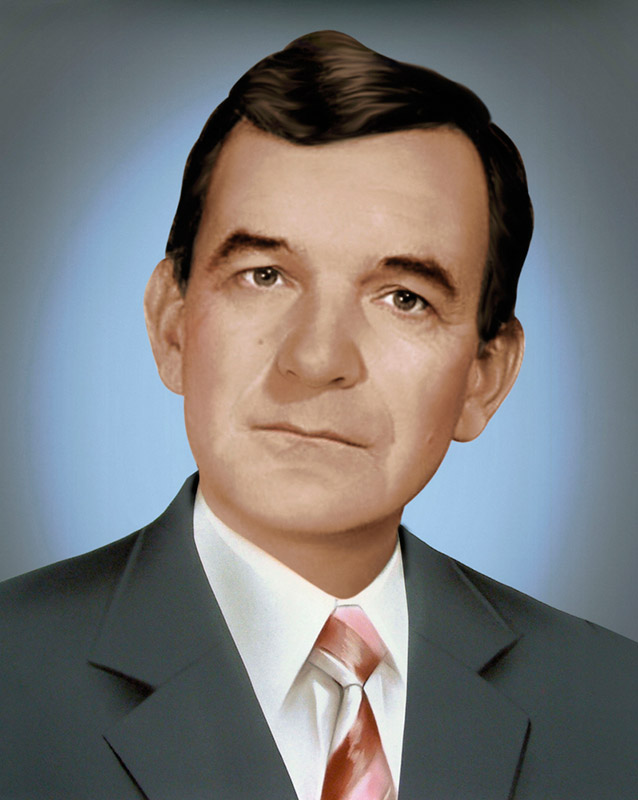

Diego Goldberg

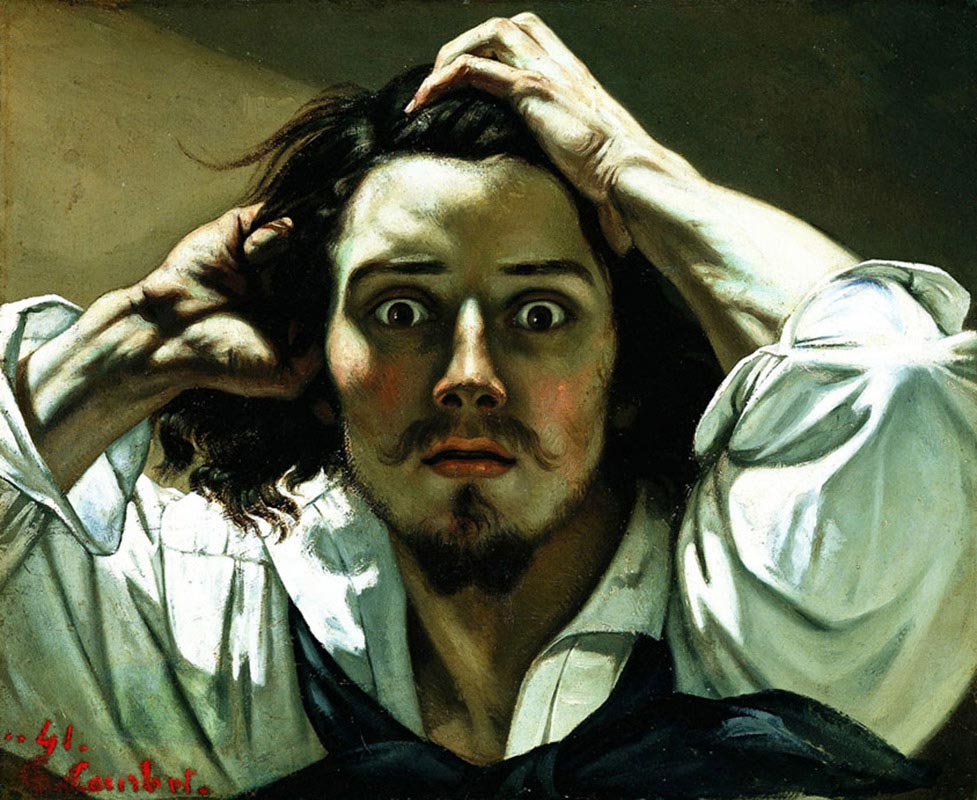

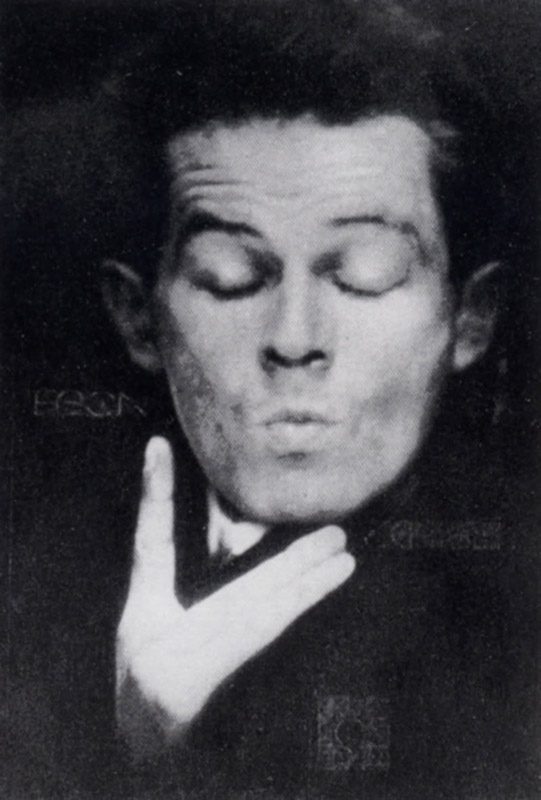

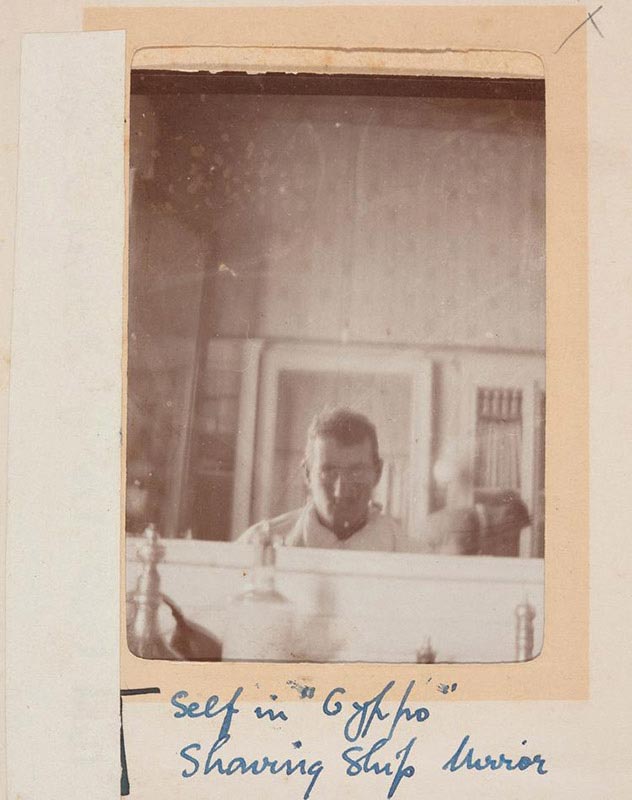

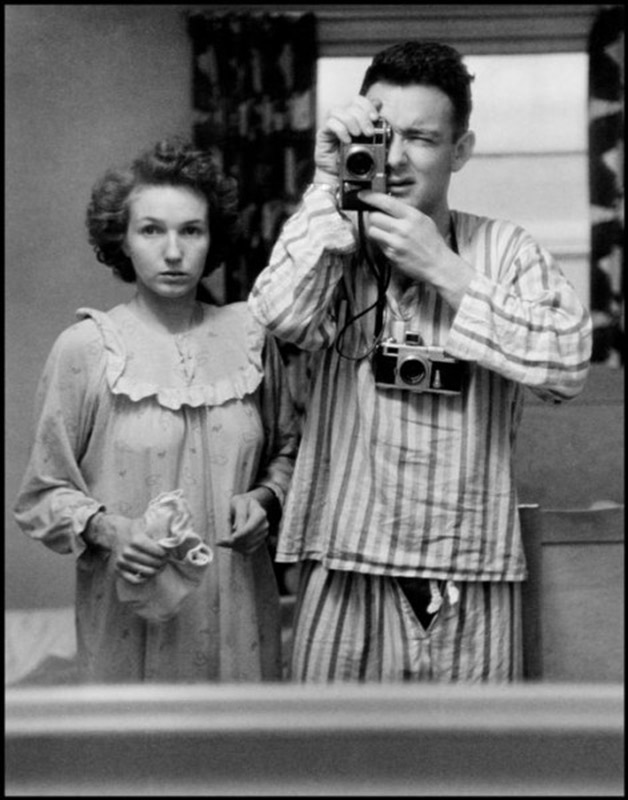

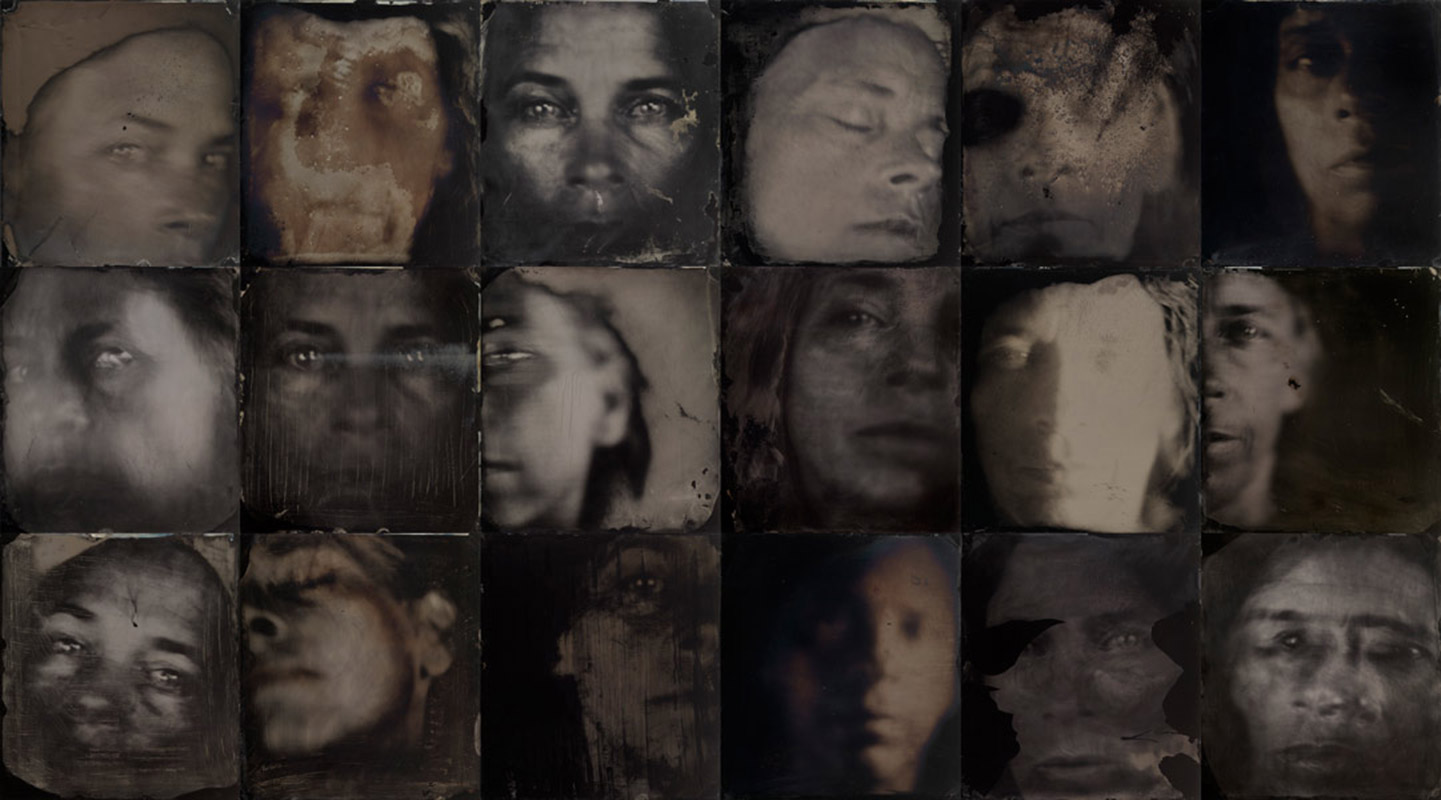

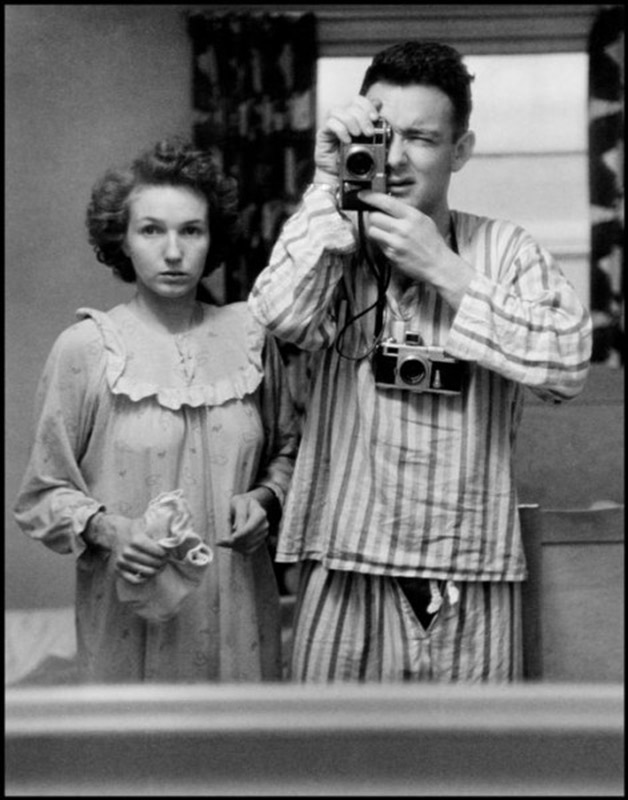

On June 17th, every year, the family goes through a private ritual:

we photograph ourselves to stop, for a fleeting moment, the arrow of time passing by.

