Elisa Calore

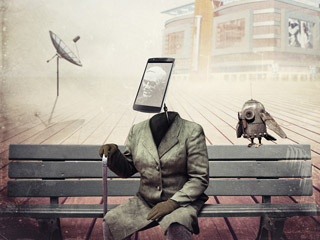

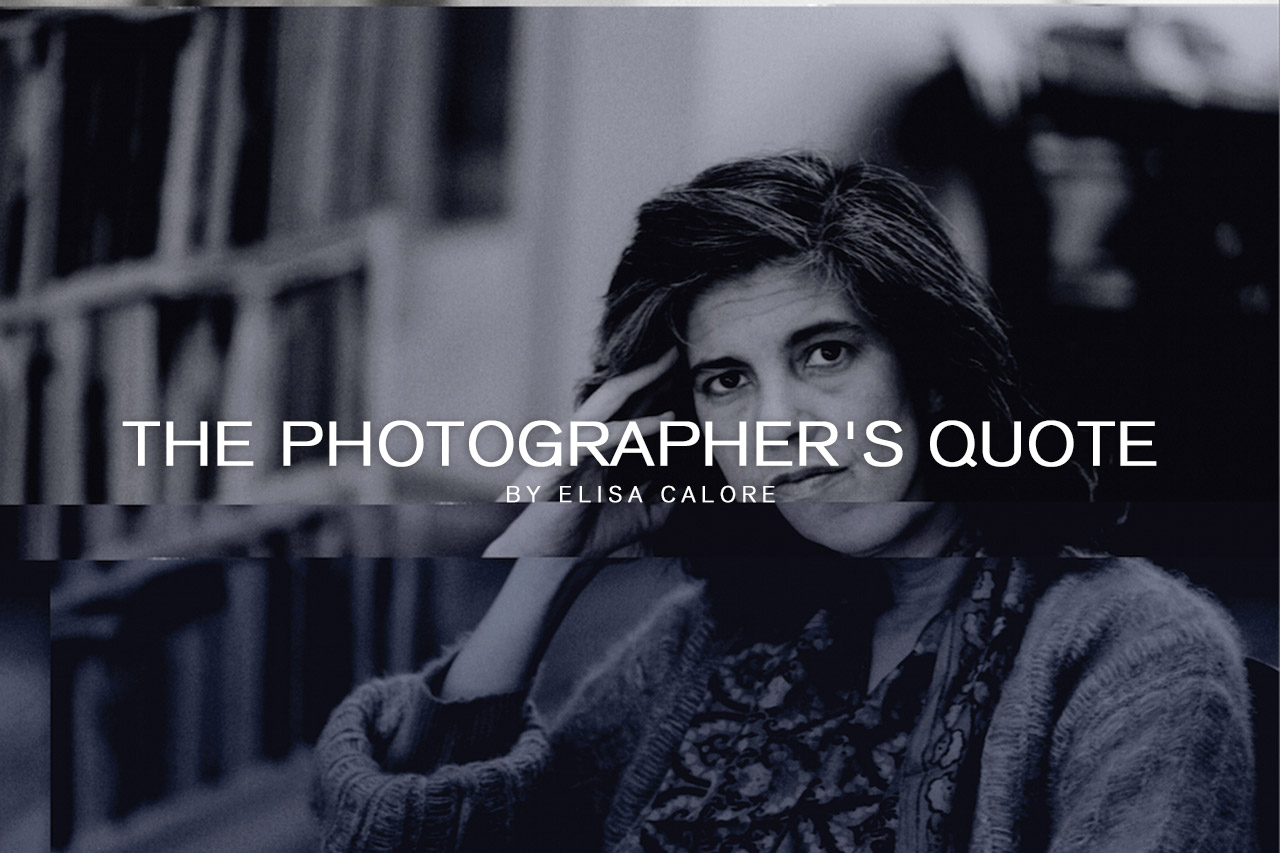

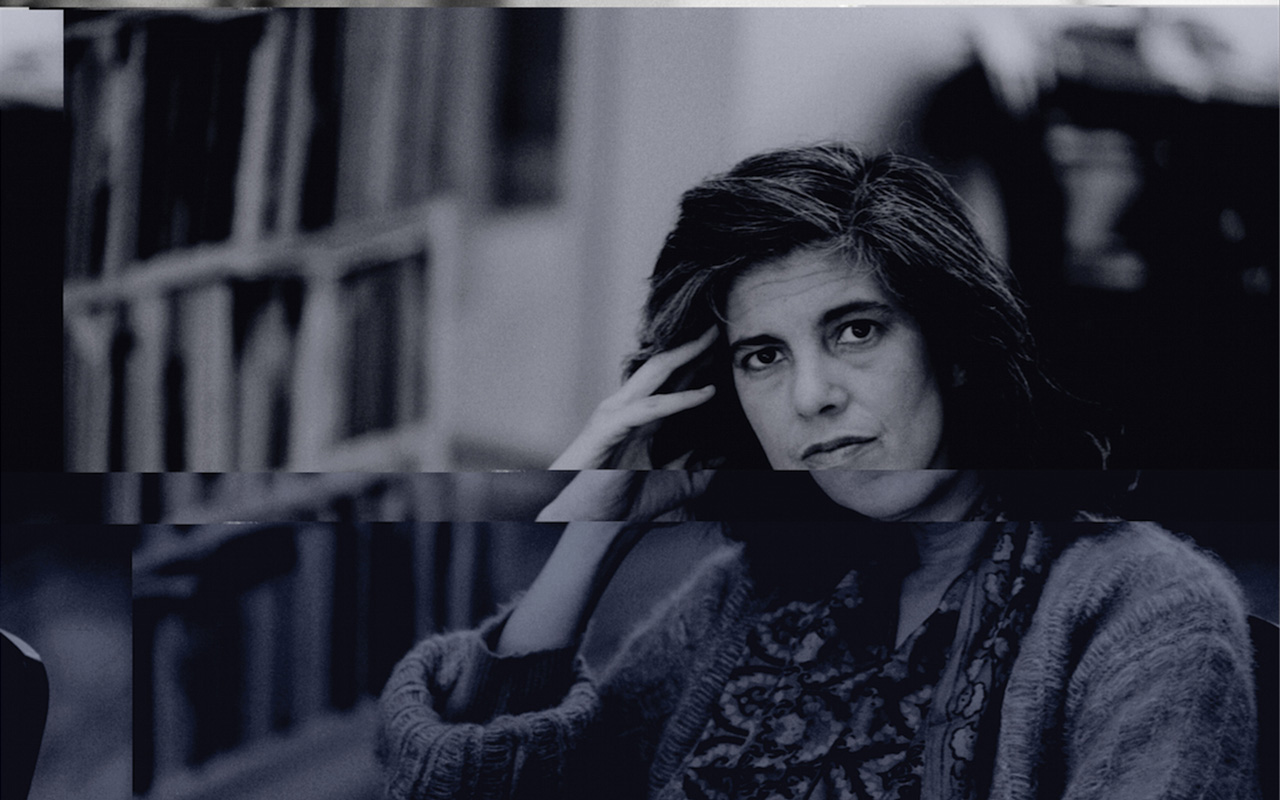

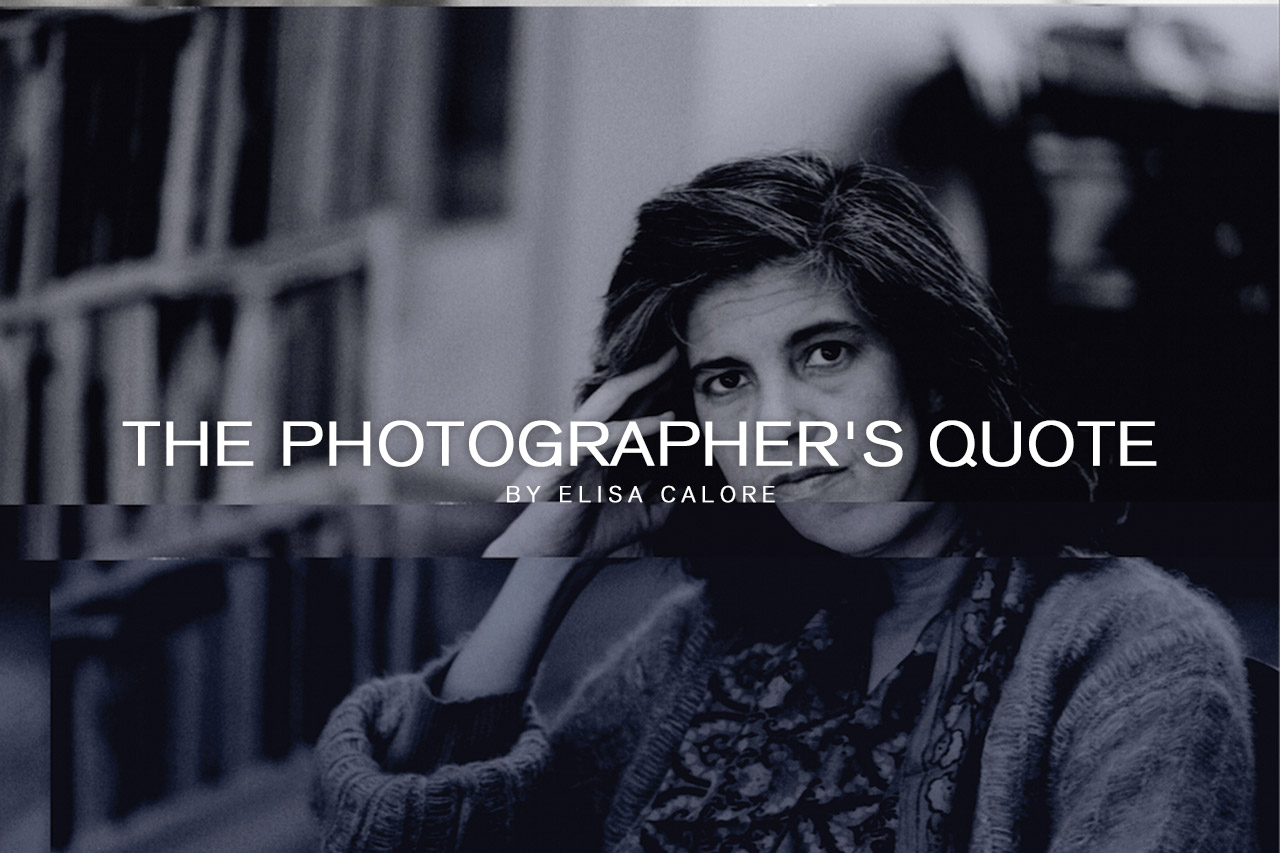

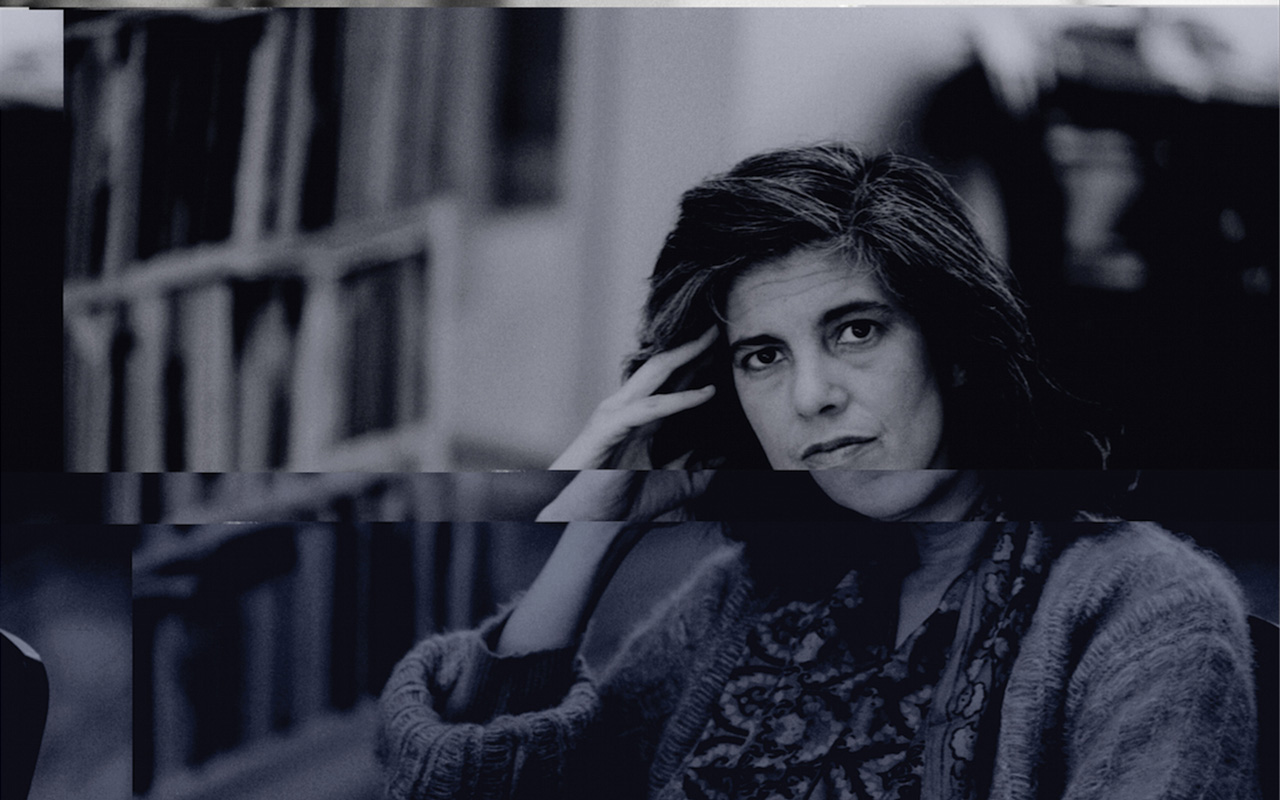

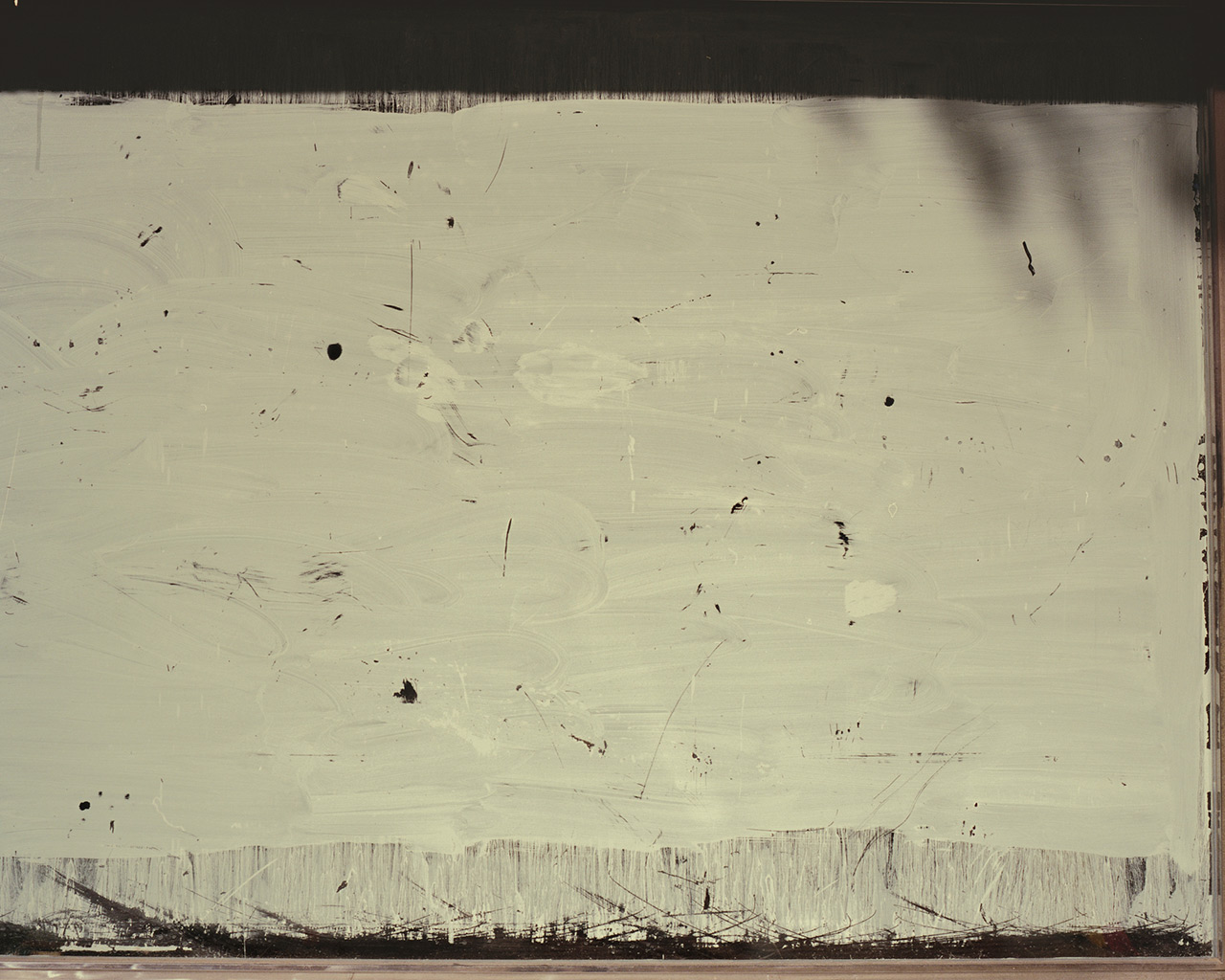

Does a portrait tell something about the person photographed? Does text help us to read a photograph more clearly?

"To quote out of context is the essence of the photographer's craft” said John Szarkowski in his The Photographer's Eye.

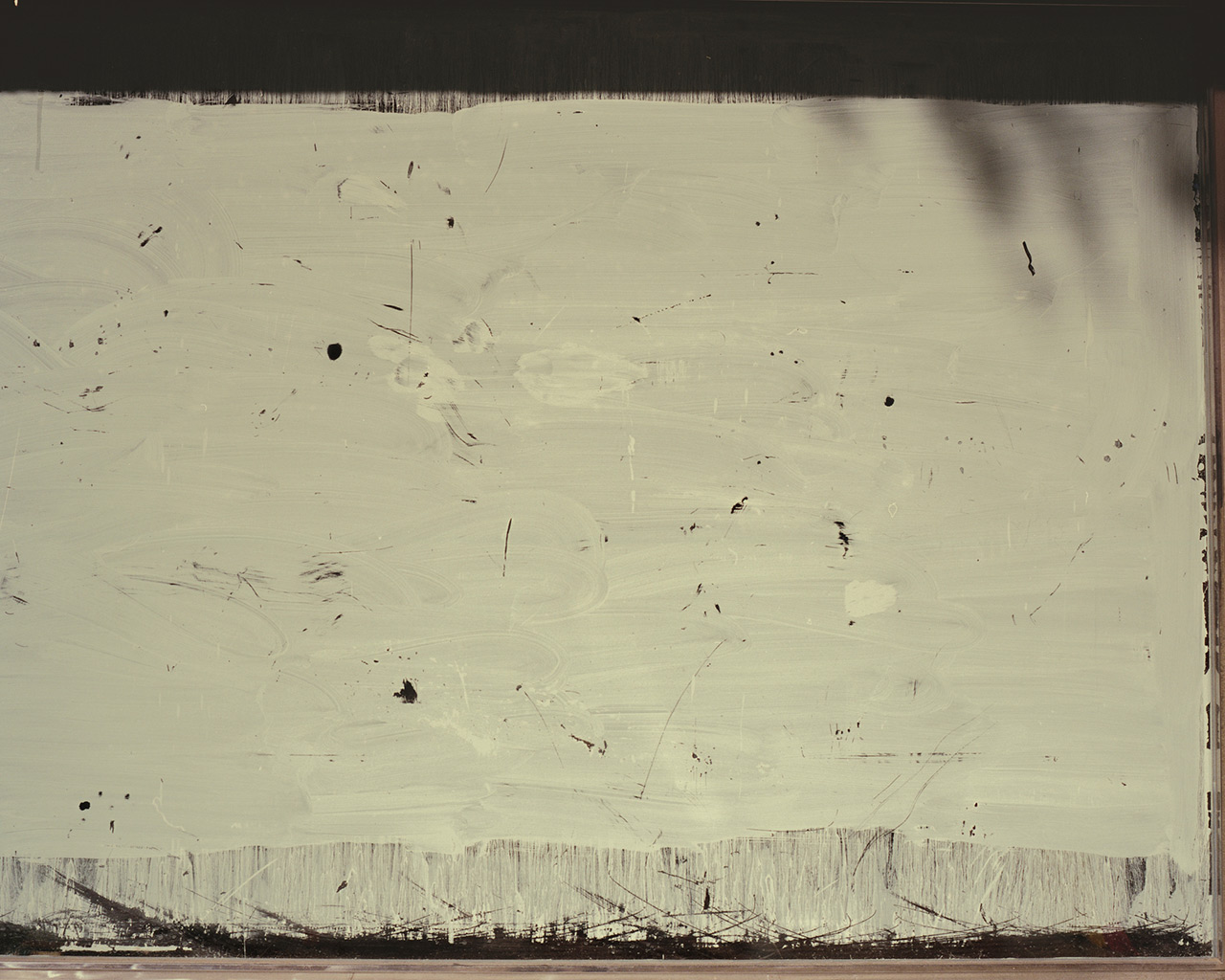

I downloaded portraits of famous photographers and opened them with the program TextEdit. Then I added some of the thoughts of these photographers to the code of their portraits, causing a “literary glitch” that helps us look cautiously at the medium and its relationship with words. The process of elaborating the photos is not coincidental, but a procedure carried out in accordance with the knowledge of the medium, despite the random results.

William Eggleston:

A picture is what it is and I’ve never noticed that it helps to talk about them, or answer specific questions about them, much less volunteer information in words. It wouldn’t make any sense to explain them. Kind of diminishes them. People always want to know when something was taken, where it was taken, and, God knows, why it was taken. It gets really ridiculous. I mean, they’re right there, whatever they are.

Walker Evans:

The photographs are not illustrative. They, and the text, are coequal, mutually independent, and fully collaborative.

Annie Leibovitz:

In a portrait, you have room to have a point of view. The image may not be literally what's going on, but it's representative.

Susan Sontag:

To take a photograph is to participate in another person's mortality, vulnerability, mutability. Precisely by slicing out this moment and freezing it, all photographs testify to time's relentless melt.

Thomas Struth:

For me, making a photograph is mostly an intellectual process of understanding people or cities and their historical and phenomenological connections. At that point the photo is almost made, and all that remains is the mechanical process.

Elisa Calore (Italy, 1982). Designer and researcher in the field of visual and multimedia communication. Her practice has mainly been focused around different aspects of the image: its construction and its use to give it meaning, the social context, the place in which it is positioned, its qualities, its economic value, the cultural negotiation between creators and viewers. Passionate about all matter related to photography, she is the general coordinator of the first edition of PRISMA – Human Rights Photo Contest.

Elisa Calore (Italy, 1982). Designer and researcher in the field of visual and multimedia communication. Her practice has mainly been focused around different aspects of the image: its construction and its use to give it meaning, the social context, the place in which it is positioned, its qualities, its economic value, the cultural negotiation between creators and viewers. Passionate about all matter related to photography, she is the general coordinator of the first edition of PRISMA – Human Rights Photo Contest.

