Diego Goldberg

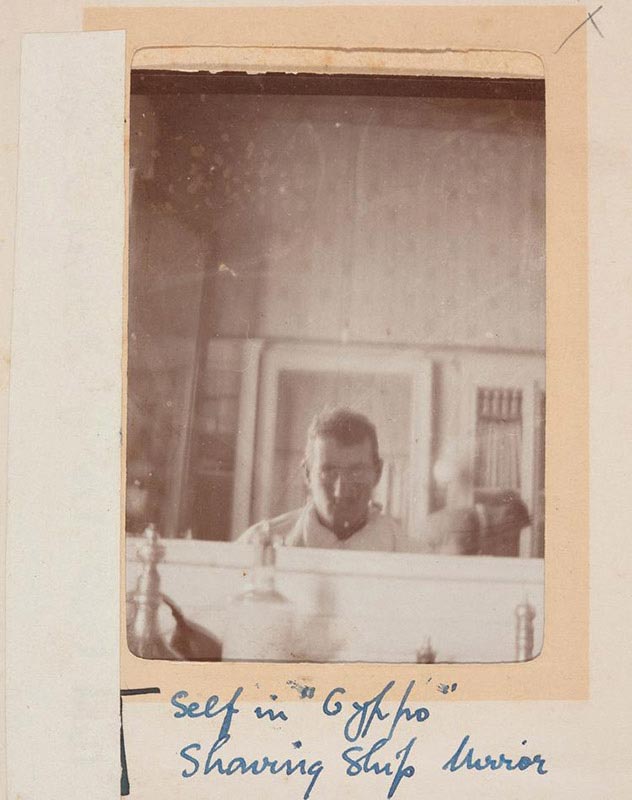

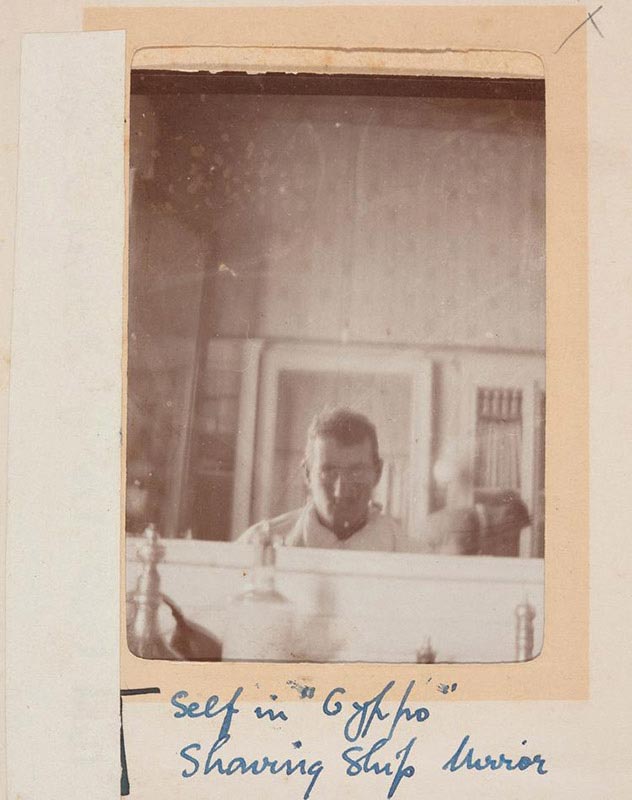

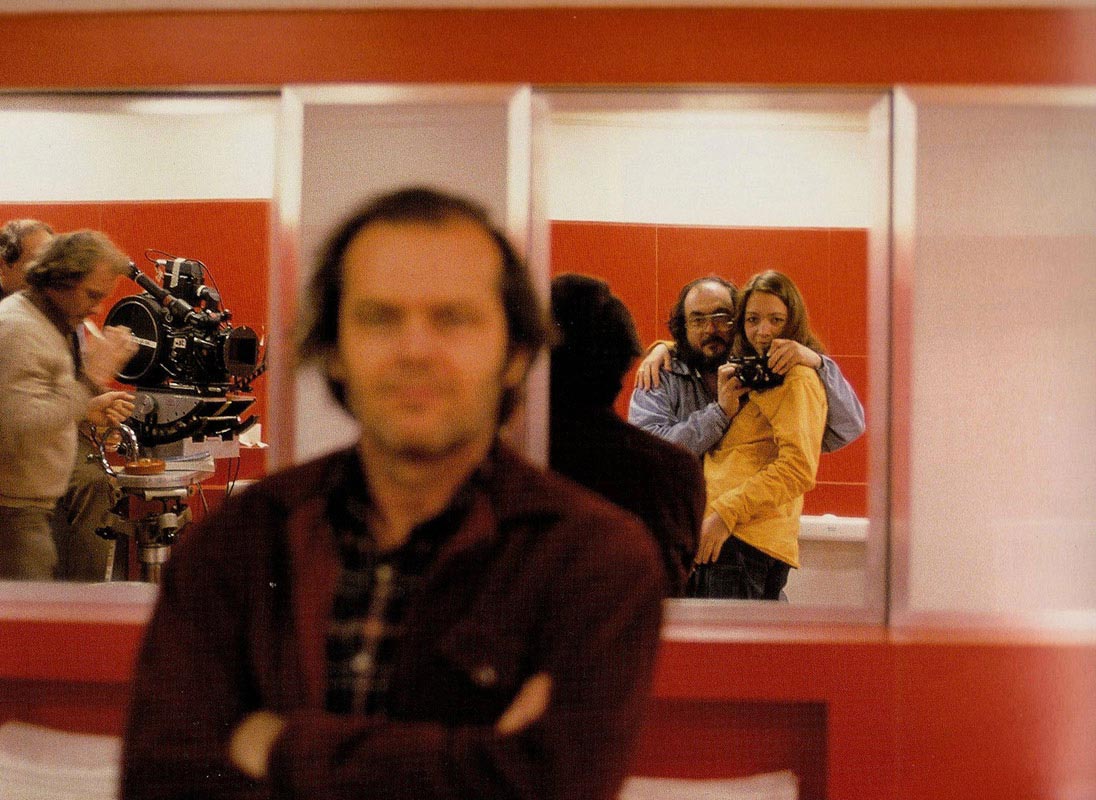

On June 17th, every year, the family goes through a private ritual:

we photograph ourselves to stop, for a fleeting moment, the arrow of time passing by.

Diego Goldberg (Argentina, 1946). Lives and works in Argentina. He has taken part in group and solo exhibitions. Among other distinctions, Goldberg has won the Gold Medal 1998 from the Society of Publications Design; the Award of Merit 1998 from the Art Directors Club of New York for The Arrow of Time; second prize at the World Press Photo (Amsterdam, 1983) for Chile Ten Years After the Coup; and First Prize in the New York Press Award 1981 for Alphonse D’Amato, commissioned by the New York Times Magazine. He also won the FNPI (Gabriel García Márquez Foundation) Prize in 2006 for the Pursuing a dream. Diego can be reached at: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. and you can visit his website.

Diego Goldberg (Argentina, 1946). Lives and works in Argentina. He has taken part in group and solo exhibitions. Among other distinctions, Goldberg has won the Gold Medal 1998 from the Society of Publications Design; the Award of Merit 1998 from the Art Directors Club of New York for The Arrow of Time; second prize at the World Press Photo (Amsterdam, 1983) for Chile Ten Years After the Coup; and First Prize in the New York Press Award 1981 for Alphonse D’Amato, commissioned by the New York Times Magazine. He also won the FNPI (Gabriel García Márquez Foundation) Prize in 2006 for the Pursuing a dream. Diego can be reached at: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. and you can visit his website.

On June 17th, every year, the family goes through a private ritual:

we photograph ourselves to stop, for a fleeting moment, the arrow of time passing by.

Diego Goldberg (Argentina, 1946). Lives and works in Argentina. He has taken part in group and solo exhibitions. Among other distinctions, Goldberg has won the Gold Medal 1998 from the Society of Publications Design; the Award of Merit 1998 from the Art Directors Club of New York for The Arrow of Time; second prize at the World Press Photo (Amsterdam, 1983) for Chile Ten Years After the Coup; and First Prize in the New York Press Award 1981 for Alphonse D’Amato, commissioned by the New York Times Magazine. He also won the FNPI (Gabriel García Márquez Foundation) Prize in 2006 for the Pursuing a dream. Diego can be reached at: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. and you can visit his website.

Diego Goldberg (Argentina, 1946). Lives and works in Argentina. He has taken part in group and solo exhibitions. Among other distinctions, Goldberg has won the Gold Medal 1998 from the Society of Publications Design; the Award of Merit 1998 from the Art Directors Club of New York for The Arrow of Time; second prize at the World Press Photo (Amsterdam, 1983) for Chile Ten Years After the Coup; and First Prize in the New York Press Award 1981 for Alphonse D’Amato, commissioned by the New York Times Magazine. He also won the FNPI (Gabriel García Márquez Foundation) Prize in 2006 for the Pursuing a dream. Diego can be reached at: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. and you can visit his website.

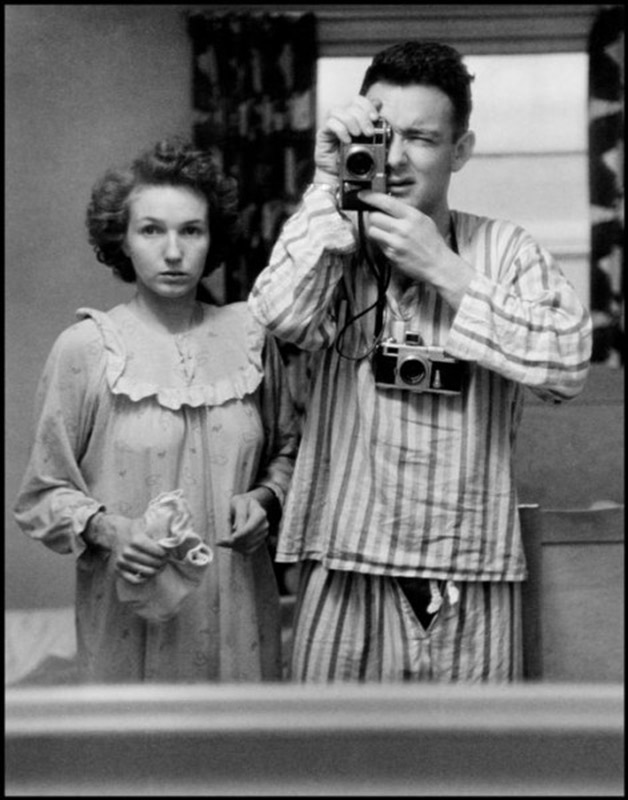

Noah Kalina

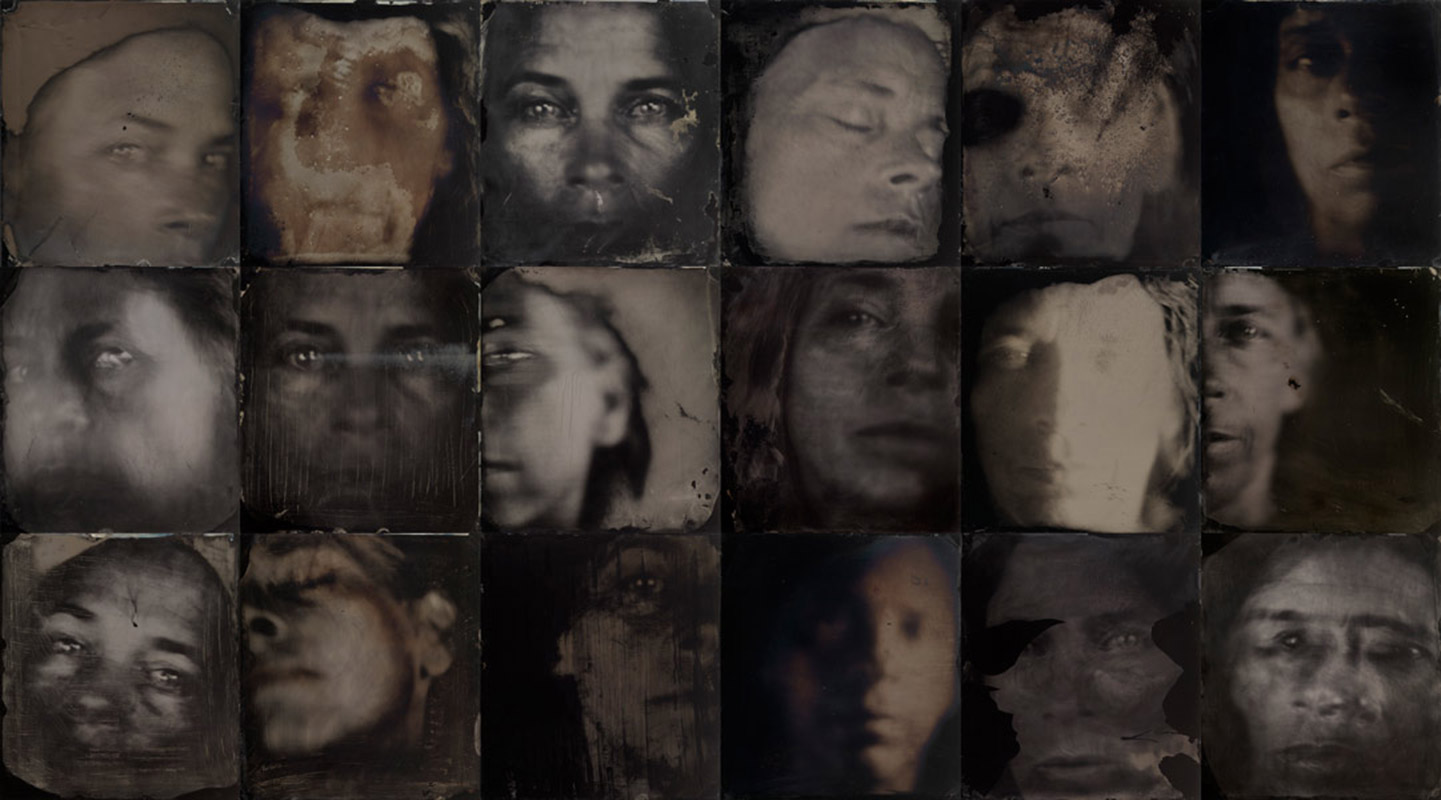

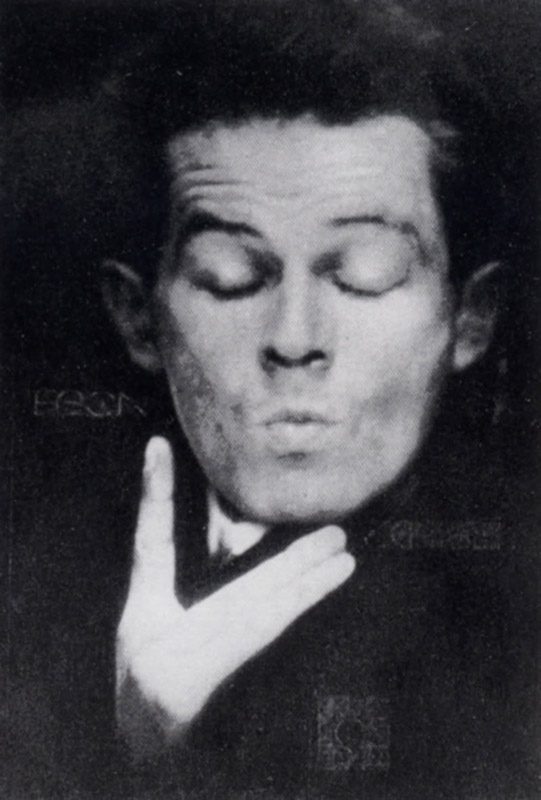

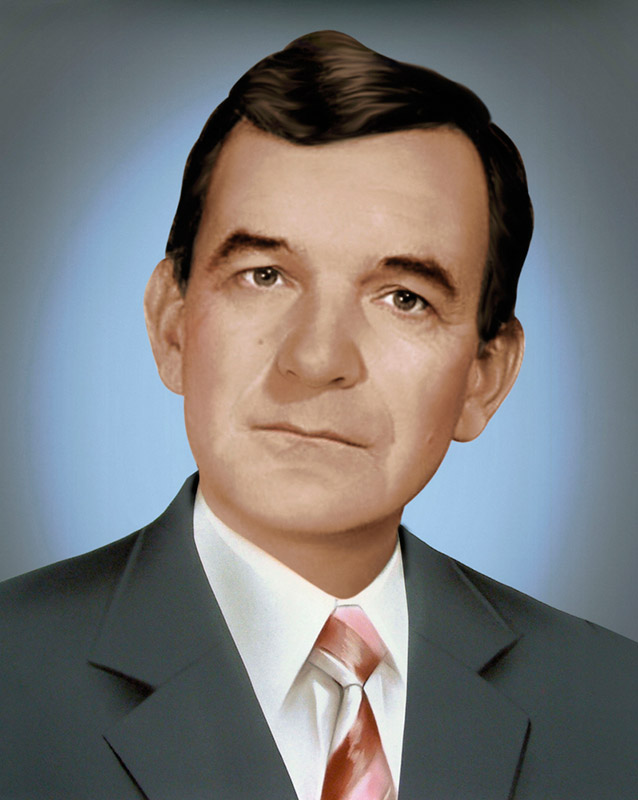

Noah Kalina has been taking a photograph of himself every day since January 2000. Originally it was meant to be a photo project, but in 2006 he was inspired by a project by Ahree Lee, a graphic designer from California who had put a time-lapse video of herself on YouTube. Noah decided to do the same with his self-portraits and, within three weeks, it became an international internet sensation.

Noah Kalina (US, 1980) is a photographer based in Brooklyn and Lumberland, New York. He graduated from the School of Visual Arts with a BFA in photography. His project ‘Everyday’ was a worldwide hit. His work has been exhibited all over the world: in the U.S., Switzerland, Italy, Belgium, France, Australia, England, Canada, Germany and the Netherlands. He also has given lectures in various countries. To see more of his work go to: noahkalina.com

Noah Kalina (US, 1980) is a photographer based in Brooklyn and Lumberland, New York. He graduated from the School of Visual Arts with a BFA in photography. His project ‘Everyday’ was a worldwide hit. His work has been exhibited all over the world: in the U.S., Switzerland, Italy, Belgium, France, Australia, England, Canada, Germany and the Netherlands. He also has given lectures in various countries. To see more of his work go to: noahkalina.comNoah Kalina has been taking a photograph of himself every day since January 2000. Originally it was meant to be a photo project, but in 2006 he was inspired by a project by Ahree Lee, a graphic designer from California who had put a time-lapse video of herself on YouTube. Noah decided to do the same with his self-portraits and, within three weeks, it became an international internet sensation.

Noah Kalina (US, 1980) is a photographer based in Brooklyn and Lumberland, New York. He graduated from the School of Visual Arts with a BFA in photography. His project ‘Everyday’ was a worldwide hit. His work has been exhibited all over the world: in the U.S., Switzerland, Italy, Belgium, France, Australia, England, Canada, Germany and the Netherlands. He also has given lectures in various countries. To see more of his work go to: noahkalina.com

Noah Kalina (US, 1980) is a photographer based in Brooklyn and Lumberland, New York. He graduated from the School of Visual Arts with a BFA in photography. His project ‘Everyday’ was a worldwide hit. His work has been exhibited all over the world: in the U.S., Switzerland, Italy, Belgium, France, Australia, England, Canada, Germany and the Netherlands. He also has given lectures in various countries. To see more of his work go to: noahkalina.comBahbak Hashemi-Nezhad

