Vanessa Alcaíno & Alejandro Malo

Brown Hooded Kingfisher, (Halcyon albiventris), Chitengo Camp, Gorongosa National Park, Mozambique, 2011. By Joel Sartore

When we choose to address a landscape issue and, soon after, we realized its relationship with the theme of the FotoFest 2016 Biennial: Changing Circumstances: Looking at the Future of the Planet, we thought it appropriate to echo the concerns expressed during the festival. A few contents presented in this issue offer a digital version of the same exhibitions for our audience. However, this observation would be insufficient without emphasizing some of the ideas included in the book of the same name that drives us to insist on the invitation to peer into its pages.

Conceived as a collaboration between Frederick Baldwin and Wendy Watriss, founders of FotoFest, with Steven Evans, Executive Director of the festival, it integrates a diverse and broad mosaic of artists. In his introductory text, Steven Evans highlights the need to promote the exchange of ideas between artists who use different strategies to address the issue. It also contrast the divergence of gazes with the unifying leitmotif of Thomas E. Lovejoy and Geof Rayner essays that show an intrinsic connection between all artist’s concerns. Both essays provide strong arguments on the urgent need for action on climate change; the first, from the perspective of the Earth as a living organism, and the second by demonstrating the decisive role of human beings in their environment.

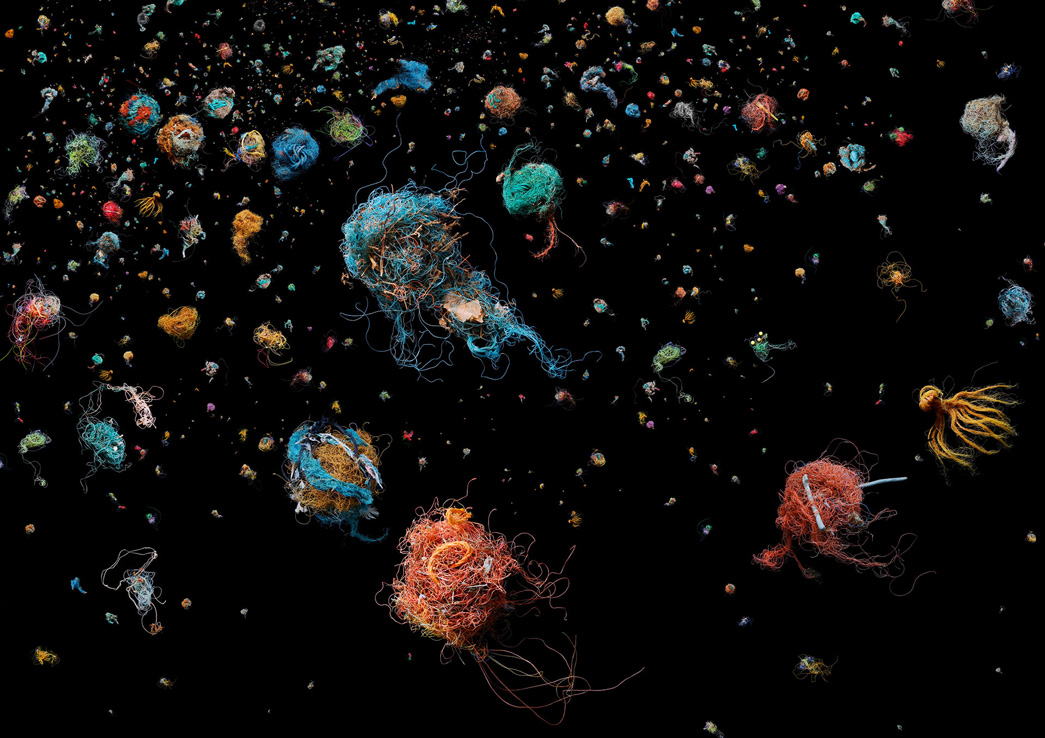

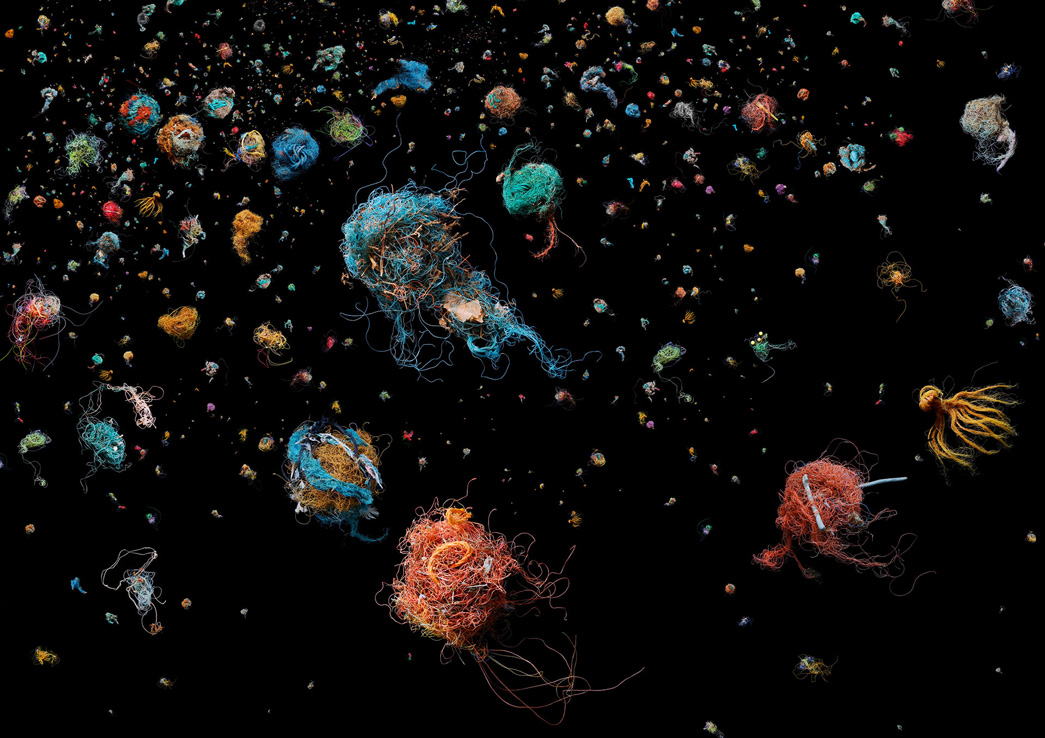

Bird’s Nest, 2011. Por Mandy Barker

Finally, Wendy Watriss gives voice to some questions that resonate with concerns we encountered during our research on the theme of landscape: "We have responsibility not only for our own well-being but that of the rest of the natural world? Can art stimulate new perspectives and new ways of seeing?” Photography has in its hands the potential to share with us realities that otherwise would be inaccessible. The images are not neutral, they feed imagination and foster reflections, being a very effective means to make any problem palpable, visible and close, to the point of being able to bring them into the political sphere and encourage agreements. We agree with Wendy’s view that art can itself stimulate and expand our world view and present innovative ways to address the issue of climate change. We should not allow ourselves to have skewed visions that only address and speak from a knowledge area or a region of the world. We must open to different cultures, include divergent views, draw new and different boundaries, create unique maps, put the world upside down, stir and divide it in various ways. That is the only way to visualize a future where rather than dominate nature, we can collaborate for its survival and ours. And this way of ‘seeing’ the world, and the new paths to our future, is what art may best express.

Vanessa Alcaíno Pizani (Venezuela, 1980). Lives and works in Mexico. Visual artist. She graduated in Philosophy at the Central University of Venezuela and has a Master’s degree in Spanish and Latin American Thought at the Autonomous University of Madrid (UAM). Since 1994, she has worked in the field of photography at various institutions and organisations in Venezuela, Argentina and Mexico. At the moment, she is part of the editorial team of zonezero.com.

