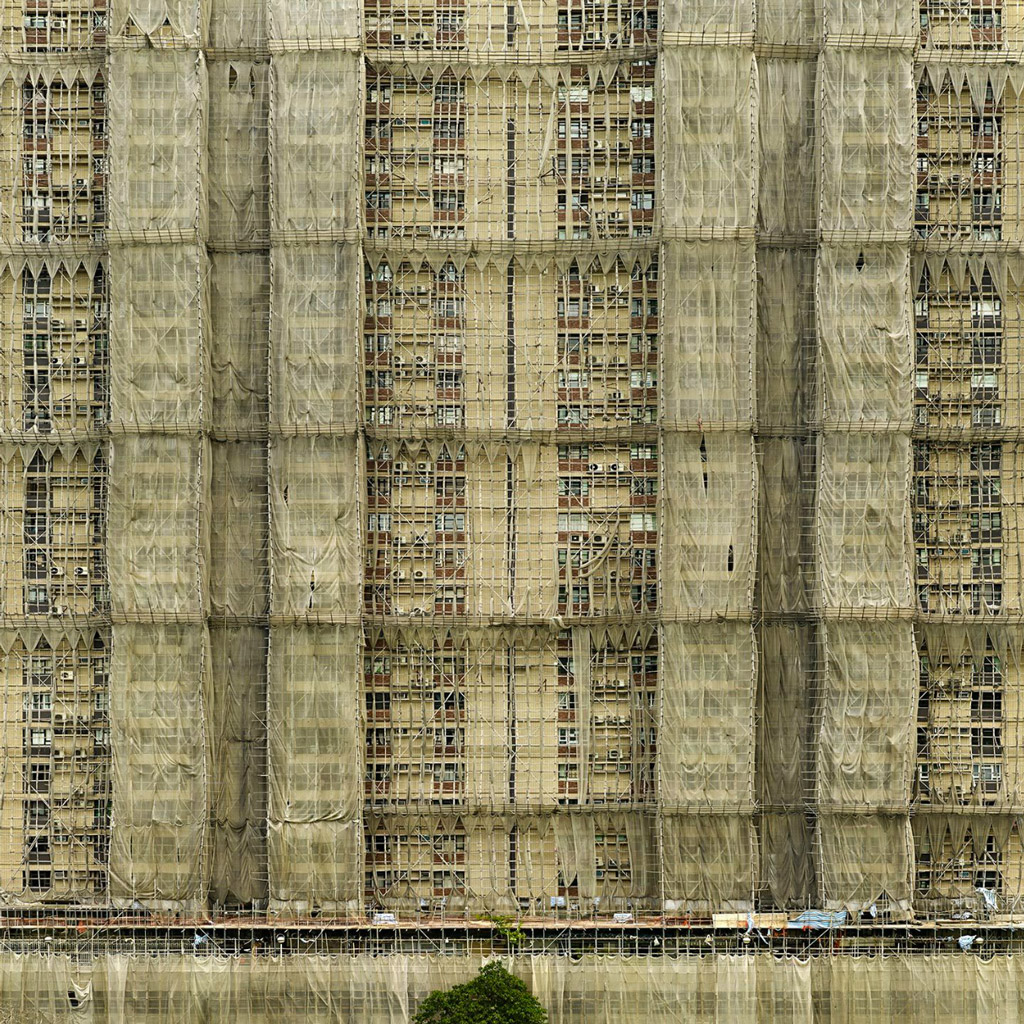

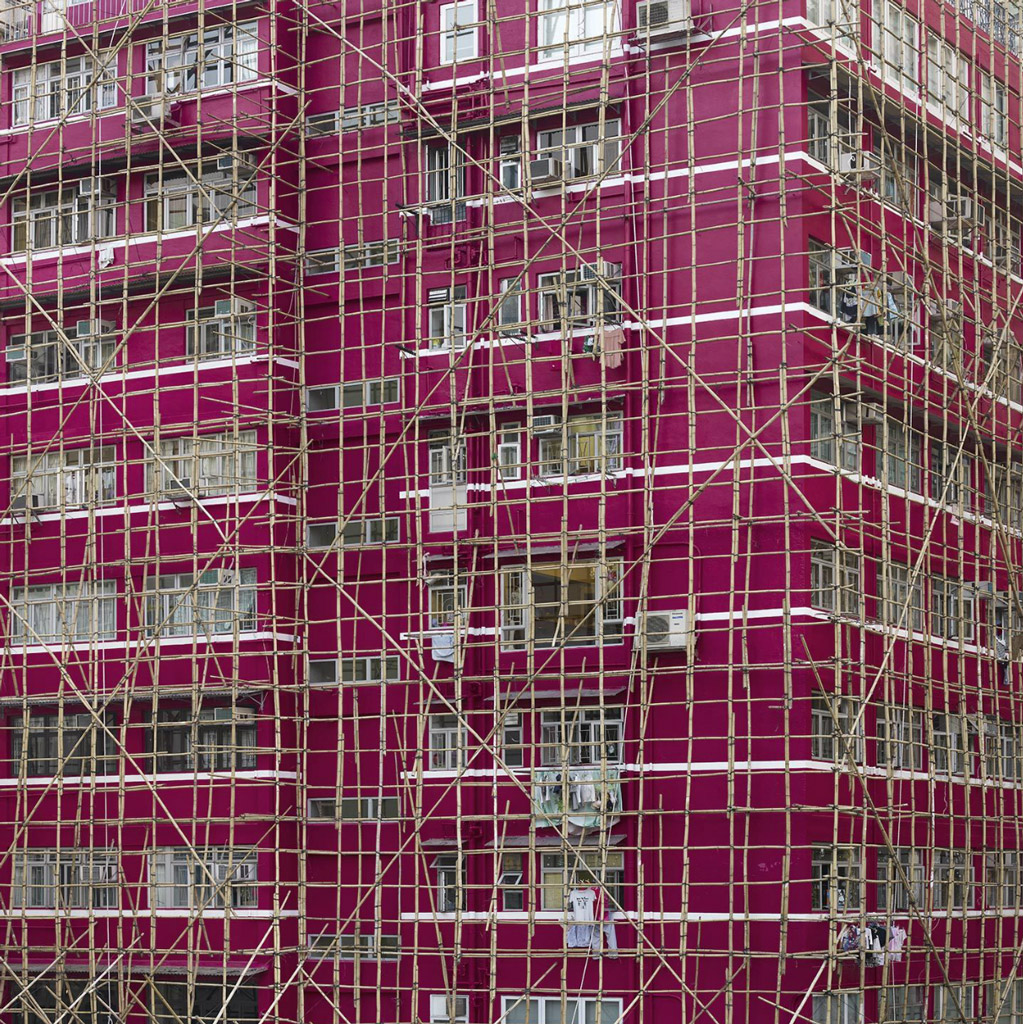

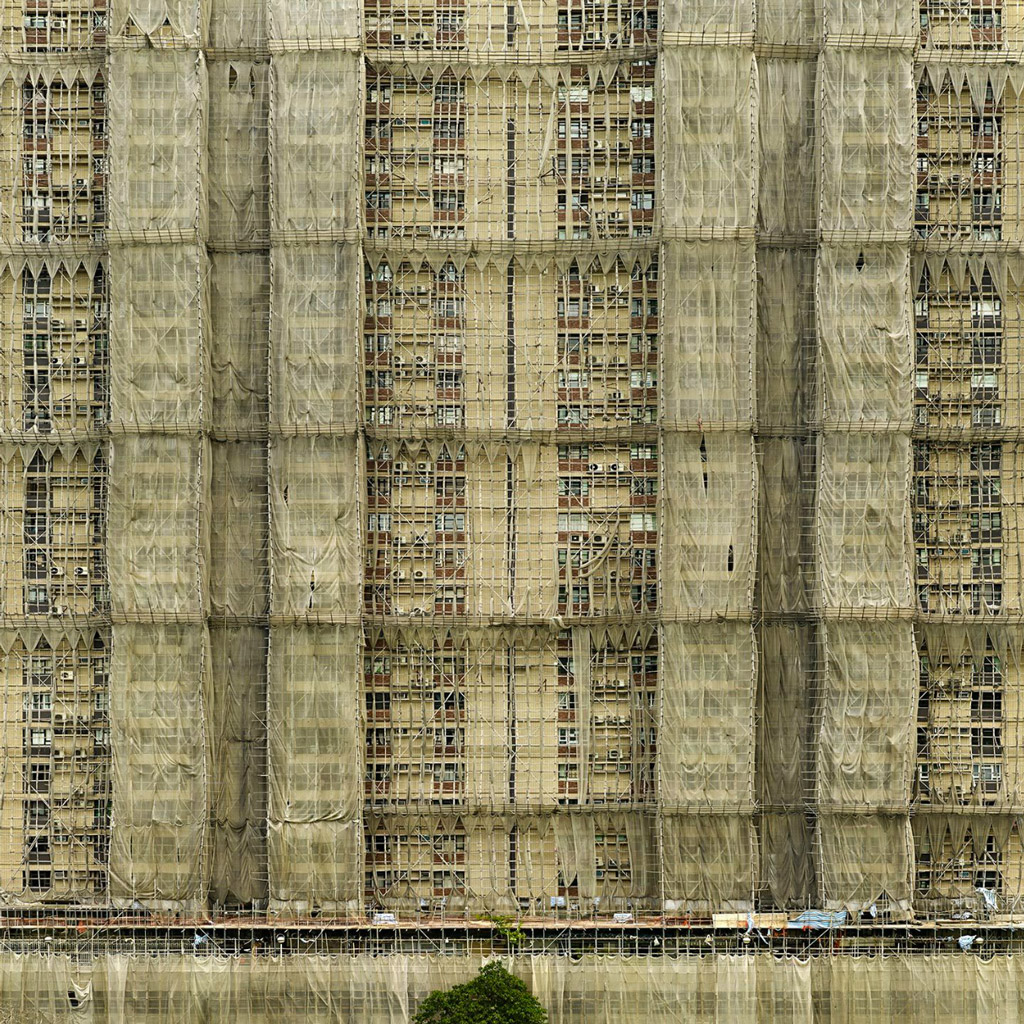

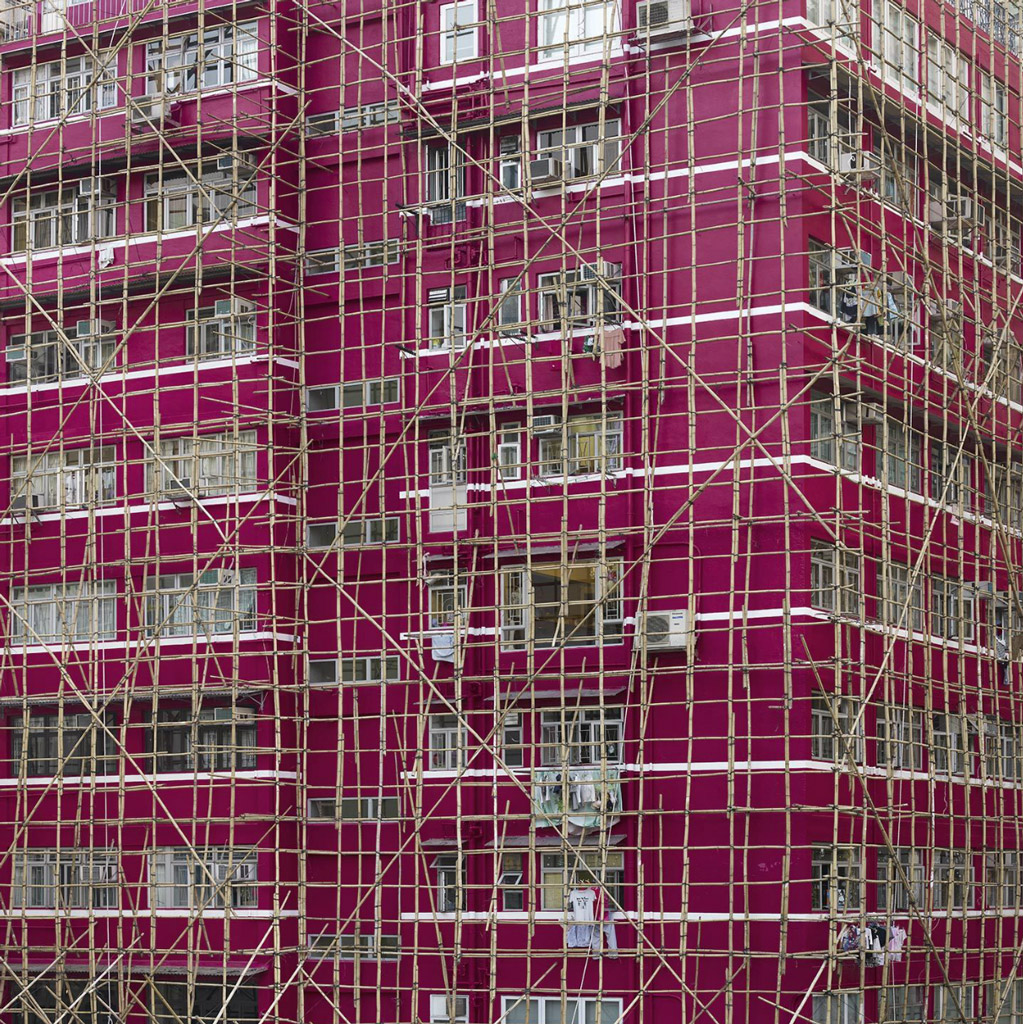

Since 1993, Peter Steinhauer has been documenting the many facets of Asian culture.

Upon his first visit to Hong Kong in January of 1994, arriving at the old Kai Tak International Airport, Steinhauer noticed a very large structure that was caged in bamboo and swathed in yellow material. He was amazed by this monumental structure, standing out beneath a canopy of clouds as it glowed against the monochromatic, urban skyline. Thus began Steinhauers fascination with these multicolored structures.

Once a practice throughout Asia, Hong Kong is the final stronghold of the bamboo scaffolders. The title Cocoon for this body of work was a natural choice. The framework; a metamorphosis; like caterpillars to butterflies. Colored material unveiled ceremoniously reveals a brand new façade, as in a cocoon revealing itself for the first time.

Peter Steinhauer (United States, 1966). Artist photographer who has been living and working un Asia since 1993. His photography focuses on architecture within urban landscape, natural landscape, Asian faces and man made structure. He is a recipient of numerous international photography awards including a finalist for the 2014 Lucie Awards, Ford Foundation grant for his multi year work in Viernam, Black and White Spider Award for Architecture, IPA and PX3 Paris awards, among others. He is also a member of the elite Explorers Club in New York.

Peter Steinhauer (United States, 1966). Artist photographer who has been living and working un Asia since 1993. His photography focuses on architecture within urban landscape, natural landscape, Asian faces and man made structure. He is a recipient of numerous international photography awards including a finalist for the 2014 Lucie Awards, Ford Foundation grant for his multi year work in Viernam, Black and White Spider Award for Architecture, IPA and PX3 Paris awards, among others. He is also a member of the elite Explorers Club in New York.

Since 1993, Peter Steinhauer has been documenting the many facets of Asian culture.

Upon his first visit to Hong Kong in January of 1994, arriving at the old Kai Tak International Airport, Steinhauer noticed a very large structure that was caged in bamboo and swathed in yellow material. He was amazed by this monumental structure, standing out beneath a canopy of clouds as it glowed against the monochromatic, urban skyline. Thus began Steinhauers fascination with these multicolored structures.

Once a practice throughout Asia, Hong Kong is the final stronghold of the bamboo scaffolders. The title Cocoon for this body of work was a natural choice. The framework; a metamorphosis; like caterpillars to butterflies. Colored material unveiled ceremoniously reveals a brand new façade, as in a cocoon revealing itself for the first time.

Peter Steinhauer (United States, 1966). Artist photographer who has been living and working un Asia since 1993. His photography focuses on architecture within urban landscape, natural landscape, Asian faces and man made structure. He is a recipient of numerous international photography awards including a finalist for the 2014 Lucie Awards, Ford Foundation grant for his multi year work in Viernam, Black and White Spider Award for Architecture, IPA and PX3 Paris awards, among others. He is also a member of the elite Explorers Club in New York.

Peter Steinhauer (United States, 1966). Artist photographer who has been living and working un Asia since 1993. His photography focuses on architecture within urban landscape, natural landscape, Asian faces and man made structure. He is a recipient of numerous international photography awards including a finalist for the 2014 Lucie Awards, Ford Foundation grant for his multi year work in Viernam, Black and White Spider Award for Architecture, IPA and PX3 Paris awards, among others. He is also a member of the elite Explorers Club in New York.Kevin Weir

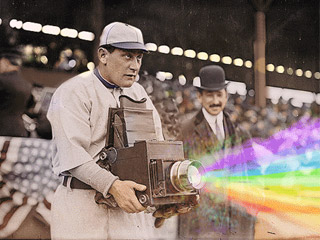

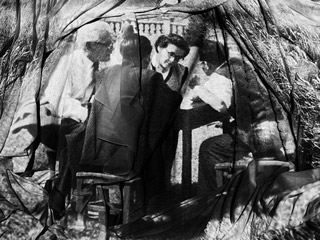

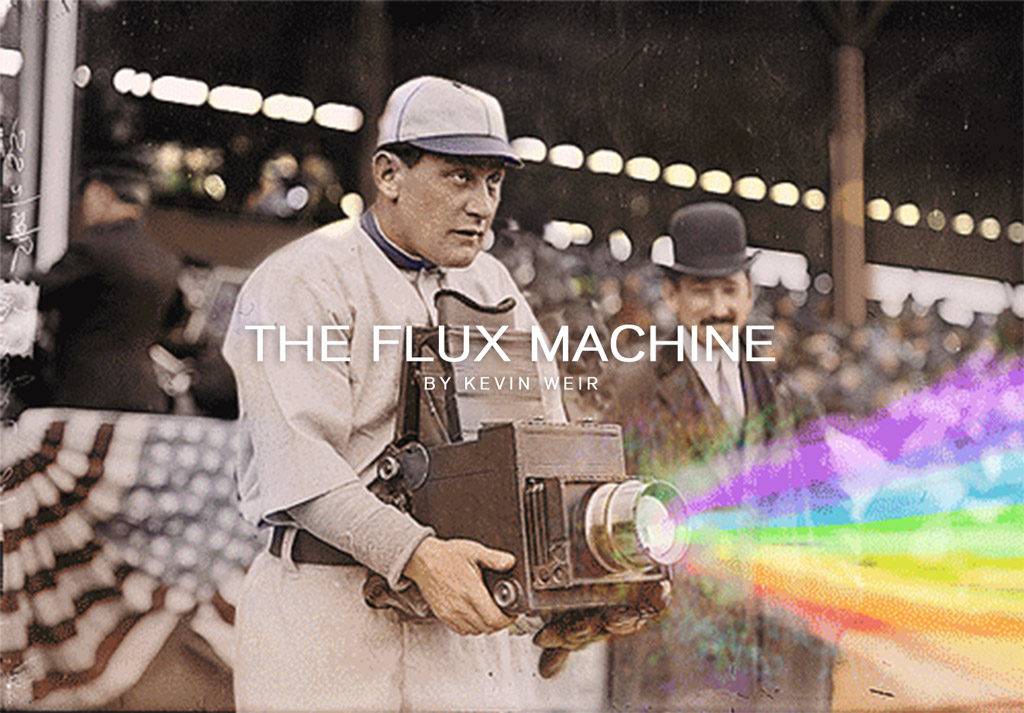

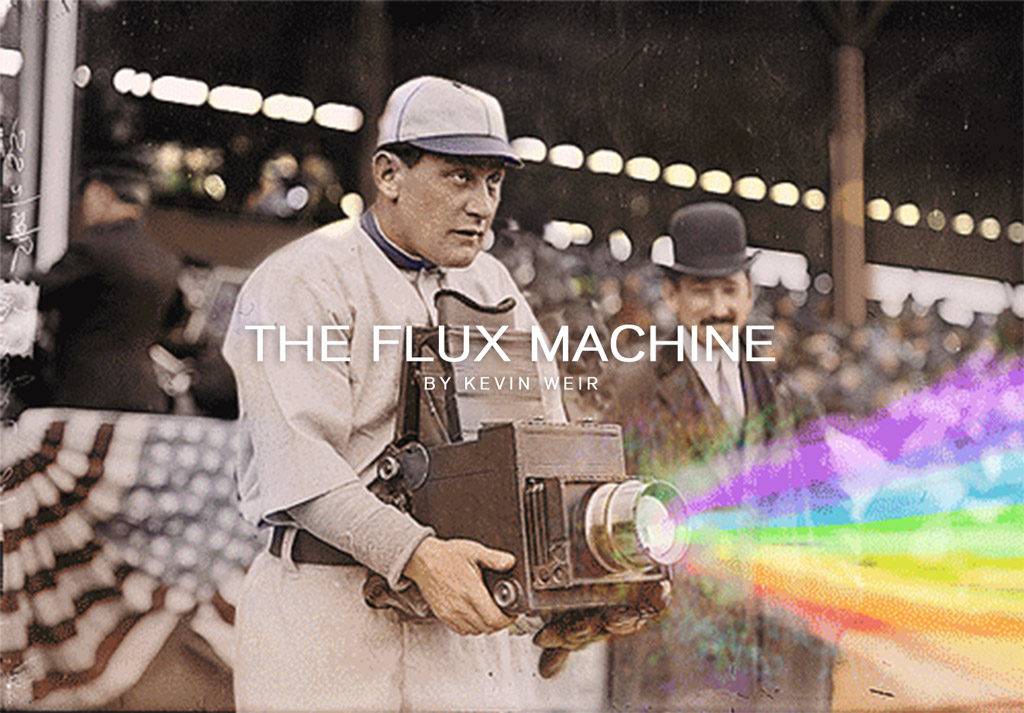

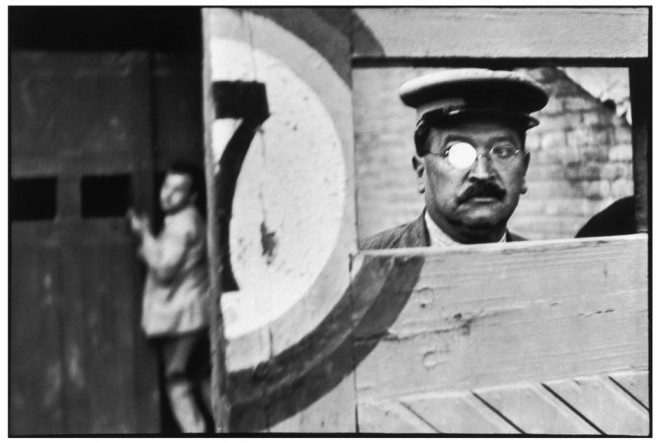

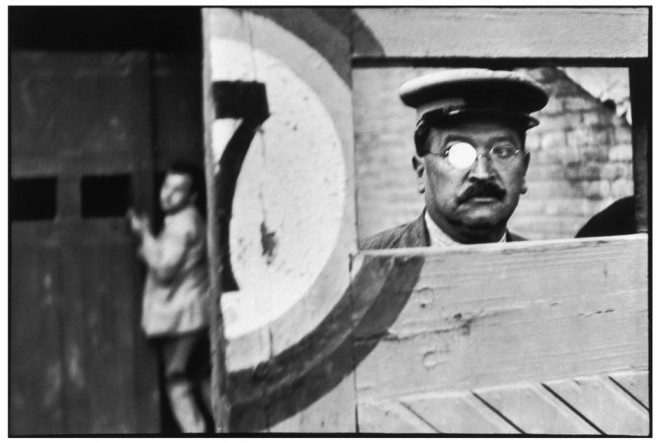

Kevin Weir’s Flux Machine swivels between two lines closely related to the theme of temporality: using the format of animated GIF, he gives static images infinite and recurrent movement, and integrating narrative elements into archival photographs he reinterprets its meaning. The resulting microfictions offer readings at different levels questioning our usual interpretation of archival materials and leading us to crossroads between the historic moment and the imagined action.

