Felipe Mejías López

Penitents of the brotherhood of Sorrows, posing with the image of the Virgin during the Easter Week in Aspe (Spain).

March 1929. (Photographer unknown. About photograhy Felipe Mejías, March 2015).

Paper memories. Photographs will always be paper memories, despite the fact that the emergence of digital technology in the world of images has changed the way they are stored. In any case, whether they are stuck in an album, crammed into an old biscuit tin, or stored in a virtual folder tucked away in the darkest corner of our computer’s hard drive, the construction of our memories owes a great deal to these images in black and white or faded colors. We can often reconstruct the exact layout of a place we have been, or feel the gaze of a friend or family member we no longer see because we can re-encounter them when we contemplate these square cardboard remnants. Memory cards and smart phones belong to a different visual universe that has no history but is a slave to the future, subject to a dictatorship that imposes the objective of immediacy and the compulsive desire to devour the overwhelming reality that surrounds us as if it might suddenly and permanently disappear from one moment to the next.

Photographs take us back to what we once were, in a constant, palpable, evident graphic salvation that is fed by our gaze like a fossil into which we breathe life simply by contemplating it. Looking at photos makes us grow, whether or not we want to, because we end up recognizing ourselves in them, somehow transformed into strangers we find it increasingly difficult to recognize: yet, there we are, participating like enthusiastic actors or perhaps behind the viewfinder snapping a photo. This tangible, visual certainty, together with the awareness that time has passed because we remember, creates an incredibly strong sensory cement that binds and gives meaning to our life stories.

But if we broaden the focus and think about our innumerable private –and therefore secret– photographs as a whole that have been collected since the beginning of photography, scattered throughout our immediate environment (not only in our family or neighborhood, but also throughout the macro scale of the city or region where we live), then these images evolve from more than a repertoire of personal memories to cultural objects. And as such, because of the historical, anthropological and ethnological information they contain, these photographs become unique, inimitable objects that deserve to be compiled, studied and published, in the same way we would share material found at an archeological dig or written documents from an historical archive.

Finally, those of us who work with this type of image consider it an act of social justice to return them to the community that produced them, that truly owns them. However, we return something that has been enriched by the hierarchy newly acquired through the transformation of these images into an object of knowledge and study, a sort of cultural heritage, so to speak. Thus these images become the graphic and sentimental memory of a collective whose cohesion is reinforced by their existence.

Initiatives of this type exist everywhere, although they do not always manage to develop the full potential stored within old photographs. The formation of multidisciplinary work teams that include historians and ethnographers familiar with local intra-history could be the key to successfully publishing work that would otherwise be converted into mere catalogs of orphaned images, macabre galleries exhibiting, as if embalmed, anonymous, unknown, dead people. Mere fetishes.

A small example of a local publication using old photographs as axial argument, which we think has achieved satisfactory results, is the project titled Recovered Memories. Photography and Society in Aspe 1870-1976. Field work begun in 1996 and still ongoing, has discovered and documented almost 4,000 images that have been recovered and selected from the private photographic repertoire generated by a small, southeastern Spanish urban community for over a century. The photographs have been classified into 24 different thematic categories that do not lost sight of the transversality of the contents that emerge from the photographs, which are teeming with sociological, anthropological and historical information.

Nazarenes, carrying the cross on their shoulders during the morning procession on Good Friday in Aspe (Spain).

(Photographer unknown, around 1955/Felipe Mejías, March 2015).

From an historian or archeologist’s point of view, it would have been unforgiveable not to try to find new ways to learn about the past with such valuable resources at hand. This is the point where rephotography begins.

It comes as no surprise to find that there are already masters of this relatively young discipline. However, there are only two things you can do with the work of Mark Klett and Camilo José Vergara watch and learn. Sergey Larenkov, Ricard Martínez, Hebe Robinson, Irina Werning, Gustavo Germano and Douglas Levere also produce work that comes very close to visual poetry. Many of them also enter the realm of social and political denunciation, making it quite clear that rephotography is not only a form of technical and aesthetic entertainment, but also a tool that helps us stop and reflect on the collateral damage associated with the passage of time.

