Diego Goldberg

On June 17th, every year, the family goes through a private ritual:

we photograph ourselves to stop, for a fleeting moment, the arrow of time passing by.

Diego Goldberg (Argentina, 1946). Lives and works in Argentina. He has taken part in group and solo exhibitions. Among other distinctions, Goldberg has won the Gold Medal 1998 from the Society of Publications Design; the Award of Merit 1998 from the Art Directors Club of New York for The Arrow of Time; second prize at the World Press Photo (Amsterdam, 1983) for Chile Ten Years After the Coup; and First Prize in the New York Press Award 1981 for Alphonse D’Amato, commissioned by the New York Times Magazine. He also won the FNPI (Gabriel García Márquez Foundation) Prize in 2006 for the Pursuing a dream. Diego can be reached at: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. and you can visit his website.

Diego Goldberg (Argentina, 1946). Lives and works in Argentina. He has taken part in group and solo exhibitions. Among other distinctions, Goldberg has won the Gold Medal 1998 from the Society of Publications Design; the Award of Merit 1998 from the Art Directors Club of New York for The Arrow of Time; second prize at the World Press Photo (Amsterdam, 1983) for Chile Ten Years After the Coup; and First Prize in the New York Press Award 1981 for Alphonse D’Amato, commissioned by the New York Times Magazine. He also won the FNPI (Gabriel García Márquez Foundation) Prize in 2006 for the Pursuing a dream. Diego can be reached at: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. and you can visit his website.

On June 17th, every year, the family goes through a private ritual:

we photograph ourselves to stop, for a fleeting moment, the arrow of time passing by.

Diego Goldberg (Argentina, 1946). Lives and works in Argentina. He has taken part in group and solo exhibitions. Among other distinctions, Goldberg has won the Gold Medal 1998 from the Society of Publications Design; the Award of Merit 1998 from the Art Directors Club of New York for The Arrow of Time; second prize at the World Press Photo (Amsterdam, 1983) for Chile Ten Years After the Coup; and First Prize in the New York Press Award 1981 for Alphonse D’Amato, commissioned by the New York Times Magazine. He also won the FNPI (Gabriel García Márquez Foundation) Prize in 2006 for the Pursuing a dream. Diego can be reached at: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. and you can visit his website.

Diego Goldberg (Argentina, 1946). Lives and works in Argentina. He has taken part in group and solo exhibitions. Among other distinctions, Goldberg has won the Gold Medal 1998 from the Society of Publications Design; the Award of Merit 1998 from the Art Directors Club of New York for The Arrow of Time; second prize at the World Press Photo (Amsterdam, 1983) for Chile Ten Years After the Coup; and First Prize in the New York Press Award 1981 for Alphonse D’Amato, commissioned by the New York Times Magazine. He also won the FNPI (Gabriel García Márquez Foundation) Prize in 2006 for the Pursuing a dream. Diego can be reached at: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. and you can visit his website.

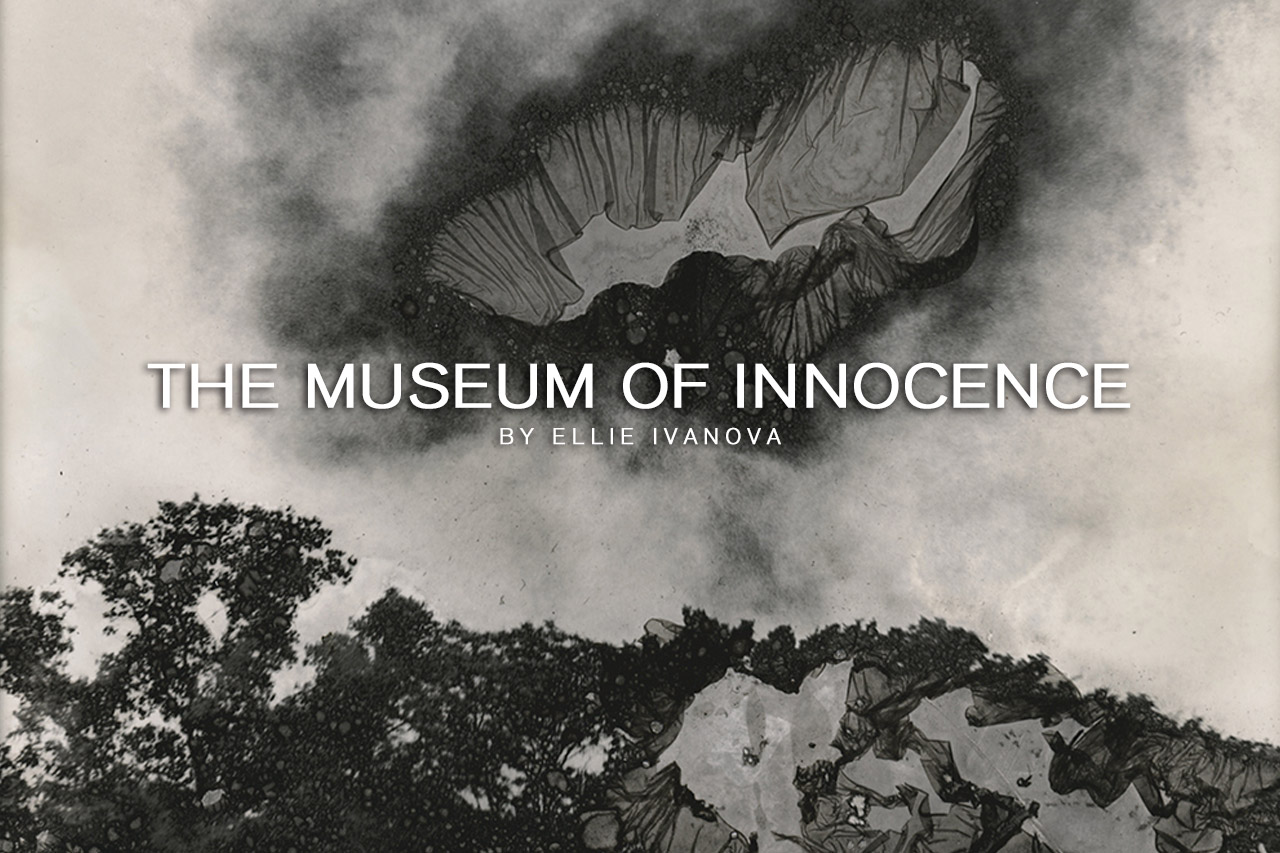

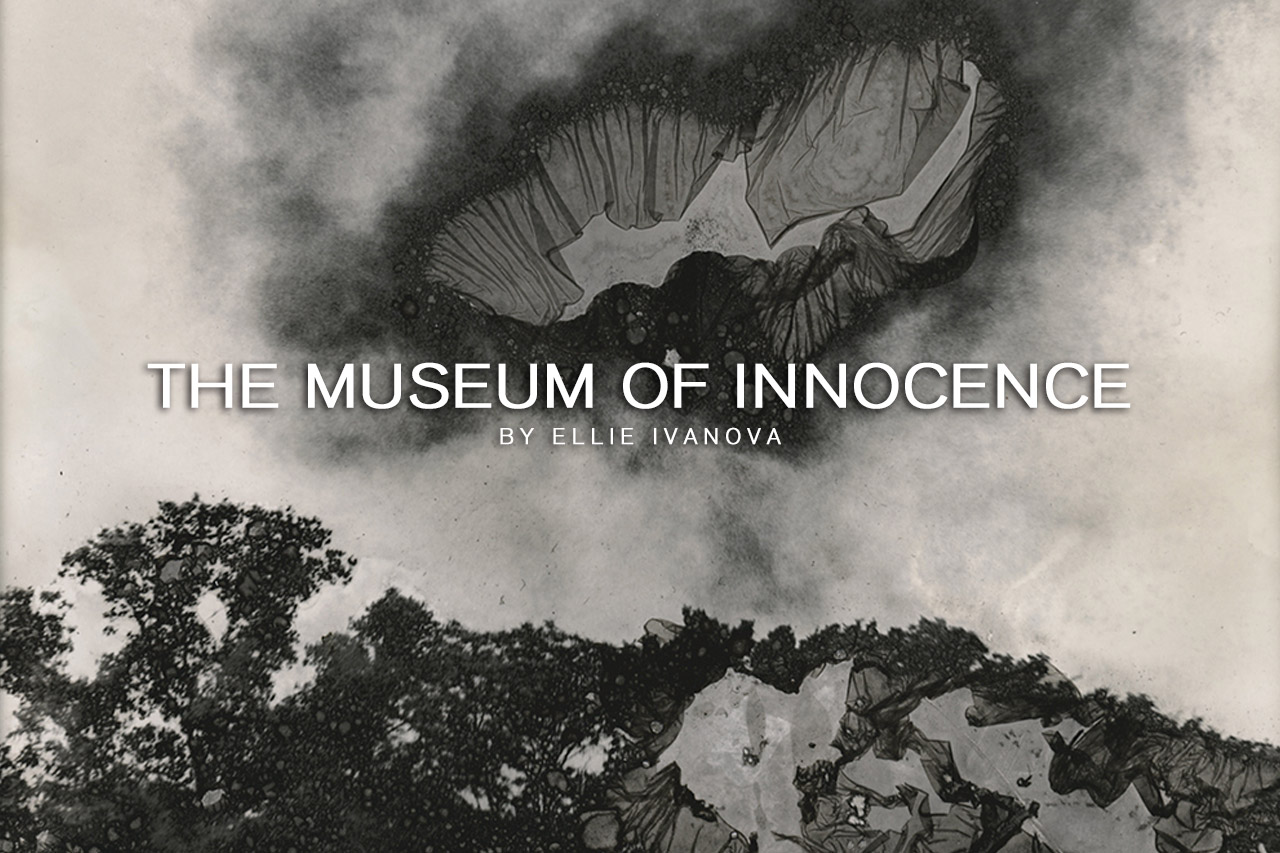

Ellie Ivanova

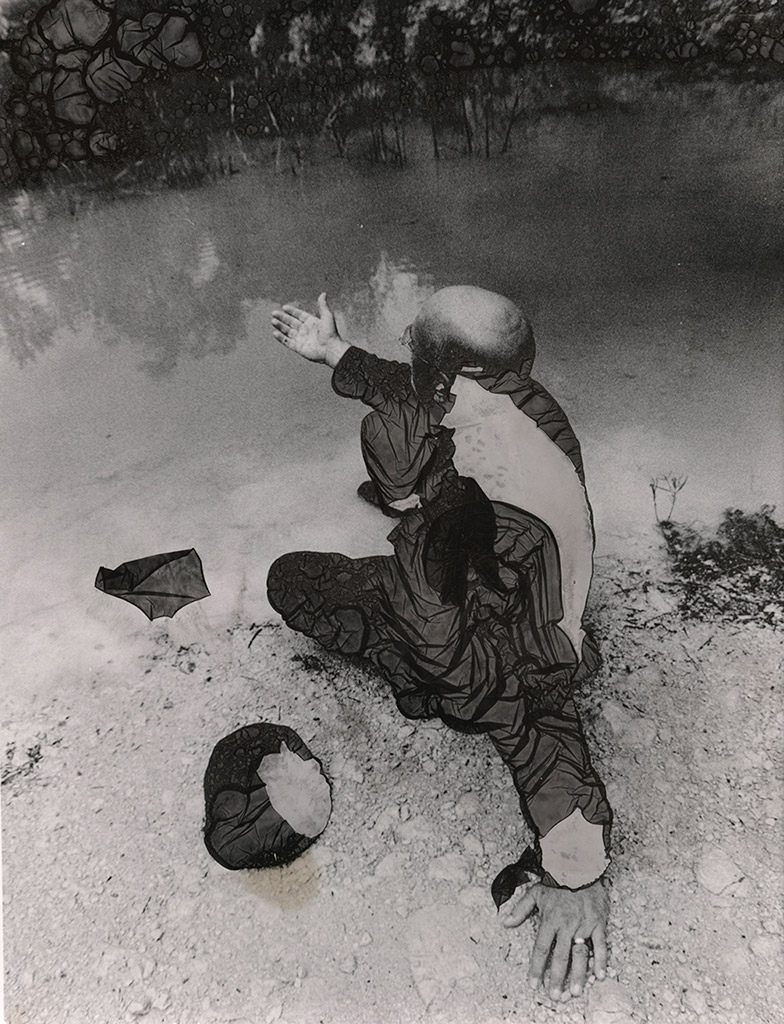

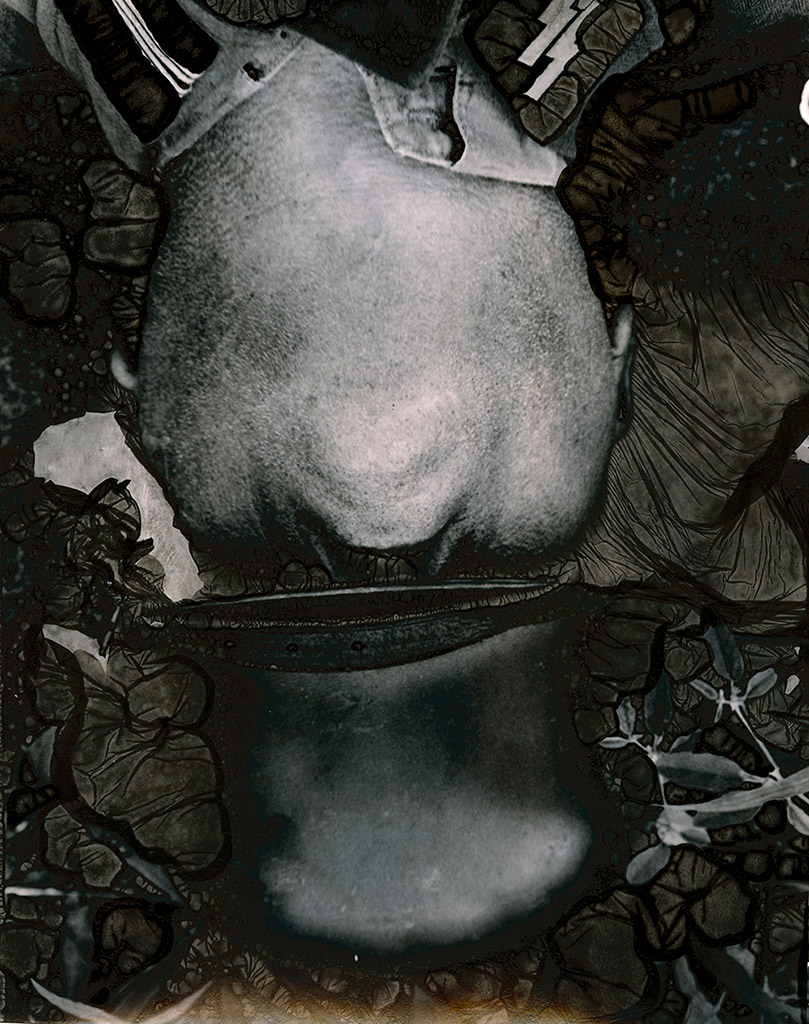

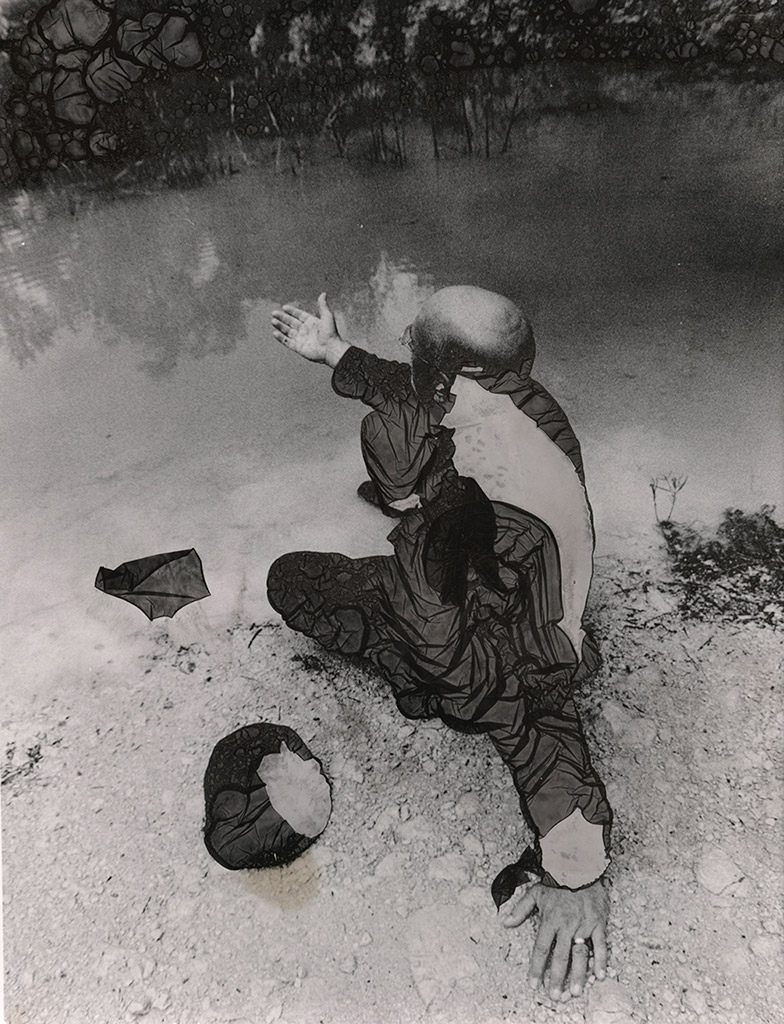

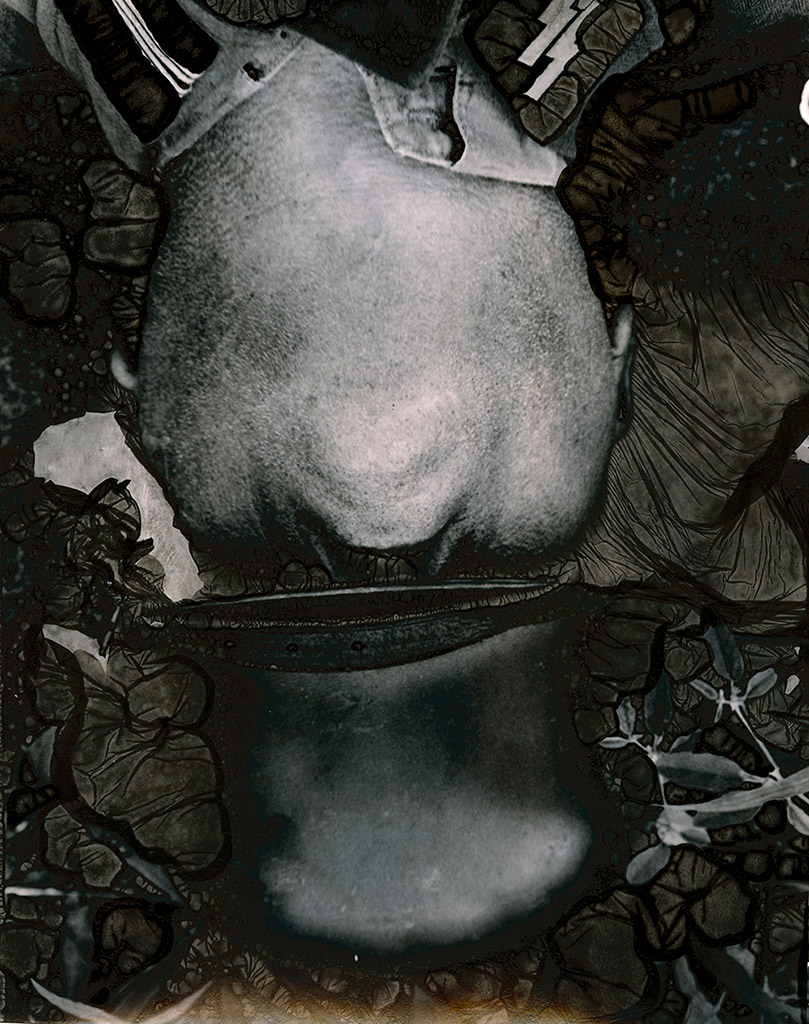

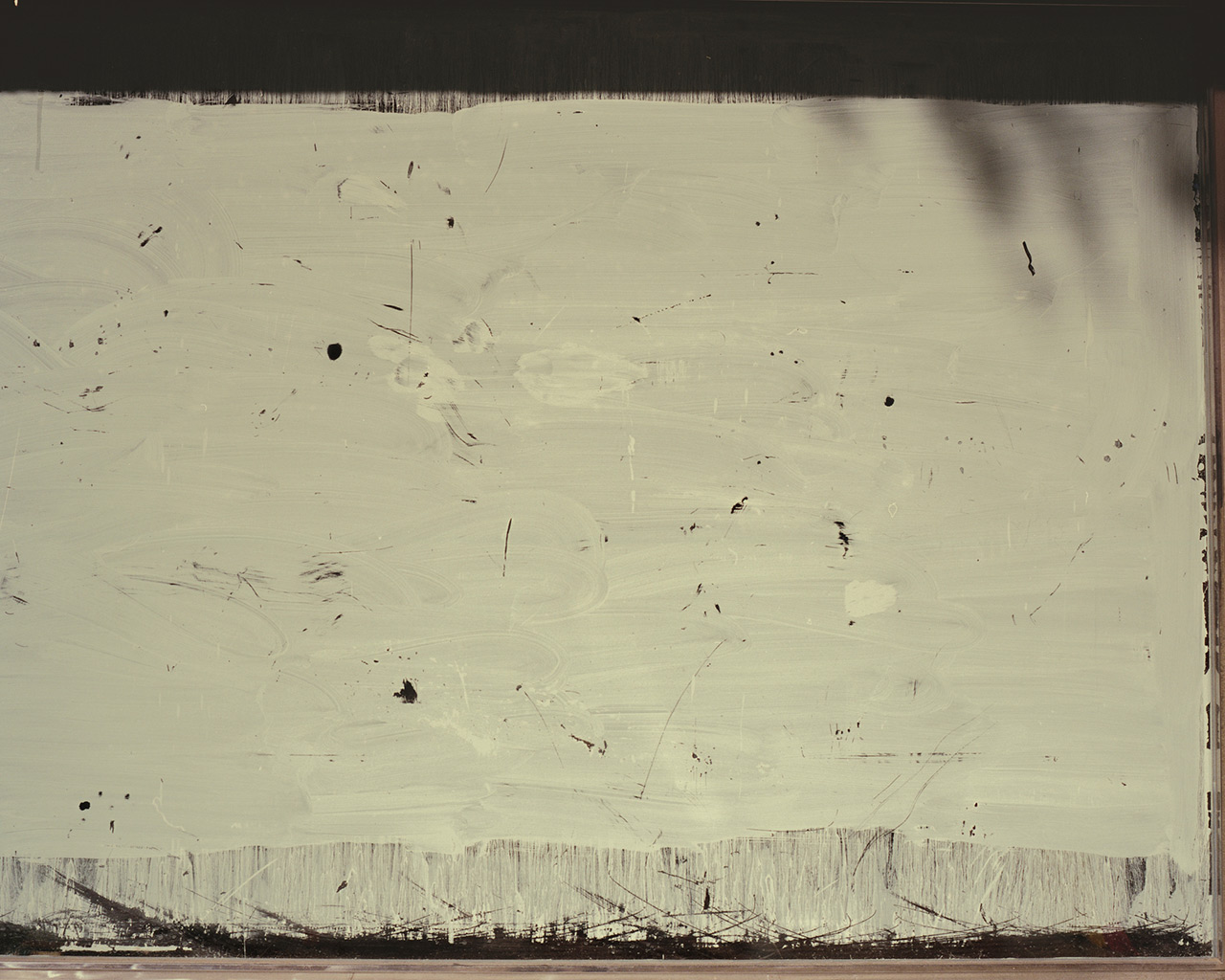

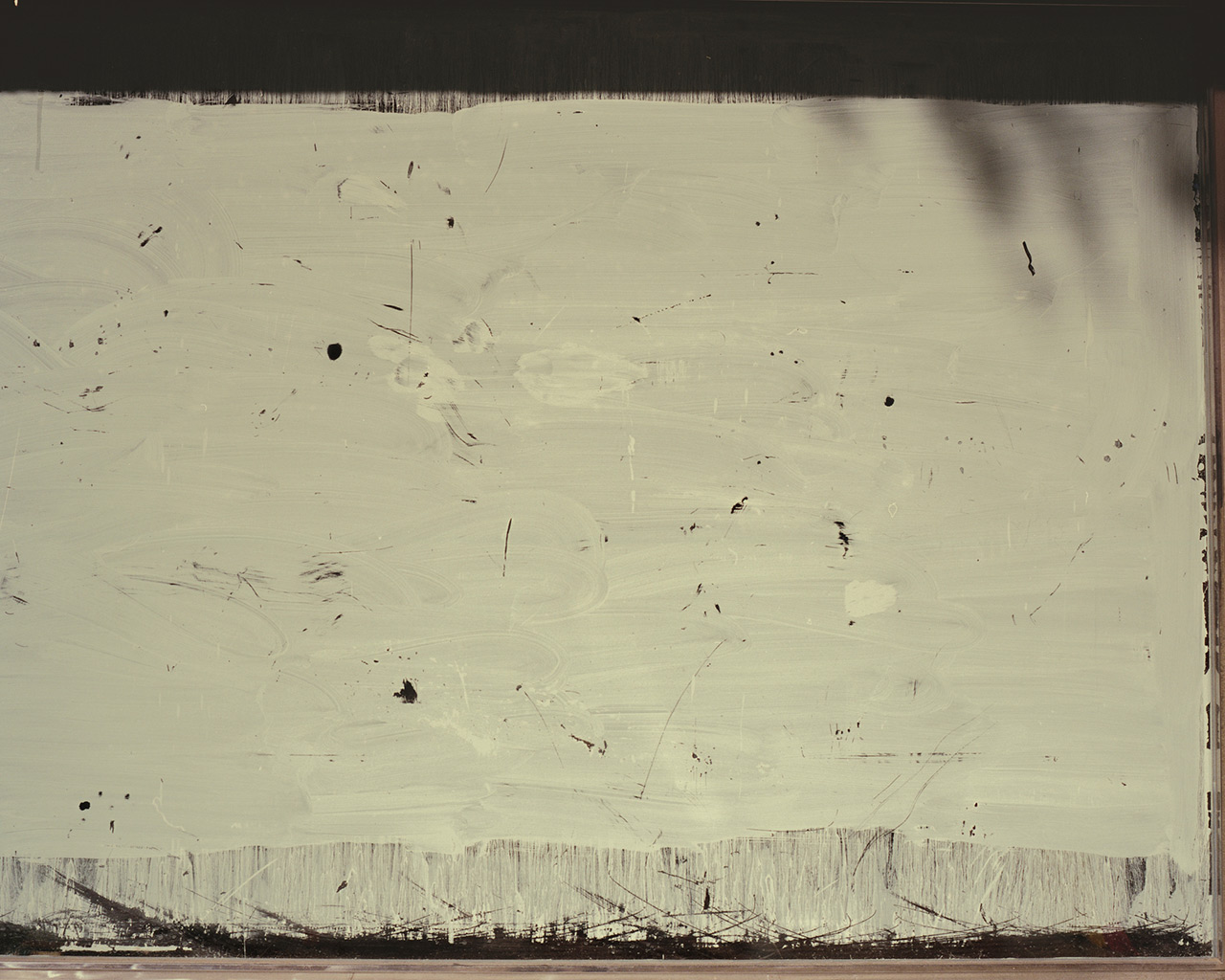

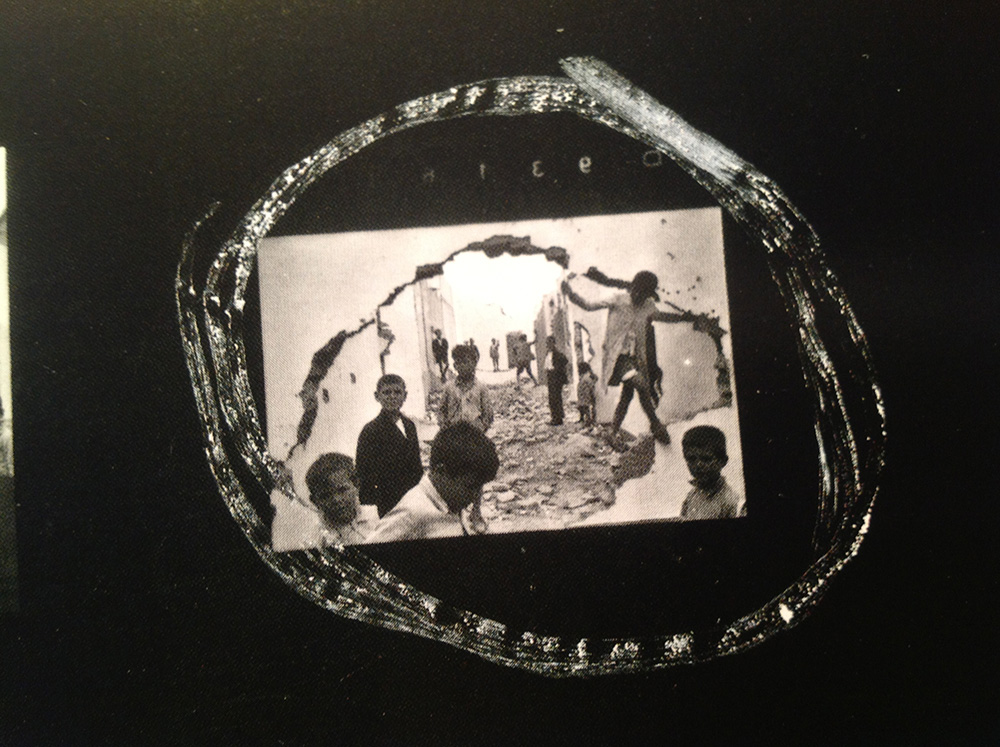

As a photographic artist, I am interested in the fraught relationship between photography and memory that creates a new reality in the gradual process of shifting and distortion. This project explores how memory appropriates history through photography and how it changes our perceptions of the past.

I document World War II reenactments in Texas. This war, which has become part of the foundational myth of the contemporary United States, has remained one of the few unquestioned sources of national identity, justice and masculinity today. Yet even though considered “the good war” that doesn’t need to be embellished in the public consciousness, the past is being constantly reinterpreted and changed through the reenactment movement. Photography plays a significant role in this process as participants recreate historic photographs in their roleplay and then use newly taken pictures of themselves to present their made-up historic persona. This distortion of recreating and personification of history is then reflected in the acid-bath mordancage process through its degradation, toxicity, unpredictability, physicality and surreal final result.

As a process, this project goes against the grain of what photography is. I use it as an ideological reaction to the noncommittal pull of digital culture. Instead of fixing the moment forever, it erases the image and alters the emulsion. Instead of endless multiples, it produces unique, unrepeatable prints. Instead of an objective optic capture, it is a physical object that shows the hand of the artist in its tactile recreation. It is toxic, unpredictable and shifts over time. Just like memory, it reflects the constant battle between preservation and ephemerality.

>

>

Ellie Ivanova (Bulgaria). She holds an MFA in Photography from the University of North Texas. With a background in literature, her photographic interest is the experience of memory and the self-fashioning of identity, in both traditional and experimental formats. She uses processes and conceptual approaches through which images continue to evolve after they have been captured and printed, blurring the edges between the factual and the fictitious. Her photographs have been exhibited throughout the United States in commercial, non-profit and university galleries and are part of the permanent collections of Human Rights Art at South Texas College and Fort Wayne Museum of Art, among others.

Ellie Ivanova (Bulgaria). She holds an MFA in Photography from the University of North Texas. With a background in literature, her photographic interest is the experience of memory and the self-fashioning of identity, in both traditional and experimental formats. She uses processes and conceptual approaches through which images continue to evolve after they have been captured and printed, blurring the edges between the factual and the fictitious. Her photographs have been exhibited throughout the United States in commercial, non-profit and university galleries and are part of the permanent collections of Human Rights Art at South Texas College and Fort Wayne Museum of Art, among others.

As a photographic artist, I am interested in the fraught relationship between photography and memory that creates a new reality in the gradual process of shifting and distortion. This project explores how memory appropriates history through photography and how it changes our perceptions of the past.

I document World War II reenactments in Texas. This war, which has become part of the foundational myth of the contemporary United States, has remained one of the few unquestioned sources of national identity, justice and masculinity today. Yet even though considered “the good war” that doesn’t need to be embellished in the public consciousness, the past is being constantly reinterpreted and changed through the reenactment movement. Photography plays a significant role in this process as participants recreate historic photographs in their roleplay and then use newly taken pictures of themselves to present their made-up historic persona. This distortion of recreating and personification of history is then reflected in the acid-bath mordancage process through its degradation, toxicity, unpredictability, physicality and surreal final result.

As a process, this project goes against the grain of what photography is. I use it as an ideological reaction to the noncommittal pull of digital culture. Instead of fixing the moment forever, it erases the image and alters the emulsion. Instead of endless multiples, it produces unique, unrepeatable prints. Instead of an objective optic capture, it is a physical object that shows the hand of the artist in its tactile recreation. It is toxic, unpredictable and shifts over time. Just like memory, it reflects the constant battle between preservation and ephemerality.

>

>

Ellie Ivanova (Bulgaria). She holds an MFA in Photography from the University of North Texas. With a background in literature, her photographic interest is the experience of memory and the self-fashioning of identity, in both traditional and experimental formats. She uses processes and conceptual approaches through which images continue to evolve after they have been captured and printed, blurring the edges between the factual and the fictitious. Her photographs have been exhibited throughout the United States in commercial, non-profit and university galleries and are part of the permanent collections of Human Rights Art at South Texas College and Fort Wayne Museum of Art, among others.

Ellie Ivanova (Bulgaria). She holds an MFA in Photography from the University of North Texas. With a background in literature, her photographic interest is the experience of memory and the self-fashioning of identity, in both traditional and experimental formats. She uses processes and conceptual approaches through which images continue to evolve after they have been captured and printed, blurring the edges between the factual and the fictitious. Her photographs have been exhibited throughout the United States in commercial, non-profit and university galleries and are part of the permanent collections of Human Rights Art at South Texas College and Fort Wayne Museum of Art, among others.Kostya Smolyaninov

