Elisa Rugo

One of the greatest advantages of current photography, through its democratization as a tool and the technological advances in the media, is the guiding thread it establishes for collective representations in visual communication. This is largely the result of databases generated using key words, which provide information by describing and facilitating the identification of files and content. One of the most effective uses of this is the ubiquitous hashtag in social networks (Twitter, Instagram, Tumblr, FB). Eight years after Messina1 using the hashtag to group dialogues in social networks, this resource has produced endless possibilities not only for political and commercial marketing campaigns, but also for categorizing and linking information in a virtual world with millions of simultaneous thematic connections. It has served to increase the understanding of communities that would otherwise be hard to reach, which documentary photographers wish to comprehend and stop portraying from a distance.

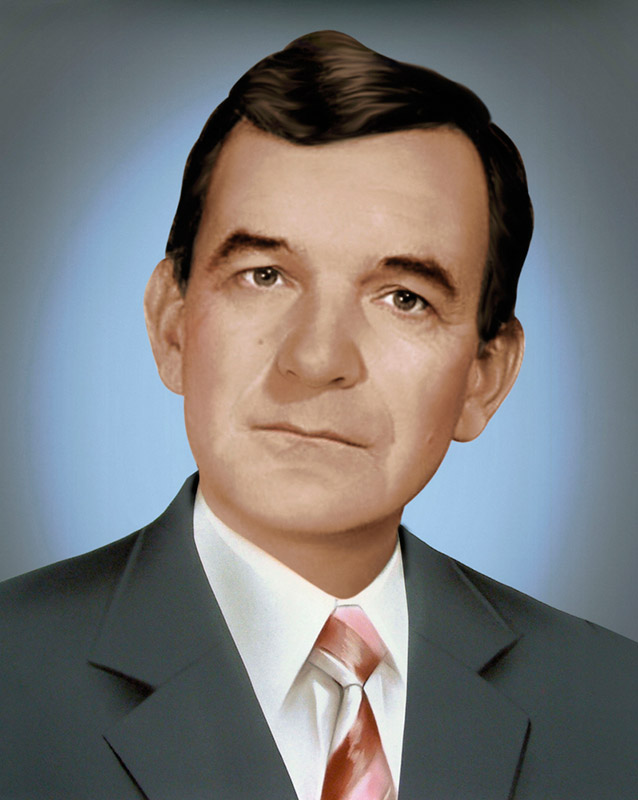

everydayafrica. #Lagos fragment. Photo by Tom Saater @tomsaater

To what extent can one formalize and give presence and solidity to a proposal that derives from collaboration and the use of a social network?

Throughout its history, photography has been related to the personal and collective memory. This text will not tackle the debate regarding whether it is a reliable testimony of current reality, but rather concentrate on what visual language is doing, creating, recreating and communicating in the present. One of the current tools to trigger this dialogue is the hashtag, as a complement to the photographic image that has transformed everyday communication and has become a simple, inexpensive, everyday action on a massive, global scale. Simply accompanying an image by two or three words preceded by a hashtag enables others to access photograph albums categorized by location, topic, mood or format (#streetartchilango); to travel and identify in real time to these communities so far removed from our everyday lives yet so close to our language (everydayafrica, everydayiran) , or to concentrate a story in citizen testimonials and produce social movements, thus raising awareness and mobilizing resources in real life (#Egipto, #IranElection, #15-M, #BringBackOurGirls, #YoSoy132). This allows the hashtag to community gaze, offer a panorama of the phenomenon and collective representation online, and show its integrating function. But how can it be conserved?

everydayiran. Young women taking a selfie in the Bazaar of #Isfahan. #Iran. Photo by Aseem Gujar @myaseemgujar

Only two years ago, hashtags were not perceived as content networks, but studied from a mass perspective, leading to the highly ephemeral trending topics. However, there is increasing interest in researching and analyzing this kind of connections, to better understand the social, political, commercial circumstances, and of course, go beyond borders to learn about local and even personal events.

The archives produced by hashtags are real-time records and documents in the cloud that we fear so much, and where we find so it hard to place our entire body of work. It contains our everyday communication and, even if we are not aware of what we deliver, our way of seeing and thinking are latent within it. One option to preserve all this archive would be to produce a local database, or to continue to entrust this virtual universe with our history, to share, modify, increase, exchange, store, read, reread or even eliminate it.

The hashtag can therefore be considered an extension of the light Barthes called the umbilical cord, 2 the skin that we share with those who have photographed themselves to share who they are, what they do and how they live; to represent themselves and join this globalized digital world of metadata in which the photographer is no longer the only means of objective or subjective expression of reality, but now feeds into various disciplines and mediums that democratize it as a tool and a language in itself.

1. Chris Messina, an active defender of open code, suggested using the name hashtag on August 23, 2007, with a simple tweet: "How do you feel about using # (pound) for groups? As in #barcamp [msg]?".

2. A real body, located there, produced radiation that impressed me, located here. It does not matter how long the transmission lasts; the photo of the disappeared being impresses me as would the deferred rays of a star. A kind of umbilical cord joins the body of the object photographed to my gaze: light, though impalpable, is a carnal medium, a skin I share with the beings who have been photographed. – R. Barthes.

Elisa Rugo (México, 1980). Lives and works in Mexico. She is a photographer, videographer and a specialist in visual communication with a degree in Creative Visualisation at the University of Communication. In 2012, she took part in the seminar Contemporary Photography at the Image Centre. She has participated in collective exhibitions in Pachuca, Querétaro, Guadalajara and Mexico-City. At the moment, she is the art director of the websites fpmeyer.com and museodemujeres.com and she is part of the editorial team of zonezero.com. You can see her work at: elisarugo.pro

Elisa Rugo (México, 1980). Lives and works in Mexico. She is a photographer, videographer and a specialist in visual communication with a degree in Creative Visualisation at the University of Communication. In 2012, she took part in the seminar Contemporary Photography at the Image Centre. She has participated in collective exhibitions in Pachuca, Querétaro, Guadalajara and Mexico-City. At the moment, she is the art director of the websites fpmeyer.com and museodemujeres.com and she is part of the editorial team of zonezero.com. You can see her work at: elisarugo.proOne of the greatest advantages of current photography, through its democratization as a tool and the technological advances in the media, is the guiding thread it establishes for collective representations in visual communication. This is largely the result of databases generated using key words, which provide information by describing and facilitating the identification of files and content. One of the most effective uses of this is the ubiquitous hashtag in social networks (Twitter, Instagram, Tumblr, FB). Eight years after Messina1 using the hashtag to group dialogues in social networks, this resource has produced endless possibilities not only for political and commercial marketing campaigns, but also for categorizing and linking information in a virtual world with millions of simultaneous thematic connections. It has served to increase the understanding of communities that would otherwise be hard to reach, which documentary photographers wish to comprehend and stop portraying from a distance.

everydayafrica. #Lagos fragment. Photo by Tom Saater @tomsaater

To what extent can one formalize and give presence and solidity to a proposal that derives from collaboration and the use of a social network?

Throughout its history, photography has been related to the personal and collective memory. This text will not tackle the debate regarding whether it is a reliable testimony of current reality, but rather concentrate on what visual language is doing, creating, recreating and communicating in the present. One of the current tools to trigger this dialogue is the hashtag, as a complement to the photographic image that has transformed everyday communication and has become a simple, inexpensive, everyday action on a massive, global scale. Simply accompanying an image by two or three words preceded by a hashtag enables others to access photograph albums categorized by location, topic, mood or format (#streetartchilango); to travel and identify in real time to these communities so far removed from our everyday lives yet so close to our language (everydayafrica, everydayiran) , or to concentrate a story in citizen testimonials and produce social movements, thus raising awareness and mobilizing resources in real life (#Egipto, #IranElection, #15-M, #BringBackOurGirls, #YoSoy132). This allows the hashtag to community gaze, offer a panorama of the phenomenon and collective representation online, and show its integrating function. But how can it be conserved?

everydayiran. Young women taking a selfie in the Bazaar of #Isfahan. #Iran. Photo by Aseem Gujar @myaseemgujar

Only two years ago, hashtags were not perceived as content networks, but studied from a mass perspective, leading to the highly ephemeral trending topics. However, there is increasing interest in researching and analyzing this kind of connections, to better understand the social, political, commercial circumstances, and of course, go beyond borders to learn about local and even personal events.