Vanessa Alcaíno Pizani (Venezuela, 1980). Lives and works in Mexico. Visual artist. She graduated in Philosophy at the Central University of Venezuela and has a Master’s degree in Spanish and Latin American Thought at the Autonomous University of Madrid (UAM). Since 1994, she has worked in the field of photography at various institutions and organisations in Venezuela, Argentina and Mexico. At the moment, she is part of the editorial team of zonezero.com. Alejandro Malo (Mexico, 1972). Lives and works in Mexico and is the director of ZoneZero. Since 1993, he has taken part in various cultural projects and worked as an information technology consultant. He has collaborated in print and electronic publications, and given workshops and conferences on literature, creative writing, storytelling and technology. In 2009, Malo joined the team of the Fundación Pedro Meyer, where he directs the Archives and Technology departments.

Alejandro Malo (Mexico, 1972). Lives and works in Mexico and is the director of ZoneZero. Since 1993, he has taken part in various cultural projects and worked as an information technology consultant. He has collaborated in print and electronic publications, and given workshops and conferences on literature, creative writing, storytelling and technology. In 2009, Malo joined the team of the Fundación Pedro Meyer, where he directs the Archives and Technology departments.

Brown Hooded Kingfisher, (Halcyon albiventris), Chitengo Camp, Gorongosa National Park, Mozambique, 2011. By Joel Sartore

When we choose to address a landscape issue and, soon after, we realized its relationship with the theme of the FotoFest 2016 Biennial: Changing Circumstances: Looking at the Future of the Planet, we thought it appropriate to echo the concerns expressed during the festival. A few contents presented in this issue offer a digital version of the same exhibitions for our audience. However, this observation would be insufficient without emphasizing some of the ideas included in the book of the same name that drives us to insist on the invitation to peer into its pages.

Conceived as a collaboration between Frederick Baldwin and Wendy Watriss, founders of FotoFest, with Steven Evans, Executive Director of the festival, it integrates a diverse and broad mosaic of artists. In his introductory text, Steven Evans highlights the need to promote the exchange of ideas between artists who use different strategies to address the issue. It also contrast the divergence of gazes with the unifying leitmotif of Thomas E. Lovejoy and Geof Rayner essays that show an intrinsic connection between all artist’s concerns. Both essays provide strong arguments on the urgent need for action on climate change; the first, from the perspective of the Earth as a living organism, and the second by demonstrating the decisive role of human beings in their environment.

Bird’s Nest, 2011. Por Mandy Barker

Finally, Wendy Watriss gives voice to some questions that resonate with concerns we encountered during our research on the theme of landscape: "We have responsibility not only for our own well-being but that of the rest of the natural world? Can art stimulate new perspectives and new ways of seeing?” Photography has in its hands the potential to share with us realities that otherwise would be inaccessible. The images are not neutral, they feed imagination and foster reflections, being a very effective means to make any problem palpable, visible and close, to the point of being able to bring them into the political sphere and encourage agreements. We agree with Wendy’s view that art can itself stimulate and expand our world view and present innovative ways to address the issue of climate change. We should not allow ourselves to have skewed visions that only address and speak from a knowledge area or a region of the world. We must open to different cultures, include divergent views, draw new and different boundaries, create unique maps, put the world upside down, stir and divide it in various ways. That is the only way to visualize a future where rather than dominate nature, we can collaborate for its survival and ours. And this way of ‘seeing’ the world, and the new paths to our future, is what art may best express.

Vanessa Alcaíno Pizani (Venezuela, 1980). Lives and works in Mexico. Visual artist. She graduated in Philosophy at the Central University of Venezuela and has a Master’s degree in Spanish and Latin American Thought at the Autonomous University of Madrid (UAM). Since 1994, she has worked in the field of photography at various institutions and organisations in Venezuela, Argentina and Mexico. At the moment, she is part of the editorial team of zonezero.com.

Vanessa Alcaíno Pizani (Venezuela, 1980). Lives and works in Mexico. Visual artist. She graduated in Philosophy at the Central University of Venezuela and has a Master’s degree in Spanish and Latin American Thought at the Autonomous University of Madrid (UAM). Since 1994, she has worked in the field of photography at various institutions and organisations in Venezuela, Argentina and Mexico. At the moment, she is part of the editorial team of zonezero.com. Alejandro Malo (Mexico, 1972). Lives and works in Mexico and is the director of ZoneZero. Since 1993, he has taken part in various cultural projects and worked as an information technology consultant. He has collaborated in print and electronic publications, and given workshops and conferences on literature, creative writing, storytelling and technology. In 2009, Malo joined the team of the Fundación Pedro Meyer, where he directs the Archives and Technology departments.

Alejandro Malo (Mexico, 1972). Lives and works in Mexico and is the director of ZoneZero. Since 1993, he has taken part in various cultural projects and worked as an information technology consultant. He has collaborated in print and electronic publications, and given workshops and conferences on literature, creative writing, storytelling and technology. In 2009, Malo joined the team of the Fundación Pedro Meyer, where he directs the Archives and Technology departments.Alejandro Malo

Cloud Phenomena of Maloja. Film by Arnold Fanck, 1924

Landscape, long before being image, was literature and longing. Since ancient times, almost every civilization led an educated class that longed to return to the simple life of the countryside, back to nature with its deeper order and less troubled appearance. In the West, despite its widespread tradition against the city life and akin to recover the rural simplicity, it is only during the Renaissance that the joy of those running away from the maddening crowds turns into the full enjoyment of nature, first in poetry and only afterwards as a growing presence in paintings. In the East, at least since China’s Tang Dynasty, a fertile dialogue is established around the landscape between poetry and painting, and the genre develops very soon and evolves in multiple aspects.

Centuries later, while other visual media were confronted by the emergence of photography to take in and emphasize the subjectivity of their gaze over this topic, photographic landscapes devote their attention to exoticism or the magnificence of natural views and offered a deceptive closeness to a naturalist interpretation. The romantic vision of nature took root strongly across images ranging from the Bisson brothers to Ansel Adams. In them, beauty was something external to be captured in each shot, a reserve where solitude was a regained innocence and open spaces offered an inexhaustible source of peacefulness for the contemplative eye under the changing light’s mantle.

Gradually, as these perspectives became advertising and marketing leitmotifs, this genre had to be reinvented and new possibilities sought elsewhere. Already in 1975, with the exhibition New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-Altered Landscape, it became clear that human intervention was inseparable from our new perception of landscape. The aseptic style of the authors gathered in this exhibition, considered almost forensic and where the emotional charge seemed absent, caused the sensation of being somehow close to a crime scene’s lingering memories, but devoid of its dramatic charge. During the following years, some authors, with a similar methodology but against this trend, looked after landscapes as representation of their own temperament, metaphor of an inner life that finds in the environment an affinity and a strong individual expressive capacity. Finally, photography assumed the same subjectivity of other means. As an example, Hiroshi Sugimoto wrote about his Seascapes: "Every time I view the sea, I feel a calming sense of security, as if visiting my ancestral home". In that phrase, anyone can guess a sort of poetic inclination and a strong artistic weight that facilitates dialogue with paintings, as was done in 2012 by exposing this series with Mark Rothko’s work.

