Marcus DeSieno

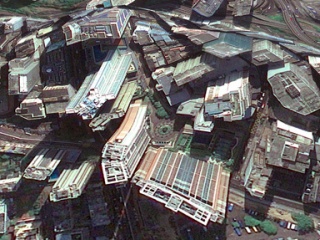

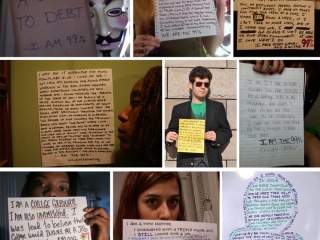

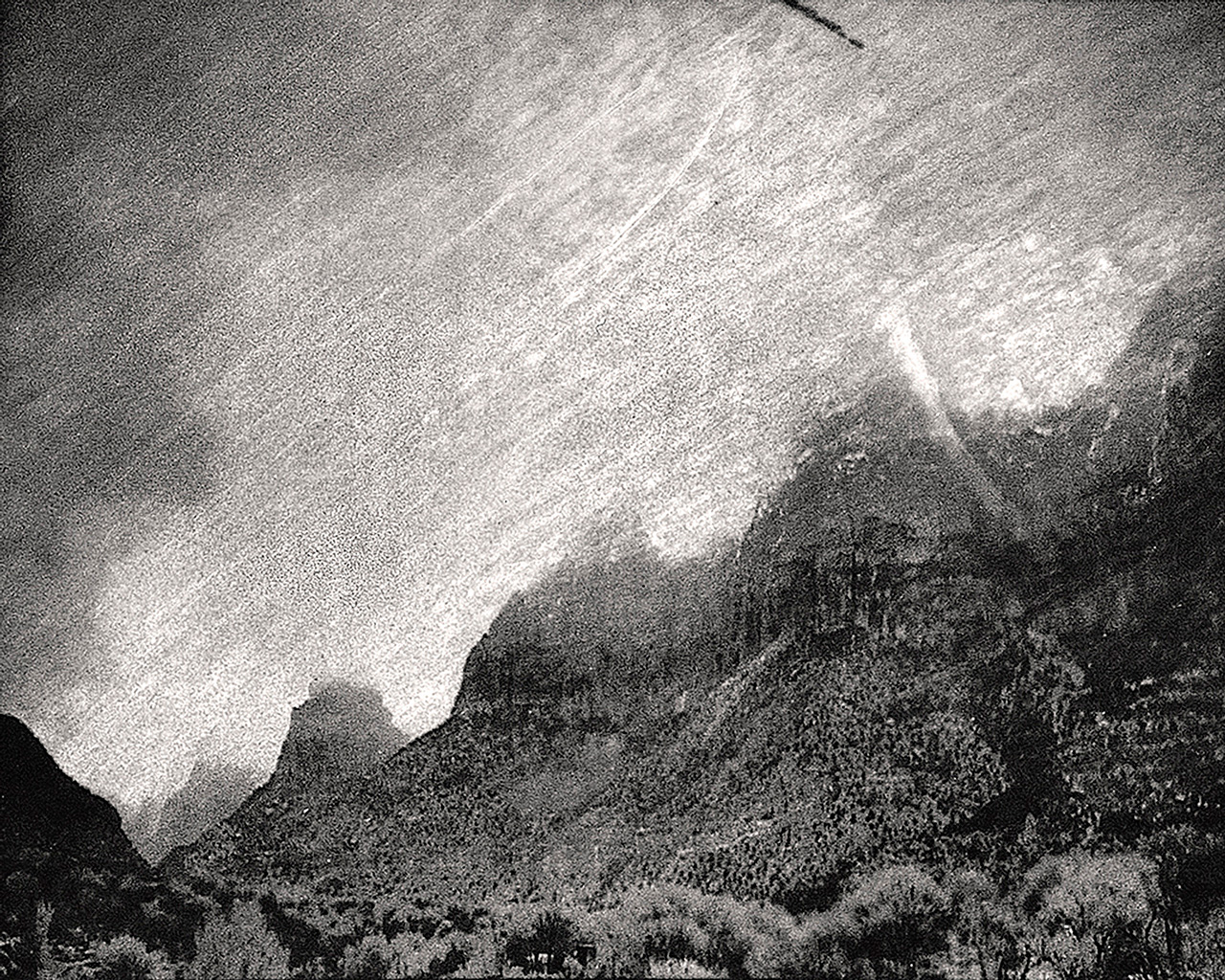

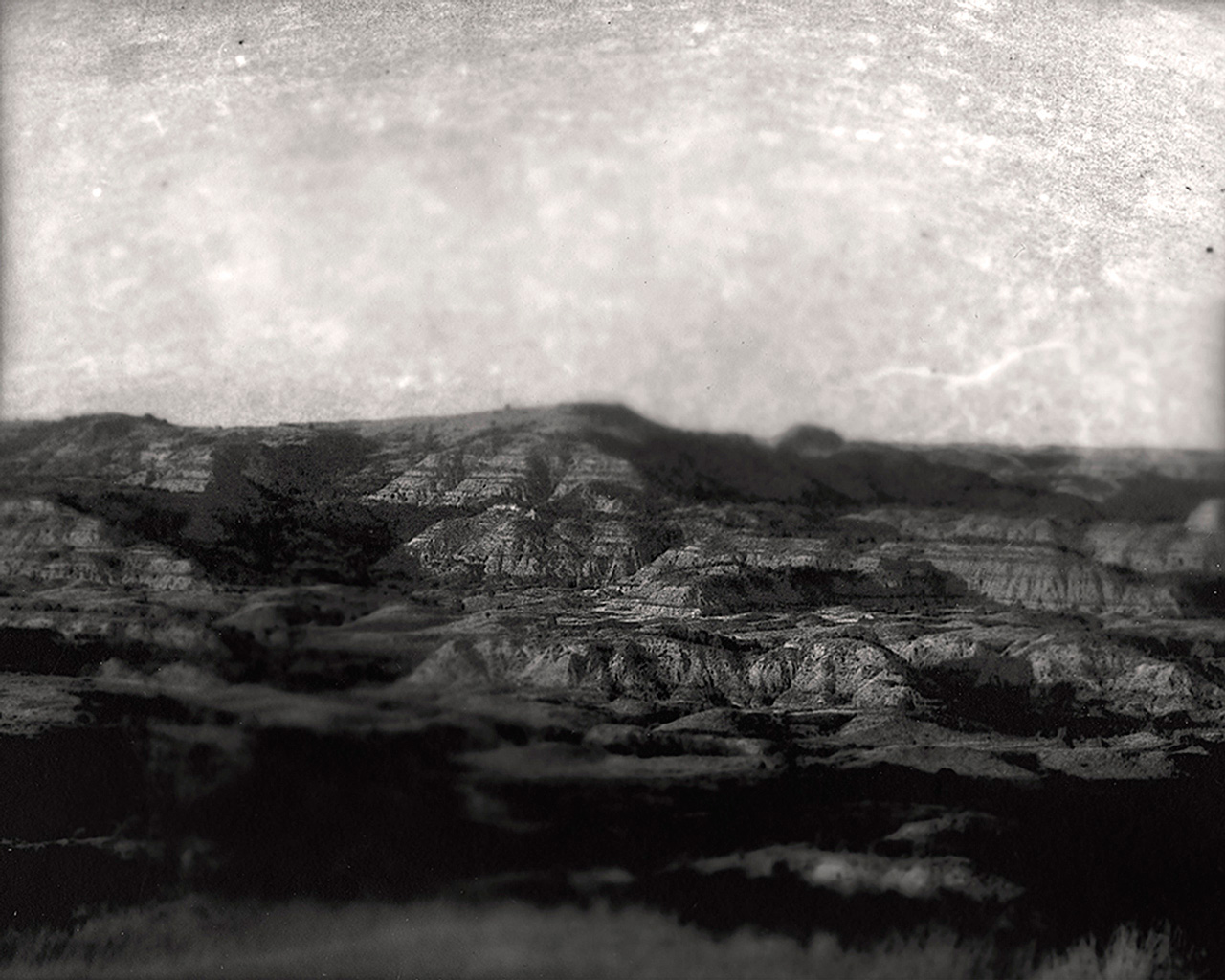

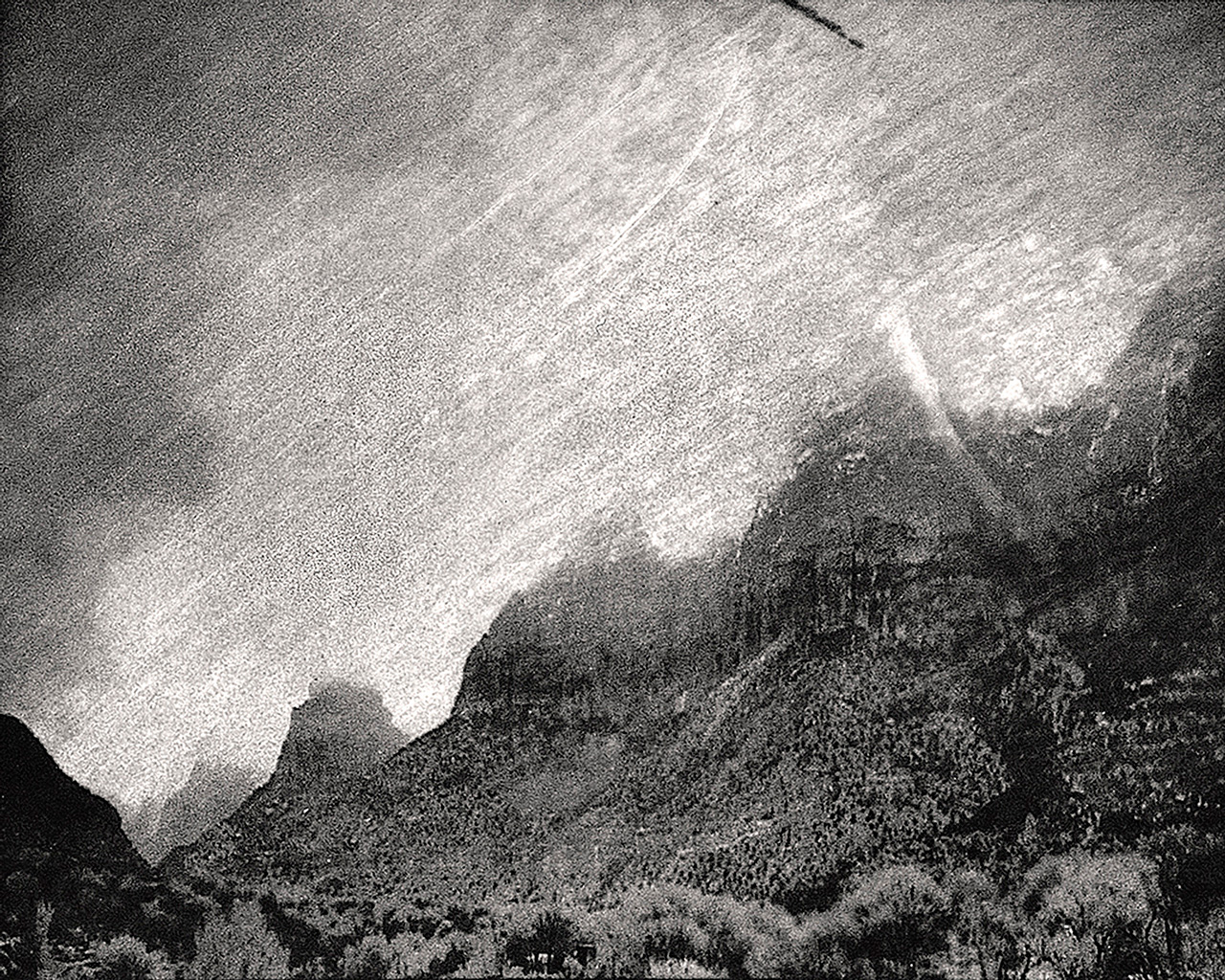

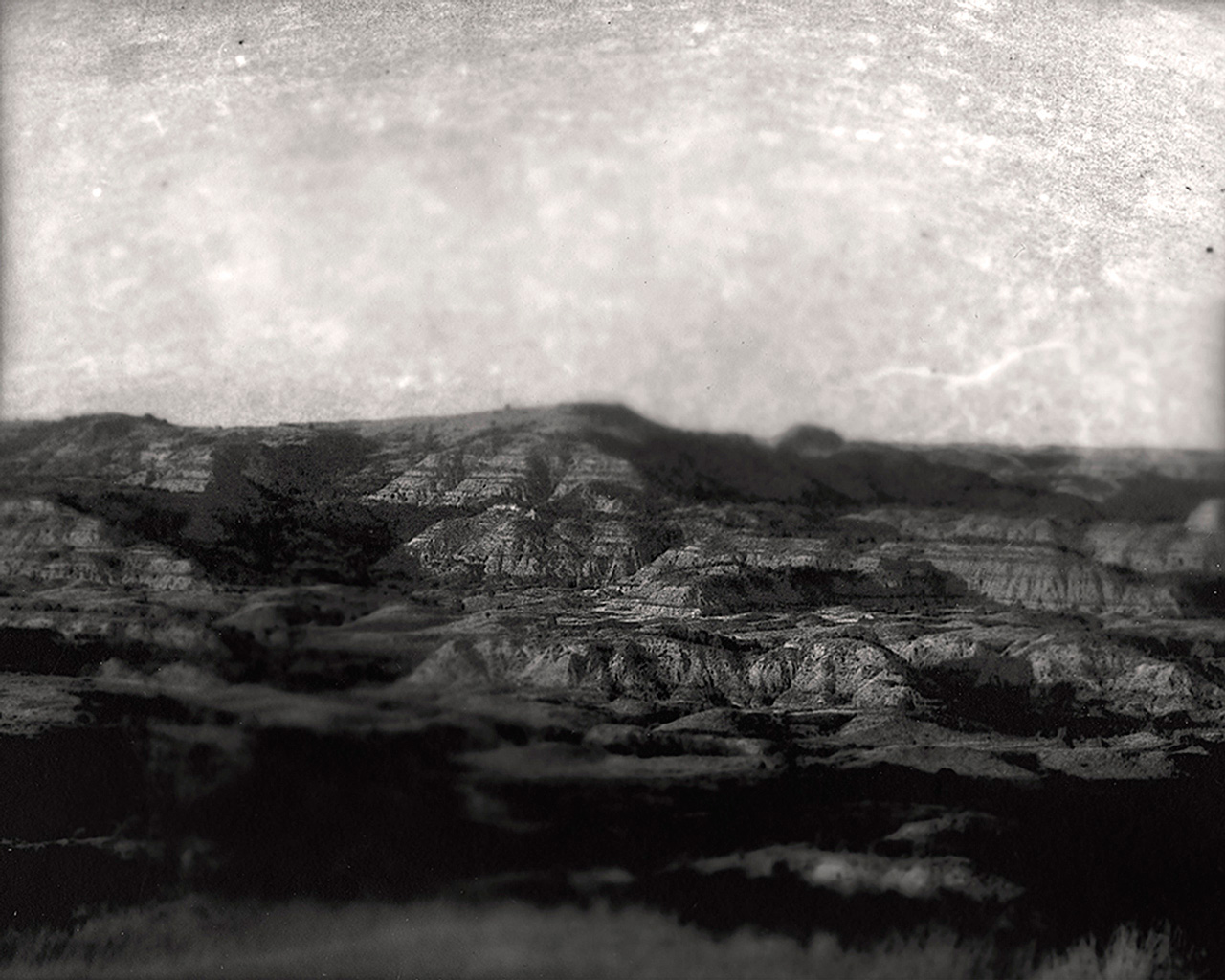

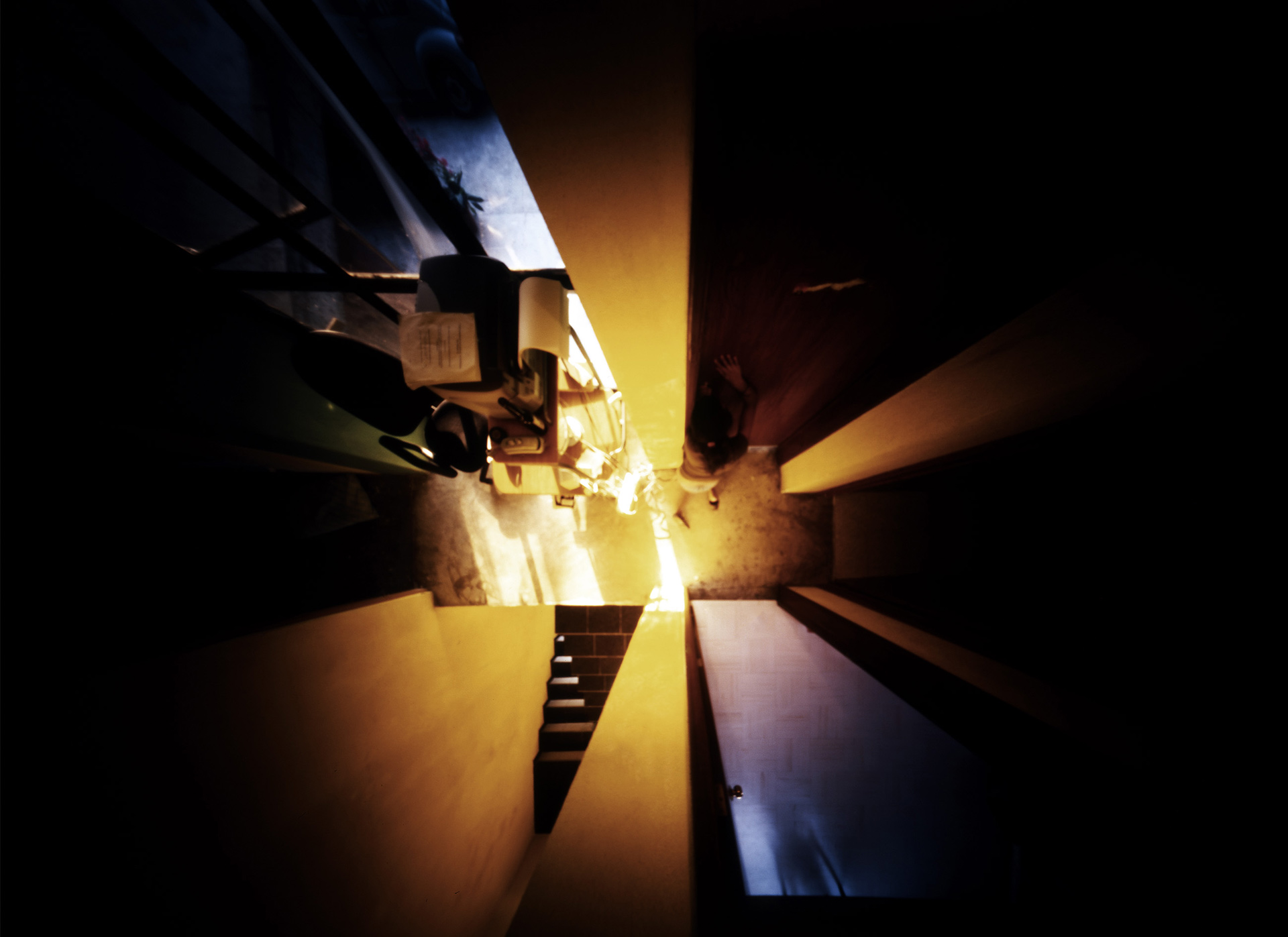

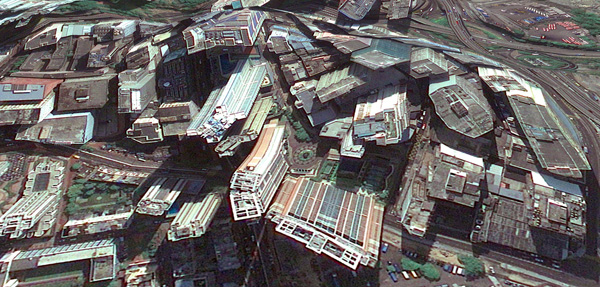

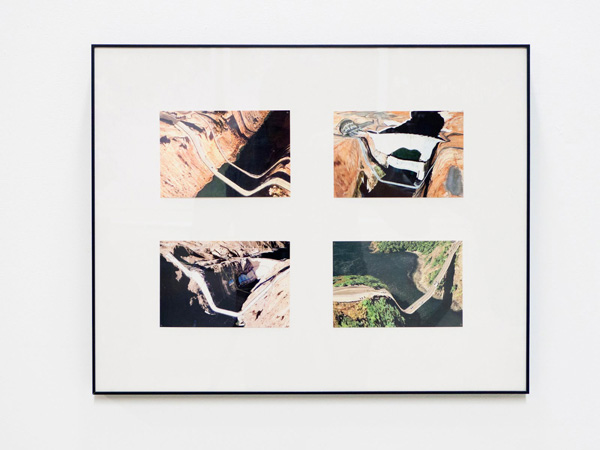

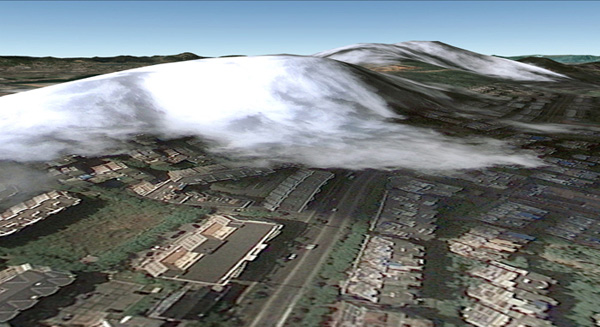

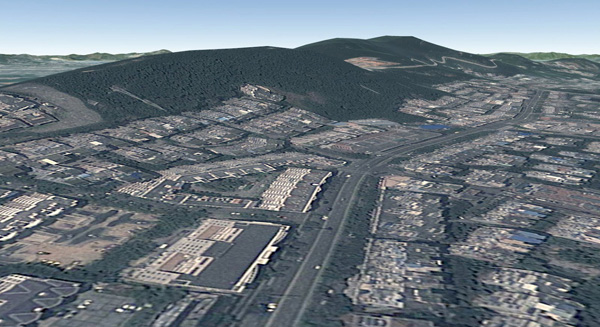

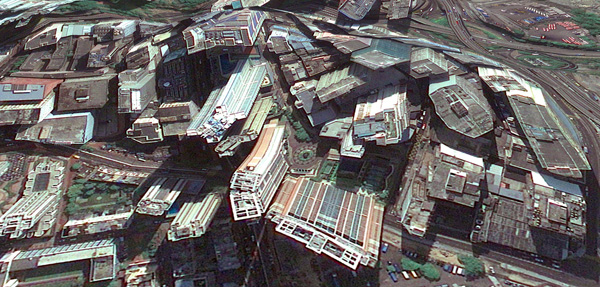

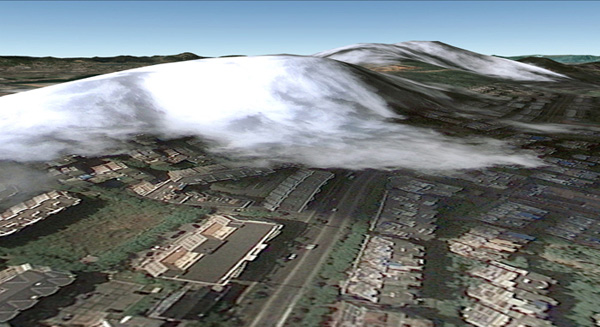

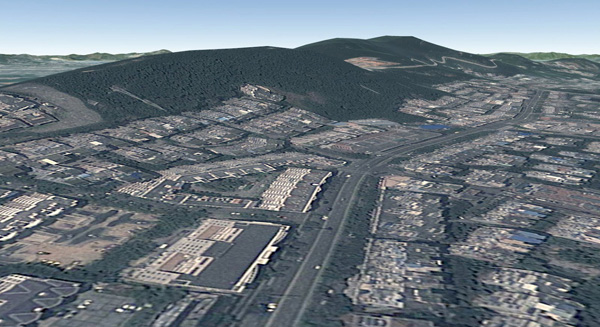

Surveillance Landscapes interrogates how surveillance technology has changed our relationship and understanding of landscape and place in our increasingly intrusive electronic culture. I hack into surveillance cameras, public webcams, and CCTV feeds in a pursuit for the classical picturesque landscape, dislocating the visual product from its automated origins while searching for a conversation between land, borders, and power. The very act of surveying a site through these photographic systems implies a dominating relationship between man and place. Ultimately, I hope to undermine these schemes of social control through the obfuscated melancholic images found while exploiting the technological mechanisms of power in our surveillance society.

Marcus DeSieno (USA). His work is concerned with science and exploration in relation to the history of photography. He received his MFA in Studio Art from the University of South Florida in 2015. DeSieno often assumes the role of the amateur scientist in his work in order to investigate photography's historic relationship with science in regards to the notion of the invisible. Antiquated and obsolescent photographic processes are often combined with contemporary imaging technologies to engage in a critical dialog on the evolution of photographic technology in relation to seeing.

Marcus DeSieno (USA). His work is concerned with science and exploration in relation to the history of photography. He received his MFA in Studio Art from the University of South Florida in 2015. DeSieno often assumes the role of the amateur scientist in his work in order to investigate photography's historic relationship with science in regards to the notion of the invisible. Antiquated and obsolescent photographic processes are often combined with contemporary imaging technologies to engage in a critical dialog on the evolution of photographic technology in relation to seeing.

Surveillance Landscapes interrogates how surveillance technology has changed our relationship and understanding of landscape and place in our increasingly intrusive electronic culture. I hack into surveillance cameras, public webcams, and CCTV feeds in a pursuit for the classical picturesque landscape, dislocating the visual product from its automated origins while searching for a conversation between land, borders, and power. The very act of surveying a site through these photographic systems implies a dominating relationship between man and place. Ultimately, I hope to undermine these schemes of social control through the obfuscated melancholic images found while exploiting the technological mechanisms of power in our surveillance society.

Marcus DeSieno (USA). His work is concerned with science and exploration in relation to the history of photography. He received his MFA in Studio Art from the University of South Florida in 2015. DeSieno often assumes the role of the amateur scientist in his work in order to investigate photography's historic relationship with science in regards to the notion of the invisible. Antiquated and obsolescent photographic processes are often combined with contemporary imaging technologies to engage in a critical dialog on the evolution of photographic technology in relation to seeing.

Marcus DeSieno (USA). His work is concerned with science and exploration in relation to the history of photography. He received his MFA in Studio Art from the University of South Florida in 2015. DeSieno often assumes the role of the amateur scientist in his work in order to investigate photography's historic relationship with science in regards to the notion of the invisible. Antiquated and obsolescent photographic processes are often combined with contemporary imaging technologies to engage in a critical dialog on the evolution of photographic technology in relation to seeing.Mauricio Alejo

In relation to his videos Mauricio shared the following reflexion with us, that was part of an interview he gave:

Recently I was interviewed by Katrin Steffen. She asked me what I thought of the idea of my videos being surreal. The question caught me off guard; not that I was completely unaware of this, let’s say, approach to my work - other people have made the same observation - but it was the direct, straightforward way in which she formulated her question that struck me.

It is interesting that, until then, I had been resisting calling my work surreal. I don’t know why. I just unreflectively didn't like the idea, but once the question was out I had no option but to come to terms with what I was so stubbornly denying.

Answering it was both liberating and enlightening. I came to understand that, indeed, there is a strong surreal element to my work, probably “á la Magritte” as in “This is not a Pipe” (as opposed to “á la Dalí”, whose work I dislike; it is too spectacular for my taste).

Either way, what I can say is that I’m not trying to open a door to the unconscious, but to a more obvious and factual world that is still surprising, because it actually exists and is just hidden in plain sight.

These lines show a desire to offer a new way of looking at a universe that is hidden behind the false transparency of the photographic language.

In several of the works presented here, our reading of a still image is transformed—thanks to the passage of time—into something completely different. The surprising elements in the universe are infinitely more casual. Gravity, in an unforeseen twist, belies the lightness of the air.

In all of them, the passage of time is a necessary element to show that photography can be a map of the reality but is not equal to it, like for example in the piece World: the world that not stops to move is different from the world that not stops to move around it, and in turn different from our world that also does not slow down.

| Universe |

Line |

Hole |

| Gravity |

Twig |

Crack |

| Container |

Fact and fiction |

World |

Mauricio Alejo (Mexico, 1969). He earned his Master of Art from New York University in 2002, as a Fulbright Grant recipient. In 2007, he was a resident artist at NUS Centre for the Arts in Singapore. He has received multiple awards and grants, including the New York Foundation for the Arts grant in 2008. His work is part of important collections such as Daros Latinoamérica Collection in Zürich . His work has been reviewed in important journals, such as Flash Art; Art News and Art in America. He has had solo exhibitions in New York, Japan, Madrid, Paris and Mexico. His work has been shown at CCA Wattis Institute of Contemporary Arts in San Francisco; Museo Centro de Arte Reina Sofía in Madrid and The 8th Havana Biennial among other venues. He currently lives and works in New York City.

Mauricio Alejo (Mexico, 1969). He earned his Master of Art from New York University in 2002, as a Fulbright Grant recipient. In 2007, he was a resident artist at NUS Centre for the Arts in Singapore. He has received multiple awards and grants, including the New York Foundation for the Arts grant in 2008. His work is part of important collections such as Daros Latinoamérica Collection in Zürich . His work has been reviewed in important journals, such as Flash Art; Art News and Art in America. He has had solo exhibitions in New York, Japan, Madrid, Paris and Mexico. His work has been shown at CCA Wattis Institute of Contemporary Arts in San Francisco; Museo Centro de Arte Reina Sofía in Madrid and The 8th Havana Biennial among other venues. He currently lives and works in New York City.In relation to his videos Mauricio shared the following reflexion with us, that was part of an interview he gave:

Recently I was interviewed by Katrin Steffen. She asked me what I thought of the idea of my videos being surreal. The question caught me off guard; not that I was completely unaware of this, let’s say, approach to my work - other people have made the same observation - but it was the direct, straightforward way in which she formulated her question that struck me.

It is interesting that, until then, I had been resisting calling my work surreal. I don’t know why. I just unreflectively didn't like the idea, but once the question was out I had no option but to come to terms with what I was so stubbornly denying.

Answering it was both liberating and enlightening. I came to understand that, indeed, there is a strong surreal element to my work, probably “á la Magritte” as in “This is not a Pipe” (as opposed to “á la Dalí”, whose work I dislike; it is too spectacular for my taste).

Either way, what I can say is that I’m not trying to open a door to the unconscious, but to a more obvious and factual world that is still surprising, because it actually exists and is just hidden in plain sight.

These lines show a desire to offer a new way of looking at a universe that is hidden behind the false transparency of the photographic language.

In several of the works presented here, our reading of a still image is transformed—thanks to the passage of time—into something completely different. The surprising elements in the universe are infinitely more casual. Gravity, in an unforeseen twist, belies the lightness of the air.

In all of them, the passage of time is a necessary element to show that photography can be a map of the reality but is not equal to it, like for example in the piece World: the world that not stops to move is different from the world that not stops to move around it, and in turn different from our world that also does not slow down.

| Universe |

Line |

Hole |

| Gravity |

Twig |

Crack |

| Container |

Fact and fiction |

World |

Mauricio Alejo (Mexico, 1969). He earned his Master of Art from New York University in 2002, as a Fulbright Grant recipient. In 2007, he was a resident artist at NUS Centre for the Arts in Singapore. He has received multiple awards and grants, including the New York Foundation for the Arts grant in 2008. His work is part of important collections such as Daros Latinoamérica Collection in Zürich . His work has been reviewed in important journals, such as Flash Art; Art News and Art in America. He has had solo exhibitions in New York, Japan, Madrid, Paris and Mexico. His work has been shown at CCA Wattis Institute of Contemporary Arts in San Francisco; Museo Centro de Arte Reina Sofía in Madrid and The 8th Havana Biennial among other venues. He currently lives and works in New York City.

Mauricio Alejo (Mexico, 1969). He earned his Master of Art from New York University in 2002, as a Fulbright Grant recipient. In 2007, he was a resident artist at NUS Centre for the Arts in Singapore. He has received multiple awards and grants, including the New York Foundation for the Arts grant in 2008. His work is part of important collections such as Daros Latinoamérica Collection in Zürich . His work has been reviewed in important journals, such as Flash Art; Art News and Art in America. He has had solo exhibitions in New York, Japan, Madrid, Paris and Mexico. His work has been shown at CCA Wattis Institute of Contemporary Arts in San Francisco; Museo Centro de Arte Reina Sofía in Madrid and The 8th Havana Biennial among other venues. He currently lives and works in New York City.Gabriel de la Mora