Does a portrait tell something about the person photographed? Does text help us to read a photograph more clearly?

"To quote out of context is the essence of the photographer's craft” said John Szarkowski in his The Photographer's Eye.

I downloaded portraits of famous photographers and opened them with the program TextEdit. Then I added some of the thoughts of these photographers to the code of their portraits, causing a “literary glitch” that helps us look cautiously at the medium and its relationship with words. The process of elaborating the photos is not coincidental, but a procedure carried out in accordance with the knowledge of the medium, despite the random results.

William Eggleston:

A picture is what it is and I’ve never noticed that it helps to talk about them, or answer specific questions about them, much less volunteer information in words. It wouldn’t make any sense to explain them. Kind of diminishes them. People always want to know when something was taken, where it was taken, and, God knows, why it was taken. It gets really ridiculous. I mean, they’re right there, whatever they are.

Walker Evans:

The photographs are not illustrative. They, and the text, are coequal, mutually independent, and fully collaborative.

Annie Leibovitz:

In a portrait, you have room to have a point of view. The image may not be literally what's going on, but it's representative.

Susan Sontag:

To take a photograph is to participate in another person's mortality, vulnerability, mutability. Precisely by slicing out this moment and freezing it, all photographs testify to time's relentless melt.

Thomas Struth:

For me, making a photograph is mostly an intellectual process of understanding people or cities and their historical and phenomenological connections. At that point the photo is almost made, and all that remains is the mechanical process.

Elisa Calore (Italy, 1982). Designer and researcher in the field of visual and multimedia communication. Her practice has mainly been focused around different aspects of the image: its construction and its use to give it meaning, the social context, the place in which it is positioned, its qualities, its economic value, the cultural negotiation between creators and viewers. Passionate about all matter related to photography, she is the general coordinator of the first edition of PRISMA – Human Rights Photo Contest.

Elisa Calore (Italy, 1982). Designer and researcher in the field of visual and multimedia communication. Her practice has mainly been focused around different aspects of the image: its construction and its use to give it meaning, the social context, the place in which it is positioned, its qualities, its economic value, the cultural negotiation between creators and viewers. Passionate about all matter related to photography, she is the general coordinator of the first edition of PRISMA – Human Rights Photo Contest.Francesco Romoli

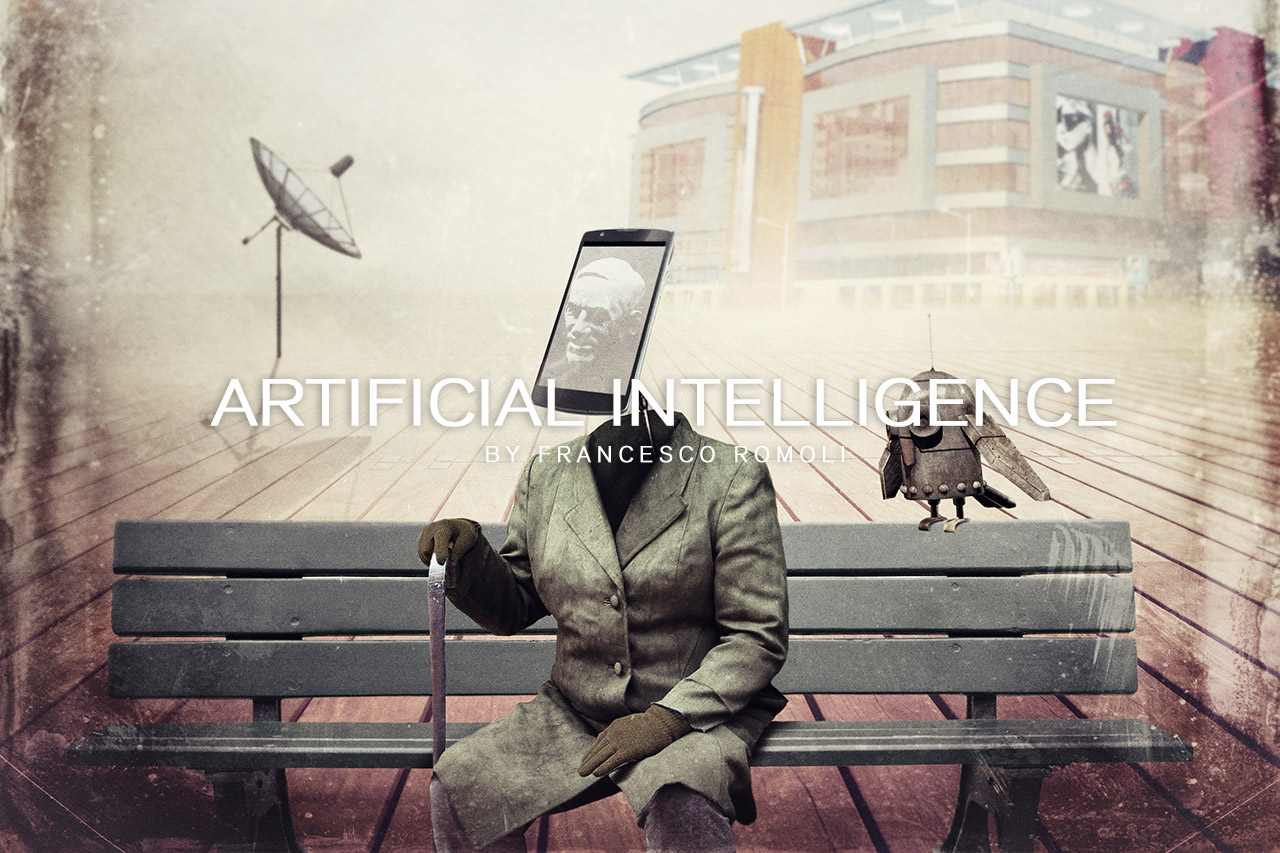

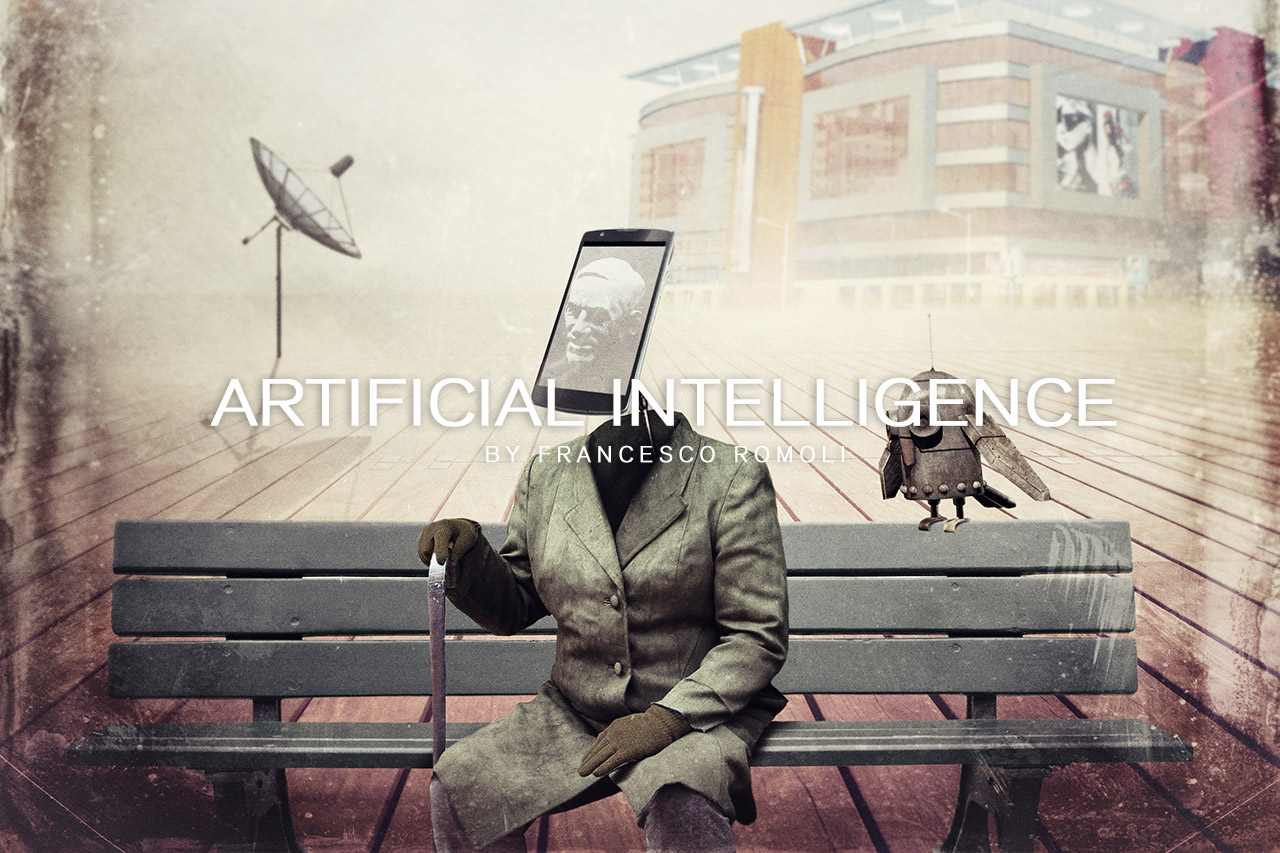

After a period of decline comes the turning point.

The intense light that had been driven away returns.

There is movement, but not caused by violence... The movement is natural, developing spontaneously.

Thus, transformation of the old becomes easy.

The old is discarded and replaced with the new.

Both actions are in keeping with the time; thereby causing no damage.

Francesco Romoli (Pisa, Italy 1977). Always interested in expressive forms of any type at age 14 he began to study guitar and music theory. He falls in love in computers in 1998 and started to work on hacking and net-art. He graduated in 2004 in Pisa in computer science. In 2010 begins to use photoshop for his creations, halfway between graphic design and photography. In 2012 he began studying at the center of contemporary photography Fondazione Studio Marangoni, Florence. His other passions include skydiving and travel.

Francesco Romoli (Pisa, Italy 1977). Always interested in expressive forms of any type at age 14 he began to study guitar and music theory. He falls in love in computers in 1998 and started to work on hacking and net-art. He graduated in 2004 in Pisa in computer science. In 2010 begins to use photoshop for his creations, halfway between graphic design and photography. In 2012 he began studying at the center of contemporary photography Fondazione Studio Marangoni, Florence. His other passions include skydiving and travel.

After a period of decline comes the turning point.

The intense light that had been driven away returns.

There is movement, but not caused by violence... The movement is natural, developing spontaneously.

Thus, transformation of the old becomes easy.

The old is discarded and replaced with the new.

Both actions are in keeping with the time; thereby causing no damage.

Francesco Romoli (Pisa, Italy 1977). Always interested in expressive forms of any type at age 14 he began to study guitar and music theory. He falls in love in computers in 1998 and started to work on hacking and net-art. He graduated in 2004 in Pisa in computer science. In 2010 begins to use photoshop for his creations, halfway between graphic design and photography. In 2012 he began studying at the center of contemporary photography Fondazione Studio Marangoni, Florence. His other passions include skydiving and travel.