The archives produced by hashtags are real-time records and documents in the cloud that we fear so much, and where we find so it hard to place our entire body of work. It contains our everyday communication and, even if we are not aware of what we deliver, our way of seeing and thinking are latent within it. One option to preserve all this archive would be to produce a local database, or to continue to entrust this virtual universe with our history, to share, modify, increase, exchange, store, read, reread or even eliminate it.

The hashtag can therefore be considered an extension of the light Barthes called the umbilical cord, 2 the skin that we share with those who have photographed themselves to share who they are, what they do and how they live; to represent themselves and join this globalized digital world of metadata in which the photographer is no longer the only means of objective or subjective expression of reality, but now feeds into various disciplines and mediums that democratize it as a tool and a language in itself.

1. Chris Messina, an active defender of open code, suggested using the name hashtag on August 23, 2007, with a simple tweet: "How do you feel about using # (pound) for groups? As in #barcamp [msg]?".

2. A real body, located there, produced radiation that impressed me, located here. It does not matter how long the transmission lasts; the photo of the disappeared being impresses me as would the deferred rays of a star. A kind of umbilical cord joins the body of the object photographed to my gaze: light, though impalpable, is a carnal medium, a skin I share with the beings who have been photographed. – R. Barthes.

Elisa Rugo (México, 1980). Lives and works in Mexico. She is a photographer, videographer and a specialist in visual communication with a degree in Creative Visualisation at the University of Communication. In 2012, she took part in the seminar Contemporary Photography at the Image Centre. She has participated in collective exhibitions in Pachuca, Querétaro, Guadalajara and Mexico-City. At the moment, she is the art director of the websites fpmeyer.com and museodemujeres.com and she is part of the editorial team of zonezero.com. You can see her work at: elisarugo.pro

Elisa Rugo (México, 1980). Lives and works in Mexico. She is a photographer, videographer and a specialist in visual communication with a degree in Creative Visualisation at the University of Communication. In 2012, she took part in the seminar Contemporary Photography at the Image Centre. She has participated in collective exhibitions in Pachuca, Querétaro, Guadalajara and Mexico-City. At the moment, she is the art director of the websites fpmeyer.com and museodemujeres.com and she is part of the editorial team of zonezero.com. You can see her work at: elisarugo.proVanessa Alcaíno & Elisa Rugo

That which I call my self-portrait is composed of thousands of days of work.

Each of them corresponds to the exact number and moment at which

I stopped as I painted after a task.