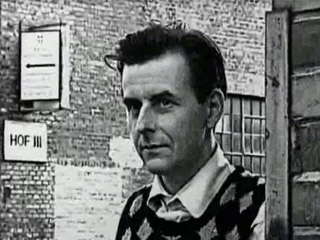

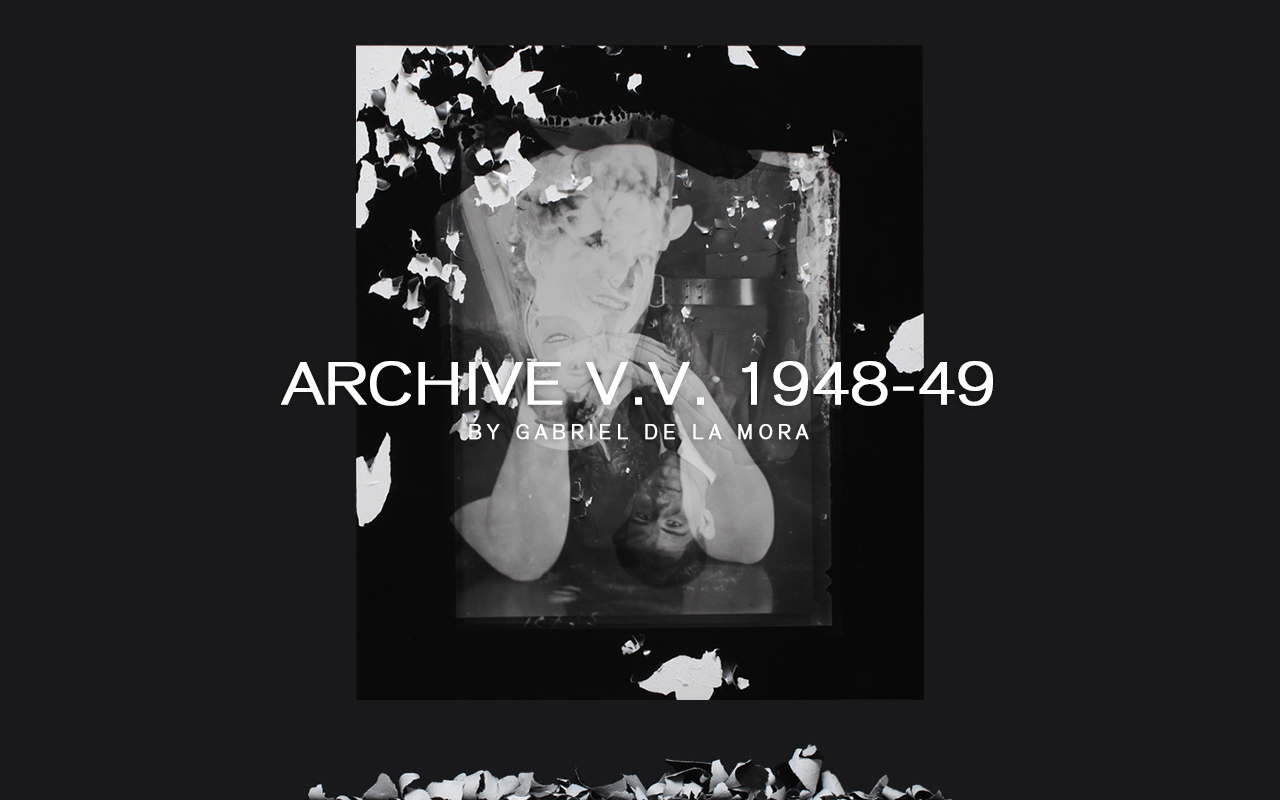

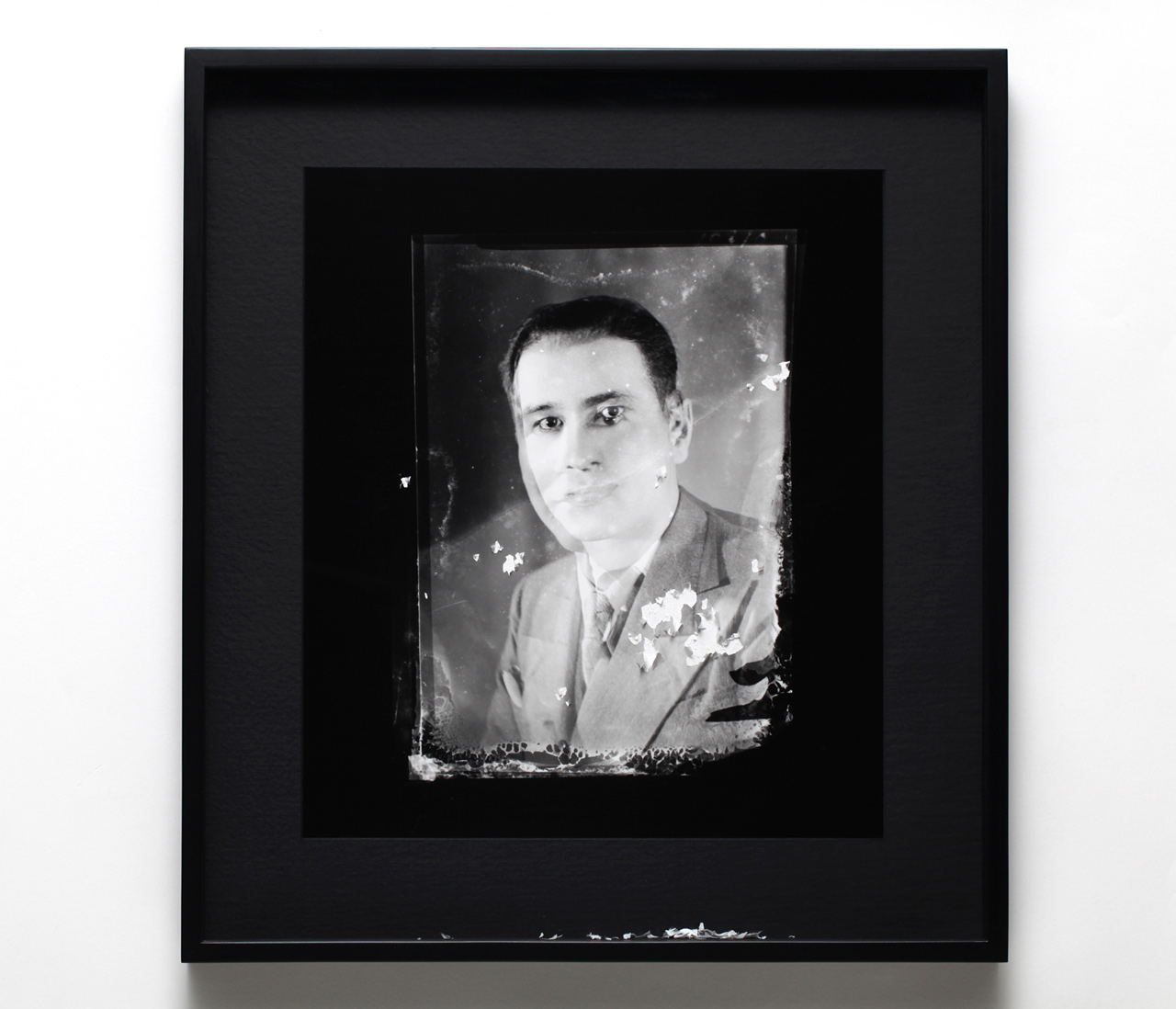

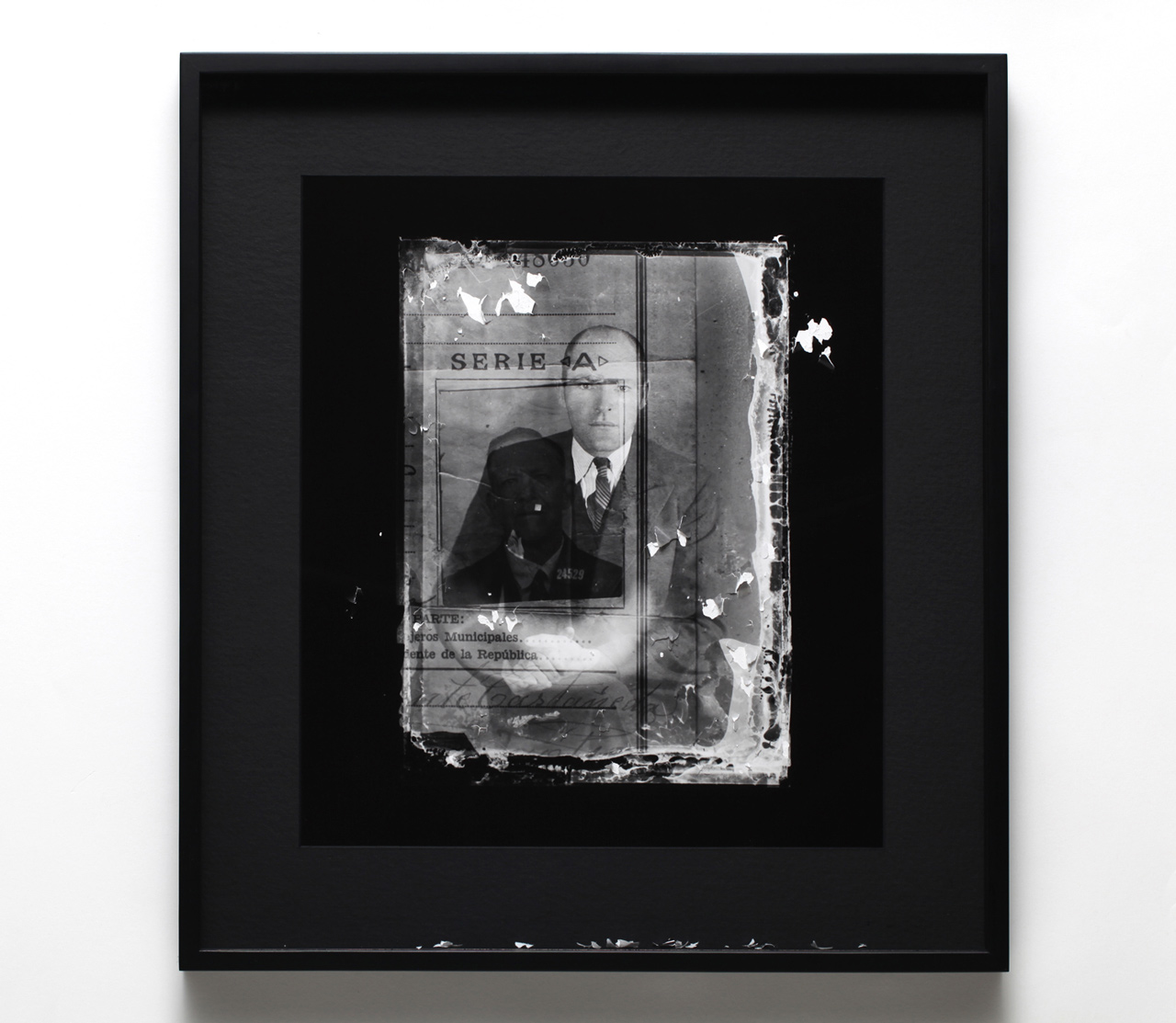

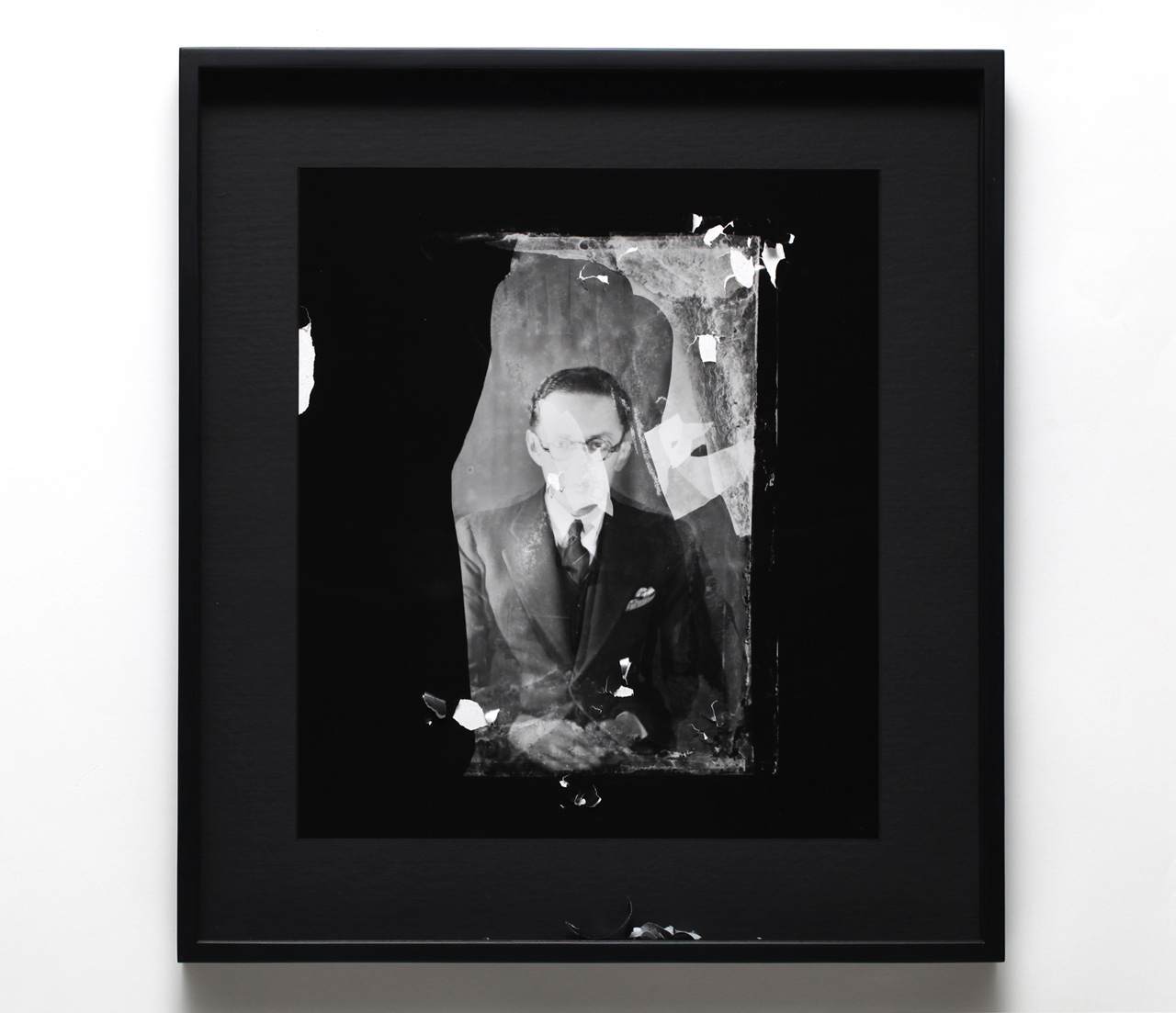

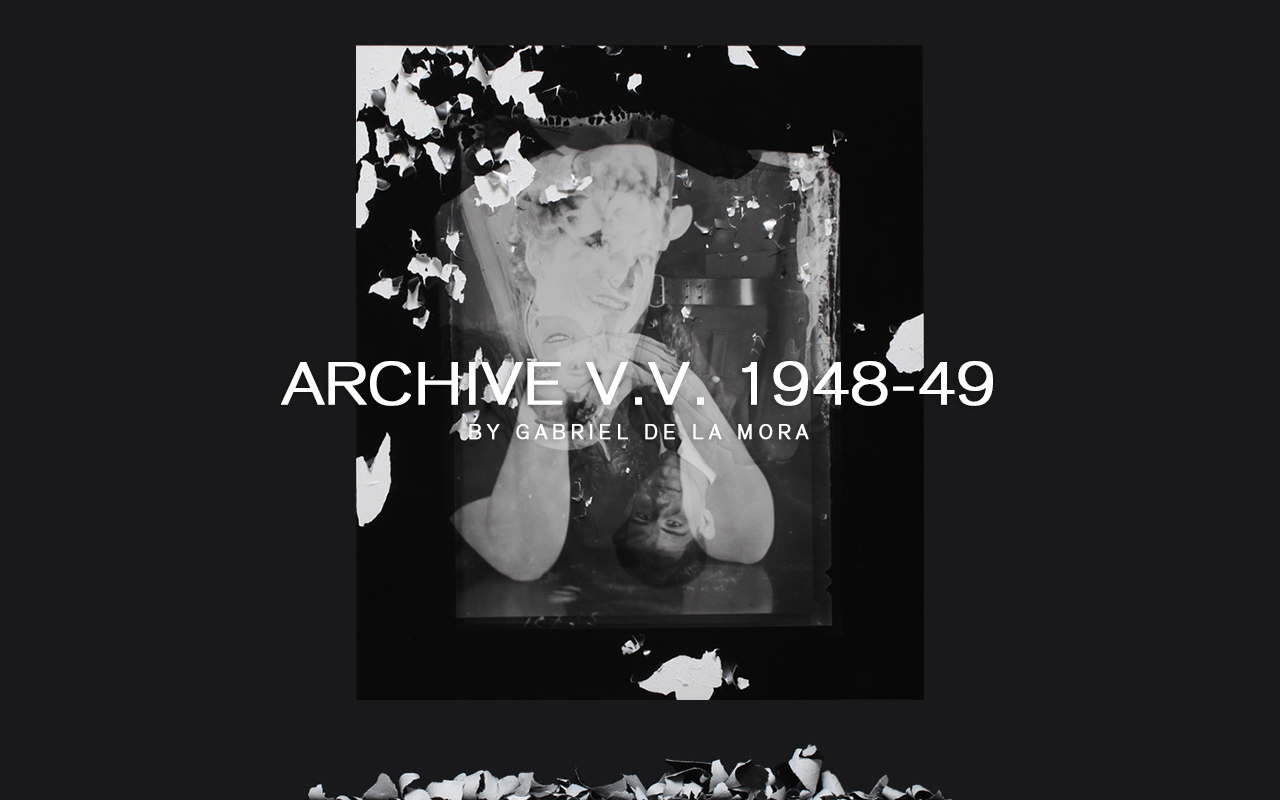

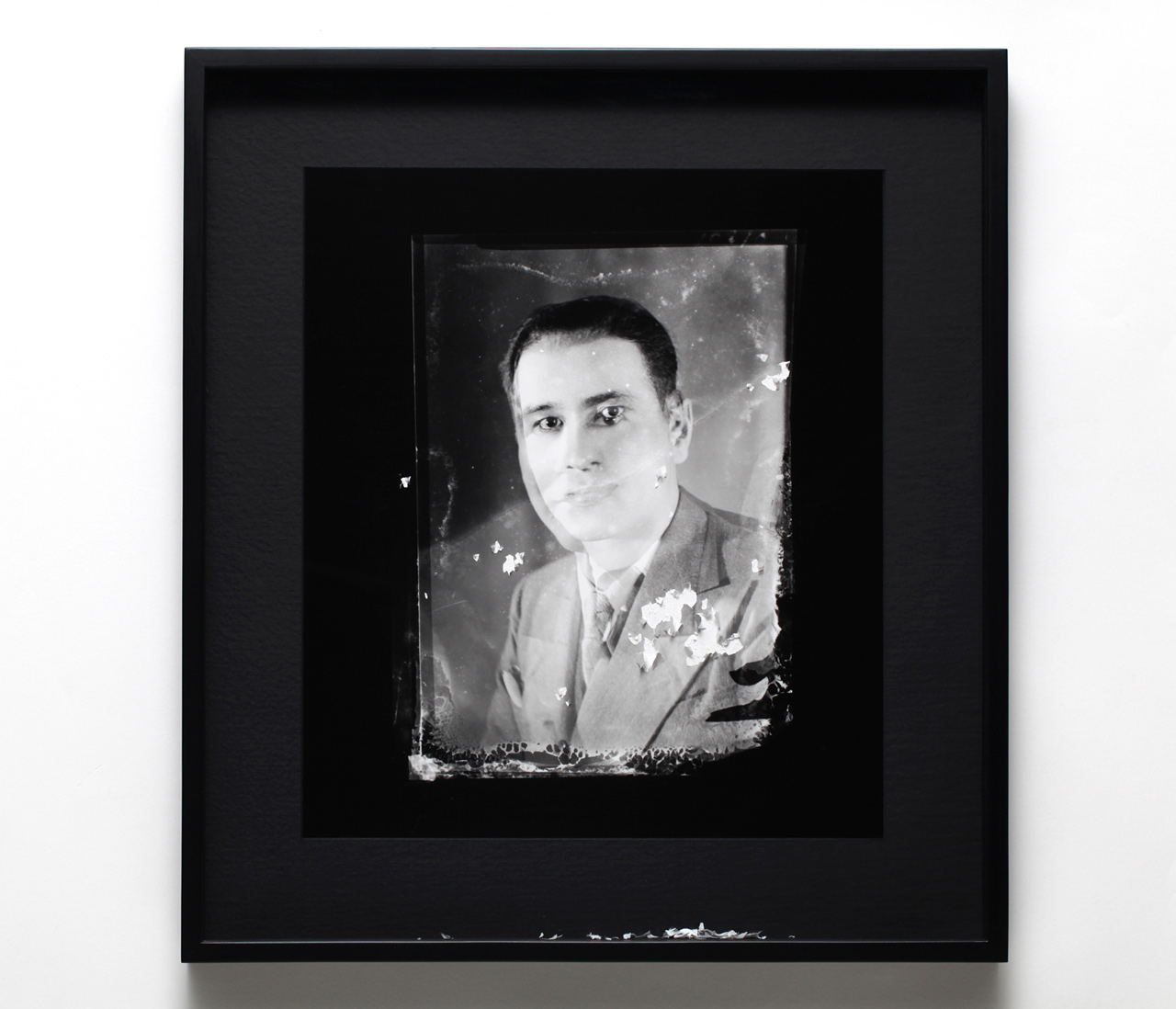

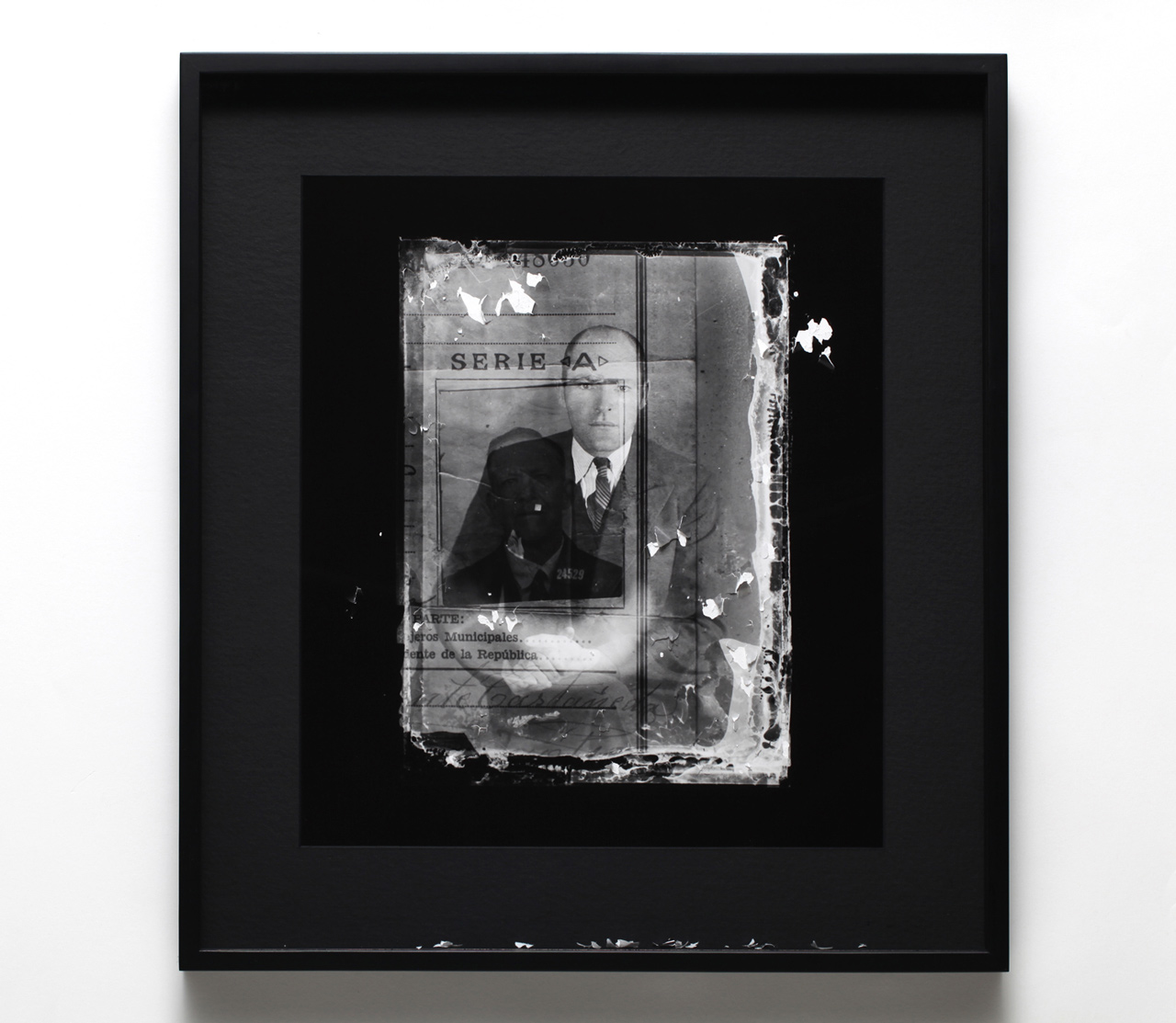

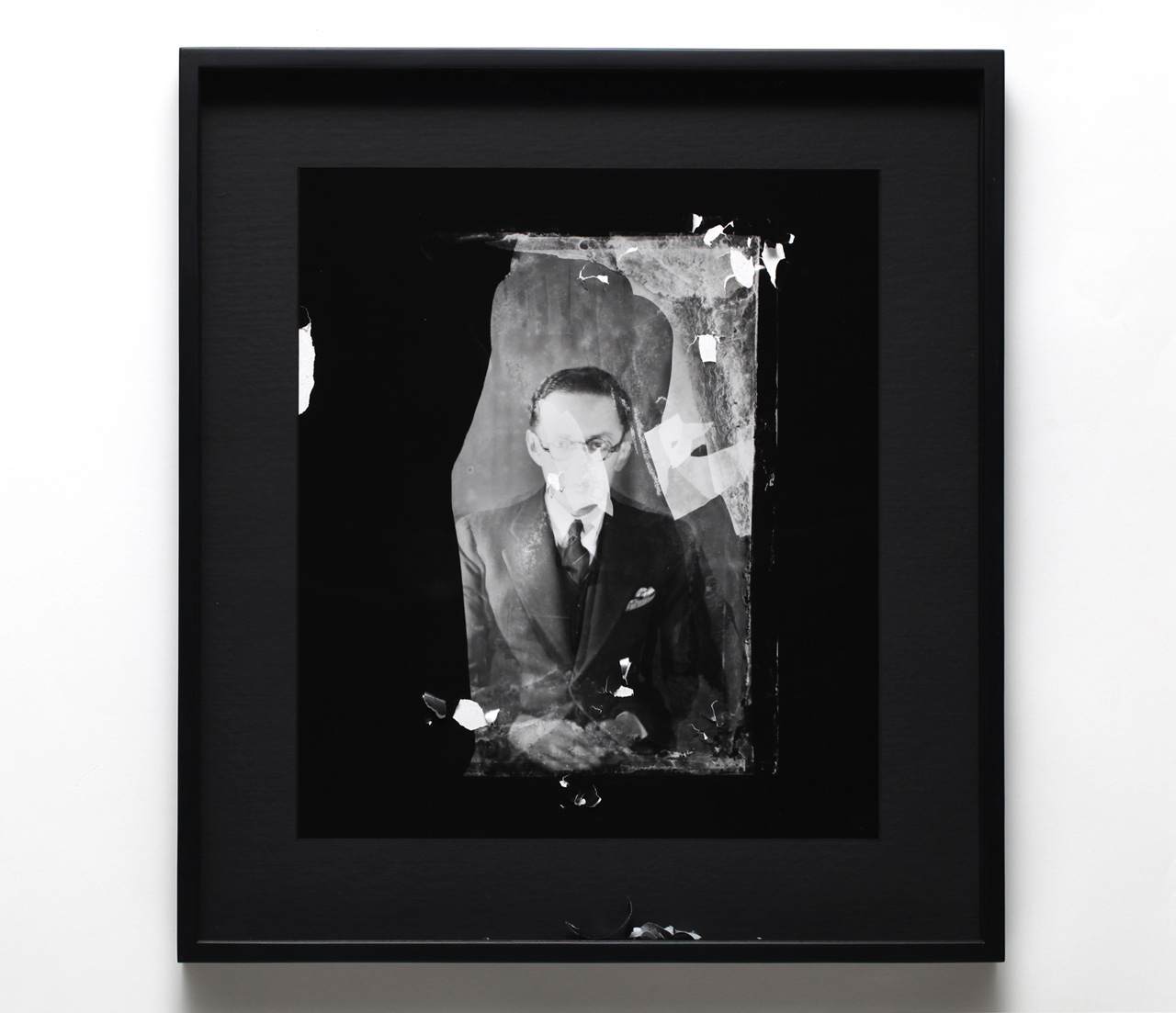

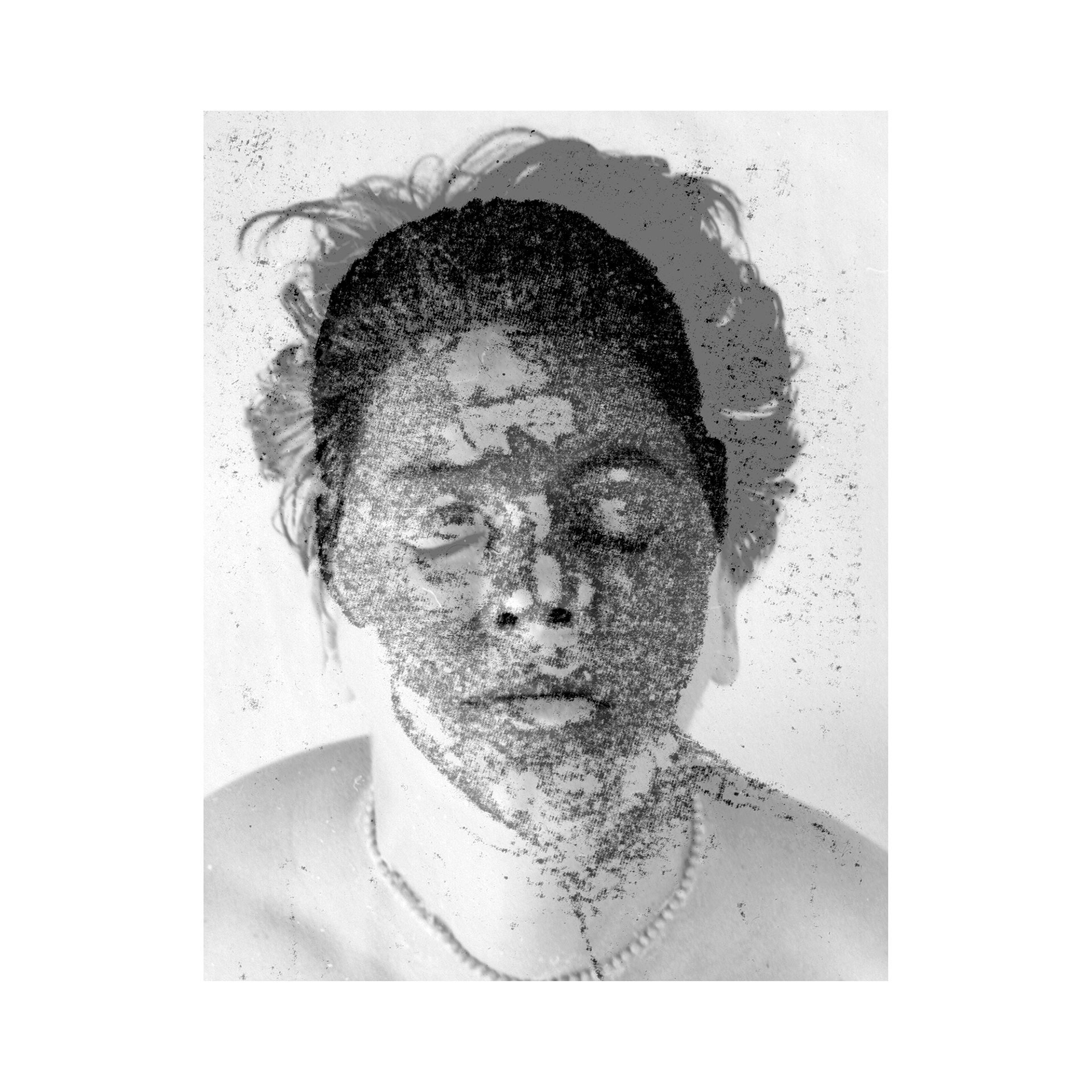

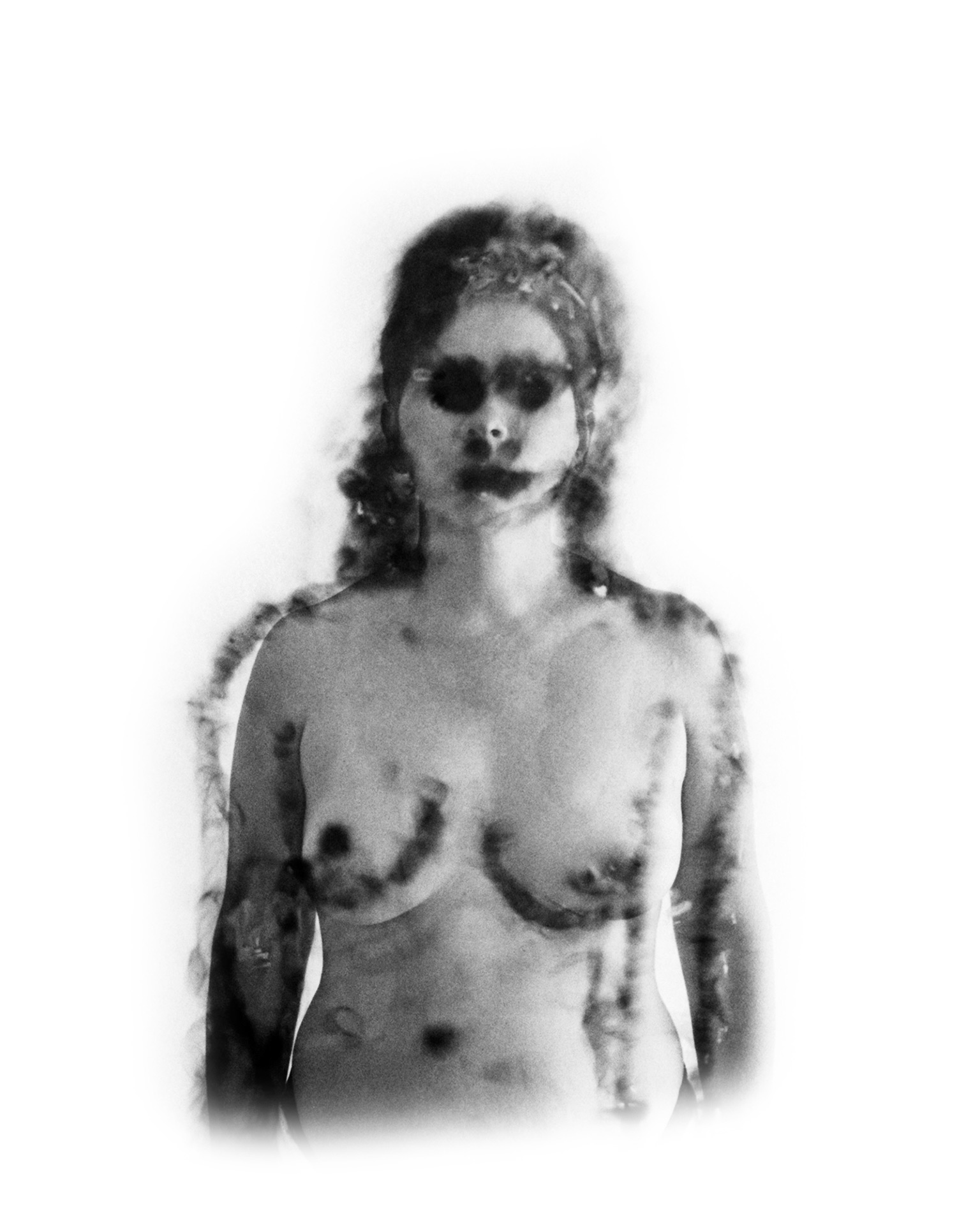

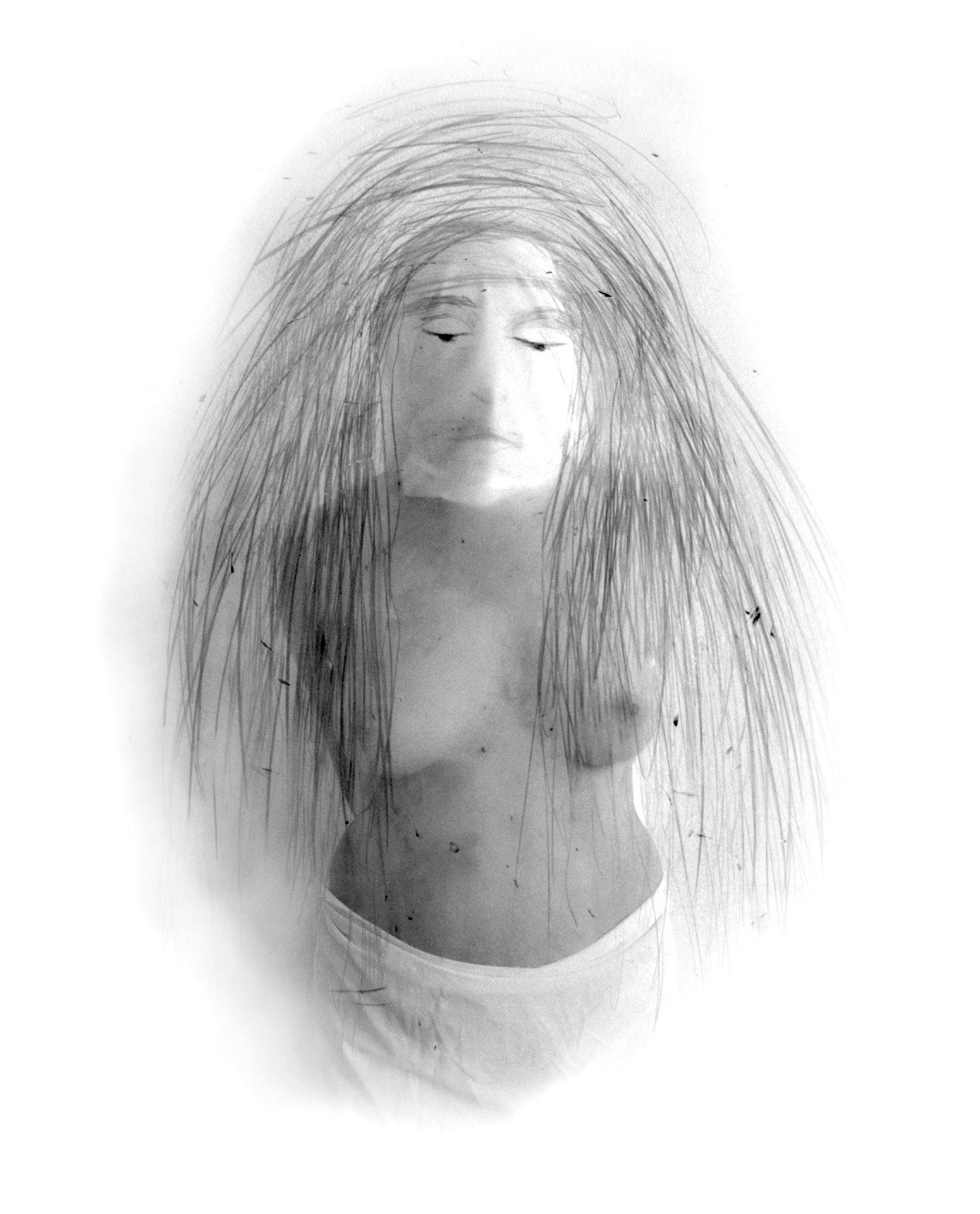

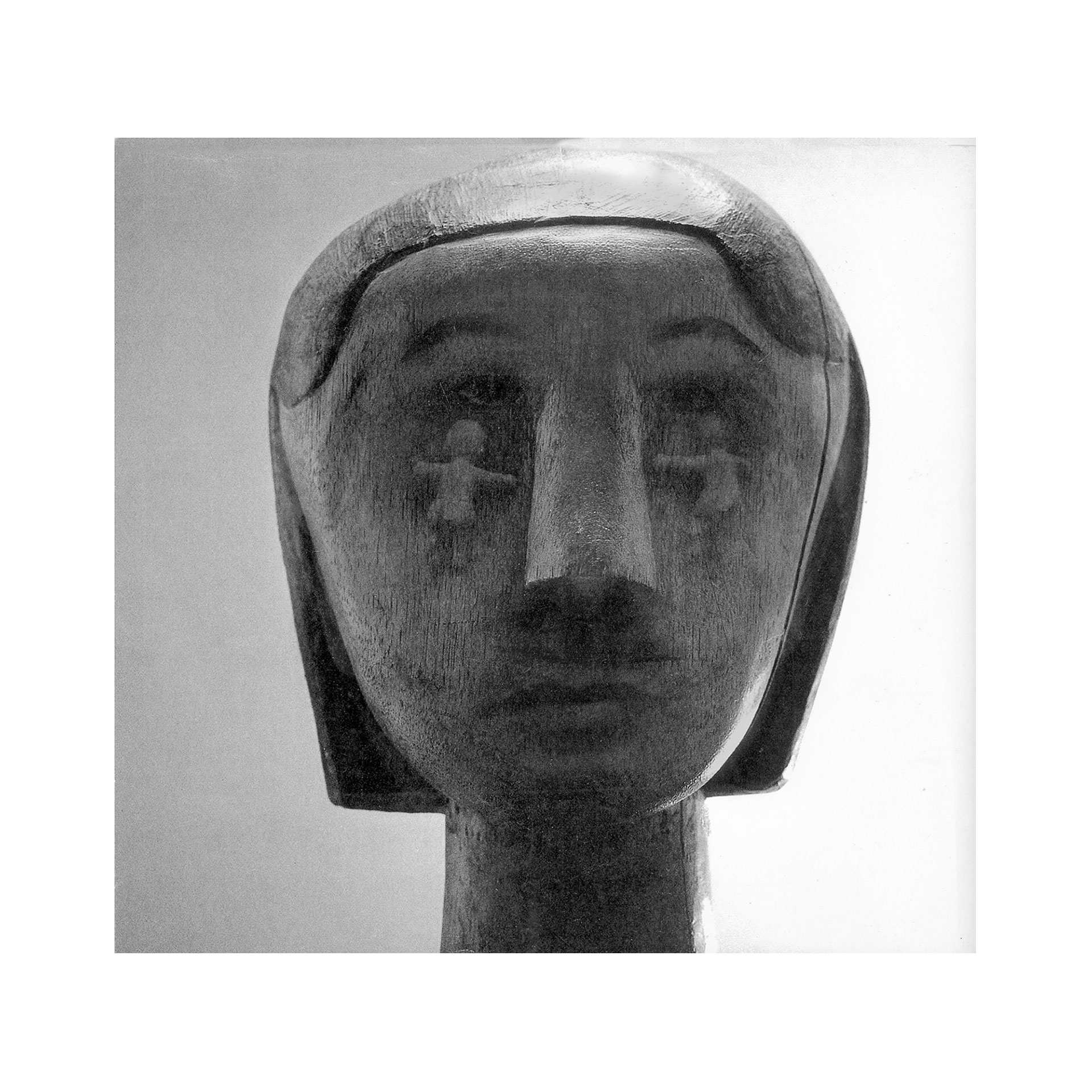

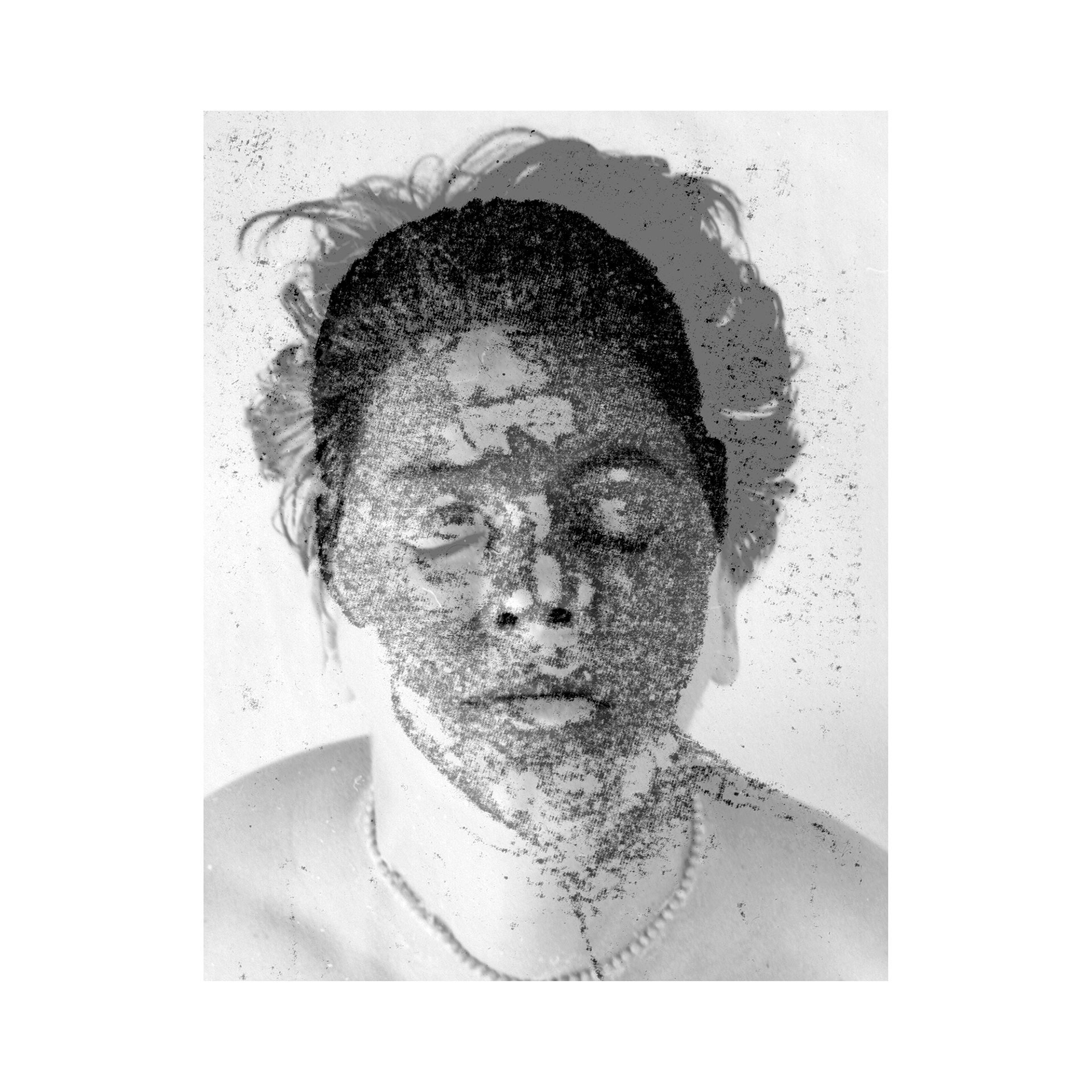

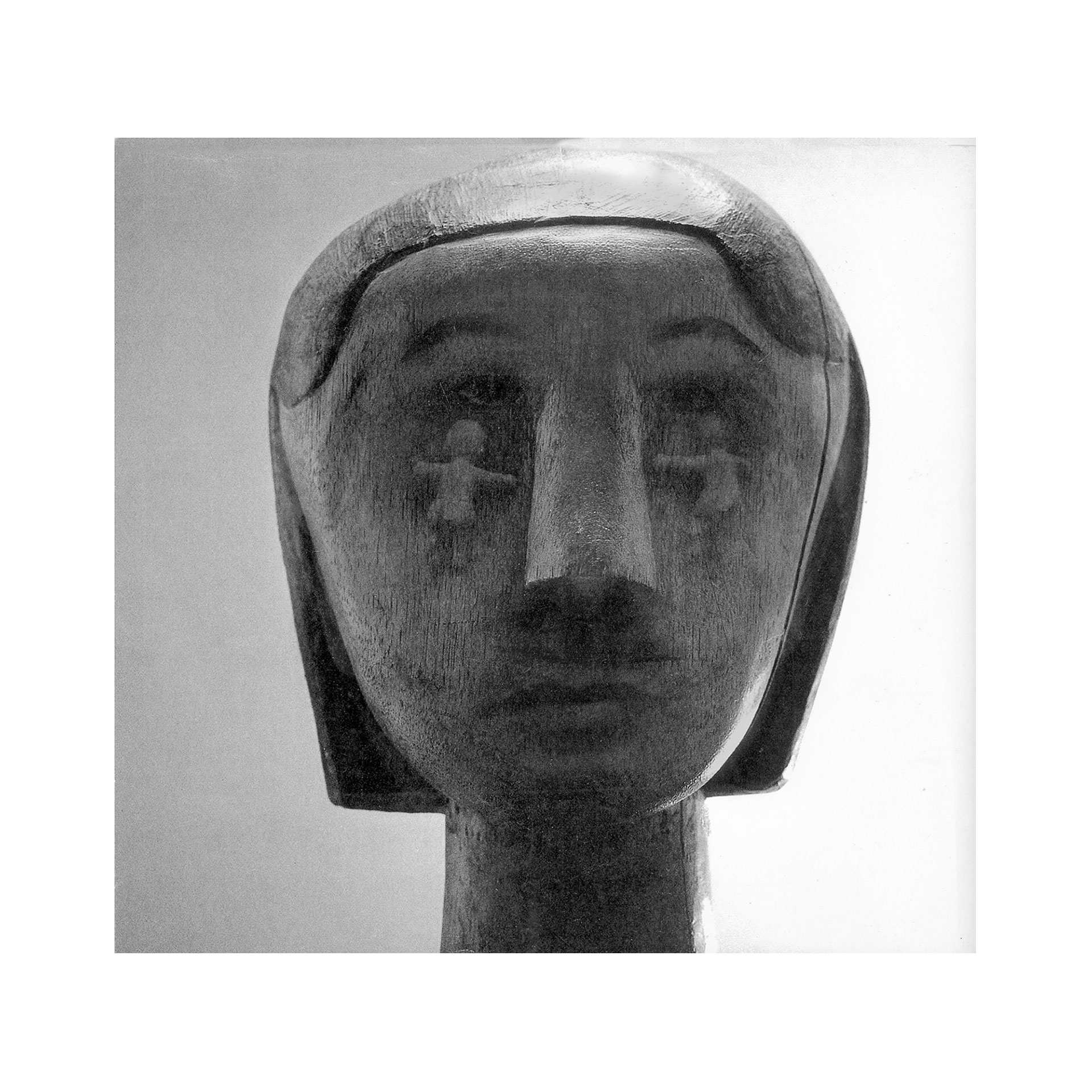

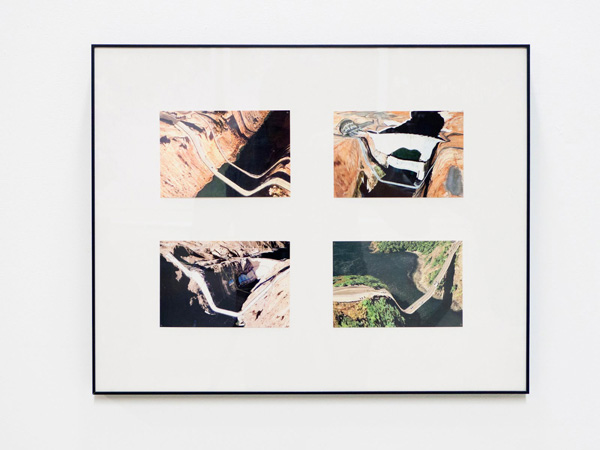

This series of altered photographs comes from a set of negatives that was destroyed when the warehouse where they had been stored for decades was flooded. This is why some of the negatives were stuck together, some of them showing two different takes of the same person and others two or three different people. They are negatives of portraits taken in 1948 and 1949 by Víctor Villamil Vilón at Cano Photography Studios, later called Vilón Photography Studios in Bogotá, Colombia. The images were printed on silver gel with fibrous paper in Mexico City and subsequently altered and framed. The artist begins his work by tearing off pieces of the photo.

Time and light do the rest, erasing the photographic image completely and leaving a monochrome surface. Only then is the work finished. Therefore 50, 100 or 300 years will have to pass, depending on the conditions in which the work is found. The artist never completes the piece and will surely never see it finished. This series is a parallel to the altered space entitled Pan-American Exhibition at NC ARTE.

Gabriel de la Mora (Mexico 1968). Studied a masters in painting, photography and video at the Pratt Institute in New York (2001-2003) and a bachelors in architecture at the Universidad Anáhuac del Norte (1987-1991) in Mexico City. He is currently a member of the Sistema Nacional de Creadores de Arte (2013-2015) and has received a number of awards and grants including the Primer Premio de la VII Bienal de Monterrey FEMSA, the Garcia Robles Fulbright Grant and the Jacques and Natasha Gelman Grant among others. His work as been shown in Mexico and abroad both individually and collectively.

Gabriel de la Mora (Mexico 1968). Studied a masters in painting, photography and video at the Pratt Institute in New York (2001-2003) and a bachelors in architecture at the Universidad Anáhuac del Norte (1987-1991) in Mexico City. He is currently a member of the Sistema Nacional de Creadores de Arte (2013-2015) and has received a number of awards and grants including the Primer Premio de la VII Bienal de Monterrey FEMSA, the Garcia Robles Fulbright Grant and the Jacques and Natasha Gelman Grant among others. His work as been shown in Mexico and abroad both individually and collectively.ZZ. In the project called Archive V.V. 1948 -49 how do you establish the photograph/time relationship? How does it affect the image both as an external and intrinsic element?

GM. Photographic technique is a constantly changing process. Depending upon the passage of time and light, on how the photo has been exposed to these two factors, it can slowly fade and begin to disappear. Which initially worried me for this project. But I think that later this inevitable factor became a starting point for various series in which I used photography as primary or supporting material.

In most of my work, photography is an important element, whether as a file or a document, or a starting point as it was for Willy Kautz in his work shown at the Amparo Museum from October 2014 to February 2015 under the title "What watches us that we don’t see.” The starting point in this exhibit was how an image becomes monochromatic and how a monochrome can become an image.

Although I take photographs to document pieces and processes, amongst many other things, I like to work with vintage photographs from the late 19th to the late 20th century. I buy archives, classify them and then begin my explorations. For the Archive V.V. 1948-49 project I used destroyed negatives for the first time. The alterations were both accidental and due to the passage of time, which produced astounding results.

The Vilón Archive series began in 2012 while I was preparing for my first altered space project at the NC ARTE gallery in Bogotá Colombia. As an alternative activity to the show called Pan-American Exhibition curated by Willy Kautz, I visited an old photography studio near the NC ARTE gallery. I was hoping to find vintage portraits taken in Bogotá in 1948-1949.

Victor Vilón’s children, Germán and Patricia Vilón, who owned the Vilón Photography Studio, told me that although they had no old photographs they did have some negatives which they would look for to show me. Two days later I turned up punctually for our appointment and both Patricia and Germán had a look of utter frustration: they showed me a cardboard box containing hundreds of negatives that had been destroyed by a flood in the warehouse where they had been stored, which no-one had noticed. Patricia showed me various negatives that were stuck together and would break when separated and told me they were going to throw it all away. When I saw some of the negatives, I found them far more interesting than they would have been if they had not got wet. So I asked Germán if they could print the negatives in their destroyed state and he told me that they could, but that they would turn out badly. I chose a few and asked for examples. A couple of days later, these examples exceeded my expectations. Previously, I would buy vintage photographs from Mexican movies and alter them by randomly tearing part of the film to transform the narrative and configuration through a process of abstraction and destruction.

Before destroying each image I would scan both sides so that each altered photograph could be added to my digital archives.

The destroyed negatives from Archive V.V. had not been altered by me, but by an accident that destroyed them over time, so the artistic process for series like the one on Mexican movies was carried out by time rather than by me. The result is simply amazing. To rescue the negatives from the garbage I asked German and Patricia to sell them to me to keep in Mexico where I could continue experimenting with the series of images.

ZZ. How much do you intervene in the construction of a photographic image and at what point is it beyond your control?

GM. As an artist I like to have control over certain pieces or series, but I also like to lose absolute control over other series in particular, or occasionally combine both: control and randomness.

With regards to the destroyed negatives, or Archive V.V. 1948-49, the majority of alterations were made by the flood and time and the results were the starting point for a new series. When printed, the images were extraordinary, unique, and I did not intervene in them at all except for finding and recovering them. It was like a type of assisted Ready Made, as Francisco Reyes Palma so aptly called it. Once the photos had been printed, I altered them again by tearing part of the photographic film off and leaving the fragments at the bottom of the frame. This begins a process that, depending on the conditions in which the photo is stored, time and light, will cause the image to entirely disappear in maybe 50, 100 or more years, transforming the photo into a monochrome white surface. When this finally happens, the piece will be completed. “The artist only begins the piece, but will never see it finished as its process continues over time even after the artist’s death.”

Back in Mexico, I went to a photography laboratory to print the negatives I had chosen on fiber paper in a similar way. Once they were printed, but before framing them, I altered them randomly, tearing bits of photographic film off and saving them so that after the photo had been framed, they would be at the bottom of the frame.

What most interests me is what happens after the first intervention when the destroyed negative is printed. I intervene again by tearing off small pieces of the image, thereby beginning my piece of work, since time, light and varied storage conditions will complete the piece.

ZZ. When the object mediates between the artist and the spectator, what type of reflection does it incite?

GM. At the end of the day, everything vanishes. Nothing is eternal and everything is subject to constant change and transformation. Art is neither created nor destroyed, only transformed.

In my work, I like to introduce the works. They do everything. There is a an interesting visual, formal and technical factor that makes an initial, perhaps more emotional impact. Afterwards, you can explore what goes on behind the process, and the work itself has various levels of information where one question leads to another, and so on, indefinitely.

When something attracts your attention and you like it but it also makes you think, for me, that is the point where the work becomes whole. Each person will have a different opinion or reaction depending on the level and type of previous information they possess. The images or works in this series, for example, have received differing opinions and reflections. In some people they elicit nostalgia for an era, a person who no longer exists or who died years ago; for others, it produces a certain mystery, or even fear, since some of the faces or images are rather ghostlike.

Personally, I believe that the images are powerful in every respect. They have an extraordinary composition and were, in a way, part of an archive which, when it was destroyed, fulfilled its destiny by becoming waste. This is a footnote for me as an artist, knowing that what comes at the end of one thing can be the beginning of another. This waste or residual material can be transformed into artwork.

When two or more negatives in the archive are stuck together and then break and are fragmented into other images, the way I print them turns them into something extraordinary. They have been altered by time, through a naturally destructive process, making the image into an abstraction with a strange composition. The people still exist in them, or their presence is registered, together with a whole era. Thus the images are historic documents that are transformed into something else.

The original author of these portraits was Don Victor Villamil Vilón, and now I am the author. I love to find new ways of experimenting with photography. I did not originally take these photographs, but I did rescue them from the becoming garbage after they had been destroyed in a flood and now they are prime examples for exploring image through records, archives and documents.

This series of altered photographs comes from a set of negatives that was destroyed when the warehouse where they had been stored for decades was flooded. This is why some of the negatives were stuck together, some of them showing two different takes of the same person and others two or three different people. They are negatives of portraits taken in 1948 and 1949 by Víctor Villamil Vilón at Cano Photography Studios, later called Vilón Photography Studios in Bogotá, Colombia. The images were printed on silver gel with fibrous paper in Mexico City and subsequently altered and framed. The artist begins his work by tearing off pieces of the photo.

Time and light do the rest, erasing the photographic image completely and leaving a monochrome surface. Only then is the work finished. Therefore 50, 100 or 300 years will have to pass, depending on the conditions in which the work is found. The artist never completes the piece and will surely never see it finished. This series is a parallel to the altered space entitled Pan-American Exhibition at NC ARTE.

Gabriel de la Mora (Mexico 1968). Studied a masters in painting, photography and video at the Pratt Institute in New York (2001-2003) and a bachelors in architecture at the Universidad Anáhuac del Norte (1987-1991) in Mexico City. He is currently a member of the Sistema Nacional de Creadores de Arte (2013-2015) and has received a number of awards and grants including the Primer Premio de la VII Bienal de Monterrey FEMSA, the Garcia Robles Fulbright Grant and the Jacques and Natasha Gelman Grant among others. His work as been shown in Mexico and abroad both individually and collectively.

Gabriel de la Mora (Mexico 1968). Studied a masters in painting, photography and video at the Pratt Institute in New York (2001-2003) and a bachelors in architecture at the Universidad Anáhuac del Norte (1987-1991) in Mexico City. He is currently a member of the Sistema Nacional de Creadores de Arte (2013-2015) and has received a number of awards and grants including the Primer Premio de la VII Bienal de Monterrey FEMSA, the Garcia Robles Fulbright Grant and the Jacques and Natasha Gelman Grant among others. His work as been shown in Mexico and abroad both individually and collectively.ZZ. In the project called Archive V.V. 1948 -49 how do you establish the photograph/time relationship? How does it affect the image both as an external and intrinsic element?