Kevin Weir (USA) Grew up in the woods of rural upstate New York, just outside of Binghamton. He went to Penn State for his undergrad. Studied abroad in Australia. He got a masters at the VCU Brandcenter and, now, works as an art director at Droga5 in NYC. He is known worldwide for his animation project The Flux Machine, for which he uses the Bain Collection at the Library of Congress.

Kevin Weir (USA) Grew up in the woods of rural upstate New York, just outside of Binghamton. He went to Penn State for his undergrad. Studied abroad in Australia. He got a masters at the VCU Brandcenter and, now, works as an art director at Droga5 in NYC. He is known worldwide for his animation project The Flux Machine, for which he uses the Bain Collection at the Library of Congress.

Kevin Weir’s Flux Machine swivels between two lines closely related to the theme of temporality: using the format of animated GIF, he gives static images infinite and recurrent movement, and integrating narrative elements into archival photographs he reinterprets its meaning. The resulting microfictions offer readings at different levels questioning our usual interpretation of archival materials and leading us to crossroads between the historic moment and the imagined action.

Kevin Weir (USA) Grew up in the woods of rural upstate New York, just outside of Binghamton. He went to Penn State for his undergrad. Studied abroad in Australia. He got a masters at the VCU Brandcenter and, now, works as an art director at Droga5 in NYC. He is known worldwide for his animation project The Flux Machine, for which he uses the Bain Collection at the Library of Congress.

Kevin Weir (USA) Grew up in the woods of rural upstate New York, just outside of Binghamton. He went to Penn State for his undergrad. Studied abroad in Australia. He got a masters at the VCU Brandcenter and, now, works as an art director at Droga5 in NYC. He is known worldwide for his animation project The Flux Machine, for which he uses the Bain Collection at the Library of Congress.Pelle Cass

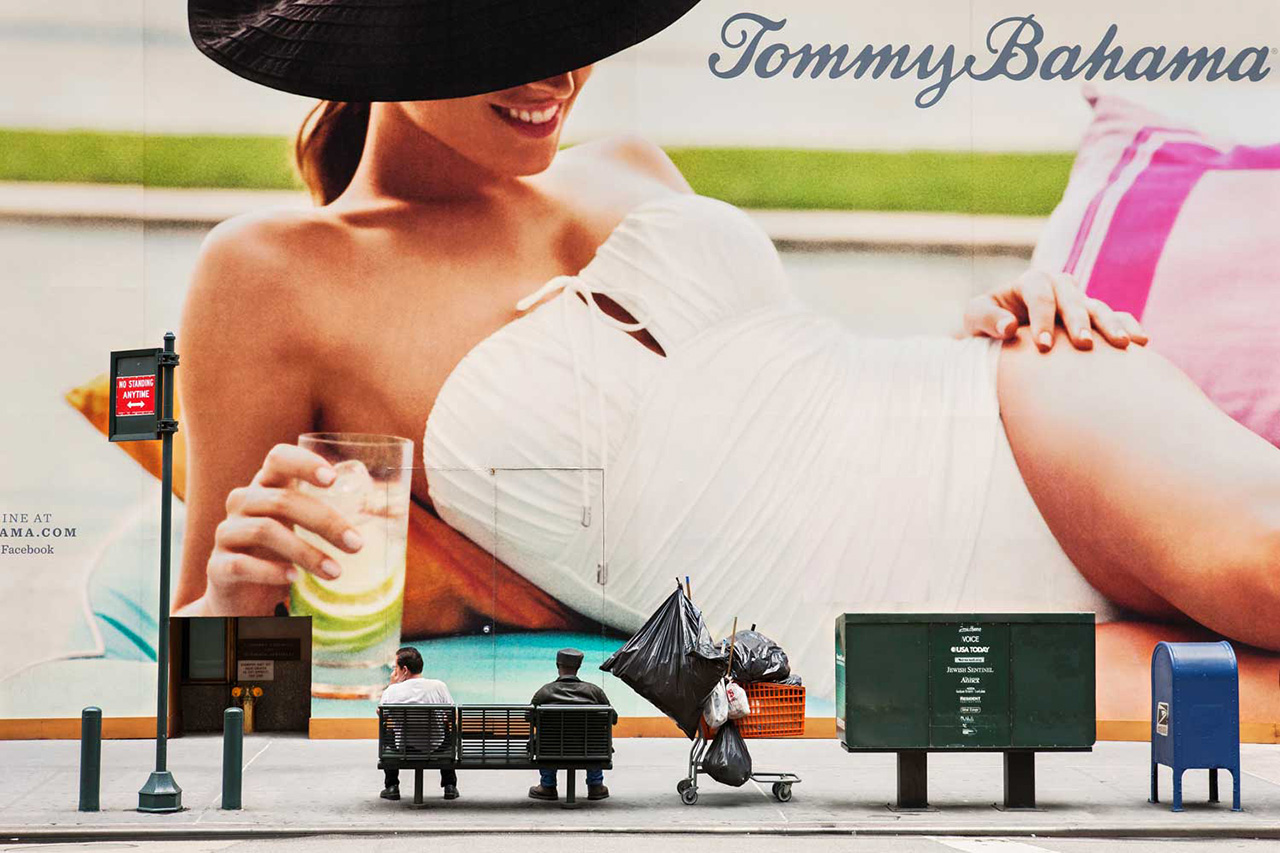

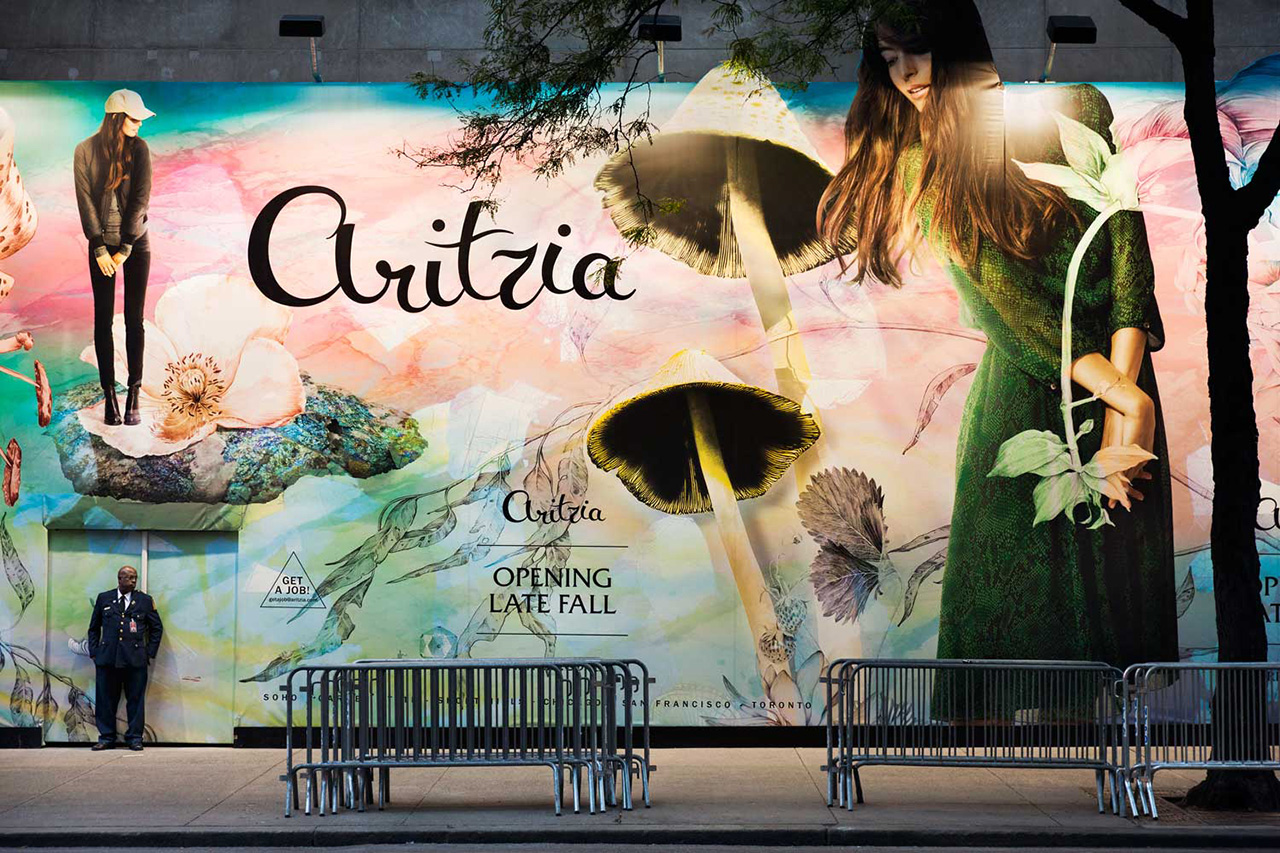

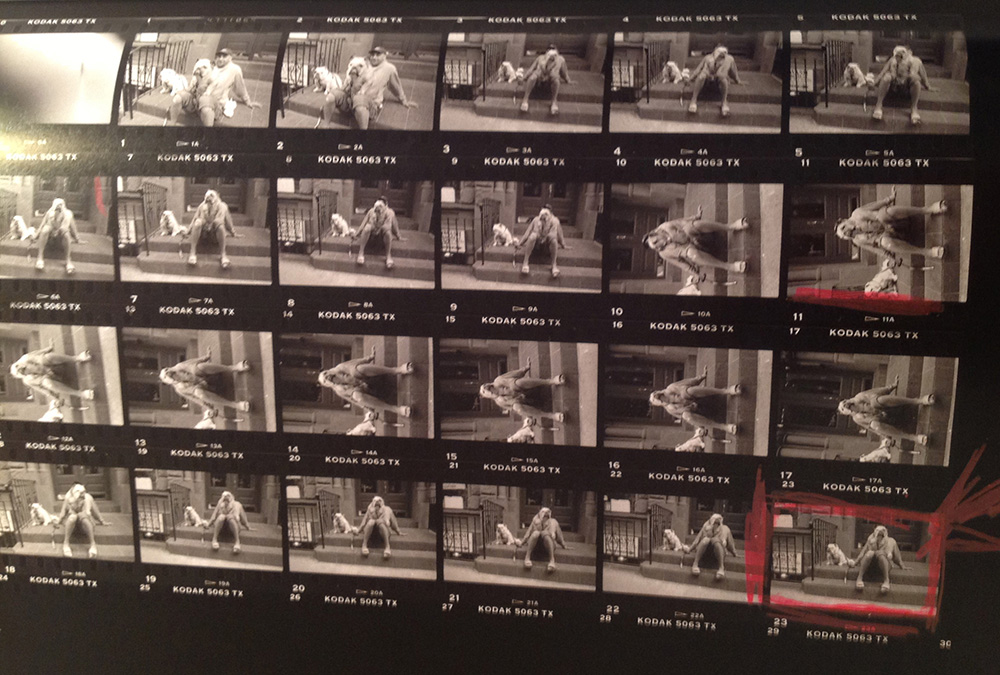

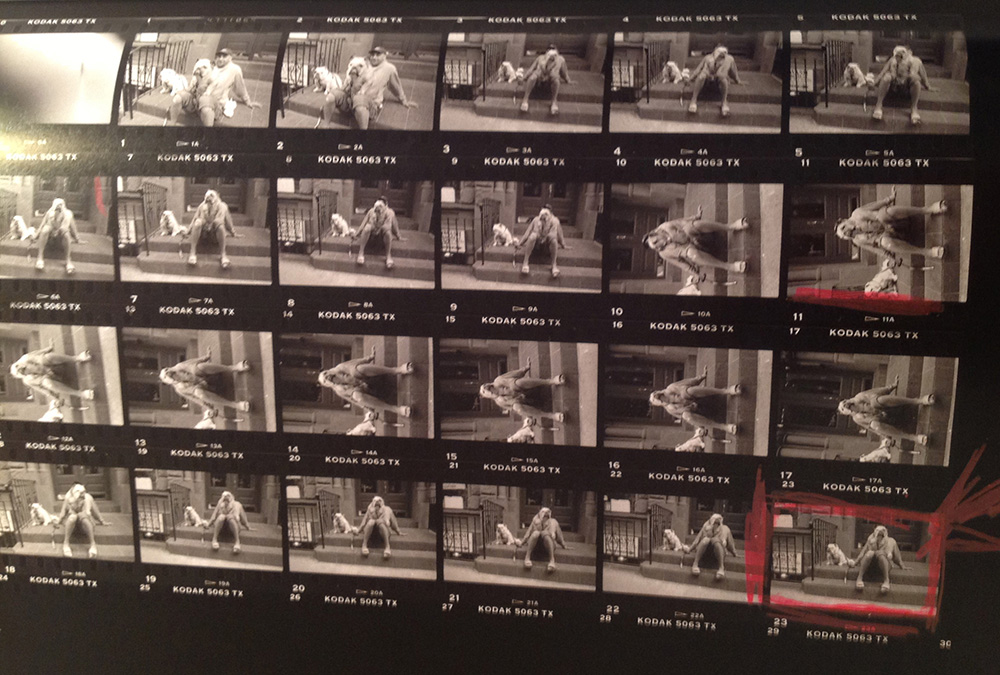

This work both orders the world and exaggerates its chaos. With the camera on a tripod, I take many photos, leave in the best ones and omit the rest. The photographs are composed but they have not been changed, only selected. My work is about the strangeness of time, about how people really look, and about the surprising world that is only visible with a camera. I want to capture more life, more people, more time, and more truth in my photographs. Photography, with its ability to record everything in front of the lens, is just the beginning of this process. Selected People is inspired by surveillance photography, Walker Evans’s hidden-camera subway portraits, and P.L. di Corcia’s Head series; works in which the camera waits for its subjects to come into view. My work also looks at city life from a fixed position, with the difference that each image contains an hour’s time and is a composition of hundreds of exposures. To do this, I put the camera on a tripod, and take hundreds of pictures as people pass by. Back in the studio, I choose what to leave in and make no further alterations. The process mirrors the way the mind focuses attention on one thing but not on another. A person thinking about photography, for example, tends to notice people with cameras over those without. This kind of selection allows me to take objective facts–the faces and bodies of people on the street–and make something new and more subjective out of them, simply by sorting them. Above all, I want to show a surprising world that is visible only with a camera.

Pelle Cass (Brookline, MA). He has presented solo shows at the Houston Center for Photography; Gallery Kayafas, Boston; Stux Gallery, Boston; Frank Marino Gallery, NYC; the Griffin Museum of Photography; and the Fogg Art Museum’s print room. His work is in the collections of the Fogg Art Museum, the Addison Gallery of American Art, the Polaroid Collection, the DeCordova Museum, the Danforth Museum of Art, the Peabody Essex Museum, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, and the Lehigh University Art Galleries, among others. He was a Winner: Top 50, Critical Mass, Photolucida, Portland, OR, in 2008 and 2009, was awarded fellowships by the Corporation of Yaddo in 2010 and 2012, and won an Artist’s Resource Trust Award (Berkshire Taconic Foundation) in 2012. He lives in Brookline, Massachusetts.

Pelle Cass (Brookline, MA). He has presented solo shows at the Houston Center for Photography; Gallery Kayafas, Boston; Stux Gallery, Boston; Frank Marino Gallery, NYC; the Griffin Museum of Photography; and the Fogg Art Museum’s print room. His work is in the collections of the Fogg Art Museum, the Addison Gallery of American Art, the Polaroid Collection, the DeCordova Museum, the Danforth Museum of Art, the Peabody Essex Museum, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, and the Lehigh University Art Galleries, among others. He was a Winner: Top 50, Critical Mass, Photolucida, Portland, OR, in 2008 and 2009, was awarded fellowships by the Corporation of Yaddo in 2010 and 2012, and won an Artist’s Resource Trust Award (Berkshire Taconic Foundation) in 2012. He lives in Brookline, Massachusetts.

This work both orders the world and exaggerates its chaos. With the camera on a tripod, I take many photos, leave in the best ones and omit the rest. The photographs are composed but they have not been changed, only selected. My work is about the strangeness of time, about how people really look, and about the surprising world that is only visible with a camera. I want to capture more life, more people, more time, and more truth in my photographs. Photography, with its ability to record everything in front of the lens, is just the beginning of this process. Selected People is inspired by surveillance photography, Walker Evans’s hidden-camera subway portraits, and P.L. di Corcia’s Head series; works in which the camera waits for its subjects to come into view. My work also looks at city life from a fixed position, with the difference that each image contains an hour’s time and is a composition of hundreds of exposures. To do this, I put the camera on a tripod, and take hundreds of pictures as people pass by. Back in the studio, I choose what to leave in and make no further alterations. The process mirrors the way the mind focuses attention on one thing but not on another. A person thinking about photography, for example, tends to notice people with cameras over those without. This kind of selection allows me to take objective facts–the faces and bodies of people on the street–and make something new and more subjective out of them, simply by sorting them. Above all, I want to show a surprising world that is visible only with a camera.

Pelle Cass (Brookline, MA). He has presented solo shows at the Houston Center for Photography; Gallery Kayafas, Boston; Stux Gallery, Boston; Frank Marino Gallery, NYC; the Griffin Museum of Photography; and the Fogg Art Museum’s print room. His work is in the collections of the Fogg Art Museum, the Addison Gallery of American Art, the Polaroid Collection, the DeCordova Museum, the Danforth Museum of Art, the Peabody Essex Museum, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, and the Lehigh University Art Galleries, among others. He was a Winner: Top 50, Critical Mass, Photolucida, Portland, OR, in 2008 and 2009, was awarded fellowships by the Corporation of Yaddo in 2010 and 2012, and won an Artist’s Resource Trust Award (Berkshire Taconic Foundation) in 2012. He lives in Brookline, Massachusetts.

