ZoneZero

Interview with Caspar Sonnen about interactive storytelling. February 2015

Caspar Sonnen. Studied New Media and Film at Utrecht University. He has worked for film and media art festivals. In 2003, he co-founded Seize the Night, an open air film festival in Amsterdam. In 2005, Sonnen became the new media coordinator for the International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam (IDFA). In 2008, he launched IDFA DocLab. The program quickly grew into an international platform for interactive webdocs and other new genres where digital technology and documentary storytelling converge.

Caspar Sonnen. Studied New Media and Film at Utrecht University. He has worked for film and media art festivals. In 2003, he co-founded Seize the Night, an open air film festival in Amsterdam. In 2005, Sonnen became the new media coordinator for the International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam (IDFA). In 2008, he launched IDFA DocLab. The program quickly grew into an international platform for interactive webdocs and other new genres where digital technology and documentary storytelling converge.Interview with Caspar Sonnen about interactive storytelling. February 2015

Caspar Sonnen. Studied New Media and Film at Utrecht University. He has worked for film and media art festivals. In 2003, he co-founded Seize the Night, an open air film festival in Amsterdam. In 2005, Sonnen became the new media coordinator for the International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam (IDFA). In 2008, he launched IDFA DocLab. The program quickly grew into an international platform for interactive webdocs and other new genres where digital technology and documentary storytelling converge.

Caspar Sonnen. Studied New Media and Film at Utrecht University. He has worked for film and media art festivals. In 2003, he co-founded Seize the Night, an open air film festival in Amsterdam. In 2005, Sonnen became the new media coordinator for the International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam (IDFA). In 2008, he launched IDFA DocLab. The program quickly grew into an international platform for interactive webdocs and other new genres where digital technology and documentary storytelling converge.Mónica Sánchez Escuer

Time is creation, argued Henri Bergson: “The more we explore the nature of time, the more we will understand how duration means invention, creation of forms and continuous production of the absolutely new.” (2007, p. 30).

Only insofar as time is perceived and received does it exist and acquire meaning for man. Photography and literature are two artistic media through which humanity has recreated duration and development. Both disciplines encapsulate instants: literature, a sequence of them, and photography a single instant that reveals or implies a before and an after. They capture time to show a legible fragment of its movement. Regardless of whether what they depict and relate is real or fiction, a text or a photograph bears the traces of the passage of time.

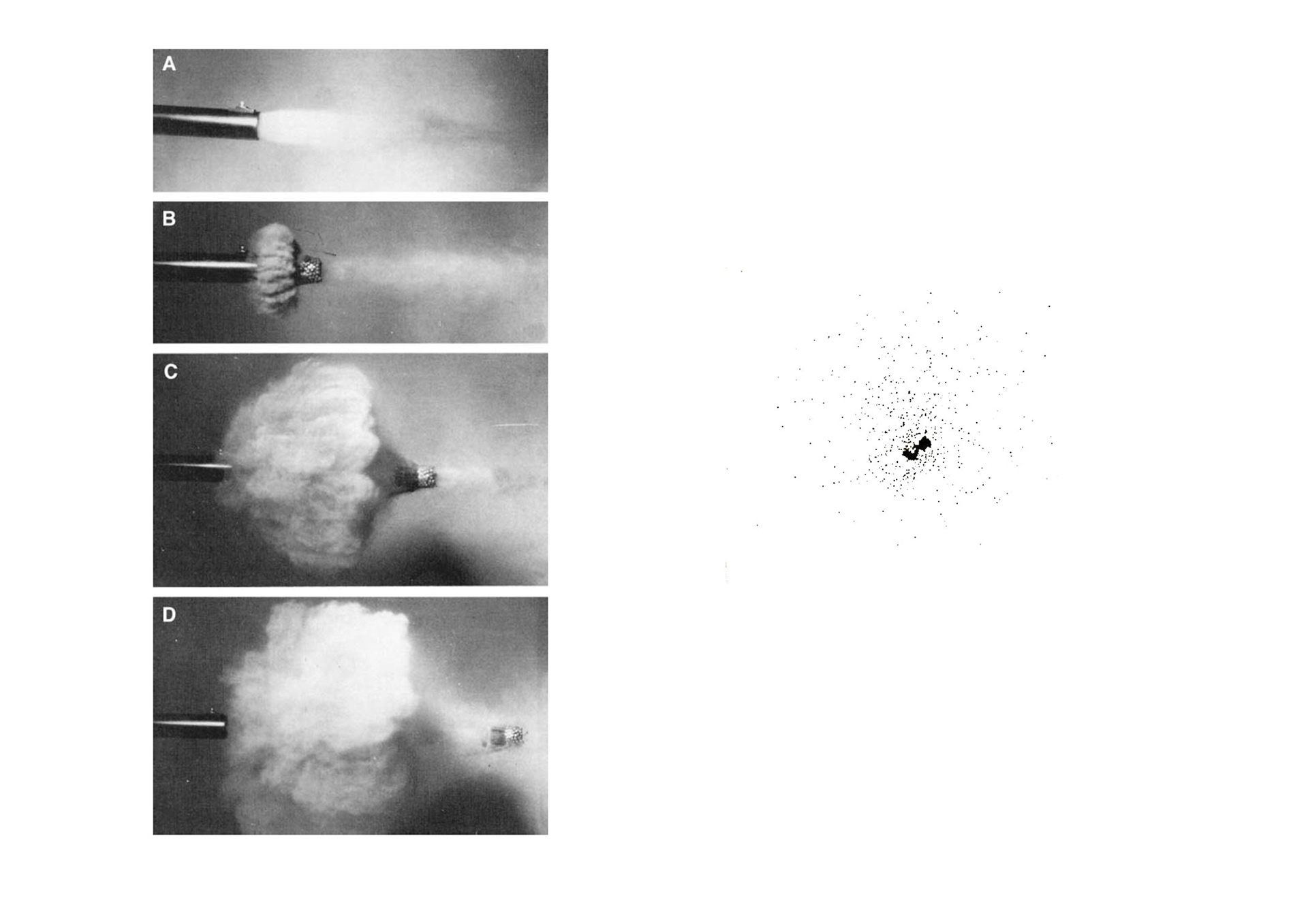

The two languages represent this passage through various forms and processes, based on the position, movement and speed of the observer-narrator, which can broadly be summarized in three moments: 1] stopped time: a literary vignette or frozen image of a scene in which the objects and/or characters are time frames depicting something that happened or is about to happen; 2] the visual tour from a fixed point: images or texts that draw the gaze or reading towards the various focal points of a panoramic photo or a written narrative, generally in the present, in which the narrator reveals to the reader the space-time in which the action takes place through descriptions; and 3] movement: where the actions of the story comprised in an objective period of time, including the stream of consciousness, are visually narrated and represented.

The reality described or depicted in photography and literature is not only an interpretation of the facts but also of their duration and the continuous movement of the story and the events contained in it. In both disciplines, time is a reference, structure and metaphor. It is a fundamental part of the framework of both media, and is also represented and reconfigured as an image of the expression of literary and photographic discourses. It cannot be explained or demonstrated: “The artist who works with photography or stories does not provide solutions, but rather answers people's questions with another question, a more refined, aesthetic one: a doubt answered with a metaphor.” (López Aguilar, 2002).

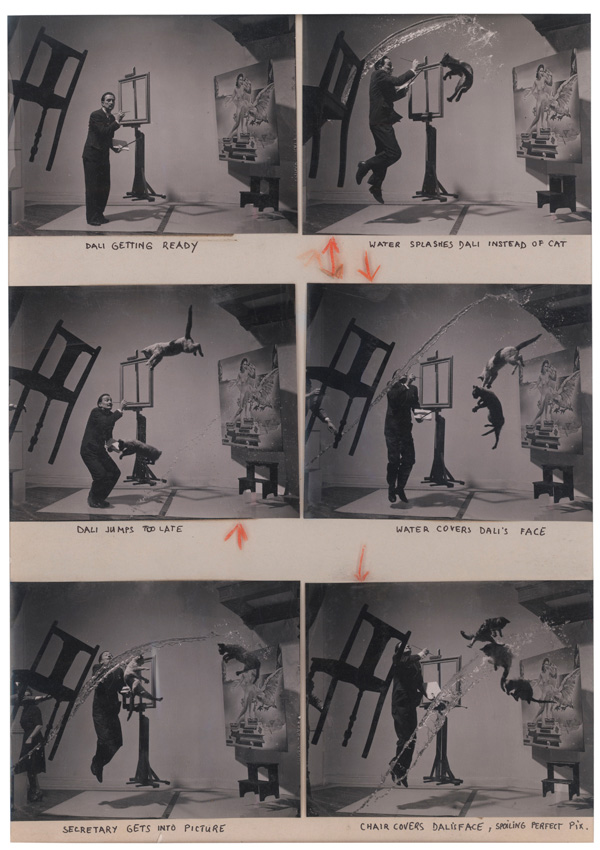

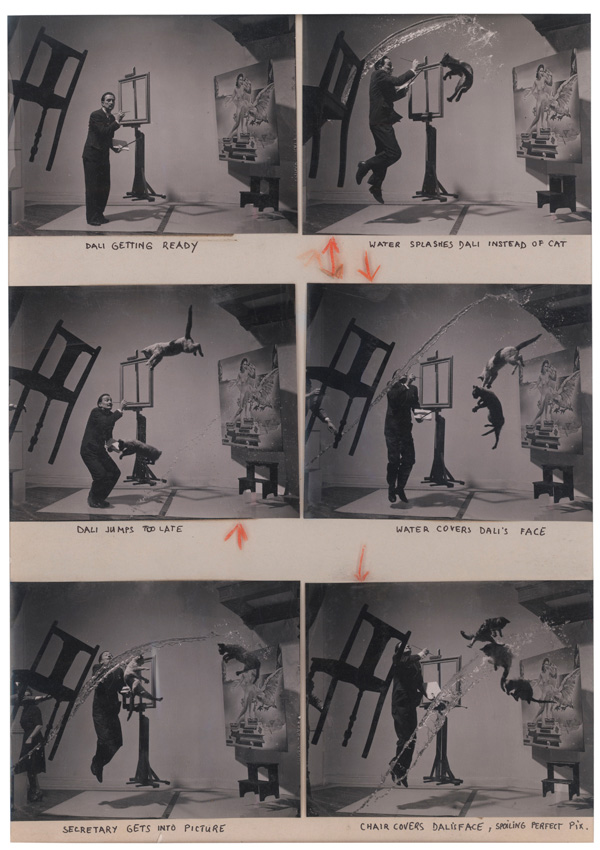

Salvador Dali, 1948. Phillipe Halsman/Magnum Photos

The narrative construction of time in the image

In photography, the artist chooses the setting, frame and significant object inside the visual narrative he or she wishes to convey. When actions or movement are directly involved, he or she chooses and captures the "decisive moment" in which the Barthesian punctum is unveiled, the point at which all the elements, signs and marks that lend meaning to the image are incorporated.

Photographic discourse, like many artistic languages, has a double spatiality and temporality: on the one hand, it constitutes a two-dimensional space [s1] that represents an illusory, three-dimensional space [s2]. On the other hand, there is the time of representation [t1] – that is, the real time when the photograph was taken –, and the time represented in the image [t2].

Time in a photograph is constructed by linking various elements that can be observed on different levels. These elements include rhythm, tension, sequentiality, the representation of duration and references to the definition of space.

The space and time of representation are fundamental elements of photographic composition: on the one hand perspective, depth of field, interplay of plans, balance, proportion, visual tour, iconic order, tension and rhythm; and on the other instantaneity, longevity, sequentiality, symbolic and subjective times and narrative. Perspective and various planes create perceptual gradients that construct the three-dimensional space and movement in the images. The rhythm is observed through the repetition of elements and the way they are organized in the composition. Saturation, empty spaces and the distribution of tones determine the pace of a photograph. Tension is created by various elements: the lines that express movement, the contrast between regular geometric shapes, the sweeps, angles, perspective, chromatic contrast, lighting and textures of the image. The visual weight of each of the elements, determined by their size and position in the different planes of the photographs, can provide a spatial-temporal hierarchy, whereby more important elements in the foreground are equivalent to the present in the narration of the image. The point of view is expressed through the field of vision, the angle from which the photograph is taken, and the selection of objects shown with clarity and closeness, or that remain in the middle ground or background. The photograph suggests a visual tour, a dynamic order of interpretation established by the composition that can indicate a timeline.

