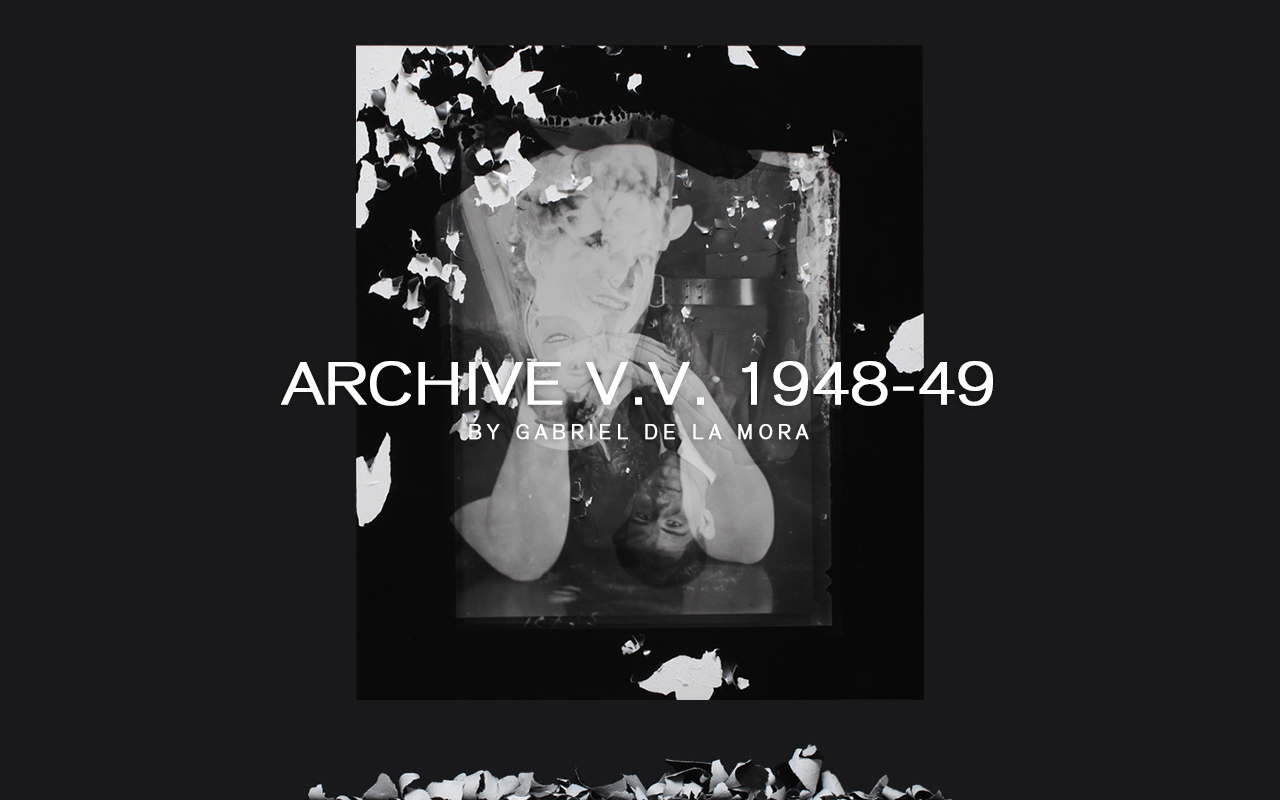

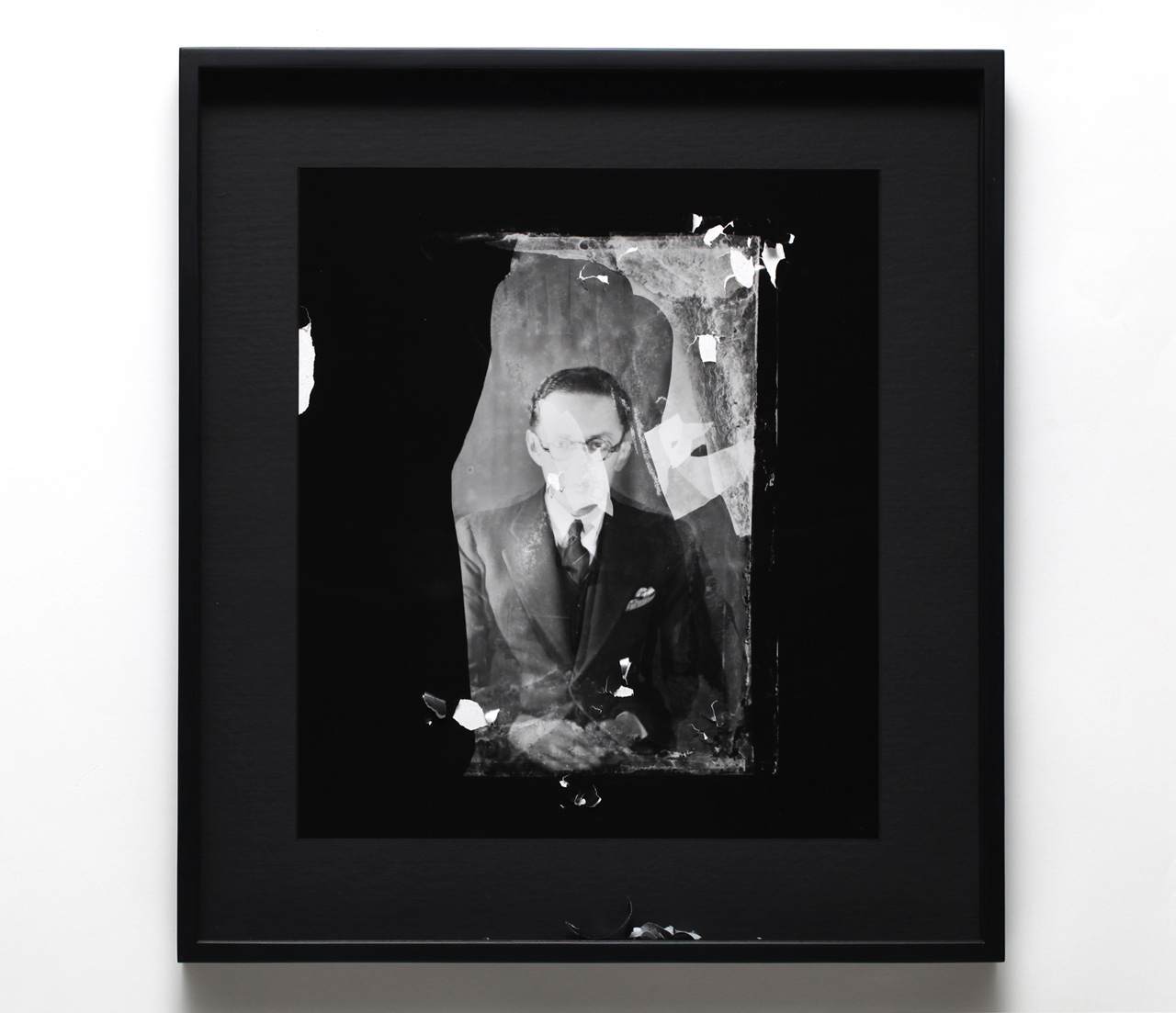

Archive V.V. 1948-49

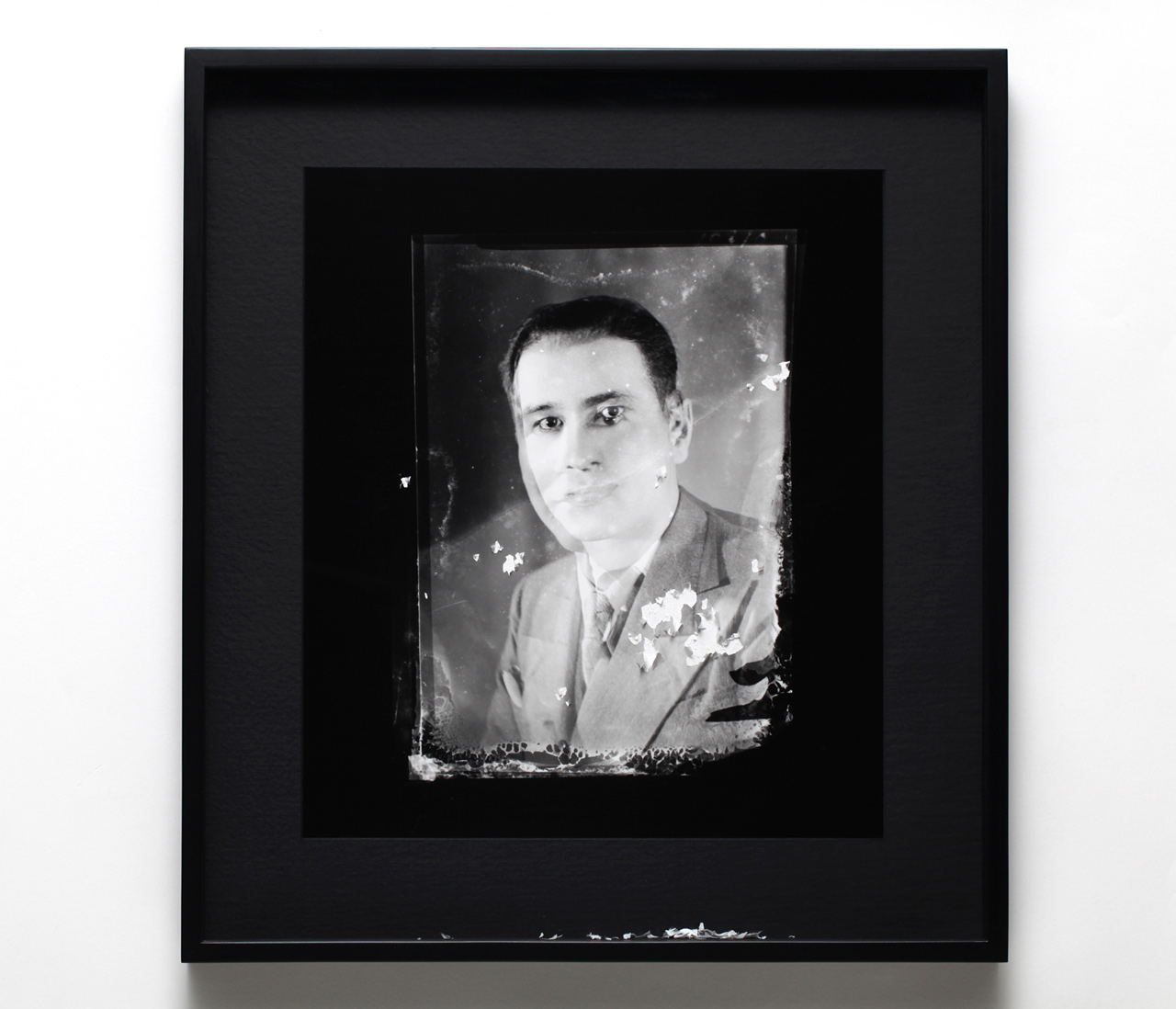

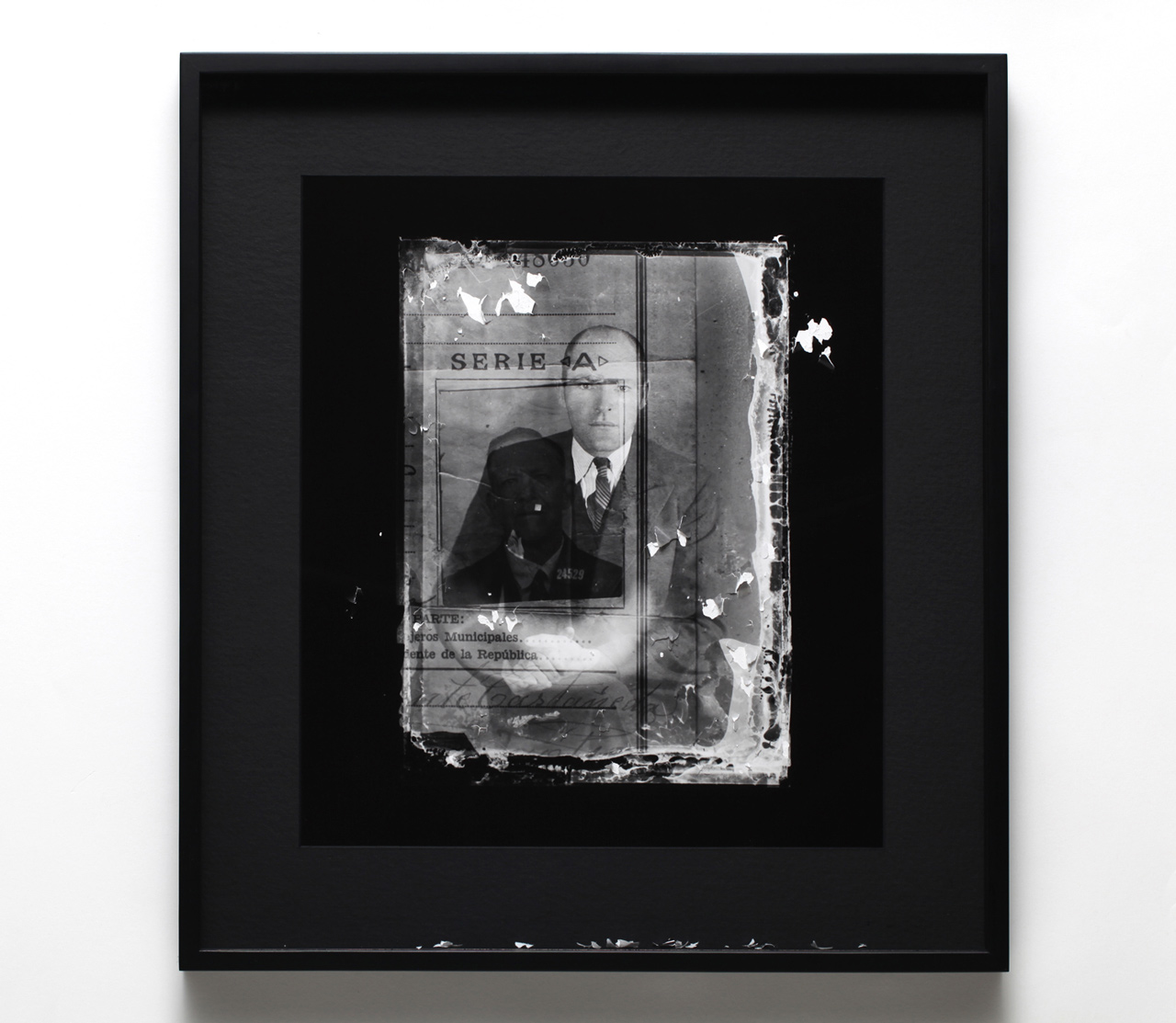

This series of altered photographs comes from a set of negatives that was destroyed when the warehouse where they had been stored for decades was flooded. This is why some of the negatives were stuck together, some of them showing two different takes of the same person and others two or three different people. They are negatives of portraits taken in 1948 and 1949 by Víctor Villamil Vilón at Cano Photography Studios, later called Vilón Photography Studios in Bogotá, Colombia. The images were printed on silver gel with fibrous paper in Mexico City and subsequently altered and framed. The artist begins his work by tearing off pieces of the photo.

Time and light do the rest, erasing the photographic image completely and leaving a monochrome surface. Only then is the work finished. Therefore 50, 100 or 300 years will have to pass, depending on the