Max de Esteban

ZZ. What led you to appropriation and remix and how are they significant in your work?

M. Appropriation and remix have a long artistic tradition, beginning with Picasso’s collages. As early as the 1920s, Hannah Hoch and the Dadaists used this mode of expression to create major photographic works. In music, for example, from today’s DJs and Pop to Glenn Gould and Miles Davis, the practice of remix, collage and appropriation has been an essential part of their production. What I mean is that as an artistic concept, appropriation and remix are pretty standard and not particularly groundbreaking.

The interesting question is why their aesthetic power has been reasserted in photography precisely now. And I think one possible answer would be the combination of the formal exhaustion of the linear perspective as a photographic representation of the world and the huge impact digitization is having on every aspect of our lives. I would answer your question by turning it around and saying I find it hard to think of a truly relevant form of photography for the world we live in that continues to respect the Eurocentric, reactionary structure of the dark room.

ZZ. What do you mean by Eurocentric and reactionary?

M. The linear perspective, the visual structure resulting from the dark room, is a very particular and ideological way of visualizing the world. Panofsky has a text about it he wrote in 1927, a real classic, that is a pleasure to read.

But what is really remarkable is that it is an exception in art history. In 10,000 years of history, the linear perspective spans only 500 years and is located exclusively in the West. It has never been of interest to Asian, or pre-Columbian or African art ... it is a European way of seeing in a period beginning in the Renaissance and ending in the 19th century.

And this is no coincidence because its ideological content is well known. The linear perspective arranges the world from the point of view of an autonomous individual whose individuality is the world’s principle of meaning. It is pure Descartes. And we all remember Descartes’ Fifth Meditation, which states that since the essence of matter is its extension, geometry is an essential instrument for understanding nature. Modernity can be defined as the advance of abstraction and the prevalence of the quantitative over the qualitative in which the mathematical-scientific order is regarded as the only source of valid knowledge. There is so much contemporary thought that debunks this narrative that I won't repeat it here.

Thus, surprisingly, my earlier comment is still valid. Why should digital photography continue giving priority to a functionally and ideologically devalued visual structure?

ZZ. Why do you think digital photography changes the way we understand appropriation and remix?

M. Digital technologies are leading us towards the radical transformation of our world. By replacing the industrial economy with a bio-cybernetic system, digitization is modifying our environment, our subjectivity and soon, our bodies. This is the technological phenomenon that will define our era and therefore our culture.

Unlike an analog file, a digital file is invisible. It is a code whose visual expression is a translation highly mediated by default algorithms, whose most prominent feature is precisely its immateriality.

This technical structure fits our current era of abstraction and non-referentiality and the digital financialization of the economy. How do we see the world today? We have the answer on our computer and Smartphone screens. What is the essential aspect of the financial economy? The recombination of existing information units to create new information, in other words, “constructive compositing”. Digitization has definitively invalidated linear narrative, the monocular perspective and the author’s “authority”.

ZZ. You attach a great deal of importance to the concept of technology in your work. Could you explain why?

M. We are moving towards a world as a “technological whole”. Technical manipulation has already invaded our bodies, the last frontier, and no-one doubts that having machines inside our bodies will soon become commonplace.

The cyborg raises more complex issues for our species, which, though somewhat deteriorated, continues to maintain the autonomy of the subject as an essential value. Abstraction, digitization and cyborg are three sides of the same coin that heralds our new world, whether we like it or not. In my opinion, reflecting on technology is necessary, urgent and politically essential.

ZZ. And how do you think technology affects the practice of photography?

M. I’d like to point something out. One of the problems of photography is the confusion between technology and use. Writing is a communication technology that serve to draw up a commercial contract and compose a poem by Virgil. It is the same technology but nobody would ever mistake Virgil for a notary. In photography, we tend to combine uses, which creates enormous confusion in critical discourse. Throughout this interview, I have been referring to the use of photography as a means of artistic expression.

The thing is that photography has always been halfway to a cyborg. It is a machine that affects and to some extent determines human power, thought and expression and is therefore an ideal place for reflecting on the issues I mentioned earlier.

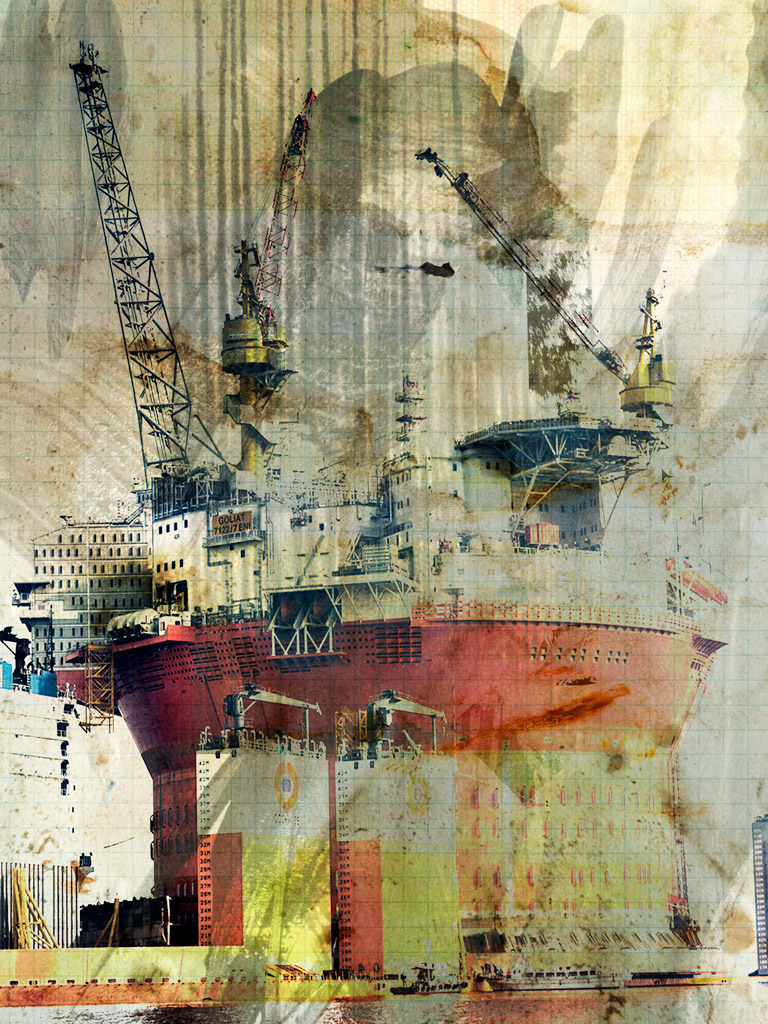

To give you an example: How can you visually depict the abstraction of the economy when the material references of wealth have been replaced by a binary code? That’s what I’m doing at the moment and it forces me to rethink what “representation” means in this new visual regime.

Another example: How does the idea of the cyborg affect art categories? That’s the topic I try to get my teeth into in the text “Cyborg Art: art in the bio-cybernetic era”. And there are a thousand other possible ideas that make photography an exciting medium at this particular historical time. The point is that if photographic practice does not take up the challenge raised by contemporaneity, it will be relegated to banality and antique shops.

ZZ. How do you choose the sources you use and what significance do they have for your series?

M. Like nearly everything in life, it is a combination of determination and chance. In my case, too much planning and/or reflection in my work paralyzes me while dreams or rather daydreams are of paramount importance.

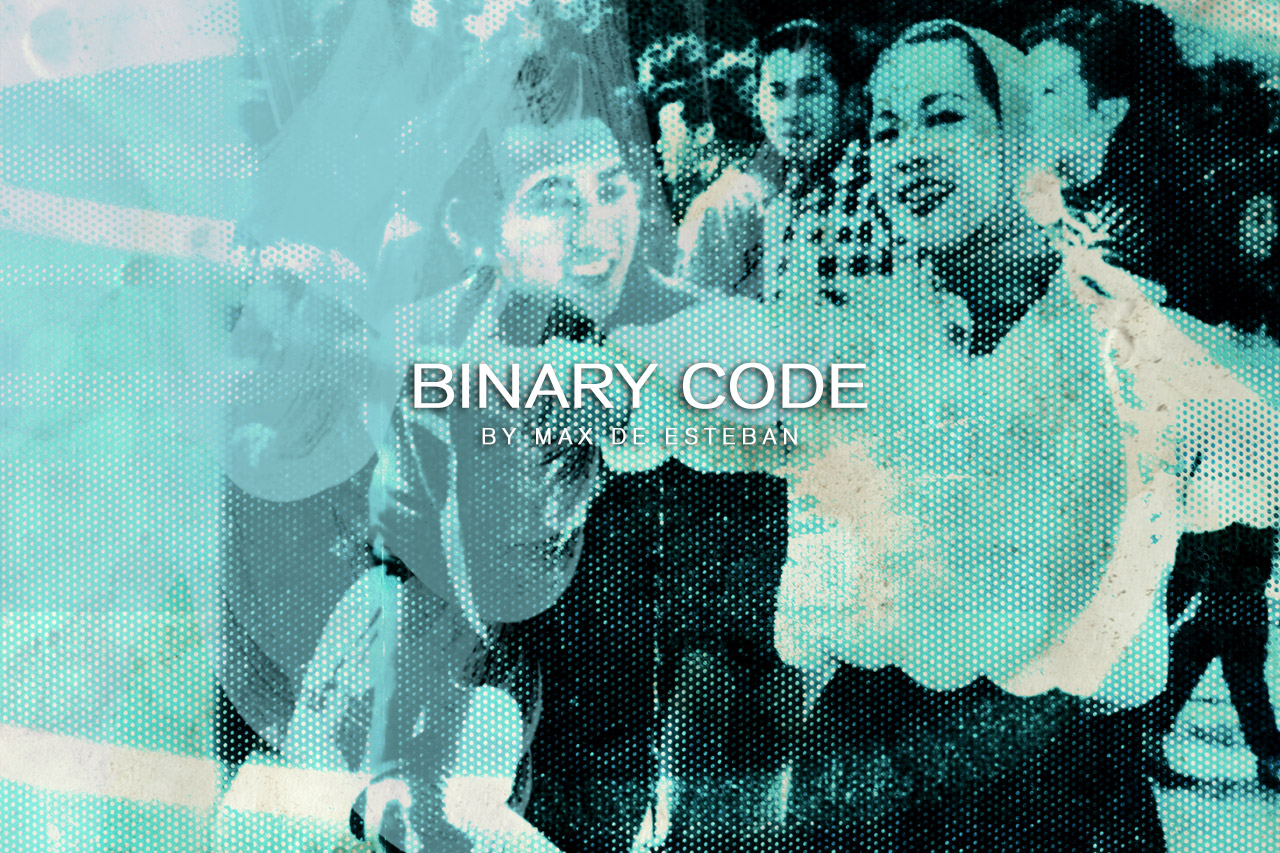

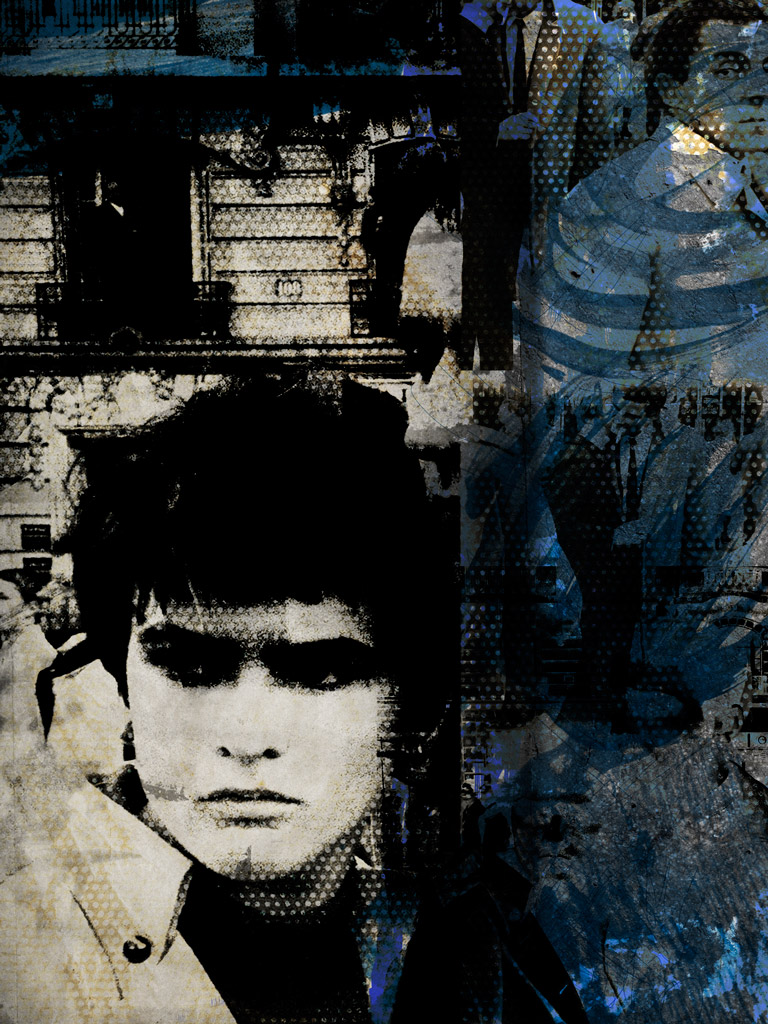

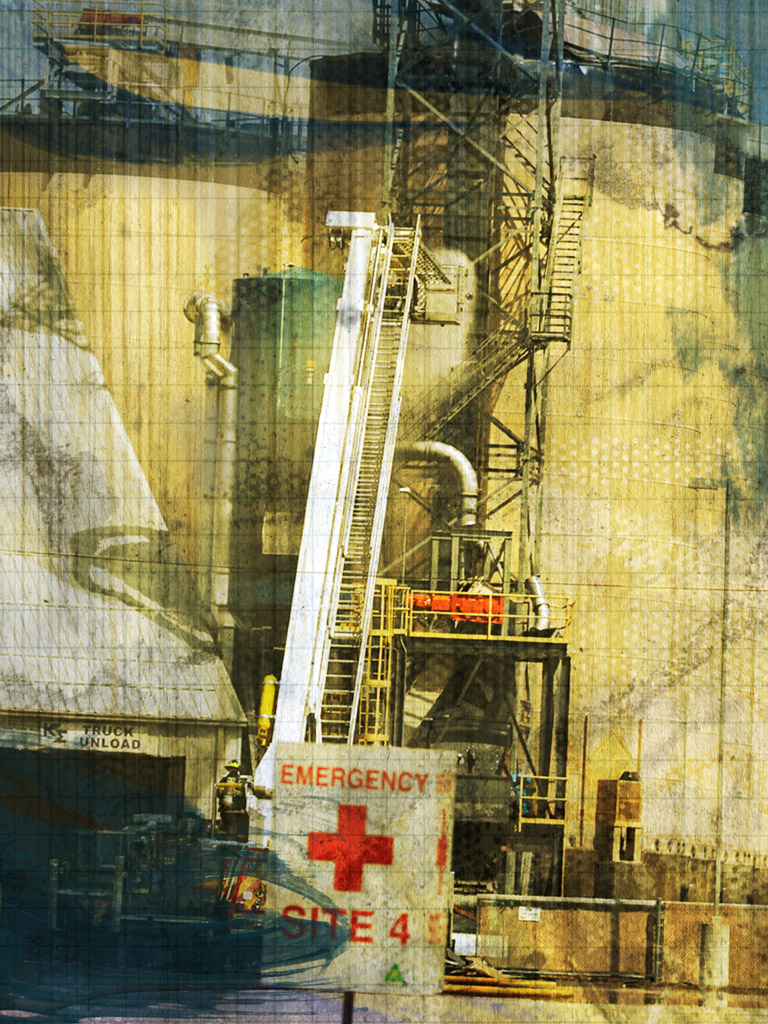

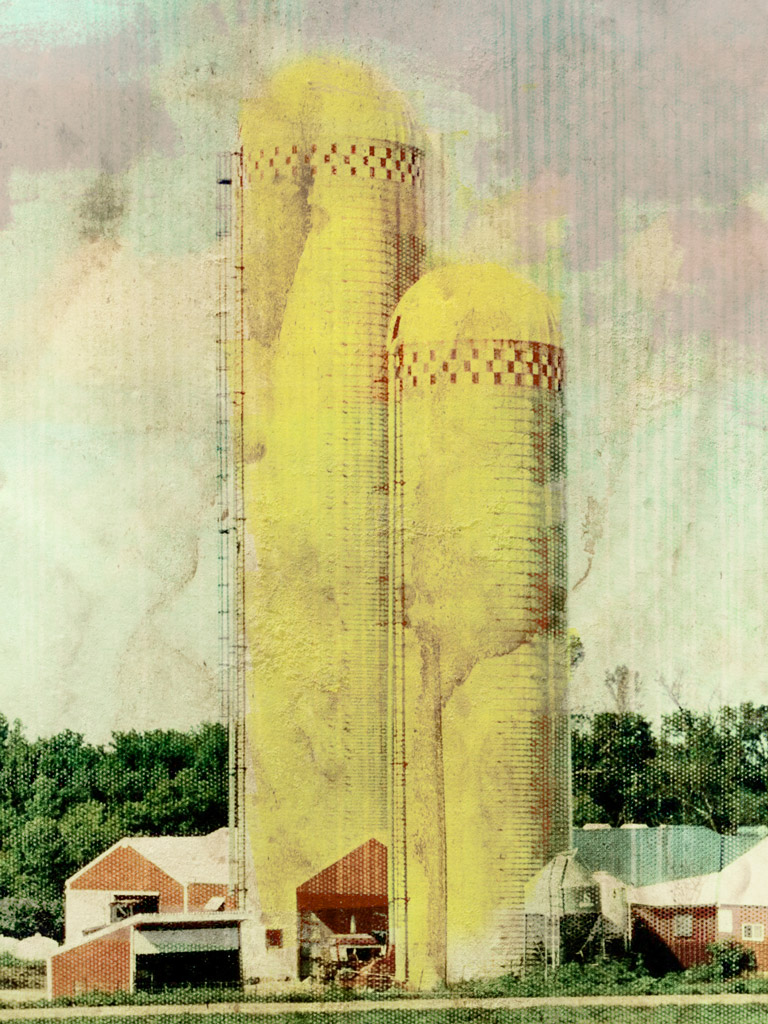

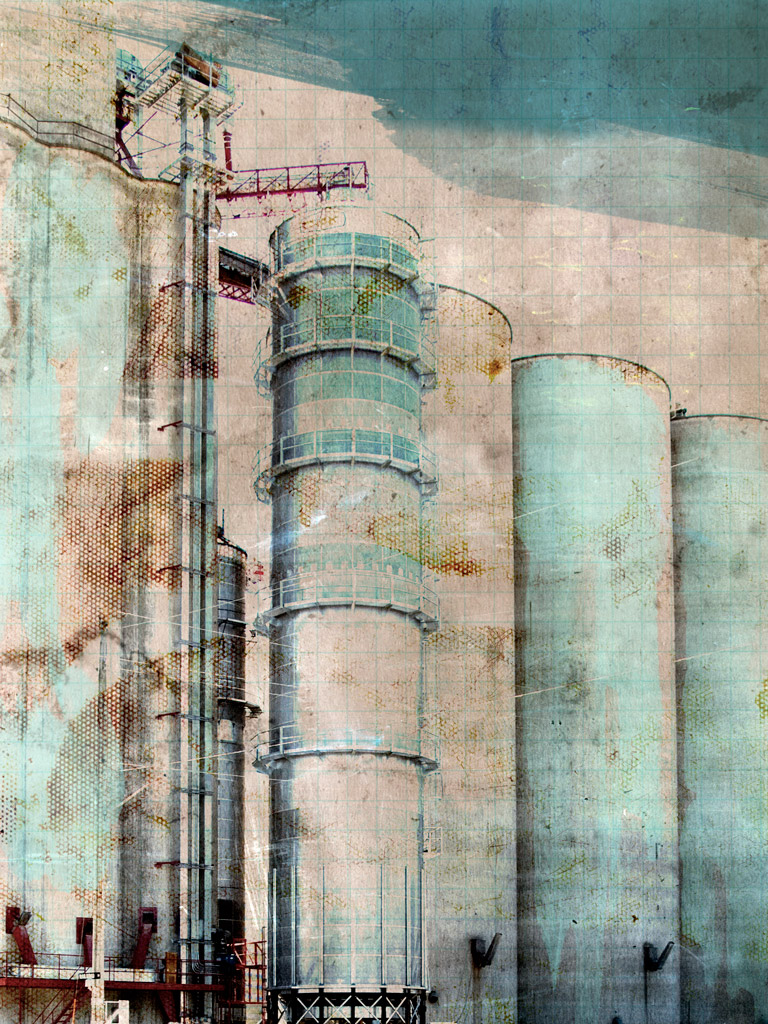

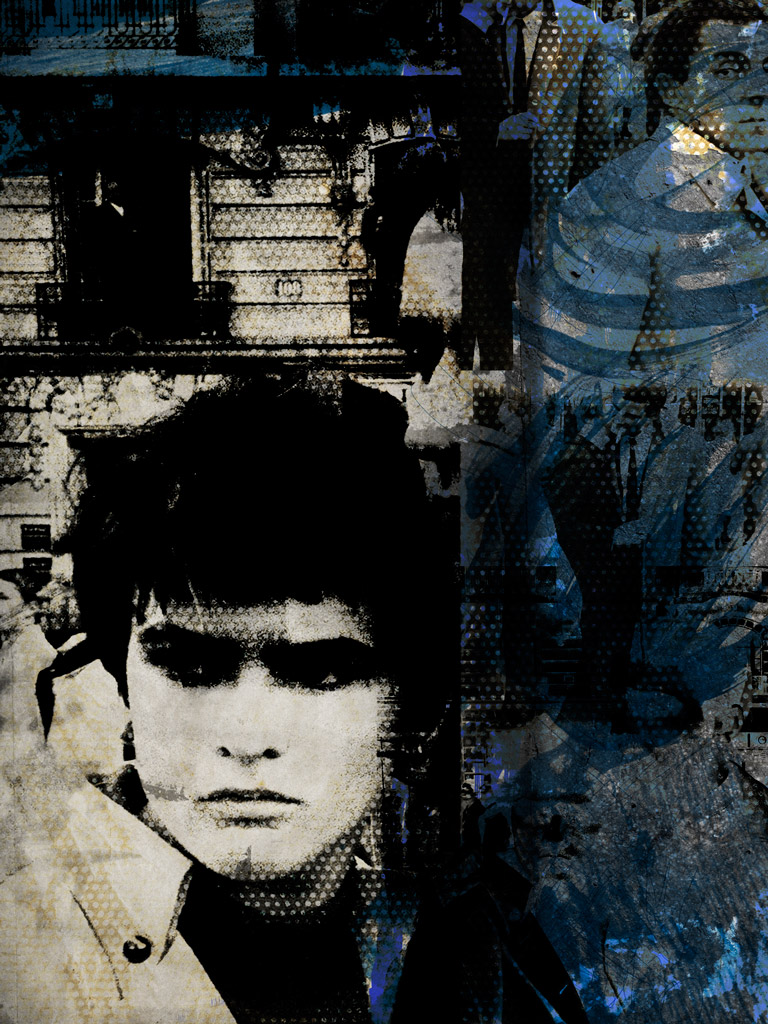

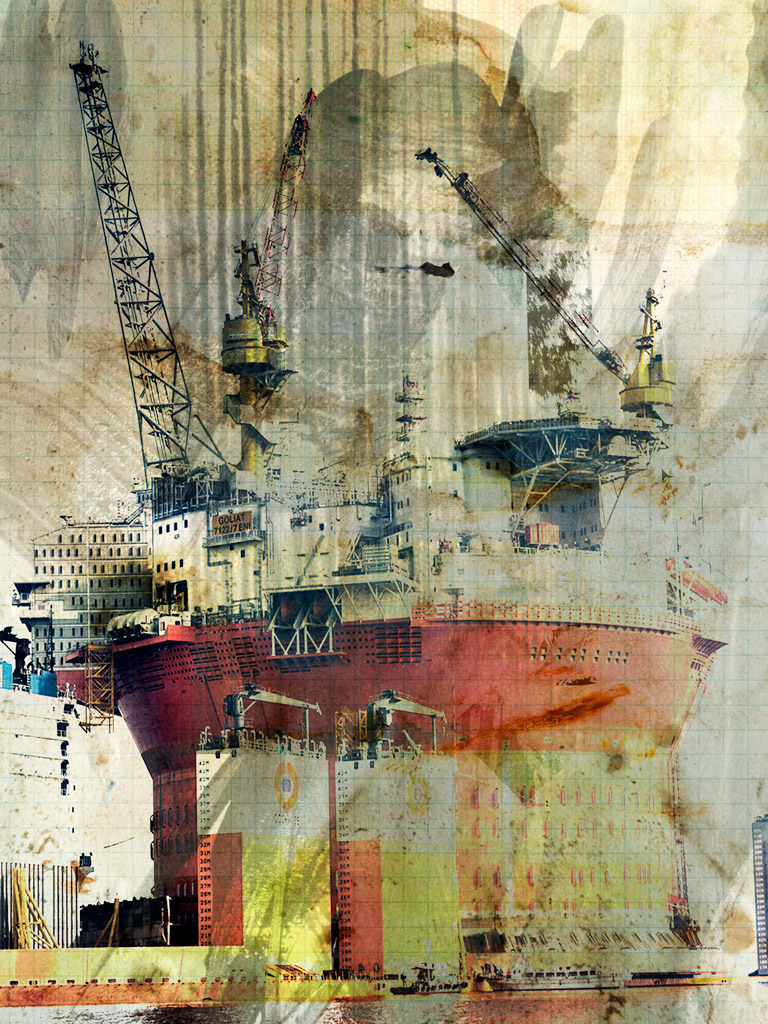

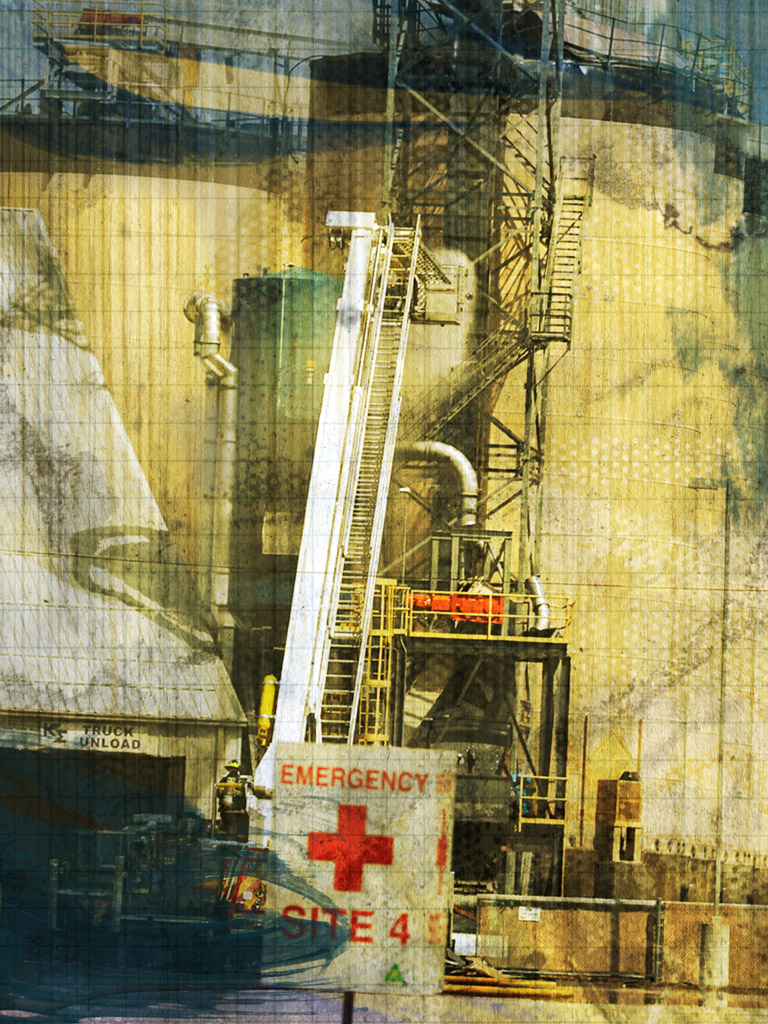

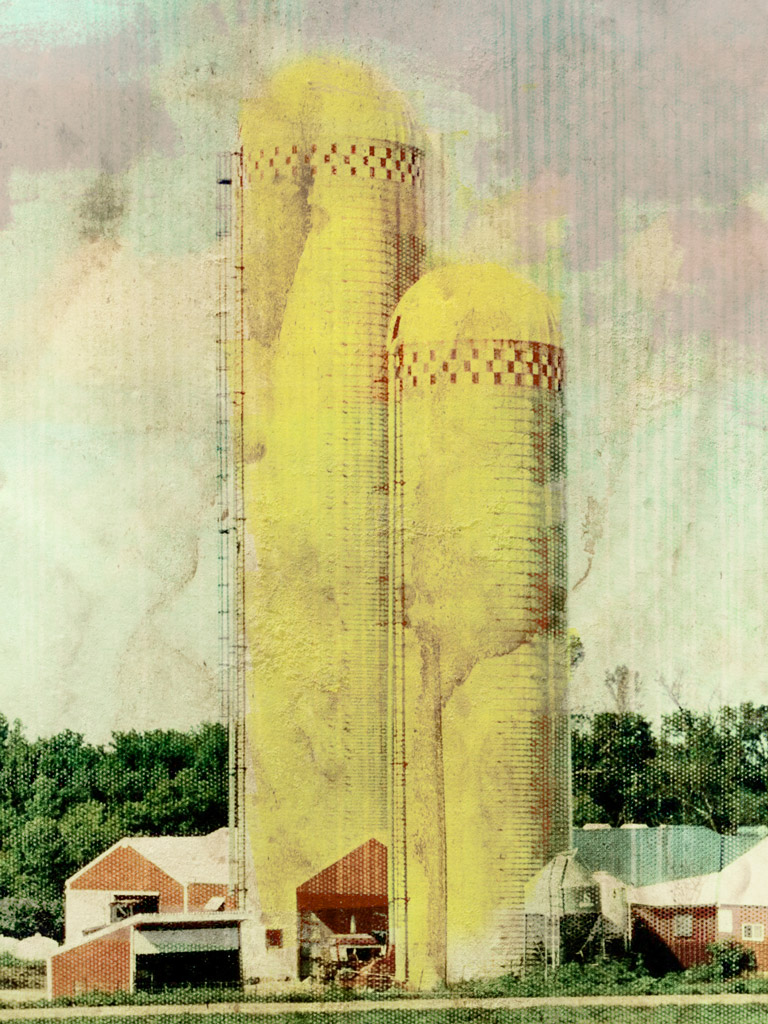

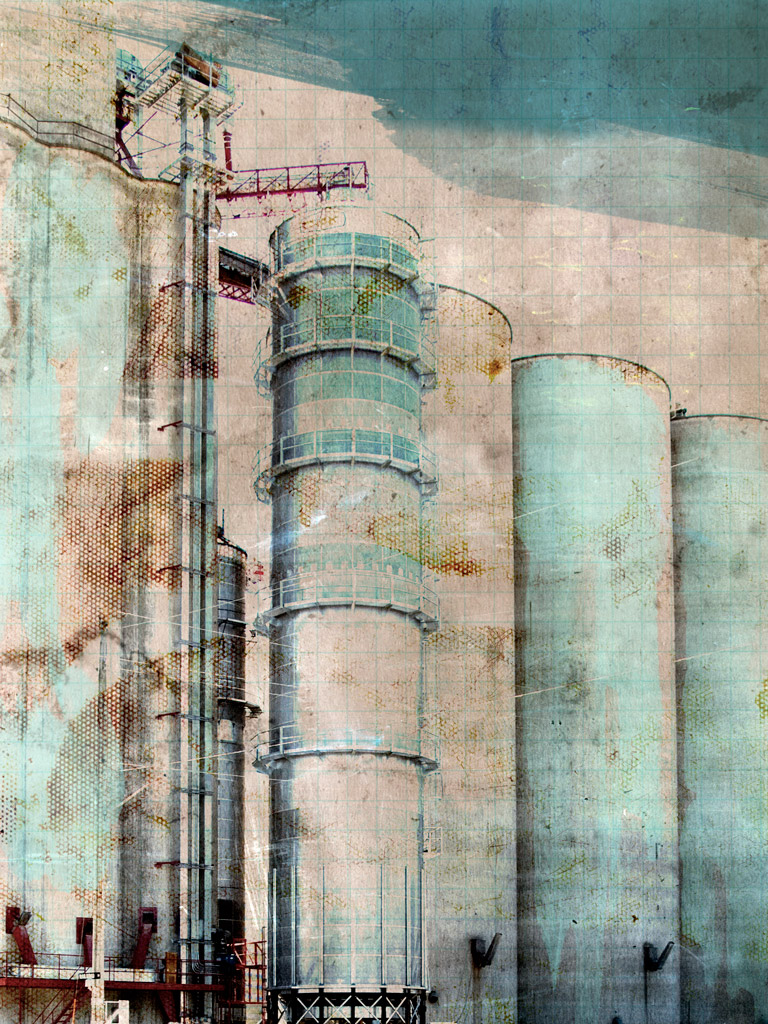

My latest project, called Binary Code, attempts to give visual expression to a world where databases and algorithms determine the ultimate reality, including nature. This is essentially the end of the order of nature as we know it.