Pelle Cass (Brookline, MA). He has presented solo shows at the Houston Center for Photography; Gallery Kayafas, Boston; Stux Gallery, Boston; Frank Marino Gallery, NYC; the Griffin Museum of Photography; and the Fogg Art Museum’s print room. His work is in the collections of the Fogg Art Museum, the Addison Gallery of American Art, the Polaroid Collection, the DeCordova Museum, the Danforth Museum of Art, the Peabody Essex Museum, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, and the Lehigh University Art Galleries, among others. He was a Winner: Top 50, Critical Mass, Photolucida, Portland, OR, in 2008 and 2009, was awarded fellowships by the Corporation of Yaddo in 2010 and 2012, and won an Artist’s Resource Trust Award (Berkshire Taconic Foundation) in 2012. He lives in Brookline, Massachusetts.Eduardo Muñoz

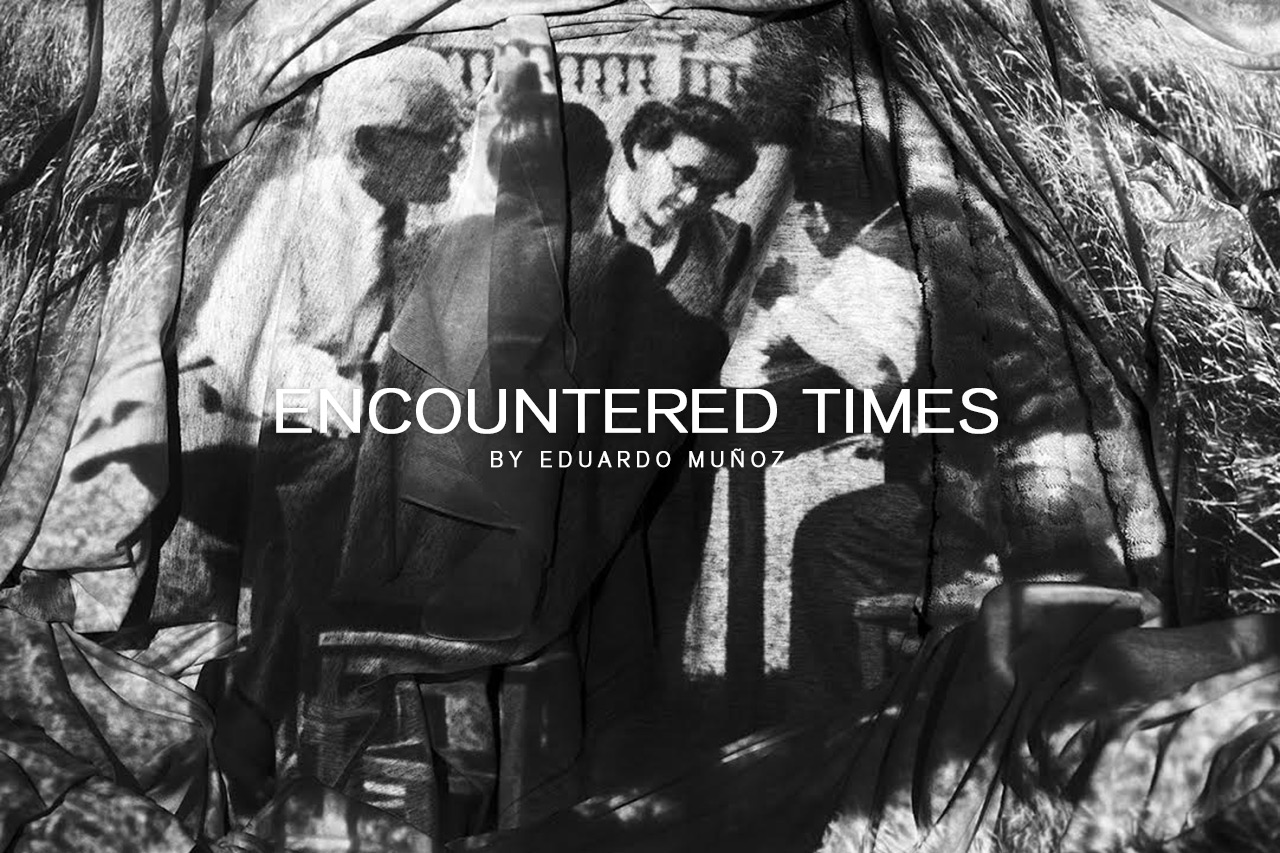

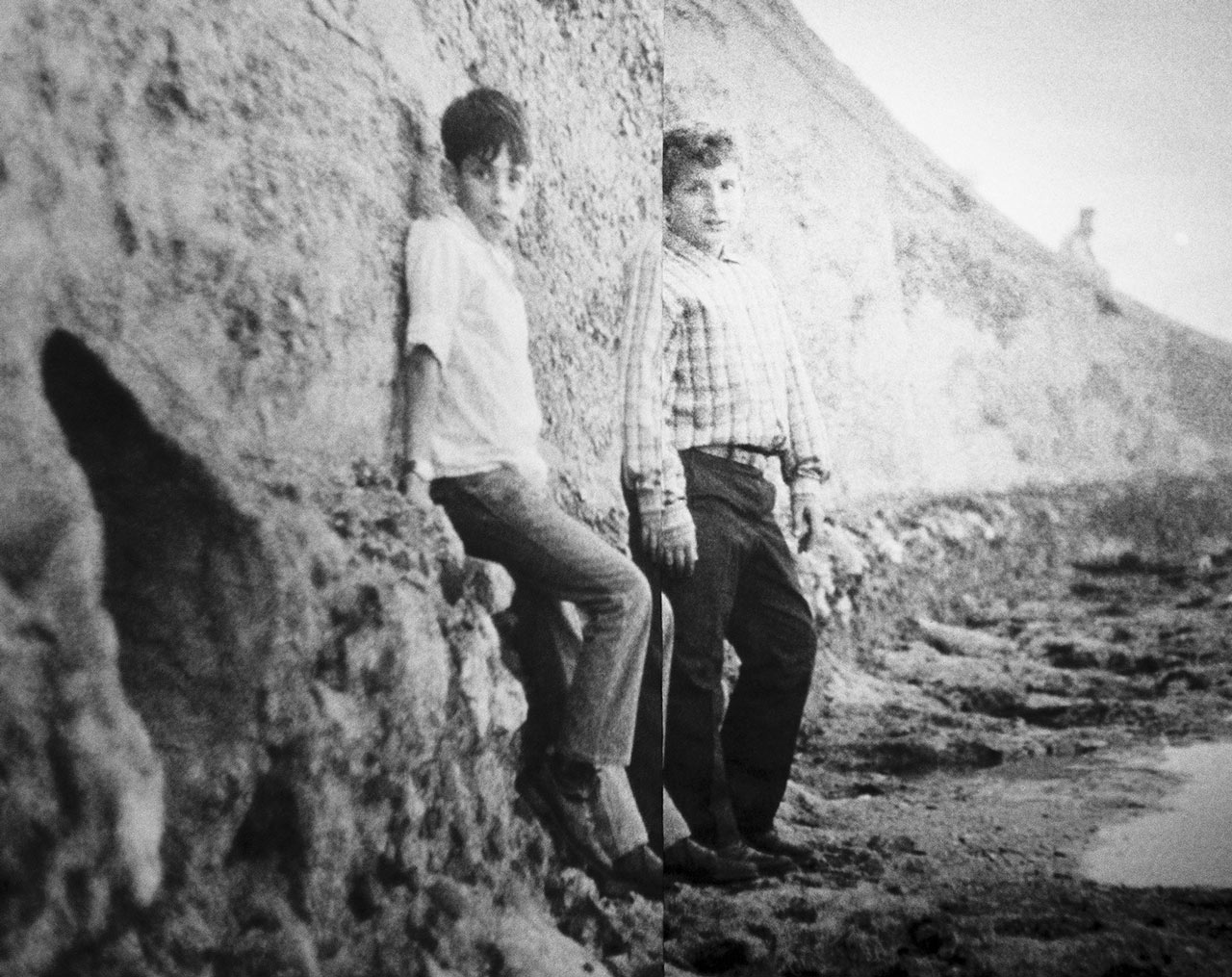

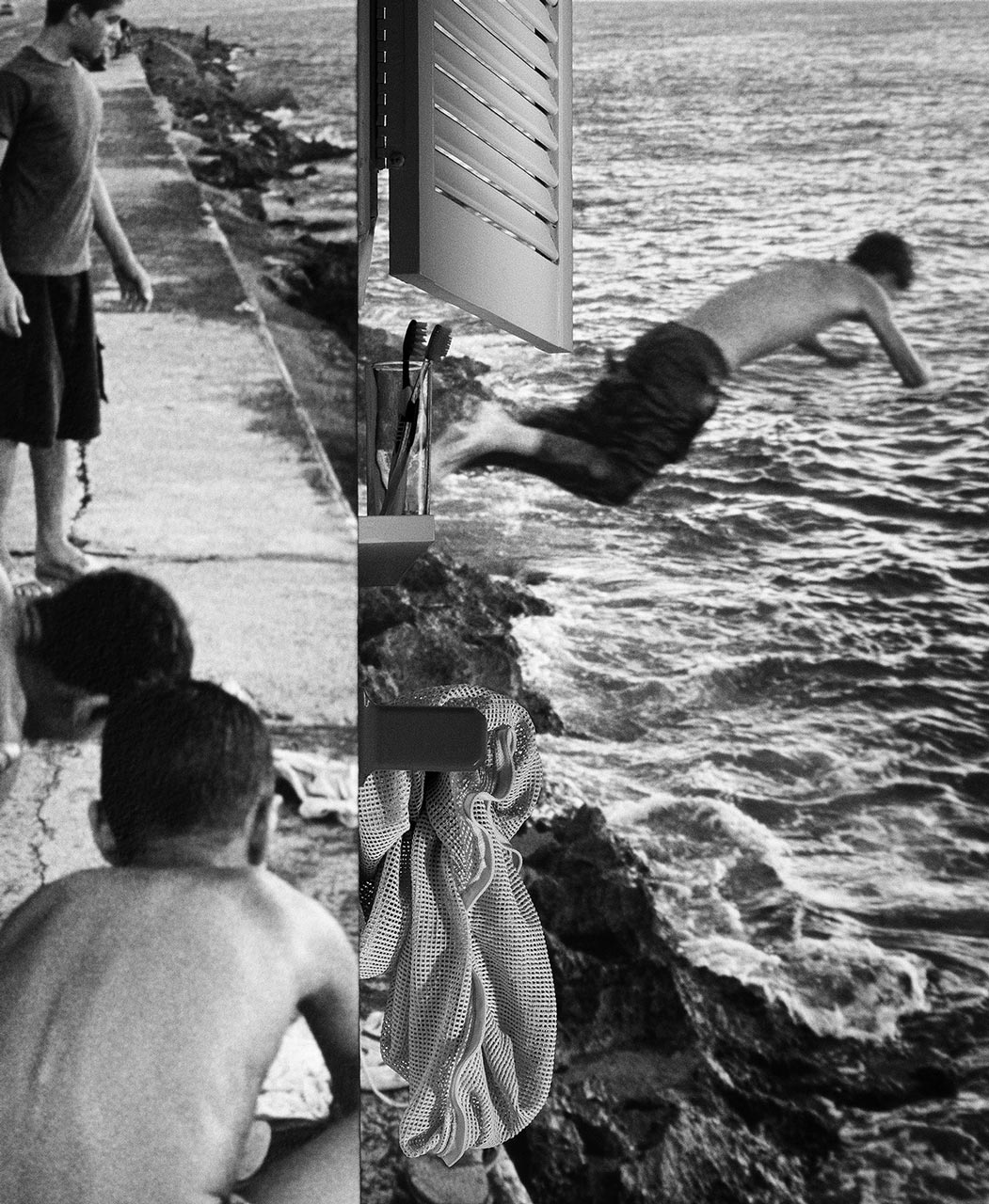

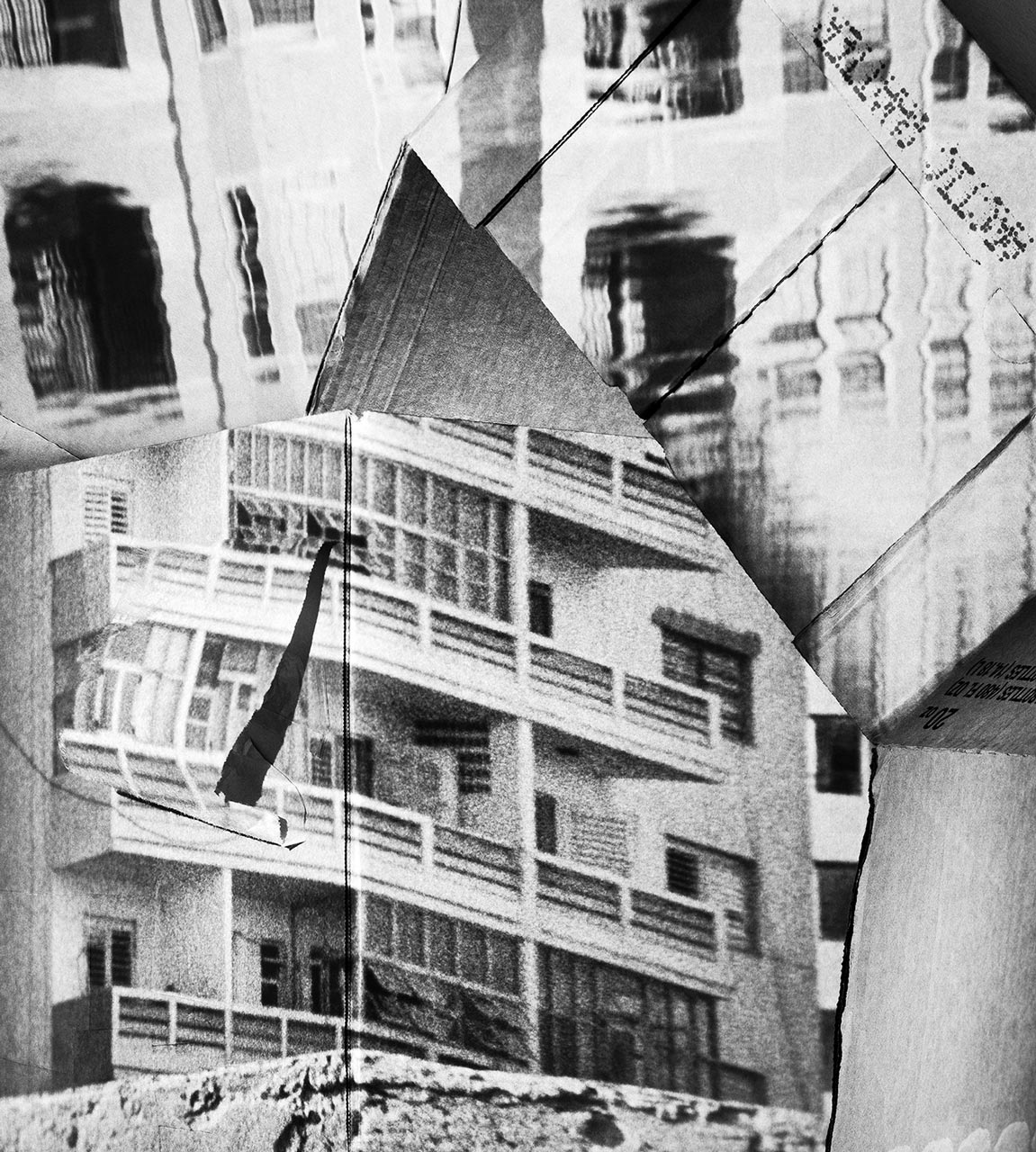

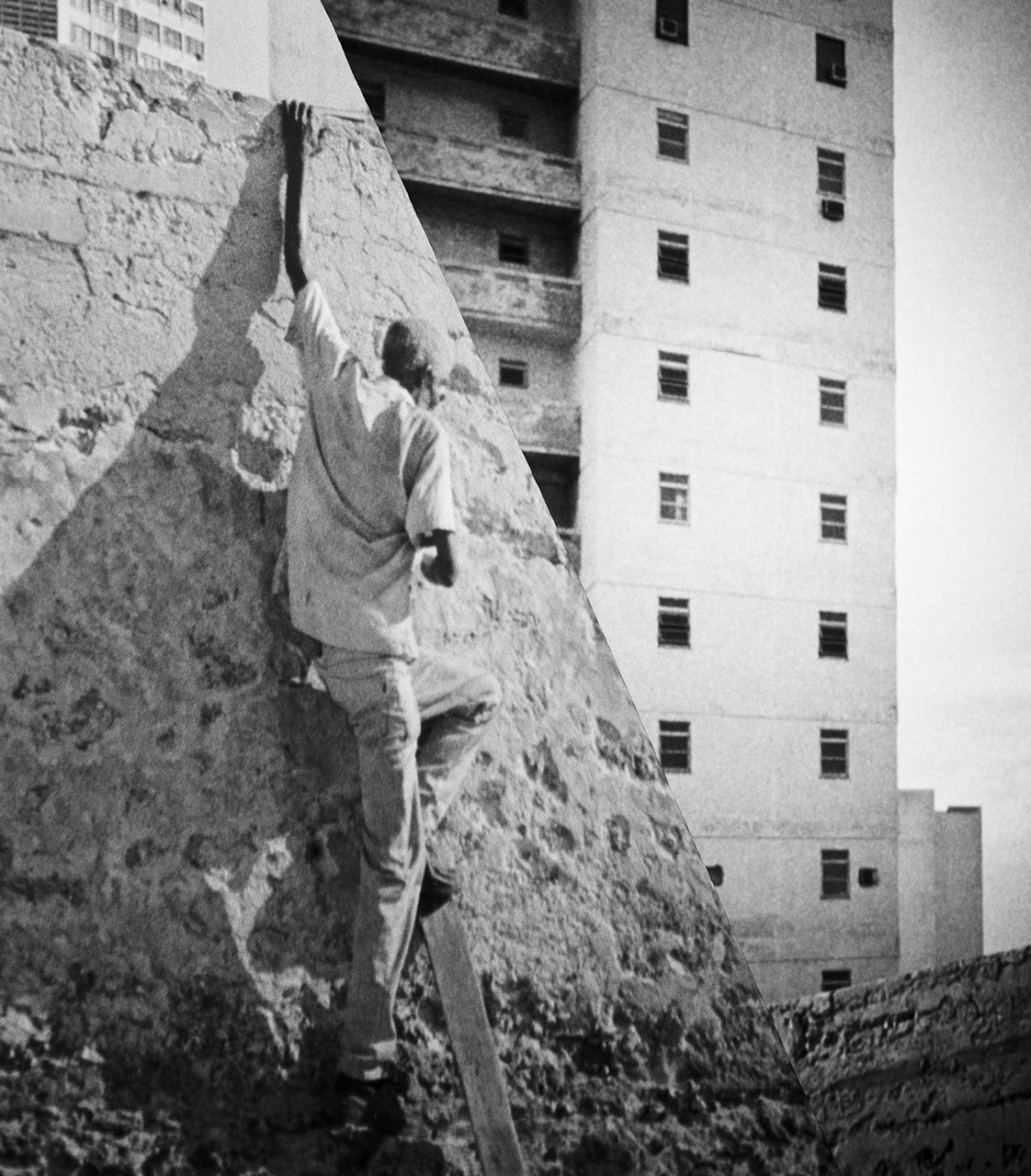

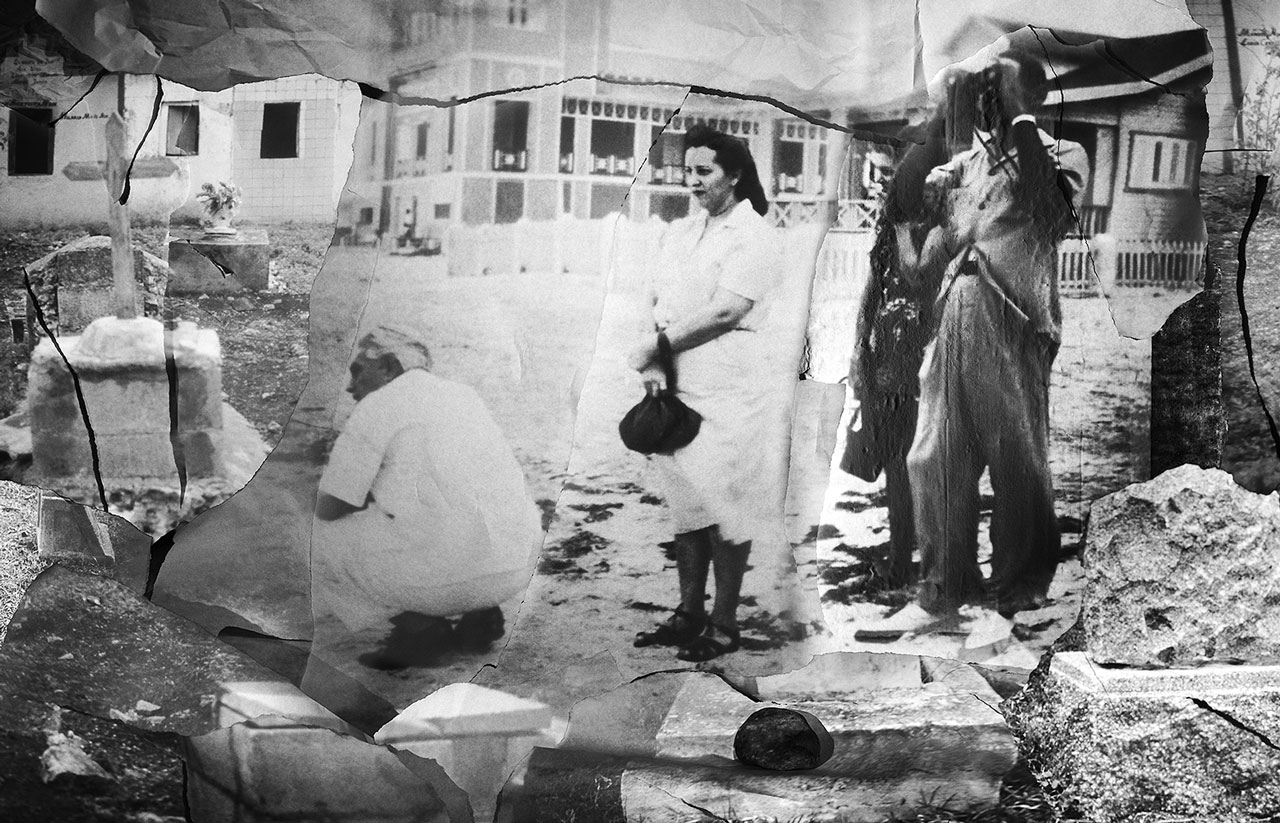

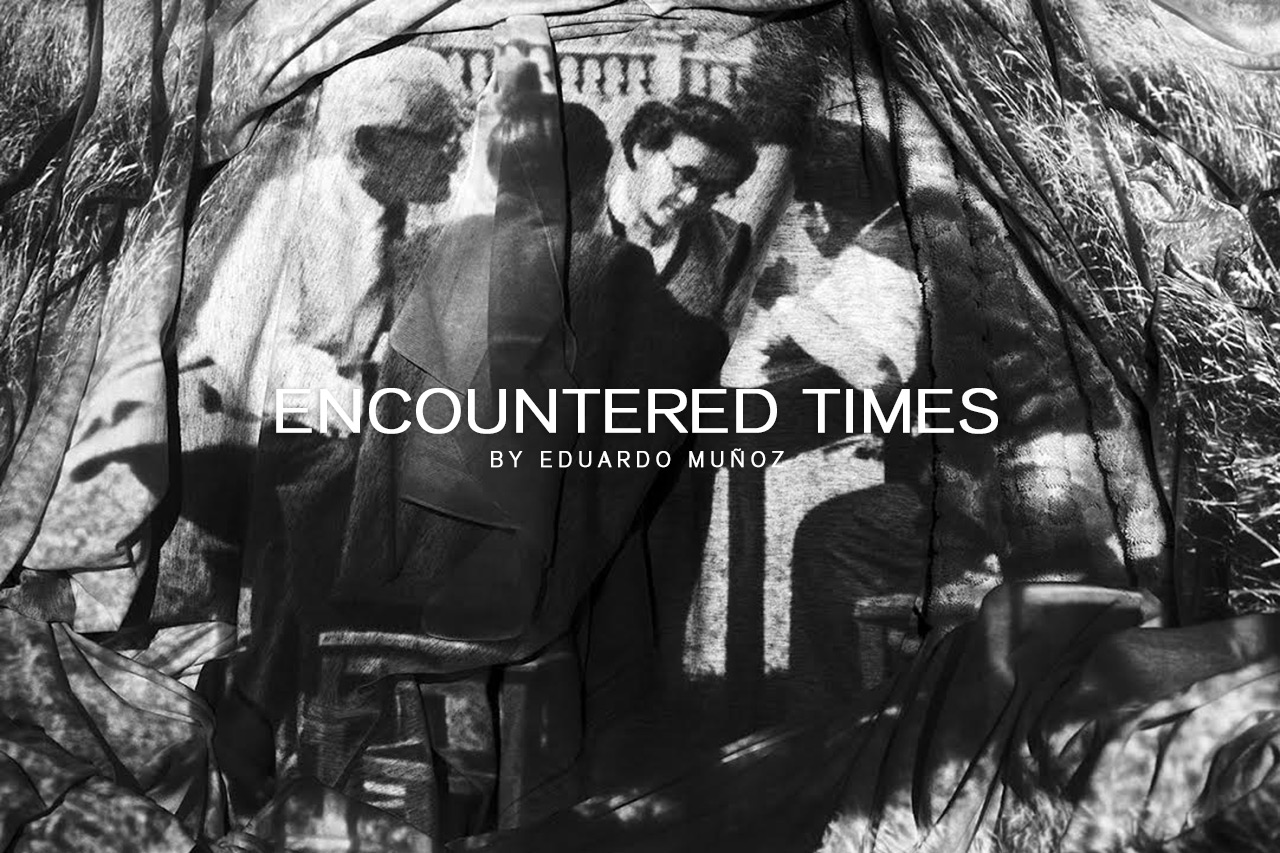

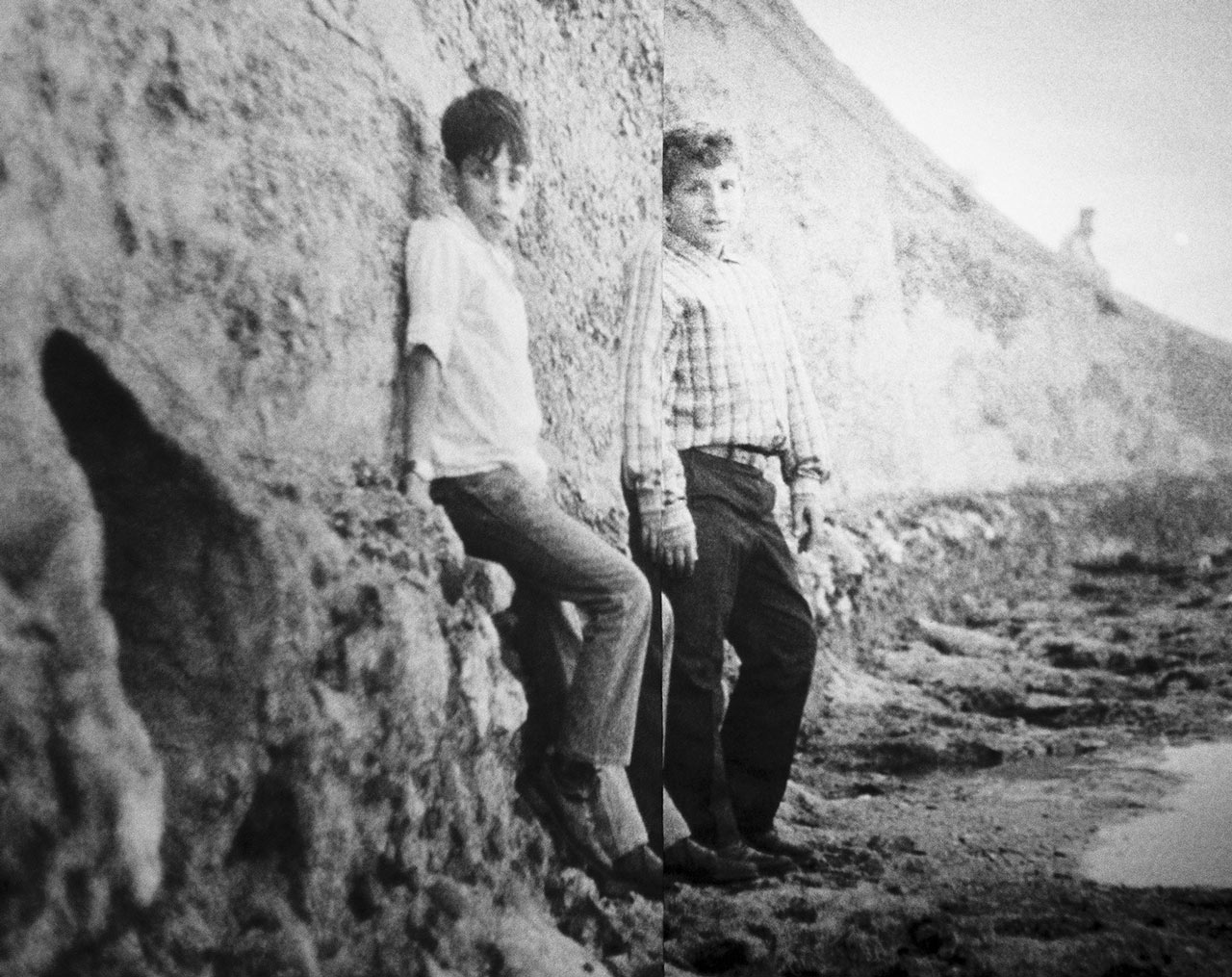

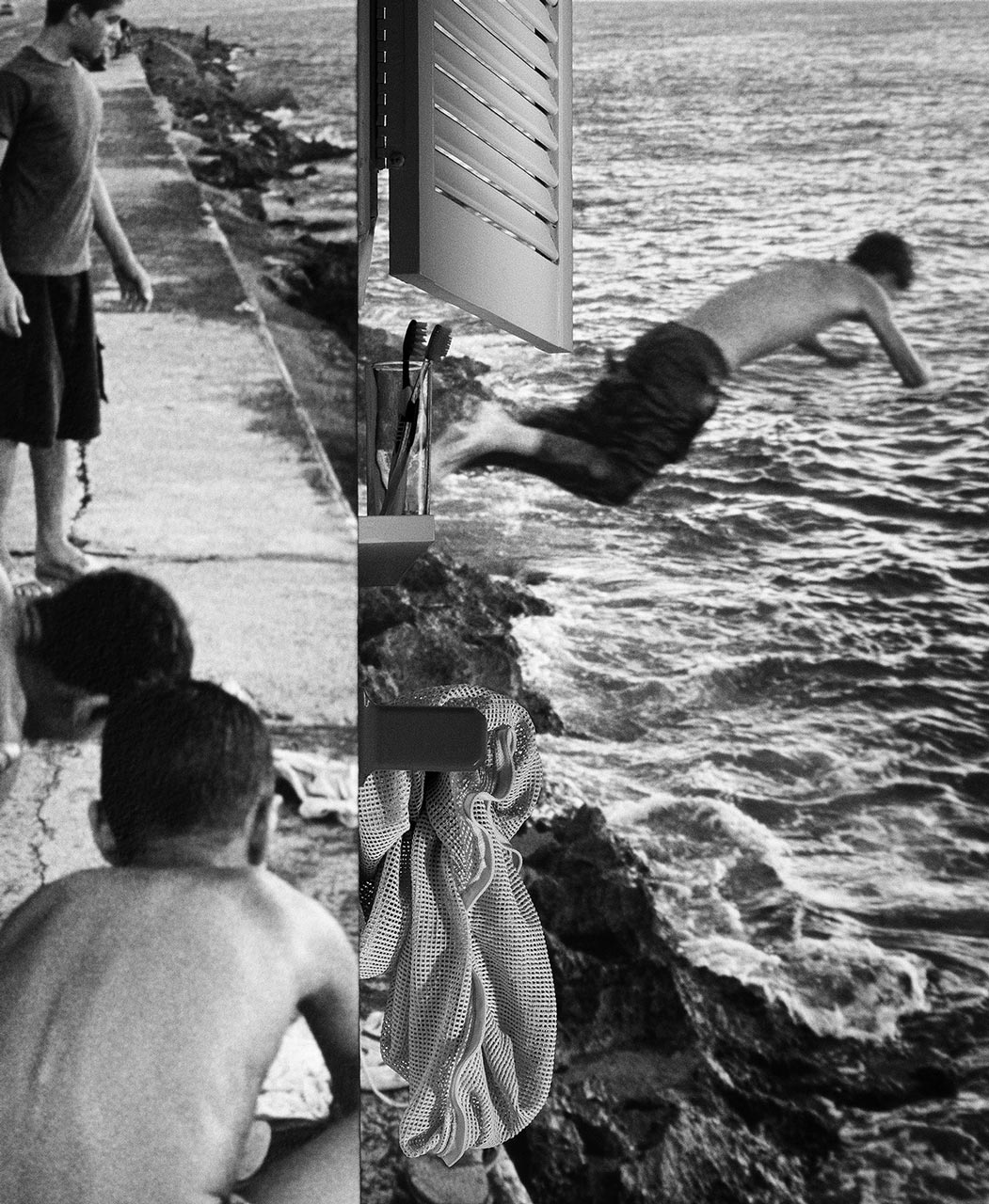

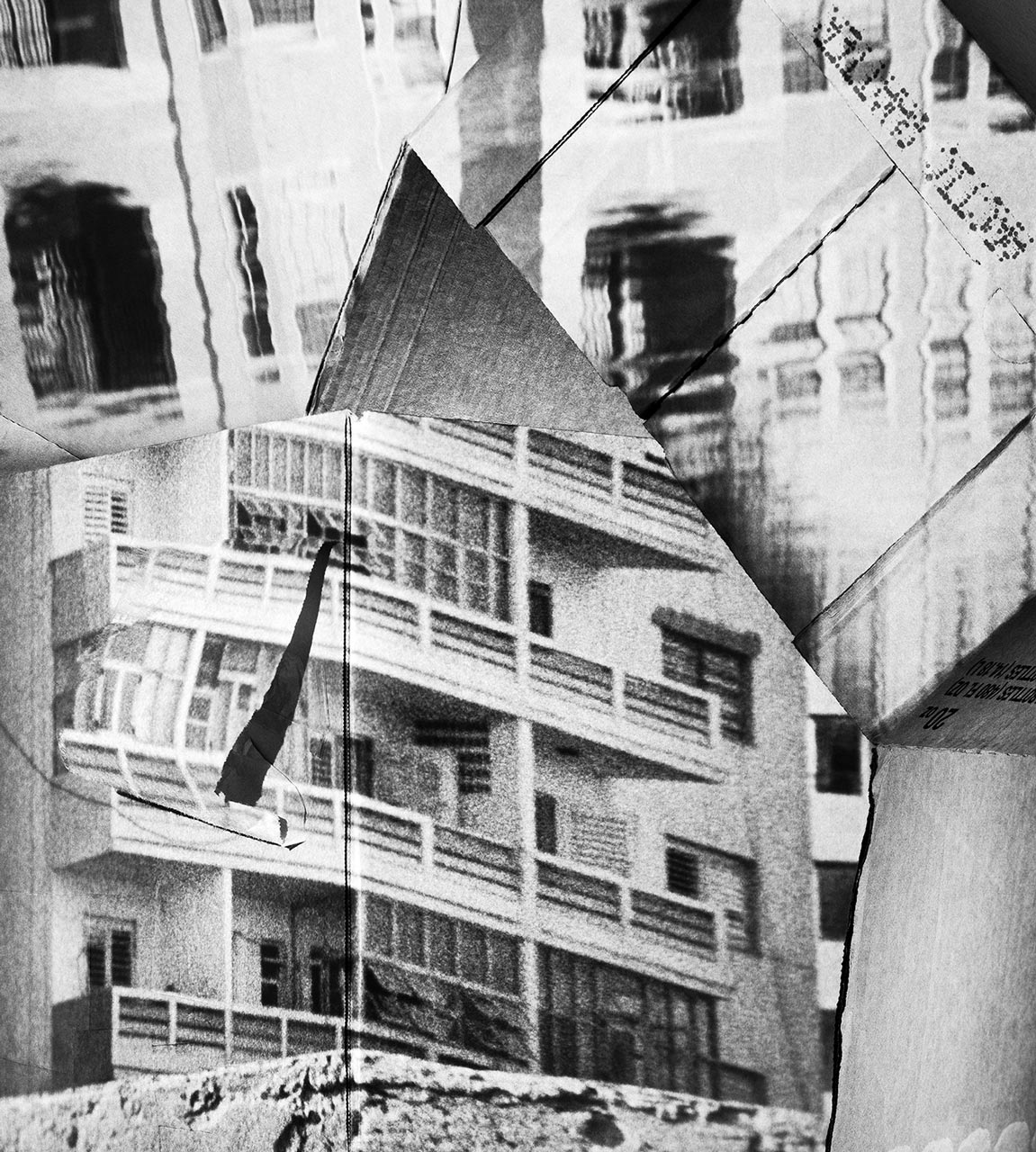

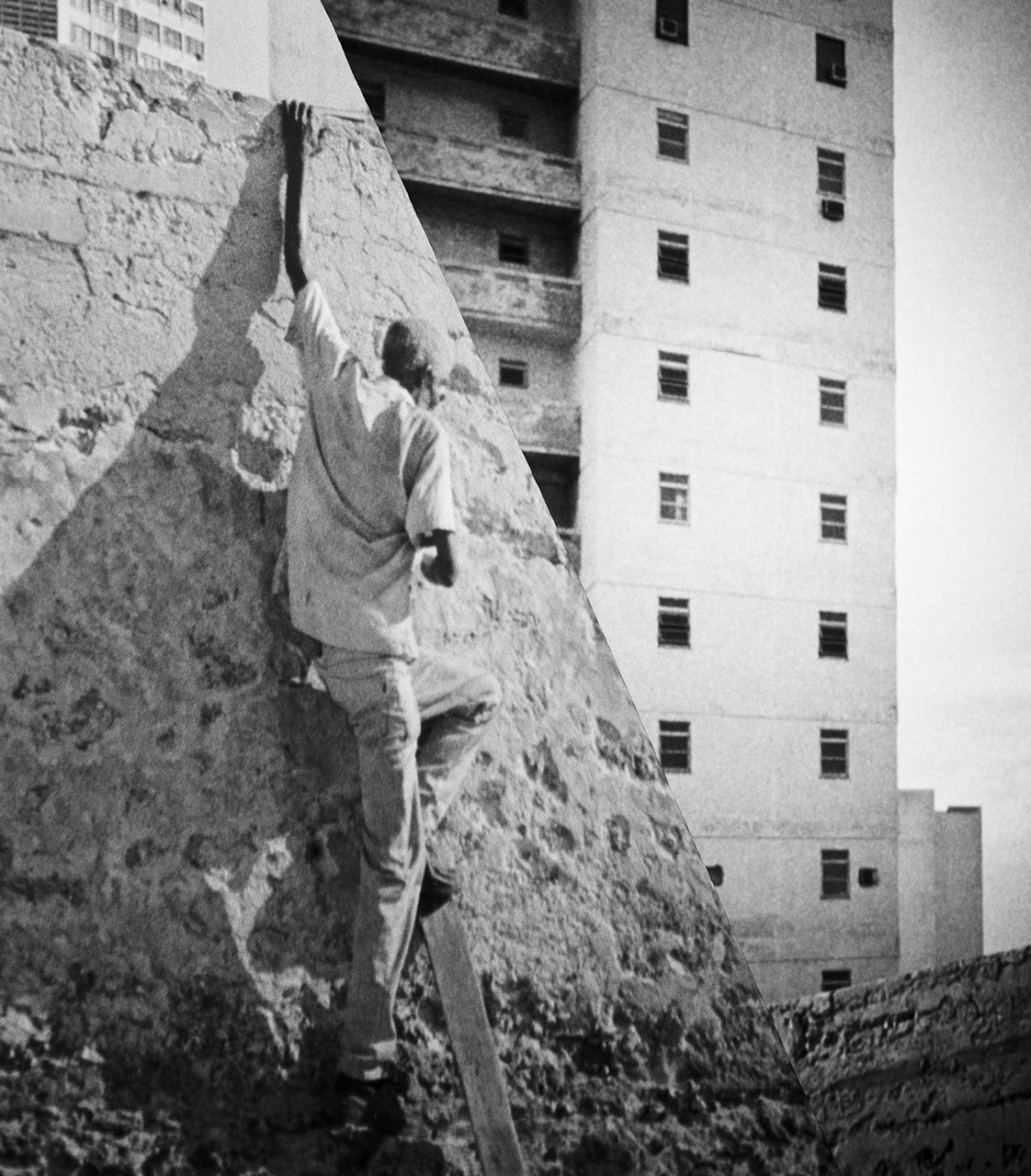

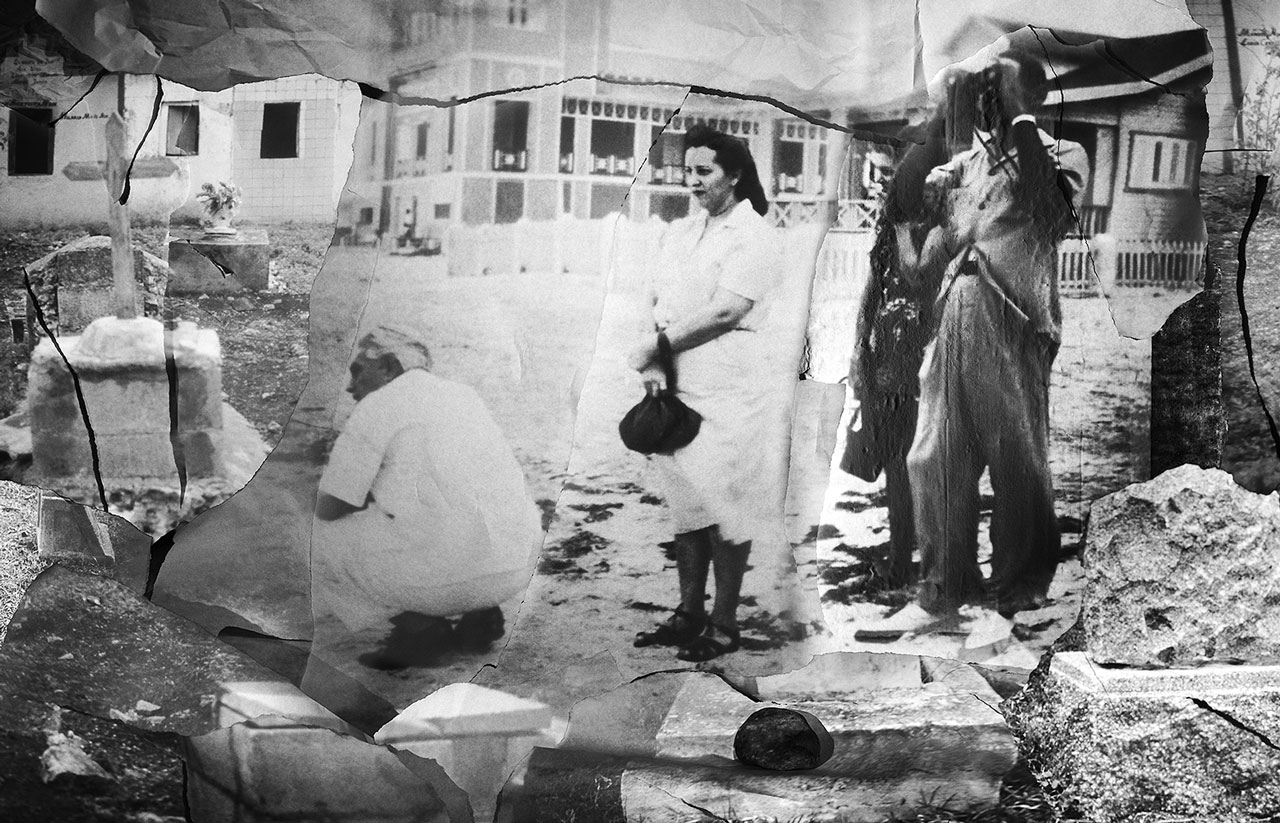

Traveling through his memories and belongings, Eduardo Muñoz Ordoqui constructs worlds and scenarios that are situated in indefinite space-times. Cautiously merging places and occasions, he composes in his series Low Tides, Portable Worlds and Without Rest photos that involve projected images, as well as objects and their reflections. He combines the tangible and the material to create a visual journey that evokes feelings of displacement, migration and uncertainty. The images tell the story of the search for meaning among places and memories.

Eduardo Muñoz Ordoqui (Cuba, 1964). Photographer. He received a Bachelor in Fine Arts degree in History of Art from the University of Havana in 1990 and a Master in Fine Arts in Studio Art from the University of Texas at Austin in 2005. He has taught photography for more than nine years in St. Edward’s University at Austin, Texas, where he is currently a Faculty Associate at the Department of Visual Studies. Muñoz-Ordoqui’s photographic work has been exhibited in solo and group shows in Europe, Latin America, China, and United States. He received a John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation Fellowship in 1997, a Cintas Foundation Fellowship in 1998 and in 2007 was chosen for the Artpace International Artist-in-Residence program in San Antonio, Texas, USA. His photographs are held in private and institutional collections in the Americas and Europe.

