Sad memories revisited, a confrontation with Zbigniew Libera's "Positives"

Zbigniew Libera (Pabianice, 1959) is a Polish artist who is not afraid of pushing boundaries, by creating provocative work that challenges the canonical narratives of our contemporary culture. He is known internationally for his work LEGO (1996), a limited edition of three LEGO sets of a concentration camp, that provoked a media controversy at the Venice Biennale of 1997. The curator of the Polish pavilion, Jan Stanisław Wojciechowski, refused to present it, saying the work treated one of the darkest moments in European civilization in a too frivolous manner.1

LEGO. Zbigniew Libera, 1996.

LEGO. Zbigniew Libera, 1996.

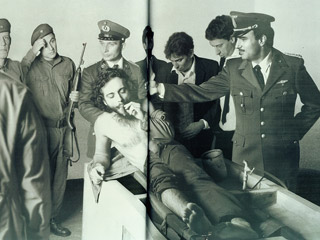

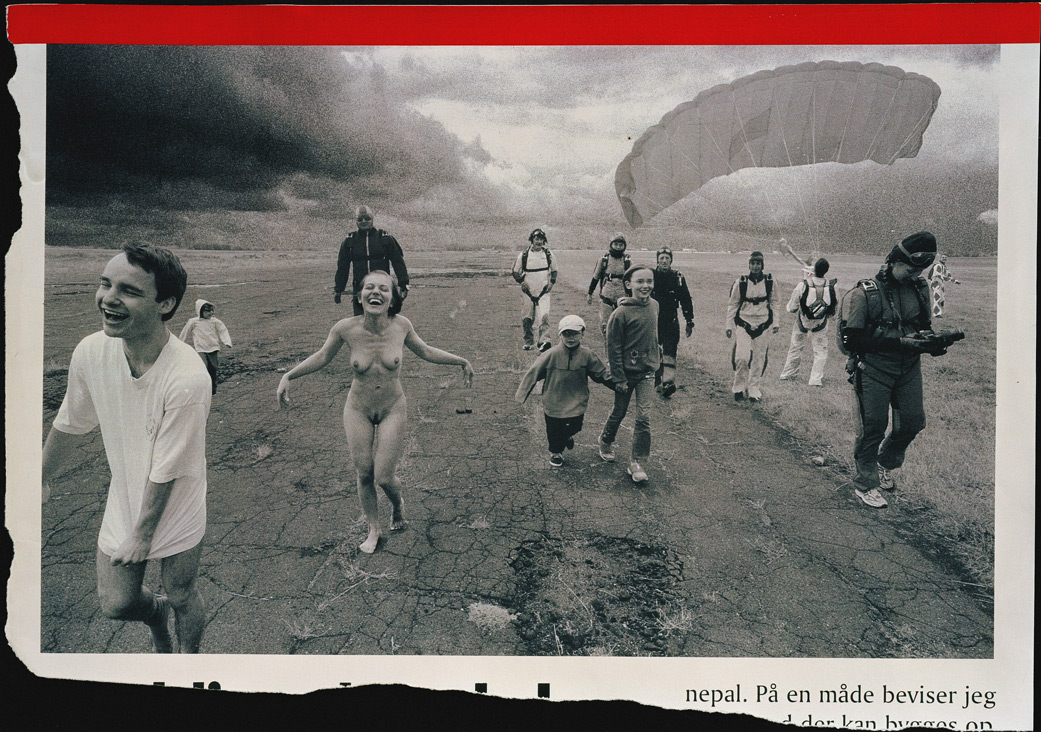

In 2002-2003 Libera made the series Positives, which he described as "another attempt at playing with trauma".2 For this series, he selected traumatic iconic photographs from recent history and made a positive version of them. The photo of a naked Vietnamese girl, running away from the village of Trang Bang after the napalm bombing in 1972, has been changed into a positive image of a nude and smiling woman; a group of concentration camp prisoners have been replaced by smiling figures in striped costumes.3

Positives. Zbigniew Libera, 2002-2003.

Positives. Zbigniew Libera, 2002-2003.

At first sight, we could state that this series is, like LEGO, a too frivolous approach of some of the traumatic episodes of our recent history. Some of the people who went through these horrors are still alive. Is it not disrespectful to confront them with a positive reinterpretation of their suffering? And to what end? What is Libera trying to say with this work? Is he just trying to be controversial or is there a more profound reasoning behind it?

In an interview with Katarzyna Bielas and Dorota Jarecka, from the Polish newspaper Gazeta Wyborcza, Libera said:

It seems to me that nowadays we don’t want to know what reality is like, we want to experience it positively. That’s why the prisoners became inhabitants, those were sad, these are glad. On the other hand it can be the mechanism of Nazi or Soviet propaganda, which changed reality into the set of optimistic slogans.4

On the one hand, it’s true that the market is providing us with a flood of glamorous and positive images. While there are plenty of serious issues asking for our attention —like climate change, armed conflicts, inequality— it is easy to get lost in the latest news about celebrities and fashion trends.5 On the other hand, the opposite is certainly as true, if not more so. Everyday we are flooded by shocking, sad, and negative images of people being decapitated by terrorists and refugees fleeing conflicted areas. Just think of the image of Aylan, the little Syrian boy who drowned in an attempt to reach the shores of Europe. This image was in the news for days and was widely disseminated by the social media. In this case, the so-called harsh reality was not ignored or concealed by optimistic slogans, but rather magnified and used as a moral appeal and tool for political action.