Diego Goldberg (Argentina, 1946). Lives and works in Argentina. He has taken part in group and solo exhibitions. Among other distinctions, Goldberg has won the Gold Medal 1998 from the Society of Publications Design; the Award of Merit 1998 from the Art Directors Club of New York for The Arrow of Time; second prize at the World Press Photo (Amsterdam, 1983) for Chile Ten Years After the Coup; and First Prize in the New York Press Award 1981 for Alphonse D’Amato, commissioned by the New York Times Magazine. He also won the FNPI (Gabriel García Márquez Foundation) Prize in 2006 for the Pursuing a dream. Diego can be reached at: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. and you can visit his website.

Diego Goldberg (Argentina, 1946). Lives and works in Argentina. He has taken part in group and solo exhibitions. Among other distinctions, Goldberg has won the Gold Medal 1998 from the Society of Publications Design; the Award of Merit 1998 from the Art Directors Club of New York for The Arrow of Time; second prize at the World Press Photo (Amsterdam, 1983) for Chile Ten Years After the Coup; and First Prize in the New York Press Award 1981 for Alphonse D’Amato, commissioned by the New York Times Magazine. He also won the FNPI (Gabriel García Márquez Foundation) Prize in 2006 for the Pursuing a dream. Diego can be reached at: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. and you can visit his website.

On June 17th, every year, the family goes through a private ritual:

we photograph ourselves to stop, for a fleeting moment, the arrow of time passing by.

Diego Goldberg (Argentina, 1946). Lives and works in Argentina. He has taken part in group and solo exhibitions. Among other distinctions, Goldberg has won the Gold Medal 1998 from the Society of Publications Design; the Award of Merit 1998 from the Art Directors Club of New York for The Arrow of Time; second prize at the World Press Photo (Amsterdam, 1983) for Chile Ten Years After the Coup; and First Prize in the New York Press Award 1981 for Alphonse D’Amato, commissioned by the New York Times Magazine. He also won the FNPI (Gabriel García Márquez Foundation) Prize in 2006 for the Pursuing a dream. Diego can be reached at: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. and you can visit his website.

Diego Goldberg (Argentina, 1946). Lives and works in Argentina. He has taken part in group and solo exhibitions. Among other distinctions, Goldberg has won the Gold Medal 1998 from the Society of Publications Design; the Award of Merit 1998 from the Art Directors Club of New York for The Arrow of Time; second prize at the World Press Photo (Amsterdam, 1983) for Chile Ten Years After the Coup; and First Prize in the New York Press Award 1981 for Alphonse D’Amato, commissioned by the New York Times Magazine. He also won the FNPI (Gabriel García Márquez Foundation) Prize in 2006 for the Pursuing a dream. Diego can be reached at: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. and you can visit his website.

Alejandro Malo

Cloud Phenomena of Maloja. Film by Arnold Fanck, 1924

Landscape, long before being image, was literature and longing. Since ancient times, almost every civilization led an educated class that longed to return to the simple life of the countryside, back to nature with its deeper order and less troubled appearance. In the West, despite its widespread tradition against the city life and akin to recover the rural simplicity, it is only during the Renaissance that the joy of those running away from the maddening crowds turns into the full enjoyment of nature, first in poetry and only afterwards as a growing presence in paintings. In the East, at least since China’s Tang Dynasty, a fertile dialogue is established around the landscape between poetry and painting, and the genre develops very soon and evolves in multiple aspects.

Centuries later, while other visual media were confronted by the emergence of photography to take in and emphasize the subjectivity of their gaze over this topic, photographic landscapes devote their attention to exoticism or the magnificence of natural views and offered a deceptive closeness to a naturalist interpretation. The romantic vision of nature took root strongly across images ranging from the Bisson brothers to Ansel Adams. In them, beauty was something external to be captured in each shot, a reserve where solitude was a regained innocence and open spaces offered an inexhaustible source of peacefulness for the contemplative eye under the changing light’s mantle.

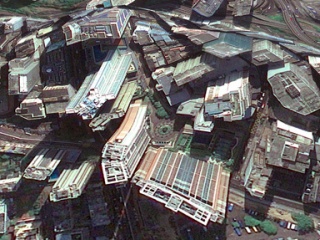

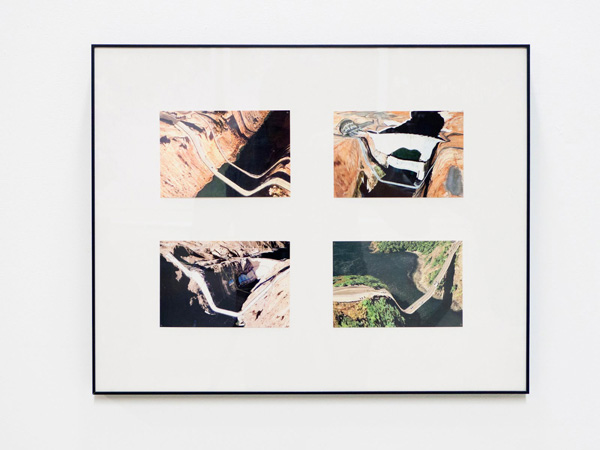

Gradually, as these perspectives became advertising and marketing leitmotifs, this genre had to be reinvented and new possibilities sought elsewhere. Already in 1975, with the exhibition New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-Altered Landscape, it became clear that human intervention was inseparable from our new perception of landscape. The aseptic style of the authors gathered in this exhibition, considered almost forensic and where the emotional charge seemed absent, caused the sensation of being somehow close to a crime scene’s lingering memories, but devoid of its dramatic charge. During the following years, some authors, with a similar methodology but against this trend, looked after landscapes as representation of their own temperament, metaphor of an inner life that finds in the environment an affinity and a strong individual expressive capacity. Finally, photography assumed the same subjectivity of other means. As an example, Hiroshi Sugimoto wrote about his Seascapes: "Every time I view the sea, I feel a calming sense of security, as if visiting my ancestral home". In that phrase, anyone can guess a sort of poetic inclination and a strong artistic weight that facilitates dialogue with paintings, as was done in 2012 by exposing this series with Mark Rothko’s work.

However, Eden’s innocence became impossible in a world where human presence outreach tainted glaciers and forests with the same nonchalance. In the second half of the twentieth century, the landscape was transformed from man facing nature, to be a metaphor for our own humanity and, at the same time, scene of our fears, hopes and tragedies. We read as landscape every place where a scenario simulates an open space, no matter whether an emotional or conceptual projection of ourselves, but also we read it under the titanic action of mining, between the megalopolis’ streets or against the inventiveness of major transformation projects. Hybridization of genres has allowed the unreal calm of sensationalist scenes as in Fernando Brito’s pictures and the catastrophe of Chinese dumping sites of Yao Lu to be shown as images of bucolic appearance. We bit the fruit of our pride and today paradise is a shy promise. We need to build works, with concrete actions to transform the announced catastrophe in a redemptive epiphany. The landscape is, with its potential for imagination and denunciation, the much needed tool.

Alejandro Malo (Mexico, 1972). Lives and works in Mexico and is the director of ZoneZero. Since 1993, he has taken part in various cultural projects and worked as an information technology consultant. He has collaborated in print and electronic publications, and given workshops and conferences on literature, creative writing, storytelling and technology. In 2009, Malo joined the team of the Fundación Pedro Meyer, where he directs the Archives and Technology departments.

Alejandro Malo (Mexico, 1972). Lives and works in Mexico and is the director of ZoneZero. Since 1993, he has taken part in various cultural projects and worked as an information technology consultant. He has collaborated in print and electronic publications, and given workshops and conferences on literature, creative writing, storytelling and technology. In 2009, Malo joined the team of the Fundación Pedro Meyer, where he directs the Archives and Technology departments.

Cloud Phenomena of Maloja. Film by Arnold Fanck, 1924

Landscape, long before being image, was literature and longing. Since ancient times, almost every civilization led an educated class that longed to return to the simple life of the countryside, back to nature with its deeper order and less troubled appearance. In the West, despite its widespread tradition against the city life and akin to recover the rural simplicity, it is only during the Renaissance that the joy of those running away from the maddening crowds turns into the full enjoyment of nature, first in poetry and only afterwards as a growing presence in paintings. In the East, at least since China’s Tang Dynasty, a fertile dialogue is established around the landscape between poetry and painting, and the genre develops very soon and evolves in multiple aspects.

Centuries later, while other visual media were confronted by the emergence of photography to take in and emphasize the subjectivity of their gaze over this topic, photographic landscapes devote their attention to exoticism or the magnificence of natural views and offered a deceptive closeness to a naturalist interpretation. The romantic vision of nature took root strongly across images ranging from the Bisson brothers to Ansel Adams. In them, beauty was something external to be captured in each shot, a reserve where solitude was a regained innocence and open spaces offered an inexhaustible source of peacefulness for the contemplative eye under the changing light’s mantle.

Gradually, as these perspectives became advertising and marketing leitmotifs, this genre had to be reinvented and new possibilities sought elsewhere. Already in 1975, with the exhibition New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-Altered Landscape, it became clear that human intervention was inseparable from our new perception of landscape. The aseptic style of the authors gathered in this exhibition, considered almost forensic and where the emotional charge seemed absent, caused the sensation of being somehow close to a crime scene’s lingering memories, but devoid of its dramatic charge. During the following years, some authors, with a similar methodology but against this trend, looked after landscapes as representation of their own temperament, metaphor of an inner life that finds in the environment an affinity and a strong individual expressive capacity. Finally, photography assumed the same subjectivity of other means. As an example, Hiroshi Sugimoto wrote about his Seascapes: "Every time I view the sea, I feel a calming sense of security, as if visiting my ancestral home". In that phrase, anyone can guess a sort of poetic inclination and a strong artistic weight that facilitates dialogue with paintings, as was done in 2012 by exposing this series with Mark Rothko’s work.

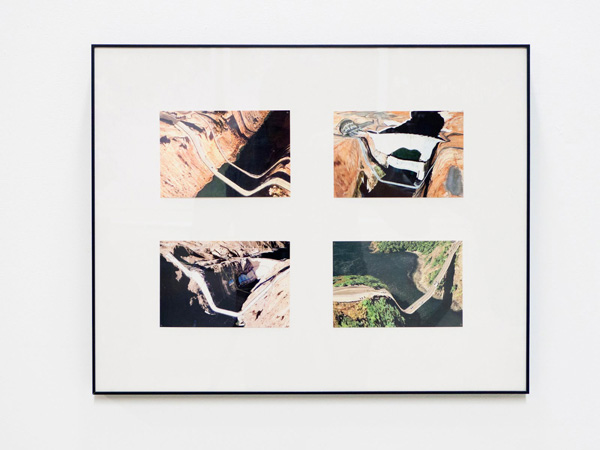

However, Eden’s innocence became impossible in a world where human presence outreach tainted glaciers and forests with the same nonchalance. In the second half of the twentieth century, the landscape was transformed from man facing nature, to be a metaphor for our own humanity and, at the same time, scene of our fears, hopes and tragedies. We read as landscape every place where a scenario simulates an open space, no matter whether an emotional or conceptual projection of ourselves, but also we read it under the titanic action of mining, between the megalopolis’ streets or against the inventiveness of major transformation projects. Hybridization of genres has allowed the unreal calm of sensationalist scenes as in Fernando Brito’s pictures and the catastrophe of Chinese dumping sites of Yao Lu to be shown as images of bucolic appearance. We bit the fruit of our pride and today paradise is a shy promise. We need to build works, with concrete actions to transform the announced catastrophe in a redemptive epiphany. The landscape is, with its potential for imagination and denunciation, the much needed tool.

Alejandro Malo (Mexico, 1972). Lives and works in Mexico and is the director of ZoneZero. Since 1993, he has taken part in various cultural projects and worked as an information technology consultant. He has collaborated in print and electronic publications, and given workshops and conferences on literature, creative writing, storytelling and technology. In 2009, Malo joined the team of the Fundación Pedro Meyer, where he directs the Archives and Technology departments.

Alejandro Malo (Mexico, 1972). Lives and works in Mexico and is the director of ZoneZero. Since 1993, he has taken part in various cultural projects and worked as an information technology consultant. He has collaborated in print and electronic publications, and given workshops and conferences on literature, creative writing, storytelling and technology. In 2009, Malo joined the team of the Fundación Pedro Meyer, where he directs the Archives and Technology departments.Annemarie Bas

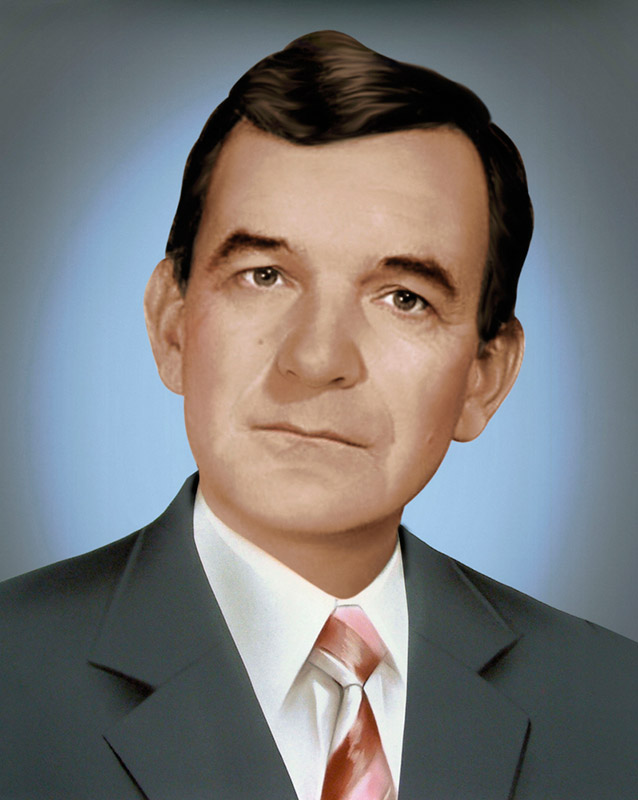

Zbigniew Libera (Pabianice, 1959) is a Polish artist who is not afraid of pushing boundaries, by creating provocative work that challenges the canonical narratives of our contemporary culture. He is known internationally for his work LEGO (1996), a limited edition of three LEGO sets of a concentration camp, that provoked a media controversy at the Venice Biennale of 1997. The curator of the Polish pavilion, Jan Stanisław Wojciechowski, refused to present it, saying the work treated one of the darkest moments in European civilization in a too frivolous manner.1

LEGO. Zbigniew Libera, 1996.

LEGO. Zbigniew Libera, 1996.