Francesco Romoli (Pisa, Italy 1977). Always interested in expressive forms of any type at age 14 he began to study guitar and music theory. He falls in love in computers in 1998 and started to work on hacking and net-art. He graduated in 2004 in Pisa in computer science. In 2010 begins to use photoshop for his creations, halfway between graphic design and photography. In 2012 he began studying at the center of contemporary photography Fondazione Studio Marangoni, Florence. His other passions include skydiving and travel.Andrea Dorliguzzo

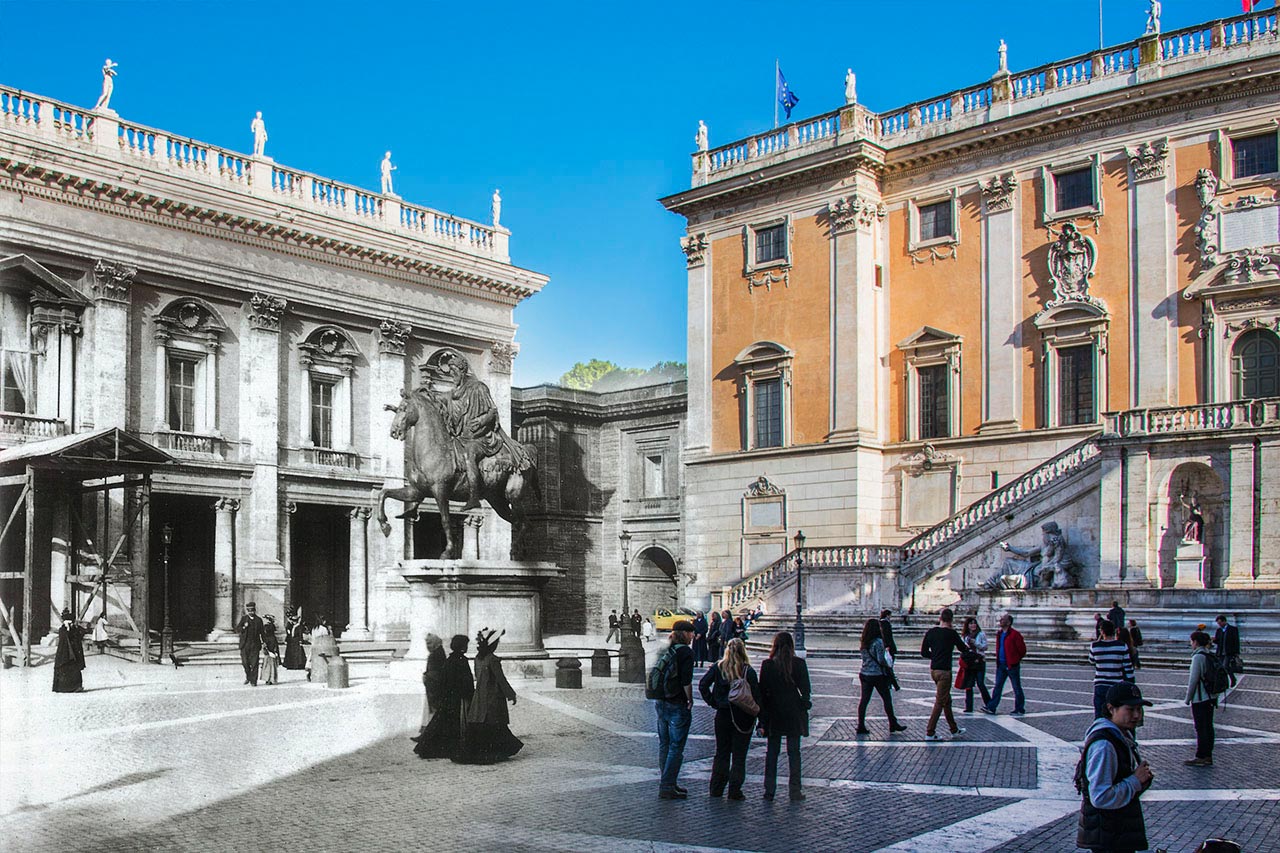

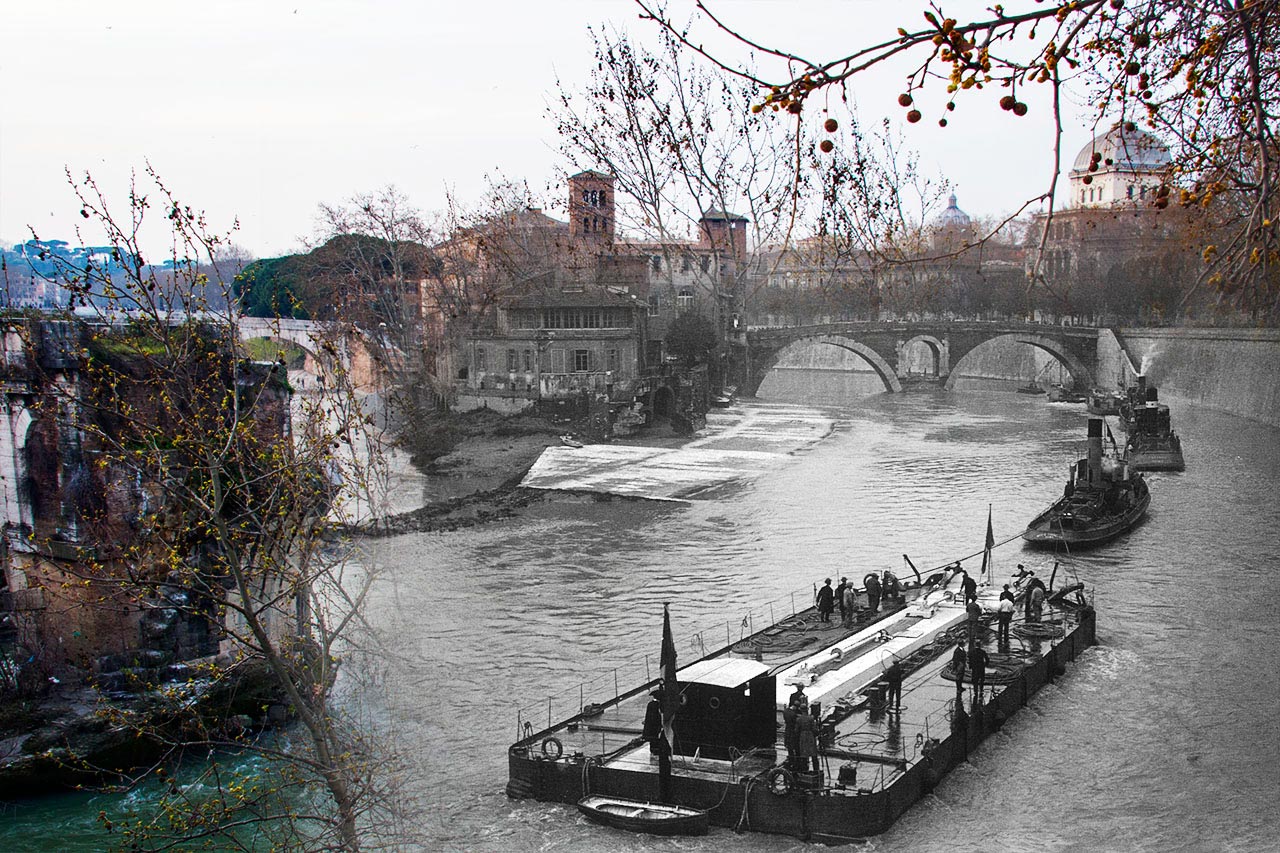

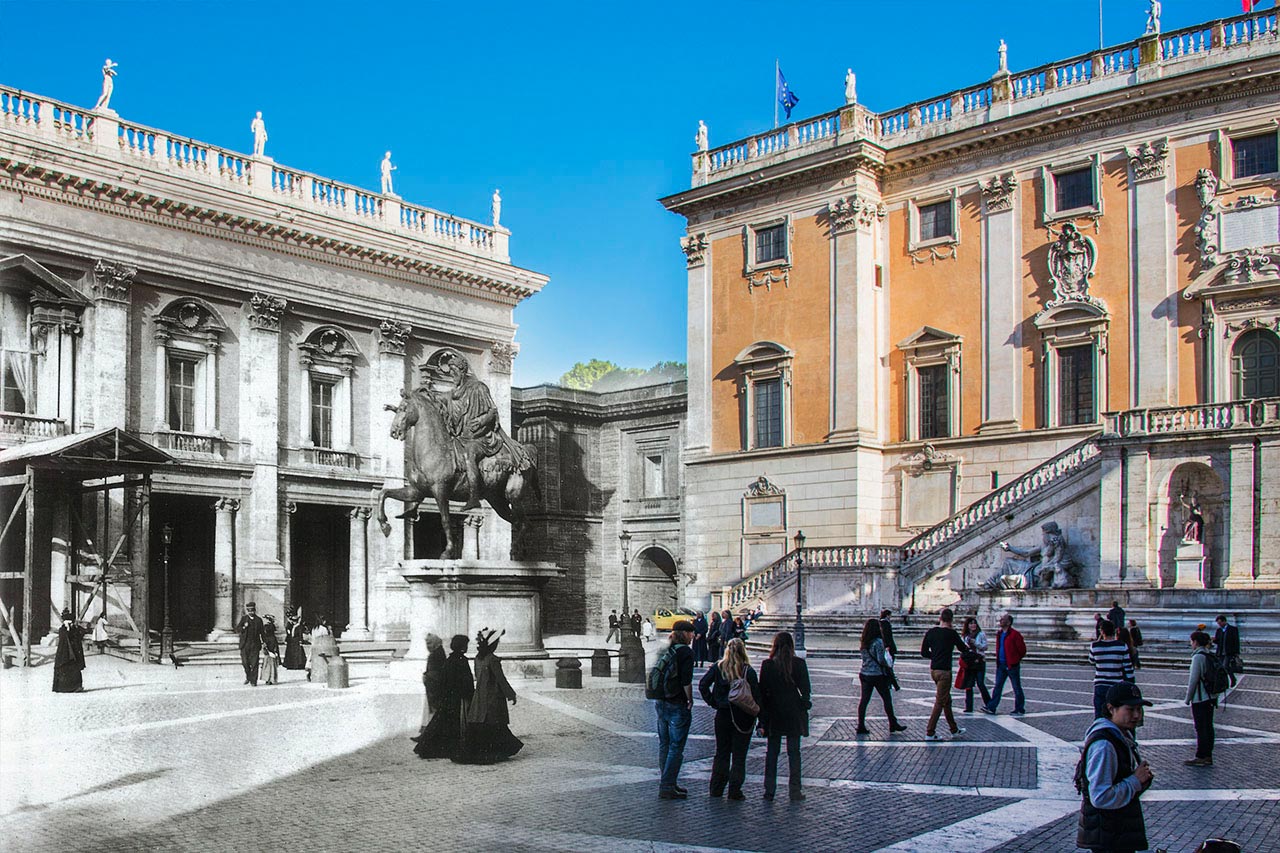

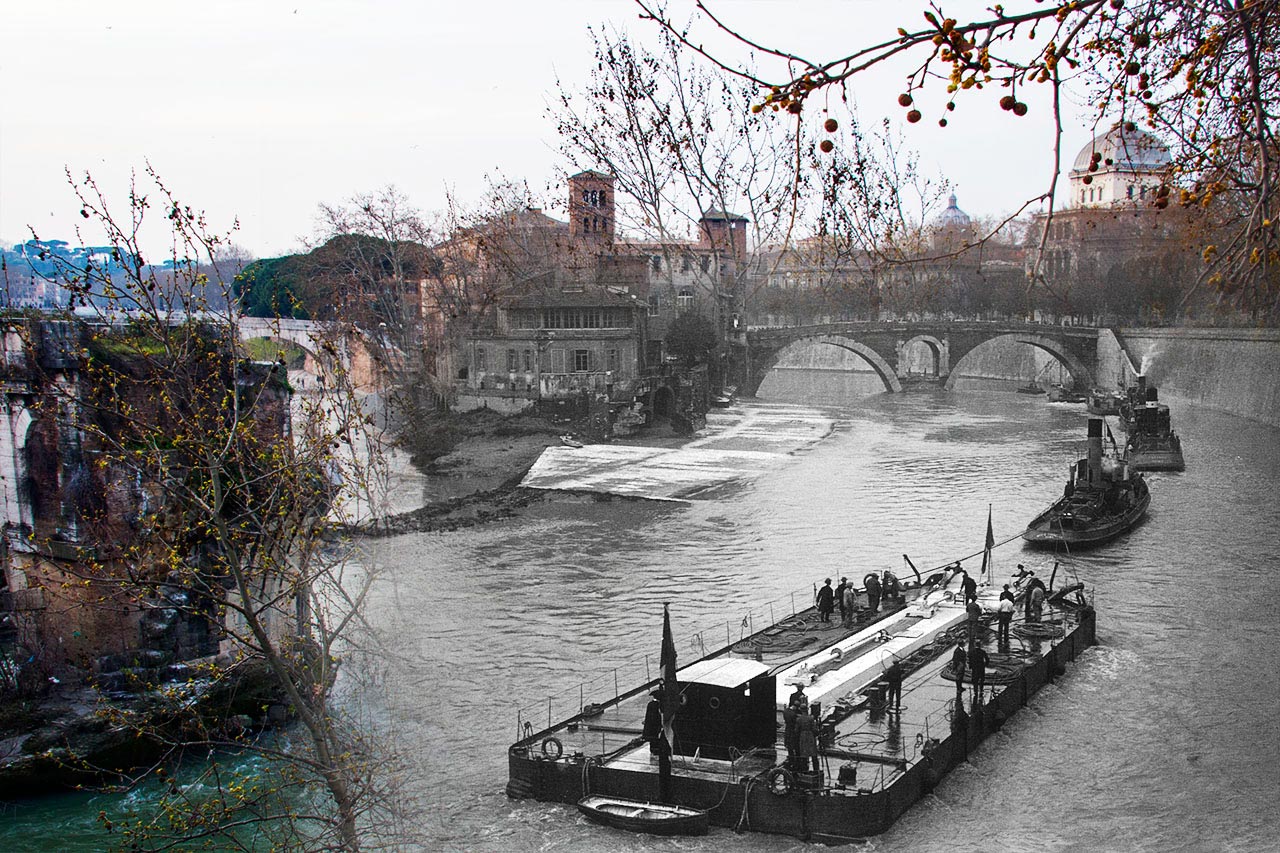

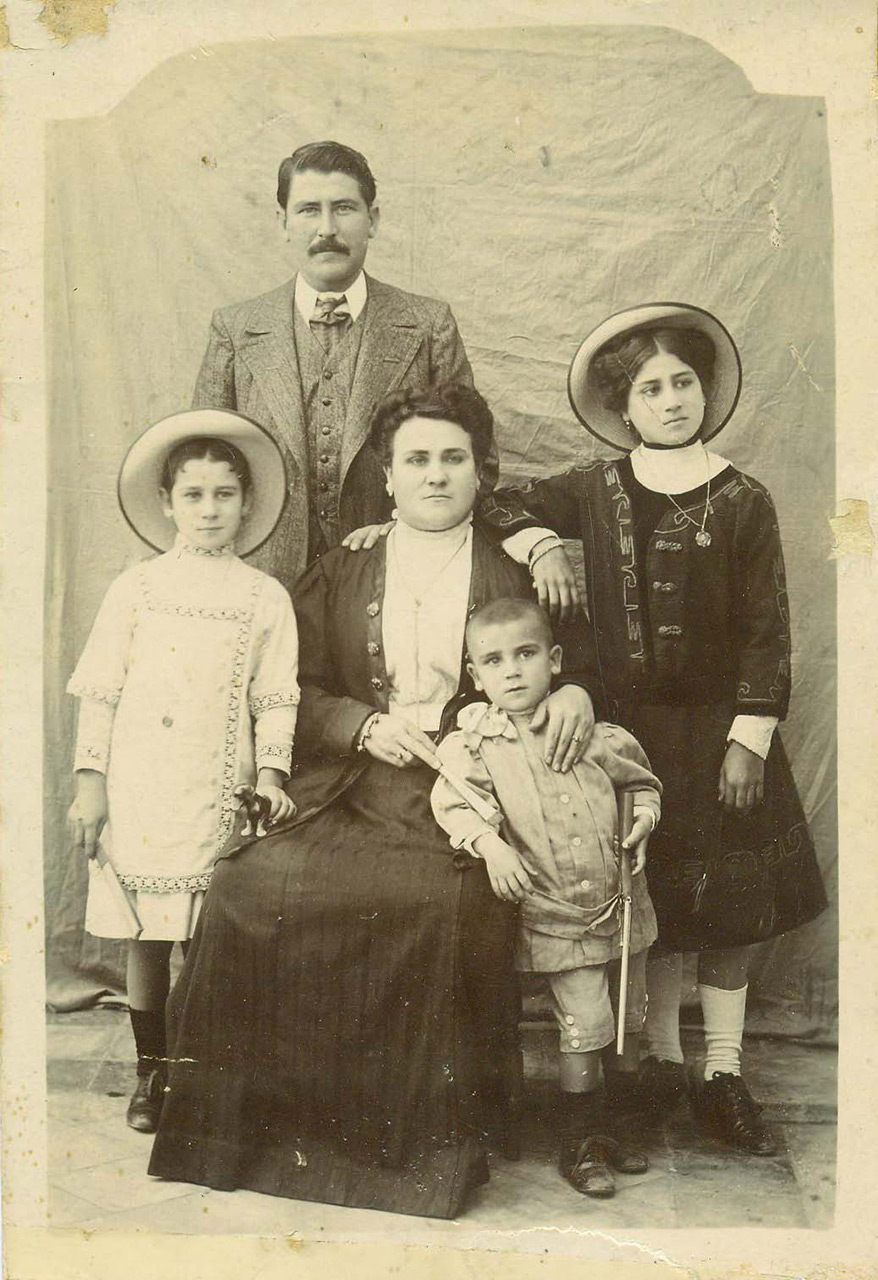

In 2013, Andrea Dorliguzzo started with his rephotography project Roma Ieri Oggi (Rome Yesterday Today). Driven by his passion for photography and his admiration for Rome, he started to collect old photographs of the city and combined these with contemporary ones, taken at exactly the same spot. In this way, the past and the present are brought together, causing a thrilling historical sensation which reminds us of all the great stories that the city has to tell.

Andrea Dorliguzzo (Italy) was born in Friuli, in the north-east part of Italy. A few years ago, he moved to Rome. His passion for photography was born quite recently. Over the last years, he had the luck of traveling a lot and bringing home an unimaginable number of pictures and memories. Regarding his photos, he is very critical and only a small selection is published on his photo blog.