GM. Photographic technique is a constantly changing process. Depending upon the passage of time and light, on how the photo has been exposed to these two factors, it can slowly fade and begin to disappear. Which initially worried me for this project. But I think that later this inevitable factor became a starting point for various series in which I used photography as primary or supporting material.

In most of my work, photography is an important element, whether as a file or a document, or a starting point as it was for Willy Kautz in his work shown at the Amparo Museum from October 2014 to February 2015 under the title "What watches us that we don’t see.” The starting point in this exhibit was how an image becomes monochromatic and how a monochrome can become an image.

Although I take photographs to document pieces and processes, amongst many other things, I like to work with vintage photographs from the late 19th to the late 20th century. I buy archives, classify them and then begin my explorations. For the Archive V.V. 1948-49 project I used destroyed negatives for the first time. The alterations were both accidental and due to the passage of time, which produced astounding results.

The Vilón Archive series began in 2012 while I was preparing for my first altered space project at the NC ARTE gallery in Bogotá Colombia. As an alternative activity to the show called Pan-American Exhibition curated by Willy Kautz, I visited an old photography studio near the NC ARTE gallery. I was hoping to find vintage portraits taken in Bogotá in 1948-1949.

Victor Vilón’s children, Germán and Patricia Vilón, who owned the Vilón Photography Studio, told me that although they had no old photographs they did have some negatives which they would look for to show me. Two days later I turned up punctually for our appointment and both Patricia and Germán had a look of utter frustration: they showed me a cardboard box containing hundreds of negatives that had been destroyed by a flood in the warehouse where they had been stored, which no-one had noticed. Patricia showed me various negatives that were stuck together and would break when separated and told me they were going to throw it all away. When I saw some of the negatives, I found them far more interesting than they would have been if they had not got wet. So I asked Germán if they could print the negatives in their destroyed state and he told me that they could, but that they would turn out badly. I chose a few and asked for examples. A couple of days later, these examples exceeded my expectations. Previously, I would buy vintage photographs from Mexican movies and alter them by randomly tearing part of the film to transform the narrative and configuration through a process of abstraction and destruction.

Before destroying each image I would scan both sides so that each altered photograph could be added to my digital archives.

The destroyed negatives from Archive V.V. had not been altered by me, but by an accident that destroyed them over time, so the artistic process for series like the one on Mexican movies was carried out by time rather than by me. The result is simply amazing. To rescue the negatives from the garbage I asked German and Patricia to sell them to me to keep in Mexico where I could continue experimenting with the series of images.

ZZ. How much do you intervene in the construction of a photographic image and at what point is it beyond your control?

GM. As an artist I like to have control over certain pieces or series, but I also like to lose absolute control over other series in particular, or occasionally combine both: control and randomness.

With regards to the destroyed negatives, or Archive V.V. 1948-49, the majority of alterations were made by the flood and time and the results were the starting point for a new series. When printed, the images were extraordinary, unique, and I did not intervene in them at all except for finding and recovering them. It was like a type of assisted Ready Made, as Francisco Reyes Palma so aptly called it. Once the photos had been printed, I altered them again by tearing part of the photographic film off and leaving the fragments at the bottom of the frame. This begins a process that, depending on the conditions in which the photo is stored, time and light, will cause the image to entirely disappear in maybe 50, 100 or more years, transforming the photo into a monochrome white surface. When this finally happens, the piece will be completed. “The artist only begins the piece, but will never see it finished as its process continues over time even after the artist’s death.”

Back in Mexico, I went to a photography laboratory to print the negatives I had chosen on fiber paper in a similar way. Once they were printed, but before framing them, I altered them randomly, tearing bits of photographic film off and saving them so that after the photo had been framed, they would be at the bottom of the frame.

What most interests me is what happens after the first intervention when the destroyed negative is printed. I intervene again by tearing off small pieces of the image, thereby beginning my piece of work, since time, light and varied storage conditions will complete the piece.

ZZ. When the object mediates between the artist and the spectator, what type of reflection does it incite?

GM. At the end of the day, everything vanishes. Nothing is eternal and everything is subject to constant change and transformation. Art is neither created nor destroyed, only transformed.

In my work, I like to introduce the works. They do everything. There is a an interesting visual, formal and technical factor that makes an initial, perhaps more emotional impact. Afterwards, you can explore what goes on behind the process, and the work itself has various levels of information where one question leads to another, and so on, indefinitely.

When something attracts your attention and you like it but it also makes you think, for me, that is the point where the work becomes whole. Each person will have a different opinion or reaction depending on the level and type of previous information they possess. The images or works in this series, for example, have received differing opinions and reflections. In some people they elicit nostalgia for an era, a person who no longer exists or who died years ago; for others, it produces a certain mystery, or even fear, since some of the faces or images are rather ghostlike.

Personally, I believe that the images are powerful in every respect. They have an extraordinary composition and were, in a way, part of an archive which, when it was destroyed, fulfilled its destiny by becoming waste. This is a footnote for me as an artist, knowing that what comes at the end of one thing can be the beginning of another. This waste or residual material can be transformed into artwork.

When two or more negatives in the archive are stuck together and then break and are fragmented into other images, the way I print them turns them into something extraordinary. They have been altered by time, through a naturally destructive process, making the image into an abstraction with a strange composition. The people still exist in them, or their presence is registered, together with a whole era. Thus the images are historic documents that are transformed into something else.

The original author of these portraits was Don Victor Villamil Vilón, and now I am the author. I love to find new ways of experimenting with photography. I did not originally take these photographs, but I did rescue them from the becoming garbage after they had been destroyed in a flood and now they are prime examples for exploring image through records, archives and documents.

Andrea Dorliguzzo

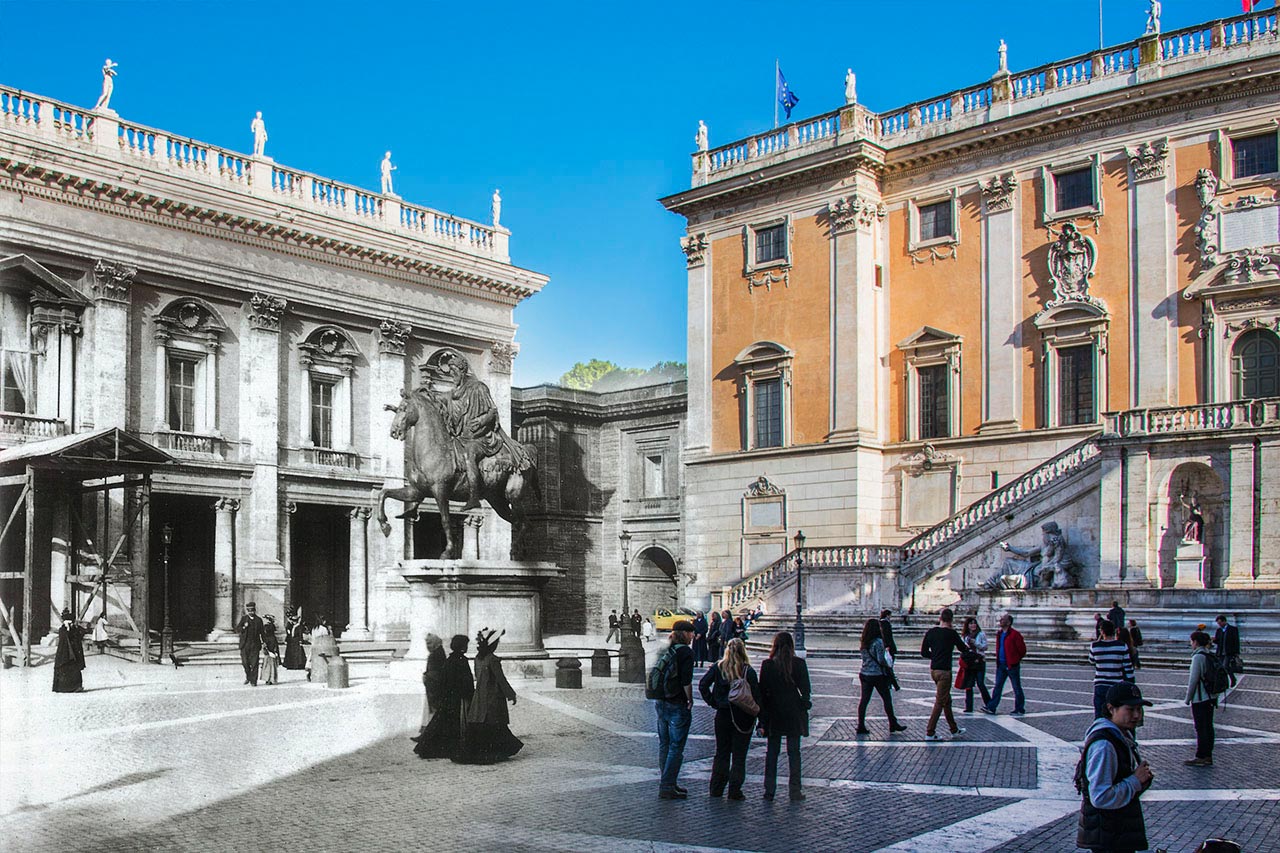

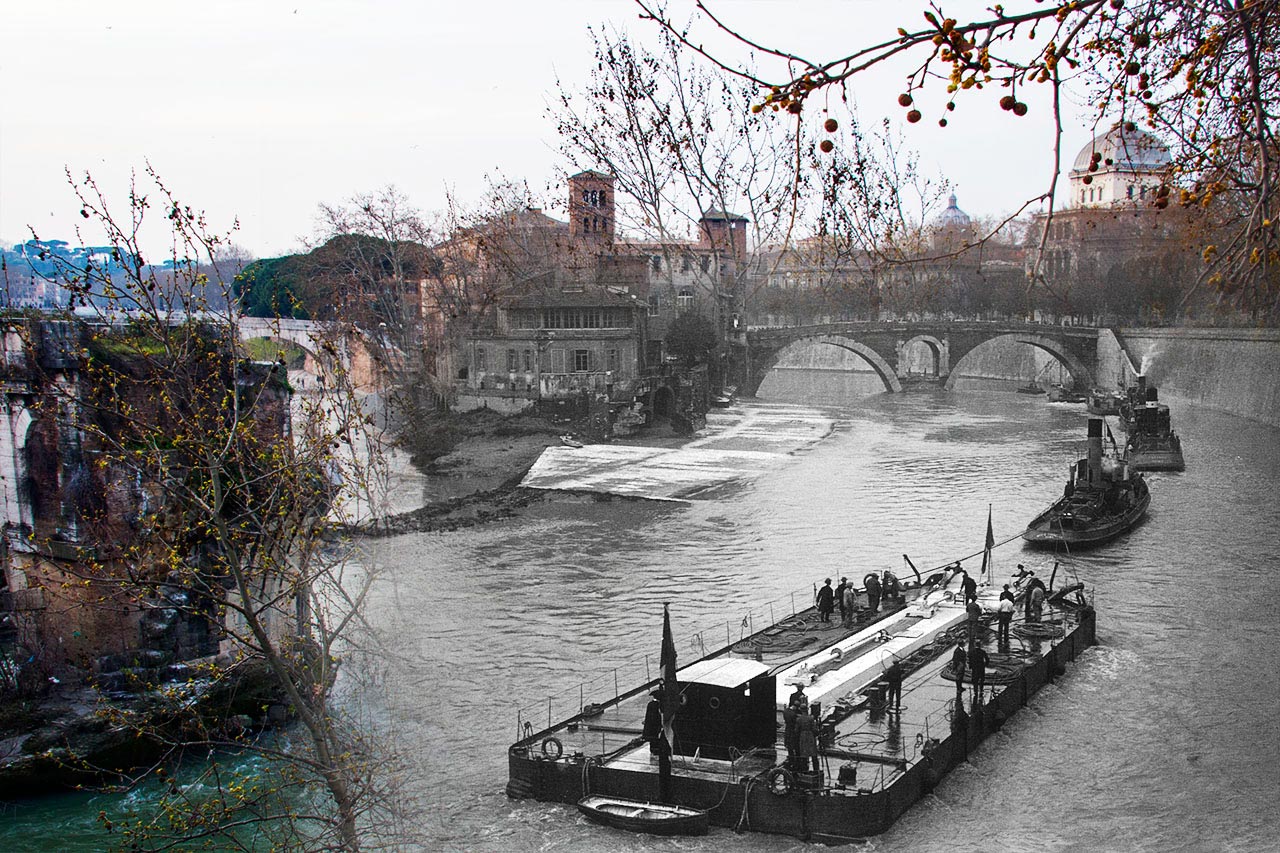

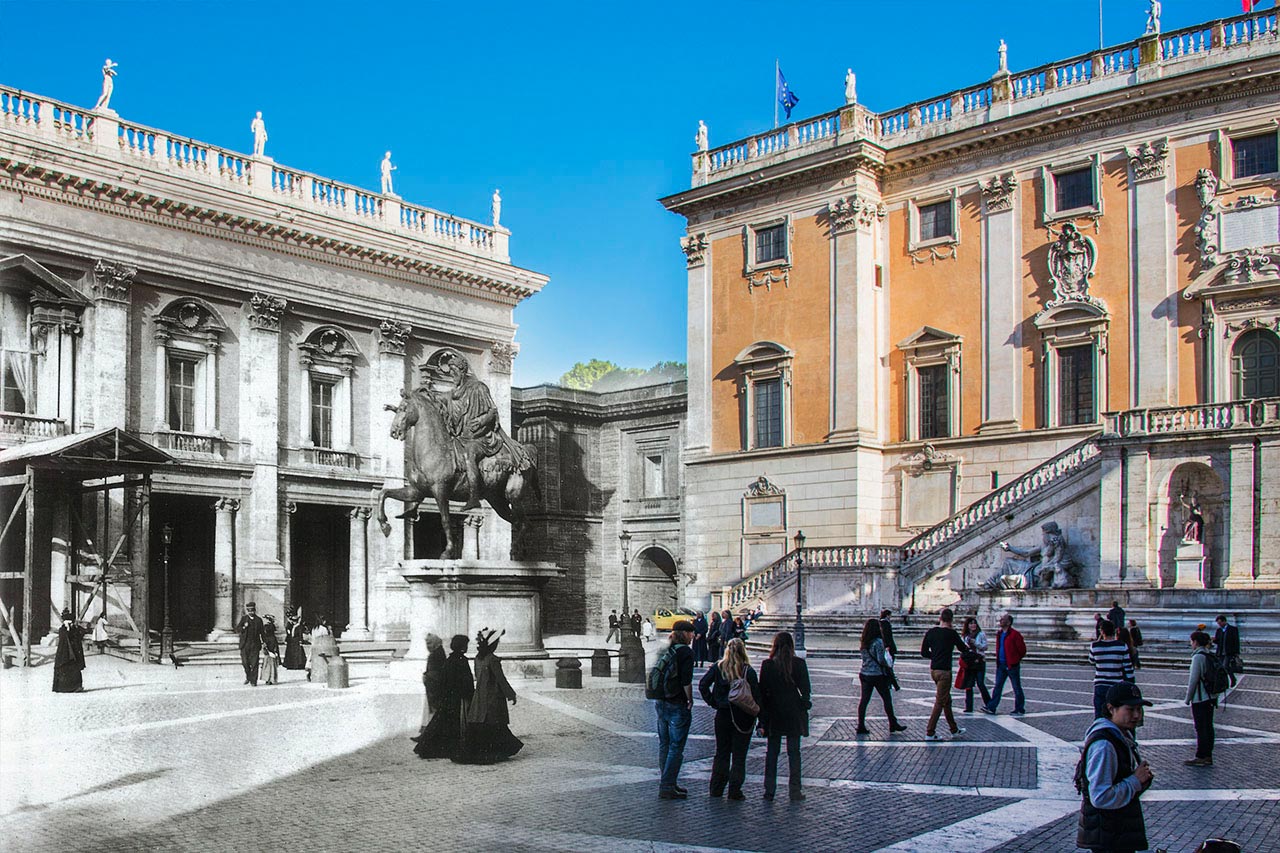

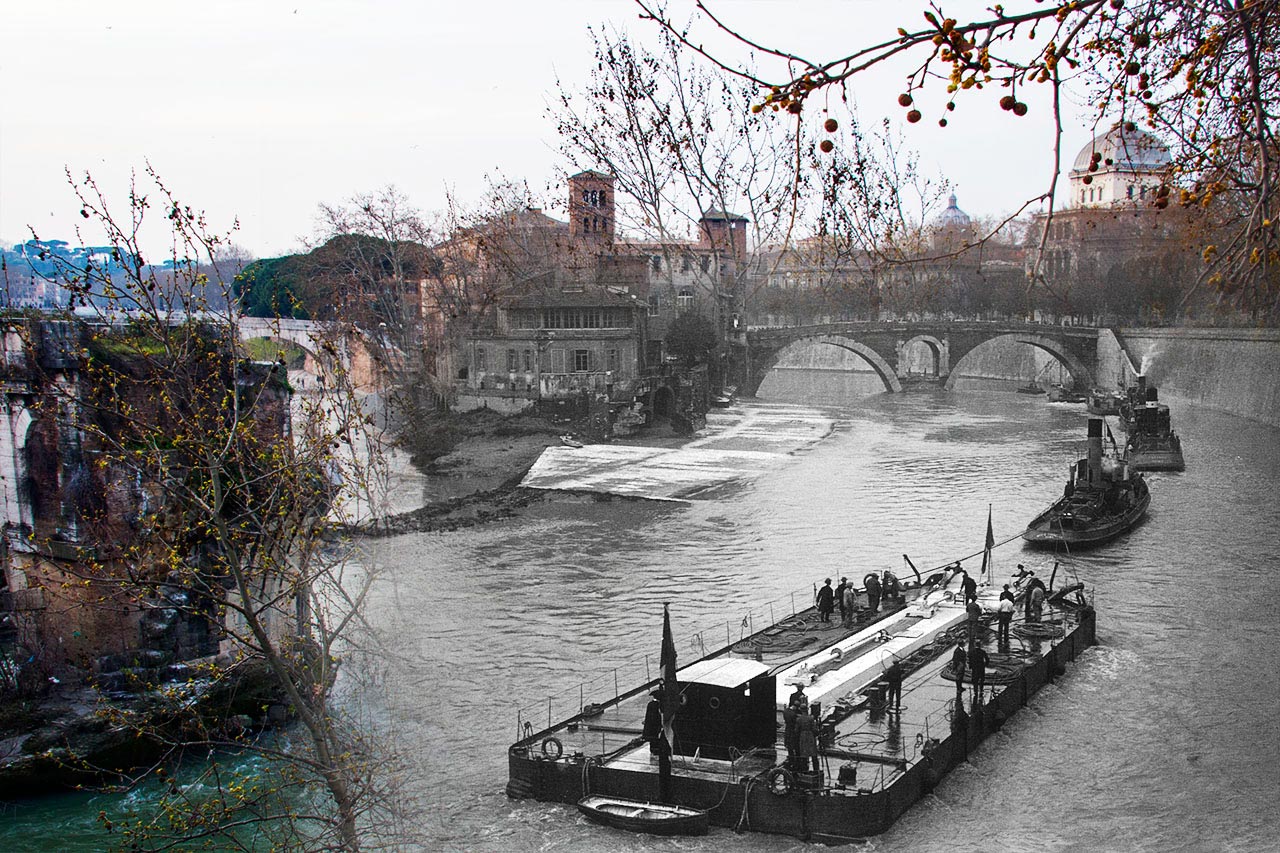

In 2013, Andrea Dorliguzzo started with his rephotography project Roma Ieri Oggi (Rome Yesterday Today). Driven by his passion for photography and his admiration for Rome, he started to collect old photographs of the city and combined these with contemporary ones, taken at exactly the same spot. In this way, the past and the present are brought together, causing a thrilling historical sensation which reminds us of all the great stories that the city has to tell.

Andrea Dorliguzzo (Italy) was born in Friuli, in the north-east part of Italy. A few years ago, he moved to Rome. His passion for photography was born quite recently. Over the last years, he had the luck of traveling a lot and bringing home an unimaginable number of pictures and memories. Regarding his photos, he is very critical and only a small selection is published on his photo blog.

Andrea Dorliguzzo (Italy) was born in Friuli, in the north-east part of Italy. A few years ago, he moved to Rome. His passion for photography was born quite recently. Over the last years, he had the luck of traveling a lot and bringing home an unimaginable number of pictures and memories. Regarding his photos, he is very critical and only a small selection is published on his photo blog.

In 2013, Andrea Dorliguzzo started with his rephotography project Roma Ieri Oggi (Rome Yesterday Today). Driven by his passion for photography and his admiration for Rome, he started to collect old photographs of the city and combined these with contemporary ones, taken at exactly the same spot. In this way, the past and the present are brought together, causing a thrilling historical sensation which reminds us of all the great stories that the city has to tell.

Andrea Dorliguzzo (Italy) was born in Friuli, in the north-east part of Italy. A few years ago, he moved to Rome. His passion for photography was born quite recently. Over the last years, he had the luck of traveling a lot and bringing home an unimaginable number of pictures and memories. Regarding his photos, he is very critical and only a small selection is published on his photo blog.

Andrea Dorliguzzo (Italy) was born in Friuli, in the north-east part of Italy. A few years ago, he moved to Rome. His passion for photography was born quite recently. Over the last years, he had the luck of traveling a lot and bringing home an unimaginable number of pictures and memories. Regarding his photos, he is very critical and only a small selection is published on his photo blog.Virgil Widrich

Copy Shop, 2001

Written, directed, produced, edited by Virgil Widrich

An original copy film. 2001, 35mm. b/w, 12 min. sound, no dialogue.

The film Copy Shop actually consist of nearly 18,000 photocopied digital frames, which are animated and filmed with a 35mm camera.

Virgil Widrich (Salzburg, 1967). Lives in Vienna. He works on numerous multimedia and film productions. His first feature film is Heller als der Mond (Brighter than the Moon). His short film Copy Shop won 35 international awards and was nominated for the Oscar. Fast Film premiered in Cannes 2003 and won 36 awards until today. At the moment Widrich is working on a new feature film The Night of a Thousand Hours.

Virgil Widrich (Salzburg, 1967). Lives in Vienna. He works on numerous multimedia and film productions. His first feature film is Heller als der Mond (Brighter than the Moon). His short film Copy Shop won 35 international awards and was nominated for the Oscar. Fast Film premiered in Cannes 2003 and won 36 awards until today. At the moment Widrich is working on a new feature film The Night of a Thousand Hours.Copy Shop, 2001

Written, directed, produced, edited by Virgil Widrich

An original copy film. 2001, 35mm. b/w, 12 min. sound, no dialogue.

The film Copy Shop actually consist of nearly 18,000 photocopied digital frames, which are animated and filmed with a 35mm camera.

Virgil Widrich (Salzburg, 1967). Lives in Vienna. He works on numerous multimedia and film productions. His first feature film is Heller als der Mond (Brighter than the Moon). His short film Copy Shop won 35 international awards and was nominated for the Oscar. Fast Film premiered in Cannes 2003 and won 36 awards until today. At the moment Widrich is working on a new feature film The Night of a Thousand Hours.

Virgil Widrich (Salzburg, 1967). Lives in Vienna. He works on numerous multimedia and film productions. His first feature film is Heller als der Mond (Brighter than the Moon). His short film Copy Shop won 35 international awards and was nominated for the Oscar. Fast Film premiered in Cannes 2003 and won 36 awards until today. At the moment Widrich is working on a new feature film The Night of a Thousand Hours.ZoneZero

Interview with Virgil Widrich about his work. February 2015

Virgil Widrich (Salzburg, 1967). Lives in Vienna. He works on numerous multimedia and film productions. His first feature film is Heller als der Mond (Brighter than the Moon). His short film Copy Shop won 35 international awards and was nominated for the Oscar. Fast Film premiered in Cannes 2003 and won 36 awards until today. At the moment Widrich is working on a new feature film The Night of a Thousand Hours.

