Max de Esteban

ZZ. What led you to appropriation and remix and how are they significant in your work?

M. Appropriation and remix have a long artistic tradition, beginning with Picasso’s collages. As early as the 1920s, Hannah Hoch and the Dadaists used this mode of expression to create major photographic works. In music, for example, from today’s DJs and Pop to Glenn Gould and Miles Davis, the practice of remix, collage and appropriation has been an essential part of their production. What I mean is that as an artistic concept, appropriation and remix are pretty standard and not particularly groundbreaking.

The interesting question is why their aesthetic power has been reasserted in photography precisely now. And I think one possible answer would be the combination of the formal exhaustion of the linear perspective as a photographic representation of the world and the huge impact digitization is having on every aspect of our lives. I would answer your question by turning it around and saying I find it hard to think of a truly relevant form of photography for the world we live in that continues to respect the Eurocentric, reactionary structure of the dark room.

ZZ. What do you mean by Eurocentric and reactionary?

M. The linear perspective, the visual structure resulting from the dark room, is a very particular and ideological way of visualizing the world. Panofsky has a text about it he wrote in 1927, a real classic, that is a pleasure to read.

But what is really remarkable is that it is an exception in art history. In 10,000 years of history, the linear perspective spans only 500 years and is located exclusively in the West. It has never been of interest to Asian, or pre-Columbian or African art ... it is a European way of seeing in a period beginning in the Renaissance and ending in the 19th century.

And this is no coincidence because its ideological content is well known. The linear perspective arranges the world from the point of view of an autonomous individual whose individuality is the world’s principle of meaning. It is pure Descartes. And we all remember Descartes’ Fifth Meditation, which states that since the essence of matter is its extension, geometry is an essential instrument for understanding nature. Modernity can be defined as the advance of abstraction and the prevalence of the quantitative over the qualitative in which the mathematical-scientific order is regarded as the only source of valid knowledge. There is so much contemporary thought that debunks this narrative that I won't repeat it here.

Thus, surprisingly, my earlier comment is still valid. Why should digital photography continue giving priority to a functionally and ideologically devalued visual structure?

ZZ. Why do you think digital photography changes the way we understand appropriation and remix?

M. Digital technologies are leading us towards the radical transformation of our world. By replacing the industrial economy with a bio-cybernetic system, digitization is modifying our environment, our subjectivity and soon, our bodies. This is the technological phenomenon that will define our era and therefore our culture.

Unlike an analog file, a digital file is invisible. It is a code whose visual expression is a translation highly mediated by default algorithms, whose most prominent feature is precisely its immateriality.

This technical structure fits our current era of abstraction and non-referentiality and the digital financialization of the economy. How do we see the world today? We have the answer on our computer and Smartphone screens. What is the essential aspect of the financial economy? The recombination of existing information units to create new information, in other words, “constructive compositing”. Digitization has definitively invalidated linear narrative, the monocular perspective and the author’s “authority”.

ZZ. You attach a great deal of importance to the concept of technology in your work. Could you explain why?

M. We are moving towards a world as a “technological whole”. Technical manipulation has already invaded our bodies, the last frontier, and no-one doubts that having machines inside our bodies will soon become commonplace.

The cyborg raises more complex issues for our species, which, though somewhat deteriorated, continues to maintain the autonomy of the subject as an essential value. Abstraction, digitization and cyborg are three sides of the same coin that heralds our new world, whether we like it or not. In my opinion, reflecting on technology is necessary, urgent and politically essential.

ZZ. And how do you think technology affects the practice of photography?

M. I’d like to point something out. One of the problems of photography is the confusion between technology and use. Writing is a communication technology that serve to draw up a commercial contract and compose a poem by Virgil. It is the same technology but nobody would ever mistake Virgil for a notary. In photography, we tend to combine uses, which creates enormous confusion in critical discourse. Throughout this interview, I have been referring to the use of photography as a means of artistic expression.

The thing is that photography has always been halfway to a cyborg. It is a machine that affects and to some extent determines human power, thought and expression and is therefore an ideal place for reflecting on the issues I mentioned earlier.

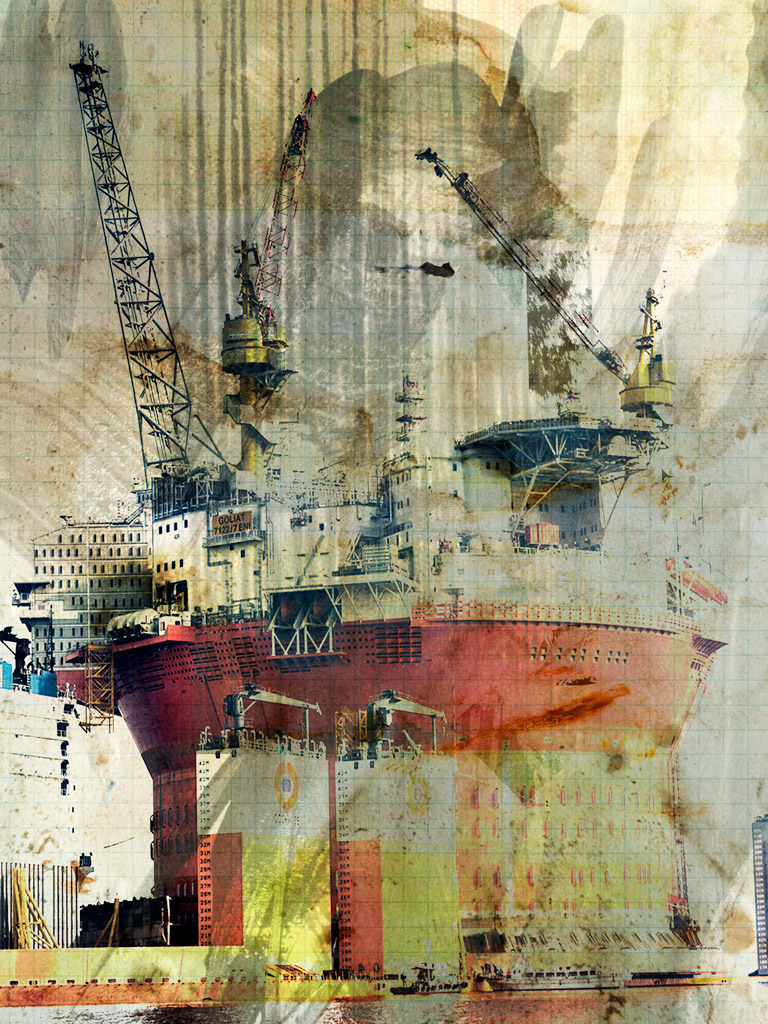

To give you an example: How can you visually depict the abstraction of the economy when the material references of wealth have been replaced by a binary code? That’s what I’m doing at the moment and it forces me to rethink what “representation” means in this new visual regime.

Another example: How does the idea of the cyborg affect art categories? That’s the topic I try to get my teeth into in the text “Cyborg Art: art in the bio-cybernetic era”. And there are a thousand other possible ideas that make photography an exciting medium at this particular historical time. The point is that if photographic practice does not take up the challenge raised by contemporaneity, it will be relegated to banality and antique shops.

ZZ. How do you choose the sources you use and what significance do they have for your series?

M. Like nearly everything in life, it is a combination of determination and chance. In my case, too much planning and/or reflection in my work paralyzes me while dreams or rather daydreams are of paramount importance.