However, Eden’s innocence became impossible in a world where human presence outreach tainted glaciers and forests with the same nonchalance. In the second half of the twentieth century, the landscape was transformed from man facing nature, to be a metaphor for our own humanity and, at the same time, scene of our fears, hopes and tragedies. We read as landscape every place where a scenario simulates an open space, no matter whether an emotional or conceptual projection of ourselves, but also we read it under the titanic action of mining, between the megalopolis’ streets or against the inventiveness of major transformation projects. Hybridization of genres has allowed the unreal calm of sensationalist scenes as in Fernando Brito’s pictures and the catastrophe of Chinese dumping sites of Yao Lu to be shown as images of bucolic appearance. We bit the fruit of our pride and today paradise is a shy promise. We need to build works, with concrete actions to transform the announced catastrophe in a redemptive epiphany. The landscape is, with its potential for imagination and denunciation, the much needed tool.

Alejandro Malo (Mexico, 1972). Lives and works in Mexico and is the director of ZoneZero. Since 1993, he has taken part in various cultural projects and worked as an information technology consultant. He has collaborated in print and electronic publications, and given workshops and conferences on literature, creative writing, storytelling and technology. In 2009, Malo joined the team of the Fundación Pedro Meyer, where he directs the Archives and Technology departments.

Alejandro Malo (Mexico, 1972). Lives and works in Mexico and is the director of ZoneZero. Since 1993, he has taken part in various cultural projects and worked as an information technology consultant. He has collaborated in print and electronic publications, and given workshops and conferences on literature, creative writing, storytelling and technology. In 2009, Malo joined the team of the Fundación Pedro Meyer, where he directs the Archives and Technology departments.

Cloud Phenomena of Maloja. Film by Arnold Fanck, 1924

Landscape, long before being image, was literature and longing. Since ancient times, almost every civilization led an educated class that longed to return to the simple life of the countryside, back to nature with its deeper order and less troubled appearance. In the West, despite its widespread tradition against the city life and akin to recover the rural simplicity, it is only during the Renaissance that the joy of those running away from the maddening crowds turns into the full enjoyment of nature, first in poetry and only afterwards as a growing presence in paintings. In the East, at least since China’s Tang Dynasty, a fertile dialogue is established around the landscape between poetry and painting, and the genre develops very soon and evolves in multiple aspects.

Centuries later, while other visual media were confronted by the emergence of photography to take in and emphasize the subjectivity of their gaze over this topic, photographic landscapes devote their attention to exoticism or the magnificence of natural views and offered a deceptive closeness to a naturalist interpretation. The romantic vision of nature took root strongly across images ranging from the Bisson brothers to Ansel Adams. In them, beauty was something external to be captured in each shot, a reserve where solitude was a regained innocence and open spaces offered an inexhaustible source of peacefulness for the contemplative eye under the changing light’s mantle.

Gradually, as these perspectives became advertising and marketing leitmotifs, this genre had to be reinvented and new possibilities sought elsewhere. Already in 1975, with the exhibition New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-Altered Landscape, it became clear that human intervention was inseparable from our new perception of landscape. The aseptic style of the authors gathered in this exhibition, considered almost forensic and where the emotional charge seemed absent, caused the sensation of being somehow close to a crime scene’s lingering memories, but devoid of its dramatic charge. During the following years, some authors, with a similar methodology but against this trend, looked after landscapes as representation of their own temperament, metaphor of an inner life that finds in the environment an affinity and a strong individual expressive capacity. Finally, photography assumed the same subjectivity of other means. As an example, Hiroshi Sugimoto wrote about his Seascapes: "Every time I view the sea, I feel a calming sense of security, as if visiting my ancestral home". In that phrase, anyone can guess a sort of poetic inclination and a strong artistic weight that facilitates dialogue with paintings, as was done in 2012 by exposing this series with Mark Rothko’s work.

However, Eden’s innocence became impossible in a world where human presence outreach tainted glaciers and forests with the same nonchalance. In the second half of the twentieth century, the landscape was transformed from man facing nature, to be a metaphor for our own humanity and, at the same time, scene of our fears, hopes and tragedies. We read as landscape every place where a scenario simulates an open space, no matter whether an emotional or conceptual projection of ourselves, but also we read it under the titanic action of mining, between the megalopolis’ streets or against the inventiveness of major transformation projects. Hybridization of genres has allowed the unreal calm of sensationalist scenes as in Fernando Brito’s pictures and the catastrophe of Chinese dumping sites of Yao Lu to be shown as images of bucolic appearance. We bit the fruit of our pride and today paradise is a shy promise. We need to build works, with concrete actions to transform the announced catastrophe in a redemptive epiphany. The landscape is, with its potential for imagination and denunciation, the much needed tool.

Alejandro Malo (Mexico, 1972). Lives and works in Mexico and is the director of ZoneZero. Since 1993, he has taken part in various cultural projects and worked as an information technology consultant. He has collaborated in print and electronic publications, and given workshops and conferences on literature, creative writing, storytelling and technology. In 2009, Malo joined the team of the Fundación Pedro Meyer, where he directs the Archives and Technology departments.

Alejandro Malo (Mexico, 1972). Lives and works in Mexico and is the director of ZoneZero. Since 1993, he has taken part in various cultural projects and worked as an information technology consultant. He has collaborated in print and electronic publications, and given workshops and conferences on literature, creative writing, storytelling and technology. In 2009, Malo joined the team of the Fundación Pedro Meyer, where he directs the Archives and Technology departments.Alejandro Malo

In Postproduction, I try to show that artists' intuitive relationship with art history is now going beyond what we call "the art of appropriation," which naturally infers an ideology of ownership, and moving toward a culture of the use of forms, a culture of constant activity of signs based on a collective ideal: sharing. —Nicolas Bourriaud.

Scene of the film Metropolis by Fritz Lang, 1927.

For some time now, the resource of appropriation in photography has gone from being a subversive and provocative act to being, in many cases, the catch phrase which seeks to associate the prestige of previous artworks and contexts with fresh projects. The very concept of appropriation assumes the possibility of appropriating a material aspect of an image which is becoming more and more intangible. Due to the increasing production, consumption and transformation of images in a digital format, there is now an infinite number of possible reincarnations of not only every photograph, but also of its copies and variants, and of other photographs which it references, parodies or recreates. This never-ending cascade of repetitions and similarities has rendered unnecessary any fight against the concepts of originality and authorship, which only a few decades ago, it seemed essential to question. Originality, at risk of showing itself up with touching naivety, has not evolved from being a different arrangement of very well-known elements. Similarly, authorship hardly ends up as the top hat from which, like a rabbit, a well-edited design made up of materials uploaded from almost indistinguishable references will appear. In such a scenario, what does artwork openly based on somebody else’s material suggest? What question does it raise and what answer does it provide? Or, ideally, what question would it raise and what answer would it give so as not to remain merely a superficial resource?

The first step in formulating a response is to recognize that the boundaries of this practice are imprecise. It is impossible to define the point at which the reinterpretation of archived material or their intervention turns into a practice of visual recycling and rewriting of its meaning. If we add to this catalogue of practices, collages and photo montages, as well as the found footage and the capture of three- dimensional representations (for example, Street View or Apple Maps), then the territory becomes immeasurable. However, perhaps it is this complexity itself that is the first supporting point: a project that is constructed from a remix does not conceal its debt to other sources, and instead demonstrates its aim of proposing a new interpretation of them, albeit in a modest way. This in itself highlights an ethical concern with respect to the rule of images. Here lies a commitment to not only inviting a reflective way of looking at a universe that already exists but also a desire to add meaning to this universe. This leads us to the following conclusion: a project of this kind calls for contextual boundaries to be fixed. In order to create a new meaning it is fundamental to acknowledge previous meanings and references. Whether this is achieved by means of footnotes, marginal notes or definition by the micro universe itself regarding the selection and shots it comprises, or even the sum of a variety of these resources, the result is always one step further away from the original sources.