Virgil Widrich (Salzburg, 1967). Lives in Vienna. He works on numerous multimedia and film productions. His first feature film is Heller als der Mond (Brighter than the Moon). His short film Copy Shop won 35 international awards and was nominated for the Oscar. Fast Film premiered in Cannes 2003 and won 36 awards until today. At the moment Widrich is working on a new feature film The Night of a Thousand Hours.Interview with Virgil Widrich about his work. February 2015

Virgil Widrich (Salzburg, 1967). Lives in Vienna. He works on numerous multimedia and film productions. His first feature film is Heller als der Mond (Brighter than the Moon). His short film Copy Shop won 35 international awards and was nominated for the Oscar. Fast Film premiered in Cannes 2003 and won 36 awards until today. At the moment Widrich is working on a new feature film The Night of a Thousand Hours.

Virgil Widrich (Salzburg, 1967). Lives in Vienna. He works on numerous multimedia and film productions. His first feature film is Heller als der Mond (Brighter than the Moon). His short film Copy Shop won 35 international awards and was nominated for the Oscar. Fast Film premiered in Cannes 2003 and won 36 awards until today. At the moment Widrich is working on a new feature film The Night of a Thousand Hours.Alejandro Malo

by Eadweard Muybridge

The fleeting today is tenuous and eternal;

Don’t wait for another Heaven or Hell.

—Jorge Luis Borges.

Photography is thought of as a way to freeze time and people rarely discuss how much time each photographic instant really represents. From the more than eight hours taken to shoot View from the Window at Le Gras to the fifteen minutes for Boulevard du Temple, to the speeds achieved in the past decade of more than a billion frames per second, each photograph prolongs a fiction in which we desire to see the ever-changing world imprisoned before our gaze. Movies, like theater and dance, derived from photographs precisely their desire to represent this same ever-changing world, but without being confined to an instant or synthesizing something living into a fixed image. The work of Muybridge and Marey, by capturing sequential movement and reproducing it in fixed or animated images, addressed these aspects which appeared to draw one path for photography and another for cinematography.

Decades later, communication vessels became popular, blurring the boundaries between these mediums. Photographic time extends itself in anyone’s hands and an image, previously immobile, unfolds instantly into movement with any number of applications such as Vine, Instagram, Cinemagram and others. With increasing frequency, photographers offer video work as part of their professional activities and create time-lapse or rephotography images to convey events that extend beyond the limits of a series or a single shot. Likewise, movies have shifted from the surprise occasioned by works like Chris Marker’s La Jetée (1962) and the flat sequences of Antonioni that scandalized Cannes in 1960 to a visual fascination with suspended, almost immobile shots, as in the Tarkovsky movies. Current cinematography often employs flat sequence structure, or imitates Ken Burns by recovering photographic files through a specific video editing effect named after him.

Tonino Guerra, in the preface to Instant Light: Tarkovsky Polaroids, anecdotes about how both Tarkovsky and Antonioni used Polaroid cameras in the late 1970s. The former was constantly worried about the volatility of time and his desire to freeze it in these instant images; it is not difficult to imagine how this impacted his movies. The latter discusses how, during a location scouting trip to Uzbekistan, an old man rejected a photograph recently take of him and two friends by asking: "¿“Why stop time?” to which neither man could respond. And this invites the questions: If photography is a way to stop time, how much time and how much mobility can an instant comprise? And no less important, how much do movies actually escape from their photographic desire to stop time, even though it captures entire lifetimes or historic moments?

The first question has been tested in a number of projects, and the opportunity to represent the variability of time has multiplied with the immediacy of available tools. The visual language permitted by cameras has led to the proliferation of works where years become a chronograph, days are the sun’s accelerated journey across the horizon, people are frozen in 360 degrees and cameras slow down or speed up at the pace of a silent film. Movies have their own experimental territory where more frequent use of the flat sequence and found footage, real or fictitious, and the recording and recovery of material in lapses is increasingly prolonged. The bridge between what was considered a brief, decisive instant and what was considered a long, narrative instant is constantly lengthening. The fields of photography and film are more accessible, and the instant, more relative. This freedom is worth exploring.

Alejandro Malo (Mexico, 1972). Lives and works in Mexico and is the director of ZoneZero. Since 1993, he has taken part in various cultural projects and worked as an information technology consultant. He has collaborated in print and electronic publications, and given workshops and conferences on literature, creative writing, storytelling and technology. In 2009, Malo joined the team of the Fundación Pedro Meyer, where he directs the Archives and Technology departments.

Alejandro Malo (Mexico, 1972). Lives and works in Mexico and is the director of ZoneZero. Since 1993, he has taken part in various cultural projects and worked as an information technology consultant. He has collaborated in print and electronic publications, and given workshops and conferences on literature, creative writing, storytelling and technology. In 2009, Malo joined the team of the Fundación Pedro Meyer, where he directs the Archives and Technology departments.[core_state] => 1 [core_access] => 1 [core_metadata] => {"robots":"","author":"Alejandro Malo","rights":"","xreference":""} [core_created_user_id] => 841 [core_created_by_alias] => [core_created_time] => 2015-02-18 20:11:20 [core_images] => {"image_intro":"images\/categories\/temporality\/Muybridge_race_horse_animated.gif","float_intro":"","image_intro_alt":"","image_intro_caption":"","image_fulltext":"images\/categories\/temporality\/Muybridge_race_horse_animated.gif","float_fulltext":"","image_fulltext_alt":"","image_fulltext_caption":""} [core_modified_time] => 2015-06-01 18:12:34 [core_language] => en-GB [core_catid] => 57 [core_publish_up] => 2015-02-18 20:11:20 [core_publish_down] => 0000-00-00 00:00:00 [content_type_title] => Article [router] => ContentHelperRoute::getArticleRoute [author] => [author_email] => [link] => index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=257:the-many-moments-of-the-instant&catid=57&lang=en-GB [displayDate] => 2015-02-18 20:11:20 [event] => stdClass Object ( [afterDisplayTitle] => [beforeDisplayContent] => [afterDisplayContent] => ) [text] =>

by Eadweard Muybridge

The fleeting today is tenuous and eternal;

Don’t wait for another Heaven or Hell.

—Jorge Luis Borges.

Photography is thought of as a way to freeze time and people rarely discuss how much time each photographic instant really represents. From the more than eight hours taken to shoot View from the Window at Le Gras to the fifteen minutes for Boulevard du Temple, to the speeds achieved in the past decade of more than a billion frames per second, each photograph prolongs a fiction in which we desire to see the ever-changing world imprisoned before our gaze. Movies, like theater and dance, derived from photographs precisely their desire to represent this same ever-changing world, but without being confined to an instant or synthesizing something living into a fixed image. The work of Muybridge and Marey, by capturing sequential movement and reproducing it in fixed or animated images, addressed these aspects which appeared to draw one path for photography and another for cinematography.

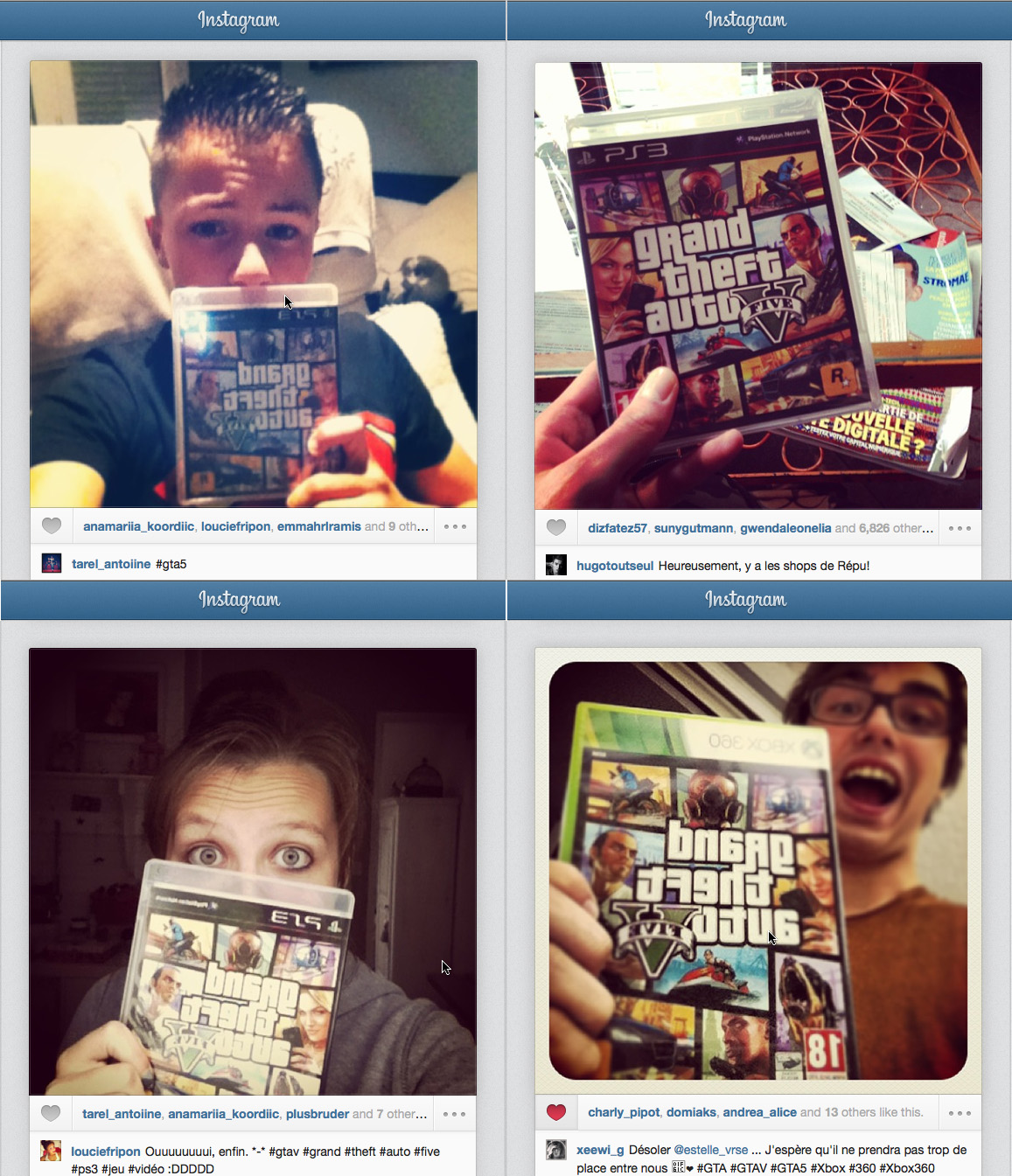

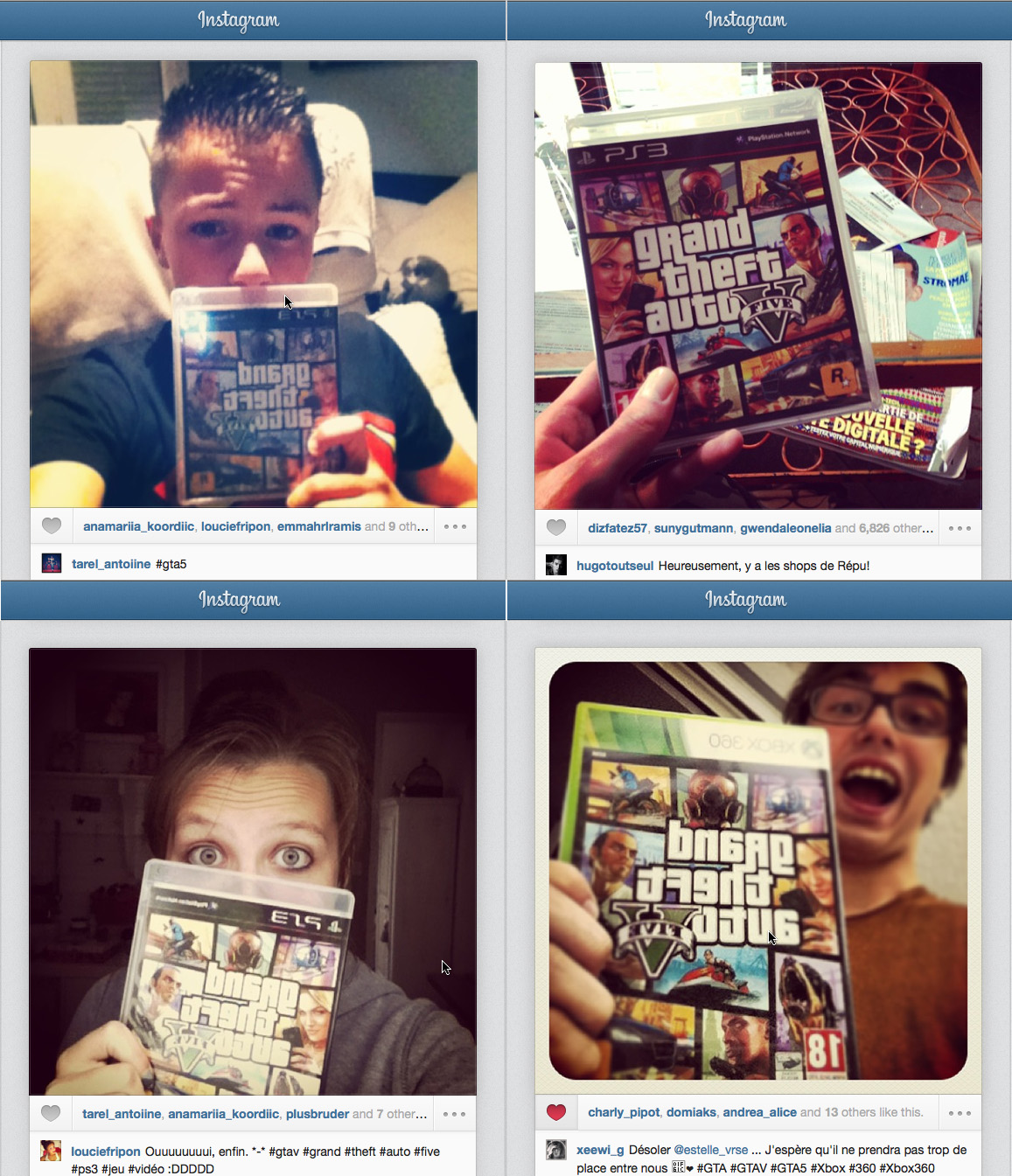

Decades later, communication vessels became popular, blurring the boundaries between these mediums. Photographic time extends itself in anyone’s hands and an image, previously immobile, unfolds instantly into movement with any number of applications such as Vine, Instagram, Cinemagram and others. With increasing frequency, photographers offer video work as part of their professional activities and create time-lapse or rephotography images to convey events that extend beyond the limits of a series or a single shot. Likewise, movies have shifted from the surprise occasioned by works like Chris Marker’s La Jetée (1962) and the flat sequences of Antonioni that scandalized Cannes in 1960 to a visual fascination with suspended, almost immobile shots, as in the Tarkovsky movies. Current cinematography often employs flat sequence structure, or imitates Ken Burns by recovering photographic files through a specific video editing effect named after him.

Tonino Guerra, in the preface to Instant Light: Tarkovsky Polaroids, anecdotes about how both Tarkovsky and Antonioni used Polaroid cameras in the late 1970s. The former was constantly worried about the volatility of time and his desire to freeze it in these instant images; it is not difficult to imagine how this impacted his movies. The latter discusses how, during a location scouting trip to Uzbekistan, an old man rejected a photograph recently take of him and two friends by asking: "¿“Why stop time?” to which neither man could respond. And this invites the questions: If photography is a way to stop time, how much time and how much mobility can an instant comprise? And no less important, how much do movies actually escape from their photographic desire to stop time, even though it captures entire lifetimes or historic moments?

The first question has been tested in a number of projects, and the opportunity to represent the variability of time has multiplied with the immediacy of available tools. The visual language permitted by cameras has led to the proliferation of works where years become a chronograph, days are the sun’s accelerated journey across the horizon, people are frozen in 360 degrees and cameras slow down or speed up at the pace of a silent film. Movies have their own experimental territory where more frequent use of the flat sequence and found footage, real or fictitious, and the recording and recovery of material in lapses is increasingly prolonged. The bridge between what was considered a brief, decisive instant and what was considered a long, narrative instant is constantly lengthening. The fields of photography and film are more accessible, and the instant, more relative. This freedom is worth exploring.

Alejandro Malo (Mexico, 1972). Lives and works in Mexico and is the director of ZoneZero. Since 1993, he has taken part in various cultural projects and worked as an information technology consultant. He has collaborated in print and electronic publications, and given workshops and conferences on literature, creative writing, storytelling and technology. In 2009, Malo joined the team of the Fundación Pedro Meyer, where he directs the Archives and Technology departments.

Alejandro Malo (Mexico, 1972). Lives and works in Mexico and is the director of ZoneZero. Since 1993, he has taken part in various cultural projects and worked as an information technology consultant. He has collaborated in print and electronic publications, and given workshops and conferences on literature, creative writing, storytelling and technology. In 2009, Malo joined the team of the Fundación Pedro Meyer, where he directs the Archives and Technology departments.[id] => 257 [language] => en-GB [catid] => 57 [jcfields] => Array ( ) ) 1

Zone Zero

Andy Joule uses a combination of traditional and digital techniques, such as stop-motion, multi-layered image sequences and time-lapse. His time-lapses are more than just a technical sensation, closer to the fields of experimental video or fictional documentary. Time becomes the protagonist. Objects that seem to be inert at first, begin to change; a process that only becomes visible by the layer of time that is put over the presented sequences. In this way, the work of Joule brings about the manipulation, deconstruction and reinterpretation of time and space, proposing unconventional narratives and new ways of understanding time in short audiovisual formats.

SALVAGE

SALVAGEInspired by a quote from the naturalist Jacques Yves Cousteau, this film explores the way in which nature clings to life, finds a foothold, and ultimately reclaims what is hers. The solidity of these metal beasts is questioned as the rust and flake slowly leak into the ground.

ELIPSIS

ELIPSIS Andy Joule is a film-maker and animator. He studied animation at West Surrey College of Art & Design. After graduating he worked in London, Manchester, Bristol, the Netherlands and in the US. His films have been screened in festivals and competitions around the world. He has lectured at Volda University College, Norway and is a Senior Lecturer in Animation at the University for the Creative Arts. He is also a BAFTA juror and a Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts.

Andy Joule is a film-maker and animator. He studied animation at West Surrey College of Art & Design. After graduating he worked in London, Manchester, Bristol, the Netherlands and in the US. His films have been screened in festivals and competitions around the world. He has lectured at Volda University College, Norway and is a Senior Lecturer in Animation at the University for the Creative Arts. He is also a BAFTA juror and a Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts.Andy Joule uses a combination of traditional and digital techniques, such as stop-motion, multi-layered image sequences and time-lapse. His time-lapses are more than just a technical sensation, closer to the fields of experimental video or fictional documentary. Time becomes the protagonist. Objects that seem to be inert at first, begin to change; a process that only becomes visible by the layer of time that is put over the presented sequences. In this way, the work of Joule brings about the manipulation, deconstruction and reinterpretation of time and space, proposing unconventional narratives and new ways of understanding time in short audiovisual formats.

SALVAGE

SALVAGEInspired by a quote from the naturalist Jacques Yves Cousteau, this film explores the way in which nature clings to life, finds a foothold, and ultimately reclaims what is hers. The solidity of these metal beasts is questioned as the rust and flake slowly leak into the ground.

ELIPSIS

ELIPSIS Andy Joule is a film-maker and animator. He studied animation at West Surrey College of Art & Design. After graduating he worked in London, Manchester, Bristol, the Netherlands and in the US. His films have been screened in festivals and competitions around the world. He has lectured at Volda University College, Norway and is a Senior Lecturer in Animation at the University for the Creative Arts. He is also a BAFTA juror and a Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts.

Andy Joule is a film-maker and animator. He studied animation at West Surrey College of Art & Design. After graduating he worked in London, Manchester, Bristol, the Netherlands and in the US. His films have been screened in festivals and competitions around the world. He has lectured at Volda University College, Norway and is a Senior Lecturer in Animation at the University for the Creative Arts. He is also a BAFTA juror and a Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts.Kent Krugh