And for some reason I can’t explain, the whole series consists of images of women and industrial silos. It could be because my files are full of these images which I have always found fascinating although I could also be trying to justify it as the end of a fundamental symbol where the woman and uterus are no longer relevant symbols for representing fertility, reproduction, beauty or nature.

I would like to comment on an aspect that is important for me. The criteria on the basis of which the artist selects an “appropriate” object may vary but the relationship between artist and subject is never univocal. The artist is only one of the parts. The object rebels and fights for its real nature, reacting to manipulation and boycotting it. The sign-object maintains some of its original nature, however much it fights against it. I think this negotiation between idea and reality is what makes appropriation so interesting.

ZZ. How does having sources with such diverse origins affect the narrative and timing of your images?

M. Nothing has different origins. Our only access to reality is mathematics, and quantum physics has eliminated time as an explanatory element for the behavior of elementary particles. Stripping photography of narrative and temporality is a lofty and necessary goal.

Narrative and temporality can be analyzed from many perspectives. For example, for Cyborg art, time is irrelevant because it can accumulate and eliminate modifications from its code indefinitely, meaning that there is no original or copy. Another less visionary example would be the way we experience the Internet today, jumping from one hyperlink to another, breaking up the original narrative structure of a text. Narrative as a mechanism and source of truth only continues to operate in Hollywood.

But it is a complex topic, because with narrative and temporality, what we are talking about is the issue of meaning. Refuting narrative entails resisting a set meaning that permits redemption (here I am referring to Adorno’s famous essay on Beckett). Eluding narrative prevents access to the comfortable world of history and fable.

In Binary Code there is no narrative. There are simply visual objects seeking to reclaim their meaning in their material specificity. Binary code, from its maximum abstraction, creates objects whose significance is drawn from its materiality rather than the code. The disenchantment of modern nature, its non-meaning, does not prevent nature from speaking through our bodies, desires, suffering and needs. By reclaiming the object, this project calls for a return to aesthetic materialism (albeit in an updated form).

If you think about it for a moment, it may also be time to reclaim the Aztec god Ometeotl as a contemporary symbol. Ometeotl, the immanent, invisible and immaterial god who had no temple, is the creator of all dualities (and therefore predates them): time and space, male and female, day and night, matter and spirit, zero and one. He is the creator of everything. Ometeotl is the binary code.

Max de Esteban (Spain). A fine-art photographer. Holds a Graduate degree from UPC, a Master from Stanford University and a PhD from URL. He is a Fulbright Alumni. His work is organized in two distinct bodies: Elegies of Manumission and Propositions. Awards: the 2010 National Award of Professional Photography (Spain)- Gold LUX.[2] and Grand Prix Jury's Special Award, Fotofestiwal 2010, Poland.

Max de Esteban (Spain). A fine-art photographer. Holds a Graduate degree from UPC, a Master from Stanford University and a PhD from URL. He is a Fulbright Alumni. His work is organized in two distinct bodies: Elegies of Manumission and Propositions. Awards: the 2010 National Award of Professional Photography (Spain)- Gold LUX.[2] and Grand Prix Jury's Special Award, Fotofestiwal 2010, Poland.

ZZ. What led you to appropriation and remix and how are they significant in your work?

M. Appropriation and remix have a long artistic tradition, beginning with Picasso’s collages. As early as the 1920s, Hannah Hoch and the Dadaists used this mode of expression to create major photographic works. In music, for example, from today’s DJs and Pop to Glenn Gould and Miles Davis, the practice of remix, collage and appropriation has been an essential part of their production. What I mean is that as an artistic concept, appropriation and remix are pretty standard and not particularly groundbreaking.

The interesting question is why their aesthetic power has been reasserted in photography precisely now. And I think one possible answer would be the combination of the formal exhaustion of the linear perspective as a photographic representation of the world and the huge impact digitization is having on every aspect of our lives. I would answer your question by turning it around and saying I find it hard to think of a truly relevant form of photography for the world we live in that continues to respect the Eurocentric, reactionary structure of the dark room.

ZZ. What do you mean by Eurocentric and reactionary?

M. The linear perspective, the visual structure resulting from the dark room, is a very particular and ideological way of visualizing the world. Panofsky has a text about it he wrote in 1927, a real classic, that is a pleasure to read.

But what is really remarkable is that it is an exception in art history. In 10,000 years of history, the linear perspective spans only 500 years and is located exclusively in the West. It has never been of interest to Asian, or pre-Columbian or African art ... it is a European way of seeing in a period beginning in the Renaissance and ending in the 19th century.

And this is no coincidence because its ideological content is well known. The linear perspective arranges the world from the point of view of an autonomous individual whose individuality is the world’s principle of meaning. It is pure Descartes. And we all remember Descartes’ Fifth Meditation, which states that since the essence of matter is its extension, geometry is an essential instrument for understanding nature. Modernity can be defined as the advance of abstraction and the prevalence of the quantitative over the qualitative in which the mathematical-scientific order is regarded as the only source of valid knowledge. There is so much contemporary thought that debunks this narrative that I won't repeat it here.

Thus, surprisingly, my earlier comment is still valid. Why should digital photography continue giving priority to a functionally and ideologically devalued visual structure?

ZZ. Why do you think digital photography changes the way we understand appropriation and remix?

M. Digital technologies are leading us towards the radical transformation of our world. By replacing the industrial economy with a bio-cybernetic system, digitization is modifying our environment, our subjectivity and soon, our bodies. This is the technological phenomenon that will define our era and therefore our culture.

Unlike an analog file, a digital file is invisible. It is a code whose visual expression is a translation highly mediated by default algorithms, whose most prominent feature is precisely its immateriality.

This technical structure fits our current era of abstraction and non-referentiality and the digital financialization of the economy. How do we see the world today? We have the answer on our computer and Smartphone screens. What is the essential aspect of the financial economy? The recombination of existing information units to create new information, in other words, “constructive compositing”. Digitization has definitively invalidated linear narrative, the monocular perspective and the author’s “authority”.

ZZ. You attach a great deal of importance to the concept of technology in your work. Could you explain why?

M. We are moving towards a world as a “technological whole”. Technical manipulation has already invaded our bodies, the last frontier, and no-one doubts that having machines inside our bodies will soon become commonplace.

The cyborg raises more complex issues for our species, which, though somewhat deteriorated, continues to maintain the autonomy of the subject as an essential value. Abstraction, digitization and cyborg are three sides of the same coin that heralds our new world, whether we like it or not. In my opinion, reflecting on technology is necessary, urgent and politically essential.

ZZ. And how do you think technology affects the practice of photography?

M. I’d like to point something out. One of the problems of photography is the confusion between technology and use. Writing is a communication technology that serve to draw up a commercial contract and compose a poem by Virgil. It is the same technology but nobody would ever mistake Virgil for a notary. In photography, we tend to combine uses, which creates enormous confusion in critical discourse. Throughout this interview, I have been referring to the use of photography as a means of artistic expression.

The thing is that photography has always been halfway to a cyborg. It is a machine that affects and to some extent determines human power, thought and expression and is therefore an ideal place for reflecting on the issues I mentioned earlier.

To give you an example: How can you visually depict the abstraction of the economy when the material references of wealth have been replaced by a binary code? That’s what I’m doing at the moment and it forces me to rethink what “representation” means in this new visual regime.

Another example: How does the idea of the cyborg affect art categories? That’s the topic I try to get my teeth into in the text “Cyborg Art: art in the bio-cybernetic era”. And there are a thousand other possible ideas that make photography an exciting medium at this particular historical time. The point is that if photographic practice does not take up the challenge raised by contemporaneity, it will be relegated to banality and antique shops.

ZZ. How do you choose the sources you use and what significance do they have for your series?

M. Like nearly everything in life, it is a combination of determination and chance. In my case, too much planning and/or reflection in my work paralyzes me while dreams or rather daydreams are of paramount importance.

My latest project, called Binary Code, attempts to give visual expression to a world where databases and algorithms determine the ultimate reality, including nature. This is essentially the end of the order of nature as we know it.

And for some reason I can’t explain, the whole series consists of images of women and industrial silos. It could be because my files are full of these images which I have always found fascinating although I could also be trying to justify it as the end of a fundamental symbol where the woman and uterus are no longer relevant symbols for representing fertility, reproduction, beauty or nature.

I would like to comment on an aspect that is important for me. The criteria on the basis of which the artist selects an “appropriate” object may vary but the relationship between artist and subject is never univocal. The artist is only one of the parts. The object rebels and fights for its real nature, reacting to manipulation and boycotting it. The sign-object maintains some of its original nature, however much it fights against it. I think this negotiation between idea and reality is what makes appropriation so interesting.

ZZ. How does having sources with such diverse origins affect the narrative and timing of your images?

M. Nothing has different origins. Our only access to reality is mathematics, and quantum physics has eliminated time as an explanatory element for the behavior of elementary particles. Stripping photography of narrative and temporality is a lofty and necessary goal.

Narrative and temporality can be analyzed from many perspectives. For example, for Cyborg art, time is irrelevant because it can accumulate and eliminate modifications from its code indefinitely, meaning that there is no original or copy. Another less visionary example would be the way we experience the Internet today, jumping from one hyperlink to another, breaking up the original narrative structure of a text. Narrative as a mechanism and source of truth only continues to operate in Hollywood.

But it is a complex topic, because with narrative and temporality, what we are talking about is the issue of meaning. Refuting narrative entails resisting a set meaning that permits redemption (here I am referring to Adorno’s famous essay on Beckett). Eluding narrative prevents access to the comfortable world of history and fable.

In Binary Code there is no narrative. There are simply visual objects seeking to reclaim their meaning in their material specificity. Binary code, from its maximum abstraction, creates objects whose significance is drawn from its materiality rather than the code. The disenchantment of modern nature, its non-meaning, does not prevent nature from speaking through our bodies, desires, suffering and needs. By reclaiming the object, this project calls for a return to aesthetic materialism (albeit in an updated form).

If you think about it for a moment, it may also be time to reclaim the Aztec god Ometeotl as a contemporary symbol. Ometeotl, the immanent, invisible and immaterial god who had no temple, is the creator of all dualities (and therefore predates them): time and space, male and female, day and night, matter and spirit, zero and one. He is the creator of everything. Ometeotl is the binary code.

Max de Esteban (Spain). A fine-art photographer. Holds a Graduate degree from UPC, a Master from Stanford University and a PhD from URL. He is a Fulbright Alumni. His work is organized in two distinct bodies: Elegies of Manumission and Propositions. Awards: the 2010 National Award of Professional Photography (Spain)- Gold LUX.[2] and Grand Prix Jury's Special Award, Fotofestiwal 2010, Poland.

Max de Esteban (Spain). A fine-art photographer. Holds a Graduate degree from UPC, a Master from Stanford University and a PhD from URL. He is a Fulbright Alumni. His work is organized in two distinct bodies: Elegies of Manumission and Propositions. Awards: the 2010 National Award of Professional Photography (Spain)- Gold LUX.[2] and Grand Prix Jury's Special Award, Fotofestiwal 2010, Poland.Aula de Creación Visual

HHamza has been for almost three years in Catalunya, he comes from Alger, the capital of Algeria.

"Truth be told, I don’t know how much longer I am going to stay here, it is all up to fate. I could go now or I could stay until… I don’t know, I truly don’t know."

"The thing that made me migrate is that I wanted to change. I wanted to change myself. I was in the wrong path and I wanted to change my ways, my friends, a little of everything because I was in the wrong path. (…) I came here all over from Marsella in train. I went out to the boardwalk and it was a Friday night, everyone was there, there was a party and some other things. I thought to myself “Wow” I thought it was amazing…"

"Of course I would go back to my country but not yet. I’ve got everything in there, family, is my land, my country, and I’ve got to be there. I have to be buried in Argelia, you know?"

Gerson is a youngster from Guatemala City. He started working as a model and interiorist but in order to grow he had to move to another country.

“I left my country because you can’t grow over there, the country is extremely poor and you just can’t. I think here, asking for help, you could get ahead (…) I didn’t come as a migrant because I had all my papers in order, I came here by plane and everything was going just fine, too fine (…) I only miss my family, but one must make sacrifices to get ahead so that is why I’m here.”

“I chose Spain because in the United States they keep an eye on migrants and it is harder to be there. My future here is look for a job, seek for ways to improve my life and bring my family here.”

Julian comes from the little city of Dosquebradas, one of the principal industrial core from Colombia.

“The truth is that the place where I come from is very dangerous, I kept myself involved in odd things and they were going to kill me. That’s why I moved here (…) I have been in Catalunya for two or three years and a year and a half locked. I do not know how much longer will I stay here. I’ll see what I do once I’m out.”

“Uf! What I remember the most of my country is my people, my family, my brothers and the party. Uy! Is what I remember the most. I would not think it twice, I would go back because all my family is there and danger is gone. I miss Colombia a lot, of course I would go back…”

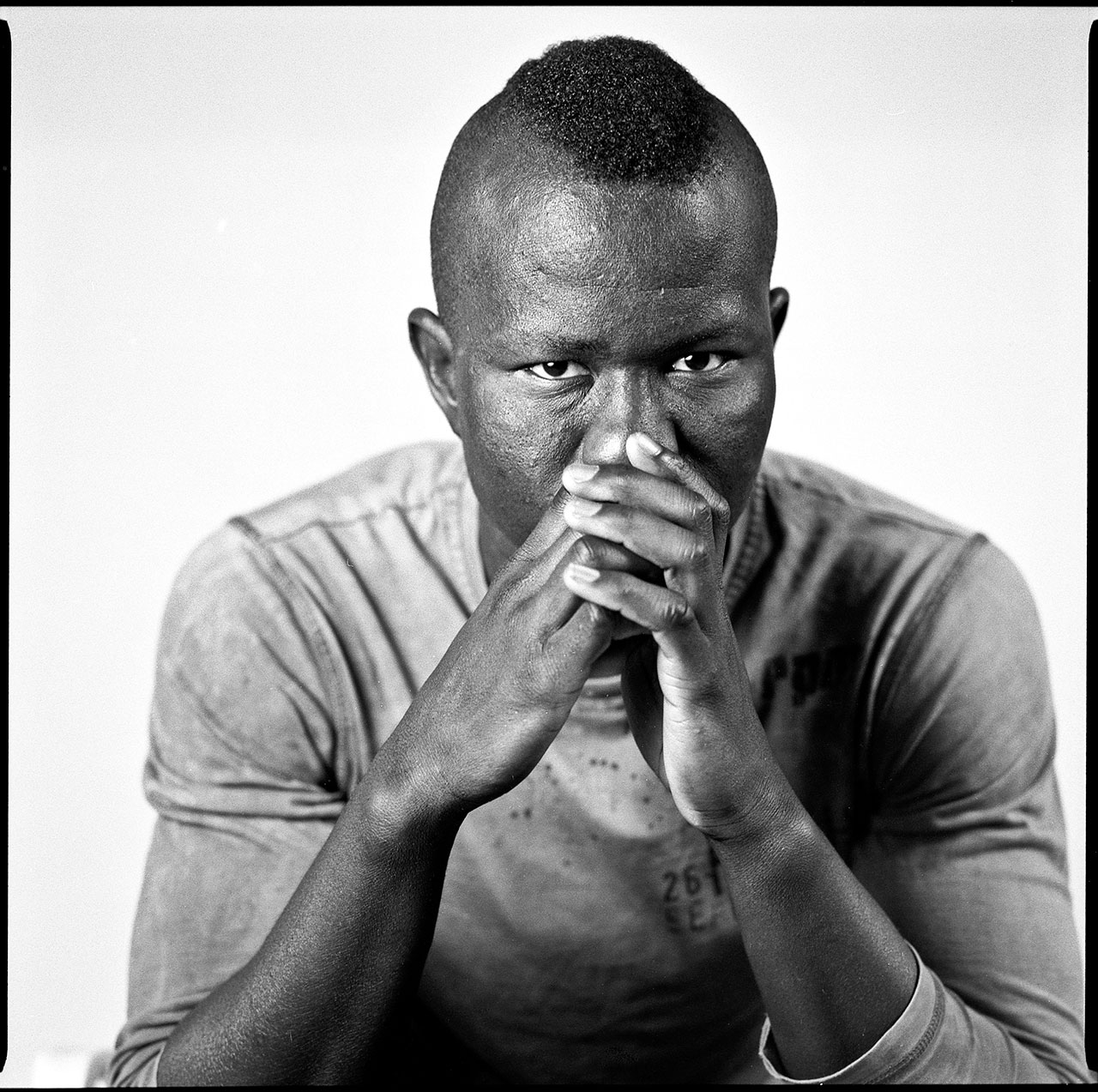

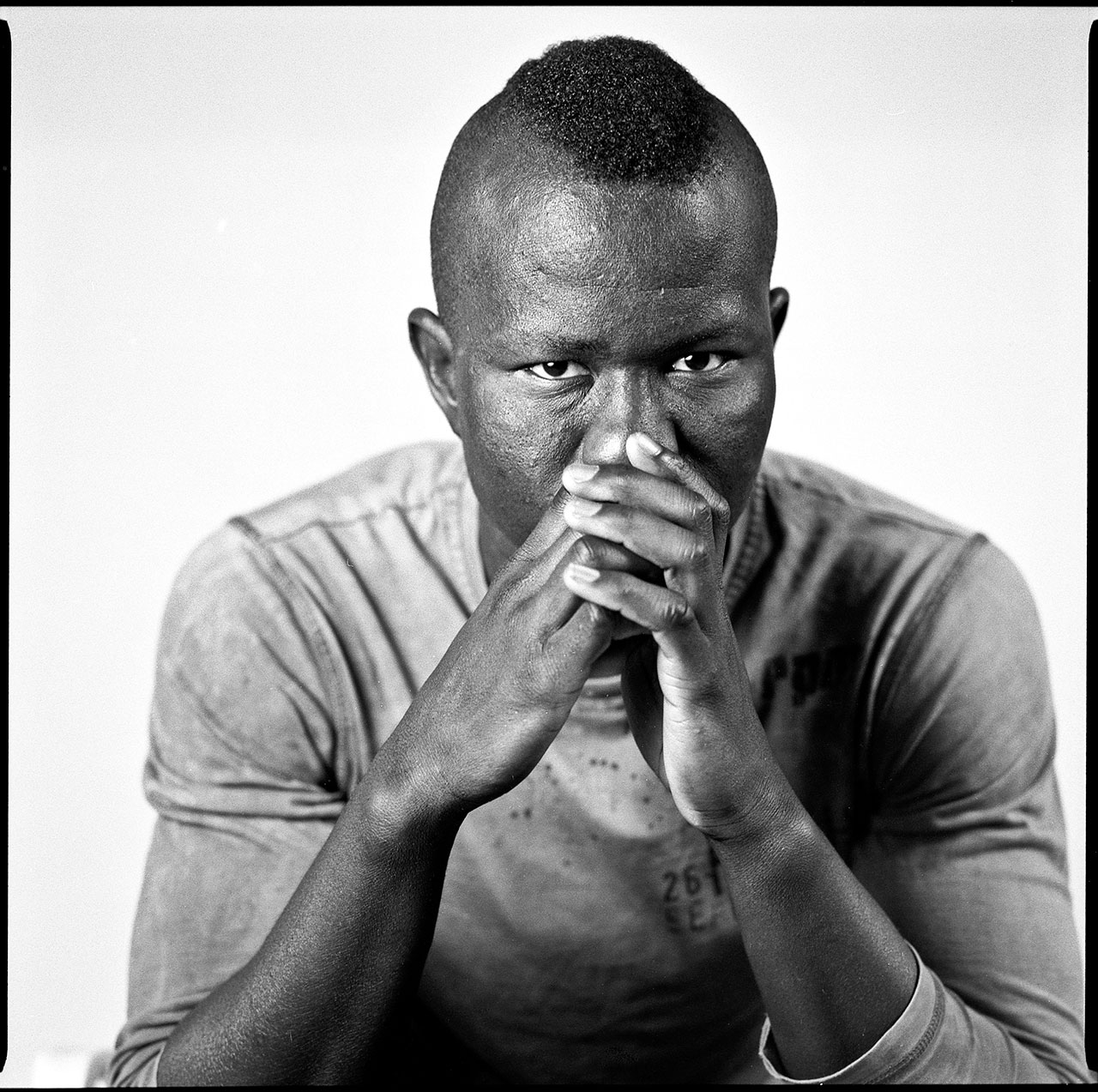

Mahmoud was born in Dakar, capital of Senegal. He has been in Catalunya for six years.

“I changed of country for many reasons. I though that once I get into Spain I could get some money, help my family, these kind of things (…) I arrived in ship from Mauritania to Tenerife. When I arrived some people took care of me because I was underage, I was 16, and they put me in a youth centre until I was 18. (…) I arrived to Europe to get a job, earn some money to help my family, to change their lives and the hard way they live right now there. That is what I thought…”

“We were 93 people in a ship that wasn’t big. It took us 6 days to get to Tenerife. I had never been in the sea, I continuously kept throwing up and dizzy. There were some people that were on the verge of dying but everyone arrived alive. (…) I though that it was a ship not a canoe. When I paid the money they told me it was a ship and I paid 1200 euros.”

“I saw many people that lived in Europe for 5 yeas and then they went back to my country and they had a house, a car, and then I think: How do these people got the money? I have been 20 years working and I just can’t anything, not even a house. Let’s see how is Europe.”

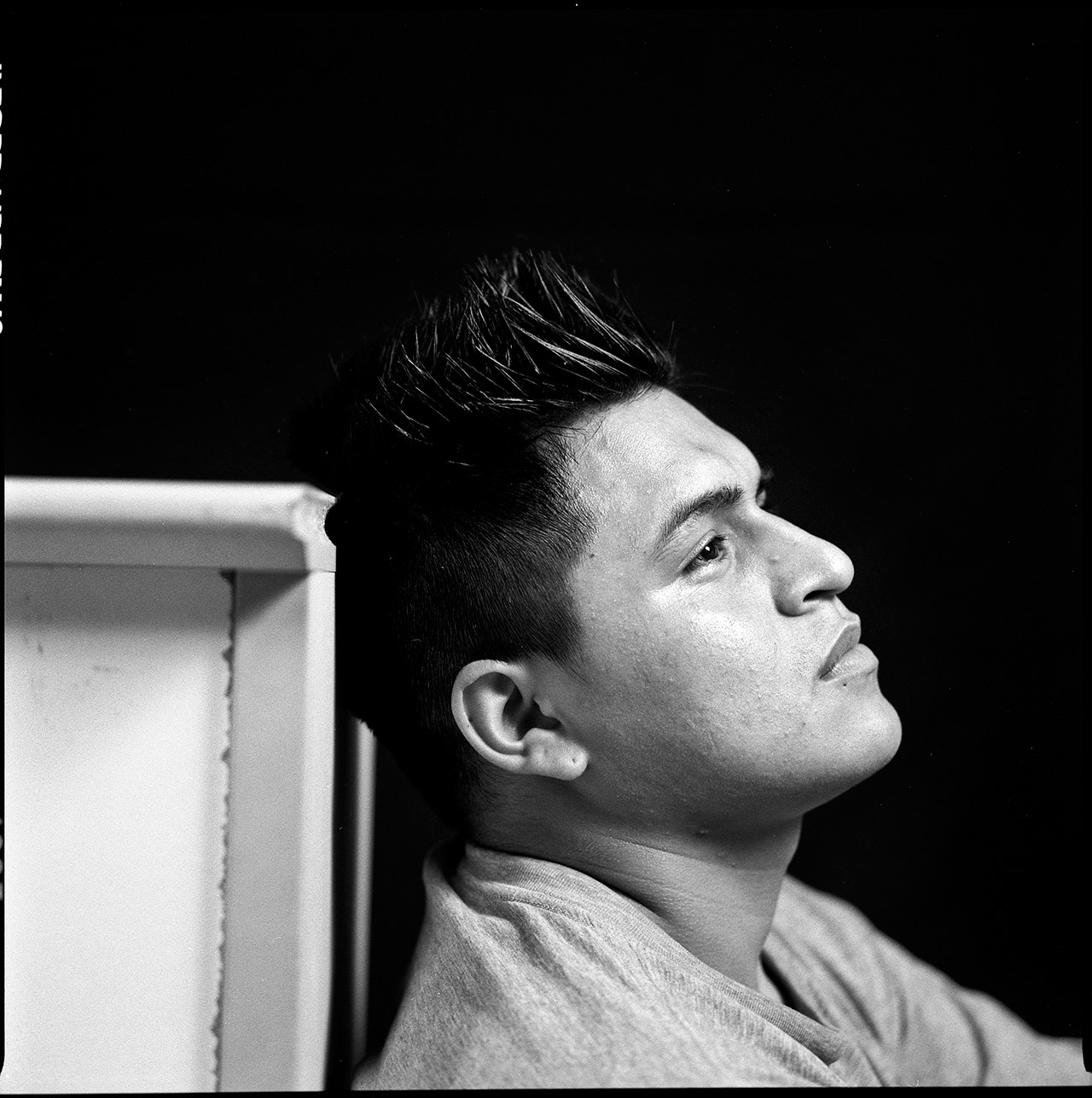

Ismael was born in the capital of Ecuador, Quito. But he has been in Hospitalet city for nine years.

“My mom took me here when I was little, I didn’t know anything, and now, here I am. (…) Right now I wouldn’t go to my country, if I ever go back is going to be for holidays. I would go back once I’m older, to die there and remain there always.”

“When I arrived here nothing seemed easy. I saw my mother working, working quite a lot, and she still does it. And no, as a child I didn’t see life and street as easy things. (…) I always lived in Hospitalet, my neighborhood was very problematic but as every neighborhood it has its good qualities. (…) I remember myself being at school and they picked up someone and started throwing bottles to him, he couldn’t go further from the entrance door, everyone was throwing bottles to him from there…”

Yassine doesn’t speak Spanish. He has only been in Catalunya for three months. His story of how life took him to Europe is the most singular story we found in this project.

Everyone calls him Sáhara. He was born in Dajla, the capital of a province of an old Spanish cologne of the Western Sahara. Today it is occupied by Morocco.

Against his willing, when Yassine was 15 years old, he went to Morocco to do his higher studies, but his support to the Sahara’s independence generate him a series of troubles with the authorities and was locked for 8 months in a Moroccan jail. When he finally achieved his freedom, his family did everything they could to expel him from the country until get, previously paid, a fake visa to go to Europe.

Romeo is Dominican but almost his entire life he has been in Spain.