Finally, making the effort to acknowledge the fact that an image derives from previous artwork and that it aspires to become part of a context allows us to deduce a final characteristic of these designs, a characteristic that we can call the ecology of photographic recycling. In a world in which images are created at an extraordinary pace and in which every image can be disposable, appropriation acknowledges that images can take on new meanings and be enriched by broader meanings. The unstoppable avalanche of production comes face to face with the reasoned observation of reproduction and the modest judgment of post-production. The decreasing value of originality counters analysis, and the curator’s panoramic vision opposes the author’s perspective.

If we admit that in between the practices of appropriation and remix lies a need for ethics and ecology, which themselves require individual assessment and research, perhaps we can better measure the current relevance of the latest designs and recognize the scope of each one. If we accept that this new economy of shared property adds as much economic value as it does symbolic value, perhaps we will then have more factors related to our notions about intellectual property to adjust to a more progressive framework. The questions from the photographic world - in which there is so much to see and so much to understand - are timely and certainly worth acknowledging. Are we capable of doing so?

Alejandro Malo (Mexico, 1972). Lives and works in Mexico and is the director of ZoneZero. Since 1993, he has taken part in various cultural projects and worked as an information technology consultant. He has collaborated in print and electronic publications, and given workshops and conferences on literature, creative writing, storytelling and technology. In 2009, Malo joined the team of the Fundación Pedro Meyer, where he directs the Archives and Technology departments.

Alejandro Malo (Mexico, 1972). Lives and works in Mexico and is the director of ZoneZero. Since 1993, he has taken part in various cultural projects and worked as an information technology consultant. He has collaborated in print and electronic publications, and given workshops and conferences on literature, creative writing, storytelling and technology. In 2009, Malo joined the team of the Fundación Pedro Meyer, where he directs the Archives and Technology departments.[core_state] => 1 [core_access] => 1 [core_metadata] => {"robots":"","author":"Alejandro Malo","rights":"","xreference":""} [core_created_user_id] => 838 [core_created_by_alias] => [core_created_time] => 2015-10-12 06:02:21 [core_images] => {"image_intro":"images\/categories\/apropiacion\/metropolis.gif","float_intro":"","image_intro_alt":"","image_intro_caption":"","image_fulltext":"images\/categories\/apropiacion\/metropolis.gif","float_fulltext":"","image_fulltext_alt":"","image_fulltext_caption":""} [core_modified_time] => 2016-05-19 17:00:34 [core_language] => en-GB [core_catid] => 63 [core_publish_up] => 2015-10-12 06:02:21 [core_publish_down] => 0000-00-00 00:00:00 [content_type_title] => Article [router] => ContentHelperRoute::getArticleRoute [author] => Elisa Rugo [author_email] => elisa@zonezero.com [link] => index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=331:appropriation-and-remix&catid=63&lang=en-GB [displayDate] => 2015-10-12 06:02:21 [event] => stdClass Object ( [afterDisplayTitle] => [beforeDisplayContent] => [afterDisplayContent] => ) [text] =>

In Postproduction, I try to show that artists' intuitive relationship with art history is now going beyond what we call "the art of appropriation," which naturally infers an ideology of ownership, and moving toward a culture of the use of forms, a culture of constant activity of signs based on a collective ideal: sharing. —Nicolas Bourriaud.

Scene of the film Metropolis by Fritz Lang, 1927.

For some time now, the resource of appropriation in photography has gone from being a subversive and provocative act to being, in many cases, the catch phrase which seeks to associate the prestige of previous artworks and contexts with fresh projects. The very concept of appropriation assumes the possibility of appropriating a material aspect of an image which is becoming more and more intangible. Due to the increasing production, consumption and transformation of images in a digital format, there is now an infinite number of possible reincarnations of not only every photograph, but also of its copies and variants, and of other photographs which it references, parodies or recreates. This never-ending cascade of repetitions and similarities has rendered unnecessary any fight against the concepts of originality and authorship, which only a few decades ago, it seemed essential to question. Originality, at risk of showing itself up with touching naivety, has not evolved from being a different arrangement of very well-known elements. Similarly, authorship hardly ends up as the top hat from which, like a rabbit, a well-edited design made up of materials uploaded from almost indistinguishable references will appear. In such a scenario, what does artwork openly based on somebody else’s material suggest? What question does it raise and what answer does it provide? Or, ideally, what question would it raise and what answer would it give so as not to remain merely a superficial resource?

The first step in formulating a response is to recognize that the boundaries of this practice are imprecise. It is impossible to define the point at which the reinterpretation of archived material or their intervention turns into a practice of visual recycling and rewriting of its meaning. If we add to this catalogue of practices, collages and photo montages, as well as the found footage and the capture of three- dimensional representations (for example, Street View or Apple Maps), then the territory becomes immeasurable. However, perhaps it is this complexity itself that is the first supporting point: a project that is constructed from a remix does not conceal its debt to other sources, and instead demonstrates its aim of proposing a new interpretation of them, albeit in a modest way. This in itself highlights an ethical concern with respect to the rule of images. Here lies a commitment to not only inviting a reflective way of looking at a universe that already exists but also a desire to add meaning to this universe. This leads us to the following conclusion: a project of this kind calls for contextual boundaries to be fixed. In order to create a new meaning it is fundamental to acknowledge previous meanings and references. Whether this is achieved by means of footnotes, marginal notes or definition by the micro universe itself regarding the selection and shots it comprises, or even the sum of a variety of these resources, the result is always one step further away from the original sources.

Finally, making the effort to acknowledge the fact that an image derives from previous artwork and that it aspires to become part of a context allows us to deduce a final characteristic of these designs, a characteristic that we can call the ecology of photographic recycling. In a world in which images are created at an extraordinary pace and in which every image can be disposable, appropriation acknowledges that images can take on new meanings and be enriched by broader meanings. The unstoppable avalanche of production comes face to face with the reasoned observation of reproduction and the modest judgment of post-production. The decreasing value of originality counters analysis, and the curator’s panoramic vision opposes the author’s perspective.

If we admit that in between the practices of appropriation and remix lies a need for ethics and ecology, which themselves require individual assessment and research, perhaps we can better measure the current relevance of the latest designs and recognize the scope of each one. If we accept that this new economy of shared property adds as much economic value as it does symbolic value, perhaps we will then have more factors related to our notions about intellectual property to adjust to a more progressive framework. The questions from the photographic world - in which there is so much to see and so much to understand - are timely and certainly worth acknowledging. Are we capable of doing so?

Alejandro Malo (Mexico, 1972). Lives and works in Mexico and is the director of ZoneZero. Since 1993, he has taken part in various cultural projects and worked as an information technology consultant. He has collaborated in print and electronic publications, and given workshops and conferences on literature, creative writing, storytelling and technology. In 2009, Malo joined the team of the Fundación Pedro Meyer, where he directs the Archives and Technology departments.

Alejandro Malo (Mexico, 1972). Lives and works in Mexico and is the director of ZoneZero. Since 1993, he has taken part in various cultural projects and worked as an information technology consultant. He has collaborated in print and electronic publications, and given workshops and conferences on literature, creative writing, storytelling and technology. In 2009, Malo joined the team of the Fundación Pedro Meyer, where he directs the Archives and Technology departments.[id] => 331 [language] => en-GB [catid] => 63 [jcfields] => Array ( ) ) 1

Alejandro Malo

Mexican Family, unknown author, daguerrotype, ca. 1847

Seeing presupposes distance, decisiveness which separates, the power to stay out of contact and in contact avoid confusion.

Seeing means that this separation has nevertheless become an encounter. —Maurice Blanchot.