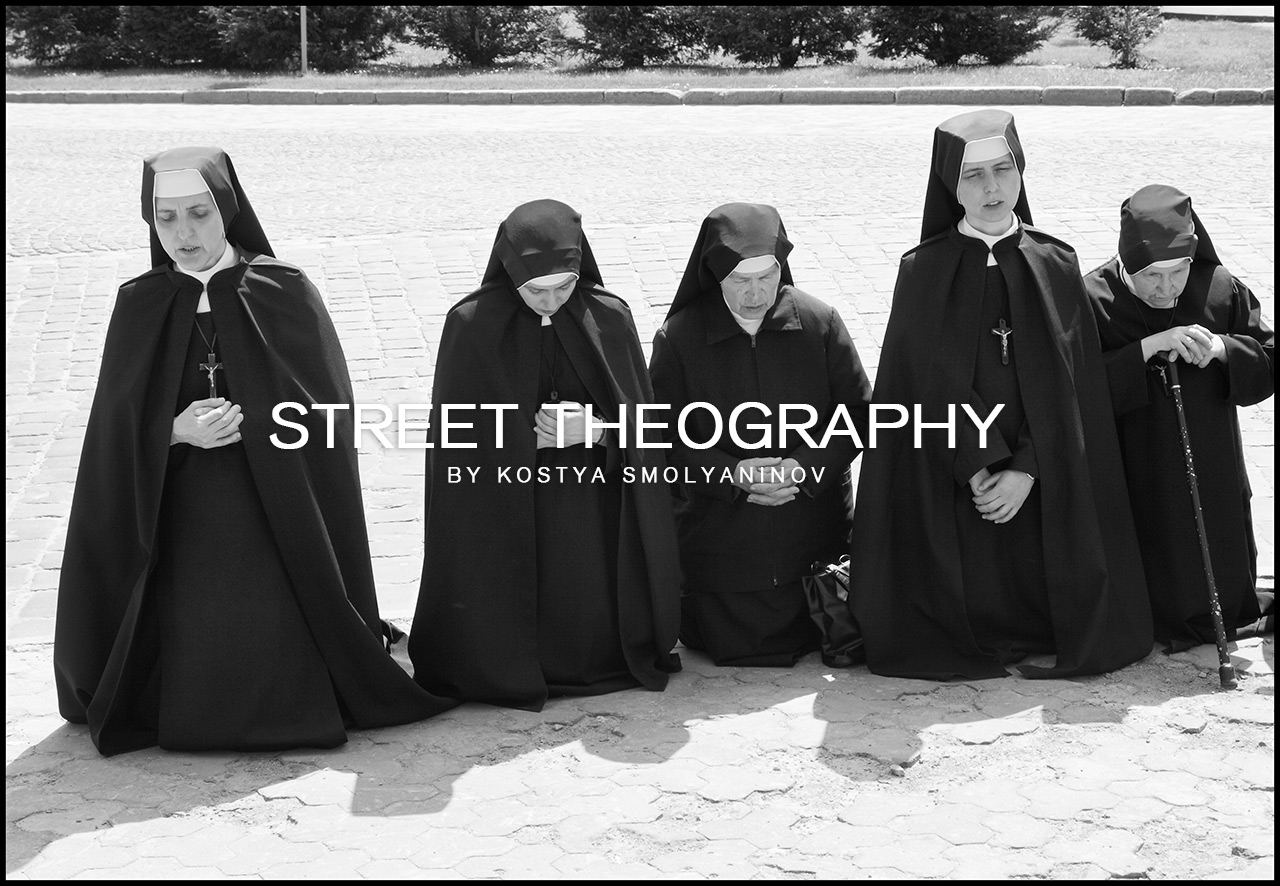

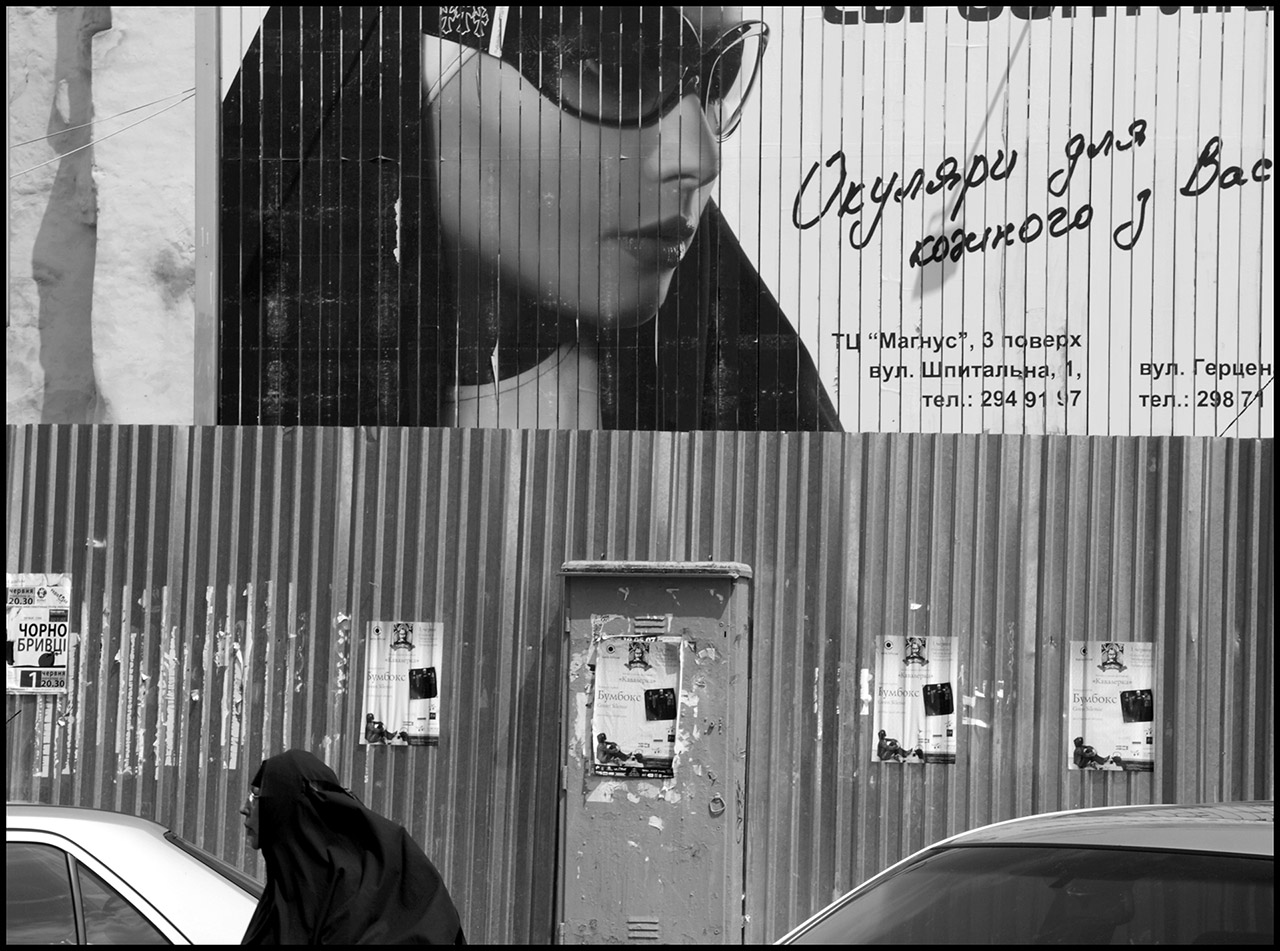

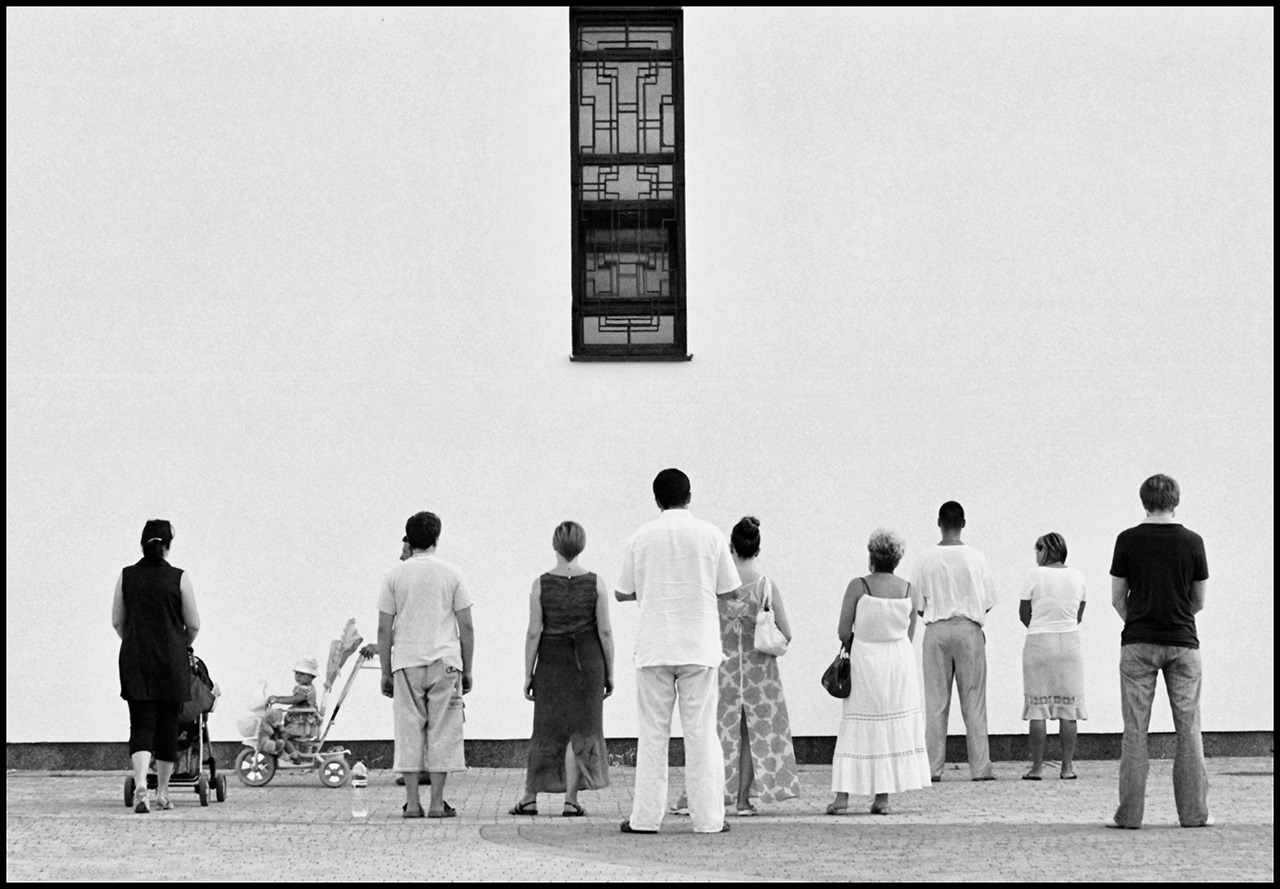

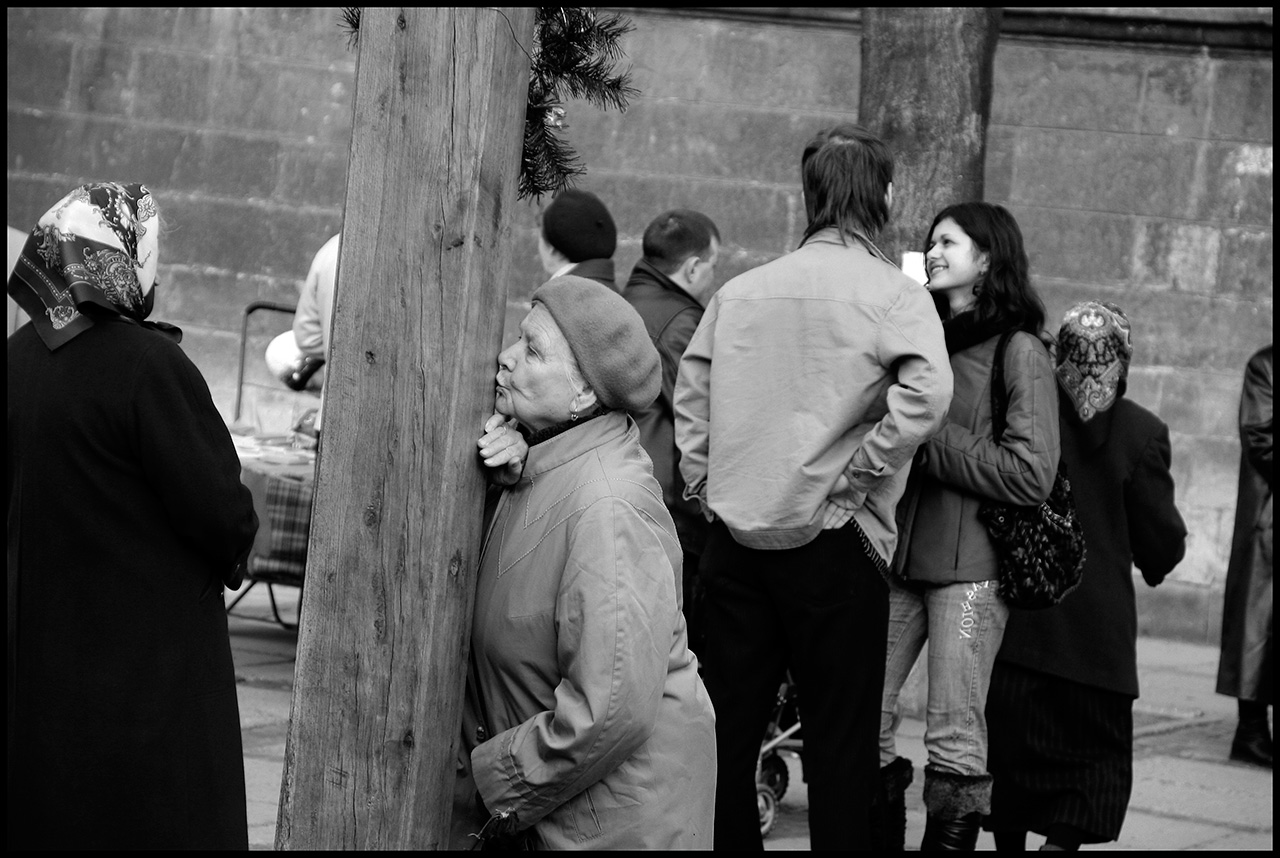

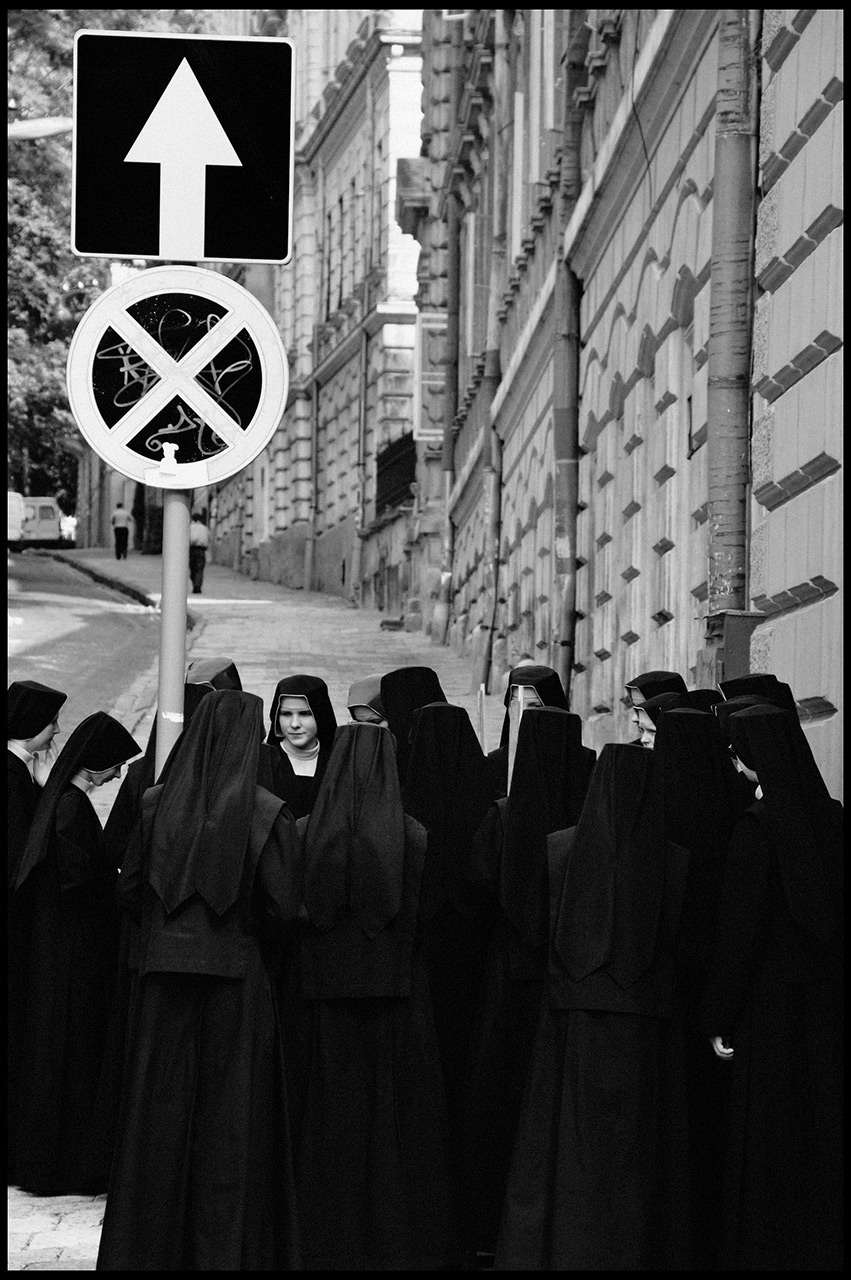

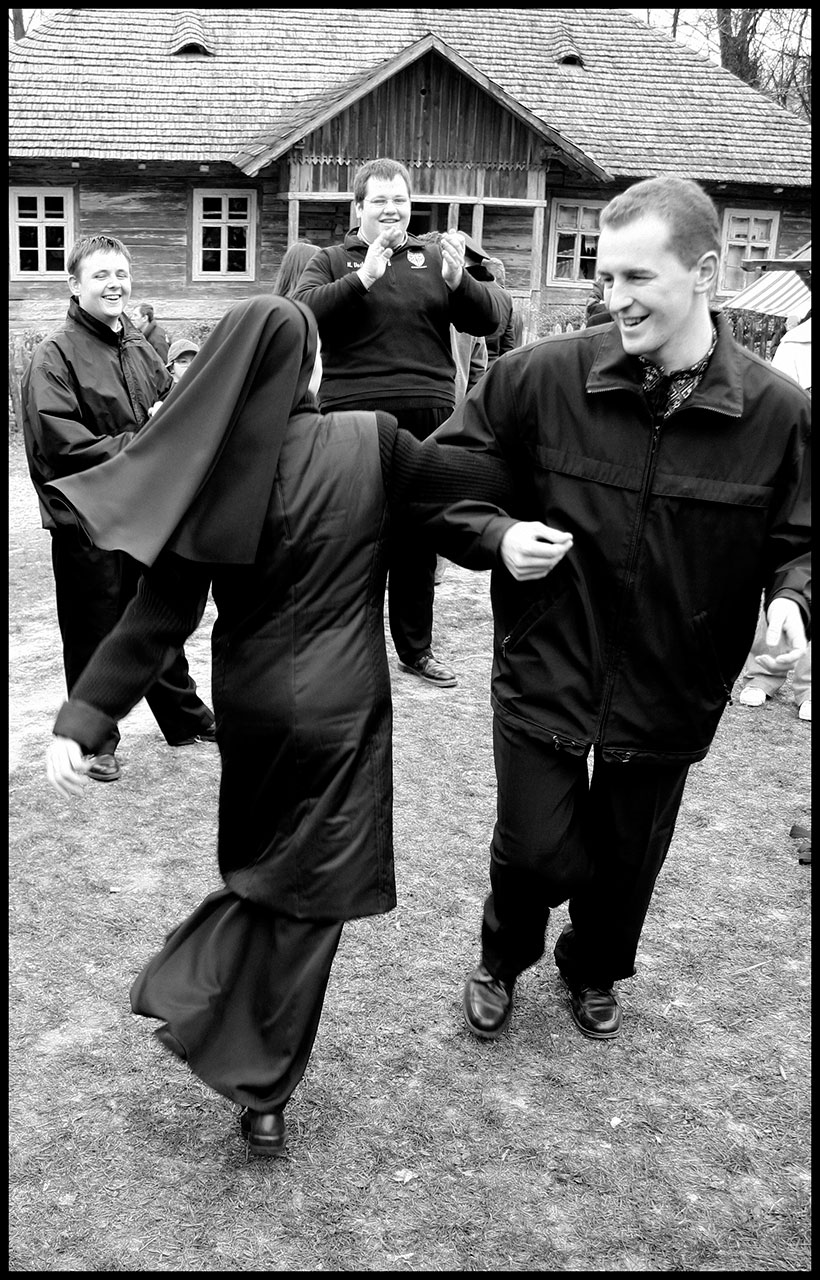

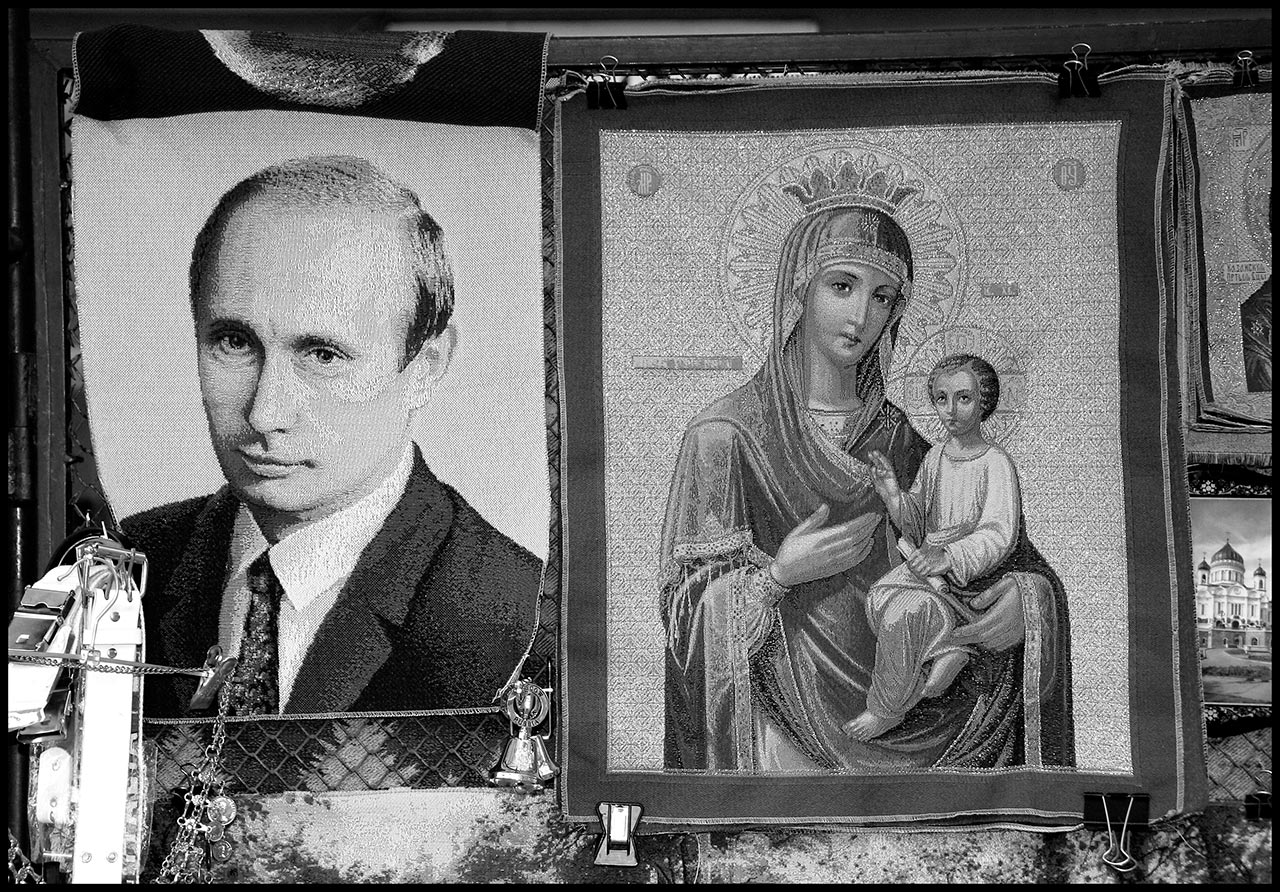

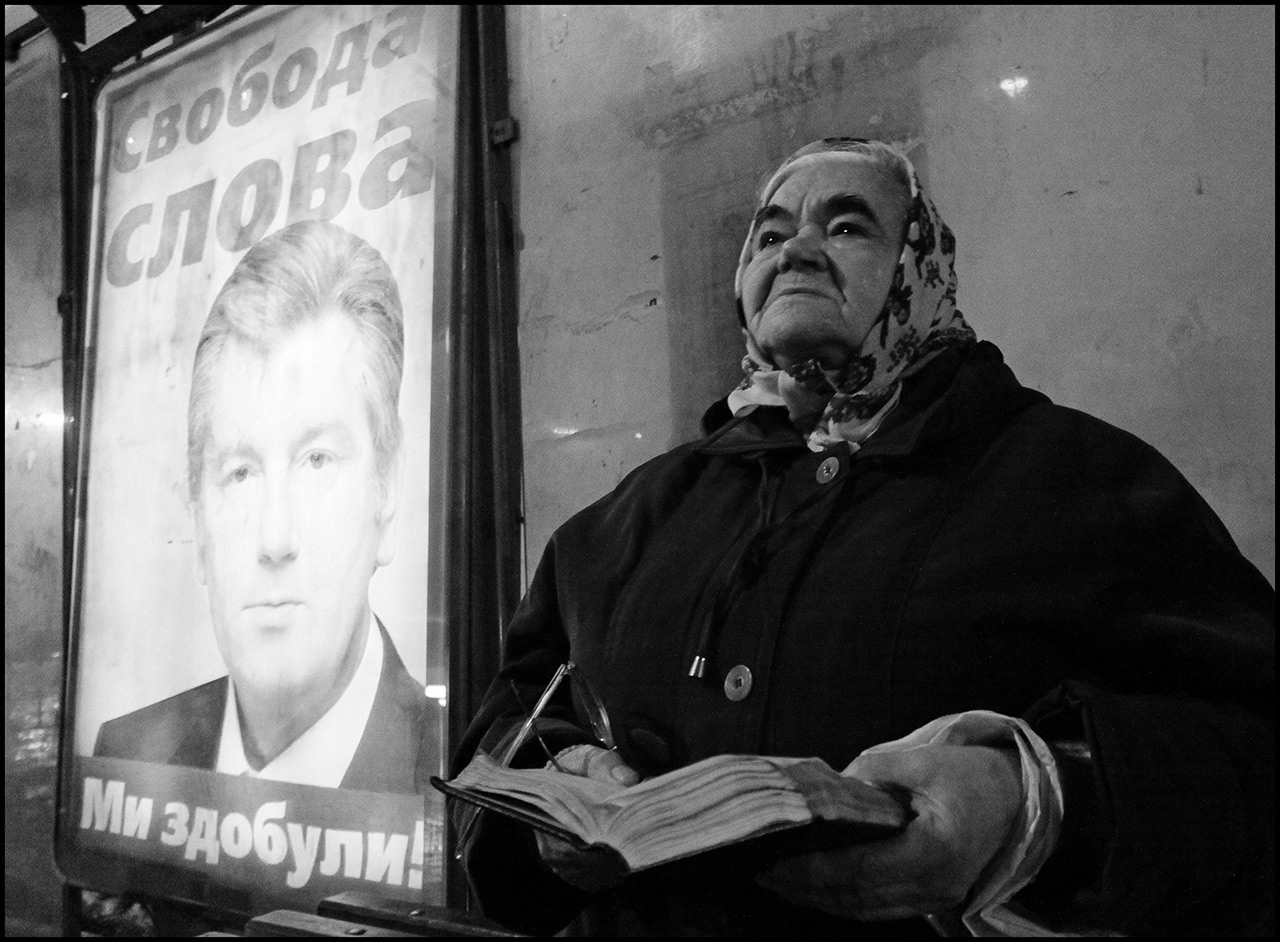

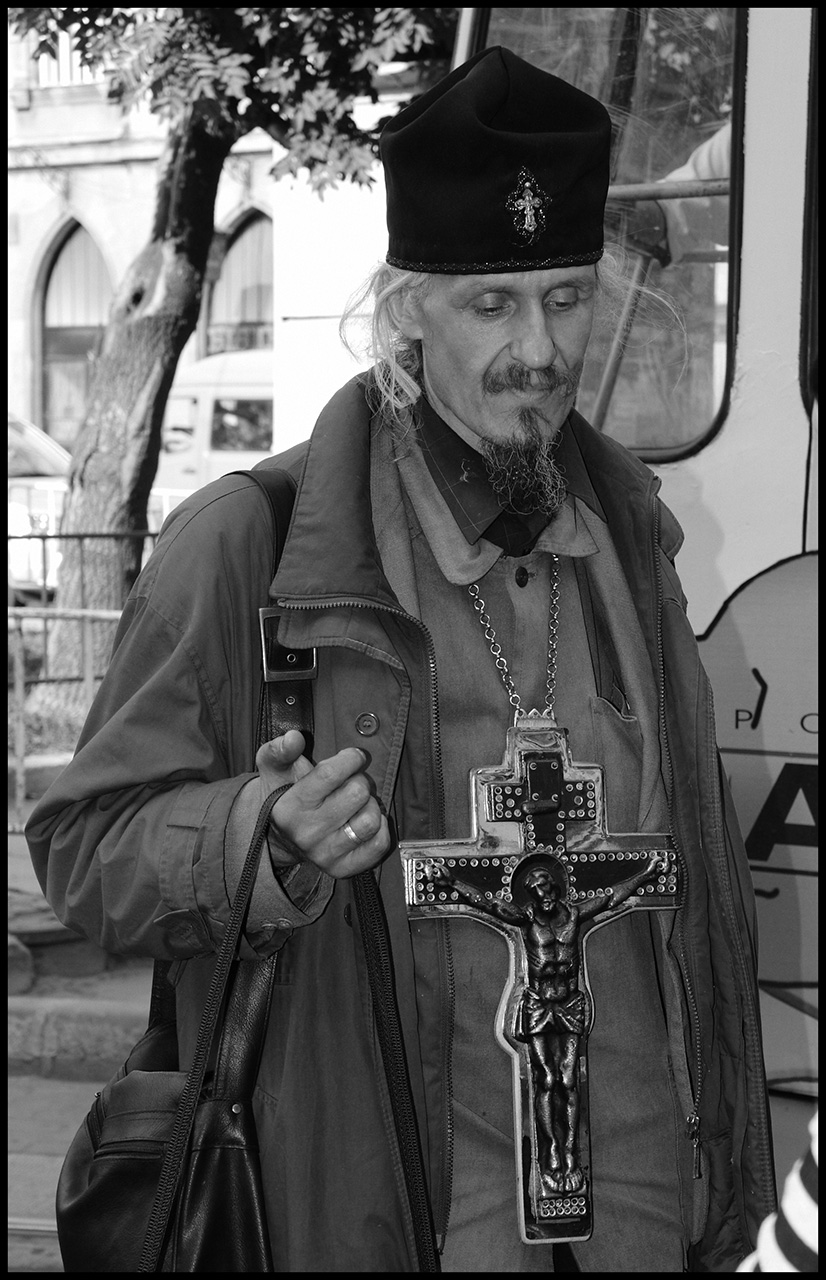

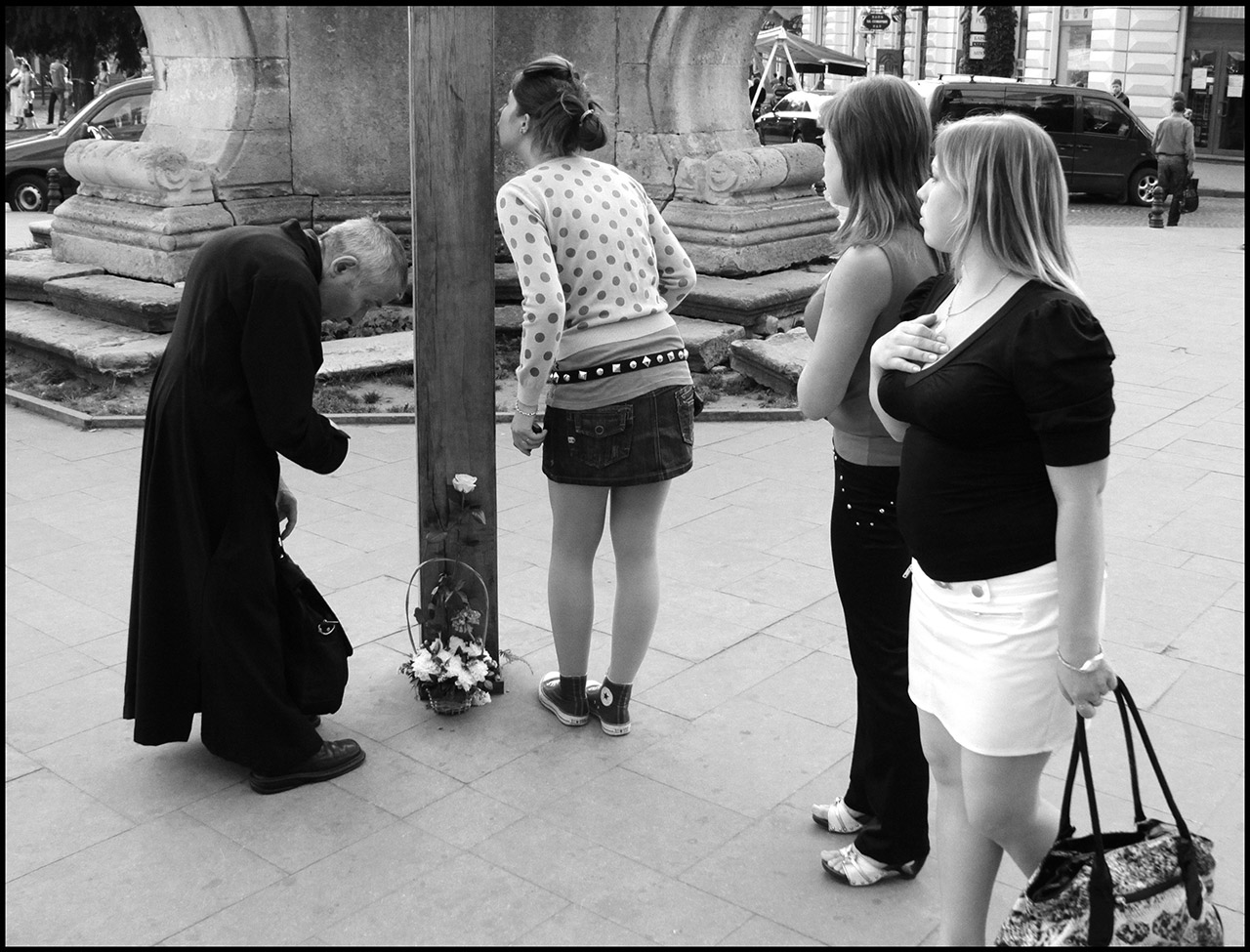

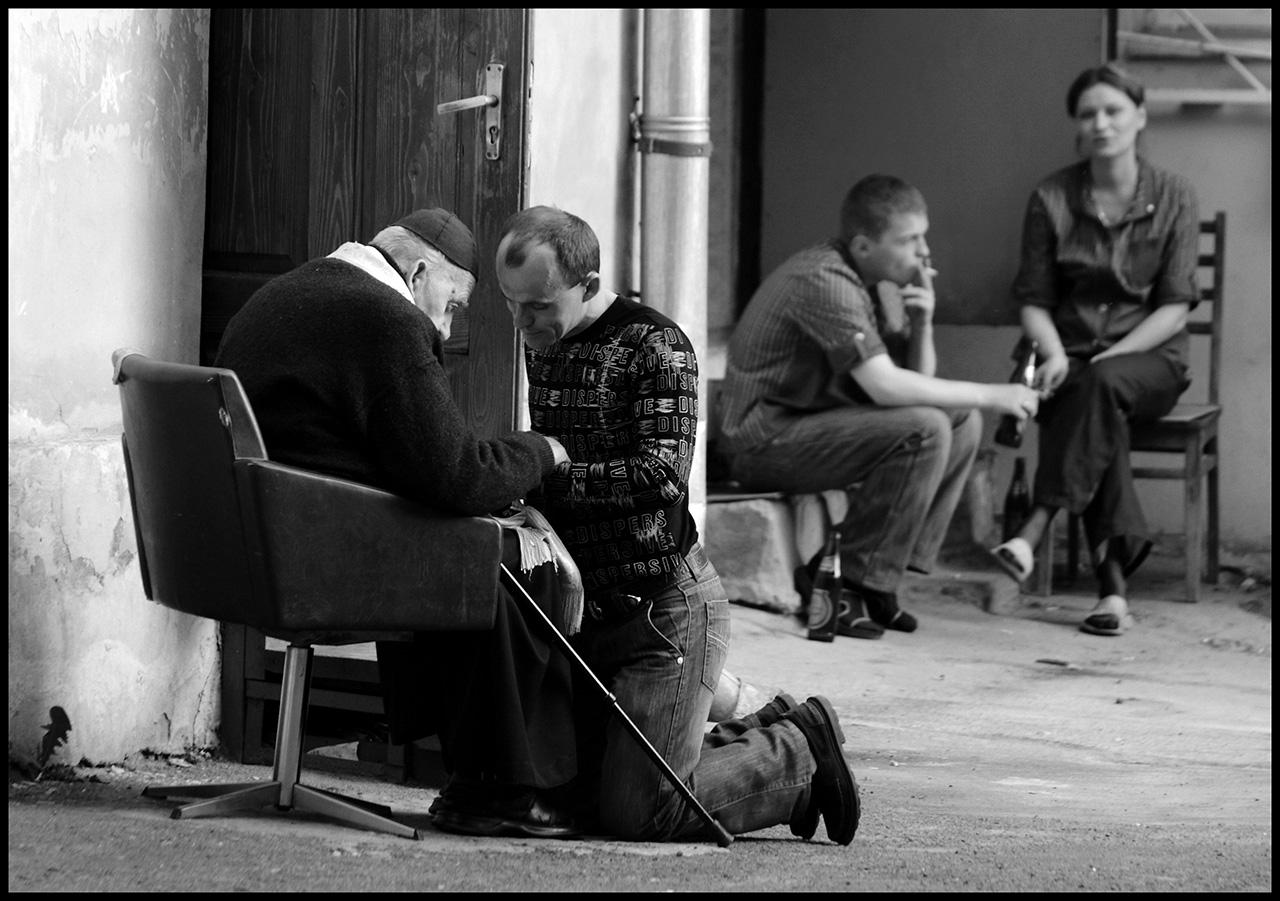

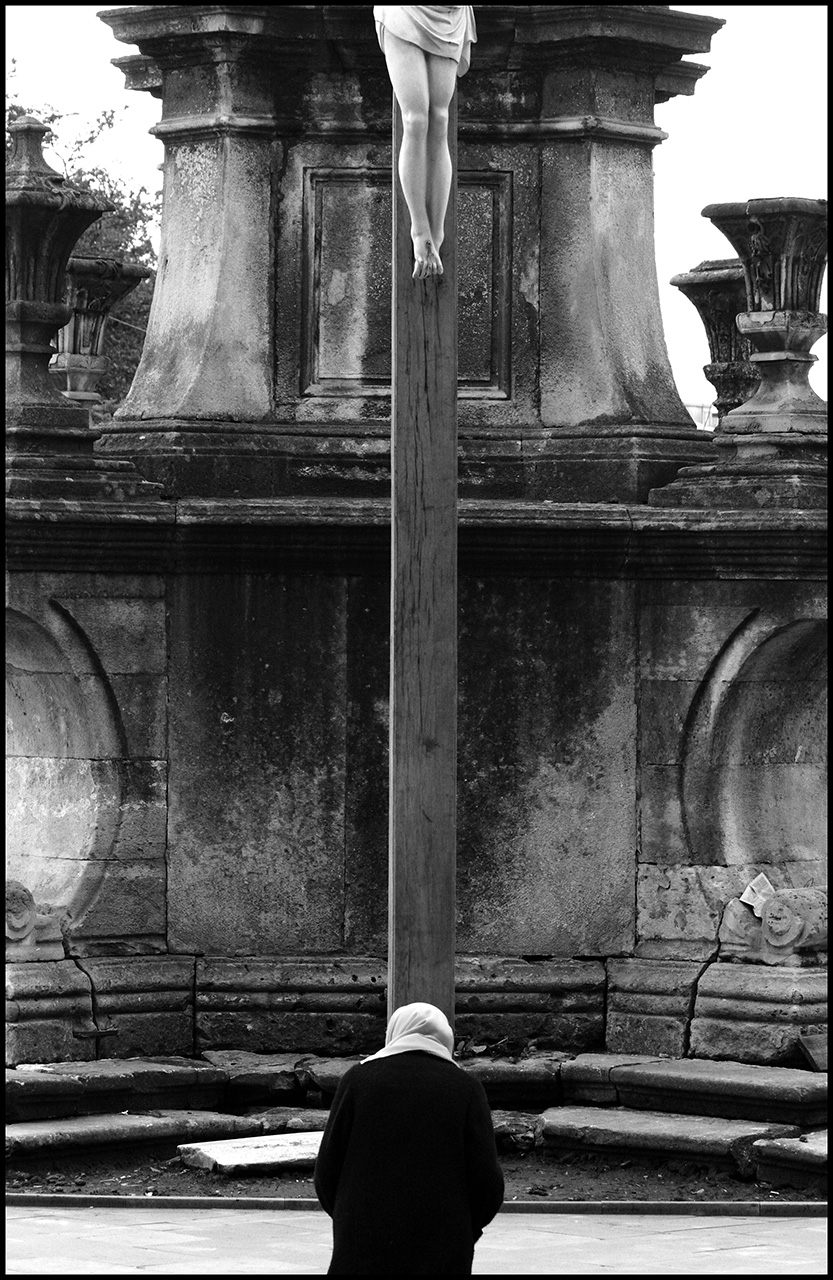

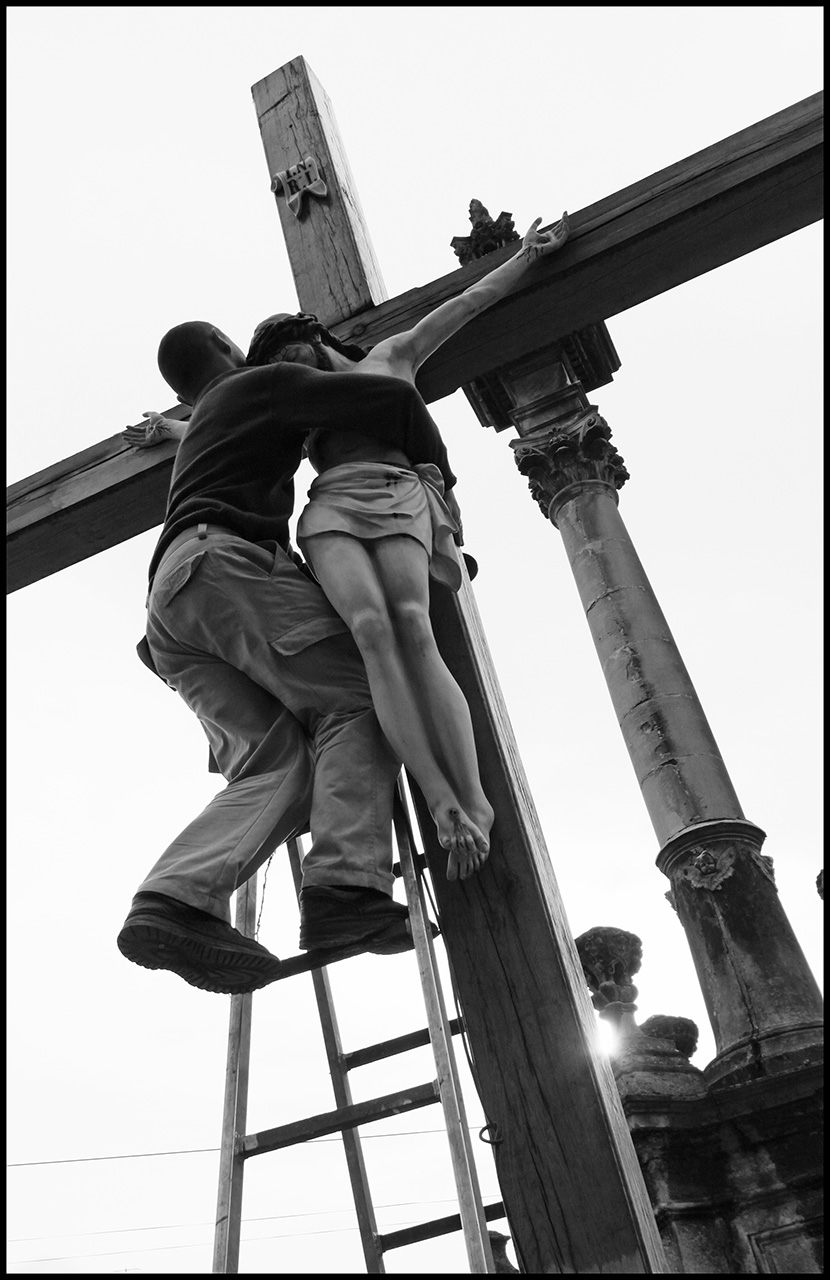

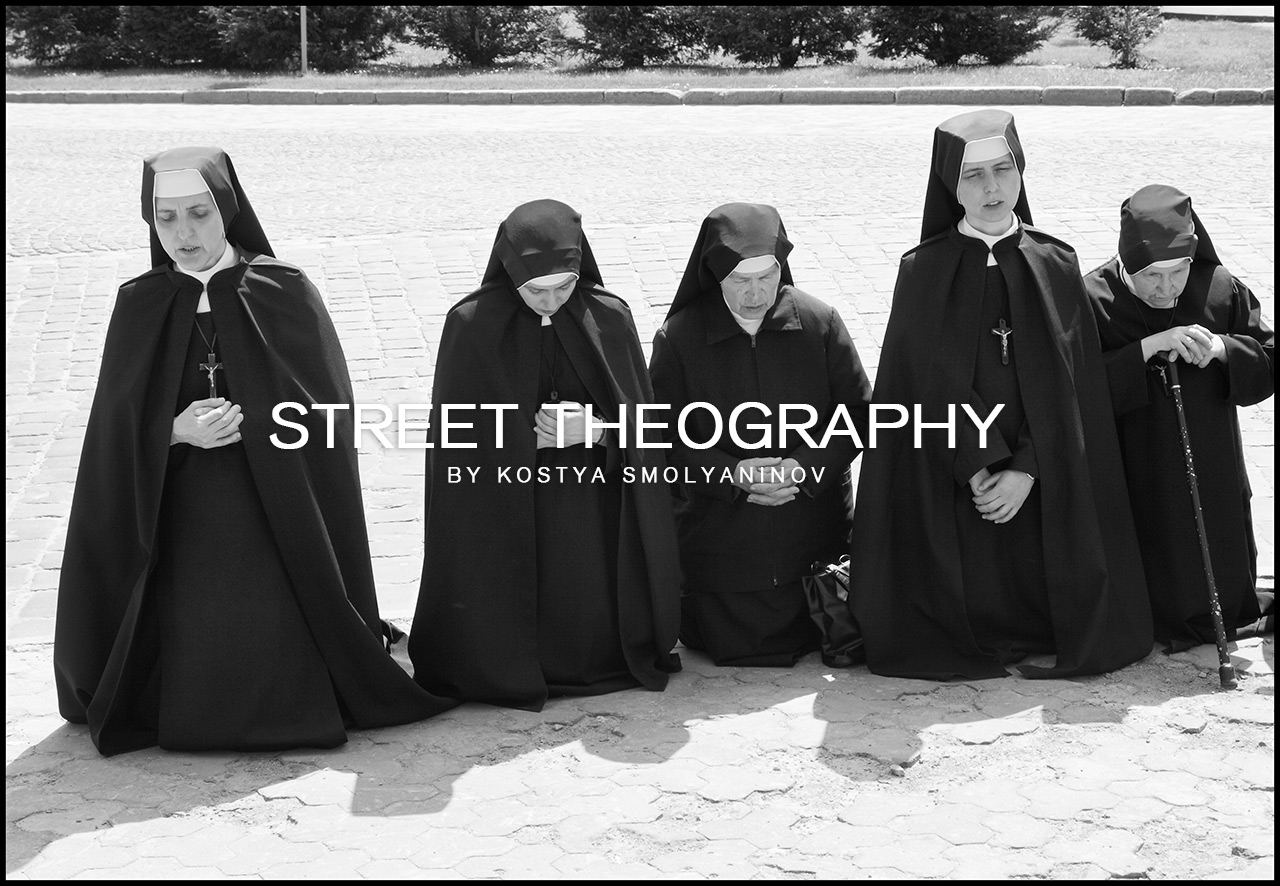

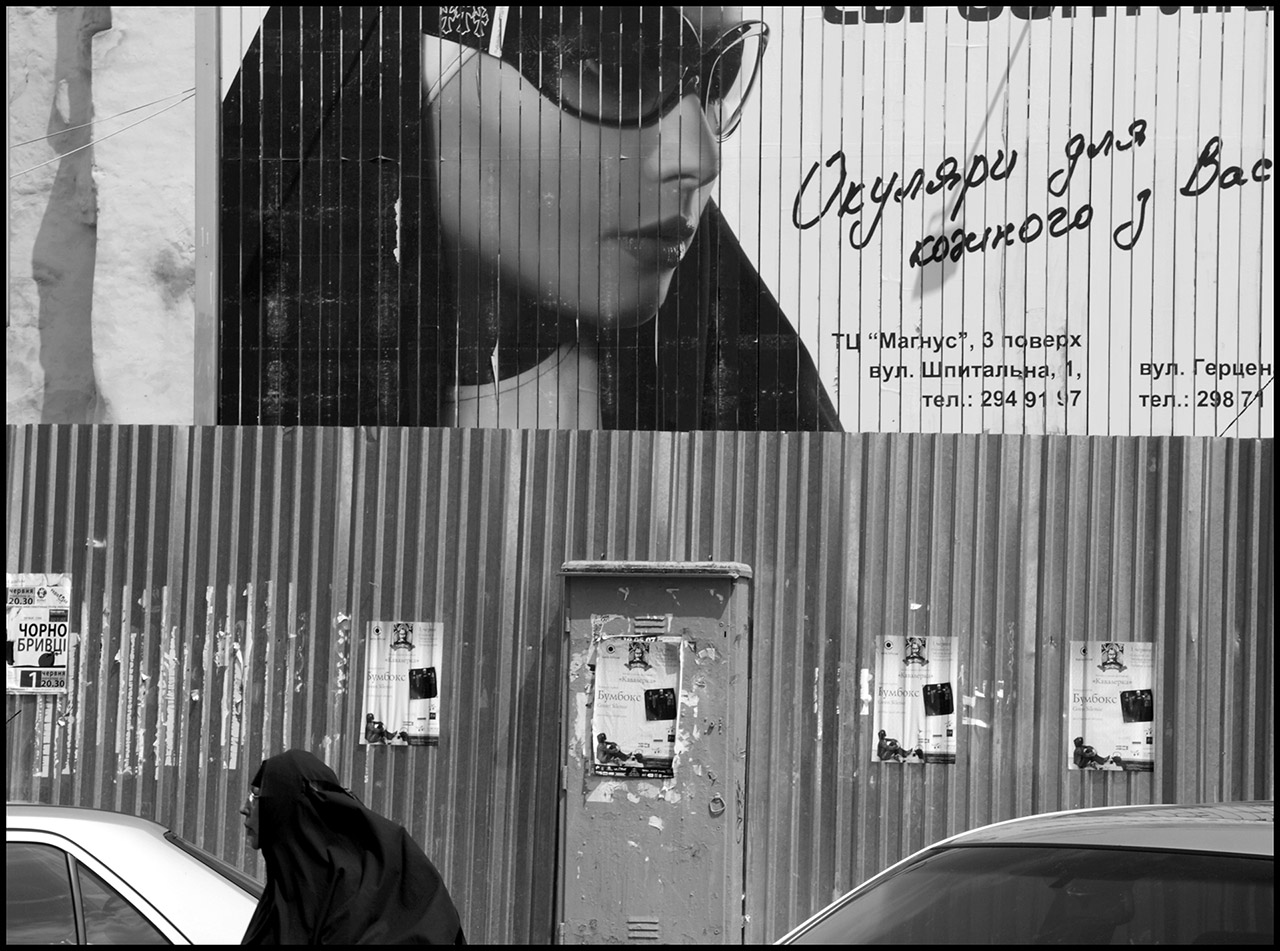

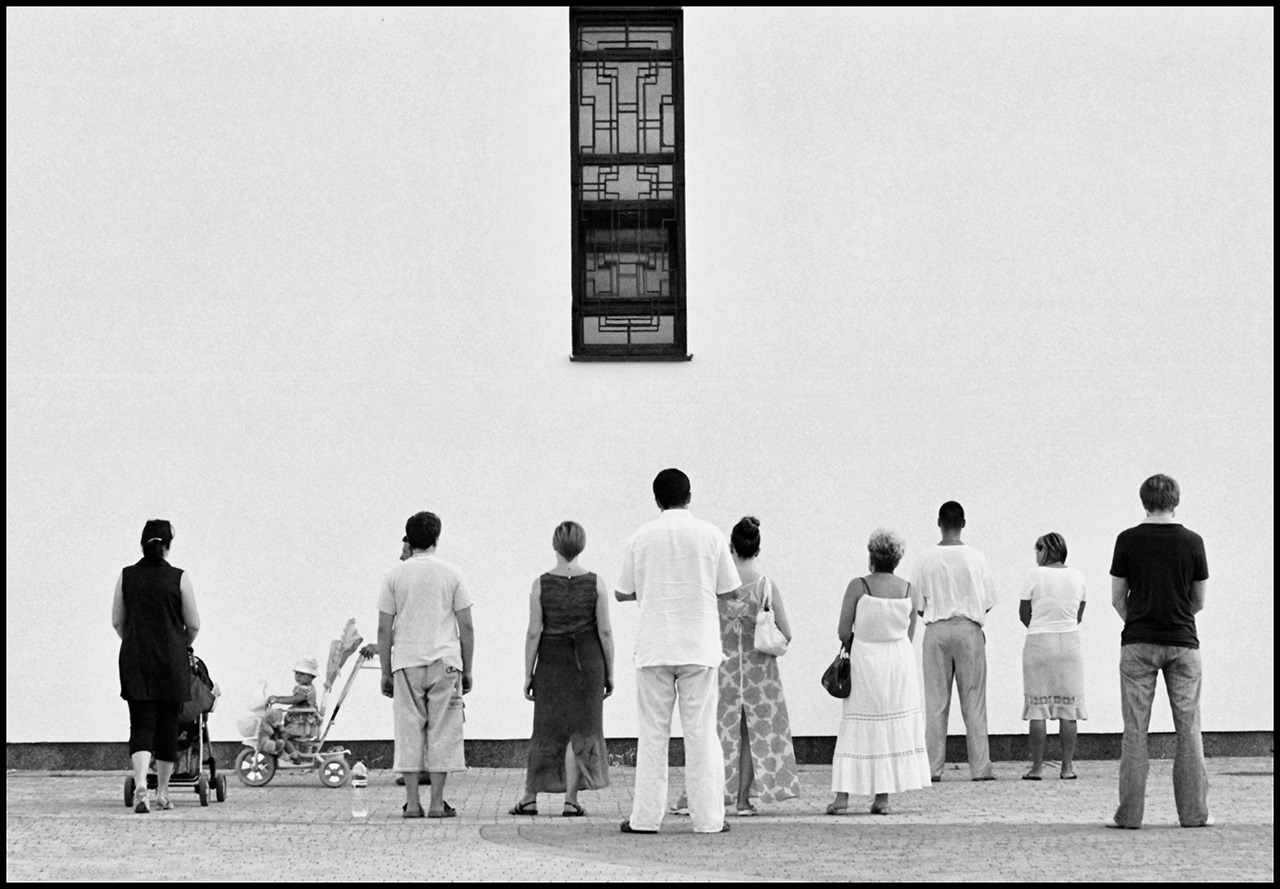

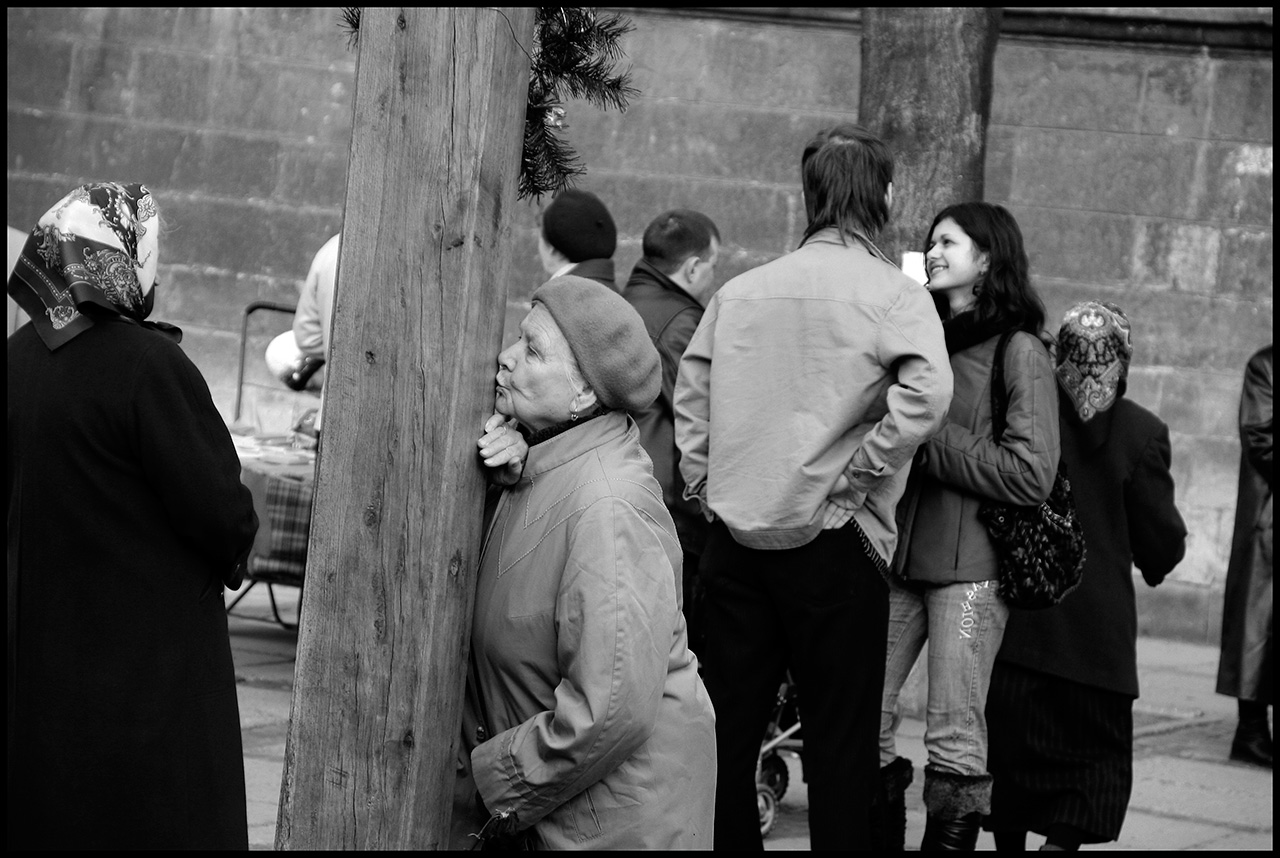

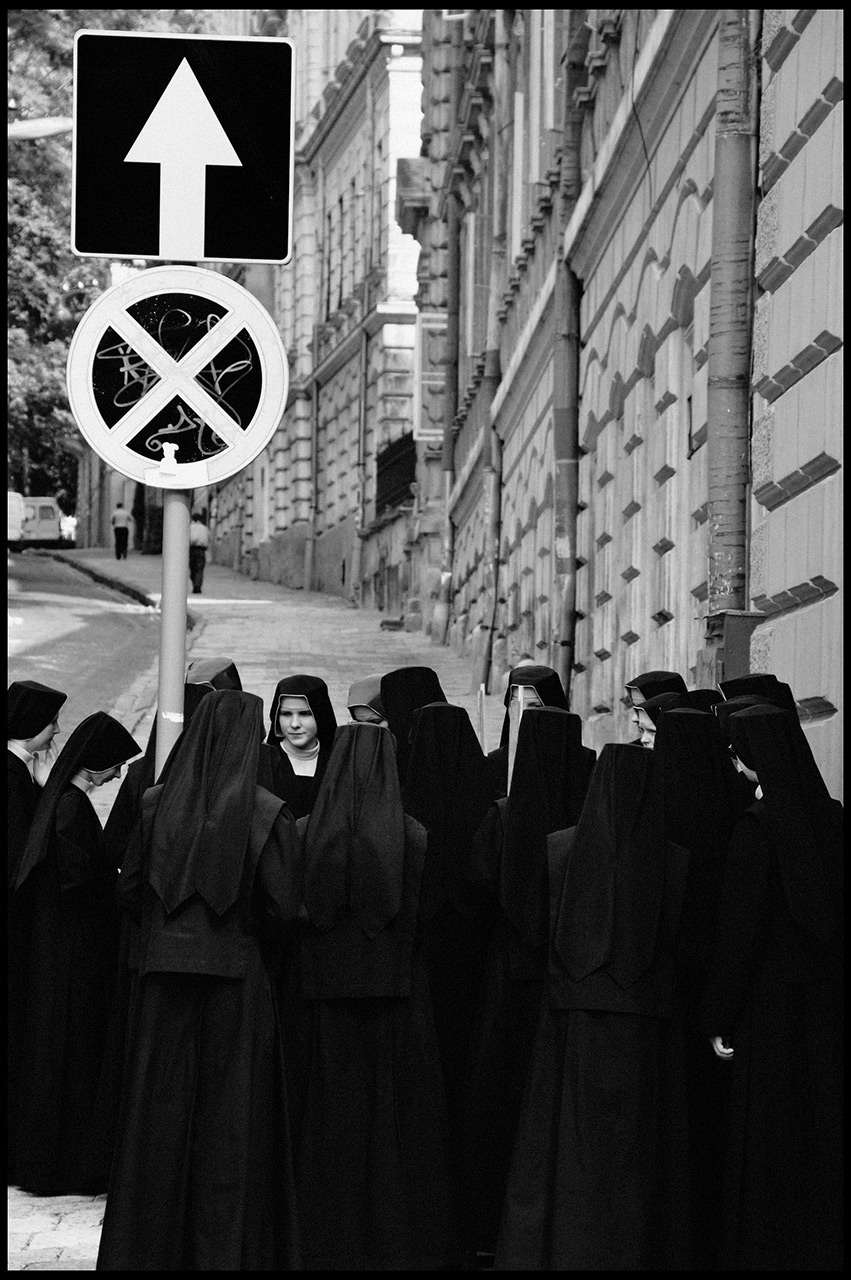

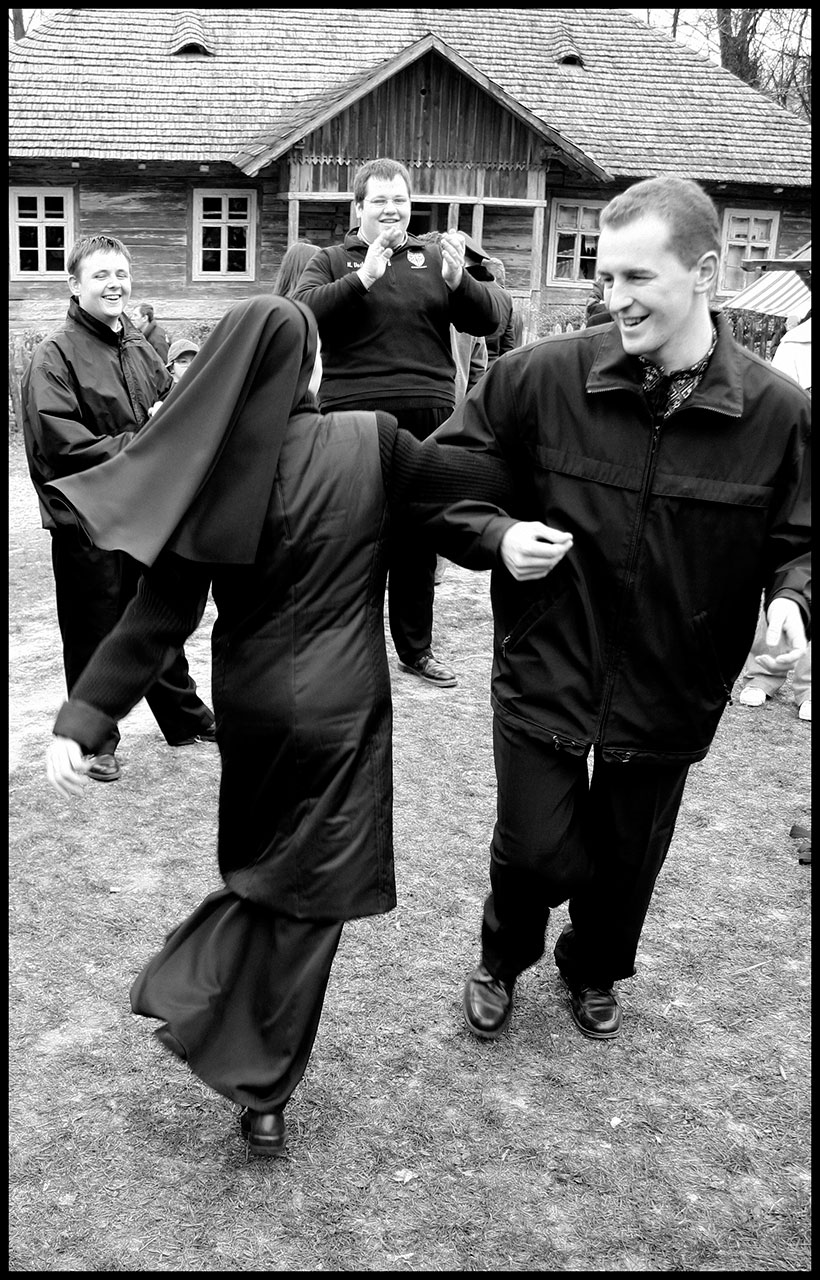

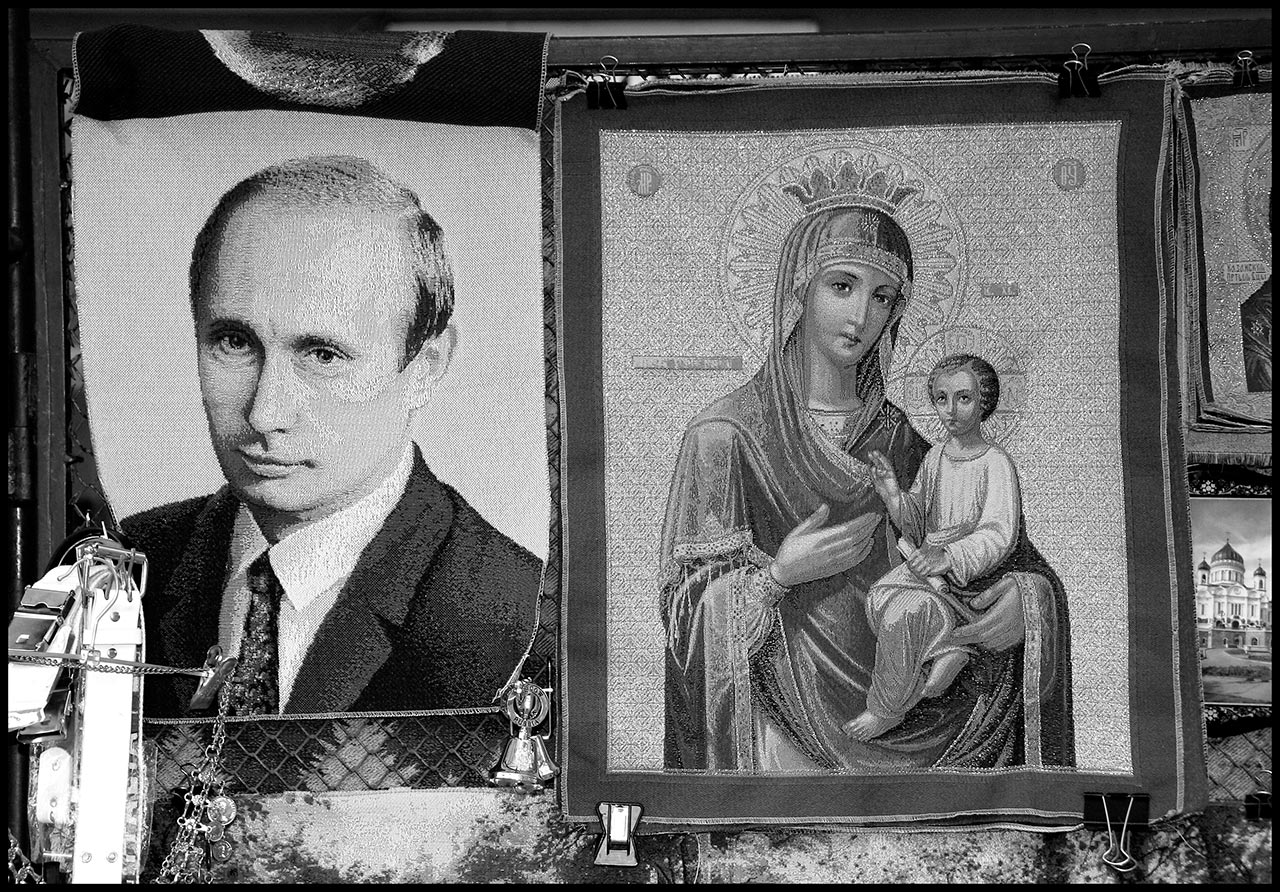

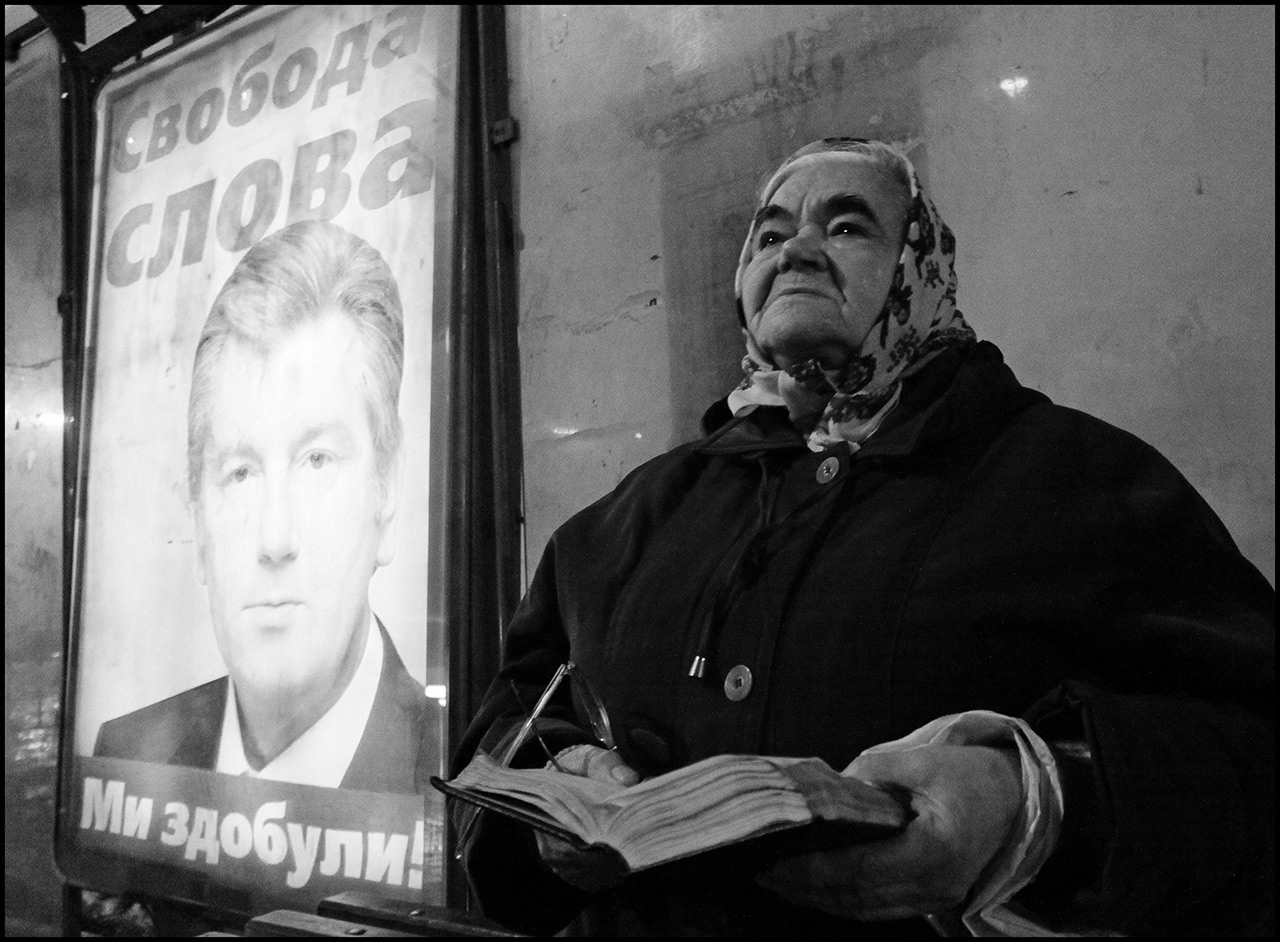

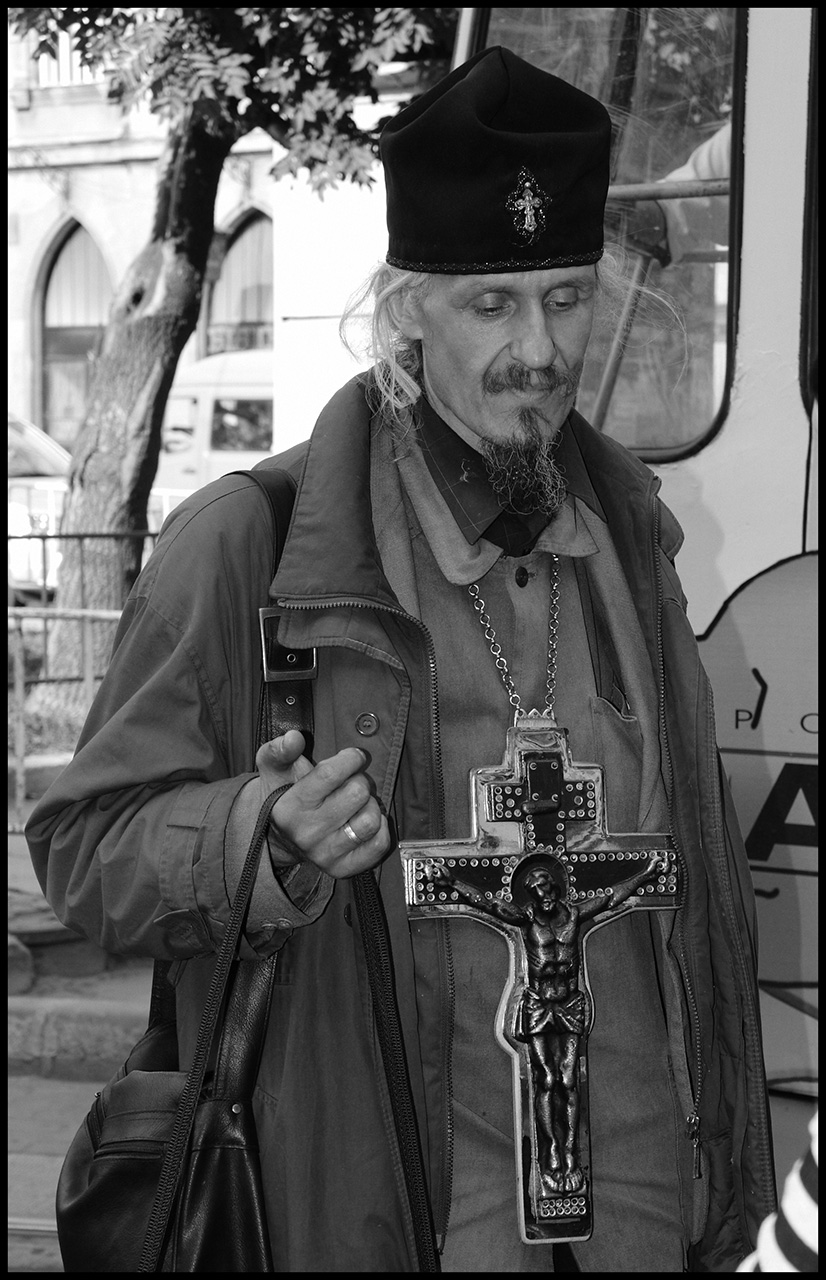

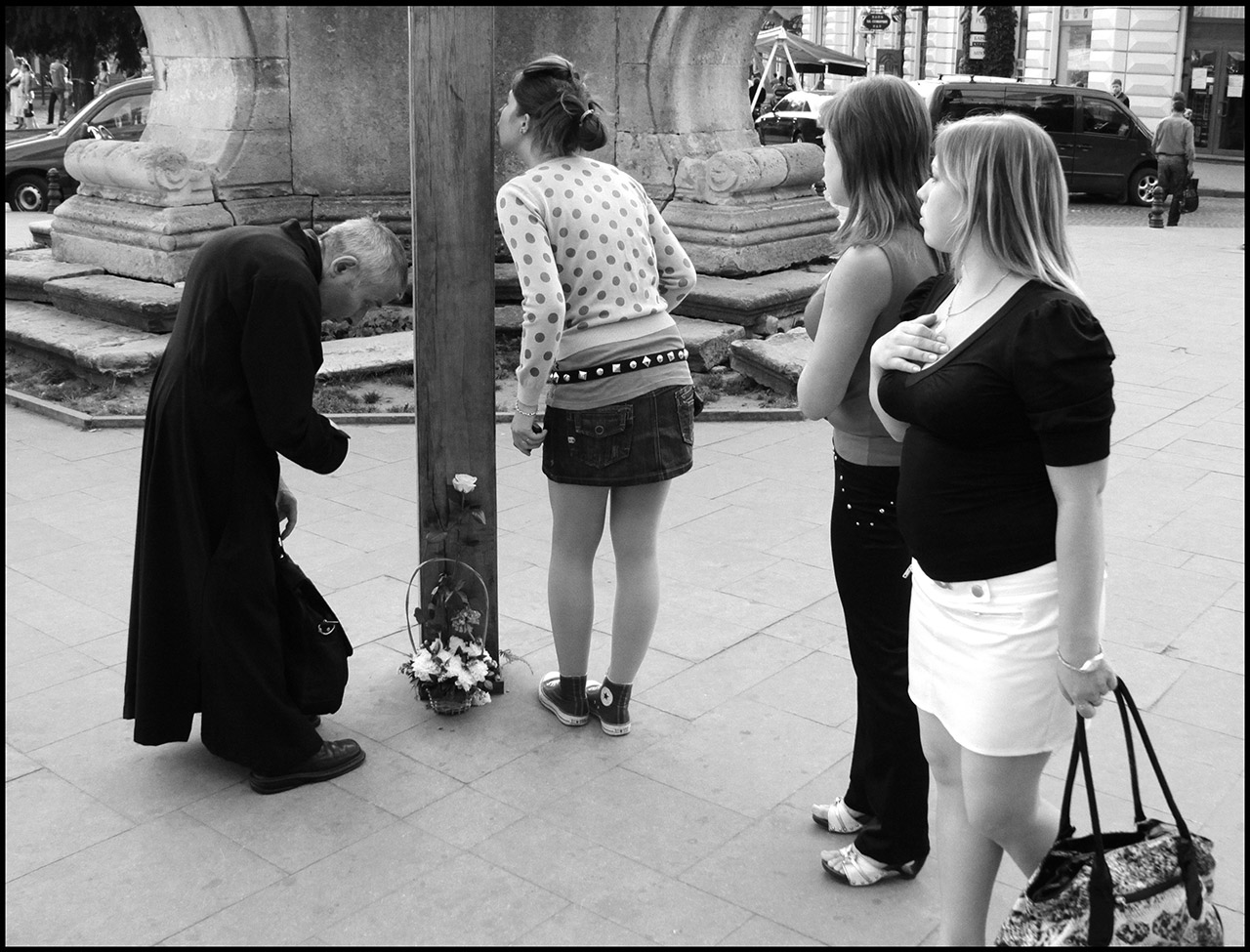

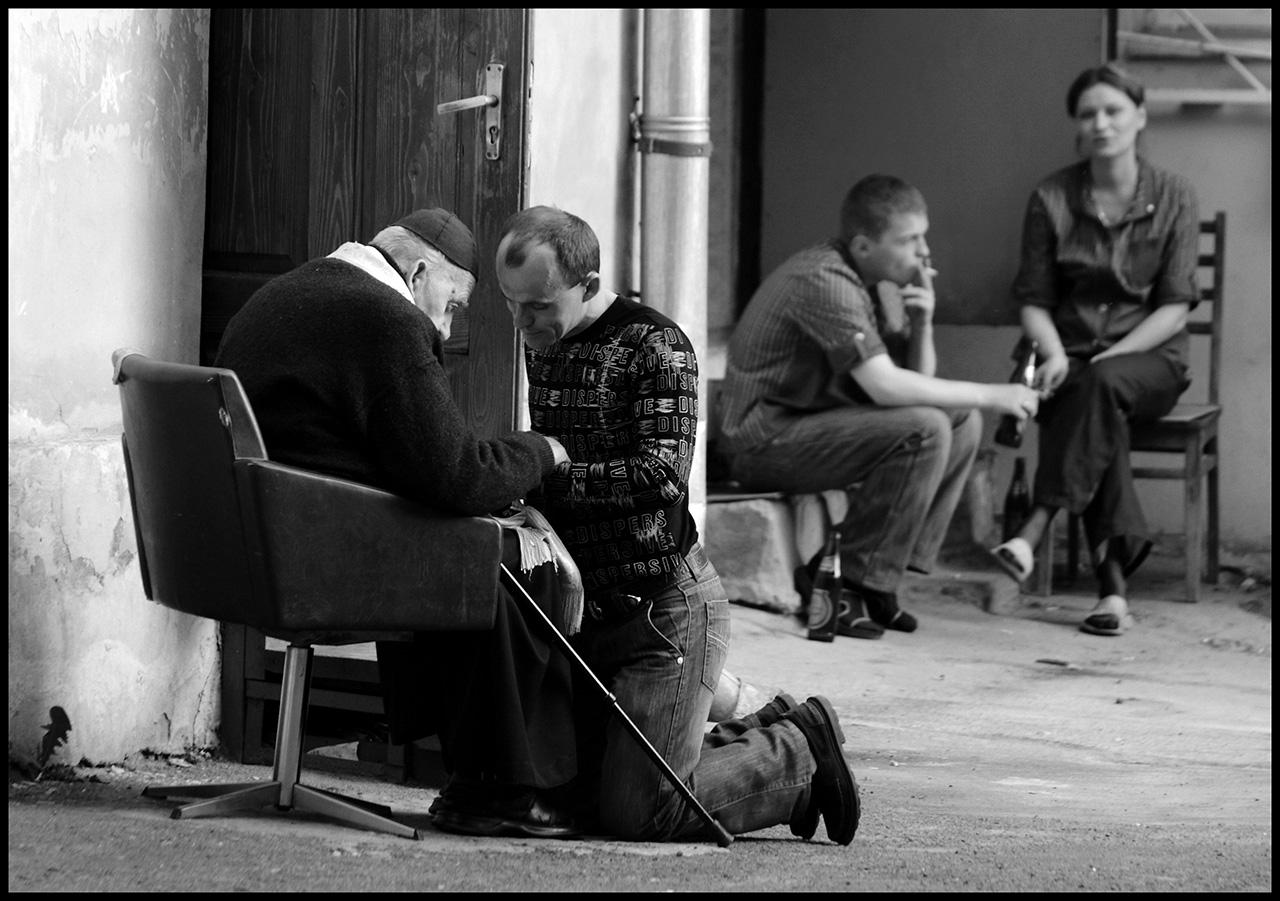

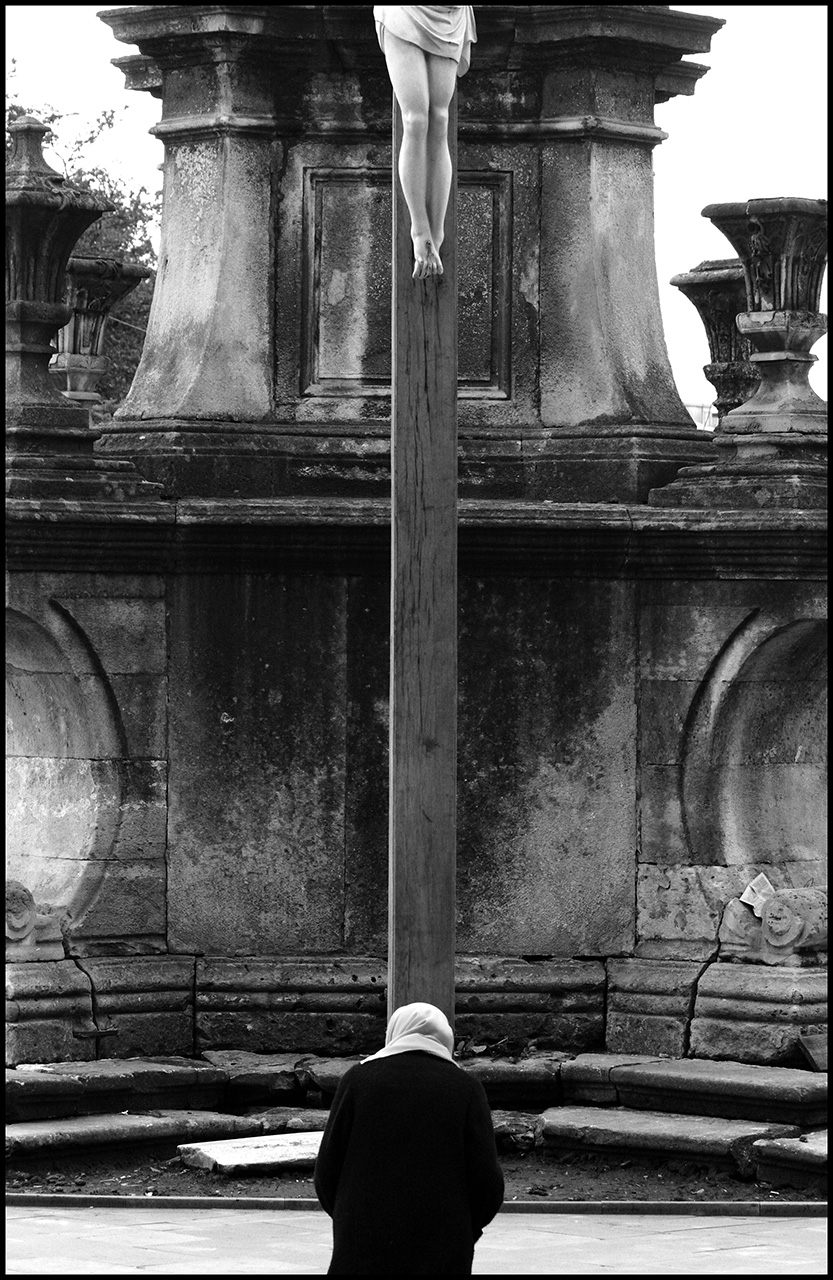

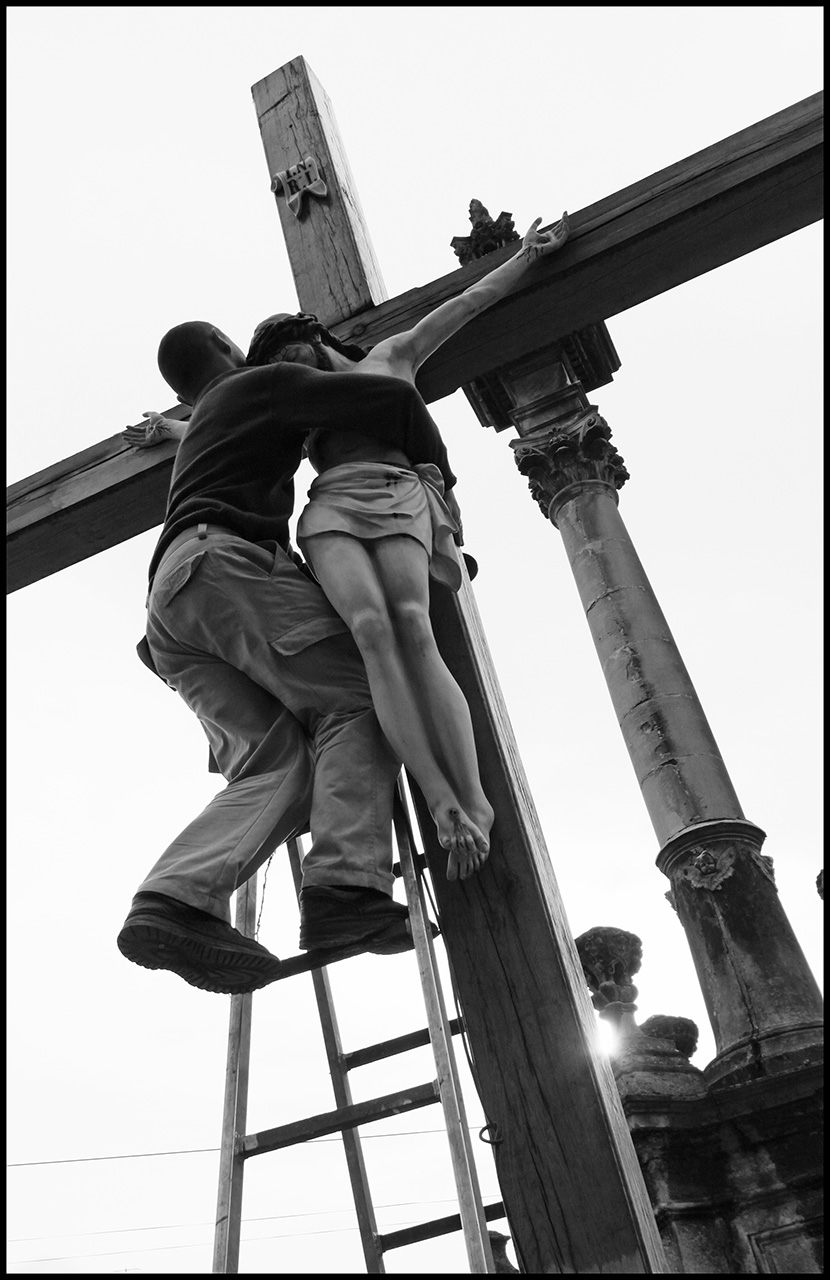

The project Street Theography was created during 2006-2013 in several cities of the Ukraine, Poland and Russia. It is not strange to find people praying in church, but my interest was aroused by the many manifestations of religious feelings in everyday life, on the street. That’s where, during photographic research, I came up with the idea and name for this series. Especially in the street the conflict between the intimate nature of faith and the public, often ostentatious, religiosity strongly appears.

Kostya Smolyaninov (1971). Lives in Lviv, Ukraine. Photographer and curator. Solo Exhibitions: “On Every Street”, Dzyga Flat 35 (Lviv, Ukraine), 2007; “Street Theography”, Fot-Art Gallery (Szczecin, Poland), 2008; “Generation”, Dzyga Gallery (Lviv, Ukraine), 2008; “Street Theography”,Camera Gallery (Kiev, Ukraine), 2009; “Jazz Bez. Intro”, 5х5 (Lviv, Ukraine), 2009; “2” en Art Palace (Lviv, Ukraine), 2010; “Album” en BWA Gallery (Rzesów, Poland), 2011; “Universal Spaces” en Dzyga Gallery (Lviv, Ukraine), 2012; "2" en Camera Gallery (Kiev, Ukraine), 2012.

Kostya Smolyaninov (1971). Lives in Lviv, Ukraine. Photographer and curator. Solo Exhibitions: “On Every Street”, Dzyga Flat 35 (Lviv, Ukraine), 2007; “Street Theography”, Fot-Art Gallery (Szczecin, Poland), 2008; “Generation”, Dzyga Gallery (Lviv, Ukraine), 2008; “Street Theography”,Camera Gallery (Kiev, Ukraine), 2009; “Jazz Bez. Intro”, 5х5 (Lviv, Ukraine), 2009; “2” en Art Palace (Lviv, Ukraine), 2010; “Album” en BWA Gallery (Rzesów, Poland), 2011; “Universal Spaces” en Dzyga Gallery (Lviv, Ukraine), 2012; "2" en Camera Gallery (Kiev, Ukraine), 2012.

The project Street Theography was created during 2006-2013 in several cities of the Ukraine, Poland and Russia. It is not strange to find people praying in church, but my interest was aroused by the many manifestations of religious feelings in everyday life, on the street. That’s where, during photographic research, I came up with the idea and name for this series. Especially in the street the conflict between the intimate nature of faith and the public, often ostentatious, religiosity strongly appears.