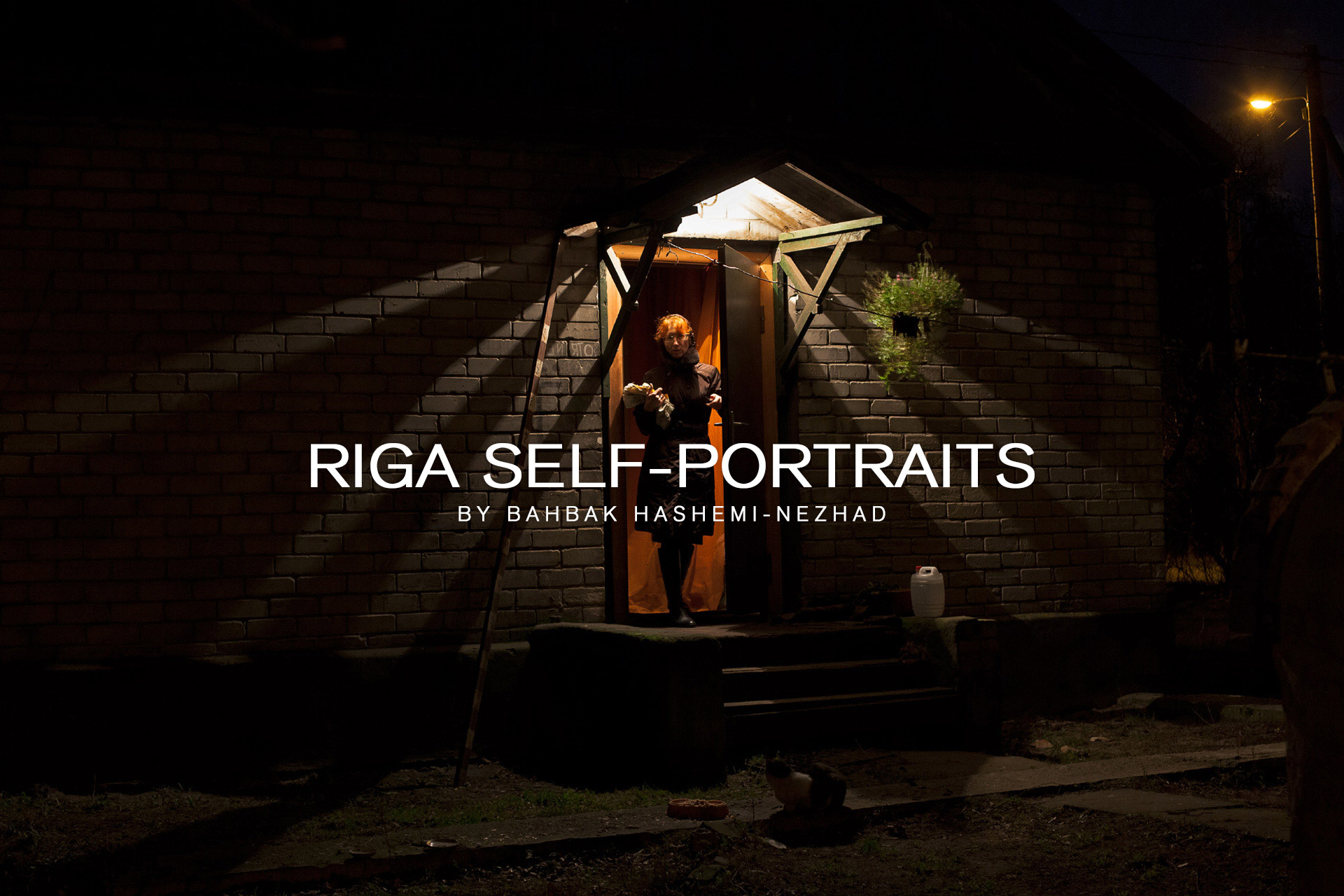

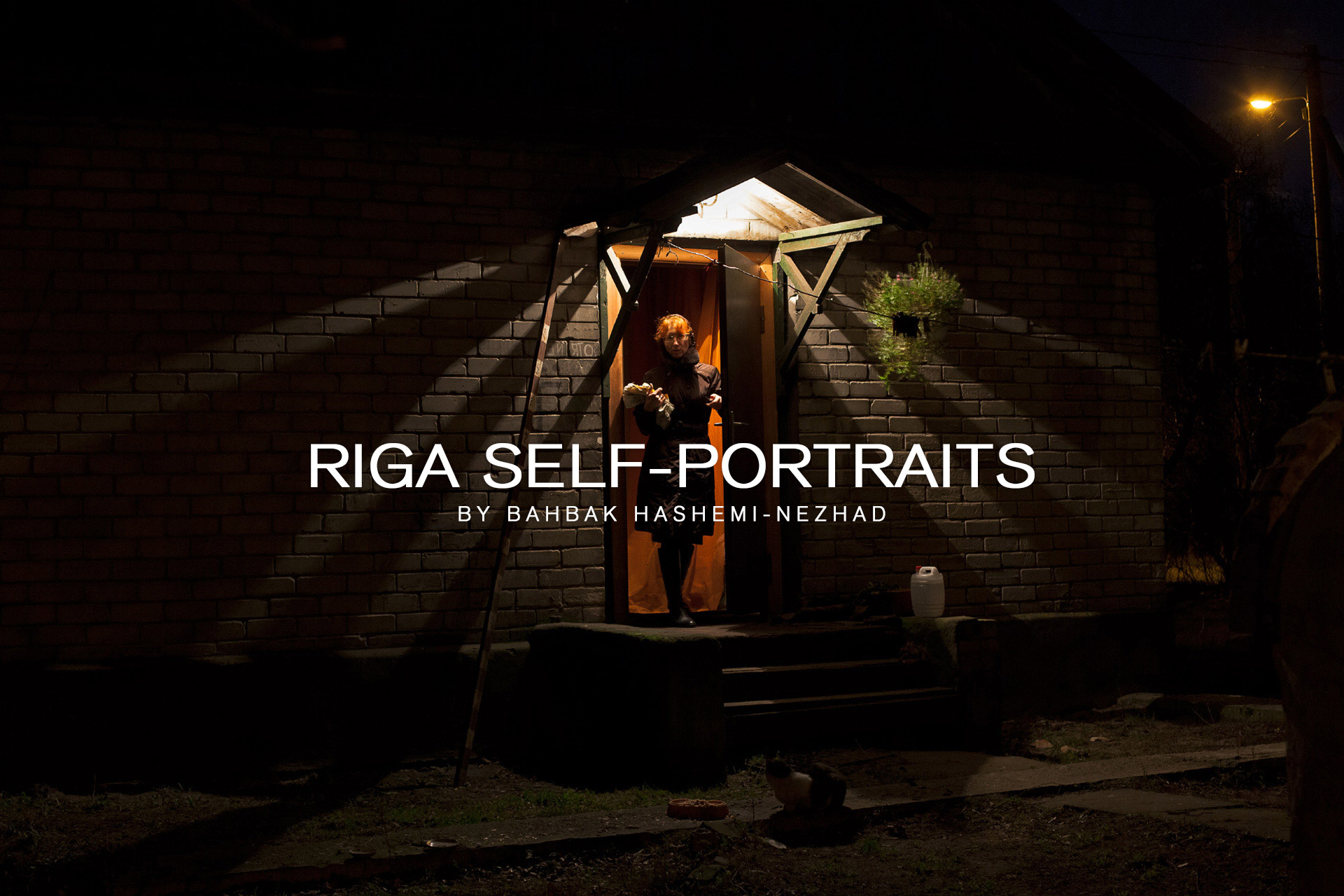

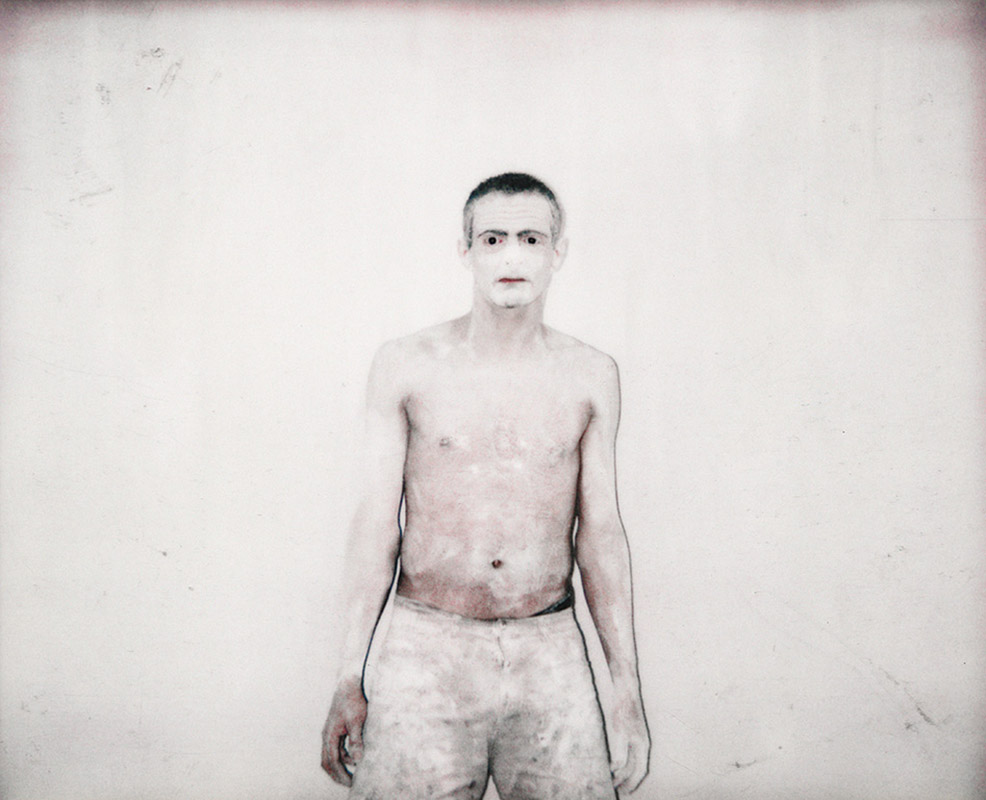

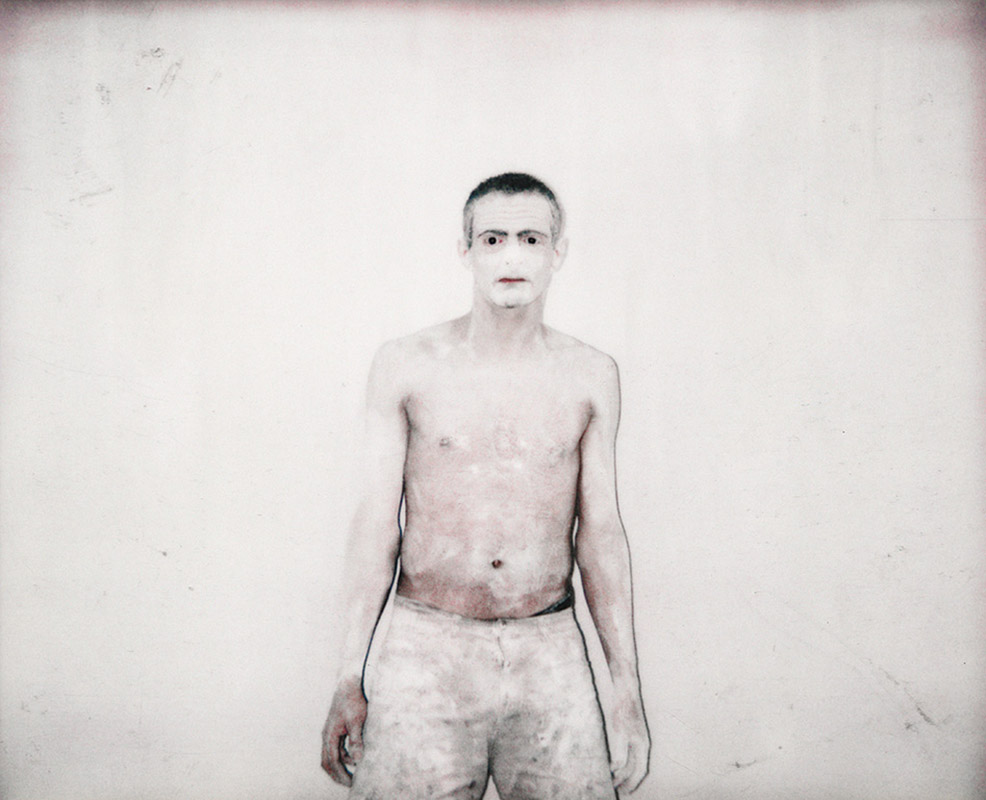

These images are the results of chance public encounters during a series of walks in Bolderaja, a largely Russian-speaking area of Riga which was industrialised and militarised during the soviet occupation.

Over three days in late November 2013, members of the public were requested to remotely photograph themselves and momentarily act out their everyday realities whilst continuing the situations in which they were encountered.

Set against new and yet to be completed housing developments, industrial estates, local businesses and suburban landscapes, these self-portraits act as vignettes, highlighting the roles the individuals play and the pleasures they experience in the public realm.

The Riga Self-portraits were made in the context of the international community art project 'Contemporary Self-Portraits'. During this two-year project (September 2012–August 2014), self-portrait workshops were held in various European regions: Finland (Turku), Estonia (Tallinn), Ireland (Dublin), Latvia (Riga) and Sweden (Umeå).

The aim was to give local inhabitants a voice in expressing their personal and collective identity, as well as to encourage the development and sharing of communal art methodology and community development through arts.

The results were presented at exhibitions in each partner country and at a Final Symposium in Umea in 2014.

Bahbak Hashemi-Nezhad (England, 1979). He graduated from the Royal College of Art in 2008 and founded a cross-disciplinary practice that has produced work ranging from product design, domestic and public spaces, photography, to food, games and public interventions. His practice is concerned with exploring the role of photography within design research, and with developing new design methodologies that actively engage individual users. bh-n.com

Bahbak Hashemi-Nezhad (England, 1979). He graduated from the Royal College of Art in 2008 and founded a cross-disciplinary practice that has produced work ranging from product design, domestic and public spaces, photography, to food, games and public interventions. His practice is concerned with exploring the role of photography within design research, and with developing new design methodologies that actively engage individual users. bh-n.com

These images are the results of chance public encounters during a series of walks in Bolderaja, a largely Russian-speaking area of Riga which was industrialised and militarised during the soviet occupation.

Over three days in late November 2013, members of the public were requested to remotely photograph themselves and momentarily act out their everyday realities whilst continuing the situations in which they were encountered.

Set against new and yet to be completed housing developments, industrial estates, local businesses and suburban landscapes, these self-portraits act as vignettes, highlighting the roles the individuals play and the pleasures they experience in the public realm.

The Riga Self-portraits were made in the context of the international community art project 'Contemporary Self-Portraits'. During this two-year project (September 2012–August 2014), self-portrait workshops were held in various European regions: Finland (Turku), Estonia (Tallinn), Ireland (Dublin), Latvia (Riga) and Sweden (Umeå).

The aim was to give local inhabitants a voice in expressing their personal and collective identity, as well as to encourage the development and sharing of communal art methodology and community development through arts.

The results were presented at exhibitions in each partner country and at a Final Symposium in Umea in 2014.

Bahbak Hashemi-Nezhad (England, 1979). He graduated from the Royal College of Art in 2008 and founded a cross-disciplinary practice that has produced work ranging from product design, domestic and public spaces, photography, to food, games and public interventions. His practice is concerned with exploring the role of photography within design research, and with developing new design methodologies that actively engage individual users. bh-n.com

Bahbak Hashemi-Nezhad (England, 1979). He graduated from the Royal College of Art in 2008 and founded a cross-disciplinary practice that has produced work ranging from product design, domestic and public spaces, photography, to food, games and public interventions. His practice is concerned with exploring the role of photography within design research, and with developing new design methodologies that actively engage individual users. bh-n.comVanessa Alcaíno & Elisa Rugo

That which I call my self-portrait is composed of thousands of days of work.

Each of them corresponds to the exact number and moment at which

I stopped as I painted after a task.