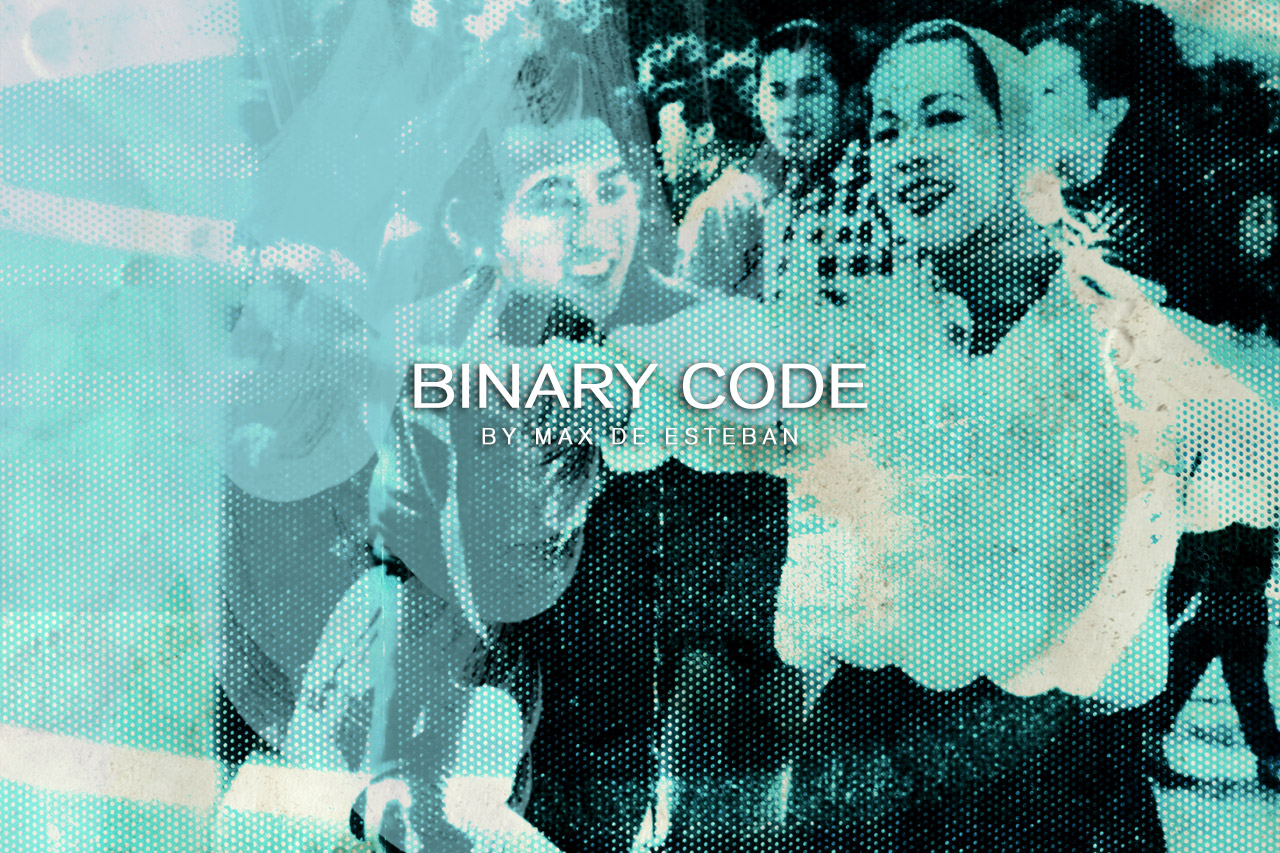

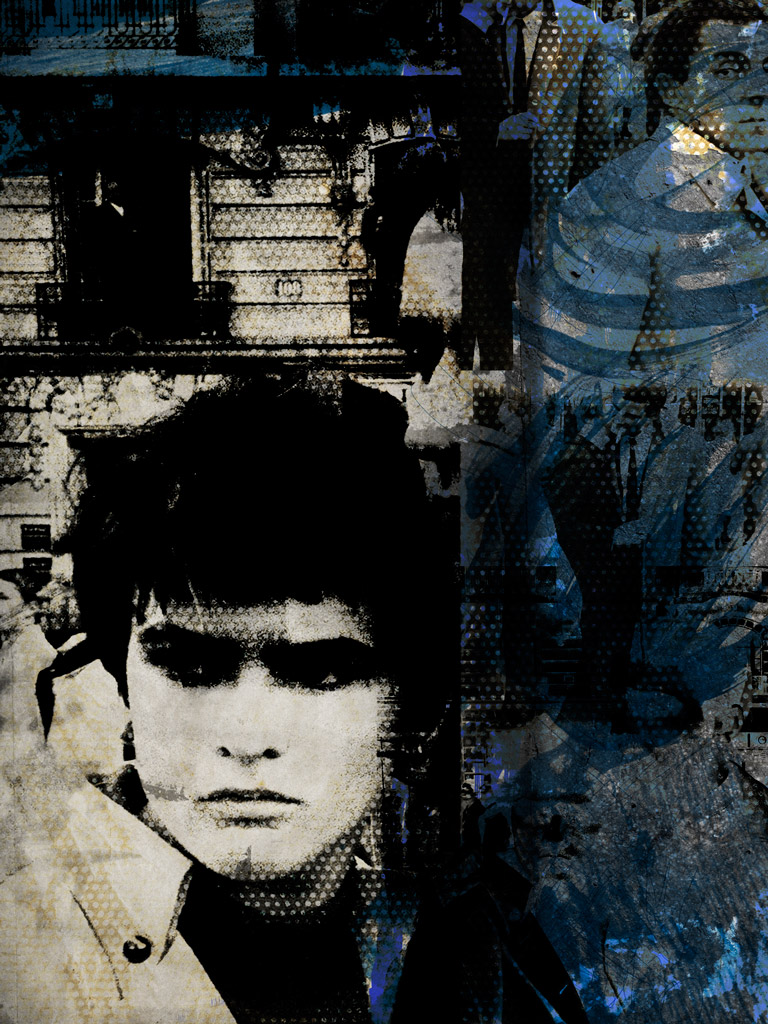

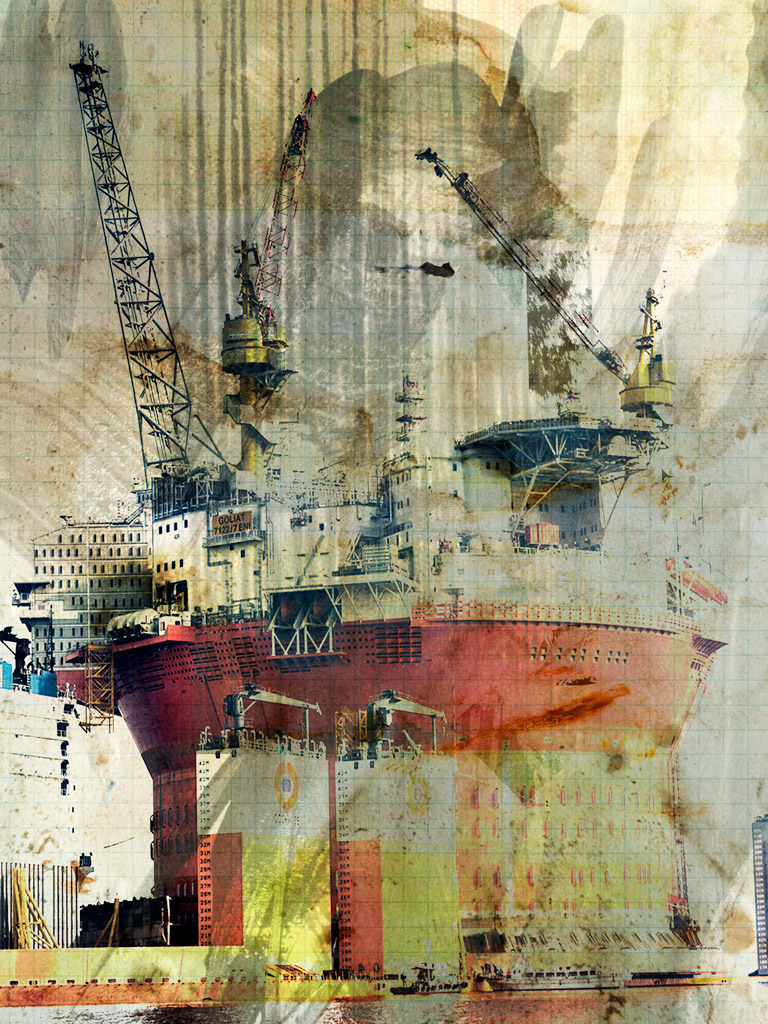

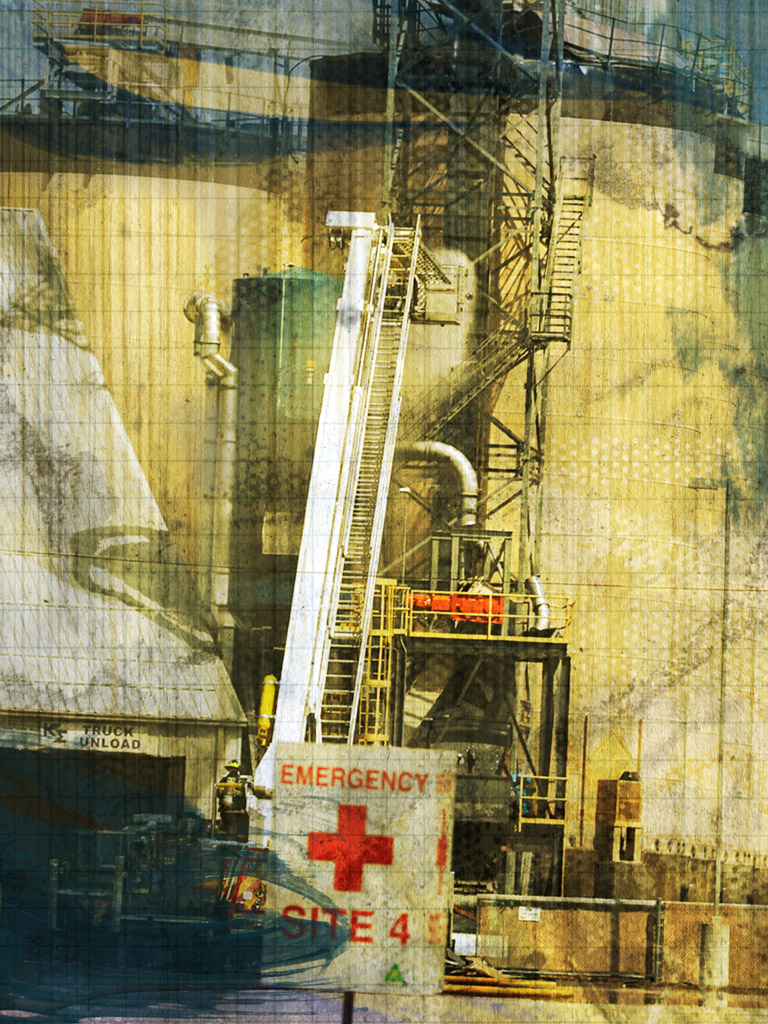

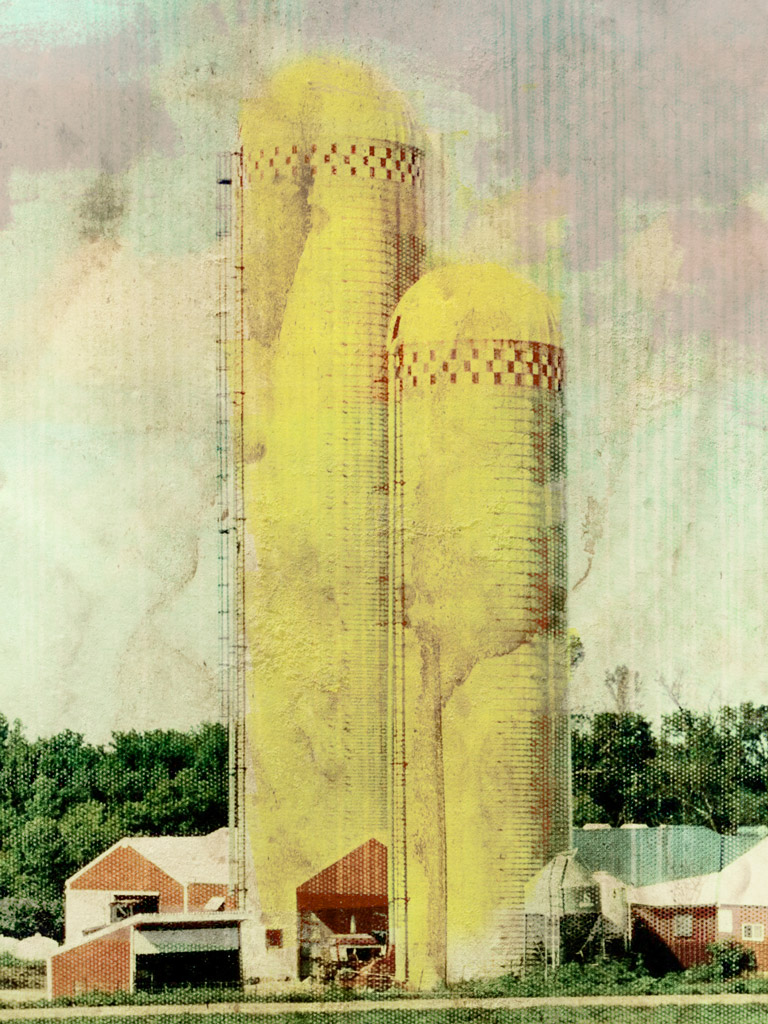

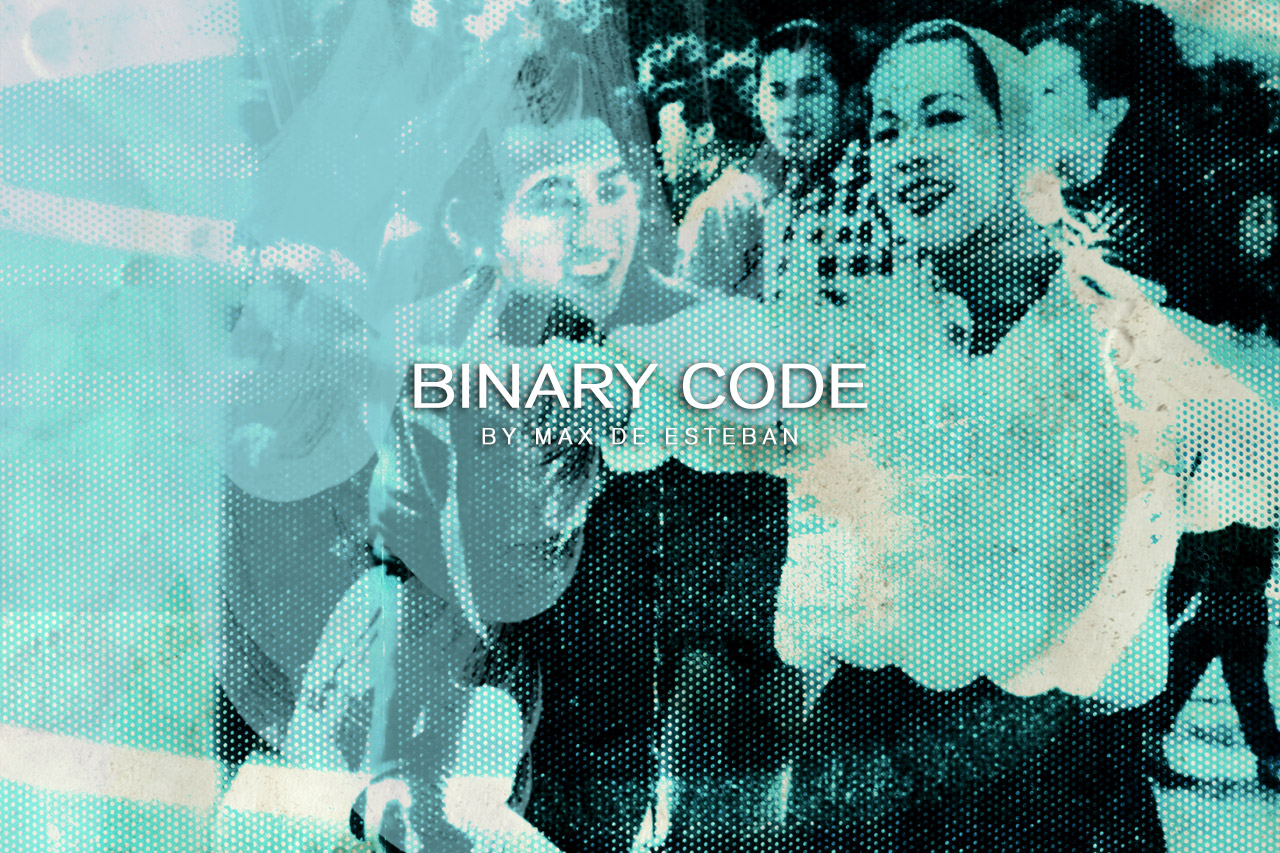

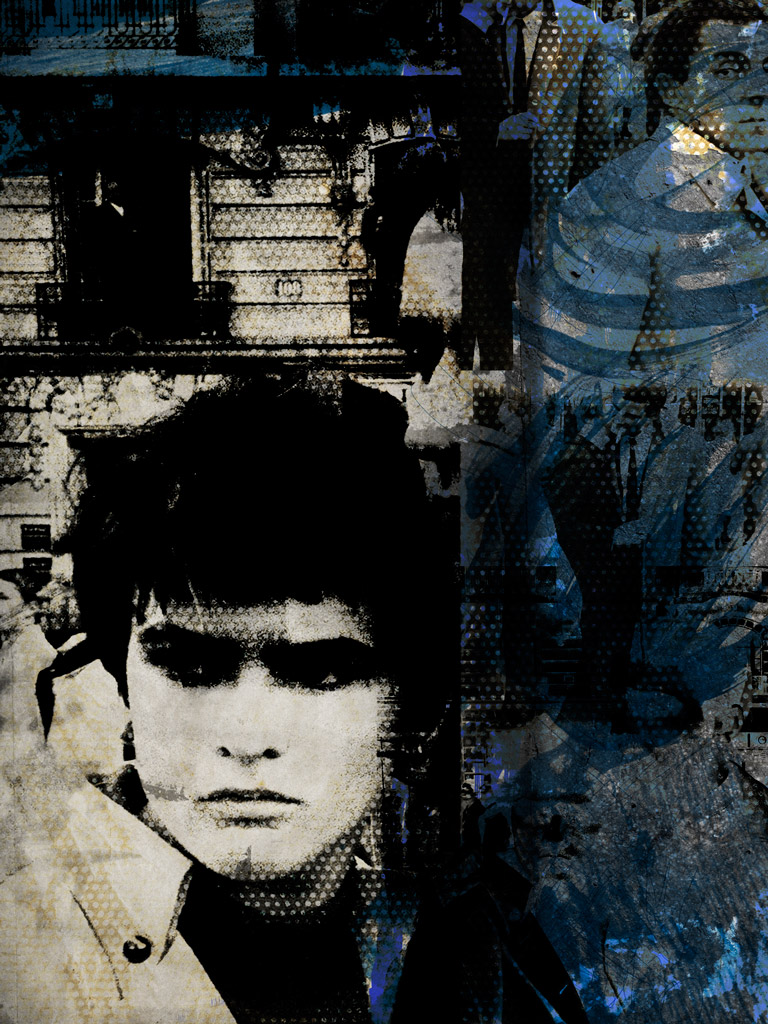

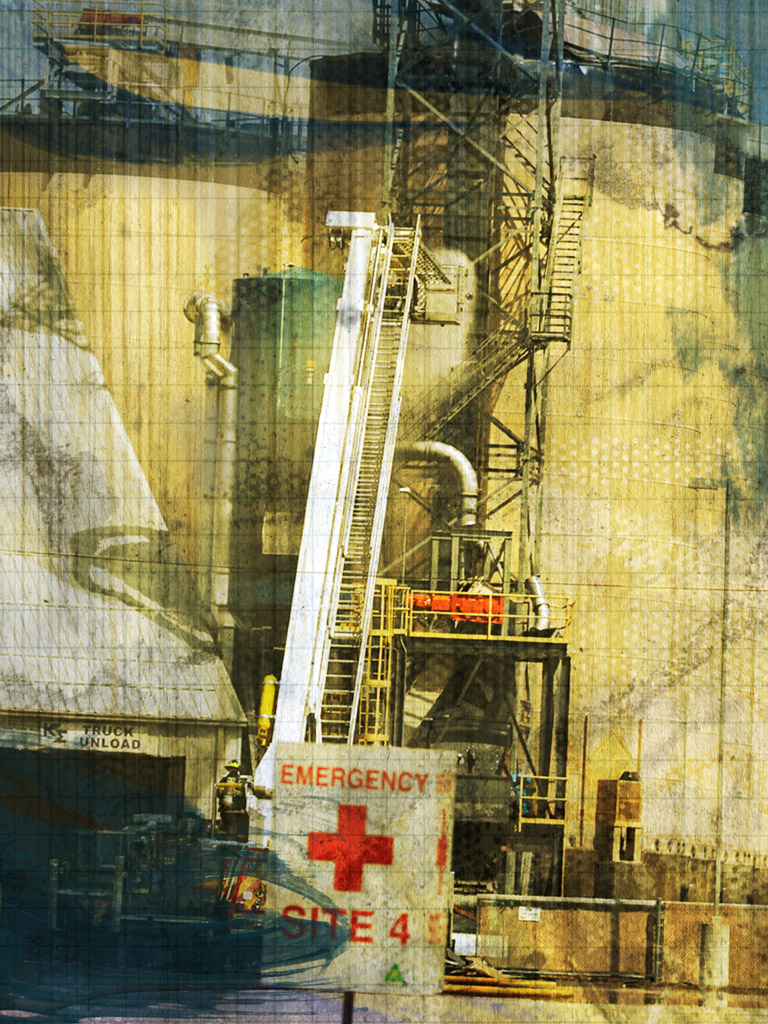

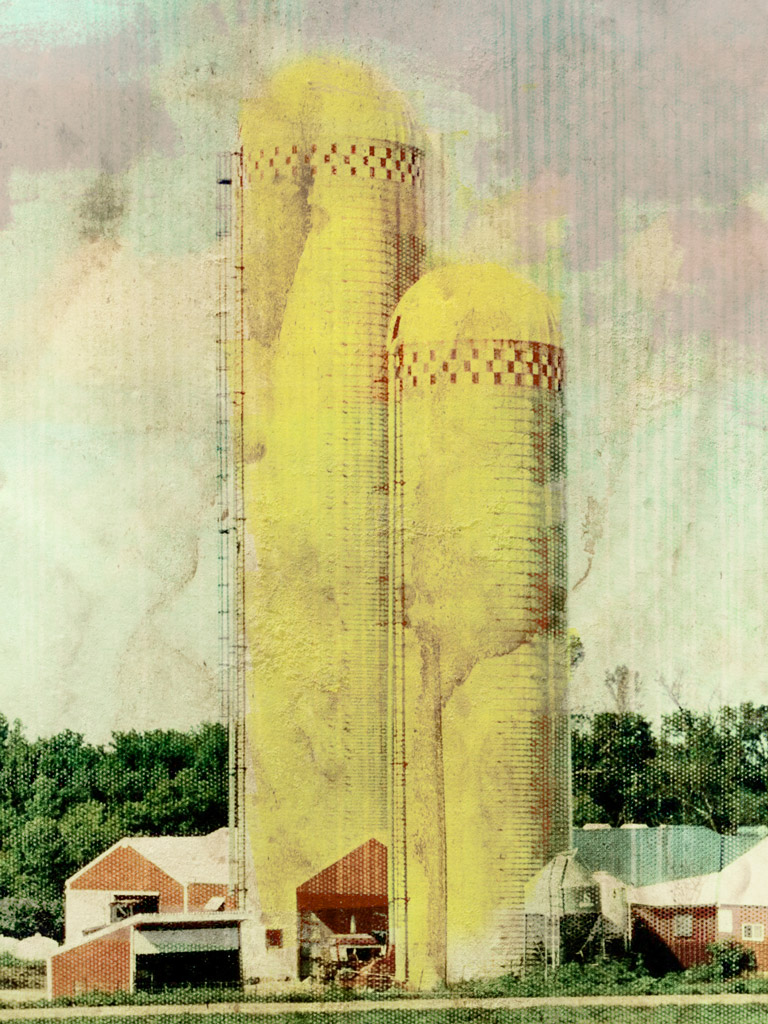

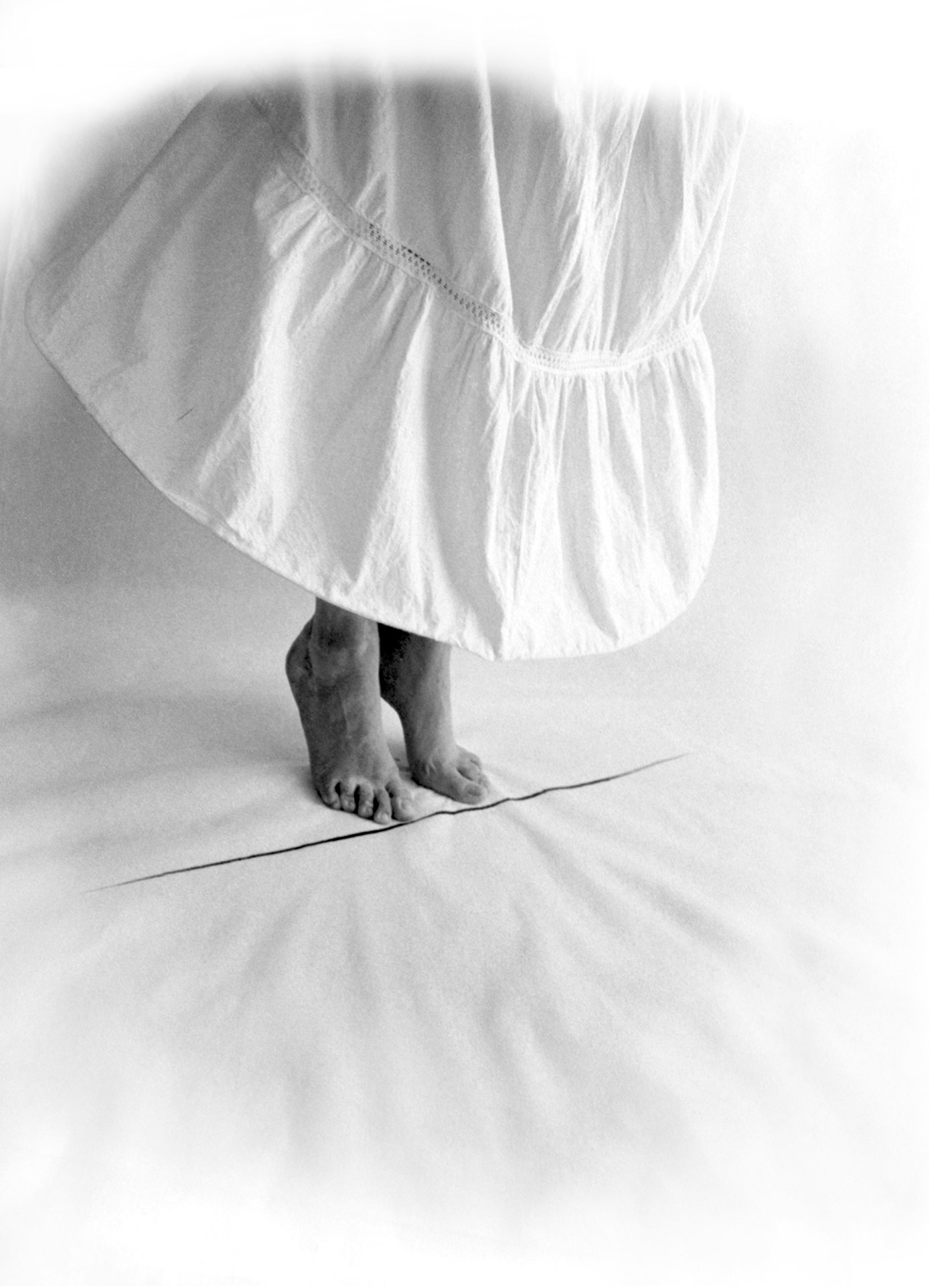

My latest project, called Binary Code, attempts to give visual expression to a world where databases and algorithms determine the ultimate reality, including nature. This is essentially the end of the order of nature as we know it.

And for some reason I can’t explain, the whole series consists of images of women and industrial silos. It could be because my files are full of these images which I have always found fascinating although I could also be trying to justify it as the end of a fundamental symbol where the woman and uterus are no longer relevant symbols for representing fertility, reproduction, beauty or nature.

I would like to comment on an aspect that is important for me. The criteria on the basis of which the artist selects an “appropriate” object may vary but the relationship between artist and subject is never univocal. The artist is only one of the parts. The object rebels and fights for its real nature, reacting to manipulation and boycotting it. The sign-object maintains some of its original nature, however much it fights against it. I think this negotiation between idea and reality is what makes appropriation so interesting.

ZZ. How does having sources with such diverse origins affect the narrative and timing of your images?

M. Nothing has different origins. Our only access to reality is mathematics, and quantum physics has eliminated time as an explanatory element for the behavior of elementary particles. Stripping photography of narrative and temporality is a lofty and necessary goal.

Narrative and temporality can be analyzed from many perspectives. For example, for Cyborg art, time is irrelevant because it can accumulate and eliminate modifications from its code indefinitely, meaning that there is no original or copy. Another less visionary example would be the way we experience the Internet today, jumping from one hyperlink to another, breaking up the original narrative structure of a text. Narrative as a mechanism and source of truth only continues to operate in Hollywood.

But it is a complex topic, because with narrative and temporality, what we are talking about is the issue of meaning. Refuting narrative entails resisting a set meaning that permits redemption (here I am referring to Adorno’s famous essay on Beckett). Eluding narrative prevents access to the comfortable world of history and fable.

In Binary Code there is no narrative. There are simply visual objects seeking to reclaim their meaning in their material specificity. Binary code, from its maximum abstraction, creates objects whose significance is drawn from its materiality rather than the code. The disenchantment of modern nature, its non-meaning, does not prevent nature from speaking through our bodies, desires, suffering and needs. By reclaiming the object, this project calls for a return to aesthetic materialism (albeit in an updated form).

If you think about it for a moment, it may also be time to reclaim the Aztec god Ometeotl as a contemporary symbol. Ometeotl, the immanent, invisible and immaterial god who had no temple, is the creator of all dualities (and therefore predates them): time and space, male and female, day and night, matter and spirit, zero and one. He is the creator of everything. Ometeotl is the binary code.

Max de Esteban (Spain). A fine-art photographer. Holds a Graduate degree from UPC, a Master from Stanford University and a PhD from URL. He is a Fulbright Alumni. His work is organized in two distinct bodies: Elegies of Manumission and Propositions. Awards: the 2010 National Award of Professional Photography (Spain)- Gold LUX.[2] and Grand Prix Jury's Special Award, Fotofestiwal 2010, Poland.

Max de Esteban (Spain). A fine-art photographer. Holds a Graduate degree from UPC, a Master from Stanford University and a PhD from URL. He is a Fulbright Alumni. His work is organized in two distinct bodies: Elegies of Manumission and Propositions. Awards: the 2010 National Award of Professional Photography (Spain)- Gold LUX.[2] and Grand Prix Jury's Special Award, Fotofestiwal 2010, Poland.

ZZ. What led you to appropriation and remix and how are they significant in your work?

M. Appropriation and remix have a long artistic tradition, beginning with Picasso’s collages. As early as the 1920s, Hannah Hoch and the Dadaists used this mode of expression to create major photographic works. In music, for example, from today’s DJs and Pop to Glenn Gould and Miles Davis, the practice of remix, collage and appropriation has been an essential part of their production. What I mean is that as an artistic concept, appropriation and remix are pretty standard and not particularly groundbreaking.