Kostya Smolyaninov (1971). Lives in Lviv, Ukraine. Photographer and curator. Solo Exhibitions: “On Every Street”, Dzyga Flat 35 (Lviv, Ukraine), 2007; “Street Theography”, Fot-Art Gallery (Szczecin, Poland), 2008; “Generation”, Dzyga Gallery (Lviv, Ukraine), 2008; “Street Theography”,Camera Gallery (Kiev, Ukraine), 2009; “Jazz Bez. Intro”, 5х5 (Lviv, Ukraine), 2009; “2” en Art Palace (Lviv, Ukraine), 2010; “Album” en BWA Gallery (Rzesów, Poland), 2011; “Universal Spaces” en Dzyga Gallery (Lviv, Ukraine), 2012; "2" en Camera Gallery (Kiev, Ukraine), 2012.

Kostya Smolyaninov (1971). Lives in Lviv, Ukraine. Photographer and curator. Solo Exhibitions: “On Every Street”, Dzyga Flat 35 (Lviv, Ukraine), 2007; “Street Theography”, Fot-Art Gallery (Szczecin, Poland), 2008; “Generation”, Dzyga Gallery (Lviv, Ukraine), 2008; “Street Theography”,Camera Gallery (Kiev, Ukraine), 2009; “Jazz Bez. Intro”, 5х5 (Lviv, Ukraine), 2009; “2” en Art Palace (Lviv, Ukraine), 2010; “Album” en BWA Gallery (Rzesów, Poland), 2011; “Universal Spaces” en Dzyga Gallery (Lviv, Ukraine), 2012; "2" en Camera Gallery (Kiev, Ukraine), 2012.ZoneZero

Interview with Virgil Widrich about his work. February 2015

Virgil Widrich (Salzburg, 1967). Lives in Vienna. He works on numerous multimedia and film productions. His first feature film is Heller als der Mond (Brighter than the Moon). His short film Copy Shop won 35 international awards and was nominated for the Oscar. Fast Film premiered in Cannes 2003 and won 36 awards until today. At the moment Widrich is working on a new feature film The Night of a Thousand Hours.

Virgil Widrich (Salzburg, 1967). Lives in Vienna. He works on numerous multimedia and film productions. His first feature film is Heller als der Mond (Brighter than the Moon). His short film Copy Shop won 35 international awards and was nominated for the Oscar. Fast Film premiered in Cannes 2003 and won 36 awards until today. At the moment Widrich is working on a new feature film The Night of a Thousand Hours.Interview with Virgil Widrich about his work. February 2015

Virgil Widrich (Salzburg, 1967). Lives in Vienna. He works on numerous multimedia and film productions. His first feature film is Heller als der Mond (Brighter than the Moon). His short film Copy Shop won 35 international awards and was nominated for the Oscar. Fast Film premiered in Cannes 2003 and won 36 awards until today. At the moment Widrich is working on a new feature film The Night of a Thousand Hours.

Virgil Widrich (Salzburg, 1967). Lives in Vienna. He works on numerous multimedia and film productions. His first feature film is Heller als der Mond (Brighter than the Moon). His short film Copy Shop won 35 international awards and was nominated for the Oscar. Fast Film premiered in Cannes 2003 and won 36 awards until today. At the moment Widrich is working on a new feature film The Night of a Thousand Hours.Alvaro Deprit

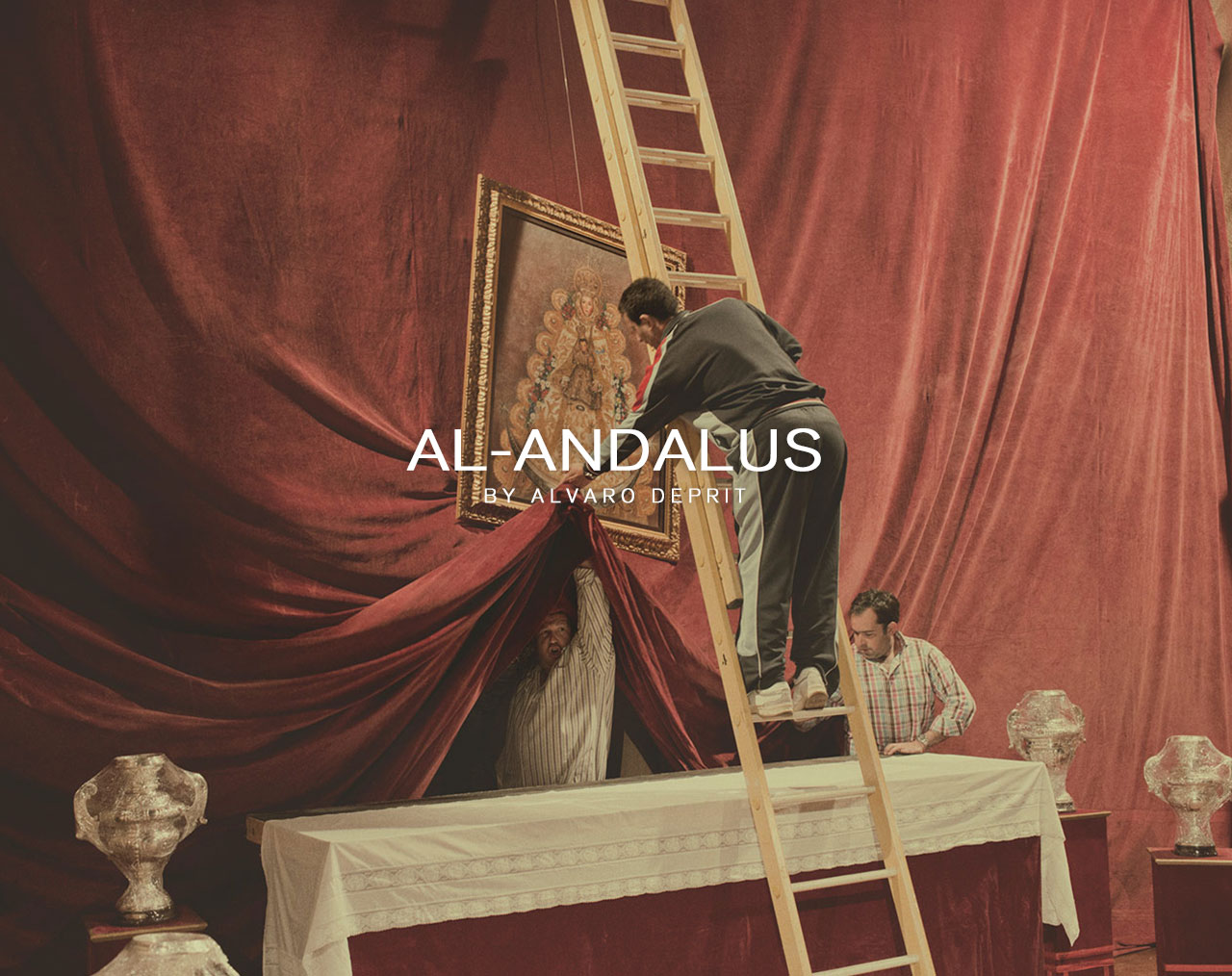

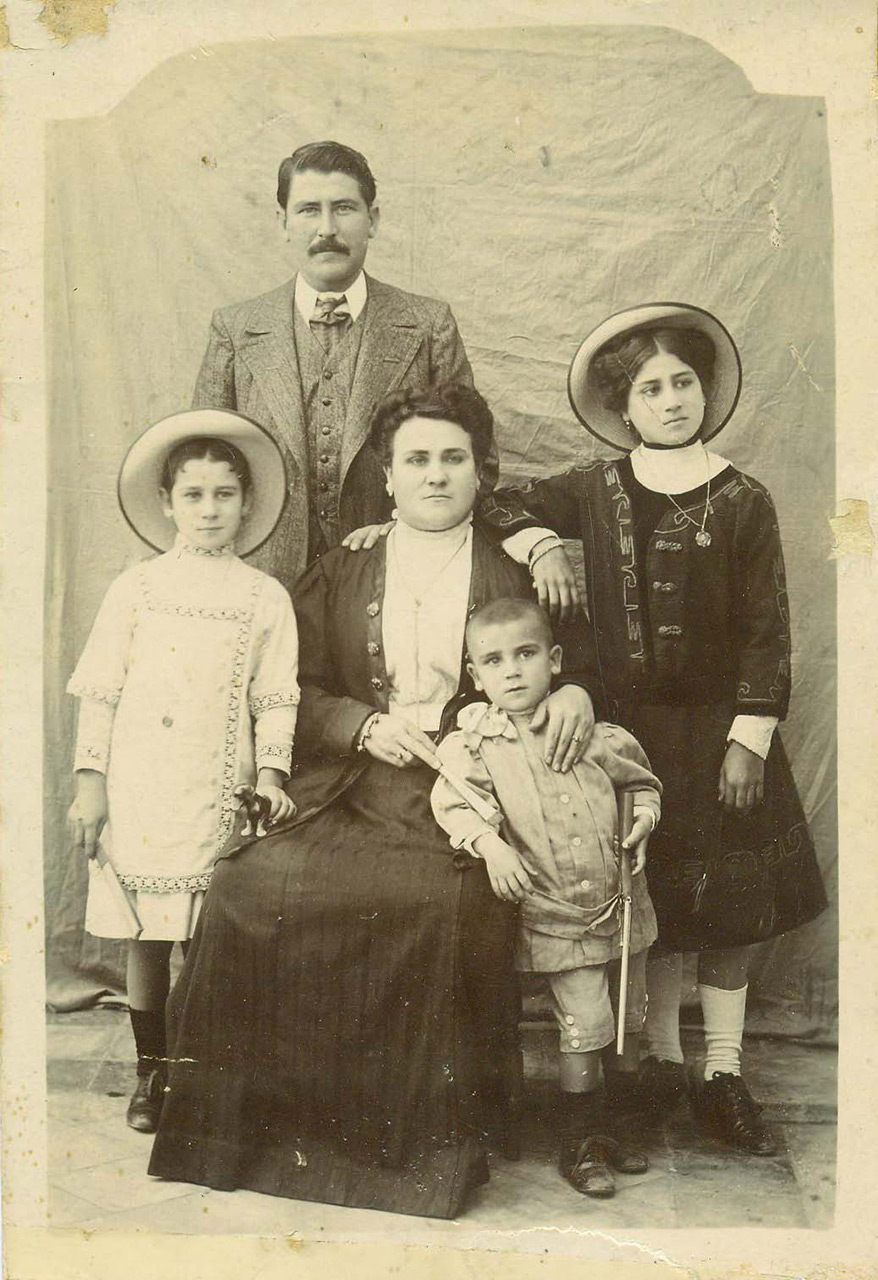

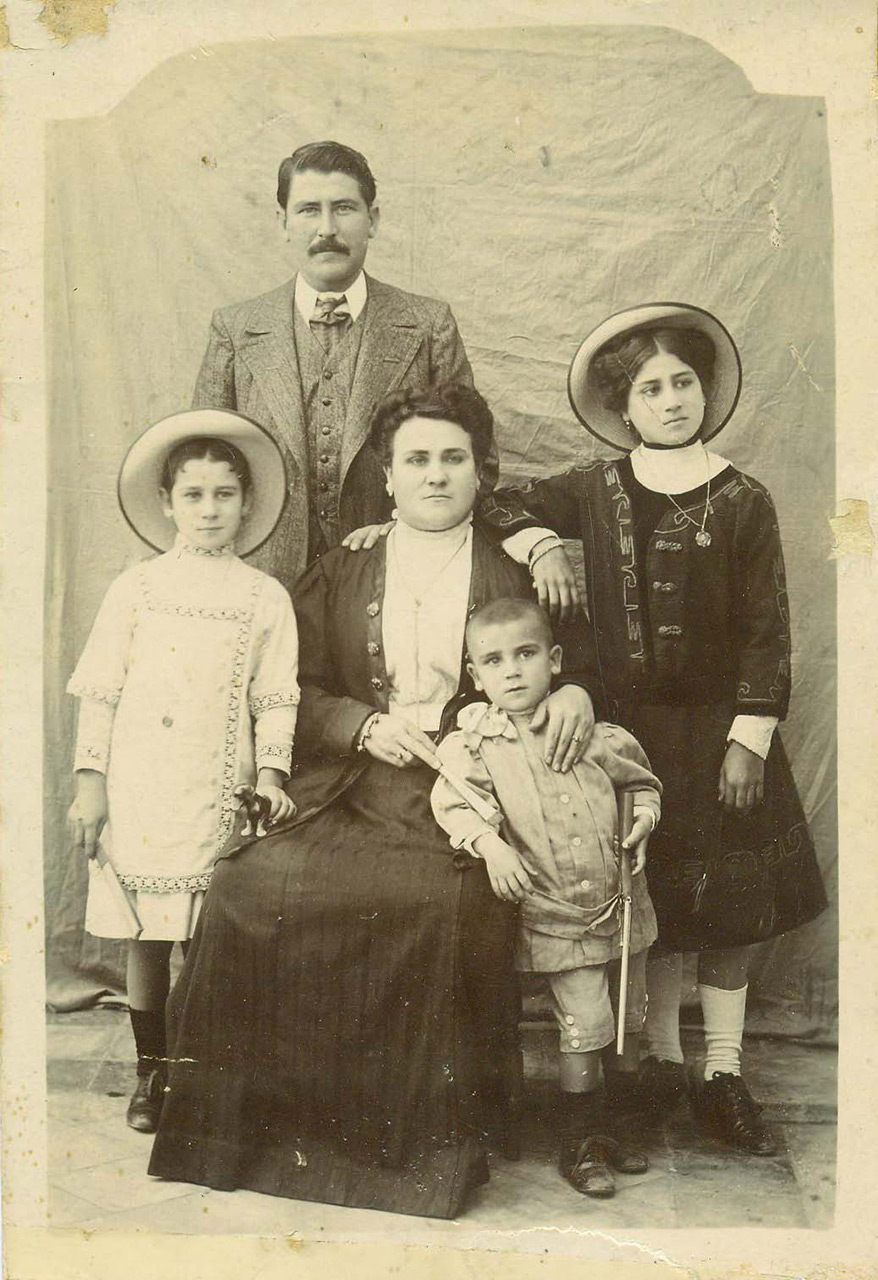

At home I always used to linger with curiosity at an old photograph of some of my Andalusian relatives. With the passing of years this photograph has given me an image of how I think Andalusia might be.