—Roman Opalka

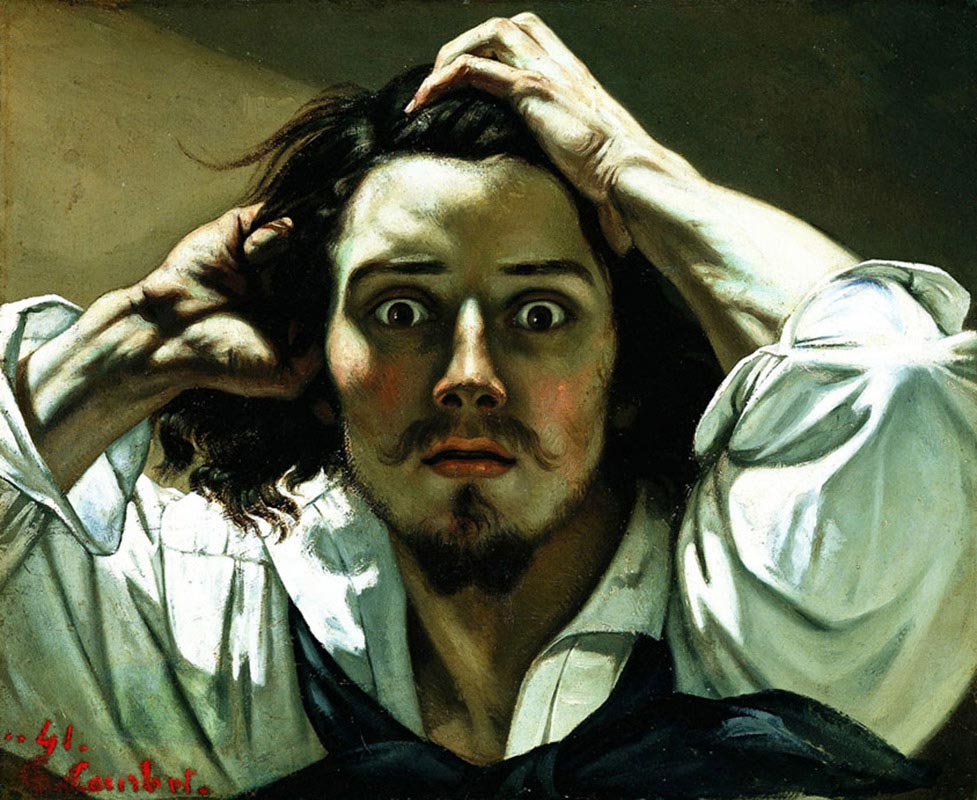

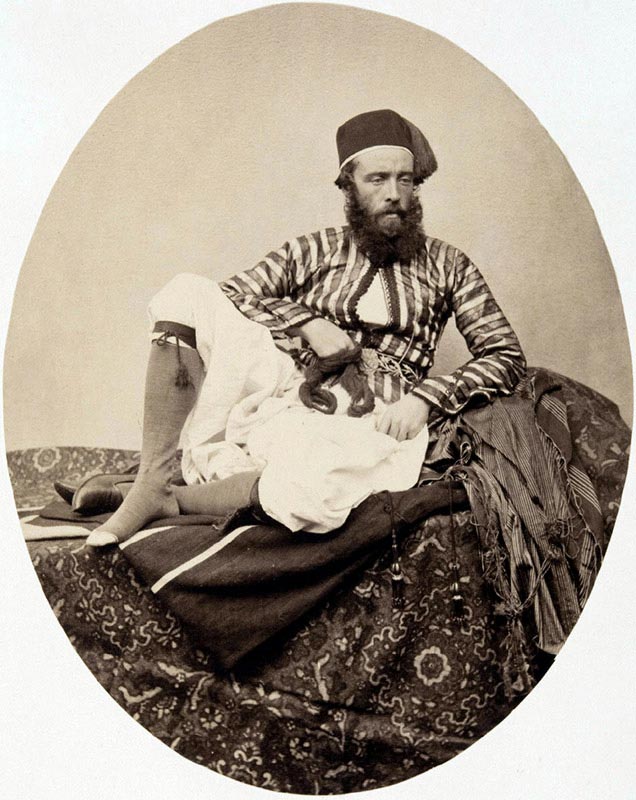

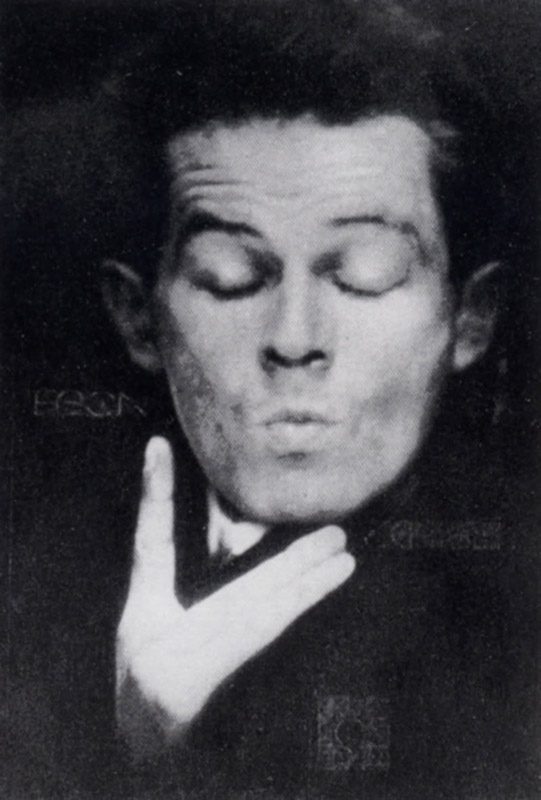

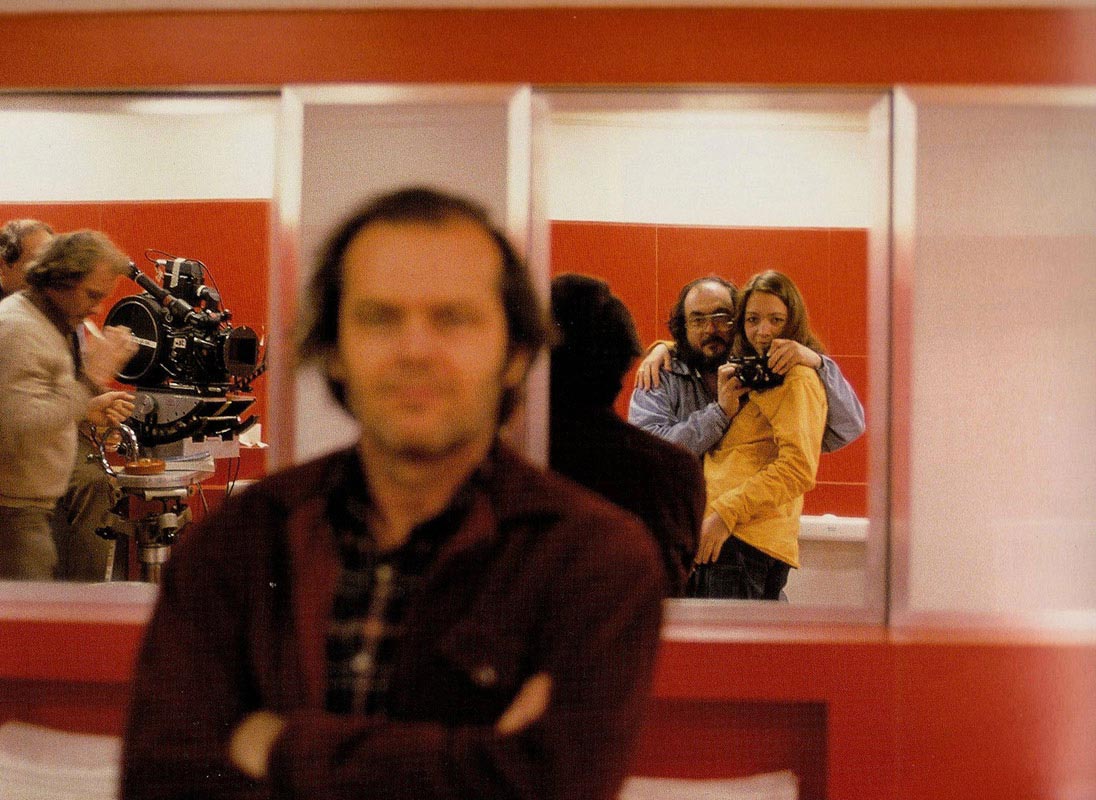

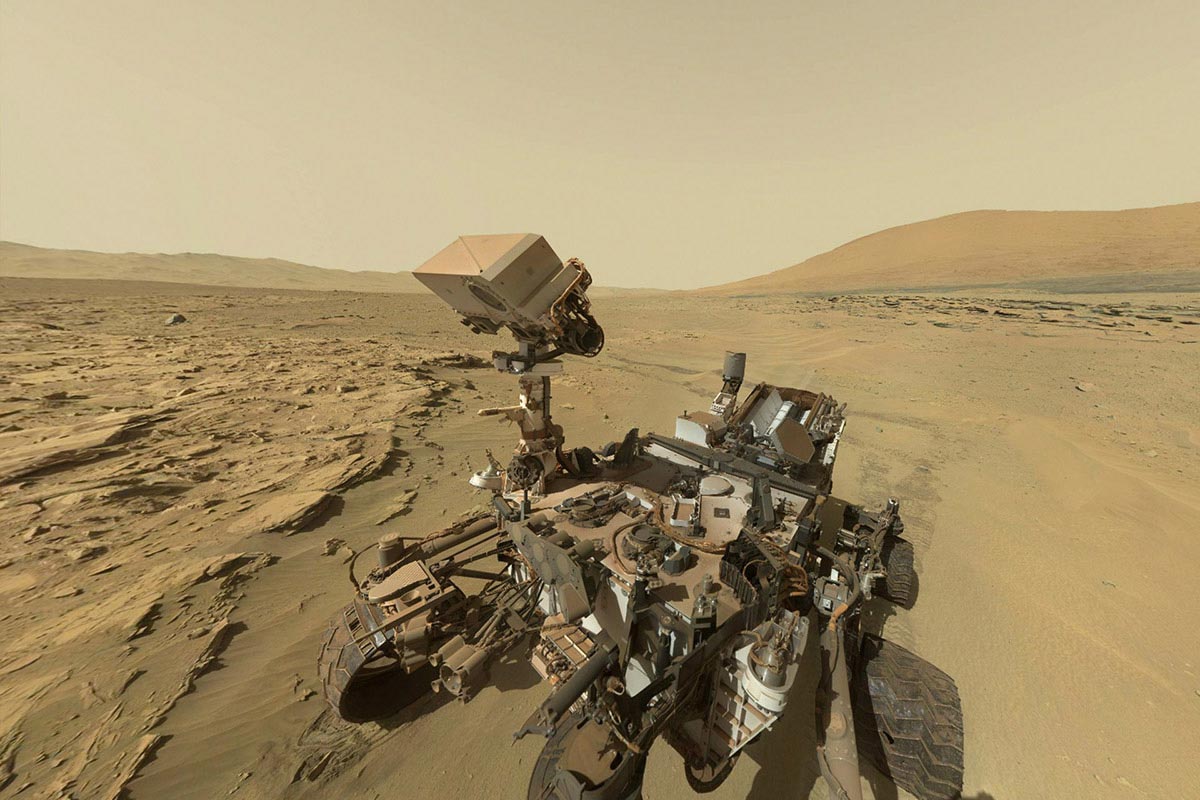

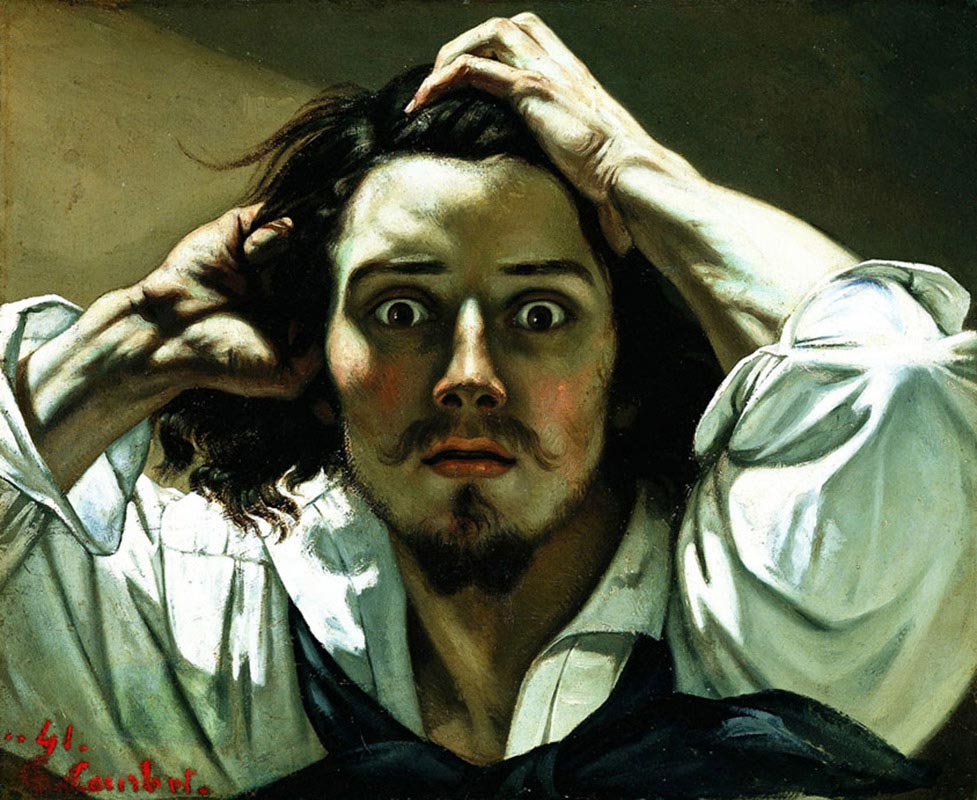

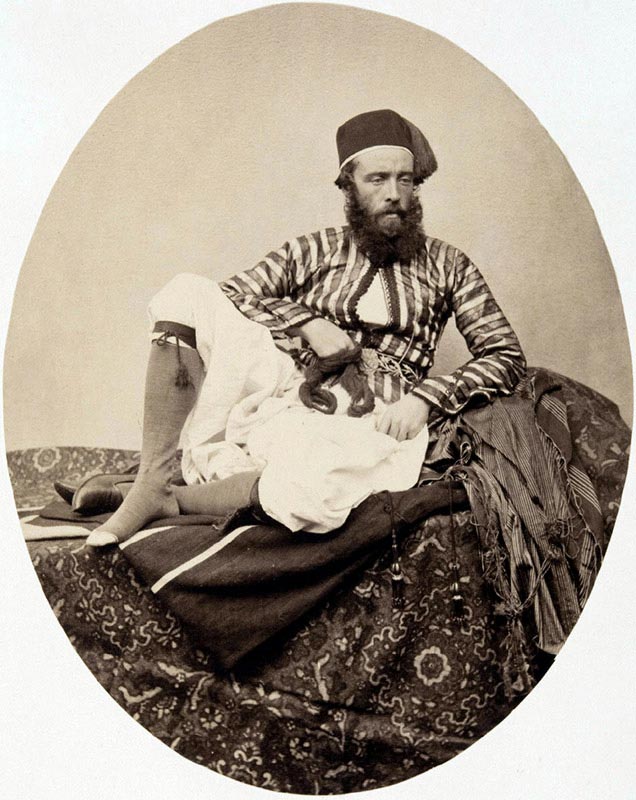

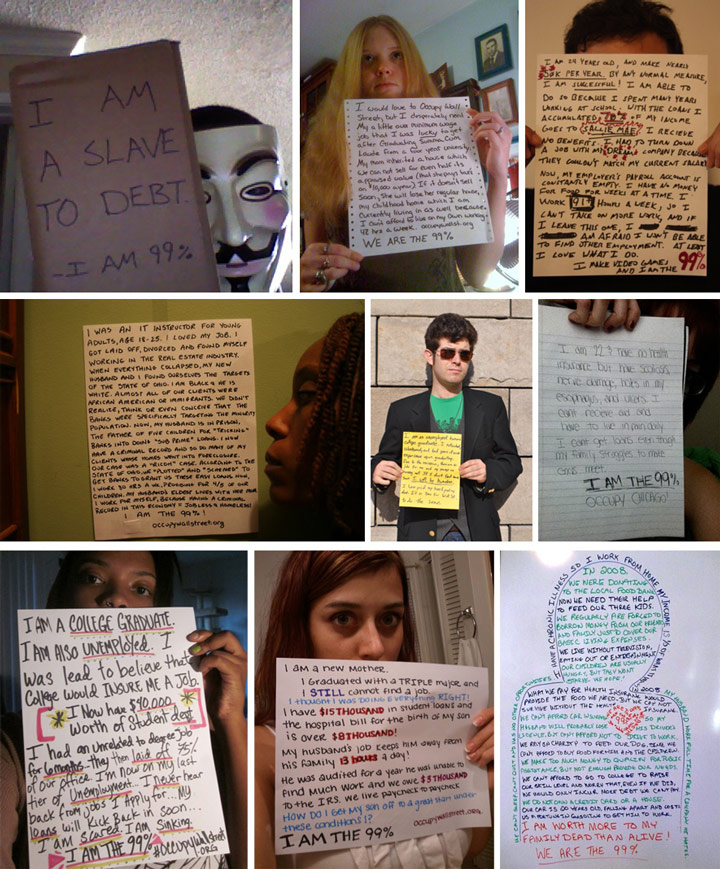

Through the various forms of artistic expression over the last 500 years, the natural relationship born between the creator and his work tool has offered a rough testimony of self-exploration. We can see it from the self-portraits of Renaissance painters to the self-explorations produced by photographers opposite a mirror. The difference is that today we live in, thorough and for the image, and the image has driven us to communicate in a new way. Today, it has become a right to possess images of one’s self, and in this context the selfie appears to have emerged as a logical derivation of this human action.

Could we therefore consider selfies within the tradition of the self-portrait? Do they serve to search for, or develop, one’s identity? Let us begin with the idea that a selfie is not only a self-portrait in the traditional sense of the word. The selfie is created using a smart phone or webcam and places us in a spontaneous context or situation, showing its relative lack of preparation, but it also contains metadata that are commented on and shared repeatedly. This could define it as an emerging sub-genre of the self-portrait1, as taking this photographic image is in line with the new platforms of audiovisual communication.

However, the most appealing facet of this “new” trend is its social value. Current-day self-portraits do not seek to say this is me or this is how I am, as was done in times gone by to construct an identity, but rather they follow the logic of here I am or this is where I am. Being somewhere at a given moment prevails over just being. Persons therefore show themselves in a location, saying: this is where and how I am right now, with a mood: this is how I am today, or even, when in company: here I am with so-and-so. “Photography is not a memory, but an act”.2

The numerous self-portraits published every day construct visual diaries that show us multiple, plural and at the same time communal “private” stories. They are, in the digital era, the result of the democratization of the image, and acquire meaning once they are shared, not only among a specific group of persons (friends and/or relatives), but among all those who construct meaning through their interactions. The more active the exchange in networks, the stronger the links between their participants.

There are currently pages specializing in selfies that gather images in similar situations (selfiesatfunerals, selfieswithhomelesspeople, selfiesatseriousplaces, museumselfies.tumblr.com), projects that bring together collections of the (app.thefacesoffacebook, A través del espejo by Joan Fontcuberta), studies (selfiecity.net), new trends (Shaky Selfie), competitions, festivals (ClaroEcuador, Olimpiadas del selfie) and every day new apps appear that encourage us to tell a story by capturing images (Frontback). On many occasions film stars, musicians and celebrities such as the Pope or presidents express themselves through this medium, creating an intimate proximity with the public.

Taking photographs (of one’s self) has become an ordinary, everyday action. As Fontcuberta writes, it has become a compulsion. A vital compulsion in which each heartbeat becomes an image, such as the project The Whale Hunt, by Jonathan Harris, which uses 3,214 timed photographs to show in frequencies the most powerful moments of his experience of whale hunting. We are in an era that strives to photograph everything and create an interaction, in a context in which the photographic image has become a desire to speak. May nothing remain unrecorded or unshared! as we only exist insofar as we are present online.

What then of privacy? The intimate has become public. In 2000, a performance was presented called Nautilus, casa transparente.3 It consisted of a space with translucent walls in which a person was carrying out their daily life. People, some curious, others outraged, spend hours obsessively observing this person in his ordinary intimacy, as though he were an animal in a zoo. A few years later, and thanks to photography and its connectivity, we appear to be putting ourselves in this person’s place willingly and living in our own glass houses, exhibiting our everyday life without fear or prejudice.

Today’s democratized self-portrait is a public declaration carrying the message of our identity. The numerous devices and platforms used to communicate through the image enable us to react and create the need to leave a trace, in order for others to discover us. The selfie has become a social phenomenon of self-expression that can be as diverse as humanity itself, but we do not know to what extent social or cultural experiences are measured by the endless software. We are therefore invited to continue to take portraits of ourselves until technology becomes insufficient and we exceed the mobility, ubiquity and connection offered by the fifth moment of photography.4

1 Tifentale, Alise. The Selfie: Making sense of the “Masturbation of Self-Image” and the “Virtual Mini-Me”. February 2014 / selfiecity.net

2 Fontcuberta, Joan. Quote from Joan Fontcuberta: el post-talento fotográfico. February 2014 by Galcerán de Born

3 Nautilus, casa transparente, an original idea by the Chilean architect Arturo Torres

4 The fifth momento of photography explores the effect of the iphone on photography, the technological 'mash-up' with the internet and omnipresent social connectivity. Edgar Gómez, and Eric T. Meyer. Creation and Control in the Photographic Process: iPhones and the Emerging Fifth Moment of Photography. Photographies 5, number 2 (2012): 203-221.

Vanessa Alcaíno Pizani (Venezuela, 1980). Lives and works in Mexico. Visual artist. She graduated in Philosophy at the Central University of Venezuela and has a Master’s degree in Spanish and Latin American Thought at the Autonomous University of Madrid (UAM). Since 1994, she has worked in the field of photography at various institutions and organisations in Venezuela, Argentina and Mexico. At the moment, she is part of the editorial team of zonezero.com. You can see her work at: vanessapizani

Vanessa Alcaíno Pizani (Venezuela, 1980). Lives and works in Mexico. Visual artist. She graduated in Philosophy at the Central University of Venezuela and has a Master’s degree in Spanish and Latin American Thought at the Autonomous University of Madrid (UAM). Since 1994, she has worked in the field of photography at various institutions and organisations in Venezuela, Argentina and Mexico. At the moment, she is part of the editorial team of zonezero.com. You can see her work at: vanessapizani Elisa Rugo (Mexico, 1980). Lives and works in Mexico. She is a photographer, videographer and a specialist in visual communication with a degree in Creative Visualisation at the University of Communication. In 2012, she took part in the seminar Contemporary Photography at the Image Centre. She has participated in collective exhibitions in Pachuca, Querétaro, Guadalajara and Mexico-City. At the moment, she is the art director of the websites fpmeyer.com and museodemujeres.com and she is part of the editorial team of zonezero.com. You can see her work at: elisarugo.pro

Elisa Rugo (Mexico, 1980). Lives and works in Mexico. She is a photographer, videographer and a specialist in visual communication with a degree in Creative Visualisation at the University of Communication. In 2012, she took part in the seminar Contemporary Photography at the Image Centre. She has participated in collective exhibitions in Pachuca, Querétaro, Guadalajara and Mexico-City. At the moment, she is the art director of the websites fpmeyer.com and museodemujeres.com and she is part of the editorial team of zonezero.com. You can see her work at: elisarugo.proThat which I call my self-portrait is composed of thousands of days of work.

Each of them corresponds to the exact number and moment at which

I stopped as I painted after a task.

—Roman Opalka

Through the various forms of artistic expression over the last 500 years, the natural relationship born between the creator and his work tool has offered a rough testimony of self-exploration. We can see it from the self-portraits of Renaissance painters to the self-explorations produced by photographers opposite a mirror. The difference is that today we live in, thorough and for the image, and the image has driven us to communicate in a new way. Today, it has become a right to possess images of one’s self, and in this context the selfie appears to have emerged as a logical derivation of this human action.

Could we therefore consider selfies within the tradition of the self-portrait? Do they serve to search for, or develop, one’s identity? Let us begin with the idea that a selfie is not only a self-portrait in the traditional sense of the word. The selfie is created using a smart phone or webcam and places us in a spontaneous context or situation, showing its relative lack of preparation, but it also contains metadata that are commented on and shared repeatedly. This could define it as an emerging sub-genre of the self-portrait1, as taking this photographic image is in line with the new platforms of audiovisual communication.

However, the most appealing facet of this “new” trend is its social value. Current-day self-portraits do not seek to say this is me or this is how I am, as was done in times gone by to construct an identity, but rather they follow the logic of here I am or this is where I am. Being somewhere at a given moment prevails over just being. Persons therefore show themselves in a location, saying: this is where and how I am right now, with a mood: this is how I am today, or even, when in company: here I am with so-and-so. “Photography is not a memory, but an act”.2

The numerous self-portraits published every day construct visual diaries that show us multiple, plural and at the same time communal “private” stories. They are, in the digital era, the result of the democratization of the image, and acquire meaning once they are shared, not only among a specific group of persons (friends and/or relatives), but among all those who construct meaning through their interactions. The more active the exchange in networks, the stronger the links between their participants.

There are currently pages specializing in selfies that gather images in similar situations (selfiesatfunerals, selfieswithhomelesspeople, selfiesatseriousplaces, museumselfies.tumblr.com), projects that bring together collections of the (app.thefacesoffacebook, A través del espejo by Joan Fontcuberta), studies (selfiecity.net), new trends (Shaky Selfie), competitions, festivals (ClaroEcuador, Olimpiadas del selfie) and every day new apps appear that encourage us to tell a story by capturing images (Frontback). On many occasions film stars, musicians and celebrities such as the Pope or presidents express themselves through this medium, creating an intimate proximity with the public.

Taking photographs (of one’s self) has become an ordinary, everyday action. As Fontcuberta writes, it has become a compulsion. A vital compulsion in which each heartbeat becomes an image, such as the project The Whale Hunt, by Jonathan Harris, which uses 3,214 timed photographs to show in frequencies the most powerful moments of his experience of whale hunting. We are in an era that strives to photograph everything and create an interaction, in a context in which the photographic image has become a desire to speak. May nothing remain unrecorded or unshared! as we only exist insofar as we are present online.

What then of privacy? The intimate has become public. In 2000, a performance was presented called Nautilus, casa transparente.3 It consisted of a space with translucent walls in which a person was carrying out their daily life. People, some curious, others outraged, spend hours obsessively observing this person in his ordinary intimacy, as though he were an animal in a zoo. A few years later, and thanks to photography and its connectivity, we appear to be putting ourselves in this person’s place willingly and living in our own glass houses, exhibiting our everyday life without fear or prejudice.

Today’s democratized self-portrait is a public declaration carrying the message of our identity. The numerous devices and platforms used to communicate through the image enable us to react and create the need to leave a trace, in order for others to discover us. The selfie has become a social phenomenon of self-expression that can be as diverse as humanity itself, but we do not know to what extent social or cultural experiences are measured by the endless software. We are therefore invited to continue to take portraits of ourselves until technology becomes insufficient and we exceed the mobility, ubiquity and connection offered by the fifth moment of photography.4

1 Tifentale, Alise. The Selfie: Making sense of the “Masturbation of Self-Image” and the “Virtual Mini-Me”. February 2014 / selfiecity.net

2 Fontcuberta, Joan. Quote from Joan Fontcuberta: el post-talento fotográfico. February 2014 by Galcerán de Born

3 Nautilus, casa transparente, an original idea by the Chilean architect Arturo Torres

4 The fifth momento of photography explores the effect of the iphone on photography, the technological 'mash-up' with the internet and omnipresent social connectivity. Edgar Gómez, and Eric T. Meyer. Creation and Control in the Photographic Process: iPhones and the Emerging Fifth Moment of Photography. Photographies 5, number 2 (2012): 203-221.

Vanessa Alcaíno Pizani (Venezuela, 1980). Lives and works in Mexico. Visual artist. She graduated in Philosophy at the Central University of Venezuela and has a Master’s degree in Spanish and Latin American Thought at the Autonomous University of Madrid (UAM). Since 1994, she has worked in the field of photography at various institutions and organisations in Venezuela, Argentina and Mexico. At the moment, she is part of the editorial team of zonezero.com. You can see her work at: vanessapizani

Vanessa Alcaíno Pizani (Venezuela, 1980). Lives and works in Mexico. Visual artist. She graduated in Philosophy at the Central University of Venezuela and has a Master’s degree in Spanish and Latin American Thought at the Autonomous University of Madrid (UAM). Since 1994, she has worked in the field of photography at various institutions and organisations in Venezuela, Argentina and Mexico. At the moment, she is part of the editorial team of zonezero.com. You can see her work at: vanessapizani Elisa Rugo (Mexico, 1980). Lives and works in Mexico. She is a photographer, videographer and a specialist in visual communication with a degree in Creative Visualisation at the University of Communication. In 2012, she took part in the seminar Contemporary Photography at the Image Centre. She has participated in collective exhibitions in Pachuca, Querétaro, Guadalajara and Mexico-City. At the moment, she is the art director of the websites fpmeyer.com and museodemujeres.com and she is part of the editorial team of zonezero.com. You can see her work at: elisarugo.pro

Elisa Rugo (Mexico, 1980). Lives and works in Mexico. She is a photographer, videographer and a specialist in visual communication with a degree in Creative Visualisation at the University of Communication. In 2012, she took part in the seminar Contemporary Photography at the Image Centre. She has participated in collective exhibitions in Pachuca, Querétaro, Guadalajara and Mexico-City. At the moment, she is the art director of the websites fpmeyer.com and museodemujeres.com and she is part of the editorial team of zonezero.com. You can see her work at: elisarugo.proCatherine Balet

Catherine Balet (France, 1959). Lives and works between Paris and Brighton. She graduated at the Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris and worked as an artist before turning to Photography ten years ago. As a freelancer, she has been a regular contributor to various french and international magazines, also creating images for the world of fashion. She has today specialised in portraiture with an artistico-sociological approach of her subjects. To see more of her work go to: catherinebalet.

Catherine Balet (France, 1959). Lives and works between Paris and Brighton. She graduated at the Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris and worked as an artist before turning to Photography ten years ago. As a freelancer, she has been a regular contributor to various french and international magazines, also creating images for the world of fashion. She has today specialised in portraiture with an artistico-sociological approach of her subjects. To see more of her work go to: catherinebalet.ZZ. Identity is an important theme in your work. How do you think identity is effected by the social media and new technologies?

CB. I am mainly interested in the quest for identity because it is a very revealing process of creativity and sociology. I try to depict young people in search of identity for the reason that teenagers are very innovative with the tools they use to express themselves. Ten years ago, I started a photographic series on the expression of identity through clothes, brands, trends and groups, as it was a very intense phenomenon at that time. This naturally brought me to technology, the devices having replaced the clothes as medium of self-expression. "Selfies" allow teenagers, who are going through the complex process of the creation of their identity, to be themselves and at the same time to be like the ones they admire. The disposable and renewable images they make of themselves are the best expression of the permanent changes they are experiencing. The fact that they can renew their profile and follow the group that they have chosen by conforming to codes of representation is essential in developing their identity. It allows them to validate their opinions and determine the appropriateness of their attitudes and behaviours. Teenagers have an enhanced need for self-presentation. Communicating their identity to others works as an act of auto-revelation. Mobile phones have become a sort of digital prosthesis which connects the "real me" to the "virtual me” through social networks, creating a double personality.

ZZ. I love myself, I love me, I do refers to the narcissistic self-awareness expressed on social networks. Do you consider 'the selfie' to be only a product of narcissism or do you think there is more to it?

CB. Narcissus was in love with himself and not looking for interaction. I think that taking a "selfie" is not a self-centred act but a way to become affiliated to a large universal community. "Selfies" are social portraits created in order to open up to others and to look for validation of one’s existence; questioning and looking for witnesses to confirm that you are doing the right thing. It’s more about taking part in a parallel and idealised world. The central quality of these self-images is that they are "shareable". Today, pictures have replaced words in an interactive conversation that is often full of humour and self-mockery.

ZZ. The video also refers to the new approach to quick, light mobile photography that affects our visual culture. What do you think of this development in visual culture?

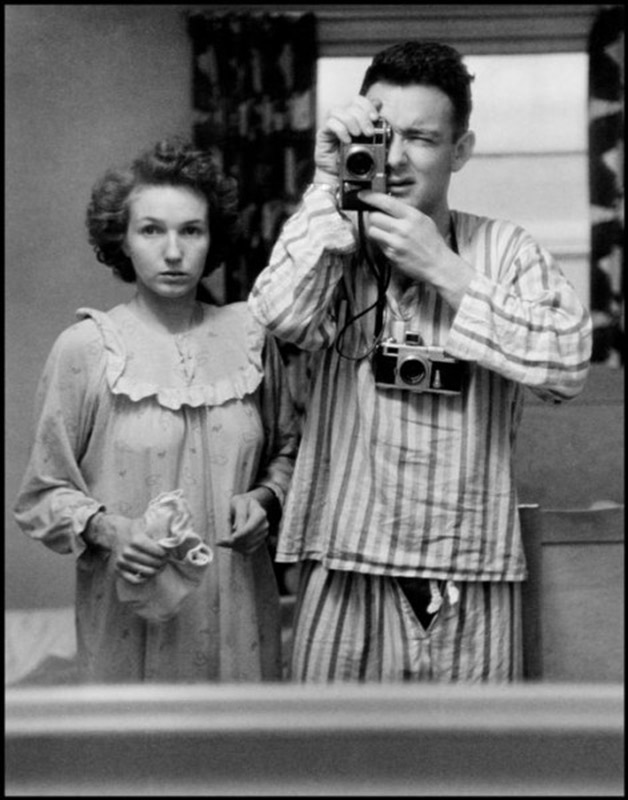

CB. I did this video because I was interested in the new body attitude that "selfies" have established. It is about staging the photographic gesture itself, with the arm up and the mobile phone reflected in the mirror. The codes adopted in these photos are placed under the sign of a gestural performance.

Today, everyone who carries a phone also carries a camera. Photography has become so fundamental to the way we see things that "photography" and “seeing" could be used as synonyms nowadays. Instagram has made everyone into a photographer, as the devices offer the possibility of taking photos in practically any situation and light conditions. The improvements of technology allows us to take and retake "selfies" easily, until we are satisfied with the result, looking for the desired self in the right narrative and role. These huge amount of images have created a casual snap-shot aesthetic. Photography is not about framing and perspective any more. It has become so easy to produce an image of quality, while previously this was only possible with years of specialised training. The de-specialisation of photography questions what is worth paying attention to in these loads of images and what is going to stand the test of time? It also questions what will become of the traditional craft of photography. The very fact that a phone can be held in one hand makes it the perfect tool to capture something that is immediate, but it is not meant to create images that will resist the ravages of time.

ZZ. What effect did you want to create by relating classical painting to the contemporary digital world? Could you tell us something about the technique you used?

CB. I took the first image of the series Strangers in the light in 2008 as the digital light on people’s faces in the night fascinated me. There was a great pictorial beauty in this lighting and I became aware that these small technological lights were all over the world.

I thought that this technological glow created an aesthetic that suggested a connection to classical paintings and old masters. Thus I wished to amplify the feeling of a 21st century chiaroscuro. All the photos of the series are lit exclusively with the light of the devices. It invited me to investigate a reflection on the historic disruption that has been imposed by the invention of devices and question the ability of ubiquity that technology offers to each of us and how it has created today a world where we each live in a totally different space time as our ancestors. My characters stand in a compressed reality somewhere between past, present and future. They share fast, beautified moments in a world where speed has become the photographic priority and is changing the approach to time and memory.