Andrea Dorliguzzo (Italy) was born in Friuli, in the north-east part of Italy. A few years ago, he moved to Rome. His passion for photography was born quite recently. Over the last years, he had the luck of traveling a lot and bringing home an unimaginable number of pictures and memories. Regarding his photos, he is very critical and only a small selection is published on his photo blog.

In 2013, Andrea Dorliguzzo started with his rephotography project Roma Ieri Oggi (Rome Yesterday Today). Driven by his passion for photography and his admiration for Rome, he started to collect old photographs of the city and combined these with contemporary ones, taken at exactly the same spot. In this way, the past and the present are brought together, causing a thrilling historical sensation which reminds us of all the great stories that the city has to tell.

Andrea Dorliguzzo (Italy) was born in Friuli, in the north-east part of Italy. A few years ago, he moved to Rome. His passion for photography was born quite recently. Over the last years, he had the luck of traveling a lot and bringing home an unimaginable number of pictures and memories. Regarding his photos, he is very critical and only a small selection is published on his photo blog.

Andrea Dorliguzzo (Italy) was born in Friuli, in the north-east part of Italy. A few years ago, he moved to Rome. His passion for photography was born quite recently. Over the last years, he had the luck of traveling a lot and bringing home an unimaginable number of pictures and memories. Regarding his photos, he is very critical and only a small selection is published on his photo blog.Alvaro Deprit