“I came here when I was eight years old. I couldn’t decide where to go, my mother brought me. I have been here in Catalunya for 11 years, and the truth is, I didn’t think about the time I was going to stay…”

“I miss my entire country, specially the food. Rice with bandule, coco milk and cutlet… or the “Dominican flag”, rice with beans and meat (…)In the Dominican Republic, there are some people that have almost no money; and there are some others that have a great, great time.”

Edwin came to Spain for holidays in 2001. He came to visit his mother and never went back to Colombia.

“I was born in Colombia. My parents came to Spain when I was little and that is the reason I came (…) I thought that Spain was bigger, richer. It wasn’t heaven, but when you arrive here everything is different, you know?, You have to get used to a new culture, a new way of living. Everything is stranger but little by little you adapt yourself. (…) Colombia is very poor but the people are happier and fine with the things they have, they are very humble.”

“Too many deaths, it is not known when this is going to end. It is an intern conflict of the country, between the same Colombians. There is warfare, the drug dealing war, the war between hired assassins; there are too many wars that are never over. It’s one of the most unsafe countries in the world, although it’s a beautiful country, I would ask anybody that hasn’t ever been there to visit it.”

“The presidents of my country are not quite… correct. They are all corrupt. So, it is very difficult to have justice when all the politicians are the same.”

“I don’t know, for example, here you just hear a fire gun, pof! And that’s it. In Colombia when people listen to a fire gun they know someone has been shooted. They just know someone is dead, you understand?”

Samir went out from Alger, the biggest port in the north of Africa, almost ten years ago.

“I came inside of a van inside a ship. I arrived to Almería, I was a kid, and I got myself into of a youth centre and from there I have been in the same sort of places, youth centers (…) This country had a funny smell, seriously, nothing bad but weird, different than where I come from.”

“The memories I have are from when I was a little boy and I played with my friends of the neighborhood, my family (…) With some time I would definitely go back because it is my country, it is where I was born, where I have everything, where my people are. But not yet. I haven’t fixed my life here nor there, so, not until that happens. I have come here to do that, to create a life. I arrived when I was young and now it’s time for work. That is what I want.”

Andres abandoned Colombia when he was 10 years old. His last 10 years he has been in Catalunya.

“Well, I came here because of my mother; she had been here for about for years. She told me that life was going to… That life was going to be way better and that I would study and have everything I wanted, that I was going to have a much better future because the best things were here.”

“I miss everything. My family, the parties, the food, the women, the beaches. A little bit of everything. The culture and the atmosphere there is more cheerful.”

Albert is a 21-year-old prisoner born in Maresme, Premiá de Mar.

“I love my people. They will always help you. If you go to other places people don’t like this. (...) Ugh, my life there was a drift, I spent all day smoking and smoking... I wouldn’t stop from smoking and it was going out, but it was fantastic.”

“We would gather all in my house. Sometimes we were between 15 and 20 people in a room playing on the console and smoking. One day my father came and said: "What is this, a brothel or what?!" Everybody out! When people began to leave, he began to put his hand over the heads of the people and was counting 1 ... 2 ... 3 ... We fucked it big time, but I had a great time.”

“When you leave, you leave ... I will myself into a gardening course or nursing assistant, have a job and can save pennies in order to buy a house in the middle of the mountain. Live there, in the middle of nowhere and forget about people and be quieter.”

Silva was born in the north of Brazil although he was raised in Sao Paulo. He never intended to stay in this country.

“Destiny’s bad. I was to Turkey, well, actually I was going to Japan to give something I had and made a scale in Turkey. Coincidentally, I came here and something went wrong and here I am. Not because I want to, or I wanted to stay in Spain. I’m here due to my bad luck in life.”

“I can’t tell you my impression of Spain because I wasn’t in the street. For the moment, my impression is based on what I’ve seen here in jail. I thought it was very dangerous, like my country’s jails, that people kill each other. And no, totally different, everything is quite relaxed (…) When I arrived to Trinidad I had a problem with a Moroccan and I thought that I had to fight to death with him to gain respect. I had the mentality of my country, you know? And no, they just locked us into our cells and that was it. Very different from my country. I got into jail when I was 17 in a Youth Center and in my first fight they stabbed me. Then I did it back to gain respect. I had been there for only five months and I got stabbed, I blacked out and they took me to the nursery. All in five months!”

“You always go back from where you came from. It is clear; I’ve got a long way back, that is why I have to go back to my family, to my roots.”