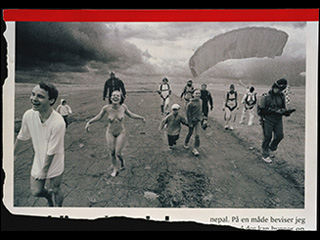

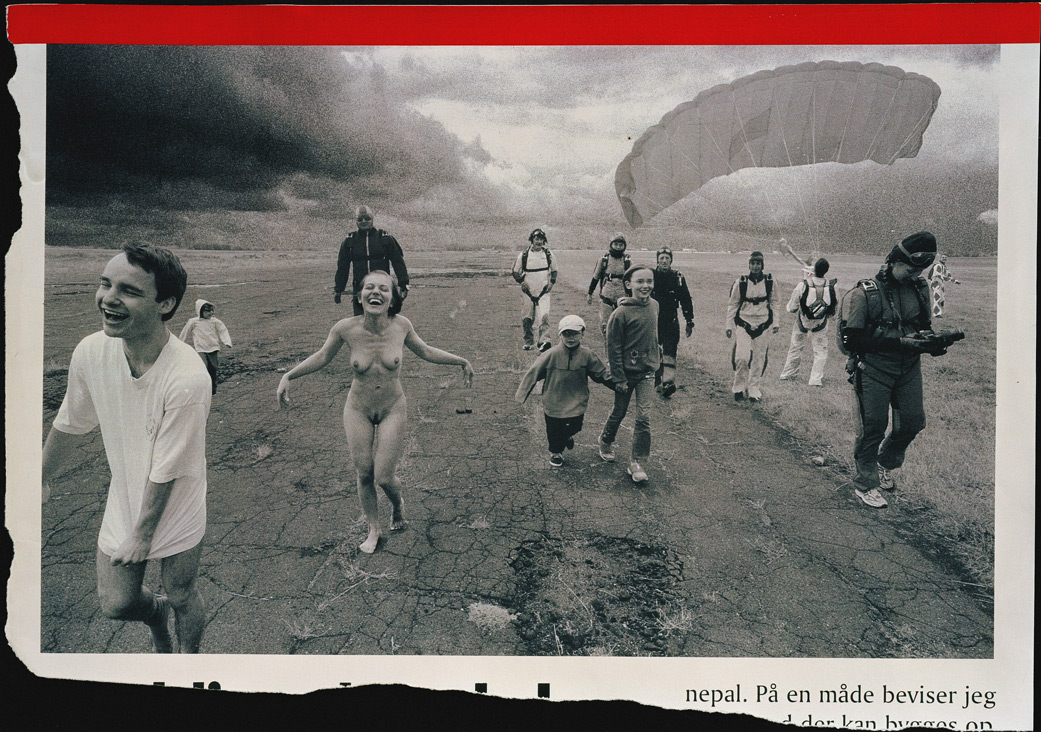

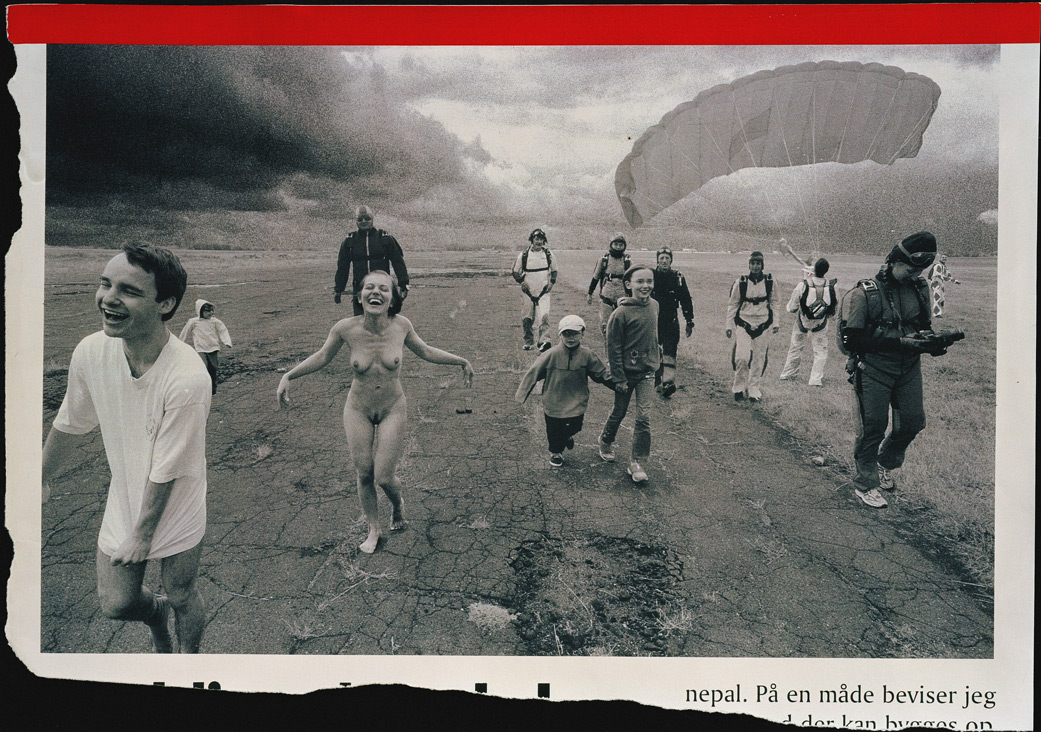

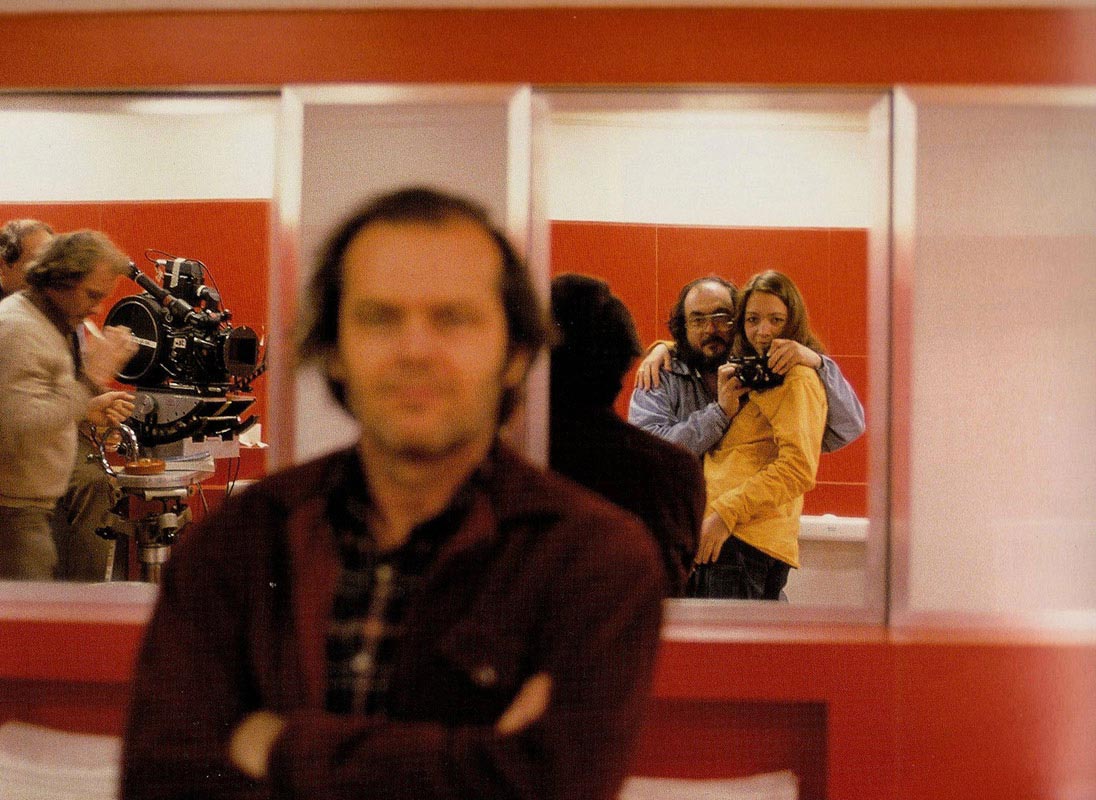

In 2002-2003 Libera made the series Positives, which he described as "another attempt at playing with trauma".2 For this series, he selected traumatic iconic photographs from recent history and made a positive version of them. The photo of a naked Vietnamese girl, running away from the village of Trang Bang after the napalm bombing in 1972, has been changed into a positive image of a nude and smiling woman; a group of concentration camp prisoners have been replaced by smiling figures in striped costumes.3

Positives. Zbigniew Libera, 2002-2003.

Positives. Zbigniew Libera, 2002-2003.

At first sight, we could state that this series is, like LEGO, a too frivolous approach of some of the traumatic episodes of our recent history. Some of the people who went through these horrors are still alive. Is it not disrespectful to confront them with a positive reinterpretation of their suffering? And to what end? What is Libera trying to say with this work? Is he just trying to be controversial or is there a more profound reasoning behind it?

In an interview with Katarzyna Bielas and Dorota Jarecka, from the Polish newspaper Gazeta Wyborcza, Libera said:

It seems to me that nowadays we don’t want to know what reality is like, we want to experience it positively. That’s why the prisoners became inhabitants, those were sad, these are glad. On the other hand it can be the mechanism of Nazi or Soviet propaganda, which changed reality into the set of optimistic slogans.4

On the one hand, it’s true that the market is providing us with a flood of glamorous and positive images. While there are plenty of serious issues asking for our attention —like climate change, armed conflicts, inequality— it is easy to get lost in the latest news about celebrities and fashion trends.5 On the other hand, the opposite is certainly as true, if not more so. Everyday we are flooded by shocking, sad, and negative images of people being decapitated by terrorists and refugees fleeing conflicted areas. Just think of the image of Aylan, the little Syrian boy who drowned in an attempt to reach the shores of Europe. This image was in the news for days and was widely disseminated by the social media. In this case, the so-called harsh reality was not ignored or concealed by optimistic slogans, but rather magnified and used as a moral appeal and tool for political action.

Kid Aylan Kurdi. 2015.

In an interview with Hedvig Turai from Art Margins, Libera gave another, more interesting explanation for Positives:

You have all those traumatic pictures that I am sure no one is able to consume and digest. You cannot live with them (…). I think that people instinctively do not want to look at these pictures, like that of the Vietnamese girl injured by napalm. We have various blocks. And the photo is blocked.6

By confronting us with a positive version of the traumatic photos, Libera hopes to unblock the original negative, so we can feel their impact again.7

One can wonder if everybody is experiencing this psychological block, but if we reflect a little bit more on the idea of iconic photographs being blocked, we could say that there’s also another kind of block which arises over the years, when a photo is used over and over again as an educational and political tool, and has become part of a fixed narrative. We have learned to look and interpret our past through these iconic photographs and it has become difficult to just see them by themselves without thinking of the narratives we’ve constructed around them. In the interview mentioned above, Libera says:

We never see anything for the first time, we always look at an object and we come back to the picture we saw of this object the previous time. We always make one step back into memory, back to the previous picture. We always view our own memories of things, and not the things themselves. It is like one very long permanent journey into our memory. I tried to nail down this process of seeing and remembering.8

What Libera says here about always viewing our memories of things and not the things themselves is certainly true. Personally, when I see the photos on which the positive Residents is based, I immediately recall the education I’ve had about the Holocaust, all the films and books I’ve seen and read about this theme, and the yearly commemorations of the horrors of World War II; and I cannot see these images without thinking about the lesson I was taught: "We cannot let this happen ever again". Although there is nothing wrong with that lesson, it makes you think of the power iconic images have; some more reflection on that wouldn’t be bad.