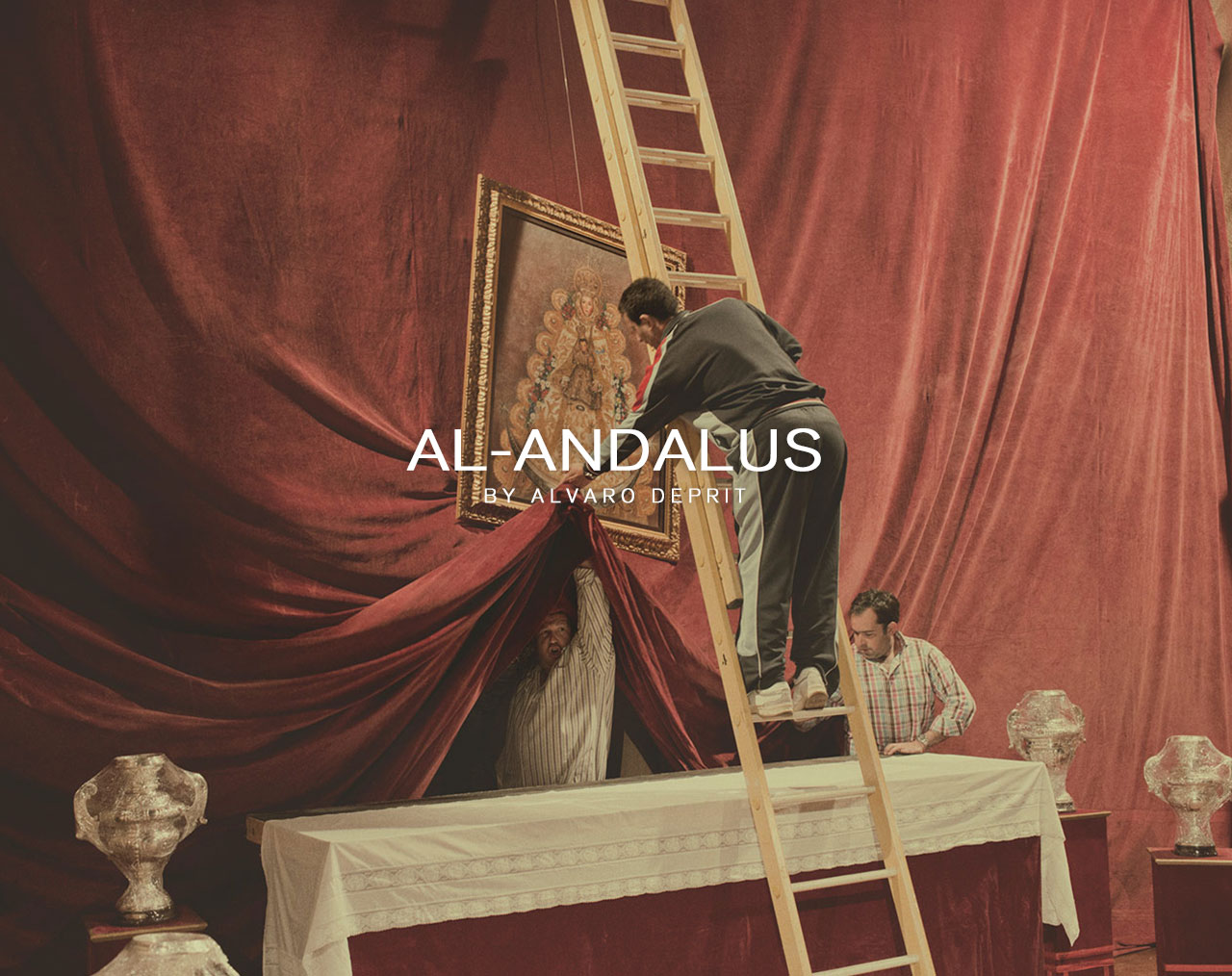

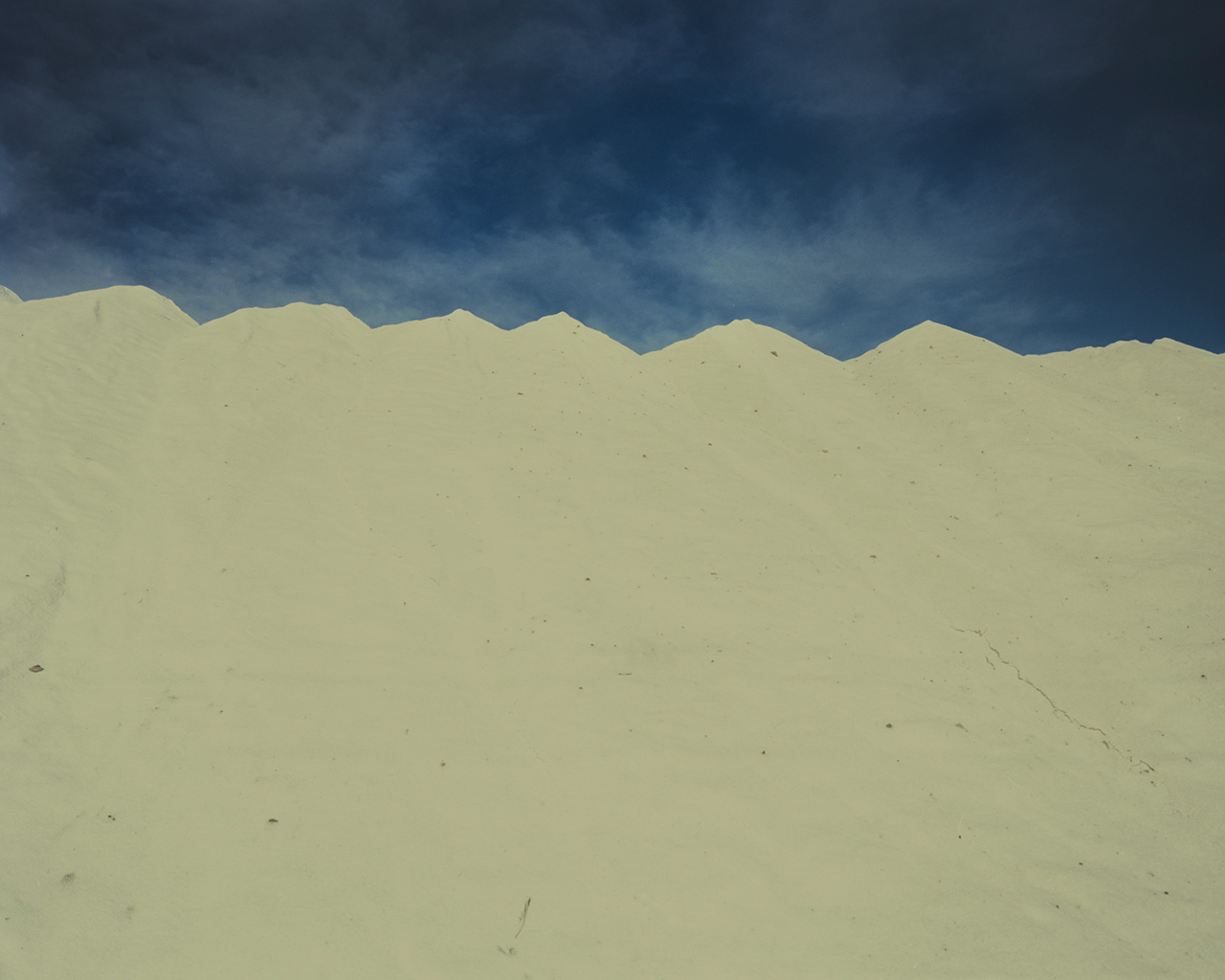

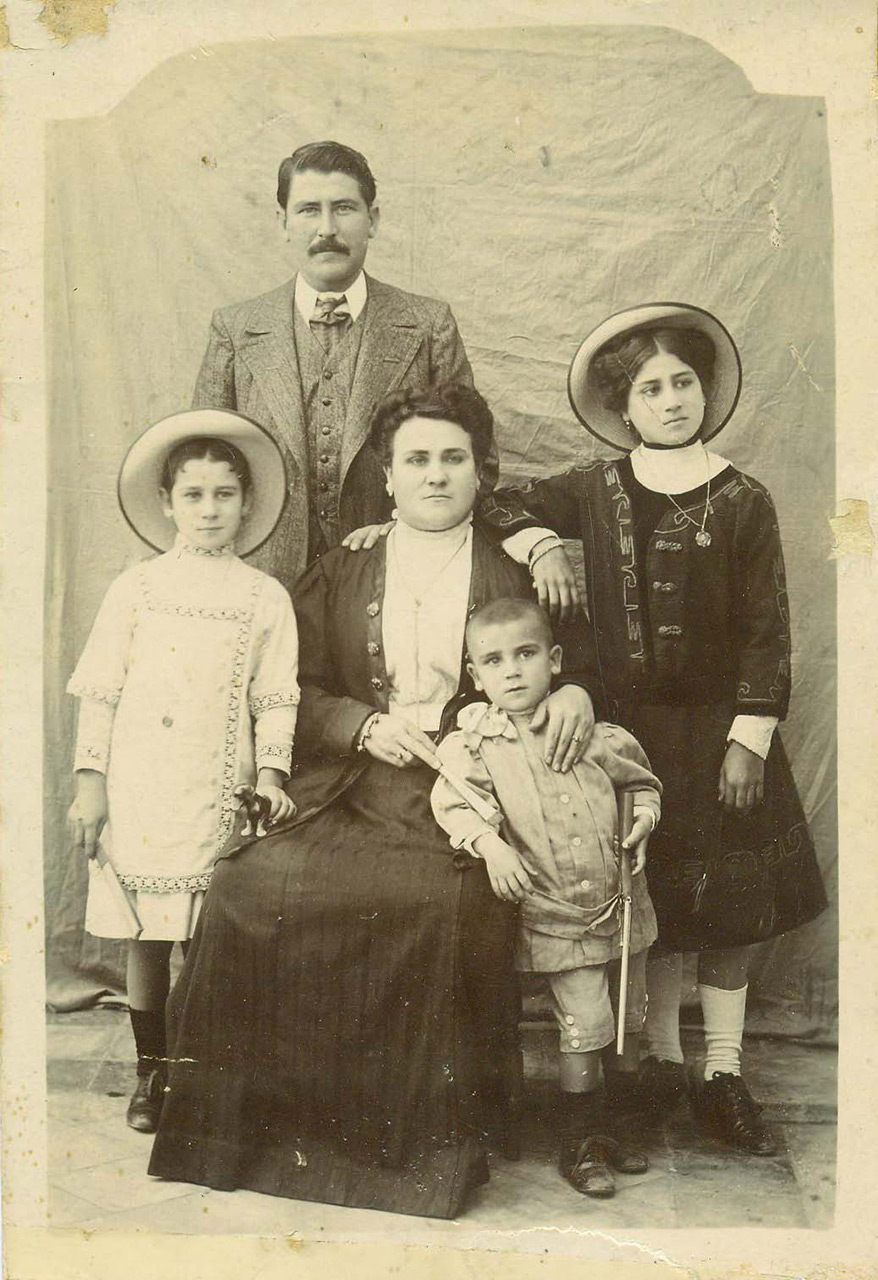

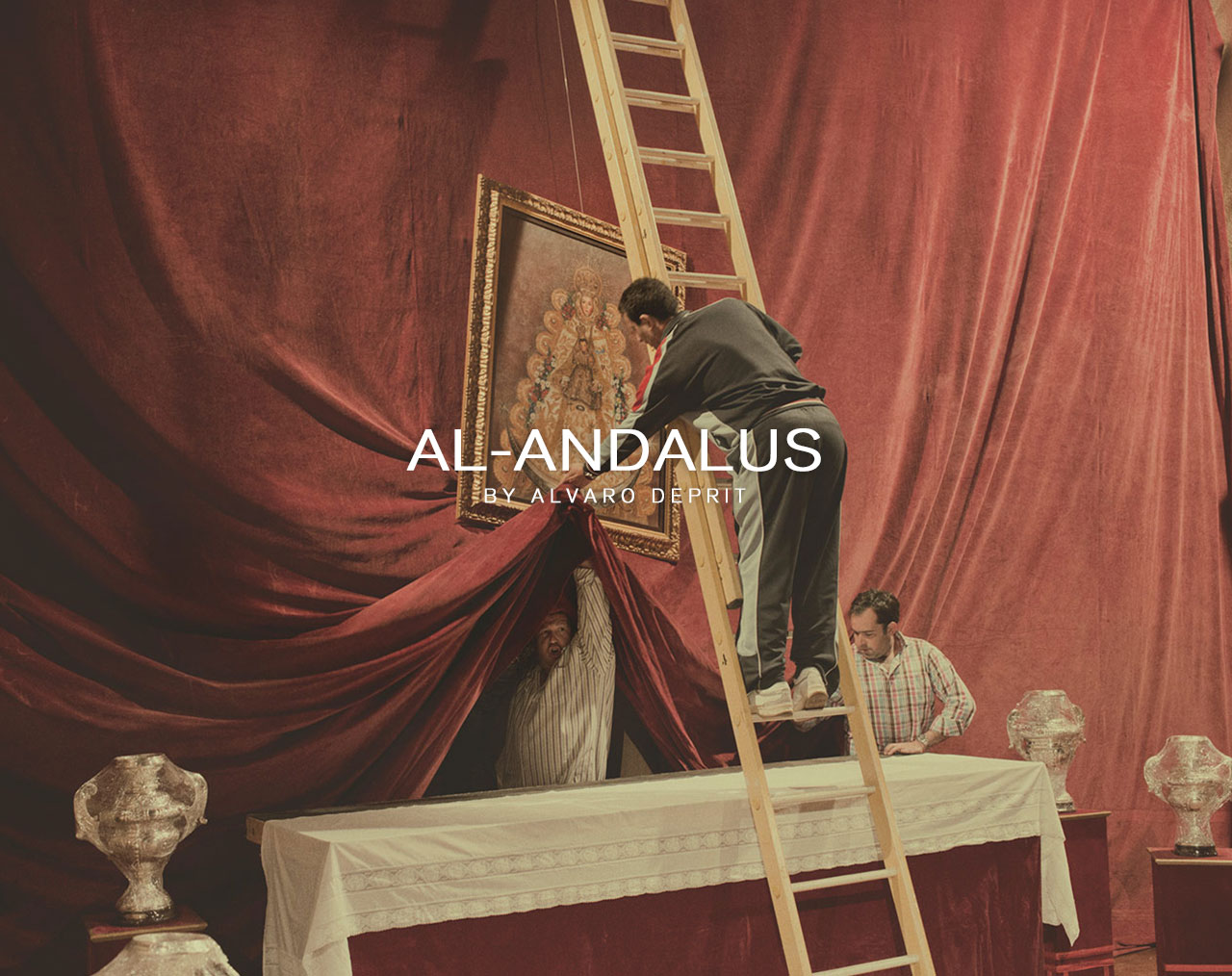

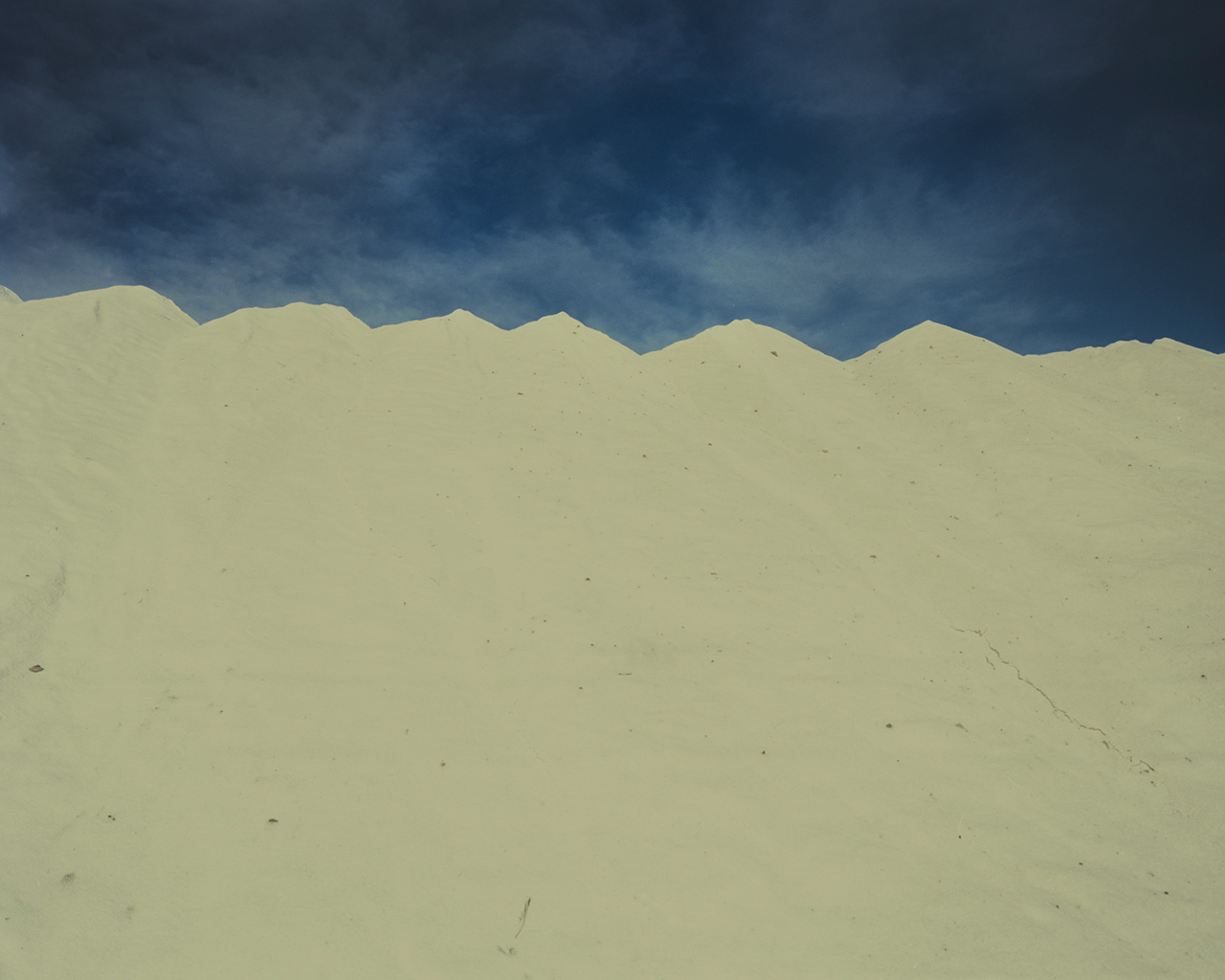

At home I always used to linger with curiosity at an old photograph of some of my Andalusian relatives. With the passing of years this photograph has given me an image of how I think Andalusia might be.

Al-Andalus is the result of approximately three years of research in the south of Spain, an area I did not know nor in which I have lived, but which is my family’s place of origin and current place of residence.

My initial interest was in the tension I perceived between tradition and the marks of the global world. Andalusia is the result of a complex cultural stratification, derived from the passage of civilisations which, over time, gave life to a hybrid identity capable of containing within it the stereotypical traits of Spanish culture.

Journeying through Andalusia now that it has been hit hard by the economic crisis has made me reflect on the collision of the diverse elements in this land – a land which, as I see it, has shown itself to be hanging in the balance, almost in a state between reality and fiction as the background of a movie.

My intention has not been to reproduce the tangible aspects of a place, but to give shape to a body of memories and impressions born of my personal history or of something unconcluded. Concentrated in the images are visible apparitions whose existence is a mystery, while on the other hand, the mystery is something real in the mind, through the repeating, varying, developing and transposing elements of the memory.

Alvaro Deprit (Madrid). Has been living in Italy since 2004. He studied German Philology at the Complutense University of Madrid and at the Otto Friedrich University of Bamberg, Germany. He also studied Sociology at the University d’Annunzio in Chieti, Italy. Alvaro’s work has been exhibited in festivals and galleries all over the world and has been published in international magazines. He won the PHotoEspaña OjodePez Human Values Award, the BJP’s International Photography Award and the Viewbook Photostory Contest, and he was a finalist in Voies Off Arles, Leica Oskar Barnack Award and Sony Award.

Alvaro Deprit (Madrid). Has been living in Italy since 2004. He studied German Philology at the Complutense University of Madrid and at the Otto Friedrich University of Bamberg, Germany. He also studied Sociology at the University d’Annunzio in Chieti, Italy. Alvaro’s work has been exhibited in festivals and galleries all over the world and has been published in international magazines. He won the PHotoEspaña OjodePez Human Values Award, the BJP’s International Photography Award and the Viewbook Photostory Contest, and he was a finalist in Voies Off Arles, Leica Oskar Barnack Award and Sony Award.

At home I always used to linger with curiosity at an old photograph of some of my Andalusian relatives. With the passing of years this photograph has given me an image of how I think Andalusia might be.

Al-Andalus is the result of approximately three years of research in the south of Spain, an area I did not know nor in which I have lived, but which is my family’s place of origin and current place of residence.

My initial interest was in the tension I perceived between tradition and the marks of the global world. Andalusia is the result of a complex cultural stratification, derived from the passage of civilisations which, over time, gave life to a hybrid identity capable of containing within it the stereotypical traits of Spanish culture.

Journeying through Andalusia now that it has been hit hard by the economic crisis has made me reflect on the collision of the diverse elements in this land – a land which, as I see it, has shown itself to be hanging in the balance, almost in a state between reality and fiction as the background of a movie.

My intention has not been to reproduce the tangible aspects of a place, but to give shape to a body of memories and impressions born of my personal history or of something unconcluded. Concentrated in the images are visible apparitions whose existence is a mystery, while on the other hand, the mystery is something real in the mind, through the repeating, varying, developing and transposing elements of the memory.

Alvaro Deprit (Madrid). Has been living in Italy since 2004. He studied German Philology at the Complutense University of Madrid and at the Otto Friedrich University of Bamberg, Germany. He also studied Sociology at the University d’Annunzio in Chieti, Italy. Alvaro’s work has been exhibited in festivals and galleries all over the world and has been published in international magazines. He won the PHotoEspaña OjodePez Human Values Award, the BJP’s International Photography Award and the Viewbook Photostory Contest, and he was a finalist in Voies Off Arles, Leica Oskar Barnack Award and Sony Award.

Alvaro Deprit (Madrid). Has been living in Italy since 2004. He studied German Philology at the Complutense University of Madrid and at the Otto Friedrich University of Bamberg, Germany. He also studied Sociology at the University d’Annunzio in Chieti, Italy. Alvaro’s work has been exhibited in festivals and galleries all over the world and has been published in international magazines. He won the PHotoEspaña OjodePez Human Values Award, the BJP’s International Photography Award and the Viewbook Photostory Contest, and he was a finalist in Voies Off Arles, Leica Oskar Barnack Award and Sony Award.Valentina Vannicola