Any representation of a community implies a perspective. Each time we observe a group we become interpreters and with each observation we make, we reveal to which communities we belong. Photography, with its ability to record, was soon considered to be a suitable tool to crystallize these observations and encourage the study of ethnicity and customs. However, being at least as susceptible to ideological bias as any other medium, it immediately revealed its colonialist burden and it is no coincidence that some of the first photographs that try to document a community were taken in company of an army or along trade routes. Images of the Mexico-American War (1846-1848) and the rebellion in India (1857), for example, show the confusion of these early records in the eyes of those portrayed and often leave us with the feeling that those photos were another kind of victory.

In the last decade of the nineteenth century, Ryuzo Torii and Edward S. Curtis introduce a way of using photography on behalf of ethnology, and Jacob Riis published How the Other Half Lives (1890). In those early photo essays on specific communities, there's a clear awareness of the otherness and a sympathetic point of view, but the perspective of the victors or the moral superiority of the observer is also legitimated. That partly naive, partly pretentious attitude of someone assuming to discover or save the others, has permeated much of photojournalism and documentary work since. Arguing a never achieved objectivity, they perpetuated asymmetrical readings and promoted a colonialism that replaced war's firepower with economy and culture. There were reasons for its existence, as an expression of a particular moment in history and a contribution to global integration, but it has been overtaken by a world whose visual center moves across the surface of the globe and where the last word has the duration of a tweet.

Soon documentalists themselves perceived the contradiction and near the beginning of the twentieth century started to explore alternatives to escape this logic: from the numerous attempts to capture the misleading truth in the style of Dziga Vertov's Kino-Pravda, through Cinema Verite, Direct Cinema, Candid Eye in film and their photographic counterparts, all the way to ethnofiction experiments, the long history of participatory documentary or the hopeful outlook of Shahidul Alam's Majority World, which proposes to let those closer to the phenomena and activities hold the camera. All are useful tools to approach the topic, but they don’t offer a final answer.

An image has the chance, as never before, to represent each ethnic, social and tribal group, whether they live in the cities or the most remote regions, and it also has the potential to do so from many different angles. The camera, already present in many devices, is in the hands of almost anyone who wants to register their community. Maybe it’s time to accept once and for all that to represent a community is not to search an objective representation or an intrinsic truth, nor trying to offer a problematic balance. However, in any case we should try to give a fair interpretation and an accurate testimony, where in many cases the sum of multiple perspectives can bring us closer to an elusive reality. This requires more critical reading and analysis from the public, compels the media to hold stronger values than empty veracity and offers the photographer a more honest path to meet the others. This change, like any change, is full of uncertainties, but ends in a space full of opportunities where the image can lead us.

Alejandro Malo (Mexico, 1972). Lives and works in Mexico and is the director of ZoneZero. Since 1993, he has taken part in various cultural projects and worked as an information technology consultant. He has collaborated in print and electronic publications, and given workshops and conferences on literature, creative writing, storytelling and technology. In 2009, Malo joined the team of the Fundación Pedro Meyer, where he directs the Archives and Technology departments.

Alejandro Malo (Mexico, 1972). Lives and works in Mexico and is the director of ZoneZero. Since 1993, he has taken part in various cultural projects and worked as an information technology consultant. He has collaborated in print and electronic publications, and given workshops and conferences on literature, creative writing, storytelling and technology. In 2009, Malo joined the team of the Fundación Pedro Meyer, where he directs the Archives and Technology departments.

Mexican Family, unknown author, daguerrotype, ca. 1847

Seeing presupposes distance, decisiveness which separates, the power to stay out of contact and in contact avoid confusion.

Seeing means that this separation has nevertheless become an encounter. —Maurice Blanchot.

Any representation of a community implies a perspective. Each time we observe a group we become interpreters and with each observation we make, we reveal to which communities we belong. Photography, with its ability to record, was soon considered to be a suitable tool to crystallize these observations and encourage the study of ethnicity and customs. However, being at least as susceptible to ideological bias as any other medium, it immediately revealed its colonialist burden and it is no coincidence that some of the first photographs that try to document a community were taken in company of an army or along trade routes. Images of the Mexico-American War (1846-1848) and the rebellion in India (1857), for example, show the confusion of these early records in the eyes of those portrayed and often leave us with the feeling that those photos were another kind of victory.

In the last decade of the nineteenth century, Ryuzo Torii and Edward S. Curtis introduce a way of using photography on behalf of ethnology, and Jacob Riis published How the Other Half Lives (1890). In those early photo essays on specific communities, there's a clear awareness of the otherness and a sympathetic point of view, but the perspective of the victors or the moral superiority of the observer is also legitimated. That partly naive, partly pretentious attitude of someone assuming to discover or save the others, has permeated much of photojournalism and documentary work since. Arguing a never achieved objectivity, they perpetuated asymmetrical readings and promoted a colonialism that replaced war's firepower with economy and culture. There were reasons for its existence, as an expression of a particular moment in history and a contribution to global integration, but it has been overtaken by a world whose visual center moves across the surface of the globe and where the last word has the duration of a tweet.

Soon documentalists themselves perceived the contradiction and near the beginning of the twentieth century started to explore alternatives to escape this logic: from the numerous attempts to capture the misleading truth in the style of Dziga Vertov's Kino-Pravda, through Cinema Verite, Direct Cinema, Candid Eye in film and their photographic counterparts, all the way to ethnofiction experiments, the long history of participatory documentary or the hopeful outlook of Shahidul Alam's Majority World, which proposes to let those closer to the phenomena and activities hold the camera. All are useful tools to approach the topic, but they don’t offer a final answer.

An image has the chance, as never before, to represent each ethnic, social and tribal group, whether they live in the cities or the most remote regions, and it also has the potential to do so from many different angles. The camera, already present in many devices, is in the hands of almost anyone who wants to register their community. Maybe it’s time to accept once and for all that to represent a community is not to search an objective representation or an intrinsic truth, nor trying to offer a problematic balance. However, in any case we should try to give a fair interpretation and an accurate testimony, where in many cases the sum of multiple perspectives can bring us closer to an elusive reality. This requires more critical reading and analysis from the public, compels the media to hold stronger values than empty veracity and offers the photographer a more honest path to meet the others. This change, like any change, is full of uncertainties, but ends in a space full of opportunities where the image can lead us.

Alejandro Malo (Mexico, 1972). Lives and works in Mexico and is the director of ZoneZero. Since 1993, he has taken part in various cultural projects and worked as an information technology consultant. He has collaborated in print and electronic publications, and given workshops and conferences on literature, creative writing, storytelling and technology. In 2009, Malo joined the team of the Fundación Pedro Meyer, where he directs the Archives and Technology departments.

Alejandro Malo (Mexico, 1972). Lives and works in Mexico and is the director of ZoneZero. Since 1993, he has taken part in various cultural projects and worked as an information technology consultant. He has collaborated in print and electronic publications, and given workshops and conferences on literature, creative writing, storytelling and technology. In 2009, Malo joined the team of the Fundación Pedro Meyer, where he directs the Archives and Technology departments.Alejandro Malo

by Eadweard Muybridge

The fleeting today is tenuous and eternal;

Don’t wait for another Heaven or Hell.

—Jorge Luis Borges.

Photography is thought of as a way to freeze time and people rarely discuss how much time each photographic instant really represents. From the more than eight hours taken to shoot View from the Window at Le Gras to the fifteen minutes for Boulevard du Temple, to the speeds achieved in the past decade of more than a billion frames per second, each photograph prolongs a fiction in which we desire to see the ever-changing world imprisoned before our gaze. Movies, like theater and dance, derived from photographs precisely their desire to represent this same ever-changing world, but without being confined to an instant or synthesizing something living into a fixed image. The work of Muybridge and Marey, by capturing sequential movement and reproducing it in fixed or animated images, addressed these aspects which appeared to draw one path for photography and another for cinematography.