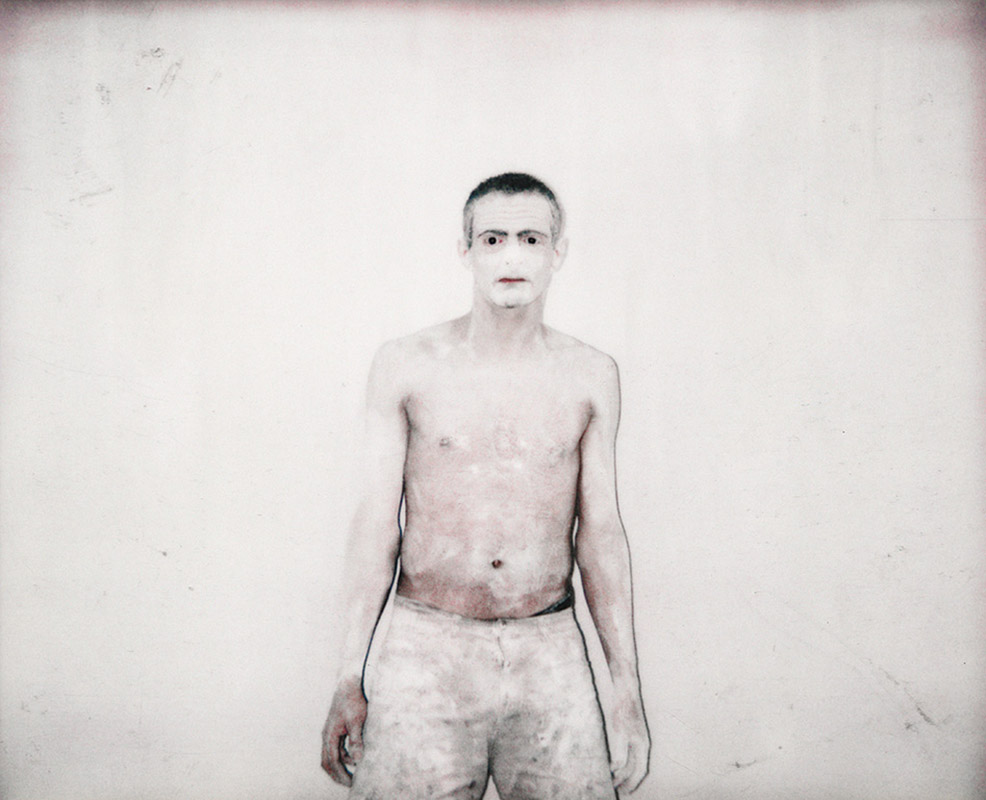

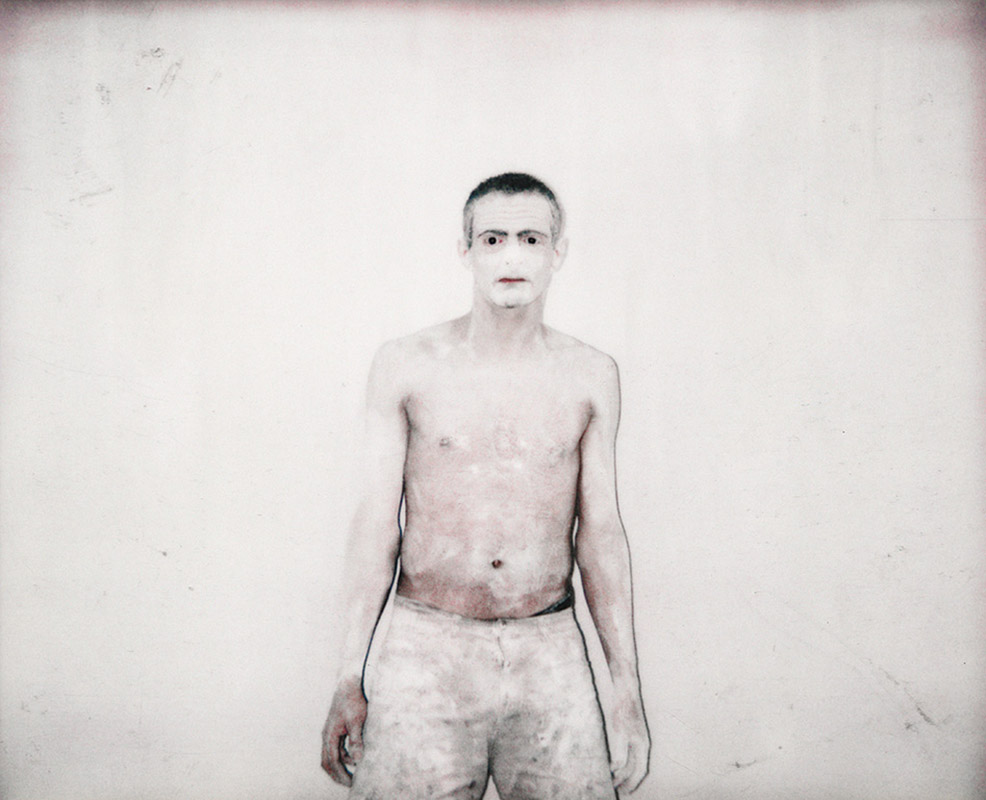

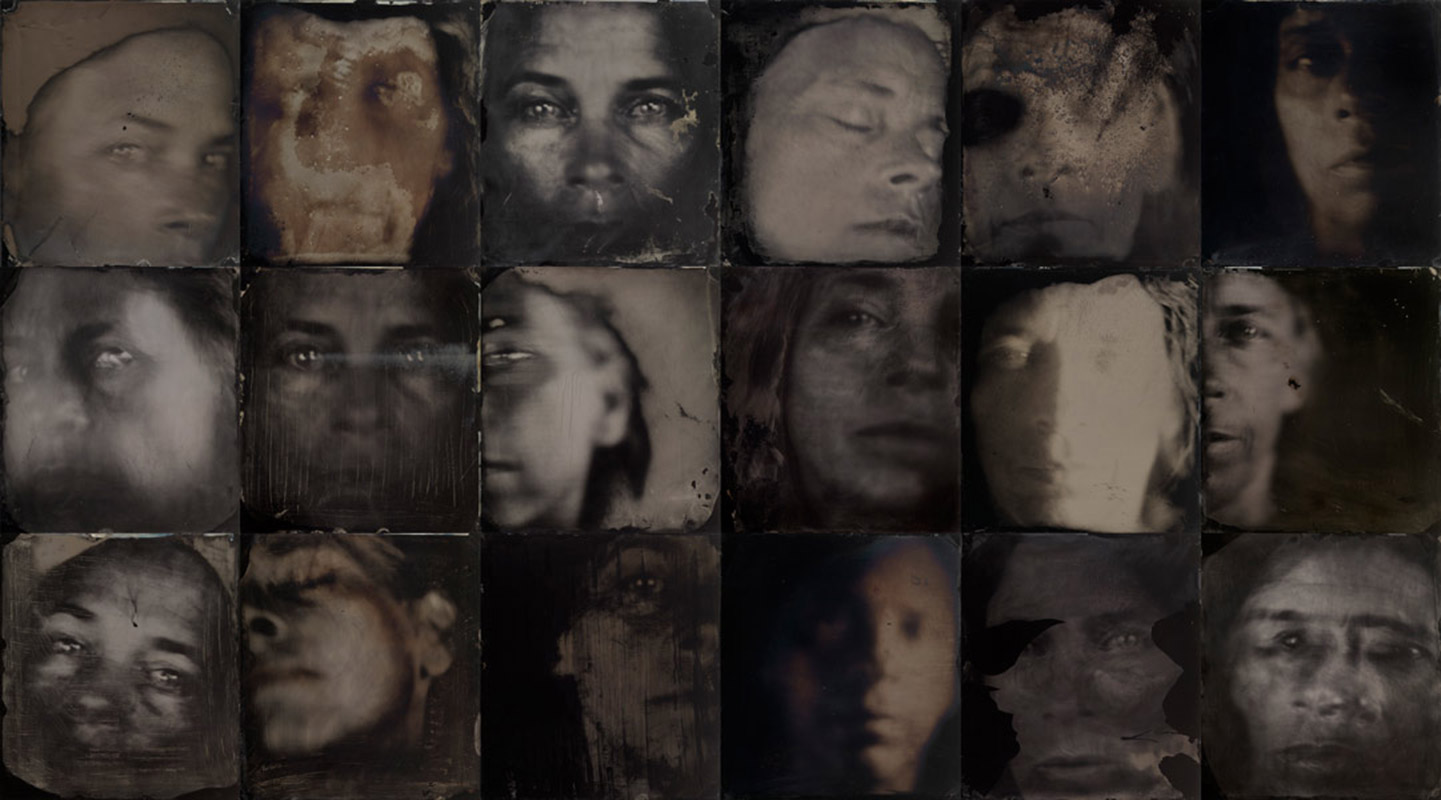

Residents. Zbigniew Libera.

Coming back to the question if there is more to the work Positives than just controversy, I think we can reasonably answer that in the affirmative, although his method might not be the most sensitive one. The Czech photographer Pavel Maria Smejlik, who is playing a similar game of seeing and remembering with his series Fatescapes (2009-2010), has a more subtle approach: he also selected iconic (war) images but instead of making their positive counterpart, he took out the central motifs and people.9 If we assume that this kind of traumatic images are blocked, this would be another way of unblocking them but then without the initial shock of seeing their positive reinterpretation.

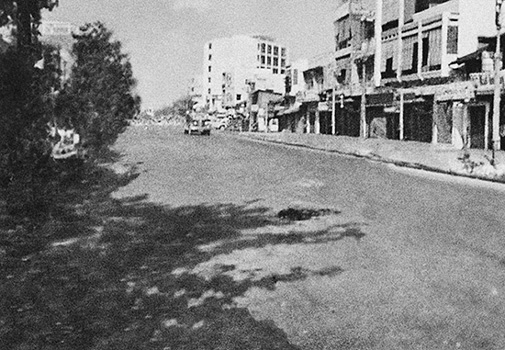

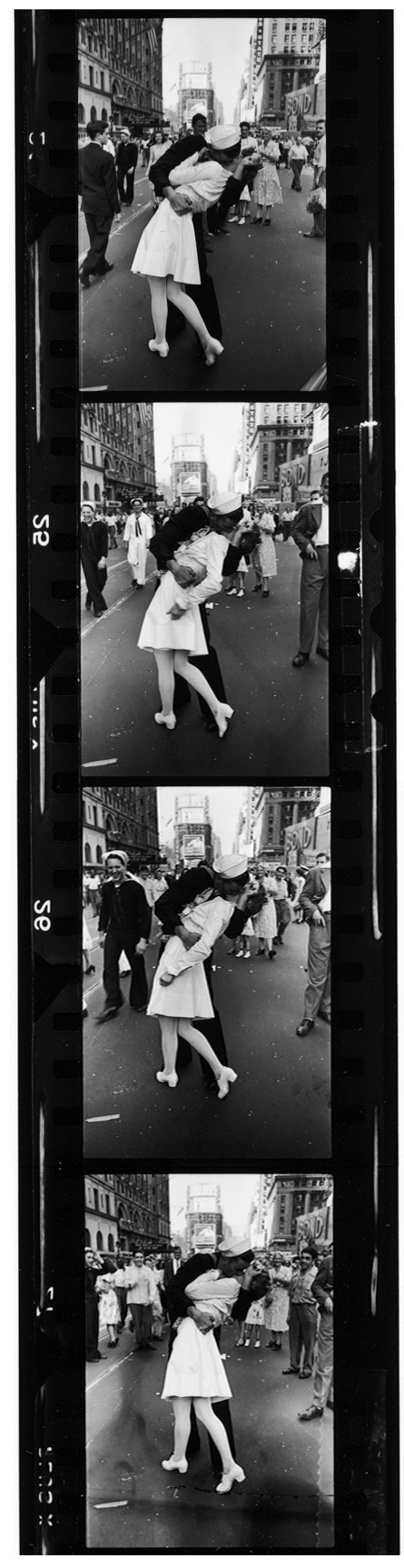

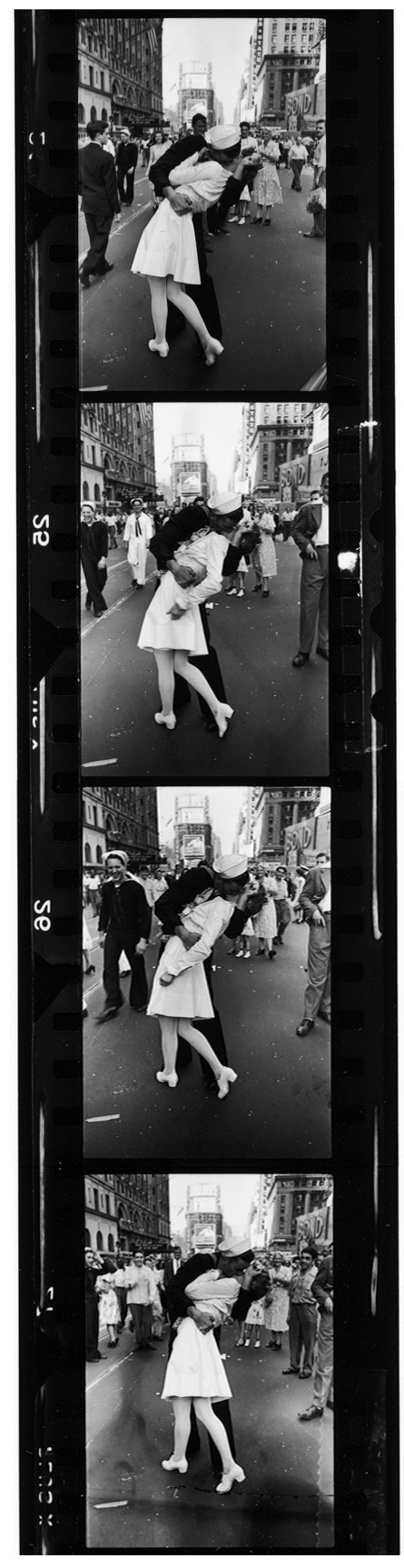

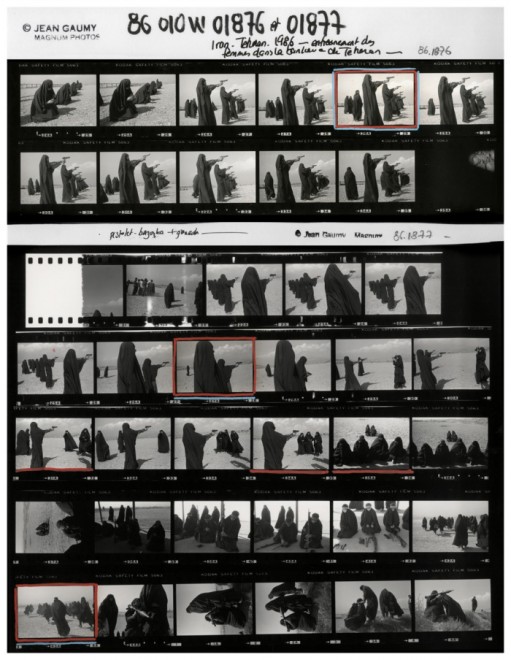

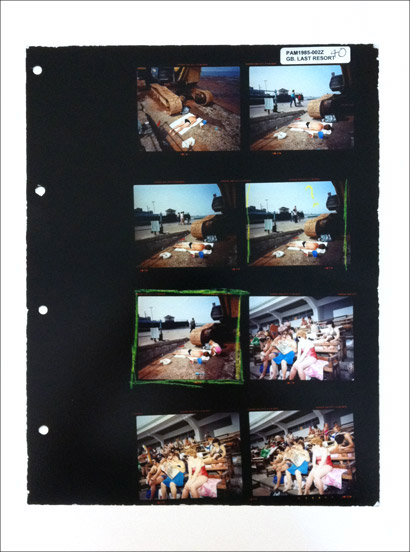

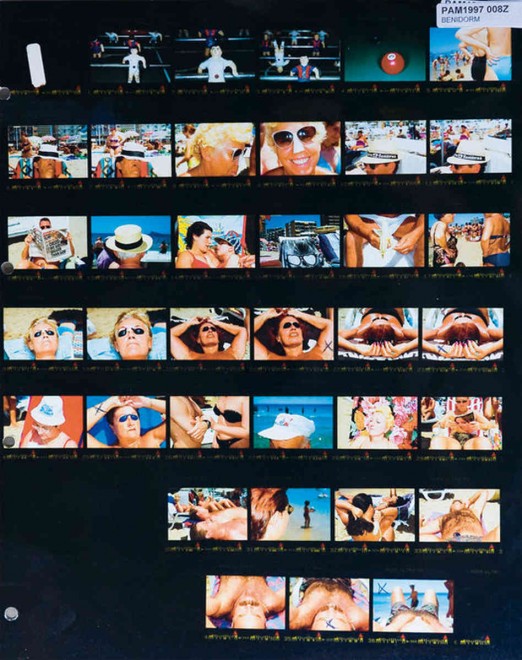

Fatescapes. Pavel Maria Smejkal, 2009-2010.

Whatever one’s personal preference, Libera’s work doesn’t leave one indifferent. Positives challenges us to ask ourselves if we really have observed the iconic photos that surround us and if we’ve reflected upon the narratives connected to them. The dialogue that this series might inspire about the fixed narratives related to these iconic images, is a valuable one that we should have more often.