For the video I love me, I love Myself, I do I wished to focus on the rhythm and frenetic obsession of short-lived "selfies". This is why I did it as a stop motion. I got my inspiration from Facebook where I noticed the teasing game of "show and hide" self-portraits, somewhere between total lack of modesty and a very strategic control of the limits of exhibitionism. My portraits are more like "twinnies" than "selfies" as I wanted them to express something about the staged relationship that is perceptible between the two characters. I whished to highlight the flashlight in the mirror, often burning the faces, as part of the scene. To take these portraits I stood in the dark with my models behind a glass pane and I used a low shutter speed to be able to capture the flash from my model’s camera.

Strangers in the light

|

|

|

|

|

Catherine Balet (France, 1959). Lives and works between Paris and Brighton. She graduated at the Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris and worked as an artist before turning to Photography ten years ago. As a freelancer, she has been a regular contributor to various french and international magazines, also creating images for the world of fashion. She has today specialised in portraiture with an artistico-sociological approach of her subjects. To see more of her work go to: catherinebalet.

Catherine Balet (France, 1959). Lives and works between Paris and Brighton. She graduated at the Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris and worked as an artist before turning to Photography ten years ago. As a freelancer, she has been a regular contributor to various french and international magazines, also creating images for the world of fashion. She has today specialised in portraiture with an artistico-sociological approach of her subjects. To see more of her work go to: catherinebalet.ZZ. Identity is an important theme in your work. How do you think identity is effected by the social media and new technologies?

CB. I am mainly interested in the quest for identity because it is a very revealing process of creativity and sociology. I try to depict young people in search of identity for the reason that teenagers are very innovative with the tools they use to express themselves. Ten years ago, I started a photographic series on the expression of identity through clothes, brands, trends and groups, as it was a very intense phenomenon at that time. This naturally brought me to technology, the devices having replaced the clothes as medium of self-expression. "Selfies" allow teenagers, who are going through the complex process of the creation of their identity, to be themselves and at the same time to be like the ones they admire. The disposable and renewable images they make of themselves are the best expression of the permanent changes they are experiencing. The fact that they can renew their profile and follow the group that they have chosen by conforming to codes of representation is essential in developing their identity. It allows them to validate their opinions and determine the appropriateness of their attitudes and behaviours. Teenagers have an enhanced need for self-presentation. Communicating their identity to others works as an act of auto-revelation. Mobile phones have become a sort of digital prosthesis which connects the "real me" to the "virtual me” through social networks, creating a double personality.

ZZ. I love myself, I love me, I do refers to the narcissistic self-awareness expressed on social networks. Do you consider 'the selfie' to be only a product of narcissism or do you think there is more to it?

CB. Narcissus was in love with himself and not looking for interaction. I think that taking a "selfie" is not a self-centred act but a way to become affiliated to a large universal community. "Selfies" are social portraits created in order to open up to others and to look for validation of one’s existence; questioning and looking for witnesses to confirm that you are doing the right thing. It’s more about taking part in a parallel and idealised world. The central quality of these self-images is that they are "shareable". Today, pictures have replaced words in an interactive conversation that is often full of humour and self-mockery.

ZZ. The video also refers to the new approach to quick, light mobile photography that affects our visual culture. What do you think of this development in visual culture?

CB. I did this video because I was interested in the new body attitude that "selfies" have established. It is about staging the photographic gesture itself, with the arm up and the mobile phone reflected in the mirror. The codes adopted in these photos are placed under the sign of a gestural performance.

Today, everyone who carries a phone also carries a camera. Photography has become so fundamental to the way we see things that "photography" and “seeing" could be used as synonyms nowadays. Instagram has made everyone into a photographer, as the devices offer the possibility of taking photos in practically any situation and light conditions. The improvements of technology allows us to take and retake "selfies" easily, until we are satisfied with the result, looking for the desired self in the right narrative and role. These huge amount of images have created a casual snap-shot aesthetic. Photography is not about framing and perspective any more. It has become so easy to produce an image of quality, while previously this was only possible with years of specialised training. The de-specialisation of photography questions what is worth paying attention to in these loads of images and what is going to stand the test of time? It also questions what will become of the traditional craft of photography. The very fact that a phone can be held in one hand makes it the perfect tool to capture something that is immediate, but it is not meant to create images that will resist the ravages of time.

ZZ. What effect did you want to create by relating classical painting to the contemporary digital world? Could you tell us something about the technique you used?

CB. I took the first image of the series Strangers in the light in 2008 as the digital light on people’s faces in the night fascinated me. There was a great pictorial beauty in this lighting and I became aware that these small technological lights were all over the world.

I thought that this technological glow created an aesthetic that suggested a connection to classical paintings and old masters. Thus I wished to amplify the feeling of a 21st century chiaroscuro. All the photos of the series are lit exclusively with the light of the devices. It invited me to investigate a reflection on the historic disruption that has been imposed by the invention of devices and question the ability of ubiquity that technology offers to each of us and how it has created today a world where we each live in a totally different space time as our ancestors. My characters stand in a compressed reality somewhere between past, present and future. They share fast, beautified moments in a world where speed has become the photographic priority and is changing the approach to time and memory.

For the video I love me, I love Myself, I do I wished to focus on the rhythm and frenetic obsession of short-lived "selfies". This is why I did it as a stop motion. I got my inspiration from Facebook where I noticed the teasing game of "show and hide" self-portraits, somewhere between total lack of modesty and a very strategic control of the limits of exhibitionism. My portraits are more like "twinnies" than "selfies" as I wanted them to express something about the staged relationship that is perceptible between the two characters. I whished to highlight the flashlight in the mirror, often burning the faces, as part of the scene. To take these portraits I stood in the dark with my models behind a glass pane and I used a low shutter speed to be able to capture the flash from my model’s camera.

