“China Power of Photography, 2006” by Vicki Goldberg |

part 1 | part 2 | part 3 | part 4

|

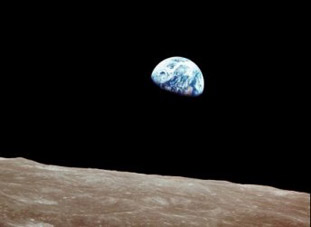

The Tet offensive began on January 30, 1968. Major American and allied military bases were attacked. So were South Vietnamese cities and towns, even Saigon, which was presumed safe, even the American embassy there. This picture and others were shown on television the next evening, and the day after that Adams's picture appeared on front pages across America and was reprinted and shown on TV across the world. Then two American networks showed film of this execution and distributed the film to foreign news organizations. The film on the American station ABC stopped the moment before the shooting and resumed with images of the dead man on the ground. The station inserted this photograph into the pause. |

February 1968 © Eddie Adams |

The Tet offensive was shocking to Americans, and many think it was the turning point in the country’s support of the war. The North Vietnamese and Vietcong attack came after months of an extensive public relations campaign by President Lyndon Johnson’s administration to convince the nation that we were finally winning the war. When the first bulletins on Tet came over the wire, Walter Cronkite, the most highly respected television anchor in America, exclaimed, “What the hell is going on? I thought we were winning the war.” Then came a gruesome image of a man having his brains blown out on the front page, an image that was horribly fascinating, that depicted a killing that went against all our democratic principles and laws, and that also told Americans in one small frame that our government had been lying about the war. The executioner, who was the highest ranking police officer in South Vietnam, killed his prisoner without a trial. The photograph, which quickly became a lasting symbol of everything that was wrong with the war, seemed to say that we were supporting a government that wasn’t worth fighting for.

One of President Johnson’s speech writers and confidants said later: “I watched the invasion of the American embassy compound, and the terrible sight of General Loan killing the Vietcong captive. You got a sense of the awfulness, the endlessness, of the war and, though it sounds naïve, the unethical quality of a war in which a prisoner is shot at point-blank range.” He was not alone. Anti-war demonstrations increased dramatically. Approval of the President fell fast and far, and two months after Tet he announced that he would not run again. This was not, of course, because of a single photograph, but that photograph came to symbolize the horrors and uselessness of the war and the lies of our leaders.

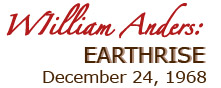

WHOLE EARTH, NASA

Even our views of our place in the universe have been affected by photographs. In the 1960s, some people were worried about the damage we were doing to the earth with pesticides and the threat of nuclear war, but little was being done about it. Then at Christmastime of 1968, three American astronauts on the Apollo 8 mission orbited the moon and sent back images of earth on live television that looked “like a sort of large misshapen basketball that kept bouncing around and sometimes off the screens back here.” After they returned to earth, NASA released still photographs they had taken, including one of earthrise taken on Christmas eve.

|

December,1968 © "Earthrise" William Anders |

William Anders, the astronaut who took this picture, said “Let me assure you that, rather than a massive giant, [the earth] should be thought of as [a] fragile Christmas-tree ball which we should handle with considerable care.” It was as if we had looked in a mirror for the first time and discovered that we were rare, beautiful, and dangerously vulnerable. This picture and others from space were published all over our newly small earth. It was stunning to think of our home as a minor planet adrift in a great void, and yet this photograph showed that the moon was dead and earth alive. Suddenly in America a mass ecological movement began among young people, and the first Earth Day was celebrated in 1970. |

An English scientist named James Lovelock finally had backing for his theory, which he called the Gaia hypothesis, that Earth itself was a living being, kept alive by the constant interactions of every part of the organism, from rocks to oceans to air. The recent emphasis on global warming stems from the realization of the interdependence of all parts and all events on the planet, a realization that was made vivid and inescapable by photographs from space.

Text abbreviated from:

The Power of Photography: How Photographs Changed Our Lives

by Vicki Golberg (Abbeville Press, 1993)

Photography today is at a very peculiar juncture. There are more photographs around, in more media, than ever before. In 1998, it was estimated that an American saw about 11,000 images a day, a number that surely has only increased. The internet is just one more place to see pictures of every sort, as well as one immensely more efficient way to distribute them. Obviously no one can take in that many images, much less remember them all. The overabundance of images is impossible to process, so people stop looking. They learn how to skim photographs as they know how to skim texts, and they know without being taught how to slide their eyes across a picture without really seeing it. It is harder than ever to make a memorable photograph that will make people stop and really look. So the question arises: can photographs still have real power? Yes they can. They do.