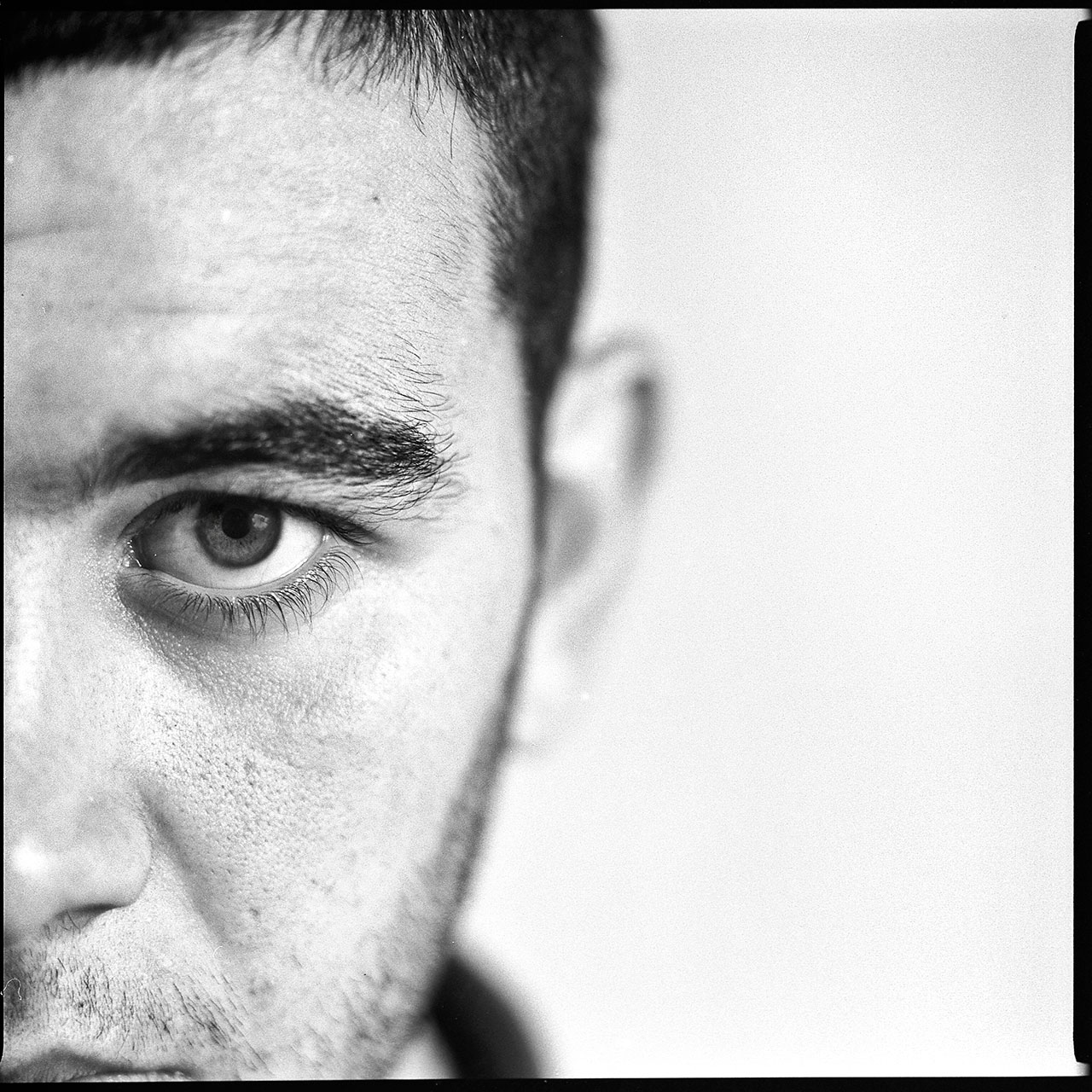

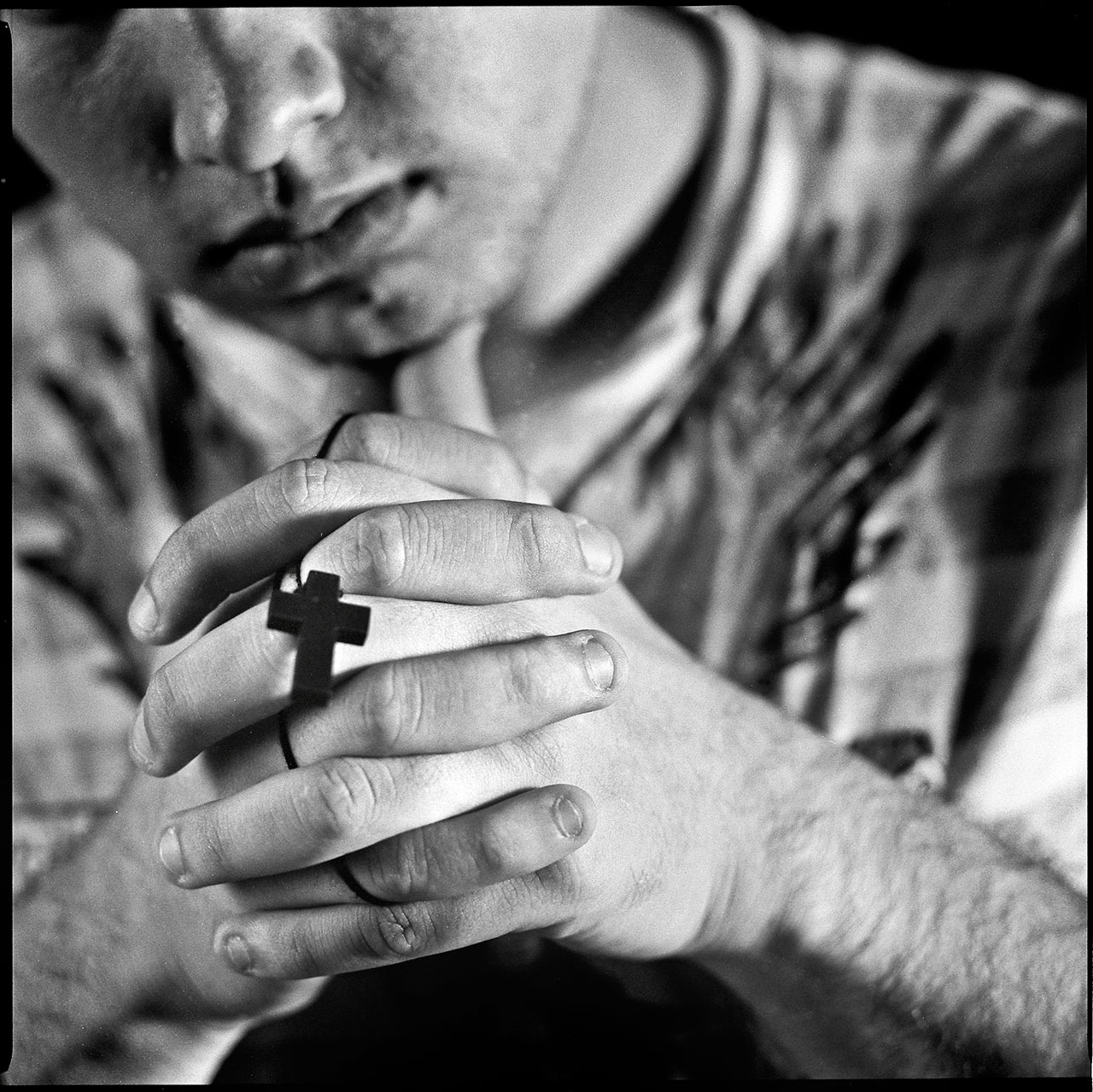

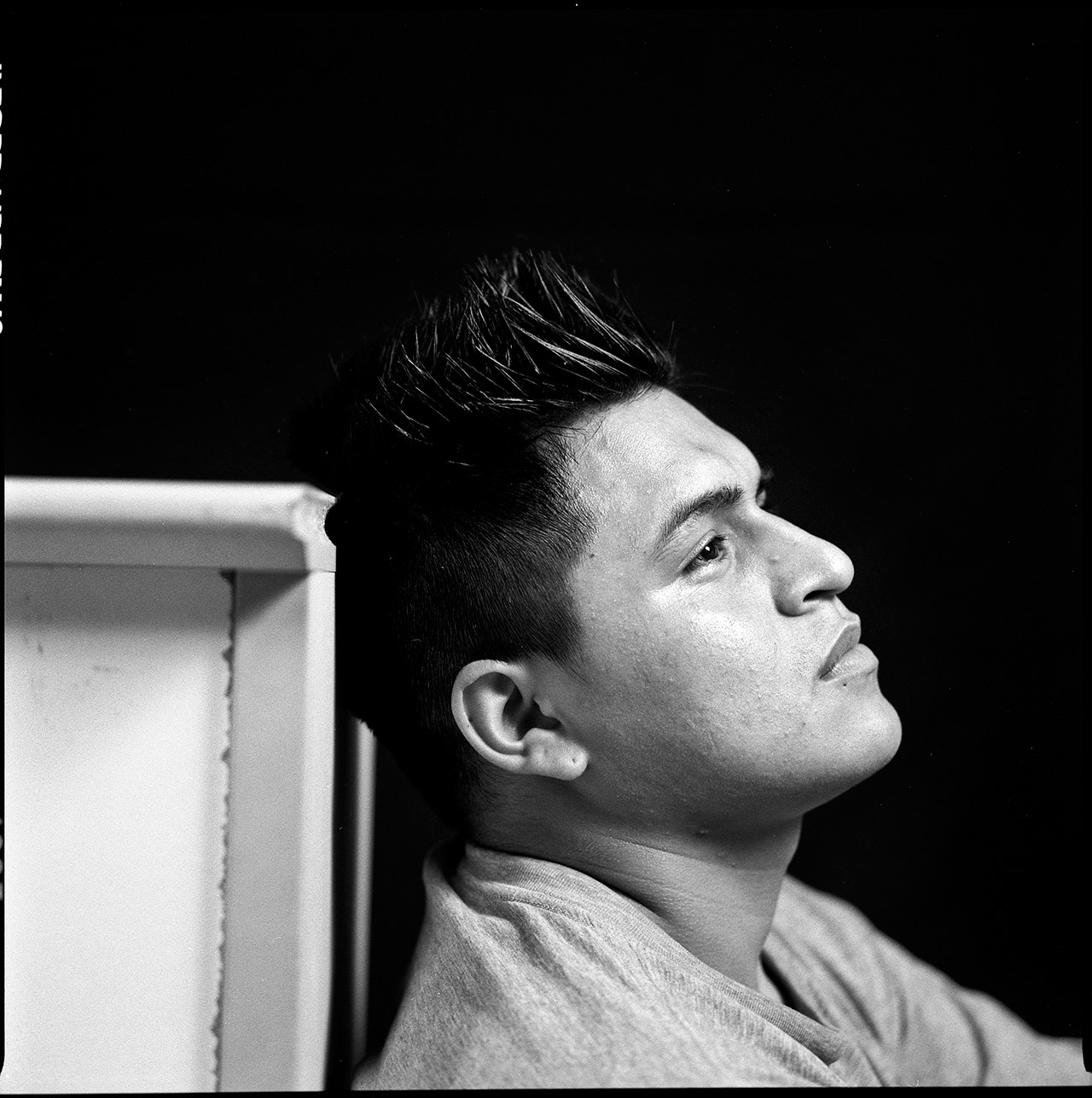

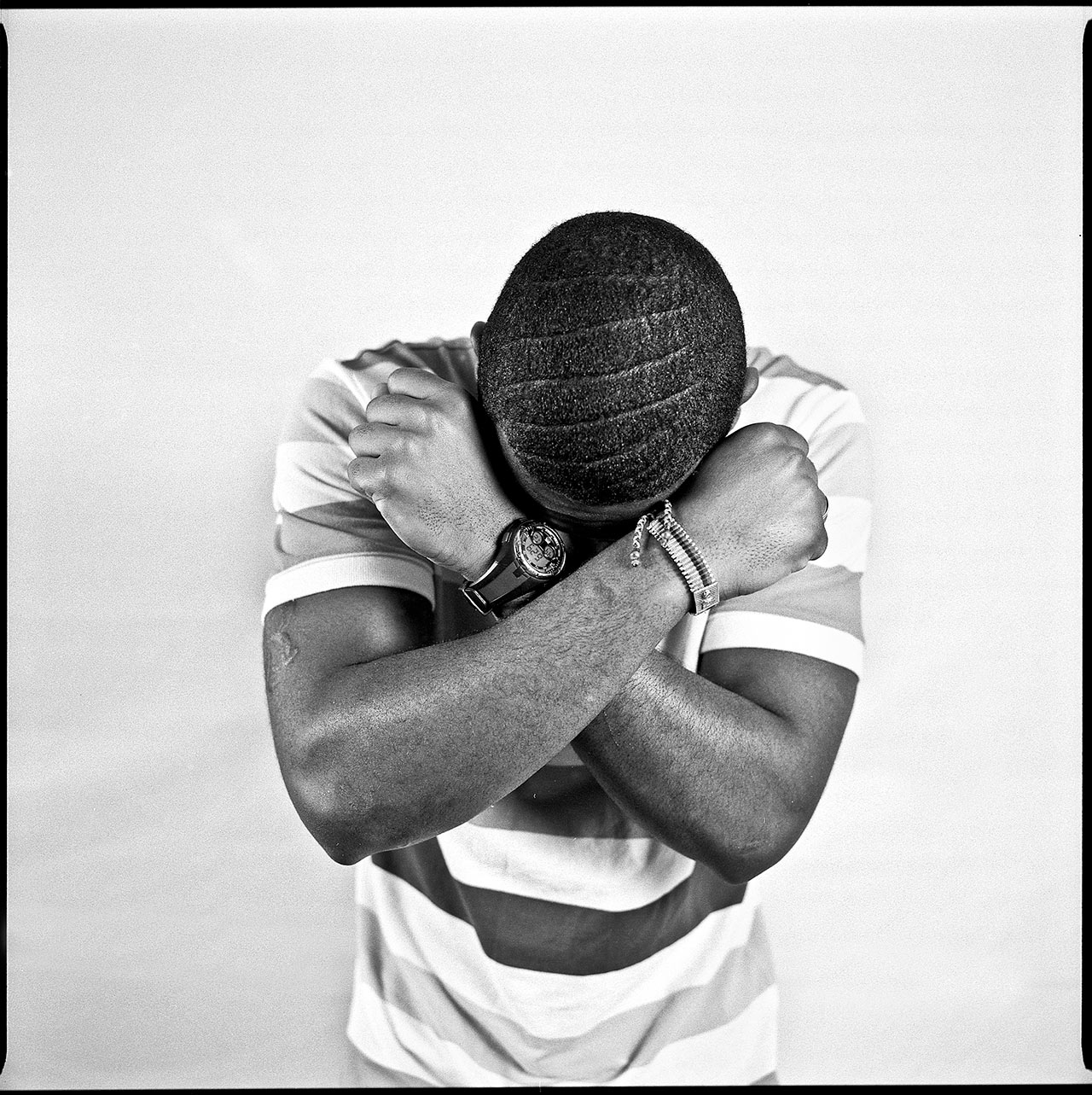

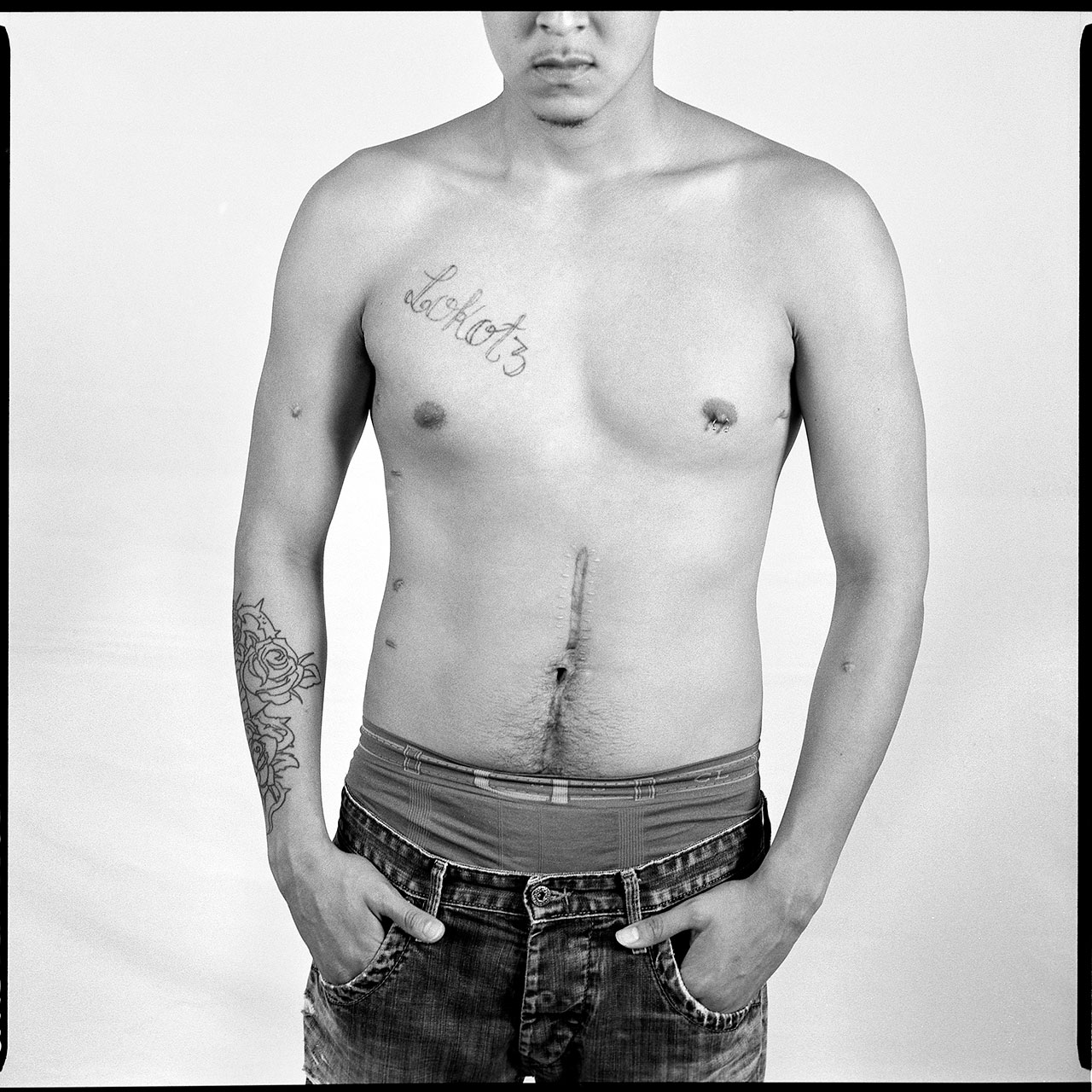

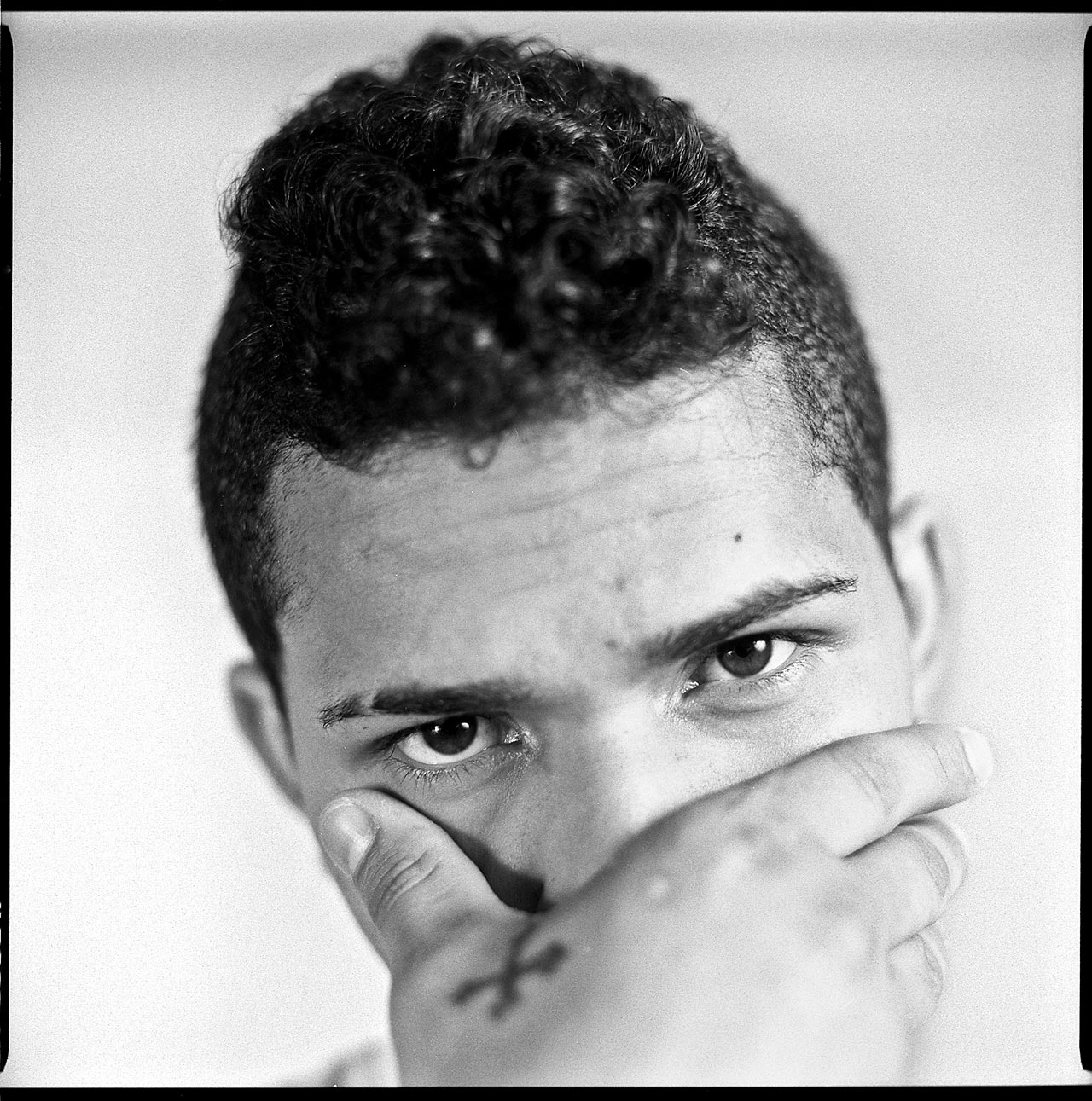

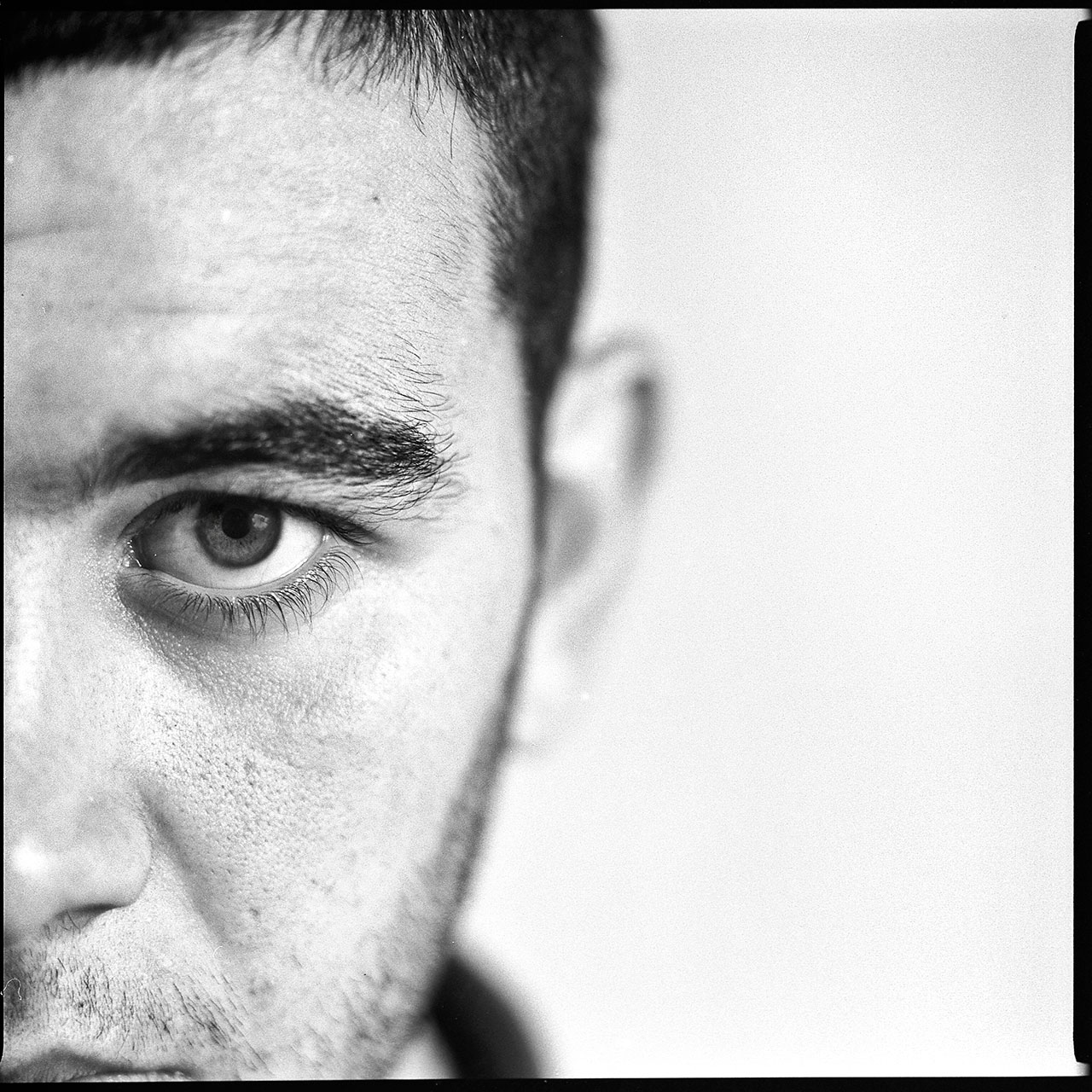

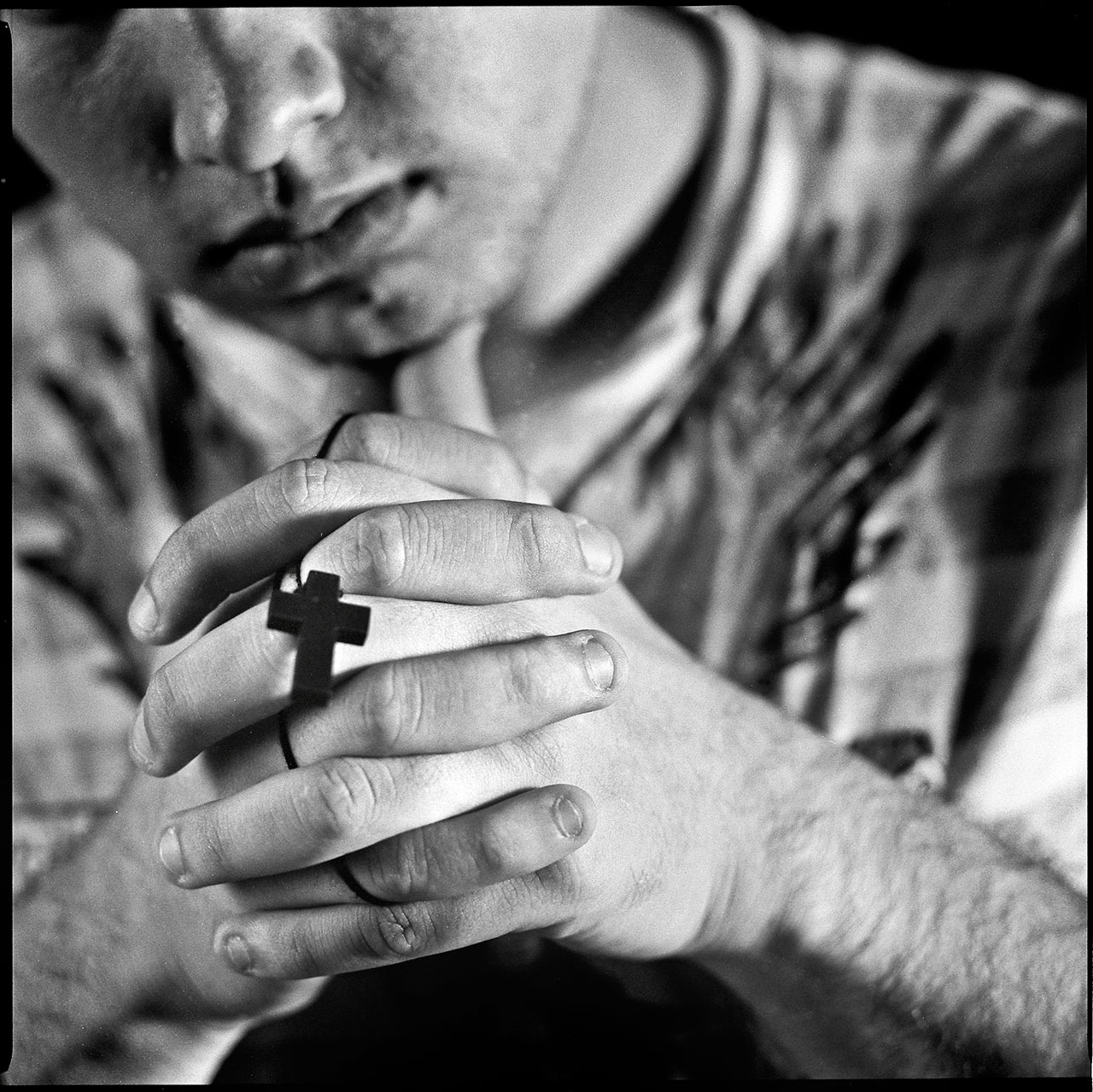

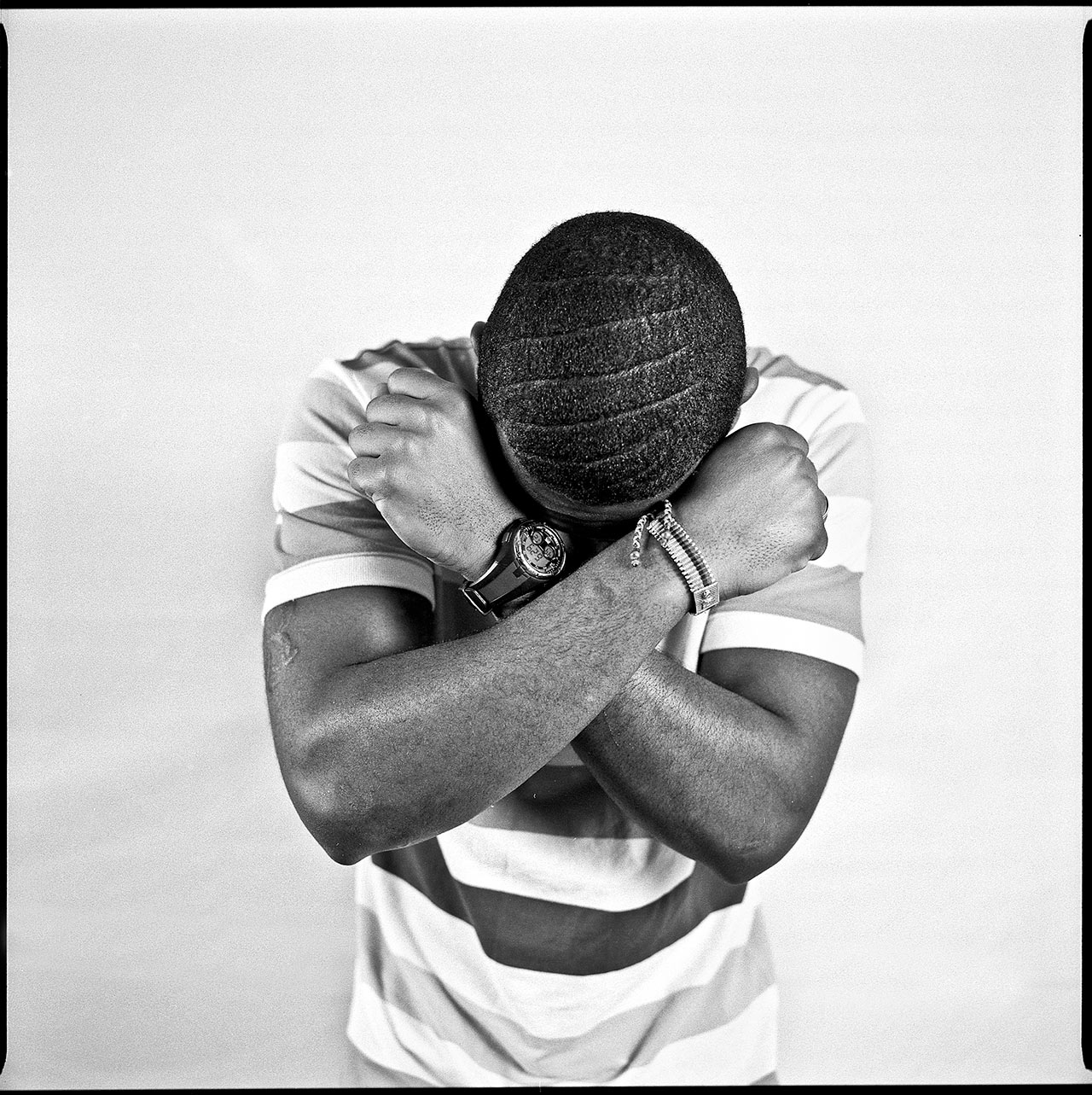

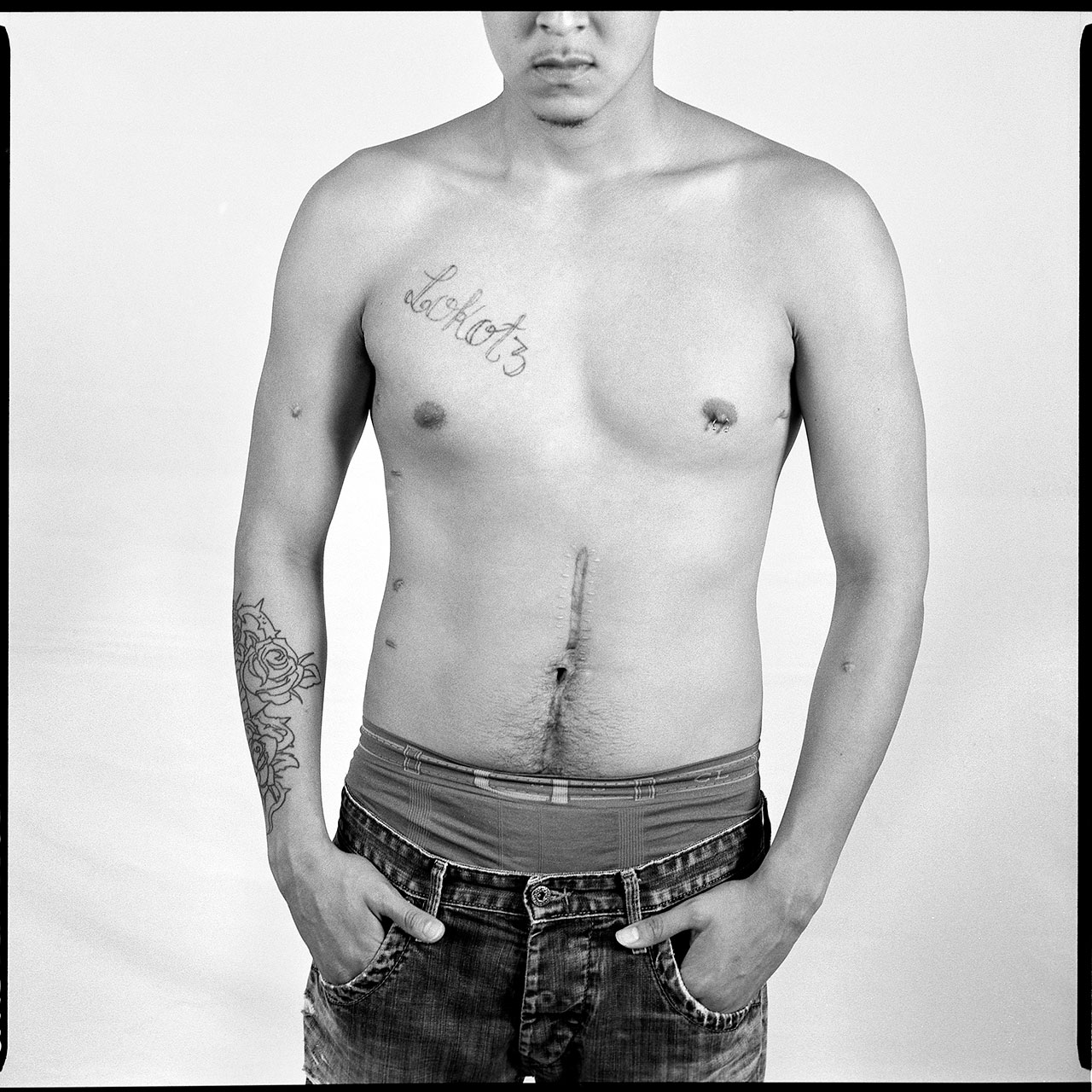

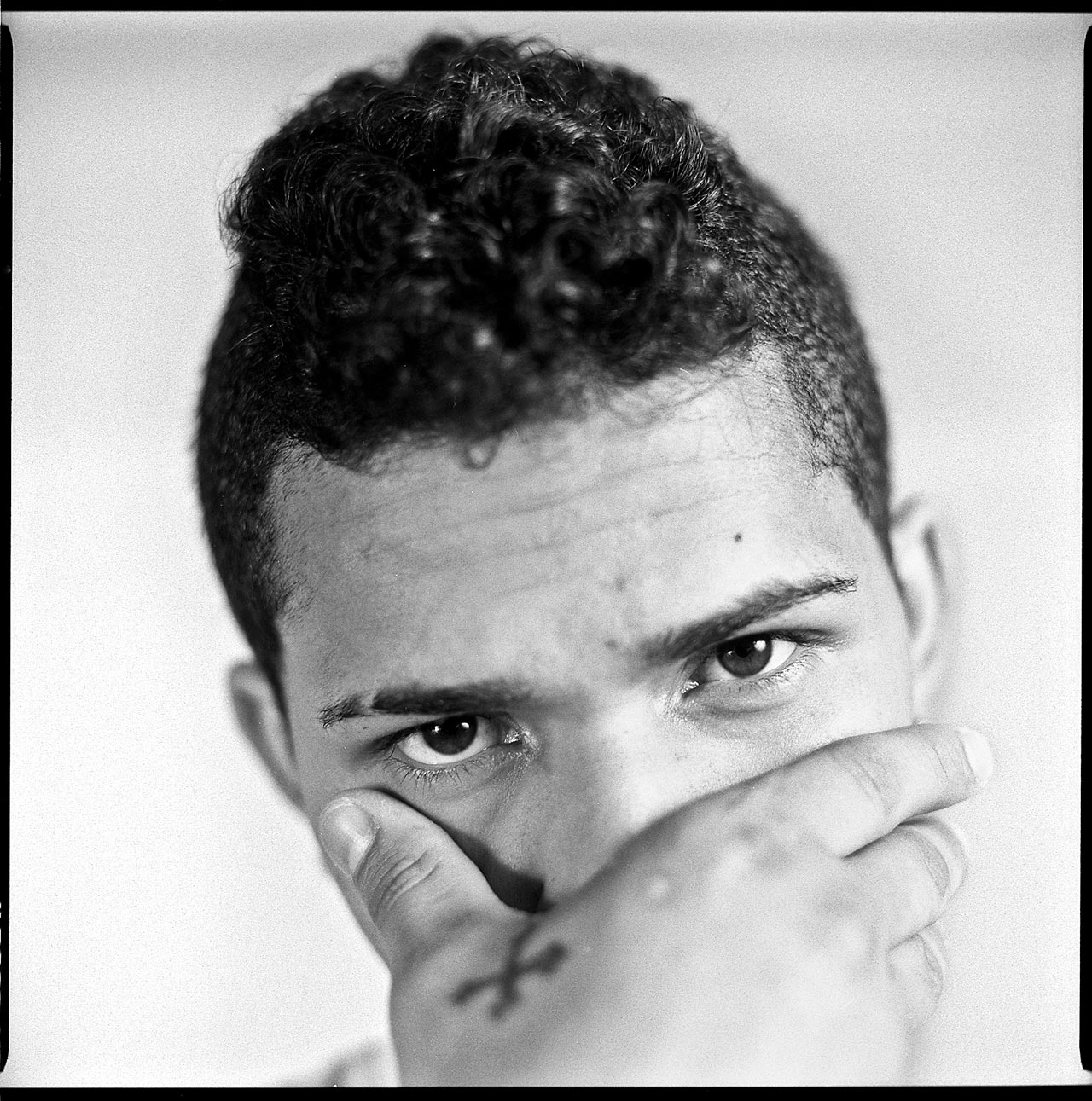

According to official data, 75% of the prisoners inside Catalunya Youth jail are migrants from outside of Europe. The other 25%, half are Europeans from outside the EU. Therefore, we found an overwhelming data in the Catalunya Youth jail: the 87.5 % of the prisoners are foreigners, coincidentally, the group with the less economical resources of our society.

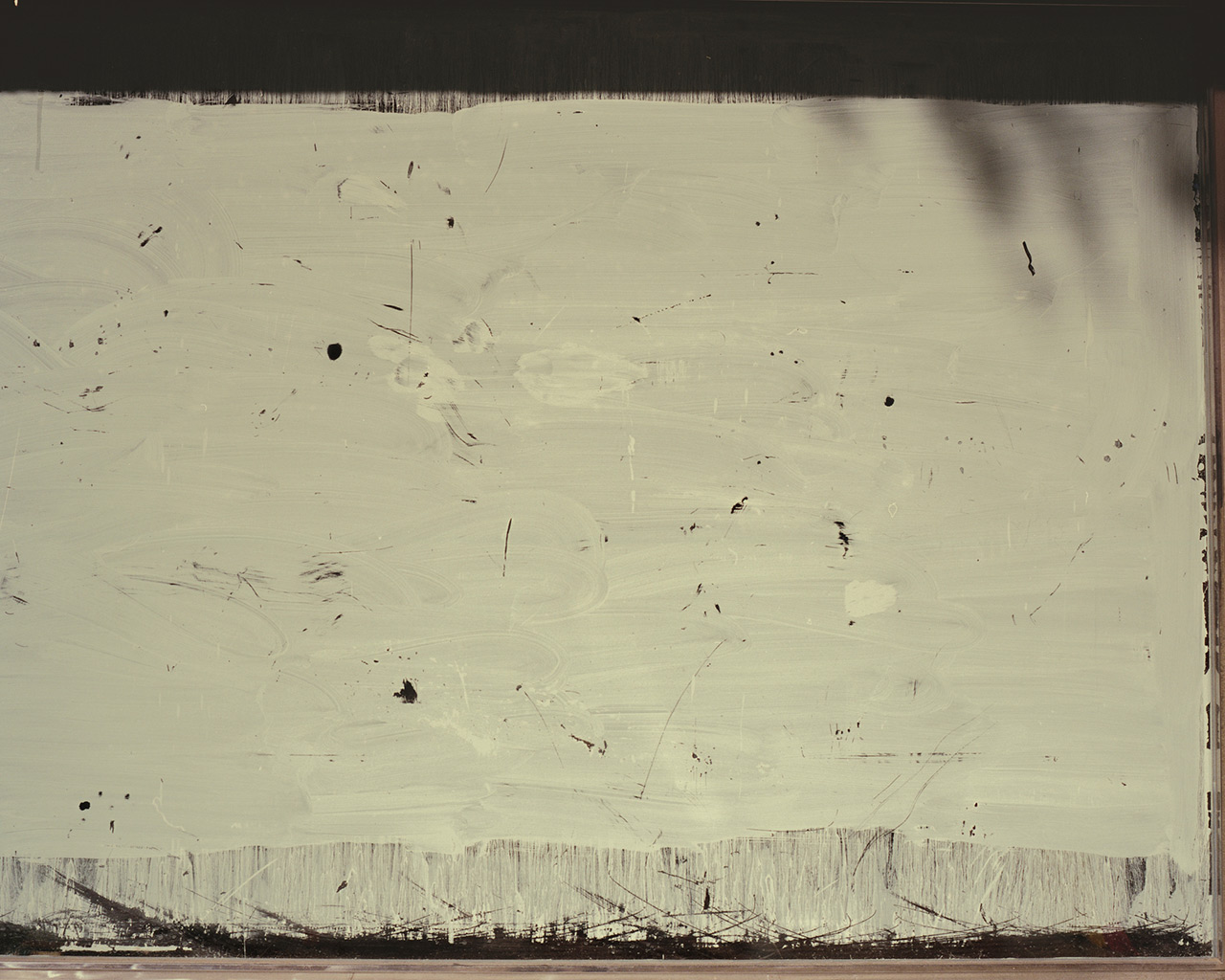

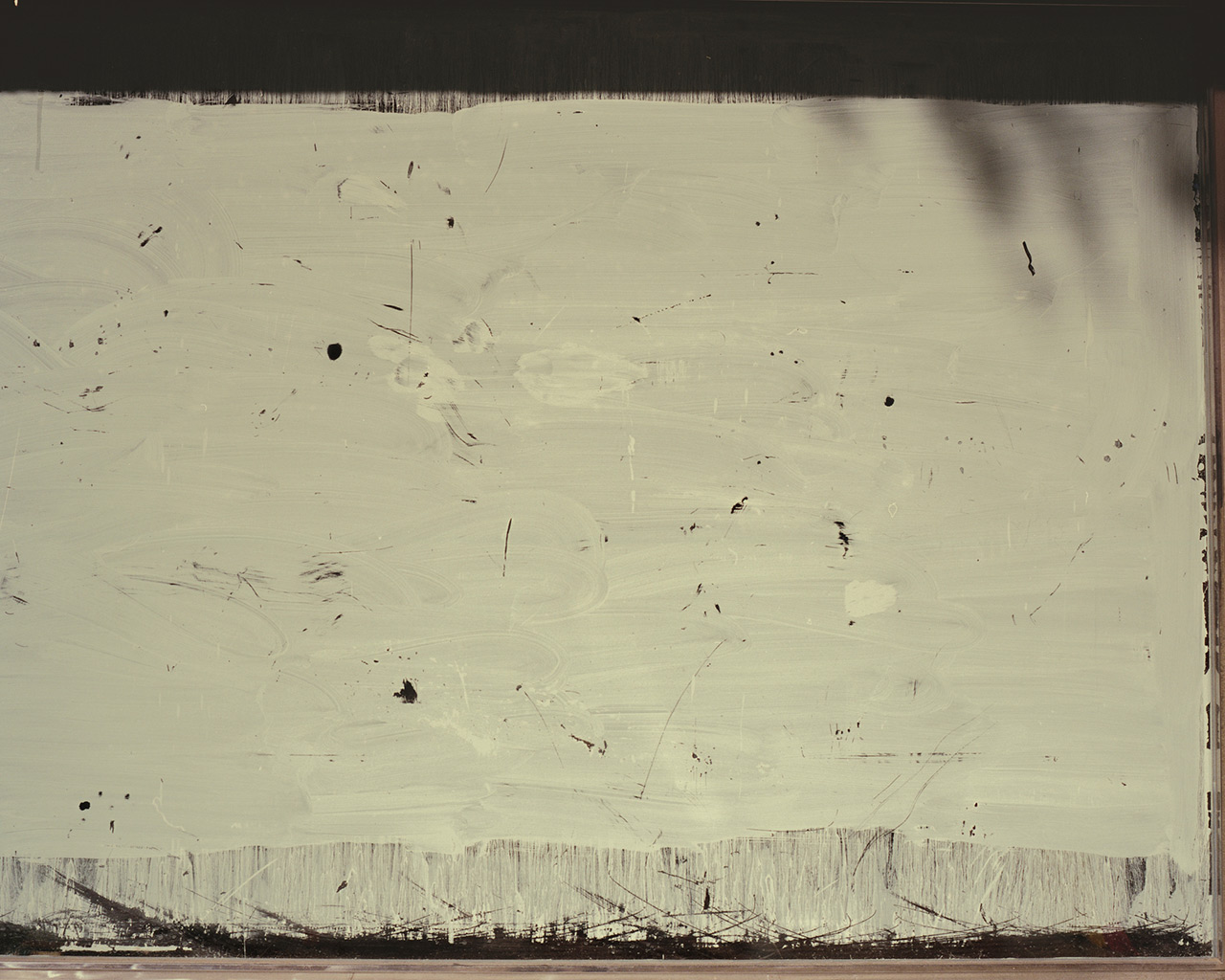

These images have no author. It is almost impossible to know who is the creator of each and every 6cm x 6cm negative. The process where the 12 photography sessions in which these images were made, from the outside may appear as a great chaos. Photographers took turns behind the Bronica camera, took two or three shots of prisoners with different backgrounds, and few seconds later a new eye appeared behind the lens. The rest of the group measured light, focused the lens, or gave posing ideas to the model. The session was over once the reel was full.

Making a portrait of half format project does no intend to be an exact replica of the Multiculturalism behind the walls of these jails. This project was just an excuse to join the youngsters from different roots in an improvised photography set and talk. Talk about their history, their journeys, their memories, and their lands. Testimonies that teach us that the world is not necessarily black and white, that there is no good or bad, and that luckily everything is more complex.

ACV. VCC. Albert, Charif, Ismael, Jaouad, Julián, Mahmoud, Moktar, Samir and Zaka know perfectly well how is the lifestyle in prison. They are between 18 and 23 years old and they are prisoners at the “Centre Penitenciari de jovenes de Catalunya”. They are the eight participants of the first edition of Visual Creation Classroom (VCC): In a period of seven months, they learnt how to use photography as a way of storytelling. The VCC intends to be a way to improve the social life amongst youngsters in prison as well as an improvement of their educational process..

ACV. VCC. Albert, Charif, Ismael, Jaouad, Julián, Mahmoud, Moktar, Samir and Zaka know perfectly well how is the lifestyle in prison. They are between 18 and 23 years old and they are prisoners at the “Centre Penitenciari de jovenes de Catalunya”. They are the eight participants of the first edition of Visual Creation Classroom (VCC): In a period of seven months, they learnt how to use photography as a way of storytelling. The VCC intends to be a way to improve the social life amongst youngsters in prison as well as an improvement of their educational process.. Ruido Photo (Barcelona, Spain, 2004) is an organization dedicated to produce and transmit documentary photography regarding Human Rights violations and major social issues. It gathers photographers, journalists and designers, who consider documentary as a tool for reflection and social transformation. It is a platform that opens its doors to receive independent documentary with strong social content and cultural commitment. It operates on four continents and focuses on three interrelated areas: Research and documentation; training and diffusion, and community revitalization practices.

Ruido Photo (Barcelona, Spain, 2004) is an organization dedicated to produce and transmit documentary photography regarding Human Rights violations and major social issues. It gathers photographers, journalists and designers, who consider documentary as a tool for reflection and social transformation. It is a platform that opens its doors to receive independent documentary with strong social content and cultural commitment. It operates on four continents and focuses on three interrelated areas: Research and documentation; training and diffusion, and community revitalization practices.The next photos and videos are the result of leaving a photo and a video camera on the top of a table while making the 12x12. Migration and Jails project. Any resident who had some free time and felt like documenting his surroundings, could grab a camera and feel free to do it without any kind of pretension.

The result is these images that illustrate some moments of the creation process inside a prison. In a makeshift photography set, inside the only casually empty room of the Catalunya Youth Prison school, prisoners themselves decided to create a psychological portrait series of residents that had different geographical roots to show that almost 90% of them were migrants.

HHamza has been for almost three years in Catalunya, he comes from Alger, the capital of Algeria.

"Truth be told, I don’t know how much longer I am going to stay here, it is all up to fate. I could go now or I could stay until… I don’t know, I truly don’t know."

"The thing that made me migrate is that I wanted to change. I wanted to change myself. I was in the wrong path and I wanted to change my ways, my friends, a little of everything because I was in the wrong path. (…) I came here all over from Marsella in train. I went out to the boardwalk and it was a Friday night, everyone was there, there was a party and some other things. I thought to myself “Wow” I thought it was amazing…"

"Of course I would go back to my country but not yet. I’ve got everything in there, family, is my land, my country, and I’ve got to be there. I have to be buried in Argelia, you know?"

Gerson is a youngster from Guatemala City. He started working as a model and interiorist but in order to grow he had to move to another country.

“I left my country because you can’t grow over there, the country is extremely poor and you just can’t. I think here, asking for help, you could get ahead (…) I didn’t come as a migrant because I had all my papers in order, I came here by plane and everything was going just fine, too fine (…) I only miss my family, but one must make sacrifices to get ahead so that is why I’m here.”

“I chose Spain because in the United States they keep an eye on migrants and it is harder to be there. My future here is look for a job, seek for ways to improve my life and bring my family here.”

Julian comes from the little city of Dosquebradas, one of the principal industrial core from Colombia.

“The truth is that the place where I come from is very dangerous, I kept myself involved in odd things and they were going to kill me. That’s why I moved here (…) I have been in Catalunya for two or three years and a year and a half locked. I do not know how much longer will I stay here. I’ll see what I do once I’m out.”

“Uf! What I remember the most of my country is my people, my family, my brothers and the party. Uy! Is what I remember the most. I would not think it twice, I would go back because all my family is there and danger is gone. I miss Colombia a lot, of course I would go back…”

Mahmoud was born in Dakar, capital of Senegal. He has been in Catalunya for six years.

“I changed of country for many reasons. I though that once I get into Spain I could get some money, help my family, these kind of things (…) I arrived in ship from Mauritania to Tenerife. When I arrived some people took care of me because I was underage, I was 16, and they put me in a youth centre until I was 18. (…) I arrived to Europe to get a job, earn some money to help my family, to change their lives and the hard way they live right now there. That is what I thought…”

“We were 93 people in a ship that wasn’t big. It took us 6 days to get to Tenerife. I had never been in the sea, I continuously kept throwing up and dizzy. There were some people that were on the verge of dying but everyone arrived alive. (…) I though that it was a ship not a canoe. When I paid the money they told me it was a ship and I paid 1200 euros.”

“I saw many people that lived in Europe for 5 yeas and then they went back to my country and they had a house, a car, and then I think: How do these people got the money? I have been 20 years working and I just can’t anything, not even a house. Let’s see how is Europe.”

Ismael was born in the capital of Ecuador, Quito. But he has been in Hospitalet city for nine years.

“My mom took me here when I was little, I didn’t know anything, and now, here I am. (…) Right now I wouldn’t go to my country, if I ever go back is going to be for holidays. I would go back once I’m older, to die there and remain there always.”

“When I arrived here nothing seemed easy. I saw my mother working, working quite a lot, and she still does it. And no, as a child I didn’t see life and street as easy things. (…) I always lived in Hospitalet, my neighborhood was very problematic but as every neighborhood it has its good qualities. (…) I remember myself being at school and they picked up someone and started throwing bottles to him, he couldn’t go further from the entrance door, everyone was throwing bottles to him from there…”

Yassine doesn’t speak Spanish. He has only been in Catalunya for three months. His story of how life took him to Europe is the most singular story we found in this project.