Strangers in the light

|

|

|

|

|

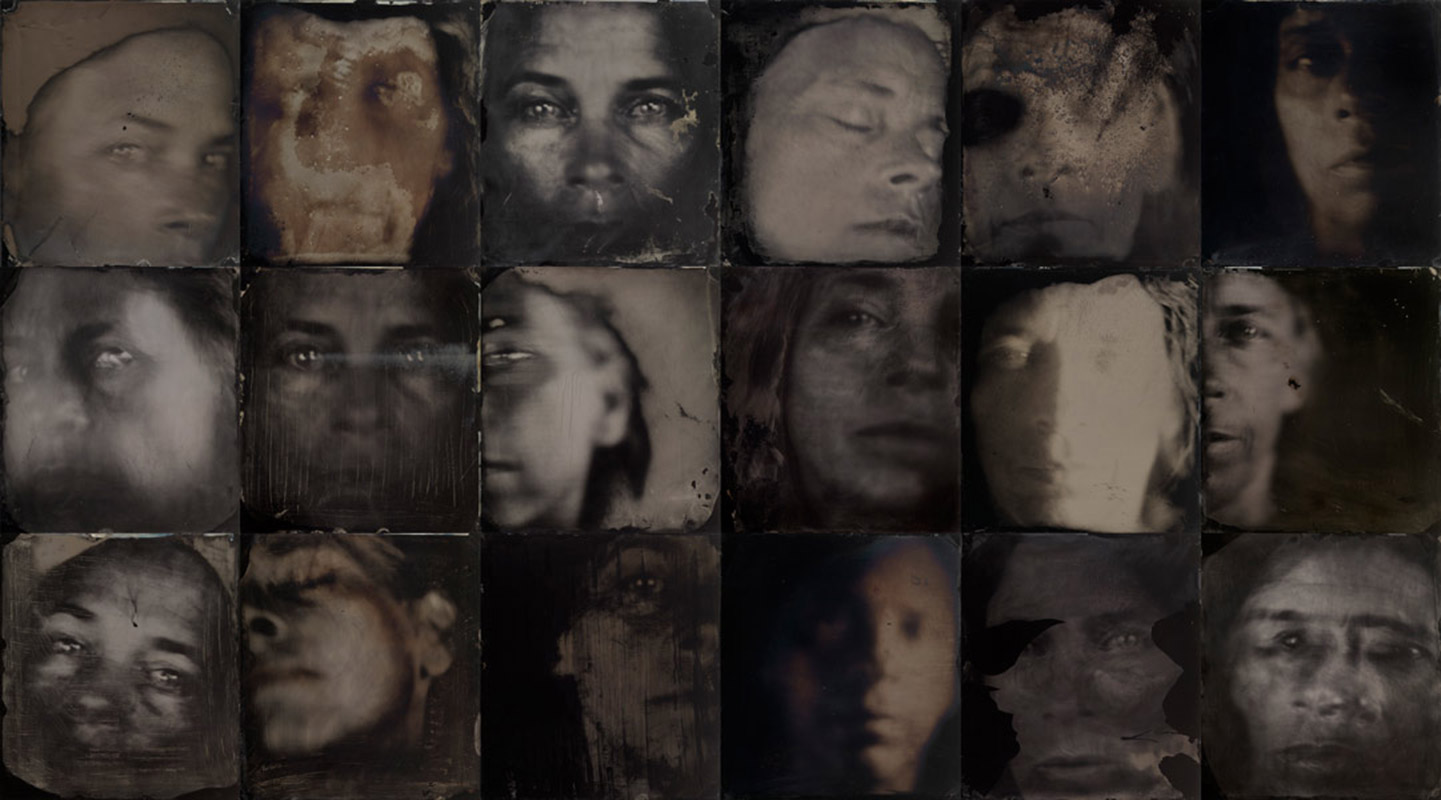

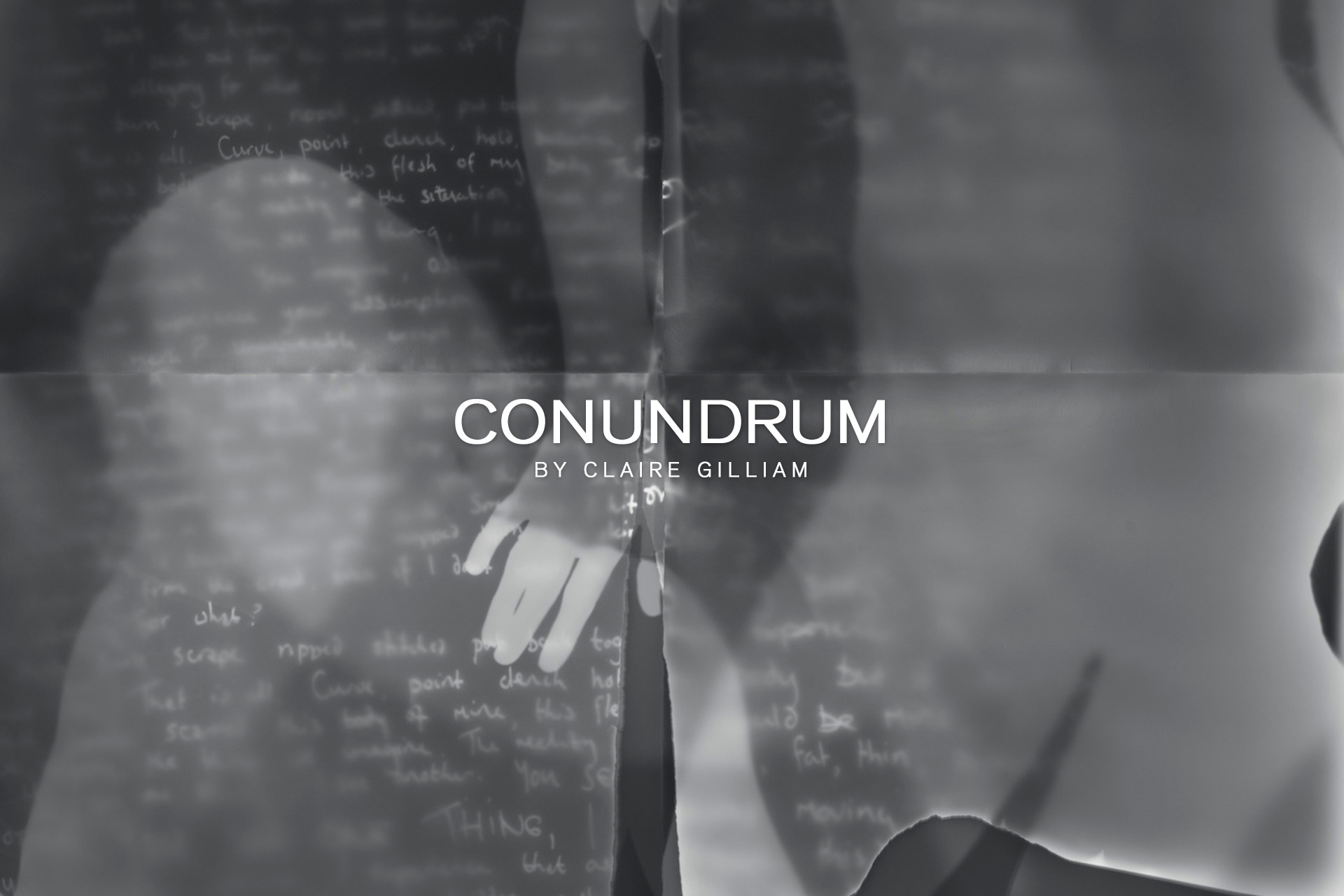

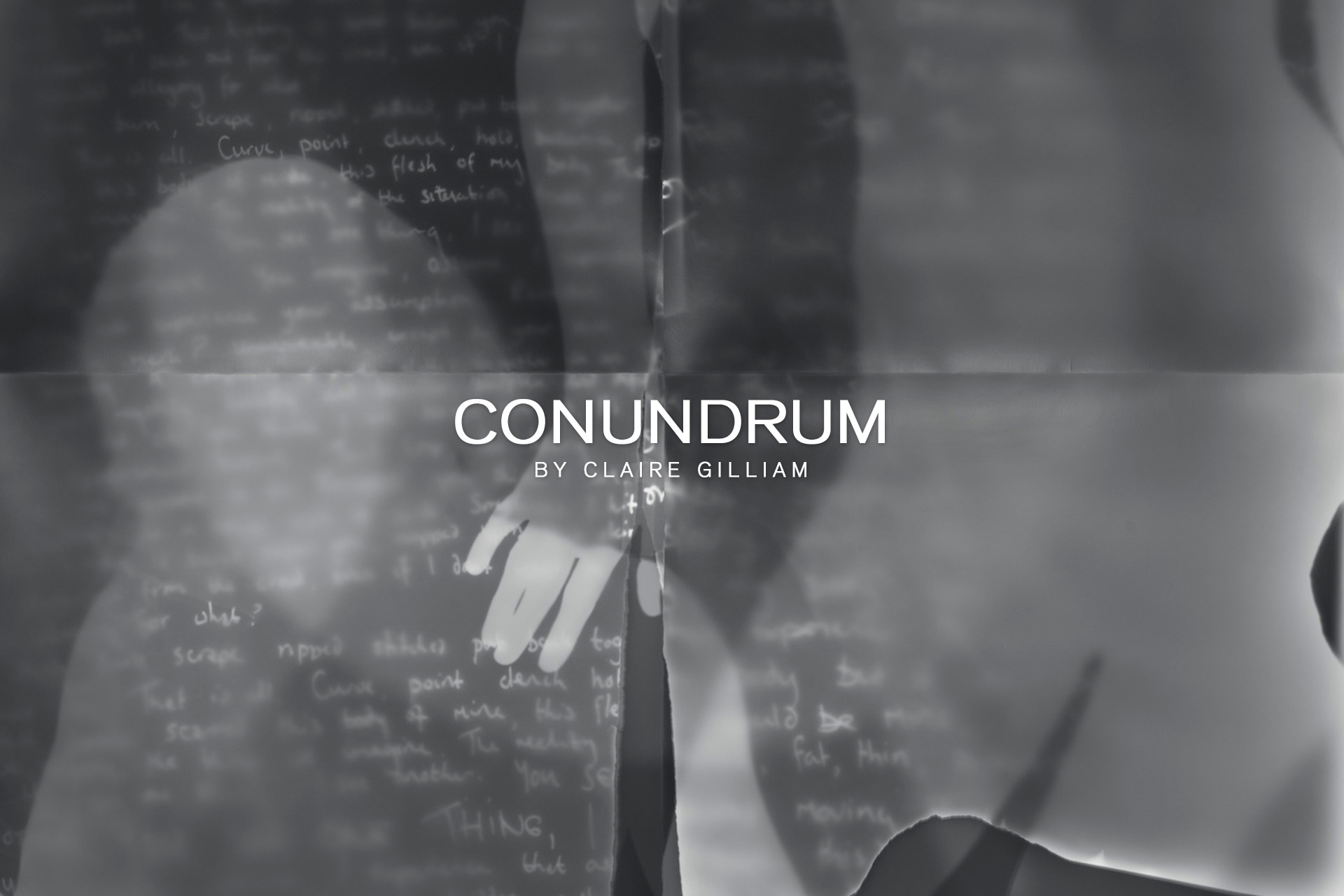

Claire Gilliam

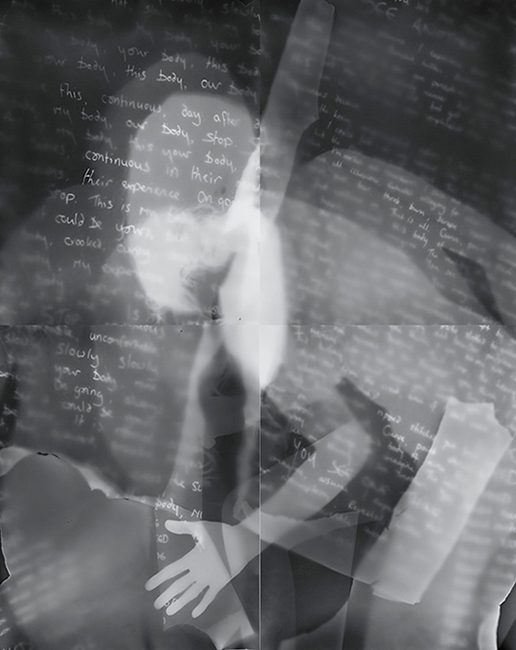

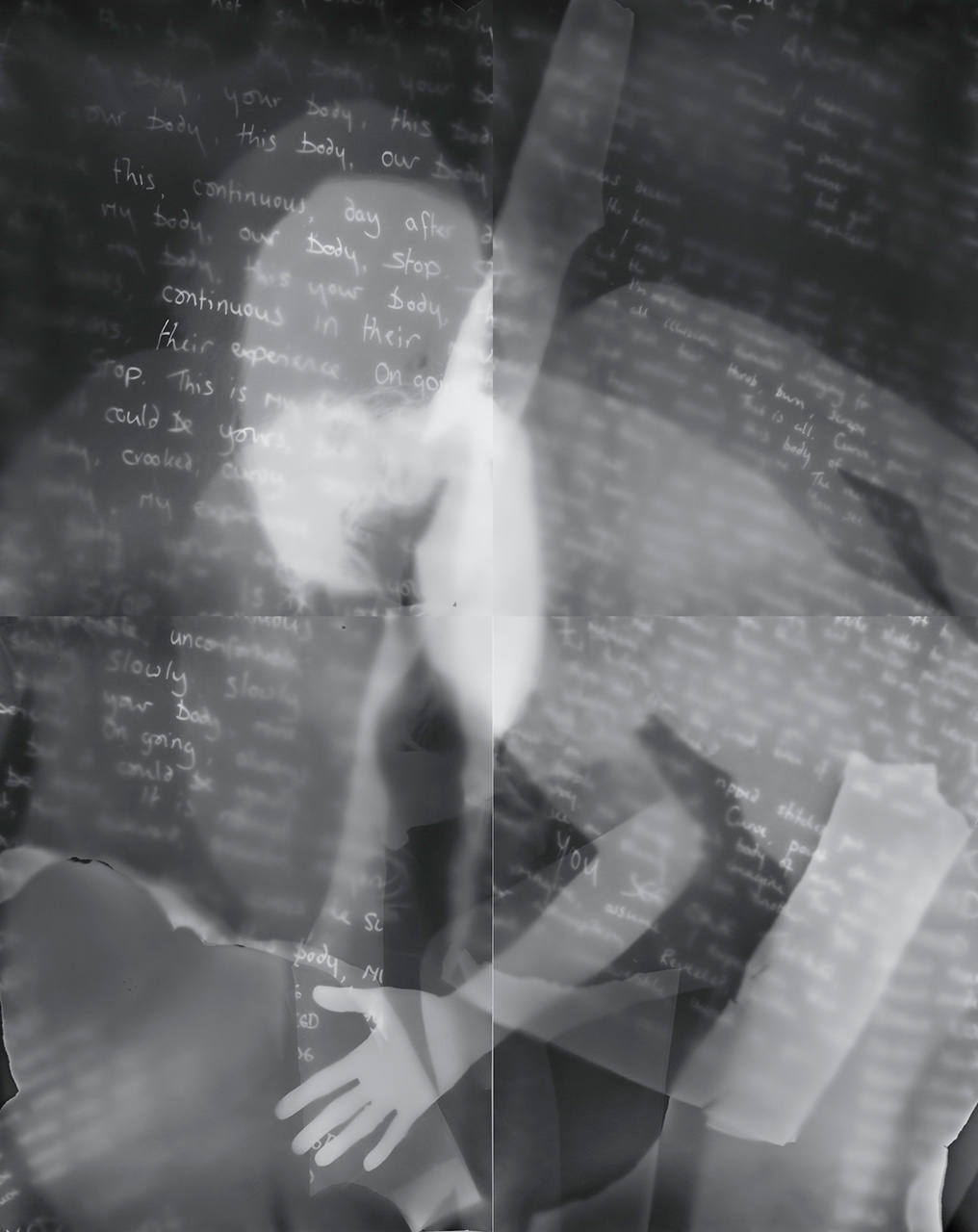

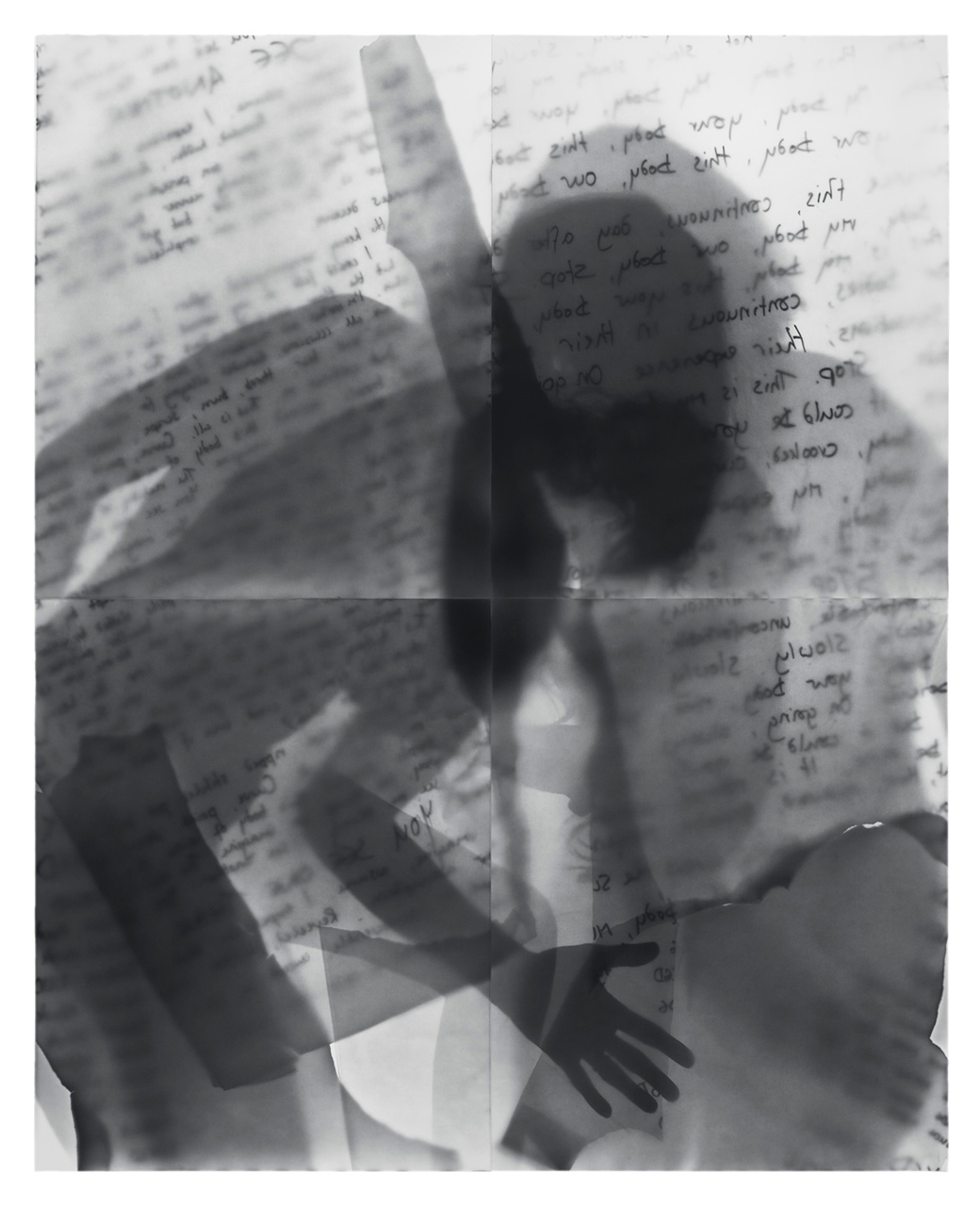

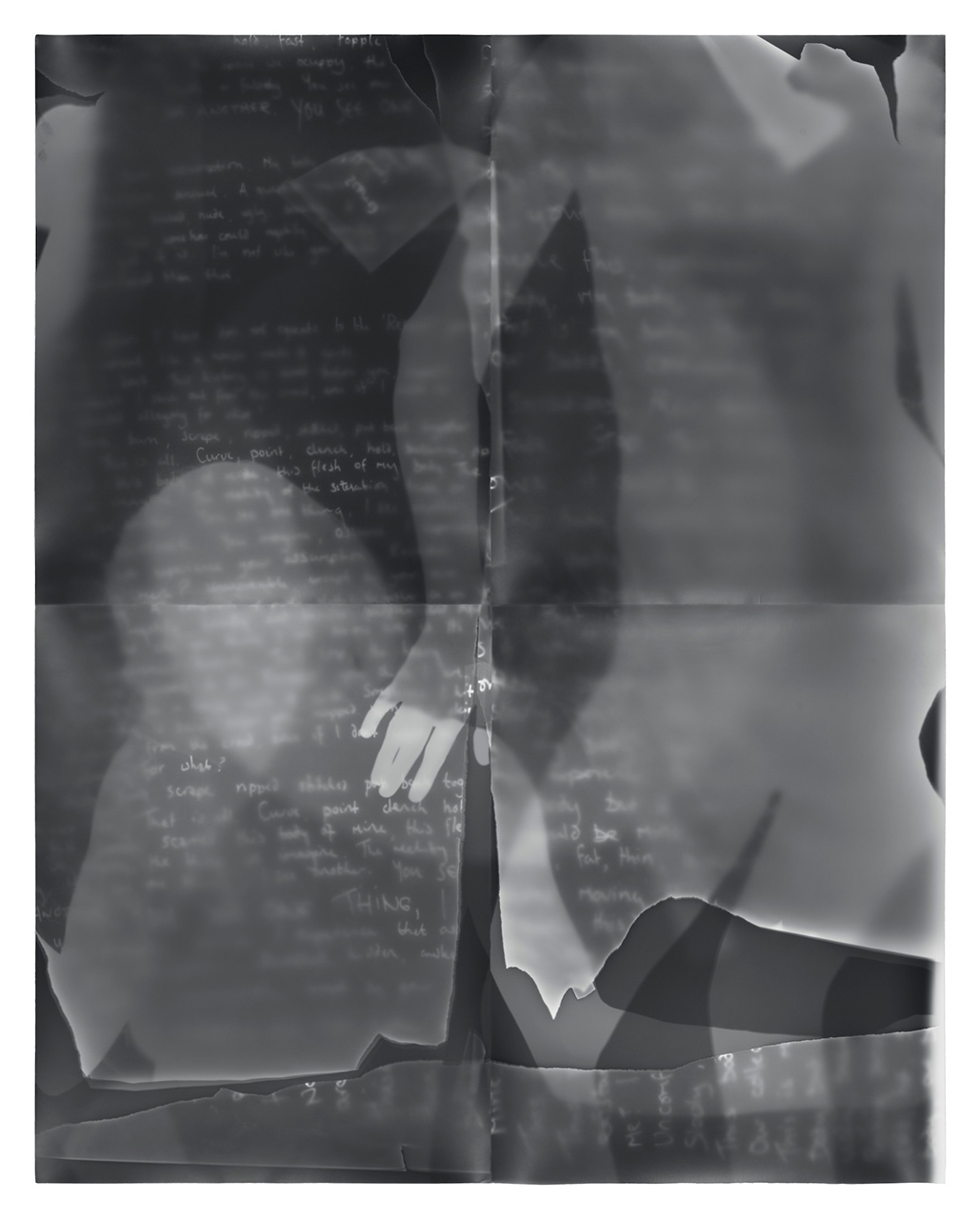

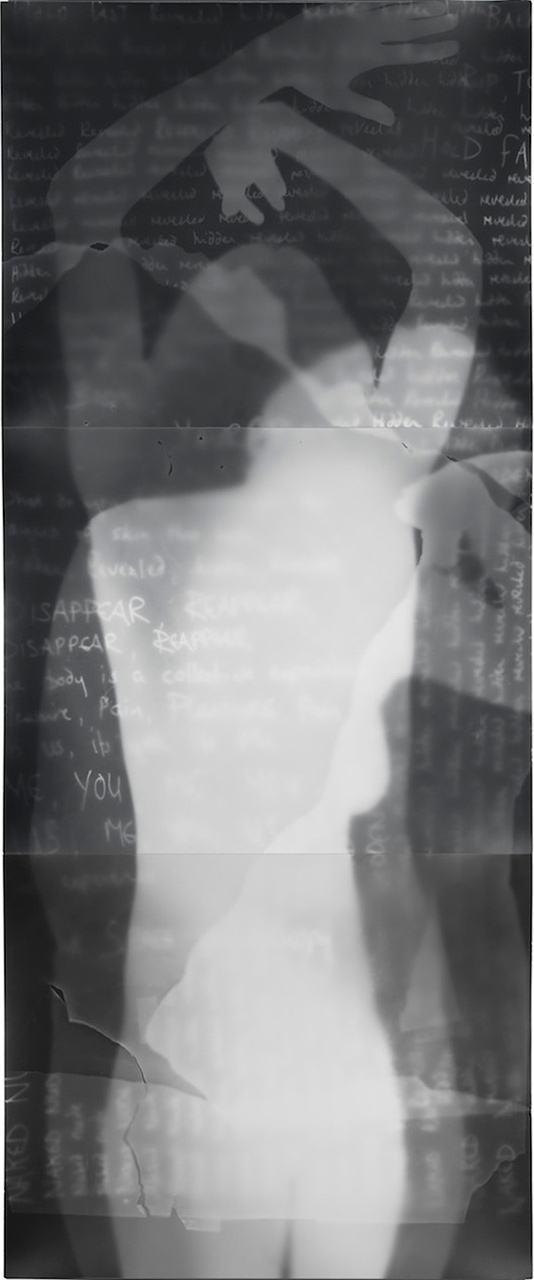

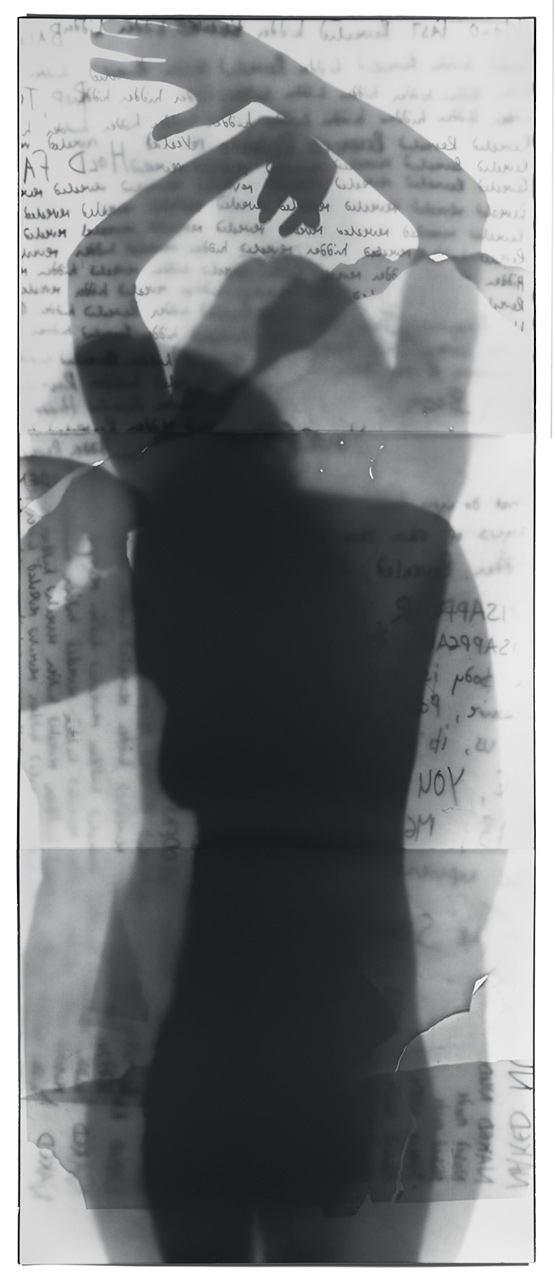

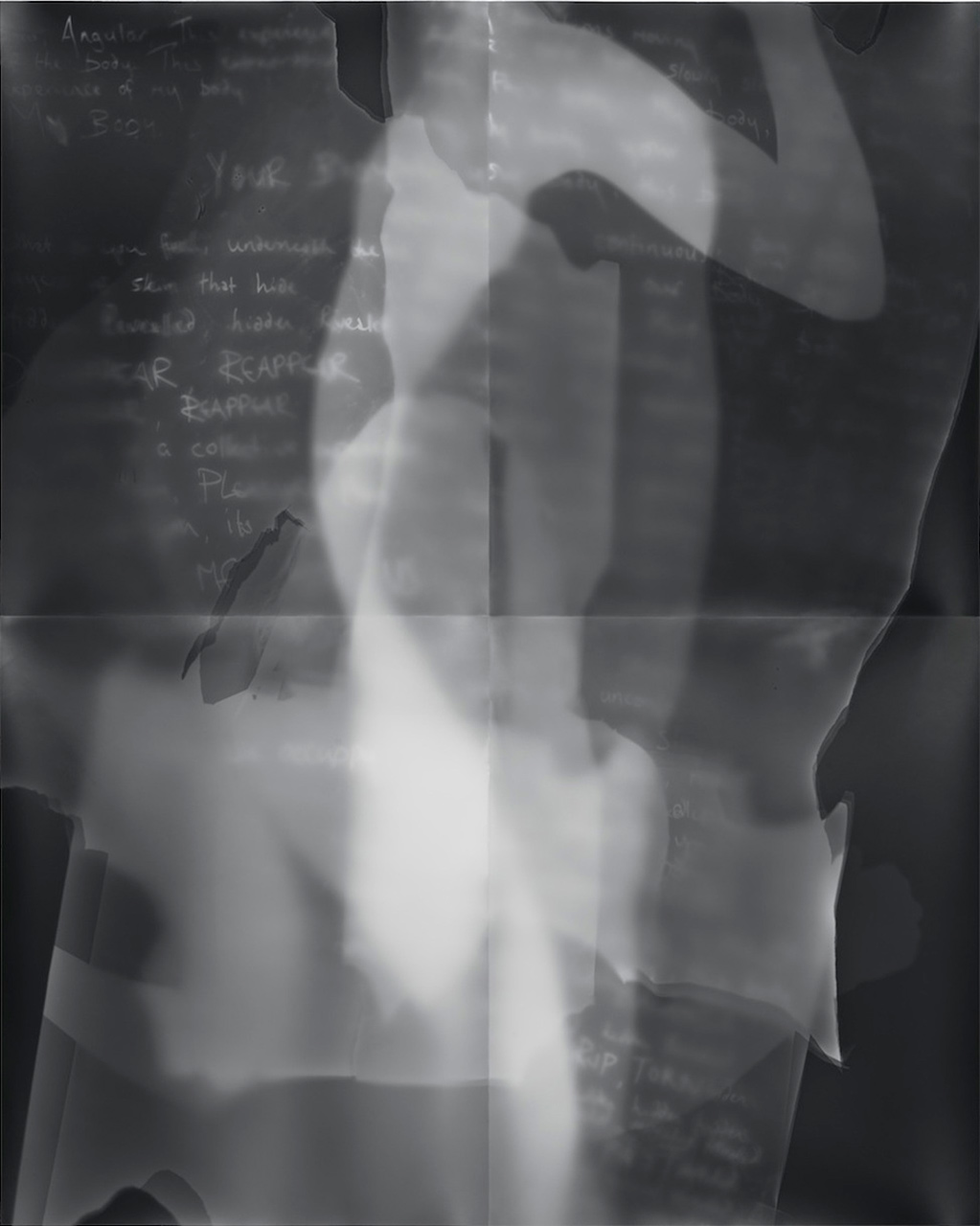

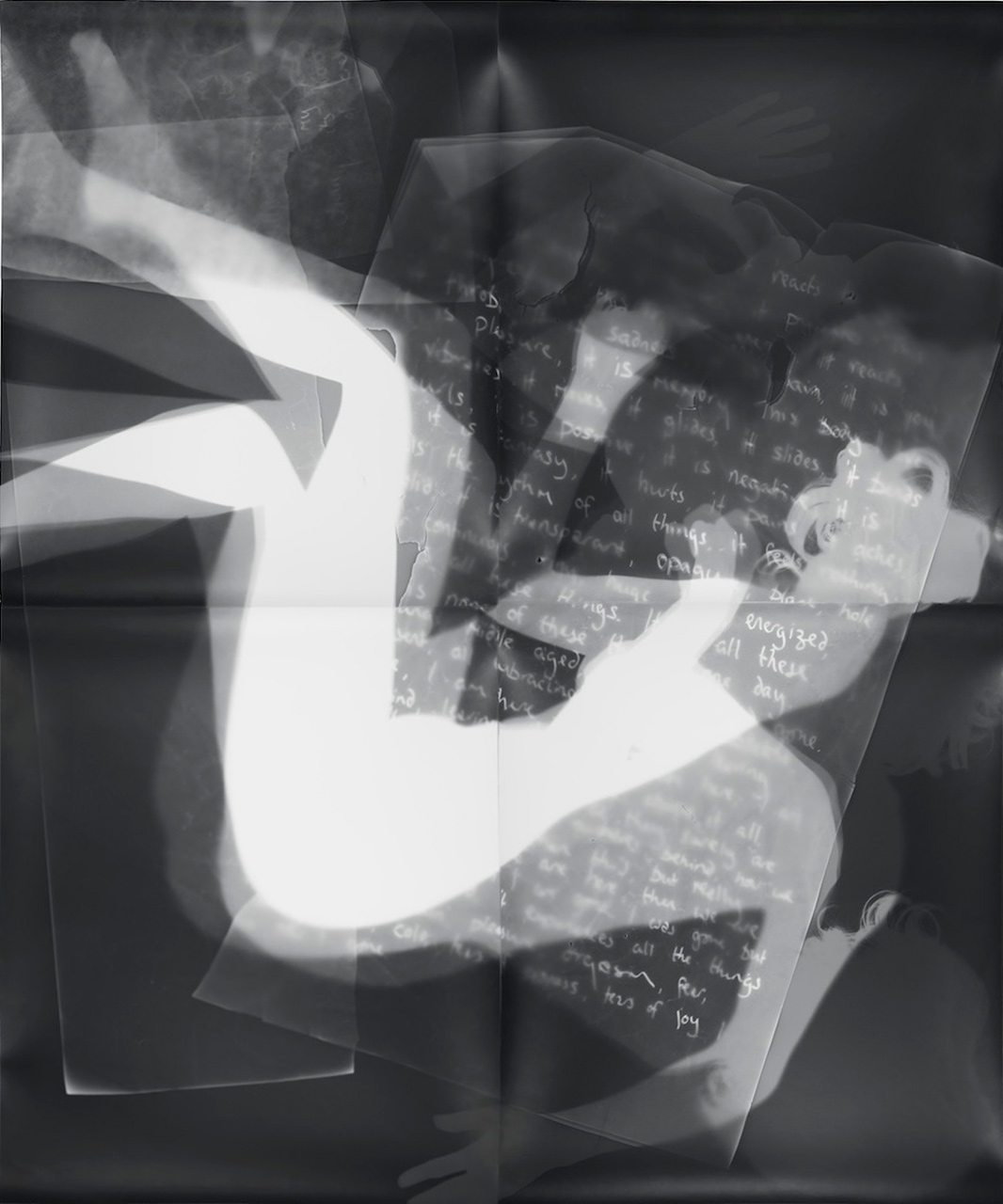

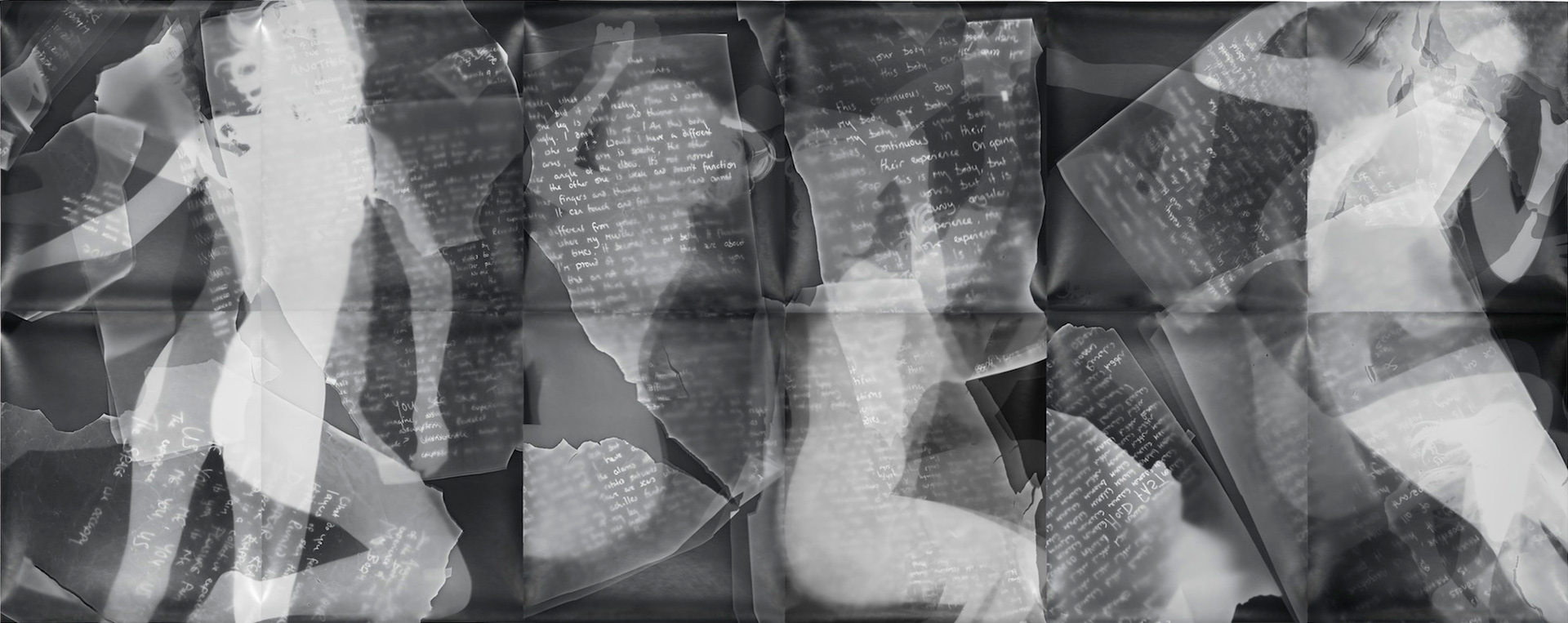

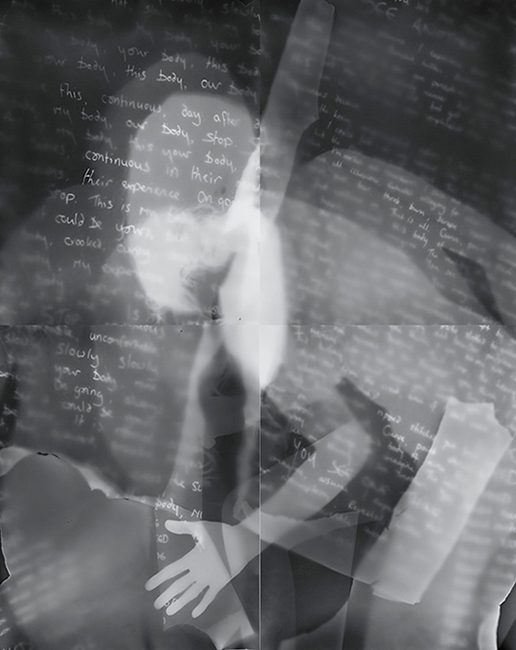

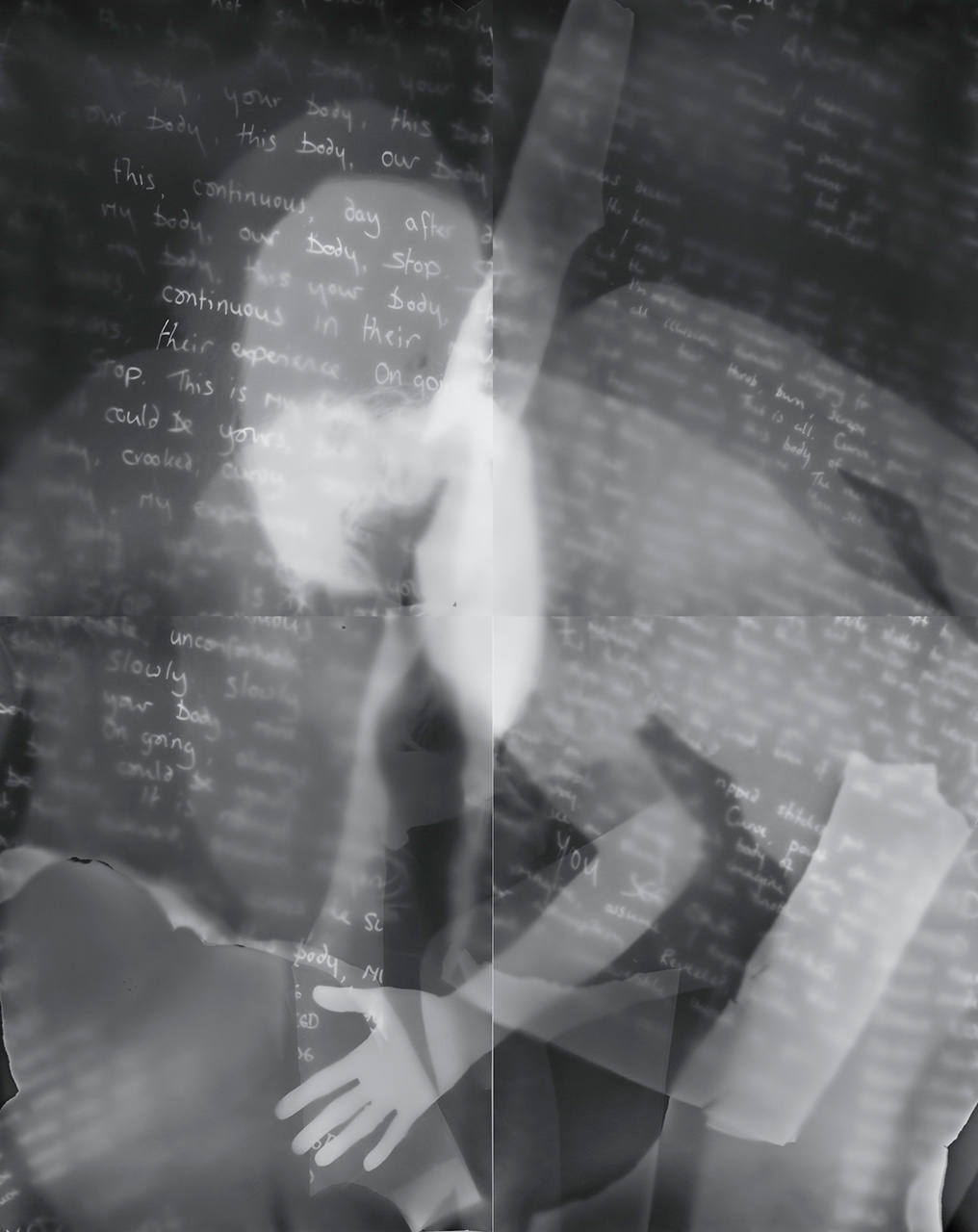

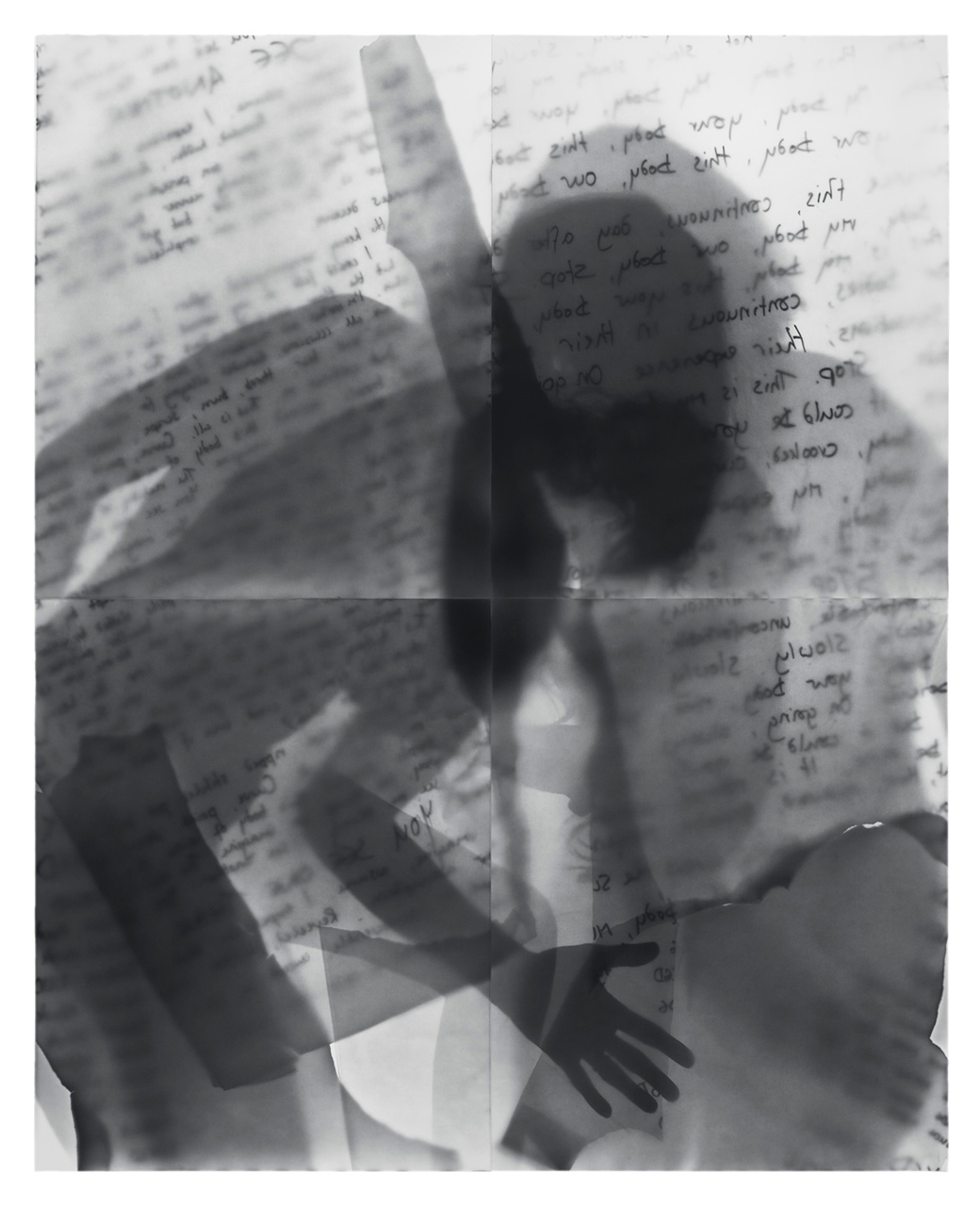

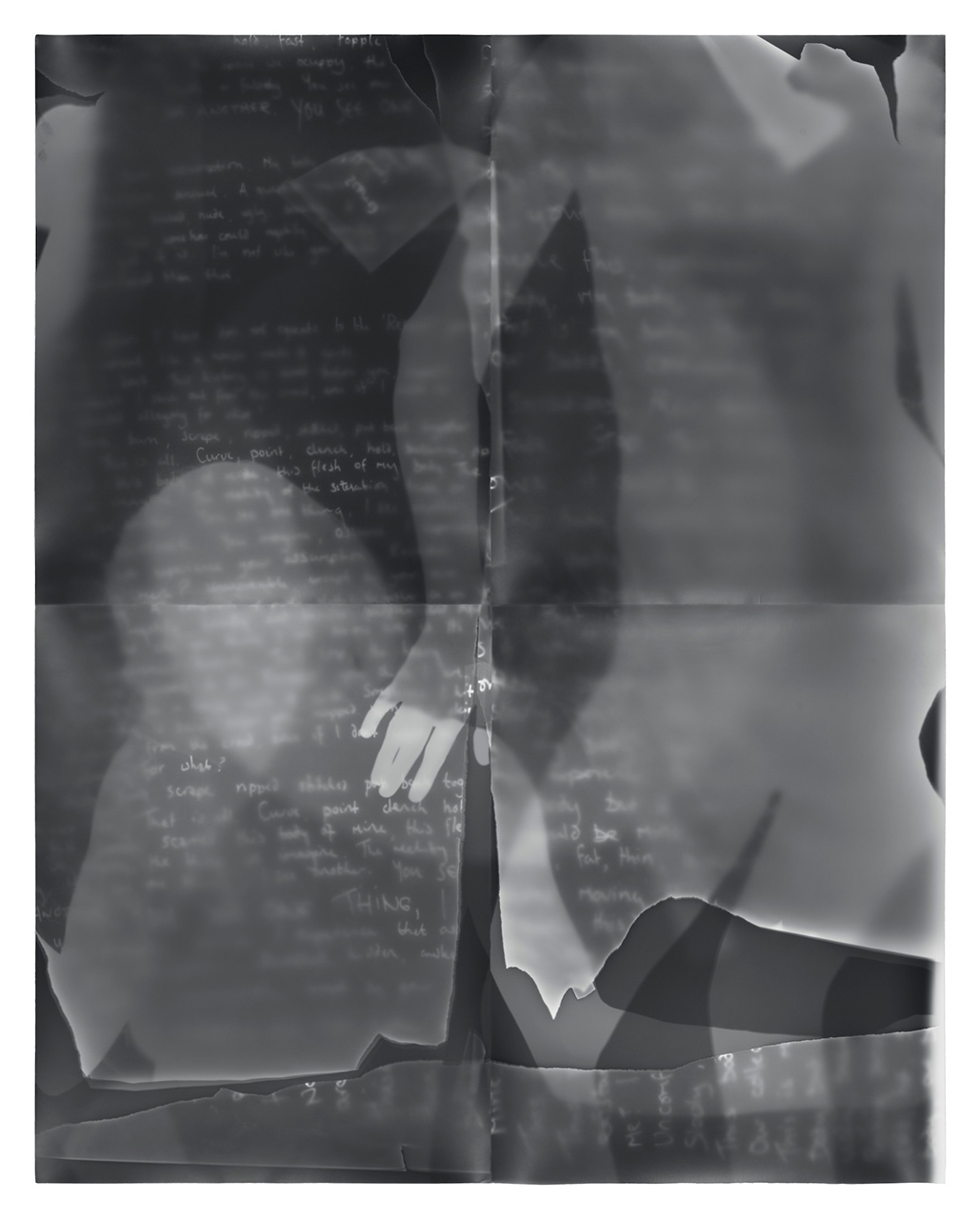

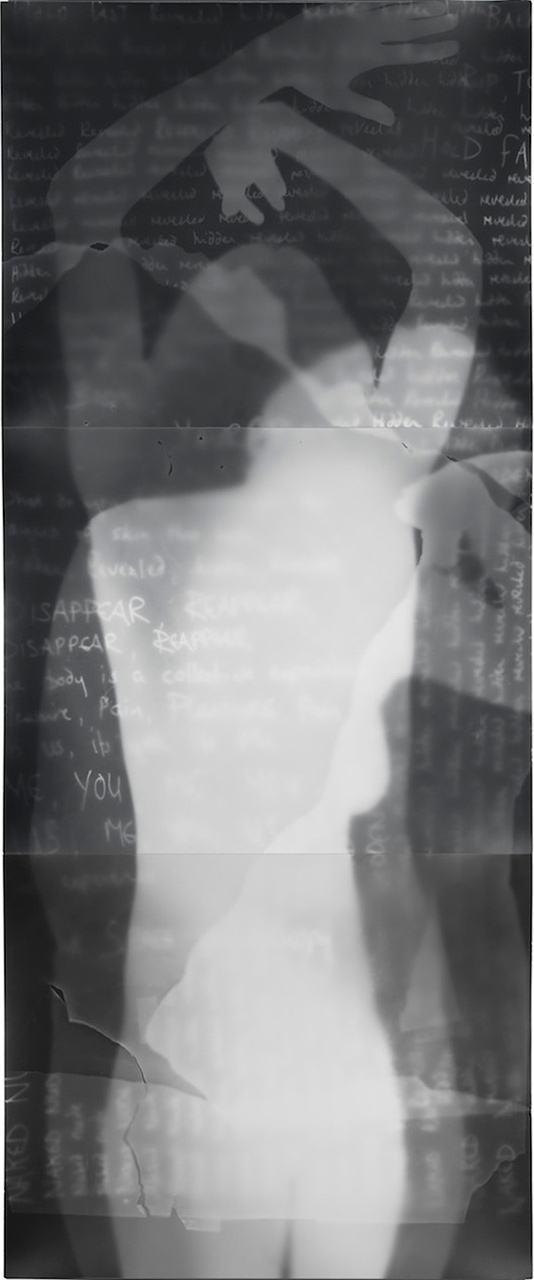