# 01

Canto III, Ante-Inferno

The Gates of Hell

Through me the way to the city of woe,

Through me the way to eternal pain,

Through me the way among the lost.

vv. 1-3

# 02

Canto III, Ante-Inferno

Slothful

… ‘This miserable state is borne

by the wretched souls of those who lived

without disgrace yet without praise.’

vv. 34-36

# 03

Canto III, Ante-Inferno

Crossing of the Acheron

‘all those who die in the wrath of God

assemble here from every land.

And they are eager to cross the river,

for the justice of God so spurs them on

their very fear is turned to longing.’

vv. 122-126

# 04

Canto IV, Circle I

Limbo

Thus he went first and had me enter

the first circle girding the abyss.

Here, as far as I could tell by listening,

was no lamentation other than the sighs

that kept the air forever trembling.

These came from grief without torment.

vv. 23-28

# 05

Canto V, Circle II

Lustful

As doves, summoned by desire, their wings

outstretched and motionless, move on the air,

borne by their will to the sweet nest

vv. 82-84

# 06

Canto VI, Circle III

Gluttonous

The rain makes them howl like dogs

The unholy wretches often turn their bodies,

making of one side a shield for the other.

vv. 19-21

# 07

Canto VII, Circle IV

Avaricious

Here the sinners were more numerous than

elsewhere,

and they, with great shouts, from opposite sides

were shoving burdens forward with their chests.

vv. 25-27

# 08

Canto VII, Circle V

Wrathful and Sullen

And I, my gaze transfixed, could see

people with angry faces in that bog,

naked, their bodies smeared with mud.

vv. 109-111

# 09

Canto IX, Circle VI

Heretics

And he: ‘Here, with all their followers,

are the arch-heretics of every sect.

The tombs are far more laden than you think…’

vv. 127-129

# 10

Canto X, Circle VI

Farinata degli Umberti, Heretics

Already I had fixed my gaze on his.

And he was rising, lifting chest and brow

as though he held all Hell in utter scorn.

vv. 34-36

# 11

Canto XIII, Circle VII, Ring II

Suicides

We will come to claim our cast-off bodies

like the others. But it would not be just if we again

put on the flesh we robbed from our own souls.

Here shall we drag it, and in this dismal wood

our bodies will be hung, each one

upon the thorn-bush of its painful shade.

vv. 103-108

# 12

Canto XVIII, Circle VIII, Bolgia II

Flatterers, Thaïs

And then my leader said to me: ‘Try to thrust

your face a little farther forward,

to get a better picture of the features

of that foul, dishevelled wench down there,

scratching herself with her filthy nails.

Now she squats and now she’s standing up…’

vv. 127-132

# 13

Canto XIX, Circle VIII, Bolgia III

Simoniacs

From the mouth of each stuck out

a sinner’s feet and legs up to the thighs

while all the rest stayed in the hole.

vv. 22-24

# 14

Canto XXIX, Circle VIII, Bolgia X

Counterfeiters

Some lay upon the bellies or the backs

of others, still others dragged themselves

on hands and knees along that gloomy path.

Step by step we went ahead in silence,

looking and listening to the stricken spirits,

who could not raise their bodies from the ground.

vv. 67-72

# 15

Canto XXX, Circle VIII, Bolgia X

Counterfeiters, Master Adam

he said, ‘behold and then consider

the suffering of Master Adam.

Alive, I had in plenty all I wanted.

And now I crave a single drop of water!’

vv. 60-63

Inferno is a set of surrealistic scenes recreating Dante’s journey through the strata of hell. The protagonists, who represent some passages of the poem, are inhabitants of the photographer’s town, Tolfa. Italy. April 2010 - March 2011

ZZ. In which way media like cinema, theatre and literature have had an effect on your photographic projects

VV. The university studies I undertook before my photographic studies concentrated on the cinematographic art, and were within a humanities faculty where theatre and literature were certainly very present subjects. As well as this academic aspect, the experiences I had autonomously and often by chance also nourished my interests in these worlds. I don’t know the exact point these interact with my projects – certainly at the base of my work there is a strong narrative need where it is difficult for me to consider the individual shot in isolation from the whole. In most cases, I develop my story in a particular geographical area, then there is the study of this area and the involvement if its inhabitants, then, I move onto the staging. If I work on a literary text, whether it is Don Quixote or Dante’s Inferno, I start from an in-depth analysis of the text, arriving then at its schematisation, then to its re-composition according to my narrative intent and finally, the creation of a storyboard. I started to use this purely cinematographic technique not for an intellectual reason but for a question of practicality, putting into practice and adopting in my planning phase this previously studied method that very much facilitates my construction of the narration.

ZZ. In your Inferno series you staged images with non-professional actors from your hometown, what were you looking to trigger and what results did you get?