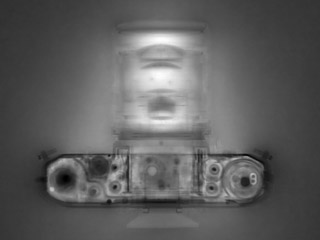

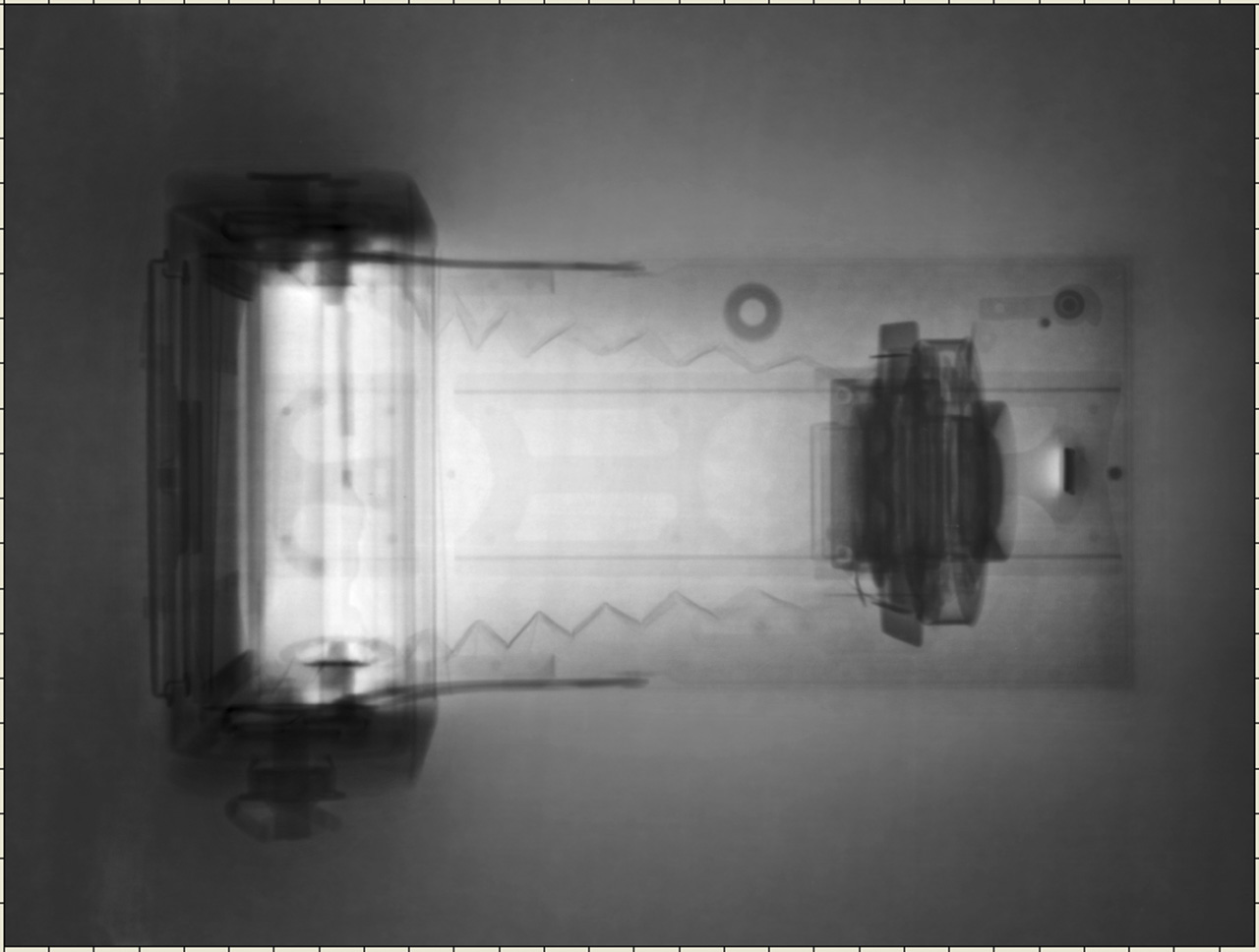

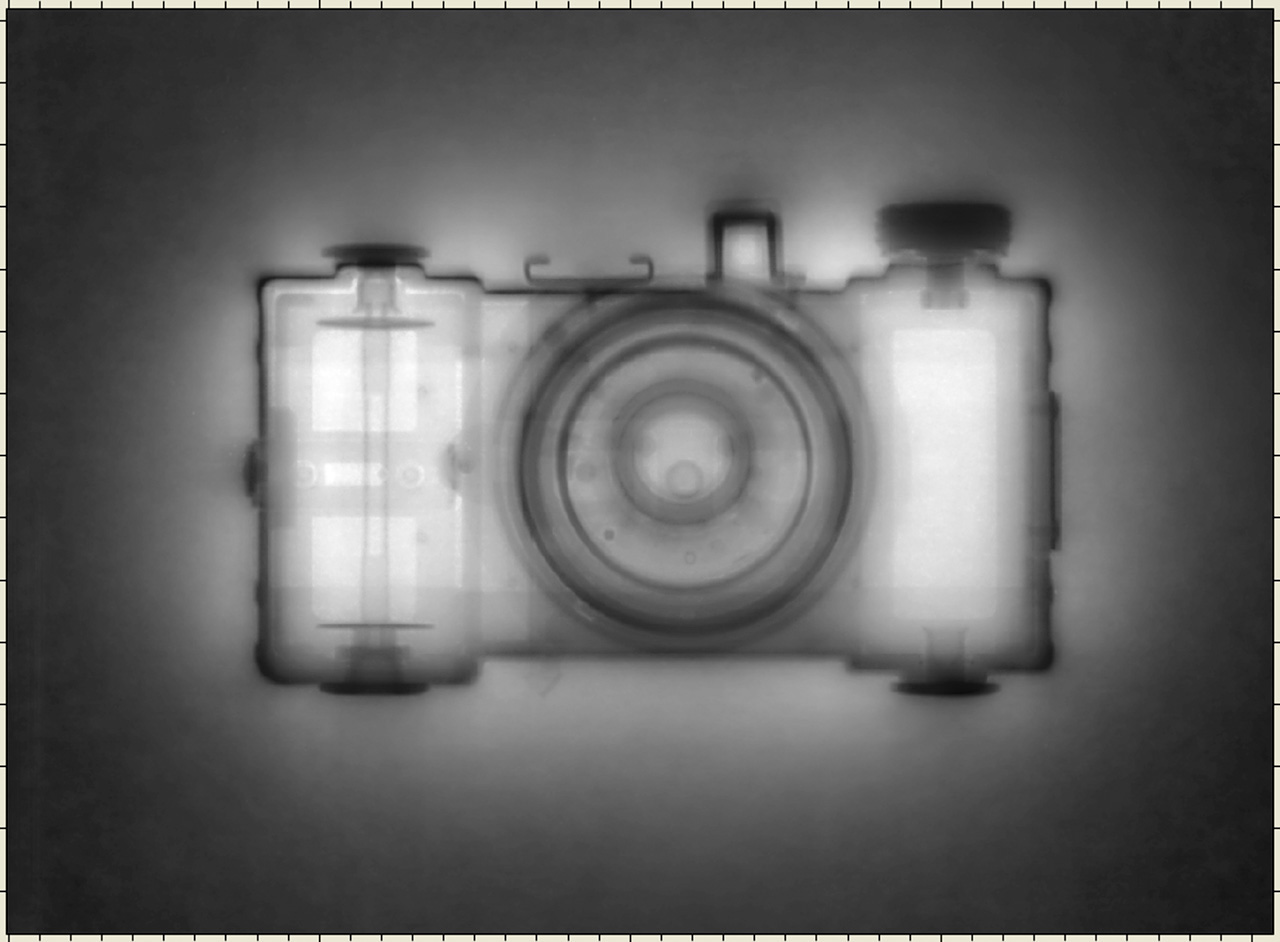

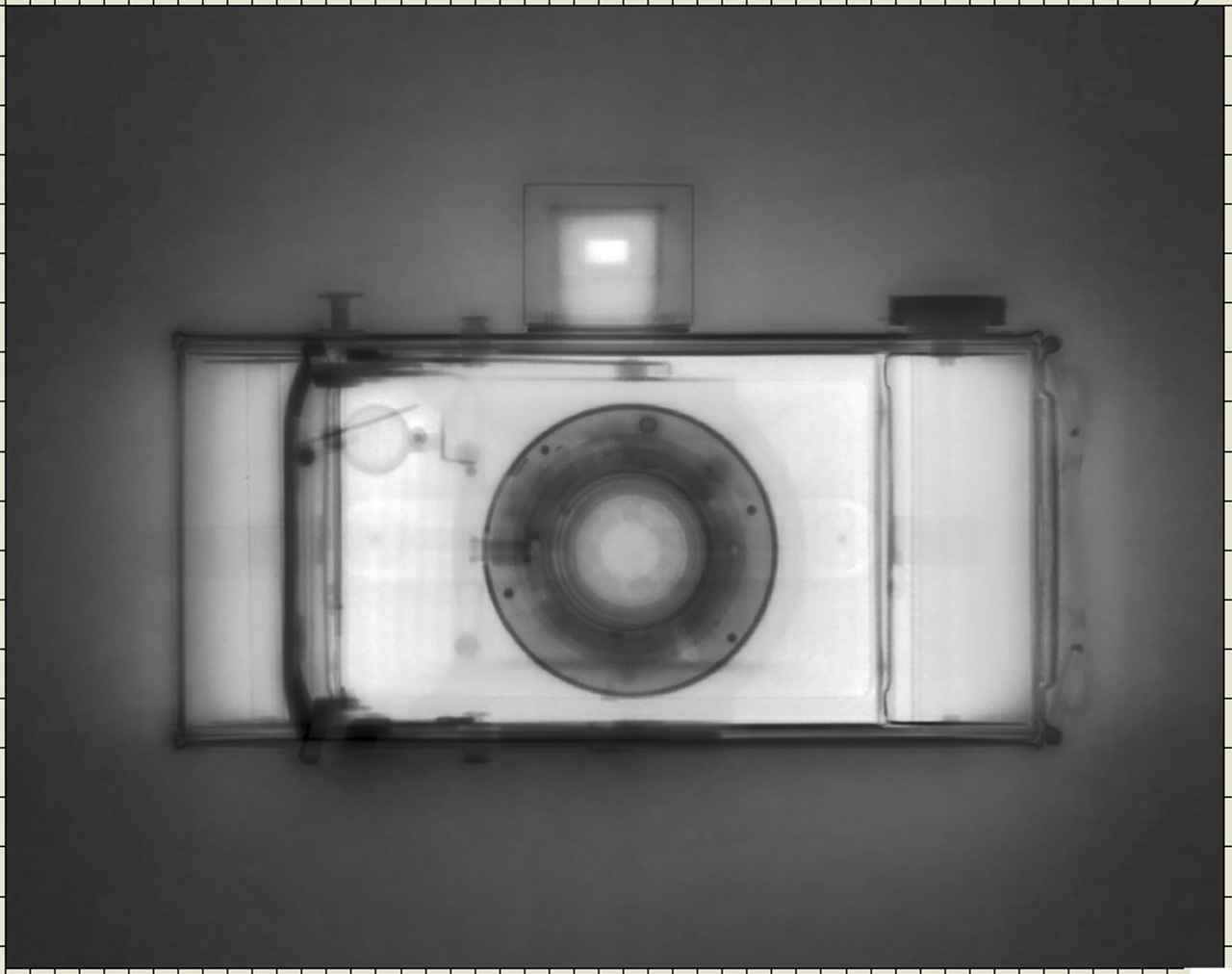

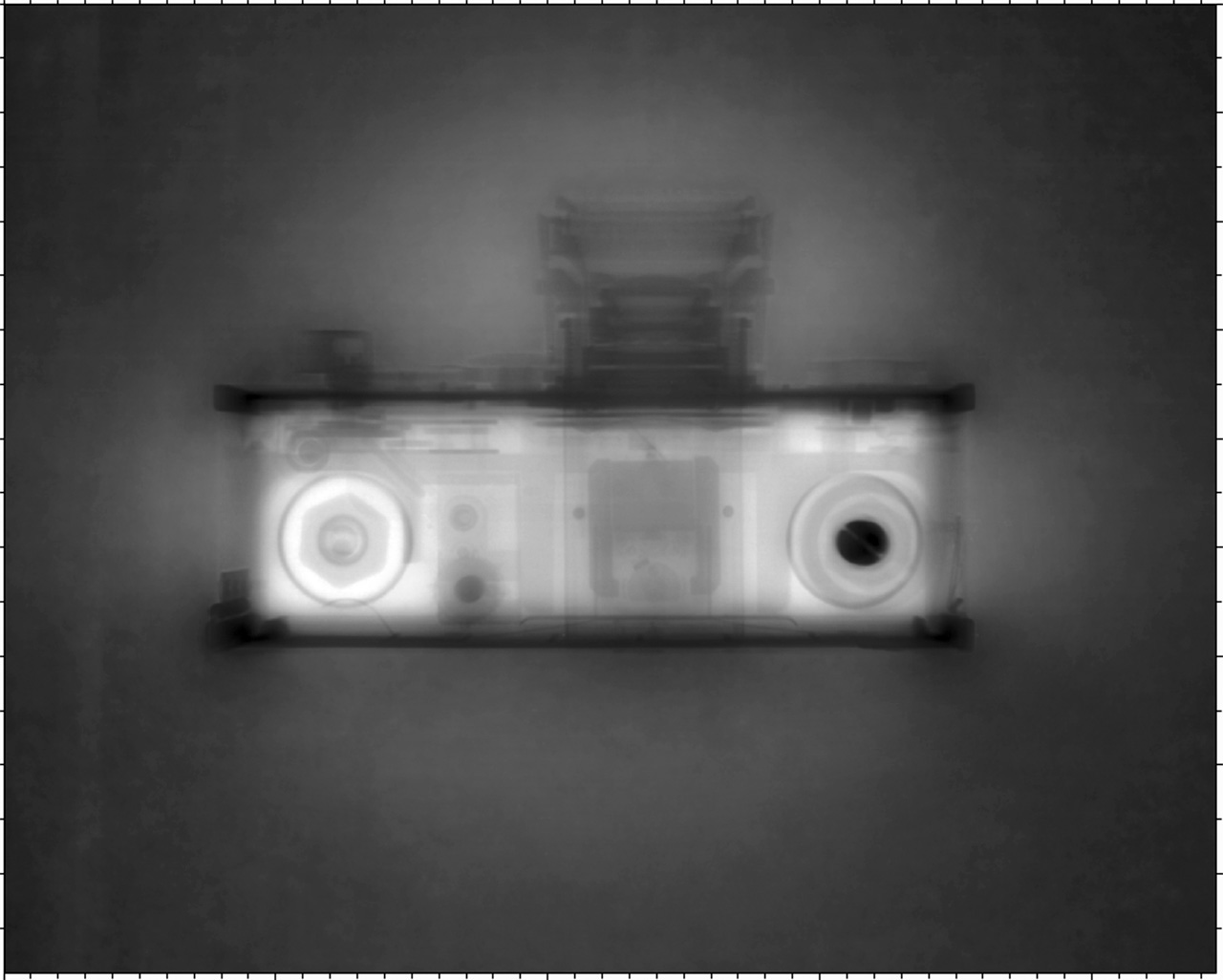

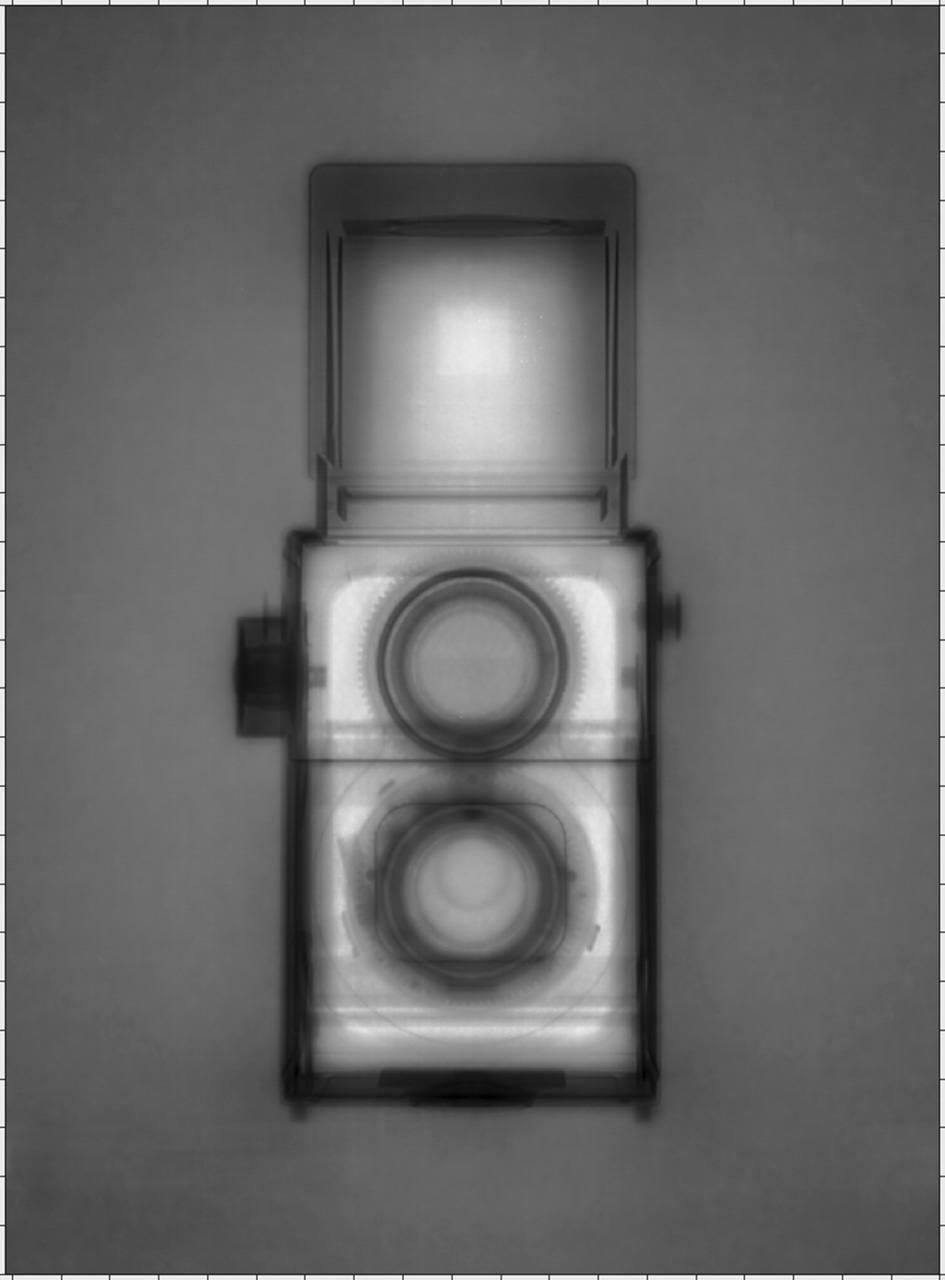

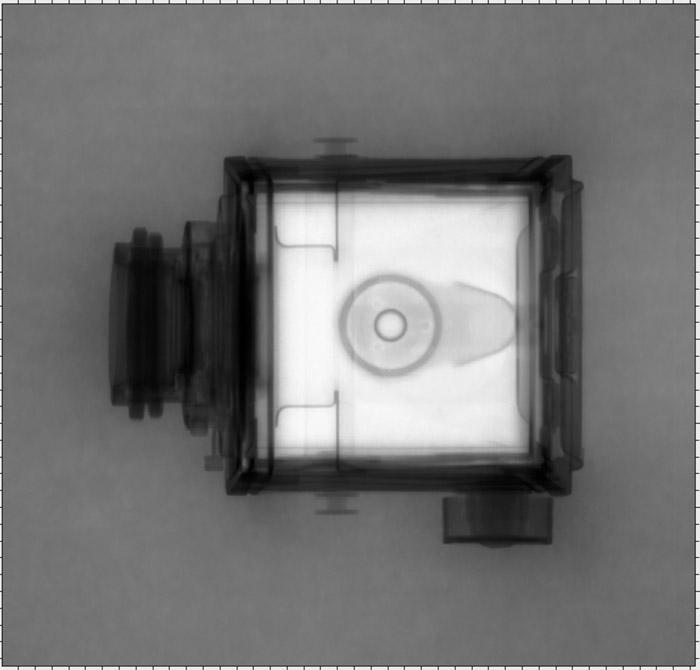

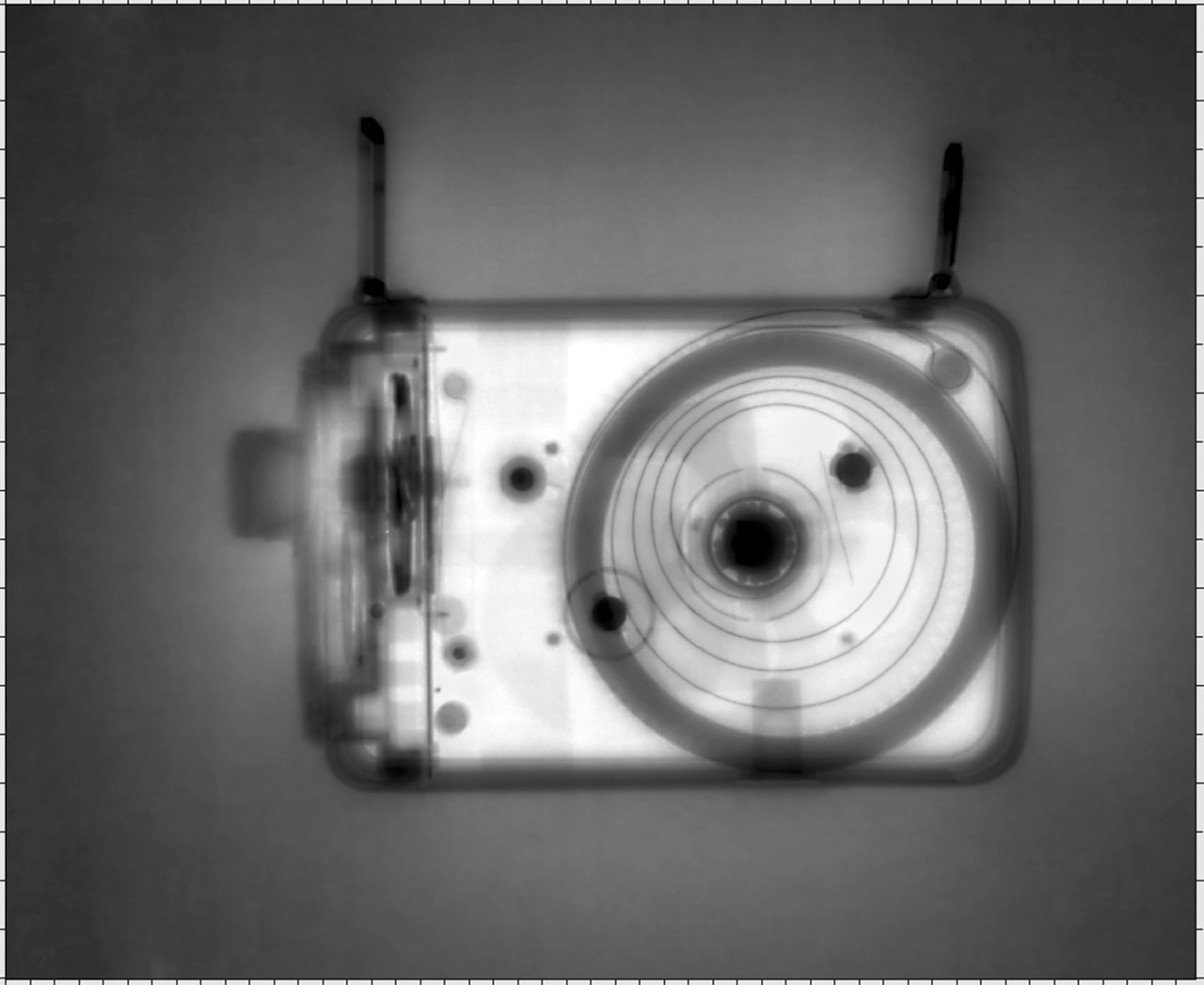

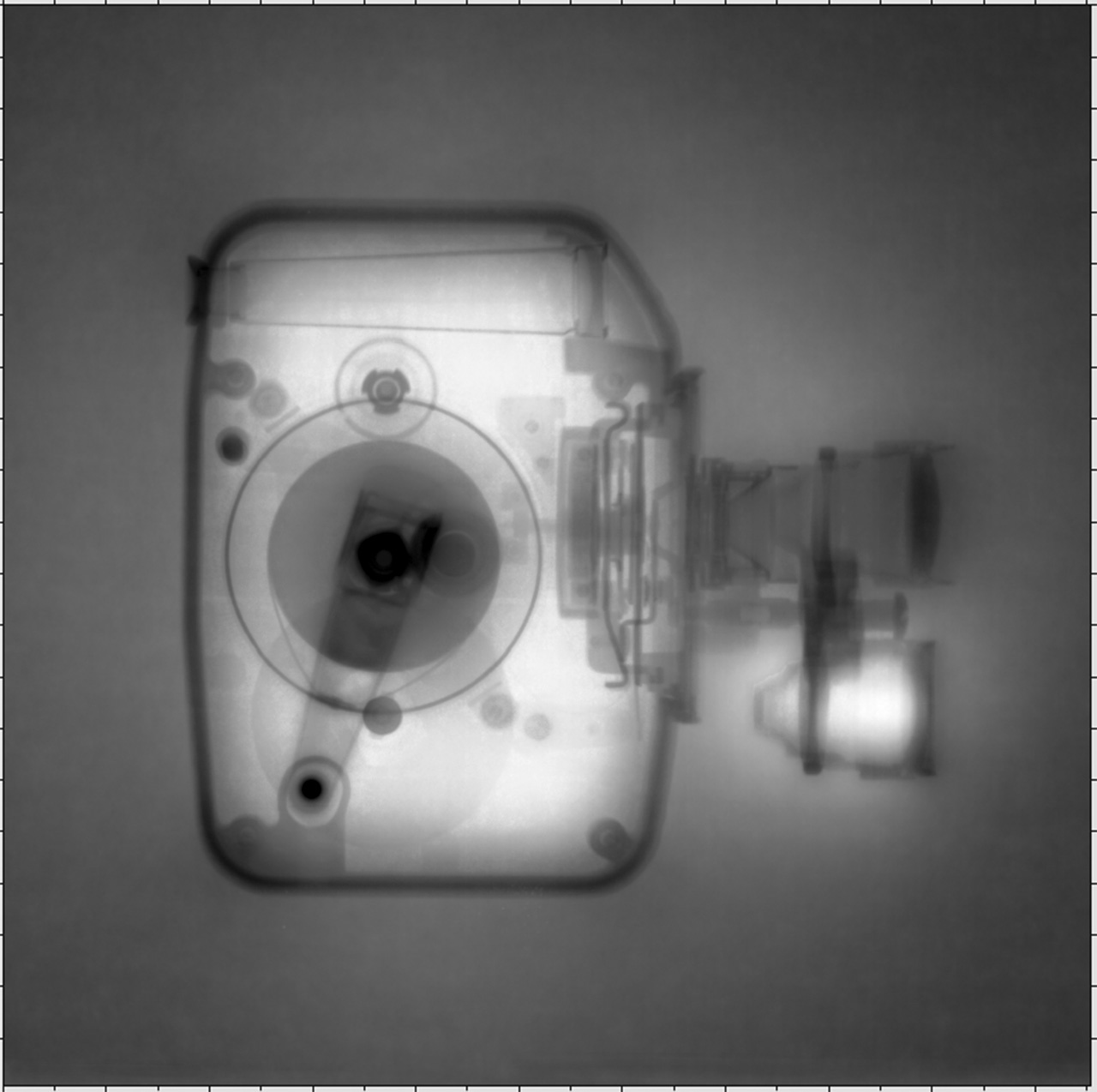

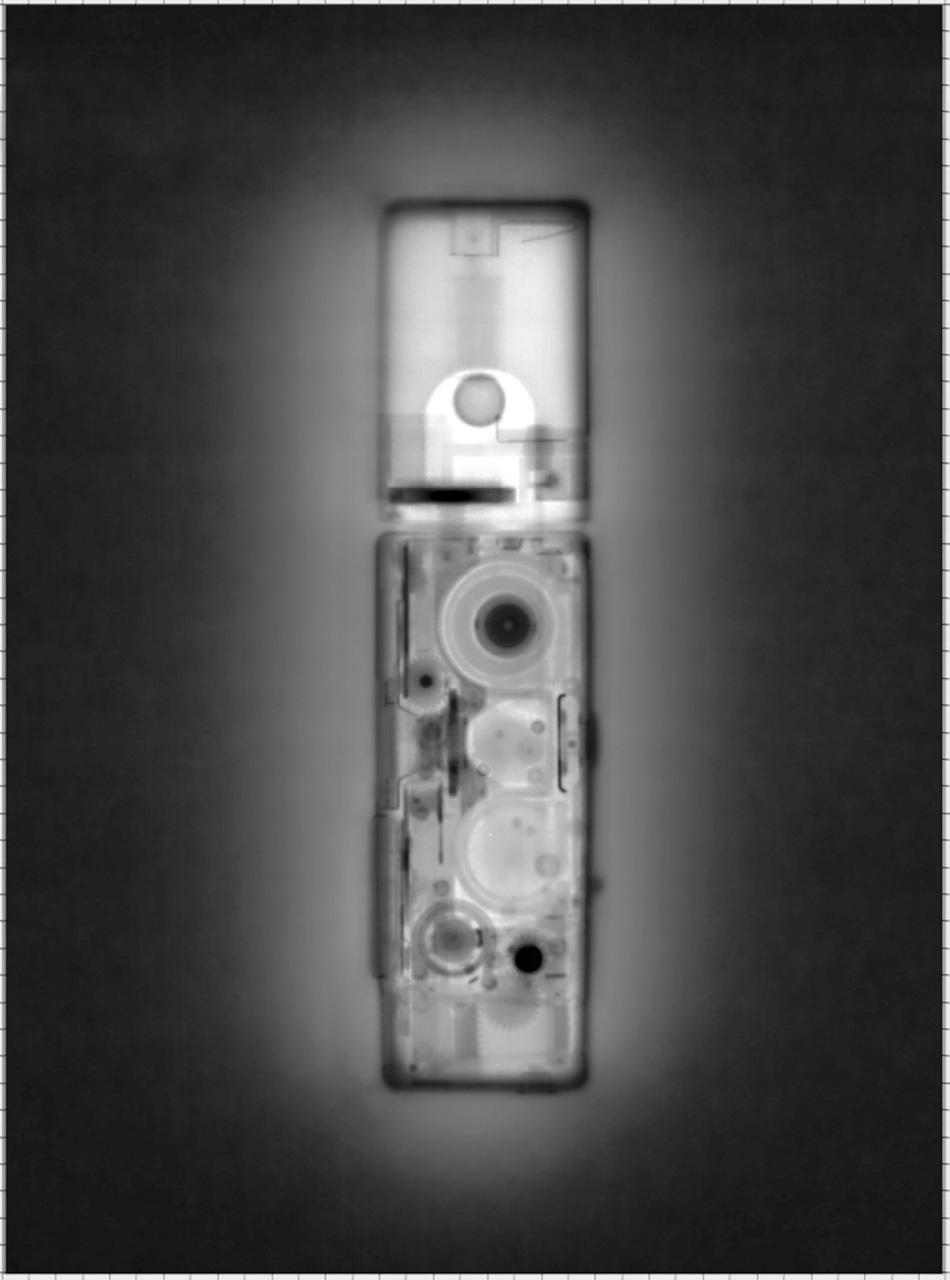

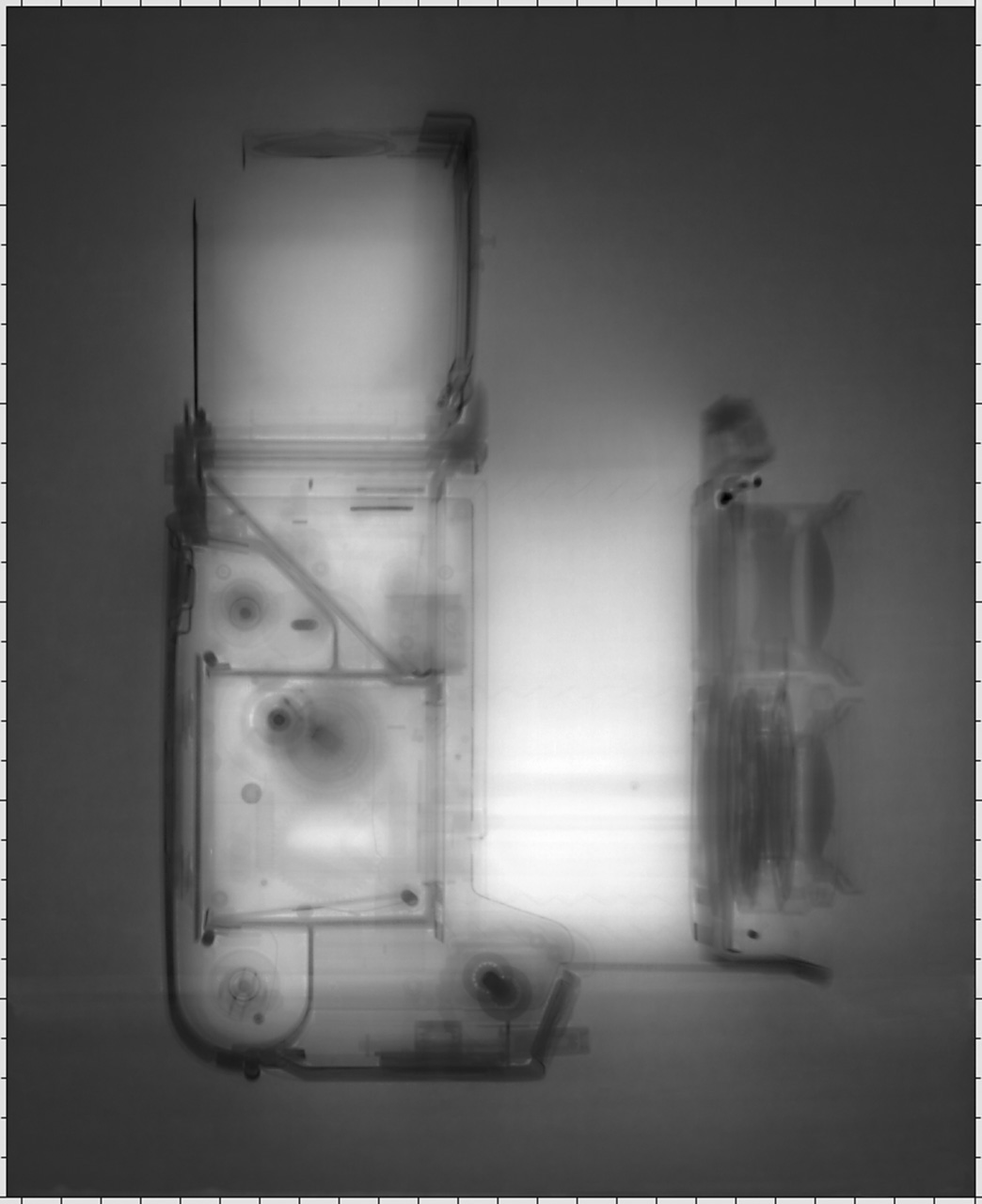

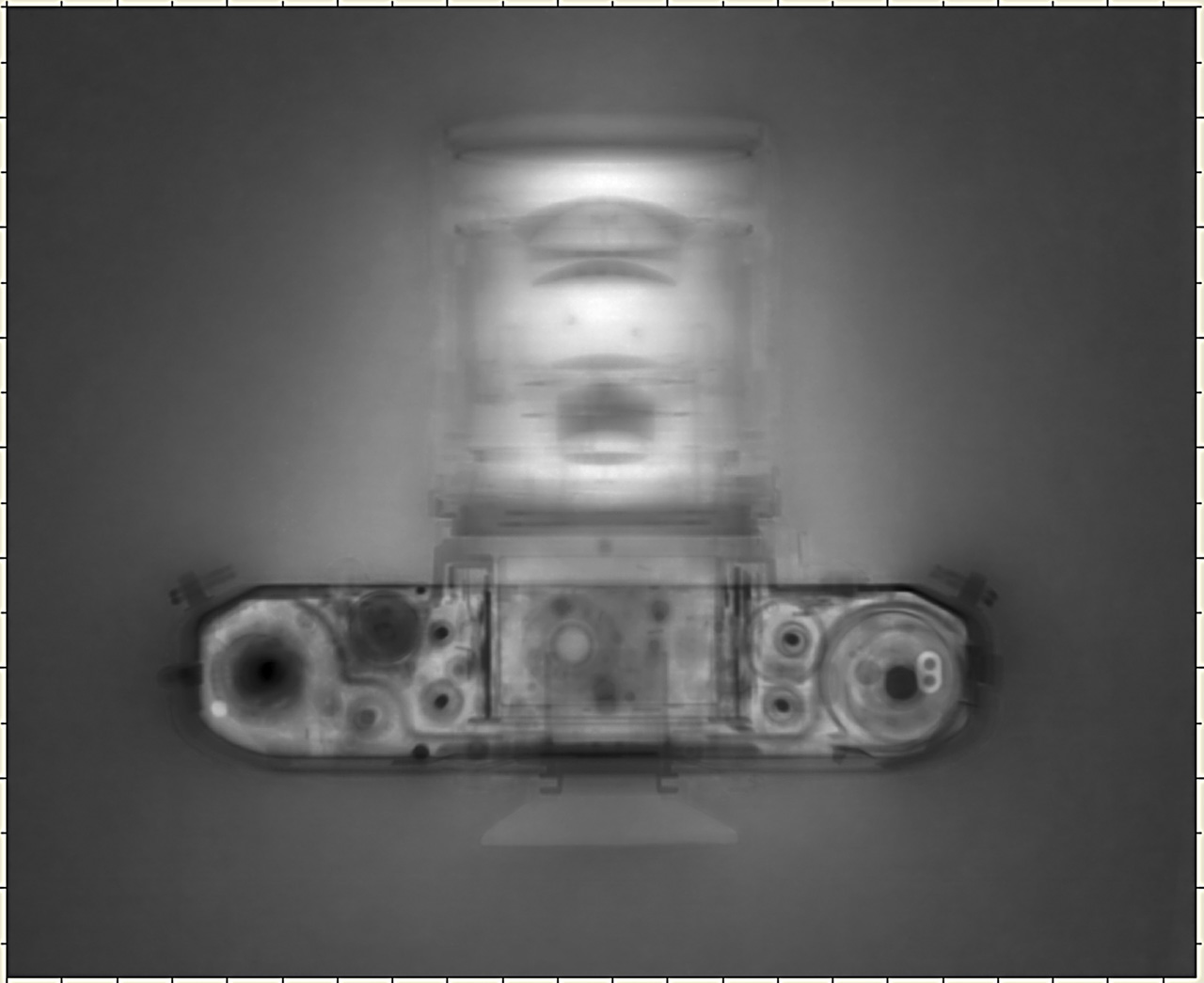

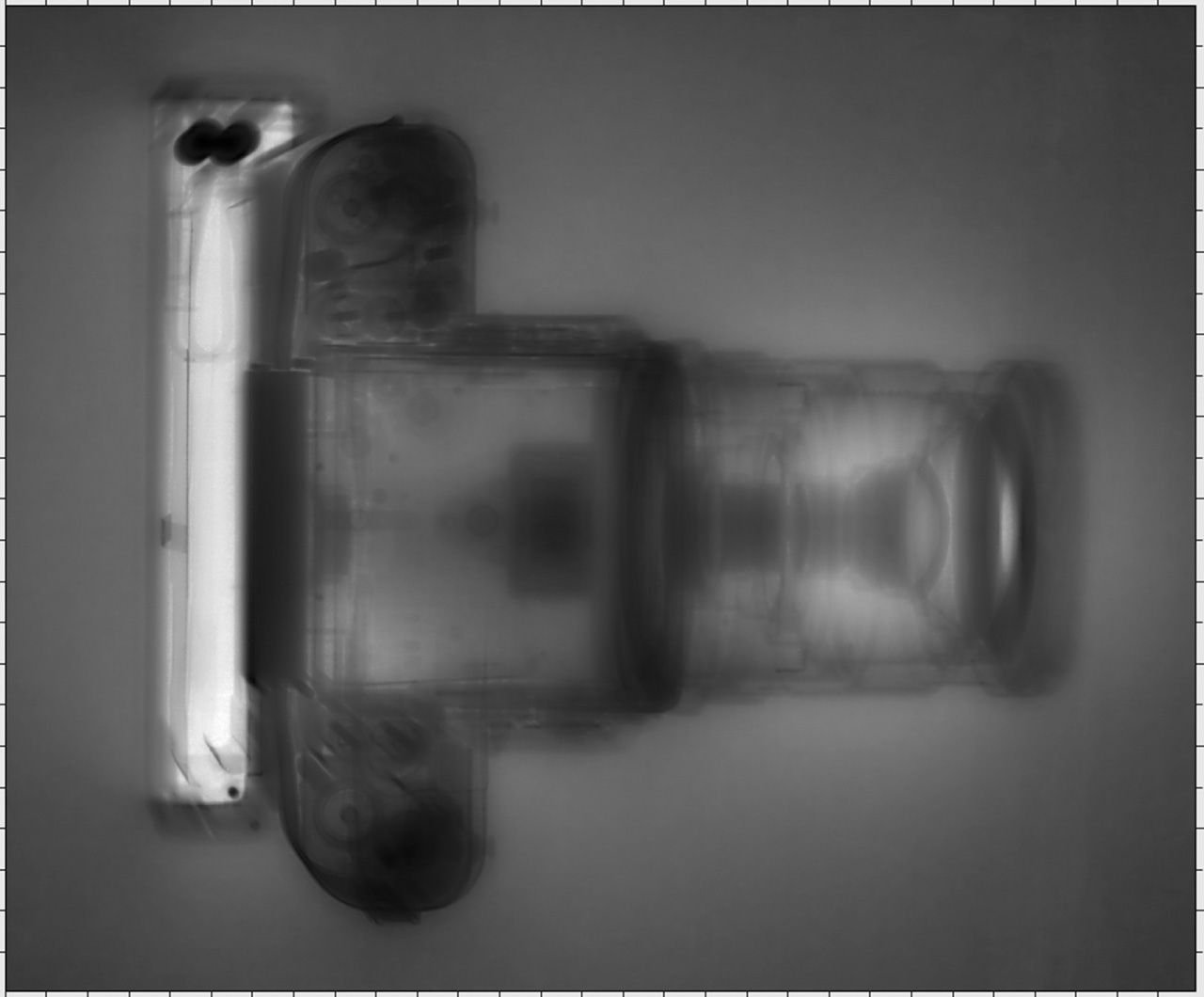

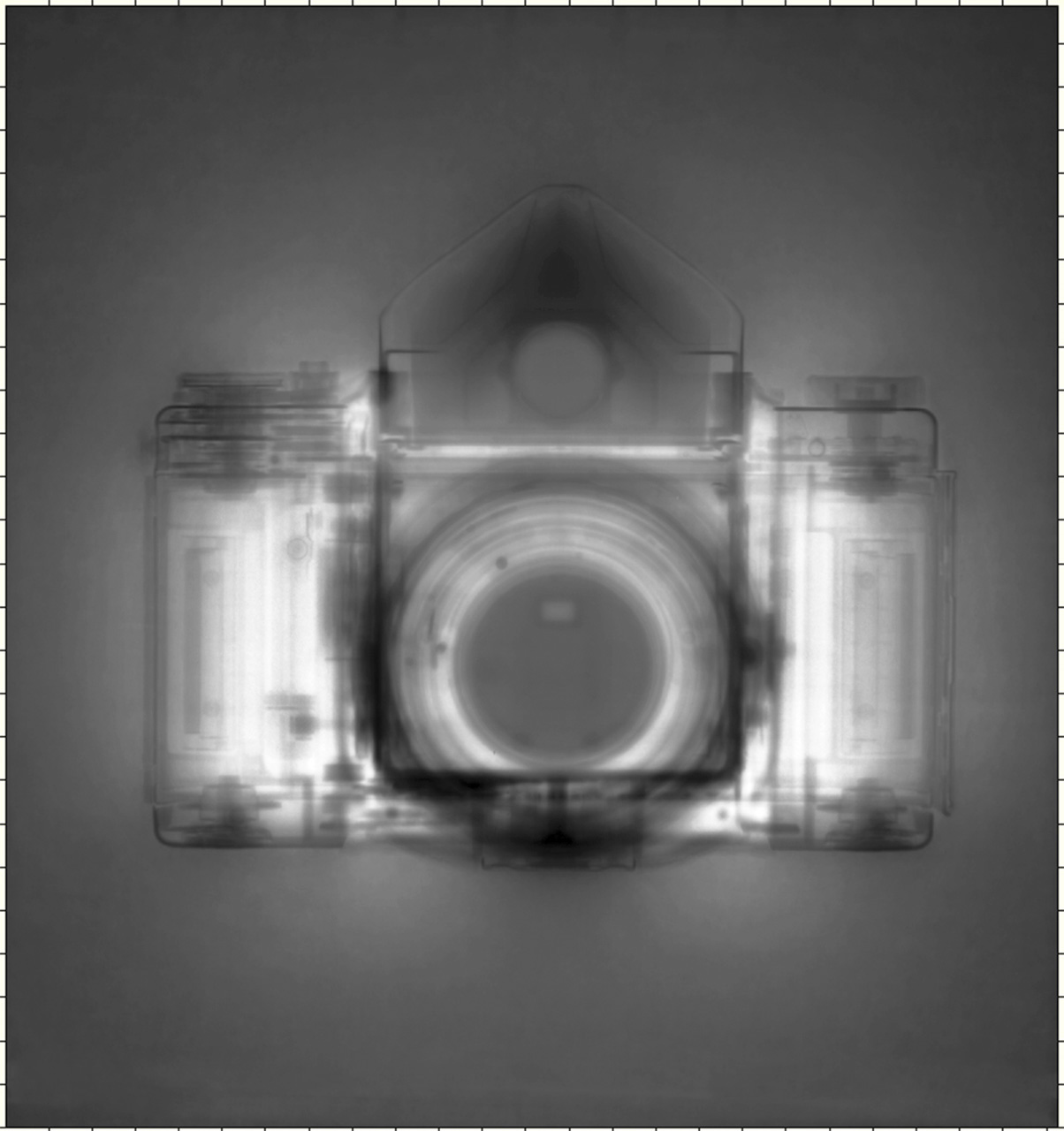

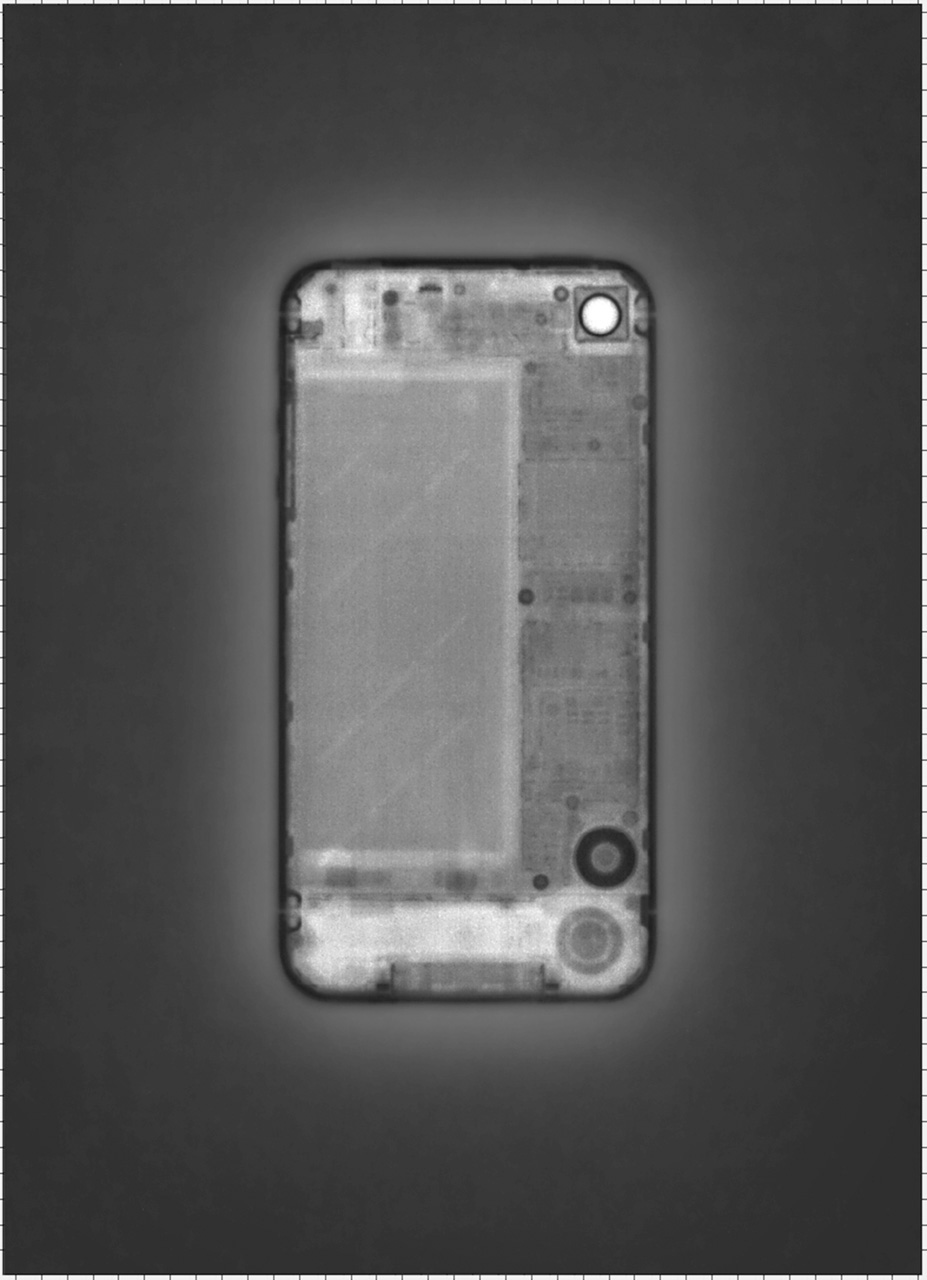

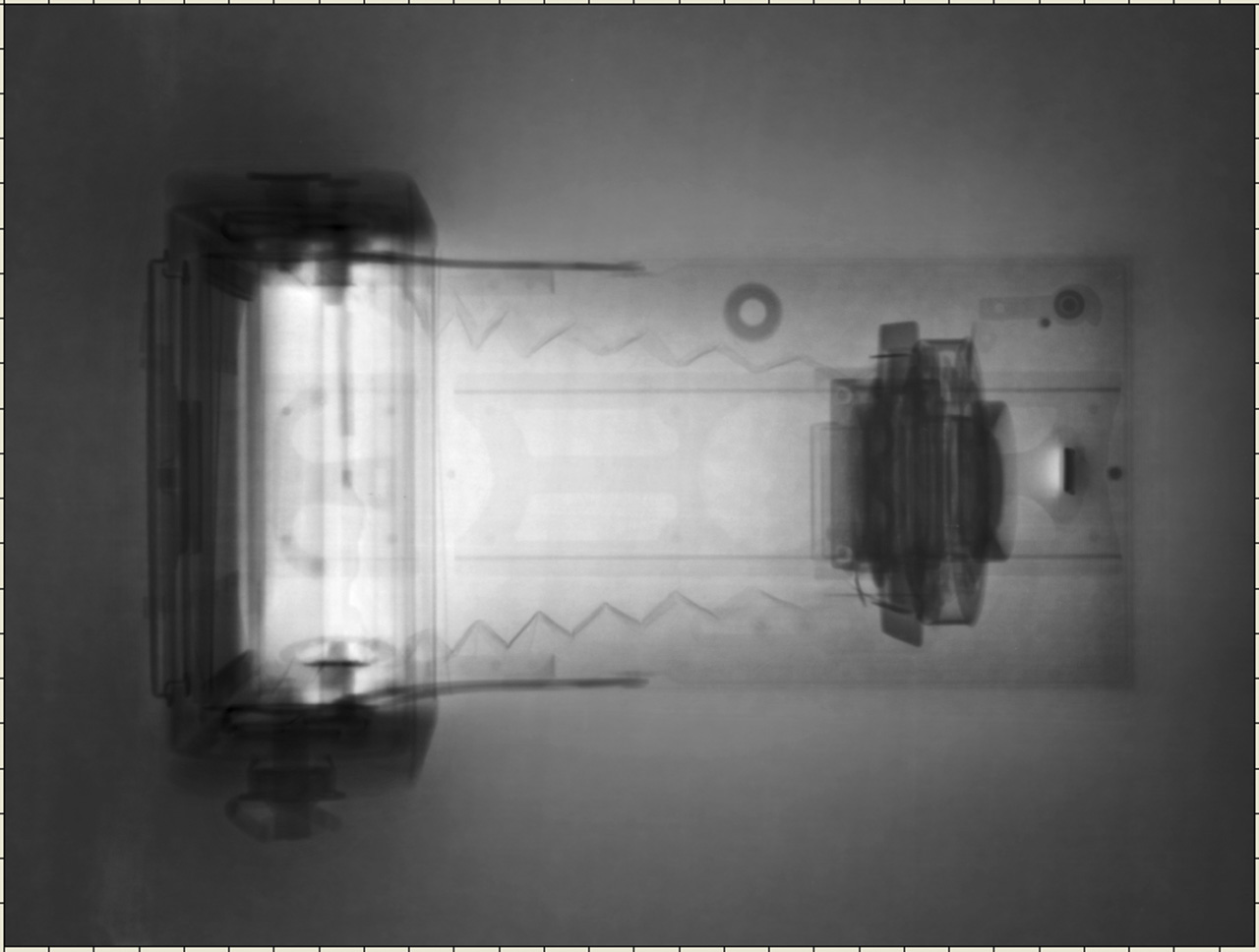

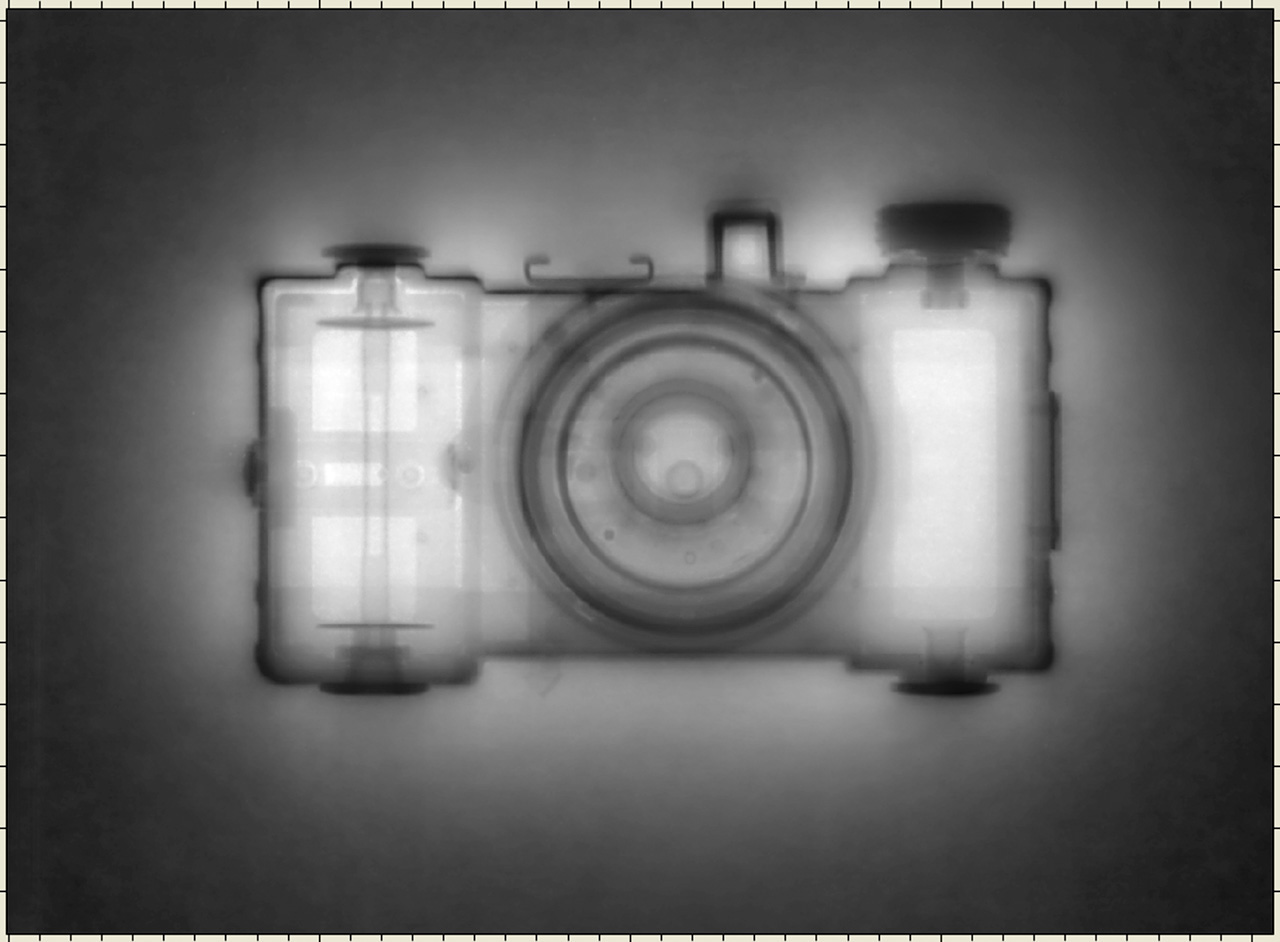

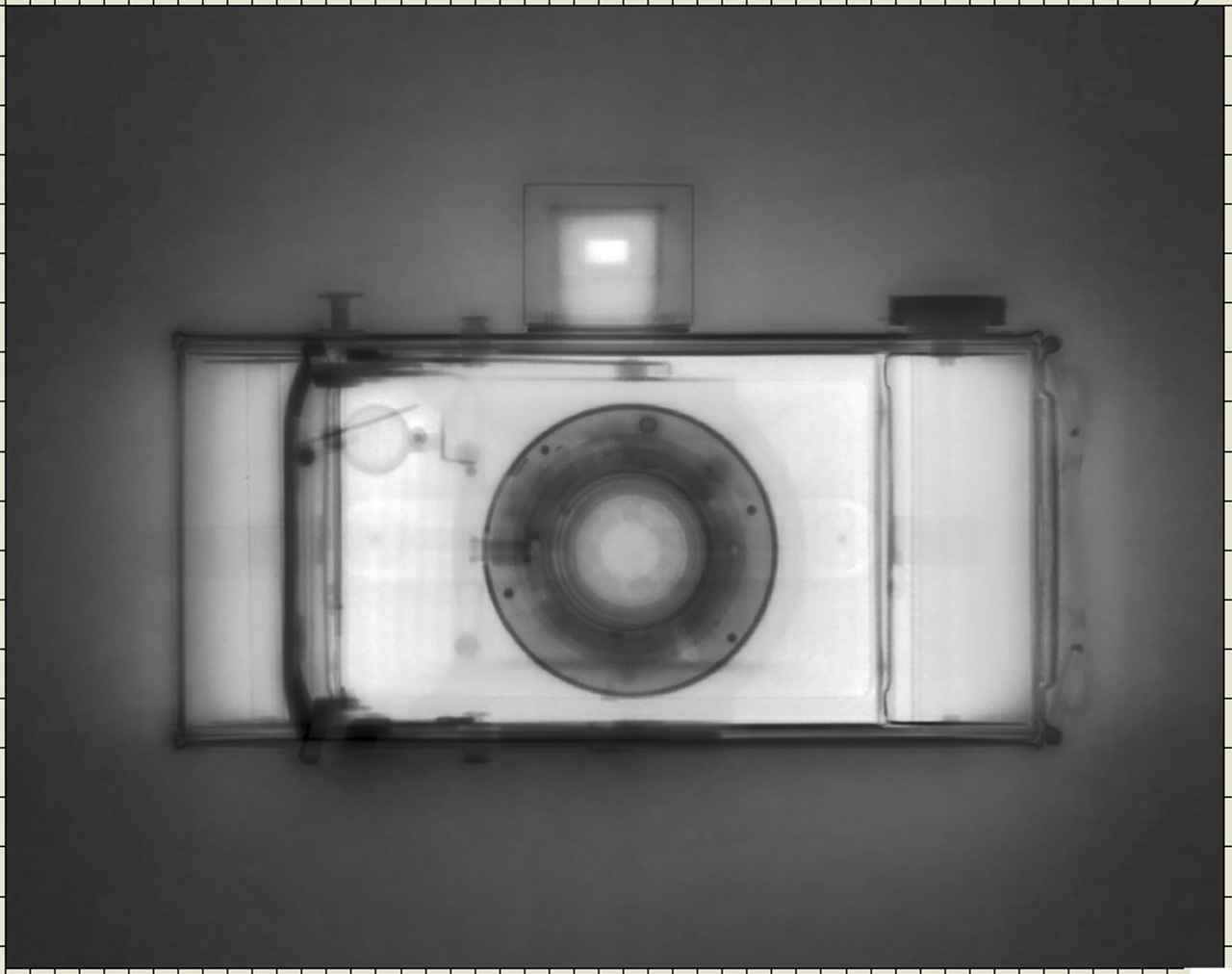

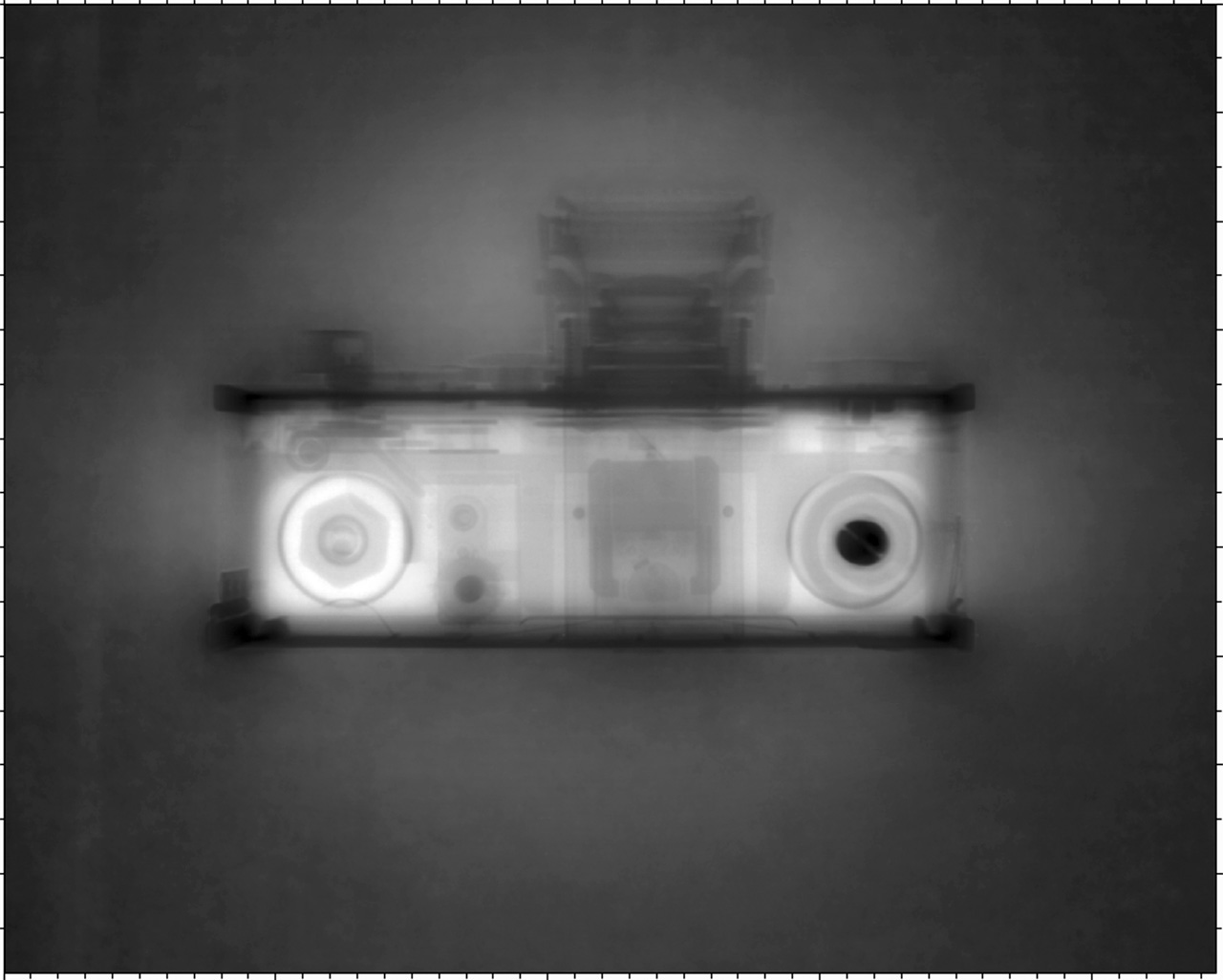

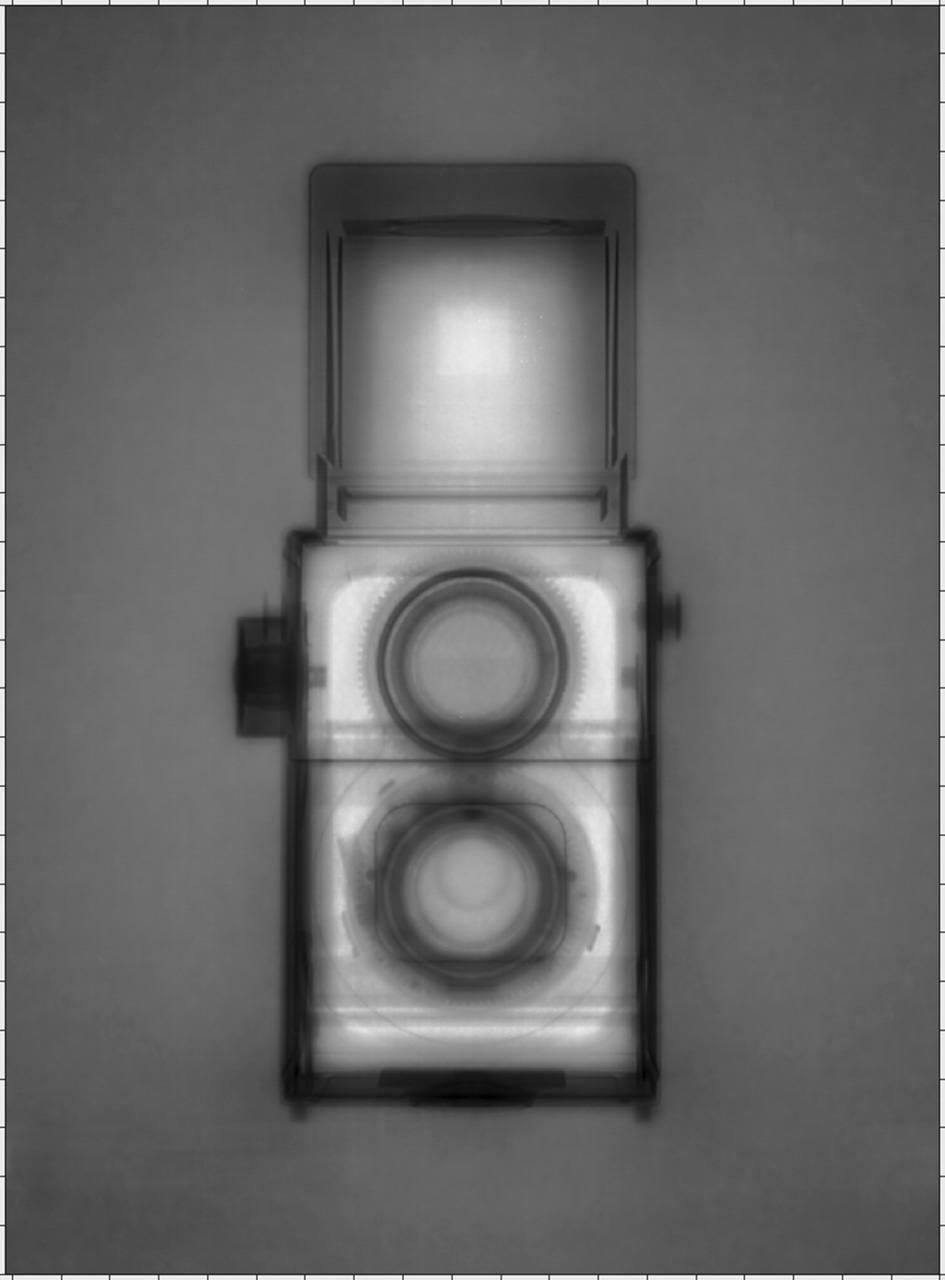

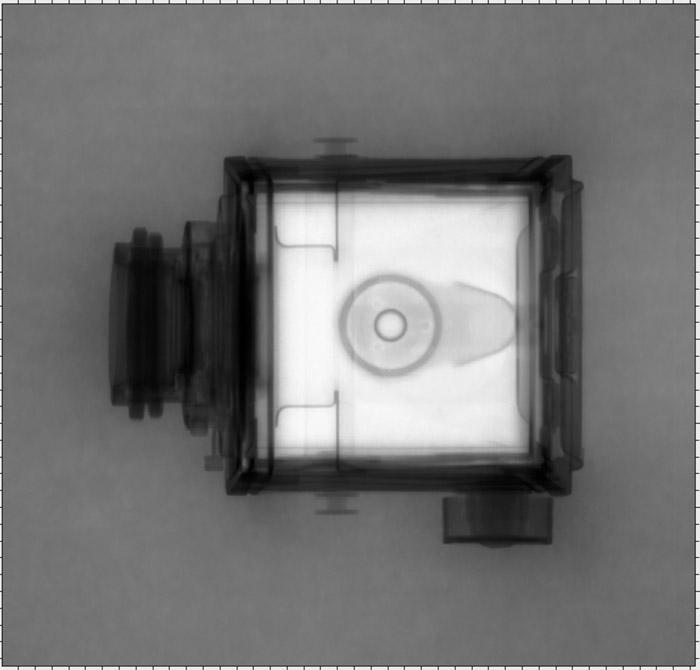