At a technical level, the time dimension is produced by the shutter speed. If the photographer wishes to project an instant, to freeze time, he or she will use a fast speed to capture a scene in a fraction of a second, which in literature would be depicted in a vignette. If, alternately, he or she wishes to depict duration, a low speed allows a long exposure times that create effects in the image, such as the sweep in a moving subject. The presence of certain elements such as clocks, calendars, old objects and even photographs are indicators of time that lead the viewer to interpret the image as duration or sequentiality. Some photographers prefer to convey the opposite, a timeless situation, and to do so deliberately conceal any mark that might indicate the historical time or moment when the photograph was taken. Erasing the traces of time is a discursive effect that has been used since classical representation and “is intended to strengthen the illusion of reality (Marzal Felici, 2011, p. 215).

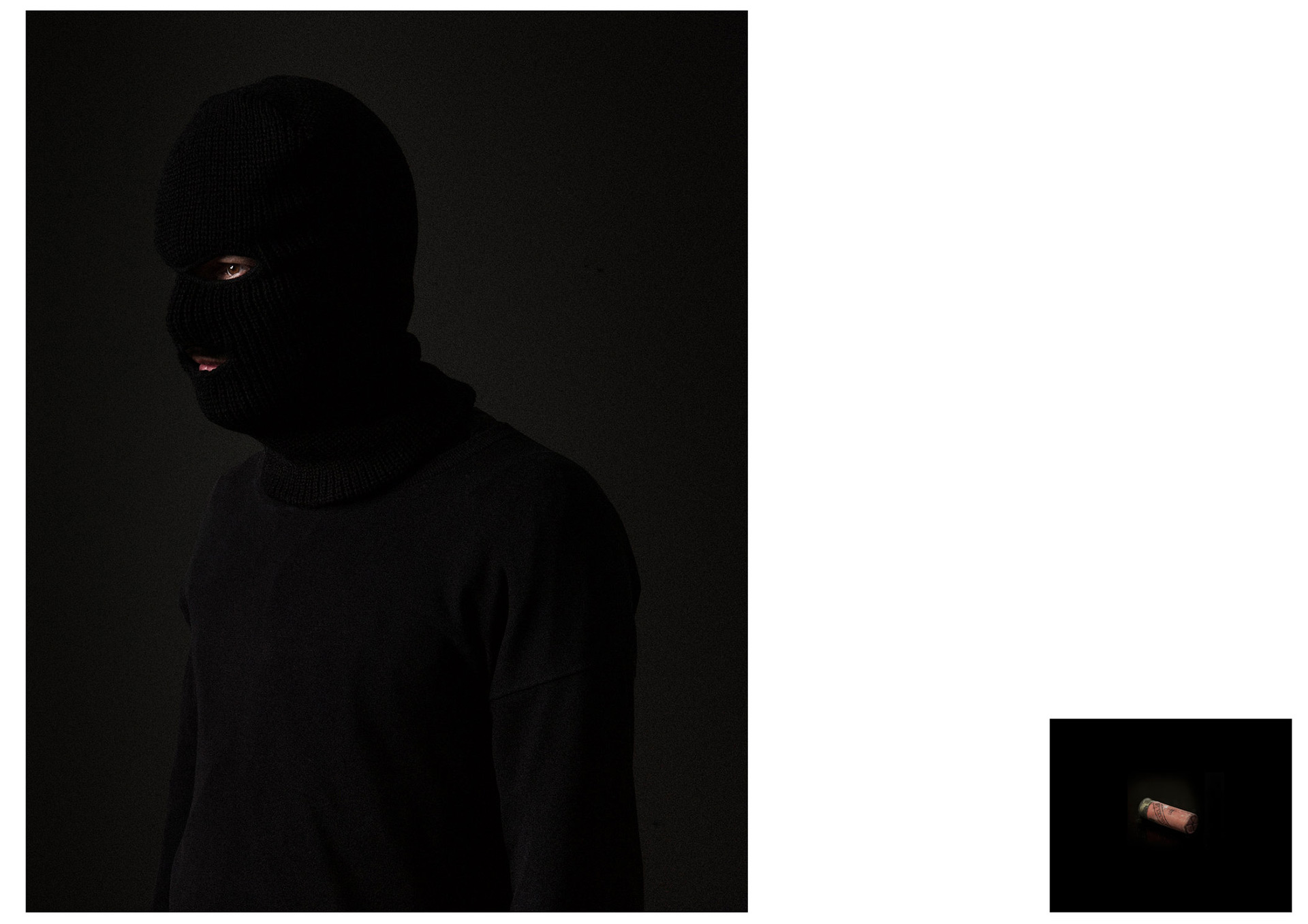

However, an image can express much more than a fragment of reality. It can be a metaphor in itself, and its content may be symbolic, as will also be the time within it. In the case of abstract photographs, for example, in which spatio-temporal marks are concealed, their discourse is closer to poetry, with a necessarily individual interpretation. The perception of time and space within them is subjective. The Barthesian punctum relates to the presence of a subjective time, the element that bursts into the time flow of interpreting the image. It moves or affects the viewer at a very personal level, based on their previous experience.

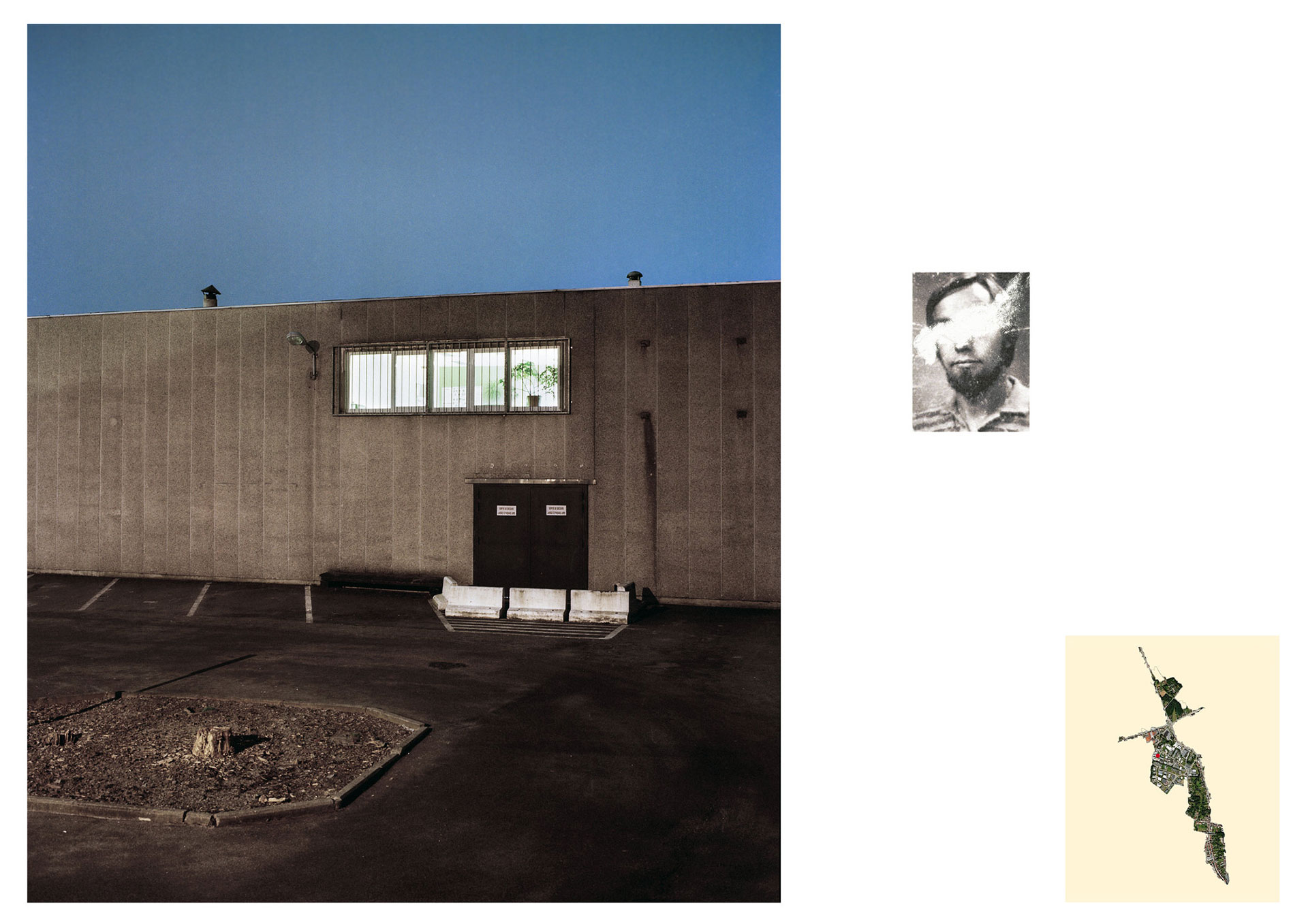

Another aspect in which the time characteristics of a photograph can be analyzed is sequentiality1, both in its elements within a single image, [such as its order and layout], and in the succession of photographs in polyptychs depicting a sequential scene. The illustrative dimension of the image comprises the central elements of narrative: point of view, characters, authenticity, textual marks and enunciation.

The narrative of the image is constructed by the morphological, compositional and illustrative elements, which together convey a specific overall temporal effect. The point of view from which a story is narrated is crucial and, in photography, can be clearly observed in the framing, the position of the photographer and the angle from which it is taken [the result of selecting a determined space and time]. The framing evokes the artist’s way of looking and choosing which part of the world is worth stopping, closely observing and relating.

The characters in a photograph can say a great deal about the scene depicted: their emotions, feelings, attitudes and expectations, reflected in their posture, gestures and gaze, tell stories and show how they react to their surroundings. Authenticity and its opposite, artificiality [not to be confused with fictionality] in photography is constructed using certain effects, staging or filters or nothing at all, if the intention is to be faithful to the real scene, in accordance with the photographer’s narrative intention. If the aim is to create alienation, fracture or a concept in the viewer, they will distance the image from the parameters of reality by seeking to redefine its constituent elements. The textual marks reveal the presence of the enunciator in the image. These can be indicative, iconic, symbolic or referential marks. They include the internal organization of their elements, the tension between the geometric lines and figures, and the focus of attention. As Santos Zunzunegui wrote, quoted by Marzal2: “the presence of the viewer can be reconstructed and is therefore visible” (2011, p. 221), through two discursive activities: aspectualization [identifying a group of spatio-temporal aspectual categories that reveal the presence of the viewer; and focalization [how the photographic intent expresses itself].

Marzal identifies two strategies in photographic enunciation: on the one hand, the one applied in the realistic representation of discourse, a metonymic strategy in terms of language, in which the photographic discourse remains contiguous to the model; and on the other, the strategy that seeks a non-realistic, metaphorical representation, with an imaginary or symbolical relationship with the model. The caption often provides this information since without it, incorrect if at times interesting interpretations might emerge.

However, time may not only be observed in the content of the photograph, such as its objects and setting, but also be defined in each of the substantial stages of the photographic act, and may be explained by transferring the terms that Ricoeur (1995) uses for the textual narrative to the narrative of the image. 1. Prefiguration, a deeper exploration of the contextual level of analysis proposed by Marzal, refers to the circumstances and conditions in which the photograph is taken, the specific space, historical moment, technological development of the era and the author’s biography, among others. 2. Configuration is the process of producing the image using all the creative and technical elements that correspond to the morphological, compositional and illustrative levels. 3. Refiguration involves the viewers’ interpretation of the image, in other words, illustration and its reception. The process of narrating and interpreting time in the images takes place during these three moments of the photographic act.