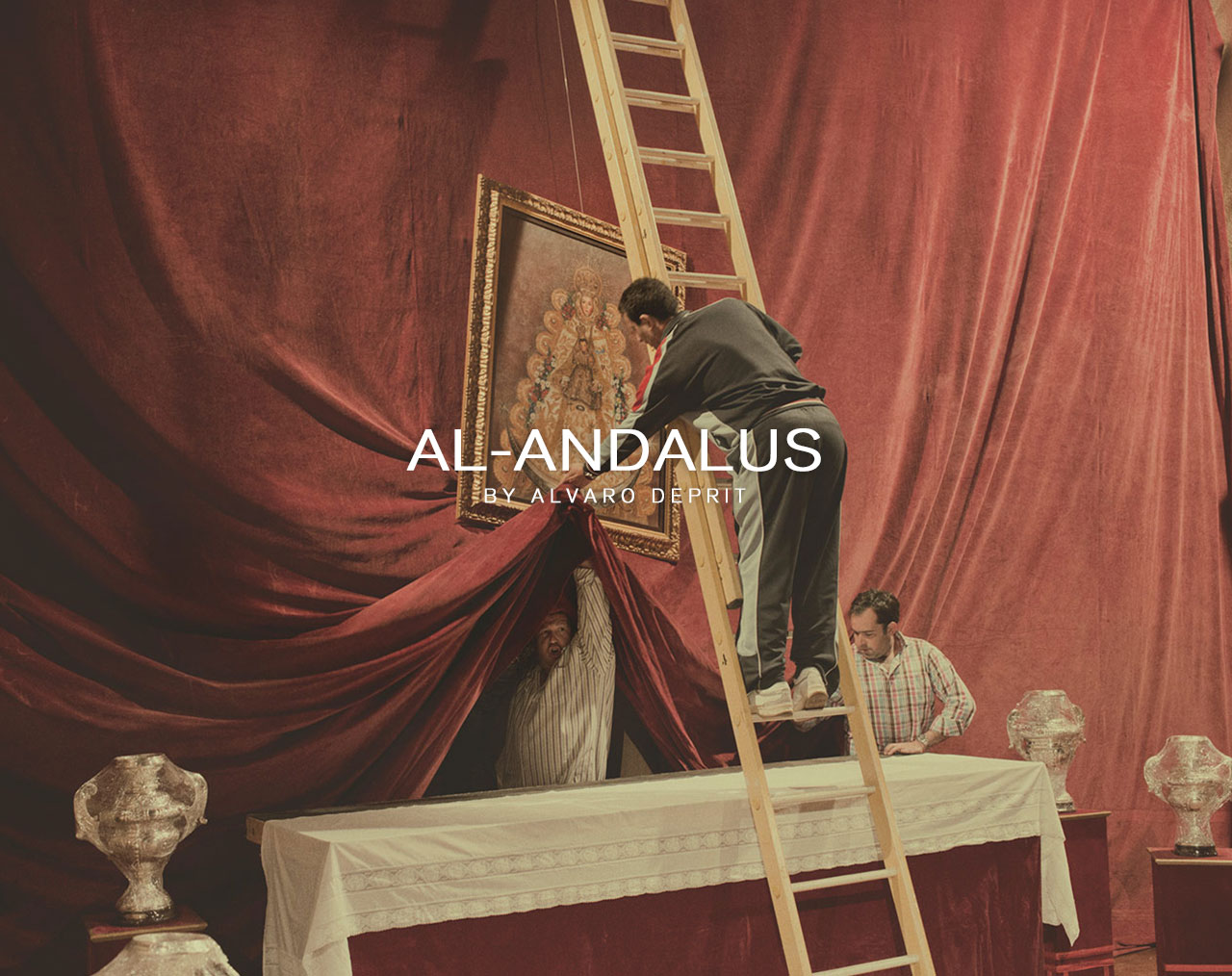

Al-Andalus is the result of approximately three years of research in the south of Spain, an area I did not know nor in which I have lived, but which is my family’s place of origin and current place of residence.

My initial interest was in the tension I perceived between tradition and the marks of the global world. Andalusia is the result of a complex cultural stratification, derived from the passage of civilisations which, over time, gave life to a hybrid identity capable of containing within it the stereotypical traits of Spanish culture.

Journeying through Andalusia now that it has been hit hard by the economic crisis has made me reflect on the collision of the diverse elements in this land – a land which, as I see it, has shown itself to be hanging in the balance, almost in a state between reality and fiction as the background of a movie.

My intention has not been to reproduce the tangible aspects of a place, but to give shape to a body of memories and impressions born of my personal history or of something unconcluded. Concentrated in the images are visible apparitions whose existence is a mystery, while on the other hand, the mystery is something real in the mind, through the repeating, varying, developing and transposing elements of the memory.

Alvaro Deprit (Madrid). Has been living in Italy since 2004. He studied German Philology at the Complutense University of Madrid and at the Otto Friedrich University of Bamberg, Germany. He also studied Sociology at the University d’Annunzio in Chieti, Italy. Alvaro’s work has been exhibited in festivals and galleries all over the world and has been published in international magazines. He won the PHotoEspaña OjodePez Human Values Award, the BJP’s International Photography Award and the Viewbook Photostory Contest, and he was a finalist in Voies Off Arles, Leica Oskar Barnack Award and Sony Award.

Alvaro Deprit (Madrid). Has been living in Italy since 2004. He studied German Philology at the Complutense University of Madrid and at the Otto Friedrich University of Bamberg, Germany. He also studied Sociology at the University d’Annunzio in Chieti, Italy. Alvaro’s work has been exhibited in festivals and galleries all over the world and has been published in international magazines. He won the PHotoEspaña OjodePez Human Values Award, the BJP’s International Photography Award and the Viewbook Photostory Contest, and he was a finalist in Voies Off Arles, Leica Oskar Barnack Award and Sony Award.

At home I always used to linger with curiosity at an old photograph of some of my Andalusian relatives. With the passing of years this photograph has given me an image of how I think Andalusia might be.

Al-Andalus is the result of approximately three years of research in the south of Spain, an area I did not know nor in which I have lived, but which is my family’s place of origin and current place of residence.

My initial interest was in the tension I perceived between tradition and the marks of the global world. Andalusia is the result of a complex cultural stratification, derived from the passage of civilisations which, over time, gave life to a hybrid identity capable of containing within it the stereotypical traits of Spanish culture.

Journeying through Andalusia now that it has been hit hard by the economic crisis has made me reflect on the collision of the diverse elements in this land – a land which, as I see it, has shown itself to be hanging in the balance, almost in a state between reality and fiction as the background of a movie.

My intention has not been to reproduce the tangible aspects of a place, but to give shape to a body of memories and impressions born of my personal history or of something unconcluded. Concentrated in the images are visible apparitions whose existence is a mystery, while on the other hand, the mystery is something real in the mind, through the repeating, varying, developing and transposing elements of the memory.

Alvaro Deprit (Madrid). Has been living in Italy since 2004. He studied German Philology at the Complutense University of Madrid and at the Otto Friedrich University of Bamberg, Germany. He also studied Sociology at the University d’Annunzio in Chieti, Italy. Alvaro’s work has been exhibited in festivals and galleries all over the world and has been published in international magazines. He won the PHotoEspaña OjodePez Human Values Award, the BJP’s International Photography Award and the Viewbook Photostory Contest, and he was a finalist in Voies Off Arles, Leica Oskar Barnack Award and Sony Award.

Alvaro Deprit (Madrid). Has been living in Italy since 2004. He studied German Philology at the Complutense University of Madrid and at the Otto Friedrich University of Bamberg, Germany. He also studied Sociology at the University d’Annunzio in Chieti, Italy. Alvaro’s work has been exhibited in festivals and galleries all over the world and has been published in international magazines. He won the PHotoEspaña OjodePez Human Values Award, the BJP’s International Photography Award and the Viewbook Photostory Contest, and he was a finalist in Voies Off Arles, Leica Oskar Barnack Award and Sony Award.Kent Krugh