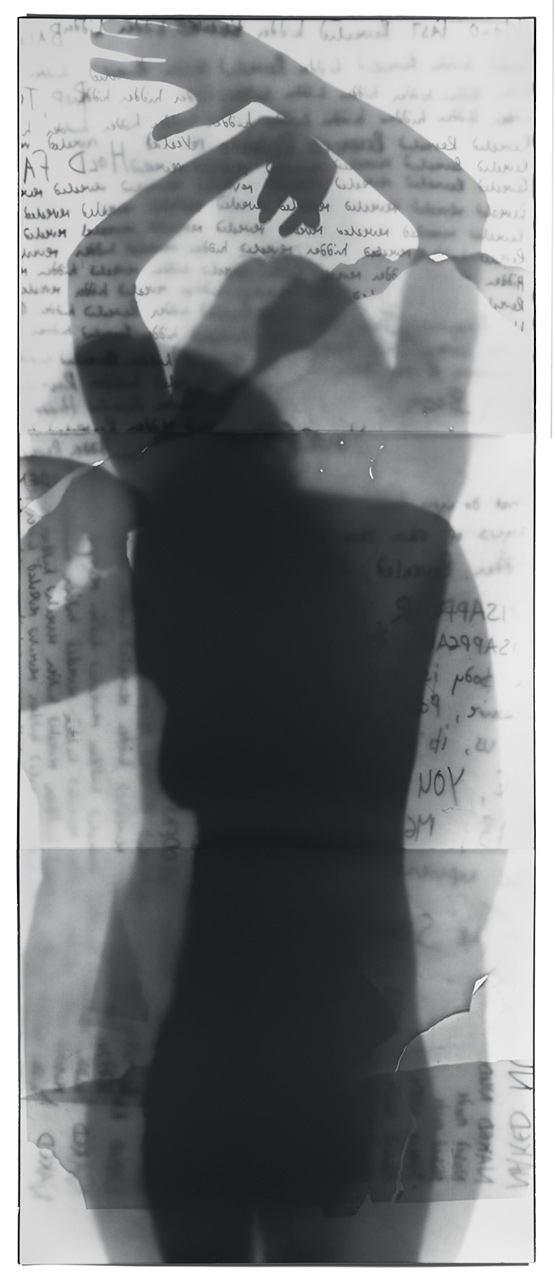

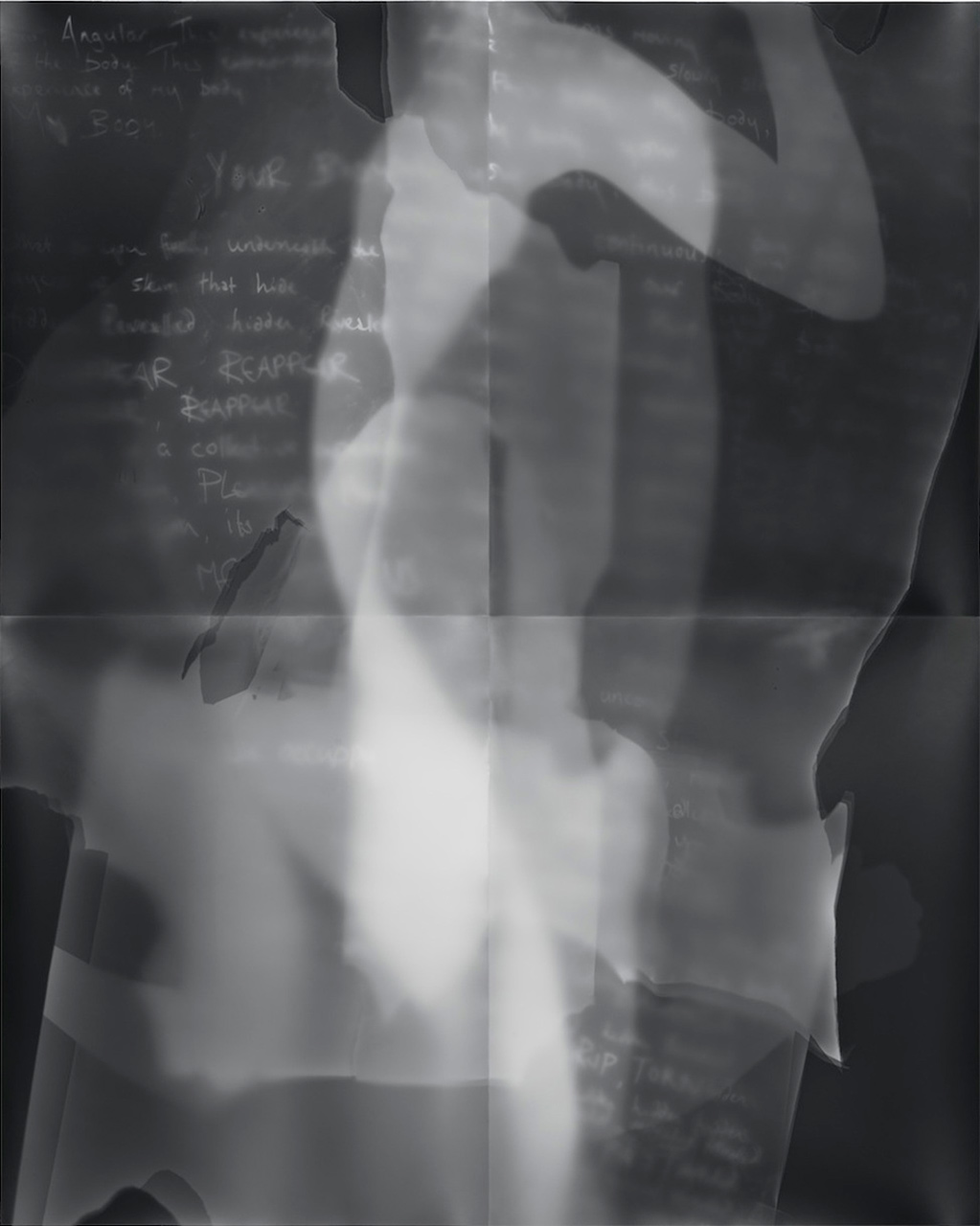

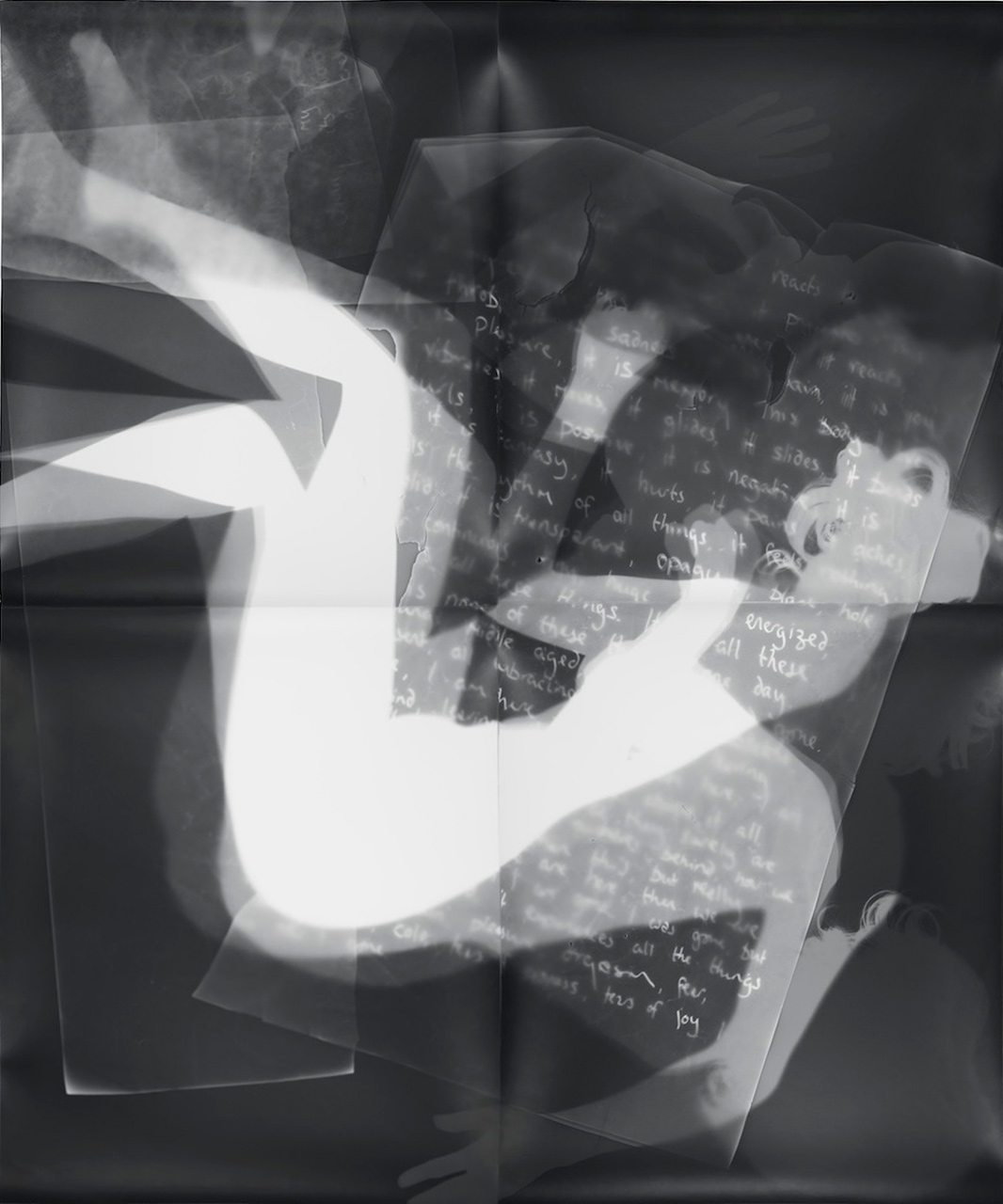

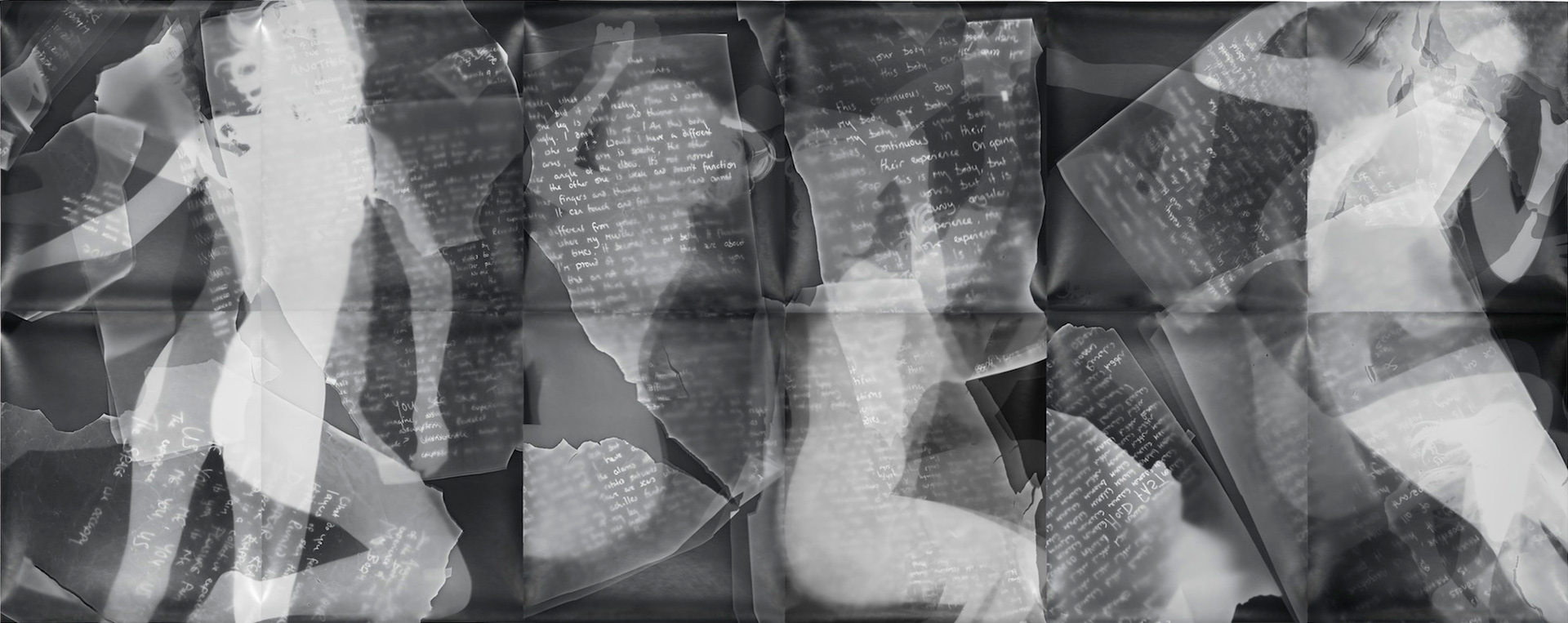

In 2012, I stepped out from behind the camera and, in the dark, placed my body onto photographic paper. In a few brief seconds of illumination, I left my mark. Made as if by magic through an alchemy of silver and light, here was evidence of my presence, witness to my physical self at a particular time and space. This fascination with the physical body, its sensations, its wholeness and with the traces we leave behind, stem from my own experience of having lived within a disabled body my whole life, learning to live with my own set of limitations and peculiarities, my own truths and fantasies.