But why rephotography? For someone who constantly thinks about the consequences and meaning of the passage of time, it is particularly gratifying to intervene in the process of creating an unattainable fiction through photography: blending the past and the present into a unique instant, taking on the role of a mischievous god in the age-old quest for immortality. Cernuda used to say: “[...] times are identical / gazes are different [...],” and something of this inspiration lurks beneath the ultimate goal of rephotography, attempting to stop and mix time, perceiving it without its having passed, or rather, perceiving if as if it had not done so. Making time manageable, cyclical and malleable is an heroic, almost obsessive exercise that goes beyond the purely visual mannerist trompe-l’oeil to reveal a little of the artifice behind the deception. The point is to photograph what other eyes before ours saw, in the same place, in the same instant, using the same technique. It is as if we brought the original photographer back to life and had him beside us, whispering the correct focus into our ear. Furthermore, if we do it in the place where we were born and raised, we can sublimate the nostalgic component each rephotograph inevitably contains: being right now where someone was long before us and seeing, touching and smelling the same environment. Feeling the same as that person. Being that person.

Overlapping, contrasting, recreating through transparencies and seeing how the different layers of memory deposited over the years, flourish and contribute to the task of creating the illusion that the old and new images are actually different sides of the same reality. A new discourse about the obvious contrast between the past and present, what is and what is not, is created, runs the risk of getting stuck at the anecdotal level. Even so, it may be enough. Although it is possible to try something else: building an imaginary cage in which to enclose two similar instances separated by time in the hope that they can live together and perhaps end up becoming a single moment. Just like in the Frankenstein myth, we give birth to impossible, two-headed monsters, Siamese twins that must always share different moments of the same existence. We give them a voice, and the possibility of shouting and discovering what is hidden within; their wrinkles, how the space or person has aged; what remains of what they once were. The experiment is not always successful, but it sometimes works and eventually creates a new scene where everything fits together marvelously; shapes continue and intertwine without signaling eras; grays and colors merge into a single light. It is a small miracle fixed in a subtle, crystalline, almost imperceptible balance.

But let us not deceive ourselves. In reality everything is always the past. The unattainable past. We like to think that rephotography gives us the possibility of returning to the past, to rethink it and try to bring it back to life. Poor fools, as if we could bring it back to a time and place it actually never left.

Felipe Mejías López (Spain, 1968). Lives and works in Spain. Historian and archaeologist. BA in Geography and History with a major in Art History from the University of Valencia. MA in Professional Archaeology and Heritage Management from the University of Alicante. A lot of his publications revolve around the archaeological, historical, artistic, documentary and photographic heritage of his native town, Aspe. Currently, he is editing the third volume of his research project on ancient photography and social history Recovered Memories. For this project, he studied the field of rephotography.

Felipe Mejías López (Spain, 1968). Lives and works in Spain. Historian and archaeologist. BA in Geography and History with a major in Art History from the University of Valencia. MA in Professional Archaeology and Heritage Management from the University of Alicante. A lot of his publications revolve around the archaeological, historical, artistic, documentary and photographic heritage of his native town, Aspe. Currently, he is editing the third volume of his research project on ancient photography and social history Recovered Memories. For this project, he studied the field of rephotography.

Penitents of the brotherhood of Sorrows, posing with the image of the Virgin during the Easter Week in Aspe (Spain).

March 1929. (Photographer unknown. About photograhy Felipe Mejías, March 2015).