—Roman Opalka

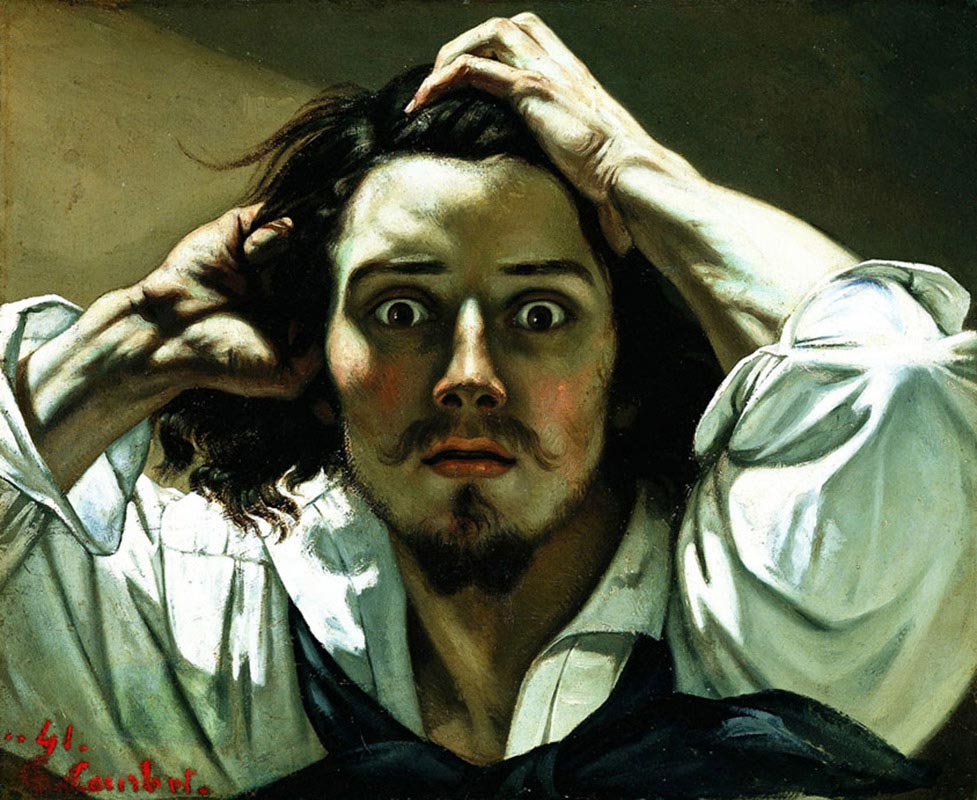

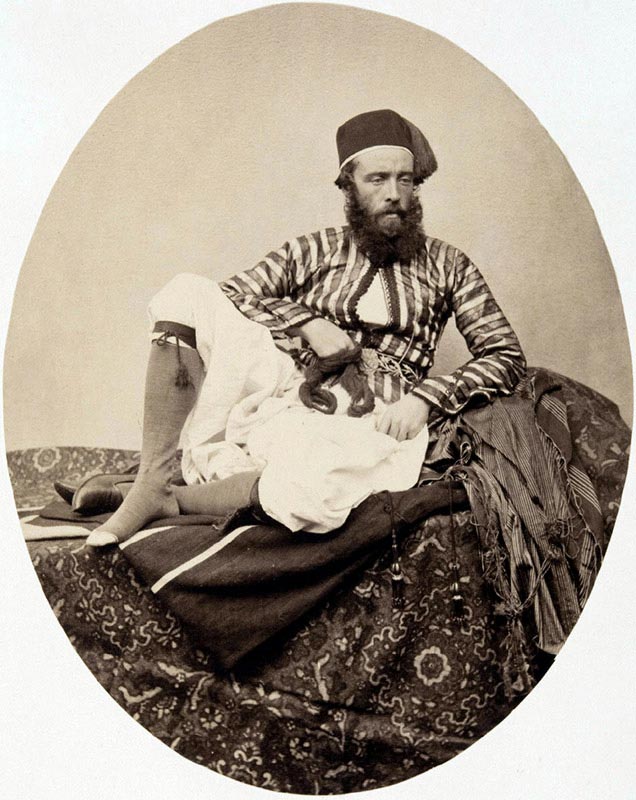

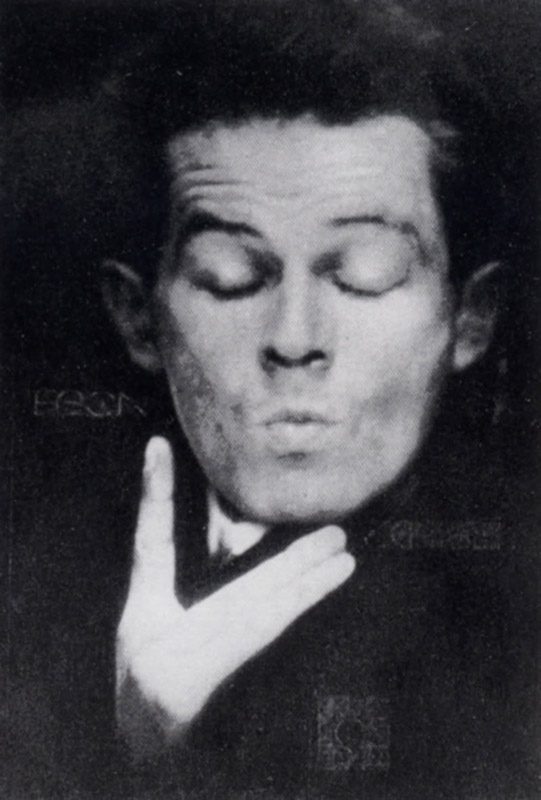

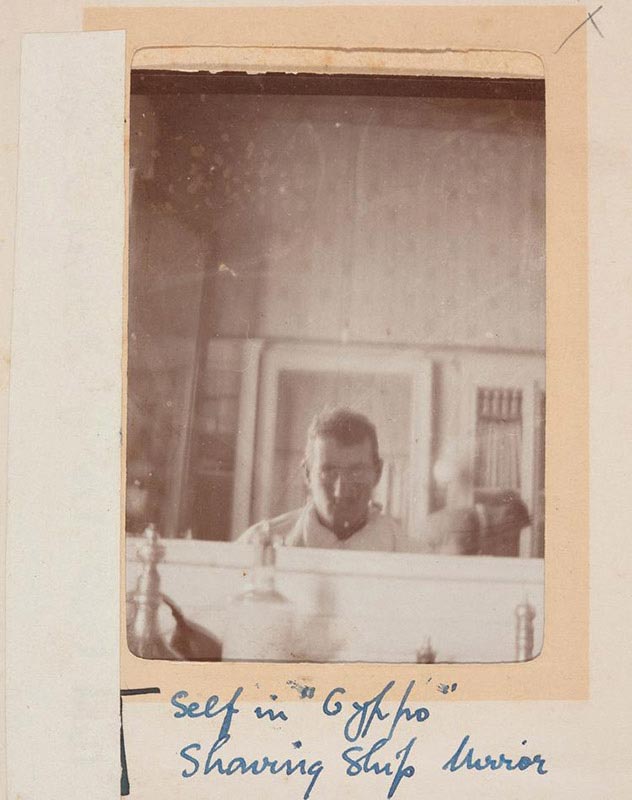

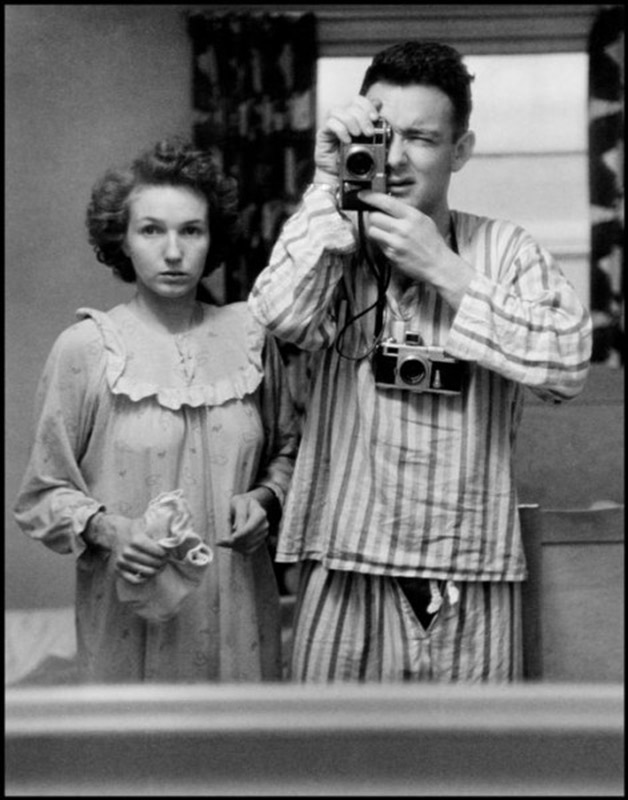

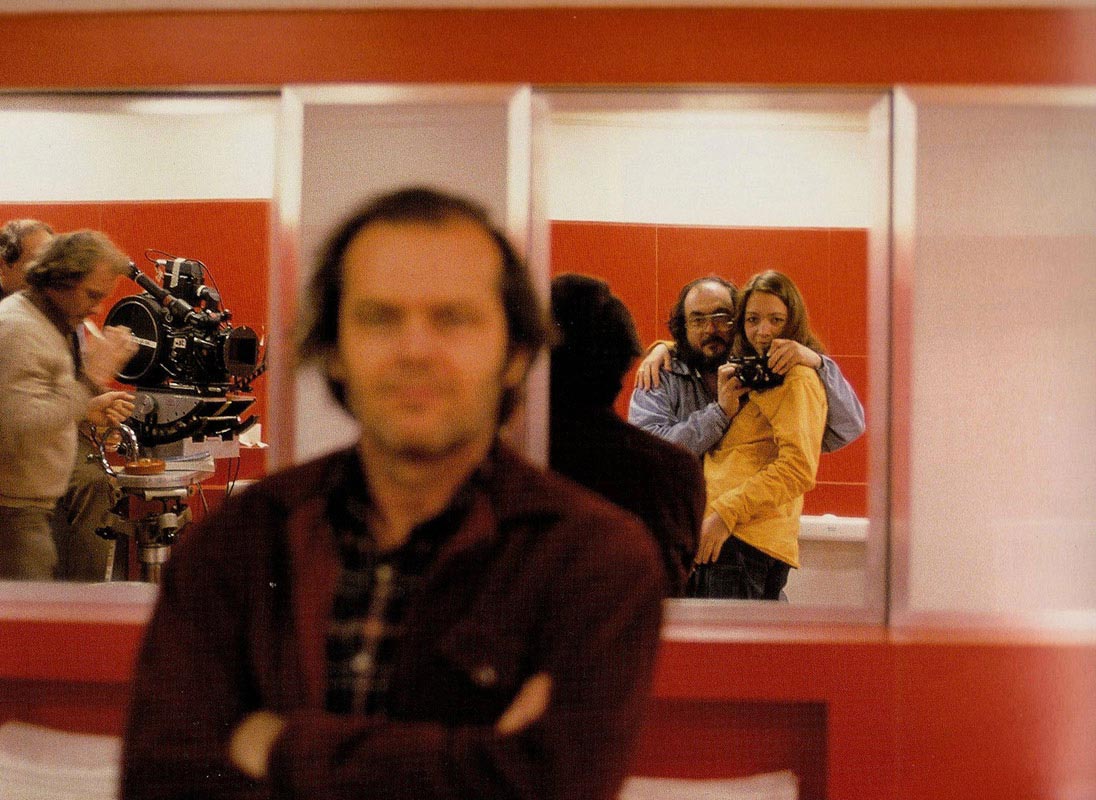

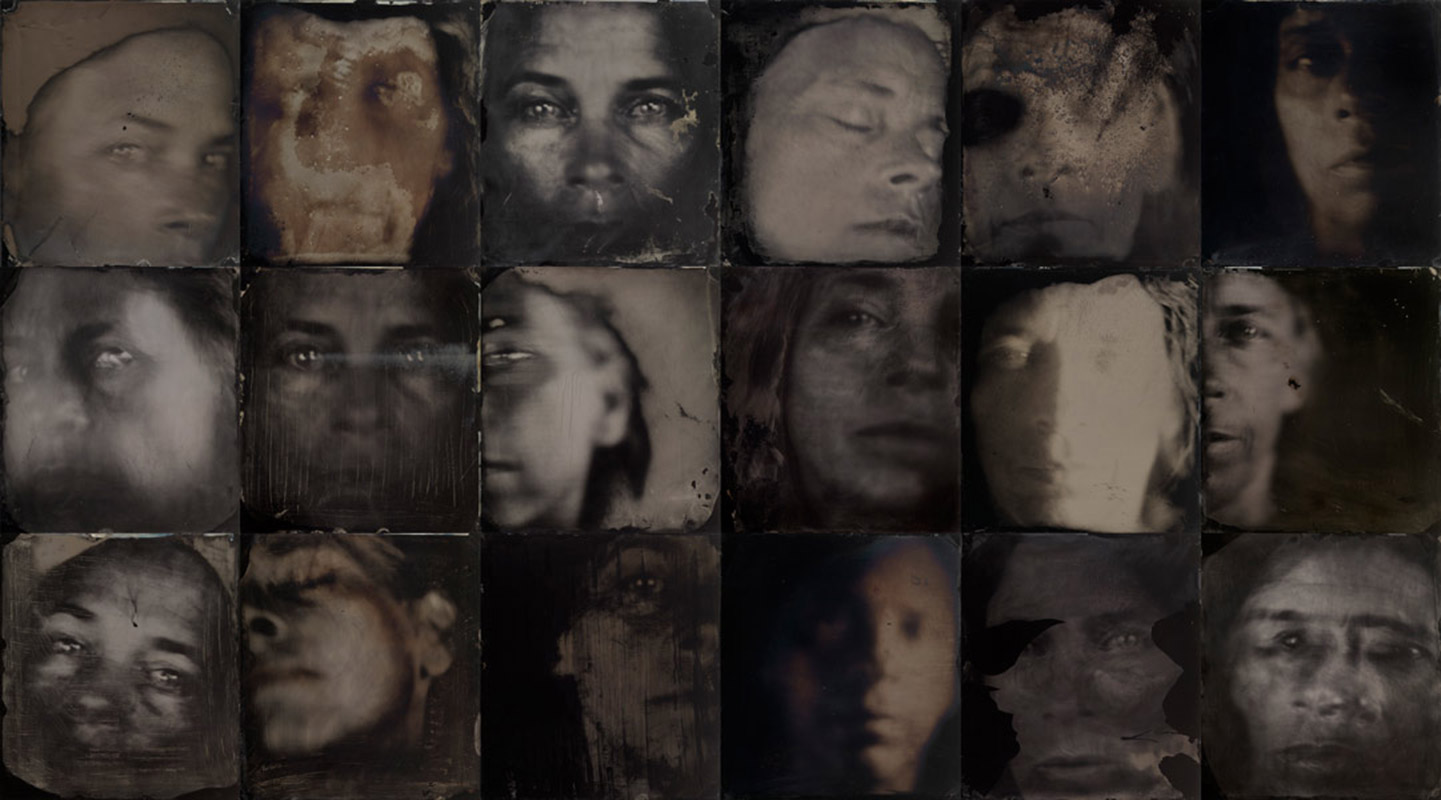

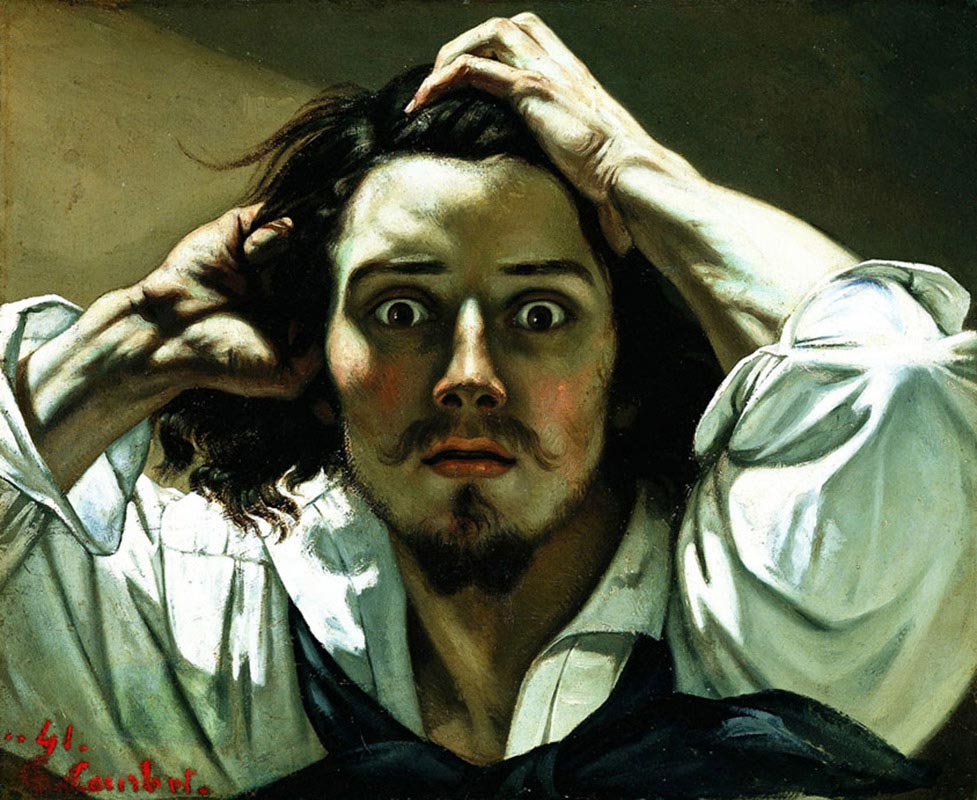

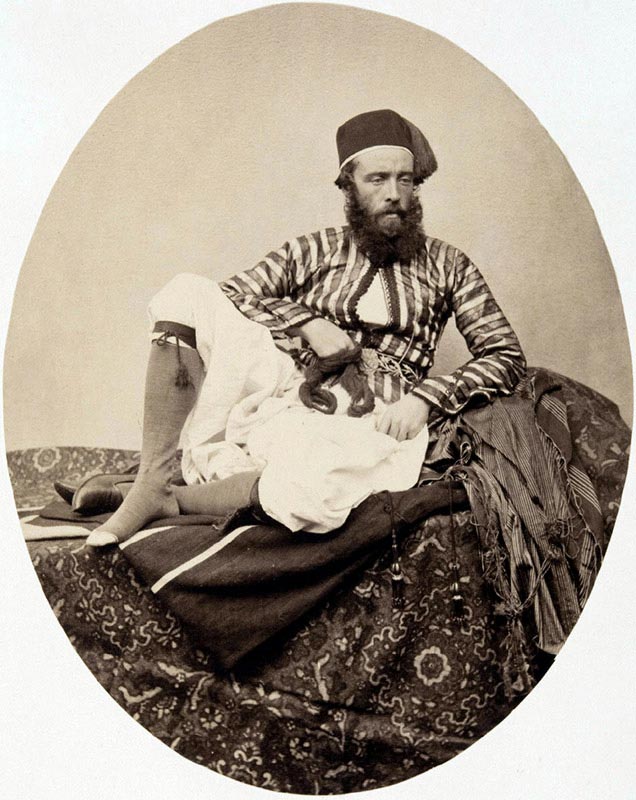