The interesting question is why their aesthetic power has been reasserted in photography precisely now. And I think one possible answer would be the combination of the formal exhaustion of the linear perspective as a photographic representation of the world and the huge impact digitization is having on every aspect of our lives. I would answer your question by turning it around and saying I find it hard to think of a truly relevant form of photography for the world we live in that continues to respect the Eurocentric, reactionary structure of the dark room.

ZZ. What do you mean by Eurocentric and reactionary?

M. The linear perspective, the visual structure resulting from the dark room, is a very particular and ideological way of visualizing the world. Panofsky has a text about it he wrote in 1927, a real classic, that is a pleasure to read.

But what is really remarkable is that it is an exception in art history. In 10,000 years of history, the linear perspective spans only 500 years and is located exclusively in the West. It has never been of interest to Asian, or pre-Columbian or African art ... it is a European way of seeing in a period beginning in the Renaissance and ending in the 19th century.

And this is no coincidence because its ideological content is well known. The linear perspective arranges the world from the point of view of an autonomous individual whose individuality is the world’s principle of meaning. It is pure Descartes. And we all remember Descartes’ Fifth Meditation, which states that since the essence of matter is its extension, geometry is an essential instrument for understanding nature. Modernity can be defined as the advance of abstraction and the prevalence of the quantitative over the qualitative in which the mathematical-scientific order is regarded as the only source of valid knowledge. There is so much contemporary thought that debunks this narrative that I won't repeat it here.

Thus, surprisingly, my earlier comment is still valid. Why should digital photography continue giving priority to a functionally and ideologically devalued visual structure?

ZZ. Why do you think digital photography changes the way we understand appropriation and remix?

M. Digital technologies are leading us towards the radical transformation of our world. By replacing the industrial economy with a bio-cybernetic system, digitization is modifying our environment, our subjectivity and soon, our bodies. This is the technological phenomenon that will define our era and therefore our culture.

Unlike an analog file, a digital file is invisible. It is a code whose visual expression is a translation highly mediated by default algorithms, whose most prominent feature is precisely its immateriality.

This technical structure fits our current era of abstraction and non-referentiality and the digital financialization of the economy. How do we see the world today? We have the answer on our computer and Smartphone screens. What is the essential aspect of the financial economy? The recombination of existing information units to create new information, in other words, “constructive compositing”. Digitization has definitively invalidated linear narrative, the monocular perspective and the author’s “authority”.

ZZ. You attach a great deal of importance to the concept of technology in your work. Could you explain why?

M. We are moving towards a world as a “technological whole”. Technical manipulation has already invaded our bodies, the last frontier, and no-one doubts that having machines inside our bodies will soon become commonplace.

The cyborg raises more complex issues for our species, which, though somewhat deteriorated, continues to maintain the autonomy of the subject as an essential value. Abstraction, digitization and cyborg are three sides of the same coin that heralds our new world, whether we like it or not. In my opinion, reflecting on technology is necessary, urgent and politically essential.

ZZ. And how do you think technology affects the practice of photography?

M. I’d like to point something out. One of the problems of photography is the confusion between technology and use. Writing is a communication technology that serve to draw up a commercial contract and compose a poem by Virgil. It is the same technology but nobody would ever mistake Virgil for a notary. In photography, we tend to combine uses, which creates enormous confusion in critical discourse. Throughout this interview, I have been referring to the use of photography as a means of artistic expression.

The thing is that photography has always been halfway to a cyborg. It is a machine that affects and to some extent determines human power, thought and expression and is therefore an ideal place for reflecting on the issues I mentioned earlier.

To give you an example: How can you visually depict the abstraction of the economy when the material references of wealth have been replaced by a binary code? That’s what I’m doing at the moment and it forces me to rethink what “representation” means in this new visual regime.

Another example: How does the idea of the cyborg affect art categories? That’s the topic I try to get my teeth into in the text “Cyborg Art: art in the bio-cybernetic era”. And there are a thousand other possible ideas that make photography an exciting medium at this particular historical time. The point is that if photographic practice does not take up the challenge raised by contemporaneity, it will be relegated to banality and antique shops.

ZZ. How do you choose the sources you use and what significance do they have for your series?

M. Like nearly everything in life, it is a combination of determination and chance. In my case, too much planning and/or reflection in my work paralyzes me while dreams or rather daydreams are of paramount importance.

My latest project, called Binary Code, attempts to give visual expression to a world where databases and algorithms determine the ultimate reality, including nature. This is essentially the end of the order of nature as we know it.

And for some reason I can’t explain, the whole series consists of images of women and industrial silos. It could be because my files are full of these images which I have always found fascinating although I could also be trying to justify it as the end of a fundamental symbol where the woman and uterus are no longer relevant symbols for representing fertility, reproduction, beauty or nature.

I would like to comment on an aspect that is important for me. The criteria on the basis of which the artist selects an “appropriate” object may vary but the relationship between artist and subject is never univocal. The artist is only one of the parts. The object rebels and fights for its real nature, reacting to manipulation and boycotting it. The sign-object maintains some of its original nature, however much it fights against it. I think this negotiation between idea and reality is what makes appropriation so interesting.

ZZ. How does having sources with such diverse origins affect the narrative and timing of your images?

M. Nothing has different origins. Our only access to reality is mathematics, and quantum physics has eliminated time as an explanatory element for the behavior of elementary particles. Stripping photography of narrative and temporality is a lofty and necessary goal.

Narrative and temporality can be analyzed from many perspectives. For example, for Cyborg art, time is irrelevant because it can accumulate and eliminate modifications from its code indefinitely, meaning that there is no original or copy. Another less visionary example would be the way we experience the Internet today, jumping from one hyperlink to another, breaking up the original narrative structure of a text. Narrative as a mechanism and source of truth only continues to operate in Hollywood.

But it is a complex topic, because with narrative and temporality, what we are talking about is the issue of meaning. Refuting narrative entails resisting a set meaning that permits redemption (here I am referring to Adorno’s famous essay on Beckett). Eluding narrative prevents access to the comfortable world of history and fable.

In Binary Code there is no narrative. There are simply visual objects seeking to reclaim their meaning in their material specificity. Binary code, from its maximum abstraction, creates objects whose significance is drawn from its materiality rather than the code. The disenchantment of modern nature, its non-meaning, does not prevent nature from speaking through our bodies, desires, suffering and needs. By reclaiming the object, this project calls for a return to aesthetic materialism (albeit in an updated form).

If you think about it for a moment, it may also be time to reclaim the Aztec god Ometeotl as a contemporary symbol. Ometeotl, the immanent, invisible and immaterial god who had no temple, is the creator of all dualities (and therefore predates them): time and space, male and female, day and night, matter and spirit, zero and one. He is the creator of everything. Ometeotl is the binary code.

Max de Esteban (Spain). A fine-art photographer. Holds a Graduate degree from UPC, a Master from Stanford University and a PhD from URL. He is a Fulbright Alumni. His work is organized in two distinct bodies: Elegies of Manumission and Propositions. Awards: the 2010 National Award of Professional Photography (Spain)- Gold LUX.[2] and Grand Prix Jury's Special Award, Fotofestiwal 2010, Poland.

Max de Esteban (Spain). A fine-art photographer. Holds a Graduate degree from UPC, a Master from Stanford University and a PhD from URL. He is a Fulbright Alumni. His work is organized in two distinct bodies: Elegies of Manumission and Propositions. Awards: the 2010 National Award of Professional Photography (Spain)- Gold LUX.[2] and Grand Prix Jury's Special Award, Fotofestiwal 2010, Poland.ZoneZero

Colombia land of light, consists in a series of symbolic acts of support for victims of violence and those who are displaced in different parts of Colombia, through the medium of photography and art. It is a voice which confronts all the silence and lack of interest in those that have been marginalised and affected by the armed conflict after more than half a century. The selection of locations for the intervention reflects Colombia's rich variety of multicultural groups, regions, landscapes, climate, historical context, traditions and celebrations, geopolitics, as well as social problems and different armed groups.

Santiago Escobar-Jaramillo (Colombia, 1982). Has worked as a photographer and artist in several African, Asian, South-American, European countries and in the United States. His creative work consists of artistic, documentary and urban photography, and reflects on the individual, space, conflict and memory, using a rigorous conceptual and geometrical aesthetic. His work has been shown, nationally and internationally, in over 60 solo and group exhibition, and he has received various awards and distinctions.

Santiago Escobar-Jaramillo (Colombia, 1982). Has worked as a photographer and artist in several African, Asian, South-American, European countries and in the United States. His creative work consists of artistic, documentary and urban photography, and reflects on the individual, space, conflict and memory, using a rigorous conceptual and geometrical aesthetic. His work has been shown, nationally and internationally, in over 60 solo and group exhibition, and he has received various awards and distinctions.Colombia land of light, consists in a series of symbolic acts of support for victims of violence and those who are displaced in different parts of Colombia, through the medium of photography and art. It is a voice which confronts all the silence and lack of interest in those that have been marginalised and affected by the armed conflict after more than half a century. The selection of locations for the intervention reflects Colombia's rich variety of multicultural groups, regions, landscapes, climate, historical context, traditions and celebrations, geopolitics, as well as social problems and different armed groups.

Santiago Escobar-Jaramillo (Colombia, 1982). Has worked as a photographer and artist in several African, Asian, South-American, European countries and in the United States. His creative work consists of artistic, documentary and urban photography, and reflects on the individual, space, conflict and memory, using a rigorous conceptual and geometrical aesthetic. His work has been shown, nationally and internationally, in over 60 solo and group exhibition, and he has received various awards and distinctions.

Santiago Escobar-Jaramillo (Colombia, 1982). Has worked as a photographer and artist in several African, Asian, South-American, European countries and in the United States. His creative work consists of artistic, documentary and urban photography, and reflects on the individual, space, conflict and memory, using a rigorous conceptual and geometrical aesthetic. His work has been shown, nationally and internationally, in over 60 solo and group exhibition, and he has received various awards and distinctions.ZoneZero

Geography of Pain is meant to be a virtual geographical space where the user or visitor can take a tour through different regions of Mexico and can listen to various stories about the events that overwhelmed not only the institutional and political system but also the authorities and the citizens of this country; stories about people who lost their lives, people who went missing.

This web documentary exists thanks to the convergence of documentary film with the interactivity that the new digital media offers. Audiovisual language was mixed with programming language and resulted in new interactive ways of storytelling, namely, the interactive documentary. In this way, this project uses a clear and a direct narrative that allows the viewer to understand the experience of insecurity in Mexico and the cases of missing persons.

Mónica González. Photographer. She studied in UNAM (Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México) at the Political and Sociological Sciences Faculty, the major in Communication Sciences and Journalism. She has worked for the Expansión Magazine, The Dallas Morning News, Newsweek Magazine, Nike, HBO Project 48, NOTIMEX, El Economista newspaper, El Centro journal, VICE Mexico, NFB Canada and currently working as a photographer for the Milenio journal. She won the student grant Jóvenes Creativos (Creative Youth) 2009-2010 given by FONCA CONACULTA due to her project El sentido anatómico (The Anatomic Sense), transsexuality, the new nuclear family. She received the National Journalism Award in 2006 under the category of Photography due to her Migration Coverage of Mexicans in the border of Altar – Sasabe, Sonora, through Arizona’s desert. And in 2011 for her documentary work Geografía del Dolor (Geography of Pain)

Mónica González. Photographer. She studied in UNAM (Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México) at the Political and Sociological Sciences Faculty, the major in Communication Sciences and Journalism. She has worked for the Expansión Magazine, The Dallas Morning News, Newsweek Magazine, Nike, HBO Project 48, NOTIMEX, El Economista newspaper, El Centro journal, VICE Mexico, NFB Canada and currently working as a photographer for the Milenio journal. She won the student grant Jóvenes Creativos (Creative Youth) 2009-2010 given by FONCA CONACULTA due to her project El sentido anatómico (The Anatomic Sense), transsexuality, the new nuclear family. She received the National Journalism Award in 2006 under the category of Photography due to her Migration Coverage of Mexicans in the border of Altar – Sasabe, Sonora, through Arizona’s desert. And in 2011 for her documentary work Geografía del Dolor (Geography of Pain)Geography of Pain is meant to be a virtual geographical space where the user or visitor can take a tour through different regions of Mexico and can listen to various stories about the events that overwhelmed not only the institutional and political system but also the authorities and the citizens of this country; stories about people who lost their lives, people who went missing.

This web documentary exists thanks to the convergence of documentary film with the interactivity that the new digital media offers. Audiovisual language was mixed with programming language and resulted in new interactive ways of storytelling, namely, the interactive documentary. In this way, this project uses a clear and a direct narrative that allows the viewer to understand the experience of insecurity in Mexico and the cases of missing persons.

Mónica González. Photographer. She studied in UNAM (Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México) at the Political and Sociological Sciences Faculty, the major in Communication Sciences and Journalism. She has worked for the Expansión Magazine, The Dallas Morning News, Newsweek Magazine, Nike, HBO Project 48, NOTIMEX, El Economista newspaper, El Centro journal, VICE Mexico, NFB Canada and currently working as a photographer for the Milenio journal. She won the student grant Jóvenes Creativos (Creative Youth) 2009-2010 given by FONCA CONACULTA due to her project El sentido anatómico (The Anatomic Sense), transsexuality, the new nuclear family. She received the National Journalism Award in 2006 under the category of Photography due to her Migration Coverage of Mexicans in the border of Altar – Sasabe, Sonora, through Arizona’s desert. And in 2011 for her documentary work Geografía del Dolor (Geography of Pain)

Mónica González. Photographer. She studied in UNAM (Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México) at the Political and Sociological Sciences Faculty, the major in Communication Sciences and Journalism. She has worked for the Expansión Magazine, The Dallas Morning News, Newsweek Magazine, Nike, HBO Project 48, NOTIMEX, El Economista newspaper, El Centro journal, VICE Mexico, NFB Canada and currently working as a photographer for the Milenio journal. She won the student grant Jóvenes Creativos (Creative Youth) 2009-2010 given by FONCA CONACULTA due to her project El sentido anatómico (The Anatomic Sense), transsexuality, the new nuclear family. She received the National Journalism Award in 2006 under the category of Photography due to her Migration Coverage of Mexicans in the border of Altar – Sasabe, Sonora, through Arizona’s desert. And in 2011 for her documentary work Geografía del Dolor (Geography of Pain)ZoneZero

Interview with Eduardo Muñoz. April 2015

Eduardo Muñoz Ordoqui (Cuba, 1964). Photographer. He received a Bachelor in Fine Arts degree in History of Art from the University of Havana in 1990 and a Master in Fine Arts in Studio Art from the University of Texas at Austin in 2005. He has taught photography for more than nine years in St. Edward’s University at Austin, Texas, where he is currently a Faculty Associate at the Department of Visual Studies. Muñoz-Ordoqui’s photographic work has been exhibited in solo and group shows in Europe, Latin America, China, and United States. He received a John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation Fellowship in 1997, a Cintas Foundation Fellowship in 1998 and in 2007 was chosen for the Artpace International Artist-in-Residence program in San Antonio, Texas, USA. His photographs are held in private and institutional collections in the Americas and Europe.

Eduardo Muñoz Ordoqui (Cuba, 1964). Photographer. He received a Bachelor in Fine Arts degree in History of Art from the University of Havana in 1990 and a Master in Fine Arts in Studio Art from the University of Texas at Austin in 2005. He has taught photography for more than nine years in St. Edward’s University at Austin, Texas, where he is currently a Faculty Associate at the Department of Visual Studies. Muñoz-Ordoqui’s photographic work has been exhibited in solo and group shows in Europe, Latin America, China, and United States. He received a John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation Fellowship in 1997, a Cintas Foundation Fellowship in 1998 and in 2007 was chosen for the Artpace International Artist-in-Residence program in San Antonio, Texas, USA. His photographs are held in private and institutional collections in the Americas and Europe.Interview with Eduardo Muñoz. April 2015

Eduardo Muñoz Ordoqui (Cuba, 1964). Photographer. He received a Bachelor in Fine Arts degree in History of Art from the University of Havana in 1990 and a Master in Fine Arts in Studio Art from the University of Texas at Austin in 2005. He has taught photography for more than nine years in St. Edward’s University at Austin, Texas, where he is currently a Faculty Associate at the Department of Visual Studies. Muñoz-Ordoqui’s photographic work has been exhibited in solo and group shows in Europe, Latin America, China, and United States. He received a John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation Fellowship in 1997, a Cintas Foundation Fellowship in 1998 and in 2007 was chosen for the Artpace International Artist-in-Residence program in San Antonio, Texas, USA. His photographs are held in private and institutional collections in the Americas and Europe.

Eduardo Muñoz Ordoqui (Cuba, 1964). Photographer. He received a Bachelor in Fine Arts degree in History of Art from the University of Havana in 1990 and a Master in Fine Arts in Studio Art from the University of Texas at Austin in 2005. He has taught photography for more than nine years in St. Edward’s University at Austin, Texas, where he is currently a Faculty Associate at the Department of Visual Studies. Muñoz-Ordoqui’s photographic work has been exhibited in solo and group shows in Europe, Latin America, China, and United States. He received a John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation Fellowship in 1997, a Cintas Foundation Fellowship in 1998 and in 2007 was chosen for the Artpace International Artist-in-Residence program in San Antonio, Texas, USA. His photographs are held in private and institutional collections in the Americas and Europe.Gabriel de la Mora

