- Adam Wiseman. Tlatelolco desmentido

- Andrés Cruzat. Pasado y presente fundidos en imágenes para recordar el golpe en Chileasado y presente fundidos en imágenes para recordar el golpe en Chile

- Antropographia (2013, 5th Ed)

- Catchlight (2015, Previously PhotoPhilantrophy 2009)

- Charlie Phillips, Documenting London’s African Caribbean funerals

- Proyecto editorial 'La Diaria

- Daniela Rossell, Ricas y Famosas

- Festival de cine de los pueblos indígenas en Chaco

- Drik. Platform for local photographers in the majority world

- Festival della Fotografia Etica (World.Report Award 2015)

- Gustavo Jononovich, Free Shipping (2014-2015)

- Jessica Dimmock, The Ninth Floor

- Jörg Colberg, Responsibility and Truth in Photography

- Kohei Yoshiyuki, The Park

- Laura González, La mirada del otro otro. La producción fotográfica de grupos minoritarios

- Laura Gonzalez Flores, Vanitas y documentación: Reflexiones en torno a la estética del fotoperiodismo

- Natar Dvir. Eighteen

- Oriana Eliçabe, Movimiento global

- PH15

- Raquel Brust Giganto

- Reza Golchin Bazaar

- Ruben Salvadori, Photojournalism Behind the Scenes

- Shahidul Alam. Reframing the Majority World

- Shahidul Alam, News

- Sim Chi Yin, China's "Rat Tribe"

- Testigos presenciales. Documentalistas mexicanos

- Tomás Caballero Roldán, Orianómada. Del fotoperiodismo al activismo fotográfico global. La fotografía de Oriana Eliçabe

- Skateistan x Impossible Photography Project

[core_state] => 1 [core_access] => 1 [core_metadata] => {"robots":"","author":"","rights":"","xreference":""} [core_created_user_id] => 838 [core_created_by_alias] => [core_created_time] => 2015-09-21 16:08:06 [core_images] => {"image_intro":"","float_intro":"","image_intro_alt":"","image_intro_caption":"","image_fulltext":"","float_fulltext":"","image_fulltext_alt":"","image_fulltext_caption":""} [core_modified_time] => 2015-09-22 16:50:48 [core_language] => en-GB [core_catid] => 59 [core_publish_up] => 2015-09-21 16:08:06 [core_publish_down] => 0000-00-00 00:00:00 [content_type_title] => Article [router] => ContentHelperRoute::getArticleRoute [author] => Elisa Rugo [author_email] => elisa@zonezero.com [link] => index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=325:references&catid=59&lang=en-GB [displayDate] => 2015-09-21 16:08:06 [event] => stdClass Object ( [afterDisplayTitle] => [beforeDisplayContent] => [afterDisplayContent] => ) [text] =>

- Adam Wiseman. Tlatelolco desmentido

- Andrés Cruzat. Pasado y presente fundidos en imágenes para recordar el golpe en Chileasado y presente fundidos en imágenes para recordar el golpe en Chile

- Antropographia (2013, 5th Ed)

- Catchlight (2015, Previously PhotoPhilantrophy 2009)

- Charlie Phillips, Documenting London’s African Caribbean funerals

- Proyecto editorial 'La Diaria

- Daniela Rossell, Ricas y Famosas

- Festival de cine de los pueblos indígenas en Chaco

- Drik. Platform for local photographers in the majority world

- Festival della Fotografia Etica (World.Report Award 2015)

- Gustavo Jononovich, Free Shipping (2014-2015)

- Jessica Dimmock, The Ninth Floor

- Jörg Colberg, Responsibility and Truth in Photography

- Kohei Yoshiyuki, The Park

- Laura González, La mirada del otro otro. La producción fotográfica de grupos minoritarios

- Laura Gonzalez Flores, Vanitas y documentación: Reflexiones en torno a la estética del fotoperiodismo

- Natar Dvir. Eighteen

- Oriana Eliçabe, Movimiento global

- PH15

- Raquel Brust Giganto

- Reza Golchin Bazaar

- Ruben Salvadori, Photojournalism Behind the Scenes

- Shahidul Alam. Reframing the Majority World

- Shahidul Alam, News

- Sim Chi Yin, China's "Rat Tribe"

- Testigos presenciales. Documentalistas mexicanos

- Tomás Caballero Roldán, Orianómada. Del fotoperiodismo al activismo fotográfico global. La fotografía de Oriana Eliçabe

- Skateistan x Impossible Photography Project

[id] => 325 [language] => en-GB [catid] => 59 [jcfields] => Array ( ) ) 1

Aula de Creación Visual

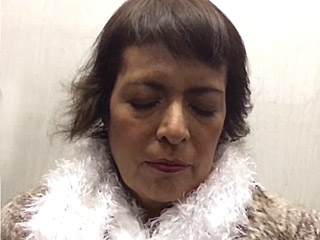

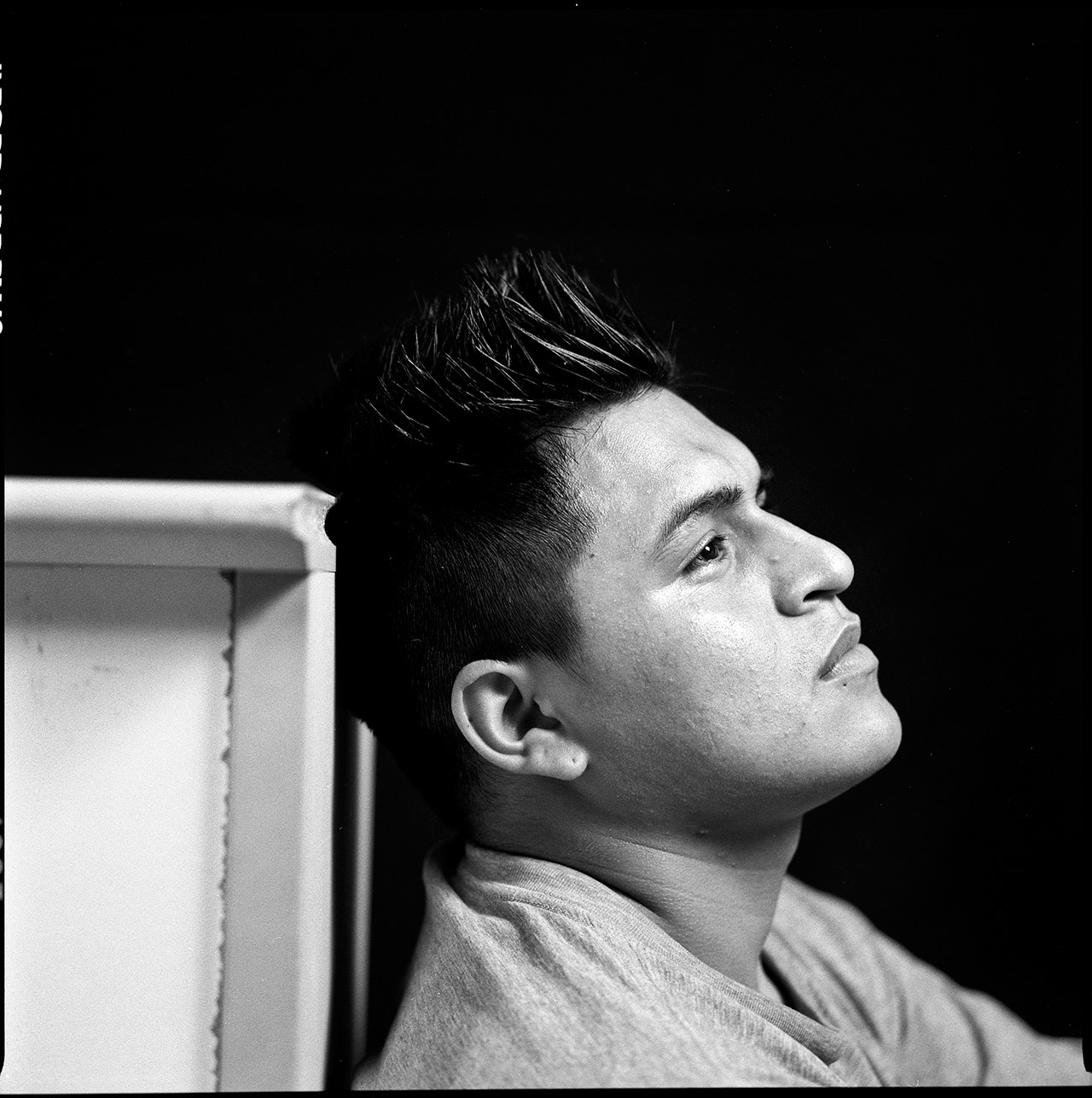

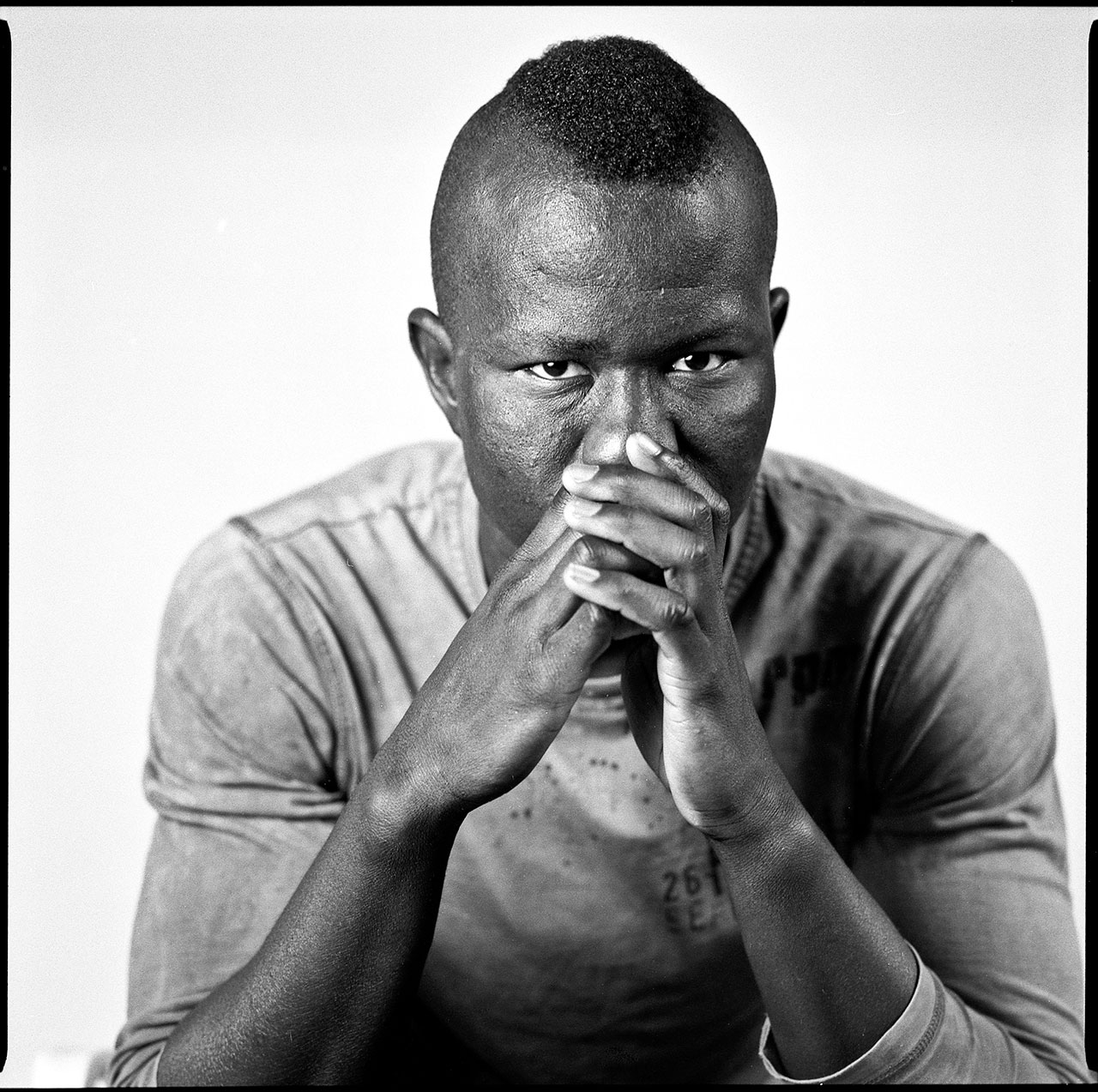

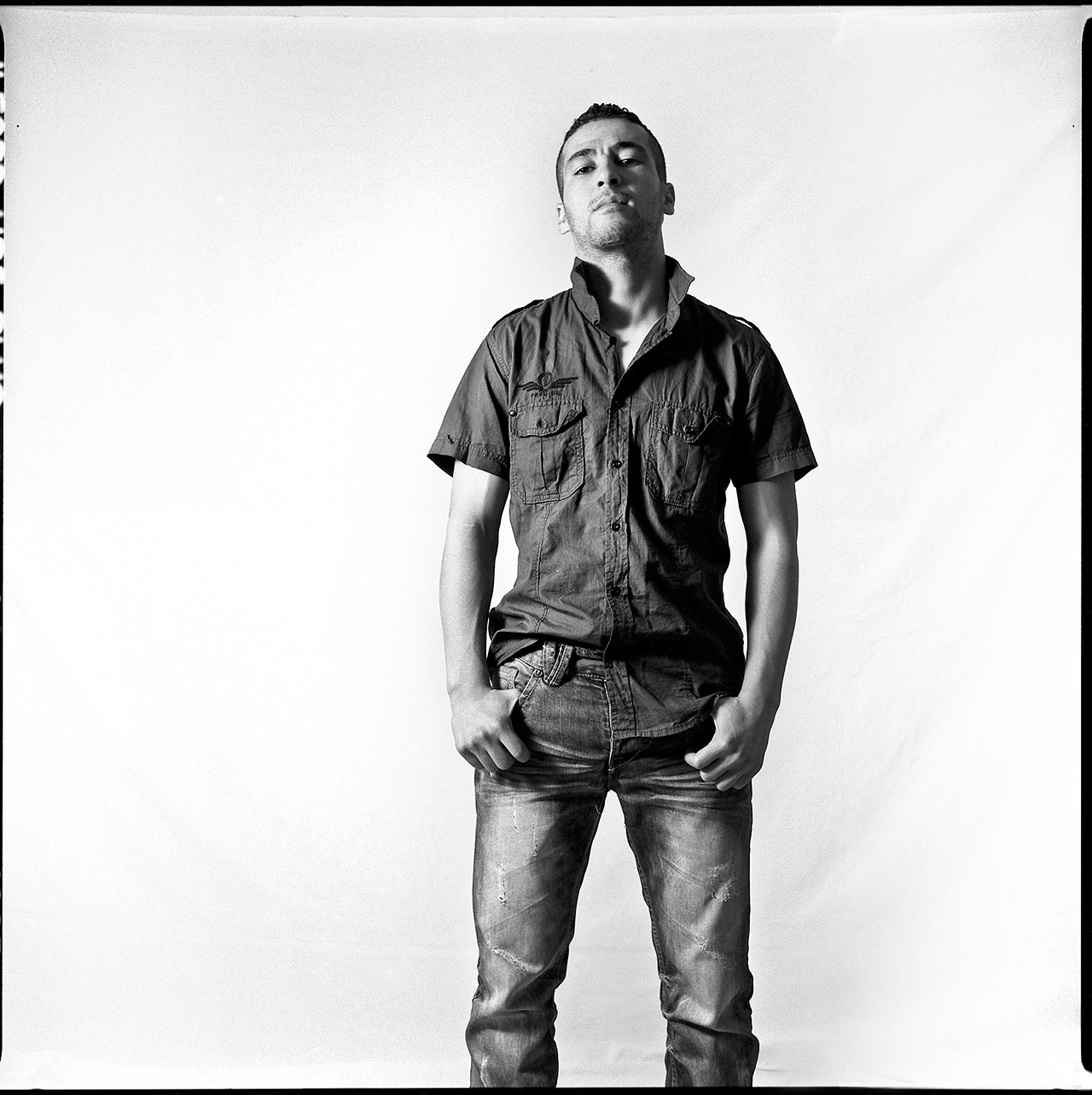

HHamza has been for almost three years in Catalunya, he comes from Alger, the capital of Algeria.

"Truth be told, I don’t know how much longer I am going to stay here, it is all up to fate. I could go now or I could stay until… I don’t know, I truly don’t know."

"The thing that made me migrate is that I wanted to change. I wanted to change myself. I was in the wrong path and I wanted to change my ways, my friends, a little of everything because I was in the wrong path. (…) I came here all over from Marsella in train. I went out to the boardwalk and it was a Friday night, everyone was there, there was a party and some other things. I thought to myself “Wow” I thought it was amazing…"

"Of course I would go back to my country but not yet. I’ve got everything in there, family, is my land, my country, and I’ve got to be there. I have to be buried in Argelia, you know?"