Eduardo Muñoz Ordoqui (Cuba, 1964). Photographer. He received a Bachelor in Fine Arts degree in History of Art from the University of Havana in 1990 and a Master in Fine Arts in Studio Art from the University of Texas at Austin in 2005. He has taught photography for more than nine years in St. Edward’s University at Austin, Texas, where he is currently a Faculty Associate at the Department of Visual Studies. Muñoz-Ordoqui’s photographic work has been exhibited in solo and group shows in Europe, Latin America, China, and United States. He received a John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation Fellowship in 1997, a Cintas Foundation Fellowship in 1998 and in 2007 was chosen for the Artpace International Artist-in-Residence program in San Antonio, Texas, USA. His photographs are held in private and institutional collections in the Americas and Europe.

Traveling through his memories and belongings, Eduardo Muñoz Ordoqui constructs worlds and scenarios that are situated in indefinite space-times. Cautiously merging places and occasions, he composes in his series Low Tides, Portable Worlds and Without Rest photos that involve projected images, as well as objects and their reflections. He combines the tangible and the material to create a visual journey that evokes feelings of displacement, migration and uncertainty. The images tell the story of the search for meaning among places and memories.

Eduardo Muñoz Ordoqui (Cuba, 1964). Photographer. He received a Bachelor in Fine Arts degree in History of Art from the University of Havana in 1990 and a Master in Fine Arts in Studio Art from the University of Texas at Austin in 2005. He has taught photography for more than nine years in St. Edward’s University at Austin, Texas, where he is currently a Faculty Associate at the Department of Visual Studies. Muñoz-Ordoqui’s photographic work has been exhibited in solo and group shows in Europe, Latin America, China, and United States. He received a John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation Fellowship in 1997, a Cintas Foundation Fellowship in 1998 and in 2007 was chosen for the Artpace International Artist-in-Residence program in San Antonio, Texas, USA. His photographs are held in private and institutional collections in the Americas and Europe.

Eduardo Muñoz Ordoqui (Cuba, 1964). Photographer. He received a Bachelor in Fine Arts degree in History of Art from the University of Havana in 1990 and a Master in Fine Arts in Studio Art from the University of Texas at Austin in 2005. He has taught photography for more than nine years in St. Edward’s University at Austin, Texas, where he is currently a Faculty Associate at the Department of Visual Studies. Muñoz-Ordoqui’s photographic work has been exhibited in solo and group shows in Europe, Latin America, China, and United States. He received a John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation Fellowship in 1997, a Cintas Foundation Fellowship in 1998 and in 2007 was chosen for the Artpace International Artist-in-Residence program in San Antonio, Texas, USA. His photographs are held in private and institutional collections in the Americas and Europe.Kent Krugh