Kid Aylan Kurdi. 2015.

In an interview with Hedvig Turai from Art Margins, Libera gave another, more interesting explanation for Positives:

You have all those traumatic pictures that I am sure no one is able to consume and digest. You cannot live with them (…). I think that people instinctively do not want to look at these pictures, like that of the Vietnamese girl injured by napalm. We have various blocks. And the photo is blocked.6

By confronting us with a positive version of the traumatic photos, Libera hopes to unblock the original negative, so we can feel their impact again.7

One can wonder if everybody is experiencing this psychological block, but if we reflect a little bit more on the idea of iconic photographs being blocked, we could say that there’s also another kind of block which arises over the years, when a photo is used over and over again as an educational and political tool, and has become part of a fixed narrative. We have learned to look and interpret our past through these iconic photographs and it has become difficult to just see them by themselves without thinking of the narratives we’ve constructed around them. In the interview mentioned above, Libera says:

We never see anything for the first time, we always look at an object and we come back to the picture we saw of this object the previous time. We always make one step back into memory, back to the previous picture. We always view our own memories of things, and not the things themselves. It is like one very long permanent journey into our memory. I tried to nail down this process of seeing and remembering.8

What Libera says here about always viewing our memories of things and not the things themselves is certainly true. Personally, when I see the photos on which the positive Residents is based, I immediately recall the education I’ve had about the Holocaust, all the films and books I’ve seen and read about this theme, and the yearly commemorations of the horrors of World War II; and I cannot see these images without thinking about the lesson I was taught: "We cannot let this happen ever again". Although there is nothing wrong with that lesson, it makes you think of the power iconic images have; some more reflection on that wouldn’t be bad.

Residents. Zbigniew Libera.

Coming back to the question if there is more to the work Positives than just controversy, I think we can reasonably answer that in the affirmative, although his method might not be the most sensitive one. The Czech photographer Pavel Maria Smejlik, who is playing a similar game of seeing and remembering with his series Fatescapes (2009-2010), has a more subtle approach: he also selected iconic (war) images but instead of making their positive counterpart, he took out the central motifs and people.9 If we assume that this kind of traumatic images are blocked, this would be another way of unblocking them but then without the initial shock of seeing their positive reinterpretation.

Fatescapes. Pavel Maria Smejkal, 2009-2010.

Whatever one’s personal preference, Libera’s work doesn’t leave one indifferent. Positives challenges us to ask ourselves if we really have observed the iconic photos that surround us and if we’ve reflected upon the narratives connected to them. The dialogue that this series might inspire about the fixed narratives related to these iconic images, is a valuable one that we should have more often.

1. http://articles.latimes.com/1997-05-19/news/mn-60350_1_lego-toys

2. http://raster.art.pl/gallery/artists/libera/prace.htm

3. http://www.artmargins.com/index.php/archive/166-the-artist-does-not-own-his-interpretations-hedvig-turai-in-conversation-with-zbigniew-libera

4. http://maurycy.atlas.com.pl/ang.nsf/0/46CD099B0570C5CBC1256E37004D54D4?OpenDocument

5. Un comentario interesante sobre este fenómeno es “Simple Living “ de Nadia Plesner: http://www.nadiaplesner.com/simple-living--darfurnica1

6. http://www.artmargins.com/index.php/archive/166-the-artist-does-not-own-his-interpretations-hedvig-turai-in-conversation-with-zbigniew-libera

7. http://deruimtemaker.nl/2013/02/27/spelen-met-iconen-uit-de-fotografie/

8. http://www.artmargins.com/index.php/archive/166-the-artist-does-not-own-his-interpretations-hedvig-turai-in-conversation-with-zbigniew-libera

9. http://www.pavelmaria.com/fatescapestext2.html

Annemarie Bas (The Netherlands, 1986), has a Bachelor’s degree in History at the University of Utrecht and a Master’s degree in Cultural History at the same institution. As a historian, she worked as a junior researcher at the Museum of Psychiatry "Het Dolhuys" in Haarlem, The Netherlands. Since 2013, she lives and works in Mexico City. At the moment, she is international liaison at ZoneZero and works as an independent translator.

Annemarie Bas (The Netherlands, 1986), has a Bachelor’s degree in History at the University of Utrecht and a Master’s degree in Cultural History at the same institution. As a historian, she worked as a junior researcher at the Museum of Psychiatry "Het Dolhuys" in Haarlem, The Netherlands. Since 2013, she lives and works in Mexico City. At the moment, she is international liaison at ZoneZero and works as an independent translator.