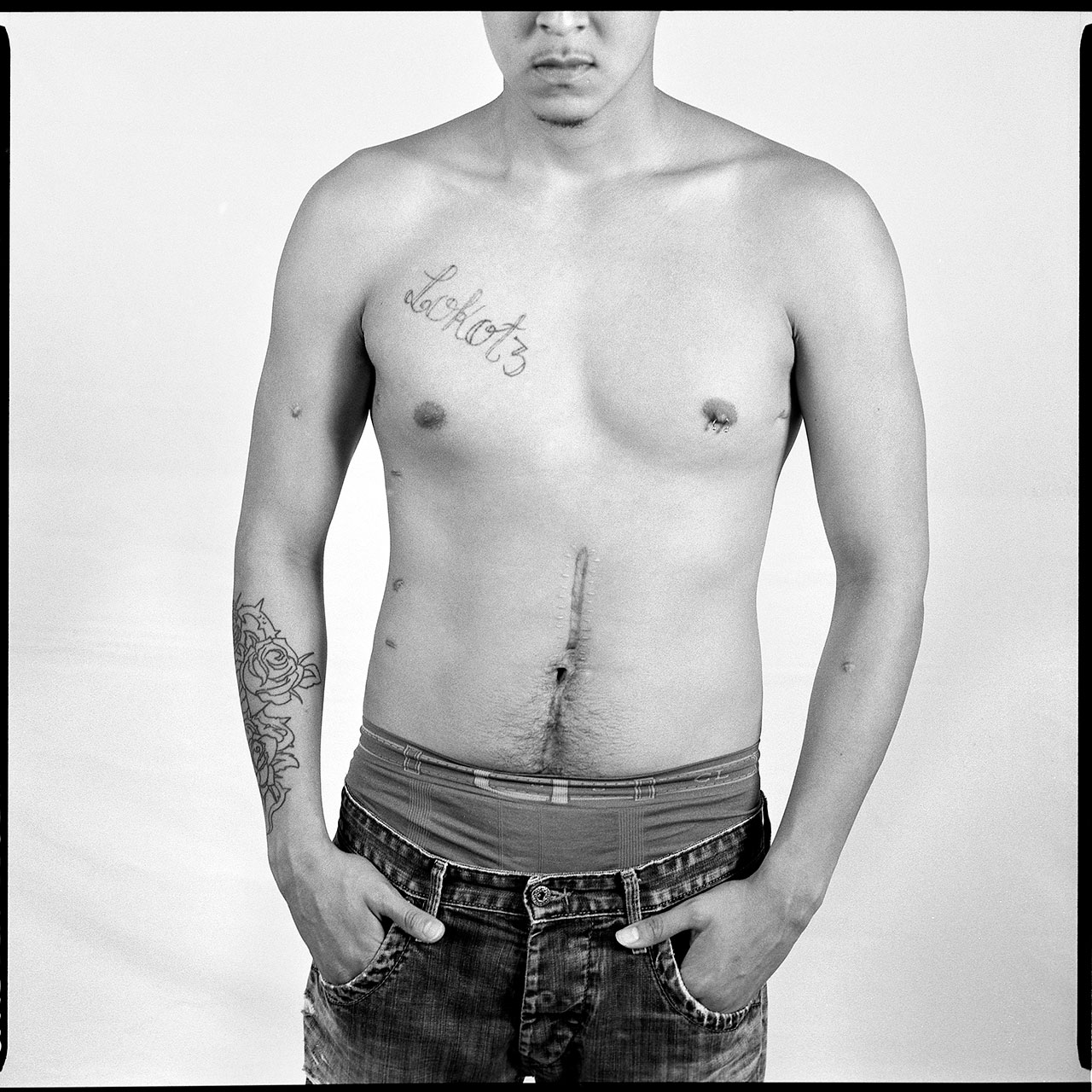

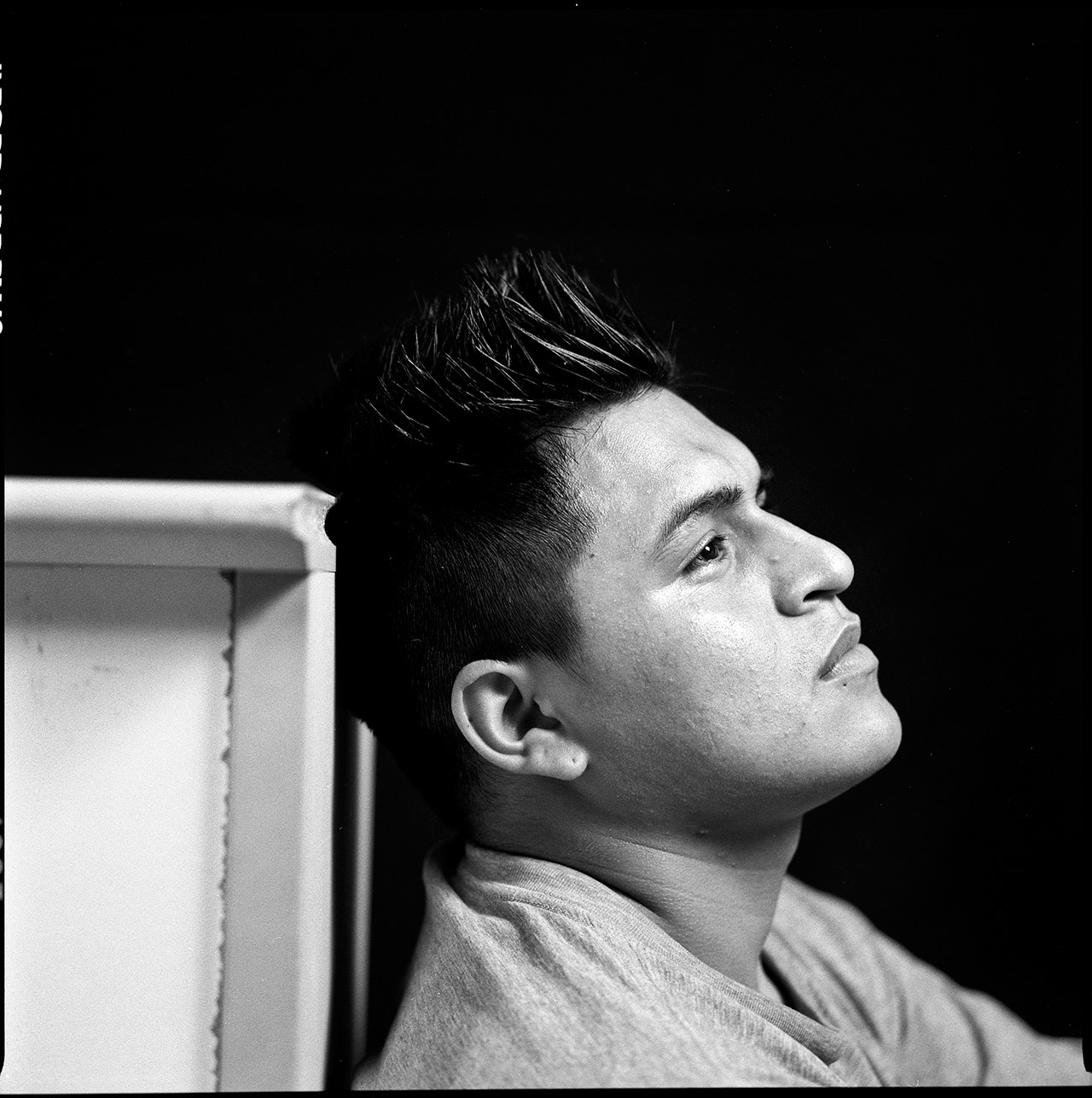

Gerson is a youngster from Guatemala City. He started working as a model and interiorist but in order to grow he had to move to another country.

“I left my country because you can’t grow over there, the country is extremely poor and you just can’t. I think here, asking for help, you could get ahead (…) I didn’t come as a migrant because I had all my papers in order, I came here by plane and everything was going just fine, too fine (…) I only miss my family, but one must make sacrifices to get ahead so that is why I’m here.”

“I chose Spain because in the United States they keep an eye on migrants and it is harder to be there. My future here is look for a job, seek for ways to improve my life and bring my family here.”

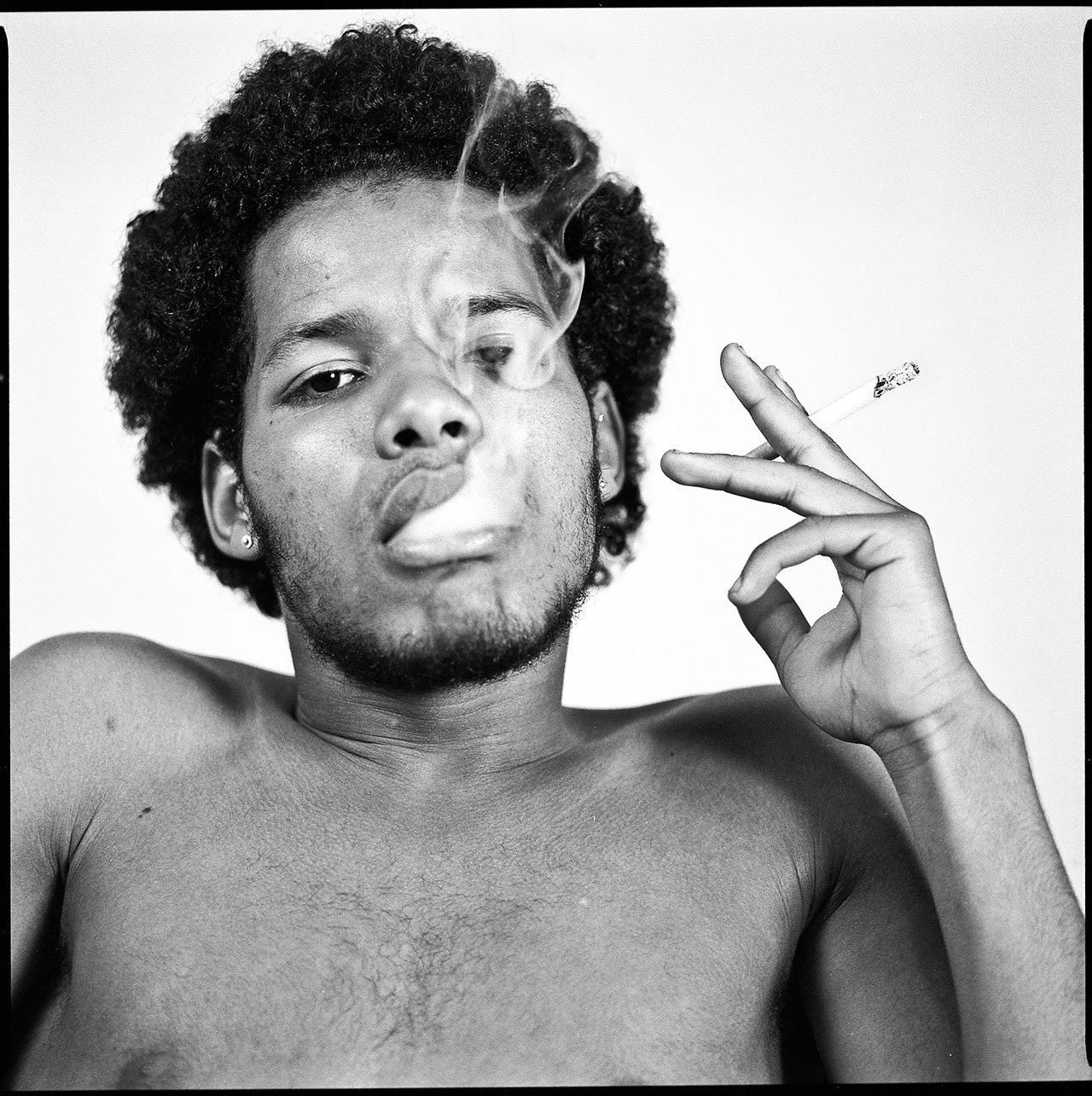

Julian comes from the little city of Dosquebradas, one of the principal industrial core from Colombia.

“The truth is that the place where I come from is very dangerous, I kept myself involved in odd things and they were going to kill me. That’s why I moved here (…) I have been in Catalunya for two or three years and a year and a half locked. I do not know how much longer will I stay here. I’ll see what I do once I’m out.”

“Uf! What I remember the most of my country is my people, my family, my brothers and the party. Uy! Is what I remember the most. I would not think it twice, I would go back because all my family is there and danger is gone. I miss Colombia a lot, of course I would go back…”

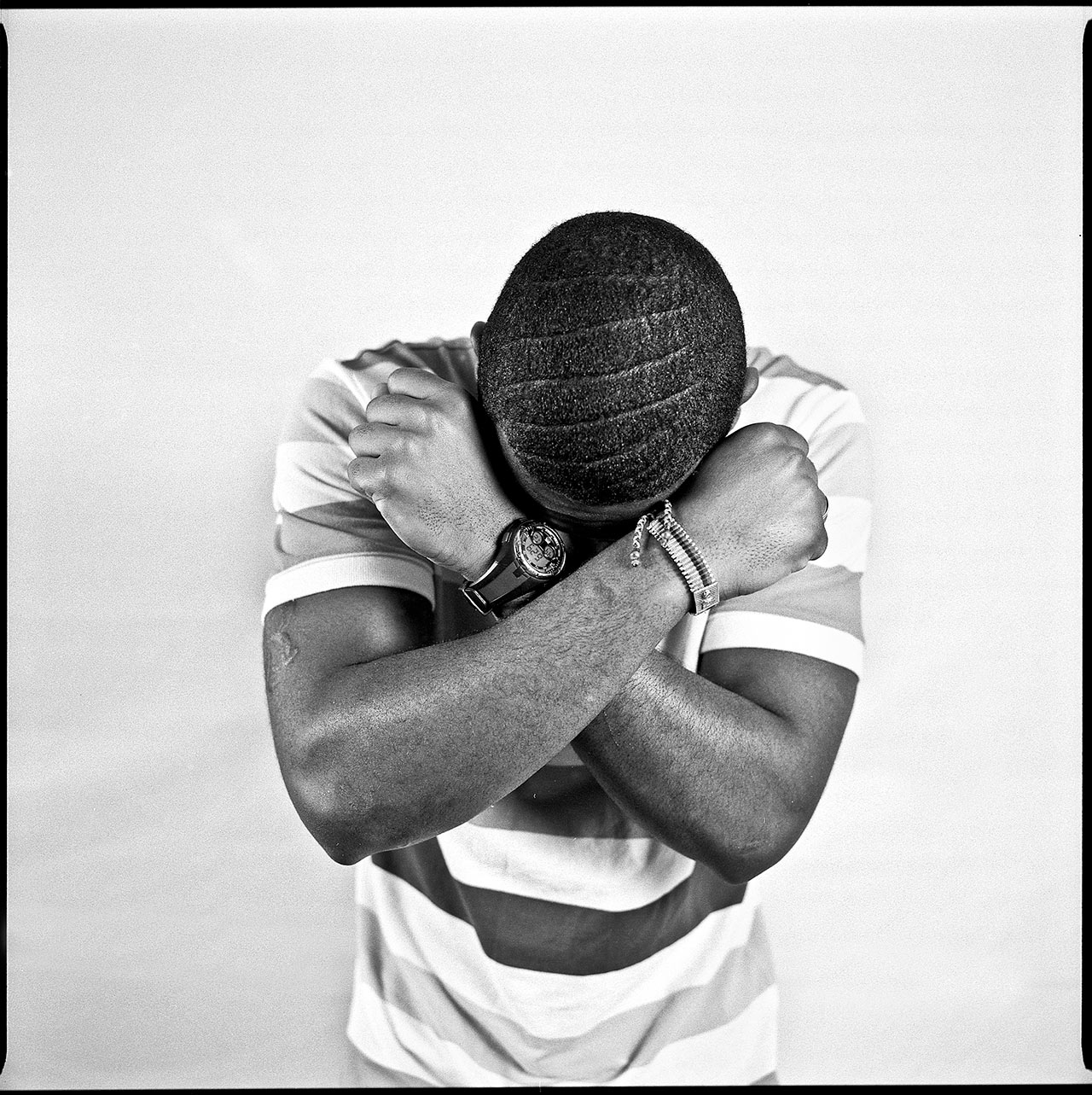

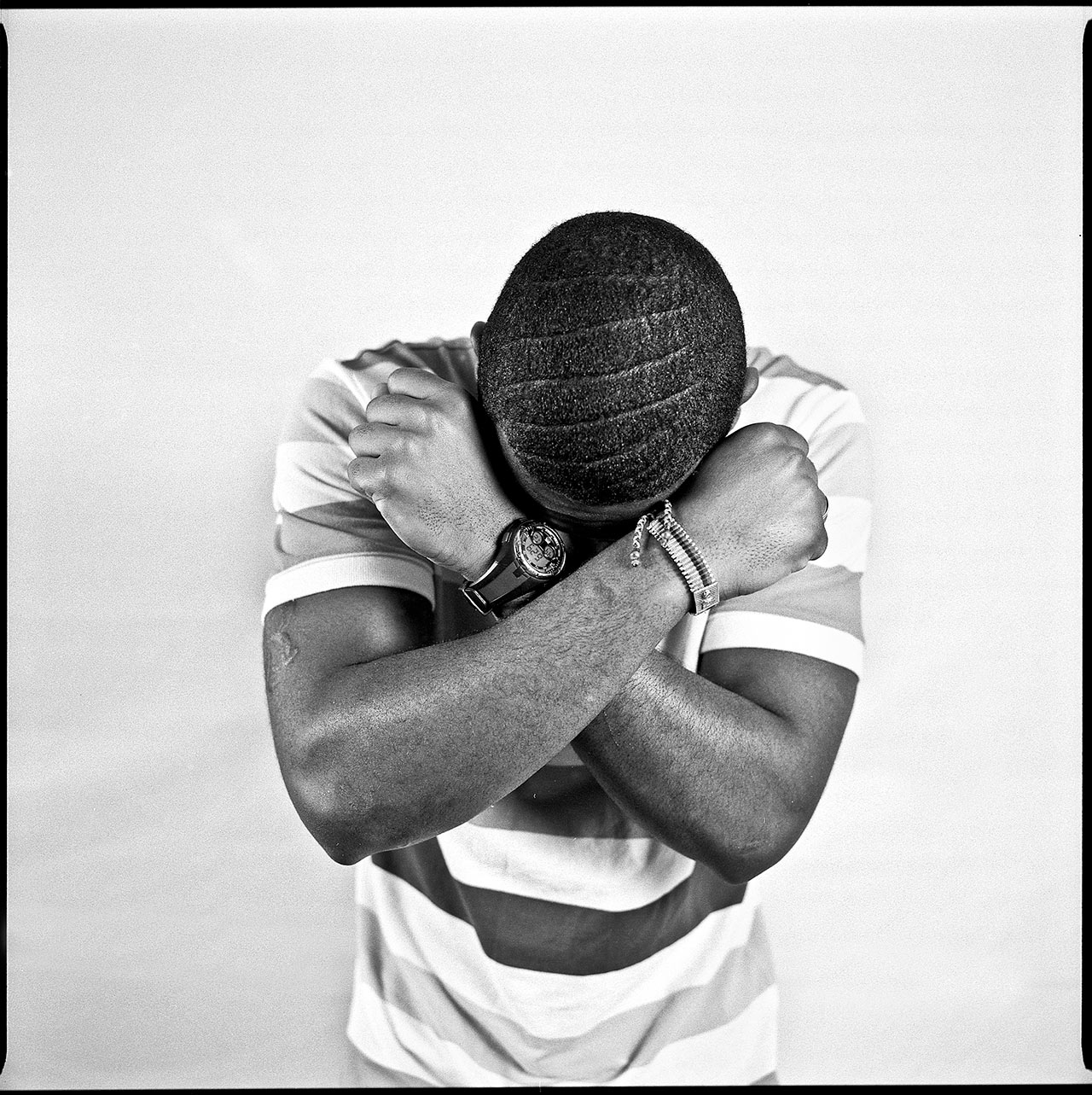

Mahmoud was born in Dakar, capital of Senegal. He has been in Catalunya for six years.

“I changed of country for many reasons. I though that once I get into Spain I could get some money, help my family, these kind of things (…) I arrived in ship from Mauritania to Tenerife. When I arrived some people took care of me because I was underage, I was 16, and they put me in a youth centre until I was 18. (…) I arrived to Europe to get a job, earn some money to help my family, to change their lives and the hard way they live right now there. That is what I thought…”

“We were 93 people in a ship that wasn’t big. It took us 6 days to get to Tenerife. I had never been in the sea, I continuously kept throwing up and dizzy. There were some people that were on the verge of dying but everyone arrived alive. (…) I though that it was a ship not a canoe. When I paid the money they told me it was a ship and I paid 1200 euros.”

“I saw many people that lived in Europe for 5 yeas and then they went back to my country and they had a house, a car, and then I think: How do these people got the money? I have been 20 years working and I just can’t anything, not even a house. Let’s see how is Europe.”

Ismael was born in the capital of Ecuador, Quito. But he has been in Hospitalet city for nine years.

“My mom took me here when I was little, I didn’t know anything, and now, here I am. (…) Right now I wouldn’t go to my country, if I ever go back is going to be for holidays. I would go back once I’m older, to die there and remain there always.”

“When I arrived here nothing seemed easy. I saw my mother working, working quite a lot, and she still does it. And no, as a child I didn’t see life and street as easy things. (…) I always lived in Hospitalet, my neighborhood was very problematic but as every neighborhood it has its good qualities. (…) I remember myself being at school and they picked up someone and started throwing bottles to him, he couldn’t go further from the entrance door, everyone was throwing bottles to him from there…”

Yassine doesn’t speak Spanish. He has only been in Catalunya for three months. His story of how life took him to Europe is the most singular story we found in this project.