1. http://articles.latimes.com/1997-05-19/news/mn-60350_1_lego-toys

2. http://raster.art.pl/gallery/artists/libera/prace.htm

3. http://www.artmargins.com/index.php/archive/166-the-artist-does-not-own-his-interpretations-hedvig-turai-in-conversation-with-zbigniew-libera

4. http://maurycy.atlas.com.pl/ang.nsf/0/46CD099B0570C5CBC1256E37004D54D4?OpenDocument

5. Un comentario interesante sobre este fenómeno es “Simple Living “ de Nadia Plesner: http://www.nadiaplesner.com/simple-living--darfurnica1

6. http://www.artmargins.com/index.php/archive/166-the-artist-does-not-own-his-interpretations-hedvig-turai-in-conversation-with-zbigniew-libera

7. http://deruimtemaker.nl/2013/02/27/spelen-met-iconen-uit-de-fotografie/

8. http://www.artmargins.com/index.php/archive/166-the-artist-does-not-own-his-interpretations-hedvig-turai-in-conversation-with-zbigniew-libera

9. http://www.pavelmaria.com/fatescapestext2.html

Annemarie Bas (The Netherlands, 1986), has a Bachelor’s degree in History at the University of Utrecht and a Master’s degree in Cultural History at the same institution. As a historian, she worked as a junior researcher at the Museum of Psychiatry "Het Dolhuys" in Haarlem, The Netherlands. Since 2013, she lives and works in Mexico City. At the moment, she is international liaison at ZoneZero and works as an independent translator.

Annemarie Bas (The Netherlands, 1986), has a Bachelor’s degree in History at the University of Utrecht and a Master’s degree in Cultural History at the same institution. As a historian, she worked as a junior researcher at the Museum of Psychiatry "Het Dolhuys" in Haarlem, The Netherlands. Since 2013, she lives and works in Mexico City. At the moment, she is international liaison at ZoneZero and works as an independent translator.Zbigniew Libera (Pabianice, 1959) is a Polish artist who is not afraid of pushing boundaries, by creating provocative work that challenges the canonical narratives of our contemporary culture. He is known internationally for his work LEGO (1996), a limited edition of three LEGO sets of a concentration camp, that provoked a media controversy at the Venice Biennale of 1997. The curator of the Polish pavilion, Jan Stanisław Wojciechowski, refused to present it, saying the work treated one of the darkest moments in European civilization in a too frivolous manner.1

LEGO. Zbigniew Libera, 1996.

LEGO. Zbigniew Libera, 1996.

In 2002-2003 Libera made the series Positives, which he described as "another attempt at playing with trauma".2 For this series, he selected traumatic iconic photographs from recent history and made a positive version of them. The photo of a naked Vietnamese girl, running away from the village of Trang Bang after the napalm bombing in 1972, has been changed into a positive image of a nude and smiling woman; a group of concentration camp prisoners have been replaced by smiling figures in striped costumes.3

Positives. Zbigniew Libera, 2002-2003.

Positives. Zbigniew Libera, 2002-2003.

At first sight, we could state that this series is, like LEGO, a too frivolous approach of some of the traumatic episodes of our recent history. Some of the people who went through these horrors are still alive. Is it not disrespectful to confront them with a positive reinterpretation of their suffering? And to what end? What is Libera trying to say with this work? Is he just trying to be controversial or is there a more profound reasoning behind it?

In an interview with Katarzyna Bielas and Dorota Jarecka, from the Polish newspaper Gazeta Wyborcza, Libera said:

It seems to me that nowadays we don’t want to know what reality is like, we want to experience it positively. That’s why the prisoners became inhabitants, those were sad, these are glad. On the other hand it can be the mechanism of Nazi or Soviet propaganda, which changed reality into the set of optimistic slogans.4

On the one hand, it’s true that the market is providing us with a flood of glamorous and positive images. While there are plenty of serious issues asking for our attention —like climate change, armed conflicts, inequality— it is easy to get lost in the latest news about celebrities and fashion trends.5 On the other hand, the opposite is certainly as true, if not more so. Everyday we are flooded by shocking, sad, and negative images of people being decapitated by terrorists and refugees fleeing conflicted areas. Just think of the image of Aylan, the little Syrian boy who drowned in an attempt to reach the shores of Europe. This image was in the news for days and was widely disseminated by the social media. In this case, the so-called harsh reality was not ignored or concealed by optimistic slogans, but rather magnified and used as a moral appeal and tool for political action.

Kid Aylan Kurdi. 2015.

In an interview with Hedvig Turai from Art Margins, Libera gave another, more interesting explanation for Positives:

You have all those traumatic pictures that I am sure no one is able to consume and digest. You cannot live with them (…). I think that people instinctively do not want to look at these pictures, like that of the Vietnamese girl injured by napalm. We have various blocks. And the photo is blocked.6

By confronting us with a positive version of the traumatic photos, Libera hopes to unblock the original negative, so we can feel their impact again.7

One can wonder if everybody is experiencing this psychological block, but if we reflect a little bit more on the idea of iconic photographs being blocked, we could say that there’s also another kind of block which arises over the years, when a photo is used over and over again as an educational and political tool, and has become part of a fixed narrative. We have learned to look and interpret our past through these iconic photographs and it has become difficult to just see them by themselves without thinking of the narratives we’ve constructed around them. In the interview mentioned above, Libera says:

We never see anything for the first time, we always look at an object and we come back to the picture we saw of this object the previous time. We always make one step back into memory, back to the previous picture. We always view our own memories of things, and not the things themselves. It is like one very long permanent journey into our memory. I tried to nail down this process of seeing and remembering.8

What Libera says here about always viewing our memories of things and not the things themselves is certainly true. Personally, when I see the photos on which the positive Residents is based, I immediately recall the education I’ve had about the Holocaust, all the films and books I’ve seen and read about this theme, and the yearly commemorations of the horrors of World War II; and I cannot see these images without thinking about the lesson I was taught: "We cannot let this happen ever again". Although there is nothing wrong with that lesson, it makes you think of the power iconic images have; some more reflection on that wouldn’t be bad.

Residents. Zbigniew Libera.

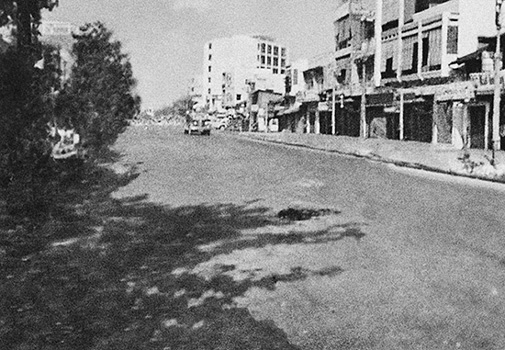

Coming back to the question if there is more to the work Positives than just controversy, I think we can reasonably answer that in the affirmative, although his method might not be the most sensitive one. The Czech photographer Pavel Maria Smejlik, who is playing a similar game of seeing and remembering with his series Fatescapes (2009-2010), has a more subtle approach: he also selected iconic (war) images but instead of making their positive counterpart, he took out the central motifs and people.9 If we assume that this kind of traumatic images are blocked, this would be another way of unblocking them but then without the initial shock of seeing their positive reinterpretation.

Fatescapes. Pavel Maria Smejkal, 2009-2010.

Whatever one’s personal preference, Libera’s work doesn’t leave one indifferent. Positives challenges us to ask ourselves if we really have observed the iconic photos that surround us and if we’ve reflected upon the narratives connected to them. The dialogue that this series might inspire about the fixed narratives related to these iconic images, is a valuable one that we should have more often.

1. http://articles.latimes.com/1997-05-19/news/mn-60350_1_lego-toys

2. http://raster.art.pl/gallery/artists/libera/prace.htm

3. http://www.artmargins.com/index.php/archive/166-the-artist-does-not-own-his-interpretations-hedvig-turai-in-conversation-with-zbigniew-libera

4. http://maurycy.atlas.com.pl/ang.nsf/0/46CD099B0570C5CBC1256E37004D54D4?OpenDocument

5. Un comentario interesante sobre este fenómeno es “Simple Living “ de Nadia Plesner: http://www.nadiaplesner.com/simple-living--darfurnica1

6. http://www.artmargins.com/index.php/archive/166-the-artist-does-not-own-his-interpretations-hedvig-turai-in-conversation-with-zbigniew-libera

7. http://deruimtemaker.nl/2013/02/27/spelen-met-iconen-uit-de-fotografie/

8. http://www.artmargins.com/index.php/archive/166-the-artist-does-not-own-his-interpretations-hedvig-turai-in-conversation-with-zbigniew-libera

9. http://www.pavelmaria.com/fatescapestext2.html

Annemarie Bas (The Netherlands, 1986), has a Bachelor’s degree in History at the University of Utrecht and a Master’s degree in Cultural History at the same institution. As a historian, she worked as a junior researcher at the Museum of Psychiatry "Het Dolhuys" in Haarlem, The Netherlands. Since 2013, she lives and works in Mexico City. At the moment, she is international liaison at ZoneZero and works as an independent translator.

Annemarie Bas (The Netherlands, 1986), has a Bachelor’s degree in History at the University of Utrecht and a Master’s degree in Cultural History at the same institution. As a historian, she worked as a junior researcher at the Museum of Psychiatry "Het Dolhuys" in Haarlem, The Netherlands. Since 2013, she lives and works in Mexico City. At the moment, she is international liaison at ZoneZero and works as an independent translator.Alejandro Malo

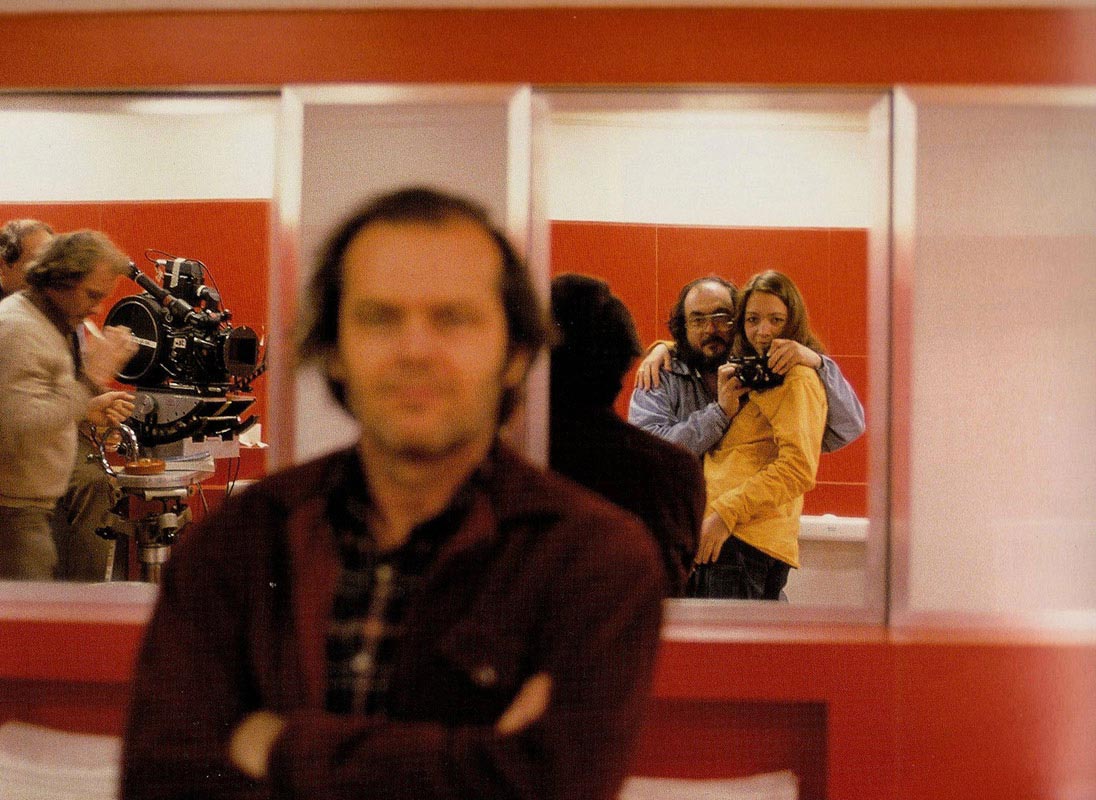

In Postproduction, I try to show that artists' intuitive relationship with art history is now going beyond what we call "the art of appropriation," which naturally infers an ideology of ownership, and moving toward a culture of the use of forms, a culture of constant activity of signs based on a collective ideal: sharing. —Nicolas Bourriaud.

Scene of the film Metropolis by Fritz Lang, 1927.

For some time now, the resource of appropriation in photography has gone from being a subversive and provocative act to being, in many cases, the catch phrase which seeks to associate the prestige of previous artworks and contexts with fresh projects. The very concept of appropriation assumes the possibility of appropriating a material aspect of an image which is becoming more and more intangible. Due to the increasing production, consumption and transformation of images in a digital format, there is now an infinite number of possible reincarnations of not only every photograph, but also of its copies and variants, and of other photographs which it references, parodies or recreates. This never-ending cascade of repetitions and similarities has rendered unnecessary any fight against the concepts of originality and authorship, which only a few decades ago, it seemed essential to question. Originality, at risk of showing itself up with touching naivety, has not evolved from being a different arrangement of very well-known elements. Similarly, authorship hardly ends up as the top hat from which, like a rabbit, a well-edited design made up of materials uploaded from almost indistinguishable references will appear. In such a scenario, what does artwork openly based on somebody else’s material suggest? What question does it raise and what answer does it provide? Or, ideally, what question would it raise and what answer would it give so as not to remain merely a superficial resource?