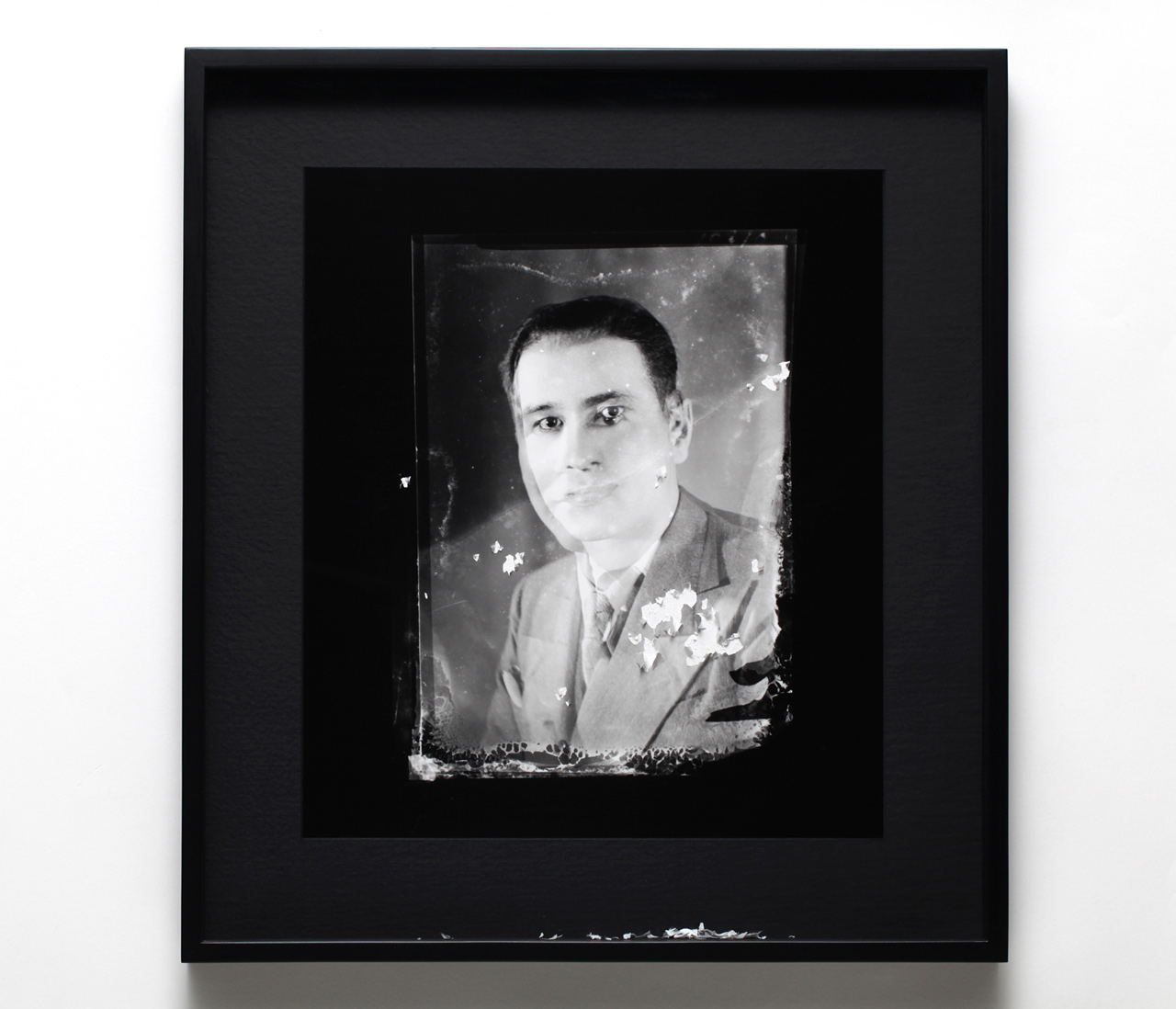

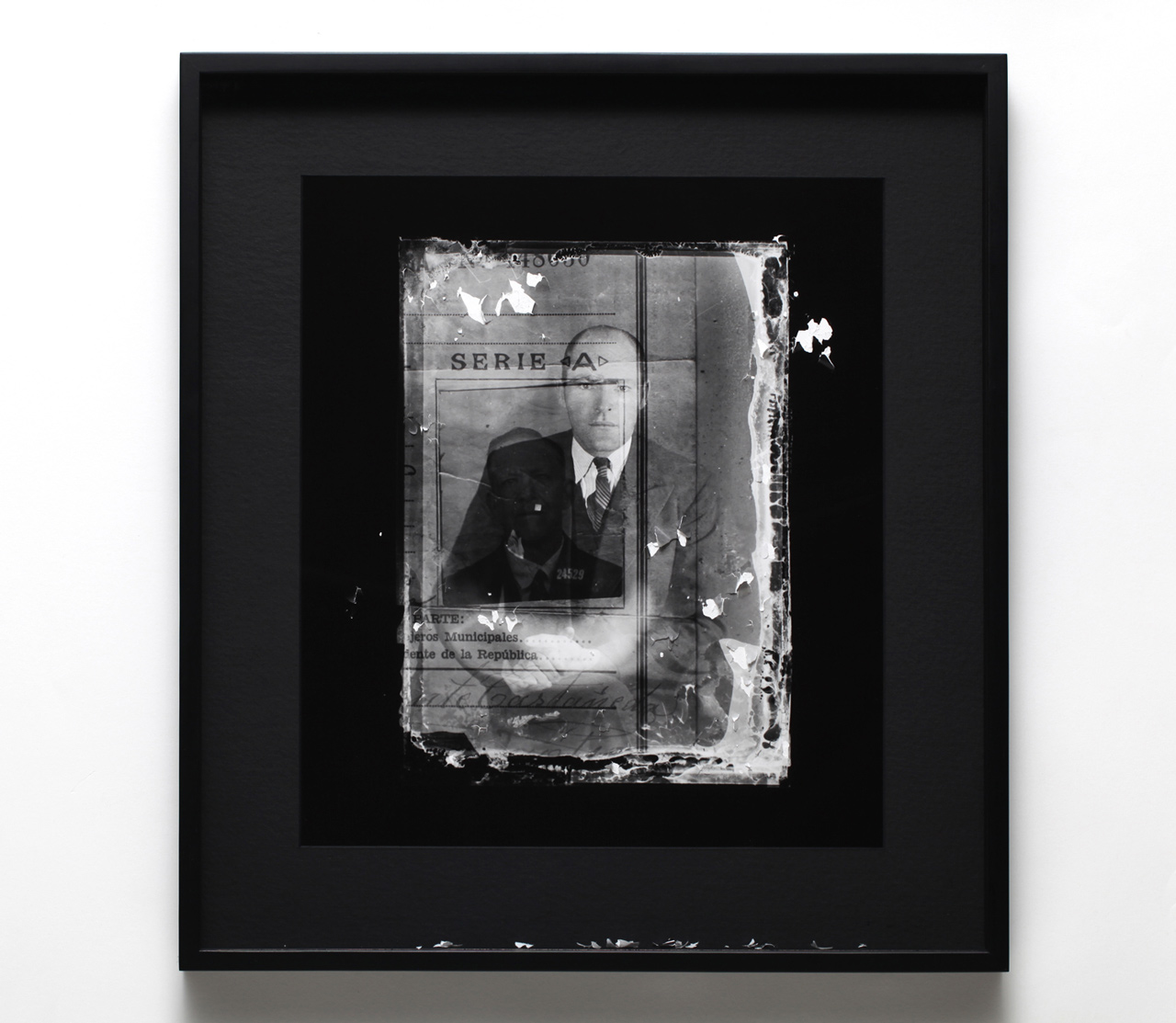

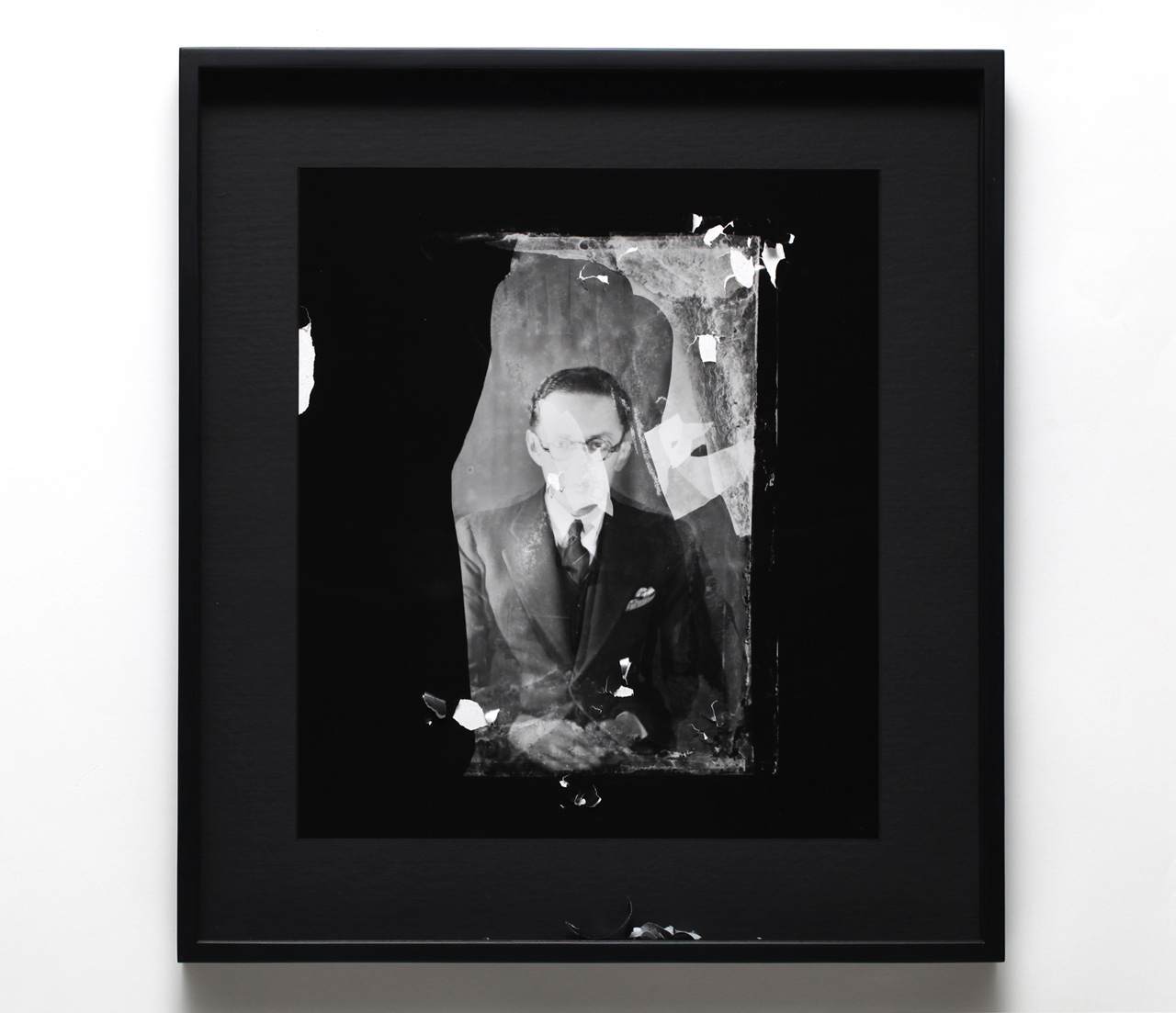

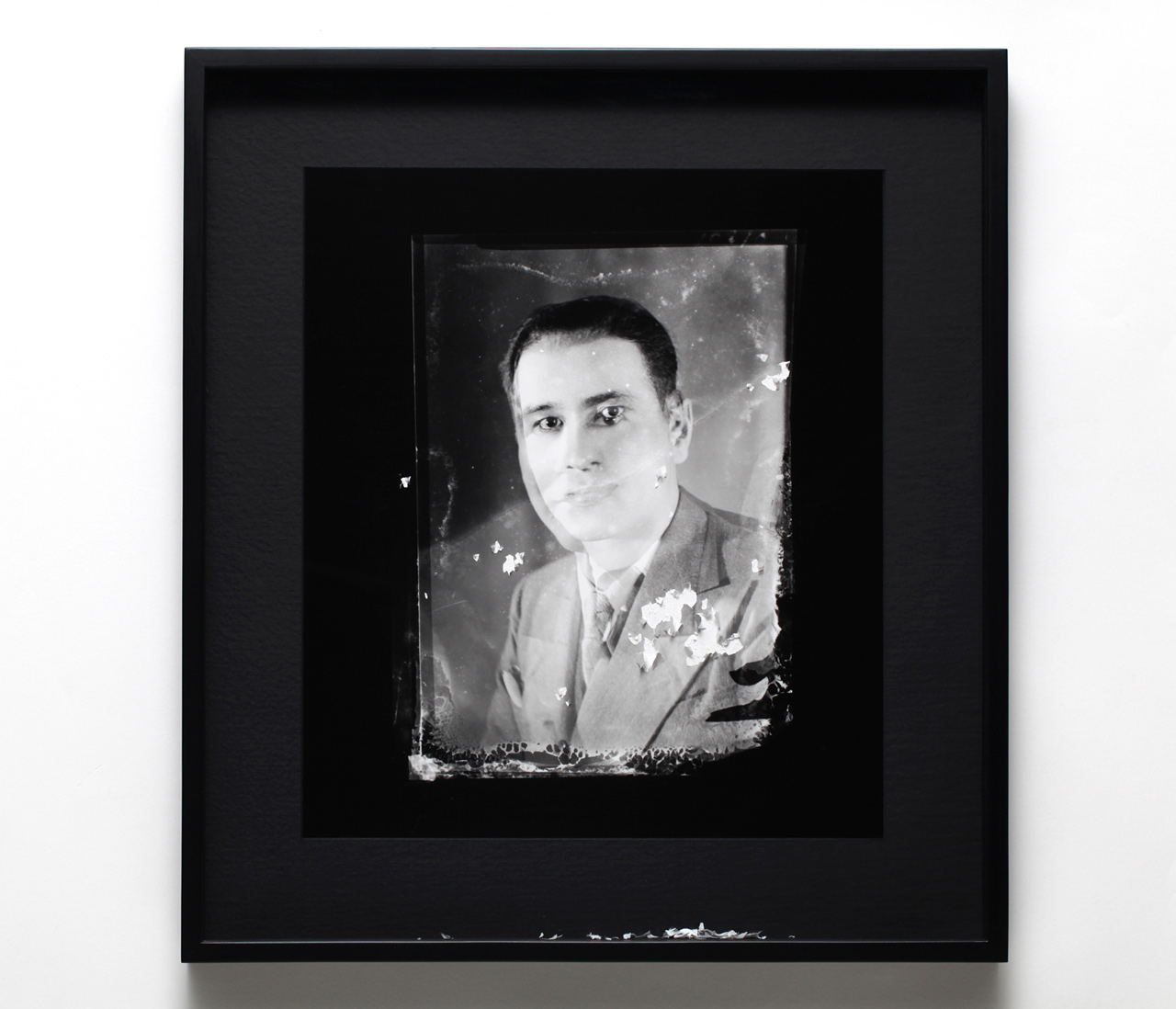

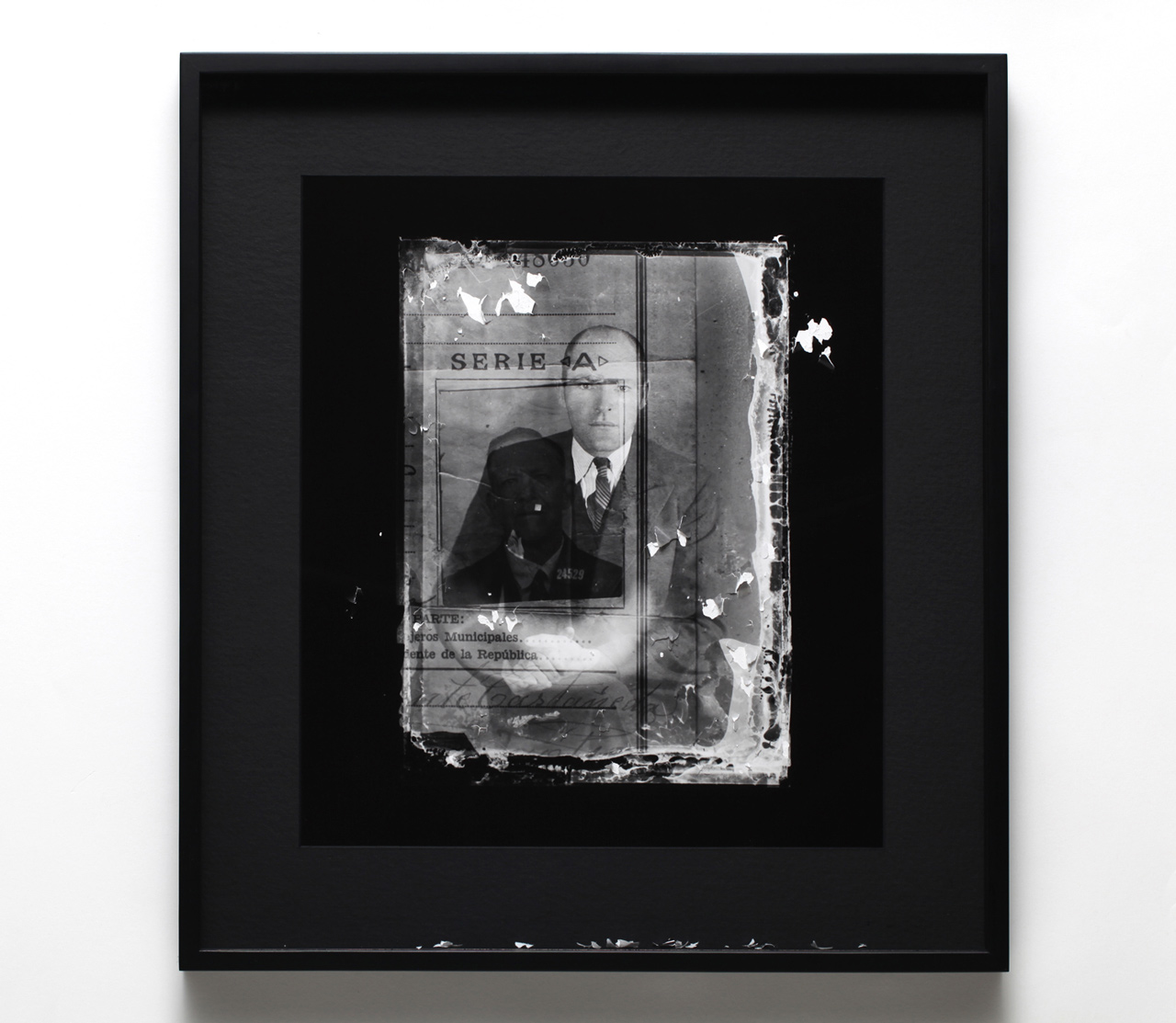

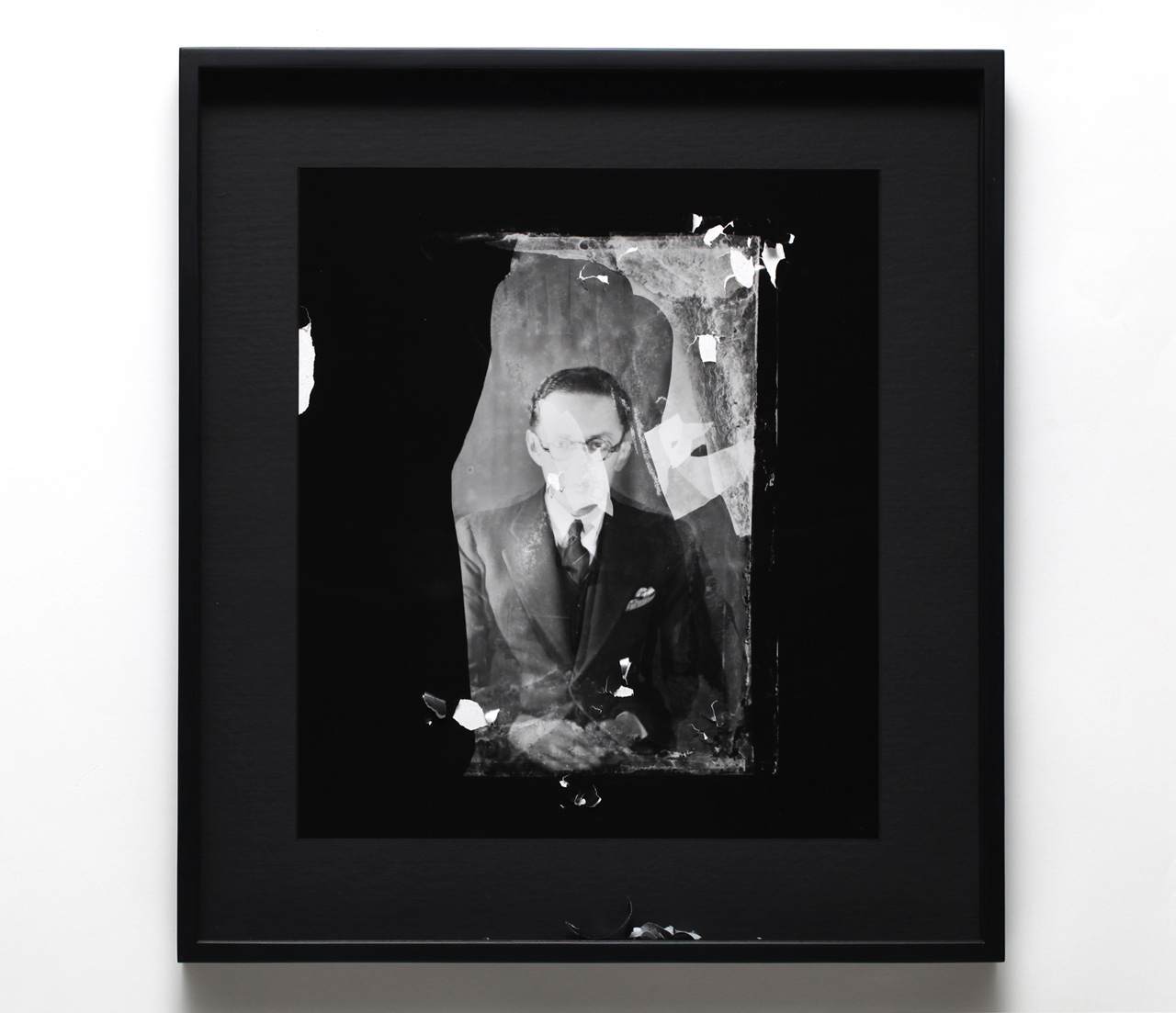

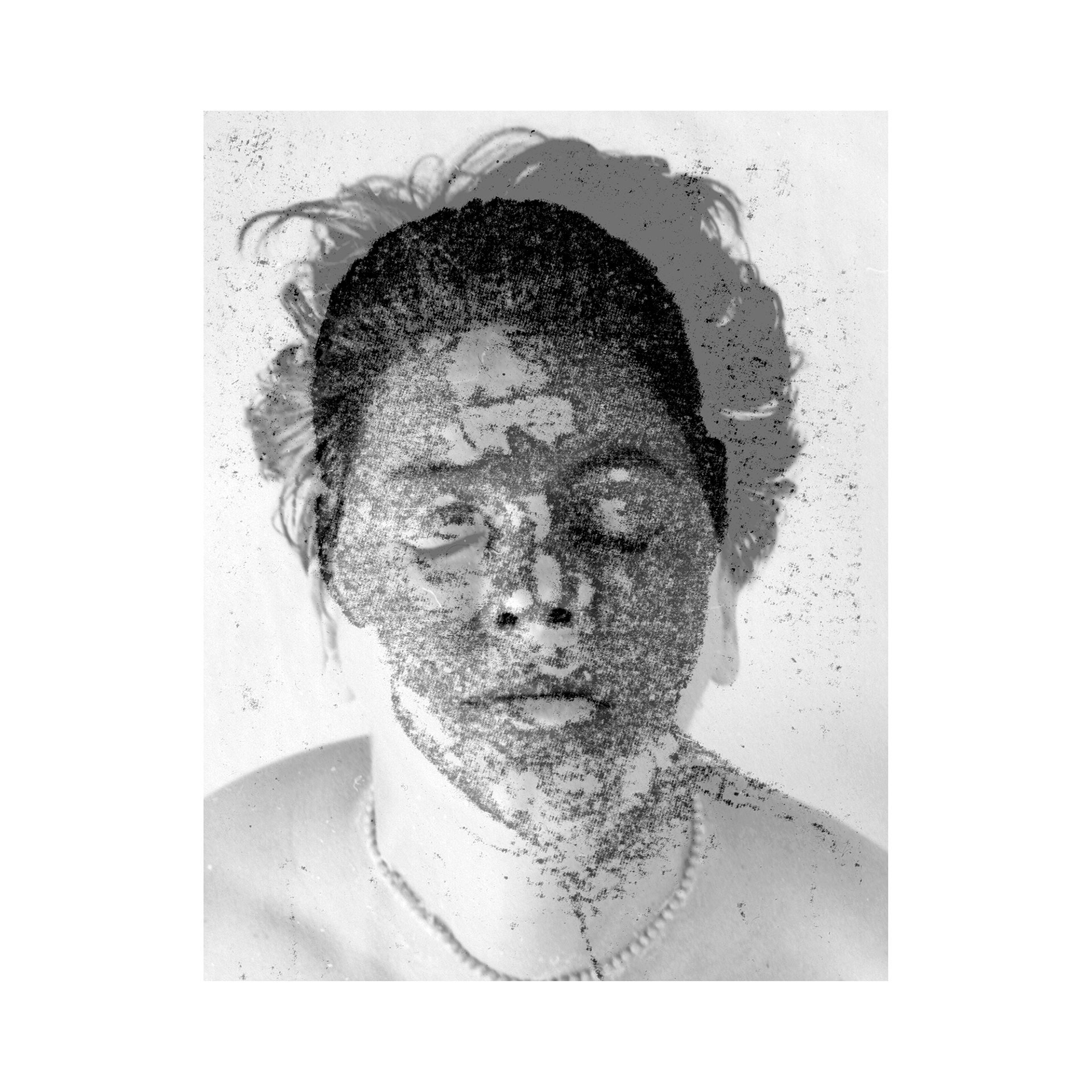

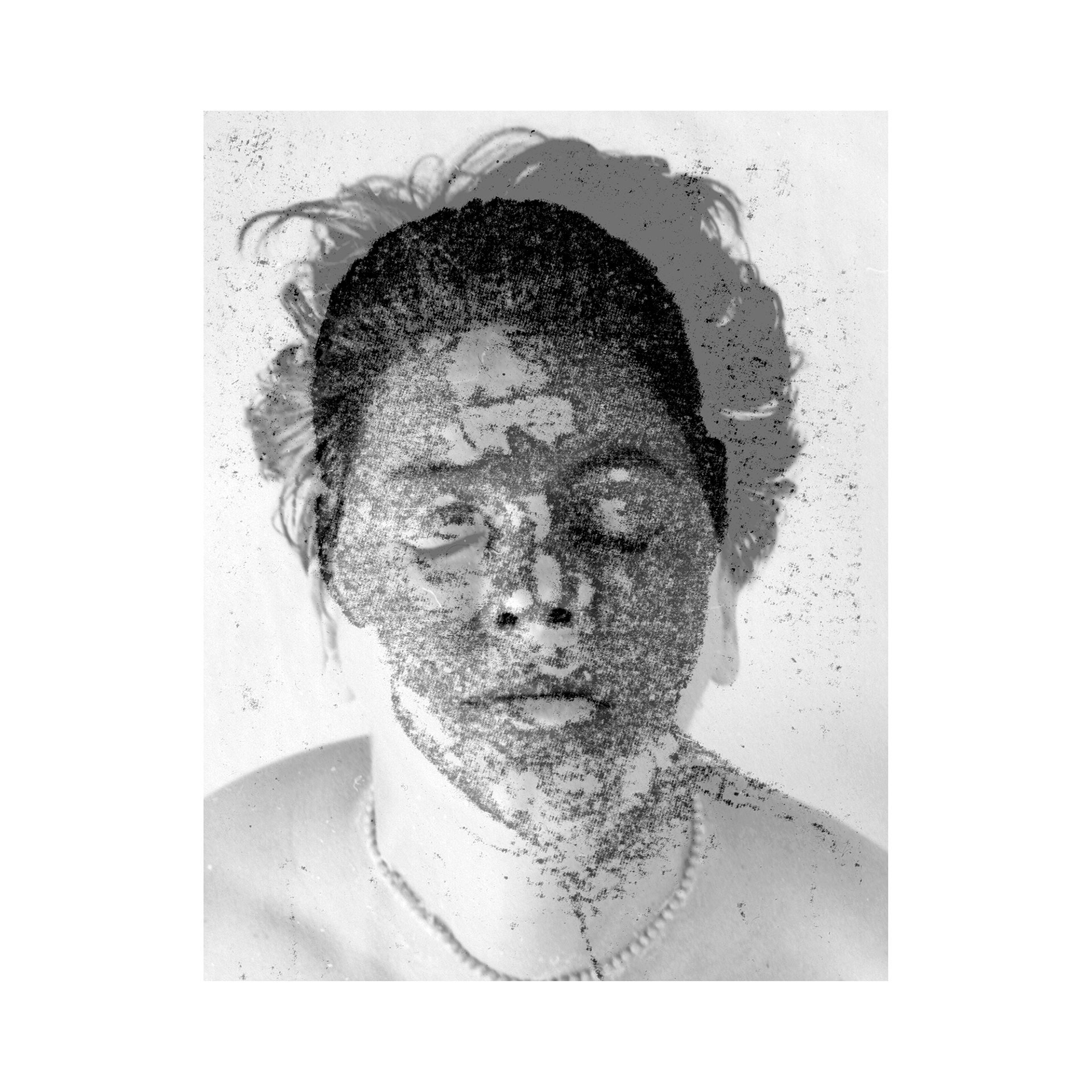

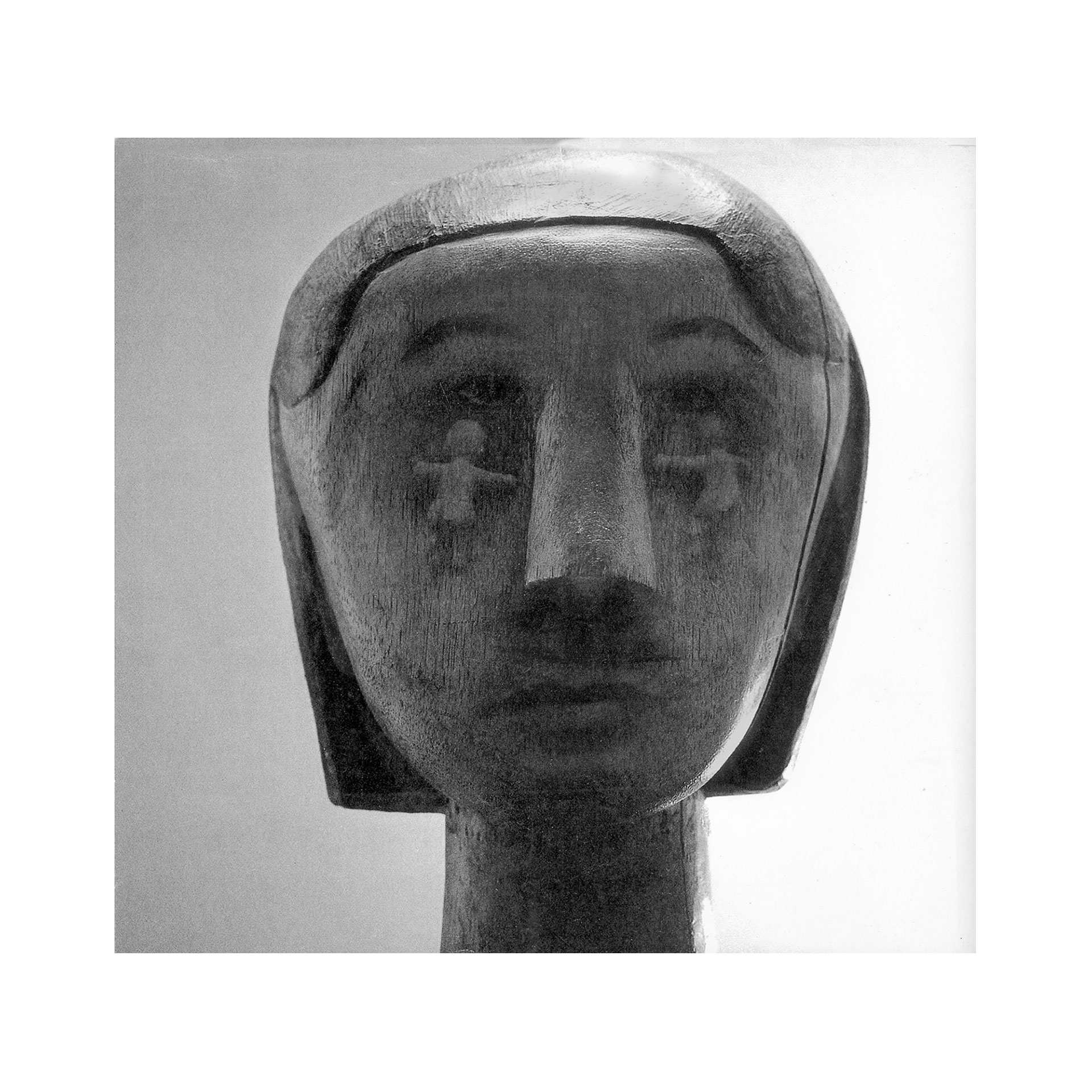

This series of altered photographs comes from a set of negatives that was destroyed when the warehouse where they had been stored for decades was flooded. This is why some of the negatives were stuck together, some of them showing two different takes of the same person and others two or three different people. They are negatives of portraits taken in 1948 and 1949 by Víctor Villamil Vilón at Cano Photography Studios, later called Vilón Photography Studios in Bogotá, Colombia. The images were printed on silver gel with fibrous paper in Mexico City and subsequently altered and framed. The artist begins his work by tearing off pieces of the photo.

Time and light do the rest, erasing the photographic image completely and leaving a monochrome surface. Only then is the work finished. Therefore 50, 100 or 300 years will have to pass, depending on the conditions in which the work is found. The artist never completes the piece and will surely never see it finished. This series is a parallel to the altered space entitled Pan-American Exhibition at NC ARTE.

Gabriel de la Mora (Mexico 1968). Studied a masters in painting, photography and video at the Pratt Institute in New York (2001-2003) and a bachelors in architecture at the Universidad Anáhuac del Norte (1987-1991) in Mexico City. He is currently a member of the Sistema Nacional de Creadores de Arte (2013-2015) and has received a number of awards and grants including the Primer Premio de la VII Bienal de Monterrey FEMSA, the Garcia Robles Fulbright Grant and the Jacques and Natasha Gelman Grant among others. His work as been shown in Mexico and abroad both individually and collectively.

Gabriel de la Mora (Mexico 1968). Studied a masters in painting, photography and video at the Pratt Institute in New York (2001-2003) and a bachelors in architecture at the Universidad Anáhuac del Norte (1987-1991) in Mexico City. He is currently a member of the Sistema Nacional de Creadores de Arte (2013-2015) and has received a number of awards and grants including the Primer Premio de la VII Bienal de Monterrey FEMSA, the Garcia Robles Fulbright Grant and the Jacques and Natasha Gelman Grant among others. His work as been shown in Mexico and abroad both individually and collectively.ZZ. In the project called Archive V.V. 1948 -49 how do you establish the photograph/time relationship? How does it affect the image both as an external and intrinsic element?

GM. Photographic technique is a constantly changing process. Depending upon the passage of time and light, on how the photo has been exposed to these two factors, it can slowly fade and begin to disappear. Which initially worried me for this project. But I think that later this inevitable factor became a starting point for various series in which I used photography as primary or supporting material.

In most of my work, photography is an important element, whether as a file or a document, or a starting point as it was for Willy Kautz in his work shown at the Amparo Museum from October 2014 to February 2015 under the title "What watches us that we don’t see.” The starting point in this exhibit was how an image becomes monochromatic and how a monochrome can become an image.

Although I take photographs to document pieces and processes, amongst many other things, I like to work with vintage photographs from the late 19th to the late 20th century. I buy archives, classify them and then begin my explorations. For the Archive V.V. 1948-49 project I used destroyed negatives for the first time. The alterations were both accidental and due to the passage of time, which produced astounding results.

The Vilón Archive series began in 2012 while I was preparing for my first altered space project at the NC ARTE gallery in Bogotá Colombia. As an alternative activity to the show called Pan-American Exhibition curated by Willy Kautz, I visited an old photography studio near the NC ARTE gallery. I was hoping to find vintage portraits taken in Bogotá in 1948-1949.

Victor Vilón’s children, Germán and Patricia Vilón, who owned the Vilón Photography Studio, told me that although they had no old photographs they did have some negatives which they would look for to show me. Two days later I turned up punctually for our appointment and both Patricia and Germán had a look of utter frustration: they showed me a cardboard box containing hundreds of negatives that had been destroyed by a flood in the warehouse where they had been stored, which no-one had noticed. Patricia showed me various negatives that were stuck together and would break when separated and told me they were going to throw it all away. When I saw some of the negatives, I found them far more interesting than they would have been if they had not got wet. So I asked Germán if they could print the negatives in their destroyed state and he told me that they could, but that they would turn out badly. I chose a few and asked for examples. A couple of days later, these examples exceeded my expectations. Previously, I would buy vintage photographs from Mexican movies and alter them by randomly tearing part of the film to transform the narrative and configuration through a process of abstraction and destruction.

Before destroying each image I would scan both sides so that each altered photograph could be added to my digital archives.