However, when arranging the photographic piece or series, it is important that the different times be distinguished, since each one follows specific narrative strategies: 1. Objective time, defined by the precise moment at which the photograph was taken, is the referential time that is narrated on the basis of the textual marks in the image. 2 Represented time, shown in the photograph by the time frames that the photographer decides to include, is equivalent to the time of the story. 3. Symbolic time, when the image suggests a different reality to that represented, is constructed by creating ambiguity in meaning, or by recurring to visual rhetorical figures [such as metonymy, synechdoque and personification] or by the deliberate concealing of time frames. 4. Lastly, subjective time is determined by the point of view that the author applies to the image, but also by the context and interpretation of the viewer during the reconfiguration process. The latter two can be clearly seen in photographs created with artistic rather than documentary intentions, whose few referential elements make the images appear suspended in non-time. These photographs play with the viewer’s perception in order to elicit sensations, aesthetic emotions, uncertainty, or enable the latter to interpret and define its symbolic content and spatial-temporality.

1 Marzal Felice links sequentiality to narrative. However, here they are regarded as two separate processes as a broader concept of narrative is taken than the mere succession of events.

2 Much of the methodology proposed by Marzal is extracted from Santos Zunzunegui’s analysis in Paisajes de la forma. Ejercicios de análisis de la imagen. Cátedra, Madrid, 1988

Bibliografía

López Aguilar, E. (octubre de 2002). Julio Cortázar y la fotografía. La jornada semanal (397).

Bergson, H. (2007). La evolución creadora. Buenos Aires: Cactus.

Marzal Felici, J. (2011). Cómo se lee una fotografía. Madrid: Cátedra.

Ricoeur, P. (1995). Tiempo y narración (Vol. II). México: Siglo XXI.

Mónica Sánchez Ezcuer. Lives and works in Mexico. Writer and literature professor. Sociologist at the UNAM with a master in Literary Creation from the University of Texas. Currently she studies the master Visual Arts at San Carlos (UNAM). She collaborates in multidisciplinary projects; she has worked with musicians, painters and photographers in realizing operas, publications, concerts and exhibitions. She is especially interested in the relation between photography and narrative. She has given courses and workshops in literature and narrative in various institutions, like the UNAM, the University of Texas, Casa Lamm and the Foundation Pedro Meyer.

Mónica Sánchez Ezcuer. Lives and works in Mexico. Writer and literature professor. Sociologist at the UNAM with a master in Literary Creation from the University of Texas. Currently she studies the master Visual Arts at San Carlos (UNAM). She collaborates in multidisciplinary projects; she has worked with musicians, painters and photographers in realizing operas, publications, concerts and exhibitions. She is especially interested in the relation between photography and narrative. She has given courses and workshops in literature and narrative in various institutions, like the UNAM, the University of Texas, Casa Lamm and the Foundation Pedro Meyer.Time is creation, argued Henri Bergson: “The more we explore the nature of time, the more we will understand how duration means invention, creation of forms and continuous production of the absolutely new.” (2007, p. 30).

Only insofar as time is perceived and received does it exist and acquire meaning for man. Photography and literature are two artistic media through which humanity has recreated duration and development. Both disciplines encapsulate instants: literature, a sequence of them, and photography a single instant that reveals or implies a before and an after. They capture time to show a legible fragment of its movement. Regardless of whether what they depict and relate is real or fiction, a text or a photograph bears the traces of the passage of time.

The two languages represent this passage through various forms and processes, based on the position, movement and speed of the observer-narrator, which can broadly be summarized in three moments: 1] stopped time: a literary vignette or frozen image of a scene in which the objects and/or characters are time frames depicting something that happened or is about to happen; 2] the visual tour from a fixed point: images or texts that draw the gaze or reading towards the various focal points of a panoramic photo or a written narrative, generally in the present, in which the narrator reveals to the reader the space-time in which the action takes place through descriptions; and 3] movement: where the actions of the story comprised in an objective period of time, including the stream of consciousness, are visually narrated and represented.

The reality described or depicted in photography and literature is not only an interpretation of the facts but also of their duration and the continuous movement of the story and the events contained in it. In both disciplines, time is a reference, structure and metaphor. It is a fundamental part of the framework of both media, and is also represented and reconfigured as an image of the expression of literary and photographic discourses. It cannot be explained or demonstrated: “The artist who works with photography or stories does not provide solutions, but rather answers people's questions with another question, a more refined, aesthetic one: a doubt answered with a metaphor.” (López Aguilar, 2002).

Salvador Dali, 1948. Phillipe Halsman/Magnum Photos

The narrative construction of time in the image

In photography, the artist chooses the setting, frame and significant object inside the visual narrative he or she wishes to convey. When actions or movement are directly involved, he or she chooses and captures the "decisive moment" in which the Barthesian punctum is unveiled, the point at which all the elements, signs and marks that lend meaning to the image are incorporated.

Photographic discourse, like many artistic languages, has a double spatiality and temporality: on the one hand, it constitutes a two-dimensional space [s1] that represents an illusory, three-dimensional space [s2]. On the other hand, there is the time of representation [t1] – that is, the real time when the photograph was taken –, and the time represented in the image [t2].

Time in a photograph is constructed by linking various elements that can be observed on different levels. These elements include rhythm, tension, sequentiality, the representation of duration and references to the definition of space.

The space and time of representation are fundamental elements of photographic composition: on the one hand perspective, depth of field, interplay of plans, balance, proportion, visual tour, iconic order, tension and rhythm; and on the other instantaneity, longevity, sequentiality, symbolic and subjective times and narrative. Perspective and various planes create perceptual gradients that construct the three-dimensional space and movement in the images. The rhythm is observed through the repetition of elements and the way they are organized in the composition. Saturation, empty spaces and the distribution of tones determine the pace of a photograph. Tension is created by various elements: the lines that express movement, the contrast between regular geometric shapes, the sweeps, angles, perspective, chromatic contrast, lighting and textures of the image. The visual weight of each of the elements, determined by their size and position in the different planes of the photographs, can provide a spatial-temporal hierarchy, whereby more important elements in the foreground are equivalent to the present in the narration of the image. The point of view is expressed through the field of vision, the angle from which the photograph is taken, and the selection of objects shown with clarity and closeness, or that remain in the middle ground or background. The photograph suggests a visual tour, a dynamic order of interpretation established by the composition that can indicate a timeline.

At a technical level, the time dimension is produced by the shutter speed. If the photographer wishes to project an instant, to freeze time, he or she will use a fast speed to capture a scene in a fraction of a second, which in literature would be depicted in a vignette. If, alternately, he or she wishes to depict duration, a low speed allows a long exposure times that create effects in the image, such as the sweep in a moving subject. The presence of certain elements such as clocks, calendars, old objects and even photographs are indicators of time that lead the viewer to interpret the image as duration or sequentiality. Some photographers prefer to convey the opposite, a timeless situation, and to do so deliberately conceal any mark that might indicate the historical time or moment when the photograph was taken. Erasing the traces of time is a discursive effect that has been used since classical representation and “is intended to strengthen the illusion of reality (Marzal Felici, 2011, p. 215).

However, an image can express much more than a fragment of reality. It can be a metaphor in itself, and its content may be symbolic, as will also be the time within it. In the case of abstract photographs, for example, in which spatio-temporal marks are concealed, their discourse is closer to poetry, with a necessarily individual interpretation. The perception of time and space within them is subjective. The Barthesian punctum relates to the presence of a subjective time, the element that bursts into the time flow of interpreting the image. It moves or affects the viewer at a very personal level, based on their previous experience.

Another aspect in which the time characteristics of a photograph can be analyzed is sequentiality1, both in its elements within a single image, [such as its order and layout], and in the succession of photographs in polyptychs depicting a sequential scene. The illustrative dimension of the image comprises the central elements of narrative: point of view, characters, authenticity, textual marks and enunciation.

The narrative of the image is constructed by the morphological, compositional and illustrative elements, which together convey a specific overall temporal effect. The point of view from which a story is narrated is crucial and, in photography, can be clearly observed in the framing, the position of the photographer and the angle from which it is taken [the result of selecting a determined space and time]. The framing evokes the artist’s way of looking and choosing which part of the world is worth stopping, closely observing and relating.

The characters in a photograph can say a great deal about the scene depicted: their emotions, feelings, attitudes and expectations, reflected in their posture, gestures and gaze, tell stories and show how they react to their surroundings. Authenticity and its opposite, artificiality [not to be confused with fictionality] in photography is constructed using certain effects, staging or filters or nothing at all, if the intention is to be faithful to the real scene, in accordance with the photographer’s narrative intention. If the aim is to create alienation, fracture or a concept in the viewer, they will distance the image from the parameters of reality by seeking to redefine its constituent elements. The textual marks reveal the presence of the enunciator in the image. These can be indicative, iconic, symbolic or referential marks. They include the internal organization of their elements, the tension between the geometric lines and figures, and the focus of attention. As Santos Zunzunegui wrote, quoted by Marzal2: “the presence of the viewer can be reconstructed and is therefore visible” (2011, p. 221), through two discursive activities: aspectualization [identifying a group of spatio-temporal aspectual categories that reveal the presence of the viewer; and focalization [how the photographic intent expresses itself].

Marzal identifies two strategies in photographic enunciation: on the one hand, the one applied in the realistic representation of discourse, a metonymic strategy in terms of language, in which the photographic discourse remains contiguous to the model; and on the other, the strategy that seeks a non-realistic, metaphorical representation, with an imaginary or symbolical relationship with the model. The caption often provides this information since without it, incorrect if at times interesting interpretations might emerge.

However, time may not only be observed in the content of the photograph, such as its objects and setting, but also be defined in each of the substantial stages of the photographic act, and may be explained by transferring the terms that Ricoeur (1995) uses for the textual narrative to the narrative of the image. 1. Prefiguration, a deeper exploration of the contextual level of analysis proposed by Marzal, refers to the circumstances and conditions in which the photograph is taken, the specific space, historical moment, technological development of the era and the author’s biography, among others. 2. Configuration is the process of producing the image using all the creative and technical elements that correspond to the morphological, compositional and illustrative levels. 3. Refiguration involves the viewers’ interpretation of the image, in other words, illustration and its reception. The process of narrating and interpreting time in the images takes place during these three moments of the photographic act.

However, when arranging the photographic piece or series, it is important that the different times be distinguished, since each one follows specific narrative strategies: 1. Objective time, defined by the precise moment at which the photograph was taken, is the referential time that is narrated on the basis of the textual marks in the image. 2 Represented time, shown in the photograph by the time frames that the photographer decides to include, is equivalent to the time of the story. 3. Symbolic time, when the image suggests a different reality to that represented, is constructed by creating ambiguity in meaning, or by recurring to visual rhetorical figures [such as metonymy, synechdoque and personification] or by the deliberate concealing of time frames. 4. Lastly, subjective time is determined by the point of view that the author applies to the image, but also by the context and interpretation of the viewer during the reconfiguration process. The latter two can be clearly seen in photographs created with artistic rather than documentary intentions, whose few referential elements make the images appear suspended in non-time. These photographs play with the viewer’s perception in order to elicit sensations, aesthetic emotions, uncertainty, or enable the latter to interpret and define its symbolic content and spatial-temporality.

1 Marzal Felice links sequentiality to narrative. However, here they are regarded as two separate processes as a broader concept of narrative is taken than the mere succession of events.

2 Much of the methodology proposed by Marzal is extracted from Santos Zunzunegui’s analysis in Paisajes de la forma. Ejercicios de análisis de la imagen. Cátedra, Madrid, 1988

Bibliografía

López Aguilar, E. (octubre de 2002). Julio Cortázar y la fotografía. La jornada semanal (397).

Bergson, H. (2007). La evolución creadora. Buenos Aires: Cactus.

Marzal Felici, J. (2011). Cómo se lee una fotografía. Madrid: Cátedra.

Ricoeur, P. (1995). Tiempo y narración (Vol. II). México: Siglo XXI.

Mónica Sánchez Ezcuer. Lives and works in Mexico. Writer and literature professor. Sociologist at the UNAM with a master in Literary Creation from the University of Texas. Currently she studies the master Visual Arts at San Carlos (UNAM). She collaborates in multidisciplinary projects; she has worked with musicians, painters and photographers in realizing operas, publications, concerts and exhibitions. She is especially interested in the relation between photography and narrative. She has given courses and workshops in literature and narrative in various institutions, like the UNAM, the University of Texas, Casa Lamm and the Foundation Pedro Meyer.