Everyone calls him Sáhara. He was born in Dajla, the capital of a province of an old Spanish cologne of the Western Sahara. Today it is occupied by Morocco.

Against his willing, when Yassine was 15 years old, he went to Morocco to do his higher studies, but his support to the Sahara’s independence generate him a series of troubles with the authorities and was locked for 8 months in a Moroccan jail. When he finally achieved his freedom, his family did everything they could to expel him from the country until get, previously paid, a fake visa to go to Europe.

Romeo is Dominican but almost his entire life he has been in Spain.

“I came here when I was eight years old. I couldn’t decide where to go, my mother brought me. I have been here in Catalunya for 11 years, and the truth is, I didn’t think about the time I was going to stay…”

“I miss my entire country, specially the food. Rice with bandule, coco milk and cutlet… or the “Dominican flag”, rice with beans and meat (…)In the Dominican Republic, there are some people that have almost no money; and there are some others that have a great, great time.”

Edwin came to Spain for holidays in 2001. He came to visit his mother and never went back to Colombia.

“I was born in Colombia. My parents came to Spain when I was little and that is the reason I came (…) I thought that Spain was bigger, richer. It wasn’t heaven, but when you arrive here everything is different, you know?, You have to get used to a new culture, a new way of living. Everything is stranger but little by little you adapt yourself. (…) Colombia is very poor but the people are happier and fine with the things they have, they are very humble.”

“Too many deaths, it is not known when this is going to end. It is an intern conflict of the country, between the same Colombians. There is warfare, the drug dealing war, the war between hired assassins; there are too many wars that are never over. It’s one of the most unsafe countries in the world, although it’s a beautiful country, I would ask anybody that hasn’t ever been there to visit it.”

“The presidents of my country are not quite… correct. They are all corrupt. So, it is very difficult to have justice when all the politicians are the same.”

“I don’t know, for example, here you just hear a fire gun, pof! And that’s it. In Colombia when people listen to a fire gun they know someone has been shooted. They just know someone is dead, you understand?”

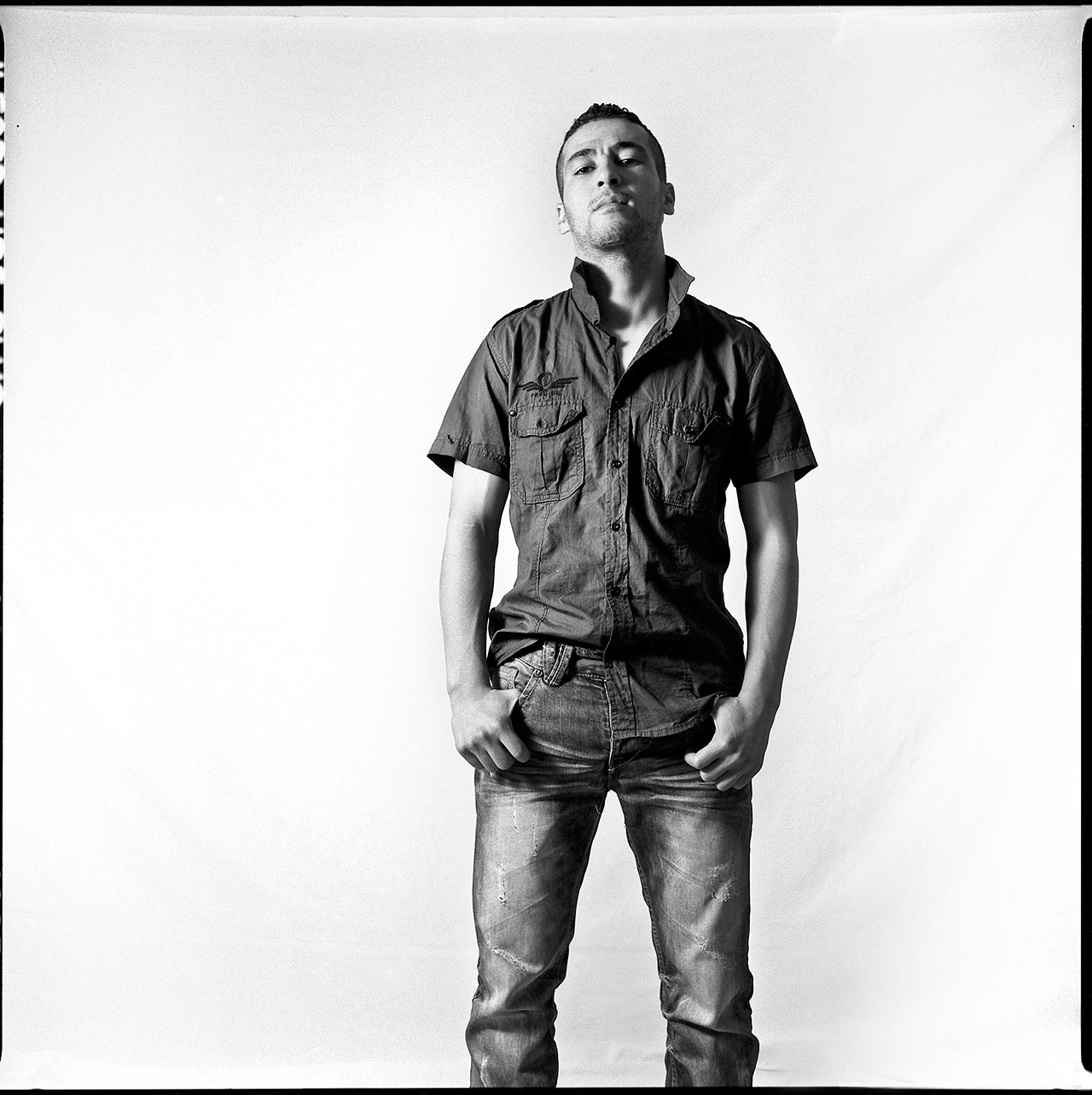

Samir went out from Alger, the biggest port in the north of Africa, almost ten years ago.

“I came inside of a van inside a ship. I arrived to Almería, I was a kid, and I got myself into of a youth centre and from there I have been in the same sort of places, youth centers (…) This country had a funny smell, seriously, nothing bad but weird, different than where I come from.”

“The memories I have are from when I was a little boy and I played with my friends of the neighborhood, my family (…) With some time I would definitely go back because it is my country, it is where I was born, where I have everything, where my people are. But not yet. I haven’t fixed my life here nor there, so, not until that happens. I have come here to do that, to create a life. I arrived when I was young and now it’s time for work. That is what I want.”

Andres abandoned Colombia when he was 10 years old. His last 10 years he has been in Catalunya.

“Well, I came here because of my mother; she had been here for about for years. She told me that life was going to… That life was going to be way better and that I would study and have everything I wanted, that I was going to have a much better future because the best things were here.”

“I miss everything. My family, the parties, the food, the women, the beaches. A little bit of everything. The culture and the atmosphere there is more cheerful.”

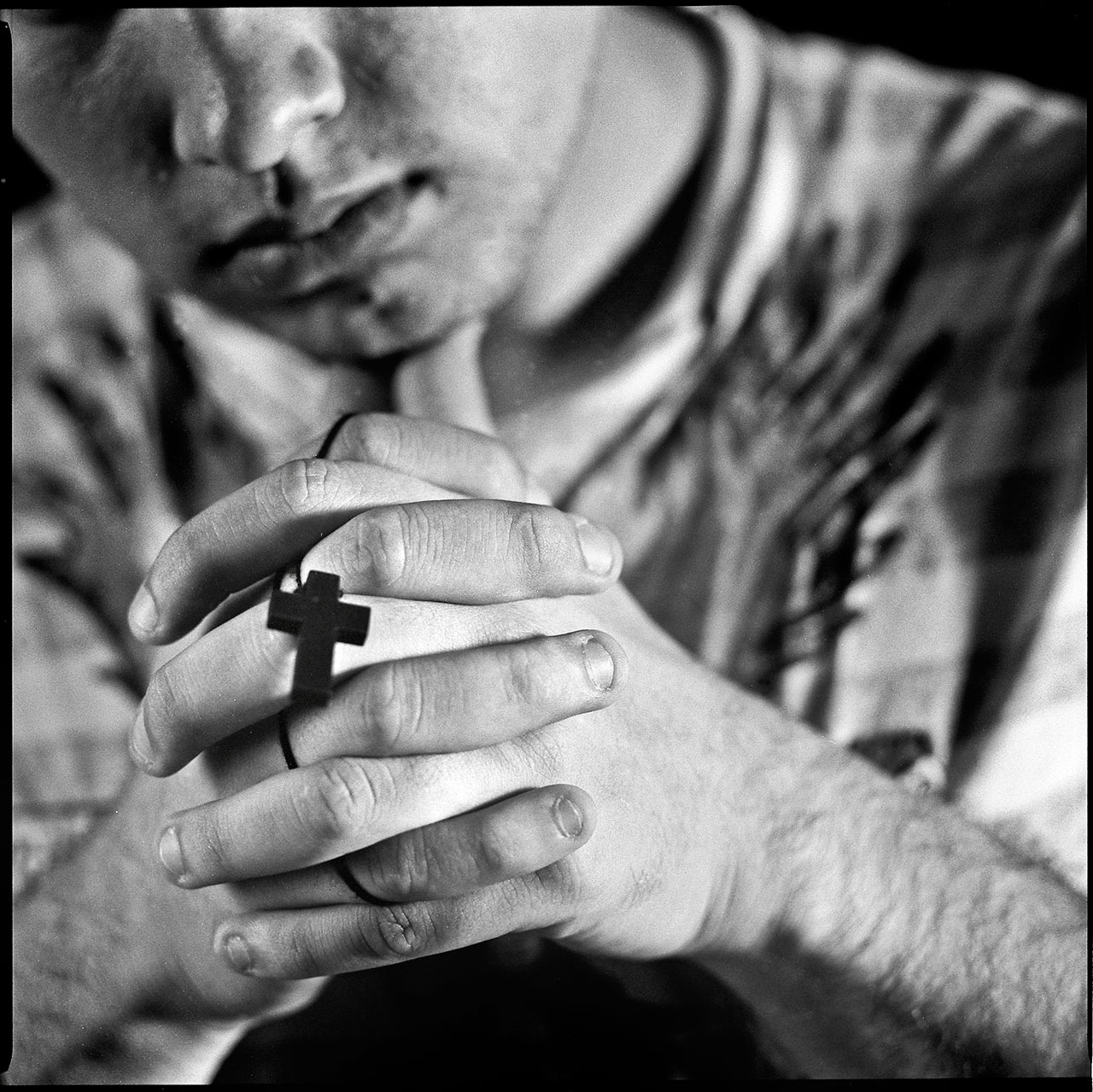

Albert is a 21-year-old prisoner born in Maresme, Premiá de Mar.

“I love my people. They will always help you. If you go to other places people don’t like this. (...) Ugh, my life there was a drift, I spent all day smoking and smoking... I wouldn’t stop from smoking and it was going out, but it was fantastic.”

“We would gather all in my house. Sometimes we were between 15 and 20 people in a room playing on the console and smoking. One day my father came and said: "What is this, a brothel or what?!" Everybody out! When people began to leave, he began to put his hand over the heads of the people and was counting 1 ... 2 ... 3 ... We fucked it big time, but I had a great time.”

“When you leave, you leave ... I will myself into a gardening course or nursing assistant, have a job and can save pennies in order to buy a house in the middle of the mountain. Live there, in the middle of nowhere and forget about people and be quieter.”

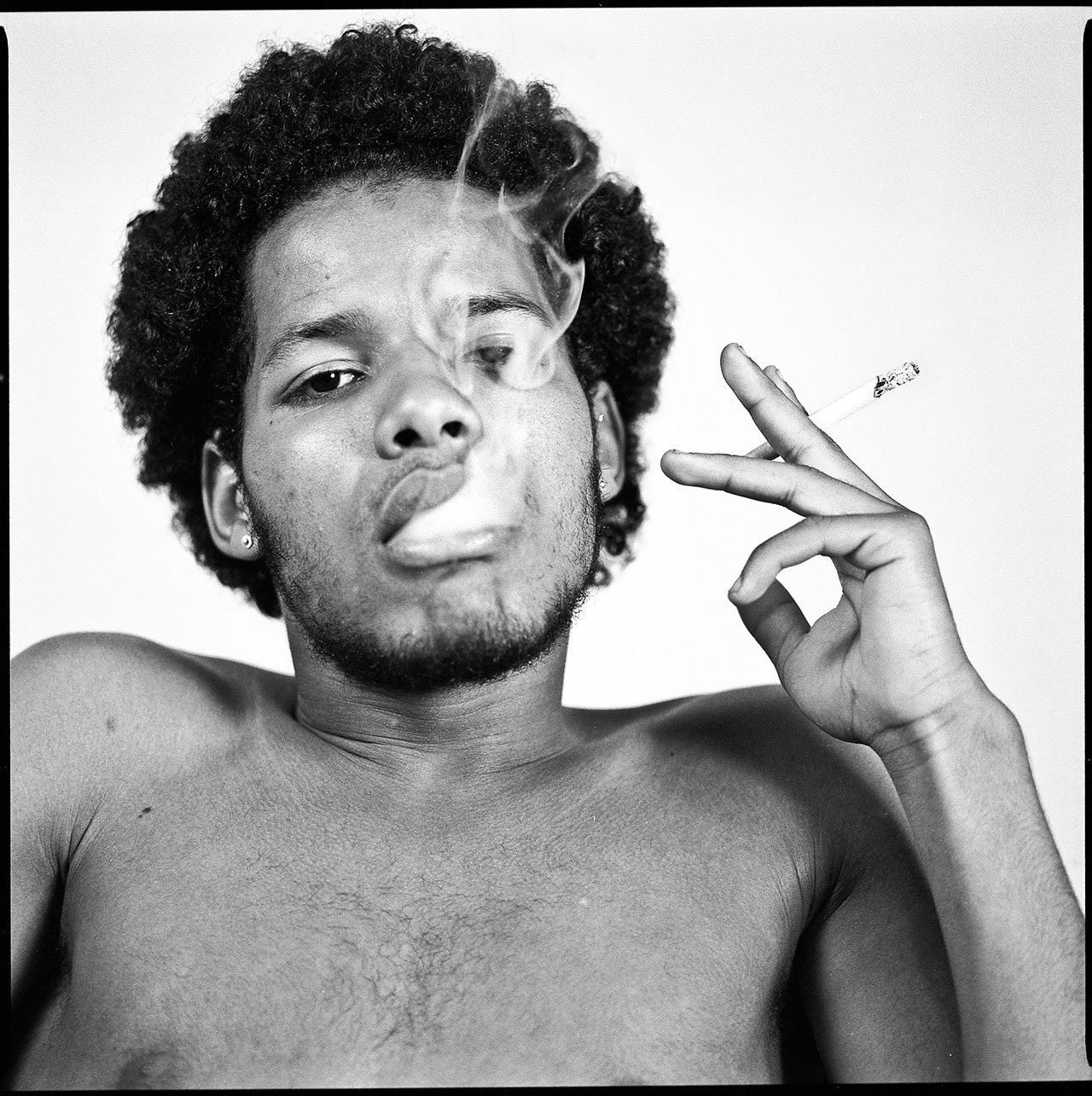

Silva was born in the north of Brazil although he was raised in Sao Paulo. He never intended to stay in this country.

“Destiny’s bad. I was to Turkey, well, actually I was going to Japan to give something I had and made a scale in Turkey. Coincidentally, I came here and something went wrong and here I am. Not because I want to, or I wanted to stay in Spain. I’m here due to my bad luck in life.”

“I can’t tell you my impression of Spain because I wasn’t in the street. For the moment, my impression is based on what I’ve seen here in jail. I thought it was very dangerous, like my country’s jails, that people kill each other. And no, totally different, everything is quite relaxed (…) When I arrived to Trinidad I had a problem with a Moroccan and I thought that I had to fight to death with him to gain respect. I had the mentality of my country, you know? And no, they just locked us into our cells and that was it. Very different from my country. I got into jail when I was 17 in a Youth Center and in my first fight they stabbed me. Then I did it back to gain respect. I had been there for only five months and I got stabbed, I blacked out and they took me to the nursery. All in five months!”

“You always go back from where you came from. It is clear; I’ve got a long way back, that is why I have to go back to my family, to my roots.”