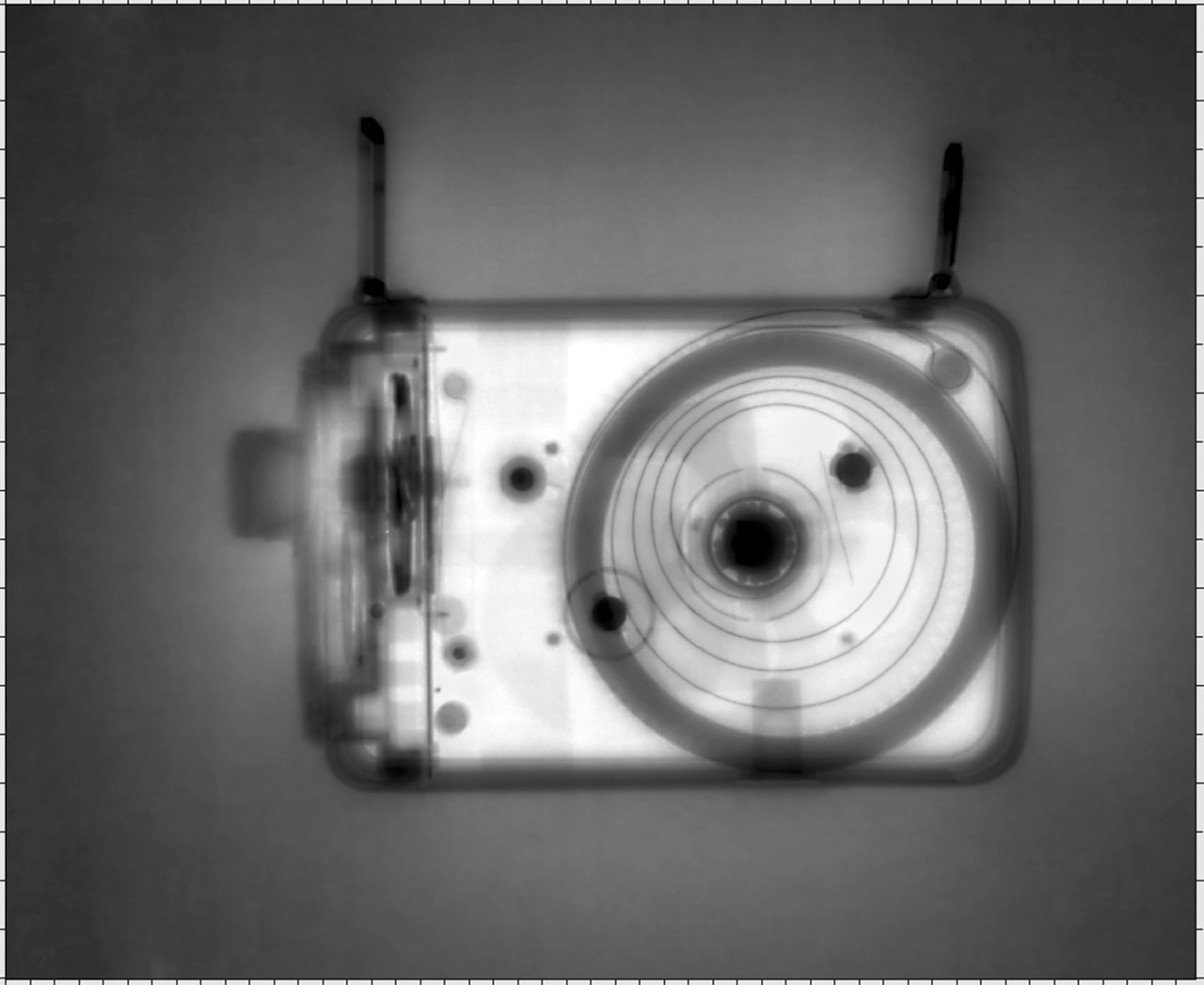

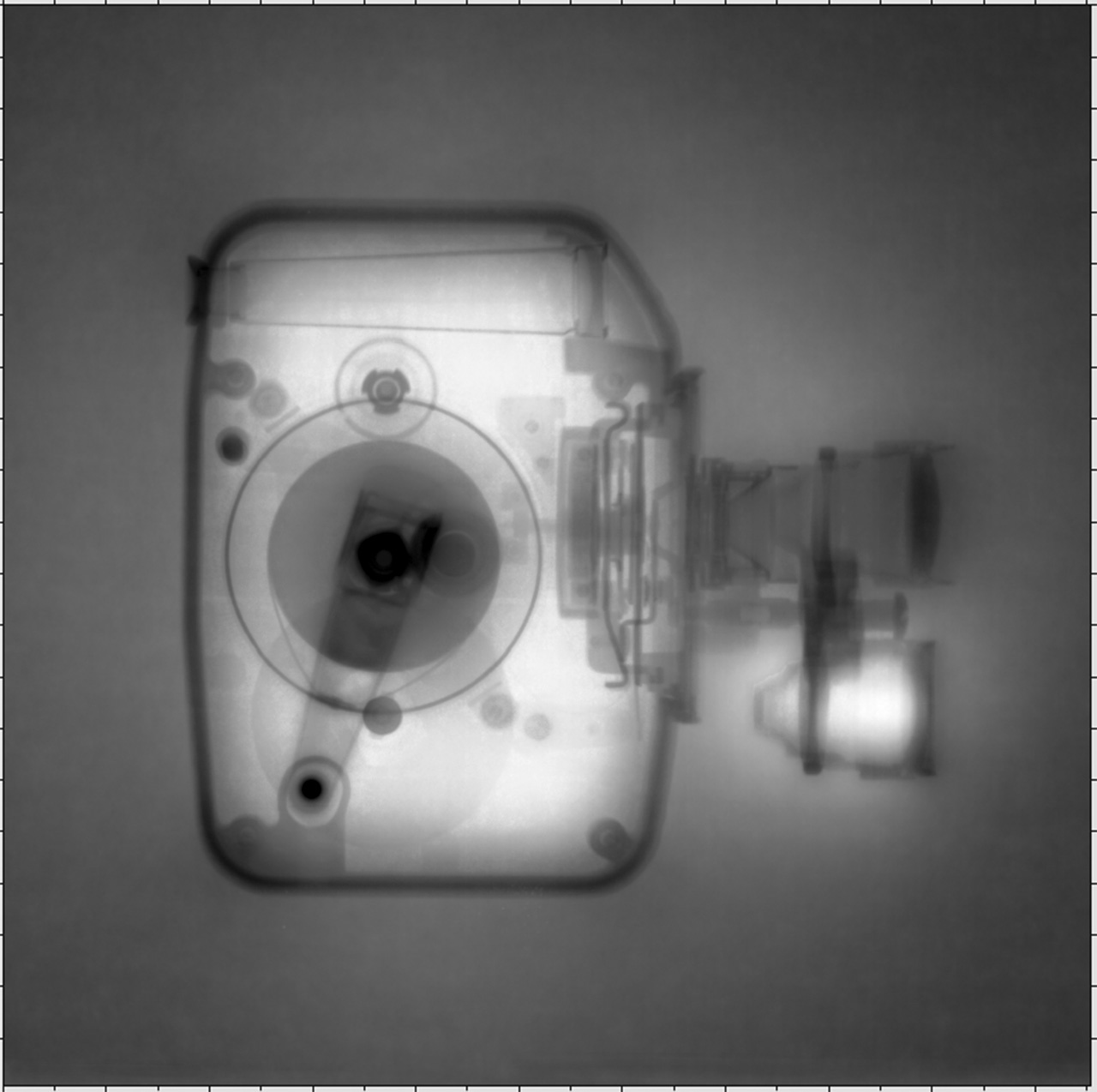

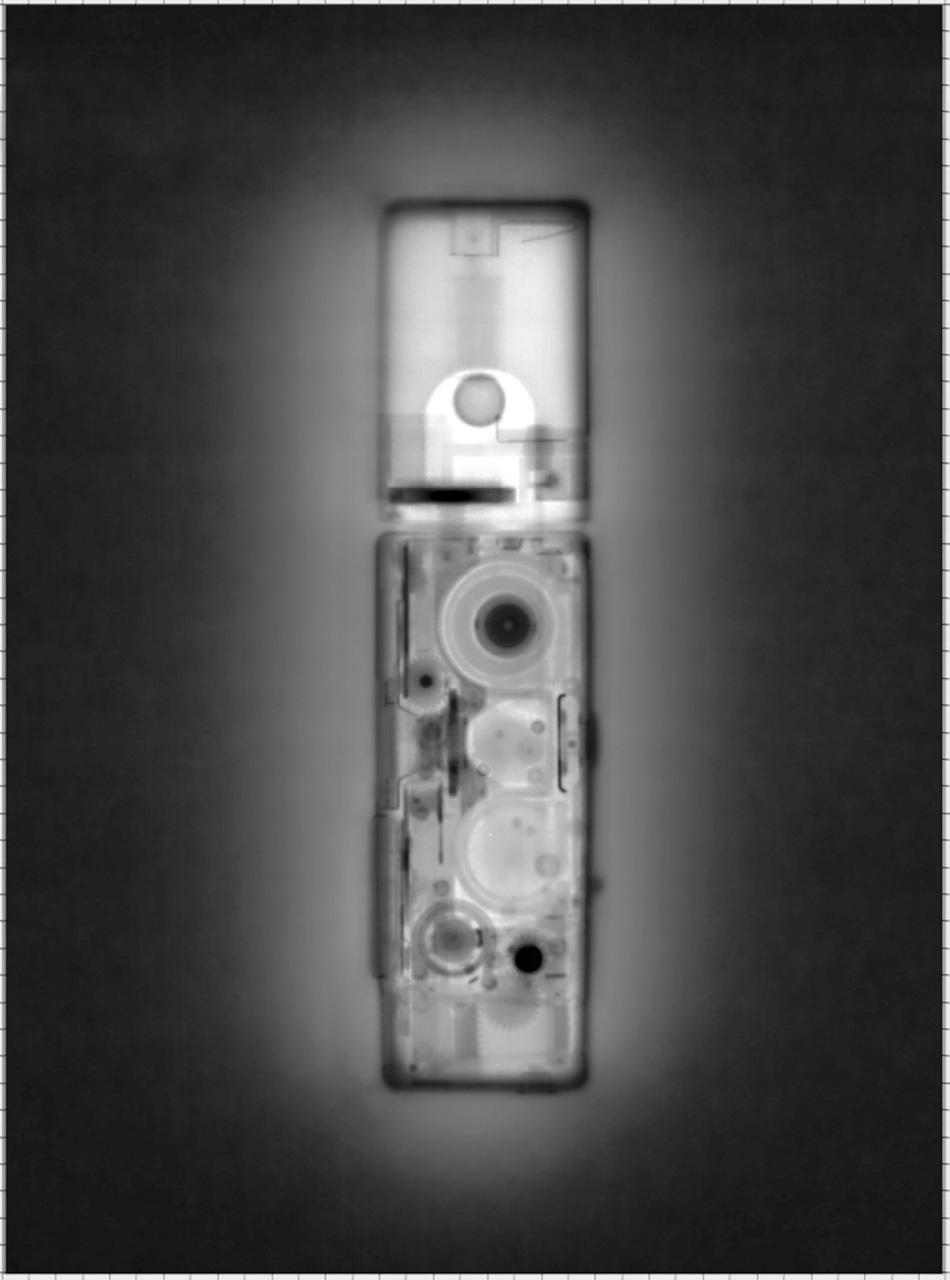

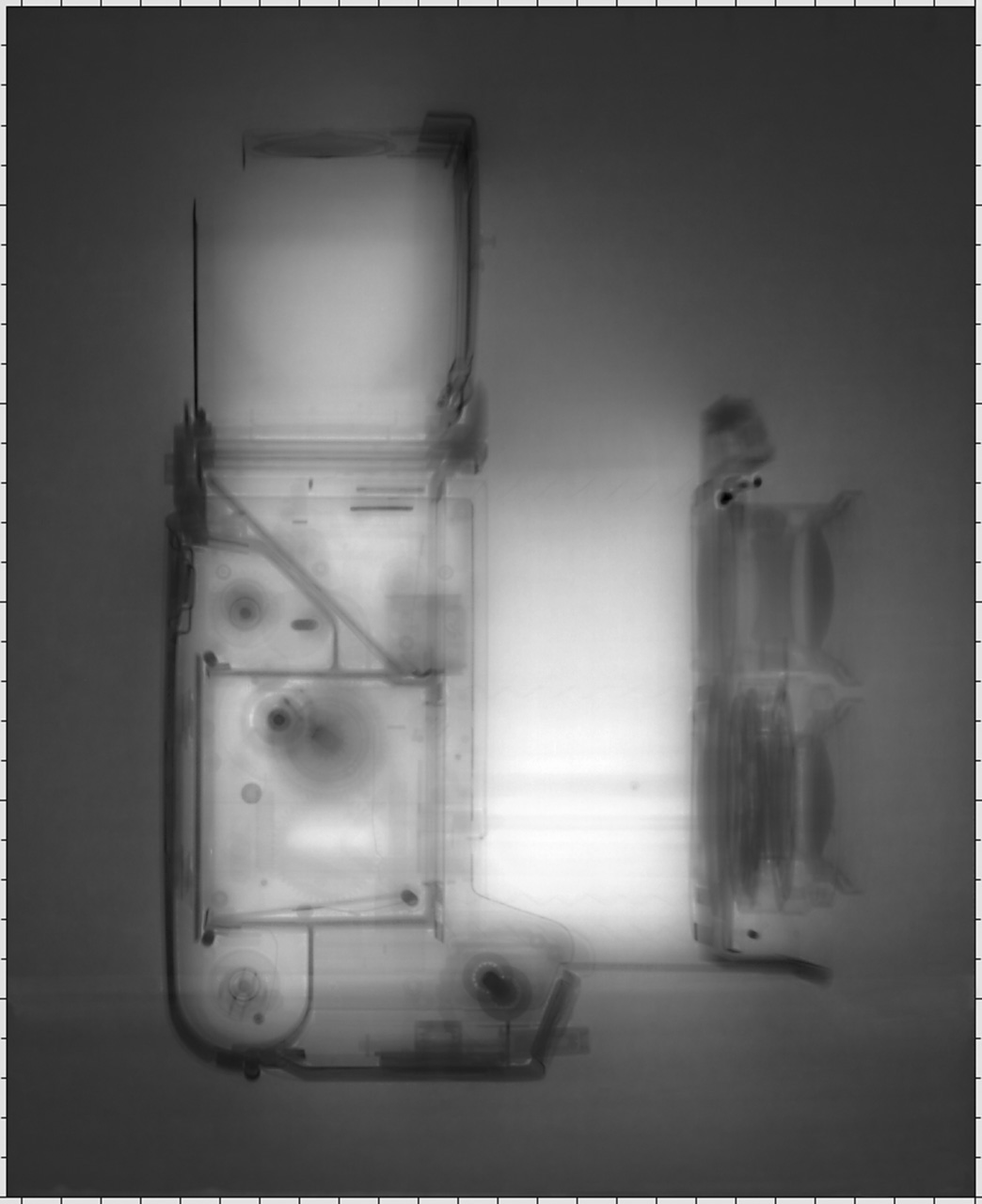

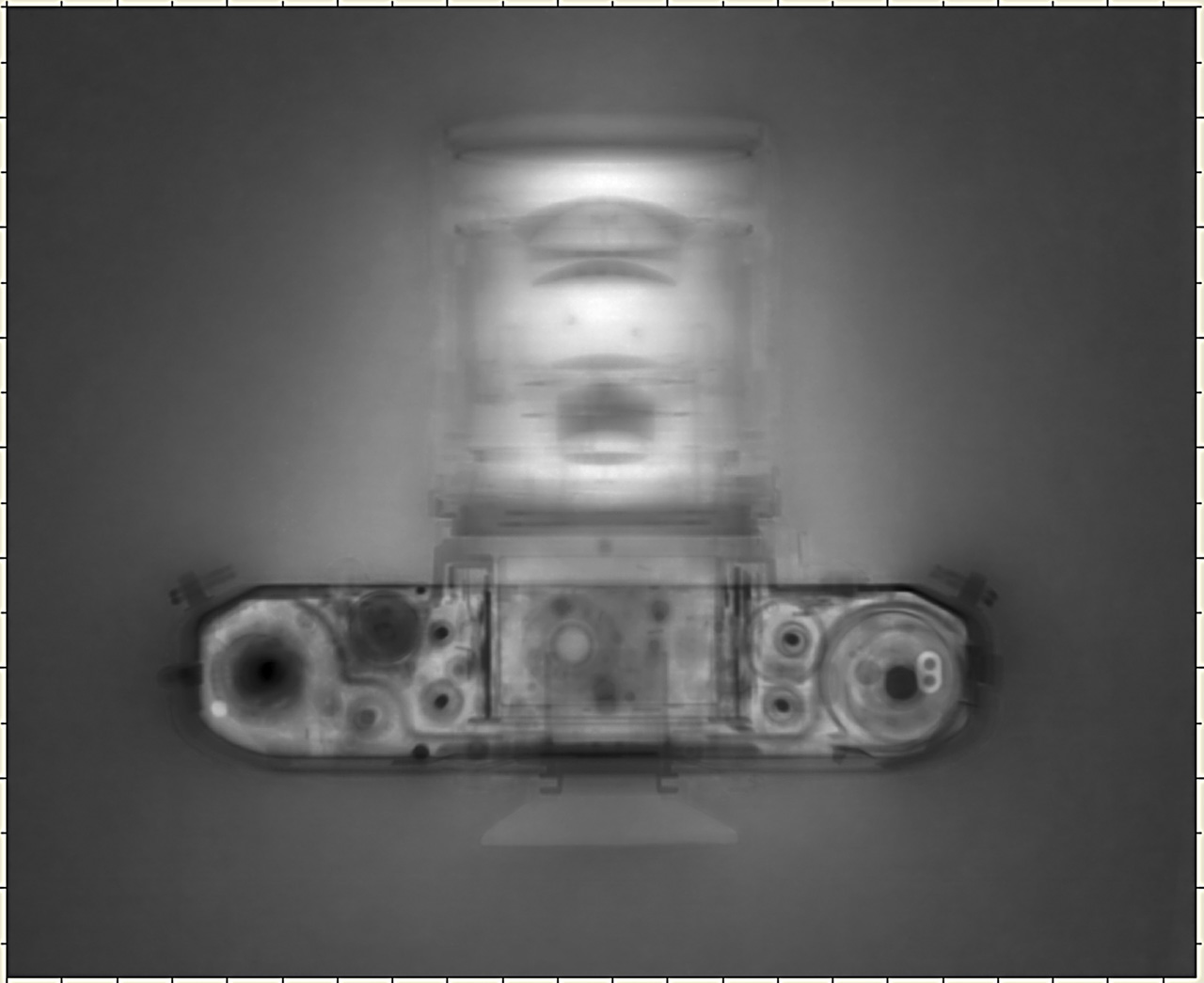

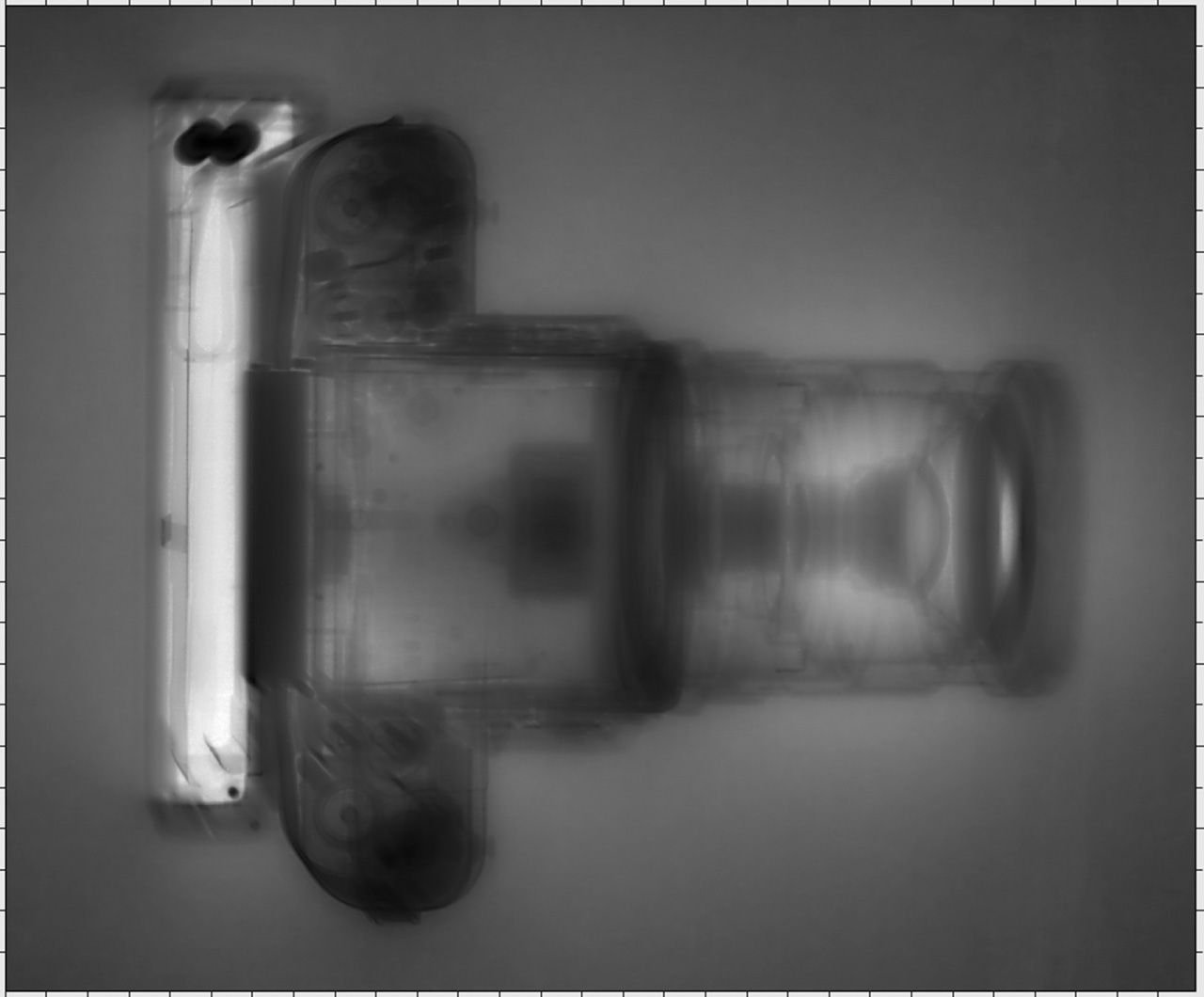

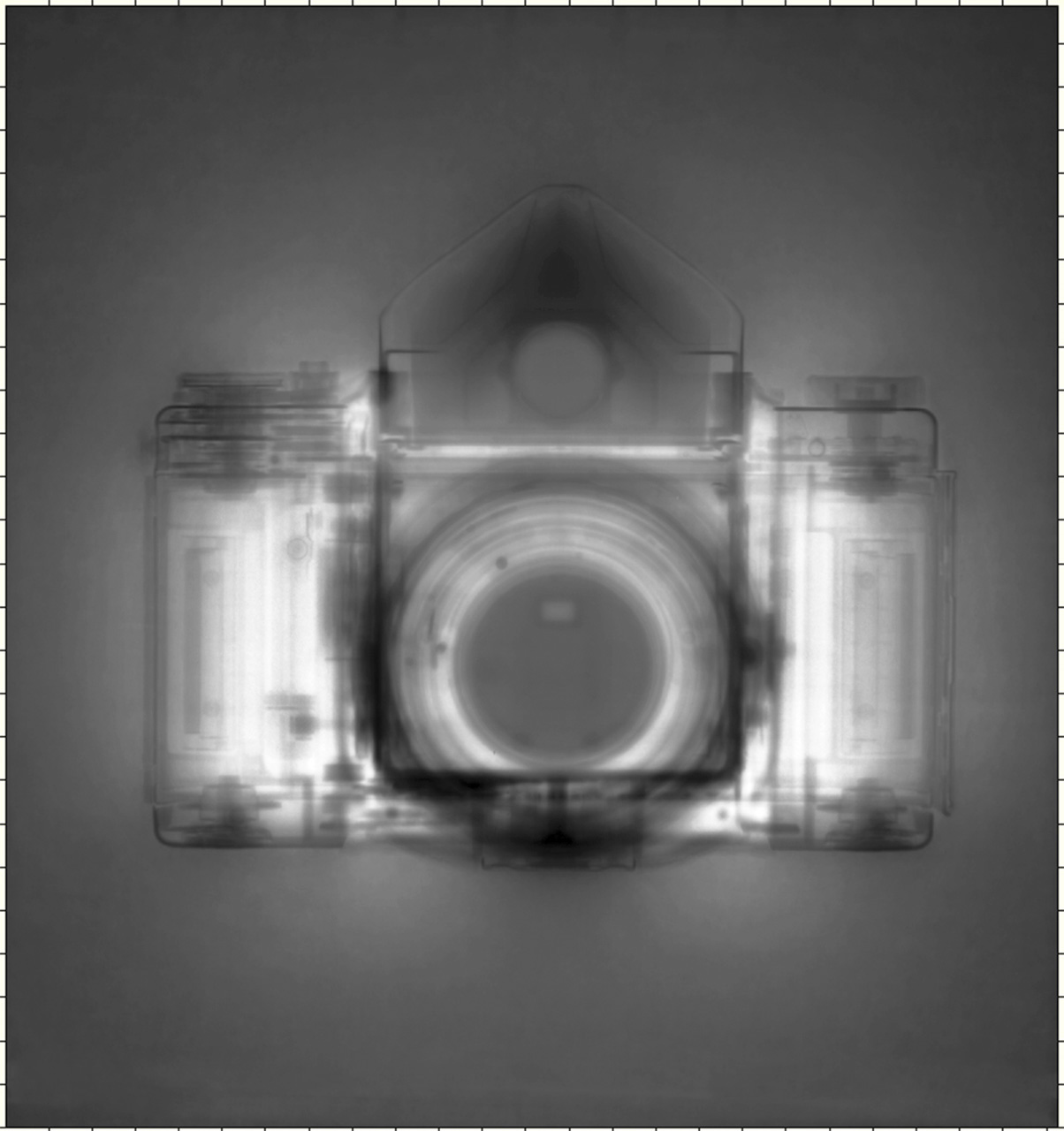

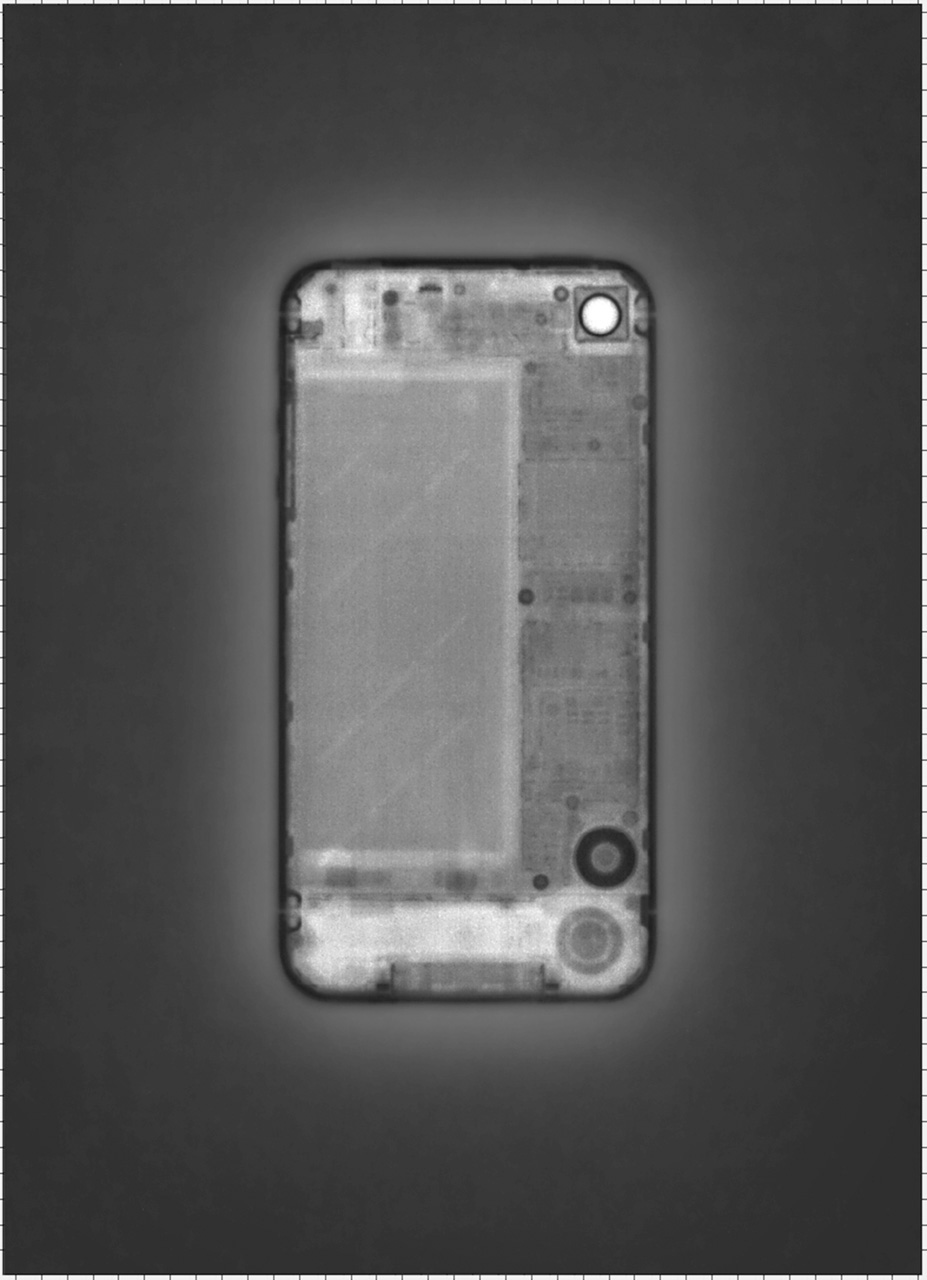

This body of work, using linear accelerator x-rays of cameras, explores the micro-evolution of cameras over time. While form and media may have changed, the camera is still a camera: a tool to create images by capturing photons of light. In a sense, it is an homage to the cameras I have used and handled. A linear accelerator produces high energy particles and x-rays and is used in physics research and health care to treat cancer patients. The resulting images align with an inner desire to probe those unseen spaces and realms I sense exist, but do not observe with my eyes.