Mónica Sánchez Ezcuer. Lives and works in Mexico. Writer and literature professor. Sociologist at the UNAM with a master in Literary Creation from the University of Texas. Currently she studies the master Visual Arts at San Carlos (UNAM). She collaborates in multidisciplinary projects; she has worked with musicians, painters and photographers in realizing operas, publications, concerts and exhibitions. She is especially interested in the relation between photography and narrative. She has given courses and workshops in literature and narrative in various institutions, like the UNAM, the University of Texas, Casa Lamm and the Foundation Pedro Meyer.Mónica Sánchez Escuer

Pedro Meyer. Dhaka (Bangladesh), 2011

Stories are explicit, implicit or suggested within photographs. Photographs can expose a fragment of reality or express the totality of an event, but beyond showing or describing something, can photographs narrate? Narrating is a process as old as mankind. Telling daily events within the family nucleus, recalling the past, passing on traditions, creating and sharing the myths that lending meaning and structure to a community, is a practice that has been handed down from one generation to the next. Human beings explain themselves and the world they live in through tales spun from facts, feelings and hopes: the present acquires meaning through the past from which it came and from its vision of the future.

But tales have not always been told in words. If we think about the Paleolithic paintings in the Altamira or Benaojan caves, we can say that since prehistoric times, man has depicted the world and told of deeds through icons, long before the advent of writing. Let us recall that, “The evolution of language began with images, progressing to pictographs or self-explanatory vignettes, and subsequently phonetic units and lastly the alphabet” (Dondis, 2011, p. 11). Joan Fontcuberta believes that the meaning of an image lies in its narration: a photograph can simultaneously be an inscription and writing: “The language of photography constructs the story, insofar as the story lends meaning to the photograph” (Fontcuberta, 2004).

Nevertheless, what do we mean when we talk about narration? The Royal Academy defines the act of narrating as “telling, referring to events, or a fact or to a fictitious story” (Dictionary of the Spanish Language, 2001). This definition is broad enough to be applicable to any language: oral, written or graphic. Telling implies “enumeration”, a sequence of events; relating implies connecting people or actions; so narrating could be summarized as relating a series of connected events. Helena Berinstain, in her Dictionary of Rhetoric and Poetry states from a philological perspective that “narration is a statement of facts. The existence of narration requires relatable events. In general, the relation of a series of events is called a tale. […] These events are developed across time and are derived from one another, which is why they simultaneously offer a consecutive relationship[before/after] and a logical relationship [cause/effect]” (Berinstain, 1995, p. 355). So how can we apply these parameters to photography? Can an event be told in an image, can a tale be told? When we talk about an event, we are necessarily talking about time. An event can be made of a number of actions in a finite period of time, even if this time lasts only seconds. Photography freezes an instant. Its ability to be narrative will depend of the amount of information with which we are provided to suggest or reveal the facts that were not captured. There are photographs in which, through the composition of the elements depicted, the title or the accompanying caption, a sequence of events is explained or insinuated. In some, actions that take place before or after the moment captured can clearly be inferred. These are undoubtedly images that contain a narrative of their own.

When capturing a story, the photographer must focus, frame, calculate the light, and use not only formal strategies and visual techniques, but also a narrative and strategic discursive: at a general level, a scene, scenery or place is described; on the median plane, the narrative discourse is signaled by the elements in action; and on the first plane expressive language is indicated by details that convey emotions and feelings. Or it uses visual rhetoric, figures that are equivalent to literary rhetoric: metaphors, where an object or content is evoked by analogy with another element with shared characteristics; metonymy, when the object the image refers to is replaced by a related element; synecdoche when a total is represented in a detail or close-up; personification, when inanimate objects or animals are given human qualities, etc.

The clearest form of photographic narration in through diptychs, triptychs or multi-frame sequential images that illustrate different moments in the plot. The selection and arrangement of grouped photographs provides space and time coordinates allowing us to place and perceive the course of action through the illusion of movement, which an image alone could not give. In photographic sequences there is ellipsis in narrative time, not everything is told, and so the spectators’ imagination inserts the missing pieces. In movies and video, images flow smoothly, movement is evident, not simulated; and though the time ellipsis is a commonly used device in audiovisual discourse, the story is narrated in a continual and usually, explicit manner. Between the two visual forms of narration, photography or a series of photographs, and movies or video, a digital tale and a photo narrative can be found where the sequence of actions is dictated by the order of the still or moving images, the text (if there is any), and other artistic and formal features such as visual and sound rhythm.

All visual tales—but not all images—are constructed in the same way as literary tales. The elements are the same: a theme, a story, characters, a specific setting. The plot generally develops according to the formal precepts of a classic tale: It begins with an approach to the story, the conflict is explained, and the outcome is developed. An appropriate pace for the establishment and dosage of actions is created, planes, times and lighting are played with to create visual and narrative tension. In a story, the point is not to explain or show but to tell; and this is what literary narration consists of: telling and describing actions without explaining them. In audiovisual narration, the story arises not only from the actions but also through the images, that is, the telling is the showing, “The narrative is scenic and representational, it is a dramatized act”; (García García, 2006, p. 12). At the same time, showing is telling; actions are reinforced and made effective through imagery and audiovisual codes.

[core_state] => 1 [core_access] => 1 [core_metadata] => {"robots":"","author":"Mónica Sánchez Escuer","rights":"","xreference":""} [core_created_user_id] => 838 [core_created_by_alias] => [core_created_time] => 2015-01-26 21:52:02 [core_images] => {"image_intro":"images\/categories\/photonarrative\/ezcuer.jpg","float_intro":"","image_intro_alt":"","image_intro_caption":"","image_fulltext":"images\/categories\/photonarrative\/ezcuer.jpg","float_fulltext":"","image_fulltext_alt":"","image_fulltext_caption":""} [core_modified_time] => 2015-04-27 18:24:44 [core_language] => en-GB [core_catid] => 52 [core_publish_up] => 2015-01-26 21:52:02 [core_publish_down] => 0000-00-00 00:00:00 [content_type_title] => Article [router] => ContentHelperRoute::getArticleRoute [author] => Elisa Rugo [author_email] => elisa@zonezero.com [link] => index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=245:photo-narrative-the-stories-in-an-image&catid=52&lang=en-GB [displayDate] => 2015-01-26 21:52:02 [event] => stdClass Object ( [afterDisplayTitle] => [beforeDisplayContent] => [afterDisplayContent] => ) [text] =>

Pedro Meyer. Dhaka (Bangladesh), 2011

Stories are explicit, implicit or suggested within photographs. Photographs can expose a fragment of reality or express the totality of an event, but beyond showing or describing something, can photographs narrate? Narrating is a process as old as mankind. Telling daily events within the family nucleus, recalling the past, passing on traditions, creating and sharing the myths that lending meaning and structure to a community, is a practice that has been handed down from one generation to the next. Human beings explain themselves and the world they live in through tales spun from facts, feelings and hopes: the present acquires meaning through the past from which it came and from its vision of the future.

But tales have not always been told in words. If we think about the Paleolithic paintings in the Altamira or Benaojan caves, we can say that since prehistoric times, man has depicted the world and told of deeds through icons, long before the advent of writing. Let us recall that, “The evolution of language began with images, progressing to pictographs or self-explanatory vignettes, and subsequently phonetic units and lastly the alphabet” (Dondis, 2011, p. 11). Joan Fontcuberta believes that the meaning of an image lies in its narration: a photograph can simultaneously be an inscription and writing: “The language of photography constructs the story, insofar as the story lends meaning to the photograph” (Fontcuberta, 2004).

Nevertheless, what do we mean when we talk about narration? The Royal Academy defines the act of narrating as “telling, referring to events, or a fact or to a fictitious story” (Dictionary of the Spanish Language, 2001). This definition is broad enough to be applicable to any language: oral, written or graphic. Telling implies “enumeration”, a sequence of events; relating implies connecting people or actions; so narrating could be summarized as relating a series of connected events. Helena Berinstain, in her Dictionary of Rhetoric and Poetry states from a philological perspective that “narration is a statement of facts. The existence of narration requires relatable events. In general, the relation of a series of events is called a tale. […] These events are developed across time and are derived from one another, which is why they simultaneously offer a consecutive relationship[before/after] and a logical relationship [cause/effect]” (Berinstain, 1995, p. 355). So how can we apply these parameters to photography? Can an event be told in an image, can a tale be told? When we talk about an event, we are necessarily talking about time. An event can be made of a number of actions in a finite period of time, even if this time lasts only seconds. Photography freezes an instant. Its ability to be narrative will depend of the amount of information with which we are provided to suggest or reveal the facts that were not captured. There are photographs in which, through the composition of the elements depicted, the title or the accompanying caption, a sequence of events is explained or insinuated. In some, actions that take place before or after the moment captured can clearly be inferred. These are undoubtedly images that contain a narrative of their own.

When capturing a story, the photographer must focus, frame, calculate the light, and use not only formal strategies and visual techniques, but also a narrative and strategic discursive: at a general level, a scene, scenery or place is described; on the median plane, the narrative discourse is signaled by the elements in action; and on the first plane expressive language is indicated by details that convey emotions and feelings. Or it uses visual rhetoric, figures that are equivalent to literary rhetoric: metaphors, where an object or content is evoked by analogy with another element with shared characteristics; metonymy, when the object the image refers to is replaced by a related element; synecdoche when a total is represented in a detail or close-up; personification, when inanimate objects or animals are given human qualities, etc.

The clearest form of photographic narration in through diptychs, triptychs or multi-frame sequential images that illustrate different moments in the plot. The selection and arrangement of grouped photographs provides space and time coordinates allowing us to place and perceive the course of action through the illusion of movement, which an image alone could not give. In photographic sequences there is ellipsis in narrative time, not everything is told, and so the spectators’ imagination inserts the missing pieces. In movies and video, images flow smoothly, movement is evident, not simulated; and though the time ellipsis is a commonly used device in audiovisual discourse, the story is narrated in a continual and usually, explicit manner. Between the two visual forms of narration, photography or a series of photographs, and movies or video, a digital tale and a photo narrative can be found where the sequence of actions is dictated by the order of the still or moving images, the text (if there is any), and other artistic and formal features such as visual and sound rhythm.

All visual tales—but not all images—are constructed in the same way as literary tales. The elements are the same: a theme, a story, characters, a specific setting. The plot generally develops according to the formal precepts of a classic tale: It begins with an approach to the story, the conflict is explained, and the outcome is developed. An appropriate pace for the establishment and dosage of actions is created, planes, times and lighting are played with to create visual and narrative tension. In a story, the point is not to explain or show but to tell; and this is what literary narration consists of: telling and describing actions without explaining them. In audiovisual narration, the story arises not only from the actions but also through the images, that is, the telling is the showing, “The narrative is scenic and representational, it is a dramatized act”; (García García, 2006, p. 12). At the same time, showing is telling; actions are reinforced and made effective through imagery and audiovisual codes.