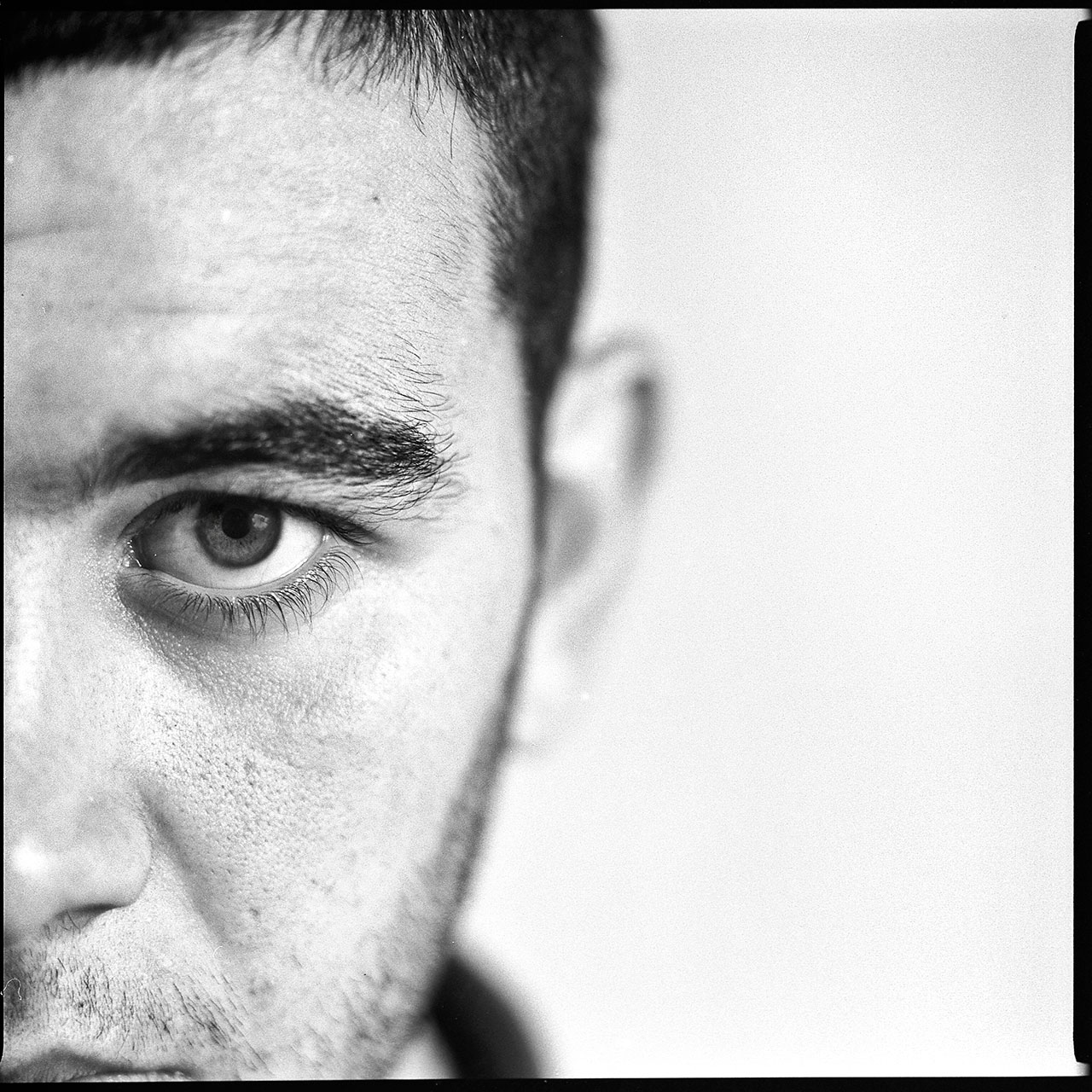

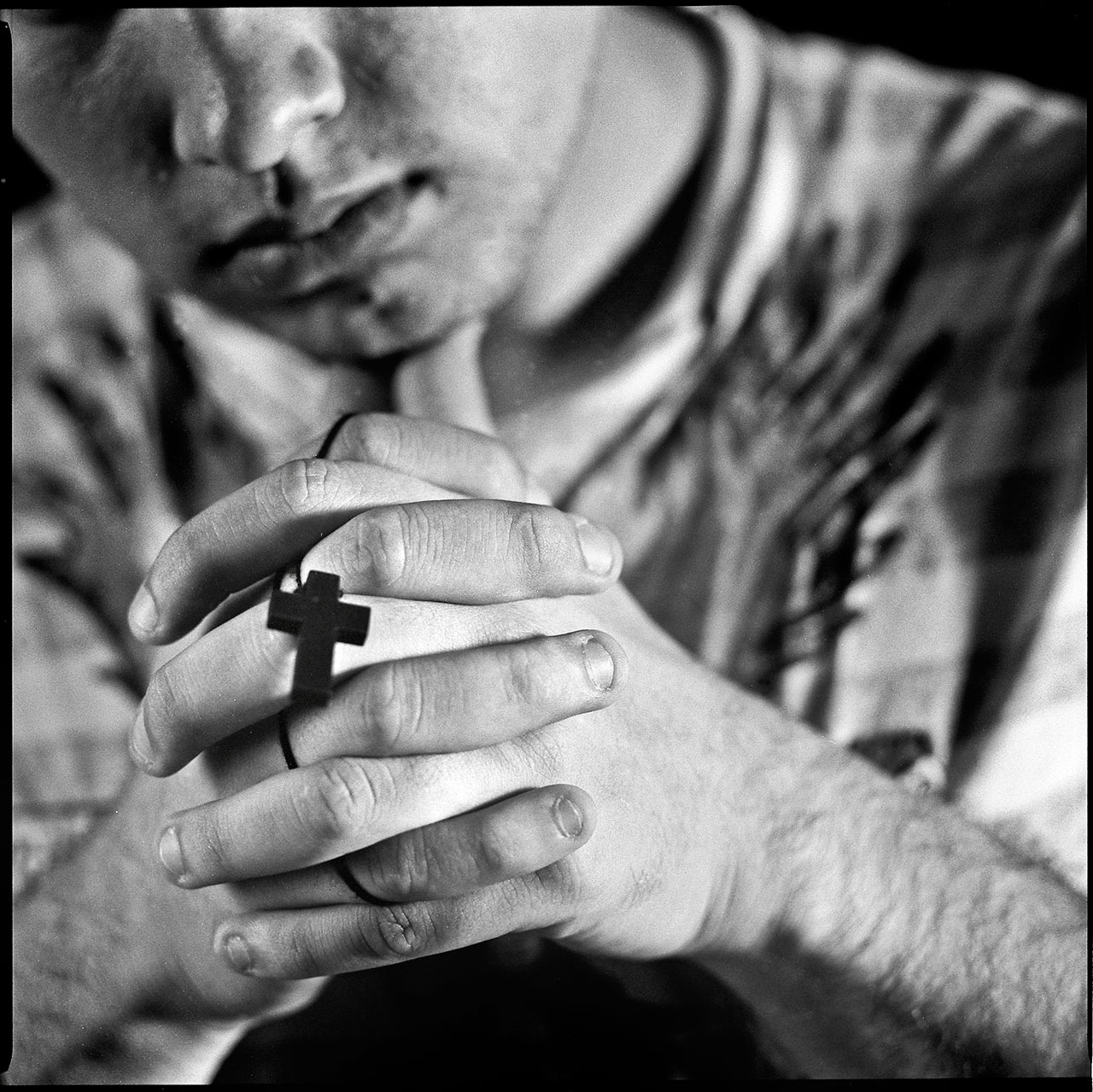

According to official data, 75% of the prisoners inside Catalunya Youth jail are migrants from outside of Europe. The other 25%, half are Europeans from outside the EU. Therefore, we found an overwhelming data in the Catalunya Youth jail: the 87.5 % of the prisoners are foreigners, coincidentally, the group with the less economical resources of our society.

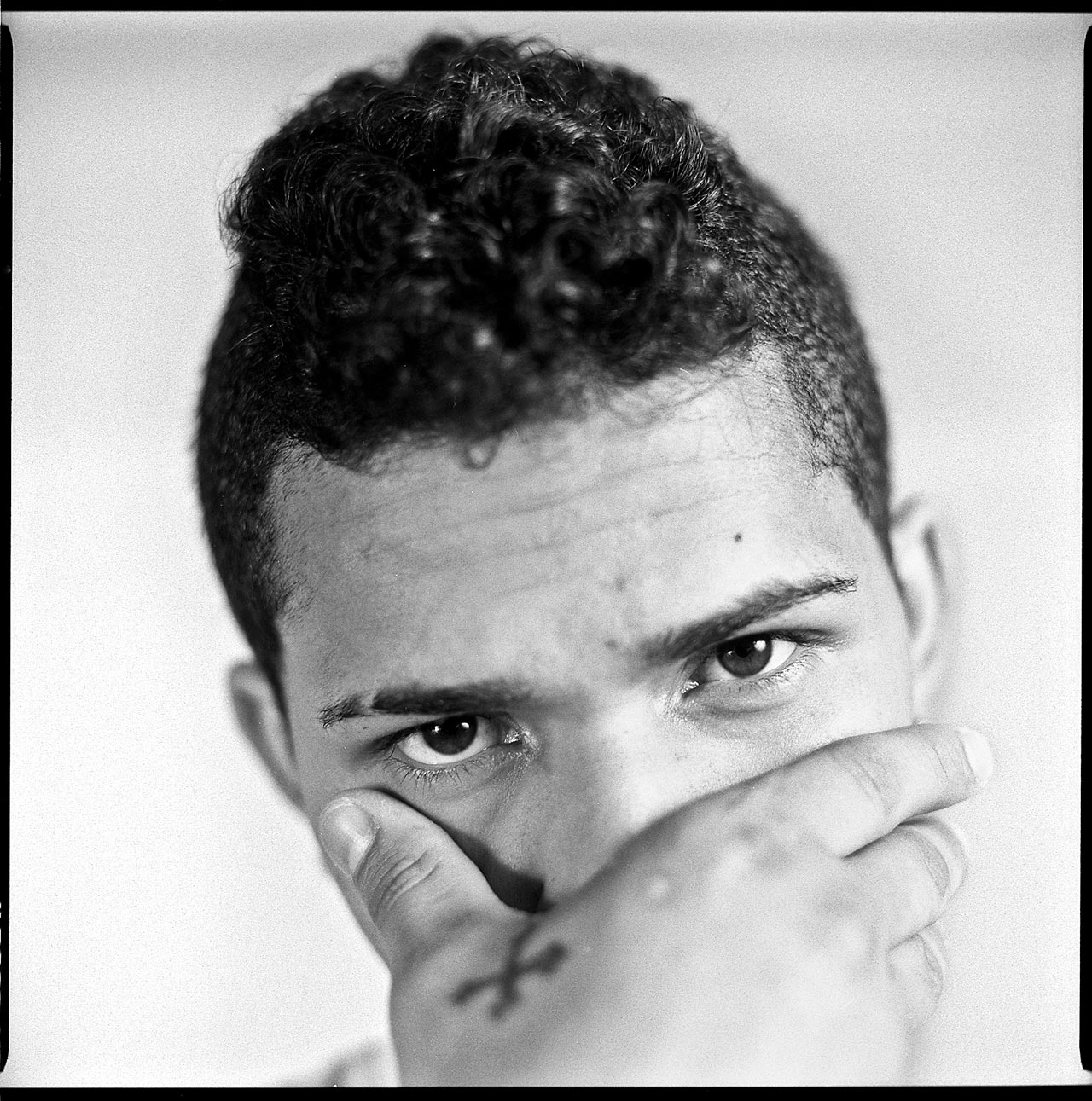

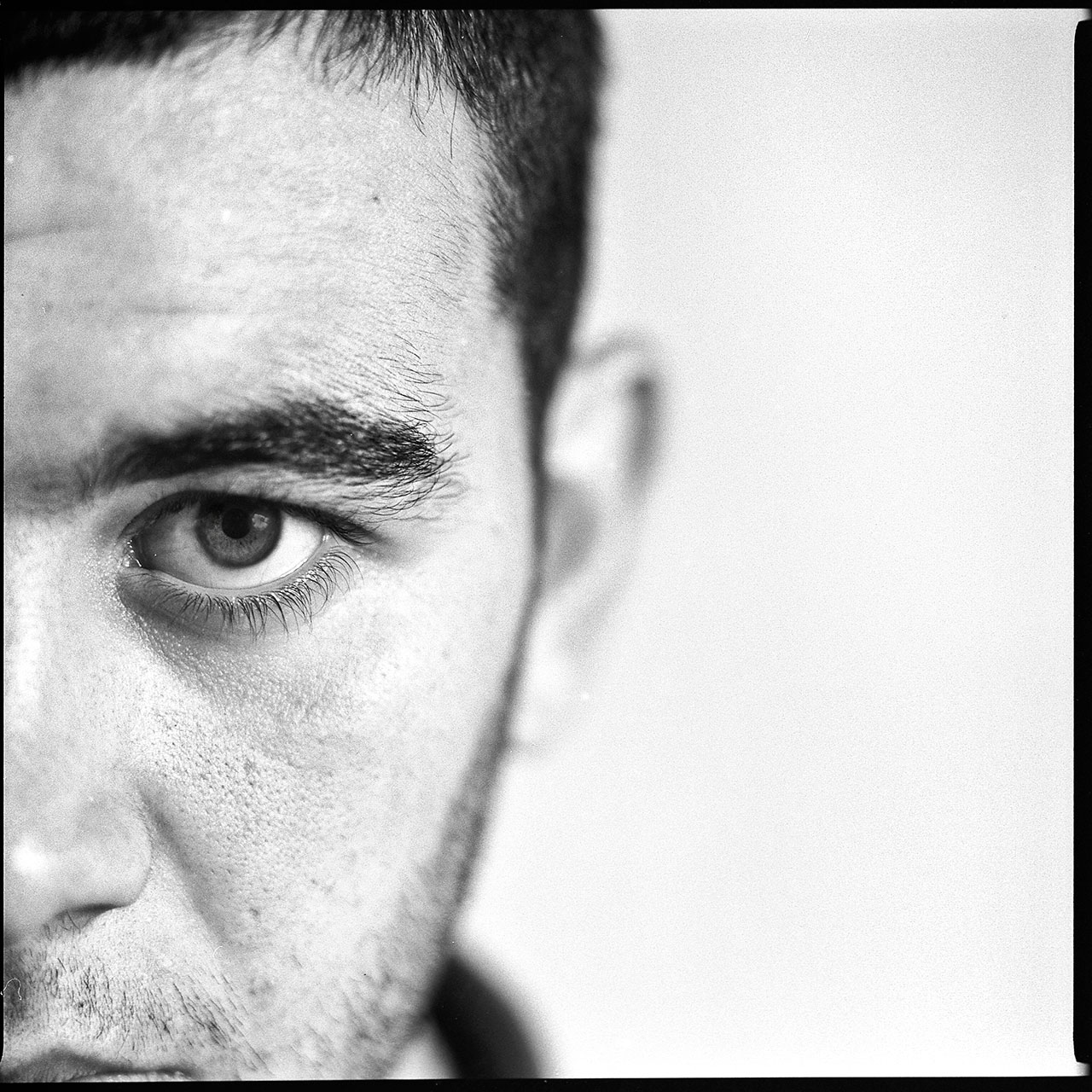

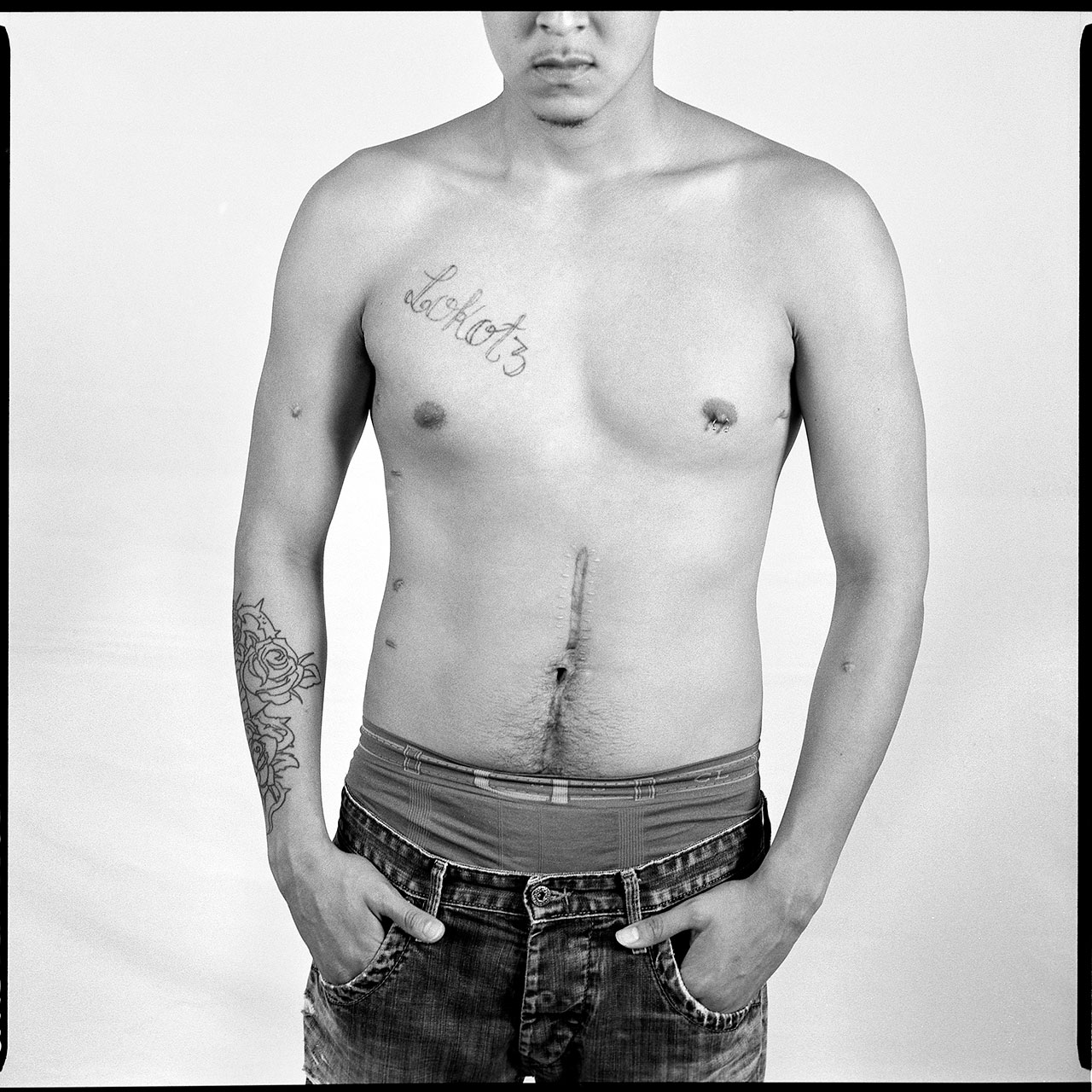

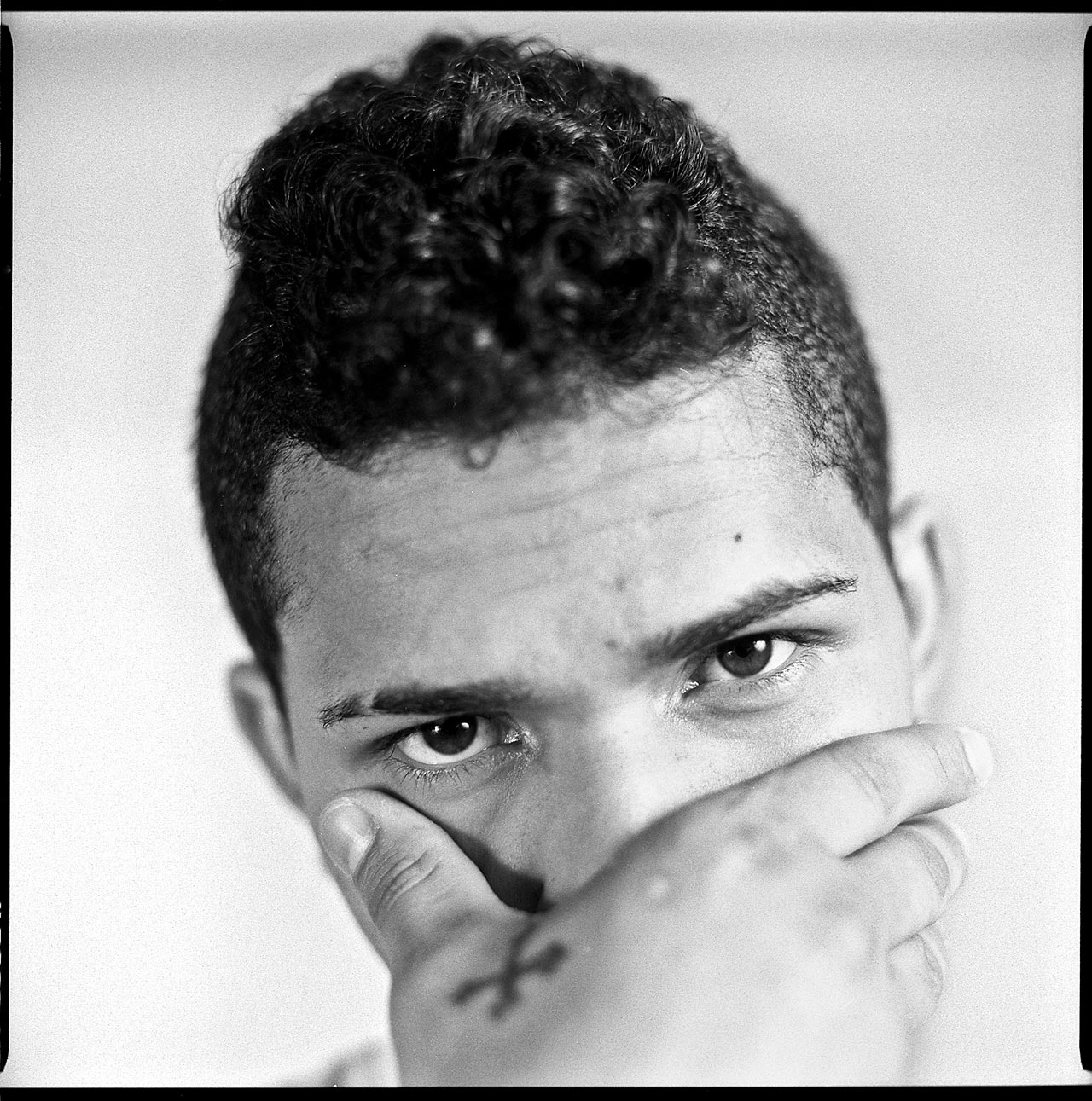

These images have no author. It is almost impossible to know who is the creator of each and every 6cm x 6cm negative. The process where the 12 photography sessions in which these images were made, from the outside may appear as a great chaos. Photographers took turns behind the Bronica camera, took two or three shots of prisoners with different backgrounds, and few seconds later a new eye appeared behind the lens. The rest of the group measured light, focused the lens, or gave posing ideas to the model. The session was over once the reel was full.