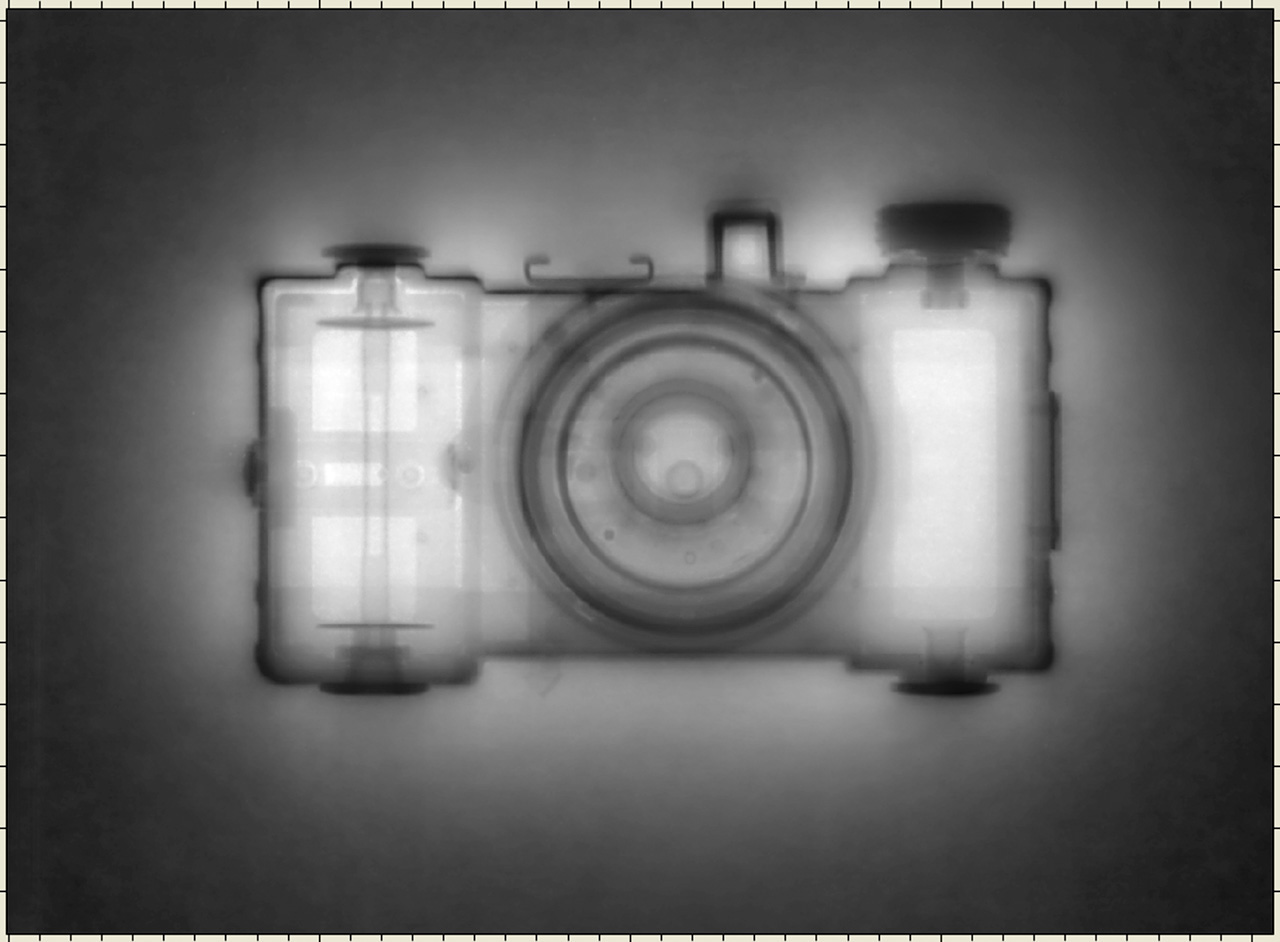

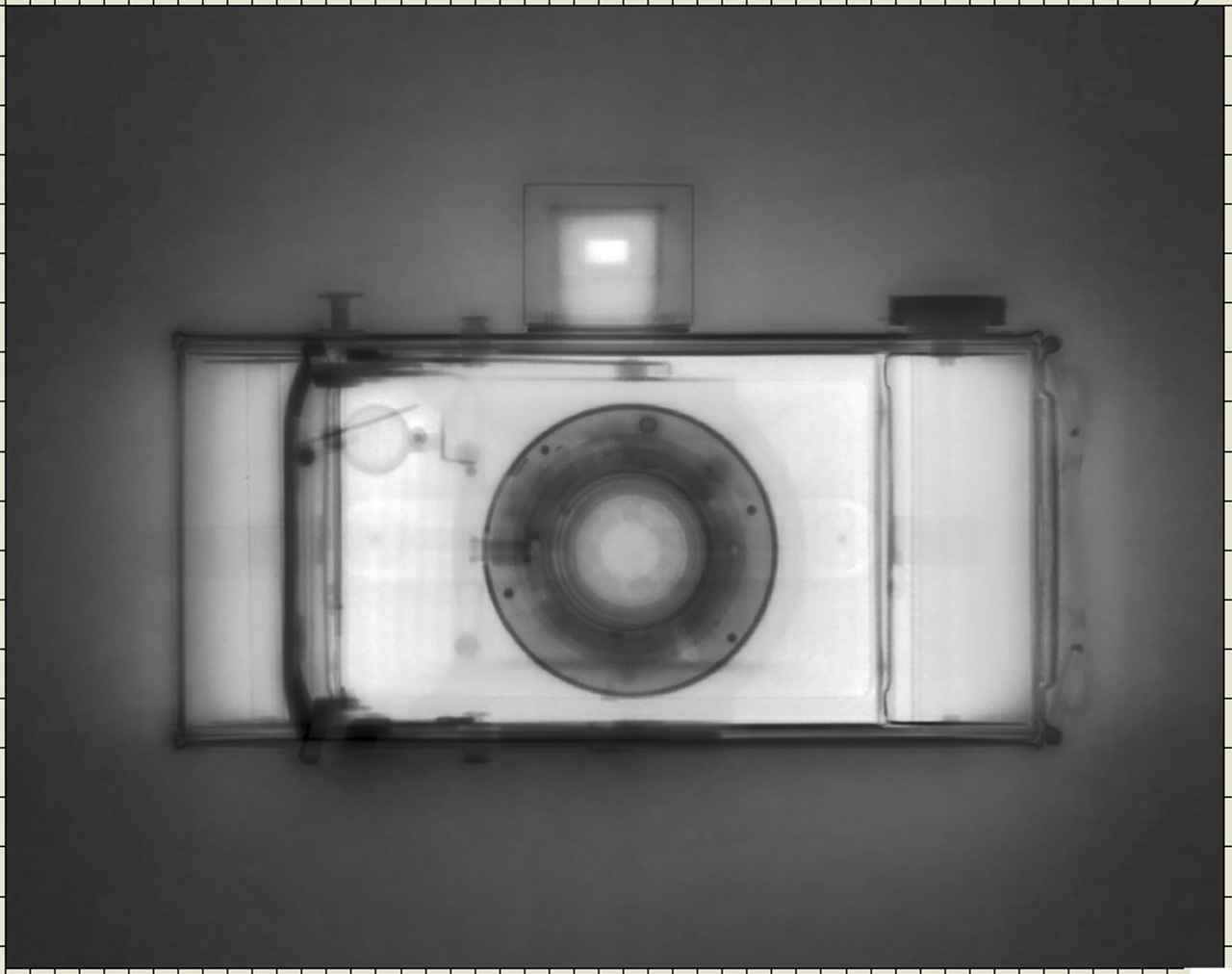

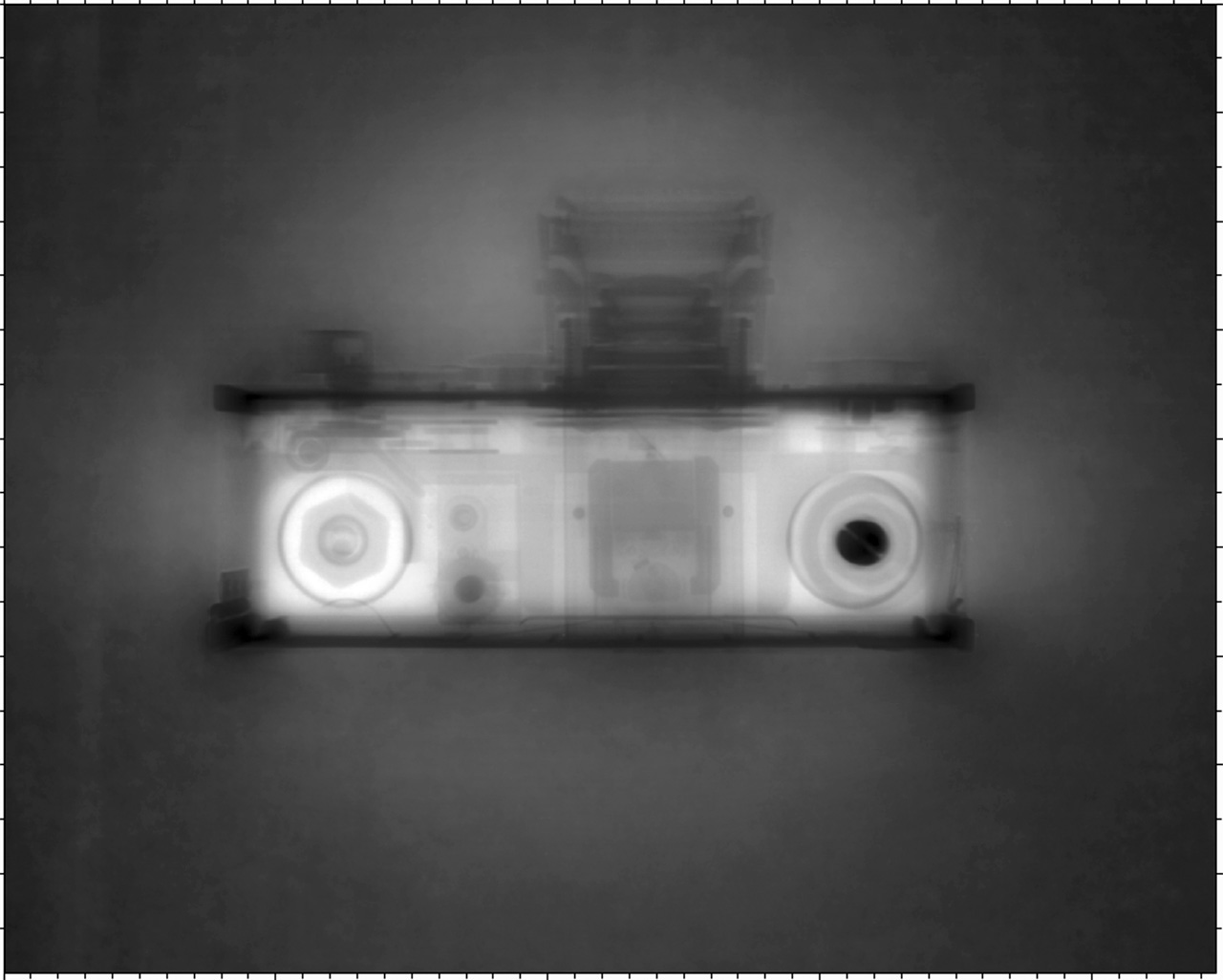

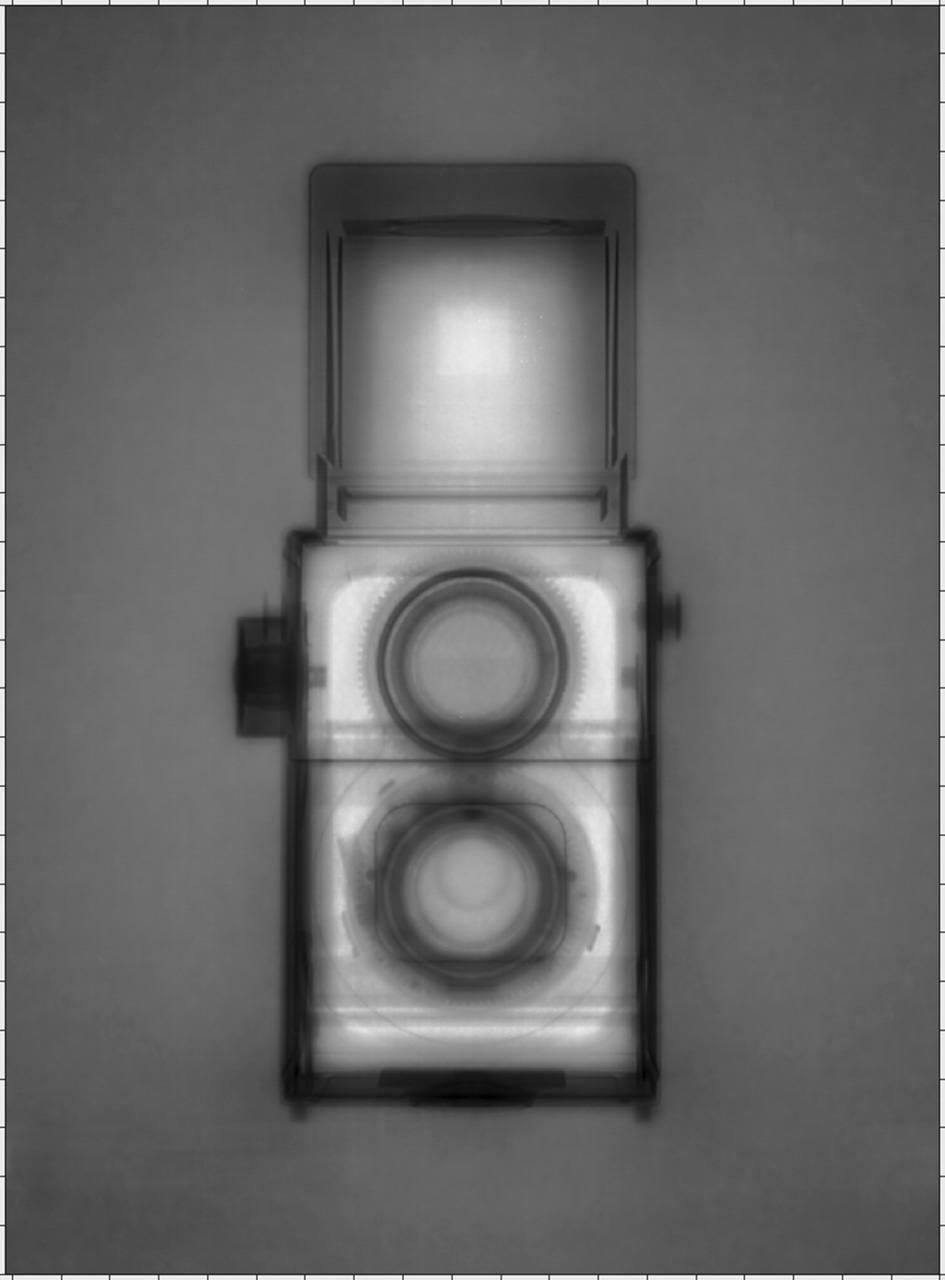

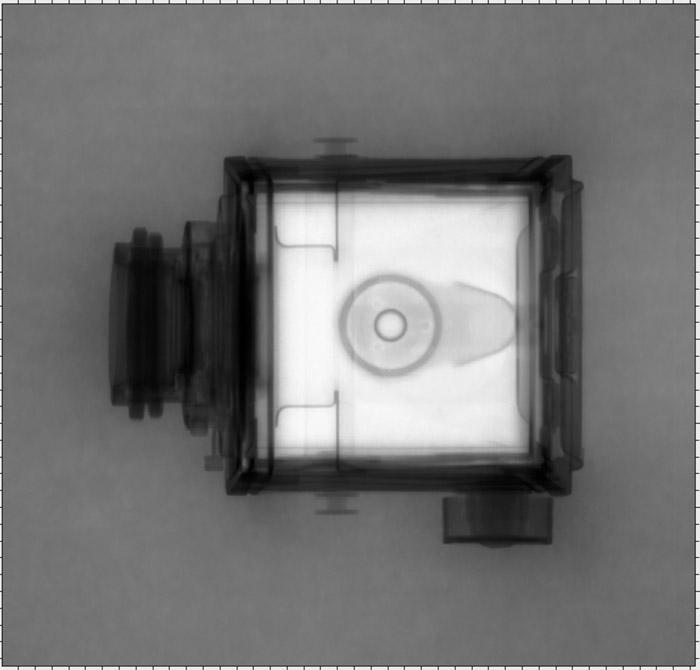

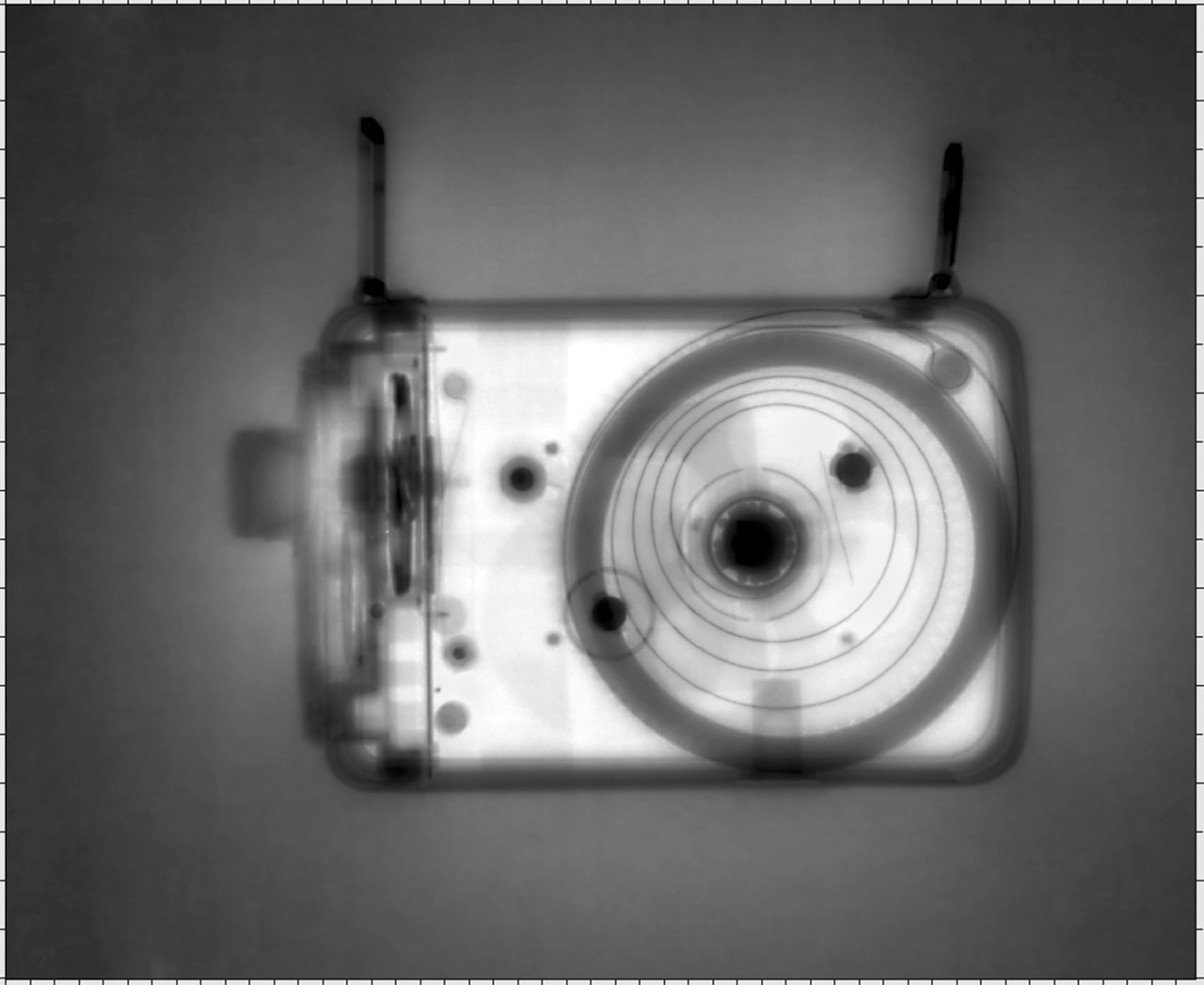

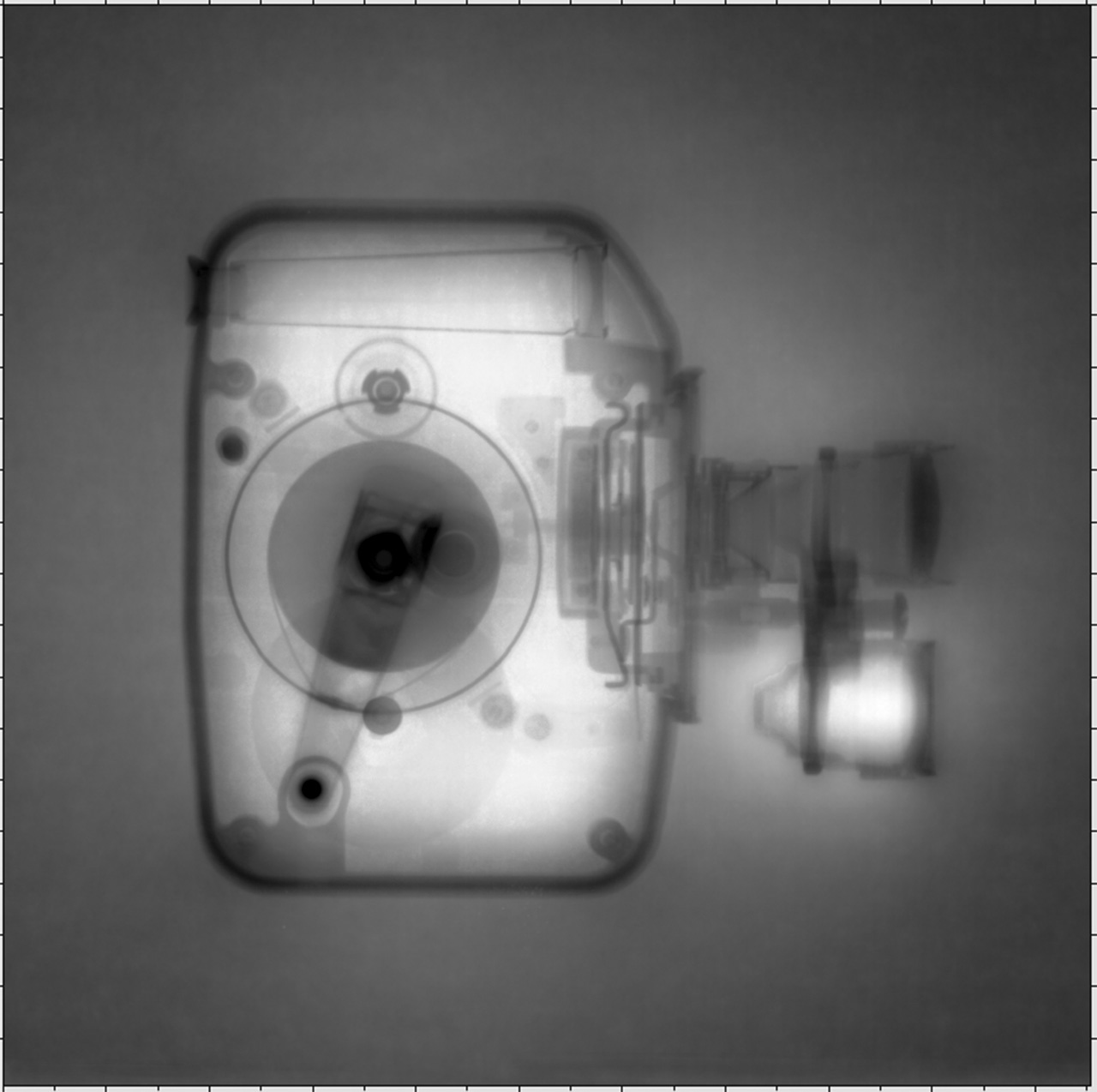

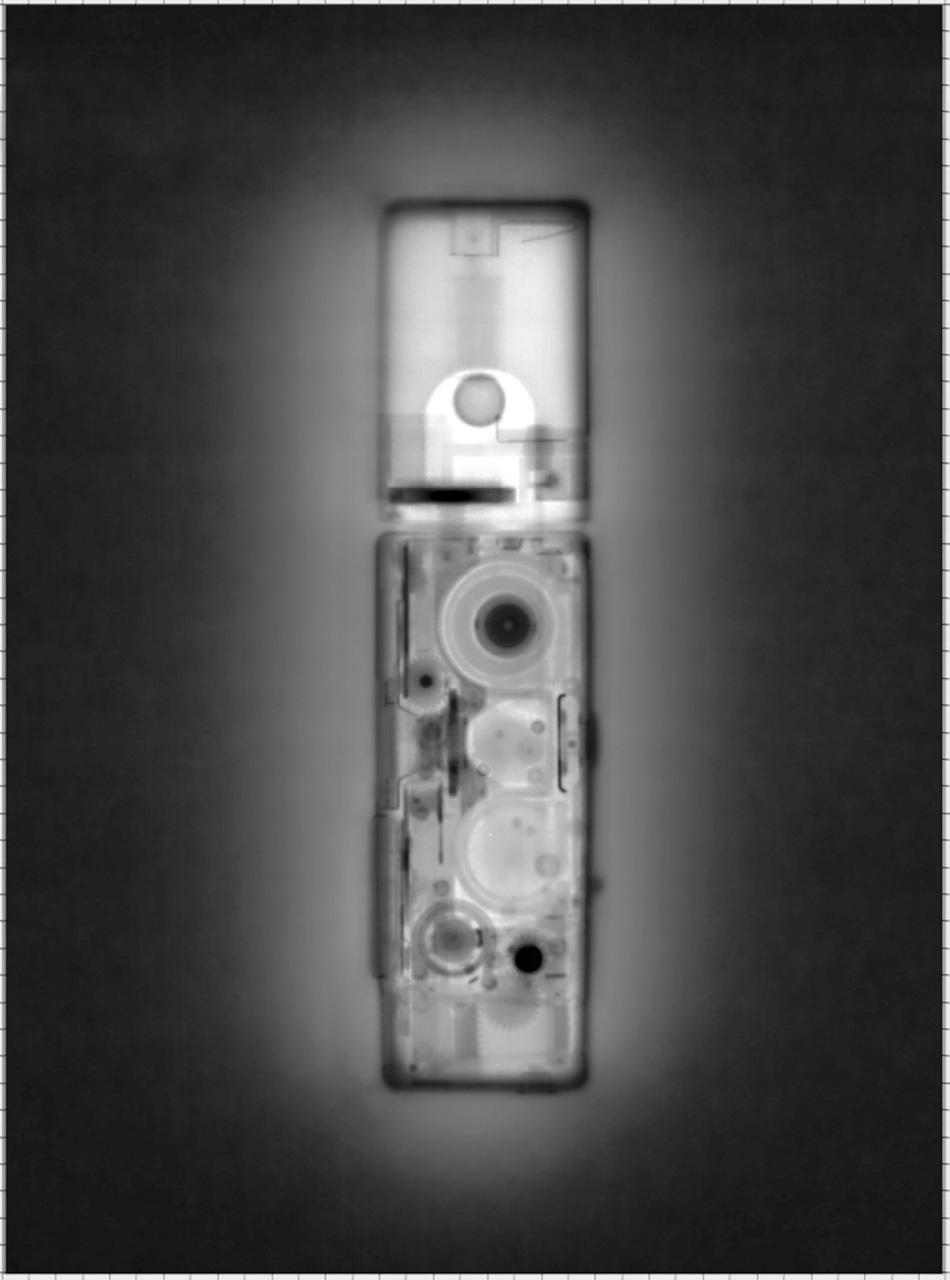

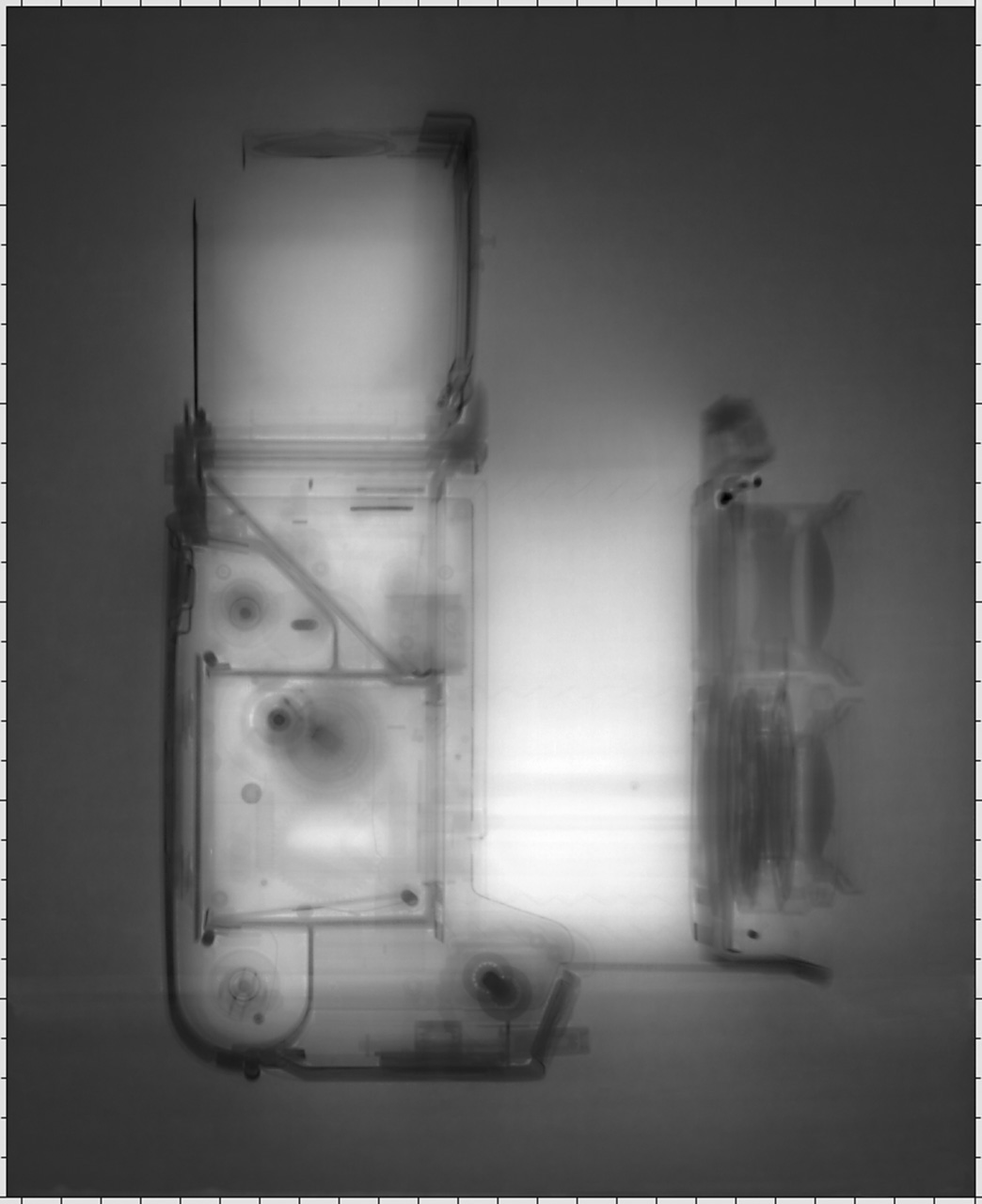

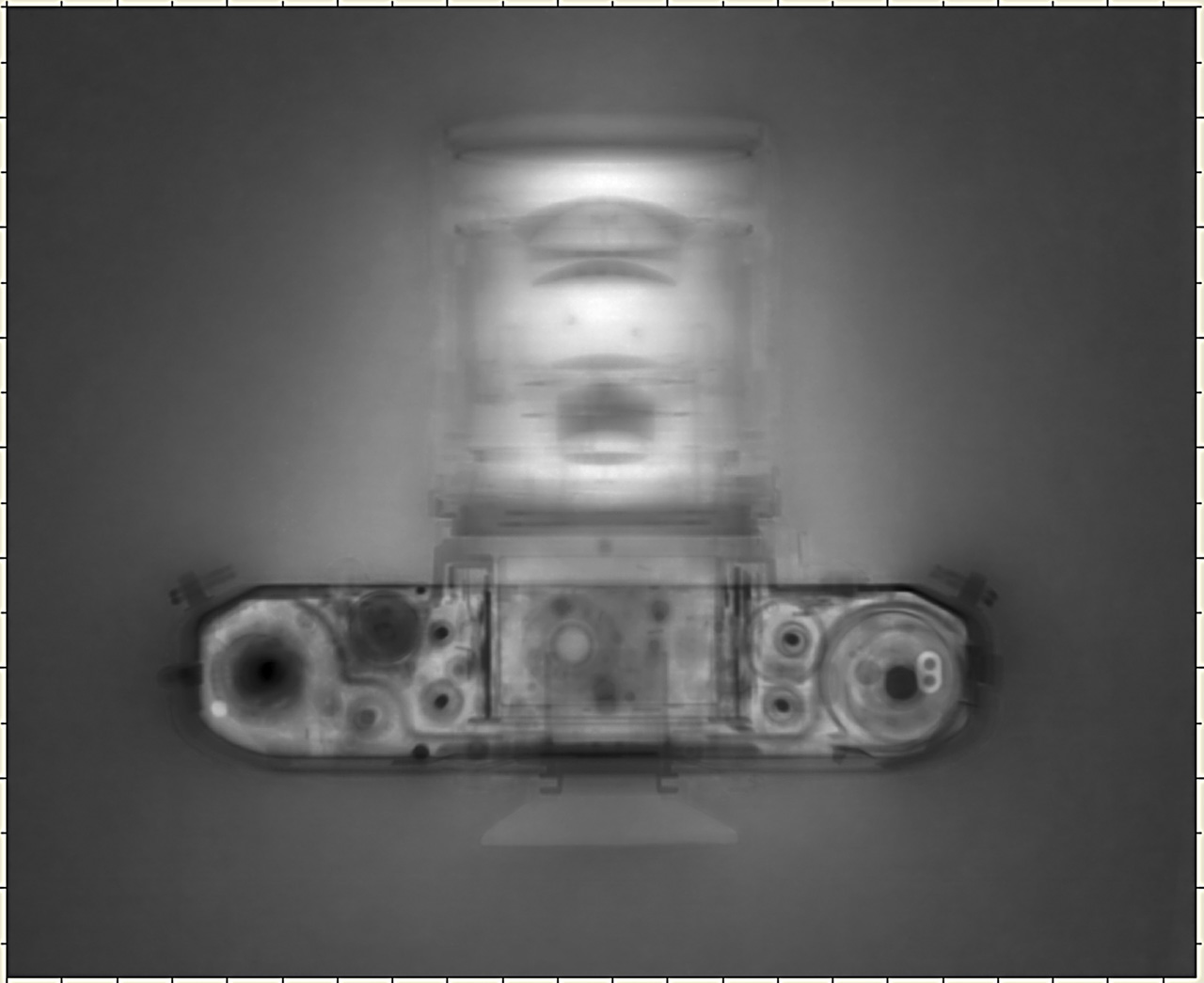

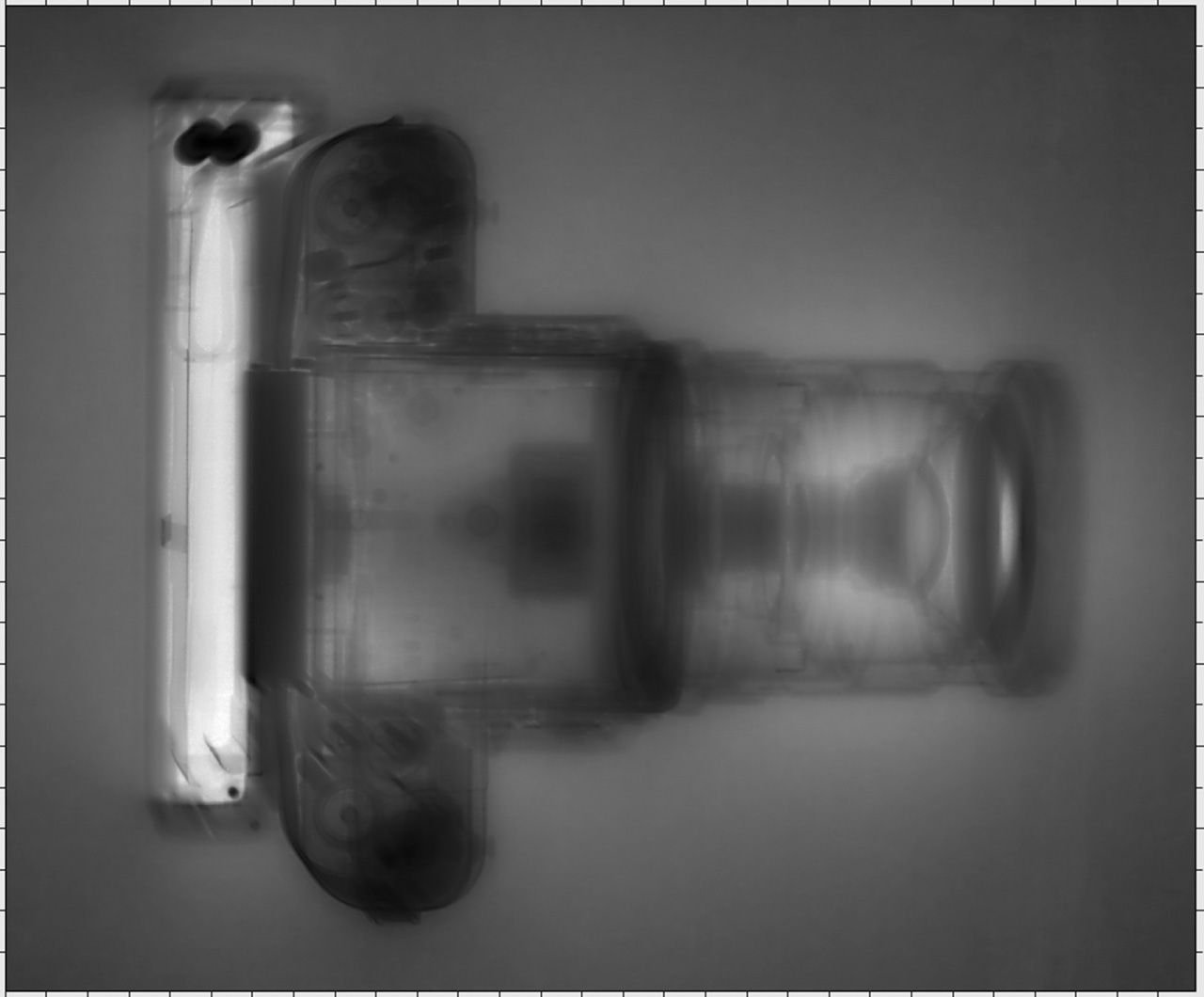

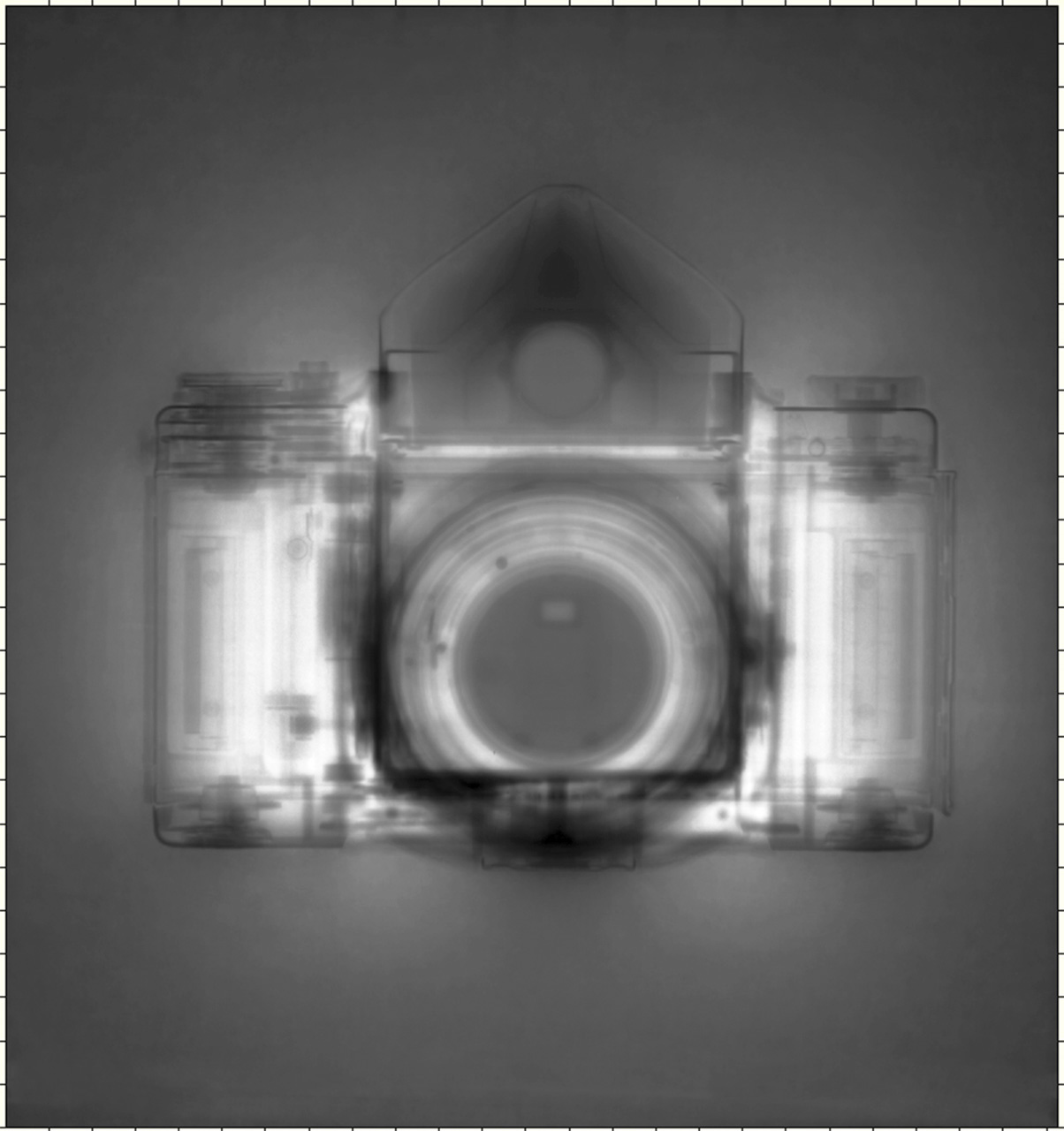

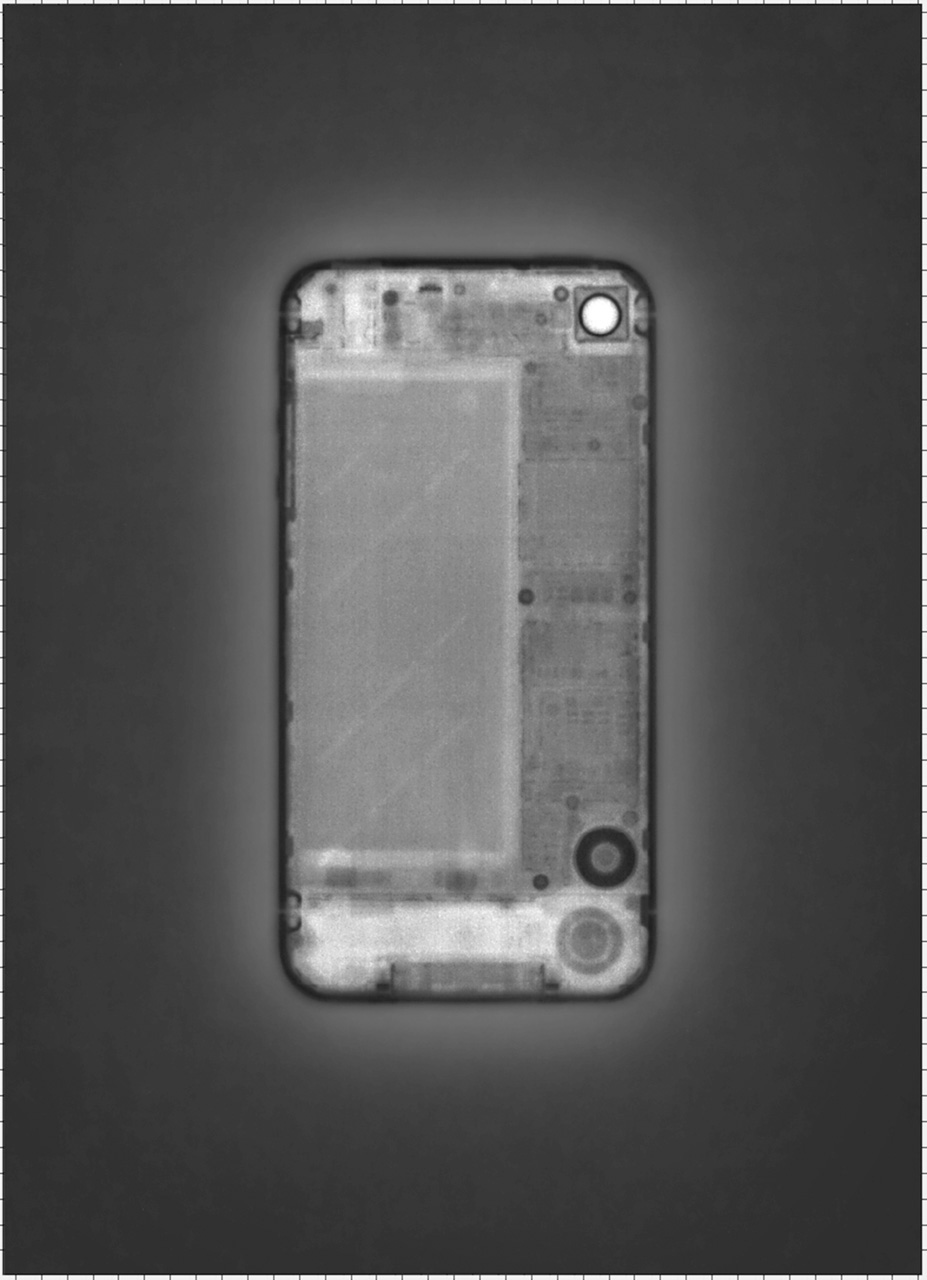

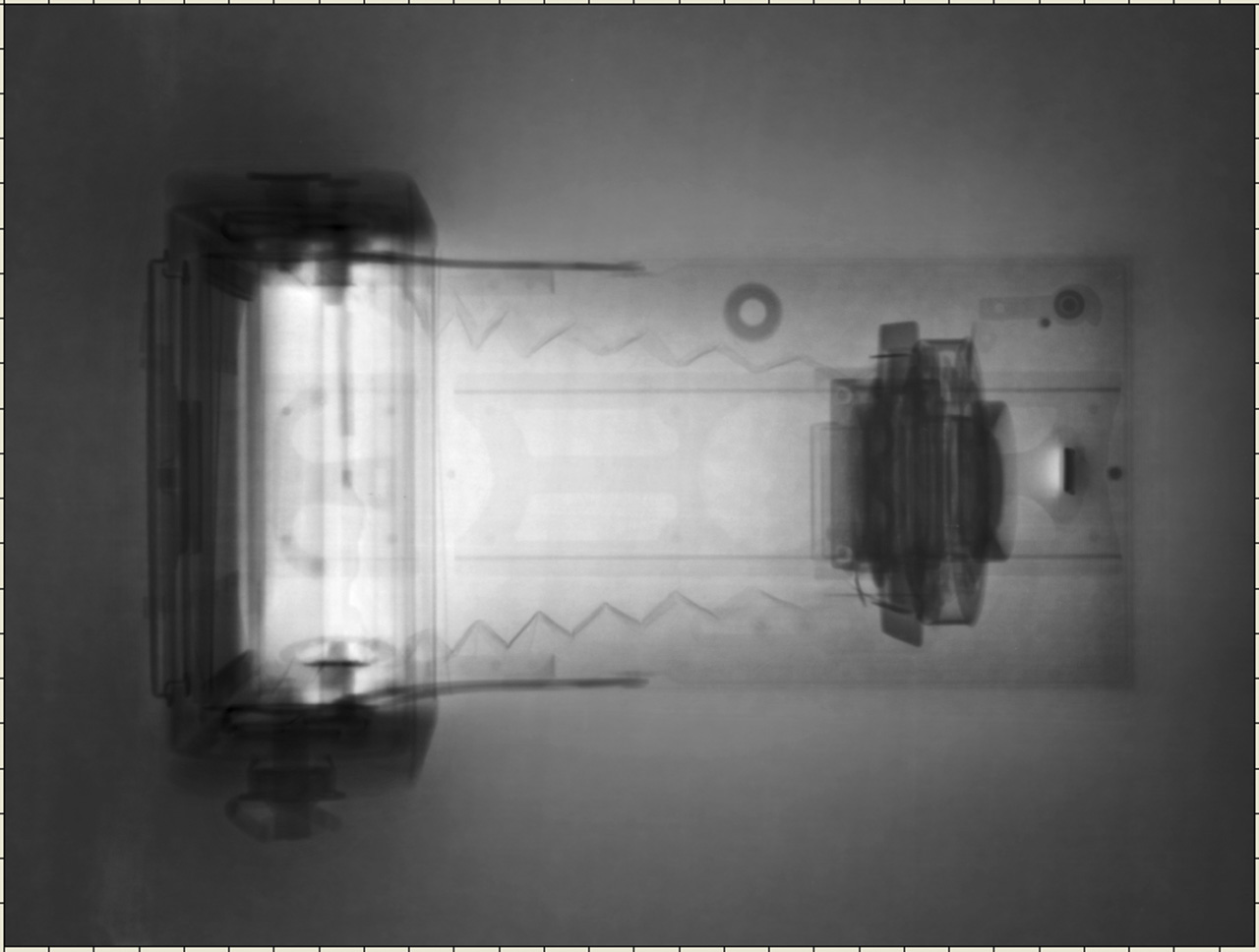

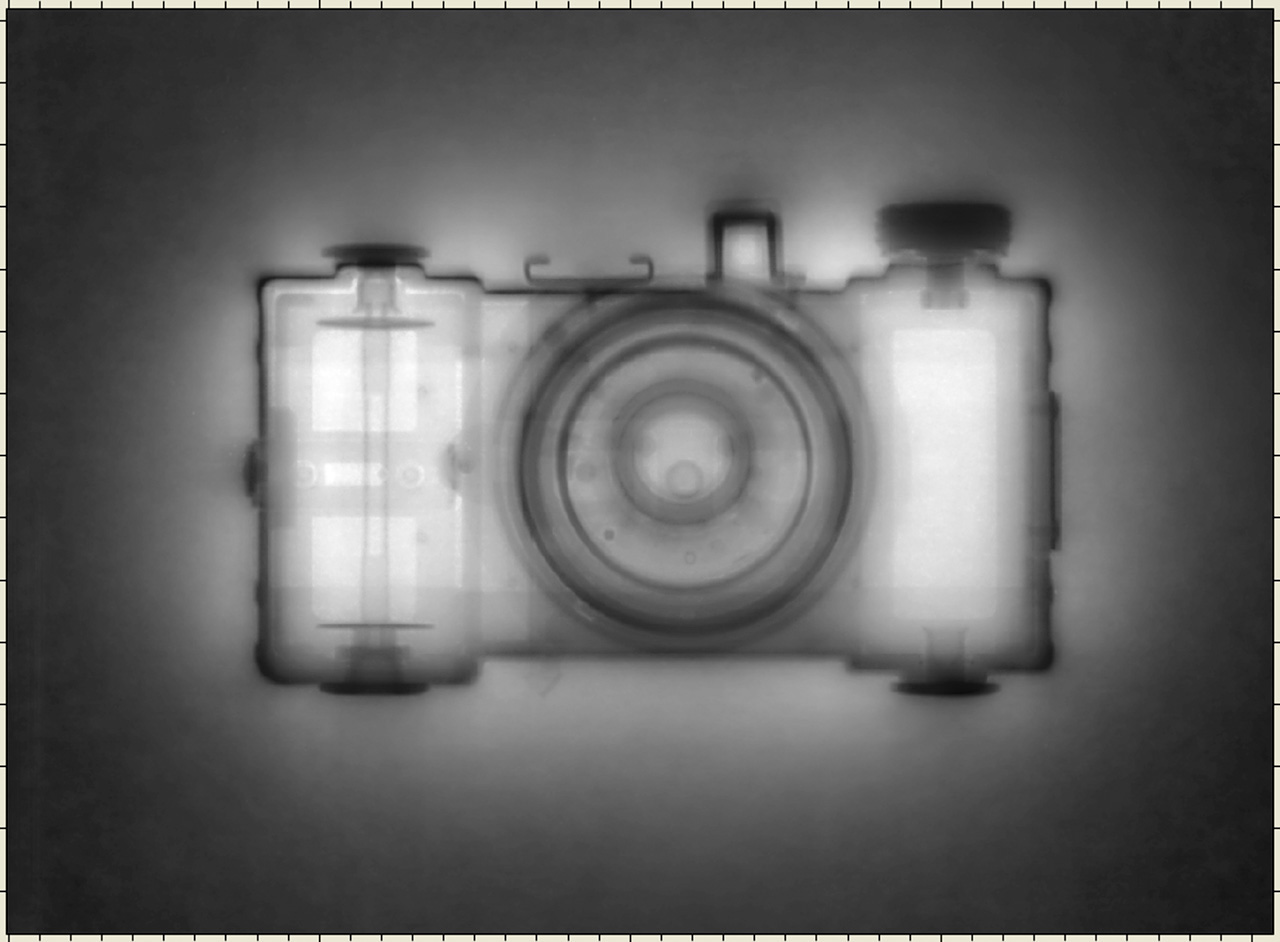

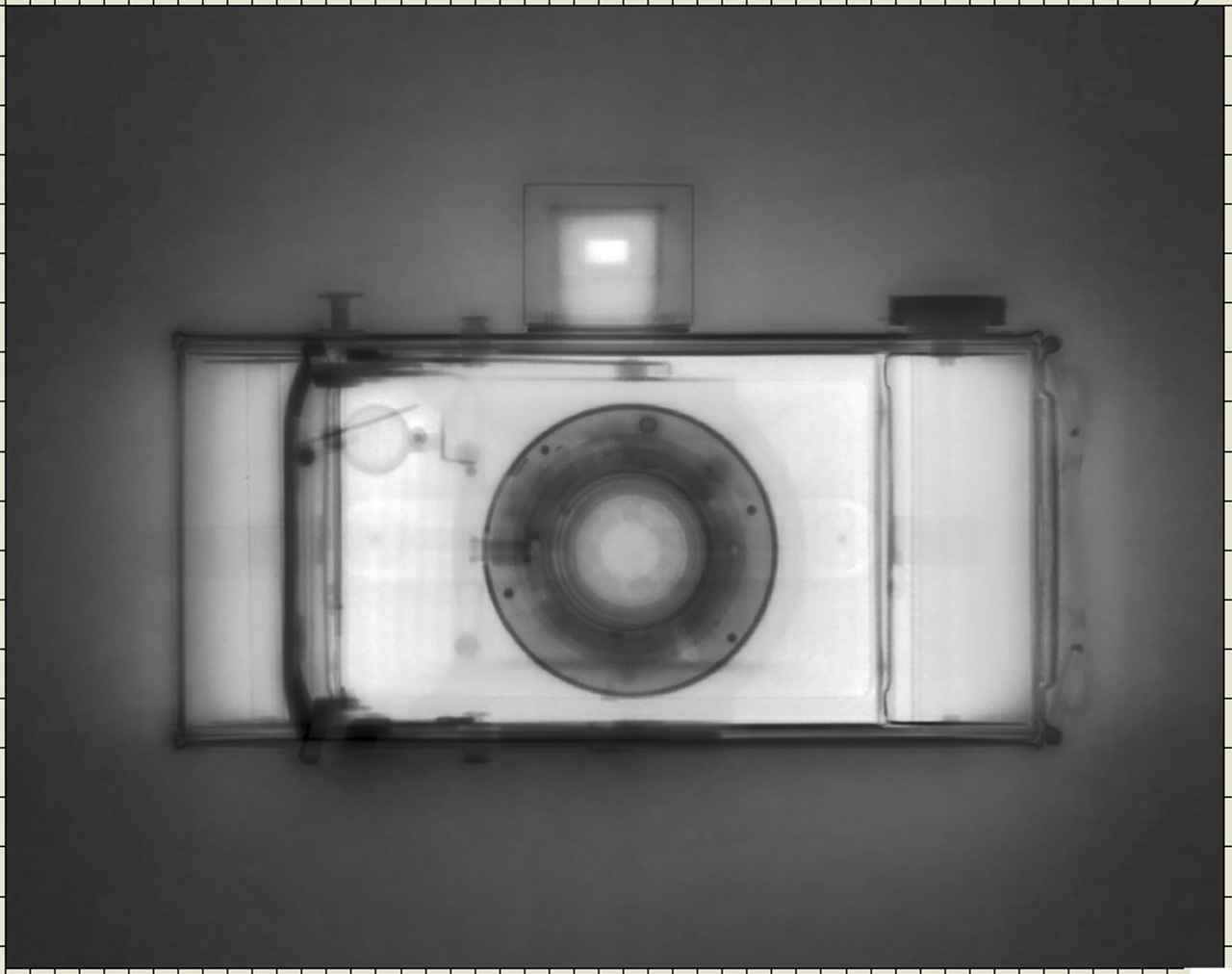

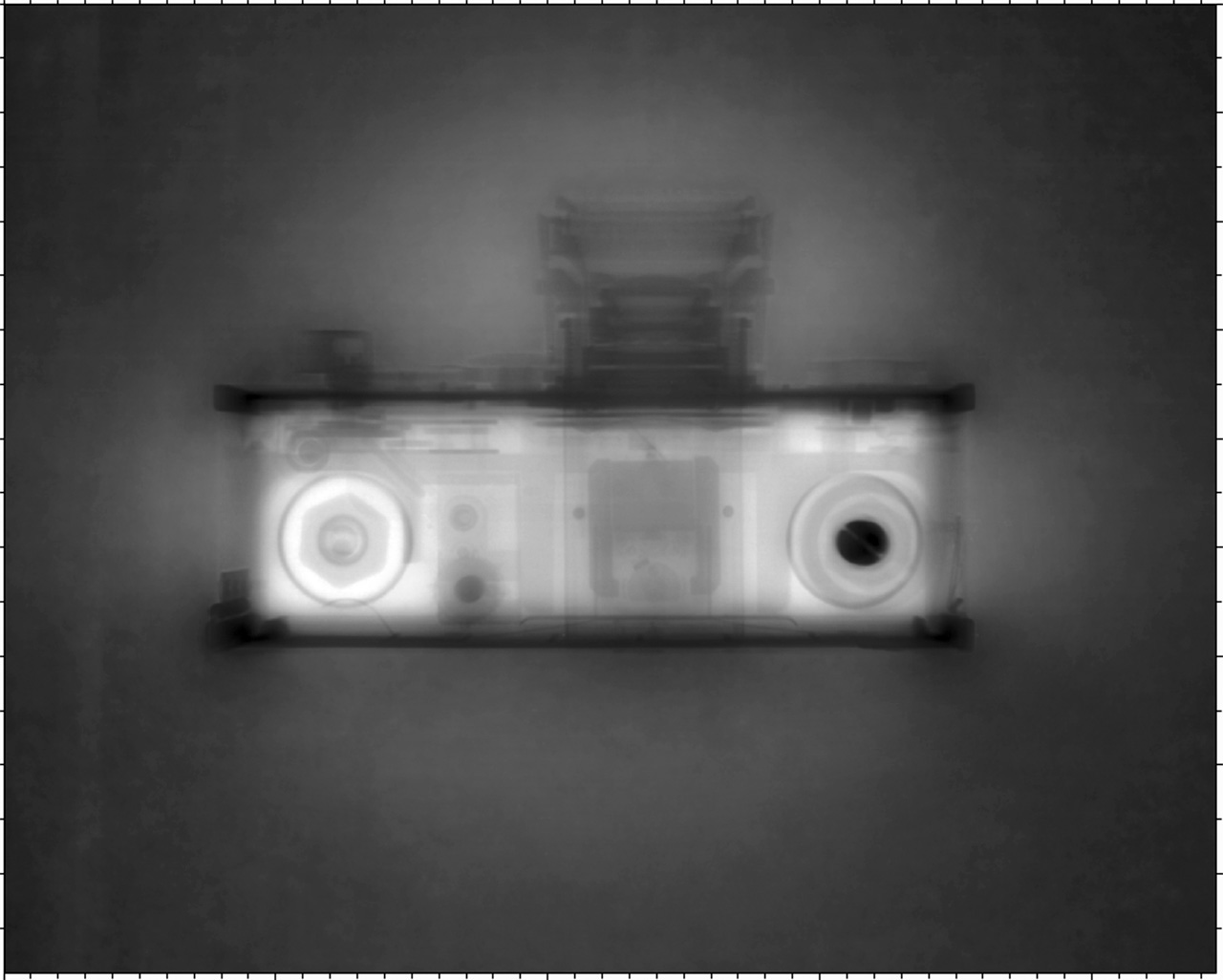

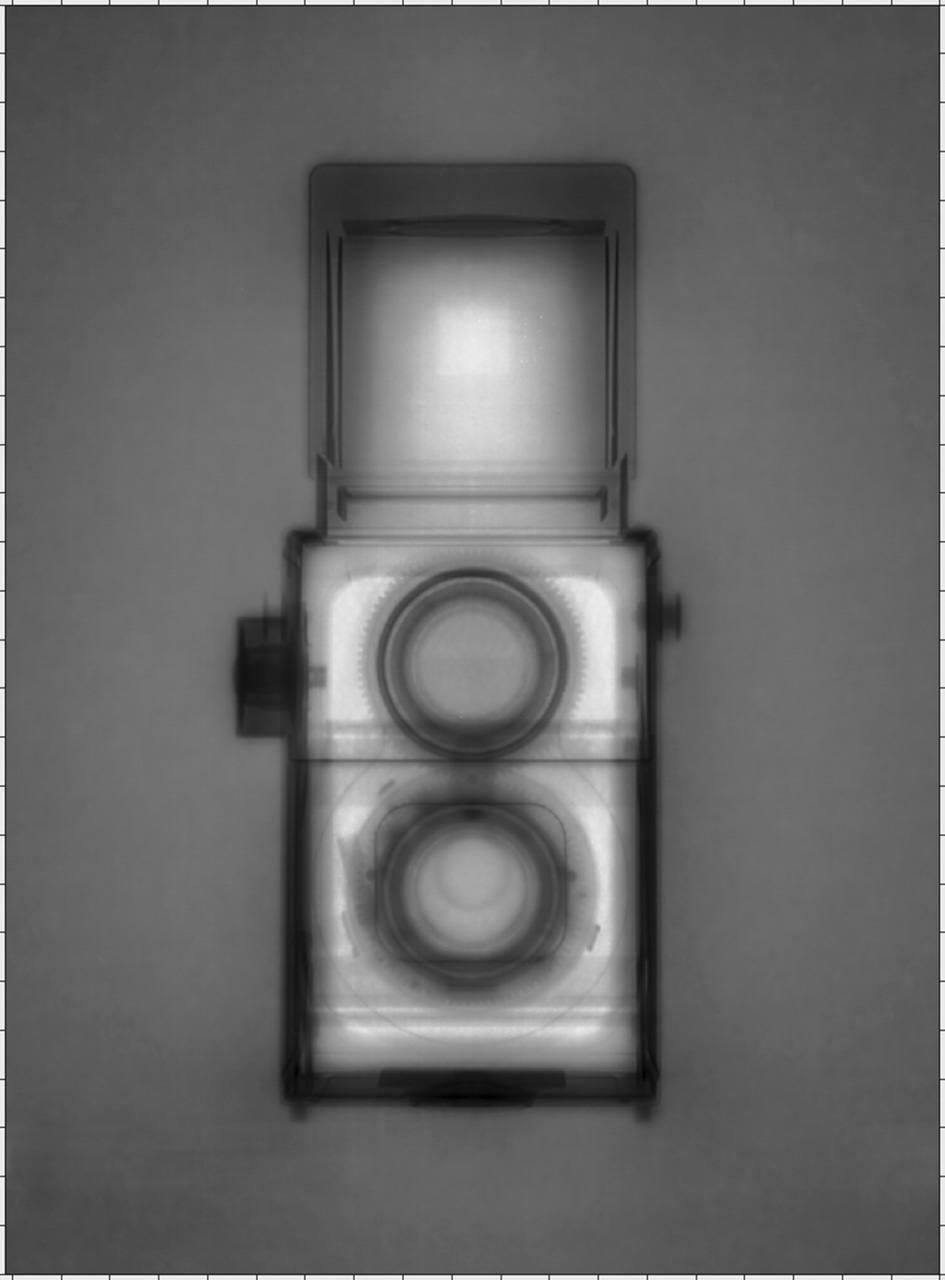

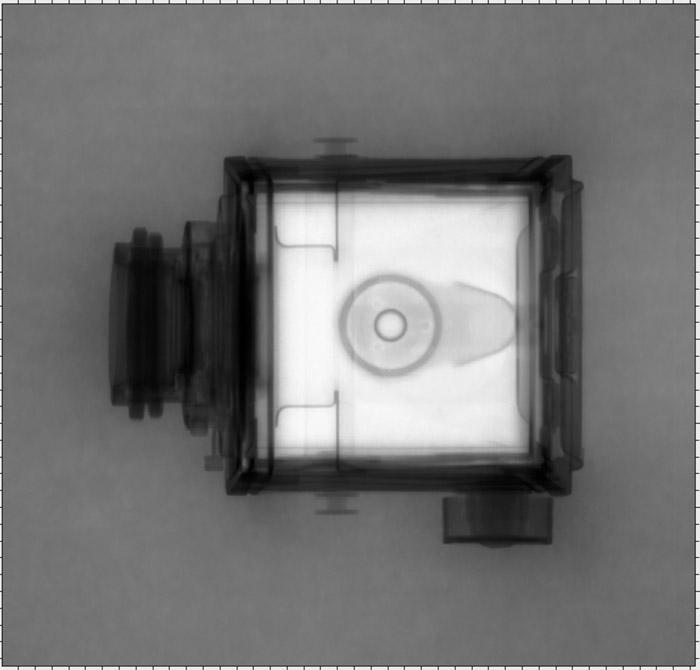

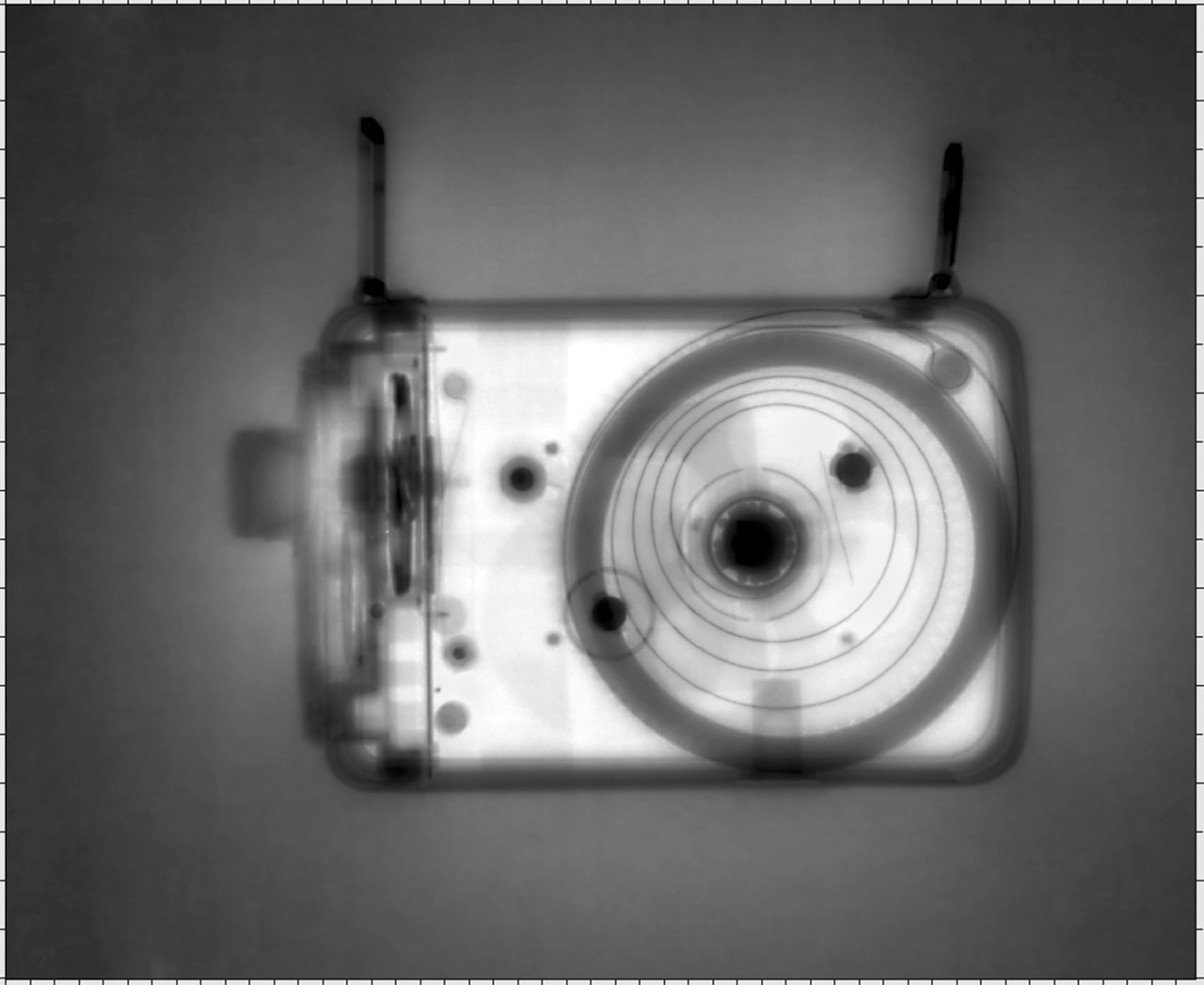

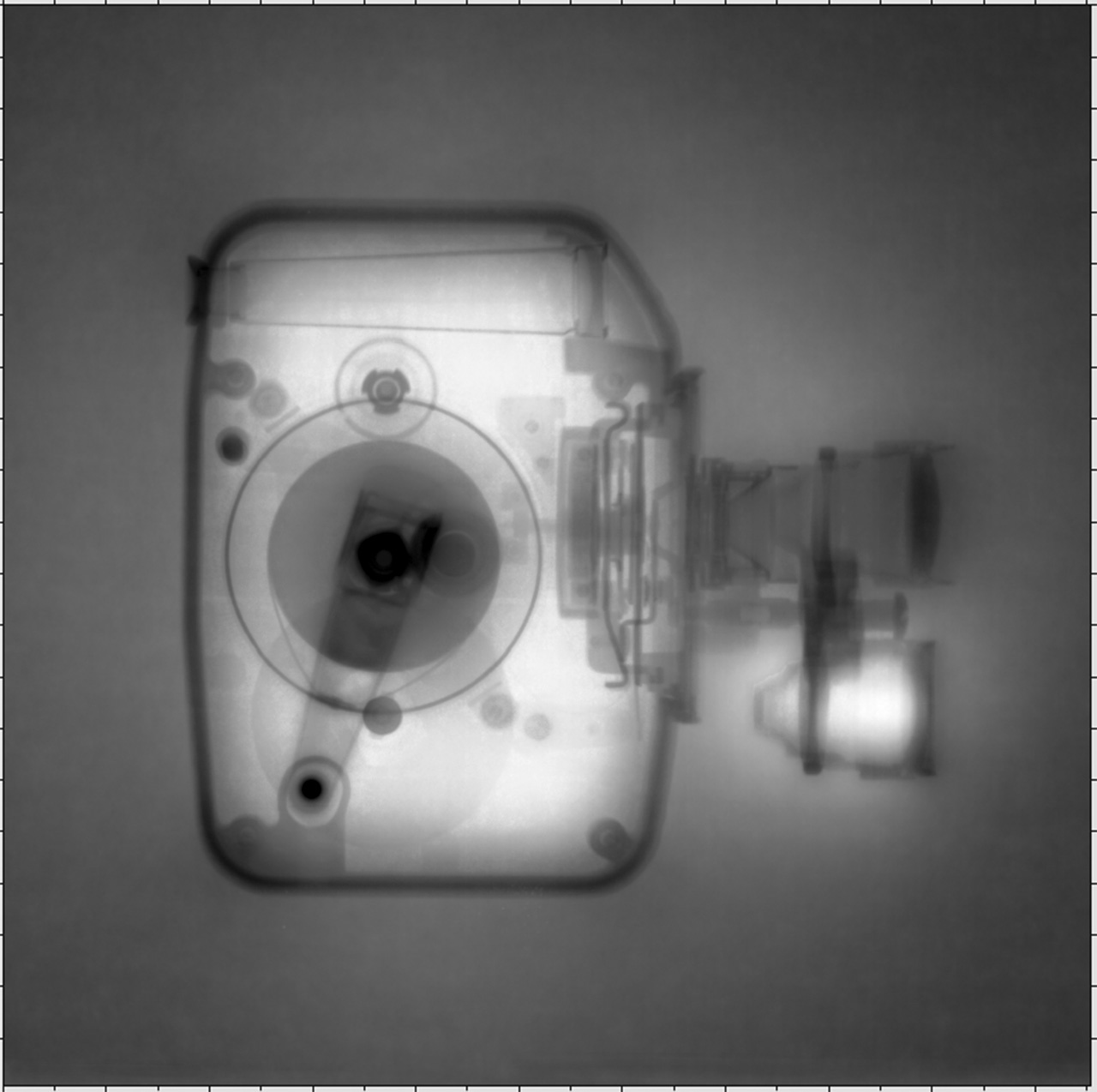

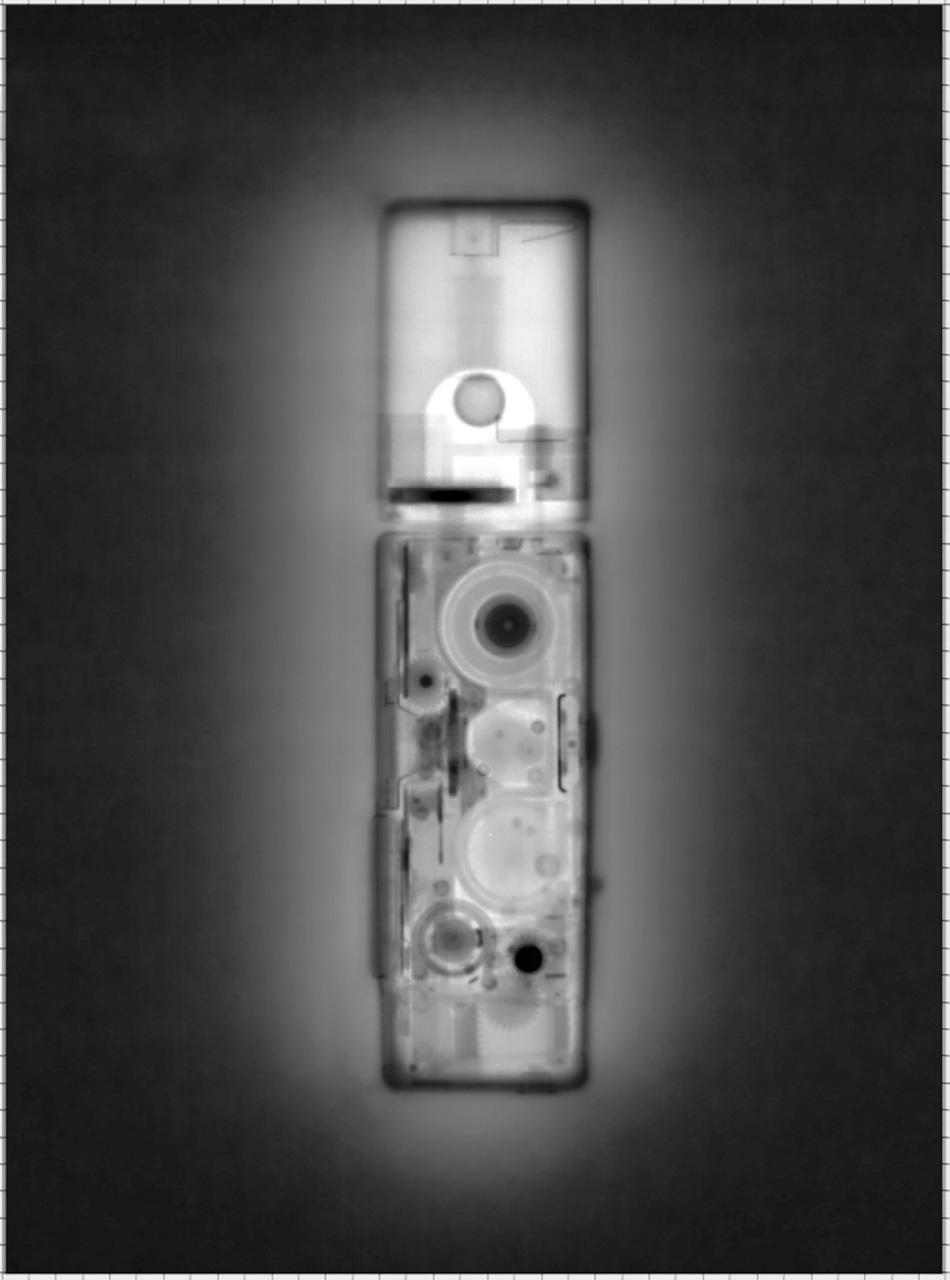

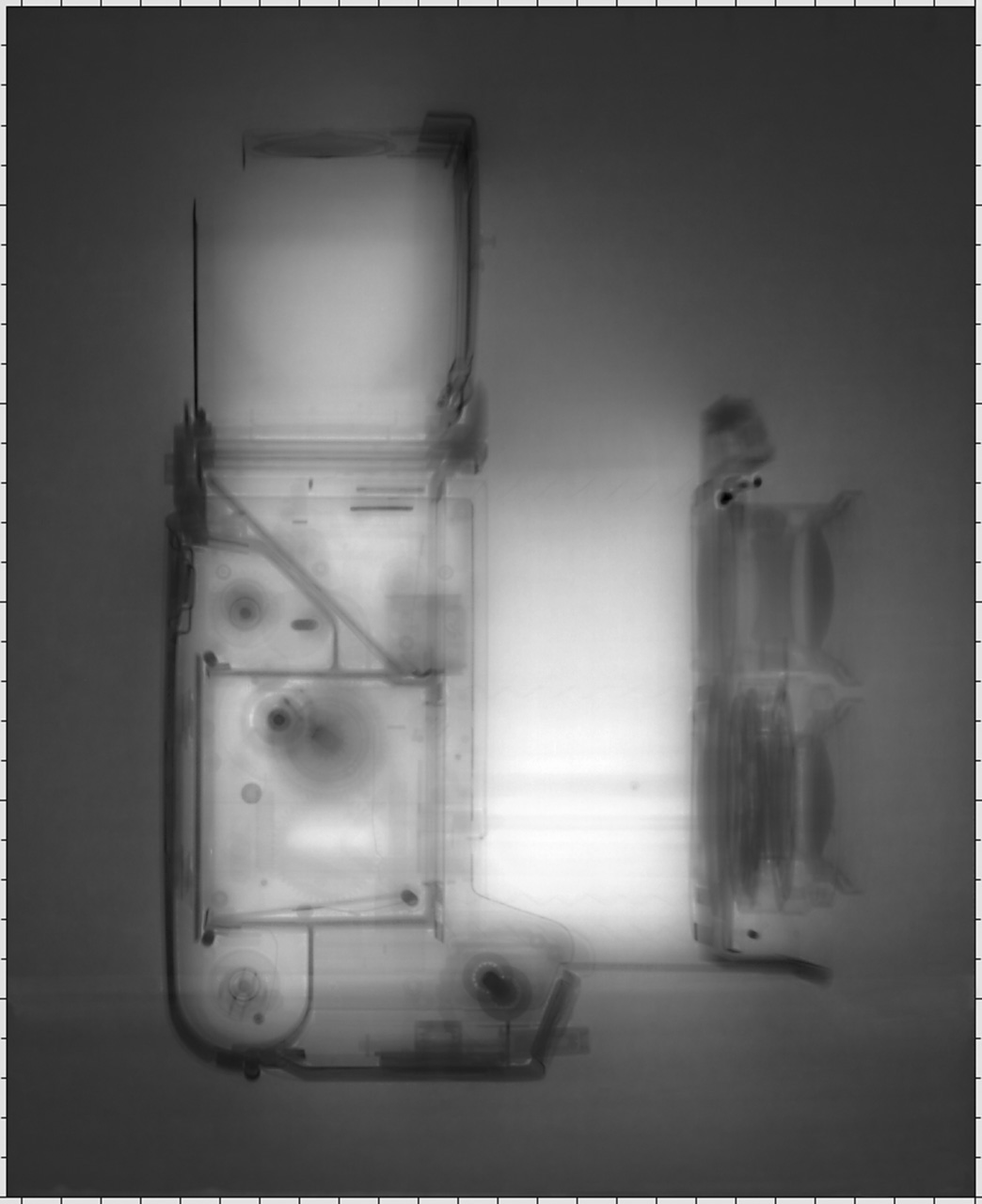

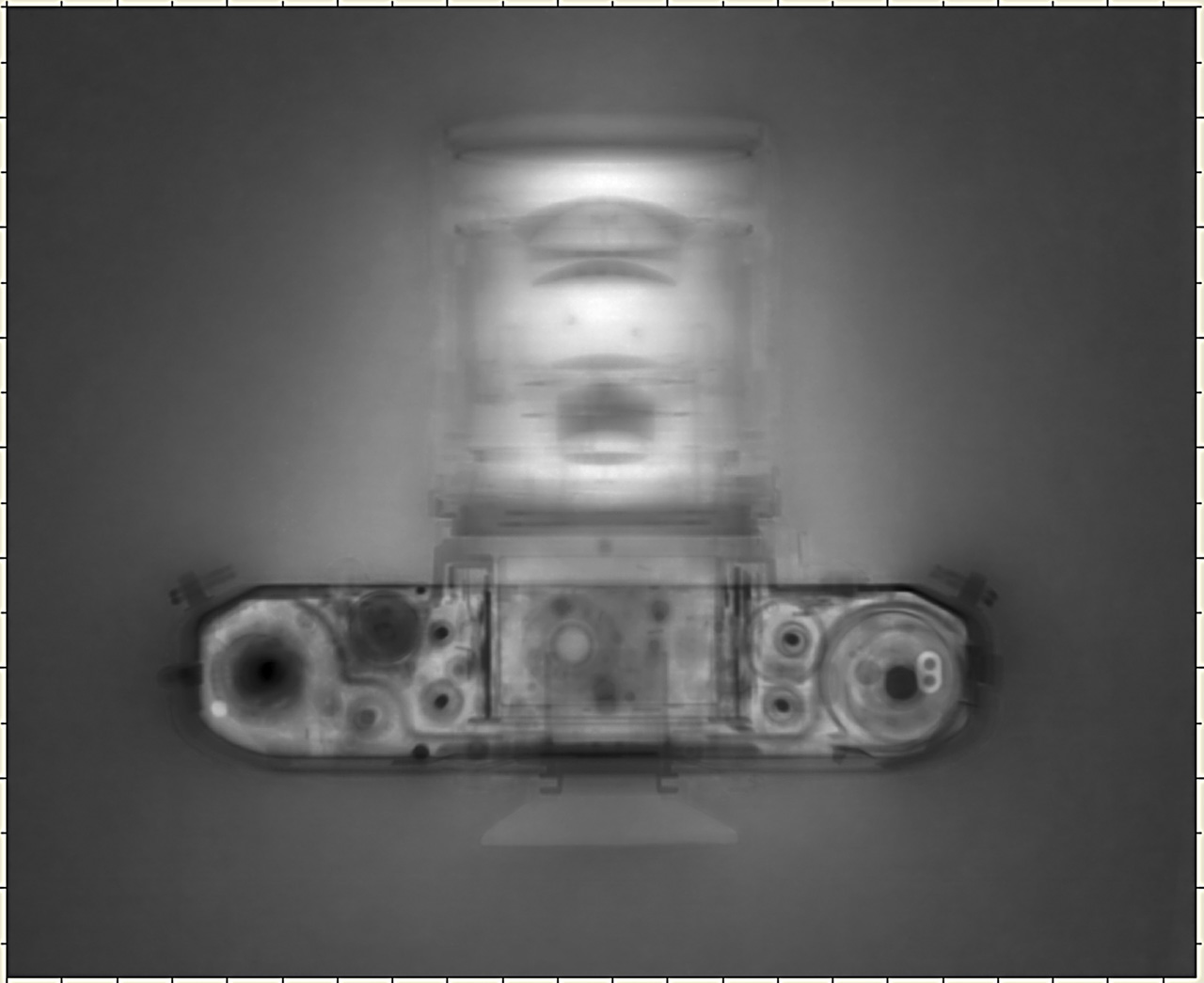

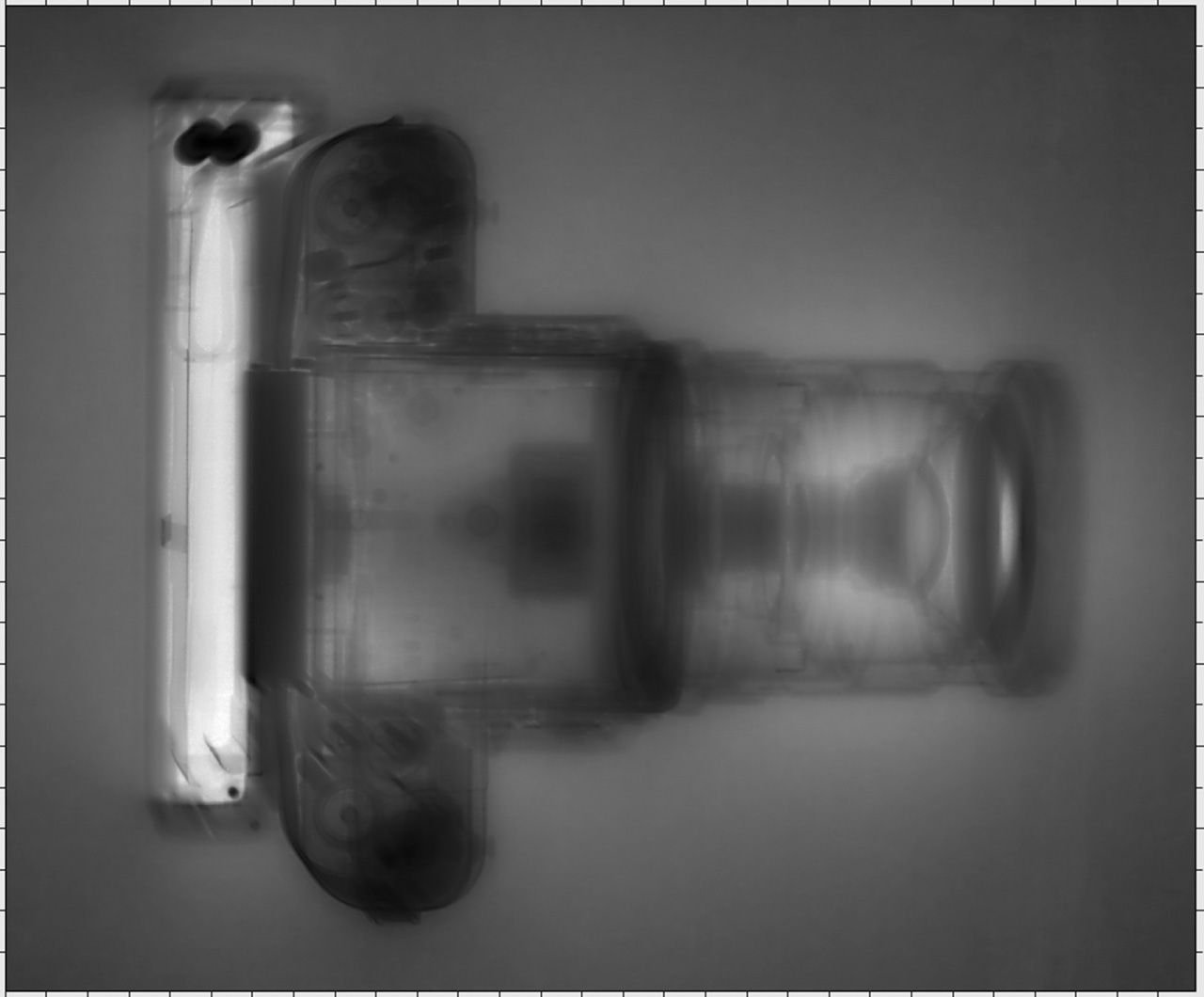

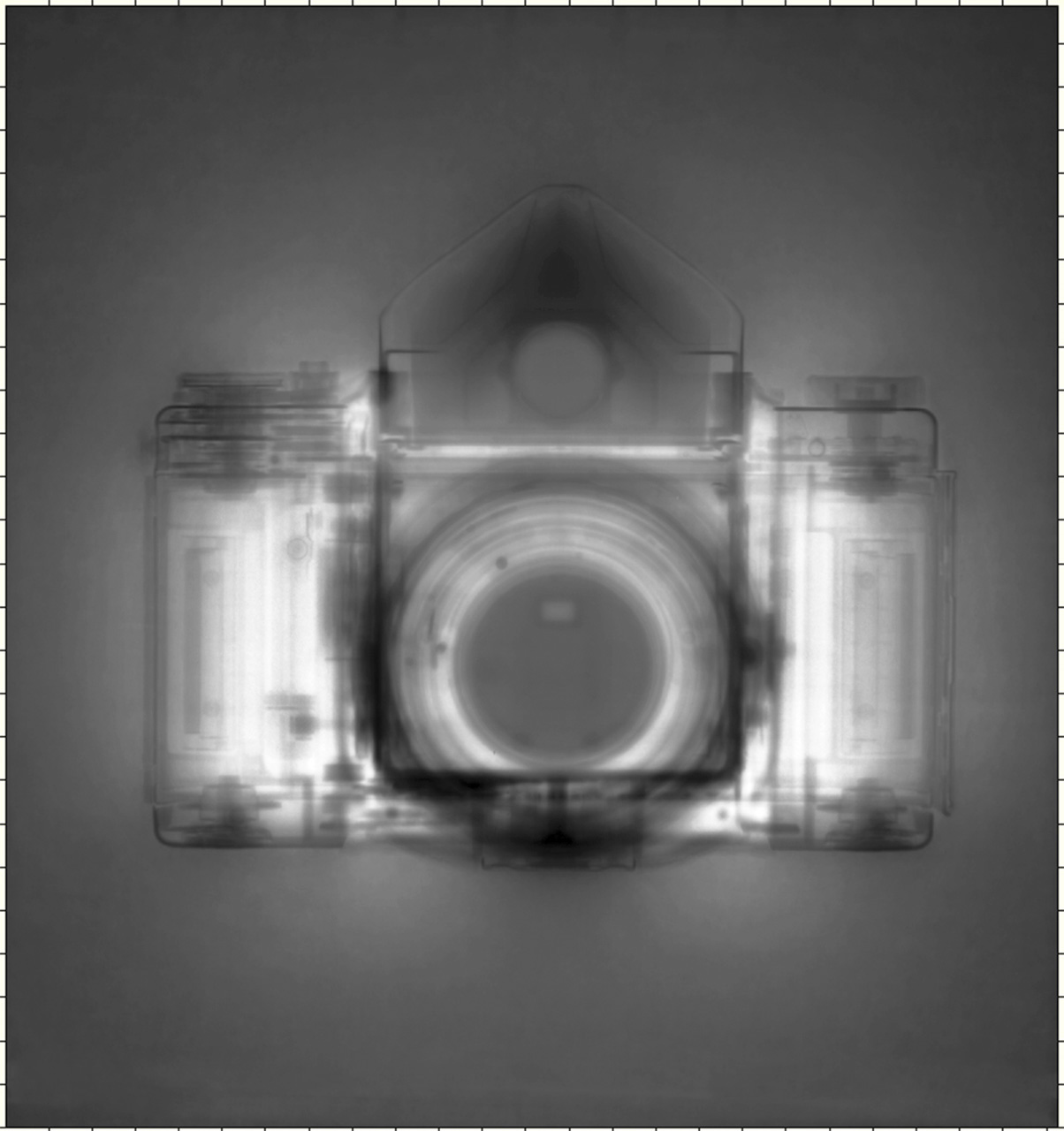

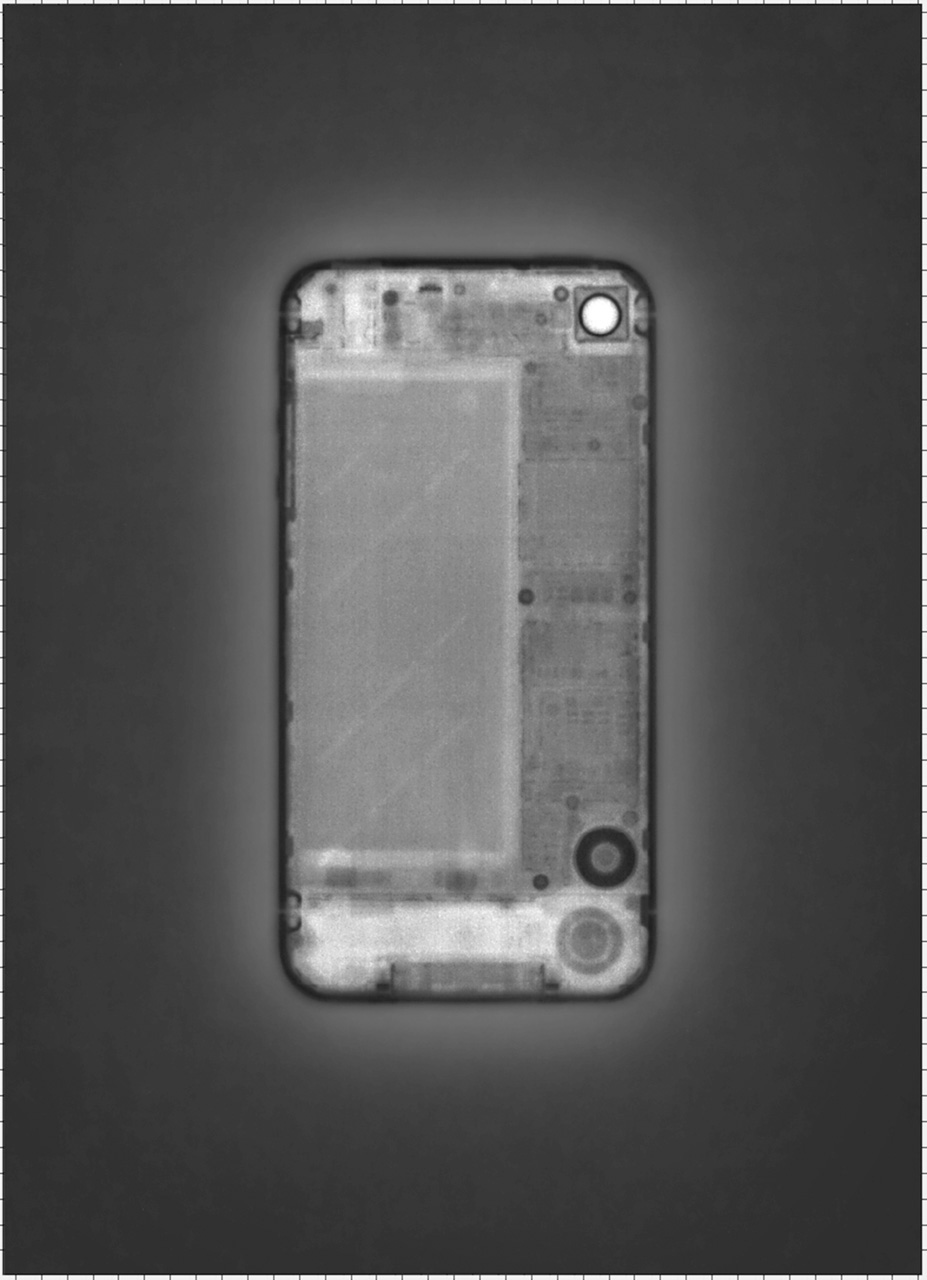

This body of work, using linear accelerator x-rays of cameras, explores the micro-evolution of cameras over time. While form and media may have changed, the camera is still a camera: a tool to create images by capturing photons of light. In a sense, it is an homage to the cameras I have used and handled. A linear accelerator produces high energy particles and x-rays and is used in physics research and health care to treat cancer patients. The resulting images align with an inner desire to probe those unseen spaces and realms I sense exist, but do not observe with my eyes.

Kent Krugh is a fine art photographer, living and working in Greater Cincinnati, OH. Ten years ago he decided to dedicate himself to photography. He has received numerous awards in national and international competitions and was a Photolucida 2012 and 2014 Critical Mass Finalist.. His work has been exhibited in national and international group and solo venues. He also taught workshops in collaboration with Colegiatura Colombiana del Diseño, Fundación Universitaria de Bellas Artes and Centro Colombo Americano under the auspices of the Universidad de Antioquia. Krugh’s work has been exhibited at three major festivals: Fringe Festival 2010, Cincinnati, OH; FotoFest Biennial 2012, Houston, TX; and FotoFocus Biennial 2012, Cincinnati, OH. Krugh's work can be found in numerous private collections and museums including the Portland Art Museum and the Cleveland Museum of Art.

Kent Krugh is a fine art photographer, living and working in Greater Cincinnati, OH. Ten years ago he decided to dedicate himself to photography. He has received numerous awards in national and international competitions and was a Photolucida 2012 and 2014 Critical Mass Finalist.. His work has been exhibited in national and international group and solo venues. He also taught workshops in collaboration with Colegiatura Colombiana del Diseño, Fundación Universitaria de Bellas Artes and Centro Colombo Americano under the auspices of the Universidad de Antioquia. Krugh’s work has been exhibited at three major festivals: Fringe Festival 2010, Cincinnati, OH; FotoFest Biennial 2012, Houston, TX; and FotoFocus Biennial 2012, Cincinnati, OH. Krugh's work can be found in numerous private collections and museums including the Portland Art Museum and the Cleveland Museum of Art.[core_state] => 1 [core_access] => 1 [core_metadata] => {"robots":"","author":"Kent Krugh","rights":"","xreference":""} [core_created_user_id] => 838 [core_created_by_alias] => [core_created_time] => 2015-02-10 21:22:20 [core_images] => {"image_intro":"images\/categories\/open-content\/krugh.jpg","float_intro":"","image_intro_alt":"","image_intro_caption":"","image_fulltext":"images\/categories\/open-content\/krugh.jpg","float_fulltext":"","image_fulltext_alt":"","image_fulltext_caption":""} [core_modified_time] => 2016-06-22 18:25:45 [core_language] => en-GB [core_catid] => 37 [core_publish_up] => 2015-02-10 21:22:20 [core_publish_down] => 0000-00-00 00:00:00 [content_type_title] => Article [router] => ContentHelperRoute::getArticleRoute [author] => Elisa Rugo [author_email] => elisa@zonezero.com [link] => index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=248:speciation&catid=37&lang=en-GB [displayDate] => 2015-02-10 21:22:20 [event] => stdClass Object ( [afterDisplayTitle] => [beforeDisplayContent] => [afterDisplayContent] => ) [text] =>

This body of work, using linear accelerator x-rays of cameras, explores the micro-evolution of cameras over time. While form and media may have changed, the camera is still a camera: a tool to create images by capturing photons of light. In a sense, it is an homage to the cameras I have used and handled. A linear accelerator produces high energy particles and x-rays and is used in physics research and health care to treat cancer patients. The resulting images align with an inner desire to probe those unseen spaces and realms I sense exist, but do not observe with my eyes.

Kent Krugh is a fine art photographer, living and working in Greater Cincinnati, OH. Ten years ago he decided to dedicate himself to photography. He has received numerous awards in national and international competitions and was a Photolucida 2012 and 2014 Critical Mass Finalist.. His work has been exhibited in national and international group and solo venues. He also taught workshops in collaboration with Colegiatura Colombiana del Diseño, Fundación Universitaria de Bellas Artes and Centro Colombo Americano under the auspices of the Universidad de Antioquia. Krugh’s work has been exhibited at three major festivals: Fringe Festival 2010, Cincinnati, OH; FotoFest Biennial 2012, Houston, TX; and FotoFocus Biennial 2012, Cincinnati, OH. Krugh's work can be found in numerous private collections and museums including the Portland Art Museum and the Cleveland Museum of Art.

Kent Krugh is a fine art photographer, living and working in Greater Cincinnati, OH. Ten years ago he decided to dedicate himself to photography. He has received numerous awards in national and international competitions and was a Photolucida 2012 and 2014 Critical Mass Finalist.. His work has been exhibited in national and international group and solo venues. He also taught workshops in collaboration with Colegiatura Colombiana del Diseño, Fundación Universitaria de Bellas Artes and Centro Colombo Americano under the auspices of the Universidad de Antioquia. Krugh’s work has been exhibited at three major festivals: Fringe Festival 2010, Cincinnati, OH; FotoFest Biennial 2012, Houston, TX; and FotoFocus Biennial 2012, Cincinnati, OH. Krugh's work can be found in numerous private collections and museums including the Portland Art Museum and the Cleveland Museum of Art.[id] => 248 [language] => en-GB [catid] => 37 [jcfields] => Array ( ) ) 1

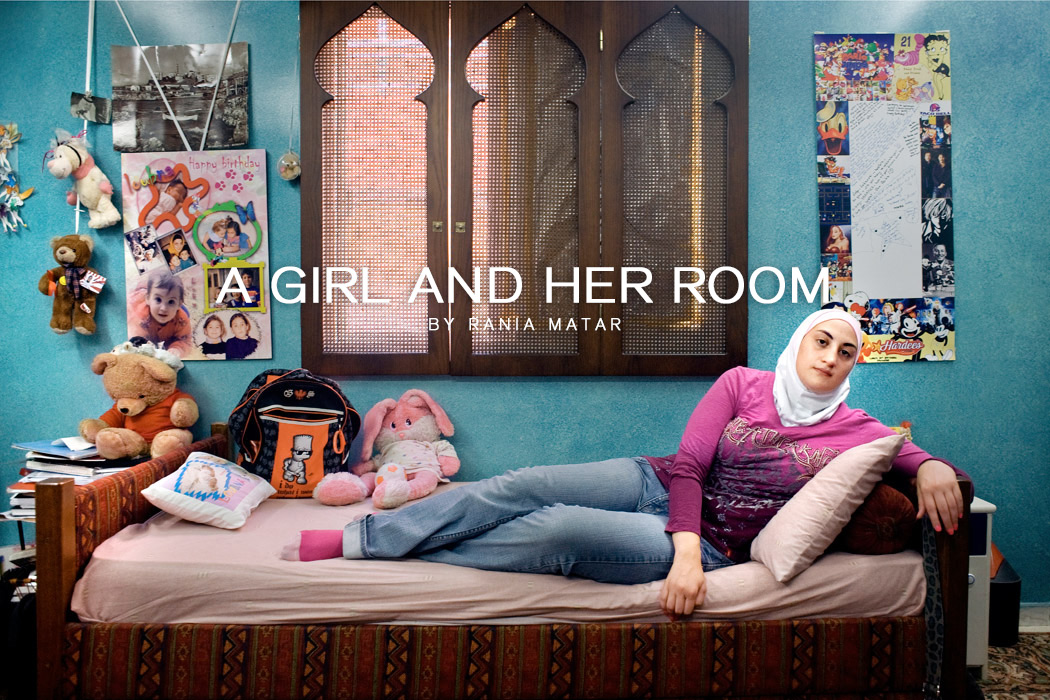

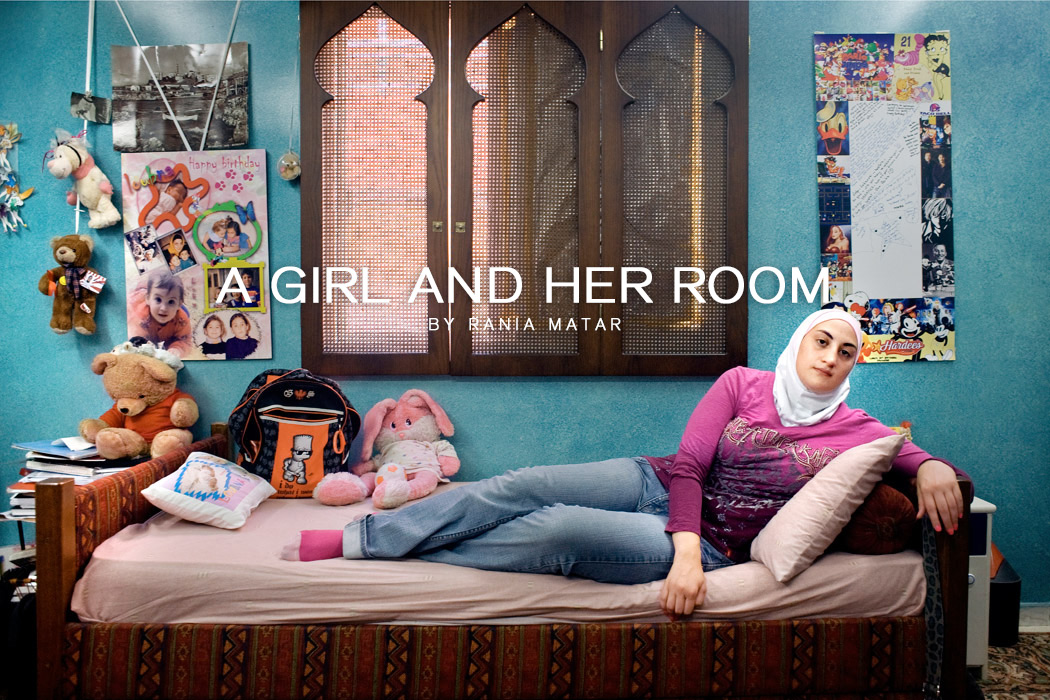

Rania Matar

A girl and her room

A Girl and Her Room was inspired by my oldest daughter, then 15, who was no longer a carefree child. She was shifting into adulthood incrementally before my eyes. After photographing her with her girlfriends, I realized I wanted to capture each young woman by herself in her own environment: her bedroom. The room was a metaphor, an extension of the girl, but also the girl seemed to be part of the room, to fit in just like everything else in the material and emotional space she created.

While I initially focused on teenage girls in the United States, I eventually expanded the project to include girls from the other world I experienced myself as a young woman: the Middle East. This is how this project became personal to me. The beauty, dreams, vulnerability and strength of these young women, regardless of place, background and religion, were beautifully universal and deeply moving.