I was inspired to make my large photograms after discovering small photograms of my hands and feet I had made many years ago (1996/97), during my Fine Art degree at Sheffield Hallam University in England. They had been made as part of a larger installation piece where I recreated the hospital spaces I had spent so much time visiting as a child. The linoleum floors, long corridors and bare walls I erected had the traces of myself in the form of these photograms laid down with liquid light.

Each photogram is a unique gelatin silver print made on semi-matt paper and toned in gold. I make the pieces in one step, by placing the sheets of photographic paper onto the floor of my darkened studio and laying vellum paper with my thoughts and words, relating to the experience of the body written upon them, some very personal others more general, on top of it. I use a strobe as my light source as I move across the paper to record my presence and then develop it in the darkroom. The resulting images are one of a kind pieces which I then tone with gold.

Although these photograms are unique in one sense, there is the feeling contained within these images, that my experience is one which is shared by everybody, mirroring the strange, puzzling and transient experience of the human body in each of the spaces we occupy.

Claire Gilliam (England, 1979). Lives and works in the United States since 1999. In 1997 she graduated form Sheffield Hallam University, UK with a Bachelor in Fine Arts and 2000 she completed the Professional Certificate in Photography at Rockport College, Maine. She has participated in the Independent Project Seminar at ICP in New York. Her work has been shown in Europe and the USA and is held in several private and public collections, including the ICP Library Print collection. To see more of her work go to: clairegilliam.com

Claire Gilliam (England, 1979). Lives and works in the United States since 1999. In 1997 she graduated form Sheffield Hallam University, UK with a Bachelor in Fine Arts and 2000 she completed the Professional Certificate in Photography at Rockport College, Maine. She has participated in the Independent Project Seminar at ICP in New York. Her work has been shown in Europe and the USA and is held in several private and public collections, including the ICP Library Print collection. To see more of her work go to: clairegilliam.com

In 2012, I stepped out from behind the camera and, in the dark, placed my body onto photographic paper. In a few brief seconds of illumination, I left my mark. Made as if by magic through an alchemy of silver and light, here was evidence of my presence, witness to my physical self at a particular time and space. This fascination with the physical body, its sensations, its wholeness and with the traces we leave behind, stem from my own experience of having lived within a disabled body my whole life, learning to live with my own set of limitations and peculiarities, my own truths and fantasies.

I was inspired to make my large photograms after discovering small photograms of my hands and feet I had made many years ago (1996/97), during my Fine Art degree at Sheffield Hallam University in England. They had been made as part of a larger installation piece where I recreated the hospital spaces I had spent so much time visiting as a child. The linoleum floors, long corridors and bare walls I erected had the traces of myself in the form of these photograms laid down with liquid light.

Each photogram is a unique gelatin silver print made on semi-matt paper and toned in gold. I make the pieces in one step, by placing the sheets of photographic paper onto the floor of my darkened studio and laying vellum paper with my thoughts and words, relating to the experience of the body written upon them, some very personal others more general, on top of it. I use a strobe as my light source as I move across the paper to record my presence and then develop it in the darkroom. The resulting images are one of a kind pieces which I then tone with gold.

Although these photograms are unique in one sense, there is the feeling contained within these images, that my experience is one which is shared by everybody, mirroring the strange, puzzling and transient experience of the human body in each of the spaces we occupy.

Claire Gilliam (England, 1979). Lives and works in the United States since 1999. In 1997 she graduated form Sheffield Hallam University, UK with a Bachelor in Fine Arts and 2000 she completed the Professional Certificate in Photography at Rockport College, Maine. She has participated in the Independent Project Seminar at ICP in New York. Her work has been shown in Europe and the USA and is held in several private and public collections, including the ICP Library Print collection. To see more of her work go to: clairegilliam.com

Claire Gilliam (England, 1979). Lives and works in the United States since 1999. In 1997 she graduated form Sheffield Hallam University, UK with a Bachelor in Fine Arts and 2000 she completed the Professional Certificate in Photography at Rockport College, Maine. She has participated in the Independent Project Seminar at ICP in New York. Her work has been shown in Europe and the USA and is held in several private and public collections, including the ICP Library Print collection. To see more of her work go to: clairegilliam.comAndré Gunthert

André Gunthert, "Conversational image: new uses of digital photography.", Etudes photographiques, n° 31, printemps 2014.

Nowadays we dislike the overwhelming amount of images, for we link this proliferation to the progress of reproducibility. But is the technical predictability the only parameter for this growth? This could be explained more satisfactorily in terms of more uses for photographs. In any case, this is what is suggested by the observation of connected uses.

The first period of the static websites was characterized as a "society of authors 14 ". In contrast, the abilities of symmetric interaction promoted by the Web 2.0 have lead to users describing the activity of on-line publications as a conversation 15 . Studied in detail by Pragmatics or Ethnomethodology, the oral exchange structured by the order of speaking is considered as one of the foundations of sociability. "That is where the child learns to speak, where the stranger socializes by entering a new group (...), where the social relationship is built, where the system of the language is formed and transformed 16 ."

The ordered, symmetrical, open, and cumulative interaction that characterizes instant messaging or on-line exchanges is similar to the egalitarian sociability of conversation. As Jean-Samuel Beuscart, Dominique Cardon, Nicolas Pissard and Christophe Prieur note in their study on Flickr, the integration of the image in this economy represents a remarkable evolution of these features 17 . Rather than having conversations about pictures, they say, the Web has favored having conversations using pictures.

However, the ability of using an image as a message wasn't born with digital devices. For example, this attribute is also offered by an illustrated postcard, which has seen a marked development since the end of the 10th century. If we agree to add the correspondence as a conversational genre, the association of the image allows us to see a primitive state of this creation, following a much slower rhythm. Even if the industrial production requires us to turn to standard ways or situations, the usefulness of postcards provide precious examples of the archeology of the visual conversation.

In its digital version, it appears at the core of e-mail and on-line forums, and then in multimedia messaging services, or MMS, that appeared with the first camera phones. The Sharp J-SH04, released in Japan in October 2000 at a cost of $500, works with the J-Phone network, which allows sharing pictures among users.

In the middle of the 2000's an intermediate stage was born with "monoblogging", where sharing pictures taken with a camera phone in a blog was the predecessor of the instant publication in social networks. Therefore, if there are two different uses for the connected image, taking one from the private conversation, and the other one from the public or semi-public conversation, it is equally important to notice the permeability between the different spaces, which is encouraged by the digital fluidity.

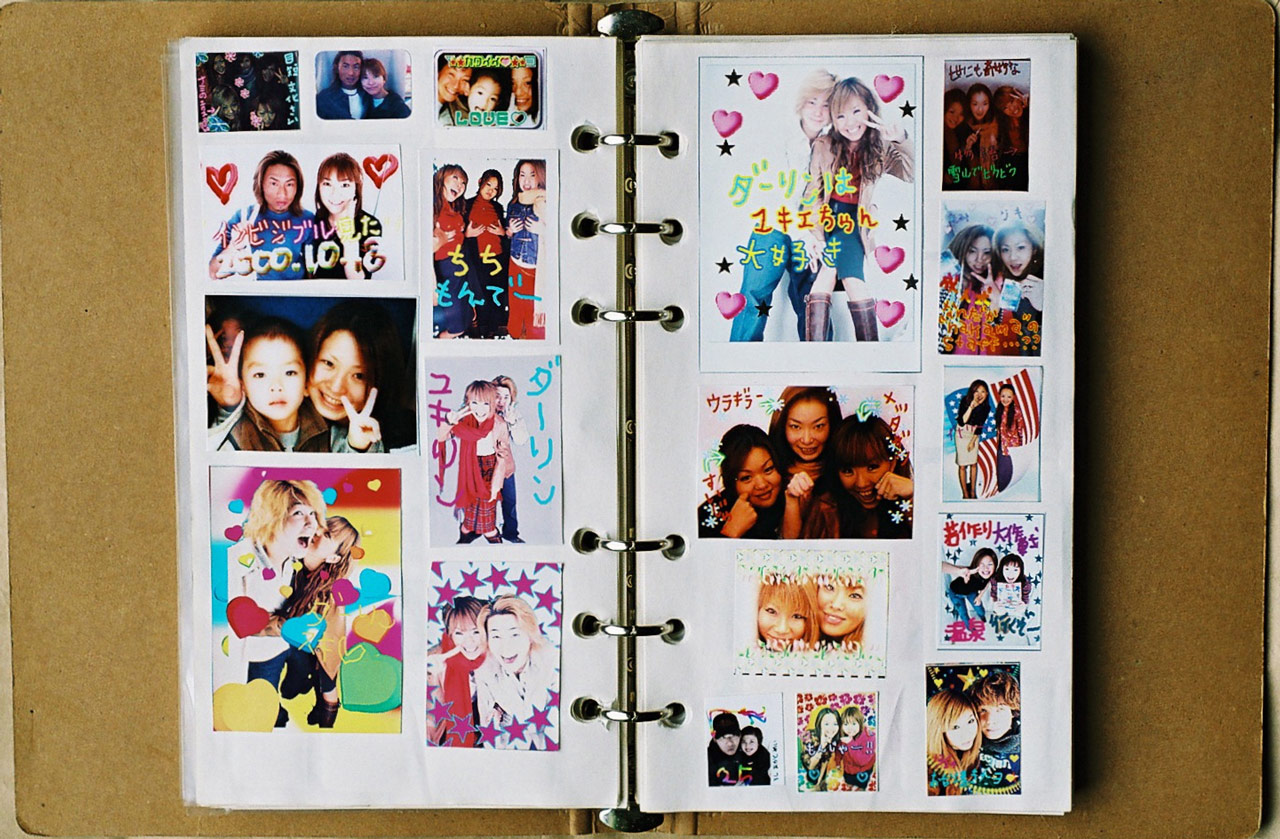

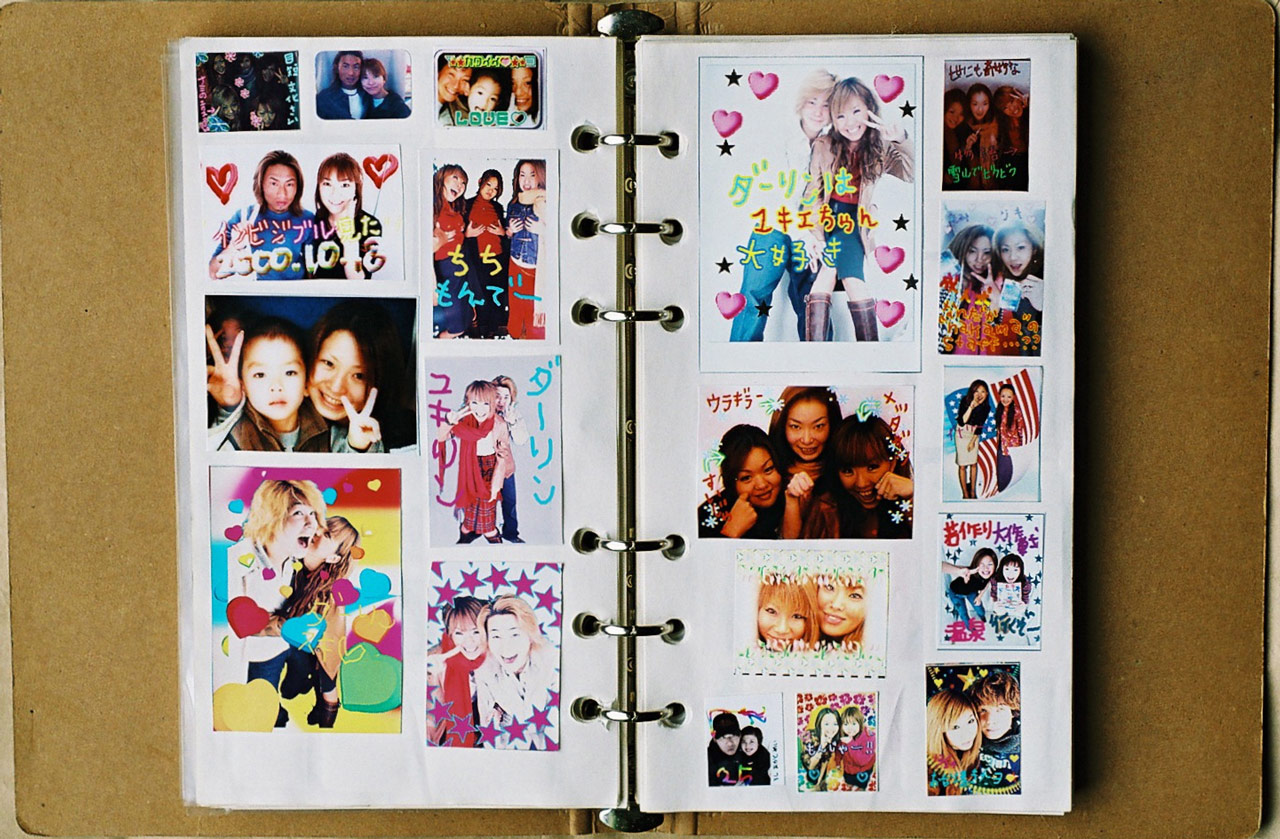

Fig. 3. Album of purikura, Tokyo, 2003(courtesy of Claude Estebe).

Recently baptized as "selfie", a form of contextual self-photograph, this type of picture is possibly the oldest identifiable practice of the connected image. The birth of camera phones in Japan is placed in the wake of the phenomenon, purikura 18, that can be attached multiple decorations with the goal of becoming collectible items (see fig. 3). The first camera phone model by Sharp has a small mirror in front, an original scheme to make taking self-portraits easier. The promotional images from that time leave no room for questions: the camera was conceived by the manufacturer to allow users to take pictures of them at an arm's length by using a lens of short focal length.

If these features were only imagined as a gadget, it is a more dramatic way to manifest the transformation of the uses provided by connected images. On July 7th, 2005, between 8:50 and 9:47am, four bombs transported by terrorists blew up three subway stations and a bus in London, resulting in 56 dead and 700 injured. While the media was not able to enter the subway, Sky News broadcasted at 12:35pm an image taken very near the attack: it was a picture taken at 9:25am with a camera phone of user Adam Stacey in the corridor connecting to King's Cross, and sent as an electronic message to many recipients (see fig.4).

Fig. 4. Photograph of Adam Stacey by Kevin Ward, London subway, July 07, 2005 (CC licence).

Although this image shows a face, it is by no means a portrait in the sense granted by pictorial tradition. And, even if the circumstances caused its public diffusion 19 , its initial share belonged to a private conversation. Due to the immediacy of its communication, the photo of Adam Stacey, taken on his demand by a friend who was with him in order to keep his next of kin informed, has, first of all, a useful function as a way of relaying quickly a fact.

If the documentary vocation is an integral part of the history of visual recording, this generally concerns specialized uses, such as scientific, media or industrial. In terms of personal photography, the use of the image continues being essentially symbolic: the preservation of memories or the writing of family history.

There are examples of practical uses, such as the documentation of an assessment of loss for an insurance company, that have been observed since the beginning of the 20th century. But they continue to be discreet, they don't matter to the observers and they aren't described in any history or sociology texts on amateur photography.

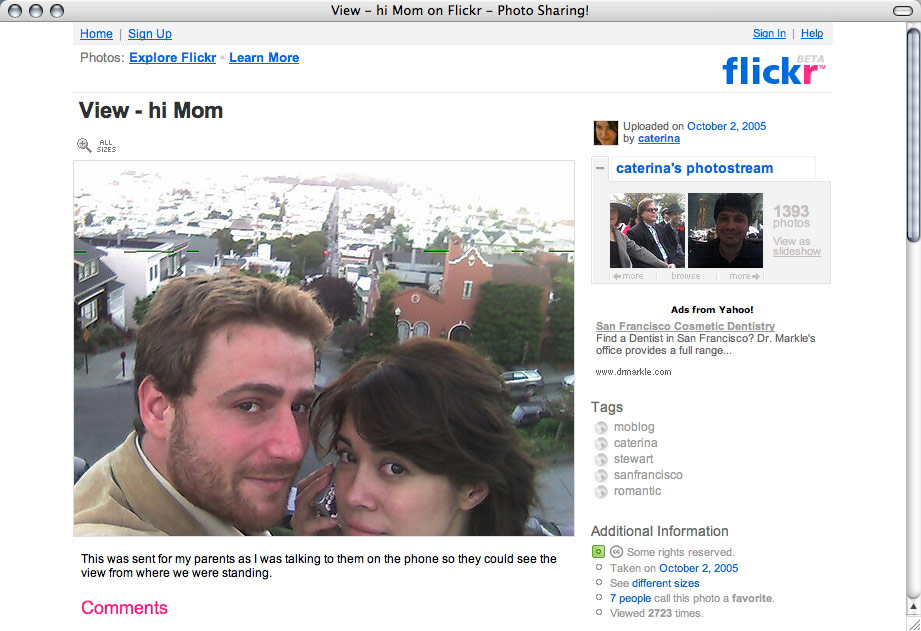

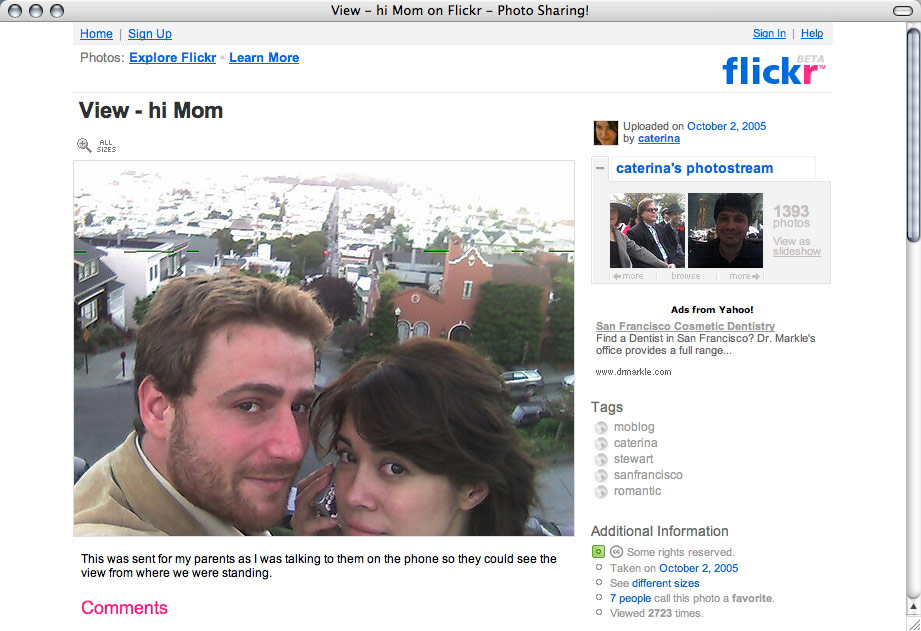

However, by making images available faster, some technical innovations such as the instant development proposed by Polaroid have competed to improve the practical use of pictures, and have made room for a wide range of recording uses. This also holds true for the instant transmission of the connected image, which gives photography access to the universe of communication. We can see a significant example of these current applications in the selfie of co-founders of Flickr, Stewart Butterfield and Caterina Fake, from October 2005. Titled " Hi Mom ", the picture published on Flickr has an accompanying explanation: "Sent to my parents while I spoke to them on the telephone so they could share the view of the environment where we were" ( see fig.5 ).

Fig. 5. " Hi Mom", selfie of Stewart Butterfield and Caterina Fake, co-founders of Flickr, October 2005 (CC licence).

The available studies on new communicative practices witness an unprecedented extension of the utilitarian applications 20 . By associating the visual dimension with shared data, the image allows to supply information about a situation (an arrival to or presence in a place, the use of a mean of transportation...), a check of appearance (an outfit test, the result of a haircut, physical aspect...), but also countless practical information, such as the purchase of a product, the composition of a dish, the state of a building, etc. Photography allows us to record all of this or transmit it faster than a written message 21 . The connected image lends itself particularly to the regular exchange of signals destined to maintain an effective, friendly or romantic relationship. It can also serve for political or military goals, such as the pictures of gatherings during the Arab Spring, immediately distributed to get people to join the demonstrations 22 .

The extreme variety of these applications shows a fast adaptation to connected tools, as well as the development of a new skill: the ability to translate a situation visually, a way to be able to offer a summary, often personal or playful, a way to reinterpret reality that reminds us of "The Practice of Everyday Life" by Michel de Certeau 23 .

14 Bernard Stiegler, " Situations technologiques de l’autorité cognitive à l’ère de la désorientation ", the conferences of the seminar " Technologies Cognitives et Environnements de Travail ", May 12th, 1998, ( quoted in Valérie Beaudouin, De la publication à la conversation . Lecture et écriture électroniques , Réseaux n° 116, 2002, p. 225).

15 Valérie Beaudouin, "De la publication à la conversation. Lecture et écriture électroniques", Réseaux , n° 116, 2002, p. 199-225.

16 Lorenza Mondada, "La question du contexte en ethnométhodologie et en analyse conversationnelle", Verbum , 28-2/3, 2006 [2008] (I thank Jonathan Larcher for his invaluable indications).

17 Jean-Samuel Beuscart, Dominique Cardon, Nicolas Pissard and Christophe Prieur, "Pourquoi partager mes photos de vacances avec des inconnus? Les usages de Flickr", Réseaux , n° 154/2, 2009, p. 91-129.

18 Jon Wurtzel, "Taking pictures with your phone", 18 September 2001, BBC News ( http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/1550622.stm). Developed by Altus and Sega, the first purikura cabins appeared in Tokyo in 1995.

19 André Gunthert, "Tous journalistes ? Les attentats de Londres ou l'intrusion des amateurs", in Gianni Haver (dir.), Press photo. Usages et pratiques , Lausanne, éd. Antipodes, 2009, p. 215- 225 (on line : http://www.arhv.lhivic.org/index.php/2009/03/19/956).

20 Olivier Aïm, Laurence Allard, Joëlle Menrath, Hécate Vergopoulos, "Vie intérieure et vie relationnelle des individus connectés. Une enquête ethnographique", French Telecoms Federation, slide show, September 2013 (on line: http://www.fftelecoms.org/sites/fftelecoms.org/files/contenus_lies/vie_interieure_vie_relationnelle_mai_2013.pdf).

21 According to ComScore, 14.3% of European smart phones owners (that is 155 million people in August 2013) have sent the picture of a product on sale to a close relation in order to get information or to ask for details, a slightly higher percentage of the total of sent SMS or calls (14%) with the same purpose (Ayaan Mohamud, "1 in 7 European Smartphone Owners Make Online Purchases via their Device", ComScore, Octobre 21st, 2013 (http://www.comscore.com/Insights/Press_Releases/2013/10/1_in_7_European_Smartphone_Owners_Make_Online_Purchases_via_their_Device).

22 Azyz Amami, "Photographier la révolution tunisienne" (memo at the symposium "Photographie, internet et réseaux sociaux", Rencontres d'Arles, July 8th, 2011), L'Atelier des icônes, July 9th, 2011 (audio, http://culturevisuelle.org/icones/1860).