Paper memories. Photographs will always be paper memories, despite the fact that the emergence of digital technology in the world of images has changed the way they are stored. In any case, whether they are stuck in an album, crammed into an old biscuit tin, or stored in a virtual folder tucked away in the darkest corner of our computer’s hard drive, the construction of our memories owes a great deal to these images in black and white or faded colors. We can often reconstruct the exact layout of a place we have been, or feel the gaze of a friend or family member we no longer see because we can re-encounter them when we contemplate these square cardboard remnants. Memory cards and smart phones belong to a different visual universe that has no history but is a slave to the future, subject to a dictatorship that imposes the objective of immediacy and the compulsive desire to devour the overwhelming reality that surrounds us as if it might suddenly and permanently disappear from one moment to the next.

Photographs take us back to what we once were, in a constant, palpable, evident graphic salvation that is fed by our gaze like a fossil into which we breathe life simply by contemplating it. Looking at photos makes us grow, whether or not we want to, because we end up recognizing ourselves in them, somehow transformed into strangers we find it increasingly difficult to recognize: yet, there we are, participating like enthusiastic actors or perhaps behind the viewfinder snapping a photo. This tangible, visual certainty, together with the awareness that time has passed because we remember, creates an incredibly strong sensory cement that binds and gives meaning to our life stories.

But if we broaden the focus and think about our innumerable private –and therefore secret– photographs as a whole that have been collected since the beginning of photography, scattered throughout our immediate environment (not only in our family or neighborhood, but also throughout the macro scale of the city or region where we live), then these images evolve from more than a repertoire of personal memories to cultural objects. And as such, because of the historical, anthropological and ethnological information they contain, these photographs become unique, inimitable objects that deserve to be compiled, studied and published, in the same way we would share material found at an archeological dig or written documents from an historical archive.

Finally, those of us who work with this type of image consider it an act of social justice to return them to the community that produced them, that truly owns them. However, we return something that has been enriched by the hierarchy newly acquired through the transformation of these images into an object of knowledge and study, a sort of cultural heritage, so to speak. Thus these images become the graphic and sentimental memory of a collective whose cohesion is reinforced by their existence.

Initiatives of this type exist everywhere, although they do not always manage to develop the full potential stored within old photographs. The formation of multidisciplinary work teams that include historians and ethnographers familiar with local intra-history could be the key to successfully publishing work that would otherwise be converted into mere catalogs of orphaned images, macabre galleries exhibiting, as if embalmed, anonymous, unknown, dead people. Mere fetishes.

A small example of a local publication using old photographs as axial argument, which we think has achieved satisfactory results, is the project titled Recovered Memories. Photography and Society in Aspe 1870-1976. Field work begun in 1996 and still ongoing, has discovered and documented almost 4,000 images that have been recovered and selected from the private photographic repertoire generated by a small, southeastern Spanish urban community for over a century. The photographs have been classified into 24 different thematic categories that do not lost sight of the transversality of the contents that emerge from the photographs, which are teeming with sociological, anthropological and historical information.

Nazarenes, carrying the cross on their shoulders during the morning procession on Good Friday in Aspe (Spain).

(Photographer unknown, around 1955/Felipe Mejías, March 2015).

From an historian or archeologist’s point of view, it would have been unforgiveable not to try to find new ways to learn about the past with such valuable resources at hand. This is the point where rephotography begins.

It comes as no surprise to find that there are already masters of this relatively young discipline. However, there are only two things you can do with the work of Mark Klett and Camilo José Vergara watch and learn. Sergey Larenkov, Ricard Martínez, Hebe Robinson, Irina Werning, Gustavo Germano and Douglas Levere also produce work that comes very close to visual poetry. Many of them also enter the realm of social and political denunciation, making it quite clear that rephotography is not only a form of technical and aesthetic entertainment, but also a tool that helps us stop and reflect on the collateral damage associated with the passage of time.