Making a portrait of half format project does no intend to be an exact replica of the Multiculturalism behind the walls of these jails. This project was just an excuse to join the youngsters from different roots in an improvised photography set and talk. Talk about their history, their journeys, their memories, and their lands. Testimonies that teach us that the world is not necessarily black and white, that there is no good or bad, and that luckily everything is more complex.

ACV. VCC. Albert, Charif, Ismael, Jaouad, Julián, Mahmoud, Moktar, Samir and Zaka know perfectly well how is the lifestyle in prison. They are between 18 and 23 years old and they are prisoners at the “Centre Penitenciari de jovenes de Catalunya”. They are the eight participants of the first edition of Visual Creation Classroom (VCC): In a period of seven months, they learnt how to use photography as a way of storytelling. The VCC intends to be a way to improve the social life amongst youngsters in prison as well as an improvement of their educational process..

ACV. VCC. Albert, Charif, Ismael, Jaouad, Julián, Mahmoud, Moktar, Samir and Zaka know perfectly well how is the lifestyle in prison. They are between 18 and 23 years old and they are prisoners at the “Centre Penitenciari de jovenes de Catalunya”. They are the eight participants of the first edition of Visual Creation Classroom (VCC): In a period of seven months, they learnt how to use photography as a way of storytelling. The VCC intends to be a way to improve the social life amongst youngsters in prison as well as an improvement of their educational process.. Ruido Photo (Barcelona, Spain, 2004) is an organization dedicated to produce and transmit documentary photography regarding Human Rights violations and major social issues. It gathers photographers, journalists and designers, who consider documentary as a tool for reflection and social transformation. It is a platform that opens its doors to receive independent documentary with strong social content and cultural commitment. It operates on four continents and focuses on three interrelated areas: Research and documentation; training and diffusion, and community revitalization practices.

Ruido Photo (Barcelona, Spain, 2004) is an organization dedicated to produce and transmit documentary photography regarding Human Rights violations and major social issues. It gathers photographers, journalists and designers, who consider documentary as a tool for reflection and social transformation. It is a platform that opens its doors to receive independent documentary with strong social content and cultural commitment. It operates on four continents and focuses on three interrelated areas: Research and documentation; training and diffusion, and community revitalization practices.The next photos and videos are the result of leaving a photo and a video camera on the top of a table while making the 12x12. Migration and Jails project. Any resident who had some free time and felt like documenting his surroundings, could grab a camera and feel free to do it without any kind of pretension.

The result is these images that illustrate some moments of the creation process inside a prison. In a makeshift photography set, inside the only casually empty room of the Catalunya Youth Prison school, prisoners themselves decided to create a psychological portrait series of residents that had different geographical roots to show that almost 90% of them were migrants.

HHamza has been for almost three years in Catalunya, he comes from Alger, the capital of Algeria.

"Truth be told, I don’t know how much longer I am going to stay here, it is all up to fate. I could go now or I could stay until… I don’t know, I truly don’t know."

"The thing that made me migrate is that I wanted to change. I wanted to change myself. I was in the wrong path and I wanted to change my ways, my friends, a little of everything because I was in the wrong path. (…) I came here all over from Marsella in train. I went out to the boardwalk and it was a Friday night, everyone was there, there was a party and some other things. I thought to myself “Wow” I thought it was amazing…"

"Of course I would go back to my country but not yet. I’ve got everything in there, family, is my land, my country, and I’ve got to be there. I have to be buried in Argelia, you know?"

Gerson is a youngster from Guatemala City. He started working as a model and interiorist but in order to grow he had to move to another country.

“I left my country because you can’t grow over there, the country is extremely poor and you just can’t. I think here, asking for help, you could get ahead (…) I didn’t come as a migrant because I had all my papers in order, I came here by plane and everything was going just fine, too fine (…) I only miss my family, but one must make sacrifices to get ahead so that is why I’m here.”

“I chose Spain because in the United States they keep an eye on migrants and it is harder to be there. My future here is look for a job, seek for ways to improve my life and bring my family here.”

Julian comes from the little city of Dosquebradas, one of the principal industrial core from Colombia.

“The truth is that the place where I come from is very dangerous, I kept myself involved in odd things and they were going to kill me. That’s why I moved here (…) I have been in Catalunya for two or three years and a year and a half locked. I do not know how much longer will I stay here. I’ll see what I do once I’m out.”

“Uf! What I remember the most of my country is my people, my family, my brothers and the party. Uy! Is what I remember the most. I would not think it twice, I would go back because all my family is there and danger is gone. I miss Colombia a lot, of course I would go back…”

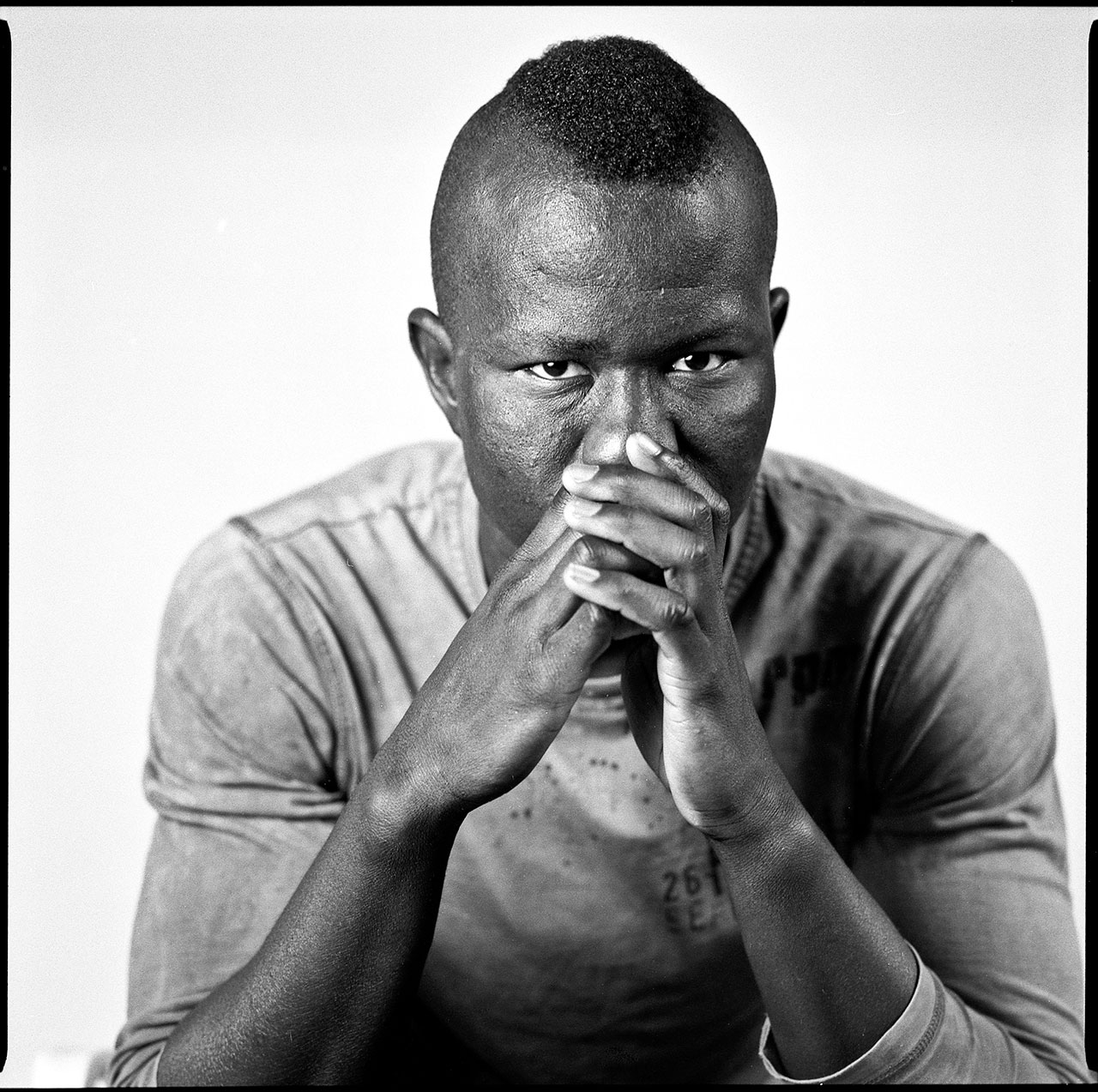

Mahmoud was born in Dakar, capital of Senegal. He has been in Catalunya for six years.

“I changed of country for many reasons. I though that once I get into Spain I could get some money, help my family, these kind of things (…) I arrived in ship from Mauritania to Tenerife. When I arrived some people took care of me because I was underage, I was 16, and they put me in a youth centre until I was 18. (…) I arrived to Europe to get a job, earn some money to help my family, to change their lives and the hard way they live right now there. That is what I thought…”

“We were 93 people in a ship that wasn’t big. It took us 6 days to get to Tenerife. I had never been in the sea, I continuously kept throwing up and dizzy. There were some people that were on the verge of dying but everyone arrived alive. (…) I though that it was a ship not a canoe. When I paid the money they told me it was a ship and I paid 1200 euros.”

“I saw many people that lived in Europe for 5 yeas and then they went back to my country and they had a house, a car, and then I think: How do these people got the money? I have been 20 years working and I just can’t anything, not even a house. Let’s see how is Europe.”

Ismael was born in the capital of Ecuador, Quito. But he has been in Hospitalet city for nine years.

“My mom took me here when I was little, I didn’t know anything, and now, here I am. (…) Right now I wouldn’t go to my country, if I ever go back is going to be for holidays. I would go back once I’m older, to die there and remain there always.”

“When I arrived here nothing seemed easy. I saw my mother working, working quite a lot, and she still does it. And no, as a child I didn’t see life and street as easy things. (…) I always lived in Hospitalet, my neighborhood was very problematic but as every neighborhood it has its good qualities. (…) I remember myself being at school and they picked up someone and started throwing bottles to him, he couldn’t go further from the entrance door, everyone was throwing bottles to him from there…”

Yassine doesn’t speak Spanish. He has only been in Catalunya for three months. His story of how life took him to Europe is the most singular story we found in this project.

Everyone calls him Sáhara. He was born in Dajla, the capital of a province of an old Spanish cologne of the Western Sahara. Today it is occupied by Morocco.

Against his willing, when Yassine was 15 years old, he went to Morocco to do his higher studies, but his support to the Sahara’s independence generate him a series of troubles with the authorities and was locked for 8 months in a Moroccan jail. When he finally achieved his freedom, his family did everything they could to expel him from the country until get, previously paid, a fake visa to go to Europe.

Romeo is Dominican but almost his entire life he has been in Spain.

“I came here when I was eight years old. I couldn’t decide where to go, my mother brought me. I have been here in Catalunya for 11 years, and the truth is, I didn’t think about the time I was going to stay…”

“I miss my entire country, specially the food. Rice with bandule, coco milk and cutlet… or the “Dominican flag”, rice with beans and meat (…)In the Dominican Republic, there are some people that have almost no money; and there are some others that have a great, great time.”

Edwin came to Spain for holidays in 2001. He came to visit his mother and never went back to Colombia.

“I was born in Colombia. My parents came to Spain when I was little and that is the reason I came (…) I thought that Spain was bigger, richer. It wasn’t heaven, but when you arrive here everything is different, you know?, You have to get used to a new culture, a new way of living. Everything is stranger but little by little you adapt yourself. (…) Colombia is very poor but the people are happier and fine with the things they have, they are very humble.”

“Too many deaths, it is not known when this is going to end. It is an intern conflict of the country, between the same Colombians. There is warfare, the drug dealing war, the war between hired assassins; there are too many wars that are never over. It’s one of the most unsafe countries in the world, although it’s a beautiful country, I would ask anybody that hasn’t ever been there to visit it.”

“The presidents of my country are not quite… correct. They are all corrupt. So, it is very difficult to have justice when all the politicians are the same.”

“I don’t know, for example, here you just hear a fire gun, pof! And that’s it. In Colombia when people listen to a fire gun they know someone has been shooted. They just know someone is dead, you understand?”

Samir went out from Alger, the biggest port in the north of Africa, almost ten years ago.

“I came inside of a van inside a ship. I arrived to Almería, I was a kid, and I got myself into of a youth centre and from there I have been in the same sort of places, youth centers (…) This country had a funny smell, seriously, nothing bad but weird, different than where I come from.”

“The memories I have are from when I was a little boy and I played with my friends of the neighborhood, my family (…) With some time I would definitely go back because it is my country, it is where I was born, where I have everything, where my people are. But not yet. I haven’t fixed my life here nor there, so, not until that happens. I have come here to do that, to create a life. I arrived when I was young and now it’s time for work. That is what I want.”

Andres abandoned Colombia when he was 10 years old. His last 10 years he has been in Catalunya.

“Well, I came here because of my mother; she had been here for about for years. She told me that life was going to… That life was going to be way better and that I would study and have everything I wanted, that I was going to have a much better future because the best things were here.”

“I miss everything. My family, the parties, the food, the women, the beaches. A little bit of everything. The culture and the atmosphere there is more cheerful.”

Albert is a 21-year-old prisoner born in Maresme, Premiá de Mar.

“I love my people. They will always help you. If you go to other places people don’t like this. (...) Ugh, my life there was a drift, I spent all day smoking and smoking... I wouldn’t stop from smoking and it was going out, but it was fantastic.”

“We would gather all in my house. Sometimes we were between 15 and 20 people in a room playing on the console and smoking. One day my father came and said: "What is this, a brothel or what?!" Everybody out! When people began to leave, he began to put his hand over the heads of the people and was counting 1 ... 2 ... 3 ... We fucked it big time, but I had a great time.”

“When you leave, you leave ... I will myself into a gardening course or nursing assistant, have a job and can save pennies in order to buy a house in the middle of the mountain. Live there, in the middle of nowhere and forget about people and be quieter.”

Silva was born in the north of Brazil although he was raised in Sao Paulo. He never intended to stay in this country.

“Destiny’s bad. I was to Turkey, well, actually I was going to Japan to give something I had and made a scale in Turkey. Coincidentally, I came here and something went wrong and here I am. Not because I want to, or I wanted to stay in Spain. I’m here due to my bad luck in life.”

“I can’t tell you my impression of Spain because I wasn’t in the street. For the moment, my impression is based on what I’ve seen here in jail. I thought it was very dangerous, like my country’s jails, that people kill each other. And no, totally different, everything is quite relaxed (…) When I arrived to Trinidad I had a problem with a Moroccan and I thought that I had to fight to death with him to gain respect. I had the mentality of my country, you know? And no, they just locked us into our cells and that was it. Very different from my country. I got into jail when I was 17 in a Youth Center and in my first fight they stabbed me. Then I did it back to gain respect. I had been there for only five months and I got stabbed, I blacked out and they took me to the nursery. All in five months!”

“You always go back from where you came from. It is clear; I’ve got a long way back, that is why I have to go back to my family, to my roots.”

According to official data, 75% of the prisoners inside Catalunya Youth jail are migrants from outside of Europe. The other 25%, half are Europeans from outside the EU. Therefore, we found an overwhelming data in the Catalunya Youth jail: the 87.5 % of the prisoners are foreigners, coincidentally, the group with the less economical resources of our society.

These images have no author. It is almost impossible to know who is the creator of each and every 6cm x 6cm negative. The process where the 12 photography sessions in which these images were made, from the outside may appear as a great chaos. Photographers took turns behind the Bronica camera, took two or three shots of prisoners with different backgrounds, and few seconds later a new eye appeared behind the lens. The rest of the group measured light, focused the lens, or gave posing ideas to the model. The session was over once the reel was full.

Making a portrait of half format project does no intend to be an exact replica of the Multiculturalism behind the walls of these jails. This project was just an excuse to join the youngsters from different roots in an improvised photography set and talk. Talk about their history, their journeys, their memories, and their lands. Testimonies that teach us that the world is not necessarily black and white, that there is no good or bad, and that luckily everything is more complex.

ACV. VCC. Albert, Charif, Ismael, Jaouad, Julián, Mahmoud, Moktar, Samir and Zaka know perfectly well how is the lifestyle in prison. They are between 18 and 23 years old and they are prisoners at the “Centre Penitenciari de jovenes de Catalunya”. They are the eight participants of the first edition of Visual Creation Classroom (VCC): In a period of seven months, they learnt how to use photography as a way of storytelling. The VCC intends to be a way to improve the social life amongst youngsters in prison as well as an improvement of their educational process..

ACV. VCC. Albert, Charif, Ismael, Jaouad, Julián, Mahmoud, Moktar, Samir and Zaka know perfectly well how is the lifestyle in prison. They are between 18 and 23 years old and they are prisoners at the “Centre Penitenciari de jovenes de Catalunya”. They are the eight participants of the first edition of Visual Creation Classroom (VCC): In a period of seven months, they learnt how to use photography as a way of storytelling. The VCC intends to be a way to improve the social life amongst youngsters in prison as well as an improvement of their educational process.. Ruido Photo (Barcelona, Spain, 2004) is an organization dedicated to produce and transmit documentary photography regarding Human Rights violations and major social issues. It gathers photographers, journalists and designers, who consider documentary as a tool for reflection and social transformation. It is a platform that opens its doors to receive independent documentary with strong social content and cultural commitment. It operates on four continents and focuses on three interrelated areas: Research and documentation; training and diffusion, and community revitalization practices.

Ruido Photo (Barcelona, Spain, 2004) is an organization dedicated to produce and transmit documentary photography regarding Human Rights violations and major social issues. It gathers photographers, journalists and designers, who consider documentary as a tool for reflection and social transformation. It is a platform that opens its doors to receive independent documentary with strong social content and cultural commitment. It operates on four continents and focuses on three interrelated areas: Research and documentation; training and diffusion, and community revitalization practices.The next photos and videos are the result of leaving a photo and a video camera on the top of a table while making the 12x12. Migration and Jails project. Any resident who had some free time and felt like documenting his surroundings, could grab a camera and feel free to do it without any kind of pretension.

The result is these images that illustrate some moments of the creation process inside a prison. In a makeshift photography set, inside the only casually empty room of the Catalunya Youth Prison school, prisoners themselves decided to create a psychological portrait series of residents that had different geographical roots to show that almost 90% of them were migrants.

Ehekatl Hernández

The question is, what is the function of competitions and calls for submissions of activist, documentary or collaborative photography? There are countless initiatives with discourses calling for justice, change and equality, with excellent intentions and attempts to “give a presence to the least fortunate persons worldwide”, with a proposal that stifles these communities’ capacity to represent themselves, or construct their own imagination from the trenches, ghettos, neighborhoods or shanty towns.