Everyone calls him Sáhara. He was born in Dajla, the capital of a province of an old Spanish cologne of the Western Sahara. Today it is occupied by Morocco.

Against his willing, when Yassine was 15 years old, he went to Morocco to do his higher studies, but his support to the Sahara’s independence generate him a series of troubles with the authorities and was locked for 8 months in a Moroccan jail. When he finally achieved his freedom, his family did everything they could to expel him from the country until get, previously paid, a fake visa to go to Europe.

Romeo is Dominican but almost his entire life he has been in Spain.

“I came here when I was eight years old. I couldn’t decide where to go, my mother brought me. I have been here in Catalunya for 11 years, and the truth is, I didn’t think about the time I was going to stay…”

“I miss my entire country, specially the food. Rice with bandule, coco milk and cutlet… or the “Dominican flag”, rice with beans and meat (…)In the Dominican Republic, there are some people that have almost no money; and there are some others that have a great, great time.”

Edwin came to Spain for holidays in 2001. He came to visit his mother and never went back to Colombia.

“I was born in Colombia. My parents came to Spain when I was little and that is the reason I came (…) I thought that Spain was bigger, richer. It wasn’t heaven, but when you arrive here everything is different, you know?, You have to get used to a new culture, a new way of living. Everything is stranger but little by little you adapt yourself. (…) Colombia is very poor but the people are happier and fine with the things they have, they are very humble.”

“Too many deaths, it is not known when this is going to end. It is an intern conflict of the country, between the same Colombians. There is warfare, the drug dealing war, the war between hired assassins; there are too many wars that are never over. It’s one of the most unsafe countries in the world, although it’s a beautiful country, I would ask anybody that hasn’t ever been there to visit it.”

“The presidents of my country are not quite… correct. They are all corrupt. So, it is very difficult to have justice when all the politicians are the same.”

“I don’t know, for example, here you just hear a fire gun, pof! And that’s it. In Colombia when people listen to a fire gun they know someone has been shooted. They just know someone is dead, you understand?”

Samir went out from Alger, the biggest port in the north of Africa, almost ten years ago.

“I came inside of a van inside a ship. I arrived to Almería, I was a kid, and I got myself into of a youth centre and from there I have been in the same sort of places, youth centers (…) This country had a funny smell, seriously, nothing bad but weird, different than where I come from.”

“The memories I have are from when I was a little boy and I played with my friends of the neighborhood, my family (…) With some time I would definitely go back because it is my country, it is where I was born, where I have everything, where my people are. But not yet. I haven’t fixed my life here nor there, so, not until that happens. I have come here to do that, to create a life. I arrived when I was young and now it’s time for work. That is what I want.”

Andres abandoned Colombia when he was 10 years old. His last 10 years he has been in Catalunya.

“Well, I came here because of my mother; she had been here for about for years. She told me that life was going to… That life was going to be way better and that I would study and have everything I wanted, that I was going to have a much better future because the best things were here.”

“I miss everything. My family, the parties, the food, the women, the beaches. A little bit of everything. The culture and the atmosphere there is more cheerful.”

Albert is a 21-year-old prisoner born in Maresme, Premiá de Mar.

“I love my people. They will always help you. If you go to other places people don’t like this. (...) Ugh, my life there was a drift, I spent all day smoking and smoking... I wouldn’t stop from smoking and it was going out, but it was fantastic.”

“We would gather all in my house. Sometimes we were between 15 and 20 people in a room playing on the console and smoking. One day my father came and said: "What is this, a brothel or what?!" Everybody out! When people began to leave, he began to put his hand over the heads of the people and was counting 1 ... 2 ... 3 ... We fucked it big time, but I had a great time.”

“When you leave, you leave ... I will myself into a gardening course or nursing assistant, have a job and can save pennies in order to buy a house in the middle of the mountain. Live there, in the middle of nowhere and forget about people and be quieter.”

Silva was born in the north of Brazil although he was raised in Sao Paulo. He never intended to stay in this country.

“Destiny’s bad. I was to Turkey, well, actually I was going to Japan to give something I had and made a scale in Turkey. Coincidentally, I came here and something went wrong and here I am. Not because I want to, or I wanted to stay in Spain. I’m here due to my bad luck in life.”

“I can’t tell you my impression of Spain because I wasn’t in the street. For the moment, my impression is based on what I’ve seen here in jail. I thought it was very dangerous, like my country’s jails, that people kill each other. And no, totally different, everything is quite relaxed (…) When I arrived to Trinidad I had a problem with a Moroccan and I thought that I had to fight to death with him to gain respect. I had the mentality of my country, you know? And no, they just locked us into our cells and that was it. Very different from my country. I got into jail when I was 17 in a Youth Center and in my first fight they stabbed me. Then I did it back to gain respect. I had been there for only five months and I got stabbed, I blacked out and they took me to the nursery. All in five months!”

“You always go back from where you came from. It is clear; I’ve got a long way back, that is why I have to go back to my family, to my roots.”

According to official data, 75% of the prisoners inside Catalunya Youth jail are migrants from outside of Europe. The other 25%, half are Europeans from outside the EU. Therefore, we found an overwhelming data in the Catalunya Youth jail: the 87.5 % of the prisoners are foreigners, coincidentally, the group with the less economical resources of our society.

These images have no author. It is almost impossible to know who is the creator of each and every 6cm x 6cm negative. The process where the 12 photography sessions in which these images were made, from the outside may appear as a great chaos. Photographers took turns behind the Bronica camera, took two or three shots of prisoners with different backgrounds, and few seconds later a new eye appeared behind the lens. The rest of the group measured light, focused the lens, or gave posing ideas to the model. The session was over once the reel was full.

Making a portrait of half format project does no intend to be an exact replica of the Multiculturalism behind the walls of these jails. This project was just an excuse to join the youngsters from different roots in an improvised photography set and talk. Talk about their history, their journeys, their memories, and their lands. Testimonies that teach us that the world is not necessarily black and white, that there is no good or bad, and that luckily everything is more complex.

ACV. VCC. Albert, Charif, Ismael, Jaouad, Julián, Mahmoud, Moktar, Samir and Zaka know perfectly well how is the lifestyle in prison. They are between 18 and 23 years old and they are prisoners at the “Centre Penitenciari de jovenes de Catalunya”. They are the eight participants of the first edition of Visual Creation Classroom (VCC): In a period of seven months, they learnt how to use photography as a way of storytelling. The VCC intends to be a way to improve the social life amongst youngsters in prison as well as an improvement of their educational process..

ACV. VCC. Albert, Charif, Ismael, Jaouad, Julián, Mahmoud, Moktar, Samir and Zaka know perfectly well how is the lifestyle in prison. They are between 18 and 23 years old and they are prisoners at the “Centre Penitenciari de jovenes de Catalunya”. They are the eight participants of the first edition of Visual Creation Classroom (VCC): In a period of seven months, they learnt how to use photography as a way of storytelling. The VCC intends to be a way to improve the social life amongst youngsters in prison as well as an improvement of their educational process.. Ruido Photo (Barcelona, Spain, 2004) is an organization dedicated to produce and transmit documentary photography regarding Human Rights violations and major social issues. It gathers photographers, journalists and designers, who consider documentary as a tool for reflection and social transformation. It is a platform that opens its doors to receive independent documentary with strong social content and cultural commitment. It operates on four continents and focuses on three interrelated areas: Research and documentation; training and diffusion, and community revitalization practices.

Ruido Photo (Barcelona, Spain, 2004) is an organization dedicated to produce and transmit documentary photography regarding Human Rights violations and major social issues. It gathers photographers, journalists and designers, who consider documentary as a tool for reflection and social transformation. It is a platform that opens its doors to receive independent documentary with strong social content and cultural commitment. It operates on four continents and focuses on three interrelated areas: Research and documentation; training and diffusion, and community revitalization practices.The next photos and videos are the result of leaving a photo and a video camera on the top of a table while making the 12x12. Migration and Jails project. Any resident who had some free time and felt like documenting his surroundings, could grab a camera and feel free to do it without any kind of pretension.

The result is these images that illustrate some moments of the creation process inside a prison. In a makeshift photography set, inside the only casually empty room of the Catalunya Youth Prison school, prisoners themselves decided to create a psychological portrait series of residents that had different geographical roots to show that almost 90% of them were migrants.

Felipe Mejías López

Penitents of the brotherhood of Sorrows, posing with the image of the Virgin during the Easter Week in Aspe (Spain).

March 1929. (Photographer unknown. About photograhy Felipe Mejías, March 2015).

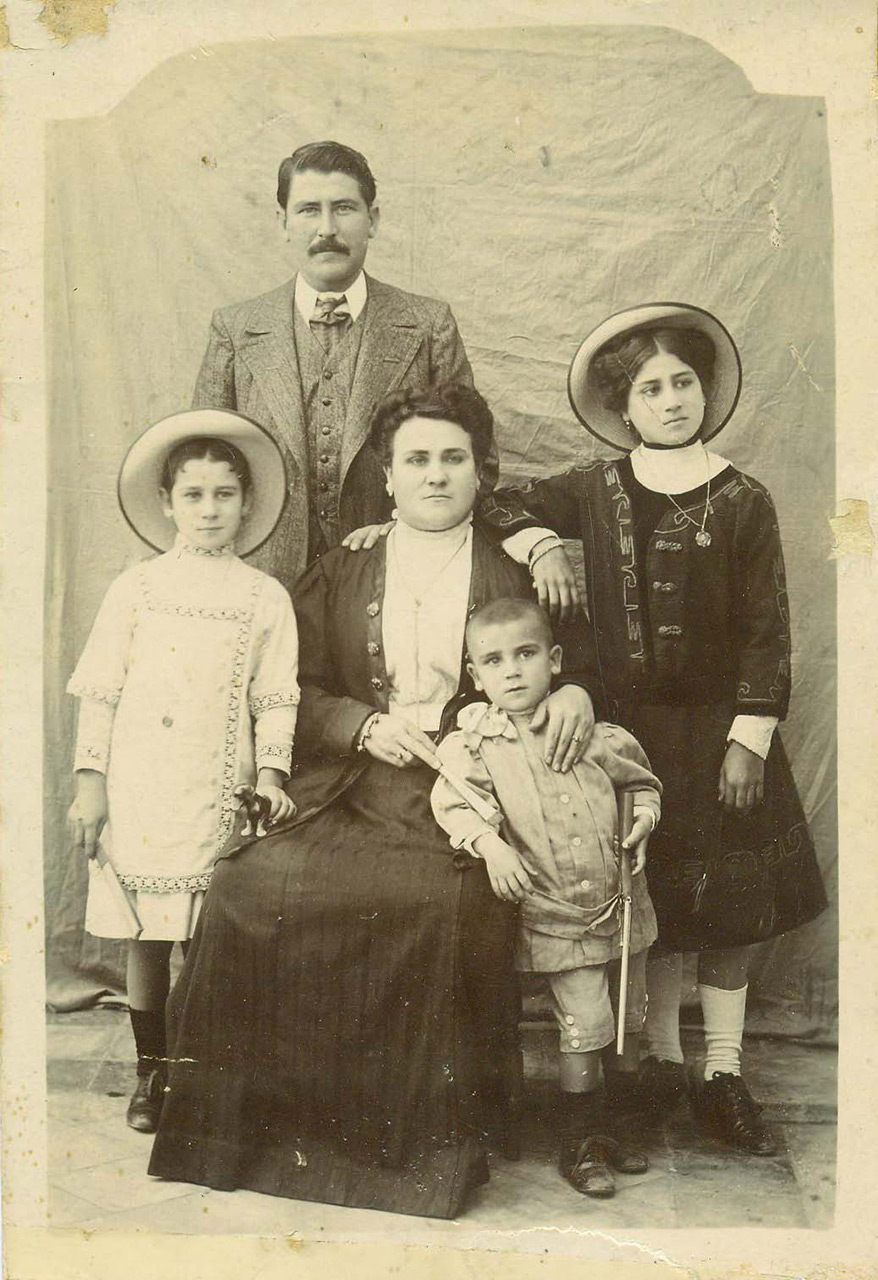

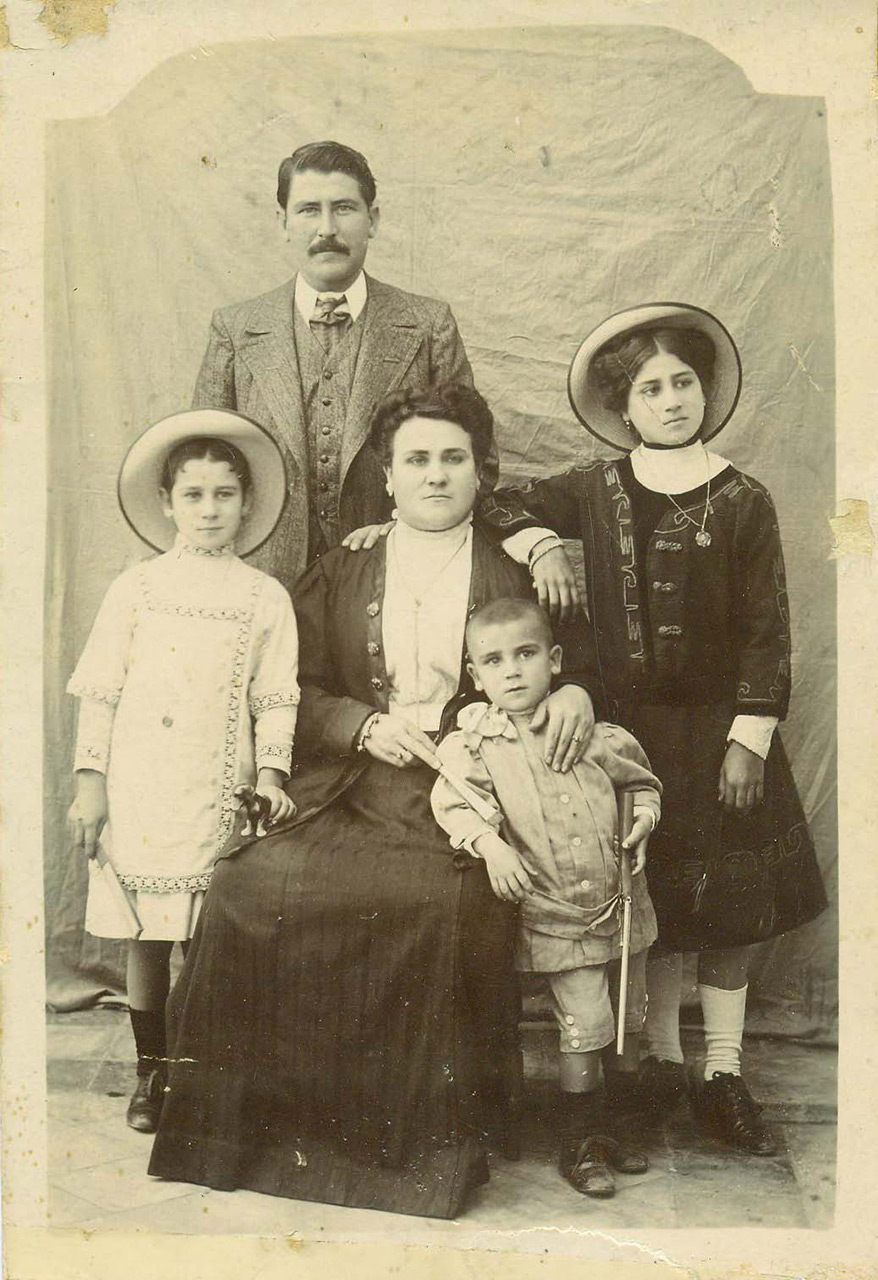

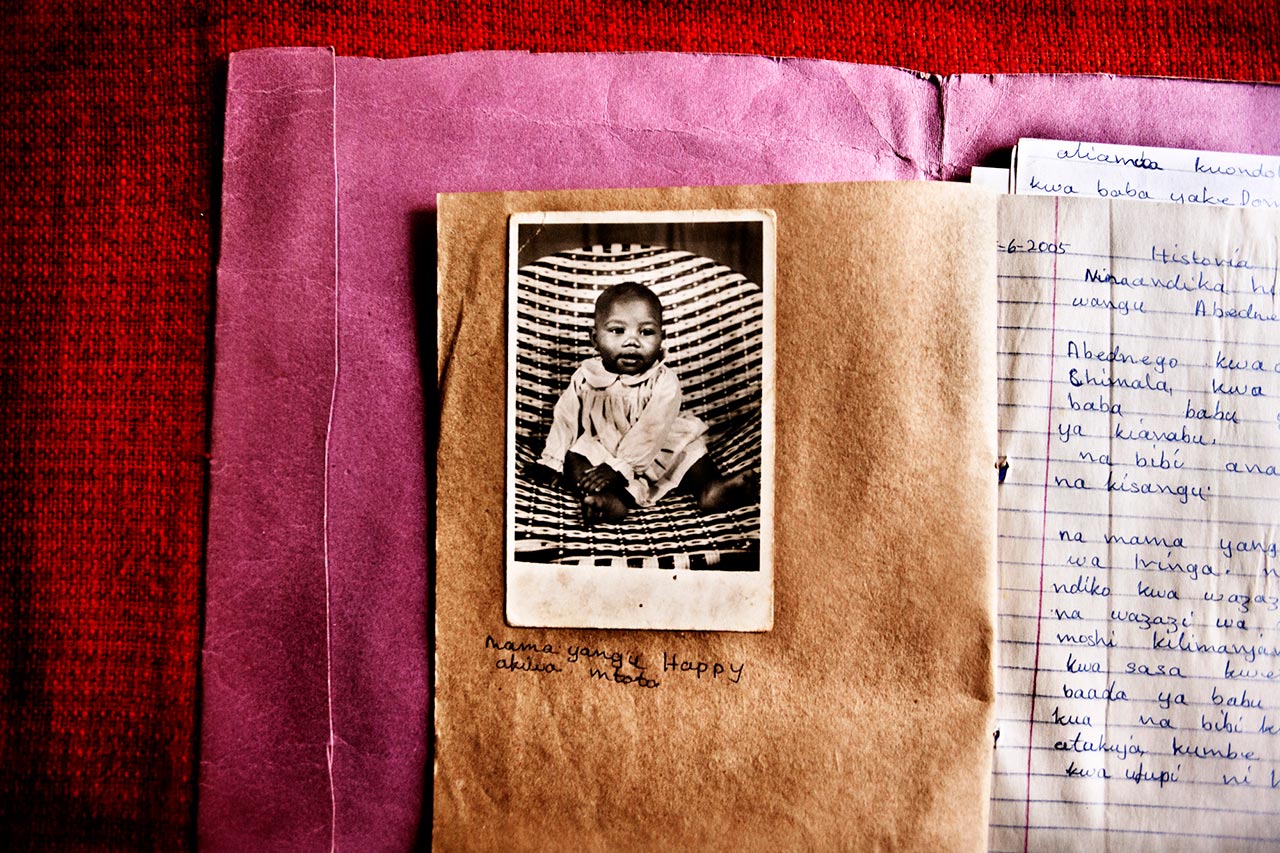

Paper memories. Photographs will always be paper memories, despite the fact that the emergence of digital technology in the world of images has changed the way they are stored. In any case, whether they are stuck in an album, crammed into an old biscuit tin, or stored in a virtual folder tucked away in the darkest corner of our computer’s hard drive, the construction of our memories owes a great deal to these images in black and white or faded colors. We can often reconstruct the exact layout of a place we have been, or feel the gaze of a friend or family member we no longer see because we can re-encounter them when we contemplate these square cardboard remnants. Memory cards and smart phones belong to a different visual universe that has no history but is a slave to the future, subject to a dictatorship that imposes the objective of immediacy and the compulsive desire to devour the overwhelming reality that surrounds us as if it might suddenly and permanently disappear from one moment to the next.

Photographs take us back to what we once were, in a constant, palpable, evident graphic salvation that is fed by our gaze like a fossil into which we breathe life simply by contemplating it. Looking at photos makes us grow, whether or not we want to, because we end up recognizing ourselves in them, somehow transformed into strangers we find it increasingly difficult to recognize: yet, there we are, participating like enthusiastic actors or perhaps behind the viewfinder snapping a photo. This tangible, visual certainty, together with the awareness that time has passed because we remember, creates an incredibly strong sensory cement that binds and gives meaning to our life stories.

But if we broaden the focus and think about our innumerable private –and therefore secret– photographs as a whole that have been collected since the beginning of photography, scattered throughout our immediate environment (not only in our family or neighborhood, but also throughout the macro scale of the city or region where we live), then these images evolve from more than a repertoire of personal memories to cultural objects. And as such, because of the historical, anthropological and ethnological information they contain, these photographs become unique, inimitable objects that deserve to be compiled, studied and published, in the same way we would share material found at an archeological dig or written documents from an historical archive.

Finally, those of us who work with this type of image consider it an act of social justice to return them to the community that produced them, that truly owns them. However, we return something that has been enriched by the hierarchy newly acquired through the transformation of these images into an object of knowledge and study, a sort of cultural heritage, so to speak. Thus these images become the graphic and sentimental memory of a collective whose cohesion is reinforced by their existence.

Initiatives of this type exist everywhere, although they do not always manage to develop the full potential stored within old photographs. The formation of multidisciplinary work teams that include historians and ethnographers familiar with local intra-history could be the key to successfully publishing work that would otherwise be converted into mere catalogs of orphaned images, macabre galleries exhibiting, as if embalmed, anonymous, unknown, dead people. Mere fetishes.

A small example of a local publication using old photographs as axial argument, which we think has achieved satisfactory results, is the project titled Recovered Memories. Photography and Society in Aspe 1870-1976. Field work begun in 1996 and still ongoing, has discovered and documented almost 4,000 images that have been recovered and selected from the private photographic repertoire generated by a small, southeastern Spanish urban community for over a century. The photographs have been classified into 24 different thematic categories that do not lost sight of the transversality of the contents that emerge from the photographs, which are teeming with sociological, anthropological and historical information.

Nazarenes, carrying the cross on their shoulders during the morning procession on Good Friday in Aspe (Spain).

(Photographer unknown, around 1955/Felipe Mejías, March 2015).

From an historian or archeologist’s point of view, it would have been unforgiveable not to try to find new ways to learn about the past with such valuable resources at hand. This is the point where rephotography begins.

It comes as no surprise to find that there are already masters of this relatively young discipline. However, there are only two things you can do with the work of Mark Klett and Camilo José Vergara watch and learn. Sergey Larenkov, Ricard Martínez, Hebe Robinson, Irina Werning, Gustavo Germano and Douglas Levere also produce work that comes very close to visual poetry. Many of them also enter the realm of social and political denunciation, making it quite clear that rephotography is not only a form of technical and aesthetic entertainment, but also a tool that helps us stop and reflect on the collateral damage associated with the passage of time.

But why rephotography? For someone who constantly thinks about the consequences and meaning of the passage of time, it is particularly gratifying to intervene in the process of creating an unattainable fiction through photography: blending the past and the present into a unique instant, taking on the role of a mischievous god in the age-old quest for immortality. Cernuda used to say: “[...] times are identical / gazes are different [...],” and something of this inspiration lurks beneath the ultimate goal of rephotography, attempting to stop and mix time, perceiving it without its having passed, or rather, perceiving if as if it had not done so. Making time manageable, cyclical and malleable is an heroic, almost obsessive exercise that goes beyond the purely visual mannerist trompe-l’oeil to reveal a little of the artifice behind the deception. The point is to photograph what other eyes before ours saw, in the same place, in the same instant, using the same technique. It is as if we brought the original photographer back to life and had him beside us, whispering the correct focus into our ear. Furthermore, if we do it in the place where we were born and raised, we can sublimate the nostalgic component each rephotograph inevitably contains: being right now where someone was long before us and seeing, touching and smelling the same environment. Feeling the same as that person. Being that person.

Overlapping, contrasting, recreating through transparencies and seeing how the different layers of memory deposited over the years, flourish and contribute to the task of creating the illusion that the old and new images are actually different sides of the same reality. A new discourse about the obvious contrast between the past and present, what is and what is not, is created, runs the risk of getting stuck at the anecdotal level. Even so, it may be enough. Although it is possible to try something else: building an imaginary cage in which to enclose two similar instances separated by time in the hope that they can live together and perhaps end up becoming a single moment. Just like in the Frankenstein myth, we give birth to impossible, two-headed monsters, Siamese twins that must always share different moments of the same existence. We give them a voice, and the possibility of shouting and discovering what is hidden within; their wrinkles, how the space or person has aged; what remains of what they once were. The experiment is not always successful, but it sometimes works and eventually creates a new scene where everything fits together marvelously; shapes continue and intertwine without signaling eras; grays and colors merge into a single light. It is a small miracle fixed in a subtle, crystalline, almost imperceptible balance.

But let us not deceive ourselves. In reality everything is always the past. The unattainable past. We like to think that rephotography gives us the possibility of returning to the past, to rethink it and try to bring it back to life. Poor fools, as if we could bring it back to a time and place it actually never left.

Felipe Mejías López (Spain, 1968). Lives and works in Spain. Historian and archaeologist. BA in Geography and History with a major in Art History from the University of Valencia. MA in Professional Archaeology and Heritage Management from the University of Alicante. A lot of his publications revolve around the archaeological, historical, artistic, documentary and photographic heritage of his native town, Aspe. Currently, he is editing the third volume of his research project on ancient photography and social history Recovered Memories. For this project, he studied the field of rephotography.

Felipe Mejías López (Spain, 1968). Lives and works in Spain. Historian and archaeologist. BA in Geography and History with a major in Art History from the University of Valencia. MA in Professional Archaeology and Heritage Management from the University of Alicante. A lot of his publications revolve around the archaeological, historical, artistic, documentary and photographic heritage of his native town, Aspe. Currently, he is editing the third volume of his research project on ancient photography and social history Recovered Memories. For this project, he studied the field of rephotography.

Penitents of the brotherhood of Sorrows, posing with the image of the Virgin during the Easter Week in Aspe (Spain).

March 1929. (Photographer unknown. About photograhy Felipe Mejías, March 2015).

Paper memories. Photographs will always be paper memories, despite the fact that the emergence of digital technology in the world of images has changed the way they are stored. In any case, whether they are stuck in an album, crammed into an old biscuit tin, or stored in a virtual folder tucked away in the darkest corner of our computer’s hard drive, the construction of our memories owes a great deal to these images in black and white or faded colors. We can often reconstruct the exact layout of a place we have been, or feel the gaze of a friend or family member we no longer see because we can re-encounter them when we contemplate these square cardboard remnants. Memory cards and smart phones belong to a different visual universe that has no history but is a slave to the future, subject to a dictatorship that imposes the objective of immediacy and the compulsive desire to devour the overwhelming reality that surrounds us as if it might suddenly and permanently disappear from one moment to the next.

Photographs take us back to what we once were, in a constant, palpable, evident graphic salvation that is fed by our gaze like a fossil into which we breathe life simply by contemplating it. Looking at photos makes us grow, whether or not we want to, because we end up recognizing ourselves in them, somehow transformed into strangers we find it increasingly difficult to recognize: yet, there we are, participating like enthusiastic actors or perhaps behind the viewfinder snapping a photo. This tangible, visual certainty, together with the awareness that time has passed because we remember, creates an incredibly strong sensory cement that binds and gives meaning to our life stories.

But if we broaden the focus and think about our innumerable private –and therefore secret– photographs as a whole that have been collected since the beginning of photography, scattered throughout our immediate environment (not only in our family or neighborhood, but also throughout the macro scale of the city or region where we live), then these images evolve from more than a repertoire of personal memories to cultural objects. And as such, because of the historical, anthropological and ethnological information they contain, these photographs become unique, inimitable objects that deserve to be compiled, studied and published, in the same way we would share material found at an archeological dig or written documents from an historical archive.

Finally, those of us who work with this type of image consider it an act of social justice to return them to the community that produced them, that truly owns them. However, we return something that has been enriched by the hierarchy newly acquired through the transformation of these images into an object of knowledge and study, a sort of cultural heritage, so to speak. Thus these images become the graphic and sentimental memory of a collective whose cohesion is reinforced by their existence.

Initiatives of this type exist everywhere, although they do not always manage to develop the full potential stored within old photographs. The formation of multidisciplinary work teams that include historians and ethnographers familiar with local intra-history could be the key to successfully publishing work that would otherwise be converted into mere catalogs of orphaned images, macabre galleries exhibiting, as if embalmed, anonymous, unknown, dead people. Mere fetishes.

A small example of a local publication using old photographs as axial argument, which we think has achieved satisfactory results, is the project titled Recovered Memories. Photography and Society in Aspe 1870-1976. Field work begun in 1996 and still ongoing, has discovered and documented almost 4,000 images that have been recovered and selected from the private photographic repertoire generated by a small, southeastern Spanish urban community for over a century. The photographs have been classified into 24 different thematic categories that do not lost sight of the transversality of the contents that emerge from the photographs, which are teeming with sociological, anthropological and historical information.

Nazarenes, carrying the cross on their shoulders during the morning procession on Good Friday in Aspe (Spain).

(Photographer unknown, around 1955/Felipe Mejías, March 2015).

From an historian or archeologist’s point of view, it would have been unforgiveable not to try to find new ways to learn about the past with such valuable resources at hand. This is the point where rephotography begins.

It comes as no surprise to find that there are already masters of this relatively young discipline. However, there are only two things you can do with the work of Mark Klett and Camilo José Vergara watch and learn. Sergey Larenkov, Ricard Martínez, Hebe Robinson, Irina Werning, Gustavo Germano and Douglas Levere also produce work that comes very close to visual poetry. Many of them also enter the realm of social and political denunciation, making it quite clear that rephotography is not only a form of technical and aesthetic entertainment, but also a tool that helps us stop and reflect on the collateral damage associated with the passage of time.