[id] => 245 [language] => en-GB [catid] => 52 [jcfields] => Array ( ) ) 1

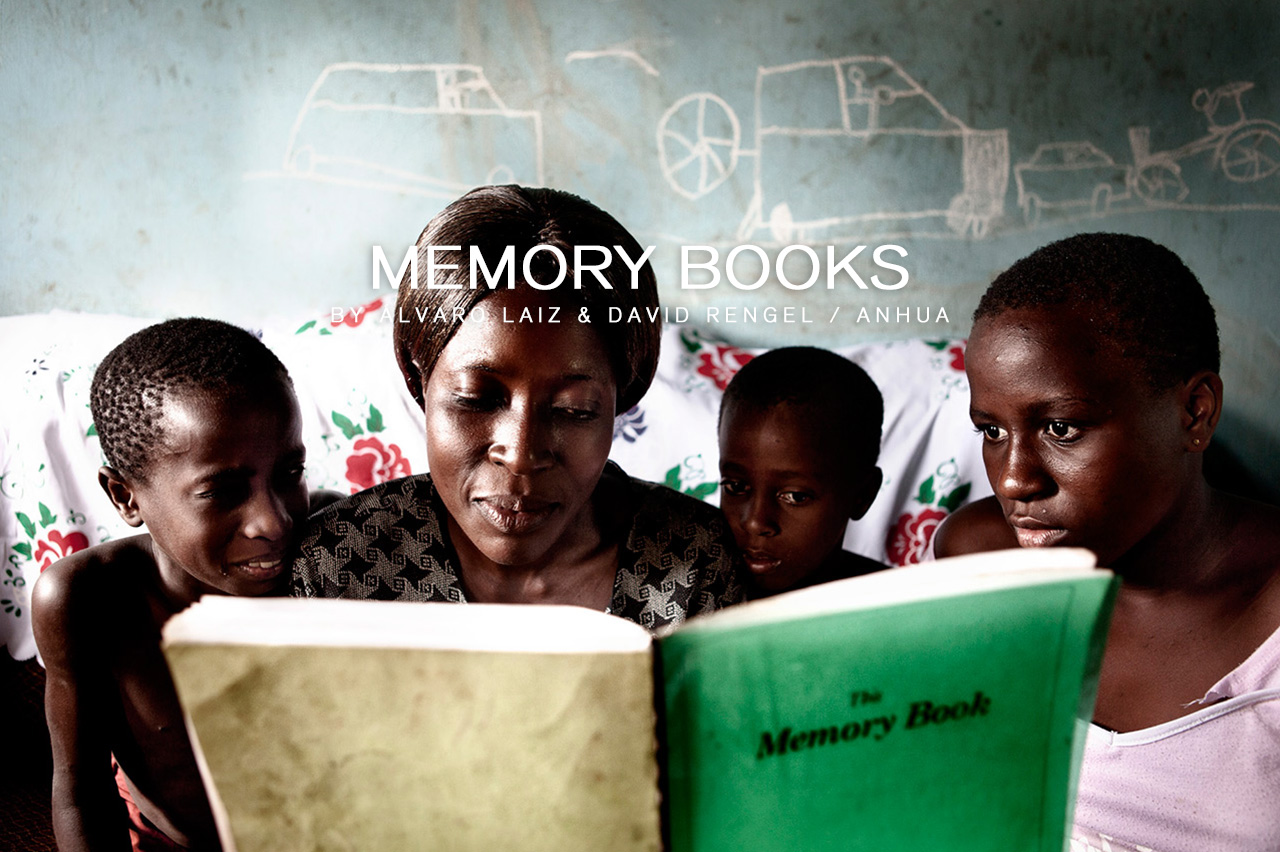

Álvaro Laiz & David Rengel / AnHua

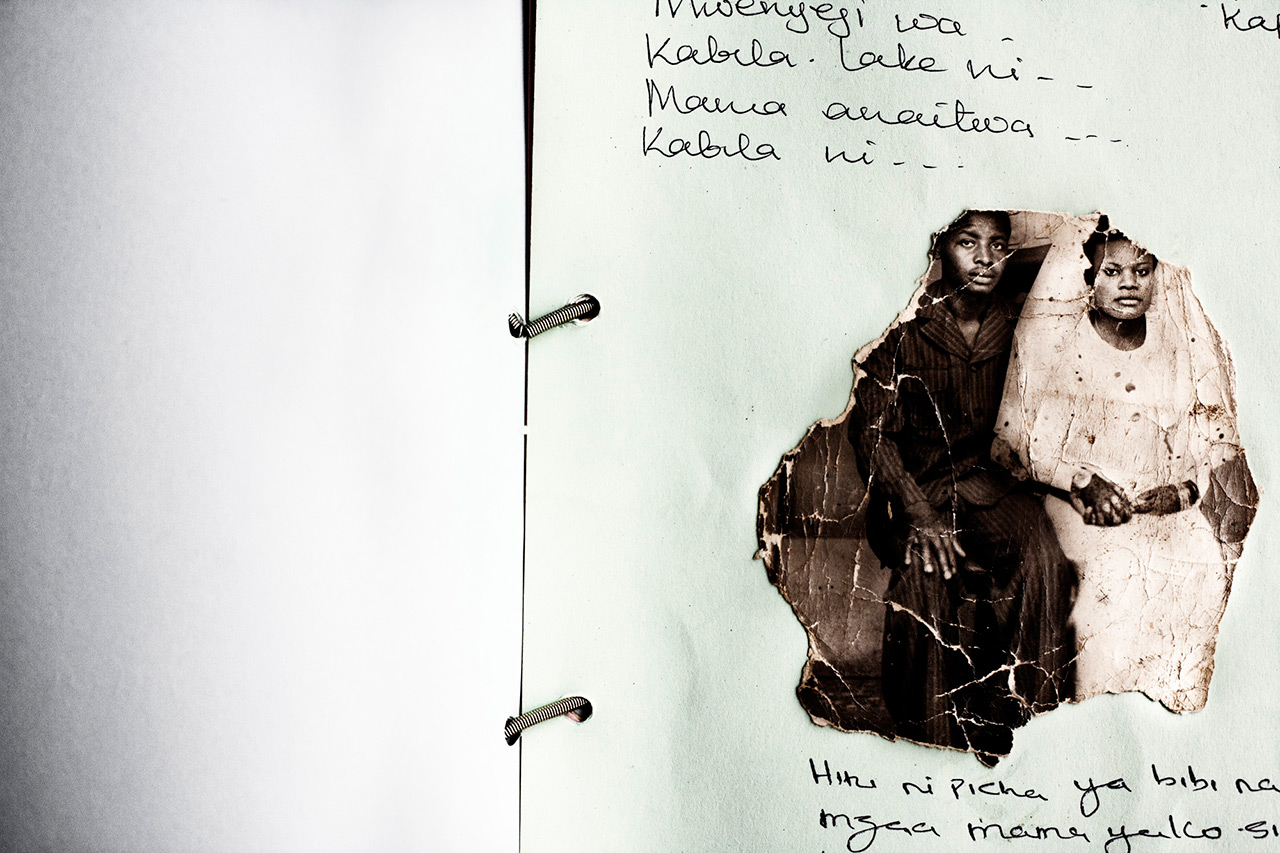