The apparent contradiction of these initiatives is reflected in irregular results, often selected solely for their aesthetic value, which undoubtedly reflects the vision, perspective and conceptual and formal decisions of an author. In this regard, it is naïve to seek to “reflect reality”, and it is perhaps worth reconsidering the uses of photography to represent and document from other perspectives, the sum of which approaches offers a more reliable record, and must be completed by a vision from within the communities themselves. After all, it is the individuals immersed in them who experience most closely their own dynamics and value systems, and the aspects of greatest interest to them.

This does not mean that being external makes a vision invalid or unworthy. On the contrary, the reflection proposes that a register be adopted that involves the photographer more actively. Therefore, all these calls for submissions, competitions and participative initiatives, as well as photographers and producers, must distance themselves from traditional documentalism. The context of the individual or community photographed must be understood and assimilated by offering an interpretation that presents the authorial contribution and its specific approach to the topic, thus establishing an authentic dialogue, a means of integration, a to-ing and fro-ing, and ultimately a better understanding of the subject photographed and his environment. Indeed, the greatest value lies in experience and the dialogue established, always assuming that the final result is merely the interpretation and assimilation of this experience, rather than a distant discourse outside the community documented.

This poses a challenge to the entire system of values, conception, production and consumption of documentary photography, and though this idea has already been applied in photojournalism for several decades, it questions the validity of these reflections and criticism in an era in which technology is rethinking all photographic activity. Today, communities are representing themselves as never before thanks to the availability of capture devices and the almost immediate spread and distribution of images, as a first-hand record that is unintentionally documenting events in specific environments in every corner of the world from various angles. Undoubtedly, these competitions and calls for submissions will gradually increase in scope and number, although paradoxically, their selection criteria and consequently, objectives, are increasingly being questioned. Neither renown nor tradition exempts these initiatives from these new reflections and questioning, with targets ranging from the prestigious World Press Photo to modest announcements by NGOs, academic institutions or civil organizations.

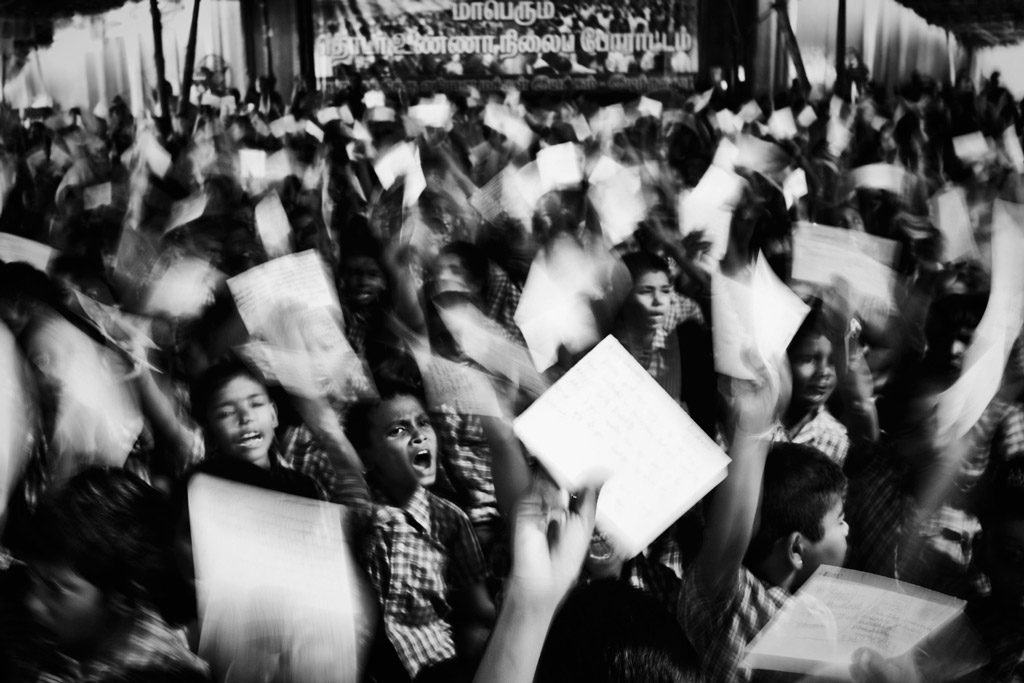

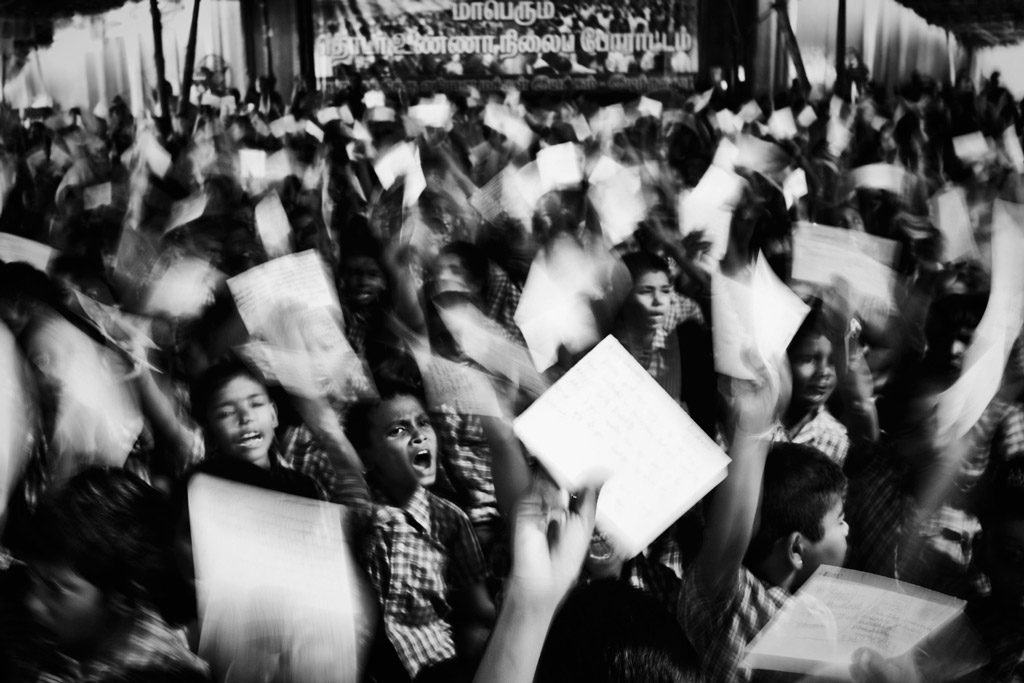

Children from Idinthakarai. Amirtharaj Stephen

This phenomenon does not diminish the importance of those initiatives in which the resources obtained from scholarships and prizes contribute directly to financing NGOs, social organizations and charities, and the management of these funds reflects other spheres. Moreover, there is a clearly-defined market for these projects, whose results correspond perfectly to the particular needs of various governments and official institutions but also social institutions and the public that consumes these images. In any case, what is questionable is the banner under which these works are disseminated, with the false premise of giving a face to the oppressed. This raises the same question: who is being represented, and why? Failing this, do these communities genuinely want to be represented in this manner?

However, we can afford to be optimistic, since several organizations have gradually begun toask themselves these questions, and are redefining their objectives and selection criteria. New participation dynamics for documentary makers and journalists are being established, which record and document the circumstances of their own environments. One example is CatchLigth (formerly Photo Philantropy) a platform for building ties based in California, which goes beyond being a renowned annual prize for photographic activism, basing its selection criteria mainly on the narrative value of the work, while also supporting the directors of audiovisual projects with social content through a system of liaisons with technological sponsors for the production and dissemination of the works produced.

Thus, given this outlook, we may be closer to obtaining an answer to the initial questioning process, which suggests that the true contribution and function of these events and calls for submissions should be to bring together all these points of view, to construct a broader experience based on a three-dimensional record approached from all angles, as is done by Donald Weber and its questioning of the crisis of photojournalism and documentalism. To achieve this new point of view, the objectivity once so zealously pursued must cease to be the canon on which to base the selection and judgment criteria of social competitions and calls for submissions, in order to achieve a closer approximation and better understanding of these other realities.

Dmitry Chizhevskiy, 27, had his left eye permanently destroyed by homophobes - Mads Nissen

Ehekatl Hernández (México, 1975) received a Bachelor’s Degree in Graphic Design from the Escuela Nacional de Artes Plásticas at UNAM in Mexico, and a Master’s Degree in Multimedia Applications from the Universidad Poltécnica de Catalunya in Spain. He has over 15 years’ experience in graphic design and planning, developing and implementing web projects. Hernández has given diploma courses in web design at UNAM. He has spent nine years contributing to the web design and multimedia area at zonezero.com, and also works as a consultant for various companies as well as coordinating the e-learning system of the Virtual Campus of the Pedro Meyer Foundation.

Ehekatl Hernández (México, 1975) received a Bachelor’s Degree in Graphic Design from the Escuela Nacional de Artes Plásticas at UNAM in Mexico, and a Master’s Degree in Multimedia Applications from the Universidad Poltécnica de Catalunya in Spain. He has over 15 years’ experience in graphic design and planning, developing and implementing web projects. Hernández has given diploma courses in web design at UNAM. He has spent nine years contributing to the web design and multimedia area at zonezero.com, and also works as a consultant for various companies as well as coordinating the e-learning system of the Virtual Campus of the Pedro Meyer Foundation.[core_state] => 1 [core_access] => 1 [core_metadata] => {"robots":"","author":"Ehekatl Hern\u00e1ndez","rights":"","xreference":""} [core_created_user_id] => 841 [core_created_by_alias] => [core_created_time] => 2015-08-10 19:46:15 [core_images] => {"image_intro":"images\/categories\/collective-representation\/fotocolaborativa.jpg","float_intro":"","image_intro_alt":"","image_intro_caption":"","image_fulltext":"images\/categories\/collective-representation\/fotocolaborativa.jpg","float_fulltext":"","image_fulltext_alt":"","image_fulltext_caption":""} [core_modified_time] => 2018-06-29 16:38:29 [core_language] => en-GB [core_catid] => 59 [core_publish_up] => 2015-08-10 19:46:15 [core_publish_down] => 0000-00-00 00:00:00 [content_type_title] => Article [router] => ContentHelperRoute::getArticleRoute [author] => [author_email] => [link] => index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=316:activist-documentary-and-collaborative-photography&catid=59&lang=en-GB [displayDate] => 2015-08-10 19:46:15 [event] => stdClass Object ( [afterDisplayTitle] => [beforeDisplayContent] => [afterDisplayContent] => ) [text] =>

The question is, what is the function of competitions and calls for submissions of activist, documentary or collaborative photography? There are countless initiatives with discourses calling for justice, change and equality, with excellent intentions and attempts to “give a presence to the least fortunate persons worldwide”, with a proposal that stifles these communities’ capacity to represent themselves, or construct their own imagination from the trenches, ghettos, neighborhoods or shanty towns.

The apparent contradiction of these initiatives is reflected in irregular results, often selected solely for their aesthetic value, which undoubtedly reflects the vision, perspective and conceptual and formal decisions of an author. In this regard, it is naïve to seek to “reflect reality”, and it is perhaps worth reconsidering the uses of photography to represent and document from other perspectives, the sum of which approaches offers a more reliable record, and must be completed by a vision from within the communities themselves. After all, it is the individuals immersed in them who experience most closely their own dynamics and value systems, and the aspects of greatest interest to them.

This does not mean that being external makes a vision invalid or unworthy. On the contrary, the reflection proposes that a register be adopted that involves the photographer more actively. Therefore, all these calls for submissions, competitions and participative initiatives, as well as photographers and producers, must distance themselves from traditional documentalism. The context of the individual or community photographed must be understood and assimilated by offering an interpretation that presents the authorial contribution and its specific approach to the topic, thus establishing an authentic dialogue, a means of integration, a to-ing and fro-ing, and ultimately a better understanding of the subject photographed and his environment. Indeed, the greatest value lies in experience and the dialogue established, always assuming that the final result is merely the interpretation and assimilation of this experience, rather than a distant discourse outside the community documented.

This poses a challenge to the entire system of values, conception, production and consumption of documentary photography, and though this idea has already been applied in photojournalism for several decades, it questions the validity of these reflections and criticism in an era in which technology is rethinking all photographic activity. Today, communities are representing themselves as never before thanks to the availability of capture devices and the almost immediate spread and distribution of images, as a first-hand record that is unintentionally documenting events in specific environments in every corner of the world from various angles. Undoubtedly, these competitions and calls for submissions will gradually increase in scope and number, although paradoxically, their selection criteria and consequently, objectives, are increasingly being questioned. Neither renown nor tradition exempts these initiatives from these new reflections and questioning, with targets ranging from the prestigious World Press Photo to modest announcements by NGOs, academic institutions or civil organizations.

Children from Idinthakarai. Amirtharaj Stephen

This phenomenon does not diminish the importance of those initiatives in which the resources obtained from scholarships and prizes contribute directly to financing NGOs, social organizations and charities, and the management of these funds reflects other spheres. Moreover, there is a clearly-defined market for these projects, whose results correspond perfectly to the particular needs of various governments and official institutions but also social institutions and the public that consumes these images. In any case, what is questionable is the banner under which these works are disseminated, with the false premise of giving a face to the oppressed. This raises the same question: who is being represented, and why? Failing this, do these communities genuinely want to be represented in this manner?

However, we can afford to be optimistic, since several organizations have gradually begun toask themselves these questions, and are redefining their objectives and selection criteria. New participation dynamics for documentary makers and journalists are being established, which record and document the circumstances of their own environments. One example is CatchLigth (formerly Photo Philantropy) a platform for building ties based in California, which goes beyond being a renowned annual prize for photographic activism, basing its selection criteria mainly on the narrative value of the work, while also supporting the directors of audiovisual projects with social content through a system of liaisons with technological sponsors for the production and dissemination of the works produced.

Thus, given this outlook, we may be closer to obtaining an answer to the initial questioning process, which suggests that the true contribution and function of these events and calls for submissions should be to bring together all these points of view, to construct a broader experience based on a three-dimensional record approached from all angles, as is done by Donald Weber and its questioning of the crisis of photojournalism and documentalism. To achieve this new point of view, the objectivity once so zealously pursued must cease to be the canon on which to base the selection and judgment criteria of social competitions and calls for submissions, in order to achieve a closer approximation and better understanding of these other realities.

Dmitry Chizhevskiy, 27, had his left eye permanently destroyed by homophobes - Mads Nissen

Ehekatl Hernández (México, 1975) received a Bachelor’s Degree in Graphic Design from the Escuela Nacional de Artes Plásticas at UNAM in Mexico, and a Master’s Degree in Multimedia Applications from the Universidad Poltécnica de Catalunya in Spain. He has over 15 years’ experience in graphic design and planning, developing and implementing web projects. Hernández has given diploma courses in web design at UNAM. He has spent nine years contributing to the web design and multimedia area at zonezero.com, and also works as a consultant for various companies as well as coordinating the e-learning system of the Virtual Campus of the Pedro Meyer Foundation.

Ehekatl Hernández (México, 1975) received a Bachelor’s Degree in Graphic Design from the Escuela Nacional de Artes Plásticas at UNAM in Mexico, and a Master’s Degree in Multimedia Applications from the Universidad Poltécnica de Catalunya in Spain. He has over 15 years’ experience in graphic design and planning, developing and implementing web projects. Hernández has given diploma courses in web design at UNAM. He has spent nine years contributing to the web design and multimedia area at zonezero.com, and also works as a consultant for various companies as well as coordinating the e-learning system of the Virtual Campus of the Pedro Meyer Foundation.[id] => 316 [language] => en-GB [catid] => 59 [jcfields] => Array ( ) ) 1

Elisa Rugo

One of the greatest advantages of current photography, through its democratization as a tool and the technological advances in the media, is the guiding thread it establishes for collective representations in visual communication. This is largely the result of databases generated using key words, which provide information by describing and facilitating the identification of files and content. One of the most effective uses of this is the ubiquitous hashtag in social networks (Twitter, Instagram, Tumblr, FB). Eight years after Messina1 using the hashtag to group dialogues in social networks, this resource has produced endless possibilities not only for political and commercial marketing campaigns, but also for categorizing and linking information in a virtual world with millions of simultaneous thematic connections. It has served to increase the understanding of communities that would otherwise be hard to reach, which documentary photographers wish to comprehend and stop portraying from a distance.