The destroyed negatives from Archive V.V. had not been altered by me, but by an accident that destroyed them over time, so the artistic process for series like the one on Mexican movies was carried out by time rather than by me. The result is simply amazing. To rescue the negatives from the garbage I asked German and Patricia to sell them to me to keep in Mexico where I could continue experimenting with the series of images.

ZZ. How much do you intervene in the construction of a photographic image and at what point is it beyond your control?

GM. As an artist I like to have control over certain pieces or series, but I also like to lose absolute control over other series in particular, or occasionally combine both: control and randomness.

With regards to the destroyed negatives, or Archive V.V. 1948-49, the majority of alterations were made by the flood and time and the results were the starting point for a new series. When printed, the images were extraordinary, unique, and I did not intervene in them at all except for finding and recovering them. It was like a type of assisted Ready Made, as Francisco Reyes Palma so aptly called it. Once the photos had been printed, I altered them again by tearing part of the photographic film off and leaving the fragments at the bottom of the frame. This begins a process that, depending on the conditions in which the photo is stored, time and light, will cause the image to entirely disappear in maybe 50, 100 or more years, transforming the photo into a monochrome white surface. When this finally happens, the piece will be completed. “The artist only begins the piece, but will never see it finished as its process continues over time even after the artist’s death.”

Back in Mexico, I went to a photography laboratory to print the negatives I had chosen on fiber paper in a similar way. Once they were printed, but before framing them, I altered them randomly, tearing bits of photographic film off and saving them so that after the photo had been framed, they would be at the bottom of the frame.

What most interests me is what happens after the first intervention when the destroyed negative is printed. I intervene again by tearing off small pieces of the image, thereby beginning my piece of work, since time, light and varied storage conditions will complete the piece.

ZZ. When the object mediates between the artist and the spectator, what type of reflection does it incite?

GM. At the end of the day, everything vanishes. Nothing is eternal and everything is subject to constant change and transformation. Art is neither created nor destroyed, only transformed.

In my work, I like to introduce the works. They do everything. There is a an interesting visual, formal and technical factor that makes an initial, perhaps more emotional impact. Afterwards, you can explore what goes on behind the process, and the work itself has various levels of information where one question leads to another, and so on, indefinitely.

When something attracts your attention and you like it but it also makes you think, for me, that is the point where the work becomes whole. Each person will have a different opinion or reaction depending on the level and type of previous information they possess. The images or works in this series, for example, have received differing opinions and reflections. In some people they elicit nostalgia for an era, a person who no longer exists or who died years ago; for others, it produces a certain mystery, or even fear, since some of the faces or images are rather ghostlike.

Personally, I believe that the images are powerful in every respect. They have an extraordinary composition and were, in a way, part of an archive which, when it was destroyed, fulfilled its destiny by becoming waste. This is a footnote for me as an artist, knowing that what comes at the end of one thing can be the beginning of another. This waste or residual material can be transformed into artwork.

When two or more negatives in the archive are stuck together and then break and are fragmented into other images, the way I print them turns them into something extraordinary. They have been altered by time, through a naturally destructive process, making the image into an abstraction with a strange composition. The people still exist in them, or their presence is registered, together with a whole era. Thus the images are historic documents that are transformed into something else.

The original author of these portraits was Don Victor Villamil Vilón, and now I am the author. I love to find new ways of experimenting with photography. I did not originally take these photographs, but I did rescue them from the becoming garbage after they had been destroyed in a flood and now they are prime examples for exploring image through records, archives and documents.

This series of altered photographs comes from a set of negatives that was destroyed when the warehouse where they had been stored for decades was flooded. This is why some of the negatives were stuck together, some of them showing two different takes of the same person and others two or three different people. They are negatives of portraits taken in 1948 and 1949 by Víctor Villamil Vilón at Cano Photography Studios, later called Vilón Photography Studios in Bogotá, Colombia. The images were printed on silver gel with fibrous paper in Mexico City and subsequently altered and framed. The artist begins his work by tearing off pieces of the photo.

Time and light do the rest, erasing the photographic image completely and leaving a monochrome surface. Only then is the work finished. Therefore 50, 100 or 300 years will have to pass, depending on the conditions in which the work is found. The artist never completes the piece and will surely never see it finished. This series is a parallel to the altered space entitled Pan-American Exhibition at NC ARTE.