VV. As I mentioned, in all the projects I have undertaken until now, I have worked on a particular geographical area, with the involvement of its inhabitants for the staging of the stories and often for the planning. I started out with little “experiments” in my hometown – of which Dante’s Inferno represents perhaps a more aware phase – then concentrating on attempting to take this experiment outside my territorial borders. So followed Living Layers, a project on a Roman neighbourhood, born in collaboration with the Wunderkammern Gallery and Rome’s MACRO (Museum of Contemporary Art of Rome), and Riviere, which I just completed for the Bellaria Film Festival, in the Emilia Romagna region of Italy. In my research, I try to deepen my study of the areas where I am working and particularly, to seek out collaborations with the people who live there, not just for interpreting characters in the story but also for the construction of the story, whether on a practical or narrative level.

Dante’s Inferno is from 2011 and it came after other projects where I worked in my native Tolfa, a small town north of Rome. It is a more mature project compared with those that came before, both for my work on the literary text and on its inhabitants. The study and planning phase took a long time – the study and the decomposition of a text of such poetic intellect required a lot of patience, as did constructing and bringing to conclusion the 15 shots that comprise the work, which took a year. During this time, the project became rooted in the population and in the end the result was a kind of unison. The town was active on a number of fronts, from finding materials and garments for the scenes, to the involvement of other extras and suggesting locations they had seen during their days working in the fields. It is a project that very much fed my interest in this type of research, which I continue to take forward in its variations.

ZZ. How has this experience influenced your current interests?

VV. This type of experience repeats itself in different ways in almost all of my work. Looking for an interaction with a place and its inhabitants is the point I seek keep constant in my stories. Just a few weeks ago, I finished new work on an area that I had never visited before then – the Romagnola Riviera, on the coast of the Emilia Romagna region. During the summer time, it transforms into an hive of tourists, with hundreds of geometrically placed and chaotically crowded beach umbrellas, boat trips, bocce matches, lunches at the pensione, and theme parks – a very noisy world which, during the winter, suddenly disappears and makes way for something even more surreal, and my arrival happened exactly at that moment: the Romagnola Riviera in winter, a great sleeping city where everything is suspended on the edge of waiting; the Riviera in the off season: pastel coloured rows of closed hotels and pensiones, enormous plastic play and games equipment and palm trees wrapped in transparent towelling on the beach, everything protected in sleep. More than the taste of waiting, every element seemed to recall something that had been infinite before, in a timeless age. In this temporal suspension, retired fishermen, dancers from the dance hall of the centre for the elderly, new friends and hoteliers ferried me through this new story, entitled Riviere. The story begins from an investigation into facts that actually occurred in the 1960s – the construction of an island in the neighbouring Adriatic waters and its bombing by the Italian state – events that weave in with the story of my grandparents and their photographic archive from 1990 to 2000, and finishes with my arrival at Rimini station in January 2014.

Valentina Vannicola (Italy, 1982). Lives and works in Italy. After a degree in Film Studies at the Sapienza University of Rome, she went on to a diploma in photography at the Scuola Romana di Fotografia. Her images are strongly influenced by cinema, theatre and literature. Her work, for which she has received several awards, has been exhibited in France, Australia, Austria and Italy. She is represented by OnOff Picture Photo Agency and by the Wunderkammern Gallery.

Valentina Vannicola (Italy, 1982). Lives and works in Italy. After a degree in Film Studies at the Sapienza University of Rome, she went on to a diploma in photography at the Scuola Romana di Fotografia. Her images are strongly influenced by cinema, theatre and literature. Her work, for which she has received several awards, has been exhibited in France, Australia, Austria and Italy. She is represented by OnOff Picture Photo Agency and by the Wunderkammern Gallery.

# 01

Canto III, Ante-Inferno

The Gates of Hell

Through me the way to the city of woe,

Through me the way to eternal pain,

Through me the way among the lost.

vv. 1-3

# 02

Canto III, Ante-Inferno

Slothful

… ‘This miserable state is borne

by the wretched souls of those who lived

without disgrace yet without praise.’

vv. 34-36

# 03

Canto III, Ante-Inferno

Crossing of the Acheron

‘all those who die in the wrath of God

assemble here from every land.

And they are eager to cross the river,

for the justice of God so spurs them on

their very fear is turned to longing.’

vv. 122-126

# 04

Canto IV, Circle I

Limbo

Thus he went first and had me enter

the first circle girding the abyss.

Here, as far as I could tell by listening,

was no lamentation other than the sighs

that kept the air forever trembling.

These came from grief without torment.

vv. 23-28

# 05

Canto V, Circle II

Lustful

As doves, summoned by desire, their wings

outstretched and motionless, move on the air,

borne by their will to the sweet nest

vv. 82-84

# 06

Canto VI, Circle III

Gluttonous

The rain makes them howl like dogs

The unholy wretches often turn their bodies,

making of one side a shield for the other.

vv. 19-21

# 07

Canto VII, Circle IV

Avaricious

Here the sinners were more numerous than

elsewhere,

and they, with great shouts, from opposite sides

were shoving burdens forward with their chests.

vv. 25-27

# 08

Canto VII, Circle V

Wrathful and Sullen

And I, my gaze transfixed, could see

people with angry faces in that bog,

naked, their bodies smeared with mud.

vv. 109-111

# 09

Canto IX, Circle VI

Heretics

And he: ‘Here, with all their followers,

are the arch-heretics of every sect.

The tombs are far more laden than you think…’

vv. 127-129

# 10

Canto X, Circle VI

Farinata degli Umberti, Heretics

Already I had fixed my gaze on his.

And he was rising, lifting chest and brow

as though he held all Hell in utter scorn.

vv. 34-36

# 11

Canto XIII, Circle VII, Ring II

Suicides

We will come to claim our cast-off bodies

like the others. But it would not be just if we again

put on the flesh we robbed from our own souls.

Here shall we drag it, and in this dismal wood

our bodies will be hung, each one

upon the thorn-bush of its painful shade.

vv. 103-108

# 12

Canto XVIII, Circle VIII, Bolgia II

Flatterers, Thaïs

And then my leader said to me: ‘Try to thrust

your face a little farther forward,

to get a better picture of the features

of that foul, dishevelled wench down there,

scratching herself with her filthy nails.

Now she squats and now she’s standing up…’

vv. 127-132

# 13

Canto XIX, Circle VIII, Bolgia III

Simoniacs

From the mouth of each stuck out

a sinner’s feet and legs up to the thighs

while all the rest stayed in the hole.

vv. 22-24

# 14

Canto XXIX, Circle VIII, Bolgia X

Counterfeiters

Some lay upon the bellies or the backs

of others, still others dragged themselves

on hands and knees along that gloomy path.

Step by step we went ahead in silence,

looking and listening to the stricken spirits,

who could not raise their bodies from the ground.

vv. 67-72

# 15

Canto XXX, Circle VIII, Bolgia X

Counterfeiters, Master Adam

he said, ‘behold and then consider

the suffering of Master Adam.

Alive, I had in plenty all I wanted.

And now I crave a single drop of water!’

vv. 60-63

Inferno is a set of surrealistic scenes recreating Dante’s journey through the strata of hell. The protagonists, who represent some passages of the poem, are inhabitants of the photographer’s town, Tolfa. Italy. April 2010 - March 2011

ZZ. In which way media like cinema, theatre and literature have had an effect on your photographic projects

VV. The university studies I undertook before my photographic studies concentrated on the cinematographic art, and were within a humanities faculty where theatre and literature were certainly very present subjects. As well as this academic aspect, the experiences I had autonomously and often by chance also nourished my interests in these worlds. I don’t know the exact point these interact with my projects – certainly at the base of my work there is a strong narrative need where it is difficult for me to consider the individual shot in isolation from the whole. In most cases, I develop my story in a particular geographical area, then there is the study of this area and the involvement if its inhabitants, then, I move onto the staging. If I work on a literary text, whether it is Don Quixote or Dante’s Inferno, I start from an in-depth analysis of the text, arriving then at its schematisation, then to its re-composition according to my narrative intent and finally, the creation of a storyboard. I started to use this purely cinematographic technique not for an intellectual reason but for a question of practicality, putting into practice and adopting in my planning phase this previously studied method that very much facilitates my construction of the narration.

ZZ. In your Inferno series you staged images with non-professional actors from your hometown, what were you looking to trigger and what results did you get?

VV. As I mentioned, in all the projects I have undertaken until now, I have worked on a particular geographical area, with the involvement of its inhabitants for the staging of the stories and often for the planning. I started out with little “experiments” in my hometown – of which Dante’s Inferno represents perhaps a more aware phase – then concentrating on attempting to take this experiment outside my territorial borders. So followed Living Layers, a project on a Roman neighbourhood, born in collaboration with the Wunderkammern Gallery and Rome’s MACRO (Museum of Contemporary Art of Rome), and Riviere, which I just completed for the Bellaria Film Festival, in the Emilia Romagna region of Italy. In my research, I try to deepen my study of the areas where I am working and particularly, to seek out collaborations with the people who live there, not just for interpreting characters in the story but also for the construction of the story, whether on a practical or narrative level.

Dante’s Inferno is from 2011 and it came after other projects where I worked in my native Tolfa, a small town north of Rome. It is a more mature project compared with those that came before, both for my work on the literary text and on its inhabitants. The study and planning phase took a long time – the study and the decomposition of a text of such poetic intellect required a lot of patience, as did constructing and bringing to conclusion the 15 shots that comprise the work, which took a year. During this time, the project became rooted in the population and in the end the result was a kind of unison. The town was active on a number of fronts, from finding materials and garments for the scenes, to the involvement of other extras and suggesting locations they had seen during their days working in the fields. It is a project that very much fed my interest in this type of research, which I continue to take forward in its variations.

ZZ. How has this experience influenced your current interests?

VV. This type of experience repeats itself in different ways in almost all of my work. Looking for an interaction with a place and its inhabitants is the point I seek keep constant in my stories. Just a few weeks ago, I finished new work on an area that I had never visited before then – the Romagnola Riviera, on the coast of the Emilia Romagna region. During the summer time, it transforms into an hive of tourists, with hundreds of geometrically placed and chaotically crowded beach umbrellas, boat trips, bocce matches, lunches at the pensione, and theme parks – a very noisy world which, during the winter, suddenly disappears and makes way for something even more surreal, and my arrival happened exactly at that moment: the Romagnola Riviera in winter, a great sleeping city where everything is suspended on the edge of waiting; the Riviera in the off season: pastel coloured rows of closed hotels and pensiones, enormous plastic play and games equipment and palm trees wrapped in transparent towelling on the beach, everything protected in sleep. More than the taste of waiting, every element seemed to recall something that had been infinite before, in a timeless age. In this temporal suspension, retired fishermen, dancers from the dance hall of the centre for the elderly, new friends and hoteliers ferried me through this new story, entitled Riviere. The story begins from an investigation into facts that actually occurred in the 1960s – the construction of an island in the neighbouring Adriatic waters and its bombing by the Italian state – events that weave in with the story of my grandparents and their photographic archive from 1990 to 2000, and finishes with my arrival at Rimini station in January 2014.

Valentina Vannicola (Italy, 1982). Lives and works in Italy. After a degree in Film Studies at the Sapienza University of Rome, she went on to a diploma in photography at the Scuola Romana di Fotografia. Her images are strongly influenced by cinema, theatre and literature. Her work, for which she has received several awards, has been exhibited in France, Australia, Austria and Italy. She is represented by OnOff Picture Photo Agency and by the Wunderkammern Gallery.

Valentina Vannicola (Italy, 1982). Lives and works in Italy. After a degree in Film Studies at the Sapienza University of Rome, she went on to a diploma in photography at the Scuola Romana di Fotografia. Her images are strongly influenced by cinema, theatre and literature. Her work, for which she has received several awards, has been exhibited in France, Australia, Austria and Italy. She is represented by OnOff Picture Photo Agency and by the Wunderkammern Gallery.