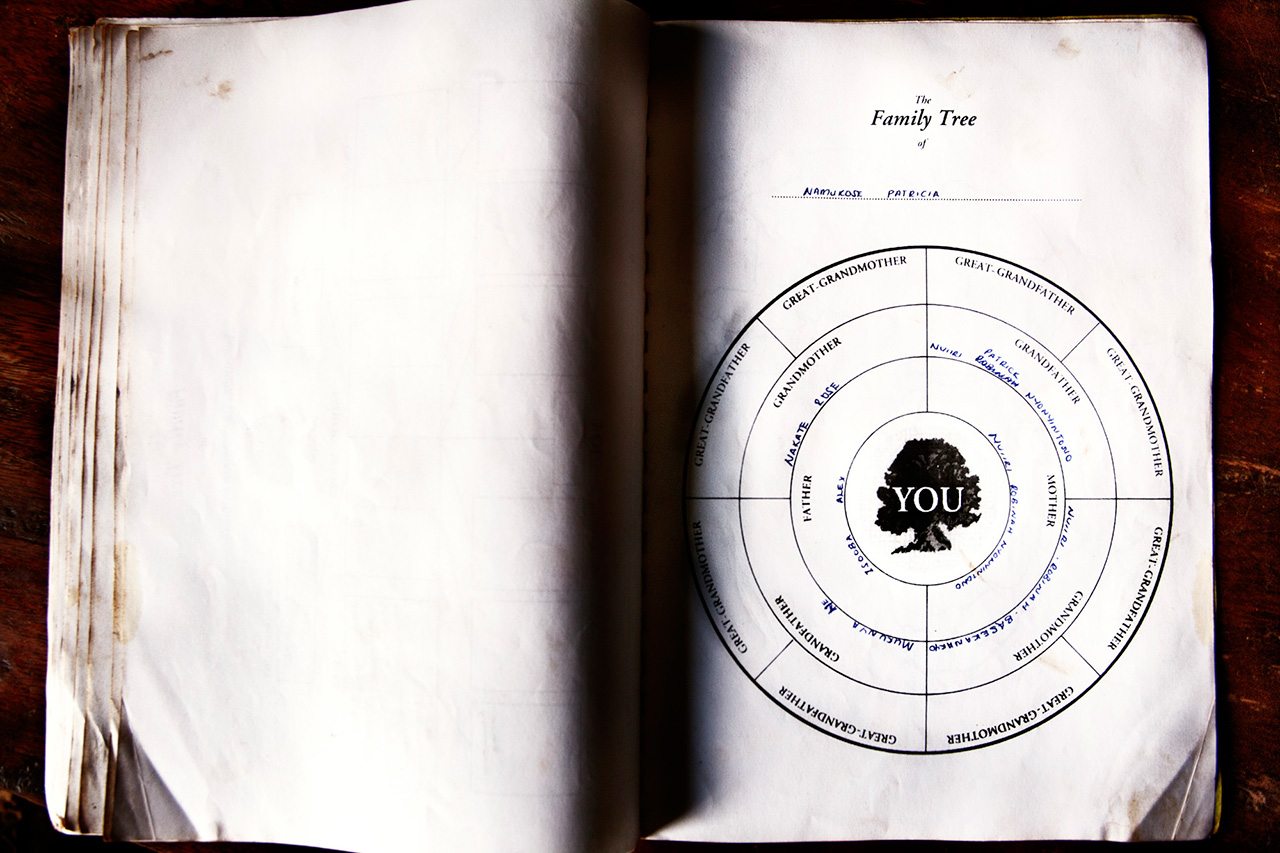

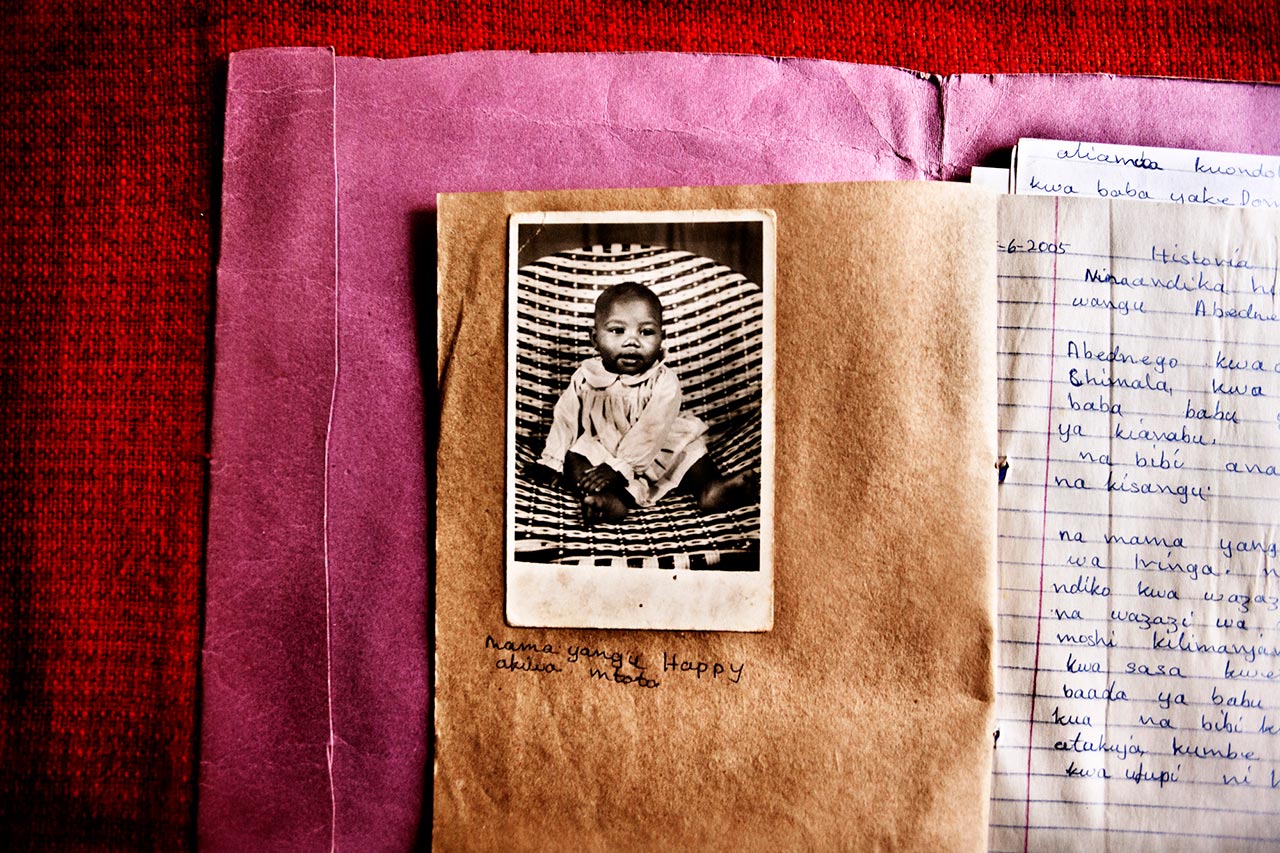

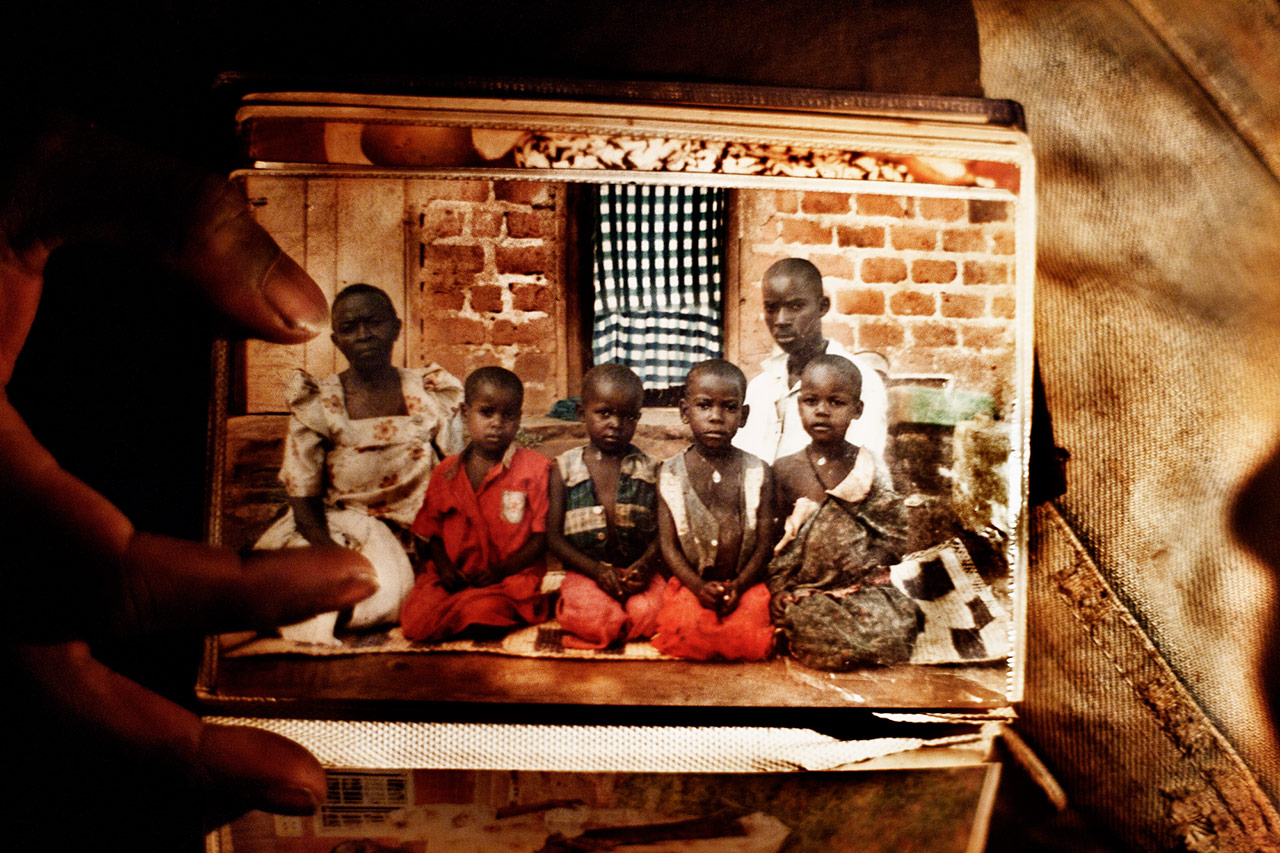

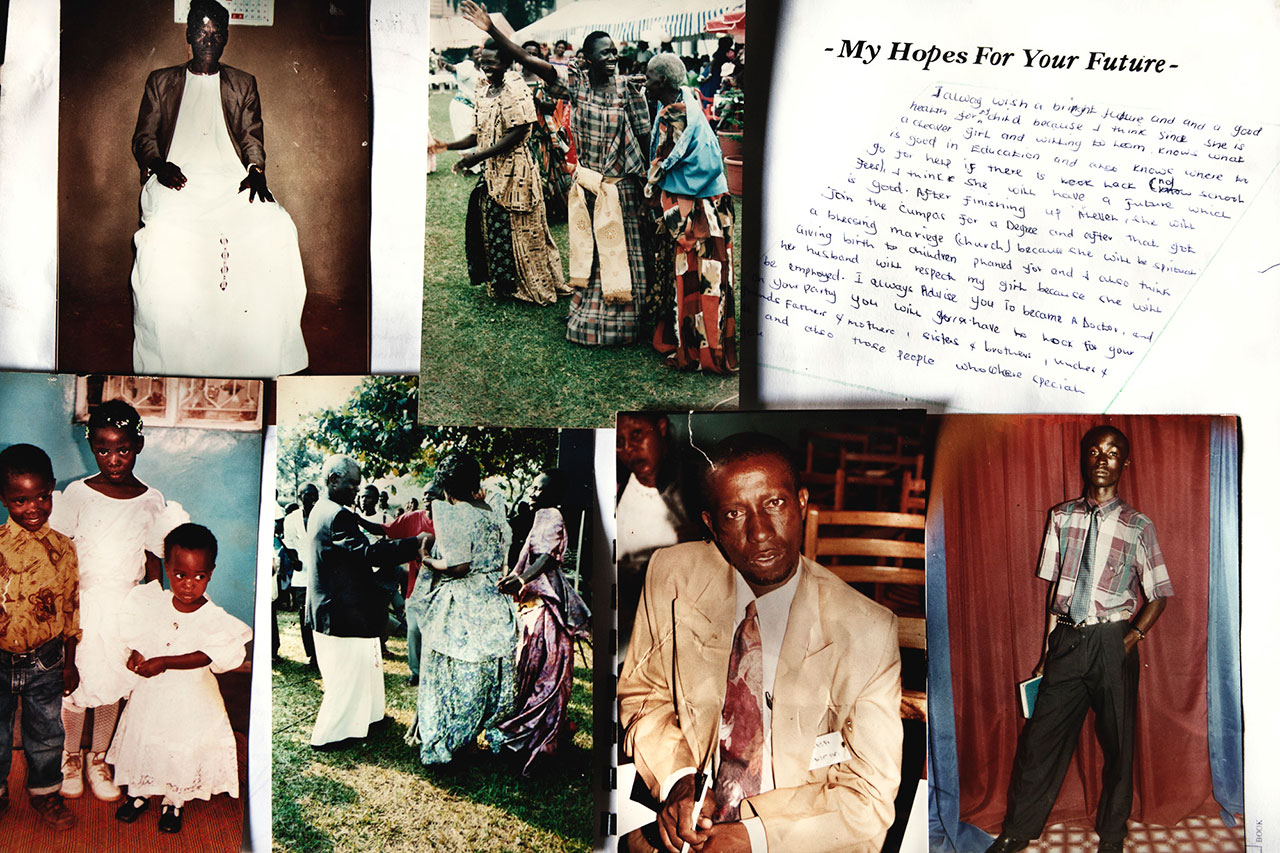