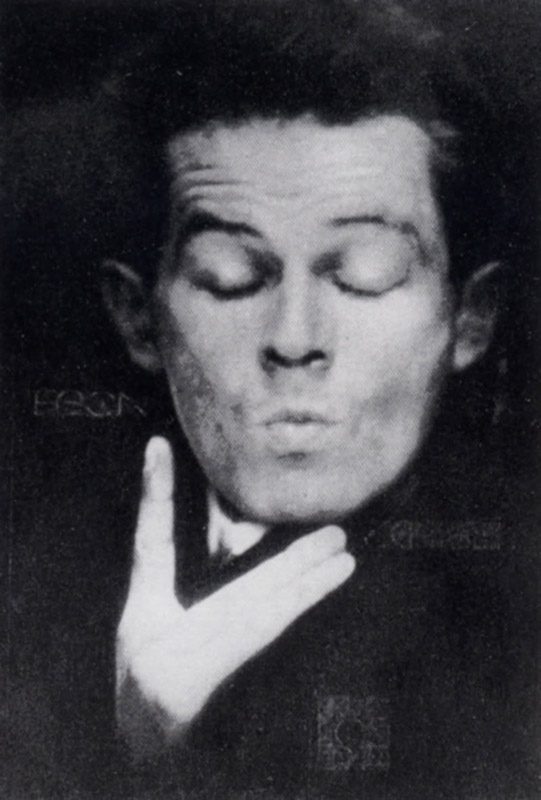

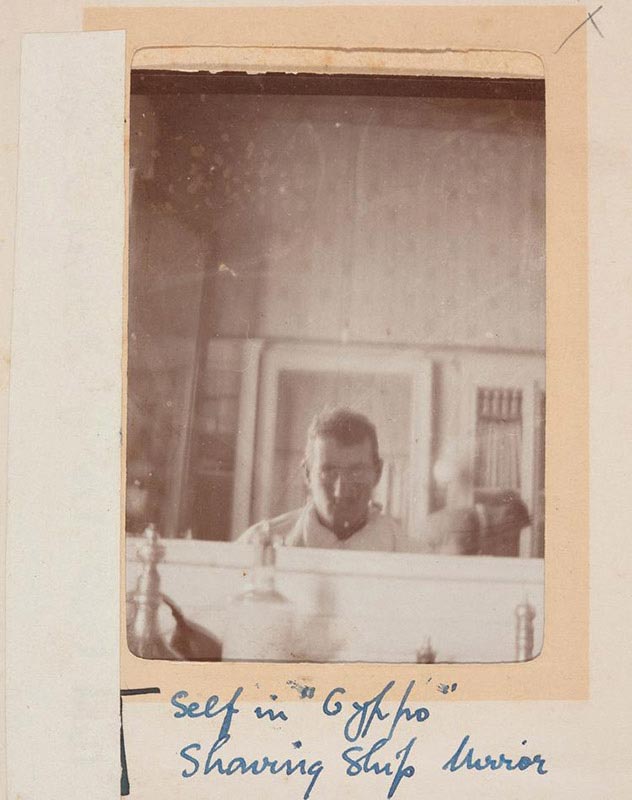

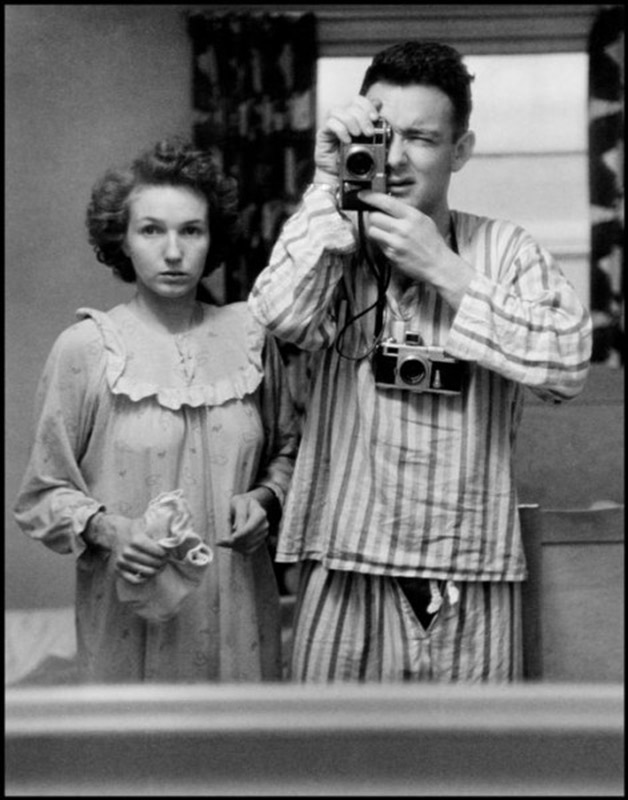

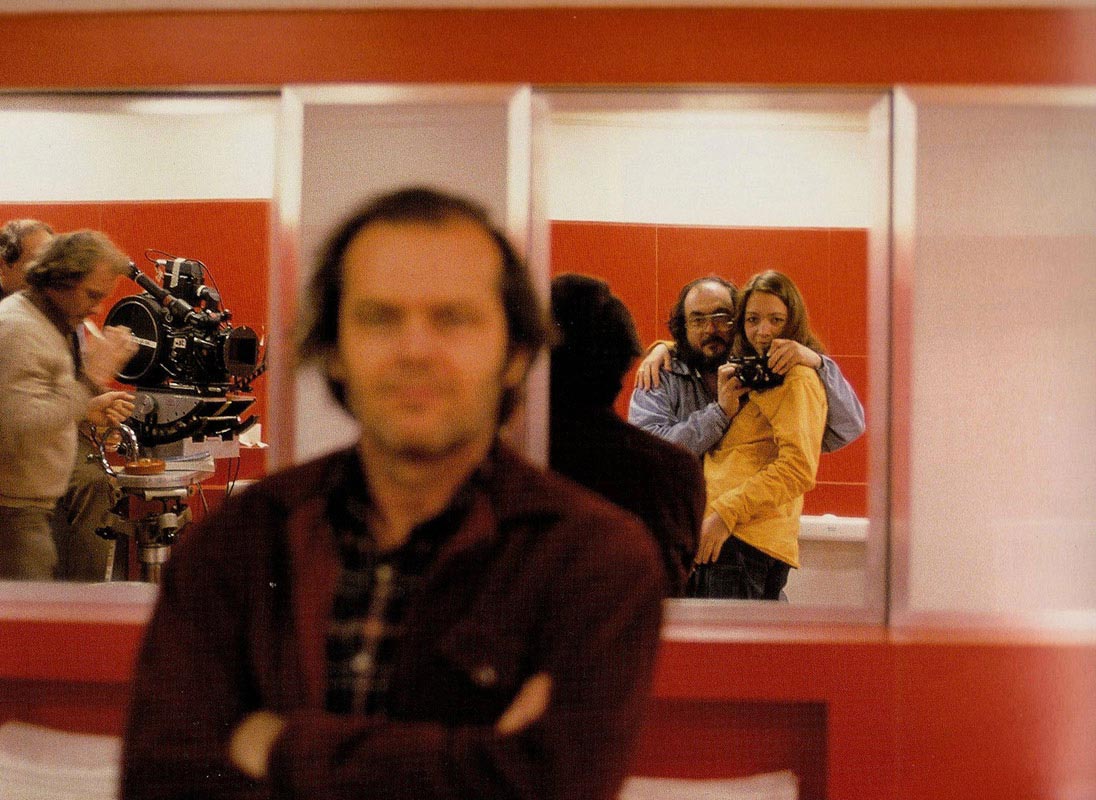

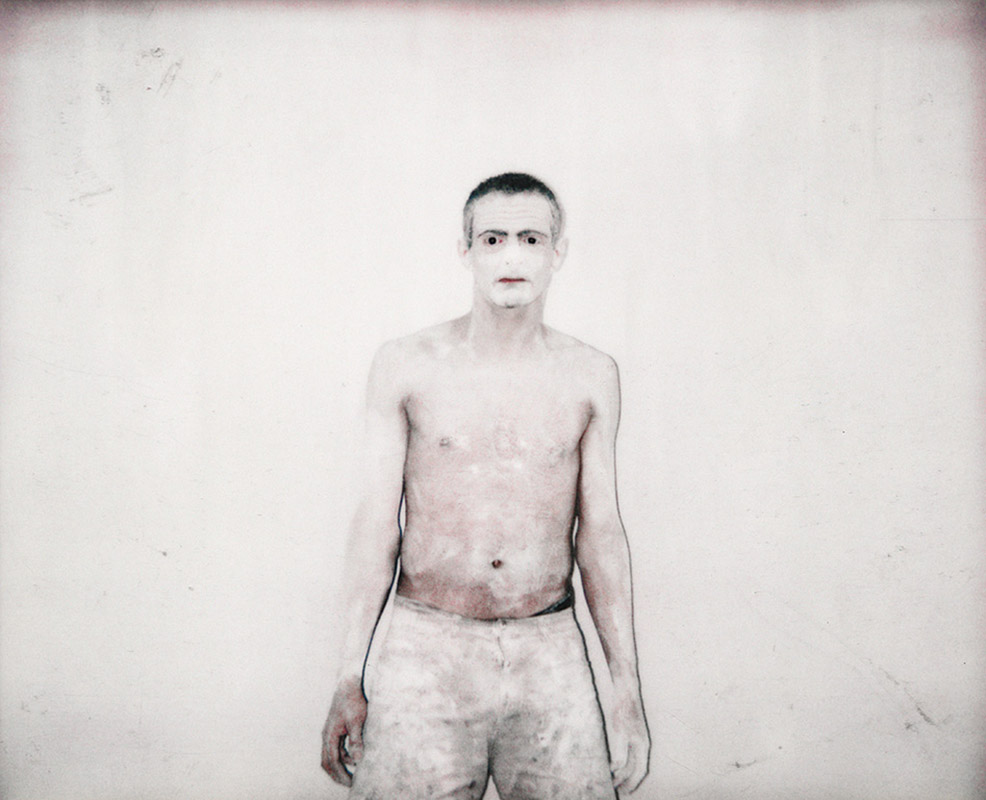

Through the various forms of artistic expression over the last 500 years, the natural relationship born between the creator and his work tool has offered a rough testimony of self-exploration. We can see it from the self-portraits of Renaissance painters to the self-explorations produced by photographers opposite a mirror. The difference is that today we live in, thorough and for the image, and the image has driven us to communicate in a new way. Today, it has become a right to possess images of one’s self, and in this context the selfie appears to have emerged as a logical derivation of this human action.