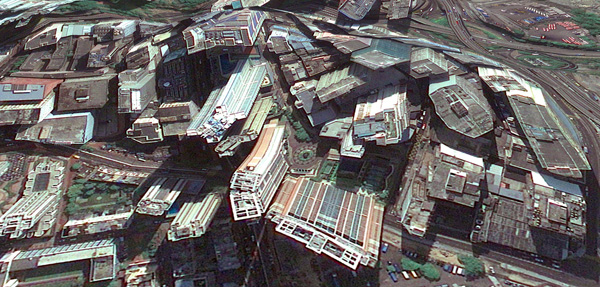

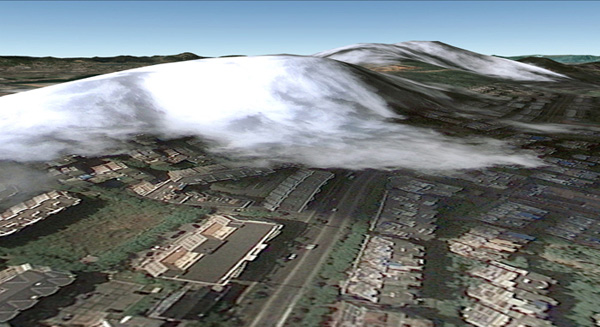

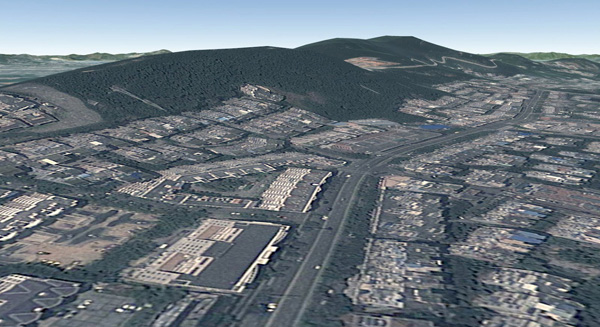

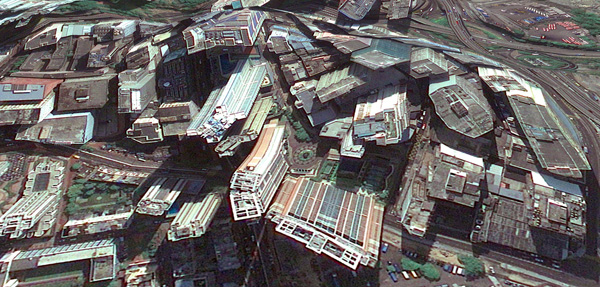

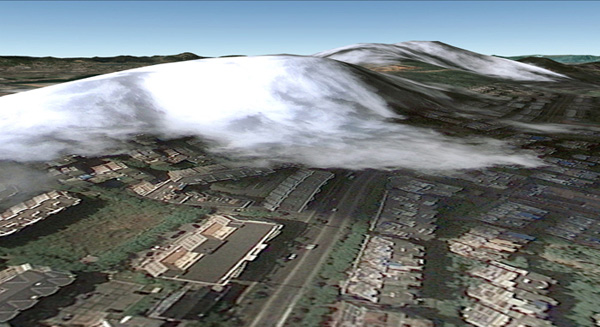

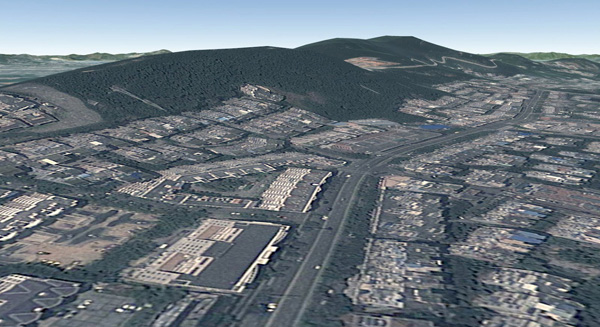

The first step in formulating a response is to recognize that the boundaries of this practice are imprecise. It is impossible to define the point at which the reinterpretation of archived material or their intervention turns into a practice of visual recycling and rewriting of its meaning. If we add to this catalogue of practices, collages and photo montages, as well as the found footage and the capture of three- dimensional representations (for example, Street View or Apple Maps), then the territory becomes immeasurable. However, perhaps it is this complexity itself that is the first supporting point: a project that is constructed from a remix does not conceal its debt to other sources, and instead demonstrates its aim of proposing a new interpretation of them, albeit in a modest way. This in itself highlights an ethical concern with respect to the rule of images. Here lies a commitment to not only inviting a reflective way of looking at a universe that already exists but also a desire to add meaning to this universe. This leads us to the following conclusion: a project of this kind calls for contextual boundaries to be fixed. In order to create a new meaning it is fundamental to acknowledge previous meanings and references. Whether this is achieved by means of footnotes, marginal notes or definition by the micro universe itself regarding the selection and shots it comprises, or even the sum of a variety of these resources, the result is always one step further away from the original sources.

Finally, making the effort to acknowledge the fact that an image derives from previous artwork and that it aspires to become part of a context allows us to deduce a final characteristic of these designs, a characteristic that we can call the ecology of photographic recycling. In a world in which images are created at an extraordinary pace and in which every image can be disposable, appropriation acknowledges that images can take on new meanings and be enriched by broader meanings. The unstoppable avalanche of production comes face to face with the reasoned observation of reproduction and the modest judgment of post-production. The decreasing value of originality counters analysis, and the curator’s panoramic vision opposes the author’s perspective.

If we admit that in between the practices of appropriation and remix lies a need for ethics and ecology, which themselves require individual assessment and research, perhaps we can better measure the current relevance of the latest designs and recognize the scope of each one. If we accept that this new economy of shared property adds as much economic value as it does symbolic value, perhaps we will then have more factors related to our notions about intellectual property to adjust to a more progressive framework. The questions from the photographic world - in which there is so much to see and so much to understand - are timely and certainly worth acknowledging. Are we capable of doing so?

Alejandro Malo (Mexico, 1972). Lives and works in Mexico and is the director of ZoneZero. Since 1993, he has taken part in various cultural projects and worked as an information technology consultant. He has collaborated in print and electronic publications, and given workshops and conferences on literature, creative writing, storytelling and technology. In 2009, Malo joined the team of the Fundación Pedro Meyer, where he directs the Archives and Technology departments.

Alejandro Malo (Mexico, 1972). Lives and works in Mexico and is the director of ZoneZero. Since 1993, he has taken part in various cultural projects and worked as an information technology consultant. He has collaborated in print and electronic publications, and given workshops and conferences on literature, creative writing, storytelling and technology. In 2009, Malo joined the team of the Fundación Pedro Meyer, where he directs the Archives and Technology departments.[core_state] => 1 [core_access] => 1 [core_metadata] => {"robots":"","author":"Alejandro Malo","rights":"","xreference":""} [core_created_user_id] => 838 [core_created_by_alias] => [core_created_time] => 2015-10-12 06:02:21 [core_images] => {"image_intro":"images\/categories\/apropiacion\/metropolis.gif","float_intro":"","image_intro_alt":"","image_intro_caption":"","image_fulltext":"images\/categories\/apropiacion\/metropolis.gif","float_fulltext":"","image_fulltext_alt":"","image_fulltext_caption":""} [core_modified_time] => 2016-05-19 17:00:34 [core_language] => en-GB [core_catid] => 63 [core_publish_up] => 2015-10-12 06:02:21 [core_publish_down] => 0000-00-00 00:00:00 [content_type_title] => Article [router] => ContentHelperRoute::getArticleRoute [author] => Elisa Rugo [author_email] => elisa@zonezero.com [link] => index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=331:appropriation-and-remix&catid=63&lang=en-GB [displayDate] => 2015-10-12 06:02:21 [event] => stdClass Object ( [afterDisplayTitle] => [beforeDisplayContent] => [afterDisplayContent] => ) [text] =>

In Postproduction, I try to show that artists' intuitive relationship with art history is now going beyond what we call "the art of appropriation," which naturally infers an ideology of ownership, and moving toward a culture of the use of forms, a culture of constant activity of signs based on a collective ideal: sharing. —Nicolas Bourriaud.

Scene of the film Metropolis by Fritz Lang, 1927.

For some time now, the resource of appropriation in photography has gone from being a subversive and provocative act to being, in many cases, the catch phrase which seeks to associate the prestige of previous artworks and contexts with fresh projects. The very concept of appropriation assumes the possibility of appropriating a material aspect of an image which is becoming more and more intangible. Due to the increasing production, consumption and transformation of images in a digital format, there is now an infinite number of possible reincarnations of not only every photograph, but also of its copies and variants, and of other photographs which it references, parodies or recreates. This never-ending cascade of repetitions and similarities has rendered unnecessary any fight against the concepts of originality and authorship, which only a few decades ago, it seemed essential to question. Originality, at risk of showing itself up with touching naivety, has not evolved from being a different arrangement of very well-known elements. Similarly, authorship hardly ends up as the top hat from which, like a rabbit, a well-edited design made up of materials uploaded from almost indistinguishable references will appear. In such a scenario, what does artwork openly based on somebody else’s material suggest? What question does it raise and what answer does it provide? Or, ideally, what question would it raise and what answer would it give so as not to remain merely a superficial resource?

The first step in formulating a response is to recognize that the boundaries of this practice are imprecise. It is impossible to define the point at which the reinterpretation of archived material or their intervention turns into a practice of visual recycling and rewriting of its meaning. If we add to this catalogue of practices, collages and photo montages, as well as the found footage and the capture of three- dimensional representations (for example, Street View or Apple Maps), then the territory becomes immeasurable. However, perhaps it is this complexity itself that is the first supporting point: a project that is constructed from a remix does not conceal its debt to other sources, and instead demonstrates its aim of proposing a new interpretation of them, albeit in a modest way. This in itself highlights an ethical concern with respect to the rule of images. Here lies a commitment to not only inviting a reflective way of looking at a universe that already exists but also a desire to add meaning to this universe. This leads us to the following conclusion: a project of this kind calls for contextual boundaries to be fixed. In order to create a new meaning it is fundamental to acknowledge previous meanings and references. Whether this is achieved by means of footnotes, marginal notes or definition by the micro universe itself regarding the selection and shots it comprises, or even the sum of a variety of these resources, the result is always one step further away from the original sources.

Finally, making the effort to acknowledge the fact that an image derives from previous artwork and that it aspires to become part of a context allows us to deduce a final characteristic of these designs, a characteristic that we can call the ecology of photographic recycling. In a world in which images are created at an extraordinary pace and in which every image can be disposable, appropriation acknowledges that images can take on new meanings and be enriched by broader meanings. The unstoppable avalanche of production comes face to face with the reasoned observation of reproduction and the modest judgment of post-production. The decreasing value of originality counters analysis, and the curator’s panoramic vision opposes the author’s perspective.

If we admit that in between the practices of appropriation and remix lies a need for ethics and ecology, which themselves require individual assessment and research, perhaps we can better measure the current relevance of the latest designs and recognize the scope of each one. If we accept that this new economy of shared property adds as much economic value as it does symbolic value, perhaps we will then have more factors related to our notions about intellectual property to adjust to a more progressive framework. The questions from the photographic world - in which there is so much to see and so much to understand - are timely and certainly worth acknowledging. Are we capable of doing so?

Alejandro Malo (Mexico, 1972). Lives and works in Mexico and is the director of ZoneZero. Since 1993, he has taken part in various cultural projects and worked as an information technology consultant. He has collaborated in print and electronic publications, and given workshops and conferences on literature, creative writing, storytelling and technology. In 2009, Malo joined the team of the Fundación Pedro Meyer, where he directs the Archives and Technology departments.

Alejandro Malo (Mexico, 1972). Lives and works in Mexico and is the director of ZoneZero. Since 1993, he has taken part in various cultural projects and worked as an information technology consultant. He has collaborated in print and electronic publications, and given workshops and conferences on literature, creative writing, storytelling and technology. In 2009, Malo joined the team of the Fundación Pedro Meyer, where he directs the Archives and Technology departments.[id] => 331 [language] => en-GB [catid] => 63 [jcfields] => Array ( ) ) 1

Alejandro Malo

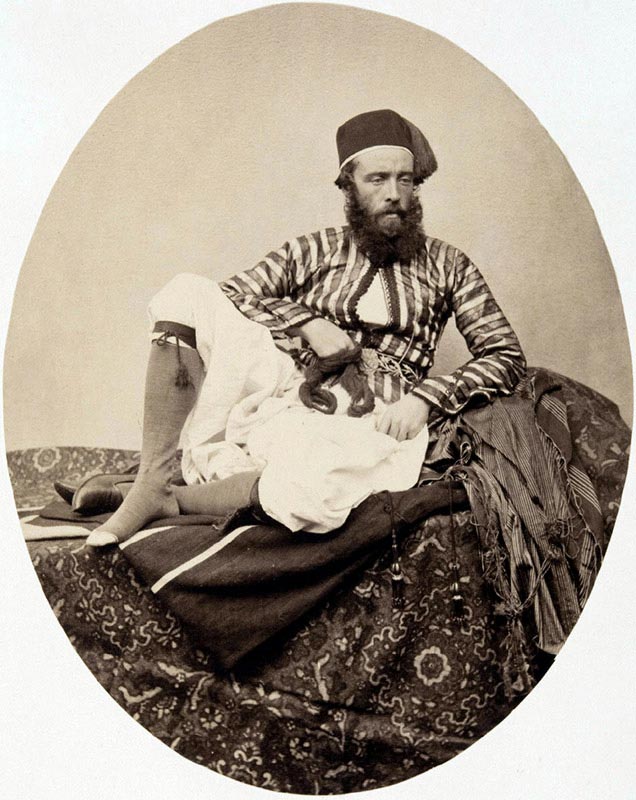

Mexican Family, unknown author, daguerrotype, ca. 1847

Seeing presupposes distance, decisiveness which separates, the power to stay out of contact and in contact avoid confusion.

Seeing means that this separation has nevertheless become an encounter. —Maurice Blanchot.

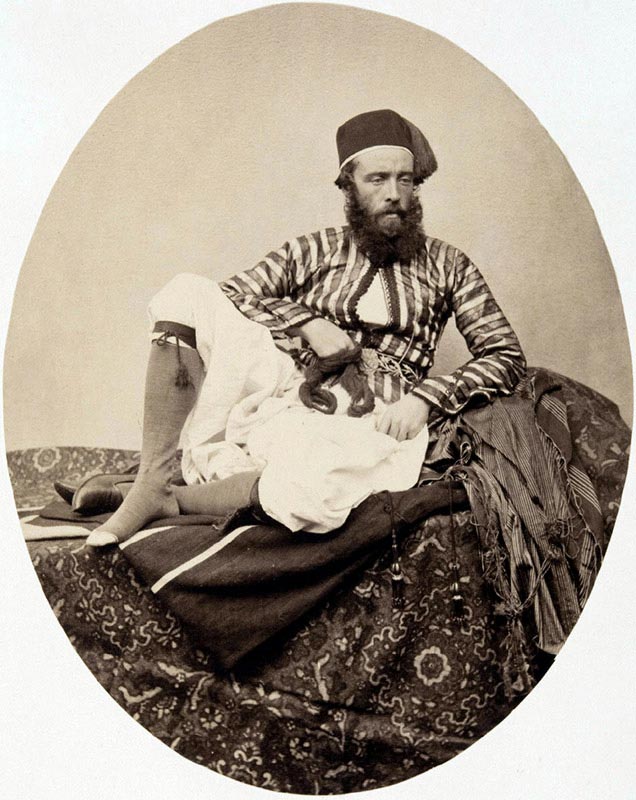

Any representation of a community implies a perspective. Each time we observe a group we become interpreters and with each observation we make, we reveal to which communities we belong. Photography, with its ability to record, was soon considered to be a suitable tool to crystallize these observations and encourage the study of ethnicity and customs. However, being at least as susceptible to ideological bias as any other medium, it immediately revealed its colonialist burden and it is no coincidence that some of the first photographs that try to document a community were taken in company of an army or along trade routes. Images of the Mexico-American War (1846-1848) and the rebellion in India (1857), for example, show the confusion of these early records in the eyes of those portrayed and often leave us with the feeling that those photos were another kind of victory.