But why rephotography? For someone who constantly thinks about the consequences and meaning of the passage of time, it is particularly gratifying to intervene in the process of creating an unattainable fiction through photography: blending the past and the present into a unique instant, taking on the role of a mischievous god in the age-old quest for immortality. Cernuda used to say: “[...] times are identical / gazes are different [...],” and something of this inspiration lurks beneath the ultimate goal of rephotography, attempting to stop and mix time, perceiving it without its having passed, or rather, perceiving if as if it had not done so. Making time manageable, cyclical and malleable is an heroic, almost obsessive exercise that goes beyond the purely visual mannerist trompe-l’oeil to reveal a little of the artifice behind the deception. The point is to photograph what other eyes before ours saw, in the same place, in the same instant, using the same technique. It is as if we brought the original photographer back to life and had him beside us, whispering the correct focus into our ear. Furthermore, if we do it in the place where we were born and raised, we can sublimate the nostalgic component each rephotograph inevitably contains: being right now where someone was long before us and seeing, touching and smelling the same environment. Feeling the same as that person. Being that person.

Overlapping, contrasting, recreating through transparencies and seeing how the different layers of memory deposited over the years, flourish and contribute to the task of creating the illusion that the old and new images are actually different sides of the same reality. A new discourse about the obvious contrast between the past and present, what is and what is not, is created, runs the risk of getting stuck at the anecdotal level. Even so, it may be enough. Although it is possible to try something else: building an imaginary cage in which to enclose two similar instances separated by time in the hope that they can live together and perhaps end up becoming a single moment. Just like in the Frankenstein myth, we give birth to impossible, two-headed monsters, Siamese twins that must always share different moments of the same existence. We give them a voice, and the possibility of shouting and discovering what is hidden within; their wrinkles, how the space or person has aged; what remains of what they once were. The experiment is not always successful, but it sometimes works and eventually creates a new scene where everything fits together marvelously; shapes continue and intertwine without signaling eras; grays and colors merge into a single light. It is a small miracle fixed in a subtle, crystalline, almost imperceptible balance.

But let us not deceive ourselves. In reality everything is always the past. The unattainable past. We like to think that rephotography gives us the possibility of returning to the past, to rethink it and try to bring it back to life. Poor fools, as if we could bring it back to a time and place it actually never left.

Felipe Mejías López (Spain, 1968). Lives and works in Spain. Historian and archaeologist. BA in Geography and History with a major in Art History from the University of Valencia. MA in Professional Archaeology and Heritage Management from the University of Alicante. A lot of his publications revolve around the archaeological, historical, artistic, documentary and photographic heritage of his native town, Aspe. Currently, he is editing the third volume of his research project on ancient photography and social history Recovered Memories. For this project, he studied the field of rephotography.

Felipe Mejías López (Spain, 1968). Lives and works in Spain. Historian and archaeologist. BA in Geography and History with a major in Art History from the University of Valencia. MA in Professional Archaeology and Heritage Management from the University of Alicante. A lot of his publications revolve around the archaeological, historical, artistic, documentary and photographic heritage of his native town, Aspe. Currently, he is editing the third volume of his research project on ancient photography and social history Recovered Memories. For this project, he studied the field of rephotography.Andrea Dorliguzzo