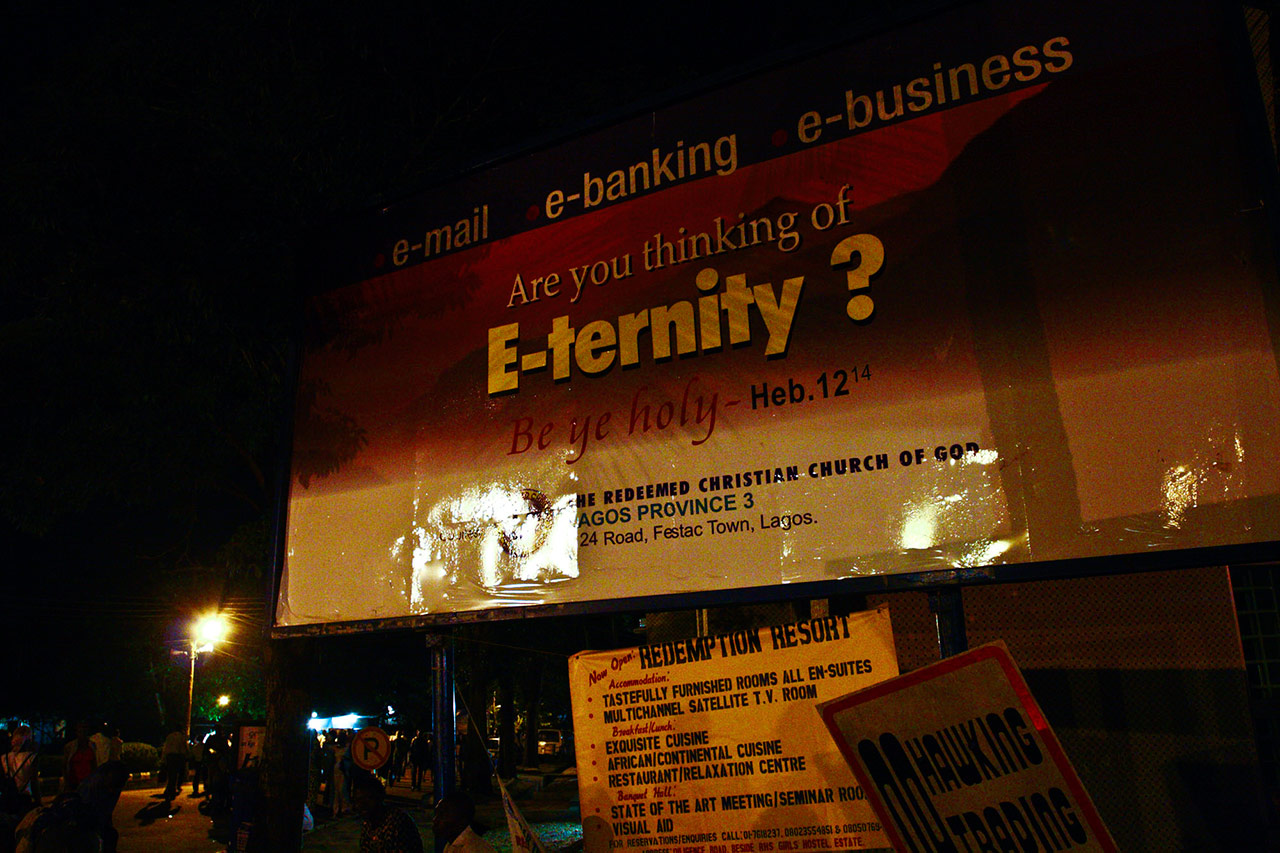

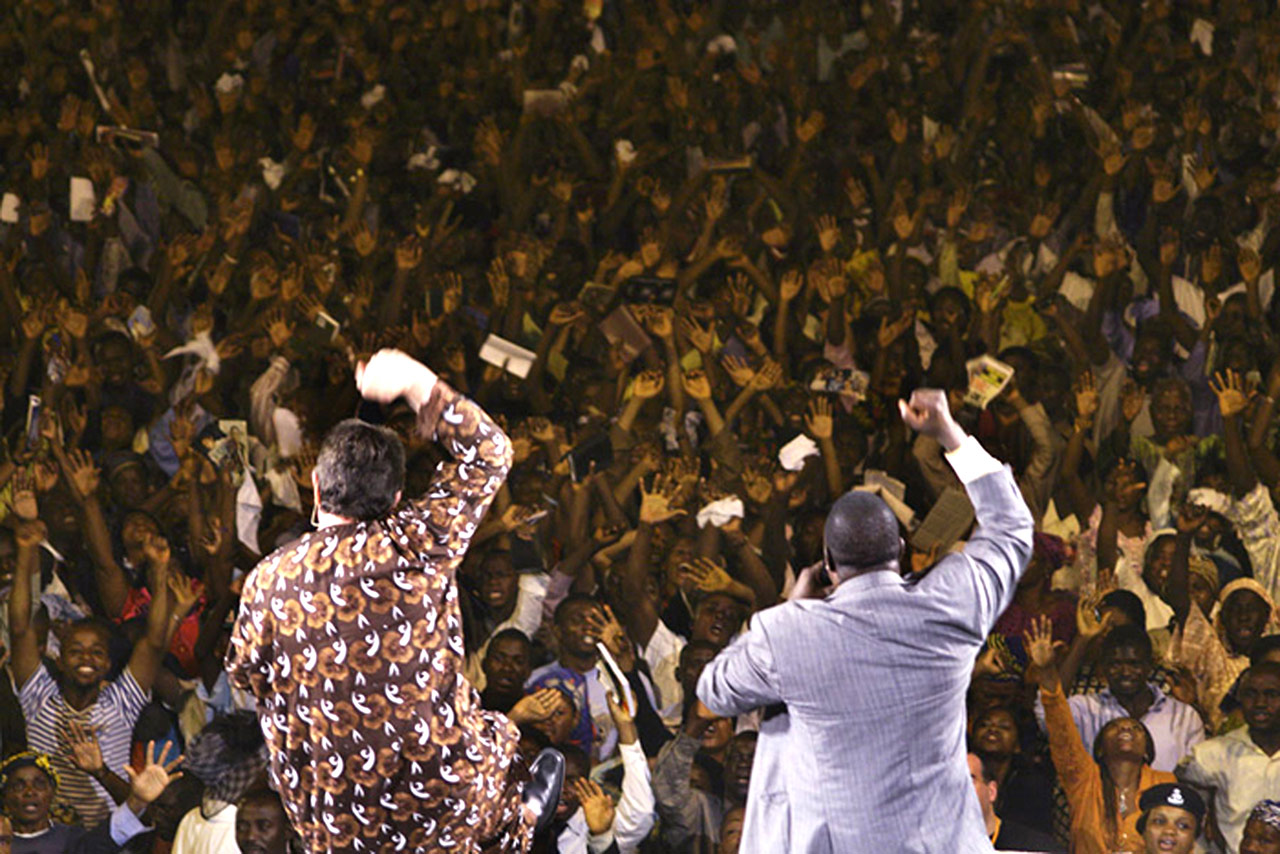

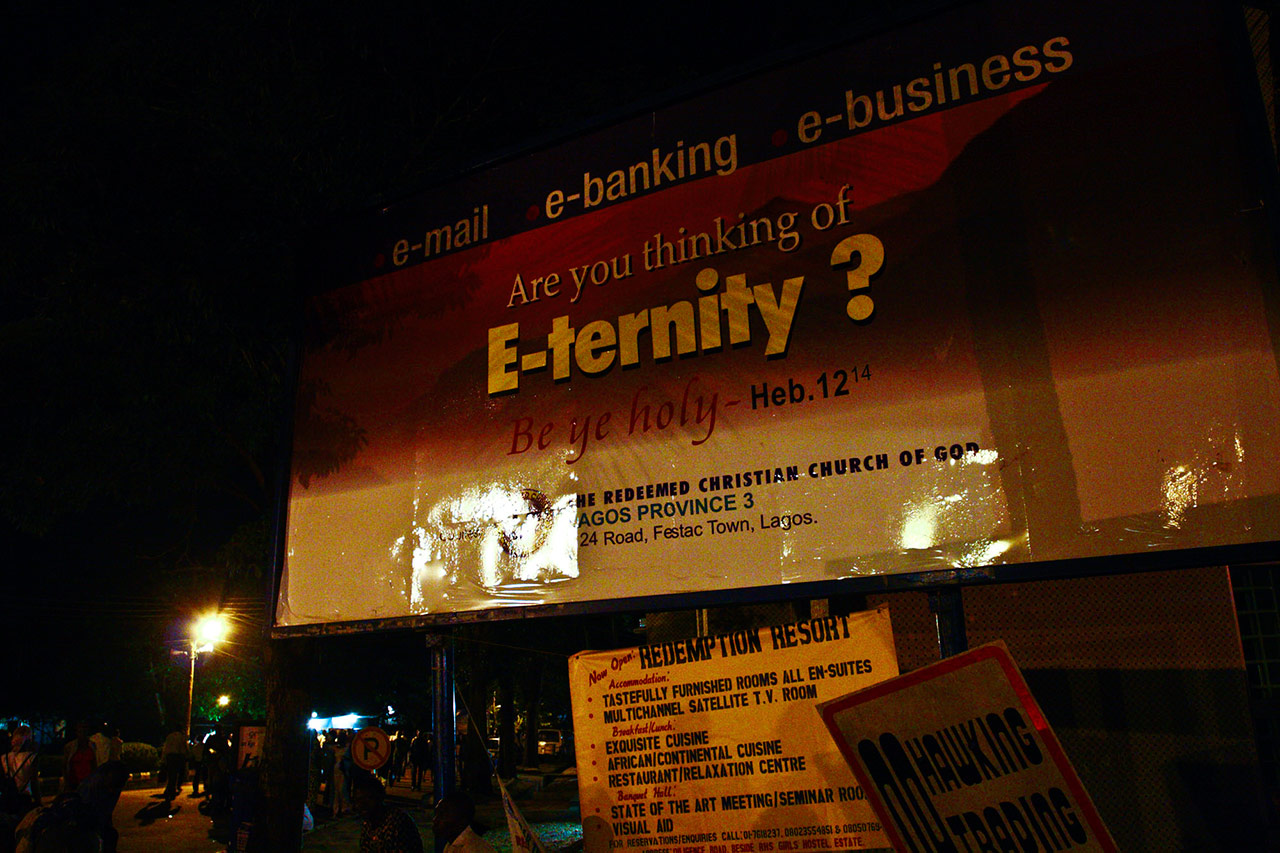

everydayafrica. #Lagos fragment. Photo by Tom Saater @tomsaater

To what extent can one formalize and give presence and solidity to a proposal that derives from collaboration and the use of a social network?

Throughout its history, photography has been related to the personal and collective memory. This text will not tackle the debate regarding whether it is a reliable testimony of current reality, but rather concentrate on what visual language is doing, creating, recreating and communicating in the present. One of the current tools to trigger this dialogue is the hashtag, as a complement to the photographic image that has transformed everyday communication and has become a simple, inexpensive, everyday action on a massive, global scale. Simply accompanying an image by two or three words preceded by a hashtag enables others to access photograph albums categorized by location, topic, mood or format (#streetartchilango); to travel and identify in real time to these communities so far removed from our everyday lives yet so close to our language (everydayafrica, everydayiran) , or to concentrate a story in citizen testimonials and produce social movements, thus raising awareness and mobilizing resources in real life (#Egipto, #IranElection, #15-M, #BringBackOurGirls, #YoSoy132). This allows the hashtag to community gaze, offer a panorama of the phenomenon and collective representation online, and show its integrating function. But how can it be conserved?

everydayiran. Young women taking a selfie in the Bazaar of #Isfahan. #Iran. Photo by Aseem Gujar @myaseemgujar

Only two years ago, hashtags were not perceived as content networks, but studied from a mass perspective, leading to the highly ephemeral trending topics. However, there is increasing interest in researching and analyzing this kind of connections, to better understand the social, political, commercial circumstances, and of course, go beyond borders to learn about local and even personal events.

The archives produced by hashtags are real-time records and documents in the cloud that we fear so much, and where we find so it hard to place our entire body of work. It contains our everyday communication and, even if we are not aware of what we deliver, our way of seeing and thinking are latent within it. One option to preserve all this archive would be to produce a local database, or to continue to entrust this virtual universe with our history, to share, modify, increase, exchange, store, read, reread or even eliminate it.

The hashtag can therefore be considered an extension of the light Barthes called the umbilical cord, 2 the skin that we share with those who have photographed themselves to share who they are, what they do and how they live; to represent themselves and join this globalized digital world of metadata in which the photographer is no longer the only means of objective or subjective expression of reality, but now feeds into various disciplines and mediums that democratize it as a tool and a language in itself.

1. Chris Messina, an active defender of open code, suggested using the name hashtag on August 23, 2007, with a simple tweet: "How do you feel about using # (pound) for groups? As in #barcamp [msg]?".

2. A real body, located there, produced radiation that impressed me, located here. It does not matter how long the transmission lasts; the photo of the disappeared being impresses me as would the deferred rays of a star. A kind of umbilical cord joins the body of the object photographed to my gaze: light, though impalpable, is a carnal medium, a skin I share with the beings who have been photographed. – R. Barthes.

Elisa Rugo (México, 1980). Lives and works in Mexico. She is a photographer, videographer and a specialist in visual communication with a degree in Creative Visualisation at the University of Communication. In 2012, she took part in the seminar Contemporary Photography at the Image Centre. She has participated in collective exhibitions in Pachuca, Querétaro, Guadalajara and Mexico-City. At the moment, she is the art director of the websites fpmeyer.com and museodemujeres.com and she is part of the editorial team of zonezero.com. You can see her work at: elisarugo.pro

Elisa Rugo (México, 1980). Lives and works in Mexico. She is a photographer, videographer and a specialist in visual communication with a degree in Creative Visualisation at the University of Communication. In 2012, she took part in the seminar Contemporary Photography at the Image Centre. She has participated in collective exhibitions in Pachuca, Querétaro, Guadalajara and Mexico-City. At the moment, she is the art director of the websites fpmeyer.com and museodemujeres.com and she is part of the editorial team of zonezero.com. You can see her work at: elisarugo.proOne of the greatest advantages of current photography, through its democratization as a tool and the technological advances in the media, is the guiding thread it establishes for collective representations in visual communication. This is largely the result of databases generated using key words, which provide information by describing and facilitating the identification of files and content. One of the most effective uses of this is the ubiquitous hashtag in social networks (Twitter, Instagram, Tumblr, FB). Eight years after Messina1 using the hashtag to group dialogues in social networks, this resource has produced endless possibilities not only for political and commercial marketing campaigns, but also for categorizing and linking information in a virtual world with millions of simultaneous thematic connections. It has served to increase the understanding of communities that would otherwise be hard to reach, which documentary photographers wish to comprehend and stop portraying from a distance.

everydayafrica. #Lagos fragment. Photo by Tom Saater @tomsaater

To what extent can one formalize and give presence and solidity to a proposal that derives from collaboration and the use of a social network?

Throughout its history, photography has been related to the personal and collective memory. This text will not tackle the debate regarding whether it is a reliable testimony of current reality, but rather concentrate on what visual language is doing, creating, recreating and communicating in the present. One of the current tools to trigger this dialogue is the hashtag, as a complement to the photographic image that has transformed everyday communication and has become a simple, inexpensive, everyday action on a massive, global scale. Simply accompanying an image by two or three words preceded by a hashtag enables others to access photograph albums categorized by location, topic, mood or format (#streetartchilango); to travel and identify in real time to these communities so far removed from our everyday lives yet so close to our language (everydayafrica, everydayiran) , or to concentrate a story in citizen testimonials and produce social movements, thus raising awareness and mobilizing resources in real life (#Egipto, #IranElection, #15-M, #BringBackOurGirls, #YoSoy132). This allows the hashtag to community gaze, offer a panorama of the phenomenon and collective representation online, and show its integrating function. But how can it be conserved?

everydayiran. Young women taking a selfie in the Bazaar of #Isfahan. #Iran. Photo by Aseem Gujar @myaseemgujar

Only two years ago, hashtags were not perceived as content networks, but studied from a mass perspective, leading to the highly ephemeral trending topics. However, there is increasing interest in researching and analyzing this kind of connections, to better understand the social, political, commercial circumstances, and of course, go beyond borders to learn about local and even personal events.

The archives produced by hashtags are real-time records and documents in the cloud that we fear so much, and where we find so it hard to place our entire body of work. It contains our everyday communication and, even if we are not aware of what we deliver, our way of seeing and thinking are latent within it. One option to preserve all this archive would be to produce a local database, or to continue to entrust this virtual universe with our history, to share, modify, increase, exchange, store, read, reread or even eliminate it.

The hashtag can therefore be considered an extension of the light Barthes called the umbilical cord, 2 the skin that we share with those who have photographed themselves to share who they are, what they do and how they live; to represent themselves and join this globalized digital world of metadata in which the photographer is no longer the only means of objective or subjective expression of reality, but now feeds into various disciplines and mediums that democratize it as a tool and a language in itself.

1. Chris Messina, an active defender of open code, suggested using the name hashtag on August 23, 2007, with a simple tweet: "How do you feel about using # (pound) for groups? As in #barcamp [msg]?".

2. A real body, located there, produced radiation that impressed me, located here. It does not matter how long the transmission lasts; the photo of the disappeared being impresses me as would the deferred rays of a star. A kind of umbilical cord joins the body of the object photographed to my gaze: light, though impalpable, is a carnal medium, a skin I share with the beings who have been photographed. – R. Barthes.

Elisa Rugo (México, 1980). Lives and works in Mexico. She is a photographer, videographer and a specialist in visual communication with a degree in Creative Visualisation at the University of Communication. In 2012, she took part in the seminar Contemporary Photography at the Image Centre. She has participated in collective exhibitions in Pachuca, Querétaro, Guadalajara and Mexico-City. At the moment, she is the art director of the websites fpmeyer.com and museodemujeres.com and she is part of the editorial team of zonezero.com. You can see her work at: elisarugo.pro

Elisa Rugo (México, 1980). Lives and works in Mexico. She is a photographer, videographer and a specialist in visual communication with a degree in Creative Visualisation at the University of Communication. In 2012, she took part in the seminar Contemporary Photography at the Image Centre. She has participated in collective exhibitions in Pachuca, Querétaro, Guadalajara and Mexico-City. At the moment, she is the art director of the websites fpmeyer.com and museodemujeres.com and she is part of the editorial team of zonezero.com. You can see her work at: elisarugo.proAlfredo Esparza

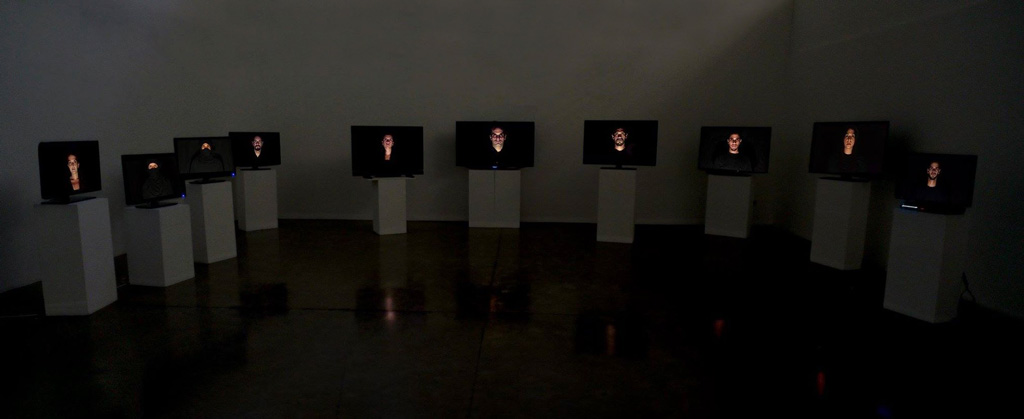

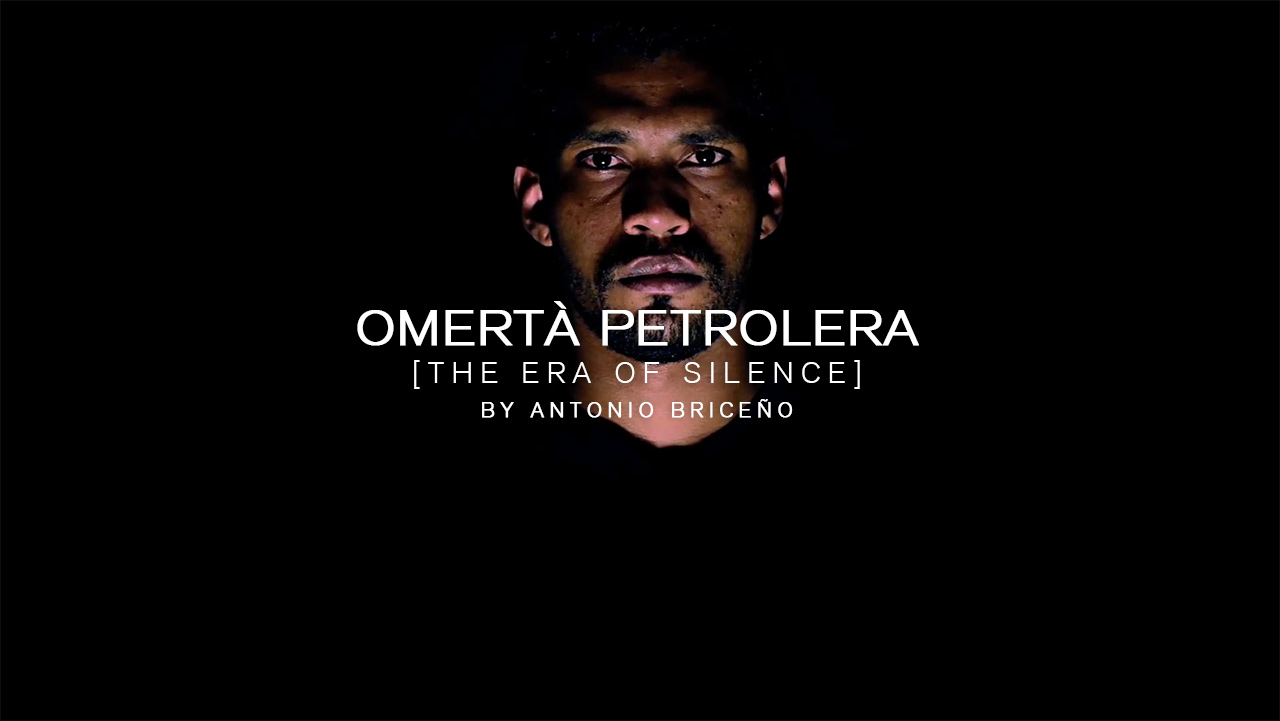

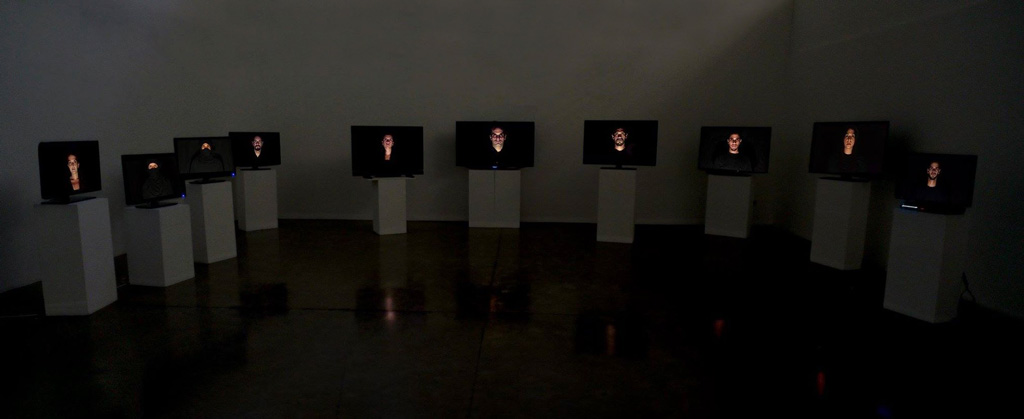

450 videoportraits made with cell phone

Since people daily have to travel long distances in Mexico City to get from home to work or school and then coming back, subway users employ this medium as a temporary extension of their homes, where they can claim as much privacy and intimacy they need; even when the metro is overcrowded.