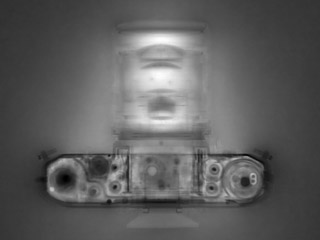

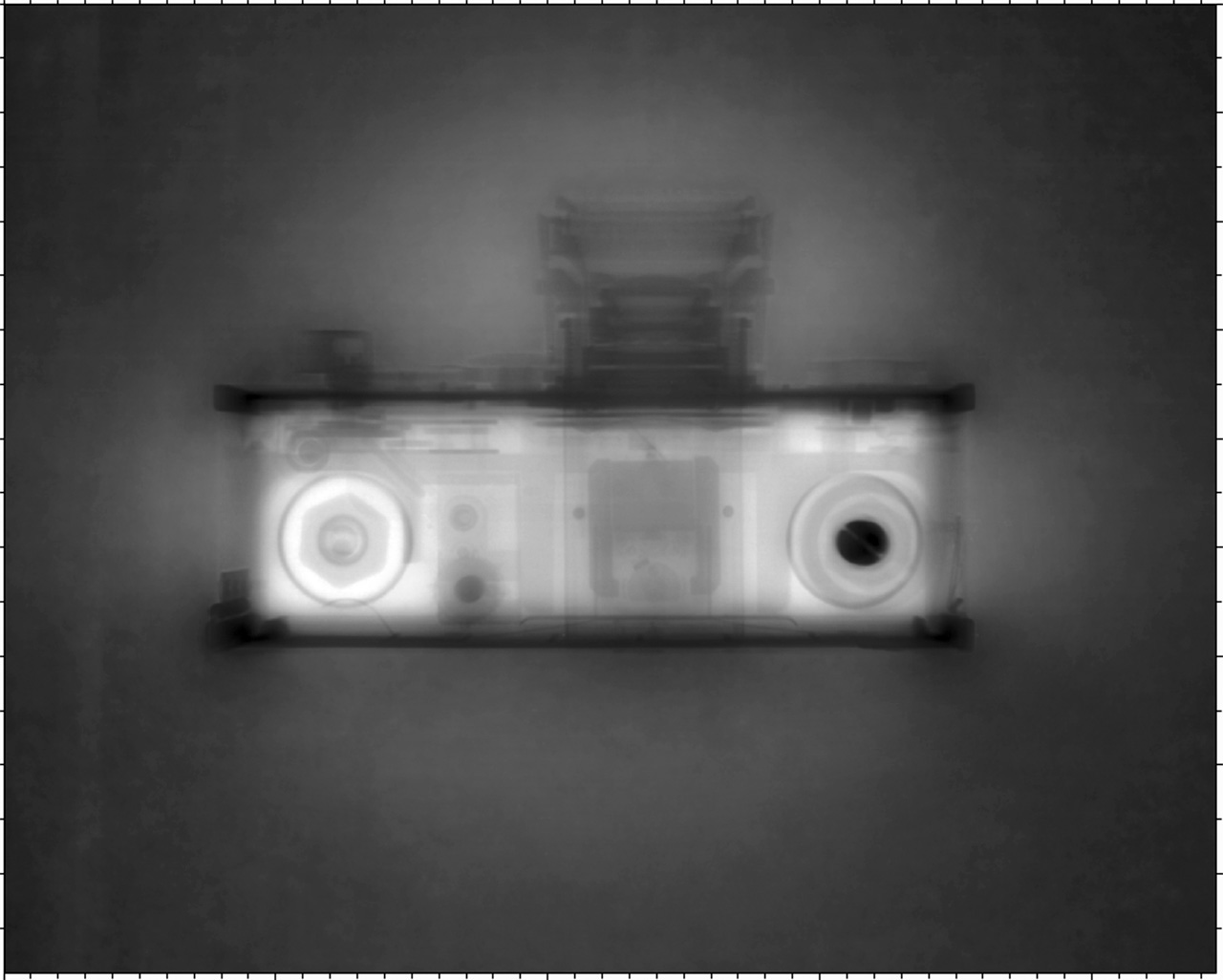

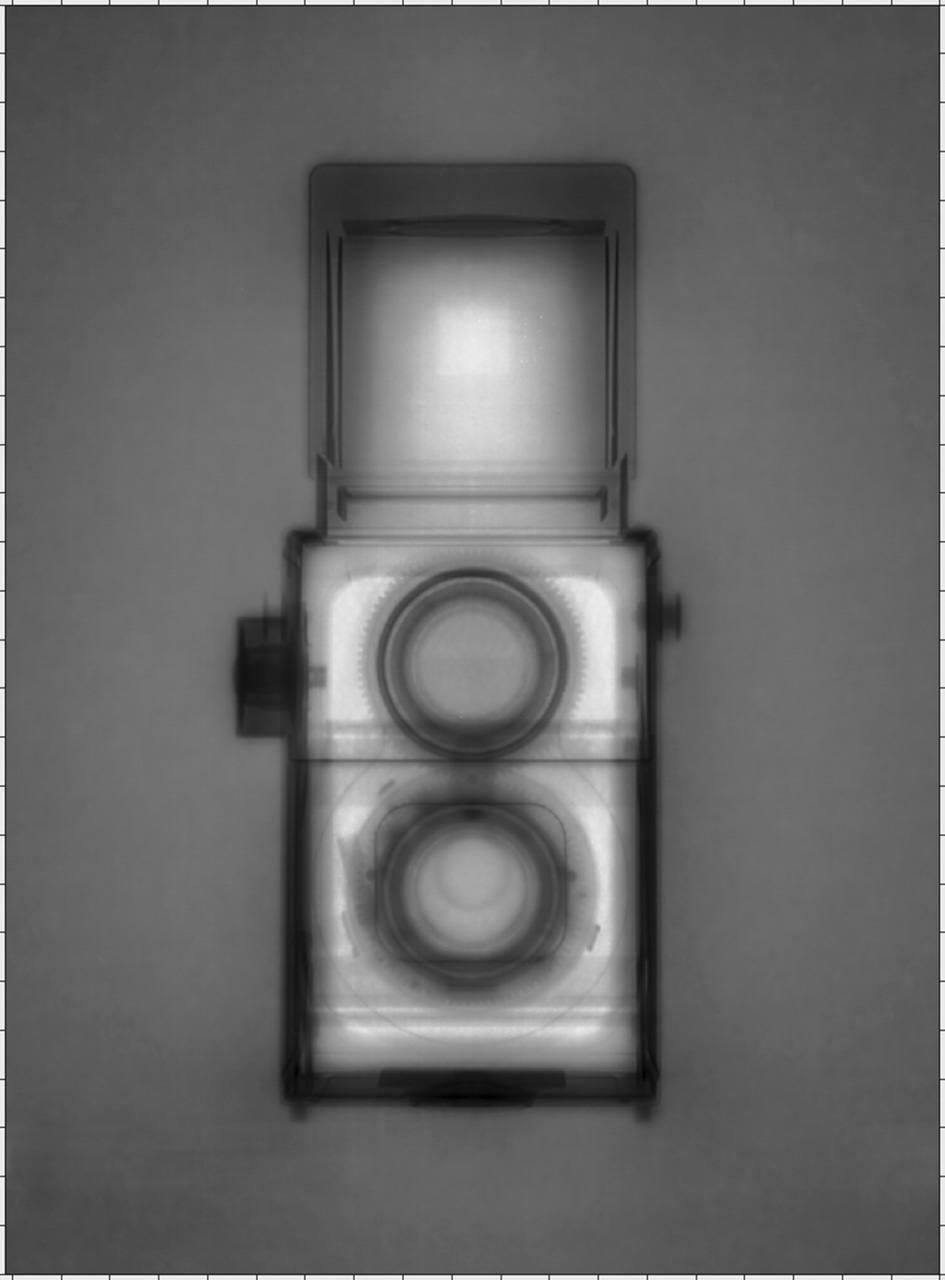

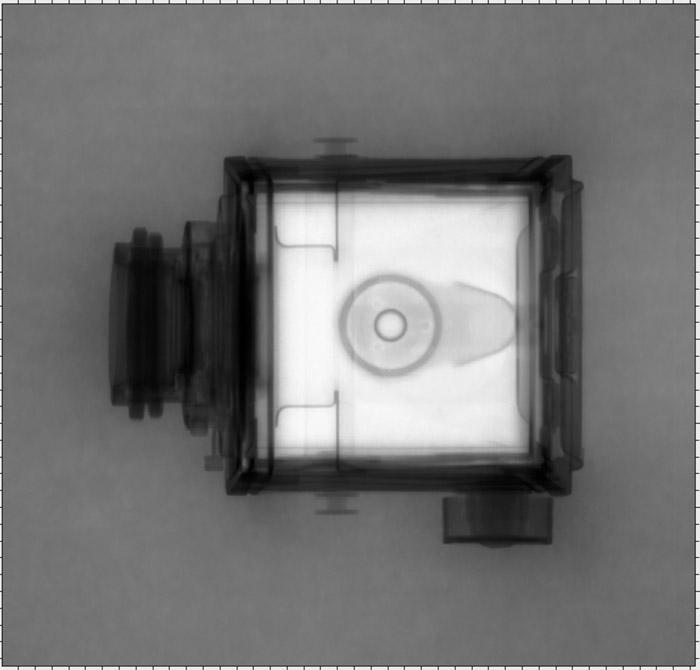

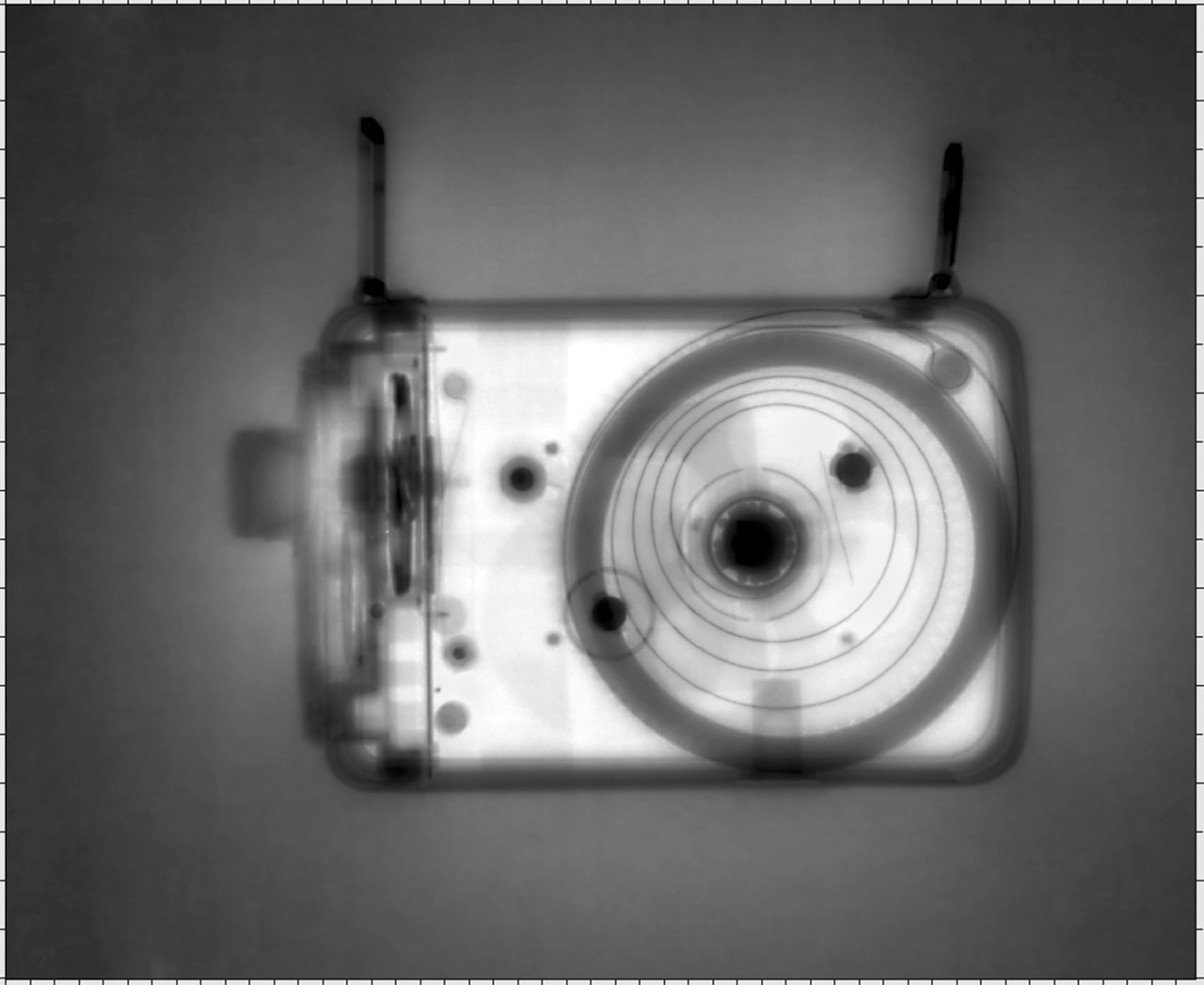

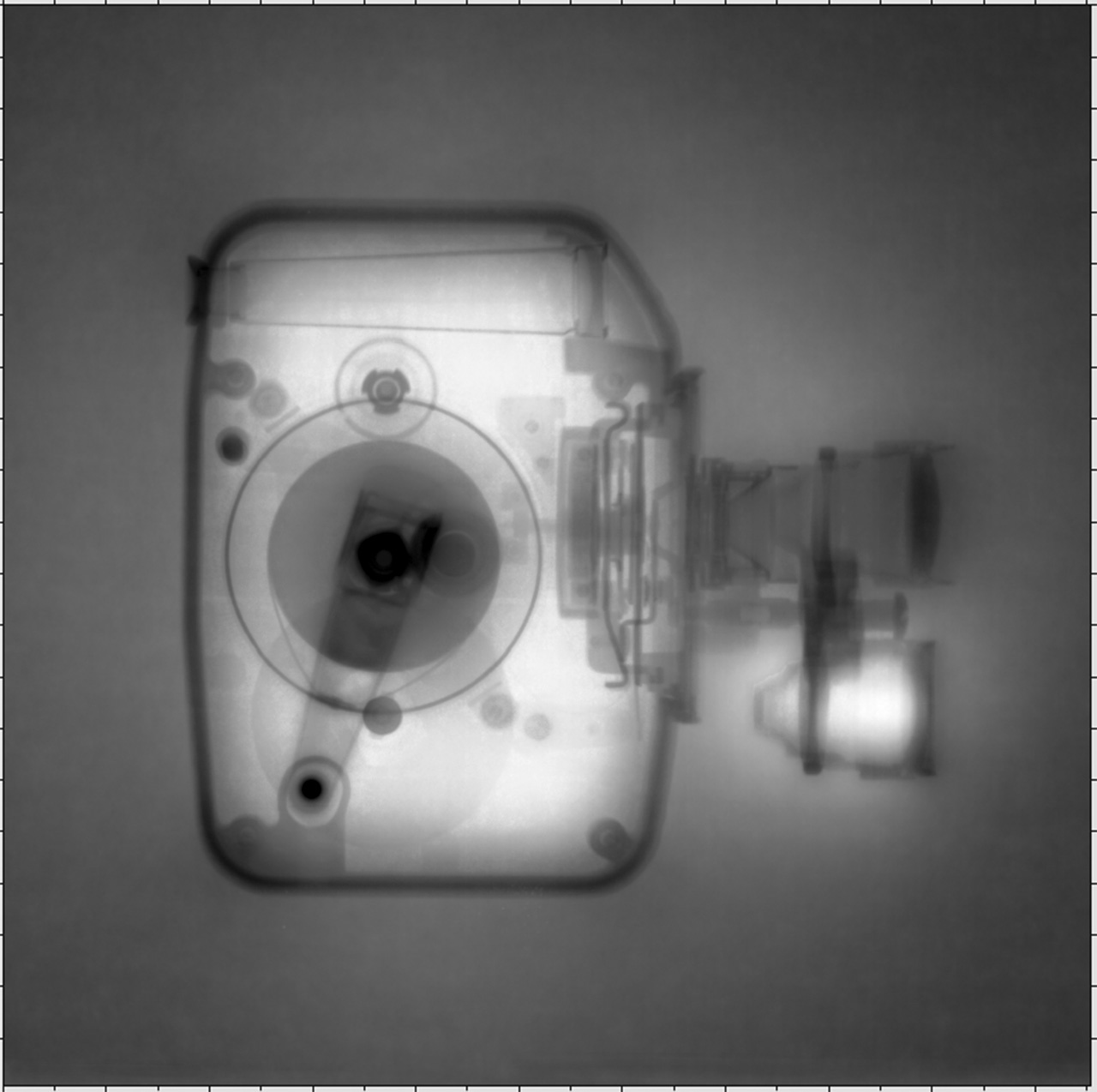

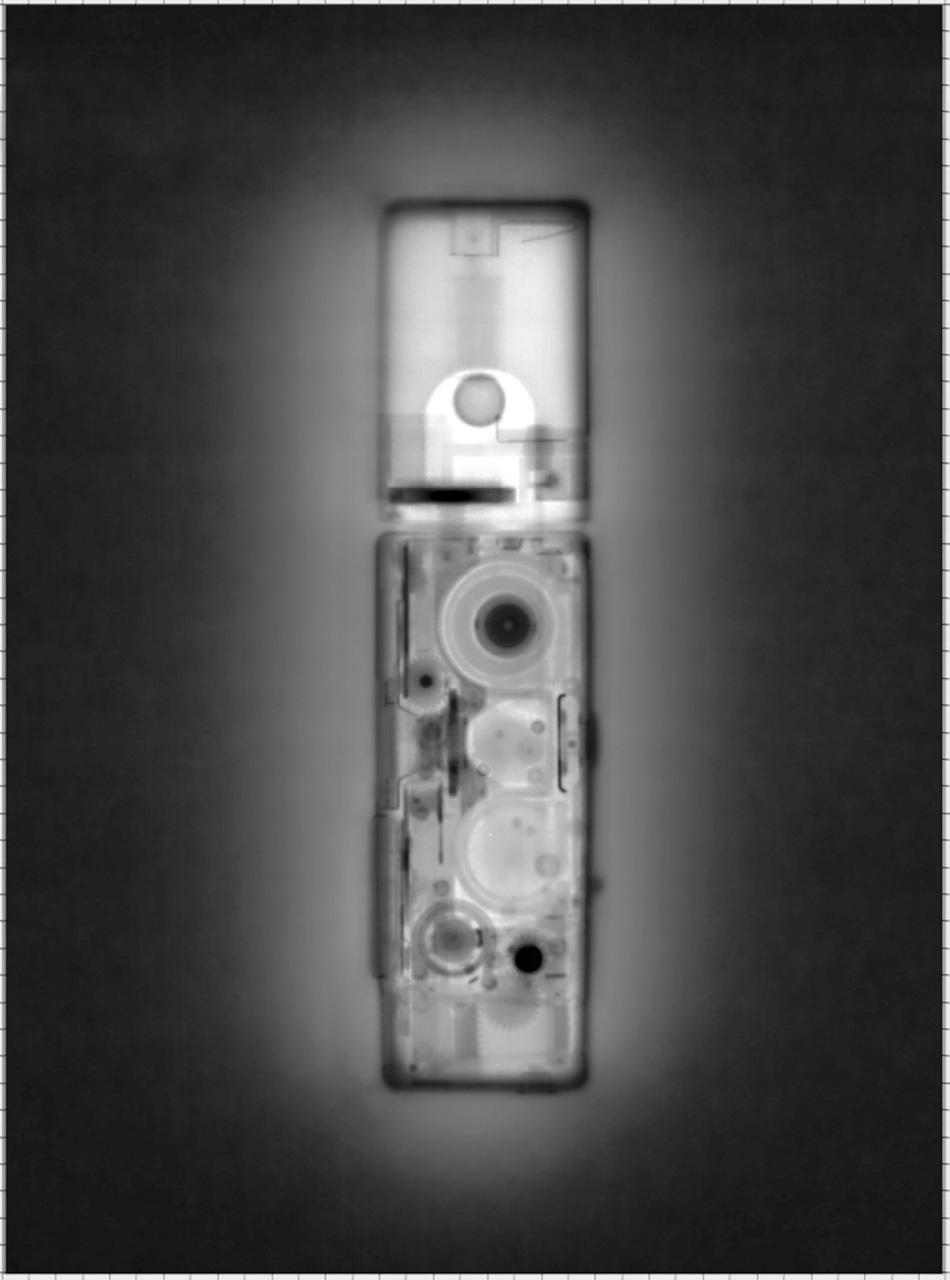

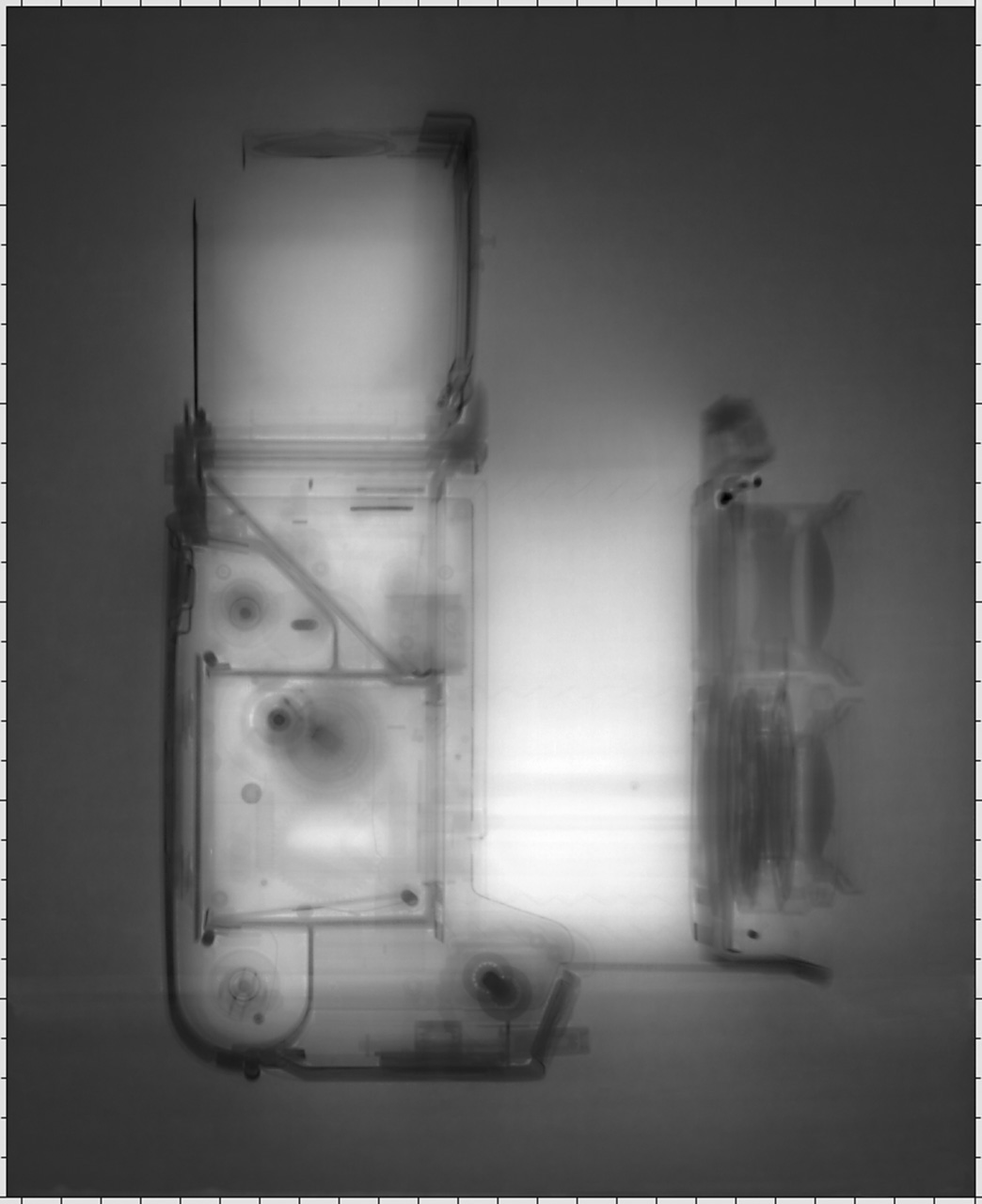

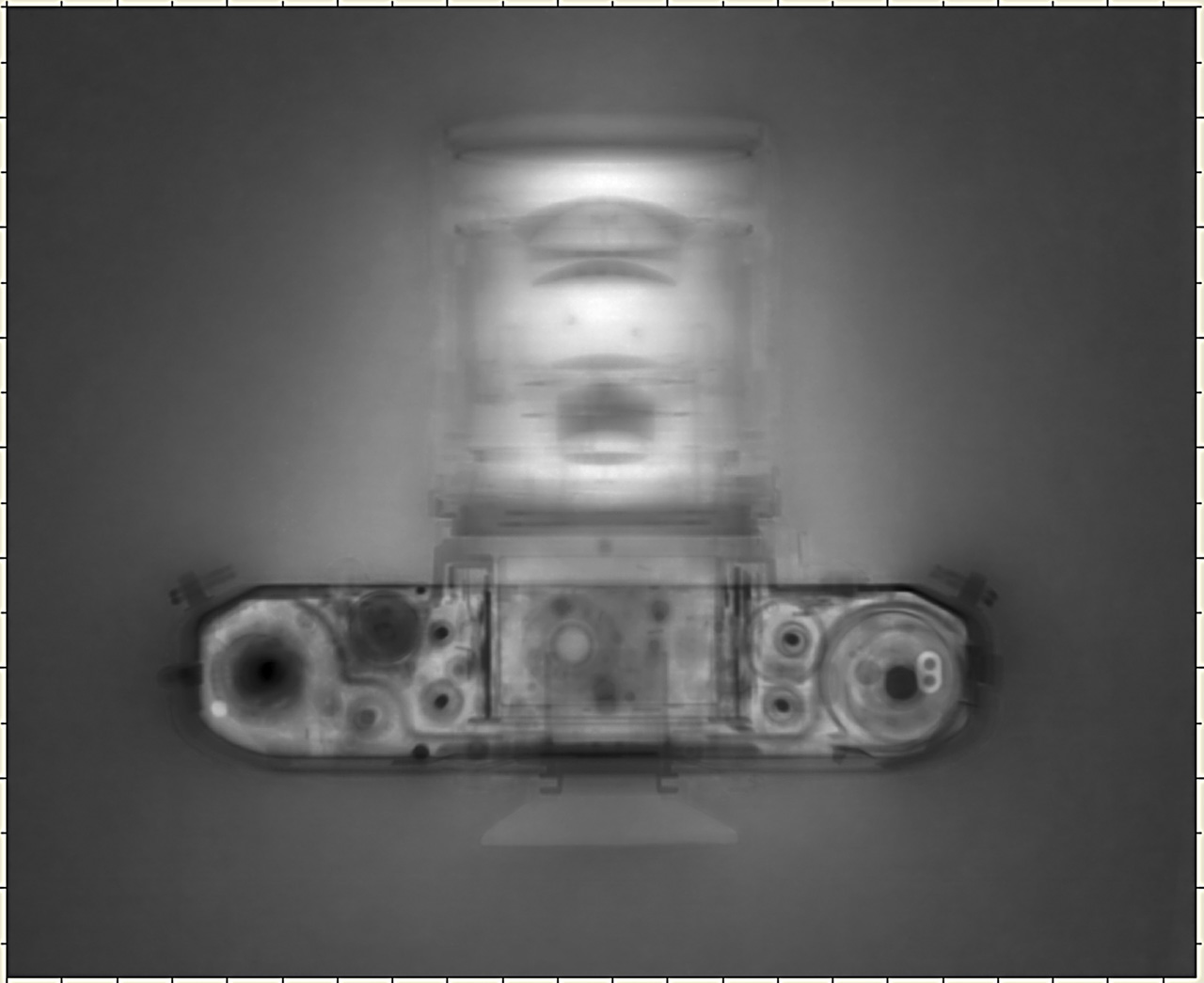

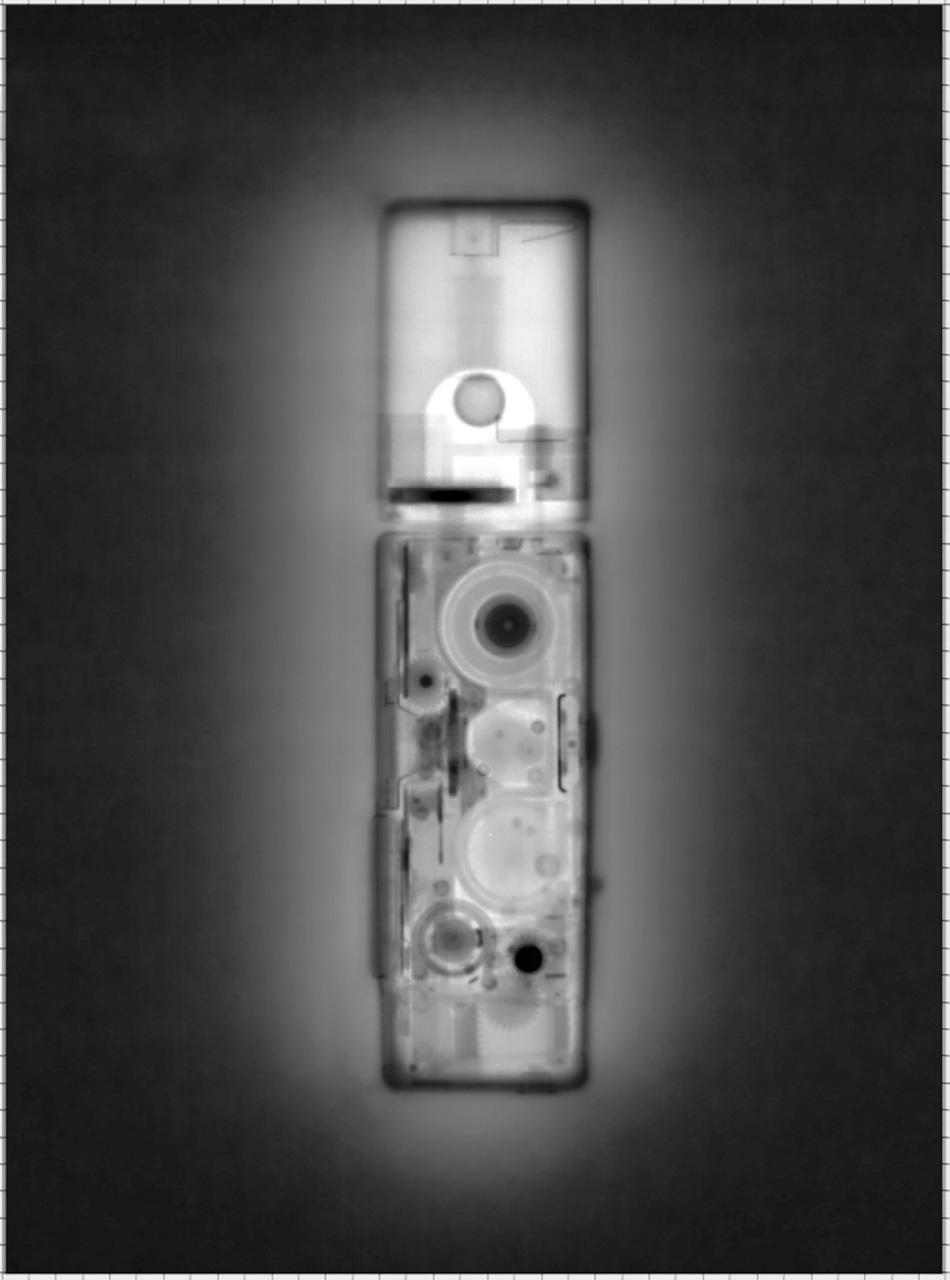

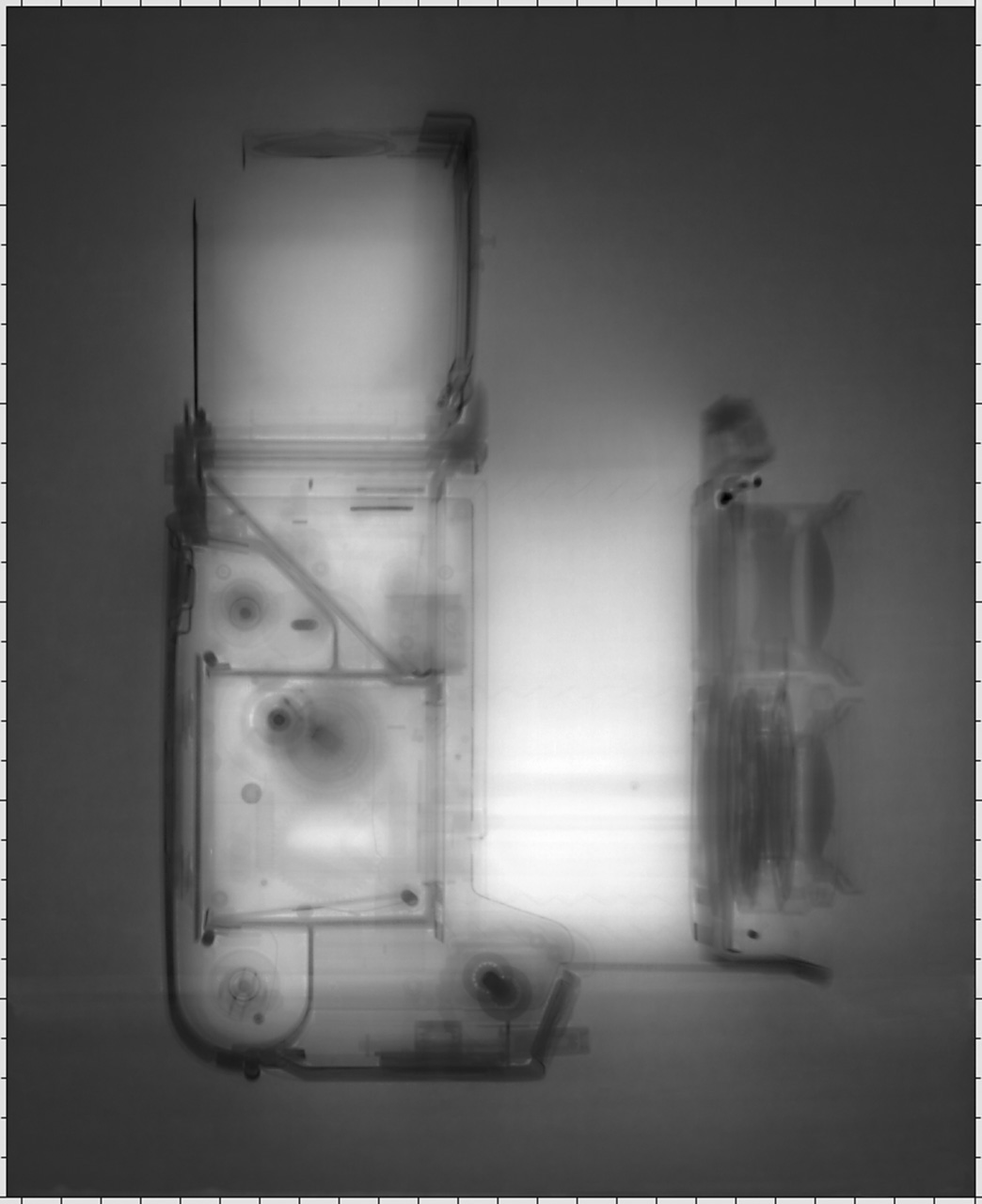

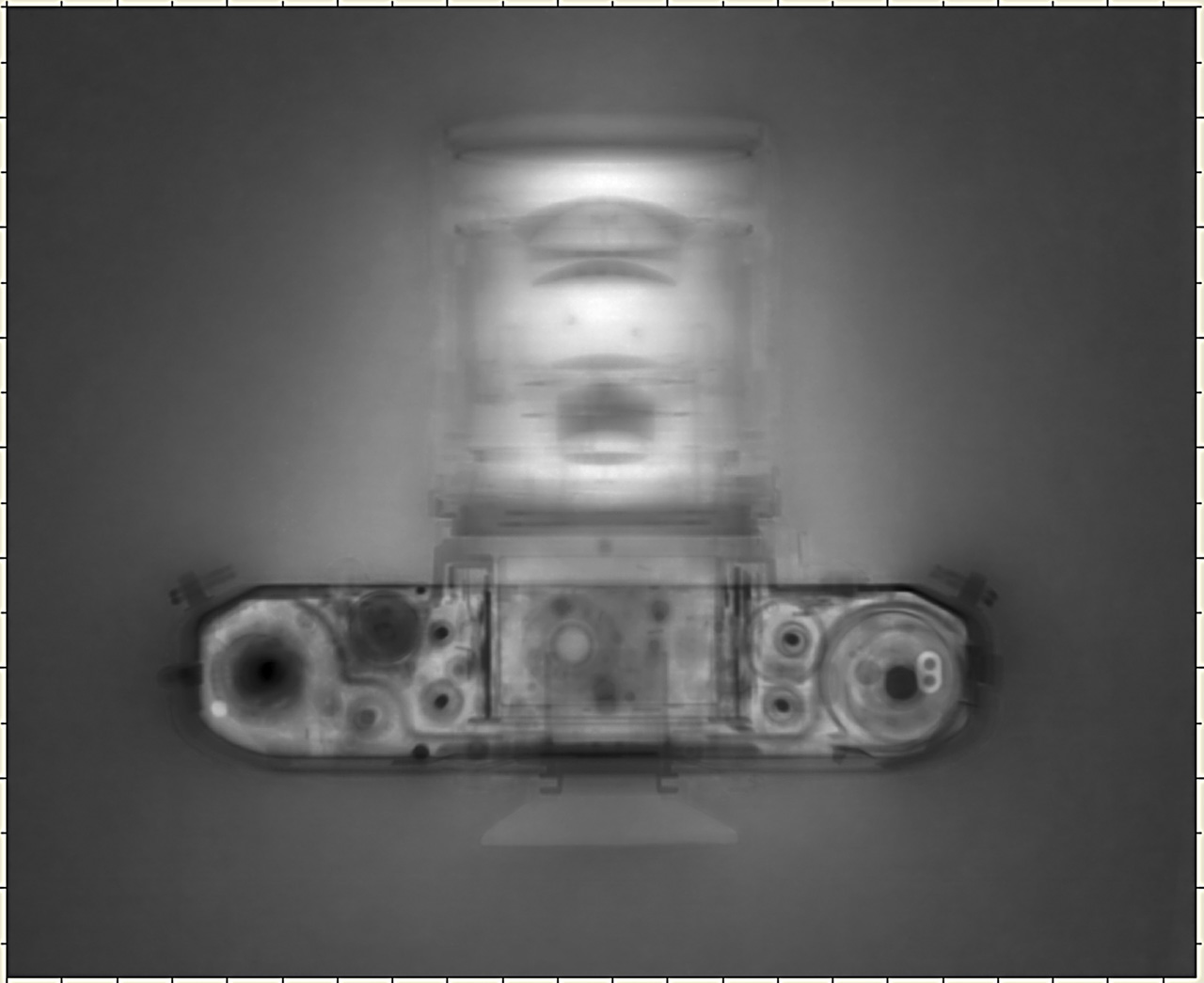

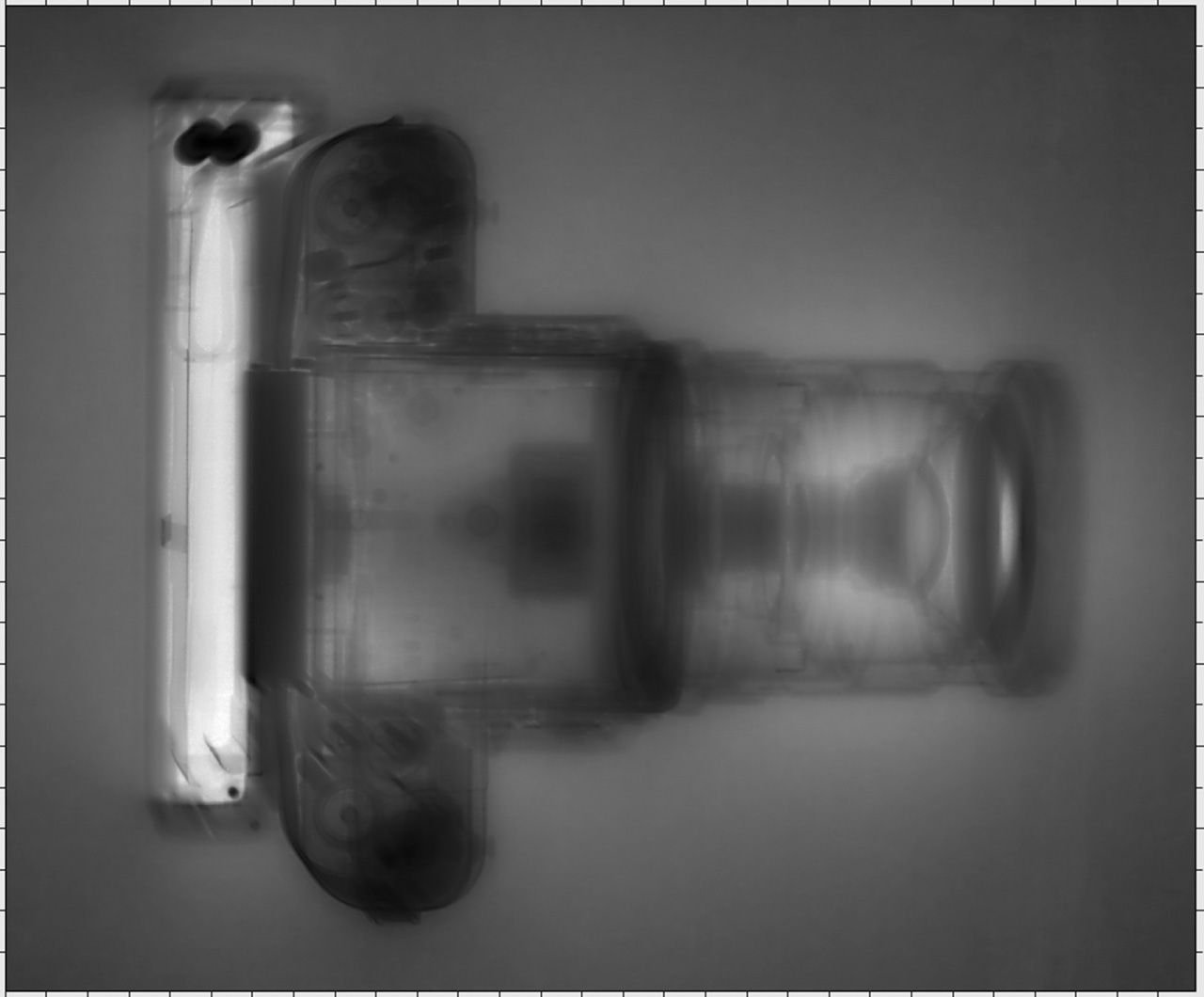

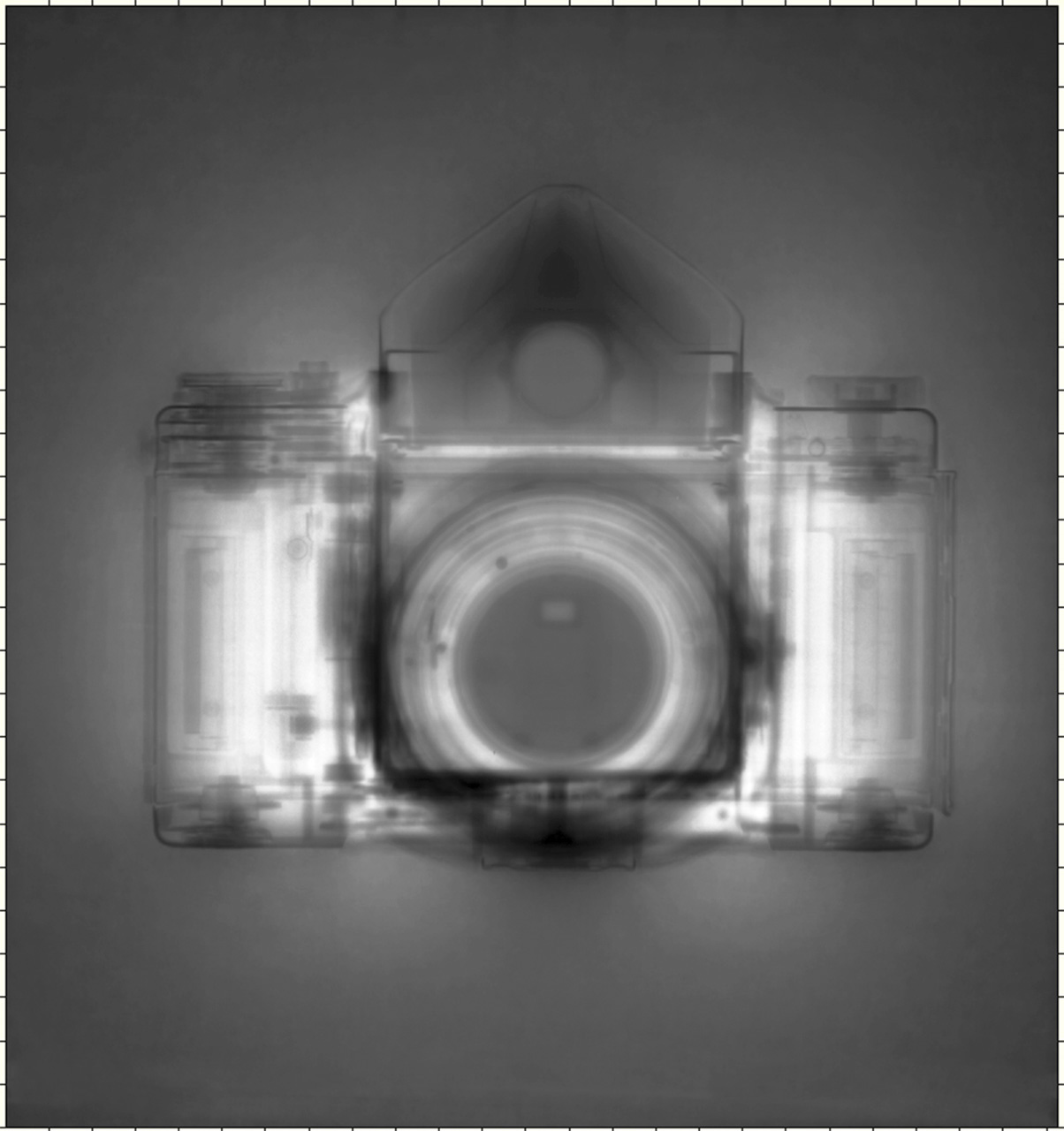

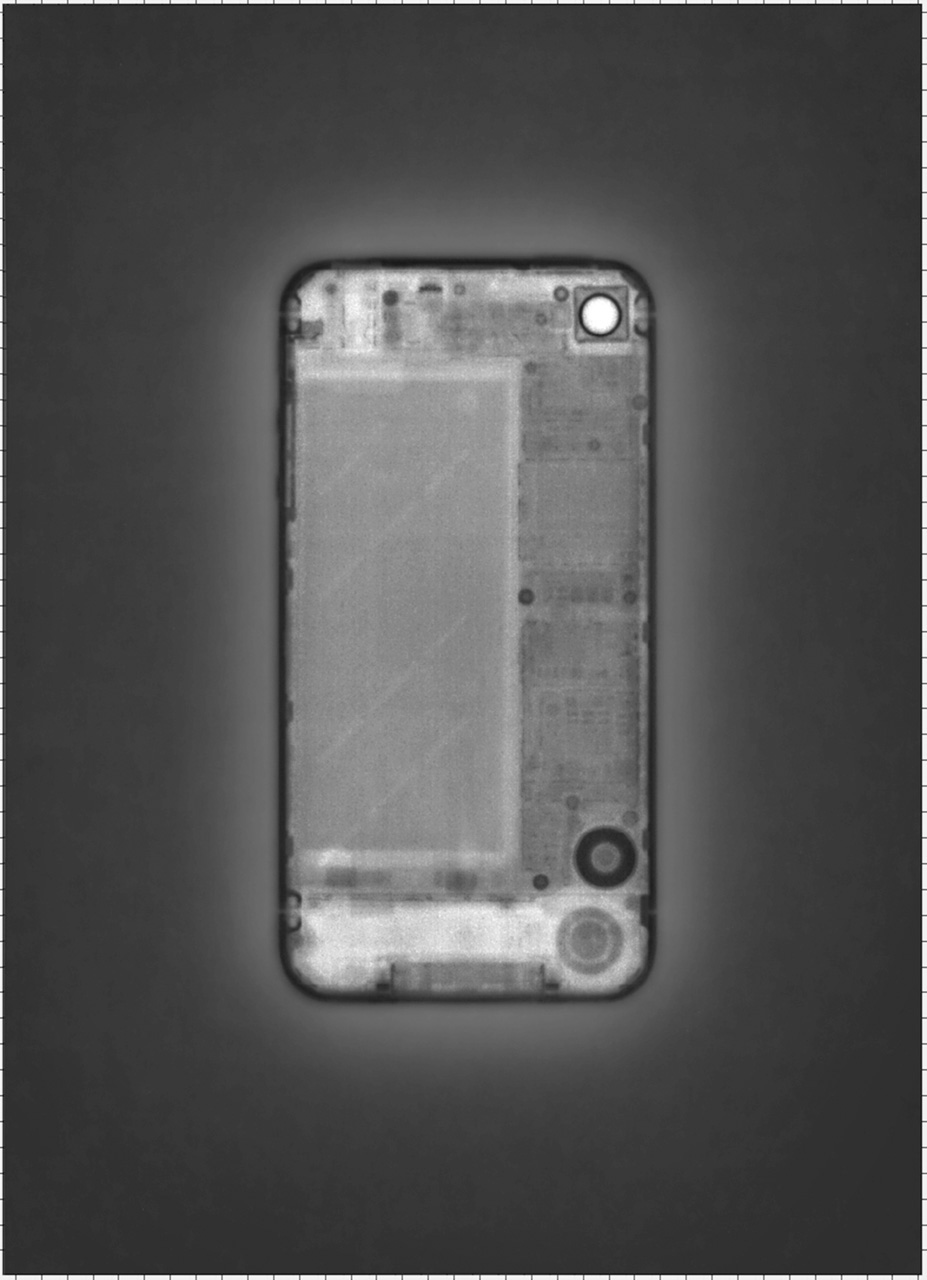

This body of work, using linear accelerator x-rays of cameras, explores the micro-evolution of cameras over time. While form and media may have changed, the camera is still a camera: a tool to create images by capturing photons of light. In a sense, it is an homage to the cameras I have used and handled. A linear accelerator produces high energy particles and x-rays and is used in physics research and health care to treat cancer patients. The resulting images align with an inner desire to probe those unseen spaces and realms I sense exist, but do not observe with my eyes.

Kent Krugh is a fine art photographer, living and working in Greater Cincinnati, OH. Ten years ago he decided to dedicate himself to photography. He has received numerous awards in national and international competitions and was a Photolucida 2012 and 2014 Critical Mass Finalist.. His work has been exhibited in national and international group and solo venues. He also taught workshops in collaboration with Colegiatura Colombiana del Diseño, Fundación Universitaria de Bellas Artes and Centro Colombo Americano under the auspices of the Universidad de Antioquia. Krugh’s work has been exhibited at three major festivals: Fringe Festival 2010, Cincinnati, OH; FotoFest Biennial 2012, Houston, TX; and FotoFocus Biennial 2012, Cincinnati, OH. Krugh's work can be found in numerous private collections and museums including the Portland Art Museum and the Cleveland Museum of Art.

Kent Krugh is a fine art photographer, living and working in Greater Cincinnati, OH. Ten years ago he decided to dedicate himself to photography. He has received numerous awards in national and international competitions and was a Photolucida 2012 and 2014 Critical Mass Finalist.. His work has been exhibited in national and international group and solo venues. He also taught workshops in collaboration with Colegiatura Colombiana del Diseño, Fundación Universitaria de Bellas Artes and Centro Colombo Americano under the auspices of the Universidad de Antioquia. Krugh’s work has been exhibited at three major festivals: Fringe Festival 2010, Cincinnati, OH; FotoFest Biennial 2012, Houston, TX; and FotoFocus Biennial 2012, Cincinnati, OH. Krugh's work can be found in numerous private collections and museums including the Portland Art Museum and the Cleveland Museum of Art.[core_state] => 1 [core_access] => 1 [core_metadata] => {"robots":"","author":"Kent Krugh","rights":"","xreference":""} [core_created_user_id] => 838 [core_created_by_alias] => [core_created_time] => 2015-02-10 21:22:20 [core_images] => {"image_intro":"images\/categories\/open-content\/krugh.jpg","float_intro":"","image_intro_alt":"","image_intro_caption":"","image_fulltext":"images\/categories\/open-content\/krugh.jpg","float_fulltext":"","image_fulltext_alt":"","image_fulltext_caption":""} [core_modified_time] => 2016-06-22 18:25:45 [core_language] => en-GB [core_catid] => 37 [core_publish_up] => 2015-02-10 21:22:20 [core_publish_down] => 0000-00-00 00:00:00 [content_type_title] => Article [router] => ContentHelperRoute::getArticleRoute [author] => Elisa Rugo [author_email] => elisa@zonezero.com [link] => index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=248:speciation&catid=37&lang=en-GB [displayDate] => 2015-02-10 21:22:20 [event] => stdClass Object ( [afterDisplayTitle] => [beforeDisplayContent] => [afterDisplayContent] => ) [text] =>

This body of work, using linear accelerator x-rays of cameras, explores the micro-evolution of cameras over time. While form and media may have changed, the camera is still a camera: a tool to create images by capturing photons of light. In a sense, it is an homage to the cameras I have used and handled. A linear accelerator produces high energy particles and x-rays and is used in physics research and health care to treat cancer patients. The resulting images align with an inner desire to probe those unseen spaces and realms I sense exist, but do not observe with my eyes.

Kent Krugh is a fine art photographer, living and working in Greater Cincinnati, OH. Ten years ago he decided to dedicate himself to photography. He has received numerous awards in national and international competitions and was a Photolucida 2012 and 2014 Critical Mass Finalist.. His work has been exhibited in national and international group and solo venues. He also taught workshops in collaboration with Colegiatura Colombiana del Diseño, Fundación Universitaria de Bellas Artes and Centro Colombo Americano under the auspices of the Universidad de Antioquia. Krugh’s work has been exhibited at three major festivals: Fringe Festival 2010, Cincinnati, OH; FotoFest Biennial 2012, Houston, TX; and FotoFocus Biennial 2012, Cincinnati, OH. Krugh's work can be found in numerous private collections and museums including the Portland Art Museum and the Cleveland Museum of Art.

Kent Krugh is a fine art photographer, living and working in Greater Cincinnati, OH. Ten years ago he decided to dedicate himself to photography. He has received numerous awards in national and international competitions and was a Photolucida 2012 and 2014 Critical Mass Finalist.. His work has been exhibited in national and international group and solo venues. He also taught workshops in collaboration with Colegiatura Colombiana del Diseño, Fundación Universitaria de Bellas Artes and Centro Colombo Americano under the auspices of the Universidad de Antioquia. Krugh’s work has been exhibited at three major festivals: Fringe Festival 2010, Cincinnati, OH; FotoFest Biennial 2012, Houston, TX; and FotoFocus Biennial 2012, Cincinnati, OH. Krugh's work can be found in numerous private collections and museums including the Portland Art Museum and the Cleveland Museum of Art.[id] => 248 [language] => en-GB [catid] => 37 [jcfields] => Array ( ) ) 1

Matthew Hashiguchi

Good Luck Soup

Good Luck SoupIs a transmedia storytelling project documenting and sharing stories of the Japanese American and Japanese Canadian experience after they left the internment camps. The project consists of a feature-length documentary film, titled Good Luck Soup and an interactive, participatory website, Good Luck Soup Interactive. On this website stories will be told through uploaded text and photographs from internment camp victims, or their families, and will be shared through an interactive website and map.

People Aren't All Bad

People Aren't All BadZZ. What has been the reaction of the public to your invitation to participate in your transmedia storytelling project?

MH. We've had a consistently positive response from the Japanese American/Canadian community. Initially, I think many have been nervous about sharing their own stories and experiences, but once we sit down with them and talk about their life, they tend to open up. It's been a form of catharsis, I think, because many people have never discussed their issues or experiences of being Japanese American/Canadian... and some of these things are very difficult topics or thoughts that have been bottled up. So, it's a very emotional experience to share these thoughts and feelings. We haven't yet opened it up to the general public, but again, everyone has been consistently positive, and I have no reason to think the reaction will be any different once its available to all Japanese Americans and Japanese Canadians.

ZZ. What means of publicity are you using or are you planning to use for the diffusion of the project?