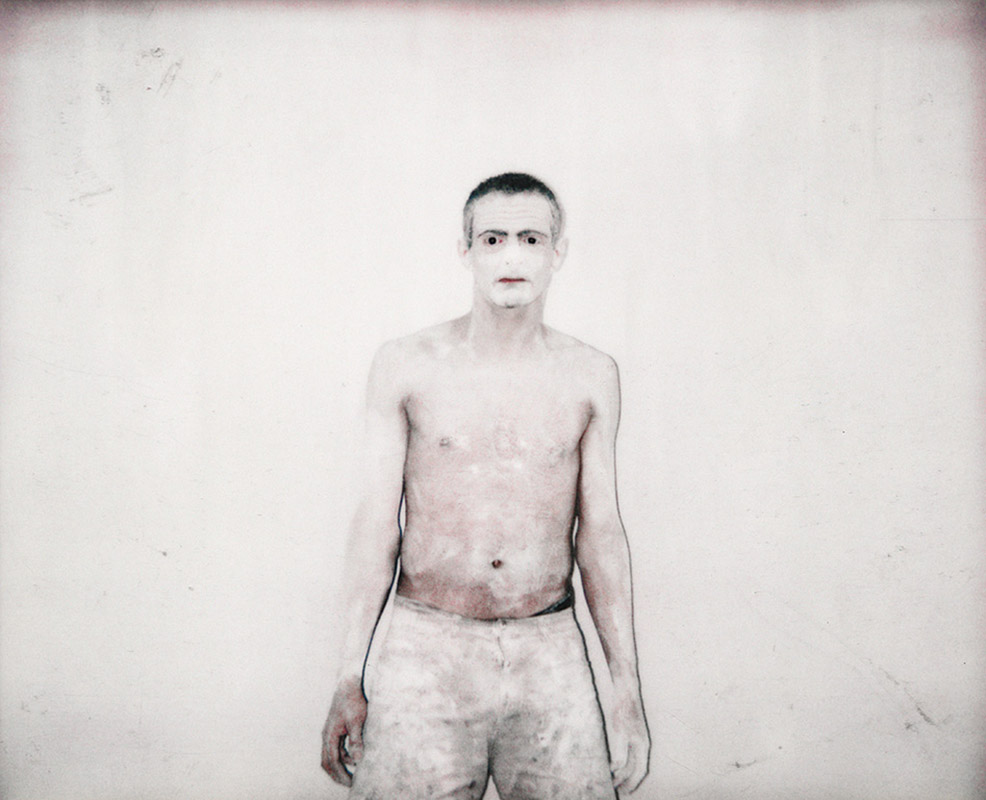

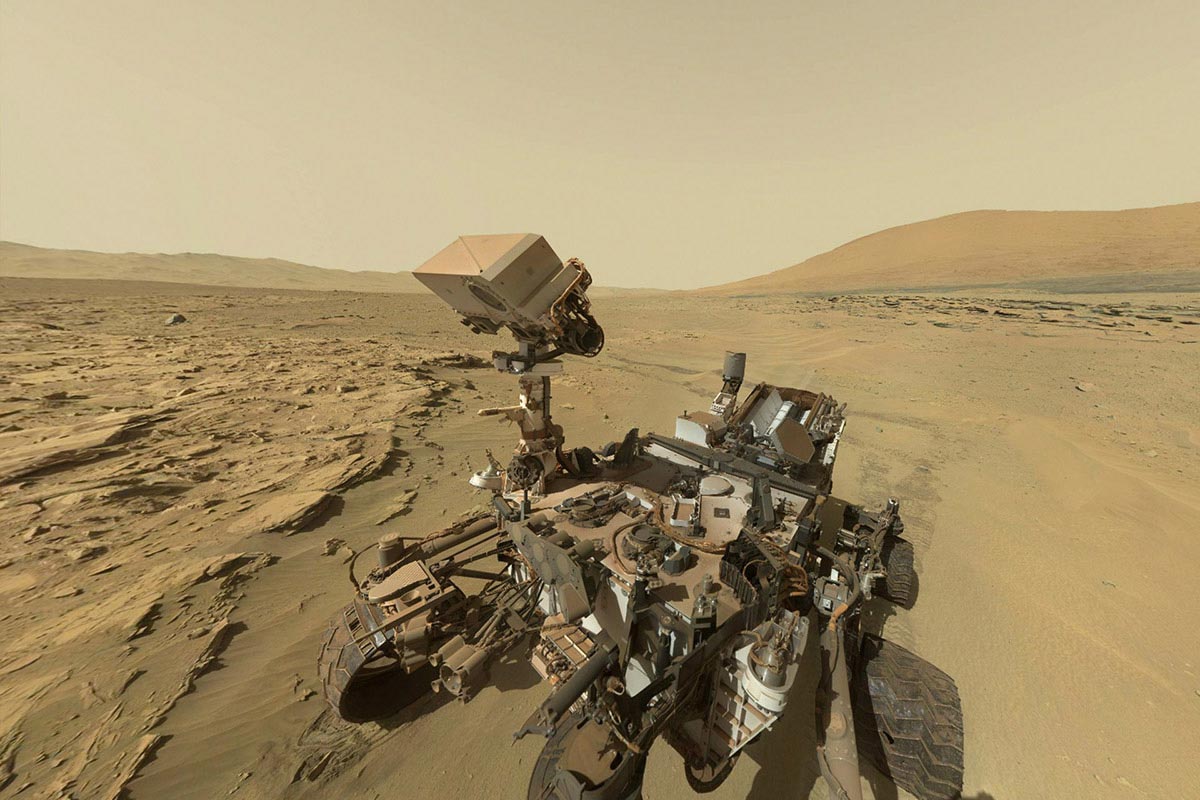

Could we therefore consider selfies within the tradition of the self-portrait? Do they serve to search for, or develop, one’s identity? Let us begin with the idea that a selfie is not only a self-portrait in the traditional sense of the word. The selfie is created using a smart phone or webcam and places us in a spontaneous context or situation, showing its relative lack of preparation, but it also contains metadata that are commented on and shared repeatedly. This could define it as an emerging sub-genre of the self-portrait1, as taking this photographic image is in line with the new platforms of audiovisual communication.

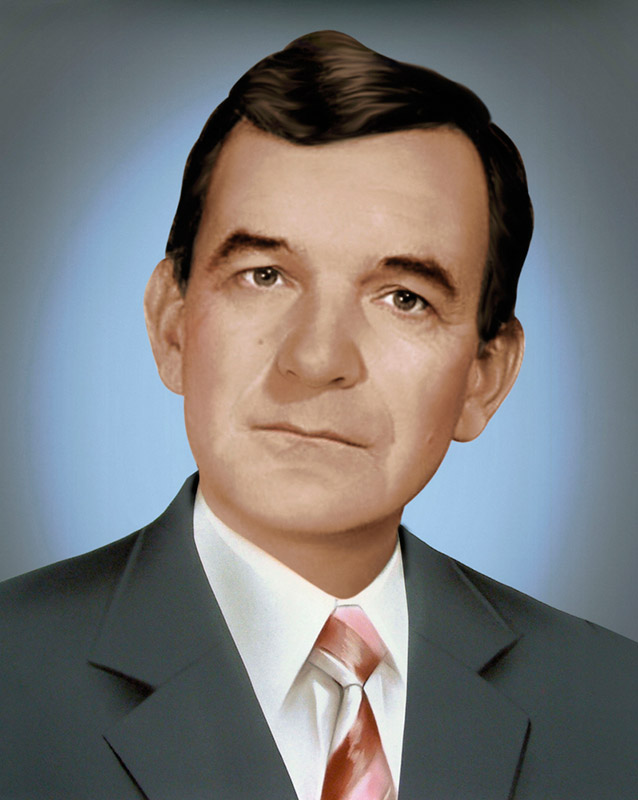

However, the most appealing facet of this “new” trend is its social value. Current-day self-portraits do not seek to say this is me or this is how I am, as was done in times gone by to construct an identity, but rather they follow the logic of here I am or this is where I am. Being somewhere at a given moment prevails over just being. Persons therefore show themselves in a location, saying: this is where and how I am right now, with a mood: this is how I am today, or even, when in company: here I am with so-and-so. “Photography is not a memory, but an act”.2