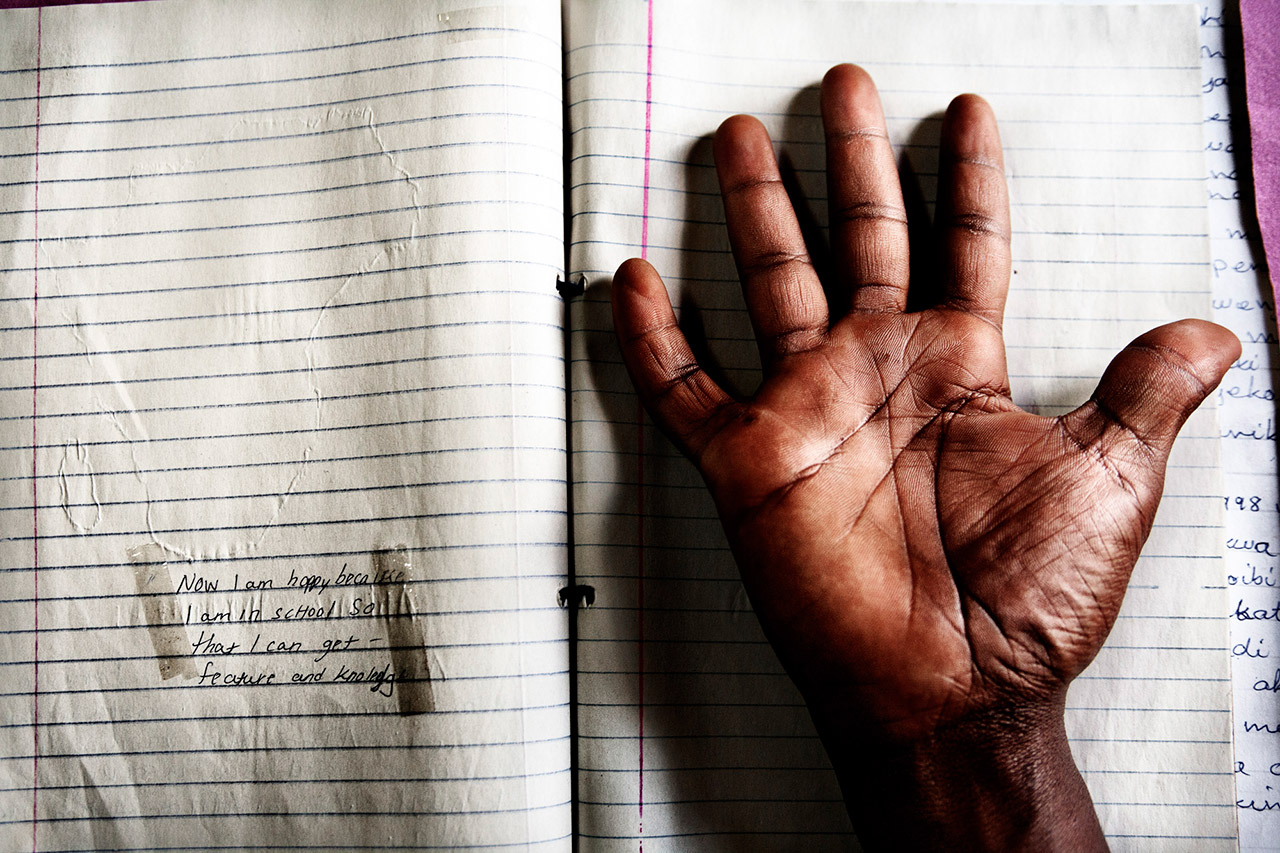

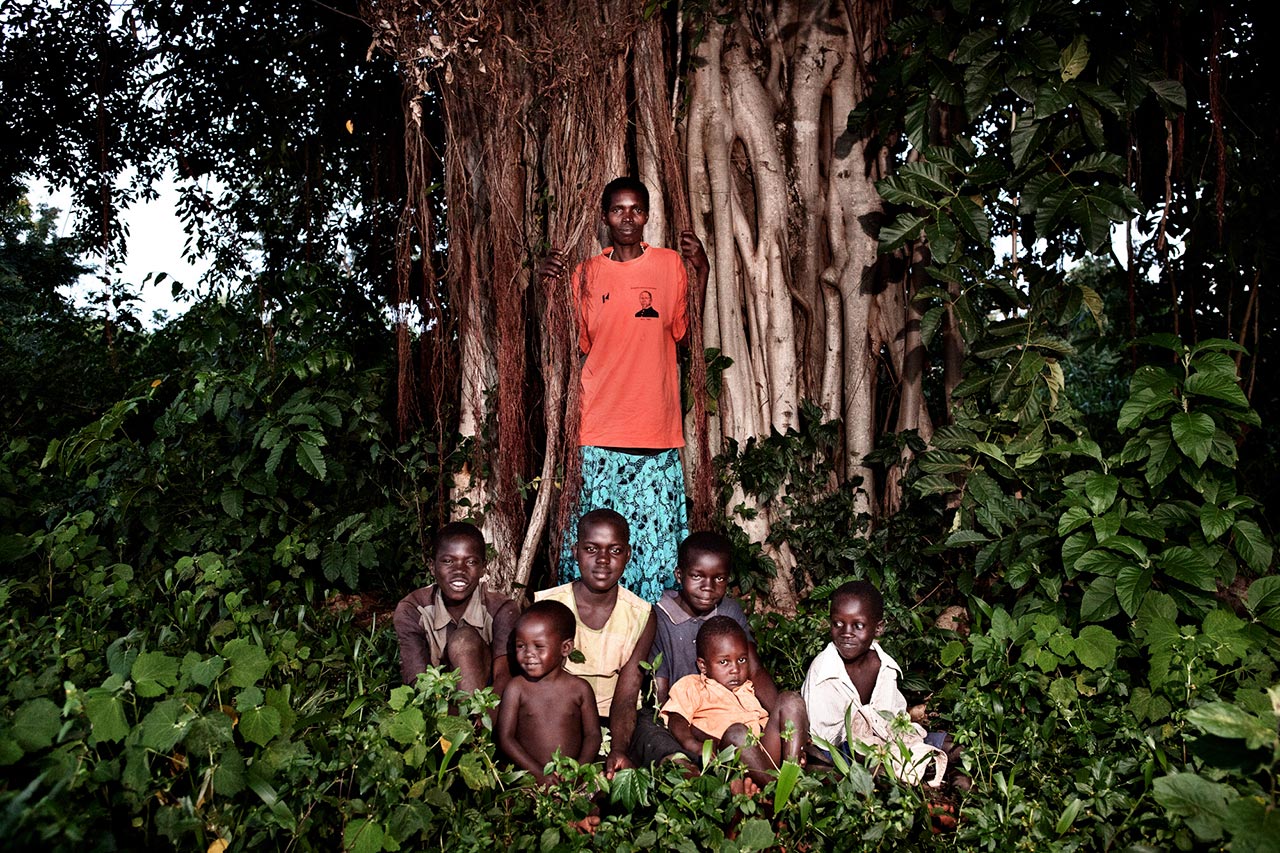

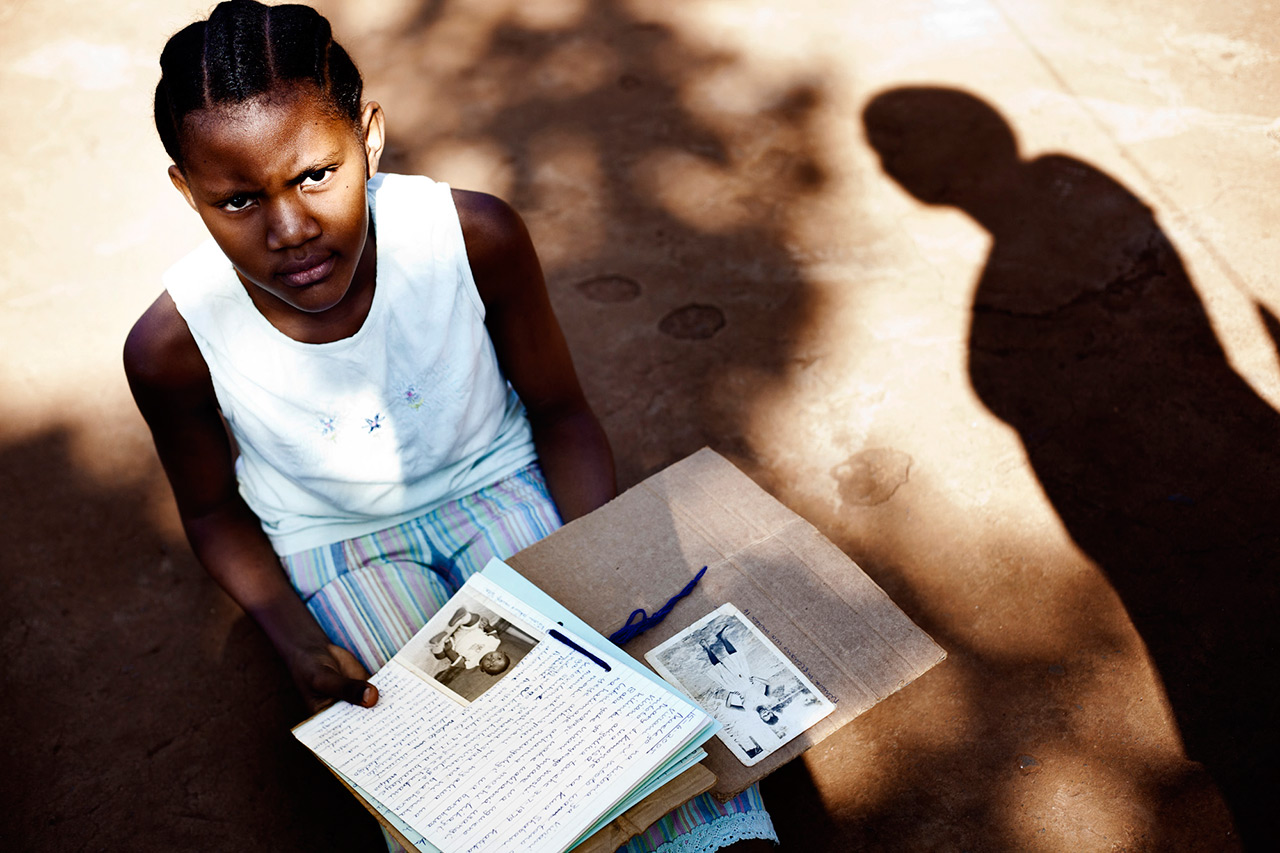

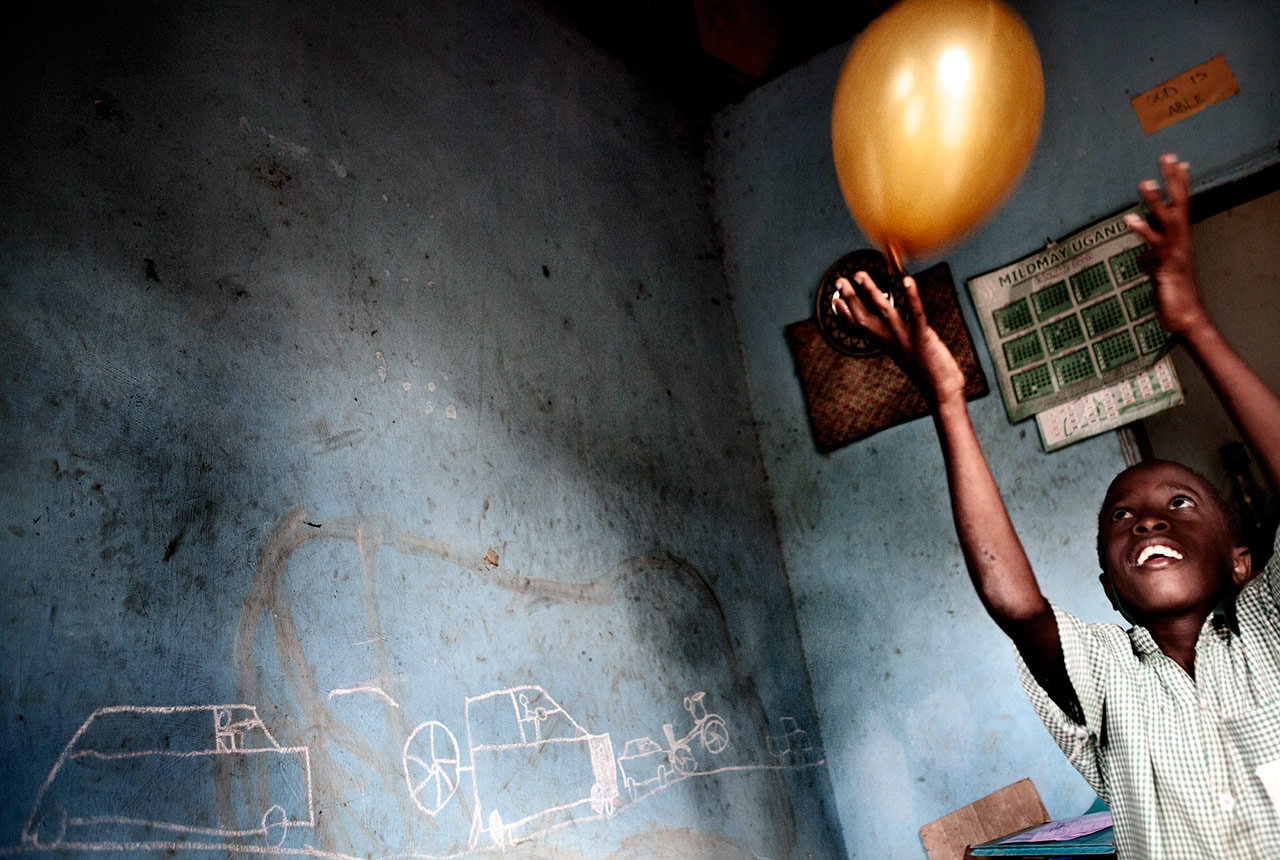