MH. Social media will be a huge tool for publicity and marketing. We've already reached and met so many people through Twitter and Facebook, and we'll certainly continue to utilize those outlets. We've been in communication with many Asian American and Asian Canadian organizations that have offered their support once the project is complete, and the opportunity to collaborate with entities such as the Japanese American Citizens League, the Japanese American National Museum and the Nikkei National Museum would be priceless. We're certainly inspired by their mission and view our project as a continuation of what they offer the public.

In addition to the interactive documentary, this project also includes a feature length film. Film festivals will be another great opportunity to screen the film and present the interactive project to an audience.

ZZ. Can you share with us how you have experienced the realisation, dissemination and the reach of the project thus far?

MH. It's been a very gradual and collaborative process, and luckily I have an incredible team of colleagues and friends that have made the realization of this project possible, and without their help, I would not have been able to get this project made. The work load is split up fairly well. Right now, our web-designer/coder (Russell Goldenberg) is building the site. He's the one sitting alone typing away at his computer. Every few weeks, we'll all have a meeting where we discuss the direction of the project... and then Russell goes and brings it to life. Billy Wirasnik, Emily Ferrier and myself and have been in charge of content aggregation. So we're narrowing the aim of the stories and in many cases, going out and finding those stories and individuals. It's a solid collaboration made up of various creative visions, rather than one. And, as the Project Creator, I really enjoy a hands-off approach that allows individuals to run off with an idea and make it their own.

Matthew Hashiguchi (1984). Based in Boston, Massachusetts. After graduating from The Ohio State University in 2007 with a BA in Photojournalism, Matthew went on to work and intern as a multimedia journalist for The Findlay Courier, The Lima News and The Washington Post. In 2008, he returned to school and graduated from Emerson College with an MFA in Visual and Media Art and has since been working as an independent documentary filmmaker and educator, whose work focuses on the diverse cultural, social and ethnic stories of American society. For his film The Lower 9 he has received various awards.

Matthew Hashiguchi (1984). Based in Boston, Massachusetts. After graduating from The Ohio State University in 2007 with a BA in Photojournalism, Matthew went on to work and intern as a multimedia journalist for The Findlay Courier, The Lima News and The Washington Post. In 2008, he returned to school and graduated from Emerson College with an MFA in Visual and Media Art and has since been working as an independent documentary filmmaker and educator, whose work focuses on the diverse cultural, social and ethnic stories of American society. For his film The Lower 9 he has received various awards. Good Luck Soup

Good Luck SoupIs a transmedia storytelling project documenting and sharing stories of the Japanese American and Japanese Canadian experience after they left the internment camps. The project consists of a feature-length documentary film, titled Good Luck Soup and an interactive, participatory website, Good Luck Soup Interactive. On this website stories will be told through uploaded text and photographs from internment camp victims, or their families, and will be shared through an interactive website and map.

People Aren't All Bad

People Aren't All BadZZ. What has been the reaction of the public to your invitation to participate in your transmedia storytelling project?

MH. We've had a consistently positive response from the Japanese American/Canadian community. Initially, I think many have been nervous about sharing their own stories and experiences, but once we sit down with them and talk about their life, they tend to open up. It's been a form of catharsis, I think, because many people have never discussed their issues or experiences of being Japanese American/Canadian... and some of these things are very difficult topics or thoughts that have been bottled up. So, it's a very emotional experience to share these thoughts and feelings. We haven't yet opened it up to the general public, but again, everyone has been consistently positive, and I have no reason to think the reaction will be any different once its available to all Japanese Americans and Japanese Canadians.

ZZ. What means of publicity are you using or are you planning to use for the diffusion of the project?

MH. Social media will be a huge tool for publicity and marketing. We've already reached and met so many people through Twitter and Facebook, and we'll certainly continue to utilize those outlets. We've been in communication with many Asian American and Asian Canadian organizations that have offered their support once the project is complete, and the opportunity to collaborate with entities such as the Japanese American Citizens League, the Japanese American National Museum and the Nikkei National Museum would be priceless. We're certainly inspired by their mission and view our project as a continuation of what they offer the public.

In addition to the interactive documentary, this project also includes a feature length film. Film festivals will be another great opportunity to screen the film and present the interactive project to an audience.

ZZ. Can you share with us how you have experienced the realisation, dissemination and the reach of the project thus far?

MH. It's been a very gradual and collaborative process, and luckily I have an incredible team of colleagues and friends that have made the realization of this project possible, and without their help, I would not have been able to get this project made. The work load is split up fairly well. Right now, our web-designer/coder (Russell Goldenberg) is building the site. He's the one sitting alone typing away at his computer. Every few weeks, we'll all have a meeting where we discuss the direction of the project... and then Russell goes and brings it to life. Billy Wirasnik, Emily Ferrier and myself and have been in charge of content aggregation. So we're narrowing the aim of the stories and in many cases, going out and finding those stories and individuals. It's a solid collaboration made up of various creative visions, rather than one. And, as the Project Creator, I really enjoy a hands-off approach that allows individuals to run off with an idea and make it their own.

Matthew Hashiguchi (1984). Based in Boston, Massachusetts. After graduating from The Ohio State University in 2007 with a BA in Photojournalism, Matthew went on to work and intern as a multimedia journalist for The Findlay Courier, The Lima News and The Washington Post. In 2008, he returned to school and graduated from Emerson College with an MFA in Visual and Media Art and has since been working as an independent documentary filmmaker and educator, whose work focuses on the diverse cultural, social and ethnic stories of American society. For his film The Lower 9 he has received various awards.

Matthew Hashiguchi (1984). Based in Boston, Massachusetts. After graduating from The Ohio State University in 2007 with a BA in Photojournalism, Matthew went on to work and intern as a multimedia journalist for The Findlay Courier, The Lima News and The Washington Post. In 2008, he returned to school and graduated from Emerson College with an MFA in Visual and Media Art and has since been working as an independent documentary filmmaker and educator, whose work focuses on the diverse cultural, social and ethnic stories of American society. For his film The Lower 9 he has received various awards.Josef Wladyka

My mother left Japan more than thirty years ago and didn't return until November 2010. This is her story.

Location: Tokyo, Japan.

Cinematography: Stan Wladyka.

Music: Tyler Parkinson.