Being with those young women in the privacy of their world gave me a unique peek into their private lives and their inner selves. They sensed that I was not judging them and became an active part of the project. Their frankness and generosity in sharing access was a privilege that they have extended to me but also to all the viewers of this work.

Rania Matar (Lebanon, 1964). Originally trained as an architect at the American University of Beirut and at Cornell University, she studied photography at the New England School of Photography and the Maine Photographic Workshops. Her work focuses on girls and women. She documents her life through the lives of those around her, focusing on the personal and the mundane in an attempt to portray the universal within the personal. Her work has won several awards, is part of several museum and private collections, has been featured in numerous publications, and exhibited widely in the U.S. and internationally. Visit her website: raniamatar.com

Rania Matar (Lebanon, 1964). Originally trained as an architect at the American University of Beirut and at Cornell University, she studied photography at the New England School of Photography and the Maine Photographic Workshops. Her work focuses on girls and women. She documents her life through the lives of those around her, focusing on the personal and the mundane in an attempt to portray the universal within the personal. Her work has won several awards, is part of several museum and private collections, has been featured in numerous publications, and exhibited widely in the U.S. and internationally. Visit her website: raniamatar.com

A girl and her room

A Girl and Her Room was inspired by my oldest daughter, then 15, who was no longer a carefree child. She was shifting into adulthood incrementally before my eyes. After photographing her with her girlfriends, I realized I wanted to capture each young woman by herself in her own environment: her bedroom. The room was a metaphor, an extension of the girl, but also the girl seemed to be part of the room, to fit in just like everything else in the material and emotional space she created.

While I initially focused on teenage girls in the United States, I eventually expanded the project to include girls from the other world I experienced myself as a young woman: the Middle East. This is how this project became personal to me. The beauty, dreams, vulnerability and strength of these young women, regardless of place, background and religion, were beautifully universal and deeply moving.

Being with those young women in the privacy of their world gave me a unique peek into their private lives and their inner selves. They sensed that I was not judging them and became an active part of the project. Their frankness and generosity in sharing access was a privilege that they have extended to me but also to all the viewers of this work.

Rania Matar (Lebanon, 1964). Originally trained as an architect at the American University of Beirut and at Cornell University, she studied photography at the New England School of Photography and the Maine Photographic Workshops. Her work focuses on girls and women. She documents her life through the lives of those around her, focusing on the personal and the mundane in an attempt to portray the universal within the personal. Her work has won several awards, is part of several museum and private collections, has been featured in numerous publications, and exhibited widely in the U.S. and internationally. Visit her website: raniamatar.com

Rania Matar (Lebanon, 1964). Originally trained as an architect at the American University of Beirut and at Cornell University, she studied photography at the New England School of Photography and the Maine Photographic Workshops. Her work focuses on girls and women. She documents her life through the lives of those around her, focusing on the personal and the mundane in an attempt to portray the universal within the personal. Her work has won several awards, is part of several museum and private collections, has been featured in numerous publications, and exhibited widely in the U.S. and internationally. Visit her website: raniamatar.comVictor Enrich

In 2013 Enrich produced NHDK, a series of 88 manipulated photographs - one for each piano key classical - of the Deutscher Kaiser hotel in Munich. The images, which all display the building from the same angle, imagine it variously with parts rotated, duplicated, removed and floating in the sky.

I find beautiful to connect two different disciplines, such as digital photography and graphic arts with piano. —Victor Enrich.

Victor Enrich (Spain, 1976). A catalan artist and a lover of nature, literature and architecture. Since childhood has been dedicated through various techniques to create images of fictional scenarios, always linking cities and architecture. Enrich currently dedicated exclusively to the development of his art, which is inseparably associated with his other great passion: traveling. Their work is highly valued abroad and he has succeeded in countries like Israel, where he has made several exhibitions.

Victor Enrich (Spain, 1976). A catalan artist and a lover of nature, literature and architecture. Since childhood has been dedicated through various techniques to create images of fictional scenarios, always linking cities and architecture. Enrich currently dedicated exclusively to the development of his art, which is inseparably associated with his other great passion: traveling. Their work is highly valued abroad and he has succeeded in countries like Israel, where he has made several exhibitions.In 2013 Enrich produced NHDK, a series of 88 manipulated photographs - one for each piano key classical - of the Deutscher Kaiser hotel in Munich. The images, which all display the building from the same angle, imagine it variously with parts rotated, duplicated, removed and floating in the sky.

I find beautiful to connect two different disciplines, such as digital photography and graphic arts with piano. —Victor Enrich.

Victor Enrich (Spain, 1976). A catalan artist and a lover of nature, literature and architecture. Since childhood has been dedicated through various techniques to create images of fictional scenarios, always linking cities and architecture. Enrich currently dedicated exclusively to the development of his art, which is inseparably associated with his other great passion: traveling. Their work is highly valued abroad and he has succeeded in countries like Israel, where he has made several exhibitions.

Victor Enrich (Spain, 1976). A catalan artist and a lover of nature, literature and architecture. Since childhood has been dedicated through various techniques to create images of fictional scenarios, always linking cities and architecture. Enrich currently dedicated exclusively to the development of his art, which is inseparably associated with his other great passion: traveling. Their work is highly valued abroad and he has succeeded in countries like Israel, where he has made several exhibitions.Natan Dvir

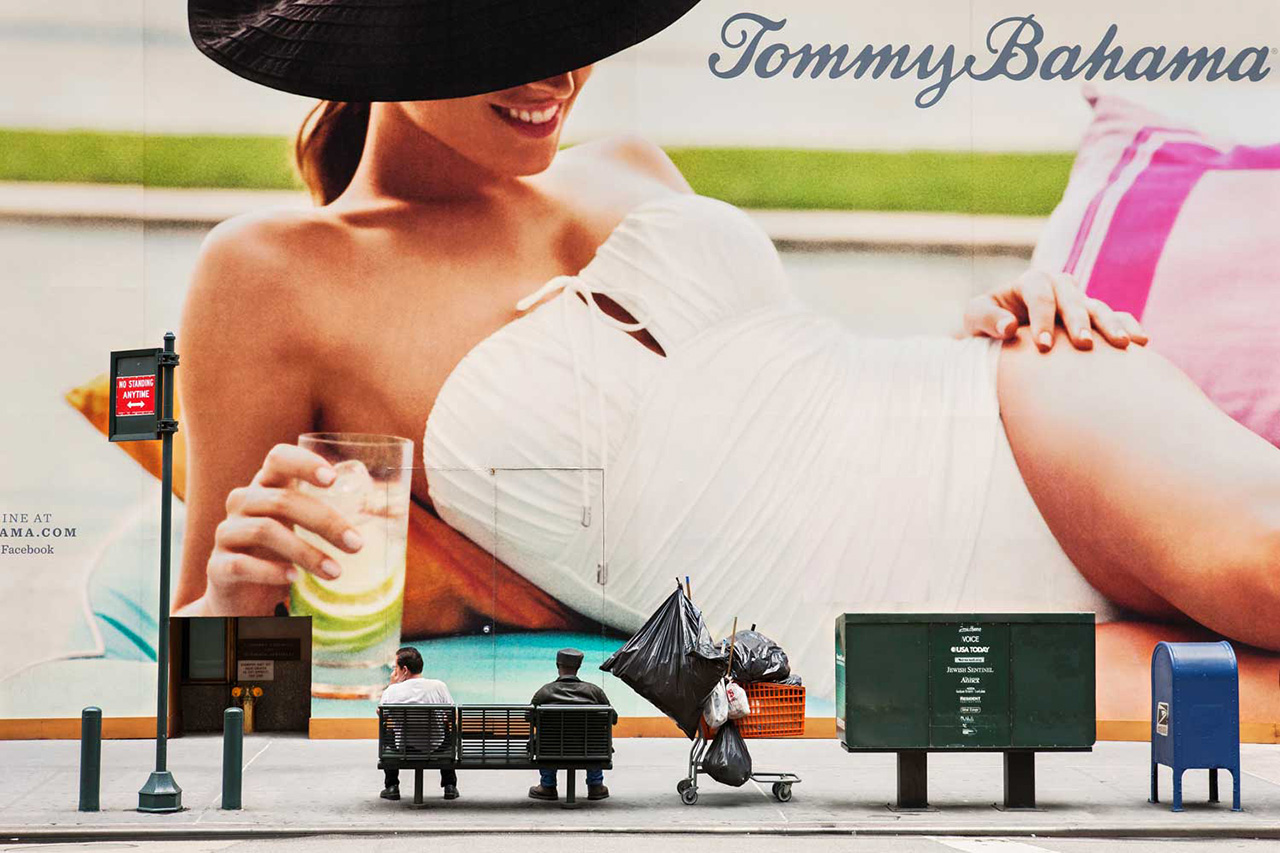

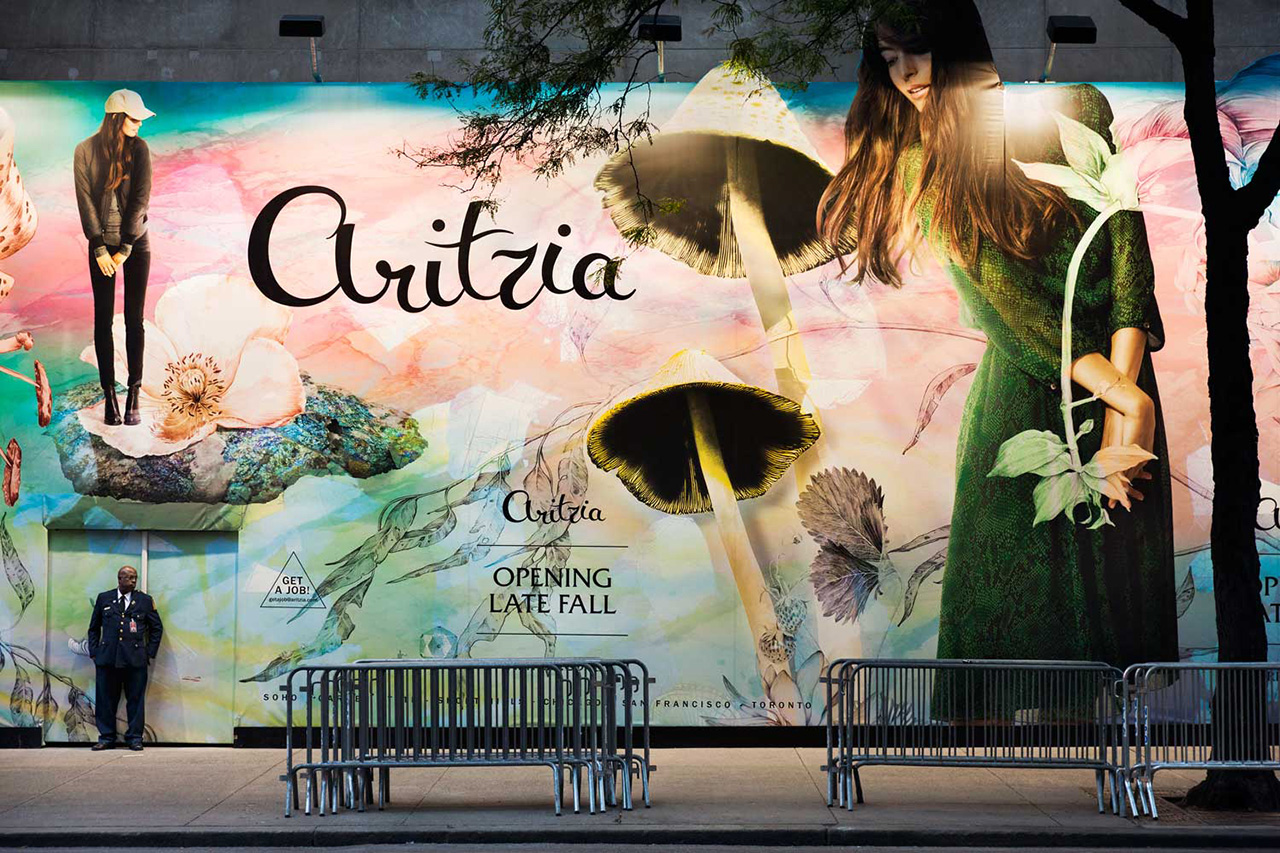

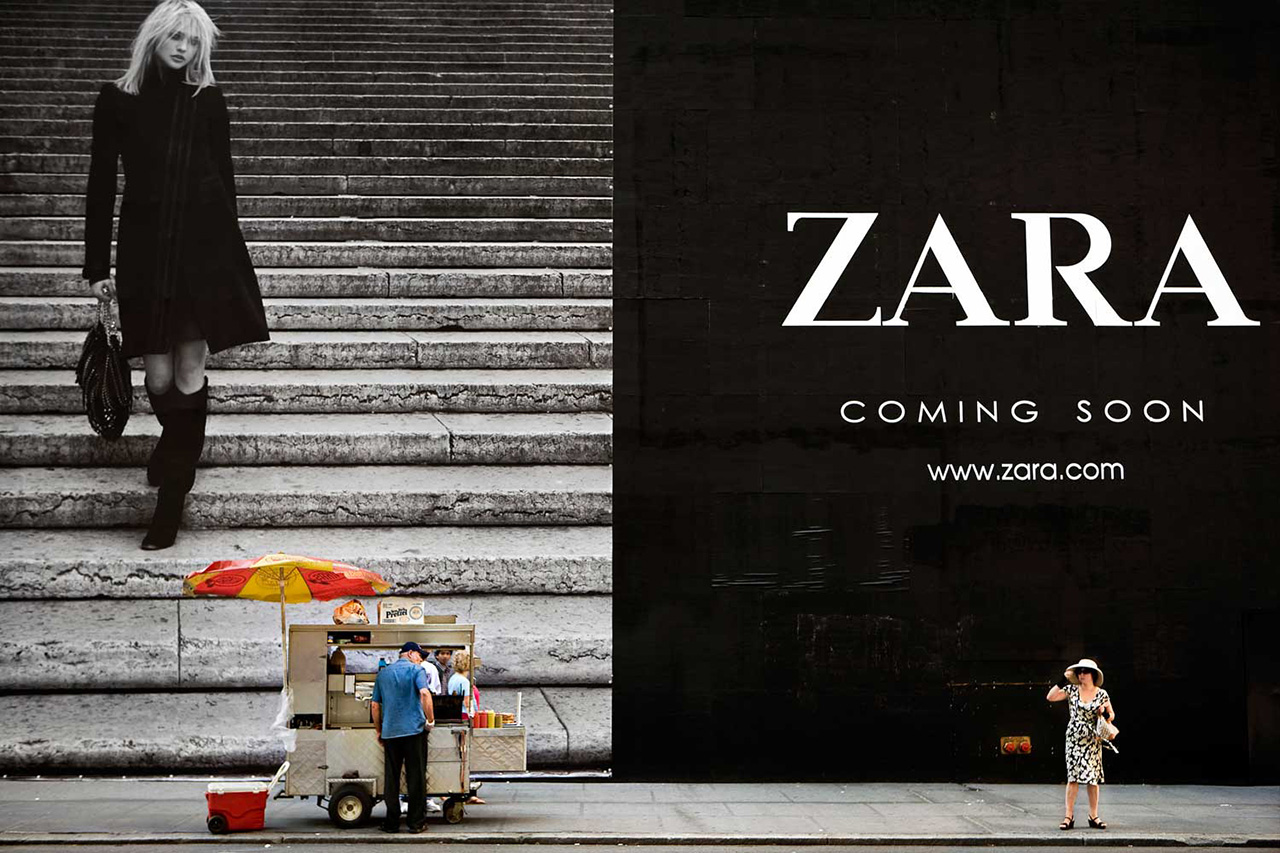

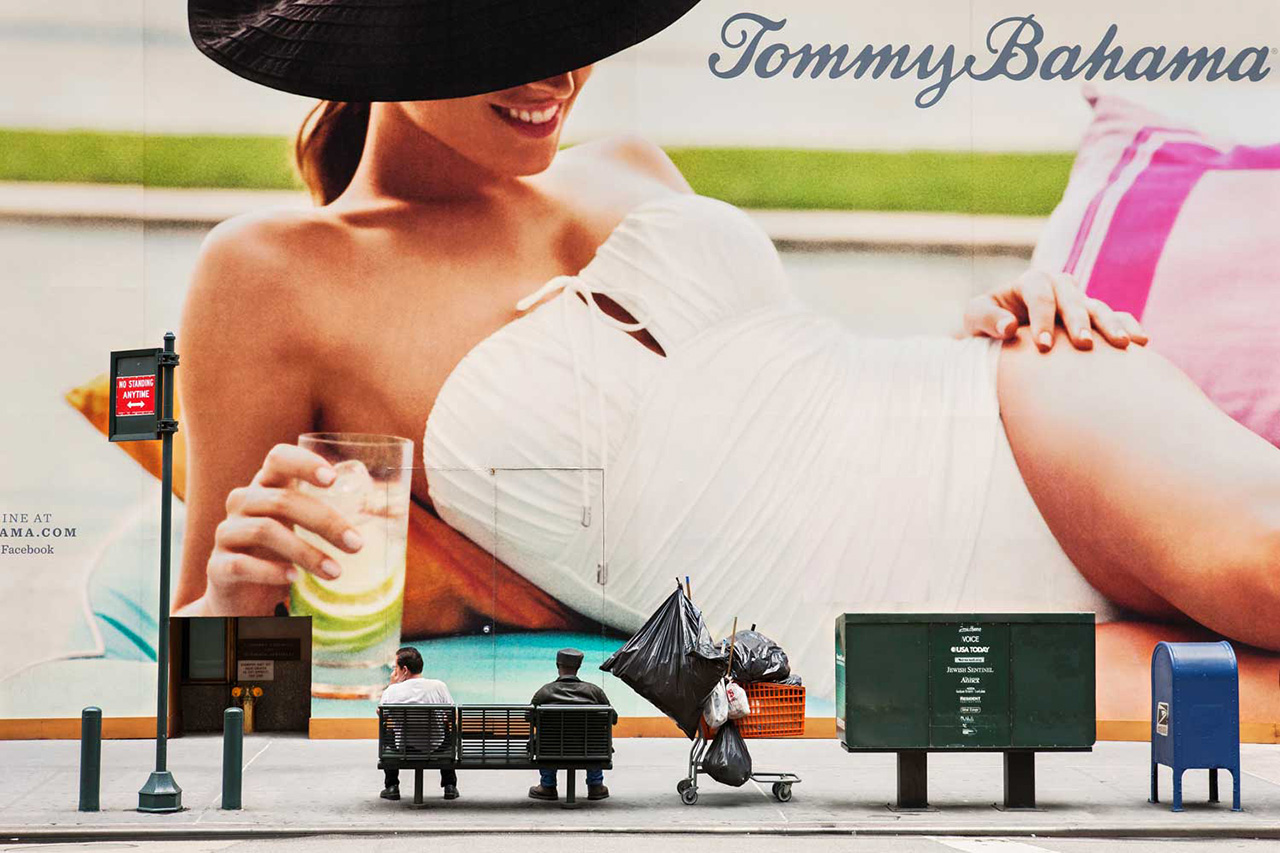

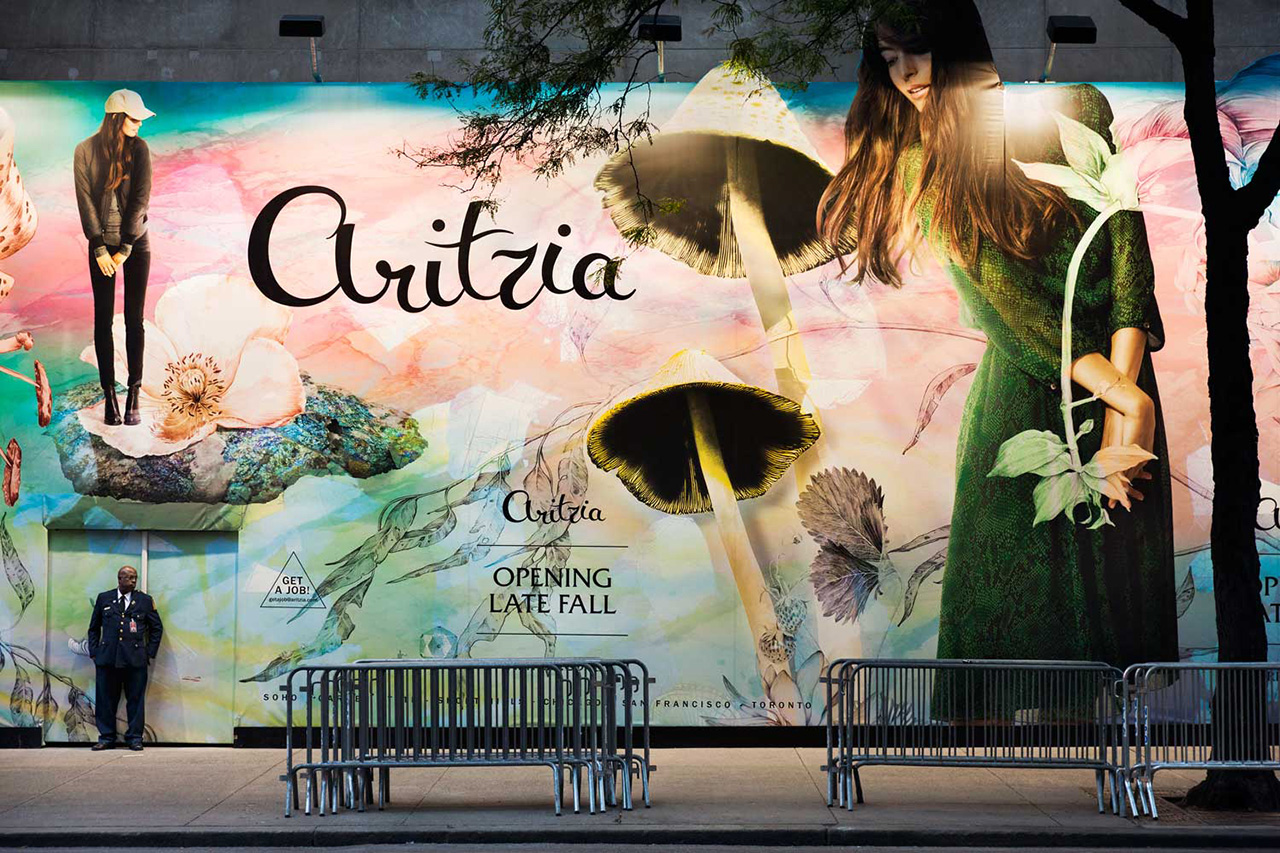

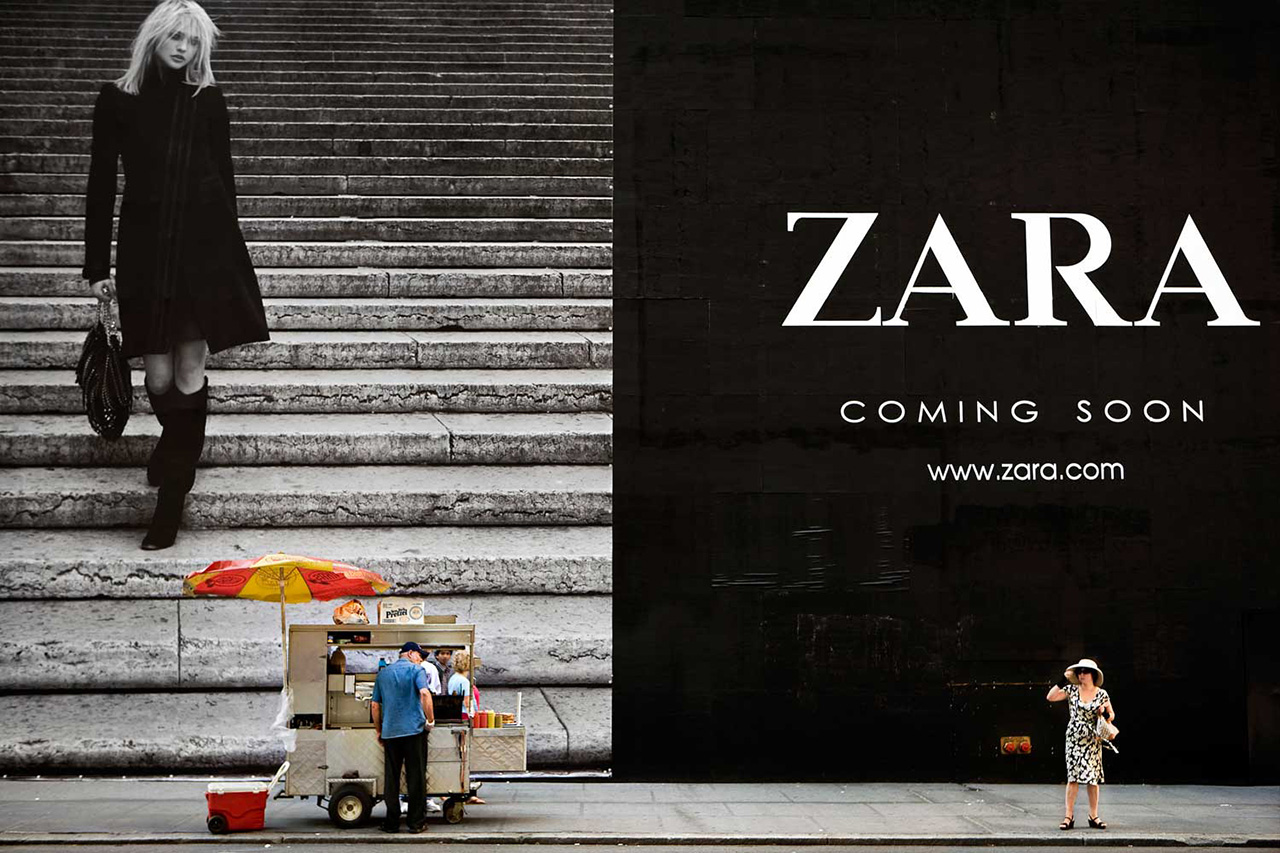

Coming Soon

In recent years, a kaleidoscopic net of huge billboards has enveloped the commercial hubs of New York City. The branding of the cityscape has become so ubiquitous, that the colorful, monumental advertisements, looming over the narrow streets, seem to be virtually unnoticed by the passersby. Giant billboards both dominate the urban landscape and blend into the background. Always in the peripheral vision, these ads turn the people moving through the space into passive spectators. The grasp is democratic and compulsory –the outdoor advertisements cannot be turned off and are able to reach a diverse public whose movements through the city momentarily overlap.