conditions in which the work is found. The artist never completes the piece and will surely never see it finished. This series is a parallel to the altered space entitled Pan-American Exhibition at NC ARTE.

Gabriel de la Mora (Mexico 1968). Studied a masters in painting, photography and video at the Pratt Institute in New York (2001-2003) and a bachelors in architecture at the Universidad Anáhuac del Norte (1987-1991) in Mexico City. He is currently a member of the Sistema Nacional de Creadores de Arte (2013-2015) and has received a number of awards and grants including the Primer Premio de la VII Bienal de Monterrey FEMSA, the Garcia Robles Fulbright Grant and the Jacques and Natasha Gelman Grant among others. His work as been shown in Mexico and abroad both individually and collectively.

Gabriel de la Mora (Mexico 1968). Studied a masters in painting, photography and video at the Pratt Institute in New York (2001-2003) and a bachelors in architecture at the Universidad Anáhuac del Norte (1987-1991) in Mexico City. He is currently a member of the Sistema Nacional de Creadores de Arte (2013-2015) and has received a number of awards and grants including the Primer Premio de la VII Bienal de Monterrey FEMSA, the Garcia Robles Fulbright Grant and the Jacques and Natasha Gelman Grant among others. His work as been shown in Mexico and abroad both individually and collectively.ZZ. In the project called Archive V.V. 1948 -49 how do you establish the photograph/time relationship? How does it affect the image both as an external and intrinsic element?

GM. Photographic technique is a constantly changing process. Depending upon the passage of time and light, on how the photo has been exposed to these two factors, it can slowly fade and begin to disappear. Which initially worried me for this project. But I think that later this inevitable factor became a starting point for various series in which I used photography as primary or supporting material.

In most of my work, photography is an important element, whether as a file or a document, or a starting point as it was for Willy Kautz in his work shown at the Amparo Museum from October 2014 to February 2015 under the title "What watches us that we don’t see.” The starting point in this exhibit was how an image becomes monochromatic and how a monochrome can become an image.

Although I take photographs to document pieces and processes, amongst many other things, I like to work with vintage photographs from the late 19th to the late 20th century. I buy archives, classify them and then begin my explorations. For the Archive V.V. 1948-49 project I used destroyed negatives for the first time. The alterations were both accidental and due to the passage of time, which produced astounding results.

The Vilón Archive series began in 2012 while I was preparing for my first altered space project at the NC ARTE gallery in Bogotá Colombia. As an alternative activity to the show called Pan-American Exhibition curated by Willy Kautz, I visited an old photography studio near the NC ARTE gallery. I was hoping to find vintage portraits taken in Bogotá in 1948-1949.