Decades later, communication vessels became popular, blurring the boundaries between these mediums. Photographic time extends itself in anyone’s hands and an image, previously immobile, unfolds instantly into movement with any number of applications such as Vine, Instagram, Cinemagram and others. With increasing frequency, photographers offer video work as part of their professional activities and create time-lapse or rephotography images to convey events that extend beyond the limits of a series or a single shot. Likewise, movies have shifted from the surprise occasioned by works like Chris Marker’s La Jetée (1962) and the flat sequences of Antonioni that scandalized Cannes in 1960 to a visual fascination with suspended, almost immobile shots, as in the Tarkovsky movies. Current cinematography often employs flat sequence structure, or imitates Ken Burns by recovering photographic files through a specific video editing effect named after him.

Tonino Guerra, in the preface to Instant Light: Tarkovsky Polaroids, anecdotes about how both Tarkovsky and Antonioni used Polaroid cameras in the late 1970s. The former was constantly worried about the volatility of time and his desire to freeze it in these instant images; it is not difficult to imagine how this impacted his movies. The latter discusses how, during a location scouting trip to Uzbekistan, an old man rejected a photograph recently take of him and two friends by asking: "¿“Why stop time?” to which neither man could respond. And this invites the questions: If photography is a way to stop time, how much time and how much mobility can an instant comprise? And no less important, how much do movies actually escape from their photographic desire to stop time, even though it captures entire lifetimes or historic moments?

The first question has been tested in a number of projects, and the opportunity to represent the variability of time has multiplied with the immediacy of available tools. The visual language permitted by cameras has led to the proliferation of works where years become a chronograph, days are the sun’s accelerated journey across the horizon, people are frozen in 360 degrees and cameras slow down or speed up at the pace of a silent film. Movies have their own experimental territory where more frequent use of the flat sequence and found footage, real or fictitious, and the recording and recovery of material in lapses is increasingly prolonged. The bridge between what was considered a brief, decisive instant and what was considered a long, narrative instant is constantly lengthening. The fields of photography and film are more accessible, and the instant, more relative. This freedom is worth exploring.

Alejandro Malo (Mexico, 1972). Lives and works in Mexico and is the director of ZoneZero. Since 1993, he has taken part in various cultural projects and worked as an information technology consultant. He has collaborated in print and electronic publications, and given workshops and conferences on literature, creative writing, storytelling and technology. In 2009, Malo joined the team of the Fundación Pedro Meyer, where he directs the Archives and Technology departments.

Alejandro Malo (Mexico, 1972). Lives and works in Mexico and is the director of ZoneZero. Since 1993, he has taken part in various cultural projects and worked as an information technology consultant. He has collaborated in print and electronic publications, and given workshops and conferences on literature, creative writing, storytelling and technology. In 2009, Malo joined the team of the Fundación Pedro Meyer, where he directs the Archives and Technology departments.[core_state] => 1 [core_access] => 1 [core_metadata] => {"robots":"","author":"Alejandro Malo","rights":"","xreference":""} [core_created_user_id] => 841 [core_created_by_alias] => [core_created_time] => 2015-02-18 20:11:20 [core_images] => {"image_intro":"images\/categories\/temporality\/Muybridge_race_horse_animated.gif","float_intro":"","image_intro_alt":"","image_intro_caption":"","image_fulltext":"images\/categories\/temporality\/Muybridge_race_horse_animated.gif","float_fulltext":"","image_fulltext_alt":"","image_fulltext_caption":""} [core_modified_time] => 2015-06-01 18:12:34 [core_language] => en-GB [core_catid] => 57 [core_publish_up] => 2015-02-18 20:11:20 [core_publish_down] => 0000-00-00 00:00:00 [content_type_title] => Article [router] => ContentHelperRoute::getArticleRoute [author] => [author_email] => [link] => index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=257:the-many-moments-of-the-instant&catid=57&lang=en-GB [displayDate] => 2015-02-18 20:11:20 [event] => stdClass Object ( [afterDisplayTitle] => [beforeDisplayContent] => [afterDisplayContent] => ) [text] =>

by Eadweard Muybridge

The fleeting today is tenuous and eternal;

Don’t wait for another Heaven or Hell.

—Jorge Luis Borges.

Photography is thought of as a way to freeze time and people rarely discuss how much time each photographic instant really represents. From the more than eight hours taken to shoot View from the Window at Le Gras to the fifteen minutes for Boulevard du Temple, to the speeds achieved in the past decade of more than a billion frames per second, each photograph prolongs a fiction in which we desire to see the ever-changing world imprisoned before our gaze. Movies, like theater and dance, derived from photographs precisely their desire to represent this same ever-changing world, but without being confined to an instant or synthesizing something living into a fixed image. The work of Muybridge and Marey, by capturing sequential movement and reproducing it in fixed or animated images, addressed these aspects which appeared to draw one path for photography and another for cinematography.

Decades later, communication vessels became popular, blurring the boundaries between these mediums. Photographic time extends itself in anyone’s hands and an image, previously immobile, unfolds instantly into movement with any number of applications such as Vine, Instagram, Cinemagram and others. With increasing frequency, photographers offer video work as part of their professional activities and create time-lapse or rephotography images to convey events that extend beyond the limits of a series or a single shot. Likewise, movies have shifted from the surprise occasioned by works like Chris Marker’s La Jetée (1962) and the flat sequences of Antonioni that scandalized Cannes in 1960 to a visual fascination with suspended, almost immobile shots, as in the Tarkovsky movies. Current cinematography often employs flat sequence structure, or imitates Ken Burns by recovering photographic files through a specific video editing effect named after him.

Tonino Guerra, in the preface to Instant Light: Tarkovsky Polaroids, anecdotes about how both Tarkovsky and Antonioni used Polaroid cameras in the late 1970s. The former was constantly worried about the volatility of time and his desire to freeze it in these instant images; it is not difficult to imagine how this impacted his movies. The latter discusses how, during a location scouting trip to Uzbekistan, an old man rejected a photograph recently take of him and two friends by asking: "¿“Why stop time?” to which neither man could respond. And this invites the questions: If photography is a way to stop time, how much time and how much mobility can an instant comprise? And no less important, how much do movies actually escape from their photographic desire to stop time, even though it captures entire lifetimes or historic moments?

The first question has been tested in a number of projects, and the opportunity to represent the variability of time has multiplied with the immediacy of available tools. The visual language permitted by cameras has led to the proliferation of works where years become a chronograph, days are the sun’s accelerated journey across the horizon, people are frozen in 360 degrees and cameras slow down or speed up at the pace of a silent film. Movies have their own experimental territory where more frequent use of the flat sequence and found footage, real or fictitious, and the recording and recovery of material in lapses is increasingly prolonged. The bridge between what was considered a brief, decisive instant and what was considered a long, narrative instant is constantly lengthening. The fields of photography and film are more accessible, and the instant, more relative. This freedom is worth exploring.

Alejandro Malo (Mexico, 1972). Lives and works in Mexico and is the director of ZoneZero. Since 1993, he has taken part in various cultural projects and worked as an information technology consultant. He has collaborated in print and electronic publications, and given workshops and conferences on literature, creative writing, storytelling and technology. In 2009, Malo joined the team of the Fundación Pedro Meyer, where he directs the Archives and Technology departments.