Gabriel de la Mora (Mexico 1968). Studied a masters in painting, photography and video at the Pratt Institute in New York (2001-2003) and a bachelors in architecture at the Universidad Anáhuac del Norte (1987-1991) in Mexico City. He is currently a member of the Sistema Nacional de Creadores de Arte (2013-2015) and has received a number of awards and grants including the Primer Premio de la VII Bienal de Monterrey FEMSA, the Garcia Robles Fulbright Grant and the Jacques and Natasha Gelman Grant among others. His work as been shown in Mexico and abroad both individually and collectively.

Gabriel de la Mora (Mexico 1968). Studied a masters in painting, photography and video at the Pratt Institute in New York (2001-2003) and a bachelors in architecture at the Universidad Anáhuac del Norte (1987-1991) in Mexico City. He is currently a member of the Sistema Nacional de Creadores de Arte (2013-2015) and has received a number of awards and grants including the Primer Premio de la VII Bienal de Monterrey FEMSA, the Garcia Robles Fulbright Grant and the Jacques and Natasha Gelman Grant among others. His work as been shown in Mexico and abroad both individually and collectively.ZZ. In the project called Archive V.V. 1948 -49 how do you establish the photograph/time relationship? How does it affect the image both as an external and intrinsic element?

GM. Photographic technique is a constantly changing process. Depending upon the passage of time and light, on how the photo has been exposed to these two factors, it can slowly fade and begin to disappear. Which initially worried me for this project. But I think that later this inevitable factor became a starting point for various series in which I used photography as primary or supporting material.

In most of my work, photography is an important element, whether as a file or a document, or a starting point as it was for Willy Kautz in his work shown at the Amparo Museum from October 2014 to February 2015 under the title "What watches us that we don’t see.” The starting point in this exhibit was how an image becomes monochromatic and how a monochrome can become an image.

Although I take photographs to document pieces and processes, amongst many other things, I like to work with vintage photographs from the late 19th to the late 20th century. I buy archives, classify them and then begin my explorations. For the Archive V.V. 1948-49 project I used destroyed negatives for the first time. The alterations were both accidental and due to the passage of time, which produced astounding results.

The Vilón Archive series began in 2012 while I was preparing for my first altered space project at the NC ARTE gallery in Bogotá Colombia. As an alternative activity to the show called Pan-American Exhibition curated by Willy Kautz, I visited an old photography studio near the NC ARTE gallery. I was hoping to find vintage portraits taken in Bogotá in 1948-1949.

Victor Vilón’s children, Germán and Patricia Vilón, who owned the Vilón Photography Studio, told me that although they had no old photographs they did have some negatives which they would look for to show me. Two days later I turned up punctually for our appointment and both Patricia and Germán had a look of utter frustration: they showed me a cardboard box containing hundreds of negatives that had been destroyed by a flood in the warehouse where they had been stored, which no-one had noticed. Patricia showed me various negatives that were stuck together and would break when separated and told me they were going to throw it all away. When I saw some of the negatives, I found them far more interesting than they would have been if they had not got wet. So I asked Germán if they could print the negatives in their destroyed state and he told me that they could, but that they would turn out badly. I chose a few and asked for examples. A couple of days later, these examples exceeded my expectations. Previously, I would buy vintage photographs from Mexican movies and alter them by randomly tearing part of the film to transform the narrative and configuration through a process of abstraction and destruction.

Before destroying each image I would scan both sides so that each altered photograph could be added to my digital archives.

The destroyed negatives from Archive V.V. had not been altered by me, but by an accident that destroyed them over time, so the artistic process for series like the one on Mexican movies was carried out by time rather than by me. The result is simply amazing. To rescue the negatives from the garbage I asked German and Patricia to sell them to me to keep in Mexico where I could continue experimenting with the series of images.

ZZ. How much do you intervene in the construction of a photographic image and at what point is it beyond your control?

GM. As an artist I like to have control over certain pieces or series, but I also like to lose absolute control over other series in particular, or occasionally combine both: control and randomness.

With regards to the destroyed negatives, or Archive V.V. 1948-49, the majority of alterations were made by the flood and time and the results were the starting point for a new series. When printed, the images were extraordinary, unique, and I did not intervene in them at all except for finding and recovering them. It was like a type of assisted Ready Made, as Francisco Reyes Palma so aptly called it. Once the photos had been printed, I altered them again by tearing part of the photographic film off and leaving the fragments at the bottom of the frame. This begins a process that, depending on the conditions in which the photo is stored, time and light, will cause the image to entirely disappear in maybe 50, 100 or more years, transforming the photo into a monochrome white surface. When this finally happens, the piece will be completed. “The artist only begins the piece, but will never see it finished as its process continues over time even after the artist’s death.”

Back in Mexico, I went to a photography laboratory to print the negatives I had chosen on fiber paper in a similar way. Once they were printed, but before framing them, I altered them randomly, tearing bits of photographic film off and saving them so that after the photo had been framed, they would be at the bottom of the frame.

What most interests me is what happens after the first intervention when the destroyed negative is printed. I intervene again by tearing off small pieces of the image, thereby beginning my piece of work, since time, light and varied storage conditions will complete the piece.

ZZ. When the object mediates between the artist and the spectator, what type of reflection does it incite?

GM. At the end of the day, everything vanishes. Nothing is eternal and everything is subject to constant change and transformation. Art is neither created nor destroyed, only transformed.

In my work, I like to introduce the works. They do everything. There is a an interesting visual, formal and technical factor that makes an initial, perhaps more emotional impact. Afterwards, you can explore what goes on behind the process, and the work itself has various levels of information where one question leads to another, and so on, indefinitely.

When something attracts your attention and you like it but it also makes you think, for me, that is the point where the work becomes whole. Each person will have a different opinion or reaction depending on the level and type of previous information they possess. The images or works in this series, for example, have received differing opinions and reflections. In some people they elicit nostalgia for an era, a person who no longer exists or who died years ago; for others, it produces a certain mystery, or even fear, since some of the faces or images are rather ghostlike.

Personally, I believe that the images are powerful in every respect. They have an extraordinary composition and were, in a way, part of an archive which, when it was destroyed, fulfilled its destiny by becoming waste. This is a footnote for me as an artist, knowing that what comes at the end of one thing can be the beginning of another. This waste or residual material can be transformed into artwork.

When two or more negatives in the archive are stuck together and then break and are fragmented into other images, the way I print them turns them into something extraordinary. They have been altered by time, through a naturally destructive process, making the image into an abstraction with a strange composition. The people still exist in them, or their presence is registered, together with a whole era. Thus the images are historic documents that are transformed into something else.

The original author of these portraits was Don Victor Villamil Vilón, and now I am the author. I love to find new ways of experimenting with photography. I did not originally take these photographs, but I did rescue them from the becoming garbage after they had been destroyed in a flood and now they are prime examples for exploring image through records, archives and documents.

ZoneZero

Interview with Caspar Sonnen about interactive storytelling. February 2015

Caspar Sonnen. Studied New Media and Film at Utrecht University. He has worked for film and media art festivals. In 2003, he co-founded Seize the Night, an open air film festival in Amsterdam. In 2005, Sonnen became the new media coordinator for the International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam (IDFA). In 2008, he launched IDFA DocLab. The program quickly grew into an international platform for interactive webdocs and other new genres where digital technology and documentary storytelling converge.

Caspar Sonnen. Studied New Media and Film at Utrecht University. He has worked for film and media art festivals. In 2003, he co-founded Seize the Night, an open air film festival in Amsterdam. In 2005, Sonnen became the new media coordinator for the International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam (IDFA). In 2008, he launched IDFA DocLab. The program quickly grew into an international platform for interactive webdocs and other new genres where digital technology and documentary storytelling converge.Interview with Caspar Sonnen about interactive storytelling. February 2015

Caspar Sonnen. Studied New Media and Film at Utrecht University. He has worked for film and media art festivals. In 2003, he co-founded Seize the Night, an open air film festival in Amsterdam. In 2005, Sonnen became the new media coordinator for the International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam (IDFA). In 2008, he launched IDFA DocLab. The program quickly grew into an international platform for interactive webdocs and other new genres where digital technology and documentary storytelling converge.

Caspar Sonnen. Studied New Media and Film at Utrecht University. He has worked for film and media art festivals. In 2003, he co-founded Seize the Night, an open air film festival in Amsterdam. In 2005, Sonnen became the new media coordinator for the International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam (IDFA). In 2008, he launched IDFA DocLab. The program quickly grew into an international platform for interactive webdocs and other new genres where digital technology and documentary storytelling converge.ZoneZero

Interview with Virgil Widrich about his work. February 2015

Virgil Widrich (Salzburg, 1967). Lives in Vienna. He works on numerous multimedia and film productions. His first feature film is Heller als der Mond (Brighter than the Moon). His short film Copy Shop won 35 international awards and was nominated for the Oscar. Fast Film premiered in Cannes 2003 and won 36 awards until today. At the moment Widrich is working on a new feature film The Night of a Thousand Hours.

Virgil Widrich (Salzburg, 1967). Lives in Vienna. He works on numerous multimedia and film productions. His first feature film is Heller als der Mond (Brighter than the Moon). His short film Copy Shop won 35 international awards and was nominated for the Oscar. Fast Film premiered in Cannes 2003 and won 36 awards until today. At the moment Widrich is working on a new feature film The Night of a Thousand Hours.Interview with Virgil Widrich about his work. February 2015

Virgil Widrich (Salzburg, 1967). Lives in Vienna. He works on numerous multimedia and film productions. His first feature film is Heller als der Mond (Brighter than the Moon). His short film Copy Shop won 35 international awards and was nominated for the Oscar. Fast Film premiered in Cannes 2003 and won 36 awards until today. At the moment Widrich is working on a new feature film The Night of a Thousand Hours.

Virgil Widrich (Salzburg, 1967). Lives in Vienna. He works on numerous multimedia and film productions. His first feature film is Heller als der Mond (Brighter than the Moon). His short film Copy Shop won 35 international awards and was nominated for the Oscar. Fast Film premiered in Cannes 2003 and won 36 awards until today. At the moment Widrich is working on a new feature film The Night of a Thousand Hours.Marta María Pérez