Victor Vilón’s children, Germán and Patricia Vilón, who owned the Vilón Photography Studio, told me that although they had no old photographs they did have some negatives which they would look for to show me. Two days later I turned up punctually for our appointment and both Patricia and Germán had a look of utter frustration: they showed me a cardboard box containing hundreds of negatives that had been destroyed by a flood in the warehouse where they had been stored, which no-one had noticed. Patricia showed me various negatives that were stuck together and would break when separated and told me they were going to throw it all away. When I saw some of the negatives, I found them far more interesting than they would have been if they had not got wet. So I asked Germán if they could print the negatives in their destroyed state and he told me that they could, but that they would turn out badly. I chose a few and asked for examples. A couple of days later, these examples exceeded my expectations. Previously, I would buy vintage photographs from Mexican movies and alter them by randomly tearing part of the film to transform the narrative and configuration through a process of abstraction and destruction.

Before destroying each image I would scan both sides so that each altered photograph could be added to my digital archives.

The destroyed negatives from Archive V.V. had not been altered by me, but by an accident that destroyed them over time, so the artistic process for series like the one on Mexican movies was carried out by time rather than by me. The result is simply amazing. To rescue the negatives from the garbage I asked German and Patricia to sell them to me to keep in Mexico where I could continue experimenting with the series of images.

ZZ. How much do you intervene in the construction of a photographic image and at what point is it beyond your control?

GM. As an artist I like to have control over certain pieces or series, but I also like to lose absolute control over other series in particular, or occasionally combine both: control and randomness.

With regards to the destroyed negatives, or Archive V.V. 1948-49, the majority of alterations were made by the flood and time and the results were the starting point for a new series. When printed, the images were extraordinary, unique, and I did not intervene in them at all except for finding and recovering them. It was like a type of assisted Ready Made, as Francisco Reyes Palma so aptly called it. Once the photos had been printed, I altered them again by tearing part of the photographic film off and leaving the fragments at the bottom of the frame. This begins a process that, depending on the conditions in which the photo is stored, time and light, will cause the image to entirely disappear in maybe 50, 100 or more years, transforming the photo into a monochrome white surface. When this finally happens, the piece will be completed. “The artist only begins the piece, but will never see it finished as its process continues over time even after the artist’s death.”

Back in Mexico, I went to a photography laboratory to print the negatives I had chosen on fiber paper in a similar way. Once they were printed, but before framing them, I altered them randomly, tearing bits of photographic film off and saving them so that after the photo had been framed, they would be at the bottom of the frame.

What most interests me is what happens after the first intervention when the destroyed negative is printed. I intervene again by tearing off small pieces of the image, thereby beginning my piece of work, since time, light and varied storage conditions will complete the piece.

ZZ. When the object mediates between the artist and the spectator, what type of reflection does it incite?

GM. At the end of the day, everything vanishes. Nothing is eternal and everything is subject to constant change and transformation. Art is neither created nor destroyed, only transformed.

In my work, I like to introduce the works. They do everything. There is a an interesting visual, formal and technical factor that makes an initial, perhaps more emotional impact. Afterwards, you can explore what goes on behind the process, and the work itself has various levels of information where one question leads to another, and so on, indefinitely.

When something attracts your attention and you like it but it also makes you think, for me, that is the point where the work becomes whole. Each person will have a different opinion or reaction depending on the level and type of previous information they possess. The images or works in this series, for example, have received differing opinions and reflections. In some people they elicit nostalgia for an era, a person who no longer exists or who died years ago; for others, it produces a certain mystery, or even fear, since some of the faces or images are rather ghostlike.

Personally, I believe that the images are powerful in every respect. They have an extraordinary composition and were, in a way, part of an archive which, when it was destroyed, fulfilled its destiny by becoming waste. This is a footnote for me as an artist, knowing that what comes at the end of one thing can be the beginning of another. This waste or residual material can be transformed into artwork.

When two or more negatives in the archive are stuck together and then break and are fragmented into other images, the way I print them turns them into something extraordinary. They have been altered by time, through a naturally destructive process, making the image into an abstraction with a strange composition. The people still exist in them, or their presence is registered, together with a whole era. Thus the images are historic documents that are transformed into something else.

The original author of these portraits was Don Victor Villamil Vilón, and now I am the author. I love to find new ways of experimenting with photography. I did not originally take these photographs, but I did rescue them from the becoming garbage after they had been destroyed in a flood and now they are prime examples for exploring image through records, archives and documents.