In the last decade of the nineteenth century, Ryuzo Torii and Edward S. Curtis introduce a way of using photography on behalf of ethnology, and Jacob Riis published How the Other Half Lives (1890). In those early photo essays on specific communities, there's a clear awareness of the otherness and a sympathetic point of view, but the perspective of the victors or the moral superiority of the observer is also legitimated. That partly naive, partly pretentious attitude of someone assuming to discover or save the others, has permeated much of photojournalism and documentary work since. Arguing a never achieved objectivity, they perpetuated asymmetrical readings and promoted a colonialism that replaced war's firepower with economy and culture. There were reasons for its existence, as an expression of a particular moment in history and a contribution to global integration, but it has been overtaken by a world whose visual center moves across the surface of the globe and where the last word has the duration of a tweet.

Soon documentalists themselves perceived the contradiction and near the beginning of the twentieth century started to explore alternatives to escape this logic: from the numerous attempts to capture the misleading truth in the style of Dziga Vertov's Kino-Pravda, through Cinema Verite, Direct Cinema, Candid Eye in film and their photographic counterparts, all the way to ethnofiction experiments, the long history of participatory documentary or the hopeful outlook of Shahidul Alam's Majority World, which proposes to let those closer to the phenomena and activities hold the camera. All are useful tools to approach the topic, but they don’t offer a final answer.

An image has the chance, as never before, to represent each ethnic, social and tribal group, whether they live in the cities or the most remote regions, and it also has the potential to do so from many different angles. The camera, already present in many devices, is in the hands of almost anyone who wants to register their community. Maybe it’s time to accept once and for all that to represent a community is not to search an objective representation or an intrinsic truth, nor trying to offer a problematic balance. However, in any case we should try to give a fair interpretation and an accurate testimony, where in many cases the sum of multiple perspectives can bring us closer to an elusive reality. This requires more critical reading and analysis from the public, compels the media to hold stronger values than empty veracity and offers the photographer a more honest path to meet the others. This change, like any change, is full of uncertainties, but ends in a space full of opportunities where the image can lead us.

Alejandro Malo (Mexico, 1972). Lives and works in Mexico and is the director of ZoneZero. Since 1993, he has taken part in various cultural projects and worked as an information technology consultant. He has collaborated in print and electronic publications, and given workshops and conferences on literature, creative writing, storytelling and technology. In 2009, Malo joined the team of the Fundación Pedro Meyer, where he directs the Archives and Technology departments.

Alejandro Malo (Mexico, 1972). Lives and works in Mexico and is the director of ZoneZero. Since 1993, he has taken part in various cultural projects and worked as an information technology consultant. He has collaborated in print and electronic publications, and given workshops and conferences on literature, creative writing, storytelling and technology. In 2009, Malo joined the team of the Fundación Pedro Meyer, where he directs the Archives and Technology departments.

Mexican Family, unknown author, daguerrotype, ca. 1847

Seeing presupposes distance, decisiveness which separates, the power to stay out of contact and in contact avoid confusion.

Seeing means that this separation has nevertheless become an encounter. —Maurice Blanchot.

Any representation of a community implies a perspective. Each time we observe a group we become interpreters and with each observation we make, we reveal to which communities we belong. Photography, with its ability to record, was soon considered to be a suitable tool to crystallize these observations and encourage the study of ethnicity and customs. However, being at least as susceptible to ideological bias as any other medium, it immediately revealed its colonialist burden and it is no coincidence that some of the first photographs that try to document a community were taken in company of an army or along trade routes. Images of the Mexico-American War (1846-1848) and the rebellion in India (1857), for example, show the confusion of these early records in the eyes of those portrayed and often leave us with the feeling that those photos were another kind of victory.

In the last decade of the nineteenth century, Ryuzo Torii and Edward S. Curtis introduce a way of using photography on behalf of ethnology, and Jacob Riis published How the Other Half Lives (1890). In those early photo essays on specific communities, there's a clear awareness of the otherness and a sympathetic point of view, but the perspective of the victors or the moral superiority of the observer is also legitimated. That partly naive, partly pretentious attitude of someone assuming to discover or save the others, has permeated much of photojournalism and documentary work since. Arguing a never achieved objectivity, they perpetuated asymmetrical readings and promoted a colonialism that replaced war's firepower with economy and culture. There were reasons for its existence, as an expression of a particular moment in history and a contribution to global integration, but it has been overtaken by a world whose visual center moves across the surface of the globe and where the last word has the duration of a tweet.

Soon documentalists themselves perceived the contradiction and near the beginning of the twentieth century started to explore alternatives to escape this logic: from the numerous attempts to capture the misleading truth in the style of Dziga Vertov's Kino-Pravda, through Cinema Verite, Direct Cinema, Candid Eye in film and their photographic counterparts, all the way to ethnofiction experiments, the long history of participatory documentary or the hopeful outlook of Shahidul Alam's Majority World, which proposes to let those closer to the phenomena and activities hold the camera. All are useful tools to approach the topic, but they don’t offer a final answer.

An image has the chance, as never before, to represent each ethnic, social and tribal group, whether they live in the cities or the most remote regions, and it also has the potential to do so from many different angles. The camera, already present in many devices, is in the hands of almost anyone who wants to register their community. Maybe it’s time to accept once and for all that to represent a community is not to search an objective representation or an intrinsic truth, nor trying to offer a problematic balance. However, in any case we should try to give a fair interpretation and an accurate testimony, where in many cases the sum of multiple perspectives can bring us closer to an elusive reality. This requires more critical reading and analysis from the public, compels the media to hold stronger values than empty veracity and offers the photographer a more honest path to meet the others. This change, like any change, is full of uncertainties, but ends in a space full of opportunities where the image can lead us.

Alejandro Malo (Mexico, 1972). Lives and works in Mexico and is the director of ZoneZero. Since 1993, he has taken part in various cultural projects and worked as an information technology consultant. He has collaborated in print and electronic publications, and given workshops and conferences on literature, creative writing, storytelling and technology. In 2009, Malo joined the team of the Fundación Pedro Meyer, where he directs the Archives and Technology departments.

Alejandro Malo (Mexico, 1972). Lives and works in Mexico and is the director of ZoneZero. Since 1993, he has taken part in various cultural projects and worked as an information technology consultant. He has collaborated in print and electronic publications, and given workshops and conferences on literature, creative writing, storytelling and technology. In 2009, Malo joined the team of the Fundación Pedro Meyer, where he directs the Archives and Technology departments.Felipe Mejías López

Penitents of the brotherhood of Sorrows, posing with the image of the Virgin during the Easter Week in Aspe (Spain).

March 1929. (Photographer unknown. About photograhy Felipe Mejías, March 2015).

Paper memories. Photographs will always be paper memories, despite the fact that the emergence of digital technology in the world of images has changed the way they are stored. In any case, whether they are stuck in an album, crammed into an old biscuit tin, or stored in a virtual folder tucked away in the darkest corner of our computer’s hard drive, the construction of our memories owes a great deal to these images in black and white or faded colors. We can often reconstruct the exact layout of a place we have been, or feel the gaze of a friend or family member we no longer see because we can re-encounter them when we contemplate these square cardboard remnants. Memory cards and smart phones belong to a different visual universe that has no history but is a slave to the future, subject to a dictatorship that imposes the objective of immediacy and the compulsive desire to devour the overwhelming reality that surrounds us as if it might suddenly and permanently disappear from one moment to the next.

Photographs take us back to what we once were, in a constant, palpable, evident graphic salvation that is fed by our gaze like a fossil into which we breathe life simply by contemplating it. Looking at photos makes us grow, whether or not we want to, because we end up recognizing ourselves in them, somehow transformed into strangers we find it increasingly difficult to recognize: yet, there we are, participating like enthusiastic actors or perhaps behind the viewfinder snapping a photo. This tangible, visual certainty, together with the awareness that time has passed because we remember, creates an incredibly strong sensory cement that binds and gives meaning to our life stories.

But if we broaden the focus and think about our innumerable private –and therefore secret– photographs as a whole that have been collected since the beginning of photography, scattered throughout our immediate environment (not only in our family or neighborhood, but also throughout the macro scale of the city or region where we live), then these images evolve from more than a repertoire of personal memories to cultural objects. And as such, because of the historical, anthropological and ethnological information they contain, these photographs become unique, inimitable objects that deserve to be compiled, studied and published, in the same way we would share material found at an archeological dig or written documents from an historical archive.

Finally, those of us who work with this type of image consider it an act of social justice to return them to the community that produced them, that truly owns them. However, we return something that has been enriched by the hierarchy newly acquired through the transformation of these images into an object of knowledge and study, a sort of cultural heritage, so to speak. Thus these images become the graphic and sentimental memory of a collective whose cohesion is reinforced by their existence.

Initiatives of this type exist everywhere, although they do not always manage to develop the full potential stored within old photographs. The formation of multidisciplinary work teams that include historians and ethnographers familiar with local intra-history could be the key to successfully publishing work that would otherwise be converted into mere catalogs of orphaned images, macabre galleries exhibiting, as if embalmed, anonymous, unknown, dead people. Mere fetishes.

A small example of a local publication using old photographs as axial argument, which we think has achieved satisfactory results, is the project titled Recovered Memories. Photography and Society in Aspe 1870-1976. Field work begun in 1996 and still ongoing, has discovered and documented almost 4,000 images that have been recovered and selected from the private photographic repertoire generated by a small, southeastern Spanish urban community for over a century. The photographs have been classified into 24 different thematic categories that do not lost sight of the transversality of the contents that emerge from the photographs, which are teeming with sociological, anthropological and historical information.

Nazarenes, carrying the cross on their shoulders during the morning procession on Good Friday in Aspe (Spain).

(Photographer unknown, around 1955/Felipe Mejías, March 2015).

From an historian or archeologist’s point of view, it would have been unforgiveable not to try to find new ways to learn about the past with such valuable resources at hand. This is the point where rephotography begins.

It comes as no surprise to find that there are already masters of this relatively young discipline. However, there are only two things you can do with the work of Mark Klett and Camilo José Vergara watch and learn. Sergey Larenkov, Ricard Martínez, Hebe Robinson, Irina Werning, Gustavo Germano and Douglas Levere also produce work that comes very close to visual poetry. Many of them also enter the realm of social and political denunciation, making it quite clear that rephotography is not only a form of technical and aesthetic entertainment, but also a tool that helps us stop and reflect on the collateral damage associated with the passage of time.

But why rephotography? For someone who constantly thinks about the consequences and meaning of the passage of time, it is particularly gratifying to intervene in the process of creating an unattainable fiction through photography: blending the past and the present into a unique instant, taking on the role of a mischievous god in the age-old quest for immortality. Cernuda used to say: “[...] times are identical / gazes are different [...],” and something of this inspiration lurks beneath the ultimate goal of rephotography, attempting to stop and mix time, perceiving it without its having passed, or rather, perceiving if as if it had not done so. Making time manageable, cyclical and malleable is an heroic, almost obsessive exercise that goes beyond the purely visual mannerist trompe-l’oeil to reveal a little of the artifice behind the deception. The point is to photograph what other eyes before ours saw, in the same place, in the same instant, using the same technique. It is as if we brought the original photographer back to life and had him beside us, whispering the correct focus into our ear. Furthermore, if we do it in the place where we were born and raised, we can sublimate the nostalgic component each rephotograph inevitably contains: being right now where someone was long before us and seeing, touching and smelling the same environment. Feeling the same as that person. Being that person.

Overlapping, contrasting, recreating through transparencies and seeing how the different layers of memory deposited over the years, flourish and contribute to the task of creating the illusion that the old and new images are actually different sides of the same reality. A new discourse about the obvious contrast between the past and present, what is and what is not, is created, runs the risk of getting stuck at the anecdotal level. Even so, it may be enough. Although it is possible to try something else: building an imaginary cage in which to enclose two similar instances separated by time in the hope that they can live together and perhaps end up becoming a single moment. Just like in the Frankenstein myth, we give birth to impossible, two-headed monsters, Siamese twins that must always share different moments of the same existence. We give them a voice, and the possibility of shouting and discovering what is hidden within; their wrinkles, how the space or person has aged; what remains of what they once were. The experiment is not always successful, but it sometimes works and eventually creates a new scene where everything fits together marvelously; shapes continue and intertwine without signaling eras; grays and colors merge into a single light. It is a small miracle fixed in a subtle, crystalline, almost imperceptible balance.

But let us not deceive ourselves. In reality everything is always the past. The unattainable past. We like to think that rephotography gives us the possibility of returning to the past, to rethink it and try to bring it back to life. Poor fools, as if we could bring it back to a time and place it actually never left.

Felipe Mejías López (Spain, 1968). Lives and works in Spain. Historian and archaeologist. BA in Geography and History with a major in Art History from the University of Valencia. MA in Professional Archaeology and Heritage Management from the University of Alicante. A lot of his publications revolve around the archaeological, historical, artistic, documentary and photographic heritage of his native town, Aspe. Currently, he is editing the third volume of his research project on ancient photography and social history Recovered Memories. For this project, he studied the field of rephotography.

Felipe Mejías López (Spain, 1968). Lives and works in Spain. Historian and archaeologist. BA in Geography and History with a major in Art History from the University of Valencia. MA in Professional Archaeology and Heritage Management from the University of Alicante. A lot of his publications revolve around the archaeological, historical, artistic, documentary and photographic heritage of his native town, Aspe. Currently, he is editing the third volume of his research project on ancient photography and social history Recovered Memories. For this project, he studied the field of rephotography.

Penitents of the brotherhood of Sorrows, posing with the image of the Virgin during the Easter Week in Aspe (Spain).

March 1929. (Photographer unknown. About photograhy Felipe Mejías, March 2015).

Paper memories. Photographs will always be paper memories, despite the fact that the emergence of digital technology in the world of images has changed the way they are stored. In any case, whether they are stuck in an album, crammed into an old biscuit tin, or stored in a virtual folder tucked away in the darkest corner of our computer’s hard drive, the construction of our memories owes a great deal to these images in black and white or faded colors. We can often reconstruct the exact layout of a place we have been, or feel the gaze of a friend or family member we no longer see because we can re-encounter them when we contemplate these square cardboard remnants. Memory cards and smart phones belong to a different visual universe that has no history but is a slave to the future, subject to a dictatorship that imposes the objective of immediacy and the compulsive desire to devour the overwhelming reality that surrounds us as if it might suddenly and permanently disappear from one moment to the next.