But why rephotography? For someone who constantly thinks about the consequences and meaning of the passage of time, it is particularly gratifying to intervene in the process of creating an unattainable fiction through photography: blending the past and the present into a unique instant, taking on the role of a mischievous god in the age-old quest for immortality. Cernuda used to say: “[...] times are identical / gazes are different [...],” and something of this inspiration lurks beneath the ultimate goal of rephotography, attempting to stop and mix time, perceiving it without its having passed, or rather, perceiving if as if it had not done so. Making time manageable, cyclical and malleable is an heroic, almost obsessive exercise that goes beyond the purely visual mannerist trompe-l’oeil to reveal a little of the artifice behind the deception. The point is to photograph what other eyes before ours saw, in the same place, in the same instant, using the same technique. It is as if we brought the original photographer back to life and had him beside us, whispering the correct focus into our ear. Furthermore, if we do it in the place where we were born and raised, we can sublimate the nostalgic component each rephotograph inevitably contains: being right now where someone was long before us and seeing, touching and smelling the same environment. Feeling the same as that person. Being that person.

Overlapping, contrasting, recreating through transparencies and seeing how the different layers of memory deposited over the years, flourish and contribute to the task of creating the illusion that the old and new images are actually different sides of the same reality. A new discourse about the obvious contrast between the past and present, what is and what is not, is created, runs the risk of getting stuck at the anecdotal level. Even so, it may be enough. Although it is possible to try something else: building an imaginary cage in which to enclose two similar instances separated by time in the hope that they can live together and perhaps end up becoming a single moment. Just like in the Frankenstein myth, we give birth to impossible, two-headed monsters, Siamese twins that must always share different moments of the same existence. We give them a voice, and the possibility of shouting and discovering what is hidden within; their wrinkles, how the space or person has aged; what remains of what they once were. The experiment is not always successful, but it sometimes works and eventually creates a new scene where everything fits together marvelously; shapes continue and intertwine without signaling eras; grays and colors merge into a single light. It is a small miracle fixed in a subtle, crystalline, almost imperceptible balance.

But let us not deceive ourselves. In reality everything is always the past. The unattainable past. We like to think that rephotography gives us the possibility of returning to the past, to rethink it and try to bring it back to life. Poor fools, as if we could bring it back to a time and place it actually never left.

Felipe Mejías López (Spain, 1968). Lives and works in Spain. Historian and archaeologist. BA in Geography and History with a major in Art History from the University of Valencia. MA in Professional Archaeology and Heritage Management from the University of Alicante. A lot of his publications revolve around the archaeological, historical, artistic, documentary and photographic heritage of his native town, Aspe. Currently, he is editing the third volume of his research project on ancient photography and social history Recovered Memories. For this project, he studied the field of rephotography.

Felipe Mejías López (Spain, 1968). Lives and works in Spain. Historian and archaeologist. BA in Geography and History with a major in Art History from the University of Valencia. MA in Professional Archaeology and Heritage Management from the University of Alicante. A lot of his publications revolve around the archaeological, historical, artistic, documentary and photographic heritage of his native town, Aspe. Currently, he is editing the third volume of his research project on ancient photography and social history Recovered Memories. For this project, he studied the field of rephotography.Alvaro Deprit

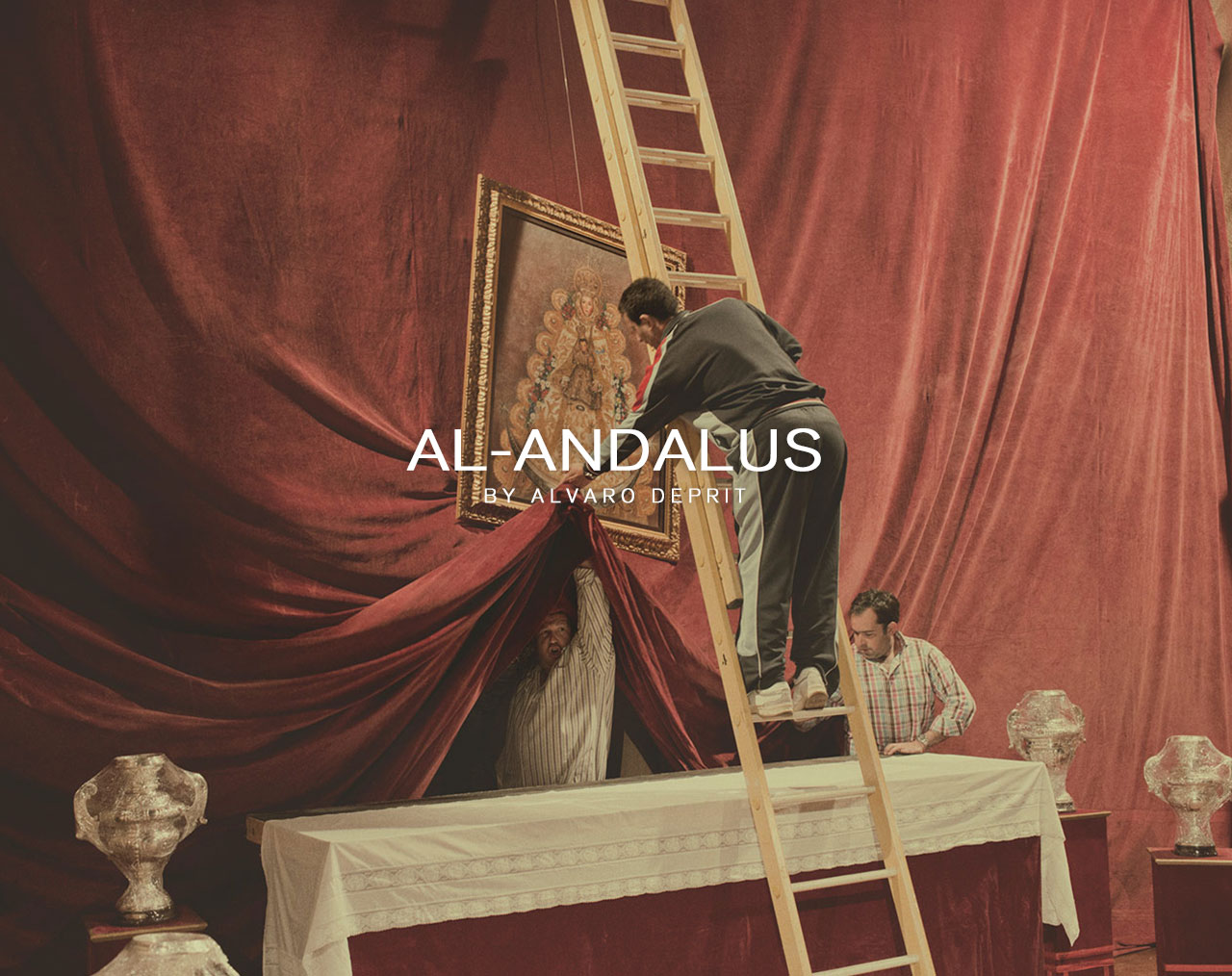

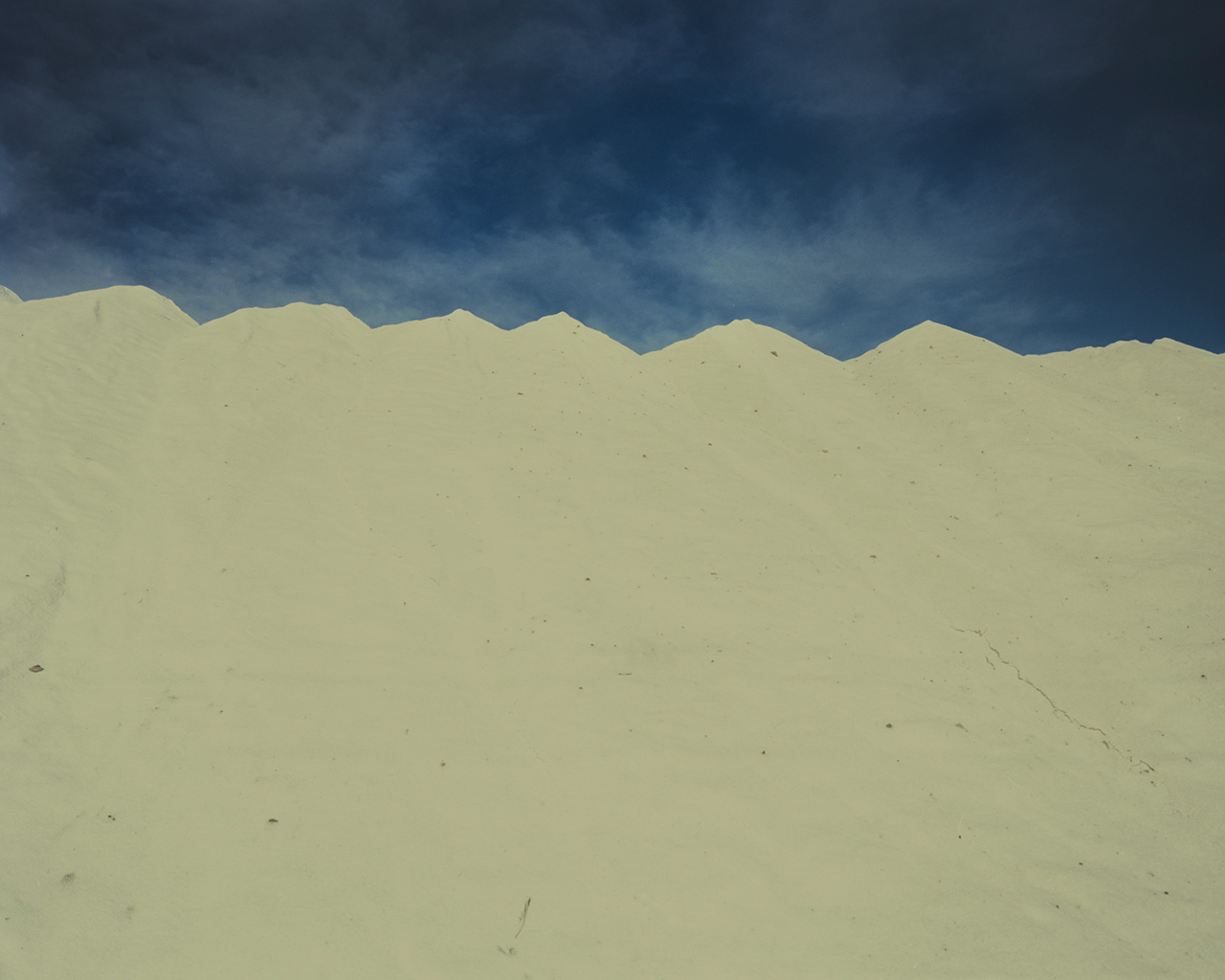

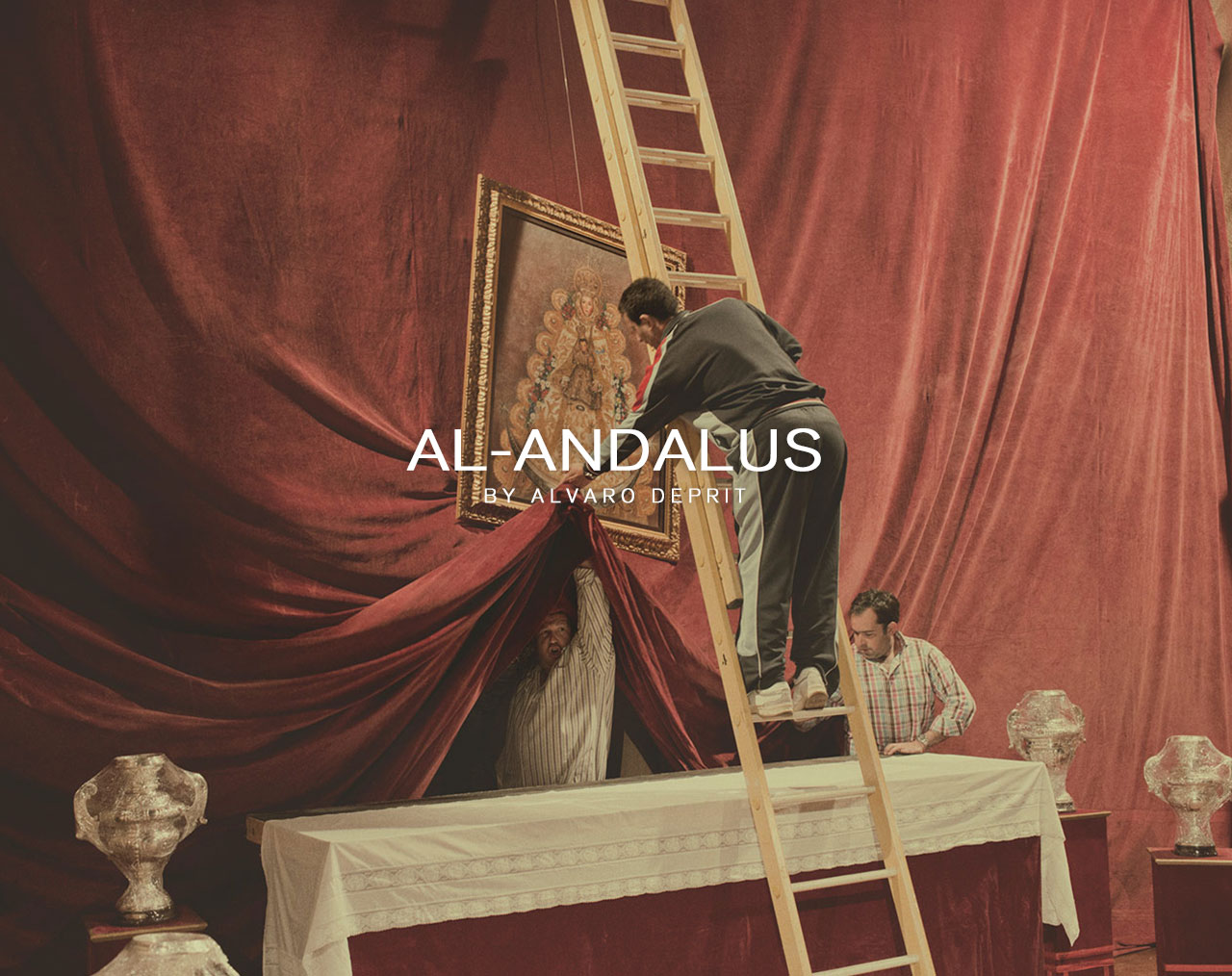

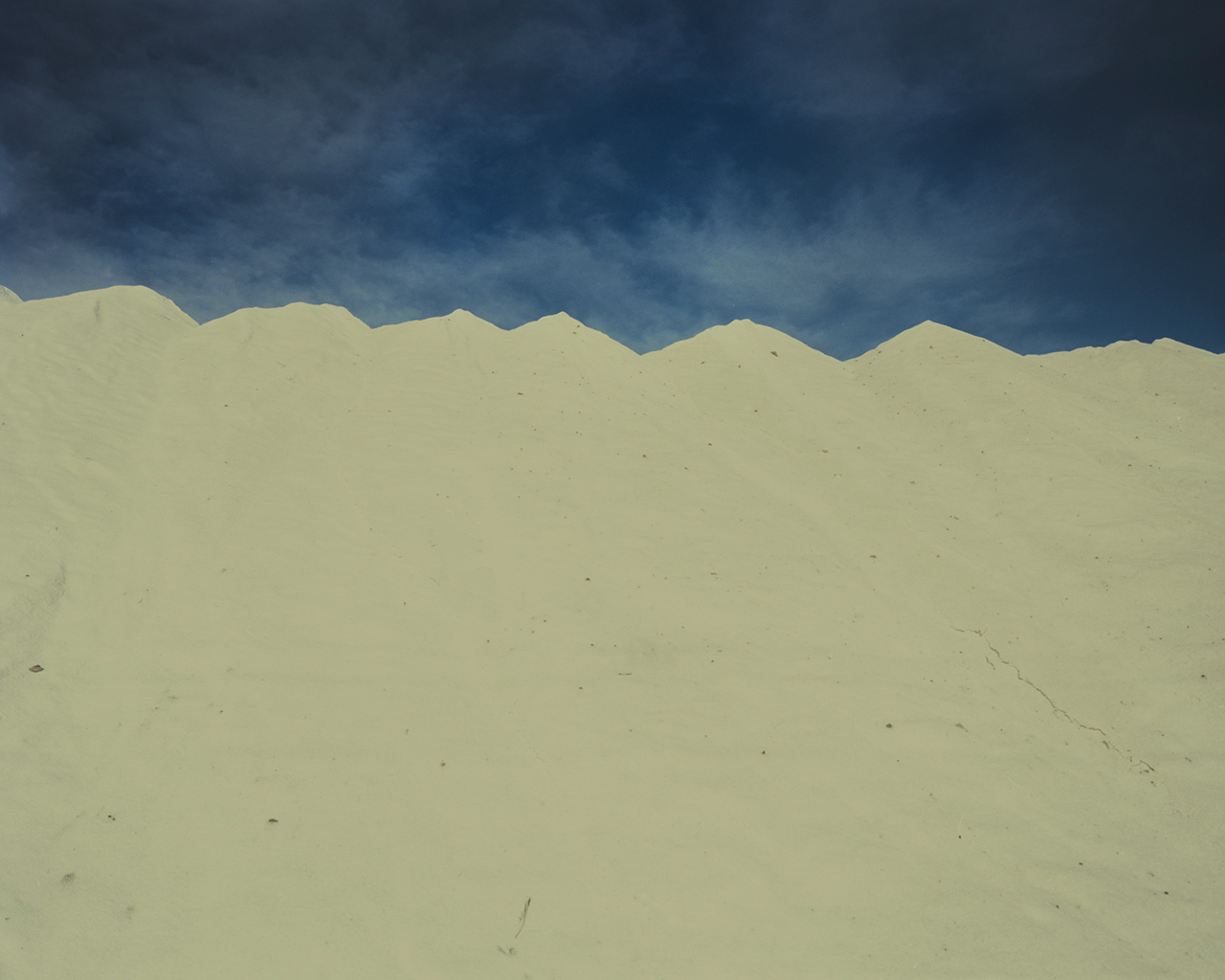

At home I always used to linger with curiosity at an old photograph of some of my Andalusian relatives. With the passing of years this photograph has given me an image of how I think Andalusia might be.

Al-Andalus is the result of approximately three years of research in the south of Spain, an area I did not know nor in which I have lived, but which is my family’s place of origin and current place of residence.

My initial interest was in the tension I perceived between tradition and the marks of the global world. Andalusia is the result of a complex cultural stratification, derived from the passage of civilisations which, over time, gave life to a hybrid identity capable of containing within it the stereotypical traits of Spanish culture.

Journeying through Andalusia now that it has been hit hard by the economic crisis has made me reflect on the collision of the diverse elements in this land – a land which, as I see it, has shown itself to be hanging in the balance, almost in a state between reality and fiction as the background of a movie.

My intention has not been to reproduce the tangible aspects of a place, but to give shape to a body of memories and impressions born of my personal history or of something unconcluded. Concentrated in the images are visible apparitions whose existence is a mystery, while on the other hand, the mystery is something real in the mind, through the repeating, varying, developing and transposing elements of the memory.

Alvaro Deprit (Madrid). Has been living in Italy since 2004. He studied German Philology at the Complutense University of Madrid and at the Otto Friedrich University of Bamberg, Germany. He also studied Sociology at the University d’Annunzio in Chieti, Italy. Alvaro’s work has been exhibited in festivals and galleries all over the world and has been published in international magazines. He won the PHotoEspaña OjodePez Human Values Award, the BJP’s International Photography Award and the Viewbook Photostory Contest, and he was a finalist in Voies Off Arles, Leica Oskar Barnack Award and Sony Award.

Alvaro Deprit (Madrid). Has been living in Italy since 2004. He studied German Philology at the Complutense University of Madrid and at the Otto Friedrich University of Bamberg, Germany. He also studied Sociology at the University d’Annunzio in Chieti, Italy. Alvaro’s work has been exhibited in festivals and galleries all over the world and has been published in international magazines. He won the PHotoEspaña OjodePez Human Values Award, the BJP’s International Photography Award and the Viewbook Photostory Contest, and he was a finalist in Voies Off Arles, Leica Oskar Barnack Award and Sony Award.

At home I always used to linger with curiosity at an old photograph of some of my Andalusian relatives. With the passing of years this photograph has given me an image of how I think Andalusia might be.

Al-Andalus is the result of approximately three years of research in the south of Spain, an area I did not know nor in which I have lived, but which is my family’s place of origin and current place of residence.

My initial interest was in the tension I perceived between tradition and the marks of the global world. Andalusia is the result of a complex cultural stratification, derived from the passage of civilisations which, over time, gave life to a hybrid identity capable of containing within it the stereotypical traits of Spanish culture.

Journeying through Andalusia now that it has been hit hard by the economic crisis has made me reflect on the collision of the diverse elements in this land – a land which, as I see it, has shown itself to be hanging in the balance, almost in a state between reality and fiction as the background of a movie.

My intention has not been to reproduce the tangible aspects of a place, but to give shape to a body of memories and impressions born of my personal history or of something unconcluded. Concentrated in the images are visible apparitions whose existence is a mystery, while on the other hand, the mystery is something real in the mind, through the repeating, varying, developing and transposing elements of the memory.

Alvaro Deprit (Madrid). Has been living in Italy since 2004. He studied German Philology at the Complutense University of Madrid and at the Otto Friedrich University of Bamberg, Germany. He also studied Sociology at the University d’Annunzio in Chieti, Italy. Alvaro’s work has been exhibited in festivals and galleries all over the world and has been published in international magazines. He won the PHotoEspaña OjodePez Human Values Award, the BJP’s International Photography Award and the Viewbook Photostory Contest, and he was a finalist in Voies Off Arles, Leica Oskar Barnack Award and Sony Award.

Alvaro Deprit (Madrid). Has been living in Italy since 2004. He studied German Philology at the Complutense University of Madrid and at the Otto Friedrich University of Bamberg, Germany. He also studied Sociology at the University d’Annunzio in Chieti, Italy. Alvaro’s work has been exhibited in festivals and galleries all over the world and has been published in international magazines. He won the PHotoEspaña OjodePez Human Values Award, the BJP’s International Photography Award and the Viewbook Photostory Contest, and he was a finalist in Voies Off Arles, Leica Oskar Barnack Award and Sony Award.Álvaro Laiz & David Rengel / AnHua