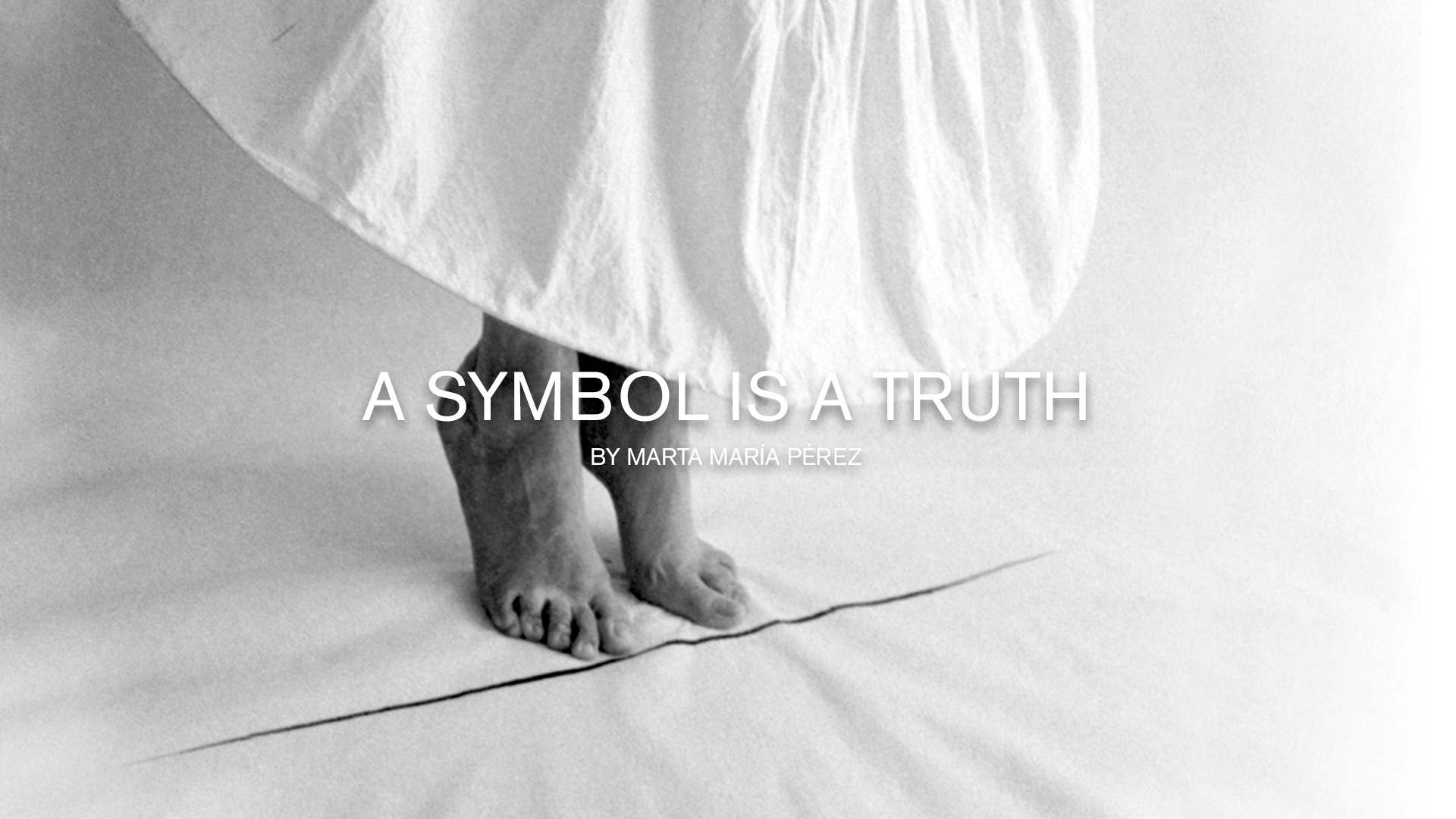

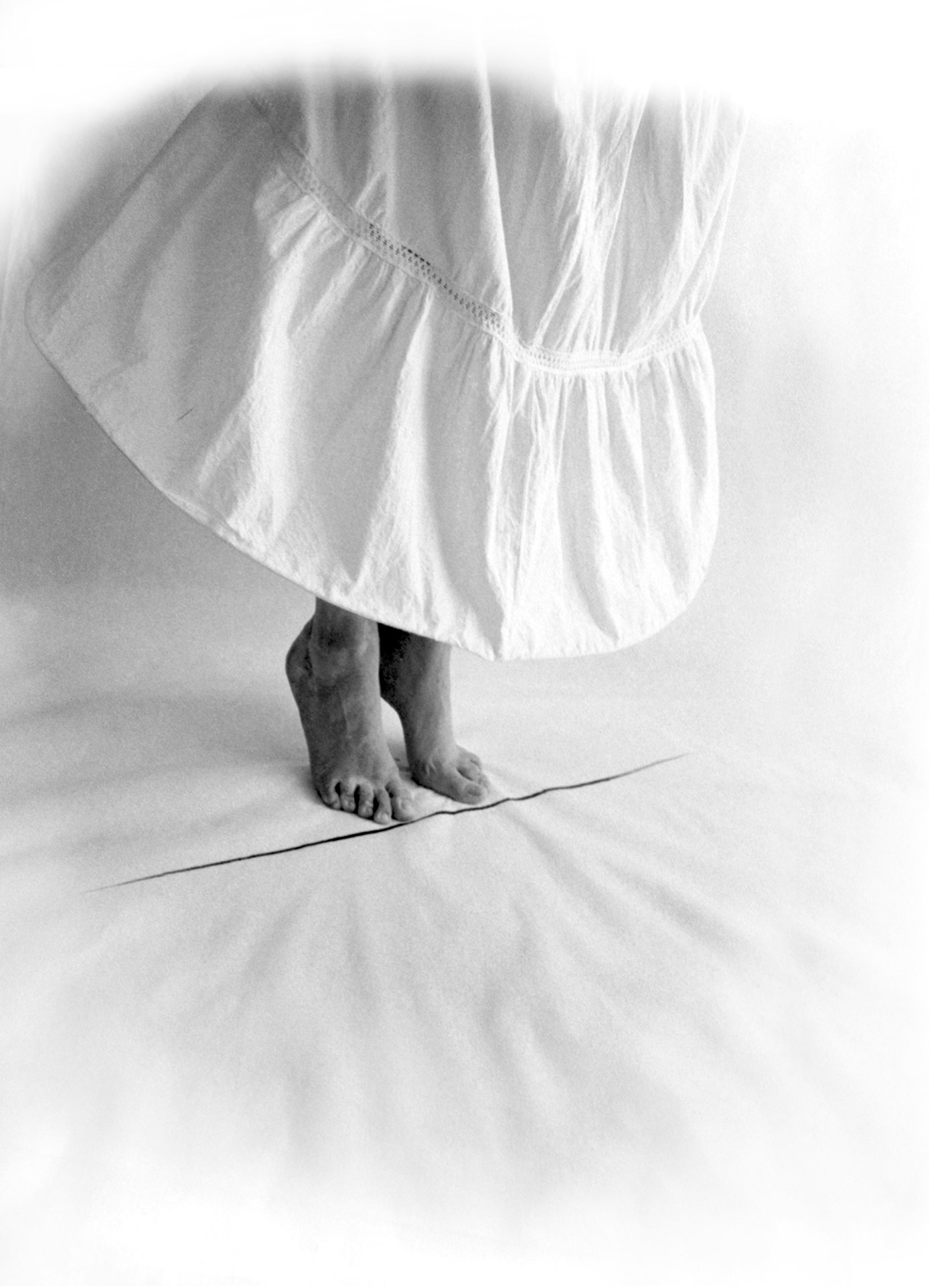

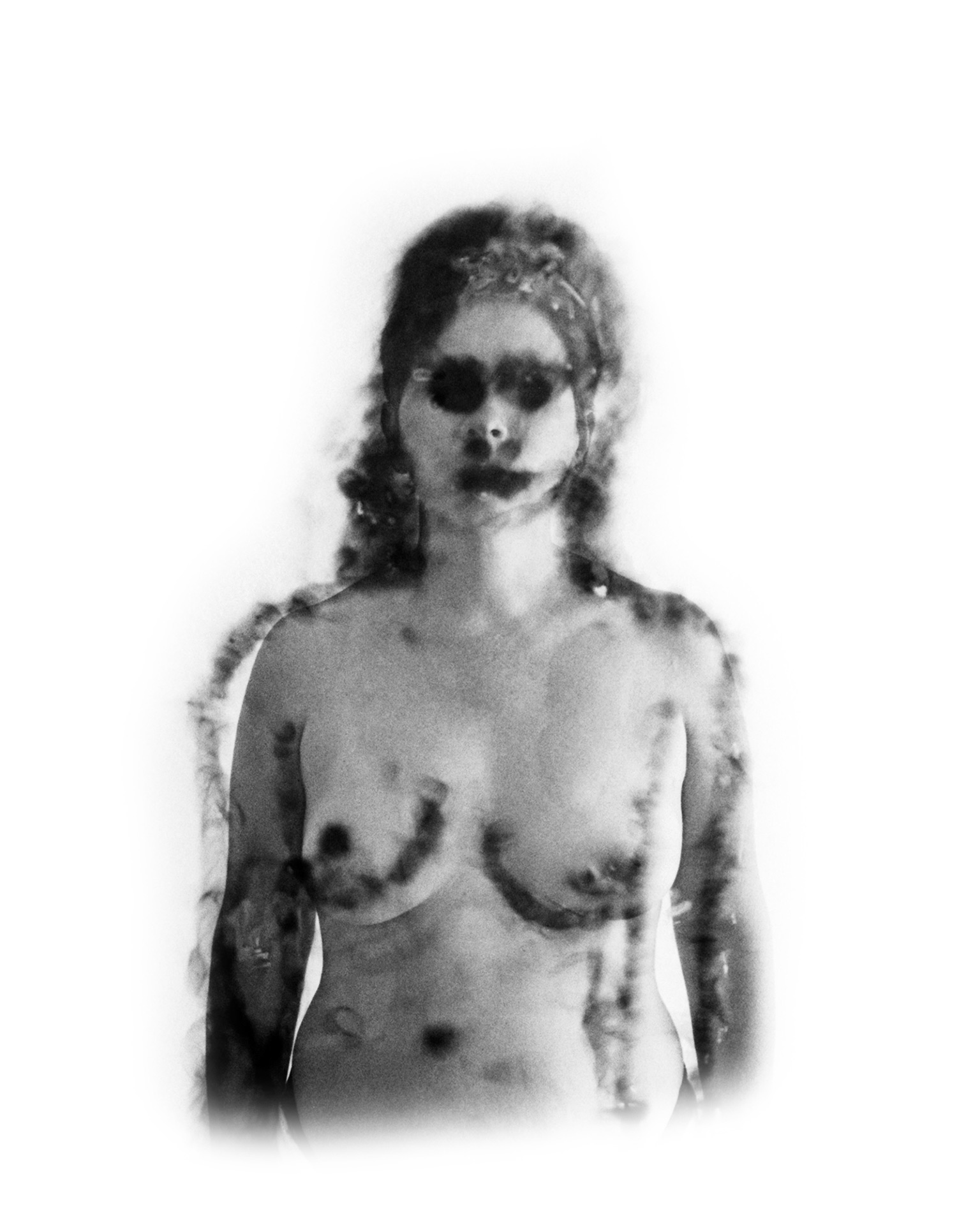

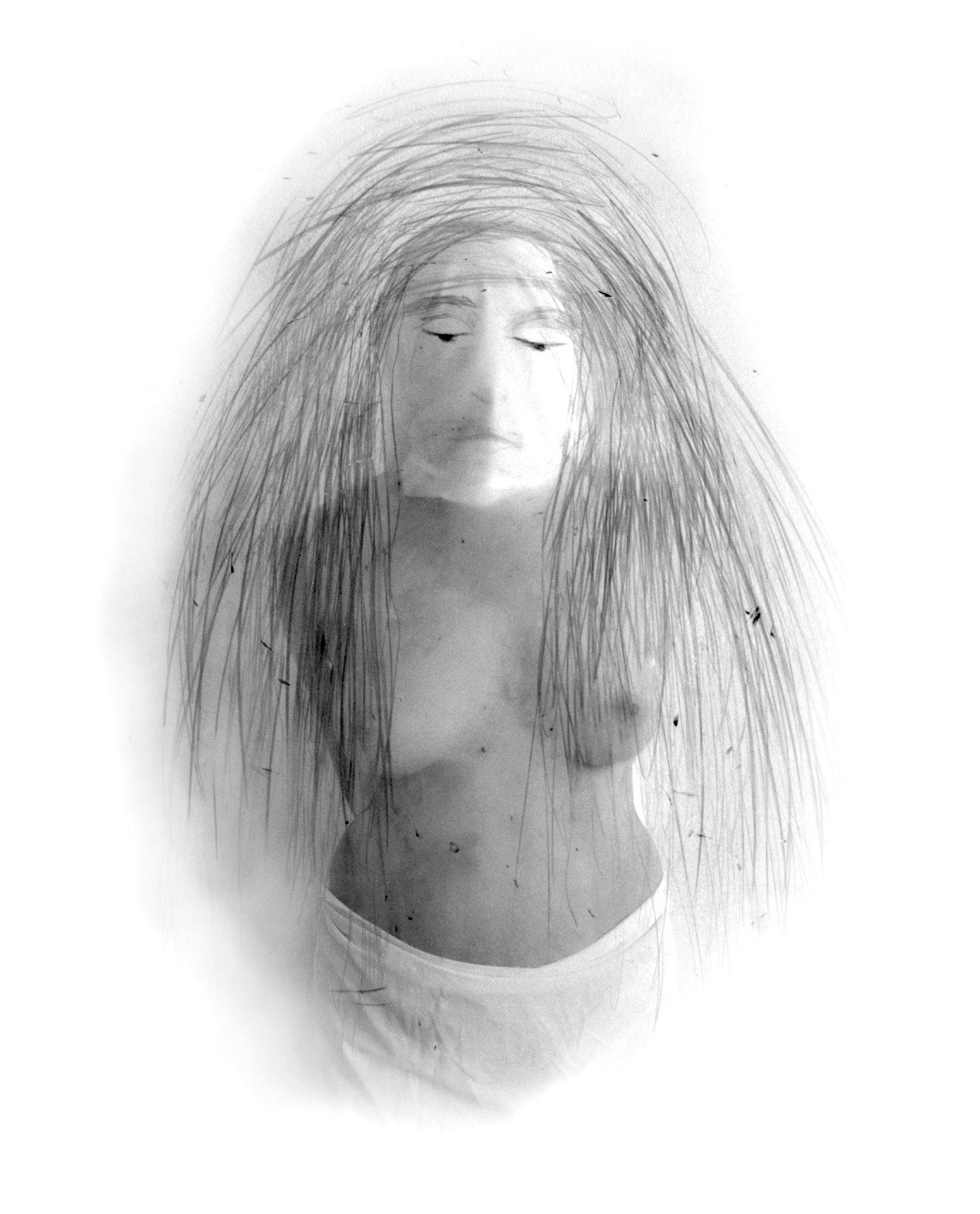

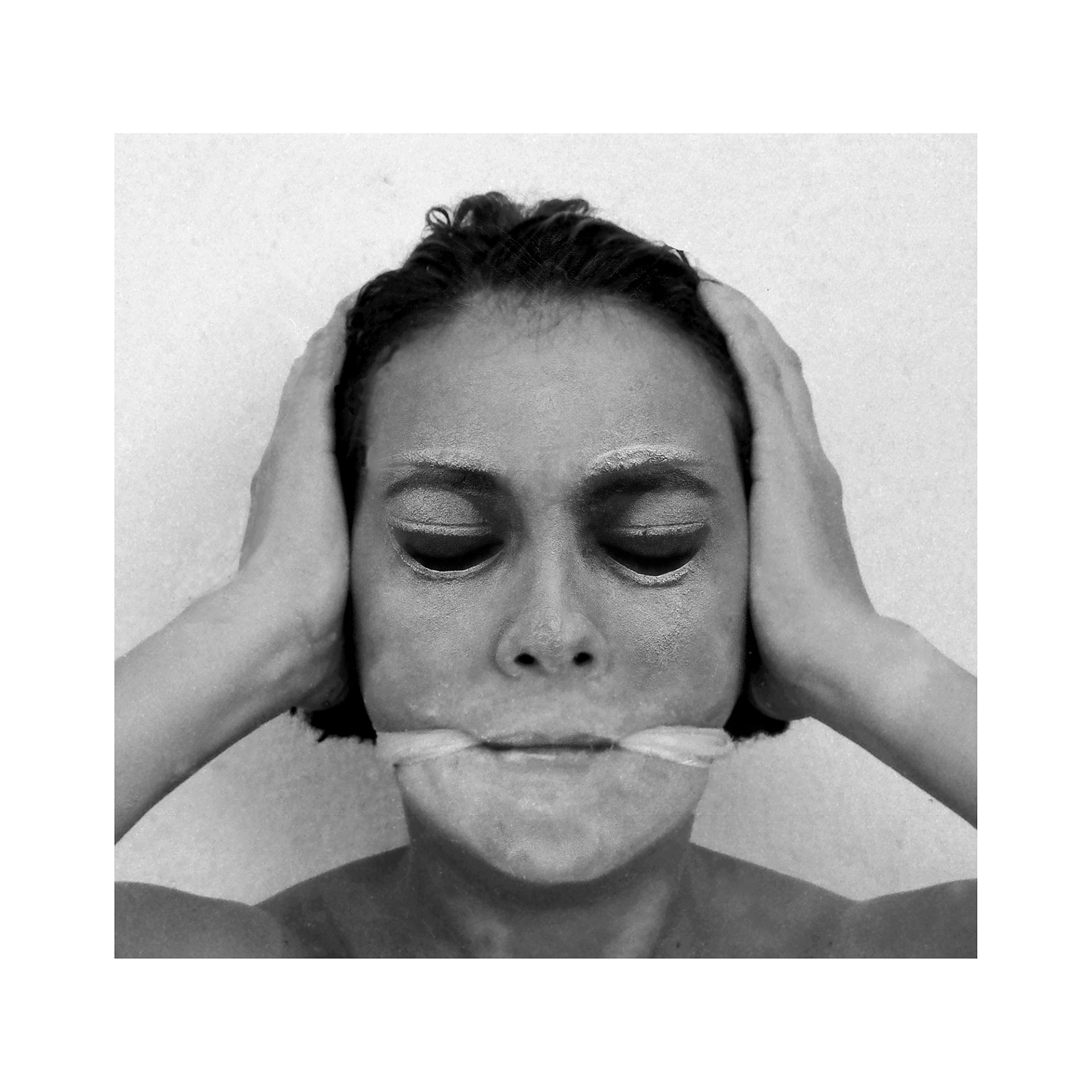

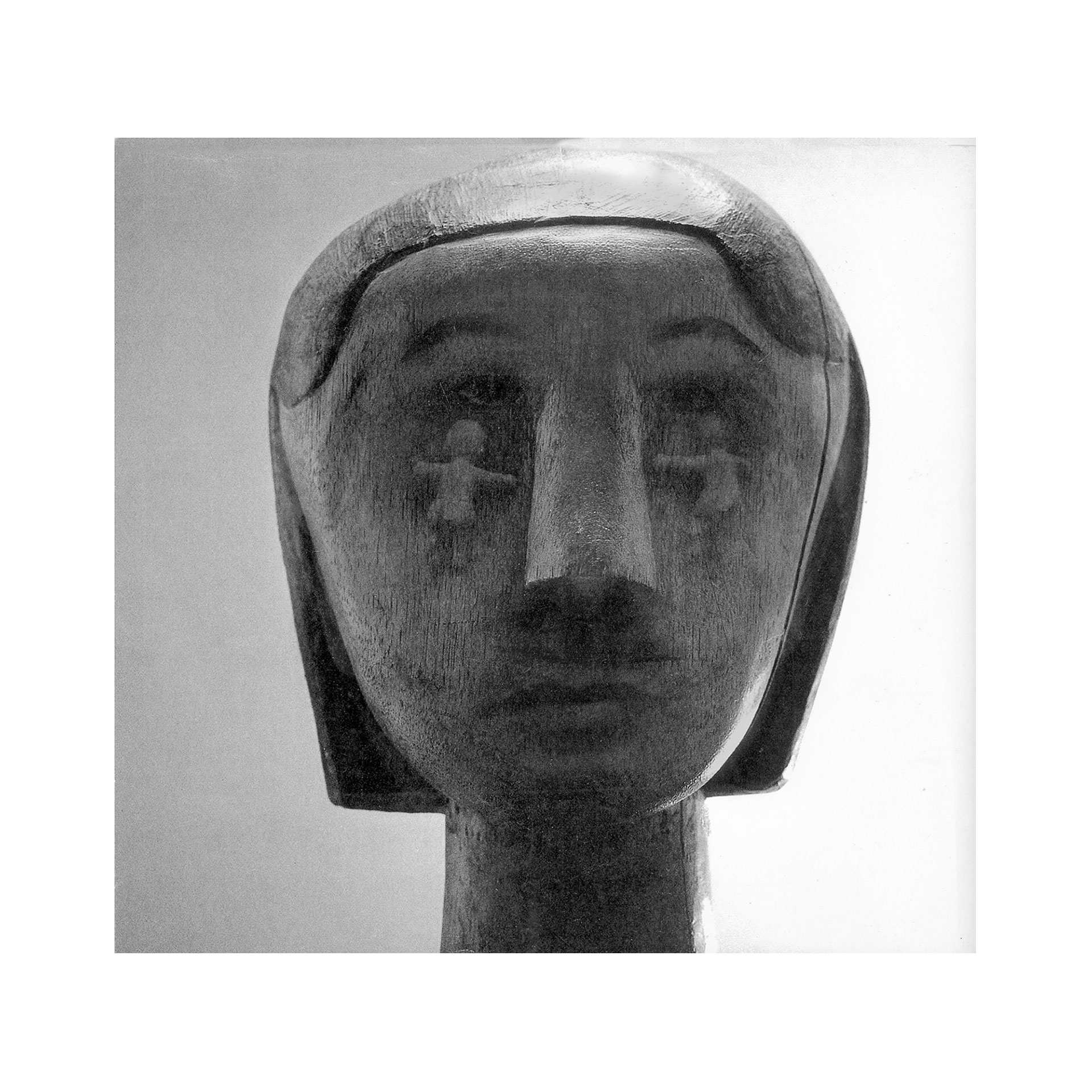

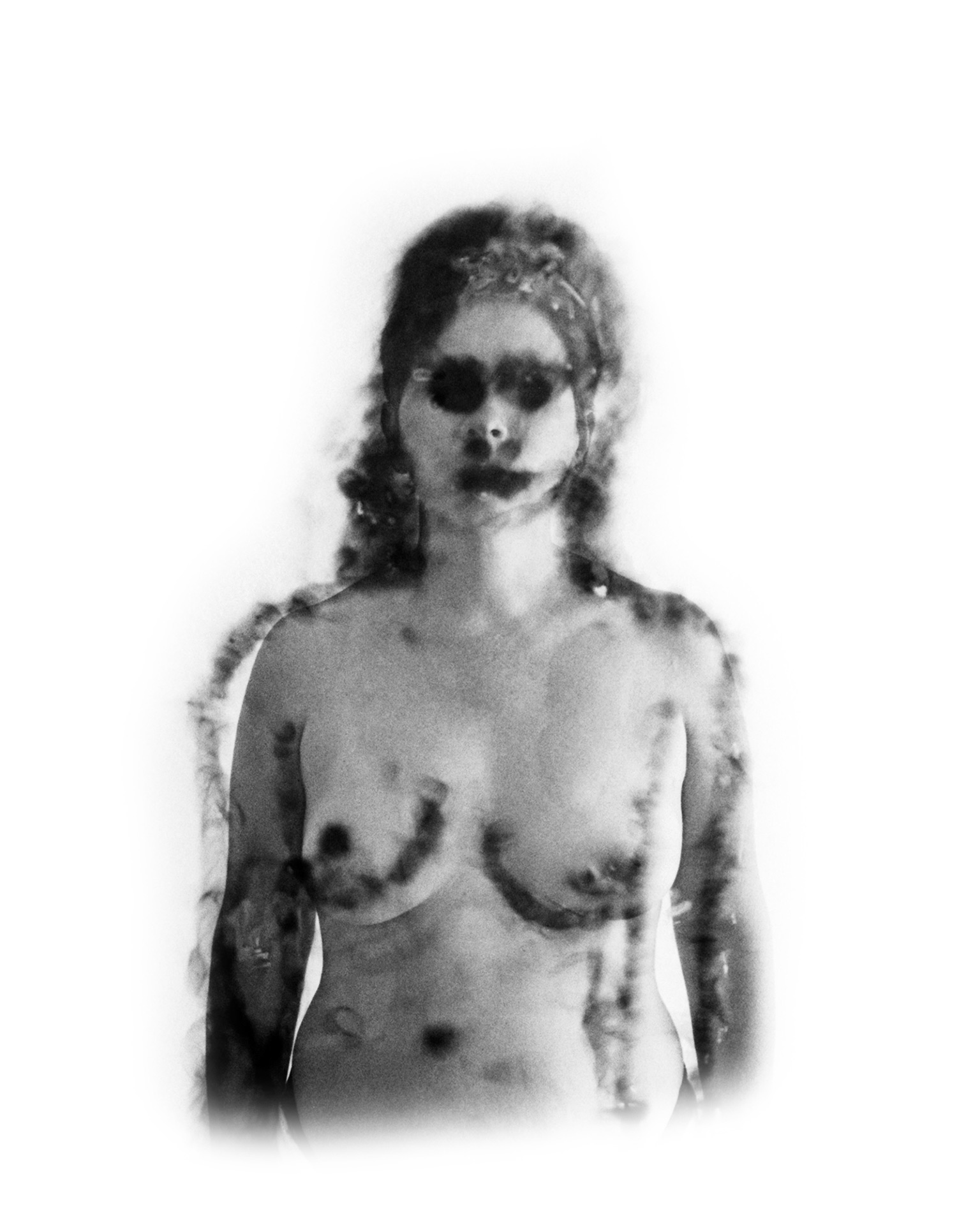

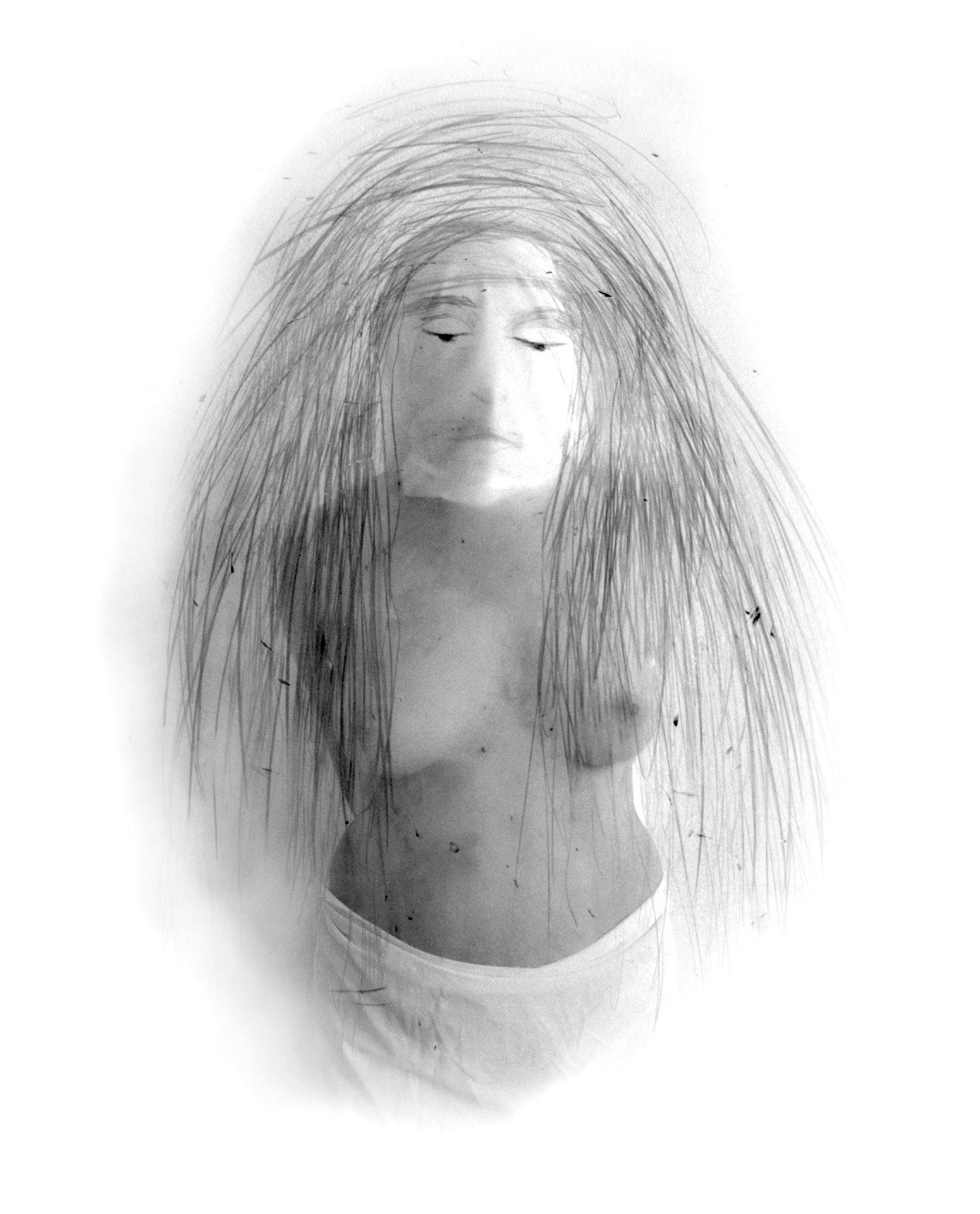

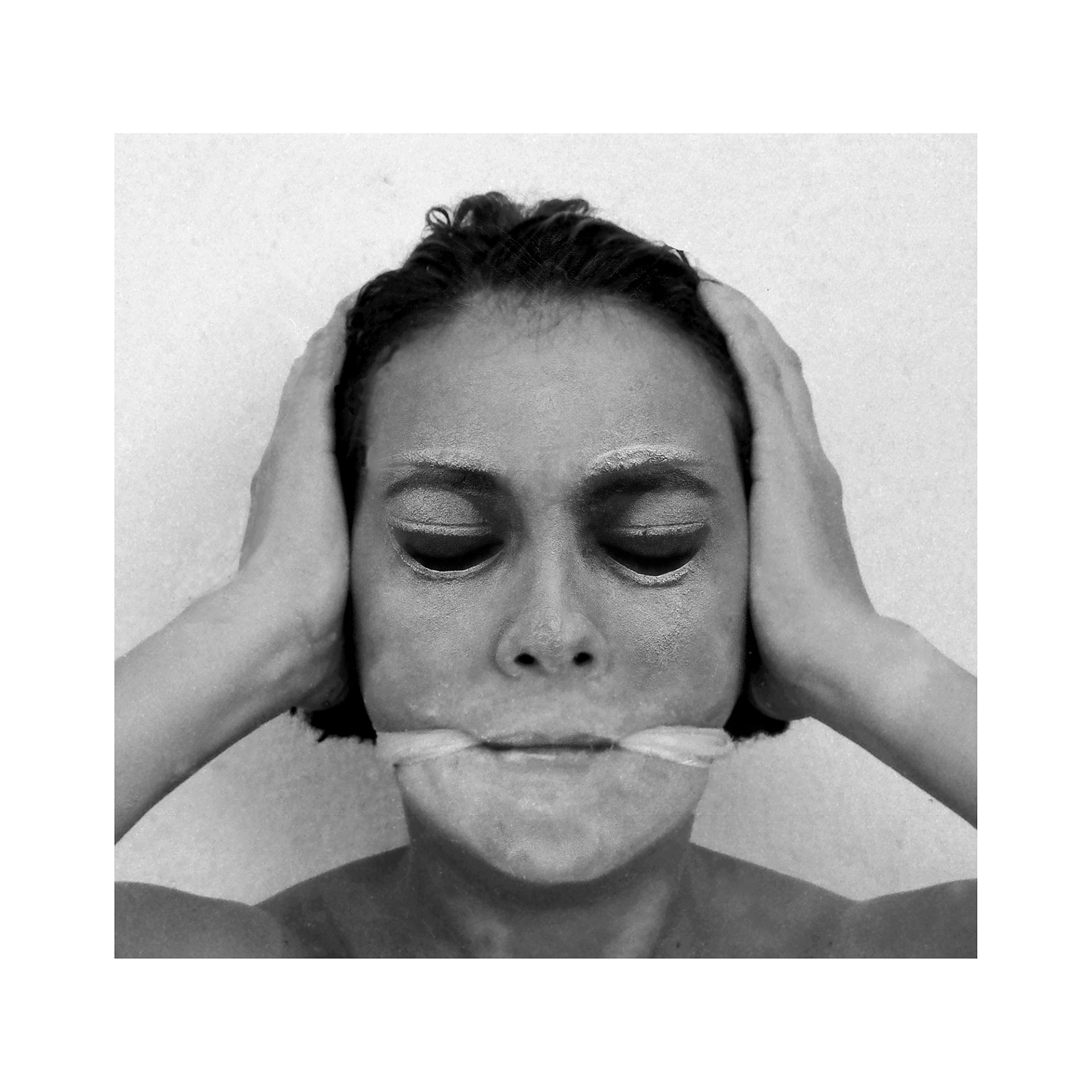

During a lifetime of work, Marta Maria Perez Bravo has explored the rites and beliefs of Cuban religion through her own image. Her body sacrifices the symbol, creating an account of intersections between dualities, such as the visible and the invisible, the material and the spiritual, life after death, the presence of absence. That reiteration of opposites uses its own aesthetic to create narratives that, supported by the photographic document, build a universe of re-creations of rites and ceremonial objects.

Currently, her artistic proposal has led her to use other visual mediums with which she complements and continues to investigate her conceptual interests.

Marta María Pérez Bravo (Cuba, 1959). Lives and works in Mexico. Photographer. She began her studies as an artist in 1979 at the School of Visual Arts San Alejandro, Havana, Cuba. In 1984 she continued her studies at the Instituto Superior de Arte (ISA), Havana, Cuba. She has participated in numerous international solo and group exhibitions. She has won several awards for her work, such as the Guggenheim Fellowship (USA) in 1998.

Marta María Pérez Bravo (Cuba, 1959). Lives and works in Mexico. Photographer. She began her studies as an artist in 1979 at the School of Visual Arts San Alejandro, Havana, Cuba. In 1984 she continued her studies at the Instituto Superior de Arte (ISA), Havana, Cuba. She has participated in numerous international solo and group exhibitions. She has won several awards for her work, such as the Guggenheim Fellowship (USA) in 1998.ZZ. In your work, self-representation is a constant theme, ¿how did your interest in talking about various themes through your own image arise?

MM. I studied Fine Arts, but my graduate thesis, at the Instituto Superior de Arte in Havana (1984), was a photographic project, even though I never studied photography. This project consisted of photographs documenting actions that I performed outdoors, taking as its theme the popular superstitions regarding natural phenomena, appearances etc. When I was pregnant, I could no longer do these performances and I started using my own body. I started to document, in a different way, other actions related to these superstitions and popular beliefs, but now regarding my experience of motherhood. As in the first stage, these realities were constructed and ‘staged’. So, from the beginning, it was clear that using a model or another person, and not my own body would completely change the concept of the work, given that it has a strong autobiographical presence, although implicitly.

ZZ. We see that themes, like evocation and absence, are constant in your work. How have these themes continued to change throughout your career?

MM. In my work, religious themes, especially of afro-cuban origin, started to emerge. The constructed realities (constructed through the staged scenes), that are devoid of time and space, are re-creations (not recreations) of rites and ritual objects.

ZZ. What is the symbolic value of the objects in your photos? What place do you give to the objects as symbols in your photos? What does their reiterative use signify?

From the ritual objects I want to extract a meaning that goes beyond the form, though the making of these objects is done with reference to the originals and the use they are given in religious practices. Although my photography is always black and white, I use the original colors in the elaboration of these objects as a token of respect for these practices and real liturgical objects. Nevertheless, I don’t want the spectator to be distracted by these colors; I want him to focus his attention on the symbols and their meanings. Even though he might not know them at all (since they are object of separate study and profound analysis) my intention is that, when these symbols are interpreted, they evoke ideas and suggest and provoke sensations. In addition to this, the title is a fundamental part of each piece.

ZZ. How does photography help you in the search of your identity? And, what has the use of video added to your work?

Since the beginning of my work in the eighties, my work has been photographic, although five or six years ago it went through a formal change –not its concept nor its aesthetic– through the use of video. The only aspects that make these videos different from my photographic work is the existence of space and the time in which an action occurs. Besides that, my work has not changed; in representing my ideas, I maintain the minimalistic aesthetic, I use the same materials and concepts, I still use black and white and I don’t use audio.

I don’t exactly know in which moment I started using video, but I think it happened in a very natural way, or, in other words, the development of the work itself brought me to it. Actually, people had asked me why I didn’t make videos, because of the performative character of my work, but at the time I, as an artist, was not at all interested in the idea, even though later on I permanently incorporated this medium into my work.

ZZ. What has been the result of your search throughout these years and which course is it taking?

Currently I tend to use video as a medium and not photography, but I still maintain my own aesthetic and conceptual parameters. The only difference is that, at the moment, video is a perfect medium for what I want. Surely the development of my work will lead me to other formal solutions in the future.

I have always thought that maybe a lot of the success of an artist’s work depends on finding the right tool with which he can express and “realize” his ideas.

During a lifetime of work, Marta Maria Perez Bravo has explored the rites and beliefs of Cuban religion through her own image. Her body sacrifices the symbol, creating an account of intersections between dualities, such as the visible and the invisible, the material and the spiritual, life after death, the presence of absence. That reiteration of opposites uses its own aesthetic to create narratives that, supported by the photographic document, build a universe of re-creations of rites and ceremonial objects.

Currently, her artistic proposal has led her to use other visual mediums with which she complements and continues to investigate her conceptual interests.

Marta María Pérez Bravo (Cuba, 1959). Lives and works in Mexico. Photographer. She began her studies as an artist in 1979 at the School of Visual Arts San Alejandro, Havana, Cuba. In 1984 she continued her studies at the Instituto Superior de Arte (ISA), Havana, Cuba. She has participated in numerous international solo and group exhibitions. She has won several awards for her work, such as the Guggenheim Fellowship (USA) in 1998.

Marta María Pérez Bravo (Cuba, 1959). Lives and works in Mexico. Photographer. She began her studies as an artist in 1979 at the School of Visual Arts San Alejandro, Havana, Cuba. In 1984 she continued her studies at the Instituto Superior de Arte (ISA), Havana, Cuba. She has participated in numerous international solo and group exhibitions. She has won several awards for her work, such as the Guggenheim Fellowship (USA) in 1998.ZZ. In your work, self-representation is a constant theme, ¿how did your interest in talking about various themes through your own image arise?

MM. I studied Fine Arts, but my graduate thesis, at the Instituto Superior de Arte in Havana (1984), was a photographic project, even though I never studied photography. This project consisted of photographs documenting actions that I performed outdoors, taking as its theme the popular superstitions regarding natural phenomena, appearances etc. When I was pregnant, I could no longer do these performances and I started using my own body. I started to document, in a different way, other actions related to these superstitions and popular beliefs, but now regarding my experience of motherhood. As in the first stage, these realities were constructed and ‘staged’. So, from the beginning, it was clear that using a model or another person, and not my own body would completely change the concept of the work, given that it has a strong autobiographical presence, although implicitly.

ZZ. We see that themes, like evocation and absence, are constant in your work. How have these themes continued to change throughout your career?

MM. In my work, religious themes, especially of afro-cuban origin, started to emerge. The constructed realities (constructed through the staged scenes), that are devoid of time and space, are re-creations (not recreations) of rites and ritual objects.

ZZ. What is the symbolic value of the objects in your photos? What place do you give to the objects as symbols in your photos? What does their reiterative use signify?

From the ritual objects I want to extract a meaning that goes beyond the form, though the making of these objects is done with reference to the originals and the use they are given in religious practices. Although my photography is always black and white, I use the original colors in the elaboration of these objects as a token of respect for these practices and real liturgical objects. Nevertheless, I don’t want the spectator to be distracted by these colors; I want him to focus his attention on the symbols and their meanings. Even though he might not know them at all (since they are object of separate study and profound analysis) my intention is that, when these symbols are interpreted, they evoke ideas and suggest and provoke sensations. In addition to this, the title is a fundamental part of each piece.

ZZ. How does photography help you in the search of your identity? And, what has the use of video added to your work?

Since the beginning of my work in the eighties, my work has been photographic, although five or six years ago it went through a formal change –not its concept nor its aesthetic– through the use of video. The only aspects that make these videos different from my photographic work is the existence of space and the time in which an action occurs. Besides that, my work has not changed; in representing my ideas, I maintain the minimalistic aesthetic, I use the same materials and concepts, I still use black and white and I don’t use audio.