Photographs take us back to what we once were, in a constant, palpable, evident graphic salvation that is fed by our gaze like a fossil into which we breathe life simply by contemplating it. Looking at photos makes us grow, whether or not we want to, because we end up recognizing ourselves in them, somehow transformed into strangers we find it increasingly difficult to recognize: yet, there we are, participating like enthusiastic actors or perhaps behind the viewfinder snapping a photo. This tangible, visual certainty, together with the awareness that time has passed because we remember, creates an incredibly strong sensory cement that binds and gives meaning to our life stories.

But if we broaden the focus and think about our innumerable private –and therefore secret– photographs as a whole that have been collected since the beginning of photography, scattered throughout our immediate environment (not only in our family or neighborhood, but also throughout the macro scale of the city or region where we live), then these images evolve from more than a repertoire of personal memories to cultural objects. And as such, because of the historical, anthropological and ethnological information they contain, these photographs become unique, inimitable objects that deserve to be compiled, studied and published, in the same way we would share material found at an archeological dig or written documents from an historical archive.

Finally, those of us who work with this type of image consider it an act of social justice to return them to the community that produced them, that truly owns them. However, we return something that has been enriched by the hierarchy newly acquired through the transformation of these images into an object of knowledge and study, a sort of cultural heritage, so to speak. Thus these images become the graphic and sentimental memory of a collective whose cohesion is reinforced by their existence.

Initiatives of this type exist everywhere, although they do not always manage to develop the full potential stored within old photographs. The formation of multidisciplinary work teams that include historians and ethnographers familiar with local intra-history could be the key to successfully publishing work that would otherwise be converted into mere catalogs of orphaned images, macabre galleries exhibiting, as if embalmed, anonymous, unknown, dead people. Mere fetishes.

A small example of a local publication using old photographs as axial argument, which we think has achieved satisfactory results, is the project titled Recovered Memories. Photography and Society in Aspe 1870-1976. Field work begun in 1996 and still ongoing, has discovered and documented almost 4,000 images that have been recovered and selected from the private photographic repertoire generated by a small, southeastern Spanish urban community for over a century. The photographs have been classified into 24 different thematic categories that do not lost sight of the transversality of the contents that emerge from the photographs, which are teeming with sociological, anthropological and historical information.

Nazarenes, carrying the cross on their shoulders during the morning procession on Good Friday in Aspe (Spain).

(Photographer unknown, around 1955/Felipe Mejías, March 2015).

From an historian or archeologist’s point of view, it would have been unforgiveable not to try to find new ways to learn about the past with such valuable resources at hand. This is the point where rephotography begins.

It comes as no surprise to find that there are already masters of this relatively young discipline. However, there are only two things you can do with the work of Mark Klett and Camilo José Vergara watch and learn. Sergey Larenkov, Ricard Martínez, Hebe Robinson, Irina Werning, Gustavo Germano and Douglas Levere also produce work that comes very close to visual poetry. Many of them also enter the realm of social and political denunciation, making it quite clear that rephotography is not only a form of technical and aesthetic entertainment, but also a tool that helps us stop and reflect on the collateral damage associated with the passage of time.

But why rephotography? For someone who constantly thinks about the consequences and meaning of the passage of time, it is particularly gratifying to intervene in the process of creating an unattainable fiction through photography: blending the past and the present into a unique instant, taking on the role of a mischievous god in the age-old quest for immortality. Cernuda used to say: “[...] times are identical / gazes are different [...],” and something of this inspiration lurks beneath the ultimate goal of rephotography, attempting to stop and mix time, perceiving it without its having passed, or rather, perceiving if as if it had not done so. Making time manageable, cyclical and malleable is an heroic, almost obsessive exercise that goes beyond the purely visual mannerist trompe-l’oeil to reveal a little of the artifice behind the deception. The point is to photograph what other eyes before ours saw, in the same place, in the same instant, using the same technique. It is as if we brought the original photographer back to life and had him beside us, whispering the correct focus into our ear. Furthermore, if we do it in the place where we were born and raised, we can sublimate the nostalgic component each rephotograph inevitably contains: being right now where someone was long before us and seeing, touching and smelling the same environment. Feeling the same as that person. Being that person.

Overlapping, contrasting, recreating through transparencies and seeing how the different layers of memory deposited over the years, flourish and contribute to the task of creating the illusion that the old and new images are actually different sides of the same reality. A new discourse about the obvious contrast between the past and present, what is and what is not, is created, runs the risk of getting stuck at the anecdotal level. Even so, it may be enough. Although it is possible to try something else: building an imaginary cage in which to enclose two similar instances separated by time in the hope that they can live together and perhaps end up becoming a single moment. Just like in the Frankenstein myth, we give birth to impossible, two-headed monsters, Siamese twins that must always share different moments of the same existence. We give them a voice, and the possibility of shouting and discovering what is hidden within; their wrinkles, how the space or person has aged; what remains of what they once were. The experiment is not always successful, but it sometimes works and eventually creates a new scene where everything fits together marvelously; shapes continue and intertwine without signaling eras; grays and colors merge into a single light. It is a small miracle fixed in a subtle, crystalline, almost imperceptible balance.

But let us not deceive ourselves. In reality everything is always the past. The unattainable past. We like to think that rephotography gives us the possibility of returning to the past, to rethink it and try to bring it back to life. Poor fools, as if we could bring it back to a time and place it actually never left.

Felipe Mejías López (Spain, 1968). Lives and works in Spain. Historian and archaeologist. BA in Geography and History with a major in Art History from the University of Valencia. MA in Professional Archaeology and Heritage Management from the University of Alicante. A lot of his publications revolve around the archaeological, historical, artistic, documentary and photographic heritage of his native town, Aspe. Currently, he is editing the third volume of his research project on ancient photography and social history Recovered Memories. For this project, he studied the field of rephotography.

Felipe Mejías López (Spain, 1968). Lives and works in Spain. Historian and archaeologist. BA in Geography and History with a major in Art History from the University of Valencia. MA in Professional Archaeology and Heritage Management from the University of Alicante. A lot of his publications revolve around the archaeological, historical, artistic, documentary and photographic heritage of his native town, Aspe. Currently, he is editing the third volume of his research project on ancient photography and social history Recovered Memories. For this project, he studied the field of rephotography.Mónica Sánchez Escuer

Time is creation, argued Henri Bergson: “The more we explore the nature of time, the more we will understand how duration means invention, creation of forms and continuous production of the absolutely new.” (2007, p. 30).

Only insofar as time is perceived and received does it exist and acquire meaning for man. Photography and literature are two artistic media through which humanity has recreated duration and development. Both disciplines encapsulate instants: literature, a sequence of them, and photography a single instant that reveals or implies a before and an after. They capture time to show a legible fragment of its movement. Regardless of whether what they depict and relate is real or fiction, a text or a photograph bears the traces of the passage of time.

The two languages represent this passage through various forms and processes, based on the position, movement and speed of the observer-narrator, which can broadly be summarized in three moments: 1] stopped time: a literary vignette or frozen image of a scene in which the objects and/or characters are time frames depicting something that happened or is about to happen; 2] the visual tour from a fixed point: images or texts that draw the gaze or reading towards the various focal points of a panoramic photo or a written narrative, generally in the present, in which the narrator reveals to the reader the space-time in which the action takes place through descriptions; and 3] movement: where the actions of the story comprised in an objective period of time, including the stream of consciousness, are visually narrated and represented.

The reality described or depicted in photography and literature is not only an interpretation of the facts but also of their duration and the continuous movement of the story and the events contained in it. In both disciplines, time is a reference, structure and metaphor. It is a fundamental part of the framework of both media, and is also represented and reconfigured as an image of the expression of literary and photographic discourses. It cannot be explained or demonstrated: “The artist who works with photography or stories does not provide solutions, but rather answers people's questions with another question, a more refined, aesthetic one: a doubt answered with a metaphor.” (López Aguilar, 2002).

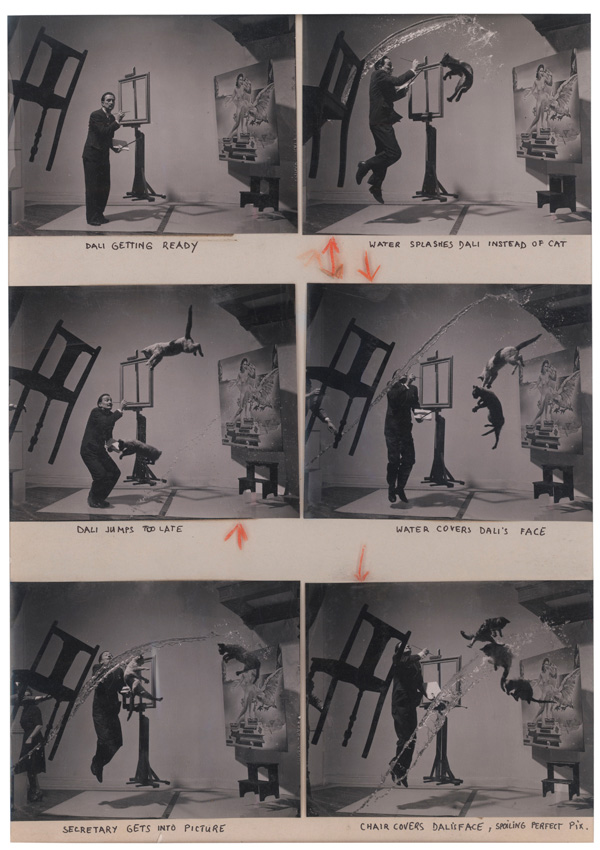

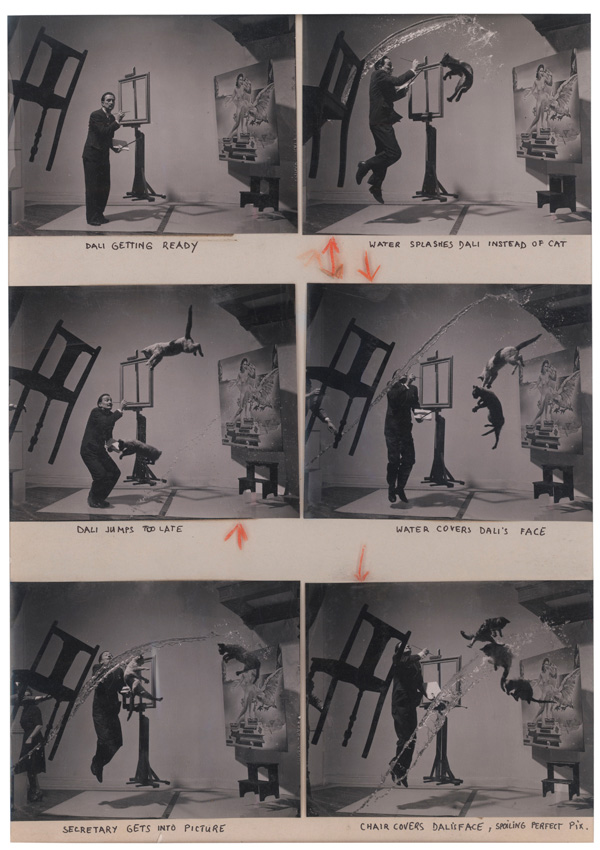

Salvador Dali, 1948. Phillipe Halsman/Magnum Photos

The narrative construction of time in the image

In photography, the artist chooses the setting, frame and significant object inside the visual narrative he or she wishes to convey. When actions or movement are directly involved, he or she chooses and captures the "decisive moment" in which the Barthesian punctum is unveiled, the point at which all the elements, signs and marks that lend meaning to the image are incorporated.

Photographic discourse, like many artistic languages, has a double spatiality and temporality: on the one hand, it constitutes a two-dimensional space [s1] that represents an illusory, three-dimensional space [s2]. On the other hand, there is the time of representation [t1] – that is, the real time when the photograph was taken –, and the time represented in the image [t2].

Time in a photograph is constructed by linking various elements that can be observed on different levels. These elements include rhythm, tension, sequentiality, the representation of duration and references to the definition of space.

The space and time of representation are fundamental elements of photographic composition: on the one hand perspective, depth of field, interplay of plans, balance, proportion, visual tour, iconic order, tension and rhythm; and on the other instantaneity, longevity, sequentiality, symbolic and subjective times and narrative. Perspective and various planes create perceptual gradients that construct the three-dimensional space and movement in the images. The rhythm is observed through the repetition of elements and the way they are organized in the composition. Saturation, empty spaces and the distribution of tones determine the pace of a photograph. Tension is created by various elements: the lines that express movement, the contrast between regular geometric shapes, the sweeps, angles, perspective, chromatic contrast, lighting and textures of the image. The visual weight of each of the elements, determined by their size and position in the different planes of the photographs, can provide a spatial-temporal hierarchy, whereby more important elements in the foreground are equivalent to the present in the narration of the image. The point of view is expressed through the field of vision, the angle from which the photograph is taken, and the selection of objects shown with clarity and closeness, or that remain in the middle ground or background. The photograph suggests a visual tour, a dynamic order of interpretation established by the composition that can indicate a timeline.

At a technical level, the time dimension is produced by the shutter speed. If the photographer wishes to project an instant, to freeze time, he or she will use a fast speed to capture a scene in a fraction of a second, which in literature would be depicted in a vignette. If, alternately, he or she wishes to depict duration, a low speed allows a long exposure times that create effects in the image, such as the sweep in a moving subject. The presence of certain elements such as clocks, calendars, old objects and even photographs are indicators of time that lead the viewer to interpret the image as duration or sequentiality. Some photographers prefer to convey the opposite, a timeless situation, and to do so deliberately conceal any mark that might indicate the historical time or moment when the photograph was taken. Erasing the traces of time is a discursive effect that has been used since classical representation and “is intended to strengthen the illusion of reality (Marzal Felici, 2011, p. 215).

However, an image can express much more than a fragment of reality. It can be a metaphor in itself, and its content may be symbolic, as will also be the time within it. In the case of abstract photographs, for example, in which spatio-temporal marks are concealed, their discourse is closer to poetry, with a necessarily individual interpretation. The perception of time and space within them is subjective. The Barthesian punctum relates to the presence of a subjective time, the element that bursts into the time flow of interpreting the image. It moves or affects the viewer at a very personal level, based on their previous experience.

Another aspect in which the time characteristics of a photograph can be analyzed is sequentiality1, both in its elements within a single image, [such as its order and layout], and in the succession of photographs in polyptychs depicting a sequential scene. The illustrative dimension of the image comprises the central elements of narrative: point of view, characters, authenticity, textual marks and enunciation.

The narrative of the image is constructed by the morphological, compositional and illustrative elements, which together convey a specific overall temporal effect. The point of view from which a story is narrated is crucial and, in photography, can be clearly observed in the framing, the position of the photographer and the angle from which it is taken [the result of selecting a determined space and time]. The framing evokes the artist’s way of looking and choosing which part of the world is worth stopping, closely observing and relating.