Alejandro Malo (Mexico, 1972). Lives and works in Mexico and is the director of ZoneZero. Since 1993, he has taken part in various cultural projects and worked as an information technology consultant. He has collaborated in print and electronic publications, and given workshops and conferences on literature, creative writing, storytelling and technology. In 2009, Malo joined the team of the Fundación Pedro Meyer, where he directs the Archives and Technology departments.[id] => 257 [language] => en-GB [catid] => 57 [jcfields] => Array ( ) ) 1

Alejandro Malo

The Devil in New York. 1985. Pedro Meyer

In 2013, just over one billion smart phones came onto the international market, while only a little over sixty million digital cameras sold. Thanks to this push, the number of cameras sold as part of mobile devices will be greater than the number of people inhabiting the planet, which accentuates the visual avalanche we now face. Creating photographic images has become as trivial as chatting on the phone and their meaning, 2,000 millones de nuevasimágenes as they are uploaded and shared online every day is reduced, in many cases, to anecdotal scenes that are incomprehensible to strangers. In the face of this extensive iconographic universe, content runs the risk of being lost, of being confused amidst stylistic similarities, of sinking unceremoniously into the cracks of global networks; and one of the few useful tools for strengthening photographic discourse and emphasizing a relevant visual message is narrative.

Four years ago, in 2010, when ZoneZero's position within the ecosystem of projects at the Pedro Meyer Foundation was only just beginning to be defined, World Press Photo contacted us. They had interviewed a number of people and institutions from the field of photography in Mexico and were looking to define alternative forms of collaboration. Their goal was to develop an educational program designed for photojournalists. Our first exchanges created several points of tension, but each debate served to consolidate points of agreement. These points grew from reflections that are still meaningful today.

The first was a diagnosis that was already evident at that point: the traditional role of photography could not continue unchanged in an environment where the sources of photographic material were multiplied at an unattainable pace. Capturing the exact photograph of an event had become a game of chance that could be won by anyone in possession of a mobile device. Originality paled in the face of quantity and mastery of technique dissipated with each technological advance. The very boundaries of photography we being blurred: the place for photography within interactive media, video, electronic books, websites and more, the relationship between these and other media, the frontier of the curatorial and author-oriented, all became territory for exploration. At that moment we chose to broach the concept of New Media, to emphasize our willingness to experiment with the sum of diverse technological resources, and for lack of another label with the same amount of breadth and flexibility for what we wanted to achieve.

The second reflection identified which tool could be useful both for photojournalists and the wider public that was already engaging in the educational activities at the Pedro Meyer Foundation and adhered to ZoneZero content. The choice was clear and conclusive: storytelling. After being translated, the term was replaced with a new one, photo-narrative, to highlight the photographic component. Pedro Meyer’s story I Photograph to Remember with one of the cornerstones of Digital Storytelling, and his position that everything before a photographer tells a story, were influential in this choice. Nevertheless, it was equally or more important to consider that in an era where images and information are as abundant and immediate as they are now, context is the only thing that distinguishes them from background noise. Every image, in order to be more than ornamental, invites the viewer to interpret a meaning, to head in some direction, to guess the story and imagine the consequences of what it represents. Every memorable photo tells a story, whether in the tension of the elements it depicts, or in how it has been edited, or with the help of accompanying information. Whether it is a single photo, a series, images in movement or interactive formats, an image aspires to be coherent, to suggest a before and an after, to propose or explain change. We are not the same after the party or the childhood accident documented by the photograph, nor after national disaster or glory.

Today, after a number of years collaborating with World Press Photo, three editions of Diplomado de Fotonarrativa y Nuevos Medios and a plethora of technological changes that could only have been imagined, photo-narrative is even more important. During this time we have learned and changed. Our ideas about photography and narrative continue to change. World Press Photo now has multimedia categories that include long feature, short feature and interactive documentary. Photo-narrative’s effectiveness means that it has been used in a number of different fields. Because of this, it is also our task to explore and exhibit examples that, as with other issues, foster dialogue and reflection. Every one of us is the sum of our personal, familiar, collective and even fictional stories. Being understood and understanding one another begins with knowing how to tell these stories.

Alejandro Malo (Mexico, 1972). Lives and works in Mexico and is the director of ZoneZero. Since 1993, he has taken part in various cultural projects and worked as an information technology consultant. He has collaborated in print and electronic publications, and given workshops and conferences on literature, creative writing, storytelling and technology. In 2009, Malo joined the team of the Fundación Pedro Meyer, where he directs the Archives and Technology departments.

Alejandro Malo (Mexico, 1972). Lives and works in Mexico and is the director of ZoneZero. Since 1993, he has taken part in various cultural projects and worked as an information technology consultant. He has collaborated in print and electronic publications, and given workshops and conferences on literature, creative writing, storytelling and technology. In 2009, Malo joined the team of the Fundación Pedro Meyer, where he directs the Archives and Technology departments.

The Devil in New York. 1985. Pedro Meyer

In 2013, just over one billion smart phones came onto the international market, while only a little over sixty million digital cameras sold. Thanks to this push, the number of cameras sold as part of mobile devices will be greater than the number of people inhabiting the planet, which accentuates the visual avalanche we now face. Creating photographic images has become as trivial as chatting on the phone and their meaning, 2,000 millones de nuevasimágenes as they are uploaded and shared online every day is reduced, in many cases, to anecdotal scenes that are incomprehensible to strangers. In the face of this extensive iconographic universe, content runs the risk of being lost, of being confused amidst stylistic similarities, of sinking unceremoniously into the cracks of global networks; and one of the few useful tools for strengthening photographic discourse and emphasizing a relevant visual message is narrative.

Four years ago, in 2010, when ZoneZero's position within the ecosystem of projects at the Pedro Meyer Foundation was only just beginning to be defined, World Press Photo contacted us. They had interviewed a number of people and institutions from the field of photography in Mexico and were looking to define alternative forms of collaboration. Their goal was to develop an educational program designed for photojournalists. Our first exchanges created several points of tension, but each debate served to consolidate points of agreement. These points grew from reflections that are still meaningful today.

The first was a diagnosis that was already evident at that point: the traditional role of photography could not continue unchanged in an environment where the sources of photographic material were multiplied at an unattainable pace. Capturing the exact photograph of an event had become a game of chance that could be won by anyone in possession of a mobile device. Originality paled in the face of quantity and mastery of technique dissipated with each technological advance. The very boundaries of photography we being blurred: the place for photography within interactive media, video, electronic books, websites and more, the relationship between these and other media, the frontier of the curatorial and author-oriented, all became territory for exploration. At that moment we chose to broach the concept of New Media, to emphasize our willingness to experiment with the sum of diverse technological resources, and for lack of another label with the same amount of breadth and flexibility for what we wanted to achieve.

The second reflection identified which tool could be useful both for photojournalists and the wider public that was already engaging in the educational activities at the Pedro Meyer Foundation and adhered to ZoneZero content. The choice was clear and conclusive: storytelling. After being translated, the term was replaced with a new one, photo-narrative, to highlight the photographic component. Pedro Meyer’s story I Photograph to Remember with one of the cornerstones of Digital Storytelling, and his position that everything before a photographer tells a story, were influential in this choice. Nevertheless, it was equally or more important to consider that in an era where images and information are as abundant and immediate as they are now, context is the only thing that distinguishes them from background noise. Every image, in order to be more than ornamental, invites the viewer to interpret a meaning, to head in some direction, to guess the story and imagine the consequences of what it represents. Every memorable photo tells a story, whether in the tension of the elements it depicts, or in how it has been edited, or with the help of accompanying information. Whether it is a single photo, a series, images in movement or interactive formats, an image aspires to be coherent, to suggest a before and an after, to propose or explain change. We are not the same after the party or the childhood accident documented by the photograph, nor after national disaster or glory.

Today, after a number of years collaborating with World Press Photo, three editions of Diplomado de Fotonarrativa y Nuevos Medios and a plethora of technological changes that could only have been imagined, photo-narrative is even more important. During this time we have learned and changed. Our ideas about photography and narrative continue to change. World Press Photo now has multimedia categories that include long feature, short feature and interactive documentary. Photo-narrative’s effectiveness means that it has been used in a number of different fields. Because of this, it is also our task to explore and exhibit examples that, as with other issues, foster dialogue and reflection. Every one of us is the sum of our personal, familiar, collective and even fictional stories. Being understood and understanding one another begins with knowing how to tell these stories.