23 Michel de Certeau, L’Invention du quotidien, (1) Arts de faire (1980), Paris, Gallimard, 1990

André Gunthert (Francia, 1961). Lives and works in France. He works as a researcher in cultural history and visual studies, holds a PhD in Art History and is an associate professor at the EHESS (School for Higher Studies in Social Sciences). Gunthert is also the director of the Laboratory of Contemporary Visual History (LHIVIC) and the founder of the digital journals Photographic studies and Visual Culture. He is currently carrying out research into the new uses of the digital image. His writings on visual culture can be consulted in his blog: L'Atelier des icônes.

André Gunthert (Francia, 1961). Lives and works in France. He works as a researcher in cultural history and visual studies, holds a PhD in Art History and is an associate professor at the EHESS (School for Higher Studies in Social Sciences). Gunthert is also the director of the Laboratory of Contemporary Visual History (LHIVIC) and the founder of the digital journals Photographic studies and Visual Culture. He is currently carrying out research into the new uses of the digital image. His writings on visual culture can be consulted in his blog: L'Atelier des icônes.

[core_state] => 1 [core_access] => 1 [core_metadata] => {"robots":"","author":"André Gunthert","rights":"","xreference":""} [core_created_user_id] => 839 [core_created_by_alias] => [core_created_time] => 2014-06-01 17:00:00 [core_images] => {"image_intro":"images\/categories\/zonezero-3\/ensayos.andre_gunthert.2.jpg","float_intro":"","image_intro_alt":"","image_intro_caption":"","image_fulltext":"images\/categories\/zonezero-3\/ensayos.andre_gunthert.2.jpg","float_fulltext":"","image_fulltext_alt":"","image_fulltext_caption":""} [core_modified_time] => 2015-04-21 18:51:14 [core_language] => en-GB [core_catid] => 42 [core_publish_up] => 2014-06-01 17:00:00 [core_publish_down] => 0000-00-00 00:00:00 [content_type_title] => Article [router] => ContentHelperRoute::getArticleRoute [author] => [author_email] => [link] => index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=147:andre-gunthert-conversational-picture-2&catid=42&lang=en-GB [displayDate] => 2014-06-01 17:00:00 [event] => stdClass Object ( [afterDisplayTitle] => [beforeDisplayContent] => [afterDisplayContent] => ) [text] =>

André Gunthert, "Conversational image: new uses of digital photography.", Etudes photographiques, n° 31, printemps 2014.

Nowadays we dislike the overwhelming amount of images, for we link this proliferation to the progress of reproducibility. But is the technical predictability the only parameter for this growth? This could be explained more satisfactorily in terms of more uses for photographs. In any case, this is what is suggested by the observation of connected uses.

The first period of the static websites was characterized as a "society of authors 14 ". In contrast, the abilities of symmetric interaction promoted by the Web 2.0 have lead to users describing the activity of on-line publications as a conversation 15 . Studied in detail by Pragmatics or Ethnomethodology, the oral exchange structured by the order of speaking is considered as one of the foundations of sociability. "That is where the child learns to speak, where the stranger socializes by entering a new group (...), where the social relationship is built, where the system of the language is formed and transformed 16 ."

The ordered, symmetrical, open, and cumulative interaction that characterizes instant messaging or on-line exchanges is similar to the egalitarian sociability of conversation. As Jean-Samuel Beuscart, Dominique Cardon, Nicolas Pissard and Christophe Prieur note in their study on Flickr, the integration of the image in this economy represents a remarkable evolution of these features 17 . Rather than having conversations about pictures, they say, the Web has favored having conversations using pictures.

However, the ability of using an image as a message wasn't born with digital devices. For example, this attribute is also offered by an illustrated postcard, which has seen a marked development since the end of the 10th century. If we agree to add the correspondence as a conversational genre, the association of the image allows us to see a primitive state of this creation, following a much slower rhythm. Even if the industrial production requires us to turn to standard ways or situations, the usefulness of postcards provide precious examples of the archeology of the visual conversation.

In its digital version, it appears at the core of e-mail and on-line forums, and then in multimedia messaging services, or MMS, that appeared with the first camera phones. The Sharp J-SH04, released in Japan in October 2000 at a cost of $500, works with the J-Phone network, which allows sharing pictures among users.

In the middle of the 2000's an intermediate stage was born with "monoblogging", where sharing pictures taken with a camera phone in a blog was the predecessor of the instant publication in social networks. Therefore, if there are two different uses for the connected image, taking one from the private conversation, and the other one from the public or semi-public conversation, it is equally important to notice the permeability between the different spaces, which is encouraged by the digital fluidity.

Fig. 3. Album of purikura, Tokyo, 2003(courtesy of Claude Estebe).

Recently baptized as "selfie", a form of contextual self-photograph, this type of picture is possibly the oldest identifiable practice of the connected image. The birth of camera phones in Japan is placed in the wake of the phenomenon, purikura 18, that can be attached multiple decorations with the goal of becoming collectible items (see fig. 3). The first camera phone model by Sharp has a small mirror in front, an original scheme to make taking self-portraits easier. The promotional images from that time leave no room for questions: the camera was conceived by the manufacturer to allow users to take pictures of them at an arm's length by using a lens of short focal length.

If these features were only imagined as a gadget, it is a more dramatic way to manifest the transformation of the uses provided by connected images. On July 7th, 2005, between 8:50 and 9:47am, four bombs transported by terrorists blew up three subway stations and a bus in London, resulting in 56 dead and 700 injured. While the media was not able to enter the subway, Sky News broadcasted at 12:35pm an image taken very near the attack: it was a picture taken at 9:25am with a camera phone of user Adam Stacey in the corridor connecting to King's Cross, and sent as an electronic message to many recipients (see fig.4).

Fig. 4. Photograph of Adam Stacey by Kevin Ward, London subway, July 07, 2005 (CC licence).

Although this image shows a face, it is by no means a portrait in the sense granted by pictorial tradition. And, even if the circumstances caused its public diffusion 19 , its initial share belonged to a private conversation. Due to the immediacy of its communication, the photo of Adam Stacey, taken on his demand by a friend who was with him in order to keep his next of kin informed, has, first of all, a useful function as a way of relaying quickly a fact.

If the documentary vocation is an integral part of the history of visual recording, this generally concerns specialized uses, such as scientific, media or industrial. In terms of personal photography, the use of the image continues being essentially symbolic: the preservation of memories or the writing of family history.

There are examples of practical uses, such as the documentation of an assessment of loss for an insurance company, that have been observed since the beginning of the 20th century. But they continue to be discreet, they don't matter to the observers and they aren't described in any history or sociology texts on amateur photography.

However, by making images available faster, some technical innovations such as the instant development proposed by Polaroid have competed to improve the practical use of pictures, and have made room for a wide range of recording uses. This also holds true for the instant transmission of the connected image, which gives photography access to the universe of communication. We can see a significant example of these current applications in the selfie of co-founders of Flickr, Stewart Butterfield and Caterina Fake, from October 2005. Titled " Hi Mom ", the picture published on Flickr has an accompanying explanation: "Sent to my parents while I spoke to them on the telephone so they could share the view of the environment where we were" ( see fig.5 ).

Fig. 5. " Hi Mom", selfie of Stewart Butterfield and Caterina Fake, co-founders of Flickr, October 2005 (CC licence).

The available studies on new communicative practices witness an unprecedented extension of the utilitarian applications 20 . By associating the visual dimension with shared data, the image allows to supply information about a situation (an arrival to or presence in a place, the use of a mean of transportation...), a check of appearance (an outfit test, the result of a haircut, physical aspect...), but also countless practical information, such as the purchase of a product, the composition of a dish, the state of a building, etc. Photography allows us to record all of this or transmit it faster than a written message 21 . The connected image lends itself particularly to the regular exchange of signals destined to maintain an effective, friendly or romantic relationship. It can also serve for political or military goals, such as the pictures of gatherings during the Arab Spring, immediately distributed to get people to join the demonstrations 22 .

The extreme variety of these applications shows a fast adaptation to connected tools, as well as the development of a new skill: the ability to translate a situation visually, a way to be able to offer a summary, often personal or playful, a way to reinterpret reality that reminds us of "The Practice of Everyday Life" by Michel de Certeau 23 .

14 Bernard Stiegler, " Situations technologiques de l’autorité cognitive à l’ère de la désorientation ", the conferences of the seminar " Technologies Cognitives et Environnements de Travail ", May 12th, 1998, ( quoted in Valérie Beaudouin, De la publication à la conversation . Lecture et écriture électroniques , Réseaux n° 116, 2002, p. 225).

15 Valérie Beaudouin, "De la publication à la conversation. Lecture et écriture électroniques", Réseaux , n° 116, 2002, p. 199-225.

16 Lorenza Mondada, "La question du contexte en ethnométhodologie et en analyse conversationnelle", Verbum , 28-2/3, 2006 [2008] (I thank Jonathan Larcher for his invaluable indications).

17 Jean-Samuel Beuscart, Dominique Cardon, Nicolas Pissard and Christophe Prieur, "Pourquoi partager mes photos de vacances avec des inconnus? Les usages de Flickr", Réseaux , n° 154/2, 2009, p. 91-129.

18 Jon Wurtzel, "Taking pictures with your phone", 18 September 2001, BBC News ( http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/1550622.stm). Developed by Altus and Sega, the first purikura cabins appeared in Tokyo in 1995.

19 André Gunthert, "Tous journalistes ? Les attentats de Londres ou l'intrusion des amateurs", in Gianni Haver (dir.), Press photo. Usages et pratiques , Lausanne, éd. Antipodes, 2009, p. 215- 225 (on line : http://www.arhv.lhivic.org/index.php/2009/03/19/956).

20 Olivier Aïm, Laurence Allard, Joëlle Menrath, Hécate Vergopoulos, "Vie intérieure et vie relationnelle des individus connectés. Une enquête ethnographique", French Telecoms Federation, slide show, September 2013 (on line: http://www.fftelecoms.org/sites/fftelecoms.org/files/contenus_lies/vie_interieure_vie_relationnelle_mai_2013.pdf).

21 According to ComScore, 14.3% of European smart phones owners (that is 155 million people in August 2013) have sent the picture of a product on sale to a close relation in order to get information or to ask for details, a slightly higher percentage of the total of sent SMS or calls (14%) with the same purpose (Ayaan Mohamud, "1 in 7 European Smartphone Owners Make Online Purchases via their Device", ComScore, Octobre 21st, 2013 (http://www.comscore.com/Insights/Press_Releases/2013/10/1_in_7_European_Smartphone_Owners_Make_Online_Purchases_via_their_Device).

22 Azyz Amami, "Photographier la révolution tunisienne" (memo at the symposium "Photographie, internet et réseaux sociaux", Rencontres d'Arles, July 8th, 2011), L'Atelier des icônes, July 9th, 2011 (audio, http://culturevisuelle.org/icones/1860).

23 Michel de Certeau, L’Invention du quotidien, (1) Arts de faire (1980), Paris, Gallimard, 1990

André Gunthert (Francia, 1961). Lives and works in France. He works as a researcher in cultural history and visual studies, holds a PhD in Art History and is an associate professor at the EHESS (School for Higher Studies in Social Sciences). Gunthert is also the director of the Laboratory of Contemporary Visual History (LHIVIC) and the founder of the digital journals Photographic studies and Visual Culture. He is currently carrying out research into the new uses of the digital image. His writings on visual culture can be consulted in his blog: L'Atelier des icônes.

André Gunthert (Francia, 1961). Lives and works in France. He works as a researcher in cultural history and visual studies, holds a PhD in Art History and is an associate professor at the EHESS (School for Higher Studies in Social Sciences). Gunthert is also the director of the Laboratory of Contemporary Visual History (LHIVIC) and the founder of the digital journals Photographic studies and Visual Culture. He is currently carrying out research into the new uses of the digital image. His writings on visual culture can be consulted in his blog: L'Atelier des icônes.

[id] => 147 [language] => en-GB [catid] => 42 [jcfields] => Array ( ) ) 1

André Gunthert

André Gunthert, "Conversational image: new uses of digital photography.", Etudes photographiques, n° 31, printemps 2014.

The connected photography can't exist without a recipient. Beyond a first-degree utility, the communicative systems also give images the function of engaging in a conversation or a dialogical unity. This way they acquire a second-degree utility as expressive forms. In private exchanges, the protection of the messages and the familiarity of the participants encourages implicit contents, contextual games, or transgression24. In social networks, the public visibility enables collective practices: a participative interpretation through a series of commentaries generated by an iconic source, or a choral construction, by taking and repeating a motive transformed in a meme25, that shows the social productivity of visual forms (see fig. 6).

Fig. 6. Picture published in Facebook and its accompanying conversation, February 2012 (Hipstamatic, courtesy of Catherine Harmant).

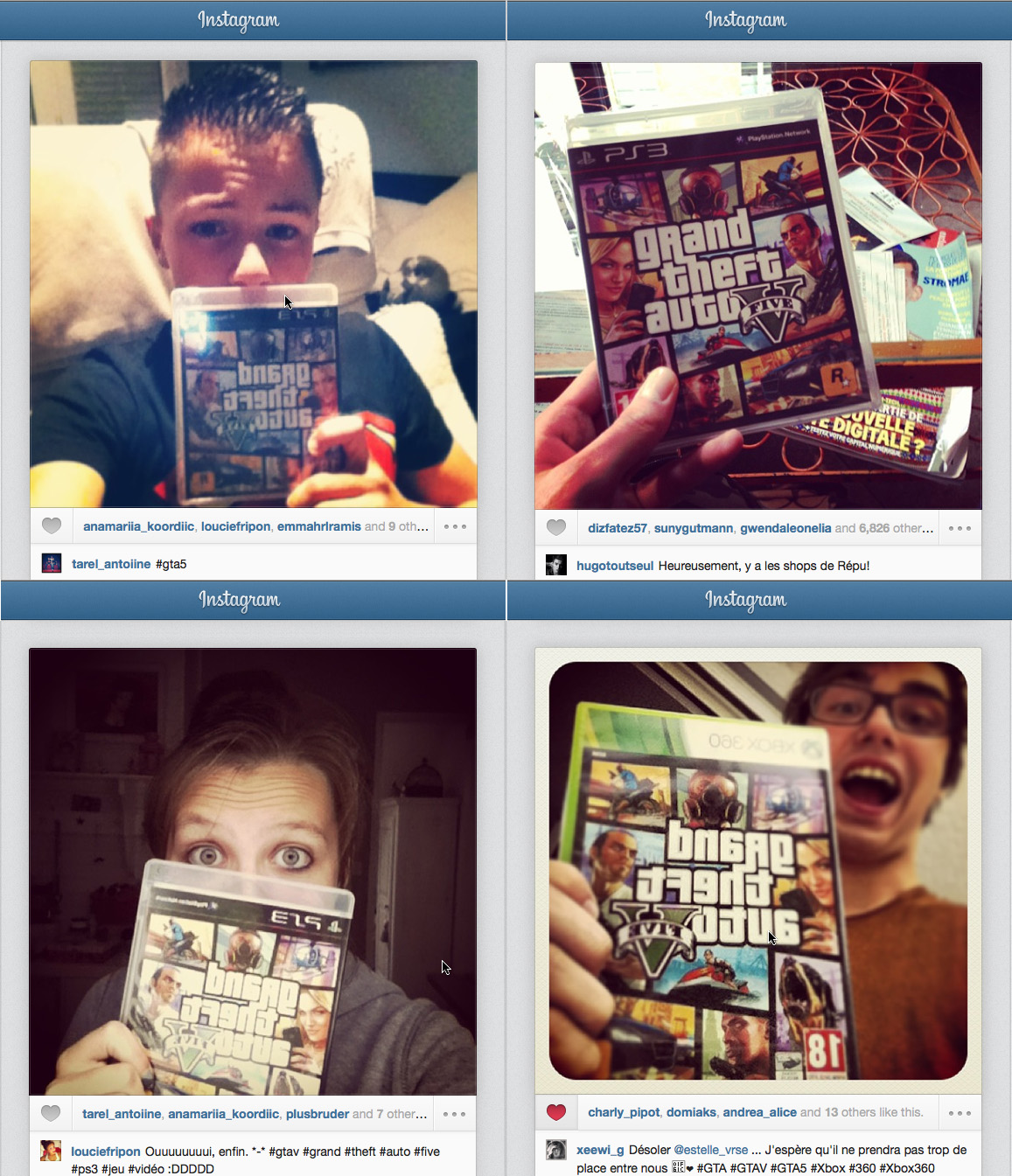

As a sign of its success, we see a tendency to an autonomy of the visual conversation, through tools of collection and rebroadcast of images, such as Tumblr (2007) or Pinterest (2010), where retaking and circulating the content are the main resources of validation. A platform dedicated to the connected image, such as Instagram (2010), allows helping in the creation of collaborative answers to a common event, a meteorological phenomenon or a cultural occasion, welcomed by a photographic production whose display takes the aspect of a collective game (see fig 7).

Fig. 7. Collection of selfies published in Instagram on the release date of the video game Grand Theft Auto 5, September 2013 (priv. coll.).

Conversely, integrating images in the conversation makes them benefit from the validation systems that reward participating in social networks. The exposition and public appreciation of self-produced photography grant it a critical, aesthetic or social legitimacy. They also favor the presence of an autonomous interpretation exercise, that seems necessary to reduce the ambiguity of the images26.

By sharing broadly the new visual practices, the big social networks also give them an unprecedented visibility and contribute to their viral propagation. A satirical video published in December 2012 at the College Humor site redirects a song by Nickelback to make fun of the trends in connected photography27. Pictures of meals, feet, cats, airplane wings, filters, selfies, etc.: the clip draws up a long list of themes repeated on the timelines of Facebook and Twitter. This excellent parody shows that placing these visual forms together is beautiful and correctly identified as numerous autonomous patterns.

Fig. 8. Contextual self-photograph of a pair of feet published on Facebook, Rio de Janeiro, August 2012 (priv. coll.).

By examining the characteristics of private photographies from the early 20th century, Marin Dacos noticed that a large part of album photos reproduced the models of studio photography or publicity published on the papers28. By granting a group of visual practices a certificate of recognition, the video of College Humor suggests that from now on we help in a reversal phenomenon. As with memes or recommendations, the private iconography benefits from the transition that sees social networks take the place of traditional media in terms of cultural developers. Through them, the vernacular productions achieve a rank of identifiable and reproducible models.

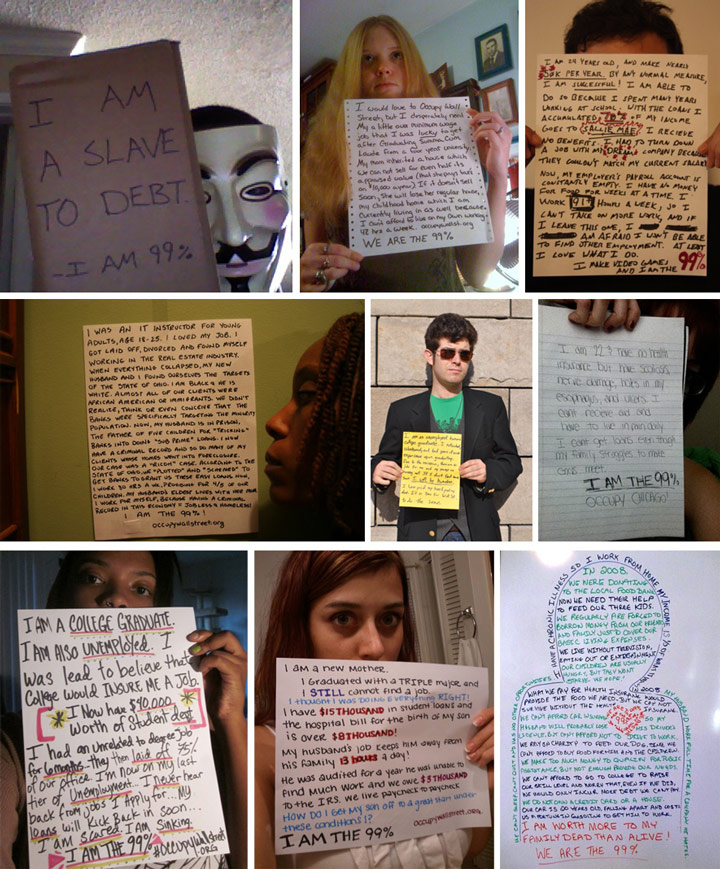

This new visibility manifests particularly through negative reactions. This way, in 2013 we were able to see "selfie" being selected as word of the year by the editors of the Oxford Dictionary due to a share of media commentaries that denounced that the Web was saturated with this narcissistic exercise of connected self-portraits29. By criticizing an excessive presence, this reception is witnessing an standard that the genre is in the process of achieving.

When Michel de Certeau was trying to get close to the "ordinary culture", he expressed his discomfort at facing the "almost invisibility" of practices "that were hardly signaled by their own products30". On the contrary, the visibility that the main social networks give the individual expression reverse the dynamic of the production of the standard. In the past, the popular classes copied whatever the stars did. From this point forward, celebrities and the big names of this world are the ones who reproduce the models issued by the general public by conforming themselves to the rules of the selfie.

Fig. 9. Roberto Schmidt, photograph of a selfie with a smartphone by Danish Prime Minister Helle Thorning--‐Schmidt next to Barack Obama and David Cameron during the Nelson Mandela memorial service, December 11th, 2013 (AFP).

We can regret this development of a "barbaric taste" —to quote Kant's expression retaken by Bourdieu31— by social networks, the intermediaries of the ordinary culture. But isn't bringing good and bad taste into opposition the wrong way of address the problem? While the visual or musical practices encourage an unexpected approach inspired on art history, that places first the creativity of the authors and supposes a self-sufficiency for the expressive motivation, the test of language forms proposes a neutral description of the process. But, unlike the creation, or even the expression, the conversation is an autonomous domain with a communicative and social utility32. In this context, the new visual practices shouldn't be analyzed only from an aesthetic point of view.

The victory of use over content is particularly obvious with Snapchat (2011), a mobile application of visual messaging that offers the possibility of deleting the picture a few seconds after consulting it.

This feature of protected conversations through the fugacity of an iconic message has become a success for this medium with the young population, who uses it at a rhythm similar to SMS. By programming the disappearance of the image, Snapchat adds a playful dimension, as well as a supplementary freedom for the user, promoting an informal or relaxed use. The application clearly illustrates the desertion of the territory of labor and elaboration in favor of a conversation in real time. Already broadly detectable by most social networks, this shift suggests the description of ordinary practices of the image as a new language.

As with the arrival of the cinema or the television, the arrival of the conversational image transforms deeply our visual practices. Photography used to be an art and a medium. We are living the moment when it is accessing the universality of a language. Integrated by multipurpose tools for connected systems, the visual forms have begun to engage greatly in both private and public conversations. Whatever individuals can do for their production and interpretation contributes to a fast evolution of formats and uses. The visibility conferred by social networks speeds their diffusion and gives birth to self-produced standards. The appropriation of the visual language helps reinvent everyday life. Moreover, the extension of the utility of images states specific problems to be analyzed. If the semiotics of visual forms had until now leaned on a narrow register of assumed contexts, identifiable by a unique formal test, the variety of these new applications is imposing a change towards an ethnography of uses.

24 Tim Kindberg, Mirjana Spasojevic, Rowanne Fleck, Abigail Sellen, "I Saw This and Thought of You. Some Social Uses of Camera Phones", Extended Abstracts of the Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI 2005), 2005, ACM Press, p. 1545-1548 ; Gaby David, "The Intimacy of Strong Ties in Mobile Visual Communication", Culture Visuelle, April 22th, 2013 (http://culturevisuelle.org/corazonada/2013/04/22/the-intimacy-of-strong-ties-in-mobile visualcommunication/).