Just to win a few minutes a day, travellers keep their minds off from what happens in the carriage during the trip by chatting with their companion, finishing pending work, resting, or having a moment of introspection.

What really matters is that the journey enables travellers to do more than simply move from one place to another, not only by the urge of snatching time in a city where traveling takes so long, but also to take the opportunity to spare some time for oneself.

| videoportrait #32 | videoportrait #41 | videoportrait #56 |

| videoportrait #123 | videoportrait #197 | videoportrait #201 |

| videoportrait #222 | videoportrait #262 | videoportrait #297 |

| videoportrait #360 | videoportrait #363 | videoportrait #375 |

| videoportrait #395 | videoportrait #412 | videoportrait #343 |

| videoportrait #356 | videoportrait #272 | videoportrait #323 |

Alfredo Esparza (Torreon, Mexico. 1980) Visual artist. Uses photography and video as main tools to produce his pieces. He had solo exhibitions in Torreon and Mexico City, and many group shows In US, Italy, Spain and Mexico. Most of his work deals with the tension generated by the interaction between strangers in public or private spaces. His work has been published in magazines such as Vice, Cuartoscuro and Xoo. From 2012 to 2014 he worked as head of exhibitions and resident curator and museographer at the Museo Nacional de Culturas Populares, in Mexico City. He also produced independent exhibitions for both private and public institutions in Mexico City. Since 2012, he is associated curator at .357 Gallery, in Mexico City. Lives and works between Torreon and Mexico City.

Alfredo Esparza (Torreon, Mexico. 1980) Visual artist. Uses photography and video as main tools to produce his pieces. He had solo exhibitions in Torreon and Mexico City, and many group shows In US, Italy, Spain and Mexico. Most of his work deals with the tension generated by the interaction between strangers in public or private spaces. His work has been published in magazines such as Vice, Cuartoscuro and Xoo. From 2012 to 2014 he worked as head of exhibitions and resident curator and museographer at the Museo Nacional de Culturas Populares, in Mexico City. He also produced independent exhibitions for both private and public institutions in Mexico City. Since 2012, he is associated curator at .357 Gallery, in Mexico City. Lives and works between Torreon and Mexico City.450 videoportraits made with cell phone

Since people daily have to travel long distances in Mexico City to get from home to work or school and then coming back, subway users employ this medium as a temporary extension of their homes, where they can claim as much privacy and intimacy they need; even when the metro is overcrowded.

Just to win a few minutes a day, travellers keep their minds off from what happens in the carriage during the trip by chatting with their companion, finishing pending work, resting, or having a moment of introspection.

What really matters is that the journey enables travellers to do more than simply move from one place to another, not only by the urge of snatching time in a city where traveling takes so long, but also to take the opportunity to spare some time for oneself.

| videoportrait #32 | videoportrait #41 | videoportrait #56 |

| videoportrait #123 | videoportrait #197 | videoportrait #201 |

| videoportrait #222 | videoportrait #262 | videoportrait #297 |

| videoportrait #360 | videoportrait #363 | videoportrait #375 |

| videoportrait #395 | videoportrait #412 | videoportrait #343 |

| videoportrait #356 | videoportrait #272 | videoportrait #323 |

Alfredo Esparza (Torreon, Mexico. 1980) Visual artist. Uses photography and video as main tools to produce his pieces. He had solo exhibitions in Torreon and Mexico City, and many group shows In US, Italy, Spain and Mexico. Most of his work deals with the tension generated by the interaction between strangers in public or private spaces. His work has been published in magazines such as Vice, Cuartoscuro and Xoo. From 2012 to 2014 he worked as head of exhibitions and resident curator and museographer at the Museo Nacional de Culturas Populares, in Mexico City. He also produced independent exhibitions for both private and public institutions in Mexico City. Since 2012, he is associated curator at .357 Gallery, in Mexico City. Lives and works between Torreon and Mexico City.

Alfredo Esparza (Torreon, Mexico. 1980) Visual artist. Uses photography and video as main tools to produce his pieces. He had solo exhibitions in Torreon and Mexico City, and many group shows In US, Italy, Spain and Mexico. Most of his work deals with the tension generated by the interaction between strangers in public or private spaces. His work has been published in magazines such as Vice, Cuartoscuro and Xoo. From 2012 to 2014 he worked as head of exhibitions and resident curator and museographer at the Museo Nacional de Culturas Populares, in Mexico City. He also produced independent exhibitions for both private and public institutions in Mexico City. Since 2012, he is associated curator at .357 Gallery, in Mexico City. Lives and works between Torreon and Mexico City.Donald Weber

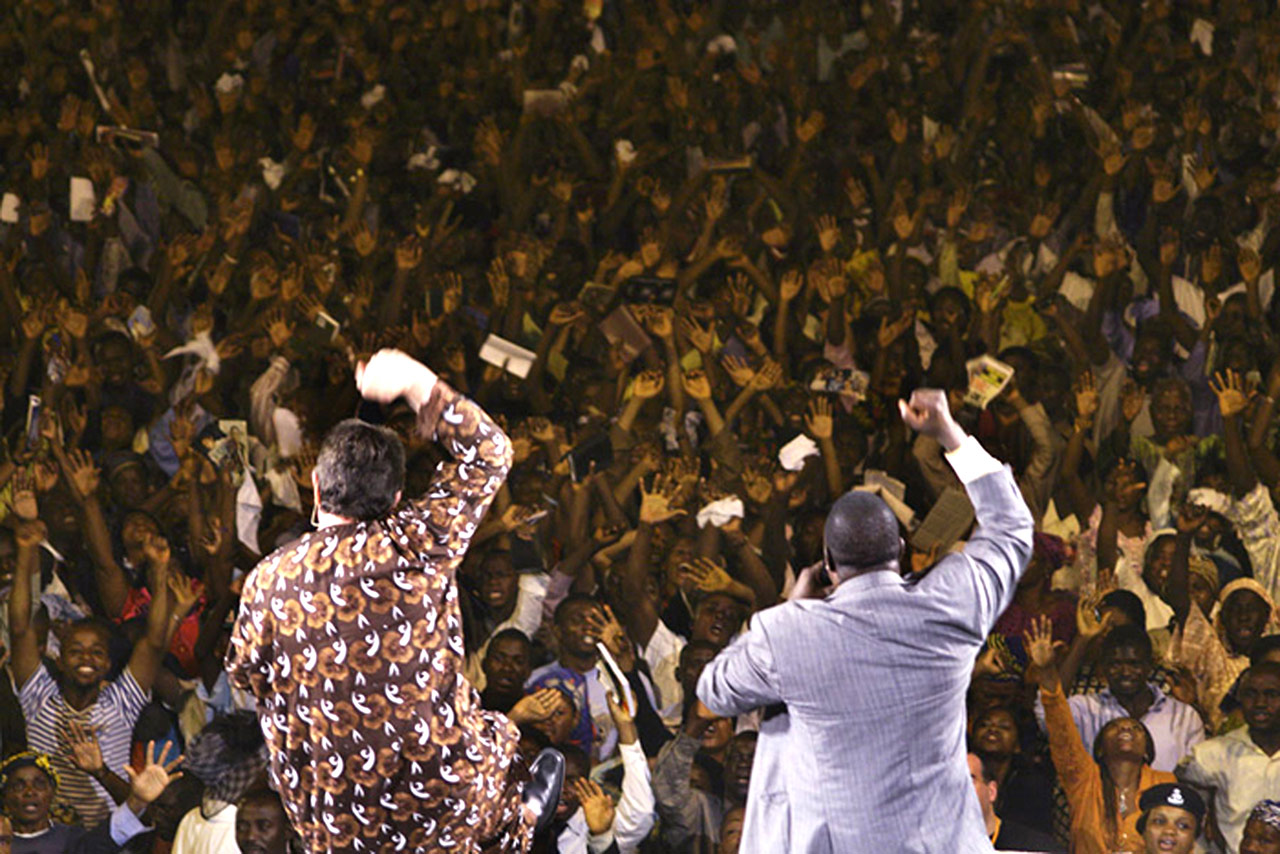

The ‘frontline’ of Hrushevskogo, from the perspective of the police. The area just behind the concrete barricade was where you needed to have accreditation from the EuroMaidan press office. You can see how narrow the area really was, and where the majority of the photography took place. Central Kiev, Ukraine, 2014.

Just because a photo looks like photojournalism, doesn’t mean it’s Photojournalism.

Photojournalism the ethic, the genre, the act of reportage through story and images, has been hijacked under the guise of “photojournalism” the style — where the style denotes “truth,” objectivity, righteousness, infallibility, etc. At what point did the act of making images subvert the idea of what Photojournalism is and should be?

This is not an argument for pushing aesthetics and technique out the window. Technique is integral to image-making (obviously), but it should service the story first and foremost; the type of image being produced should never dictate the story.

Here are two examples of bad photography from the Orange Revolution, demonstrating the staging element of events. I relied on tropes of grief, joy and “peace” etc. This was the first thing I ever photographed in Ukraine.

Too Slick To Trust

A technically proficient image that looks like those of past photojournalism will catch the eye. A technically proficient image may trick the viewer into thinking he or she is seeing something of substance, of what is commonly referred to as truthful. A technically proficient image meets the media business’ goal for cost-effective public attention.

Commodified imagery threatens photographers’ primary role as storytellers. Amplified technique threatens to dominate the image, and it will lead to picturesque gluttony. We, the news, and our understanding of the news are poorer for it.

These days, the most in-demand news photo is that of happenstance — typically dodged, burned, cropped, dramatized and with “extraneous” details within the frame excised. The photographer’s good intentions of authenticity surrender to economic facility in the clamor for — and shrill claims on — wavering public attention. Image product has been reduced to the glib one-off drama.

A Google image search for “Kiev Protests.” This contact sheet shows clearly our stranglehold on the ‘imaginary center’ and a total lack of peripheral understanding.

That said, the market demand is not a systematic attack upon journalism, nor a sabotage of democratic press. If only the problems could be so confidently attributed!

No, instead, what we have is a slow degradation of storytelling values in photojournalism. The photographer is rarely employed, nowadays, to tell the story as he or she sees it — the photographer is merely called upon to illustrate another’s account. Such images fail to engage the viewer and fail the larger purpose of the photographer.

We see on our front pages only facsimiles of 90-year-old Leica versions of photos.

Why do we adhere to notions of objectivity in photography? Especially when it crushes creative storytelling from those that hold the camera? Photographers choose where their frame goes. They selectively choose what the audience will see, will believe. Right off the bat, any individual image is deceptive, because there is no peripheral vision. Peripheries provide the greater context. Storytellers may be interested in the periphery, but technical image makers (and the news feeds they keep buzzing) are not.

The Periphery Is Where It’s At

As our world becomes entangled with greater access to other cultures, the professional photojournalism world has, unfortunately, remained fixated on an imaginary centre. As a result, the guidelines of what “makes a good picture” have remained intact. It’s focused on an ideal, the holy grail of the perfect picture, one picture raised above all else.

But what is the use of this philosophic ideal? Marx said that philosophy must relate to everyday experience to be of any use. The perfect picture is a mirage. Allow me to use my experience in Kiev in 2014 to illustrate the point.

I first watched EuroMaidan from afar, on TV, in the papers and the web. Ukraine was a place in which I lived and worked for nearly 10 years. It looked like Kiev was in flames, under siege. I emailed my friends there.

“Vanya, what’s happening, what’s going on?” I asked.

“Ah, Don, it’s okay, just protest on Maidan,” replied Vanya.

“But isn’t Kiev in flames?”

“No, Don, that’s just the news.”

I had to see. Surely something was happening. Of course it was, but not what I had seen on the news.

I’m including this image because it illustrates the scale of the area surrounding EuroMaidan. This is just Maidan Nezalezhnosti (Independence Square), where the speeches, tent city and encampments were located. Below this square is a large shopping mall. It was not uncommon for an event to occur outside, meanwhile people were shopping for jeans at Tommy Hilfiger below. I’m including it because I think it is the type of image that photojournalism too often forgets about.

I’m including this image because it illustrates the scale of the area surrounding EuroMaidan. This is just Maidan Nezalezhnosti (Independence Square), where the speeches, tent city and encampments were located. Below this square is a large shopping mall. It was not uncommon for an event to occur outside, meanwhile people were shopping for jeans at Tommy Hilfiger below. I’m including it because I think it is the type of image that photojournalism too often forgets about.

The area surrounding EuroMaidan was a vast space. In effect, protestors controlled the extended downtown of the city. Not just Maidan itself, but a vast spread throughout the central core. Upon arrival in Kiev in late January, I went to Maidan, and to the “frontline.” By now, the protestors had consolidated their territory. The frontline was the width of a four-lane street. Defined between apartment blocks on one side and a park on the other, a pinched point.

Police on one side, protestors on the other. Sand bags, two destroyed minibuses, detritus built up into a makeshift barricade. A small strip of No Man’s Land in-between. In order to enter the frontline, a media pass was needed. To get a media pass, you went to the Media HQ, showed your press credentials, signed and got your ticket. That day, I was ticket number 230. 229 accredited press before me.

Theatre Of War

The scene itself was theatre. Here we had the stage of revolution. A police line, protests as the Greek chorus, the set itself was the barricade. There was literally an audience. Grandmothers, parents, kids, teens, workers, passersby, anybody could come and spectate, and they did. Every weekend, thousands of people would stroll and watch. There was a slight hill to the left where you could get a good view overall, hundreds of people amongst the birch trees, watching the protestors sit and wait for something to happen, vigilant, on guard.

The protestors themselves were dressed for a show. Their outfits were kitted together from various leftover pieces found in someone’s homes, a weird montage of hockey player, fighter and knight. Many of the protestors themselves referenced modern media, as they had seen images of protests around the world and from different generations — the Russian Revolution of 1917, Paris ‘68, Vietnam, Kent State, British union strikers of the 1980s, Anti-Iraq protest, Arab Spring and their very own Orange Revolution.

The EuroMaidan protestors had been consumed by TV, by news images repurposed for a new battle, but were now referencing their own protest history. They promised to put on a show, and the media came to participate.

I’m caught in a weird loop where we photograph the protestors, the protestors see what gets photographed, they dress the part and then we photograph them again.

“If I go to a protest, what do I wear?” Simple: just reference the media. Many protestors talked about this.

“We are Mad Max” was the most popular analogy. “We are Knights of the Round Table!” “We are warriors of 1917!” But none of it was real. What was real, was the idea of protest, that people could choose to fight and die for a cause.

The story was real. The story was authentic.

Sergiy Lebedynskyy and Vladyslav Krasnoshchok. From the series EuroMaidan.

Most of the images that came from the EuroMadian protest, however, were not real. Not much of what I read or saw in the media was an honest reaction to the realities of central Kiev.

The work that rose above was work that had intent and authorship. Sergiy Lebedynskyy and Vladyslav Krasnoshchok with their book EuroMaidan made an intensely personal and genuine document of the revolt, which didn’t capture the event so much as the feeling, the tactile response to revolution — an authentic look inside what a protest really is. Protest is for cameras, but “protest” is real.

Sergiy Lebedynskyy and Vladyslav Krasnoshchok. From the series EuroMaidan.

And so the photographer who enters the staged play, the theatre of news, has to be wary. Are you participating in the facade of the event, or are you genuinely documenting it? When you photograph the frontline, do you turn around? Do you show the old lady entering her apartment, the couple having coffee, or the tired protestor sleeping? Do you show the audience, the set, and the actors? If not, then it enables the deceit of a staged moment.

A clear focus on intent leads to authorship, honesty, authenticity and story.

Sergiy Lebedynskyy and Vladyslav Krasnoshchok. From the series EuroMaidan.

How Did Technique Come To Replace Story?

From a Marxist perspective, technique may have replaced storytelling on account of capital’s natural inertia and avoidance of risk. Stories and story ideas are subject to budgetary attenuation just as camera parts and travel budgets are. Plastic lenses are cheaper than glass, and anybody can mimic a dodged and burned print with ubiquitous software.

However, there is no cheap substitute for good story-sense and, as such, good story sense gets overlooked.

It’s a given that a photographer has to make something, bound on using the four-sided frame and the small “negative,” armed with variations of the 35mm rangefinder first perfected by Leica 90 years ago. The conventions this technology imposes on story are legion. Look back at documentary photography before the rise of the Leica and you have some invincible variations, limited by technical capability, but still contributing to an evolving, novel language.

Suddenly, within a single generation, that image perfected by Cartier-Bresson and others has frozen solid.

Digital formats gave us technical progress, but no visual progress.

With photojournalism’s suspect history and its acceleration into the technical age, there is now a permanent element of unfaithfulness within the photographic medium. What makes photography faithful is not laborious inquisitions into levels of image-processing. Well, that is part of it, but mostly it is our collective faith in the intent of the story.

Eugene Smith once said: “The honesty lies in my — the photographer’s — ability to understand.” It has nothing to do with aesthetic and technical execution of the photograph, but in the author’s integrity in developing a story.

Love Photographers First, and Photography Second

I’m not saying this to champion photography above all other creative mediums. I’m not saying this to convince you to love an unlovable cheat. I’m saying this so we might support the earnest and inventive storytellers and be damned the others that act the part in our industrial news complex.