Alejandro Malo (Mexico, 1972). Lives and works in Mexico and is the director of ZoneZero. Since 1993, he has taken part in various cultural projects and worked as an information technology consultant. He has collaborated in print and electronic publications, and given workshops and conferences on literature, creative writing, storytelling and technology. In 2009, Malo joined the team of the Fundación Pedro Meyer, where he directs the Archives and Technology departments.

Alejandro Malo (Mexico, 1972). Lives and works in Mexico and is the director of ZoneZero. Since 1993, he has taken part in various cultural projects and worked as an information technology consultant. He has collaborated in print and electronic publications, and given workshops and conferences on literature, creative writing, storytelling and technology. In 2009, Malo joined the team of the Fundación Pedro Meyer, where he directs the Archives and Technology departments.Alejandro Malo

Hiawatha Playfield wading pool, 1912. Don Sherwood Parks History Collection (Record Series 5801-01), Seattle Municipal Archives.

Until a few centuries ago, one’s own image, clear and individual, was an experience many people could only achieve when they gazed at a mirror of water. It is no coincidence that, while Balzac and Dickens were recovering all types of characters from anonymity, technology made mirrors affordable and photography emerged from laboratories. The need arose to recognize one’s self. Suddenly, presenting one’s self and surviving in an image was available to more people, as demonstrated by the business cards popularized by Disdéri in France and Victorian post-mortem photography.

Nonetheless, the concept of identity was gradually constructed and consolidated throughout the 20th century, from various fronts, accompanied by photography. Identity documents and passports, the evolution of cameras, the growing visual recognition and recording of minorities all led to the current possibility of determining for ourselves not so much who we are, but how we wish to be seen. A few years ago, students were typically asked: what do you want to be when you grow up? Today, with photography linked to social networks, many young persons are constantly reporting who they are, and do not have to wait for an uncertain definitive vision of themselves, which technology makes impossible. More and more people, in response to an environment that is changing at breakneck speed, must repeatedly adapt to an identity that assumes the shape of its opportunities, and benefits as much as possible from its learning capacity.

Where there is life, identity cannot be carved in stone. It has now become liquid and we will have increasing opportunities and challenges to guide its flow. Confronted with the risk of our own face slipping out of our hands in the immense torrent of memes, filters and recreations that enable the digital world and facilitate social networks, it is important to know how other persons have channeled their means of depicting themselves. There is an inexhaustible ocean of images for this topic, from which we have selected a small sample that enable us to explore this horizon. This phenomenon, and its most recent evolution, is such a vast sphere that it is barely possible to scratch the surface, but we wish to share this journey with you.

Alejandro Malo (Mexico, 1972). Lives and works in Mexico and is the director of ZoneZero. Since 1993, he has taken part in various cultural projects and worked as an information technology consultant. He has collaborated in print and electronic publications, and given workshops and conferences on literature, creative writing, storytelling and technology. In 2009, Malo joined the team of the Fundación Pedro Meyer, where he directs the Archives and Technology departments.

Alejandro Malo (Mexico, 1972). Lives and works in Mexico and is the director of ZoneZero. Since 1993, he has taken part in various cultural projects and worked as an information technology consultant. He has collaborated in print and electronic publications, and given workshops and conferences on literature, creative writing, storytelling and technology. In 2009, Malo joined the team of the Fundación Pedro Meyer, where he directs the Archives and Technology departments.

Hiawatha Playfield wading pool, 1912. Don Sherwood Parks History Collection (Record Series 5801-01), Seattle Municipal Archives.

Until a few centuries ago, one’s own image, clear and individual, was an experience many people could only achieve when they gazed at a mirror of water. It is no coincidence that, while Balzac and Dickens were recovering all types of characters from anonymity, technology made mirrors affordable and photography emerged from laboratories. The need arose to recognize one’s self. Suddenly, presenting one’s self and surviving in an image was available to more people, as demonstrated by the business cards popularized by Disdéri in France and Victorian post-mortem photography.

Nonetheless, the concept of identity was gradually constructed and consolidated throughout the 20th century, from various fronts, accompanied by photography. Identity documents and passports, the evolution of cameras, the growing visual recognition and recording of minorities all led to the current possibility of determining for ourselves not so much who we are, but how we wish to be seen. A few years ago, students were typically asked: what do you want to be when you grow up? Today, with photography linked to social networks, many young persons are constantly reporting who they are, and do not have to wait for an uncertain definitive vision of themselves, which technology makes impossible. More and more people, in response to an environment that is changing at breakneck speed, must repeatedly adapt to an identity that assumes the shape of its opportunities, and benefits as much as possible from its learning capacity.

Where there is life, identity cannot be carved in stone. It has now become liquid and we will have increasing opportunities and challenges to guide its flow. Confronted with the risk of our own face slipping out of our hands in the immense torrent of memes, filters and recreations that enable the digital world and facilitate social networks, it is important to know how other persons have channeled their means of depicting themselves. There is an inexhaustible ocean of images for this topic, from which we have selected a small sample that enable us to explore this horizon. This phenomenon, and its most recent evolution, is such a vast sphere that it is barely possible to scratch the surface, but we wish to share this journey with you.

Alejandro Malo (Mexico, 1972). Lives and works in Mexico and is the director of ZoneZero. Since 1993, he has taken part in various cultural projects and worked as an information technology consultant. He has collaborated in print and electronic publications, and given workshops and conferences on literature, creative writing, storytelling and technology. In 2009, Malo joined the team of the Fundación Pedro Meyer, where he directs the Archives and Technology departments.

Alejandro Malo (Mexico, 1972). Lives and works in Mexico and is the director of ZoneZero. Since 1993, he has taken part in various cultural projects and worked as an information technology consultant. He has collaborated in print and electronic publications, and given workshops and conferences on literature, creative writing, storytelling and technology. In 2009, Malo joined the team of the Fundación Pedro Meyer, where he directs the Archives and Technology departments.Alejandro Malo

Photo: Pedro Meyer, 1985

Alejandro Malo (Mexico, 1972). Lives and works in Mexico and is the director of ZoneZero. Since 1993, he has taken part in various cultural projects and worked as an information technology consultant. He has collaborated in print and electronic publications, and given workshops and conferences on literature, creative writing, storytelling and technology. In 2009, Malo joined the team of the Fundación Pedro Meyer, where he directs the Archives and Technology departments.

Alejandro Malo (Mexico, 1972). Lives and works in Mexico and is the director of ZoneZero. Since 1993, he has taken part in various cultural projects and worked as an information technology consultant. He has collaborated in print and electronic publications, and given workshops and conferences on literature, creative writing, storytelling and technology. In 2009, Malo joined the team of the Fundación Pedro Meyer, where he directs the Archives and Technology departments.

Photo: Pedro Meyer, 1985

Alejandro Malo (Mexico, 1972). Lives and works in Mexico and is the director of ZoneZero. Since 1993, he has taken part in various cultural projects and worked as an information technology consultant. He has collaborated in print and electronic publications, and given workshops and conferences on literature, creative writing, storytelling and technology. In 2009, Malo joined the team of the Fundación Pedro Meyer, where he directs the Archives and Technology departments.

Alejandro Malo (Mexico, 1972). Lives and works in Mexico and is the director of ZoneZero. Since 1993, he has taken part in various cultural projects and worked as an information technology consultant. He has collaborated in print and electronic publications, and given workshops and conferences on literature, creative writing, storytelling and technology. In 2009, Malo joined the team of the Fundación Pedro Meyer, where he directs the Archives and Technology departments.