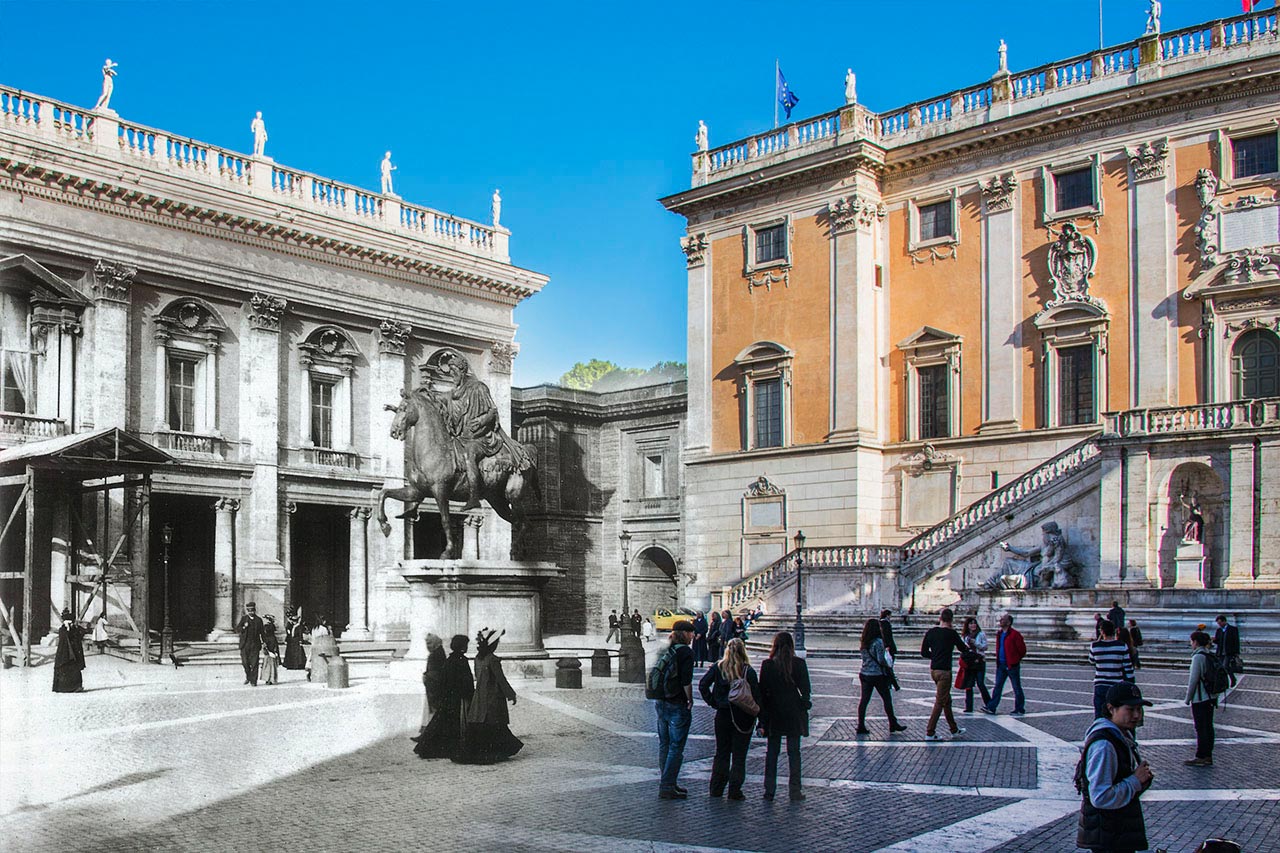

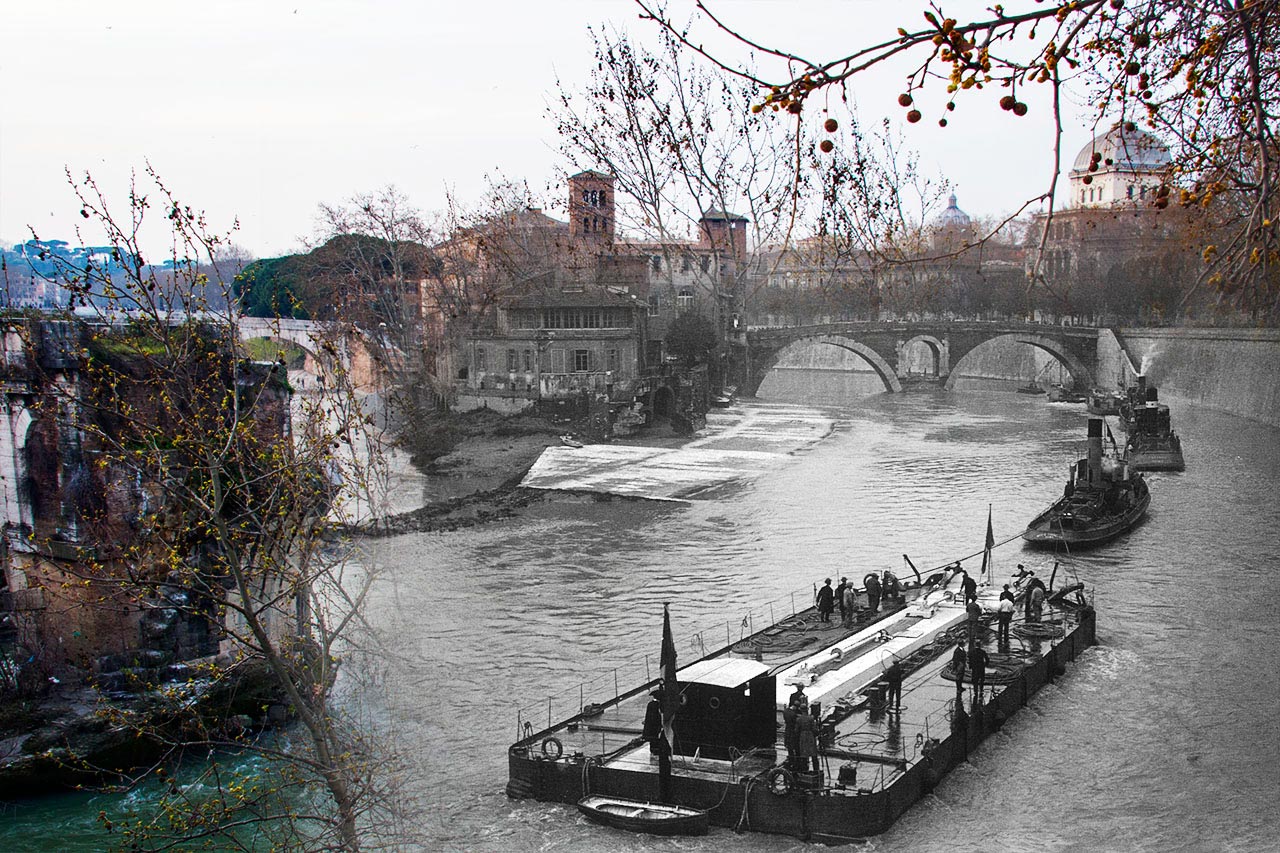

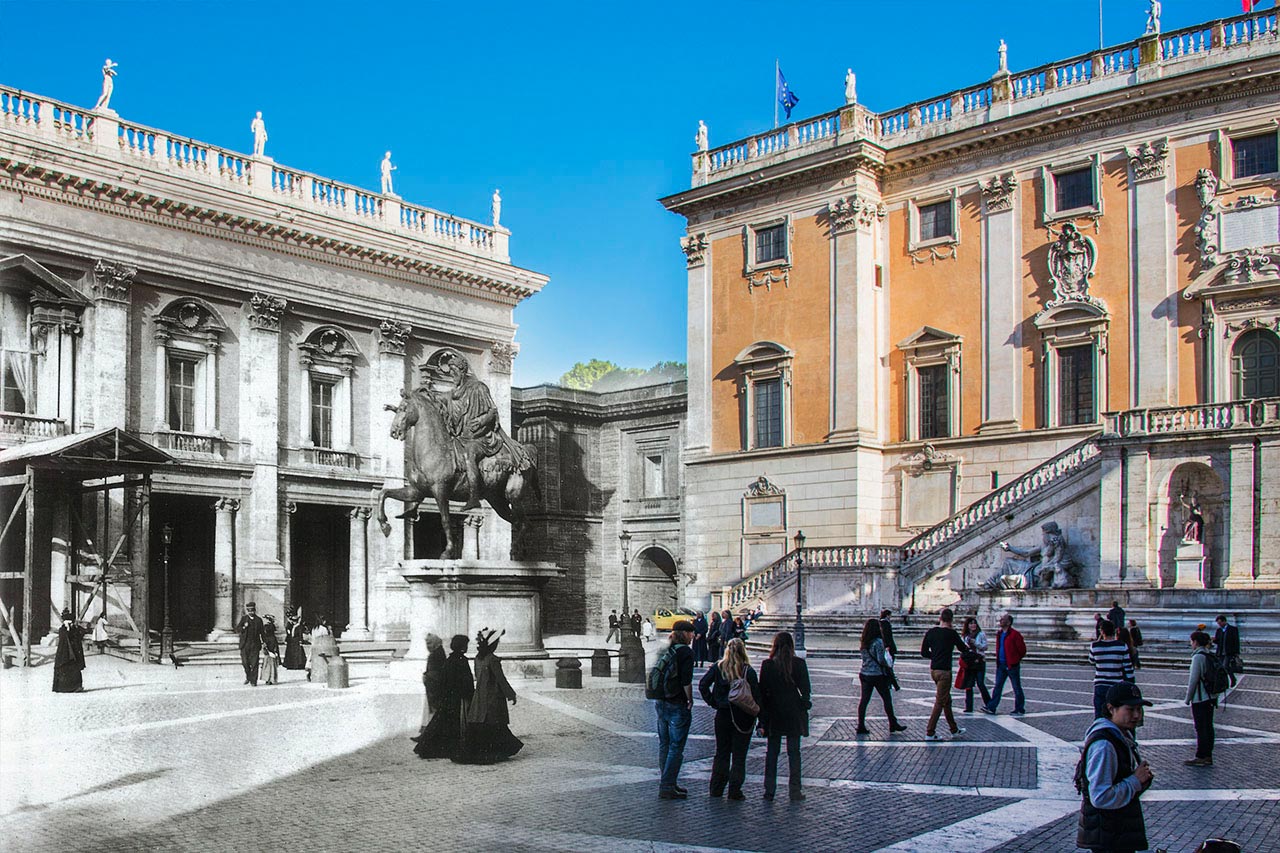

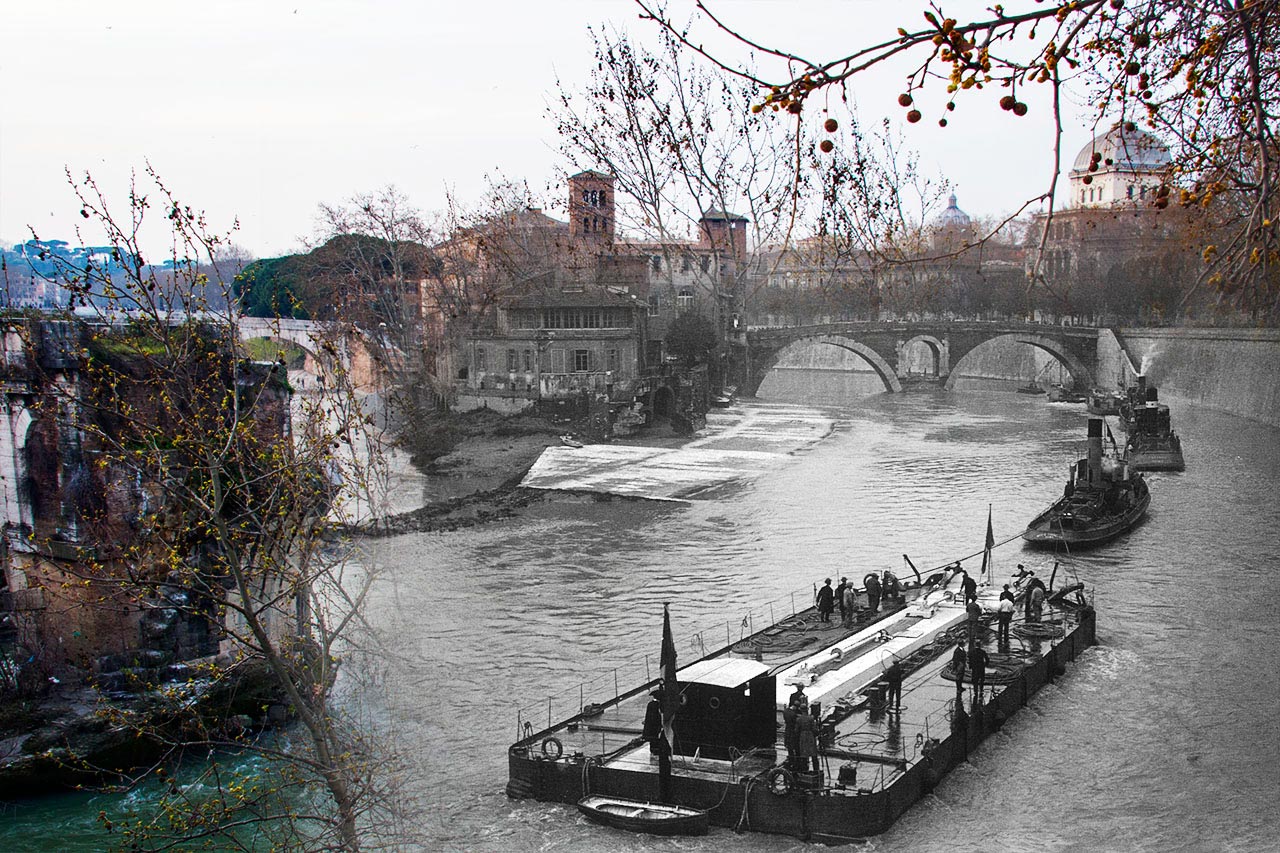

In 2013, Andrea Dorliguzzo started with his rephotography project Roma Ieri Oggi (Rome Yesterday Today). Driven by his passion for photography and his admiration for Rome, he started to collect old photographs of the city and combined these with contemporary ones, taken at exactly the same spot. In this way, the past and the present are brought together, causing a thrilling historical sensation which reminds us of all the great stories that the city has to tell.