Kent Krugh is a fine art photographer, living and working in Greater Cincinnati, OH. Ten years ago he decided to dedicate himself to photography. He has received numerous awards in national and international competitions and was a Photolucida 2012 and 2014 Critical Mass Finalist.. His work has been exhibited in national and international group and solo venues. He also taught workshops in collaboration with Colegiatura Colombiana del Diseño, Fundación Universitaria de Bellas Artes and Centro Colombo Americano under the auspices of the Universidad de Antioquia. Krugh’s work has been exhibited at three major festivals: Fringe Festival 2010, Cincinnati, OH; FotoFest Biennial 2012, Houston, TX; and FotoFocus Biennial 2012, Cincinnati, OH. Krugh's work can be found in numerous private collections and museums including the Portland Art Museum and the Cleveland Museum of Art.

Kent Krugh is a fine art photographer, living and working in Greater Cincinnati, OH. Ten years ago he decided to dedicate himself to photography. He has received numerous awards in national and international competitions and was a Photolucida 2012 and 2014 Critical Mass Finalist.. His work has been exhibited in national and international group and solo venues. He also taught workshops in collaboration with Colegiatura Colombiana del Diseño, Fundación Universitaria de Bellas Artes and Centro Colombo Americano under the auspices of the Universidad de Antioquia. Krugh’s work has been exhibited at three major festivals: Fringe Festival 2010, Cincinnati, OH; FotoFest Biennial 2012, Houston, TX; and FotoFocus Biennial 2012, Cincinnati, OH. Krugh's work can be found in numerous private collections and museums including the Portland Art Museum and the Cleveland Museum of Art.[core_state] => 1 [core_access] => 1 [core_metadata] => {"robots":"","author":"Kent Krugh","rights":"","xreference":""} [core_created_user_id] => 838 [core_created_by_alias] => [core_created_time] => 2015-02-10 21:22:20 [core_images] => {"image_intro":"images\/categories\/open-content\/krugh.jpg","float_intro":"","image_intro_alt":"","image_intro_caption":"","image_fulltext":"images\/categories\/open-content\/krugh.jpg","float_fulltext":"","image_fulltext_alt":"","image_fulltext_caption":""} [core_modified_time] => 2016-06-22 18:25:45 [core_language] => en-GB [core_catid] => 37 [core_publish_up] => 2015-02-10 21:22:20 [core_publish_down] => 0000-00-00 00:00:00 [content_type_title] => Article [router] => ContentHelperRoute::getArticleRoute [author] => Elisa Rugo [author_email] => elisa@zonezero.com [link] => index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=248:speciation&catid=37&lang=en-GB [displayDate] => 2015-02-10 21:22:20 [event] => stdClass Object ( [afterDisplayTitle] => [beforeDisplayContent] => [afterDisplayContent] => ) [text] =>

This body of work, using linear accelerator x-rays of cameras, explores the micro-evolution of cameras over time. While form and media may have changed, the camera is still a camera: a tool to create images by capturing photons of light. In a sense, it is an homage to the cameras I have used and handled. A linear accelerator produces high energy particles and x-rays and is used in physics research and health care to treat cancer patients. The resulting images align with an inner desire to probe those unseen spaces and realms I sense exist, but do not observe with my eyes.

Kent Krugh is a fine art photographer, living and working in Greater Cincinnati, OH. Ten years ago he decided to dedicate himself to photography. He has received numerous awards in national and international competitions and was a Photolucida 2012 and 2014 Critical Mass Finalist.. His work has been exhibited in national and international group and solo venues. He also taught workshops in collaboration with Colegiatura Colombiana del Diseño, Fundación Universitaria de Bellas Artes and Centro Colombo Americano under the auspices of the Universidad de Antioquia. Krugh’s work has been exhibited at three major festivals: Fringe Festival 2010, Cincinnati, OH; FotoFest Biennial 2012, Houston, TX; and FotoFocus Biennial 2012, Cincinnati, OH. Krugh's work can be found in numerous private collections and museums including the Portland Art Museum and the Cleveland Museum of Art.

Kent Krugh is a fine art photographer, living and working in Greater Cincinnati, OH. Ten years ago he decided to dedicate himself to photography. He has received numerous awards in national and international competitions and was a Photolucida 2012 and 2014 Critical Mass Finalist.. His work has been exhibited in national and international group and solo venues. He also taught workshops in collaboration with Colegiatura Colombiana del Diseño, Fundación Universitaria de Bellas Artes and Centro Colombo Americano under the auspices of the Universidad de Antioquia. Krugh’s work has been exhibited at three major festivals: Fringe Festival 2010, Cincinnati, OH; FotoFest Biennial 2012, Houston, TX; and FotoFocus Biennial 2012, Cincinnati, OH. Krugh's work can be found in numerous private collections and museums including the Portland Art Museum and the Cleveland Museum of Art.[id] => 248 [language] => en-GB [catid] => 37 [jcfields] => Array ( ) ) 1

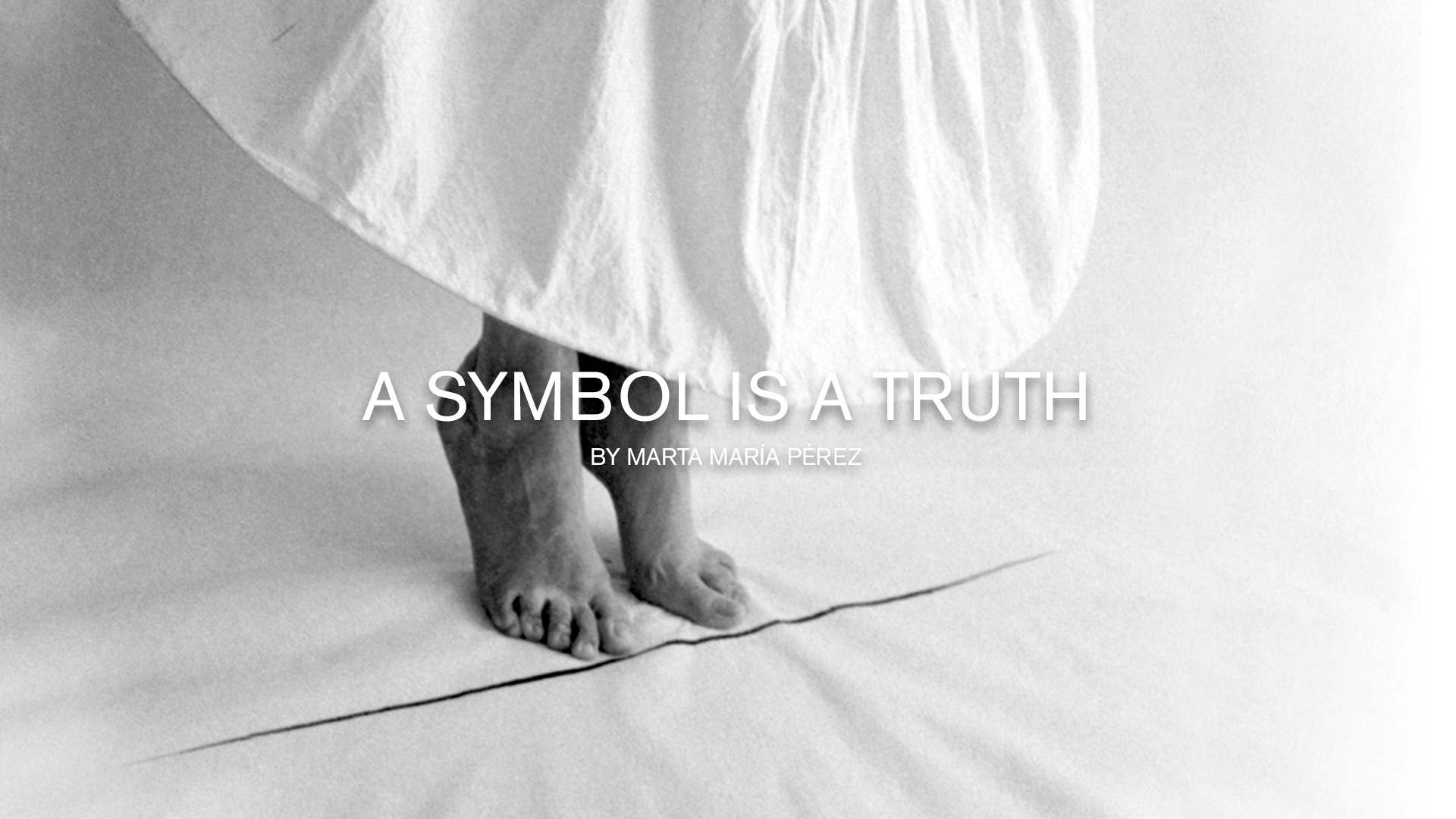

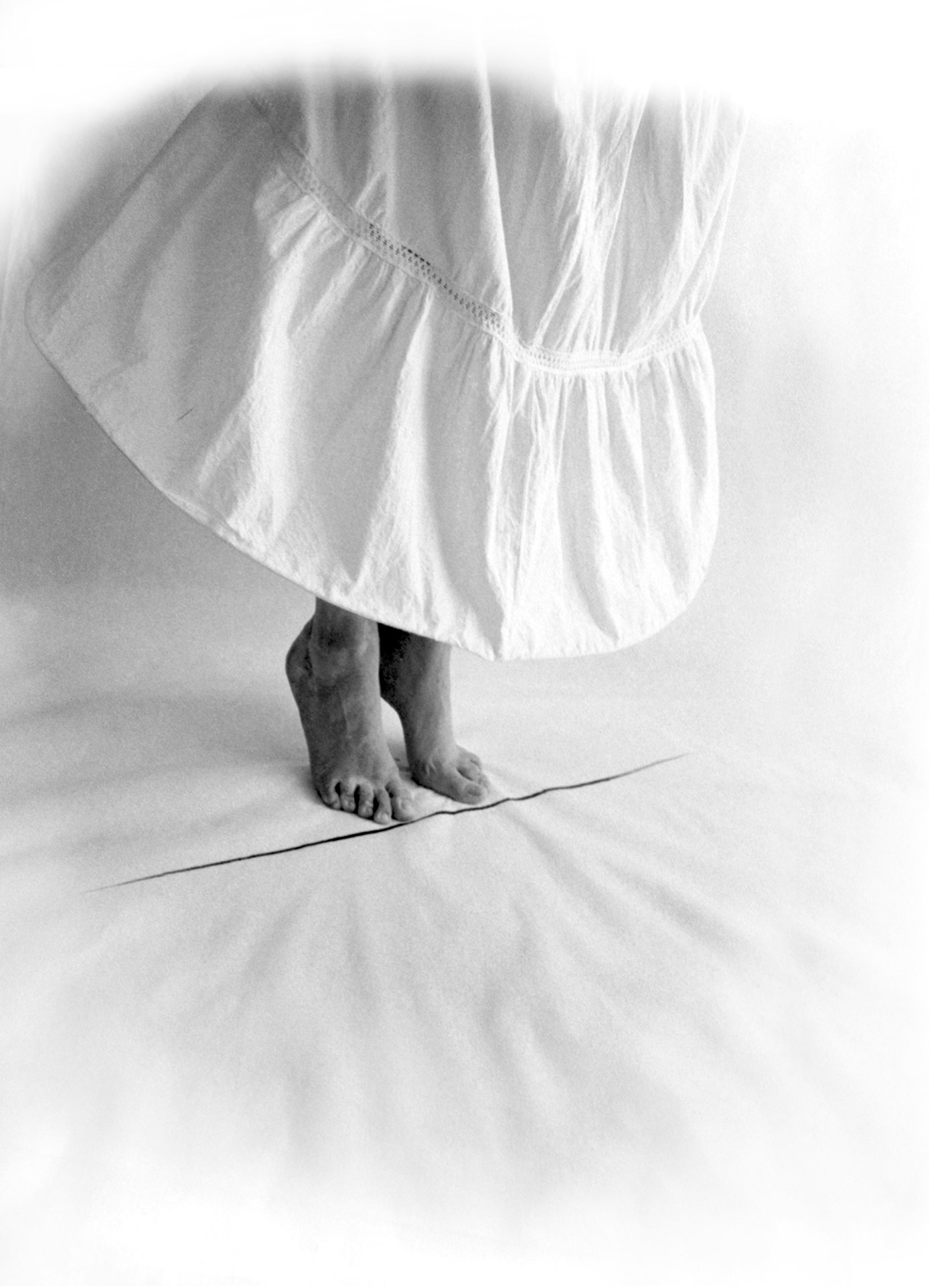

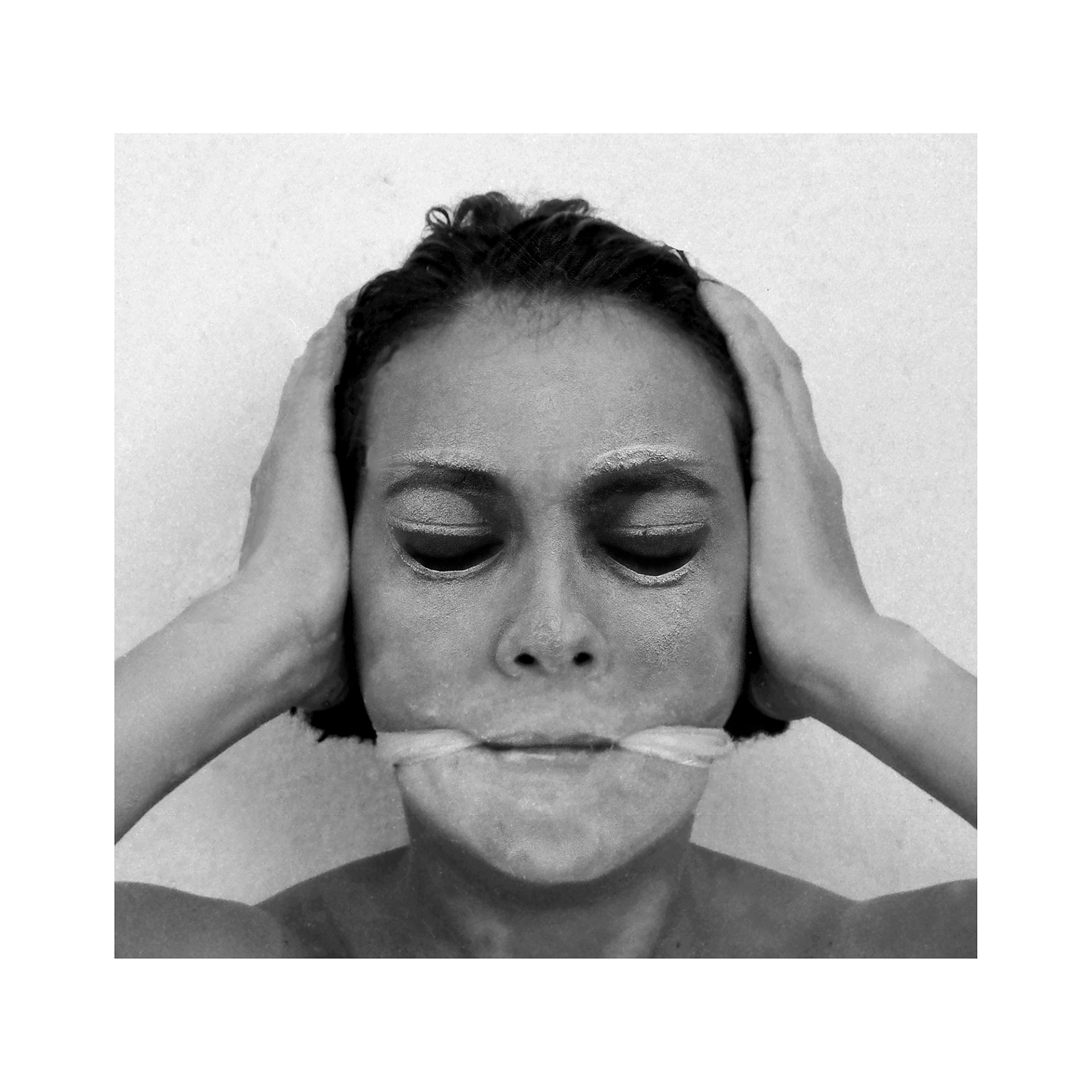

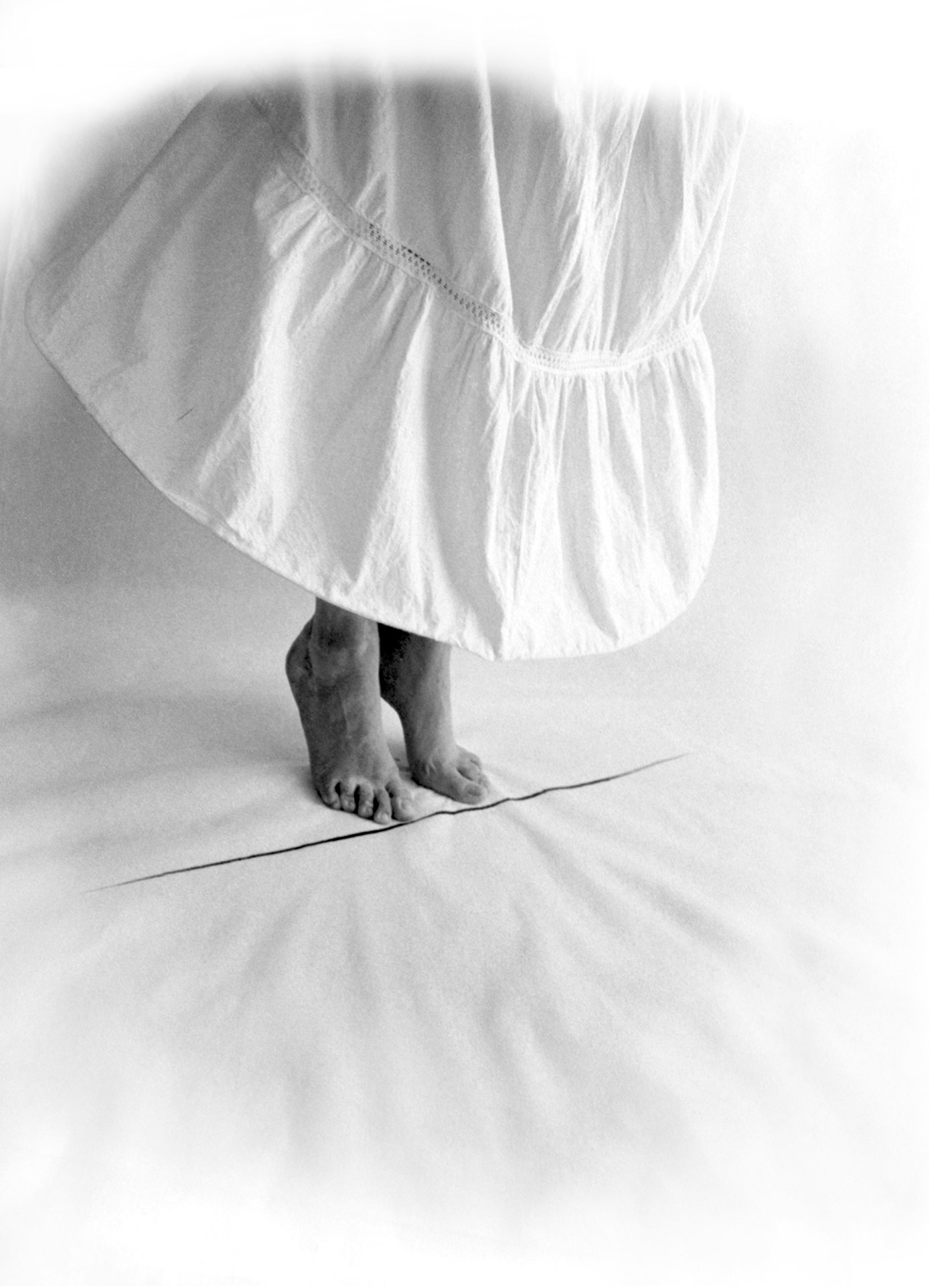

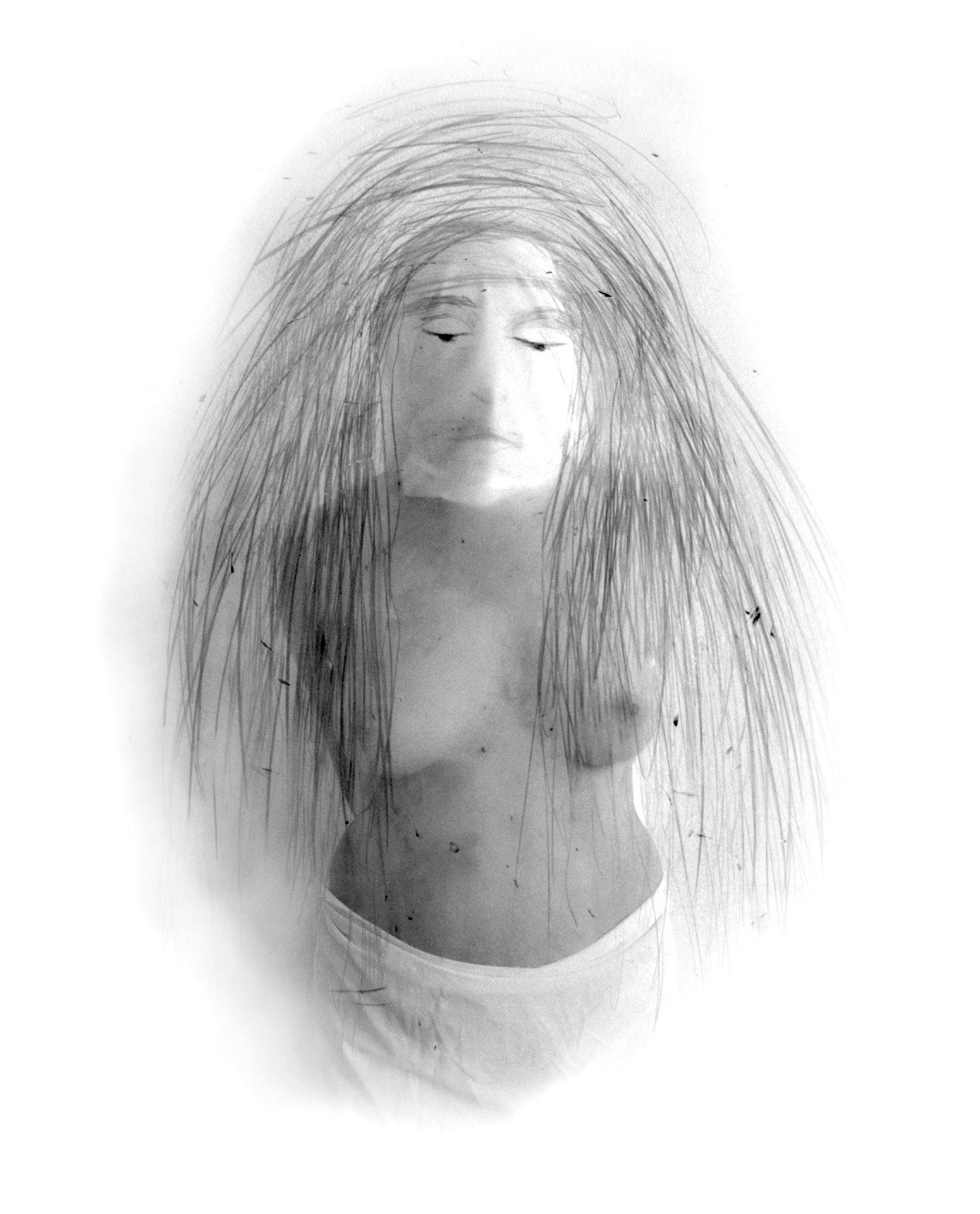

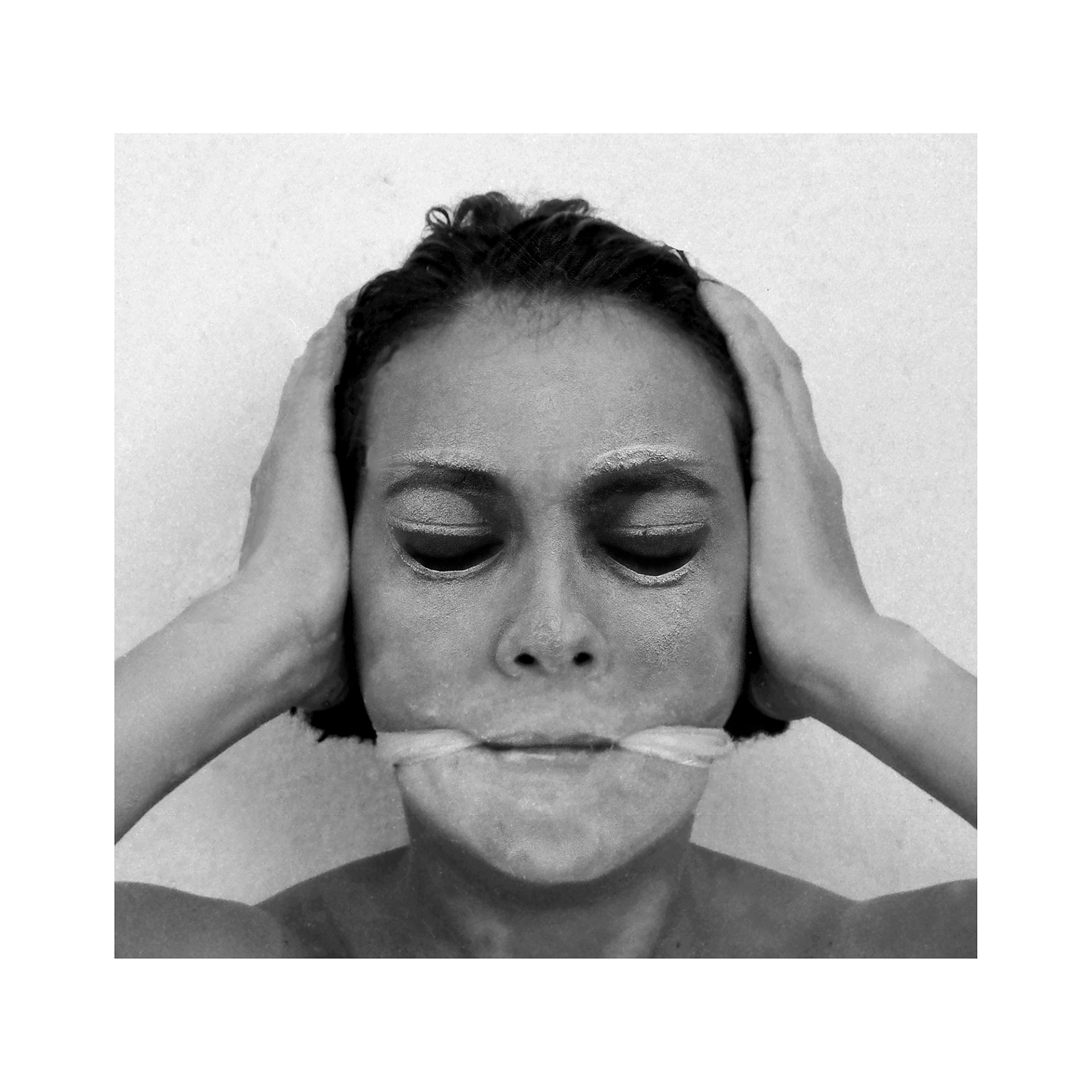

Marta María Pérez

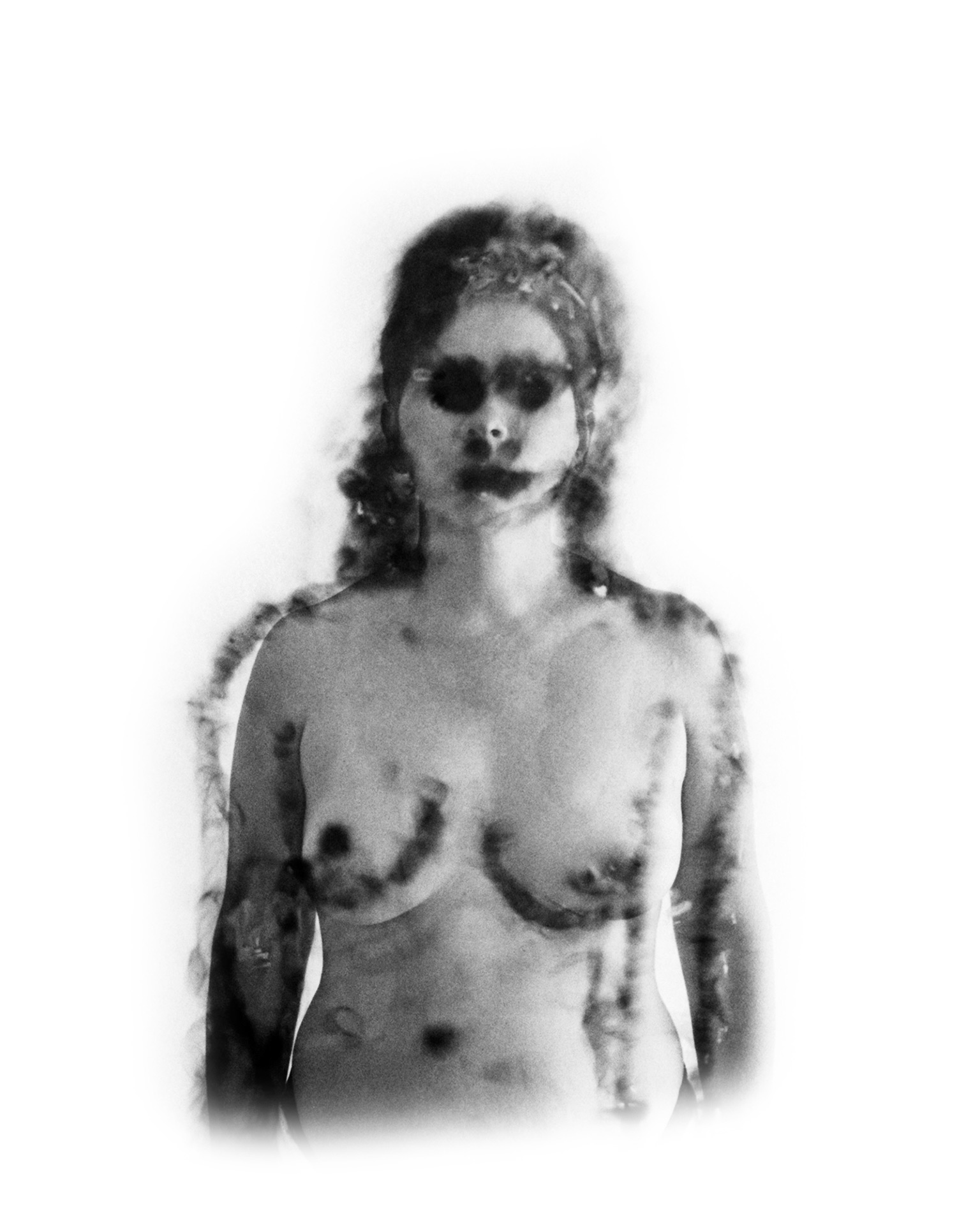

During a lifetime of work, Marta Maria Perez Bravo has explored the rites and beliefs of Cuban religion through her own image. Her body sacrifices the symbol, creating an account of intersections between dualities, such as the visible and the invisible, the material and the spiritual, life after death, the presence of absence. That reiteration of opposites uses its own aesthetic to create narratives that, supported by the photographic document, build a universe of re-creations of rites and ceremonial objects.

Currently, her artistic proposal has led her to use other visual mediums with which she complements and continues to investigate her conceptual interests.

Marta María Pérez Bravo (Cuba, 1959). Lives and works in Mexico. Photographer. She began her studies as an artist in 1979 at the School of Visual Arts San Alejandro, Havana, Cuba. In 1984 she continued her studies at the Instituto Superior de Arte (ISA), Havana, Cuba. She has participated in numerous international solo and group exhibitions. She has won several awards for her work, such as the Guggenheim Fellowship (USA) in 1998.

Marta María Pérez Bravo (Cuba, 1959). Lives and works in Mexico. Photographer. She began her studies as an artist in 1979 at the School of Visual Arts San Alejandro, Havana, Cuba. In 1984 she continued her studies at the Instituto Superior de Arte (ISA), Havana, Cuba. She has participated in numerous international solo and group exhibitions. She has won several awards for her work, such as the Guggenheim Fellowship (USA) in 1998.ZZ. In your work, self-representation is a constant theme, ¿how did your interest in talking about various themes through your own image arise?

MM. I studied Fine Arts, but my graduate thesis, at the Instituto Superior de Arte in Havana (1984), was a photographic project, even though I never studied photography. This project consisted of photographs documenting actions that I performed outdoors, taking as its theme the popular superstitions regarding natural phenomena, appearances etc. When I was pregnant, I could no longer do these performances and I started using my own body. I started to document, in a different way, other actions related to these superstitions and popular beliefs, but now regarding my experience of motherhood. As in the first stage, these realities were constructed and ‘staged’. So, from the beginning, it was clear that using a model or another person, and not my own body would completely change the concept of the work, given that it has a strong autobiographical presence, although implicitly.

ZZ. We see that themes, like evocation and absence, are constant in your work. How have these themes continued to change throughout your career?

MM. In my work, religious themes, especially of afro-cuban origin, started to emerge. The constructed realities (constructed through the staged scenes), that are devoid of time and space, are re-creations (not recreations) of rites and ritual objects.

ZZ. What is the symbolic value of the objects in your photos? What place do you give to the objects as symbols in your photos? What does their reiterative use signify?

From the ritual objects I want to extract a meaning that goes beyond the form, though the making of these objects is done with reference to the originals and the use they are given in religious practices. Although my photography is always black and white, I use the original colors in the elaboration of these objects as a token of respect for these practices and real liturgical objects. Nevertheless, I don’t want the spectator to be distracted by these colors; I want him to focus his attention on the symbols and their meanings. Even though he might not know them at all (since they are object of separate study and profound analysis) my intention is that, when these symbols are interpreted, they evoke ideas and suggest and provoke sensations. In addition to this, the title is a fundamental part of each piece.

ZZ. How does photography help you in the search of your identity? And, what has the use of video added to your work?

Since the beginning of my work in the eighties, my work has been photographic, although five or six years ago it went through a formal change –not its concept nor its aesthetic– through the use of video. The only aspects that make these videos different from my photographic work is the existence of space and the time in which an action occurs. Besides that, my work has not changed; in representing my ideas, I maintain the minimalistic aesthetic, I use the same materials and concepts, I still use black and white and I don’t use audio.

I don’t exactly know in which moment I started using video, but I think it happened in a very natural way, or, in other words, the development of the work itself brought me to it. Actually, people had asked me why I didn’t make videos, because of the performative character of my work, but at the time I, as an artist, was not at all interested in the idea, even though later on I permanently incorporated this medium into my work.

ZZ. What has been the result of your search throughout these years and which course is it taking?

Currently I tend to use video as a medium and not photography, but I still maintain my own aesthetic and conceptual parameters. The only difference is that, at the moment, video is a perfect medium for what I want. Surely the development of my work will lead me to other formal solutions in the future.

I have always thought that maybe a lot of the success of an artist’s work depends on finding the right tool with which he can express and “realize” his ideas.

During a lifetime of work, Marta Maria Perez Bravo has explored the rites and beliefs of Cuban religion through her own image. Her body sacrifices the symbol, creating an account of intersections between dualities, such as the visible and the invisible, the material and the spiritual, life after death, the presence of absence. That reiteration of opposites uses its own aesthetic to create narratives that, supported by the photographic document, build a universe of re-creations of rites and ceremonial objects.

Currently, her artistic proposal has led her to use other visual mediums with which she complements and continues to investigate her conceptual interests.

Marta María Pérez Bravo (Cuba, 1959). Lives and works in Mexico. Photographer. She began her studies as an artist in 1979 at the School of Visual Arts San Alejandro, Havana, Cuba. In 1984 she continued her studies at the Instituto Superior de Arte (ISA), Havana, Cuba. She has participated in numerous international solo and group exhibitions. She has won several awards for her work, such as the Guggenheim Fellowship (USA) in 1998.

Marta María Pérez Bravo (Cuba, 1959). Lives and works in Mexico. Photographer. She began her studies as an artist in 1979 at the School of Visual Arts San Alejandro, Havana, Cuba. In 1984 she continued her studies at the Instituto Superior de Arte (ISA), Havana, Cuba. She has participated in numerous international solo and group exhibitions. She has won several awards for her work, such as the Guggenheim Fellowship (USA) in 1998.ZZ. In your work, self-representation is a constant theme, ¿how did your interest in talking about various themes through your own image arise?