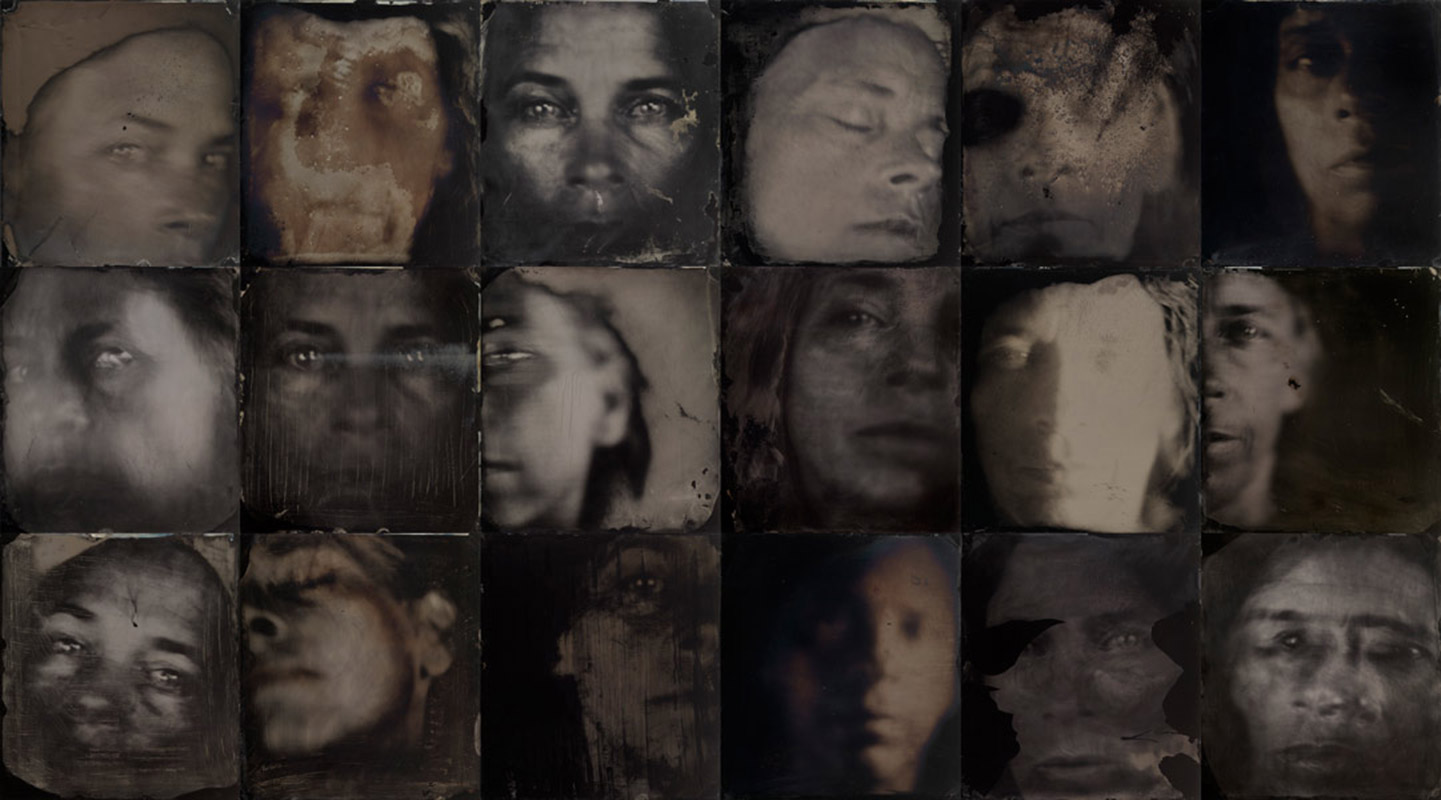

The numerous self-portraits published every day construct visual diaries that show us multiple, plural and at the same time communal “private” stories. They are, in the digital era, the result of the democratization of the image, and acquire meaning once they are shared, not only among a specific group of persons (friends and/or relatives), but among all those who construct meaning through their interactions. The more active the exchange in networks, the stronger the links between their participants.

There are currently pages specializing in selfies that gather images in similar situations (selfiesatfunerals, selfieswithhomelesspeople, selfiesatseriousplaces, museumselfies.tumblr.com), projects that bring together collections of the (app.thefacesoffacebook, A través del espejo by Joan Fontcuberta), studies (selfiecity.net), new trends (Shaky Selfie), competitions, festivals (ClaroEcuador, Olimpiadas del selfie) and every day new apps appear that encourage us to tell a story by capturing images (Frontback). On many occasions film stars, musicians and celebrities such as the Pope or presidents express themselves through this medium, creating an intimate proximity with the public.

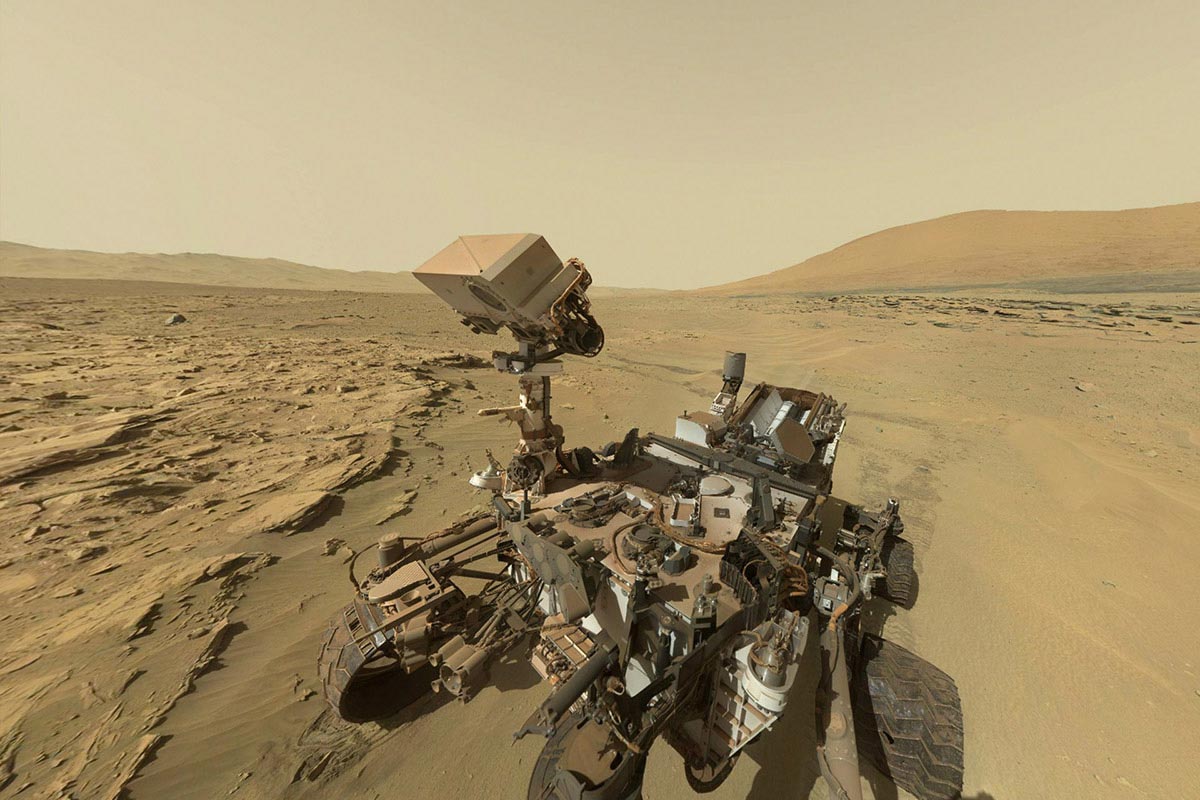

Taking photographs (of one’s self) has become an ordinary, everyday action. As Fontcuberta writes, it has become a compulsion. A vital compulsion in which each heartbeat becomes an image, such as the project The Whale Hunt, by Jonathan Harris, which uses 3,214 timed photographs to show in frequencies the most powerful moments of his experience of whale hunting. We are in an era that strives to photograph everything and create an interaction, in a context in which the photographic image has become a desire to speak. May nothing remain unrecorded or unshared! as we only exist insofar as we are present online.

What then of privacy? The intimate has become public. In 2000, a performance was presented called Nautilus, casa transparente.3 It consisted of a space with translucent walls in which a person was carrying out their daily life. People, some curious, others outraged, spend hours obsessively observing this person in his ordinary intimacy, as though he were an animal in a zoo. A few years later, and thanks to photography and its connectivity, we appear to be putting ourselves in this person’s place willingly and living in our own glass houses, exhibiting our everyday life without fear or prejudice.

Today’s democratized self-portrait is a public declaration carrying the message of our identity. The numerous devices and platforms used to communicate through the image enable us to react and create the need to leave a trace, in order for others to discover us. The selfie has become a social phenomenon of self-expression that can be as diverse as humanity itself, but we do not know to what extent social or cultural experiences are measured by the endless software. We are therefore invited to continue to take portraits of ourselves until technology becomes insufficient and we exceed the mobility, ubiquity and connection offered by the fifth moment of photography.4

1 Tifentale, Alise. The Selfie: Making sense of the “Masturbation of Self-Image” and the “Virtual Mini-Me”. February 2014 / selfiecity.net

2 Fontcuberta, Joan. Quote from Joan Fontcuberta: el post-talento fotográfico. February 2014 by Galcerán de Born

3 Nautilus, casa transparente, an original idea by the Chilean architect Arturo Torres

4 The fifth momento of photography explores the effect of the iphone on photography, the technological 'mash-up' with the internet and omnipresent social connectivity. Edgar Gómez, and Eric T. Meyer. Creation and Control in the Photographic Process: iPhones and the Emerging Fifth Moment of Photography. Photographies 5, number 2 (2012): 203-221.