Andrea Dorliguzzo (Italy) was born in Friuli, in the north-east part of Italy. A few years ago, he moved to Rome. His passion for photography was born quite recently. Over the last years, he had the luck of traveling a lot and bringing home an unimaginable number of pictures and memories. Regarding his photos, he is very critical and only a small selection is published on his photo blog.

Andrea Dorliguzzo (Italy) was born in Friuli, in the north-east part of Italy. A few years ago, he moved to Rome. His passion for photography was born quite recently. Over the last years, he had the luck of traveling a lot and bringing home an unimaginable number of pictures and memories. Regarding his photos, he is very critical and only a small selection is published on his photo blog.

In 2013, Andrea Dorliguzzo started with his rephotography project Roma Ieri Oggi (Rome Yesterday Today). Driven by his passion for photography and his admiration for Rome, he started to collect old photographs of the city and combined these with contemporary ones, taken at exactly the same spot. In this way, the past and the present are brought together, causing a thrilling historical sensation which reminds us of all the great stories that the city has to tell.

Andrea Dorliguzzo (Italy) was born in Friuli, in the north-east part of Italy. A few years ago, he moved to Rome. His passion for photography was born quite recently. Over the last years, he had the luck of traveling a lot and bringing home an unimaginable number of pictures and memories. Regarding his photos, he is very critical and only a small selection is published on his photo blog.

Andrea Dorliguzzo (Italy) was born in Friuli, in the north-east part of Italy. A few years ago, he moved to Rome. His passion for photography was born quite recently. Over the last years, he had the luck of traveling a lot and bringing home an unimaginable number of pictures and memories. Regarding his photos, he is very critical and only a small selection is published on his photo blog.