MM. I studied Fine Arts, but my graduate thesis, at the Instituto Superior de Arte in Havana (1984), was a photographic project, even though I never studied photography. This project consisted of photographs documenting actions that I performed outdoors, taking as its theme the popular superstitions regarding natural phenomena, appearances etc. When I was pregnant, I could no longer do these performances and I started using my own body. I started to document, in a different way, other actions related to these superstitions and popular beliefs, but now regarding my experience of motherhood. As in the first stage, these realities were constructed and ‘staged’. So, from the beginning, it was clear that using a model or another person, and not my own body would completely change the concept of the work, given that it has a strong autobiographical presence, although implicitly.

ZZ. We see that themes, like evocation and absence, are constant in your work. How have these themes continued to change throughout your career?

MM. In my work, religious themes, especially of afro-cuban origin, started to emerge. The constructed realities (constructed through the staged scenes), that are devoid of time and space, are re-creations (not recreations) of rites and ritual objects.

ZZ. What is the symbolic value of the objects in your photos? What place do you give to the objects as symbols in your photos? What does their reiterative use signify?

From the ritual objects I want to extract a meaning that goes beyond the form, though the making of these objects is done with reference to the originals and the use they are given in religious practices. Although my photography is always black and white, I use the original colors in the elaboration of these objects as a token of respect for these practices and real liturgical objects. Nevertheless, I don’t want the spectator to be distracted by these colors; I want him to focus his attention on the symbols and their meanings. Even though he might not know them at all (since they are object of separate study and profound analysis) my intention is that, when these symbols are interpreted, they evoke ideas and suggest and provoke sensations. In addition to this, the title is a fundamental part of each piece.

ZZ. How does photography help you in the search of your identity? And, what has the use of video added to your work?

Since the beginning of my work in the eighties, my work has been photographic, although five or six years ago it went through a formal change –not its concept nor its aesthetic– through the use of video. The only aspects that make these videos different from my photographic work is the existence of space and the time in which an action occurs. Besides that, my work has not changed; in representing my ideas, I maintain the minimalistic aesthetic, I use the same materials and concepts, I still use black and white and I don’t use audio.

I don’t exactly know in which moment I started using video, but I think it happened in a very natural way, or, in other words, the development of the work itself brought me to it. Actually, people had asked me why I didn’t make videos, because of the performative character of my work, but at the time I, as an artist, was not at all interested in the idea, even though later on I permanently incorporated this medium into my work.

ZZ. What has been the result of your search throughout these years and which course is it taking?

Currently I tend to use video as a medium and not photography, but I still maintain my own aesthetic and conceptual parameters. The only difference is that, at the moment, video is a perfect medium for what I want. Surely the development of my work will lead me to other formal solutions in the future.

I have always thought that maybe a lot of the success of an artist’s work depends on finding the right tool with which he can express and “realize” his ideas.

Josef Wladyka

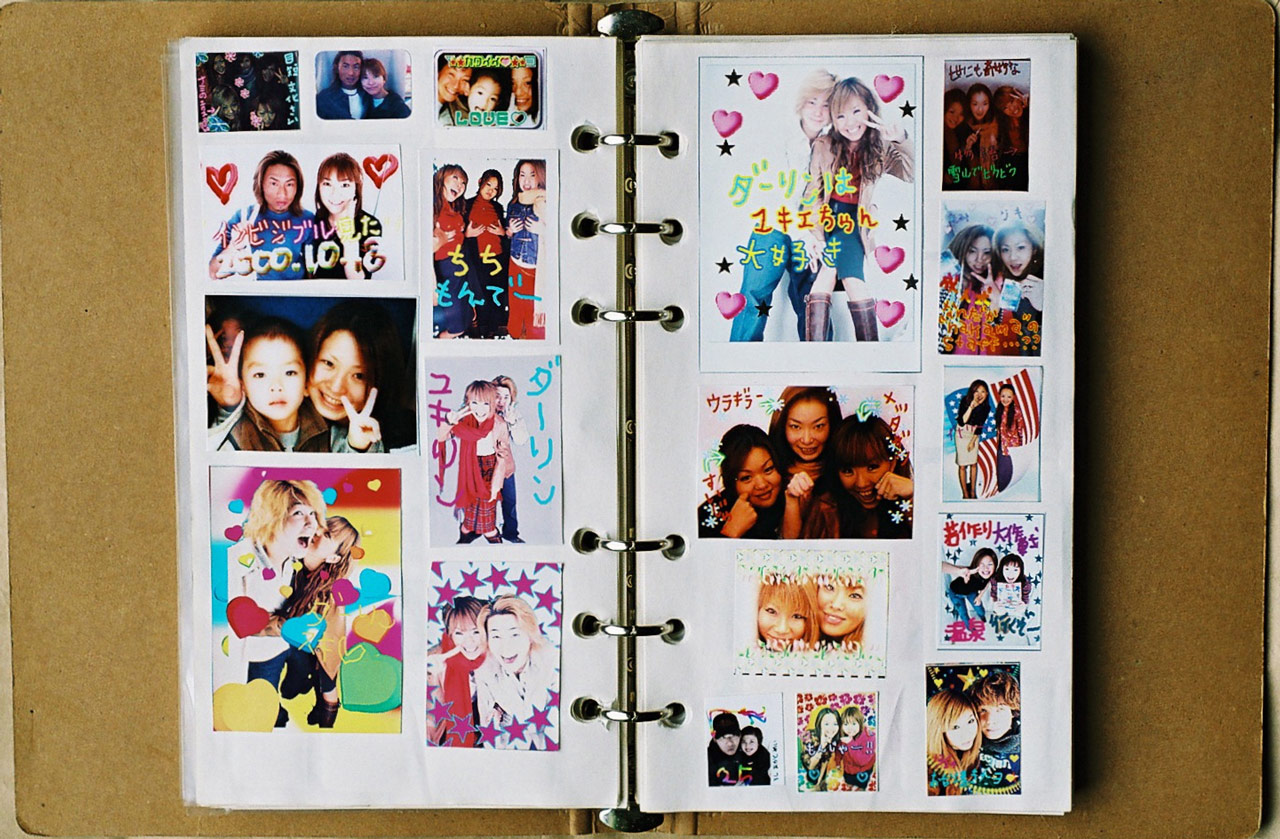

My mother left Japan more than thirty years ago and didn't return until November 2010. This is her story.

Location: Tokyo, Japan.

Cinematography: Stan Wladyka.

Music: Tyler Parkinson.

Okaasan お母さん

Beginning as a child performer in Odessa, Russia, Albert Makhtsier has been acting for over half a century. Despite being diagnosed with Parkinson's disease, Albert remains one of New York City's finest actors. This is his story.

Location: Times Square, New York City.

Cinematography: Alan Blanco.

Music: Tyler Cash.

Albert Makhtsier

Curai is a small, tight knit fishing village on the Southern Pacific Coast of Colombia. It's a place where almost everyone shares the same last name. Jacobo is a community leader there and this is one of his stories.

Location: Curai, Colombia.

Cinematography by Leonardo D'Antoni.

Music by Tyler Cash.

Jacobo Castillo Salazar

These are a collection of peoples' personal stories told through a single shot. Each story is an exploration of the universal essence of the human condition and our connection to one another that extends beyond any boundaries.

Josef Wladyka. Lives in New York. Influenced by his parents, Josef developed a fascination for movies from a very young age. He began experimenting with filmmaking in high school and has since created several (short) films and commercials that have been screened at festivals around the world. He holds a MFA from NYU Tisch Graduate Film where he won a Spike Lee Fellowship. His debut feature film, Manos Sucias (2014), has won various awards.

Josef Wladyka. Lives in New York. Influenced by his parents, Josef developed a fascination for movies from a very young age. He began experimenting with filmmaking in high school and has since created several (short) films and commercials that have been screened at festivals around the world. He holds a MFA from NYU Tisch Graduate Film where he won a Spike Lee Fellowship. His debut feature film, Manos Sucias (2014), has won various awards.

My mother left Japan more than thirty years ago and didn't return until November 2010. This is her story.

Location: Tokyo, Japan.

Cinematography: Stan Wladyka.

Music: Tyler Parkinson.

Okaasan お母さん

Beginning as a child performer in Odessa, Russia, Albert Makhtsier has been acting for over half a century. Despite being diagnosed with Parkinson's disease, Albert remains one of New York City's finest actors. This is his story.

Location: Times Square, New York City.

Cinematography: Alan Blanco.

Music: Tyler Cash.

Albert Makhtsier

Curai is a small, tight knit fishing village on the Southern Pacific Coast of Colombia. It's a place where almost everyone shares the same last name. Jacobo is a community leader there and this is one of his stories.

Location: Curai, Colombia.

Cinematography by Leonardo D'Antoni.

Music by Tyler Cash.

Jacobo Castillo Salazar

These are a collection of peoples' personal stories told through a single shot. Each story is an exploration of the universal essence of the human condition and our connection to one another that extends beyond any boundaries.

Josef Wladyka. Lives in New York. Influenced by his parents, Josef developed a fascination for movies from a very young age. He began experimenting with filmmaking in high school and has since created several (short) films and commercials that have been screened at festivals around the world. He holds a MFA from NYU Tisch Graduate Film where he won a Spike Lee Fellowship. His debut feature film, Manos Sucias (2014), has won various awards.

Josef Wladyka. Lives in New York. Influenced by his parents, Josef developed a fascination for movies from a very young age. He began experimenting with filmmaking in high school and has since created several (short) films and commercials that have been screened at festivals around the world. He holds a MFA from NYU Tisch Graduate Film where he won a Spike Lee Fellowship. His debut feature film, Manos Sucias (2014), has won various awards.Noah Kalina

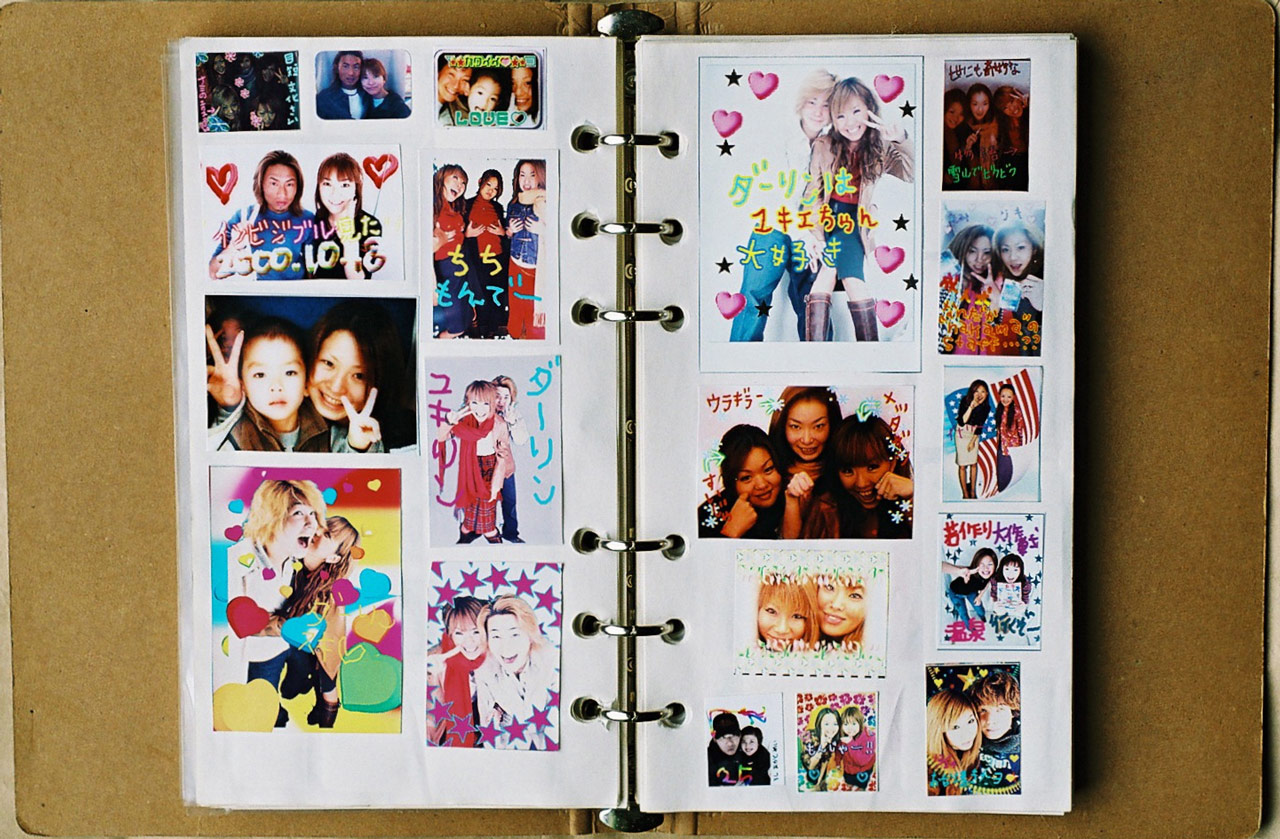

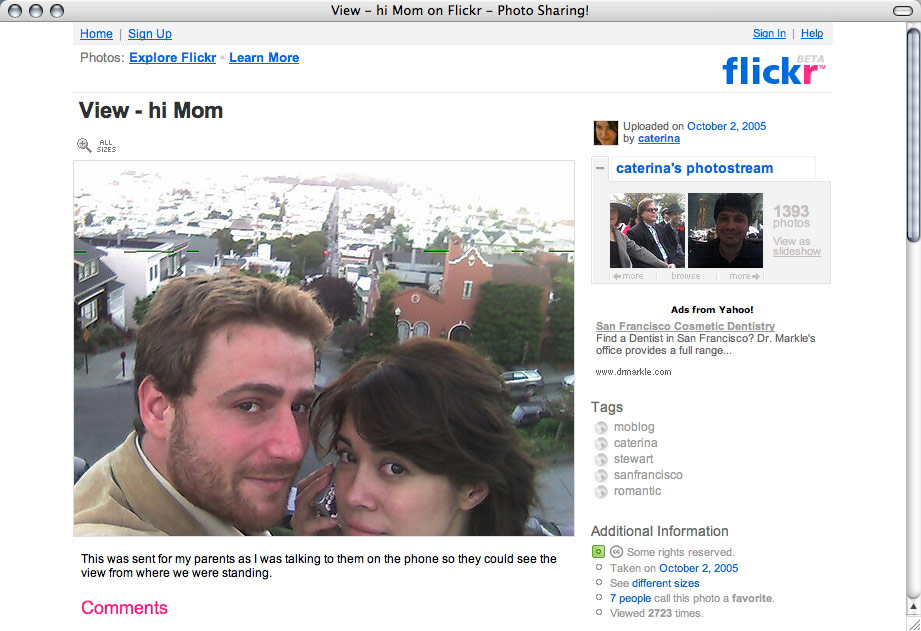

Noah Kalina has been taking a photograph of himself every day since January 2000. Originally it was meant to be a photo project, but in 2006 he was inspired by a project by Ahree Lee, a graphic designer from California who had put a time-lapse video of herself on YouTube. Noah decided to do the same with his self-portraits and, within three weeks, it became an international internet sensation.

Noah Kalina (US, 1980) is a photographer based in Brooklyn and Lumberland, New York. He graduated from the School of Visual Arts with a BFA in photography. His project ‘Everyday’ was a worldwide hit. His work has been exhibited all over the world: in the U.S., Switzerland, Italy, Belgium, France, Australia, England, Canada, Germany and the Netherlands. He also has given lectures in various countries. To see more of his work go to: noahkalina.com

Noah Kalina (US, 1980) is a photographer based in Brooklyn and Lumberland, New York. He graduated from the School of Visual Arts with a BFA in photography. His project ‘Everyday’ was a worldwide hit. His work has been exhibited all over the world: in the U.S., Switzerland, Italy, Belgium, France, Australia, England, Canada, Germany and the Netherlands. He also has given lectures in various countries. To see more of his work go to: noahkalina.comNoah Kalina has been taking a photograph of himself every day since January 2000. Originally it was meant to be a photo project, but in 2006 he was inspired by a project by Ahree Lee, a graphic designer from California who had put a time-lapse video of herself on YouTube. Noah decided to do the same with his self-portraits and, within three weeks, it became an international internet sensation.

Noah Kalina (US, 1980) is a photographer based in Brooklyn and Lumberland, New York. He graduated from the School of Visual Arts with a BFA in photography. His project ‘Everyday’ was a worldwide hit. His work has been exhibited all over the world: in the U.S., Switzerland, Italy, Belgium, France, Australia, England, Canada, Germany and the Netherlands. He also has given lectures in various countries. To see more of his work go to: noahkalina.com

Noah Kalina (US, 1980) is a photographer based in Brooklyn and Lumberland, New York. He graduated from the School of Visual Arts with a BFA in photography. His project ‘Everyday’ was a worldwide hit. His work has been exhibited all over the world: in the U.S., Switzerland, Italy, Belgium, France, Australia, England, Canada, Germany and the Netherlands. He also has given lectures in various countries. To see more of his work go to: noahkalina.comXtabay Alderete

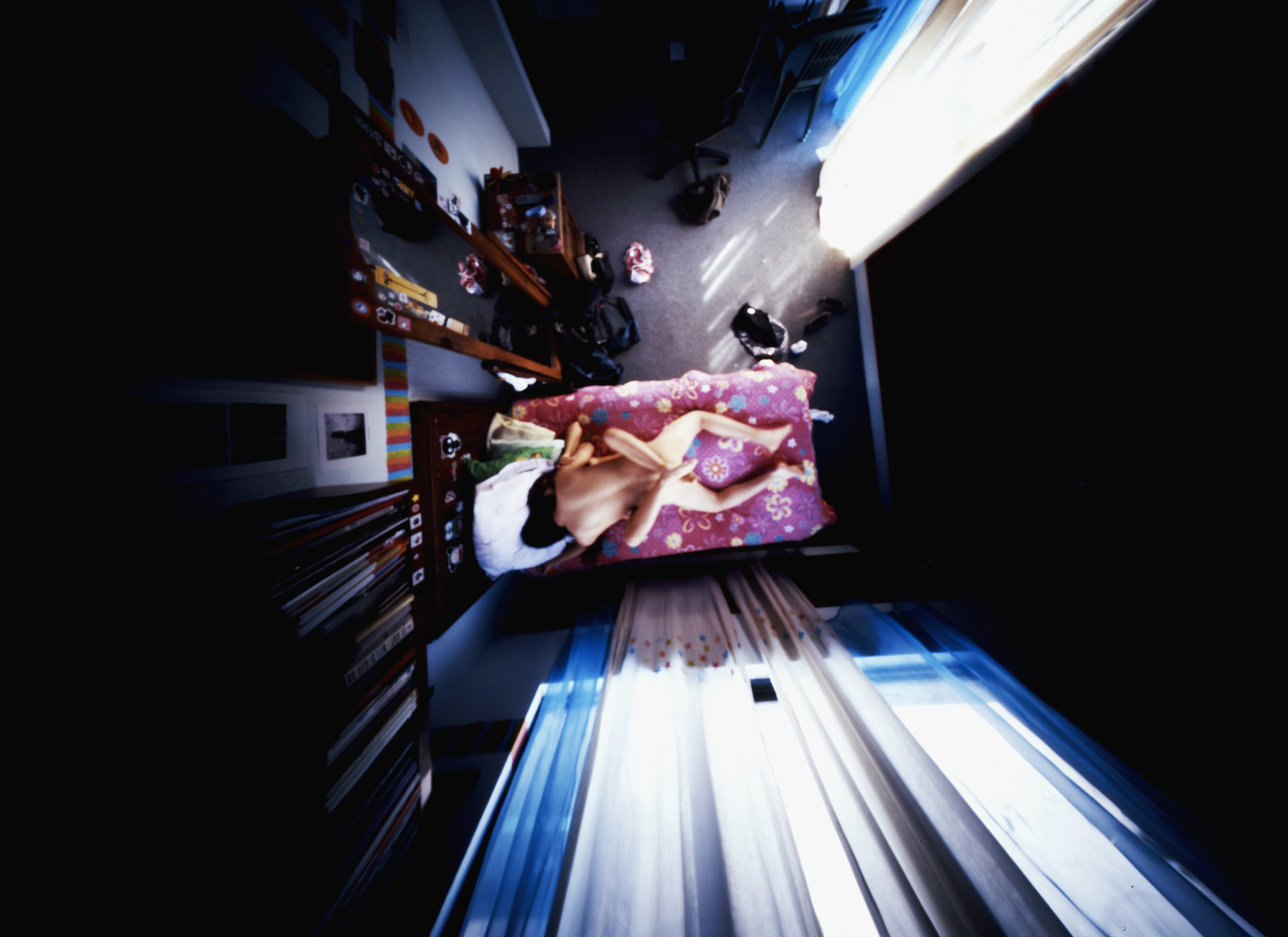

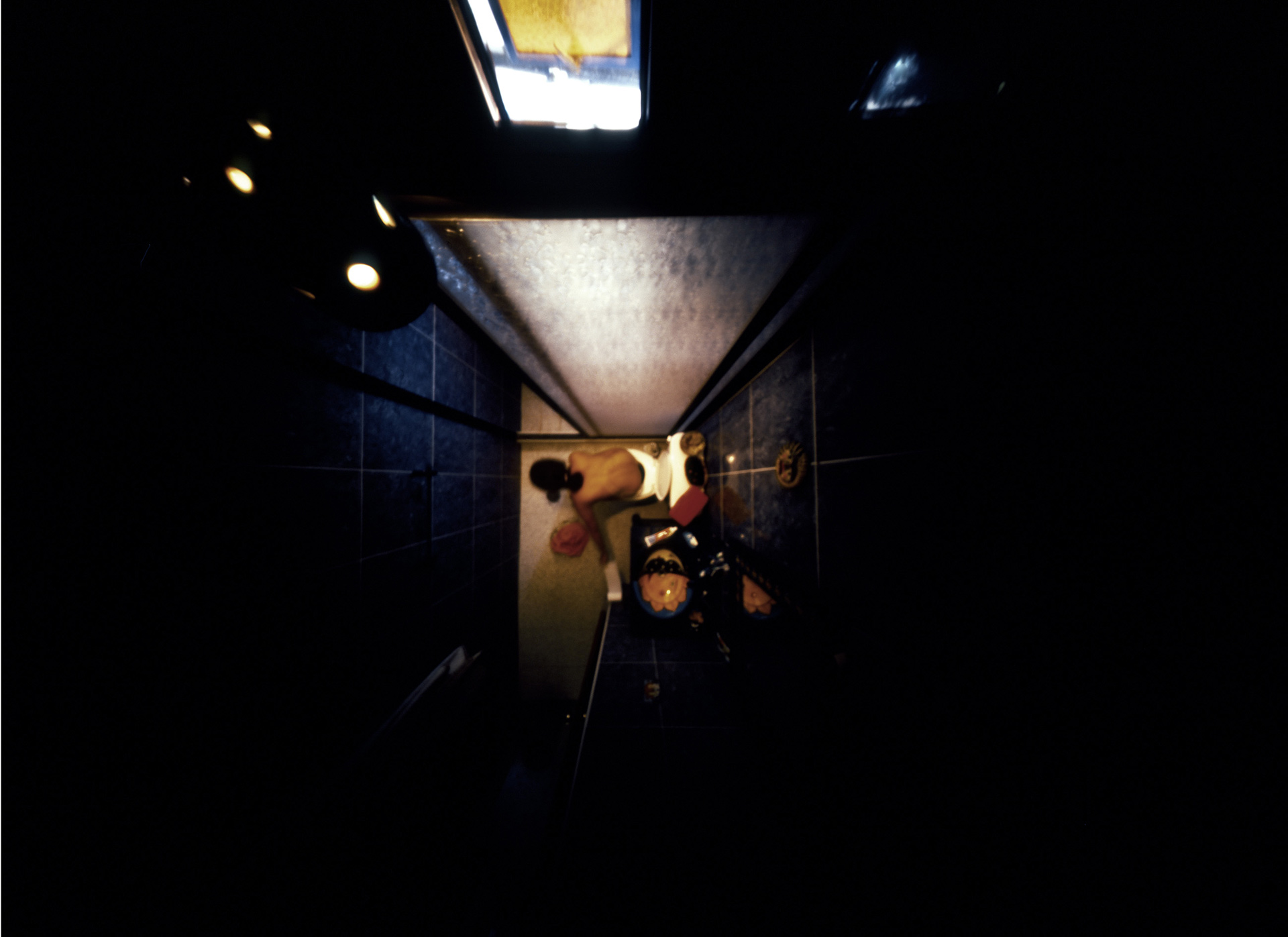

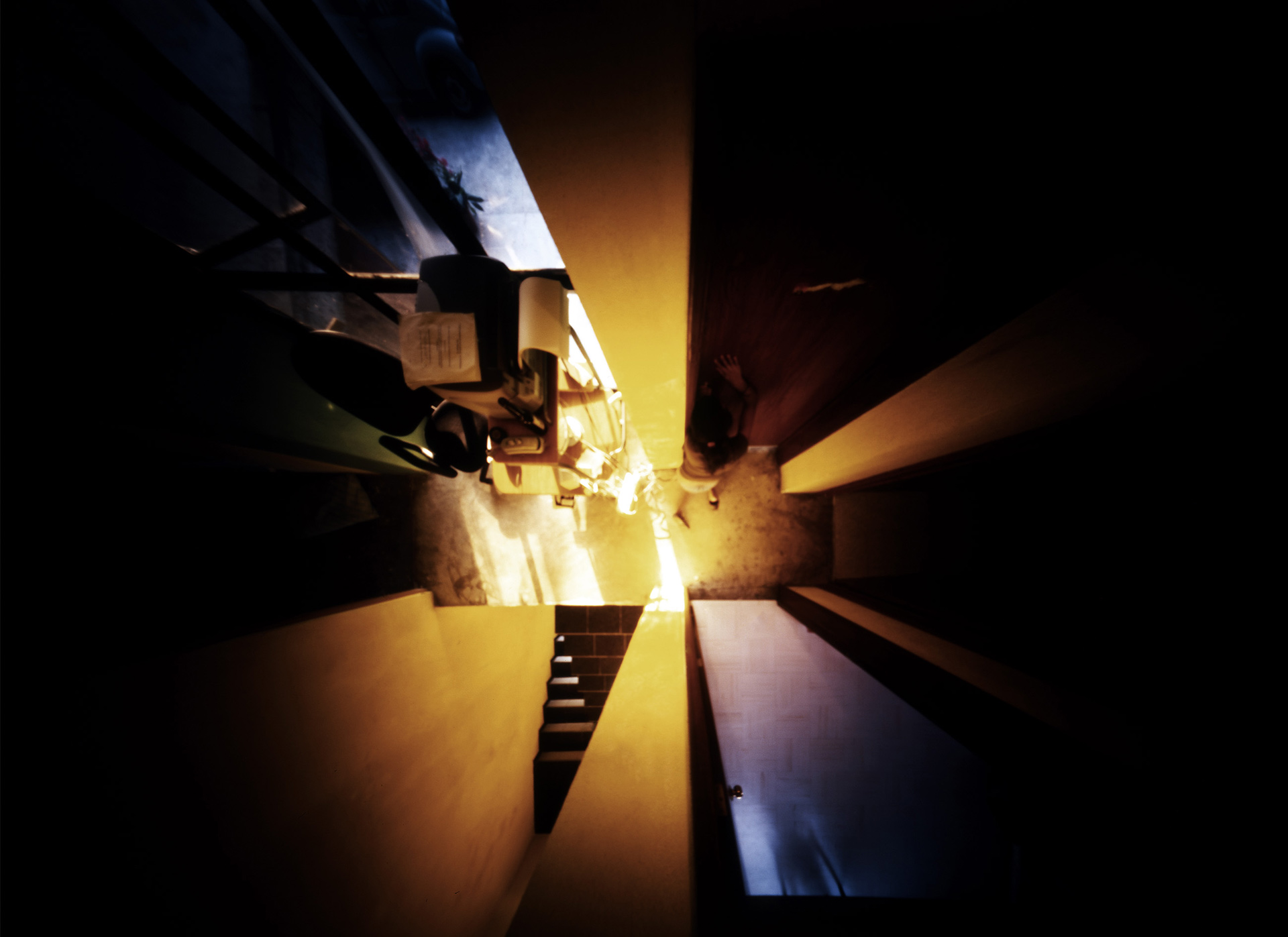

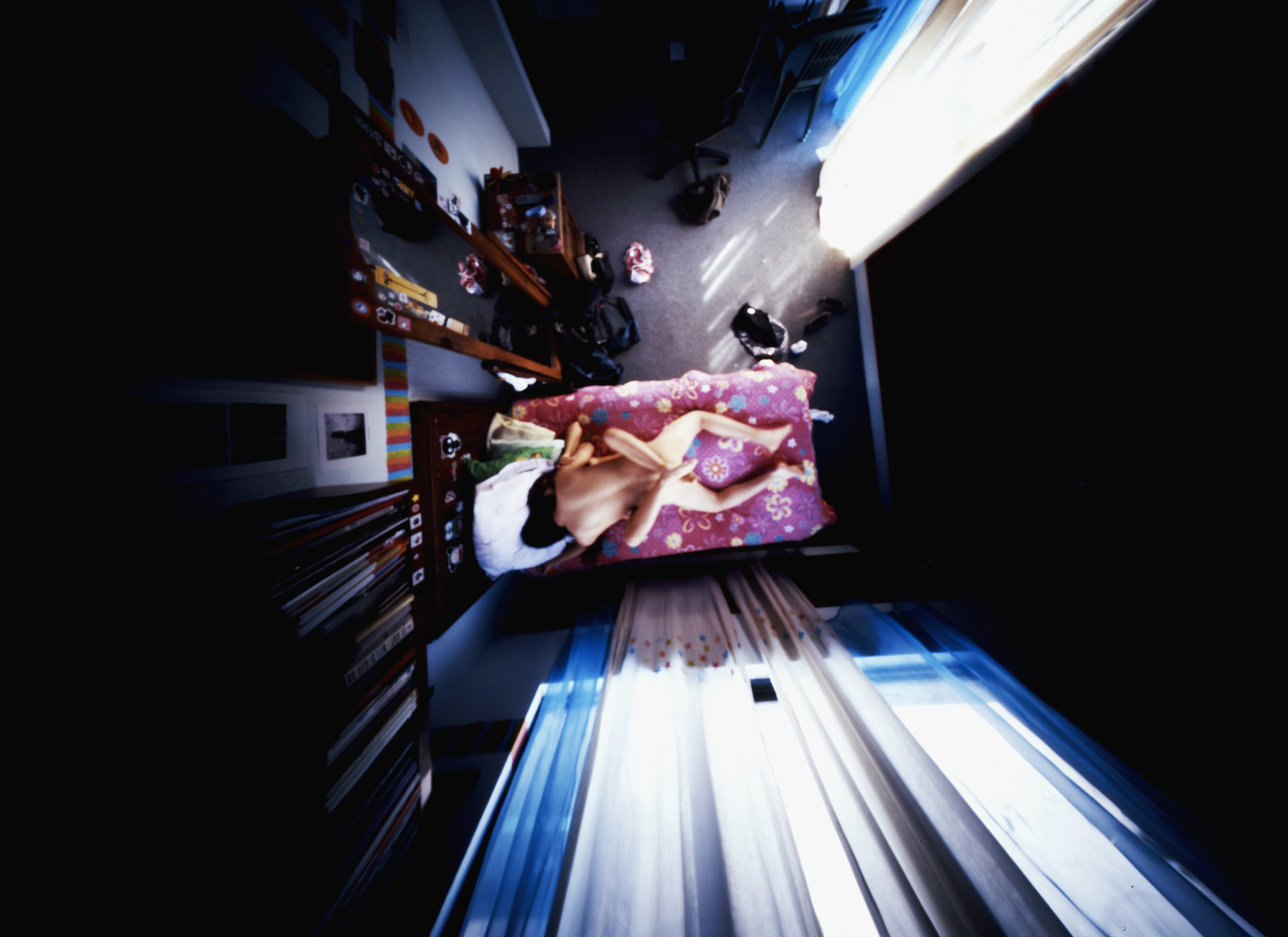

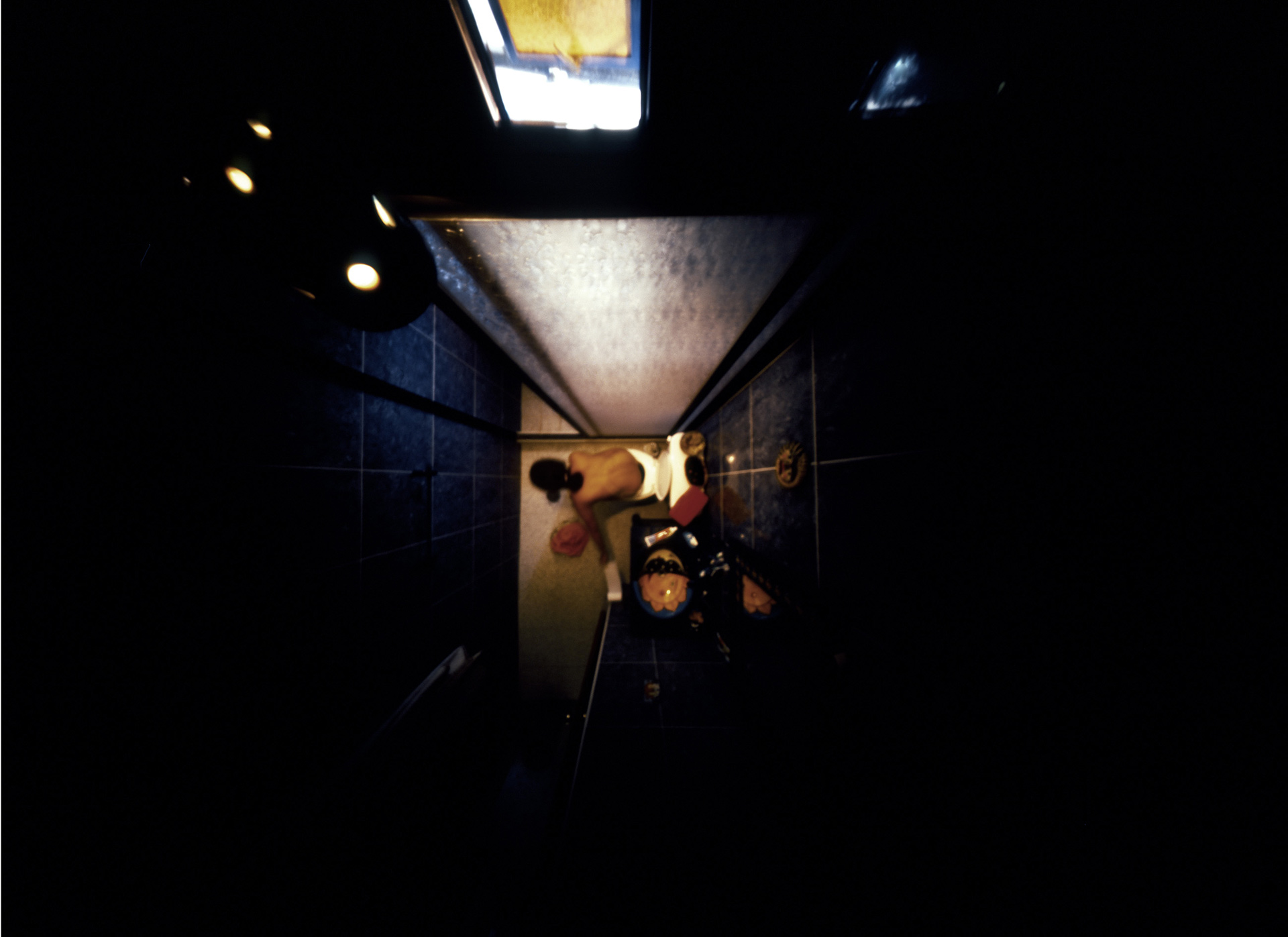

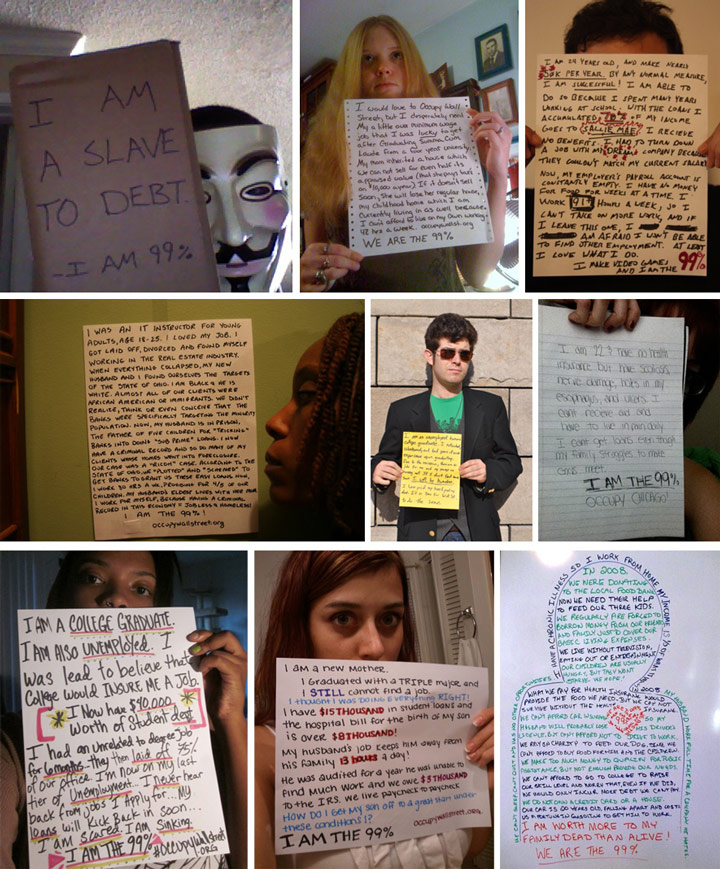

This project is based on the idea of the vigilant eye that threatens us to do no wrong. With this idea in mind, the author depicts her family environment, from conflicts to normal daily life, as if they were being monitored by a divine, human or mechanical being (God, spies or Big Brother). She presents these images from the point of view that each one of us is somehow controlled by a system, which reinforces the moral burden one feels when committing sins, crimes and mistakes.

The work presents daily life through images taken from different angles. With her handmade pinhole camera, the author establishes a certain feeling of omnipresence. She allows us to immerse ourselves in her experiences and the daily life between the walls of her home, giving the spectator a panoptic vision of her family as the so-called social unit of our times. Proving, in the end, that the society of the spectacle has encouraged a certain voyeurism through reality shows, which compel us to take sides and to judge the acts of the observed, and which puts us in the position of the divine being that tilts the scale of judgement towards the good or the bad.

We invite you to learn more about the preoccupations and the questionings of the author through this video.

Xtabay Alderete (Mexico, 1979). Lives and works in Mexico City. Graduated from the School of Visual Arts, UNAM, with a bachelor´s degree in Visual Arts. At present, she studies a master in Visual Arts at the Academy of San Carlos, UNAM. Her artistic work focuses primarily on photography. In 2013 she took part in the exhibition (Re)Presentations, Contemporary Latin-American Photography, organised by PHotoEspaña, Madrid. Currently, she intervenes in landscapes that contain memory, oblivion, death and devastation, using objects.

Xtabay Alderete (Mexico, 1979). Lives and works in Mexico City. Graduated from the School of Visual Arts, UNAM, with a bachelor´s degree in Visual Arts. At present, she studies a master in Visual Arts at the Academy of San Carlos, UNAM. Her artistic work focuses primarily on photography. In 2013 she took part in the exhibition (Re)Presentations, Contemporary Latin-American Photography, organised by PHotoEspaña, Madrid. Currently, she intervenes in landscapes that contain memory, oblivion, death and devastation, using objects.