The effectiveness of outdoor billboards is juxtaposed with their impermanence; most are replaced after several weeks. The ephemeral nature, massive size and saturated colors of the ads create a fluid cinematic experience for the observer. People inhabiting the space underneath are pulled, unaware, into a staged set, the reality of the street merging with the commercial fantasy of the advertisements. Coming Soon is an exploration of our visual relationship with the branded city centers and the commercial environment we live in.

Natan Dvir (Nahariya, 1972). Lives in New York and works all around the world. He received a master’s degree in Business Administration from Tel Aviv University and a master´s degree in Photography from the School of Visual Arts, NY, after which he became a faculty member at the International Center for Photography (ICP). As a photographer he focuses on the human aspects of political, social and cultural issues. His work has been exhibited all over the world in solo and group exhibitions and has been published by leading international magazines.

Natan Dvir (Nahariya, 1972). Lives in New York and works all around the world. He received a master’s degree in Business Administration from Tel Aviv University and a master´s degree in Photography from the School of Visual Arts, NY, after which he became a faculty member at the International Center for Photography (ICP). As a photographer he focuses on the human aspects of political, social and cultural issues. His work has been exhibited all over the world in solo and group exhibitions and has been published by leading international magazines. [core_state] => 1 [core_access] => 1 [core_metadata] => {"robots":"","author":"Natan Dvir","rights":"","xreference":""} [core_created_user_id] => 841 [core_created_by_alias] => [core_created_time] => 2014-09-23 21:54:34 [core_images] => {"image_intro":"images\/categories\/open-content\/comingsoon.jpg","float_intro":"","image_intro_alt":"","image_intro_caption":"","image_fulltext":"images\/categories\/open-content\/comingsoon.jpg","float_fulltext":"","image_fulltext_alt":"","image_fulltext_caption":""} [core_modified_time] => 2016-06-22 18:25:52 [core_language] => en-GB [core_catid] => 37 [core_publish_up] => 2014-09-23 21:52:42 [core_publish_down] => 0000-00-00 00:00:00 [content_type_title] => Article [router] => ContentHelperRoute::getArticleRoute [author] => [author_email] => [link] => index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=196:coming-soon&catid=37&lang=en-GB [displayDate] => 2014-09-23 21:52:42 [event] => stdClass Object ( [afterDisplayTitle] => [beforeDisplayContent] => [afterDisplayContent] => ) [text] =>

Coming Soon

In recent years, a kaleidoscopic net of huge billboards has enveloped the commercial hubs of New York City. The branding of the cityscape has become so ubiquitous, that the colorful, monumental advertisements, looming over the narrow streets, seem to be virtually unnoticed by the passersby. Giant billboards both dominate the urban landscape and blend into the background. Always in the peripheral vision, these ads turn the people moving through the space into passive spectators. The grasp is democratic and compulsory –the outdoor advertisements cannot be turned off and are able to reach a diverse public whose movements through the city momentarily overlap.

The effectiveness of outdoor billboards is juxtaposed with their impermanence; most are replaced after several weeks. The ephemeral nature, massive size and saturated colors of the ads create a fluid cinematic experience for the observer. People inhabiting the space underneath are pulled, unaware, into a staged set, the reality of the street merging with the commercial fantasy of the advertisements. Coming Soon is an exploration of our visual relationship with the branded city centers and the commercial environment we live in.

Natan Dvir (Nahariya, 1972). Lives in New York and works all around the world. He received a master’s degree in Business Administration from Tel Aviv University and a master´s degree in Photography from the School of Visual Arts, NY, after which he became a faculty member at the International Center for Photography (ICP). As a photographer he focuses on the human aspects of political, social and cultural issues. His work has been exhibited all over the world in solo and group exhibitions and has been published by leading international magazines.

Natan Dvir (Nahariya, 1972). Lives in New York and works all around the world. He received a master’s degree in Business Administration from Tel Aviv University and a master´s degree in Photography from the School of Visual Arts, NY, after which he became a faculty member at the International Center for Photography (ICP). As a photographer he focuses on the human aspects of political, social and cultural issues. His work has been exhibited all over the world in solo and group exhibitions and has been published by leading international magazines. [id] => 196 [language] => en-GB [catid] => 37 [jcfields] => Array ( ) ) 1

Dina Litovsky

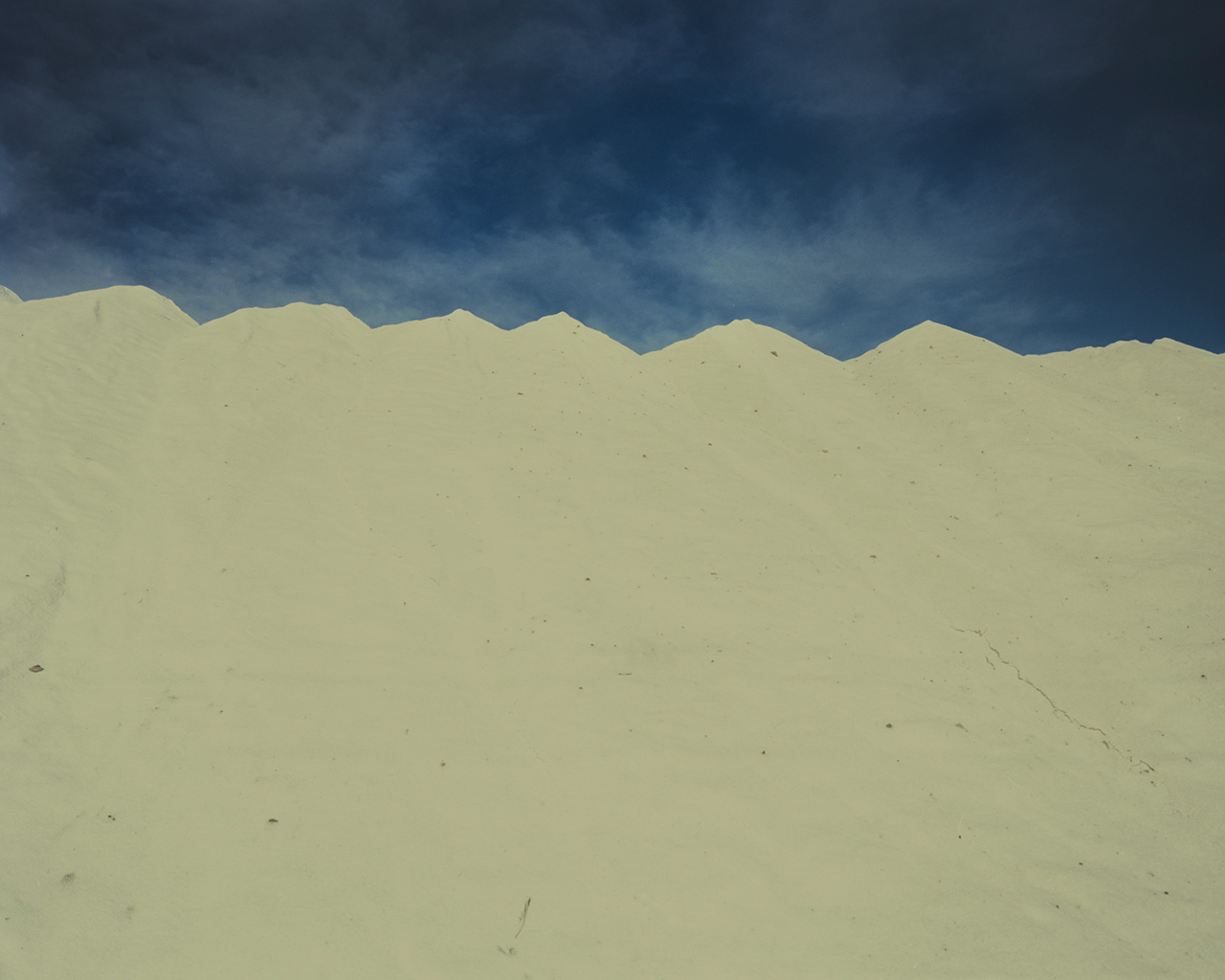

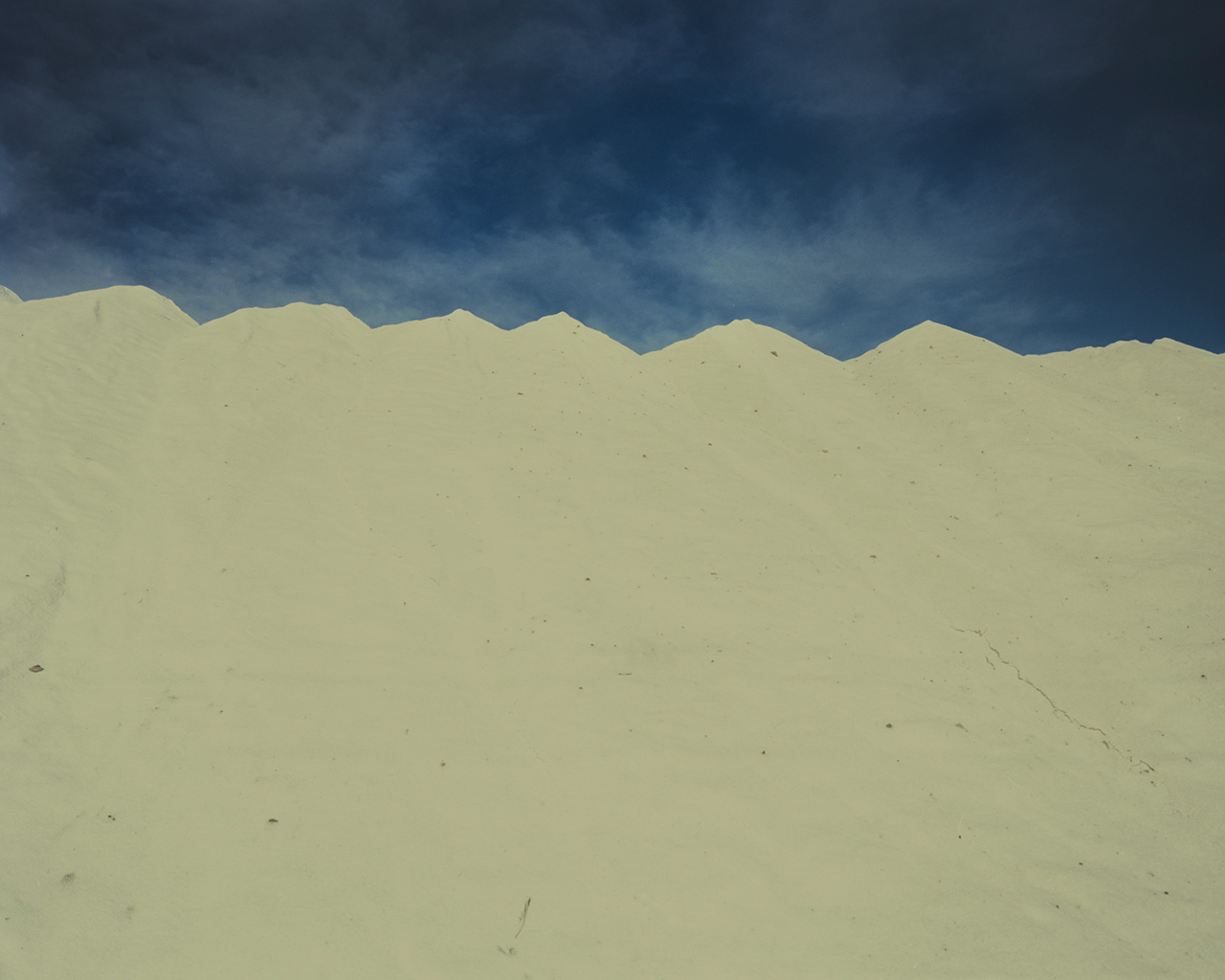

The barren emptiness of the desert is devoid of sentiment. There is no poetry in the dried up surface, no melancholy stirred up by the gusts of fine sand. On a beach or in a forest, in a green field or in an architectural wonder of a city, one is overwhelmed by the beauty of the environment, the lyricism of associations and memories. But in the sudden vacuum of a desert whiteout there is only isolation.

As the sun is blocked out by the dust and the horizon is swept away, the first anxious moment of helplessness metamorphoses into a feeling of unbounded freedom. In this vast, disorienting silence, one is left entirely to the immediacy of the experience.

It is rare to find a space lacking the external noise of over-stimulation. But it is necessary in order to hear oneself better. The isolation of the whiteout brings introspection and resets the senses. The sterility of the desert becomes an oasis.

Dina Litovsky (Ukraine, 1980). Dina Litovsky’s work examines social performances and group interactions in both public and private spaces. Dina was born in Ukraine and moved to New York in 1991. After receiving her bachelor degree in Psychology from NYU, Dina turned to photography and earned her MFA graduate degree in Photography from the School of Visual Arts, NY in 2010.

Dina Litovsky (Ukraine, 1980). Dina Litovsky’s work examines social performances and group interactions in both public and private spaces. Dina was born in Ukraine and moved to New York in 1991. After receiving her bachelor degree in Psychology from NYU, Dina turned to photography and earned her MFA graduate degree in Photography from the School of Visual Arts, NY in 2010.

The barren emptiness of the desert is devoid of sentiment. There is no poetry in the dried up surface, no melancholy stirred up by the gusts of fine sand. On a beach or in a forest, in a green field or in an architectural wonder of a city, one is overwhelmed by the beauty of the environment, the lyricism of associations and memories. But in the sudden vacuum of a desert whiteout there is only isolation.

As the sun is blocked out by the dust and the horizon is swept away, the first anxious moment of helplessness metamorphoses into a feeling of unbounded freedom. In this vast, disorienting silence, one is left entirely to the immediacy of the experience.

It is rare to find a space lacking the external noise of over-stimulation. But it is necessary in order to hear oneself better. The isolation of the whiteout brings introspection and resets the senses. The sterility of the desert becomes an oasis.

Dina Litovsky (Ukraine, 1980). Dina Litovsky’s work examines social performances and group interactions in both public and private spaces. Dina was born in Ukraine and moved to New York in 1991. After receiving her bachelor degree in Psychology from NYU, Dina turned to photography and earned her MFA graduate degree in Photography from the School of Visual Arts, NY in 2010.

Dina Litovsky (Ukraine, 1980). Dina Litovsky’s work examines social performances and group interactions in both public and private spaces. Dina was born in Ukraine and moved to New York in 1991. After receiving her bachelor degree in Psychology from NYU, Dina turned to photography and earned her MFA graduate degree in Photography from the School of Visual Arts, NY in 2010.Eric Kim

Eric Kim, "Debunking the “Myth of the Decisive Moment”", Eric Kim Street Photography Blog , May 23, 2014

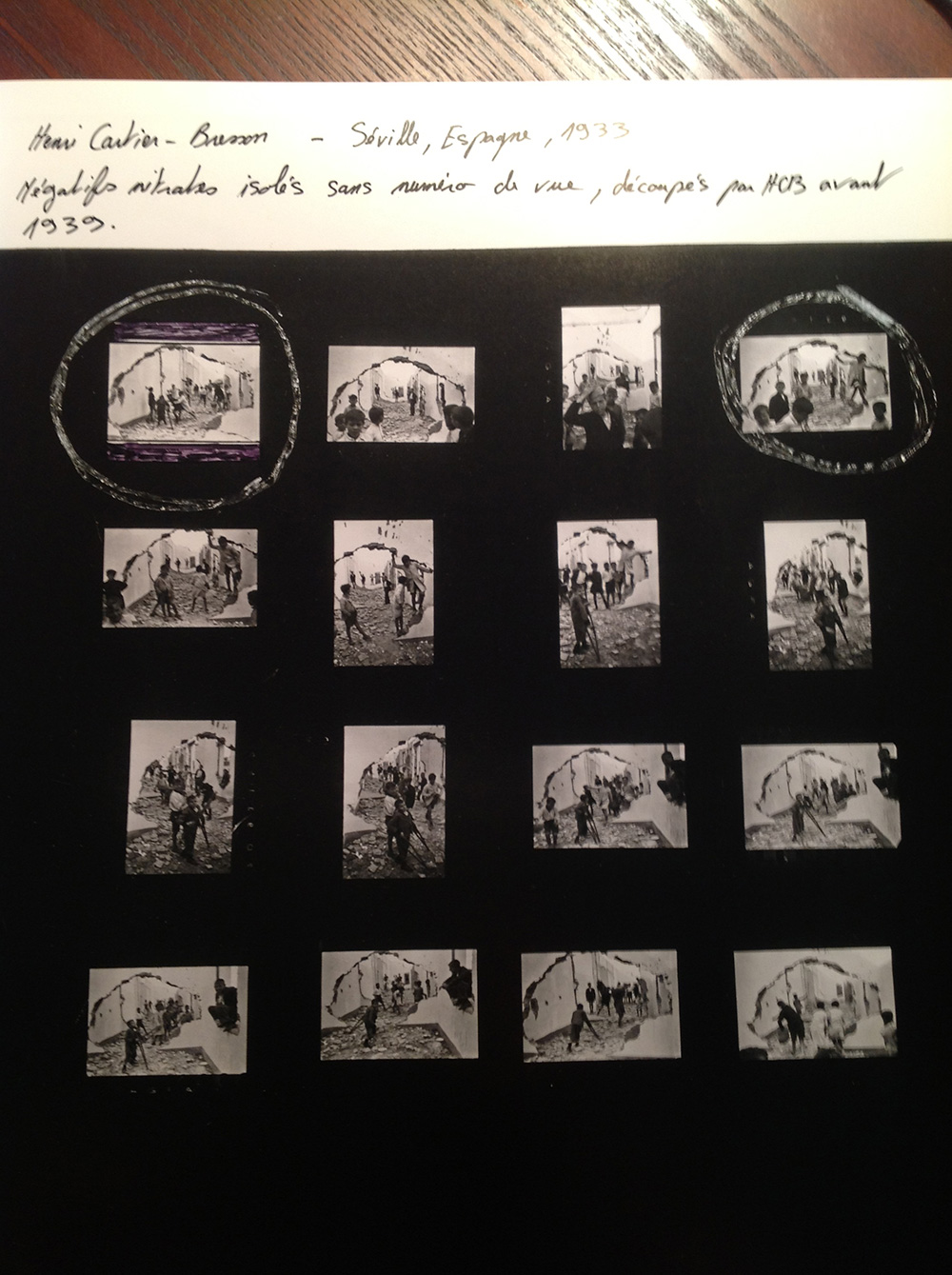

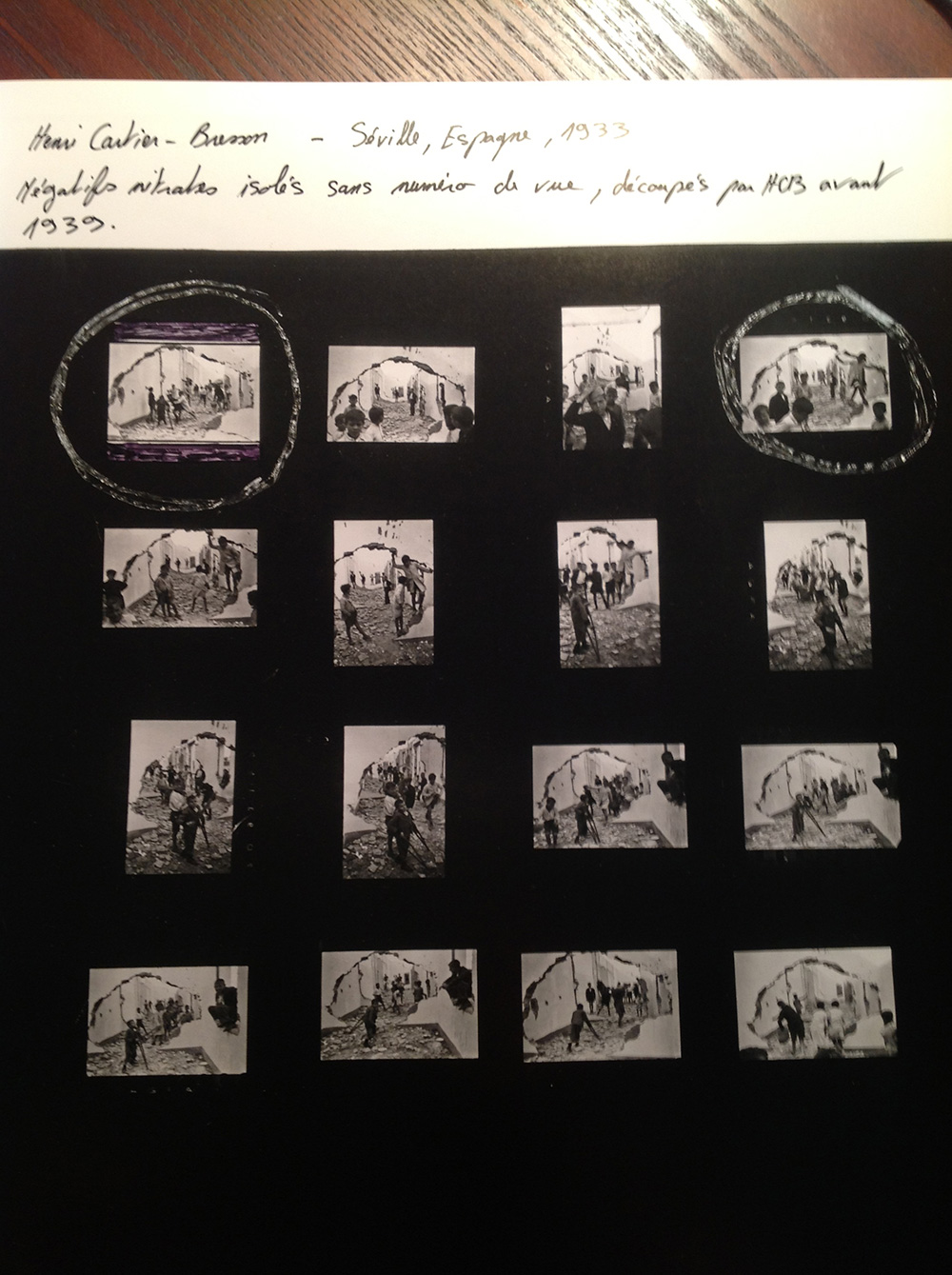

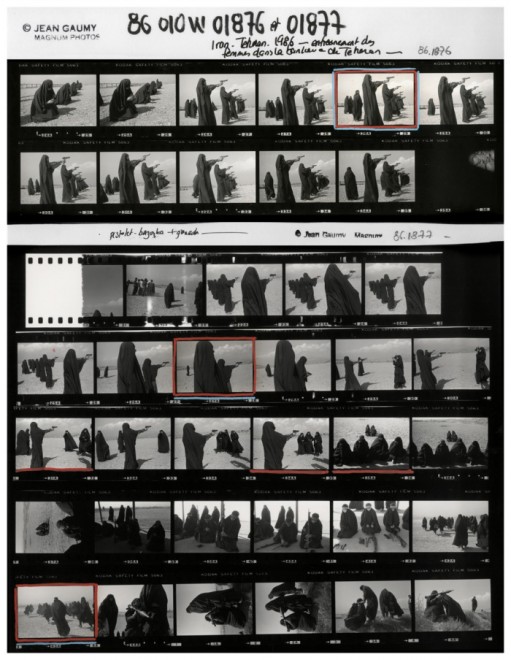

Contact sheet from Henri Cartier-Bresson in Seville, Spain, 1933. © Henri Cartier-Bresson / Magnum Photos

When I started off in street photography, I believed in the “myth of the decisive moment”. What do I mean by that?

Well, when I first heard of “The Decisive Moment” by Henri Cartier Bresson, I had the wrong impression that he only took one photo of a scene. I imagined Henri Cartier Bresson waltzing into a street scene, carefully aiming his Leica, and taking only one shot and creating masterpieces. I thought he was a demigod– a photographer who somehow had this magic behind his lens.

However if we look at his contact sheets, it is a different story. He (and almost all great photographers) never only take one photo of a great potential scene. Out of Henri Cartier Bresson’s contact sheets, you can see that almost all of his great images required him “working the scene”– taking multiple photos of the same scene at different angles, moments, and perspectives. He hustled hard to get the shots he wanted– and would spend considerable time with his contact sheets, determining which photos he decided were his “best”.

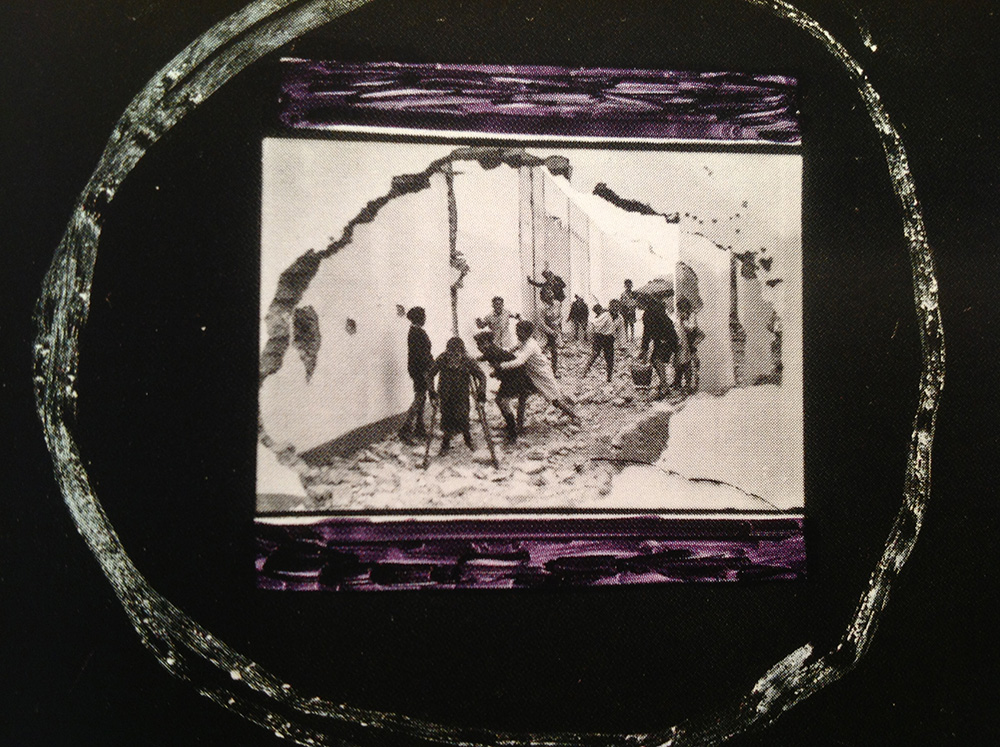

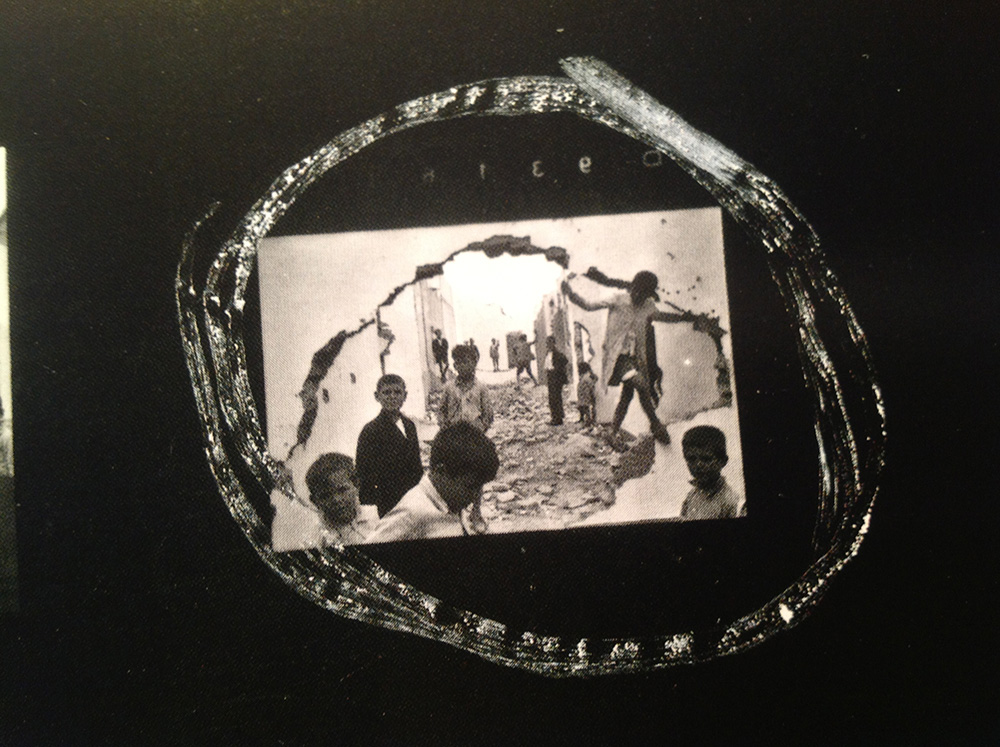

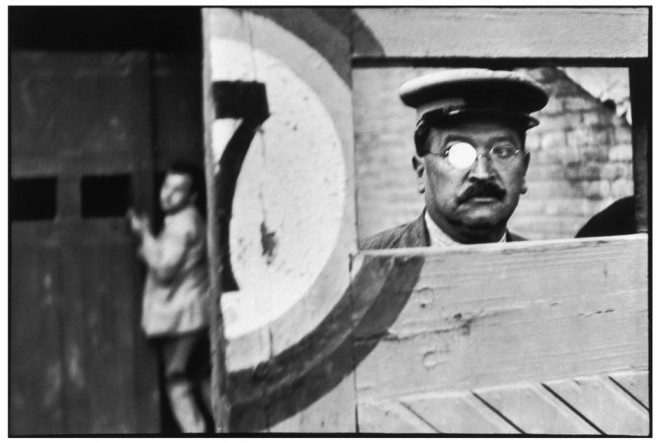

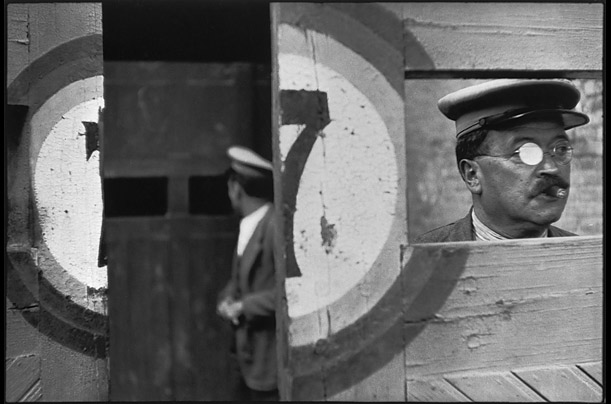

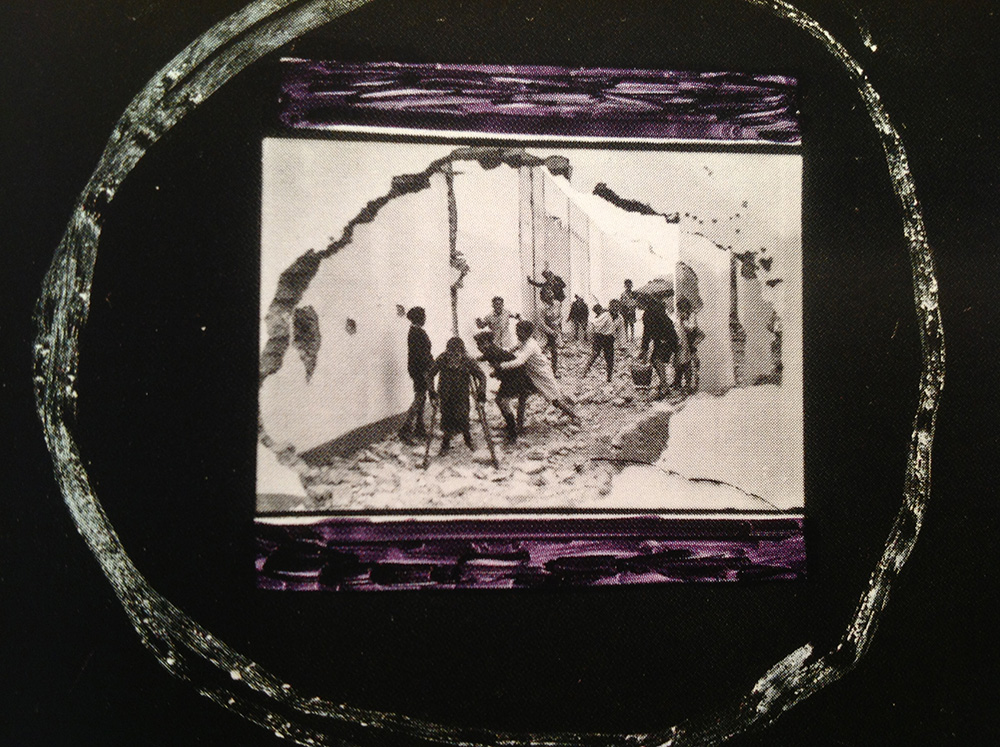

Close-ups of the contact sheet from Seville, by Henri Cartier-Bresson:

One mistake that I see a lot of beginner street photographers is that they only take one photo per scene. I think this is because they too believe in the “myth of the decisive moment” and partly because of the fear that they will be caught taking photographs.

The importance of studying contact sheets

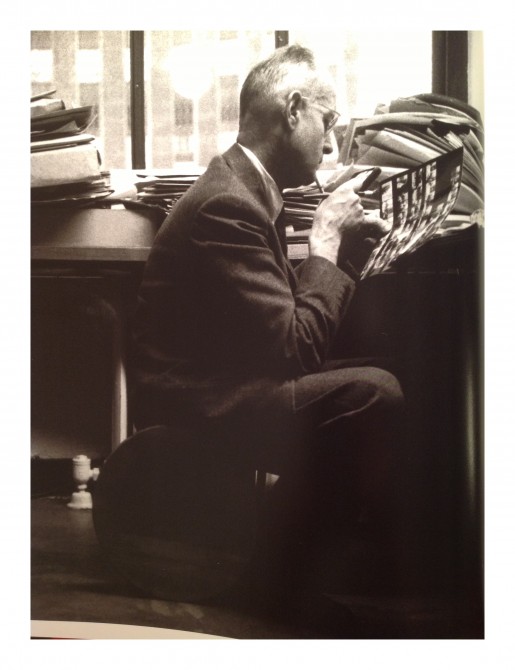

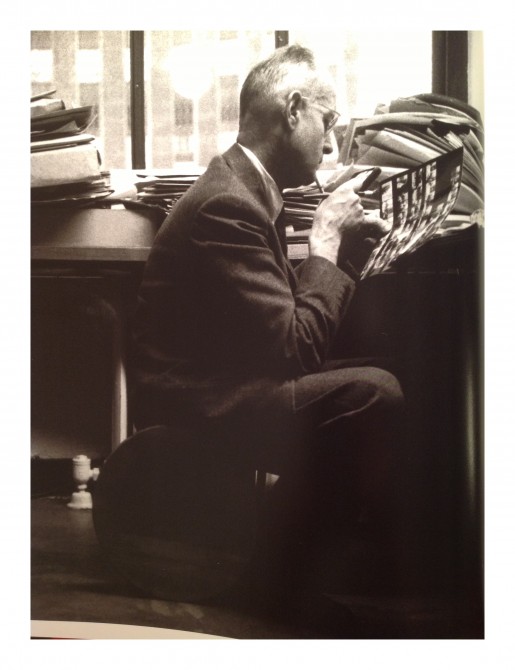

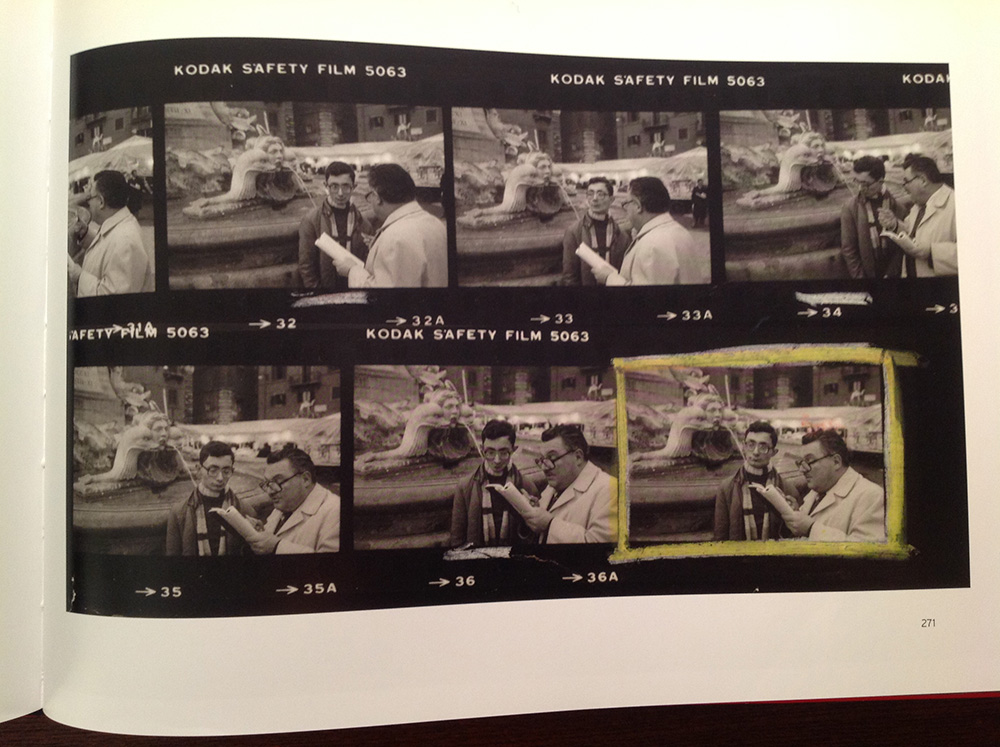

Henri Cartier-Bresson looking at contacts at the New York Magnum Office. 1959. © Rene Burri / Magnum Photos

I have written about contact sheets several times before. For those of you who aren’t familiar with what a contact sheet is it is pretty much a sheet of paper which shows all the photographs a photographer shot on a roll of film. And with this sheet of paper, a photographer can use a loupe (small magnifying glass for the eye) and edit (choose) their favorite images. This was done in the days of the darkroom, and when digital didn’t exist.

Now of course, we have “Lightroom” where we can identify all of our photos of a scene digitally. Instead of having to look at tiny thumbnails, we can now see all of our “almost” photos in full resolution.

Contact sheets are the best learning tools for a photographer. You can learn from contact sheets from other photographers, and also from your own contact sheets.

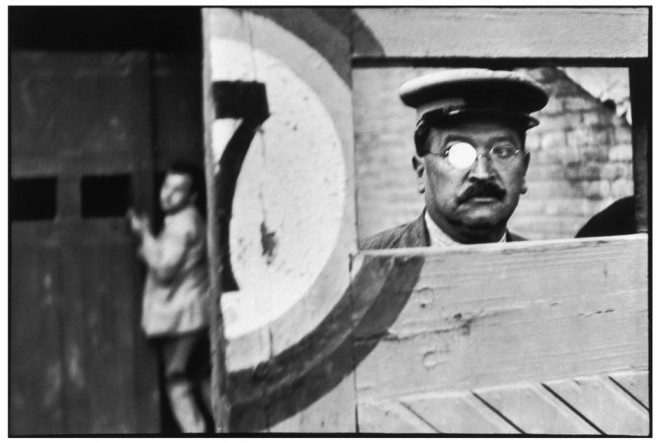

Henri Cartier-Bresson. SPAIN. 1933. Valencia. Note the two versions of the photo he was considering from. This was the best.

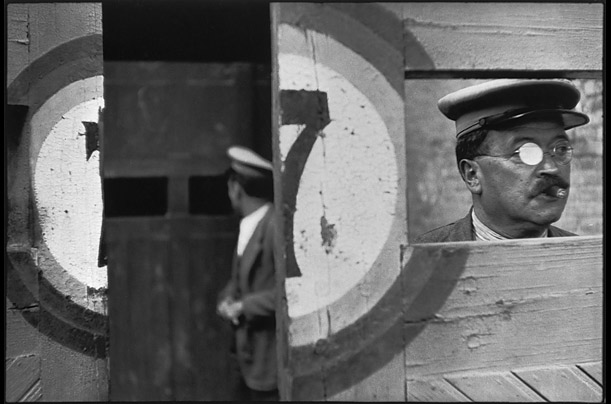

Henri Cartier-Bresson. SPAIN. 1933. Valencia. This image wasn’t as strong as the prior.

Analyzing contact sheets from the masters who came before us is the closest thing we have to reading their minds. We can see how they “worked the scene”– and how they took photos from different perspectives, decided when to hit the shutter, and how many photos they decided to take. Some photographers are able to “nail” their photos in just 5-6 shots, while other photographers will shoot a full roll of 36 photos in just one scene.

Realize that all these master photographers were shooting on film, where it actually cost something to photograph. Now that most of us shoot digitally, there is no excuse for us to not “work the scene” and take many different photos of the same scene.

To learn more about contact sheets, check out my article: “10 Things Street Photographers Can Learn From Magnum Contact Sheets” and also pick up a copy of “Magnum Contact Sheets” on Amazon. It will be the best $100 you will ever spend for your photographic education.

How to “work the scene”

Okay, so we’ve talked about the importance of “working the scene”– and how important it is to take multiple photos of a scene (not just one photo). So how do you exactly “work the scene”?

A few things to clarify:

1. Don’t only just take one photo

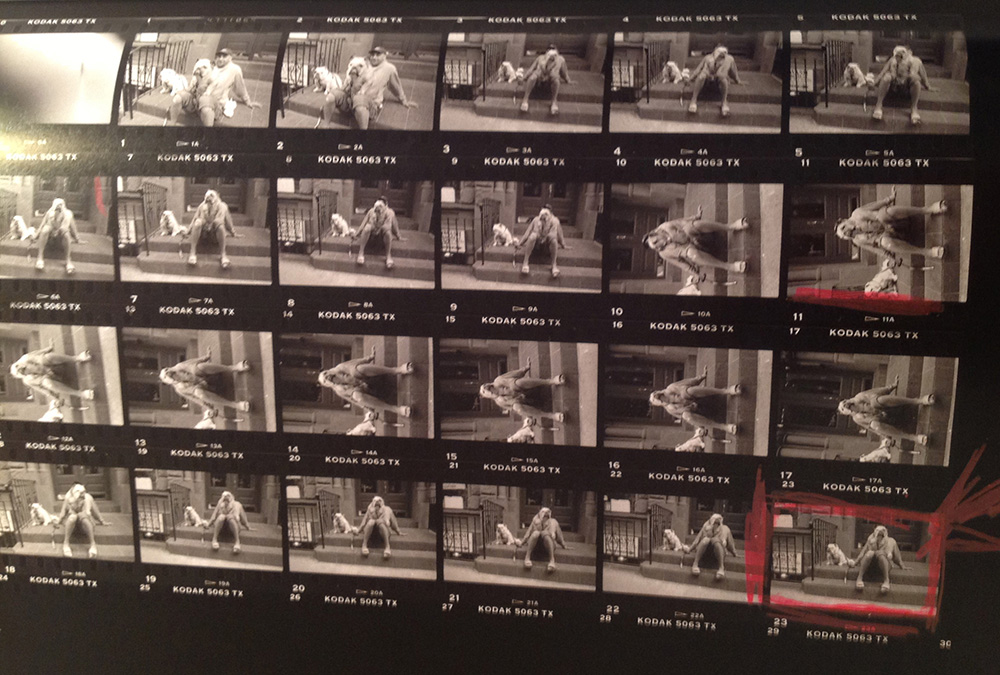

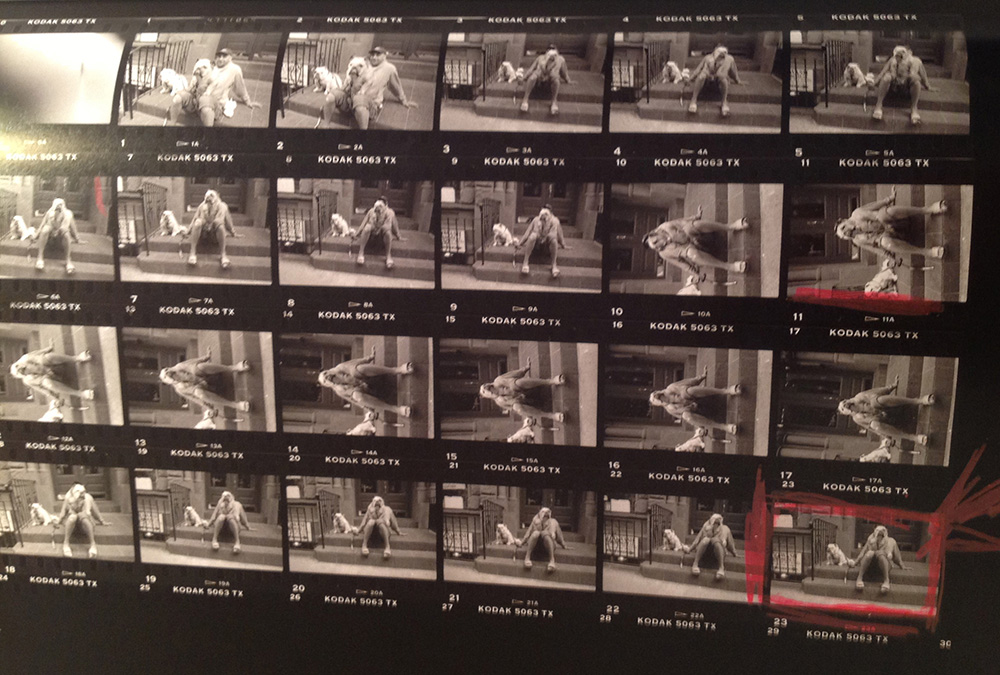

Contact sheet of Elliott Erwitt, “Bulldogs”, New York, 2000. © Elliott Erwitt / Magnum Photos

Once again, it is very tempting to only the one photograph when you see a good scene. When I started off in street photography, I would be deathly afraid of offending people or being “caught in the act” of photographing strangers.