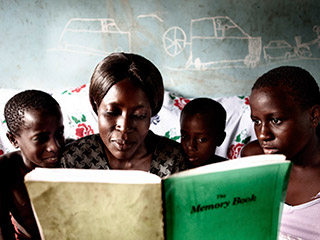

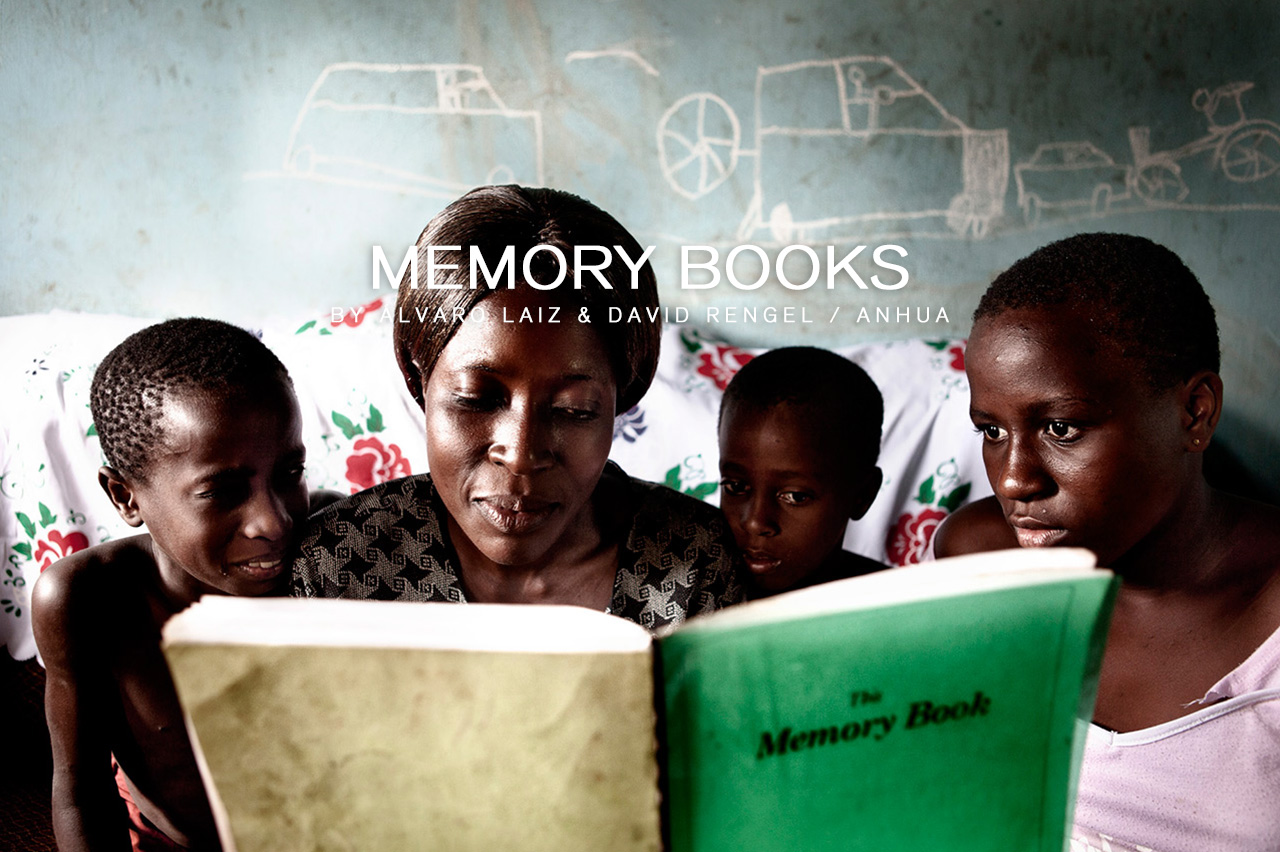

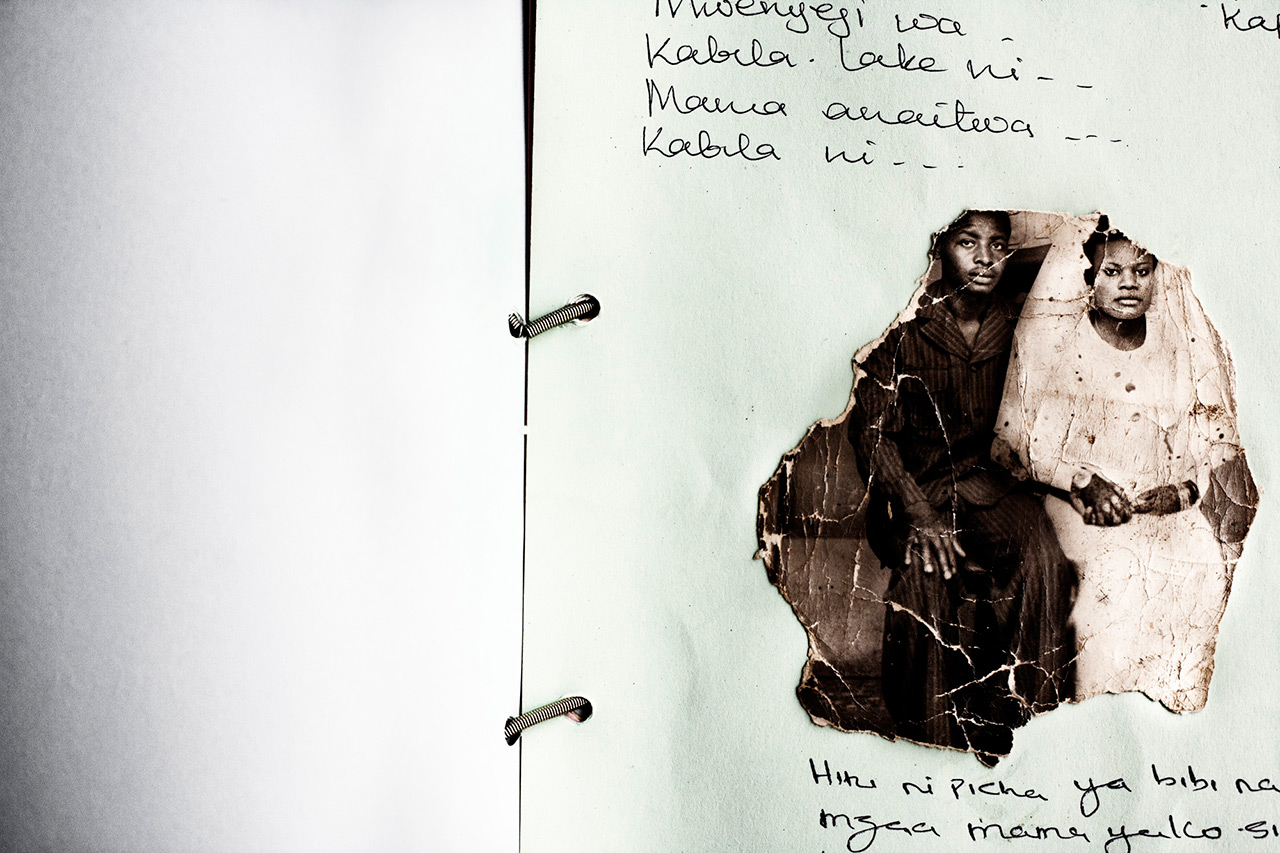

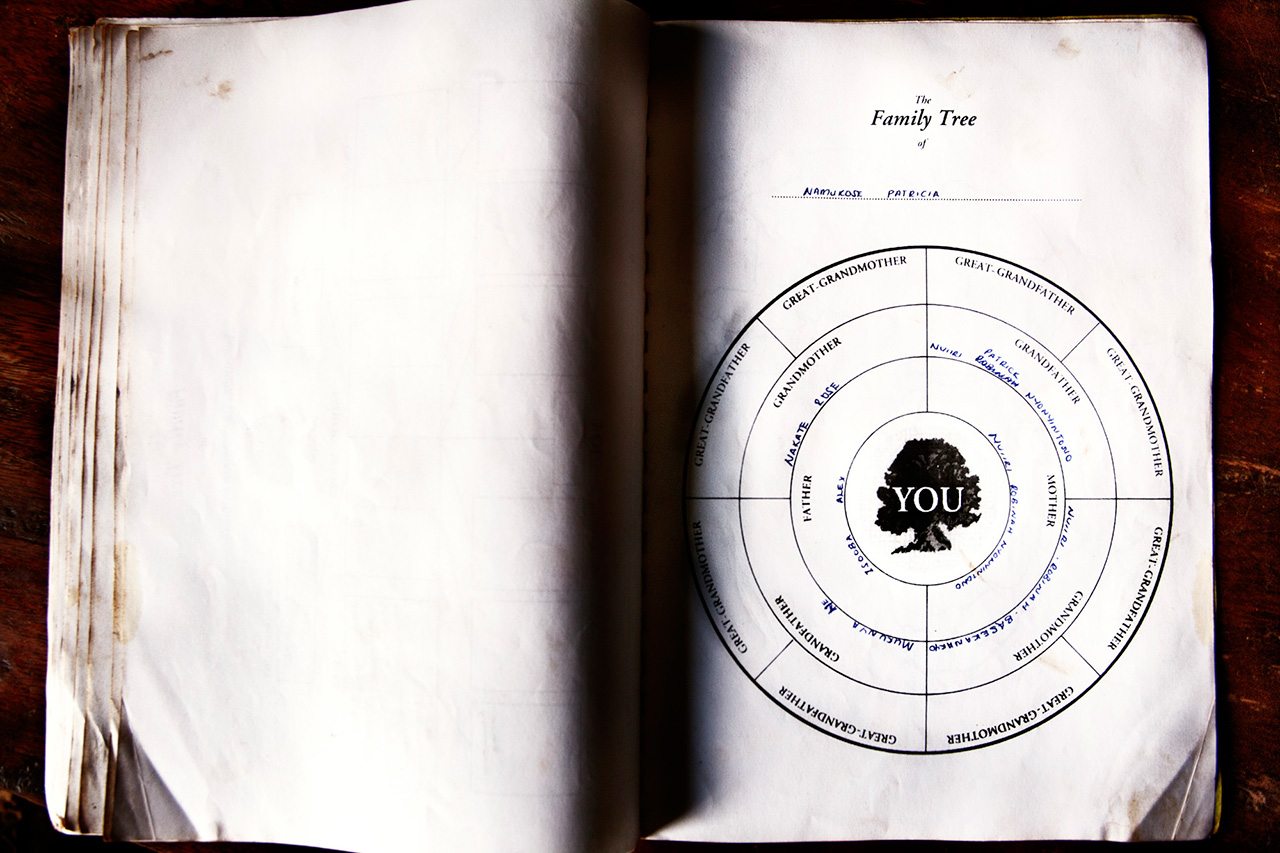

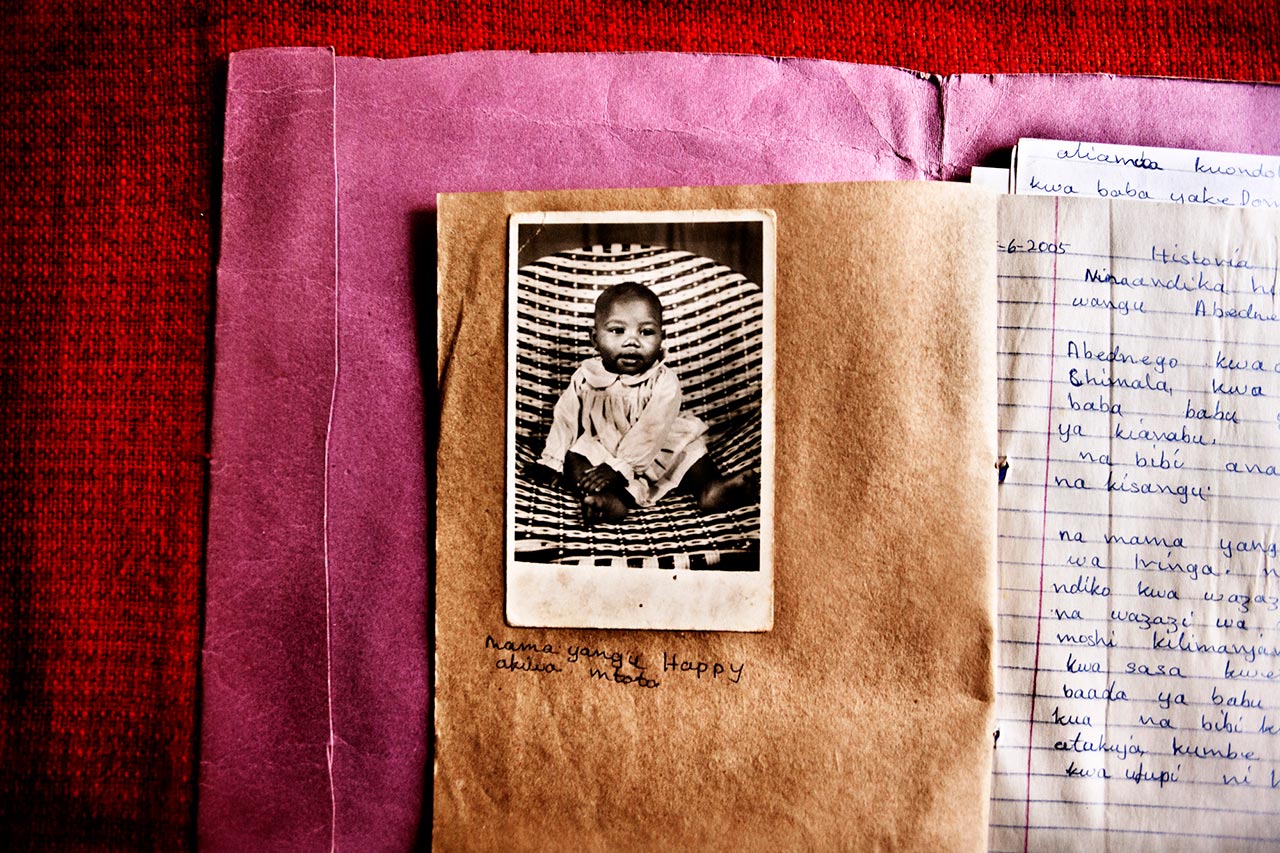

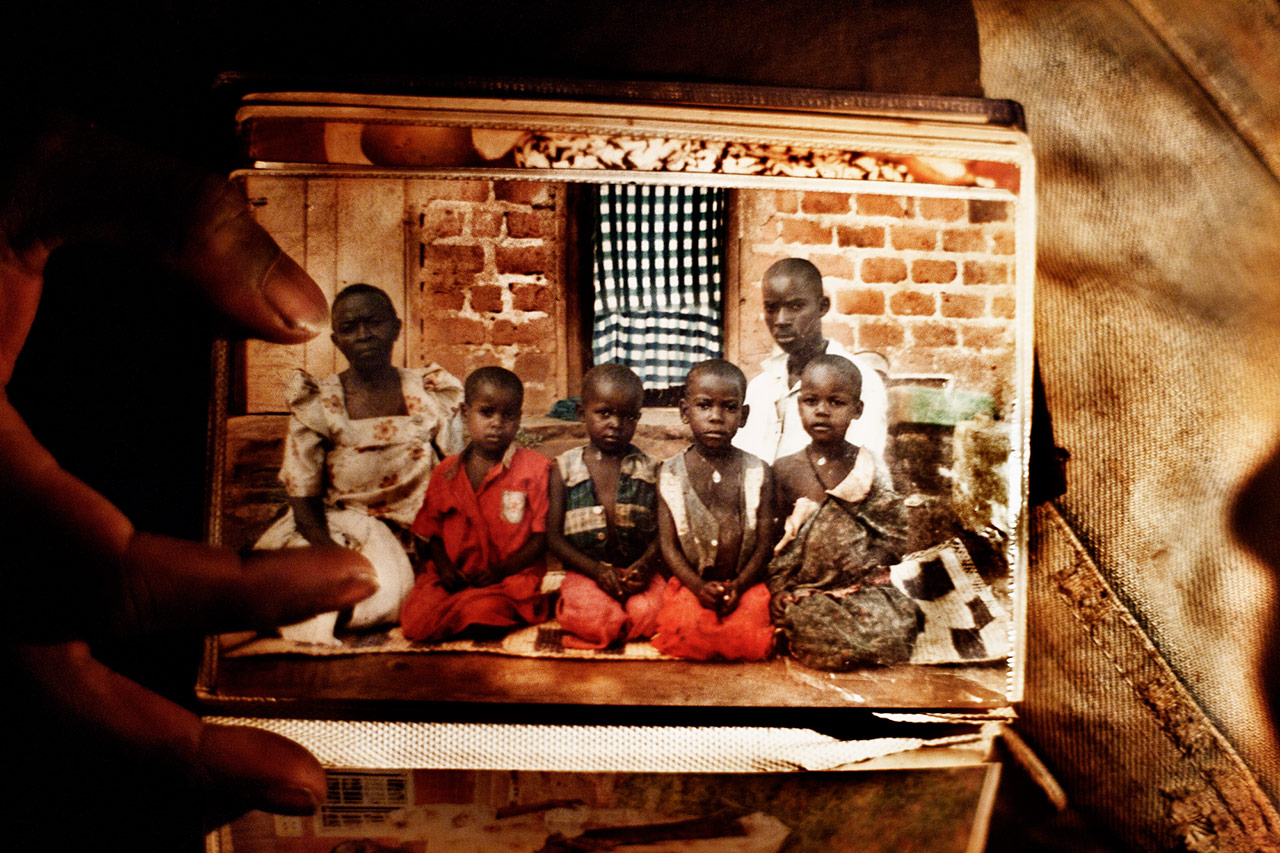

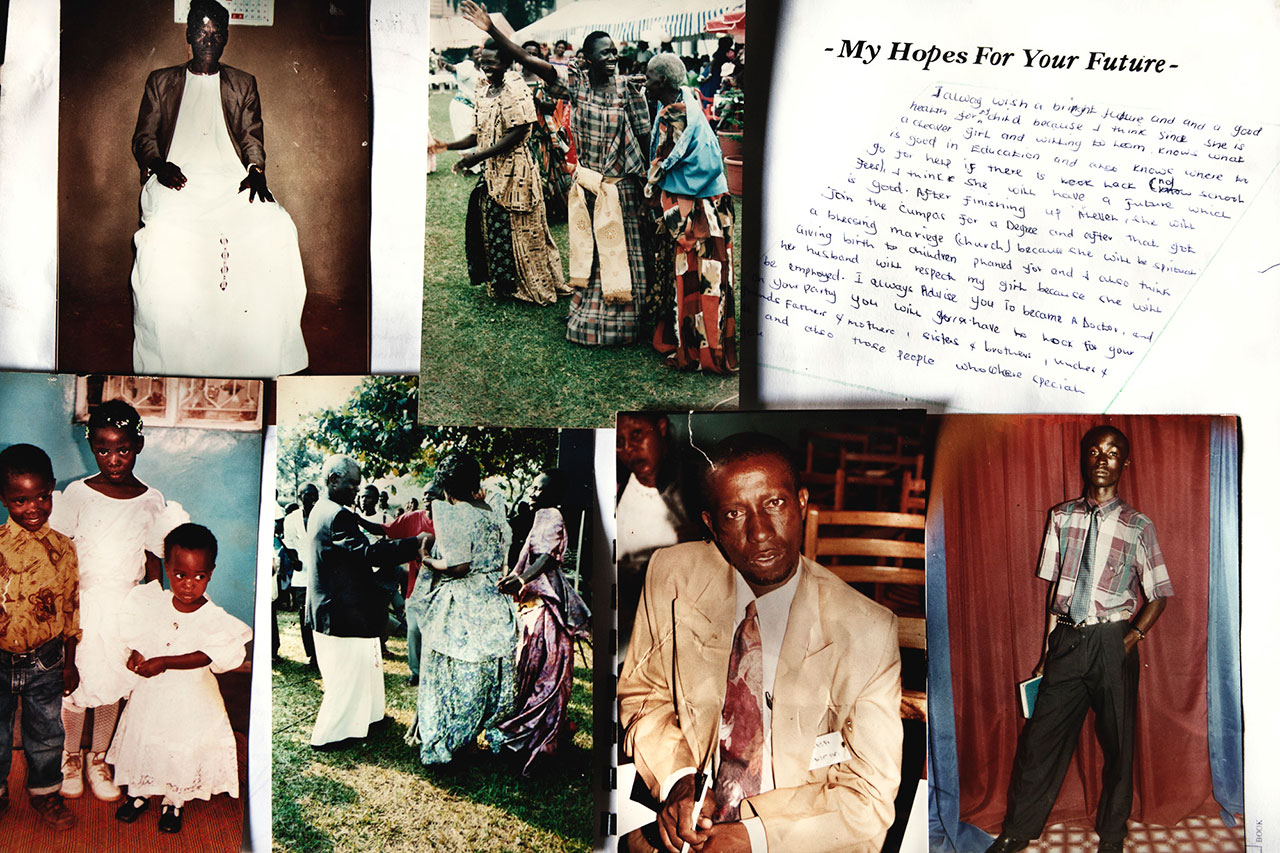

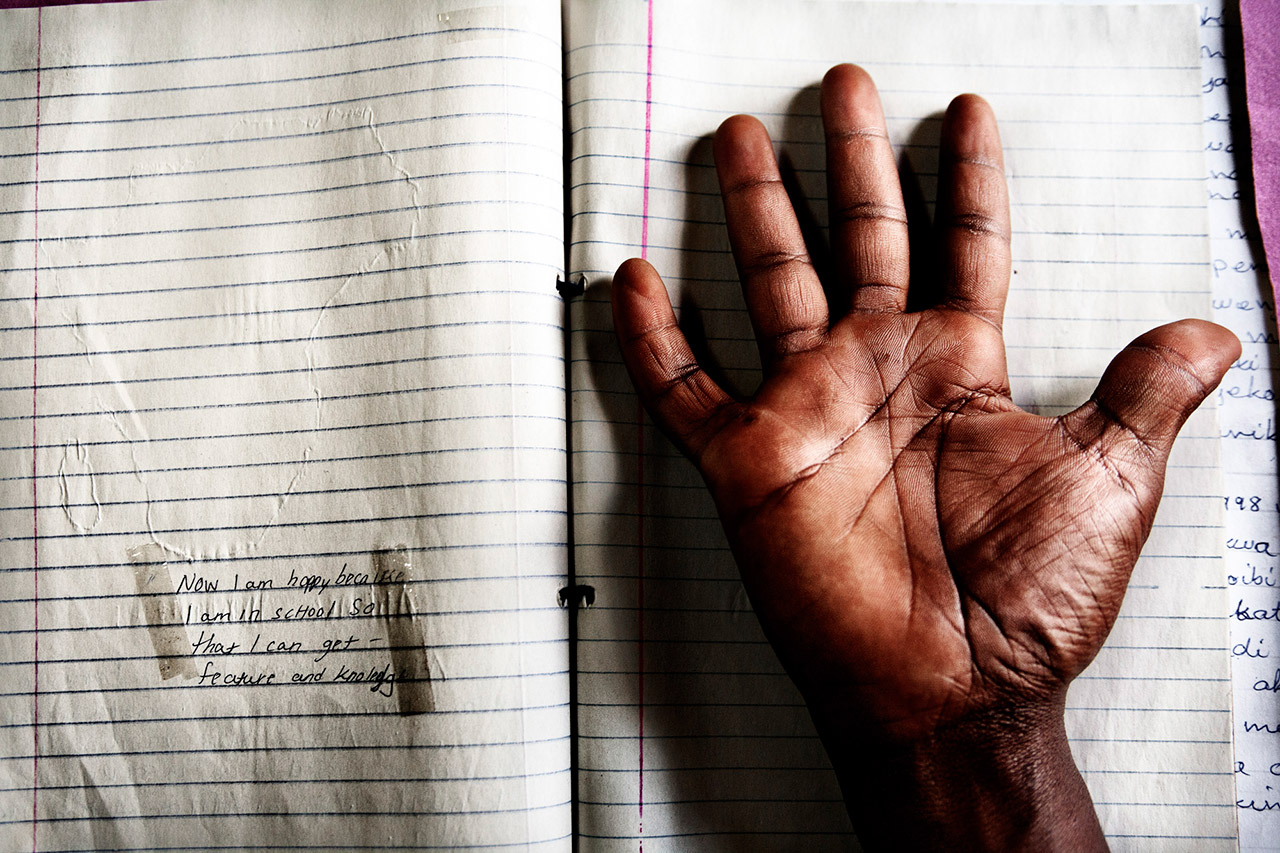

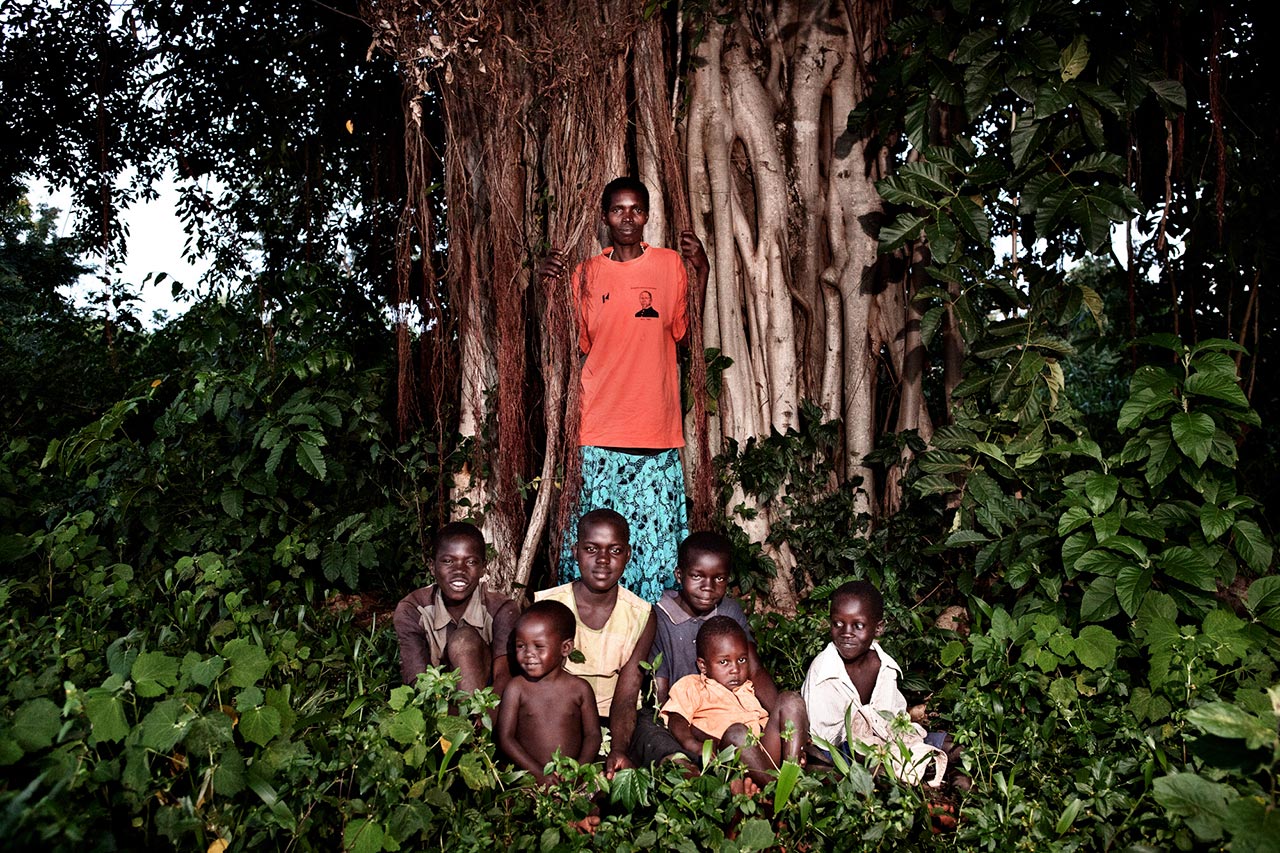

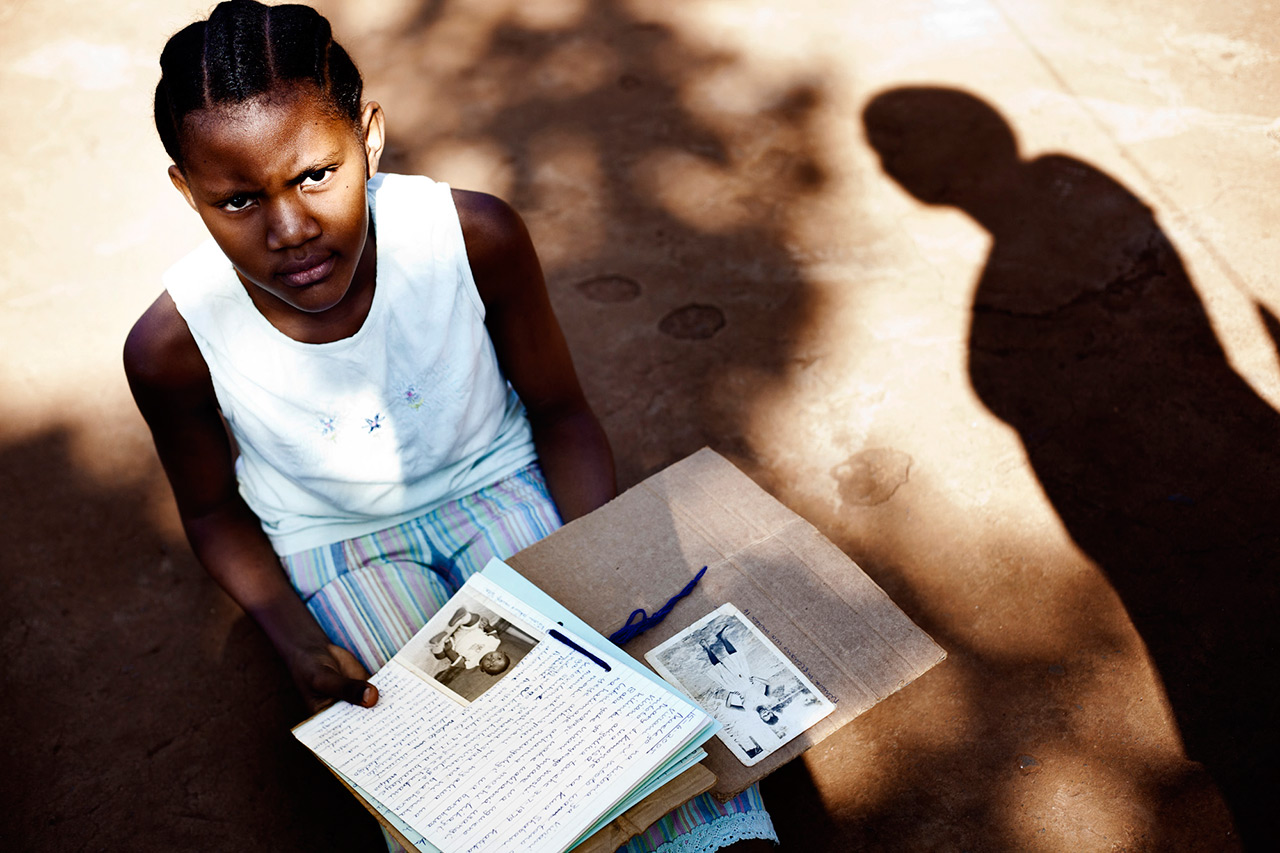

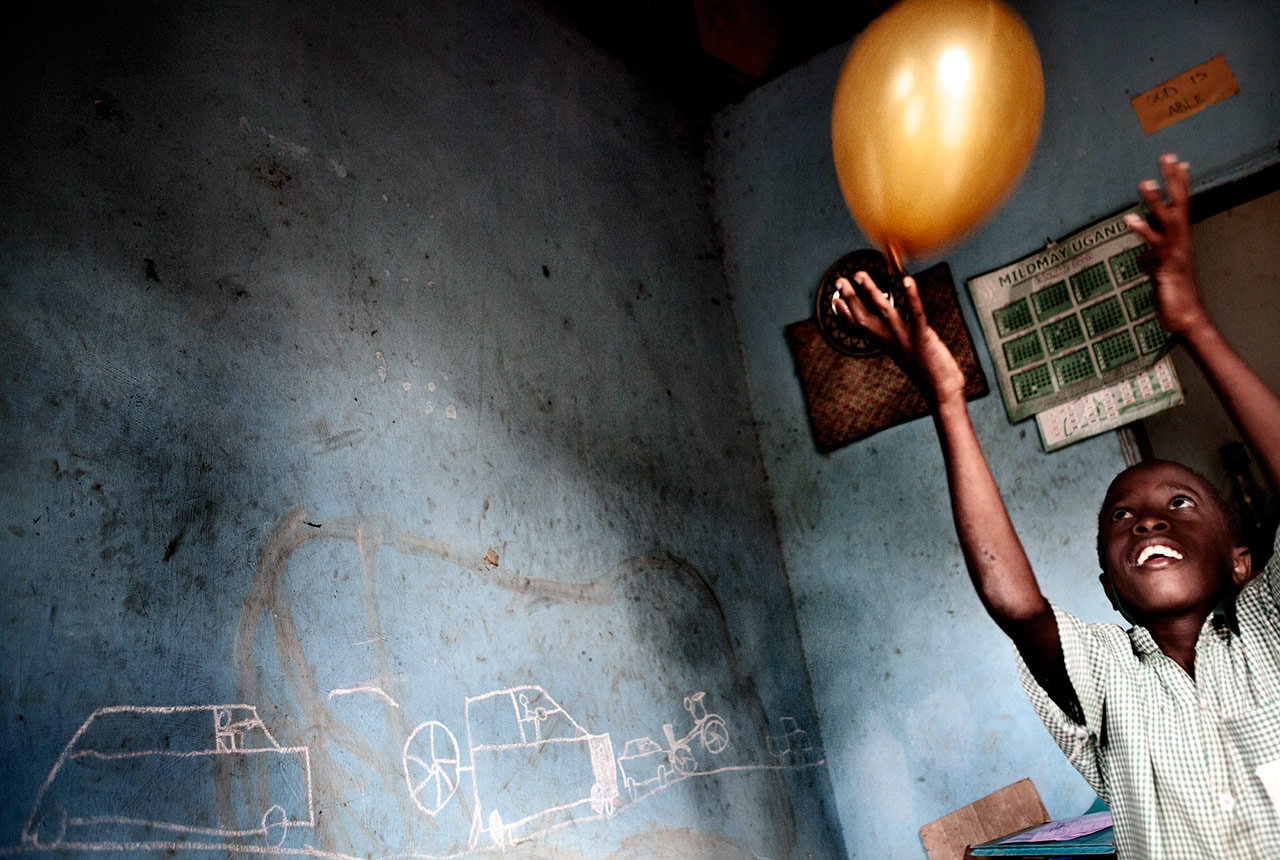

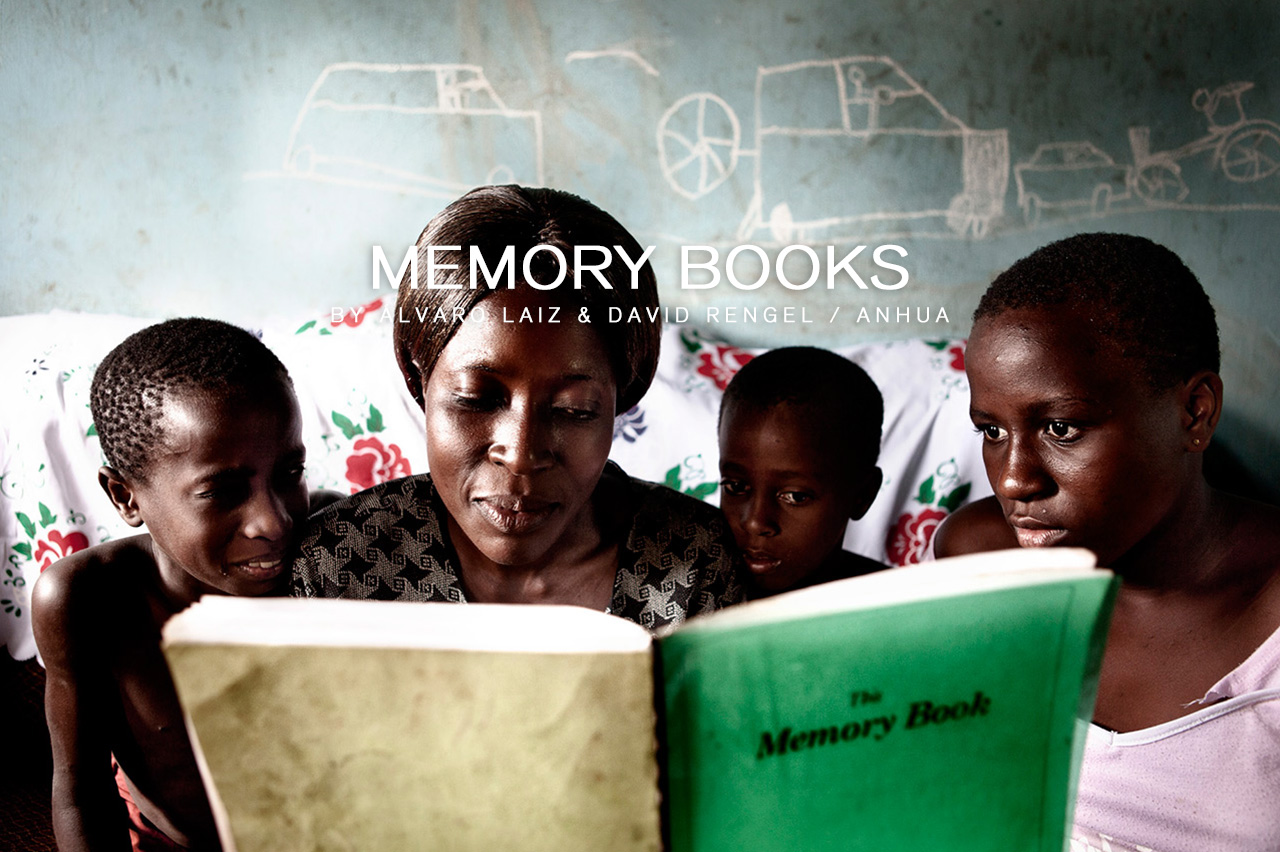

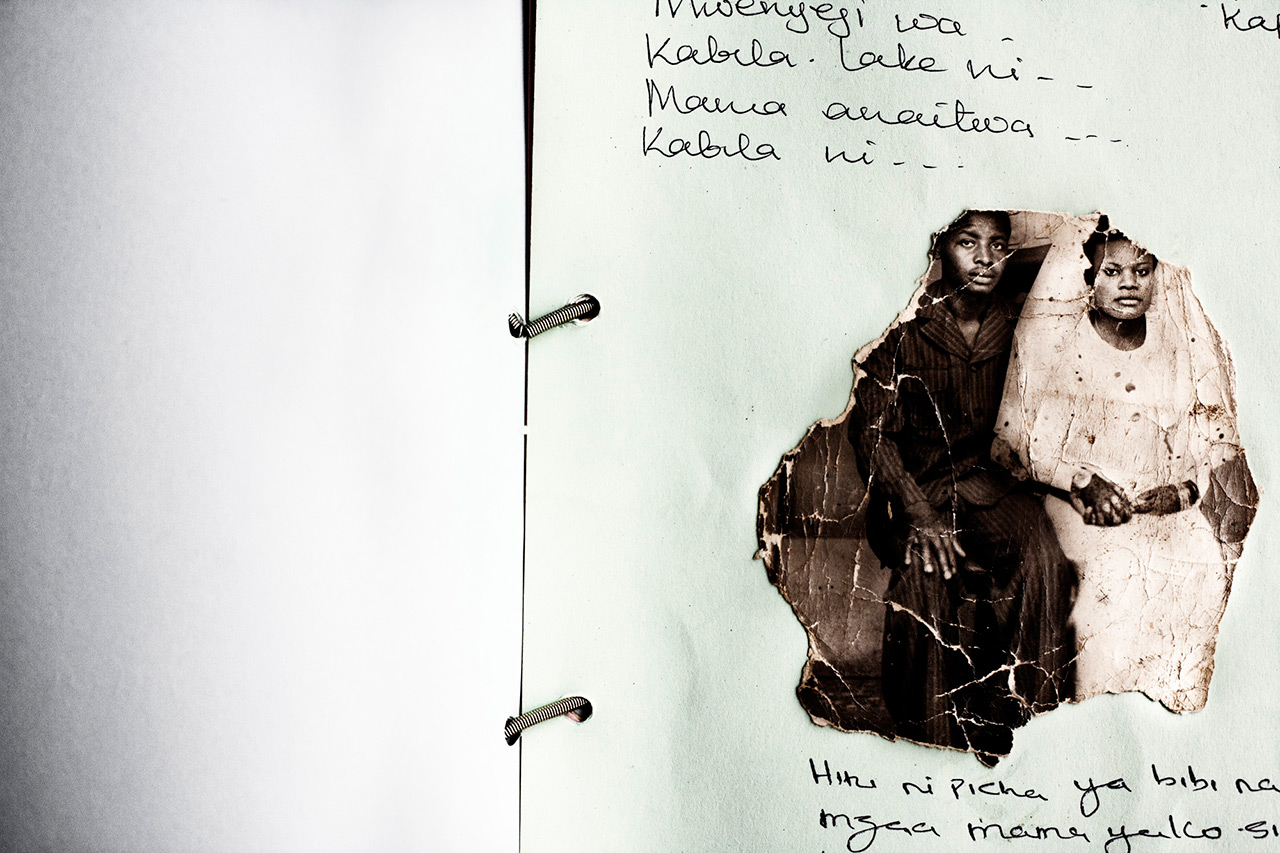

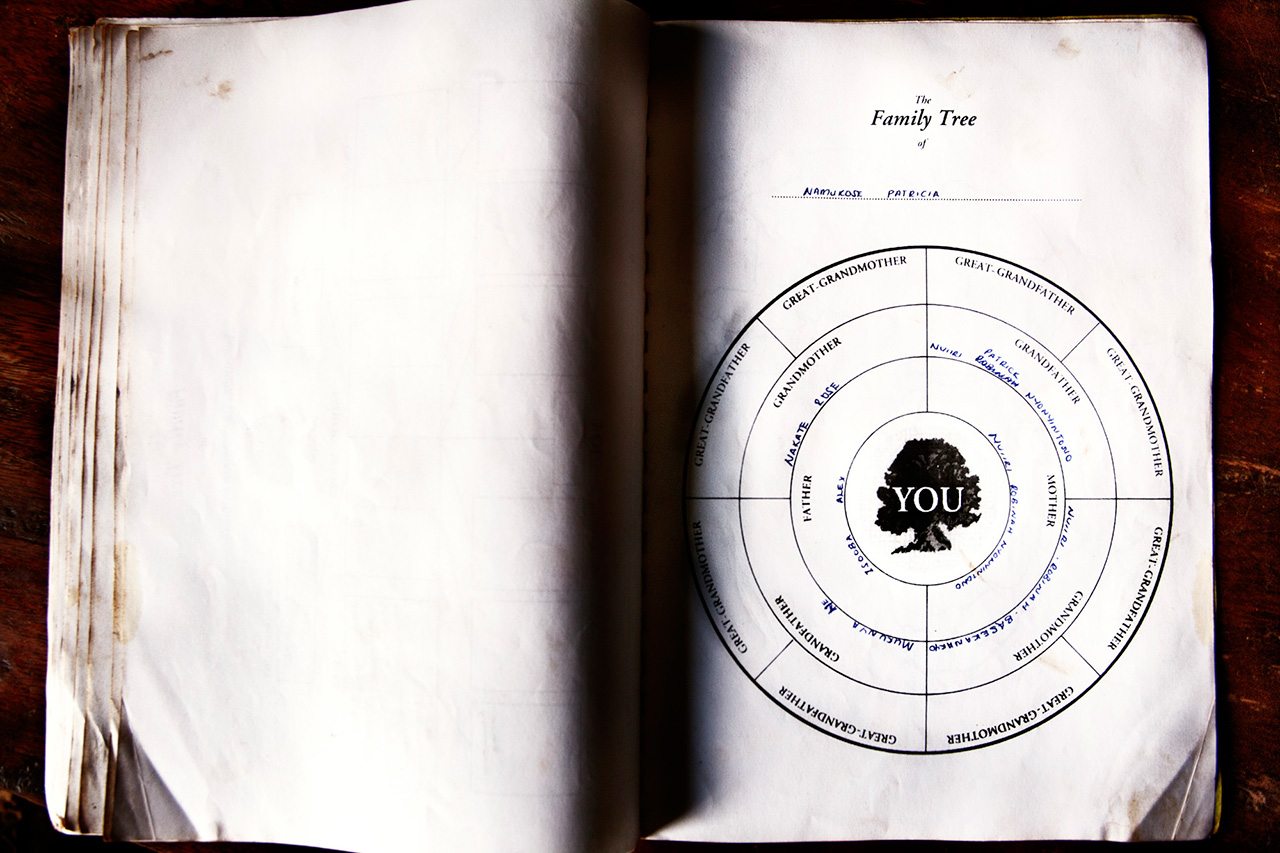

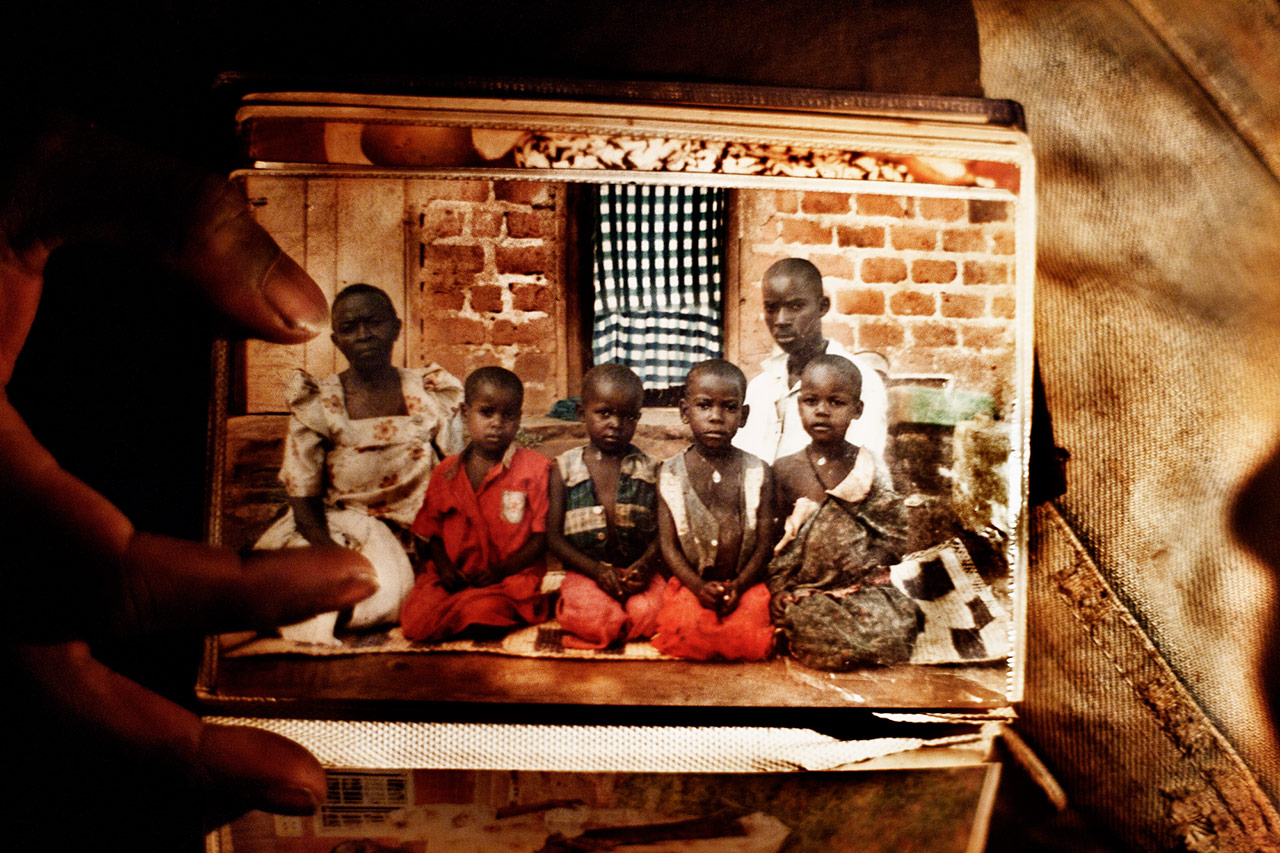

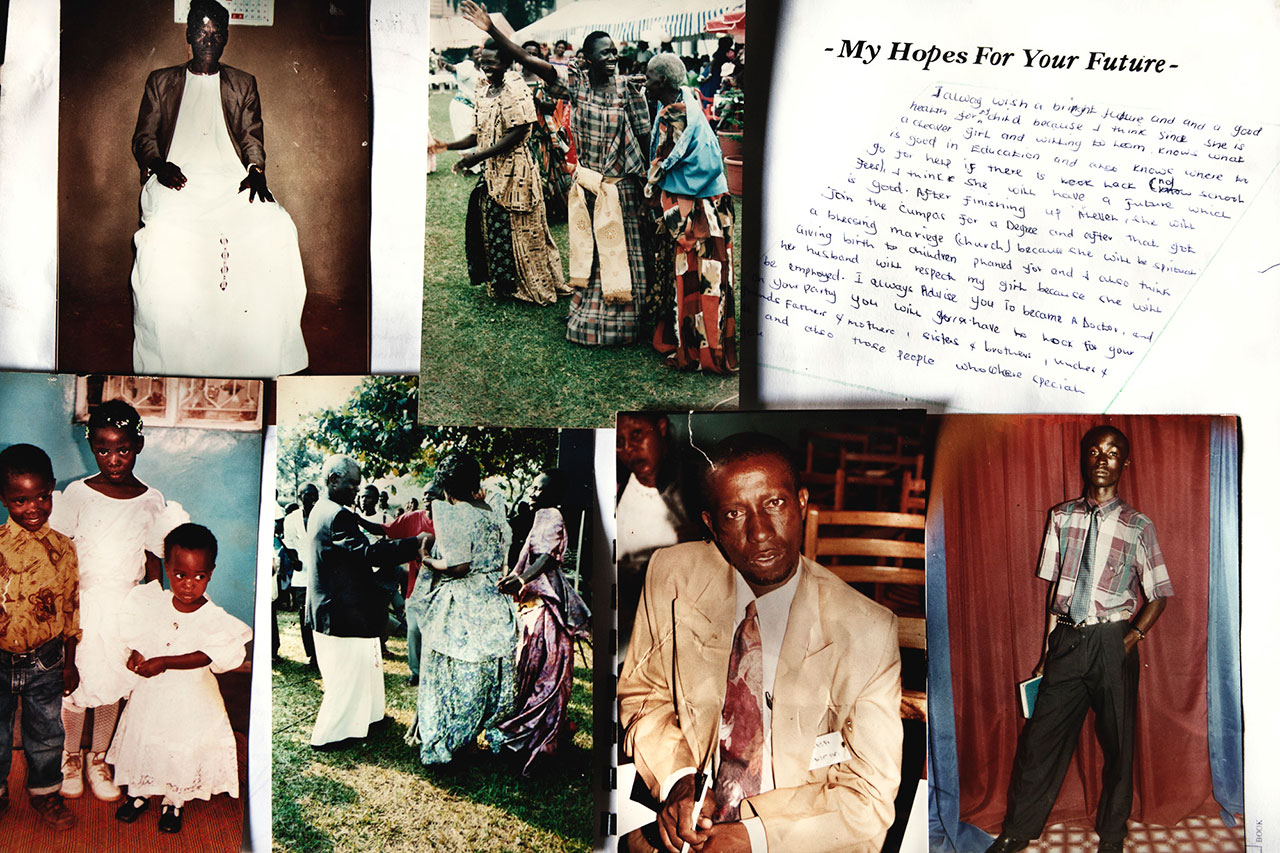

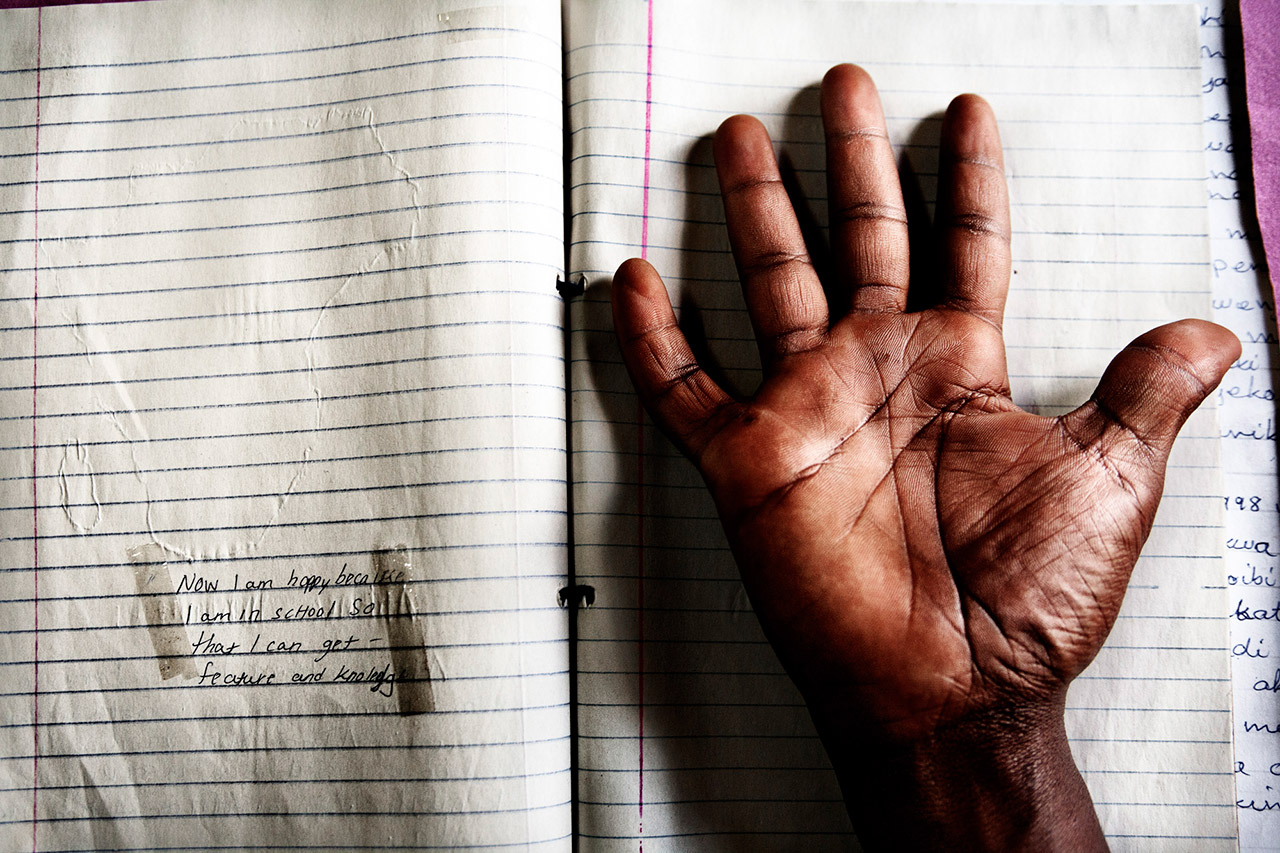

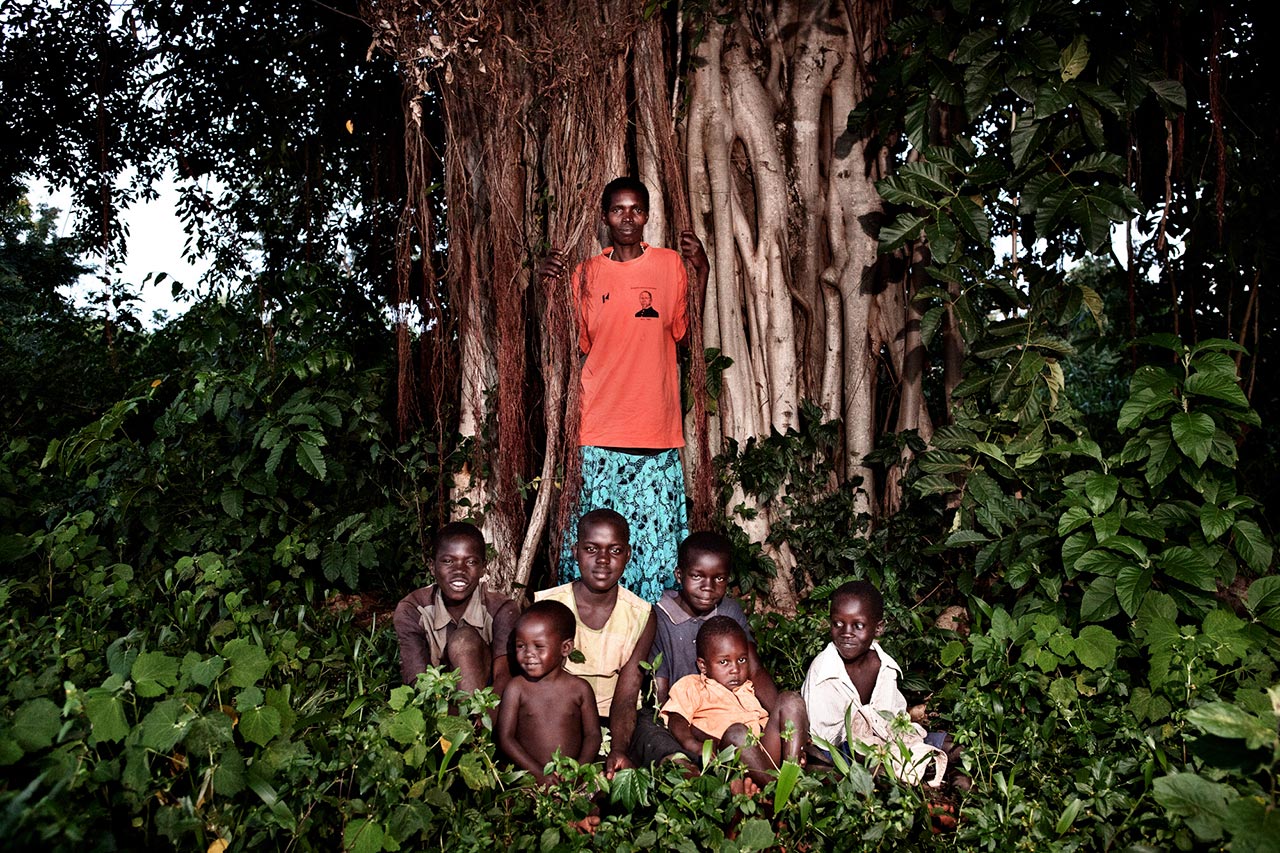

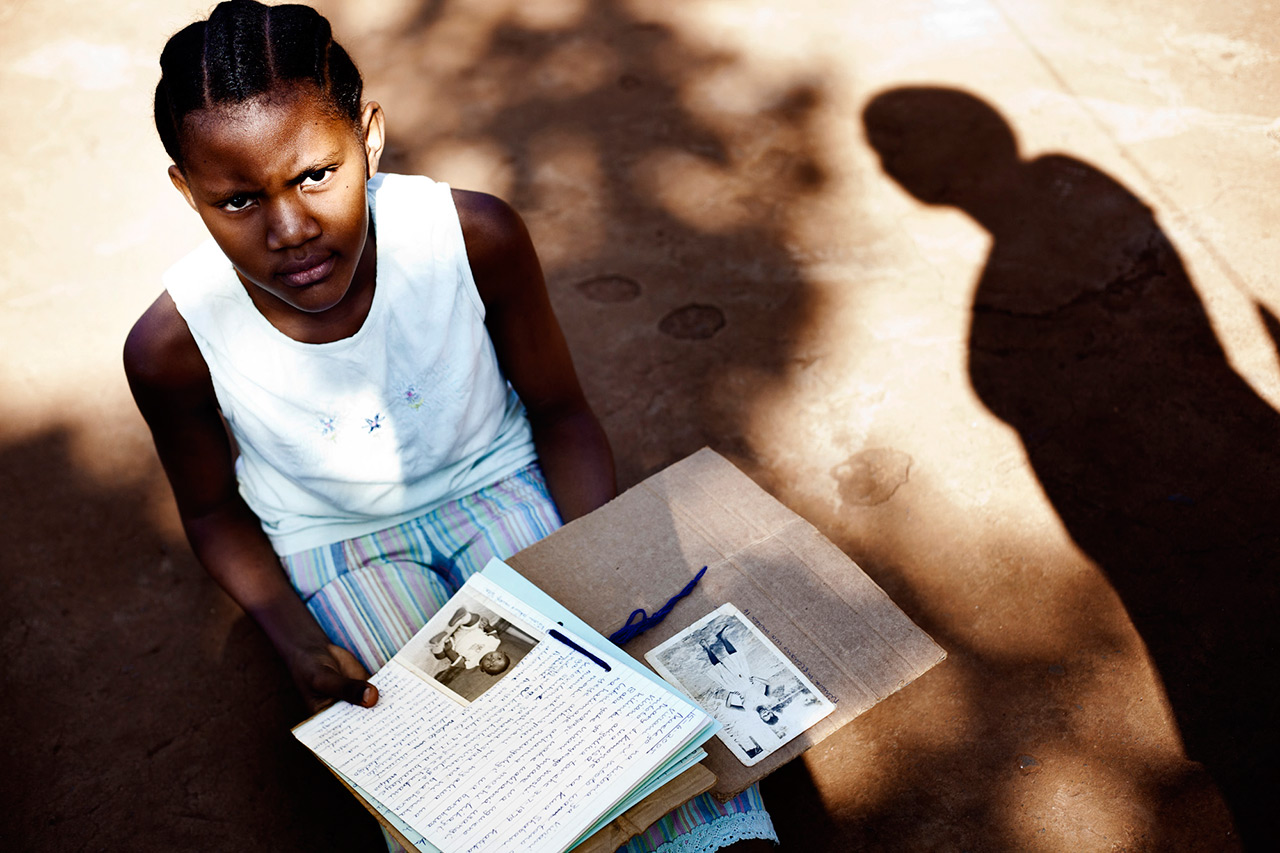

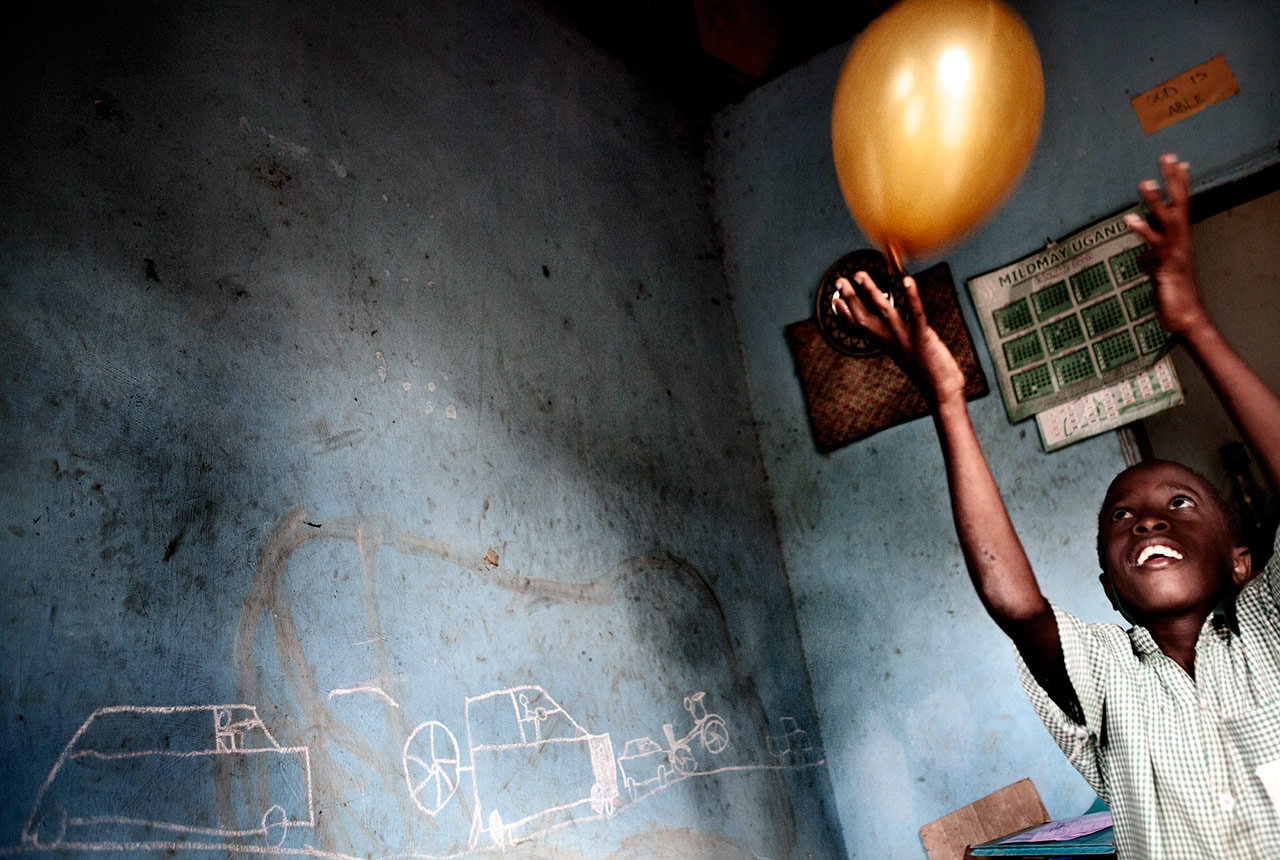

In Uganda, by the beginning of the nineties, corpses kept piling up in the morgues and nobody knew what was going on. During the days when it seemed like hope had escaped that land, a few HIV positive women decided to bring it back, not for them but for their children. That is how NACWOLA (National Community of Women Living with HIV/AIDS) was born, during the International Conference on AIDS held in Amsterdam in 1992. The three founding members died of AIDS during the following years, but their legacy was a ray of light in the darkest days. With the help of European health and psychology professionals, the decided to put in writing what they would never be able to tell their children, and they created the Memory Books. These books are their recollections, they tell us about them and the future they want for their children n pages full of words of care and affection. They are motherhood guides from beyond, survival tutorials for lost children, since over 12% of Sub-Saharan underage population will lose at least one of their parents in the next 12 months, and they will be on their own. As Gladys, the person in charge of the Memory Books project in Luwero, the center of the country, tell us: "They are each special and very personal, in spite of following a common pattern that includes family photos, memories and a family tree. With these books we encourage parents to listen to their children, to talk to them frankly about their disease."

The project is like a big family with members helping each other emotionally and financially in their daily struggle for survival. Mothers, orphans and grandmothers, many of them displaced by the internal war with the LRA (Lord's Resistance Army). In a country where 35% of the population is HIV positive, where there are two million orphans, a country in which polygamy and dowry are common practice, these women are struggling against the AIDS stigma and are not afraid of anything. NACWOLA and the project have given them back hope.