|

by Vicki Goldberg

Published under permission: Abbeville Press, Fine Arts & Illustrated Books

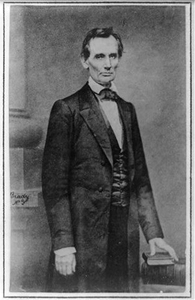

Photography was a powerhouse medium from the date of its birth in 1839 and was already on steroids and flexing its muscles when it was barely out of its teens. In 1860, Mathew Brady took a photograph that proved the medium had the power to affect events. His earliest portrait of Abraham Lincoln was the first photograph in history that influenced the election of a nation’s President, and it did so because of a change in the distribution of photographs.

|

|

|

Brady took this picture the day that Lincoln arrived in New York from his home in the middle of America to seek the Republican nomination for President. Almost no one in the east of America knew much about Lincoln or had seen a photograph of him, but he was rumored to be very ugly. He was uncommonly tall and awkward, and his dark skin was heavily lined. His opponents sang a song that ended, “Don’t, for God’s sake, show his picture.” A politician’s face was extremely important then, for Americans firmly believed that a man’s face revealed everything about his character. |

Brady pulled Lincoln’s collar up to make his neck look shorter, posed him to look serious, dignified and wise, and retouched the lines of his face. He gave Lincoln a good character and made him look presidential.

Later that day, Lincoln spoke at the Cooper Institute in New York. He was a charismatic speaker; a listener once said, “While I had thought Lincoln the homeliest man I ever saw, he was the handsomest man I ever listened to in a speech.” After the Cooper Institute speech, one reporter said he was the greatest man since St. Paul. Lincoln later said, “Brady and the Cooper Institute made me President.”

The photograph worked because it could be, in effect, mass reproduced and widely distributed. By 1860, photographic negatives had pushed aside the unreproducible daguerreotype, and the recently invented visiting card photograph was tiny and cheap. Everyone wanted to know what the greatest man since St. Paul looked like, and tens of thousands of Brady’s photograph were sold in inexpensive versions. Magazines printed engraved copies of it too, and a lithographic company, Currier and Ives, copied the image. They reversed it, cropped it, and colored the image -- a lot of changes, but lithographic copies of photographs were often what people saw, because small prints could be bought for as little as 20 cents.

CAMPAIGN BUTTON

The tintype came along at about the same time, and the Lincoln photograph was made into tintype buttons, the first campaign buttons ever to appear on men’s lapels – the predecessors of Mao buttons.

Because of Brady’s photograph, voters really knew what a candidate looked like for the first time. In effect, photography was creating celebrity. At the same time it created the emphasis on appearance that today makes a candidate who looks good on television have a better chance at winning than one who does not. Already in 1868, a magazine wrote that “The advantages which a handsome candidate…has over his competitors are … infinitely greater than they could have been before the invention of photography.”

----- Photography registers all kinds of appearance, and its potential for surveillance was established way back in the 19th century. Police photography began almost when photography did, in the 1840s, and surveillance really came into its own with the Franco-Prussian War in 1871. When the Prussians defeated France, the French government agreed to let them occupy Paris for 48 hours, but Parisians were so bitter about this that they rebelled and established the Commune, the first socialist government in history. The French government then laid siege to its own capital city. During the siege of Paris, the Communards, proud of their cause, posed for photographs.

|

Here is a group portrait of Communards, eager to have a memento of their rebellion. After the French government defeated them, the police commandeered any photographs they could find, distributed copies to railroad stations and ports to prevent escapes, and imprisoned and even executed men they identified from the pictures. Photographs were thus proved to be highly useful to the state for identification and control of its citizens. That such pictures may be imprecise was probably not conceded at the time by the authorities. Men can change their appearance many ways, most easily by growing beards and moustaches or shaving them off; it is quite possible that some people in the pictures managed to escape and that other, innocent men too closely resembled someone in the pictures and were unjustly condemned. |

"Comuneros" ©Braquehais |

The usefulness of surveillance depends on the accuracy of interpretation. When aerial photographs of ballistic missile installations in Cuba were taken in 1962 and threatened nuclear war, one American military advisor said they were really pictures of baseball fields. Back in the 19th century, people believed utterly in the truthfulness of photography and didn’t question interpretations. Now we believe photographs lie. And at one point, even the 19th century wasn’t so sure about that.