However realize that to make a great photograph, you need to work the scene. You will never know when the “best” decisive moment will occur. In a scene, there are many different great potential “decisive moments”. You generally only know which is the best “decisive moment” afterwards in the editing phase.

“Bulldogs”, New York, 2000. © Elliott Erwitt / Magnum Photos

Even Henri Cartier Bresson once said: “Sometimes you have to milk the cow a lot to get a little bit of cheese.”

2. Don’t chimp

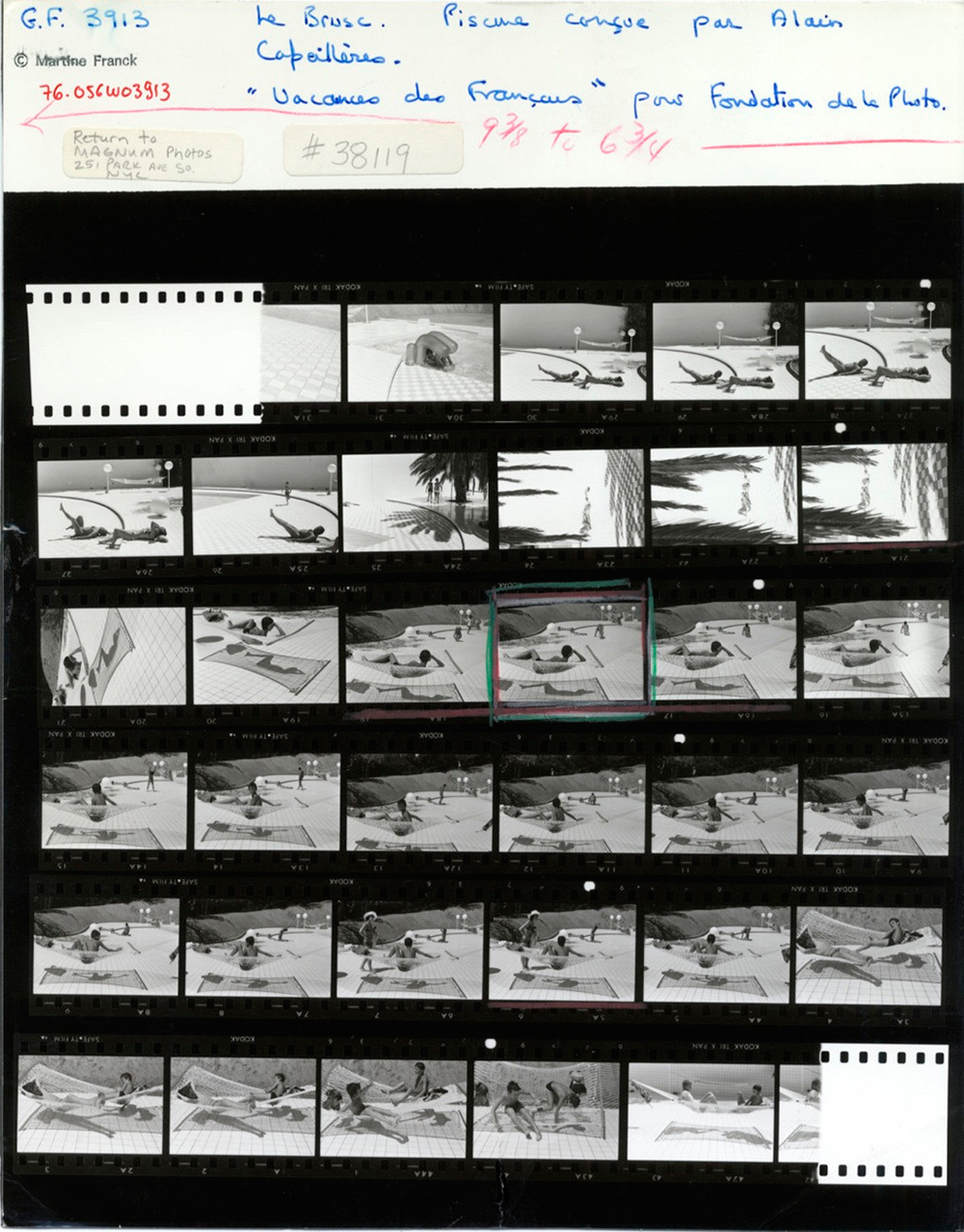

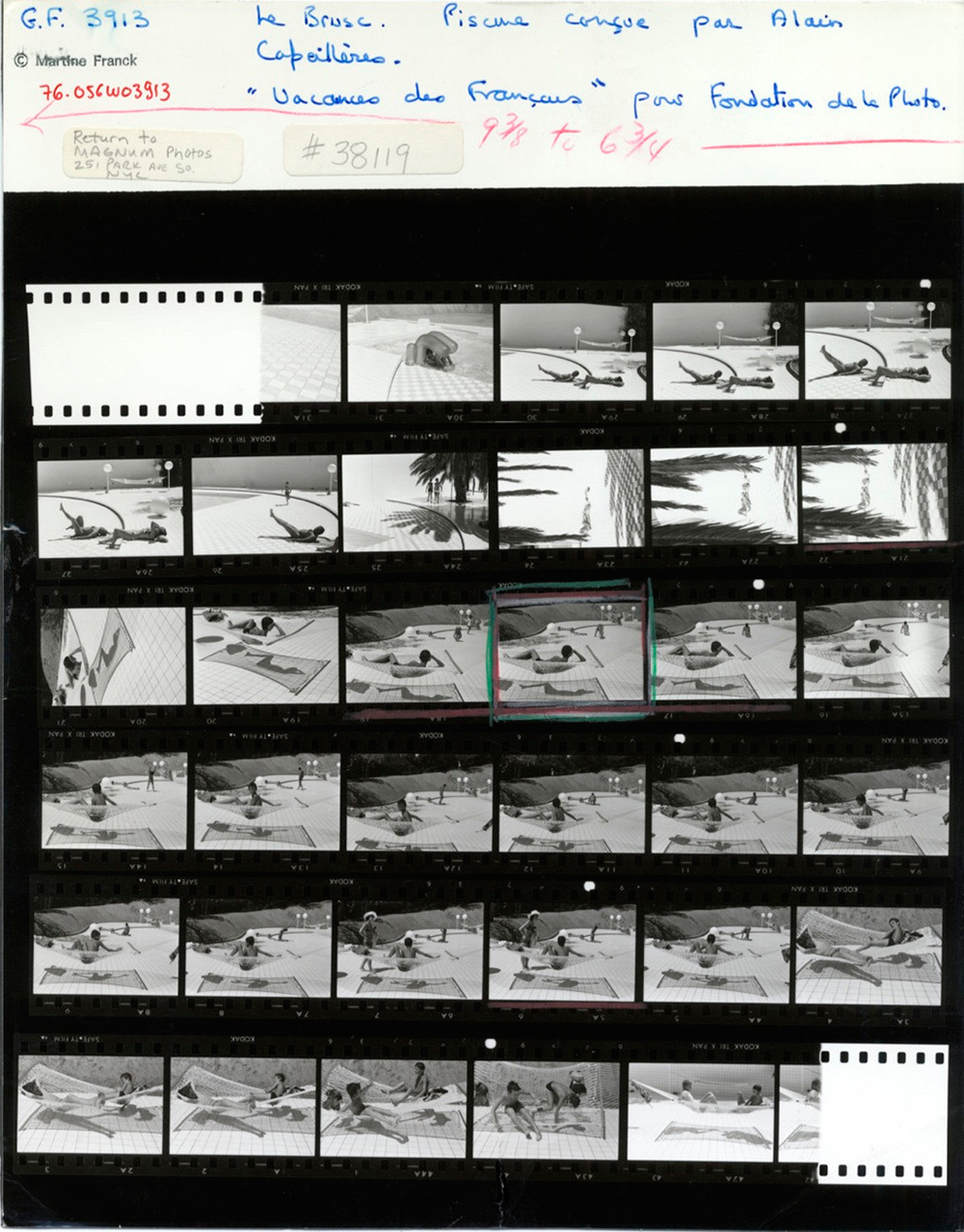

Alain Capeilleres, 1976. © Martine Franck / Magnum Photos.

Another practical tip to better “work the scene” is to not “chimp”. What is chimping you ask? Well, it is when you look at your LCD screen after you take a photograph. Why do they call that “chimping”? Well, apparently film photographers used to make fun of digital photographers by saying they looked like a bunch of “chimps” (or monkeys) when they would crowd around their LCD screens and show off the photos they just took.

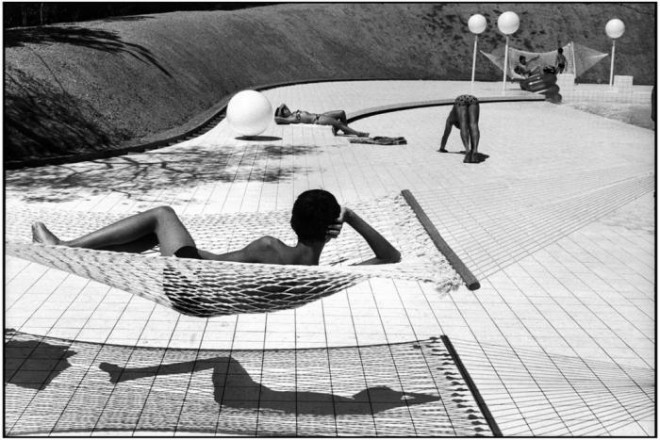

Photo by Martine Franck, Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur region. Town of Le Brusc. Pool designed by Alain Capeilleres, 1976. © Martine Franck / Magnum Photos

So what is so bad about “chimping” anyways? I’ve written an article on why street photographers shouldn’t chimp– but to sum up, chimping kills your flow when you’re out shooting on the streets. Rather than checking your LCD screen several times while working a scene to check for exposure, framing, and what you captured– it is better to just take a lot of photos at different angles and moments and choose the best photos later.

3. Linger

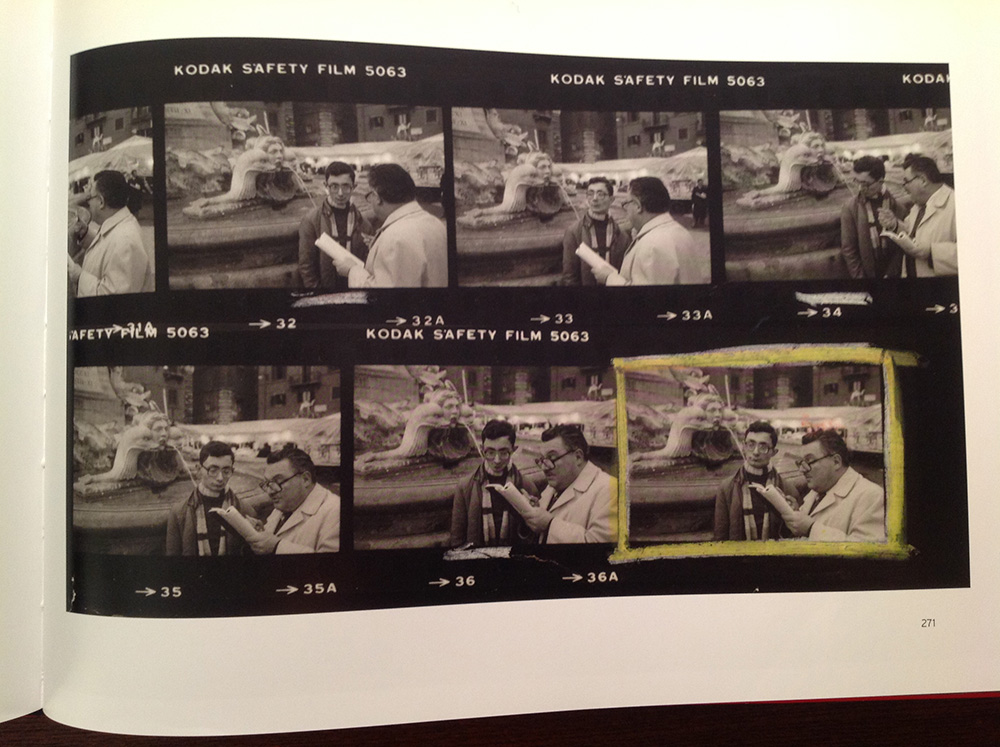

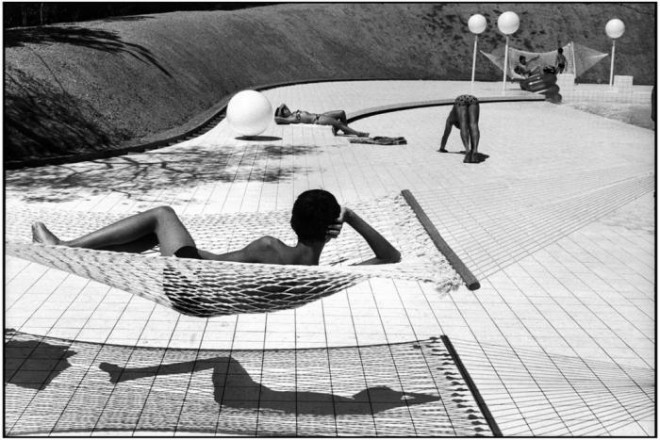

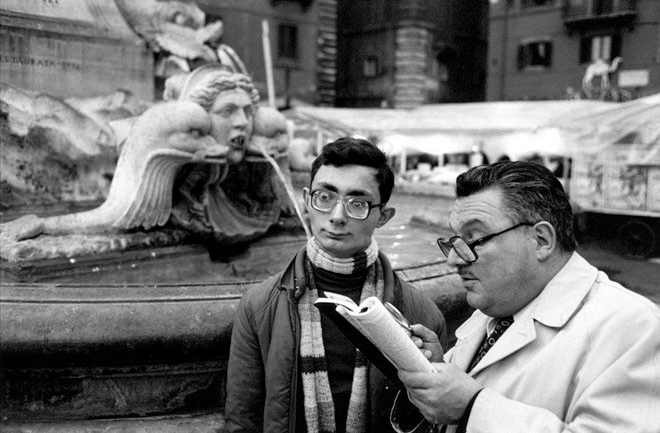

Contact sheet of Richard Kalvar, “Piazza Della Rotonda”. Rome, Italy, 1980. © Richard Kalvar / Magnum Photos

“Lingering” is one of the most difficult things about “working the scene”. Lingering is to “overstay your welcome”. It is generally rude to “linger”. Lingering is like “loitering”– you hang around longer than you should, and people look down on it.

One of the most frequently asked questions I get in my workshops is, “How long should I ‘work a scene’ and linger before I know it’s time to leave, or I got the shot?”

Well, that is the big problem. We have no idea when we either “got the shot” or we’ve hung around “long enough”.

Personally, my philosophy is to be the houseguest that overstays his or her welcome. Did you ever have a friend who asked to stay at your place for a week but ends up staying a few months? Be that guy.

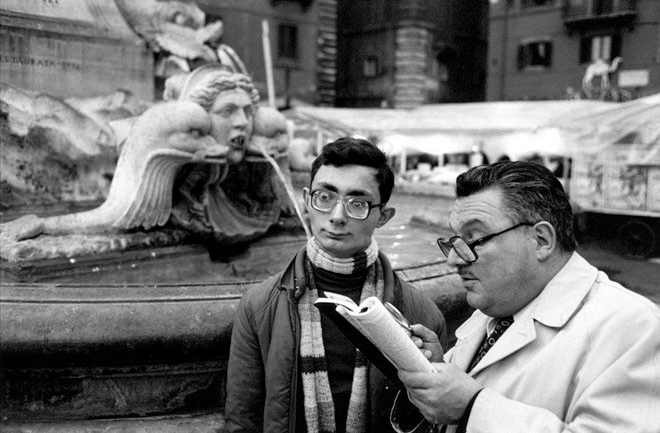

“Piazza Della Rotonda”. Rome, Italy, 1980. © Richard Kalvar / Magnum Photos

The reason I advocate for “overstaying your welcome” is because it is better to linger for a longer period of time because often your best shot will be the last shot. Looking at a lot of contact sheets, especially this image by Richard Kalvar, you see that his best image was at the very end (on his 37th frame, quite lucky). If he didn’t linger around and work the scene, he would’ve never gotten his iconic shot.

Furthermore in street photography, you will only see a great potential scene once in your life. You might see similar scenes, but you will never see the same exact scene with the same exact people, with that background, that light, and that configuration.

So don’t live with regrets, linger around longer than you should– and “overshoot” a scene.

A technique I learned from my friend Charlie Kirk is if you see a great potential scene, hang around and wait a bit longer before you go in and start taking photos. For example, if you see a cool looking guy smoking– linger around him and wait for him to take a puff– then jump in and take a few shots of him inhaling his cigarette.

Lingering is quite painful to do. It is awkward, makes you feel uncomfortable, and might make your subject feel uncomfortable.

One way I get over the awkwardness of lingering and “working the scene” is by pretending I am photographing something behind them and avoiding eye contact. Because I shoot with a 35mm lens, I don’t have to point my camera directly at my subject to get them in the frame.

Another technique is to smile and interact with my subject while photographing them. For example, if I see a good scene, I might start off by shooting candidly– then if my subject makes eye contact with me, I will also make eye contact, smile, keep shooting, and even start chatting with them (hey, you’re looking good!)

4. Look for gestures

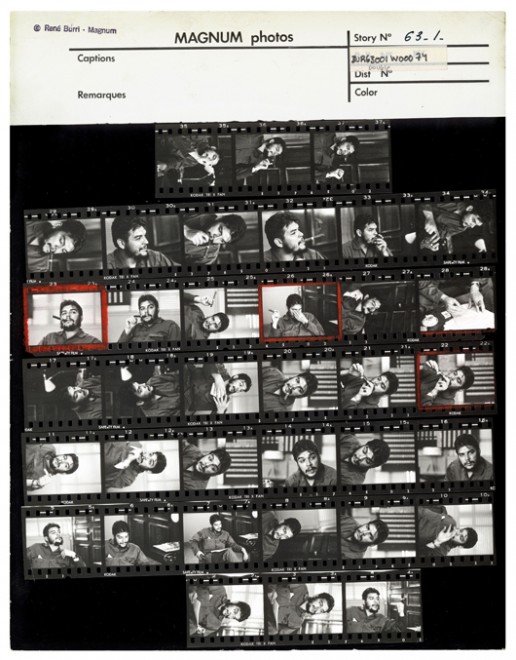

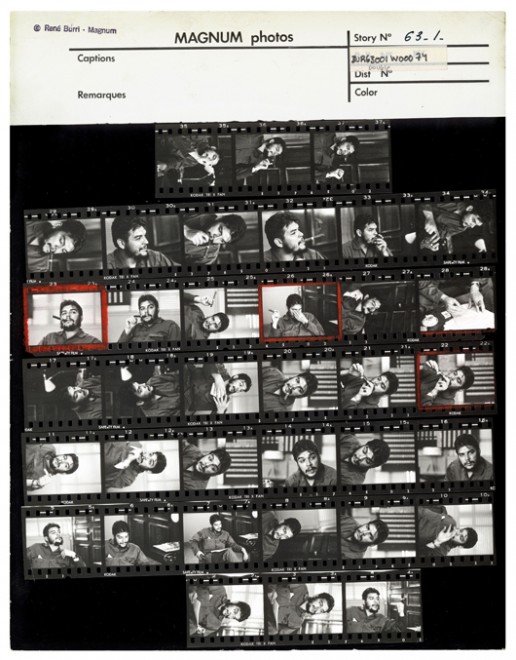

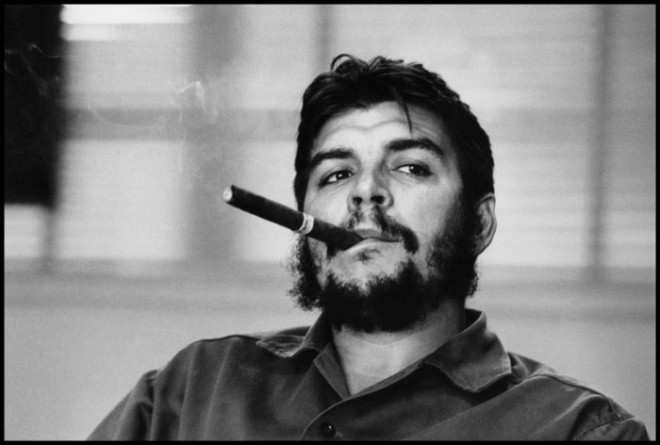

Che contact sheet. © Rene Burri / Magnum Photos

When you are “working the scene”– don’t just put your camera to rapid fire mode and start shooting aimlessly. Rather, be very conscious about when you decide to click the shutter.

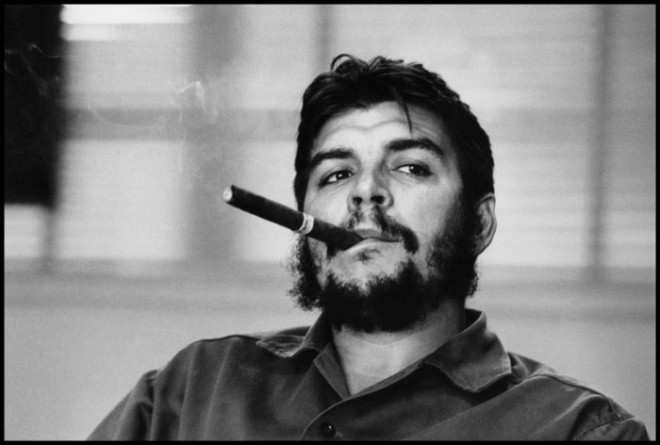

Che Guevara. © Rene Burri / Magnum Photos

Generally I make the decision to click the shutter when I see hand gestures. It can be a gesture of someone covering their face, holding their hands by their sides, or pointing in a certain direction.

Another great tip is to wait for eye contact. Try experimenting taking photos without eye contact, and some photos with eye contact. You never know which photograph will be better. But there is a saying: “eyes are the windows to the soul”– which means if you get eye contact in your street photographs, they can be more intimate and emotional.

5. Keep your feet moving

If you ever watch a boxer, they rarely keep their feet still. The most important thing as a boxer is to never put your heels on the ground. The moment you stop moving is the moment you become a sitting duck– and will be a prime target to be knocked out by your opponent.

Take the same mindset as a street photographer. When working the scene, don’t just keep your feet planted on the ground. Keep your feet moving. Take photos from the left, right, take a step forward, a step backwards. Crouch down. Get different angles and perspectives.

6. Shoot both landscape and portrait photos

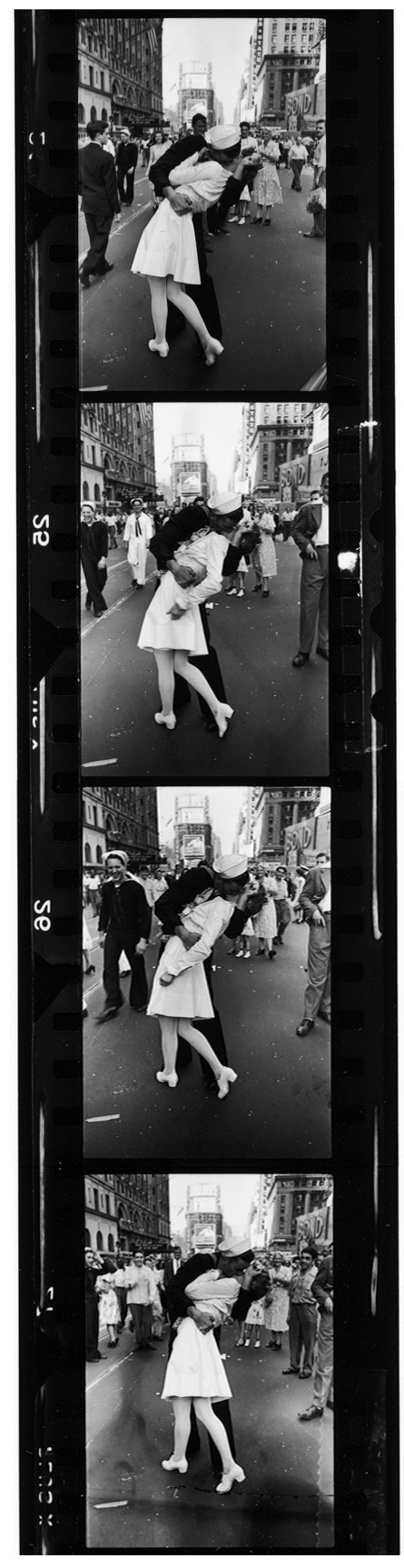

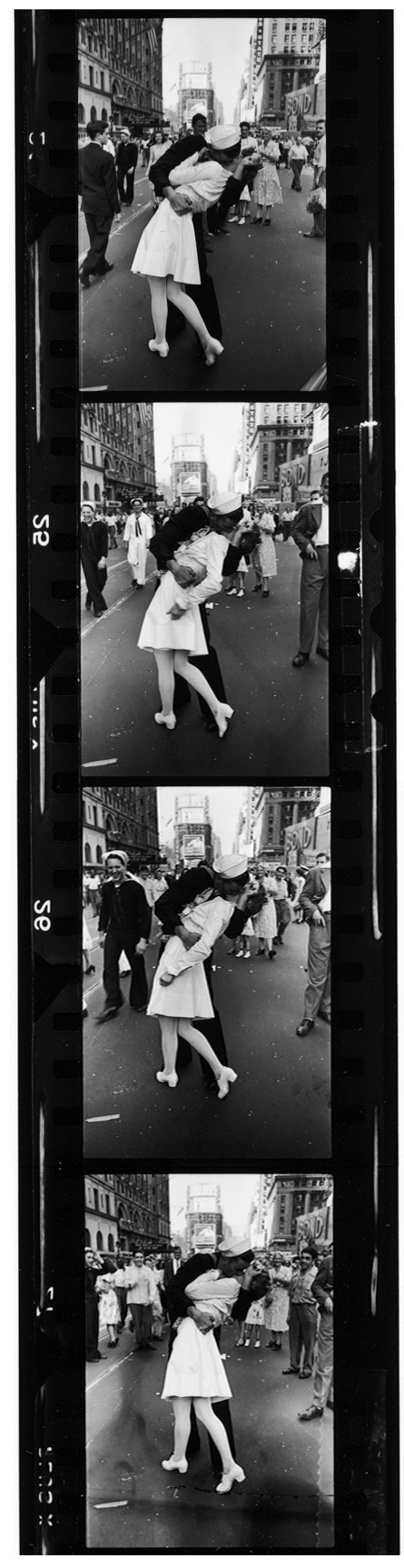

Contac sheet, VJ Day. Photo by Alfred Eisenstaedt

Also when working the scene, try experimenting taking your photos in both landscape (horizontal) and portrait (vertical) modes. When you are in the heat of the moment and see a great street photography scene, it is often difficult to know which is the “better” orientation of your camera for the scene.

So if you have time, try to work out both orientations of your camera– depending on what kind of image you want to create.

7. Be calm and patient

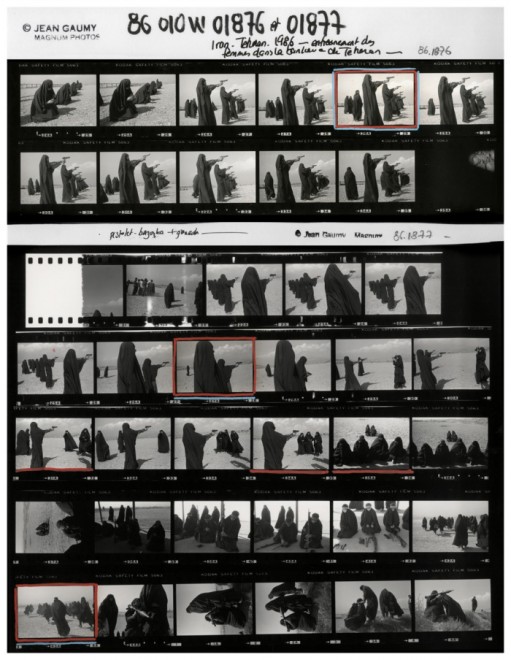

Jean Gaumy, Iran, 1986.

When you are working a scene, remember to try to stay calm and patient. We can sometimes get into a frenzy when working the scene, and trying to get “the shot”. However be calm and patient while you’re shooting– by analyzing when you need to hit the shutter, how close you need to be to your subject to frame them properly, and distracting elements in the background.

Jean Gaumy, Iran, 1986.

When you start off working the scene as a beginner, you might get too much of an adrenaline rush to stay calm and patient when shooting. But realize that with practice be time, you will be more calm and patient when working the scene– which will help you make better rational choices while shooting, and ultimately help you make better images.

8. Focus on the background

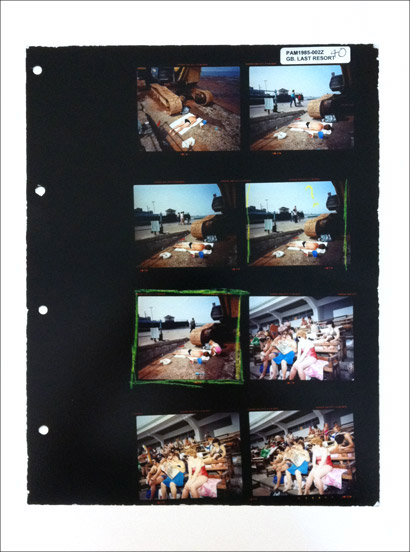

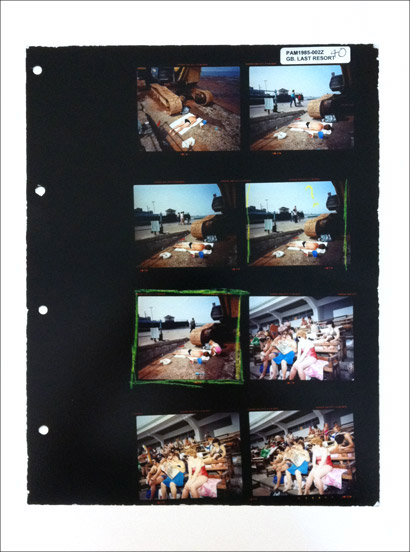

Martin Parr contact sheet from “The Last Resort“

When we are shooting on the streets, we can often focus too much on the subject and not enough on the background.

My advice is once you’ve established who your primary subject (or subjects) are– focus your eyes on the background. Try to get a clean background that doesn’t district– and adds to the scene.

The Last Resort, Photo by Martin Parr

Try to avoid getting random heads, poles, trees, or cars in the background. When you are working the scene, move your feet to get a cleaner background. Messy backgrounds are one of the biggest killers of great potential street photographs.

Conclusion

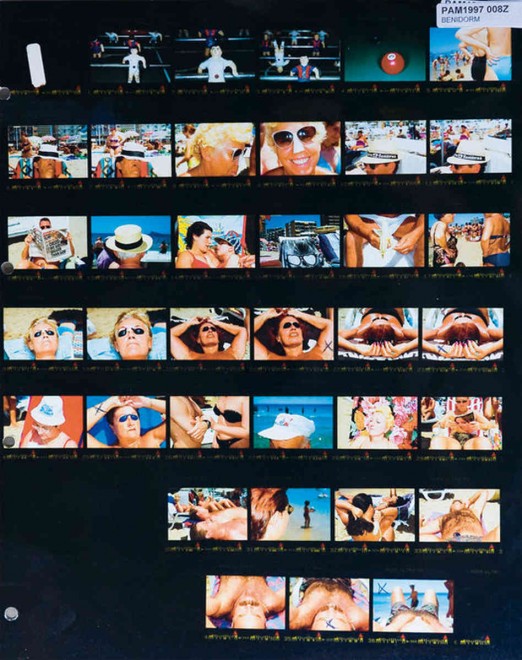

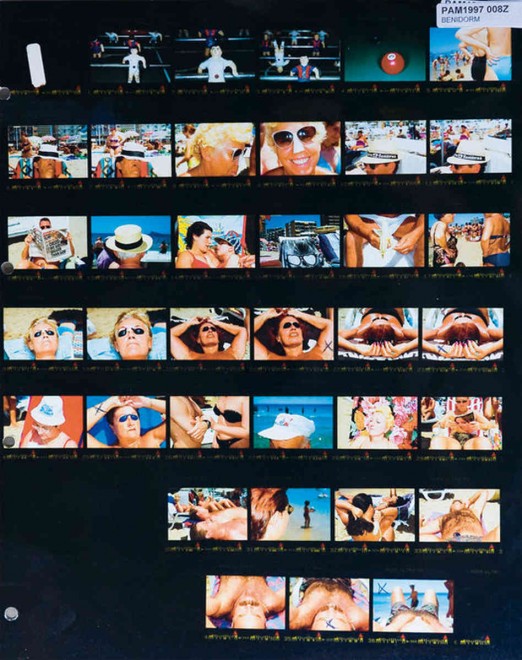

Contact Sheet by Martin Parr from Spain, 1997

To increase your odds of getting “keepers” in street photography, try practicing “working the scene” and lingering longer than necessary. Don’t keep your feet still, always be moving. But at the same time be patient.

Photo by Martin Parr from his “Common Sense” book. Spain, 1997

Also know that by working the scene longer than you need to, it will be strange and awkward. But with time, patience, practice, and a smile– you will be able to overcome this.

Learn more

To learn more, I recommend picking up a copy of “Magnum contact sheets” or reading the in-depth article I wrote on it: “10 Things Street Photographers Can Learn From Magnum Contact Sheets“. Also make sure to check out the “Contact Sheets” section at the Iconic Photos Blog.

If you want to build your confidence in street photography and learn to better “work the scene”– join me at one of my upcoming street photography workshops!

__

LEGAL INFORMATION: ALL THE PHOTOGRAPHS ARE DISPLAYED WITHOUT THE INTENTION OF FINANCIAL GAIN, AS SCIENTIFIC, LITERARY AND/OR ARTISTIC CRITICISM AND/OR RESEARCH, UNDER THE TERMS OF THE CURRENT LEGISLATION CONTAINED IN INTERNATIONAL TREATIES REGARDING COPYRIGHT.

Eric Kim (USA). Lives and works as a photographer in Berkeley, California. His main interest is street photography, to which he has devoted his artistic and educational work. He graduated in sociology from UCLA. Kim gives workshops in several parts of the world, including Canada, Holland, Vietnam, Japan and Australia, and has collaborated in a number of projects with Leica and Samsung. Hs work has been exhibited in Los Angeles and in Leica stores in Singapore, Seoul and Melbourne. and can be seen at: erickimphotography.com

Eric Kim (USA). Lives and works as a photographer in Berkeley, California. His main interest is street photography, to which he has devoted his artistic and educational work. He graduated in sociology from UCLA. Kim gives workshops in several parts of the world, including Canada, Holland, Vietnam, Japan and Australia, and has collaborated in a number of projects with Leica and Samsung. Hs work has been exhibited in Los Angeles and in Leica stores in Singapore, Seoul and Melbourne. and can be seen at: erickimphotography.comEric Kim, "Debunking the “Myth of the Decisive Moment”", Eric Kim Street Photography Blog , May 23, 2014

Contact sheet from Henri Cartier-Bresson in Seville, Spain, 1933. © Henri Cartier-Bresson / Magnum Photos

When I started off in street photography, I believed in the “myth of the decisive moment”. What do I mean by that?

Well, when I first heard of “The Decisive Moment” by Henri Cartier Bresson, I had the wrong impression that he only took one photo of a scene. I imagined Henri Cartier Bresson waltzing into a street scene, carefully aiming his Leica, and taking only one shot and creating masterpieces. I thought he was a demigod– a photographer who somehow had this magic behind his lens.

However if we look at his contact sheets, it is a different story. He (and almost all great photographers) never only take one photo of a great potential scene. Out of Henri Cartier Bresson’s contact sheets, you can see that almost all of his great images required him “working the scene”– taking multiple photos of the same scene at different angles, moments, and perspectives. He hustled hard to get the shots he wanted– and would spend considerable time with his contact sheets, determining which photos he decided were his “best”.

Close-ups of the contact sheet from Seville, by Henri Cartier-Bresson:

One mistake that I see a lot of beginner street photographers is that they only take one photo per scene. I think this is because they too believe in the “myth of the decisive moment” and partly because of the fear that they will be caught taking photographs.

The importance of studying contact sheets

Henri Cartier-Bresson looking at contacts at the New York Magnum Office. 1959. © Rene Burri / Magnum Photos

I have written about contact sheets several times before. For those of you who aren’t familiar with what a contact sheet is it is pretty much a sheet of paper which shows all the photographs a photographer shot on a roll of film. And with this sheet of paper, a photographer can use a loupe (small magnifying glass for the eye) and edit (choose) their favorite images. This was done in the days of the darkroom, and when digital didn’t exist.

Now of course, we have “Lightroom” where we can identify all of our photos of a scene digitally. Instead of having to look at tiny thumbnails, we can now see all of our “almost” photos in full resolution.

Contact sheets are the best learning tools for a photographer. You can learn from contact sheets from other photographers, and also from your own contact sheets.

Henri Cartier-Bresson. SPAIN. 1933. Valencia. Note the two versions of the photo he was considering from. This was the best.

Henri Cartier-Bresson. SPAIN. 1933. Valencia. This image wasn’t as strong as the prior.

Analyzing contact sheets from the masters who came before us is the closest thing we have to reading their minds. We can see how they “worked the scene”– and how they took photos from different perspectives, decided when to hit the shutter, and how many photos they decided to take. Some photographers are able to “nail” their photos in just 5-6 shots, while other photographers will shoot a full roll of 36 photos in just one scene.

Realize that all these master photographers were shooting on film, where it actually cost something to photograph. Now that most of us shoot digitally, there is no excuse for us to not “work the scene” and take many different photos of the same scene.

To learn more about contact sheets, check out my article: “10 Things Street Photographers Can Learn From Magnum Contact Sheets” and also pick up a copy of “Magnum Contact Sheets” on Amazon. It will be the best $100 you will ever spend for your photographic education.

How to “work the scene”

Okay, so we’ve talked about the importance of “working the scene”– and how important it is to take multiple photos of a scene (not just one photo). So how do you exactly “work the scene”?

A few things to clarify:

1. Don’t only just take one photo

Contact sheet of Elliott Erwitt, “Bulldogs”, New York, 2000. © Elliott Erwitt / Magnum Photos

Once again, it is very tempting to only the one photograph when you see a good scene. When I started off in street photography, I would be deathly afraid of offending people or being “caught in the act” of photographing strangers.

However realize that to make a great photograph, you need to work the scene. You will never know when the “best” decisive moment will occur. In a scene, there are many different great potential “decisive moments”. You generally only know which is the best “decisive moment” afterwards in the editing phase.

“Bulldogs”, New York, 2000. © Elliott Erwitt / Magnum Photos

Even Henri Cartier Bresson once said: “Sometimes you have to milk the cow a lot to get a little bit of cheese.”

2. Don’t chimp

Alain Capeilleres, 1976. © Martine Franck / Magnum Photos.

Another practical tip to better “work the scene” is to not “chimp”. What is chimping you ask? Well, it is when you look at your LCD screen after you take a photograph. Why do they call that “chimping”? Well, apparently film photographers used to make fun of digital photographers by saying they looked like a bunch of “chimps” (or monkeys) when they would crowd around their LCD screens and show off the photos they just took.

Photo by Martine Franck, Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur region. Town of Le Brusc. Pool designed by Alain Capeilleres, 1976. © Martine Franck / Magnum Photos

So what is so bad about “chimping” anyways? I’ve written an article on why street photographers shouldn’t chimp– but to sum up, chimping kills your flow when you’re out shooting on the streets. Rather than checking your LCD screen several times while working a scene to check for exposure, framing, and what you captured– it is better to just take a lot of photos at different angles and moments and choose the best photos later.

3. Linger

Contact sheet of Richard Kalvar, “Piazza Della Rotonda”. Rome, Italy, 1980. © Richard Kalvar / Magnum Photos

“Lingering” is one of the most difficult things about “working the scene”. Lingering is to “overstay your welcome”. It is generally rude to “linger”. Lingering is like “loitering”– you hang around longer than you should, and people look down on it.

One of the most frequently asked questions I get in my workshops is, “How long should I ‘work a scene’ and linger before I know it’s time to leave, or I got the shot?”

Well, that is the big problem. We have no idea when we either “got the shot” or we’ve hung around “long enough”.

Personally, my philosophy is to be the houseguest that overstays his or her welcome. Did you ever have a friend who asked to stay at your place for a week but ends up staying a few months? Be that guy.

“Piazza Della Rotonda”. Rome, Italy, 1980. © Richard Kalvar / Magnum Photos

The reason I advocate for “overstaying your welcome” is because it is better to linger for a longer period of time because often your best shot will be the last shot. Looking at a lot of contact sheets, especially this image by Richard Kalvar, you see that his best image was at the very end (on his 37th frame, quite lucky). If he didn’t linger around and work the scene, he would’ve never gotten his iconic shot.

Furthermore in street photography, you will only see a great potential scene once in your life. You might see similar scenes, but you will never see the same exact scene with the same exact people, with that background, that light, and that configuration.

So don’t live with regrets, linger around longer than you should– and “overshoot” a scene.

A technique I learned from my friend Charlie Kirk is if you see a great potential scene, hang around and wait a bit longer before you go in and start taking photos. For example, if you see a cool looking guy smoking– linger around him and wait for him to take a puff– then jump in and take a few shots of him inhaling his cigarette.

Lingering is quite painful to do. It is awkward, makes you feel uncomfortable, and might make your subject feel uncomfortable.

One way I get over the awkwardness of lingering and “working the scene” is by pretending I am photographing something behind them and avoiding eye contact. Because I shoot with a 35mm lens, I don’t have to point my camera directly at my subject to get them in the frame.

Another technique is to smile and interact with my subject while photographing them. For example, if I see a good scene, I might start off by shooting candidly– then if my subject makes eye contact with me, I will also make eye contact, smile, keep shooting, and even start chatting with them (hey, you’re looking good!)

4. Look for gestures

Che contact sheet. © Rene Burri / Magnum Photos

When you are “working the scene”– don’t just put your camera to rapid fire mode and start shooting aimlessly. Rather, be very conscious about when you decide to click the shutter.

Che Guevara. © Rene Burri / Magnum Photos

Generally I make the decision to click the shutter when I see hand gestures. It can be a gesture of someone covering their face, holding their hands by their sides, or pointing in a certain direction.

Another great tip is to wait for eye contact. Try experimenting taking photos without eye contact, and some photos with eye contact. You never know which photograph will be better. But there is a saying: “eyes are the windows to the soul”– which means if you get eye contact in your street photographs, they can be more intimate and emotional.

5. Keep your feet moving

If you ever watch a boxer, they rarely keep their feet still. The most important thing as a boxer is to never put your heels on the ground. The moment you stop moving is the moment you become a sitting duck– and will be a prime target to be knocked out by your opponent.

Take the same mindset as a street photographer. When working the scene, don’t just keep your feet planted on the ground. Keep your feet moving. Take photos from the left, right, take a step forward, a step backwards. Crouch down. Get different angles and perspectives.

6. Shoot both landscape and portrait photos

Contac sheet, VJ Day. Photo by Alfred Eisenstaedt

Also when working the scene, try experimenting taking your photos in both landscape (horizontal) and portrait (vertical) modes. When you are in the heat of the moment and see a great street photography scene, it is often difficult to know which is the “better” orientation of your camera for the scene.

So if you have time, try to work out both orientations of your camera– depending on what kind of image you want to create.

7. Be calm and patient

Jean Gaumy, Iran, 1986.

When you are working a scene, remember to try to stay calm and patient. We can sometimes get into a frenzy when working the scene, and trying to get “the shot”. However be calm and patient while you’re shooting– by analyzing when you need to hit the shutter, how close you need to be to your subject to frame them properly, and distracting elements in the background.

Jean Gaumy, Iran, 1986.

When you start off working the scene as a beginner, you might get too much of an adrenaline rush to stay calm and patient when shooting. But realize that with practice be time, you will be more calm and patient when working the scene– which will help you make better rational choices while shooting, and ultimately help you make better images.

8. Focus on the background

Martin Parr contact sheet from “The Last Resort“

When we are shooting on the streets, we can often focus too much on the subject and not enough on the background.

My advice is once you’ve established who your primary subject (or subjects) are– focus your eyes on the background. Try to get a clean background that doesn’t district– and adds to the scene.

The Last Resort, Photo by Martin Parr

Try to avoid getting random heads, poles, trees, or cars in the background. When you are working the scene, move your feet to get a cleaner background. Messy backgrounds are one of the biggest killers of great potential street photographs.

Conclusion

Contact Sheet by Martin Parr from Spain, 1997

To increase your odds of getting “keepers” in street photography, try practicing “working the scene” and lingering longer than necessary. Don’t keep your feet still, always be moving. But at the same time be patient.

Photo by Martin Parr from his “Common Sense” book. Spain, 1997

Also know that by working the scene longer than you need to, it will be strange and awkward. But with time, patience, practice, and a smile– you will be able to overcome this.

Learn more

To learn more, I recommend picking up a copy of “Magnum contact sheets” or reading the in-depth article I wrote on it: “10 Things Street Photographers Can Learn From Magnum Contact Sheets“. Also make sure to check out the “Contact Sheets” section at the Iconic Photos Blog.

If you want to build your confidence in street photography and learn to better “work the scene”– join me at one of my upcoming street photography workshops!

__

LEGAL INFORMATION: ALL THE PHOTOGRAPHS ARE DISPLAYED WITHOUT THE INTENTION OF FINANCIAL GAIN, AS SCIENTIFIC, LITERARY AND/OR ARTISTIC CRITICISM AND/OR RESEARCH, UNDER THE TERMS OF THE CURRENT LEGISLATION CONTAINED IN INTERNATIONAL TREATIES REGARDING COPYRIGHT.

Eric Kim (USA). Lives and works as a photographer in Berkeley, California. His main interest is street photography, to which he has devoted his artistic and educational work. He graduated in sociology from UCLA. Kim gives workshops in several parts of the world, including Canada, Holland, Vietnam, Japan and Australia, and has collaborated in a number of projects with Leica and Samsung. Hs work has been exhibited in Los Angeles and in Leica stores in Singapore, Seoul and Melbourne. and can be seen at: erickimphotography.com

Eric Kim (USA). Lives and works as a photographer in Berkeley, California. His main interest is street photography, to which he has devoted his artistic and educational work. He graduated in sociology from UCLA. Kim gives workshops in several parts of the world, including Canada, Holland, Vietnam, Japan and Australia, and has collaborated in a number of projects with Leica and Samsung. Hs work has been exhibited in Los Angeles and in Leica stores in Singapore, Seoul and Melbourne. and can be seen at: erickimphotography.com