Vanessa Alcaíno Pizani (Venezuela, 1980). Lives and works in Mexico. Visual artist. She graduated in Philosophy at the Central University of Venezuela and has a Master’s degree in Spanish and Latin American Thought at the Autonomous University of Madrid (UAM). Since 1994, she has worked in the field of photography at various institutions and organisations in Venezuela, Argentina and Mexico. At the moment, she is part of the editorial team of zonezero.com. You can see her work at: vanessapizani

Vanessa Alcaíno Pizani (Venezuela, 1980). Lives and works in Mexico. Visual artist. She graduated in Philosophy at the Central University of Venezuela and has a Master’s degree in Spanish and Latin American Thought at the Autonomous University of Madrid (UAM). Since 1994, she has worked in the field of photography at various institutions and organisations in Venezuela, Argentina and Mexico. At the moment, she is part of the editorial team of zonezero.com. You can see her work at: vanessapizani Elisa Rugo (Mexico, 1980). Lives and works in Mexico. She is a photographer, videographer and a specialist in visual communication with a degree in Creative Visualisation at the University of Communication. In 2012, she took part in the seminar Contemporary Photography at the Image Centre. She has participated in collective exhibitions in Pachuca, Querétaro, Guadalajara and Mexico-City. At the moment, she is the art director of the websites fpmeyer.com and museodemujeres.com and she is part of the editorial team of zonezero.com. You can see her work at: elisarugo.pro

Elisa Rugo (Mexico, 1980). Lives and works in Mexico. She is a photographer, videographer and a specialist in visual communication with a degree in Creative Visualisation at the University of Communication. In 2012, she took part in the seminar Contemporary Photography at the Image Centre. She has participated in collective exhibitions in Pachuca, Querétaro, Guadalajara and Mexico-City. At the moment, she is the art director of the websites fpmeyer.com and museodemujeres.com and she is part of the editorial team of zonezero.com. You can see her work at: elisarugo.proThat which I call my self-portrait is composed of thousands of days of work.

Each of them corresponds to the exact number and moment at which

I stopped as I painted after a task.

—Roman Opalka

Through the various forms of artistic expression over the last 500 years, the natural relationship born between the creator and his work tool has offered a rough testimony of self-exploration. We can see it from the self-portraits of Renaissance painters to the self-explorations produced by photographers opposite a mirror. The difference is that today we live in, thorough and for the image, and the image has driven us to communicate in a new way. Today, it has become a right to possess images of one’s self, and in this context the selfie appears to have emerged as a logical derivation of this human action.

Could we therefore consider selfies within the tradition of the self-portrait? Do they serve to search for, or develop, one’s identity? Let us begin with the idea that a selfie is not only a self-portrait in the traditional sense of the word. The selfie is created using a smart phone or webcam and places us in a spontaneous context or situation, showing its relative lack of preparation, but it also contains metadata that are commented on and shared repeatedly. This could define it as an emerging sub-genre of the self-portrait1, as taking this photographic image is in line with the new platforms of audiovisual communication.

However, the most appealing facet of this “new” trend is its social value. Current-day self-portraits do not seek to say this is me or this is how I am, as was done in times gone by to construct an identity, but rather they follow the logic of here I am or this is where I am. Being somewhere at a given moment prevails over just being. Persons therefore show themselves in a location, saying: this is where and how I am right now, with a mood: this is how I am today, or even, when in company: here I am with so-and-so. “Photography is not a memory, but an act”.2

The numerous self-portraits published every day construct visual diaries that show us multiple, plural and at the same time communal “private” stories. They are, in the digital era, the result of the democratization of the image, and acquire meaning once they are shared, not only among a specific group of persons (friends and/or relatives), but among all those who construct meaning through their interactions. The more active the exchange in networks, the stronger the links between their participants.

There are currently pages specializing in selfies that gather images in similar situations (selfiesatfunerals, selfieswithhomelesspeople, selfiesatseriousplaces, museumselfies.tumblr.com), projects that bring together collections of the (app.thefacesoffacebook, A través del espejo by Joan Fontcuberta), studies (selfiecity.net), new trends (Shaky Selfie), competitions, festivals (ClaroEcuador, Olimpiadas del selfie) and every day new apps appear that encourage us to tell a story by capturing images (Frontback). On many occasions film stars, musicians and celebrities such as the Pope or presidents express themselves through this medium, creating an intimate proximity with the public.

Taking photographs (of one’s self) has become an ordinary, everyday action. As Fontcuberta writes, it has become a compulsion. A vital compulsion in which each heartbeat becomes an image, such as the project The Whale Hunt, by Jonathan Harris, which uses 3,214 timed photographs to show in frequencies the most powerful moments of his experience of whale hunting. We are in an era that strives to photograph everything and create an interaction, in a context in which the photographic image has become a desire to speak. May nothing remain unrecorded or unshared! as we only exist insofar as we are present online.

What then of privacy? The intimate has become public. In 2000, a performance was presented called Nautilus, casa transparente.3 It consisted of a space with translucent walls in which a person was carrying out their daily life. People, some curious, others outraged, spend hours obsessively observing this person in his ordinary intimacy, as though he were an animal in a zoo. A few years later, and thanks to photography and its connectivity, we appear to be putting ourselves in this person’s place willingly and living in our own glass houses, exhibiting our everyday life without fear or prejudice.

Today’s democratized self-portrait is a public declaration carrying the message of our identity. The numerous devices and platforms used to communicate through the image enable us to react and create the need to leave a trace, in order for others to discover us. The selfie has become a social phenomenon of self-expression that can be as diverse as humanity itself, but we do not know to what extent social or cultural experiences are measured by the endless software. We are therefore invited to continue to take portraits of ourselves until technology becomes insufficient and we exceed the mobility, ubiquity and connection offered by the fifth moment of photography.4

1 Tifentale, Alise. The Selfie: Making sense of the “Masturbation of Self-Image” and the “Virtual Mini-Me”. February 2014 / selfiecity.net

2 Fontcuberta, Joan. Quote from Joan Fontcuberta: el post-talento fotográfico. February 2014 by Galcerán de Born

3 Nautilus, casa transparente, an original idea by the Chilean architect Arturo Torres

4 The fifth momento of photography explores the effect of the iphone on photography, the technological 'mash-up' with the internet and omnipresent social connectivity. Edgar Gómez, and Eric T. Meyer. Creation and Control in the Photographic Process: iPhones and the Emerging Fifth Moment of Photography. Photographies 5, number 2 (2012): 203-221.

Vanessa Alcaíno Pizani (Venezuela, 1980). Lives and works in Mexico. Visual artist. She graduated in Philosophy at the Central University of Venezuela and has a Master’s degree in Spanish and Latin American Thought at the Autonomous University of Madrid (UAM). Since 1994, she has worked in the field of photography at various institutions and organisations in Venezuela, Argentina and Mexico. At the moment, she is part of the editorial team of zonezero.com. You can see her work at: vanessapizani

Vanessa Alcaíno Pizani (Venezuela, 1980). Lives and works in Mexico. Visual artist. She graduated in Philosophy at the Central University of Venezuela and has a Master’s degree in Spanish and Latin American Thought at the Autonomous University of Madrid (UAM). Since 1994, she has worked in the field of photography at various institutions and organisations in Venezuela, Argentina and Mexico. At the moment, she is part of the editorial team of zonezero.com. You can see her work at: vanessapizani Elisa Rugo (Mexico, 1980). Lives and works in Mexico. She is a photographer, videographer and a specialist in visual communication with a degree in Creative Visualisation at the University of Communication. In 2012, she took part in the seminar Contemporary Photography at the Image Centre. She has participated in collective exhibitions in Pachuca, Querétaro, Guadalajara and Mexico-City. At the moment, she is the art director of the websites fpmeyer.com and museodemujeres.com and she is part of the editorial team of zonezero.com. You can see her work at: elisarugo.pro

Elisa Rugo (Mexico, 1980). Lives and works in Mexico. She is a photographer, videographer and a specialist in visual communication with a degree in Creative Visualisation at the University of Communication. In 2012, she took part in the seminar Contemporary Photography at the Image Centre. She has participated in collective exhibitions in Pachuca, Querétaro, Guadalajara and Mexico-City. At the moment, she is the art director of the websites fpmeyer.com and museodemujeres.com and she is part of the editorial team of zonezero.com. You can see her work at: elisarugo.pro