I don’t exactly know in which moment I started using video, but I think it happened in a very natural way, or, in other words, the development of the work itself brought me to it. Actually, people had asked me why I didn’t make videos, because of the performative character of my work, but at the time I, as an artist, was not at all interested in the idea, even though later on I permanently incorporated this medium into my work.

ZZ. What has been the result of your search throughout these years and which course is it taking?

Currently I tend to use video as a medium and not photography, but I still maintain my own aesthetic and conceptual parameters. The only difference is that, at the moment, video is a perfect medium for what I want. Surely the development of my work will lead me to other formal solutions in the future.

I have always thought that maybe a lot of the success of an artist’s work depends on finding the right tool with which he can express and “realize” his ideas.

Matthew Hashiguchi

Good Luck Soup

Good Luck SoupIs a transmedia storytelling project documenting and sharing stories of the Japanese American and Japanese Canadian experience after they left the internment camps. The project consists of a feature-length documentary film, titled Good Luck Soup and an interactive, participatory website, Good Luck Soup Interactive. On this website stories will be told through uploaded text and photographs from internment camp victims, or their families, and will be shared through an interactive website and map.

People Aren't All Bad

People Aren't All BadZZ. What has been the reaction of the public to your invitation to participate in your transmedia storytelling project?

MH. We've had a consistently positive response from the Japanese American/Canadian community. Initially, I think many have been nervous about sharing their own stories and experiences, but once we sit down with them and talk about their life, they tend to open up. It's been a form of catharsis, I think, because many people have never discussed their issues or experiences of being Japanese American/Canadian... and some of these things are very difficult topics or thoughts that have been bottled up. So, it's a very emotional experience to share these thoughts and feelings. We haven't yet opened it up to the general public, but again, everyone has been consistently positive, and I have no reason to think the reaction will be any different once its available to all Japanese Americans and Japanese Canadians.

ZZ. What means of publicity are you using or are you planning to use for the diffusion of the project?

MH. Social media will be a huge tool for publicity and marketing. We've already reached and met so many people through Twitter and Facebook, and we'll certainly continue to utilize those outlets. We've been in communication with many Asian American and Asian Canadian organizations that have offered their support once the project is complete, and the opportunity to collaborate with entities such as the Japanese American Citizens League, the Japanese American National Museum and the Nikkei National Museum would be priceless. We're certainly inspired by their mission and view our project as a continuation of what they offer the public.

In addition to the interactive documentary, this project also includes a feature length film. Film festivals will be another great opportunity to screen the film and present the interactive project to an audience.

ZZ. Can you share with us how you have experienced the realisation, dissemination and the reach of the project thus far?

MH. It's been a very gradual and collaborative process, and luckily I have an incredible team of colleagues and friends that have made the realization of this project possible, and without their help, I would not have been able to get this project made. The work load is split up fairly well. Right now, our web-designer/coder (Russell Goldenberg) is building the site. He's the one sitting alone typing away at his computer. Every few weeks, we'll all have a meeting where we discuss the direction of the project... and then Russell goes and brings it to life. Billy Wirasnik, Emily Ferrier and myself and have been in charge of content aggregation. So we're narrowing the aim of the stories and in many cases, going out and finding those stories and individuals. It's a solid collaboration made up of various creative visions, rather than one. And, as the Project Creator, I really enjoy a hands-off approach that allows individuals to run off with an idea and make it their own.

Matthew Hashiguchi (1984). Based in Boston, Massachusetts. After graduating from The Ohio State University in 2007 with a BA in Photojournalism, Matthew went on to work and intern as a multimedia journalist for The Findlay Courier, The Lima News and The Washington Post. In 2008, he returned to school and graduated from Emerson College with an MFA in Visual and Media Art and has since been working as an independent documentary filmmaker and educator, whose work focuses on the diverse cultural, social and ethnic stories of American society. For his film The Lower 9 he has received various awards.

Matthew Hashiguchi (1984). Based in Boston, Massachusetts. After graduating from The Ohio State University in 2007 with a BA in Photojournalism, Matthew went on to work and intern as a multimedia journalist for The Findlay Courier, The Lima News and The Washington Post. In 2008, he returned to school and graduated from Emerson College with an MFA in Visual and Media Art and has since been working as an independent documentary filmmaker and educator, whose work focuses on the diverse cultural, social and ethnic stories of American society. For his film The Lower 9 he has received various awards. Good Luck Soup

Good Luck SoupIs a transmedia storytelling project documenting and sharing stories of the Japanese American and Japanese Canadian experience after they left the internment camps. The project consists of a feature-length documentary film, titled Good Luck Soup and an interactive, participatory website, Good Luck Soup Interactive. On this website stories will be told through uploaded text and photographs from internment camp victims, or their families, and will be shared through an interactive website and map.

People Aren't All Bad

People Aren't All BadZZ. What has been the reaction of the public to your invitation to participate in your transmedia storytelling project?

MH. We've had a consistently positive response from the Japanese American/Canadian community. Initially, I think many have been nervous about sharing their own stories and experiences, but once we sit down with them and talk about their life, they tend to open up. It's been a form of catharsis, I think, because many people have never discussed their issues or experiences of being Japanese American/Canadian... and some of these things are very difficult topics or thoughts that have been bottled up. So, it's a very emotional experience to share these thoughts and feelings. We haven't yet opened it up to the general public, but again, everyone has been consistently positive, and I have no reason to think the reaction will be any different once its available to all Japanese Americans and Japanese Canadians.

ZZ. What means of publicity are you using or are you planning to use for the diffusion of the project?

MH. Social media will be a huge tool for publicity and marketing. We've already reached and met so many people through Twitter and Facebook, and we'll certainly continue to utilize those outlets. We've been in communication with many Asian American and Asian Canadian organizations that have offered their support once the project is complete, and the opportunity to collaborate with entities such as the Japanese American Citizens League, the Japanese American National Museum and the Nikkei National Museum would be priceless. We're certainly inspired by their mission and view our project as a continuation of what they offer the public.

In addition to the interactive documentary, this project also includes a feature length film. Film festivals will be another great opportunity to screen the film and present the interactive project to an audience.

ZZ. Can you share with us how you have experienced the realisation, dissemination and the reach of the project thus far?

MH. It's been a very gradual and collaborative process, and luckily I have an incredible team of colleagues and friends that have made the realization of this project possible, and without their help, I would not have been able to get this project made. The work load is split up fairly well. Right now, our web-designer/coder (Russell Goldenberg) is building the site. He's the one sitting alone typing away at his computer. Every few weeks, we'll all have a meeting where we discuss the direction of the project... and then Russell goes and brings it to life. Billy Wirasnik, Emily Ferrier and myself and have been in charge of content aggregation. So we're narrowing the aim of the stories and in many cases, going out and finding those stories and individuals. It's a solid collaboration made up of various creative visions, rather than one. And, as the Project Creator, I really enjoy a hands-off approach that allows individuals to run off with an idea and make it their own.

Matthew Hashiguchi (1984). Based in Boston, Massachusetts. After graduating from The Ohio State University in 2007 with a BA in Photojournalism, Matthew went on to work and intern as a multimedia journalist for The Findlay Courier, The Lima News and The Washington Post. In 2008, he returned to school and graduated from Emerson College with an MFA in Visual and Media Art and has since been working as an independent documentary filmmaker and educator, whose work focuses on the diverse cultural, social and ethnic stories of American society. For his film The Lower 9 he has received various awards.

Matthew Hashiguchi (1984). Based in Boston, Massachusetts. After graduating from The Ohio State University in 2007 with a BA in Photojournalism, Matthew went on to work and intern as a multimedia journalist for The Findlay Courier, The Lima News and The Washington Post. In 2008, he returned to school and graduated from Emerson College with an MFA in Visual and Media Art and has since been working as an independent documentary filmmaker and educator, whose work focuses on the diverse cultural, social and ethnic stories of American society. For his film The Lower 9 he has received various awards.Trish Morrissey