Okaasan お母さん

Beginning as a child performer in Odessa, Russia, Albert Makhtsier has been acting for over half a century. Despite being diagnosed with Parkinson's disease, Albert remains one of New York City's finest actors. This is his story.

Location: Times Square, New York City.

Cinematography: Alan Blanco.

Music: Tyler Cash.

Albert Makhtsier

Curai is a small, tight knit fishing village on the Southern Pacific Coast of Colombia. It's a place where almost everyone shares the same last name. Jacobo is a community leader there and this is one of his stories.

Location: Curai, Colombia.

Cinematography by Leonardo D'Antoni.

Music by Tyler Cash.

Jacobo Castillo Salazar

These are a collection of peoples' personal stories told through a single shot. Each story is an exploration of the universal essence of the human condition and our connection to one another that extends beyond any boundaries.

Josef Wladyka. Lives in New York. Influenced by his parents, Josef developed a fascination for movies from a very young age. He began experimenting with filmmaking in high school and has since created several (short) films and commercials that have been screened at festivals around the world. He holds a MFA from NYU Tisch Graduate Film where he won a Spike Lee Fellowship. His debut feature film, Manos Sucias (2014), has won various awards.

Josef Wladyka. Lives in New York. Influenced by his parents, Josef developed a fascination for movies from a very young age. He began experimenting with filmmaking in high school and has since created several (short) films and commercials that have been screened at festivals around the world. He holds a MFA from NYU Tisch Graduate Film where he won a Spike Lee Fellowship. His debut feature film, Manos Sucias (2014), has won various awards.

My mother left Japan more than thirty years ago and didn't return until November 2010. This is her story.

Location: Tokyo, Japan.

Cinematography: Stan Wladyka.

Music: Tyler Parkinson.

Okaasan お母さん

Beginning as a child performer in Odessa, Russia, Albert Makhtsier has been acting for over half a century. Despite being diagnosed with Parkinson's disease, Albert remains one of New York City's finest actors. This is his story.

Location: Times Square, New York City.

Cinematography: Alan Blanco.

Music: Tyler Cash.

Albert Makhtsier

Curai is a small, tight knit fishing village on the Southern Pacific Coast of Colombia. It's a place where almost everyone shares the same last name. Jacobo is a community leader there and this is one of his stories.

Location: Curai, Colombia.

Cinematography by Leonardo D'Antoni.

Music by Tyler Cash.

Jacobo Castillo Salazar

These are a collection of peoples' personal stories told through a single shot. Each story is an exploration of the universal essence of the human condition and our connection to one another that extends beyond any boundaries.

Josef Wladyka. Lives in New York. Influenced by his parents, Josef developed a fascination for movies from a very young age. He began experimenting with filmmaking in high school and has since created several (short) films and commercials that have been screened at festivals around the world. He holds a MFA from NYU Tisch Graduate Film where he won a Spike Lee Fellowship. His debut feature film, Manos Sucias (2014), has won various awards.

Josef Wladyka. Lives in New York. Influenced by his parents, Josef developed a fascination for movies from a very young age. He began experimenting with filmmaking in high school and has since created several (short) films and commercials that have been screened at festivals around the world. He holds a MFA from NYU Tisch Graduate Film where he won a Spike Lee Fellowship. His debut feature film, Manos Sucias (2014), has won various awards.Rania Matar

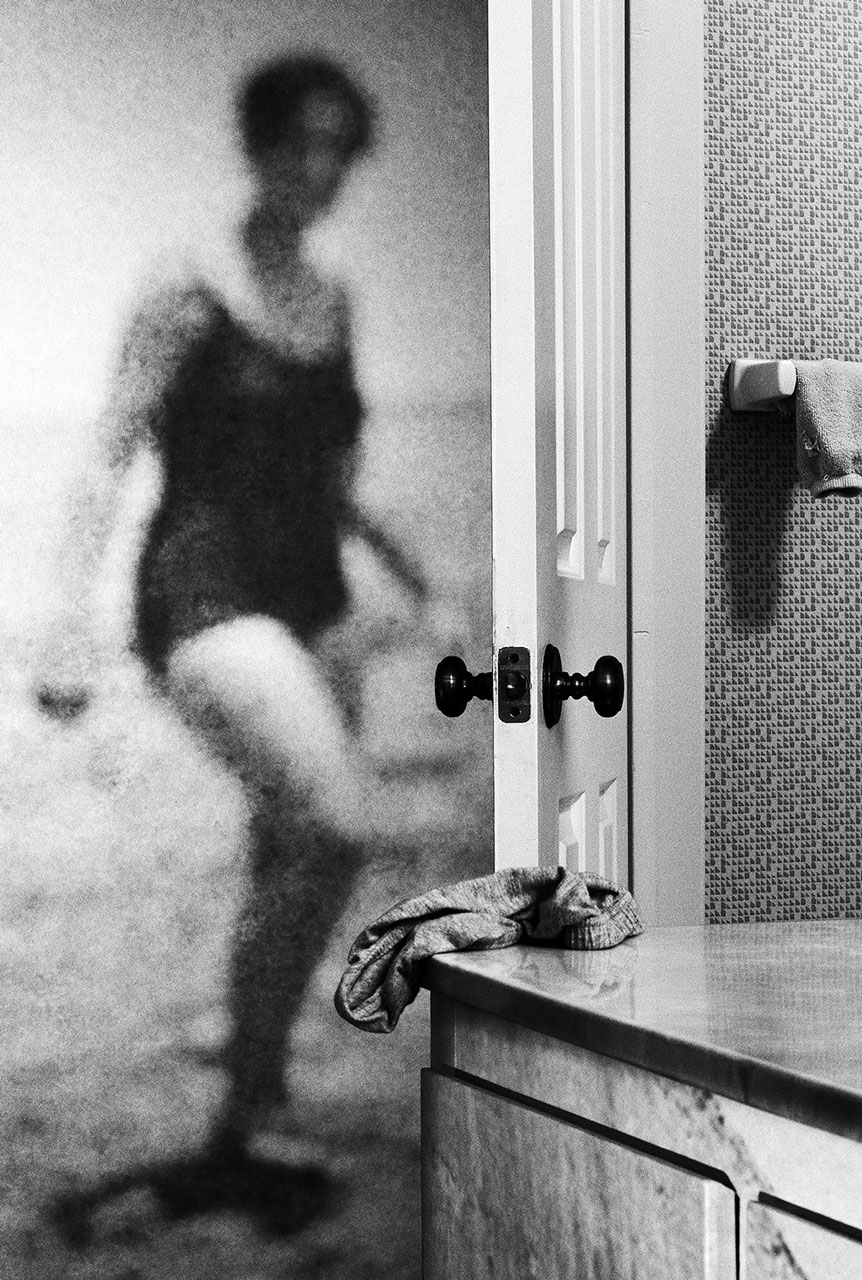

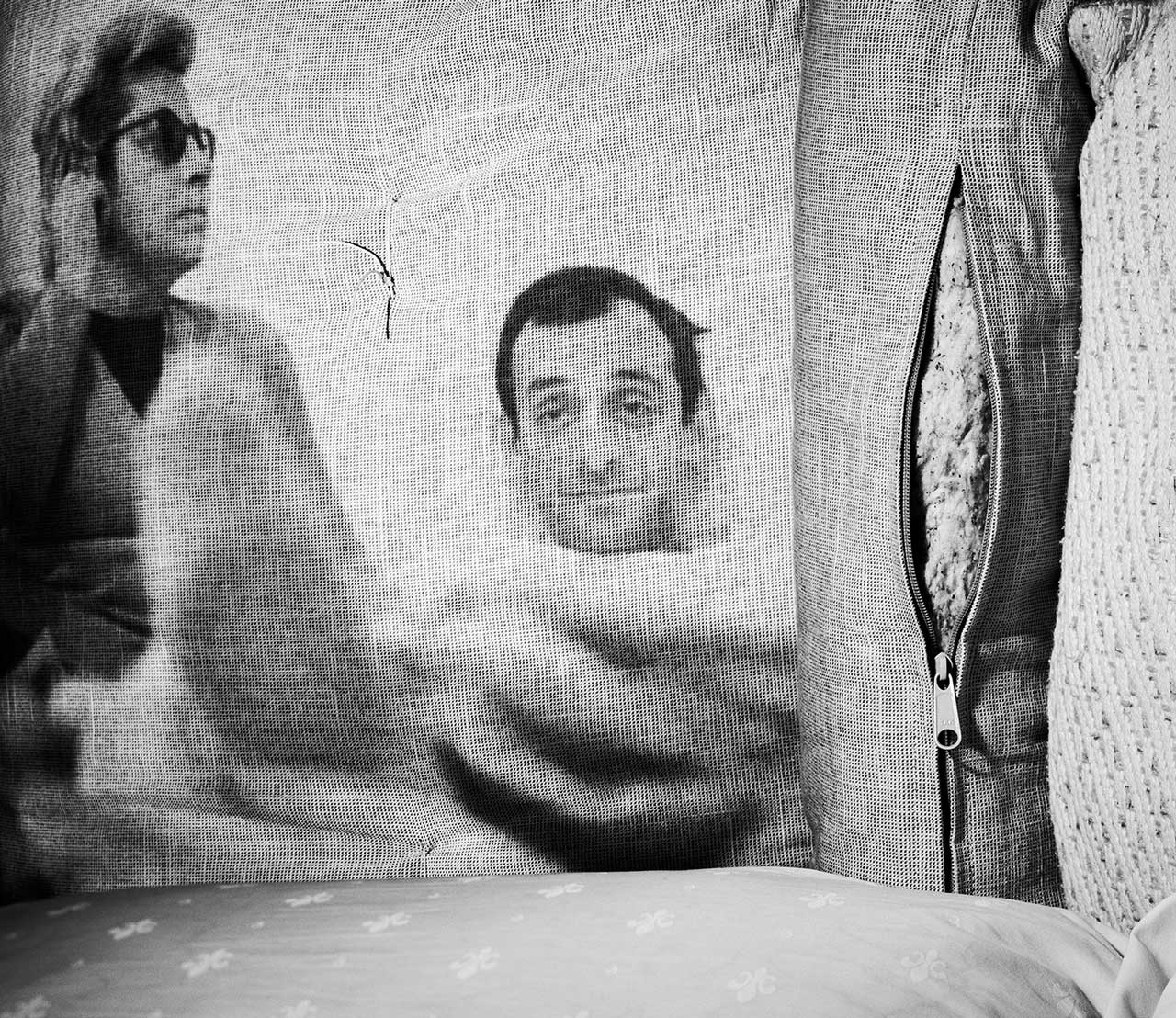

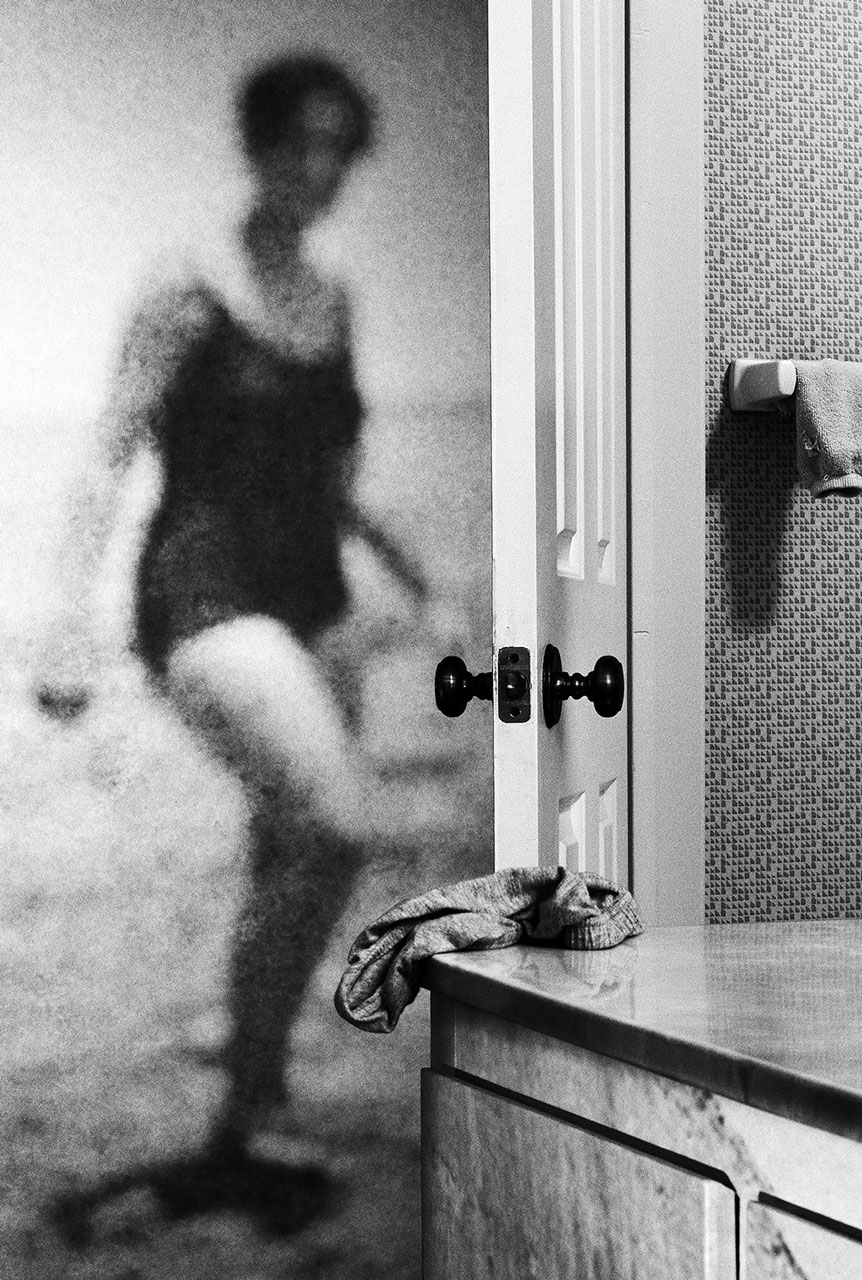

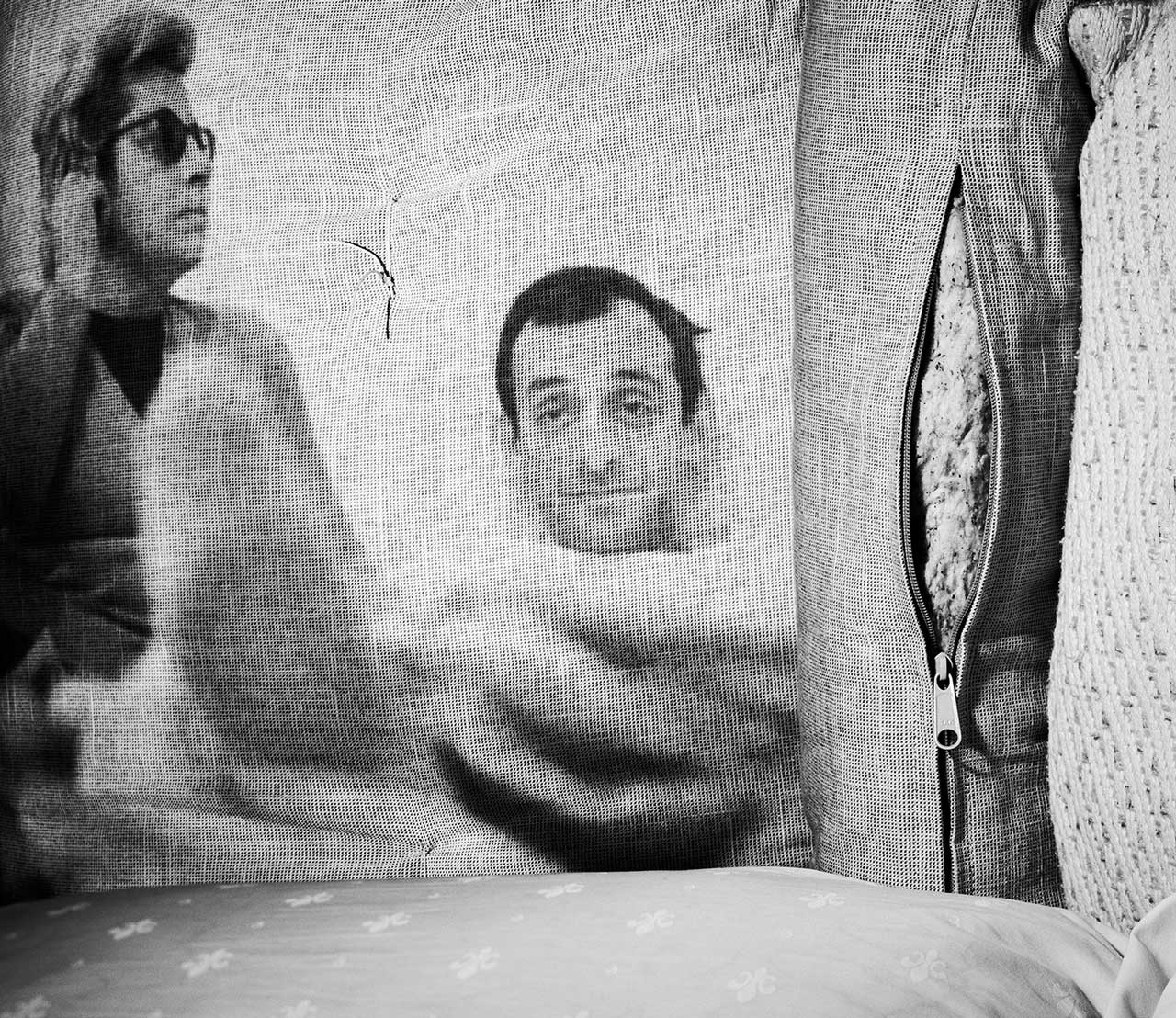

A girl and her room

A Girl and Her Room was inspired by my oldest daughter, then 15, who was no longer a carefree child. She was shifting into adulthood incrementally before my eyes. After photographing her with her girlfriends, I realized I wanted to capture each young woman by herself in her own environment: her bedroom. The room was a metaphor, an extension of the girl, but also the girl seemed to be part of the room, to fit in just like everything else in the material and emotional space she created.

While I initially focused on teenage girls in the United States, I eventually expanded the project to include girls from the other world I experienced myself as a young woman: the Middle East. This is how this project became personal to me. The beauty, dreams, vulnerability and strength of these young women, regardless of place, background and religion, were beautifully universal and deeply moving.

Being with those young women in the privacy of their world gave me a unique peek into their private lives and their inner selves. They sensed that I was not judging them and became an active part of the project. Their frankness and generosity in sharing access was a privilege that they have extended to me but also to all the viewers of this work.

Rania Matar (Lebanon, 1964). Originally trained as an architect at the American University of Beirut and at Cornell University, she studied photography at the New England School of Photography and the Maine Photographic Workshops. Her work focuses on girls and women. She documents her life through the lives of those around her, focusing on the personal and the mundane in an attempt to portray the universal within the personal. Her work has won several awards, is part of several museum and private collections, has been featured in numerous publications, and exhibited widely in the U.S. and internationally. Visit her website: raniamatar.com

Rania Matar (Lebanon, 1964). Originally trained as an architect at the American University of Beirut and at Cornell University, she studied photography at the New England School of Photography and the Maine Photographic Workshops. Her work focuses on girls and women. She documents her life through the lives of those around her, focusing on the personal and the mundane in an attempt to portray the universal within the personal. Her work has won several awards, is part of several museum and private collections, has been featured in numerous publications, and exhibited widely in the U.S. and internationally. Visit her website: raniamatar.com

A girl and her room

A Girl and Her Room was inspired by my oldest daughter, then 15, who was no longer a carefree child. She was shifting into adulthood incrementally before my eyes. After photographing her with her girlfriends, I realized I wanted to capture each young woman by herself in her own environment: her bedroom. The room was a metaphor, an extension of the girl, but also the girl seemed to be part of the room, to fit in just like everything else in the material and emotional space she created.

While I initially focused on teenage girls in the United States, I eventually expanded the project to include girls from the other world I experienced myself as a young woman: the Middle East. This is how this project became personal to me. The beauty, dreams, vulnerability and strength of these young women, regardless of place, background and religion, were beautifully universal and deeply moving.

Being with those young women in the privacy of their world gave me a unique peek into their private lives and their inner selves. They sensed that I was not judging them and became an active part of the project. Their frankness and generosity in sharing access was a privilege that they have extended to me but also to all the viewers of this work.

Rania Matar (Lebanon, 1964). Originally trained as an architect at the American University of Beirut and at Cornell University, she studied photography at the New England School of Photography and the Maine Photographic Workshops. Her work focuses on girls and women. She documents her life through the lives of those around her, focusing on the personal and the mundane in an attempt to portray the universal within the personal. Her work has won several awards, is part of several museum and private collections, has been featured in numerous publications, and exhibited widely in the U.S. and internationally. Visit her website: raniamatar.com

Rania Matar (Lebanon, 1964). Originally trained as an architect at the American University of Beirut and at Cornell University, she studied photography at the New England School of Photography and the Maine Photographic Workshops. Her work focuses on girls and women. She documents her life through the lives of those around her, focusing on the personal and the mundane in an attempt to portray the universal within the personal. Her work has won several awards, is part of several museum and private collections, has been featured in numerous publications, and exhibited widely in the U.S. and internationally. Visit her website: raniamatar.comNoah Kalina

Noah Kalina has been taking a photograph of himself every day since January 2000. Originally it was meant to be a photo project, but in 2006 he was inspired by a project by Ahree Lee, a graphic designer from California who had put a time-lapse video of herself on YouTube. Noah decided to do the same with his self-portraits and, within three weeks, it became an international internet sensation.

Noah Kalina (US, 1980) is a photographer based in Brooklyn and Lumberland, New York. He graduated from the School of Visual Arts with a BFA in photography. His project ‘Everyday’ was a worldwide hit. His work has been exhibited all over the world: in the U.S., Switzerland, Italy, Belgium, France, Australia, England, Canada, Germany and the Netherlands. He also has given lectures in various countries. To see more of his work go to: noahkalina.com