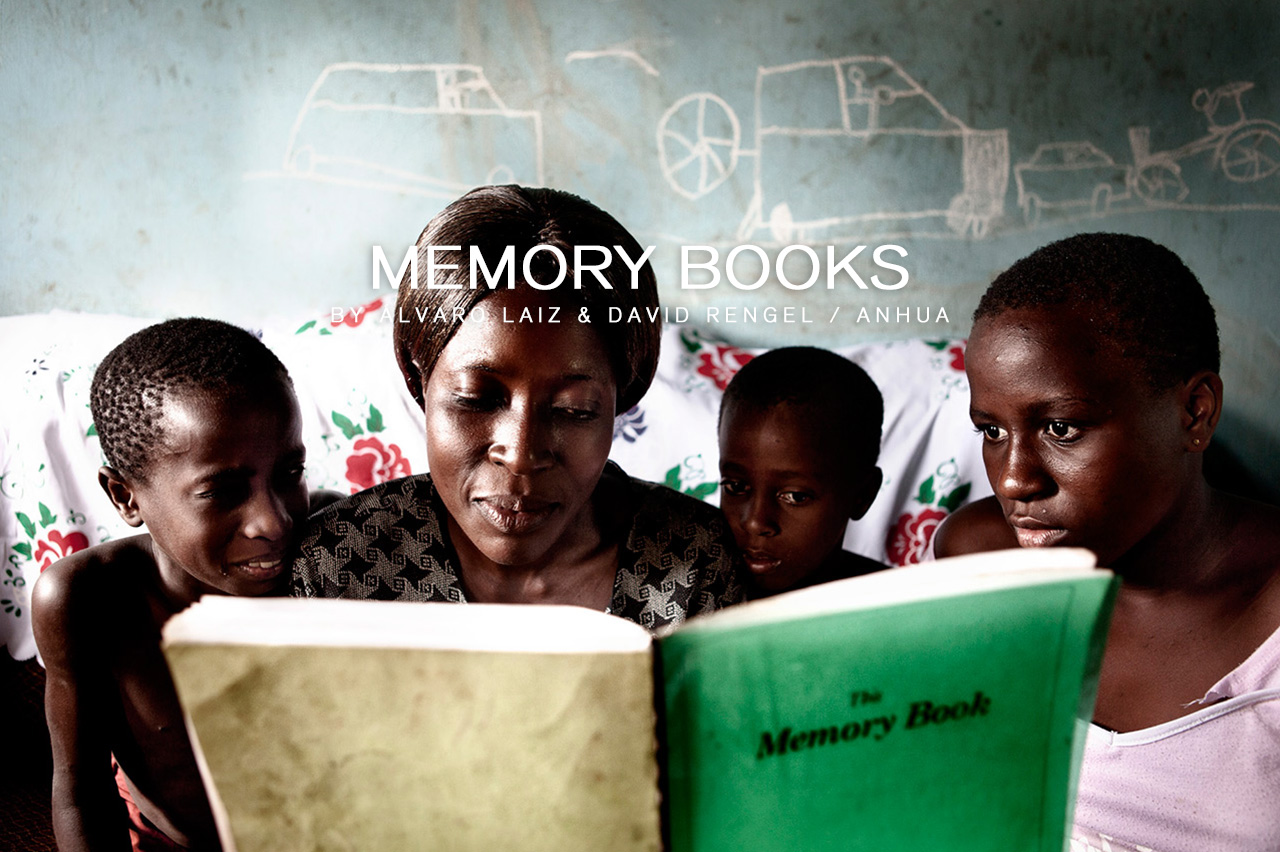

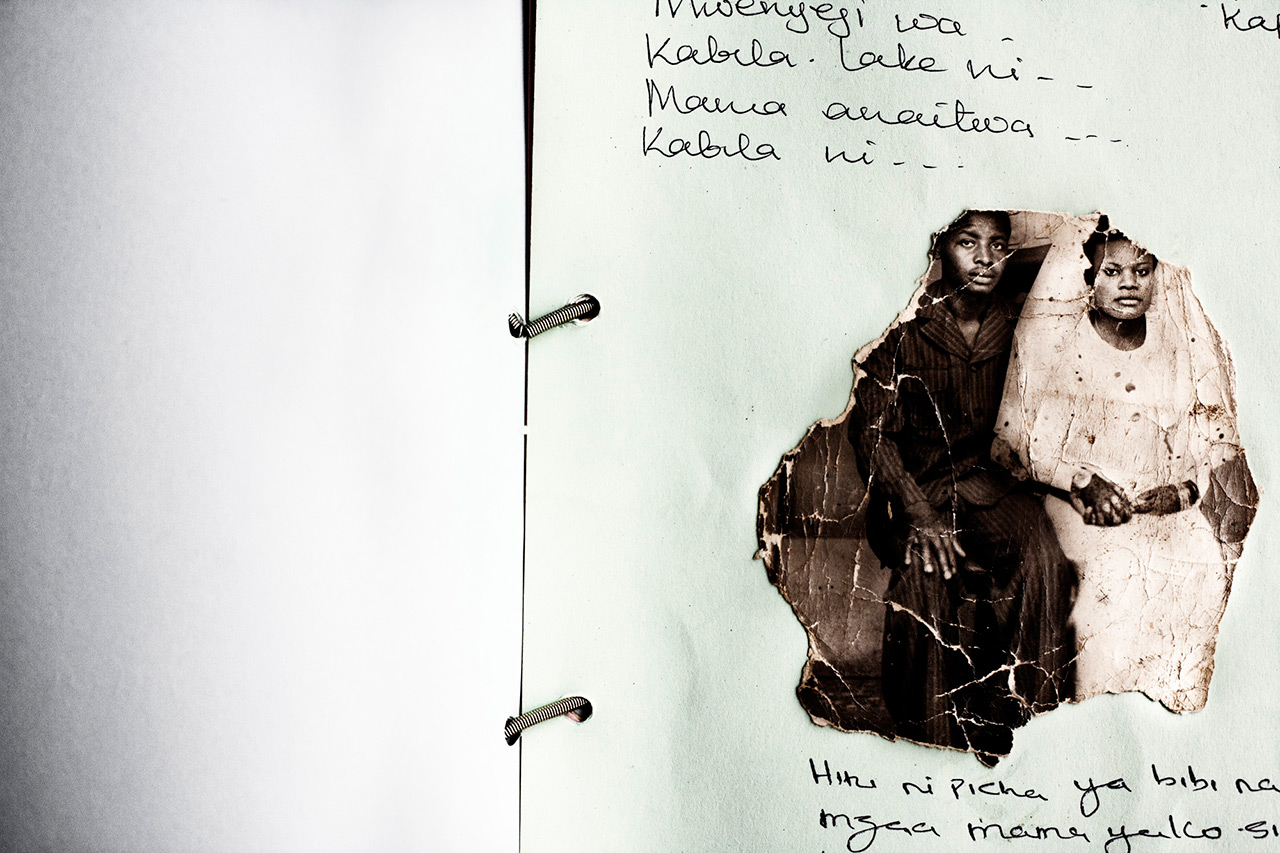

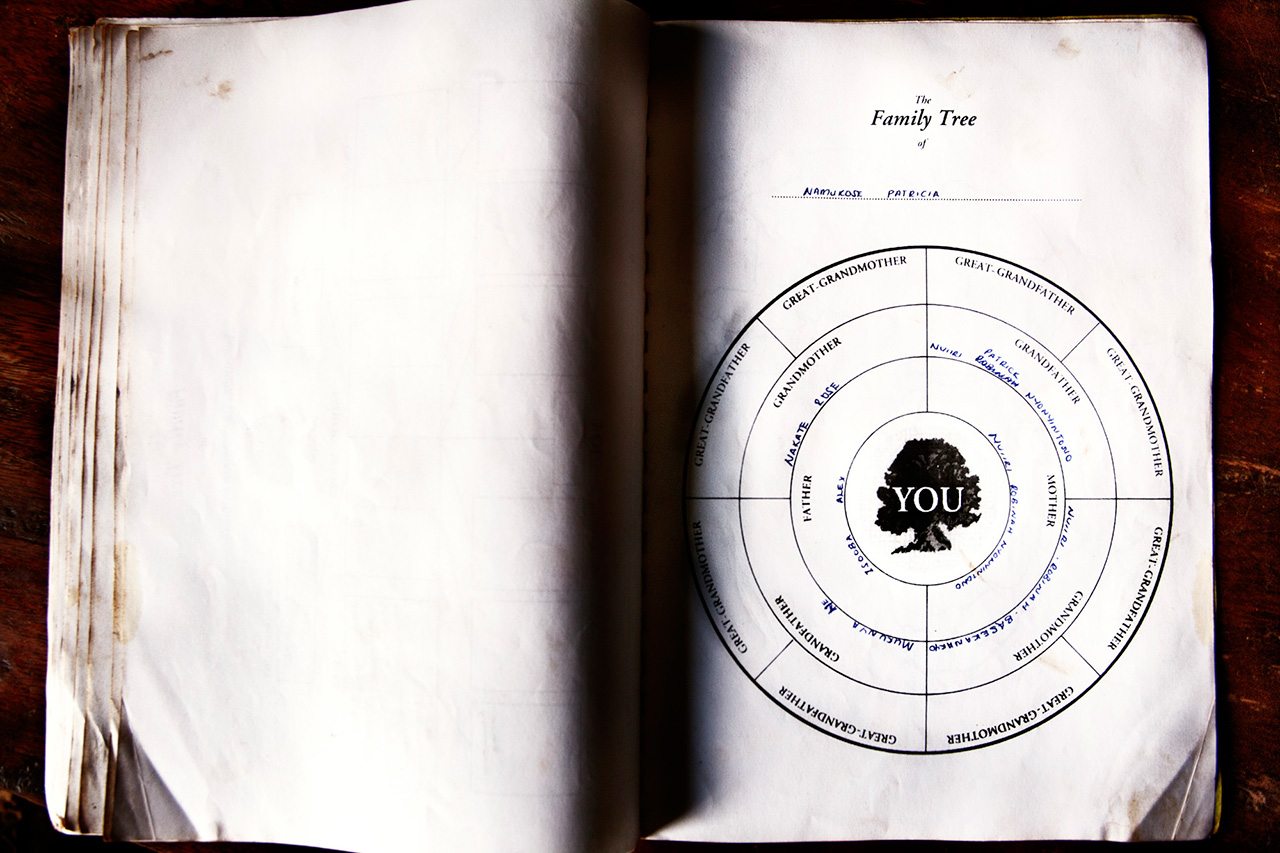

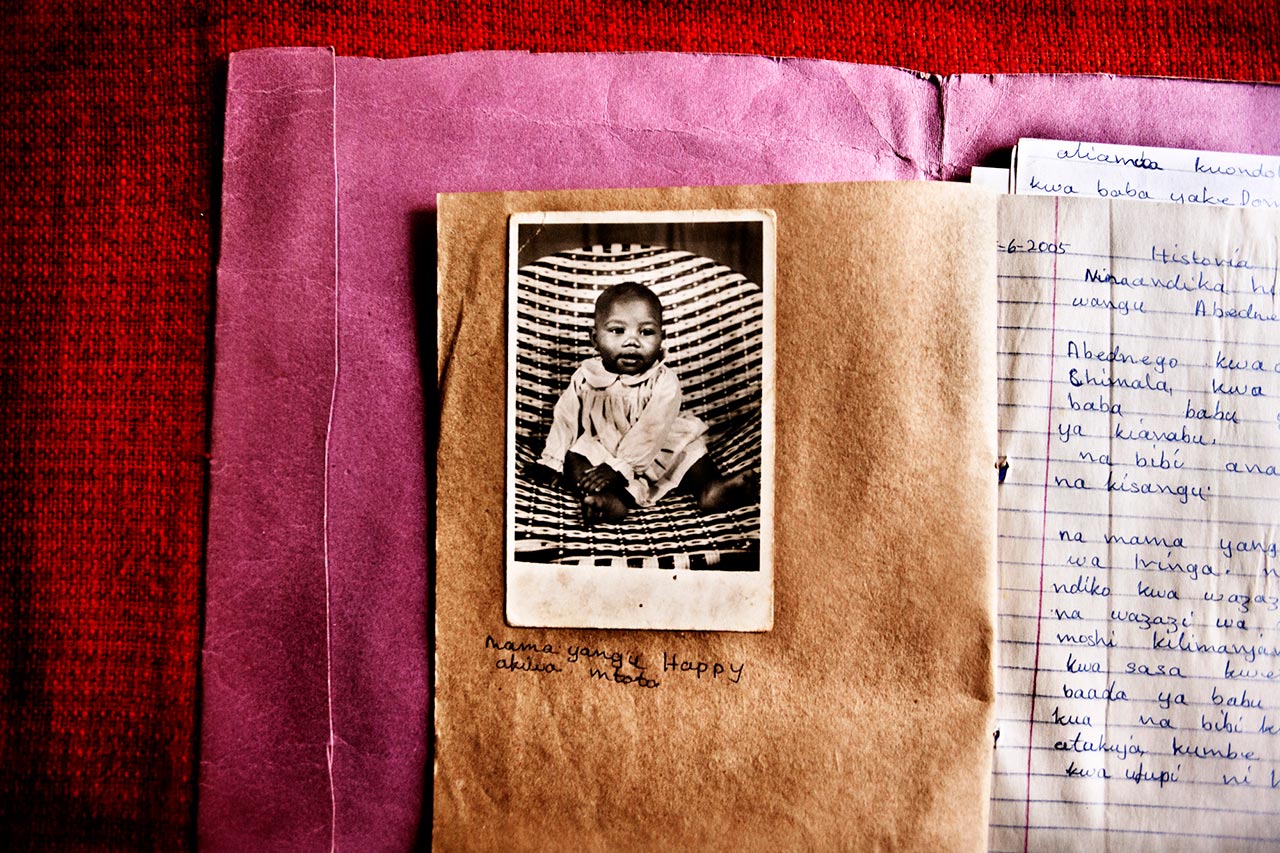

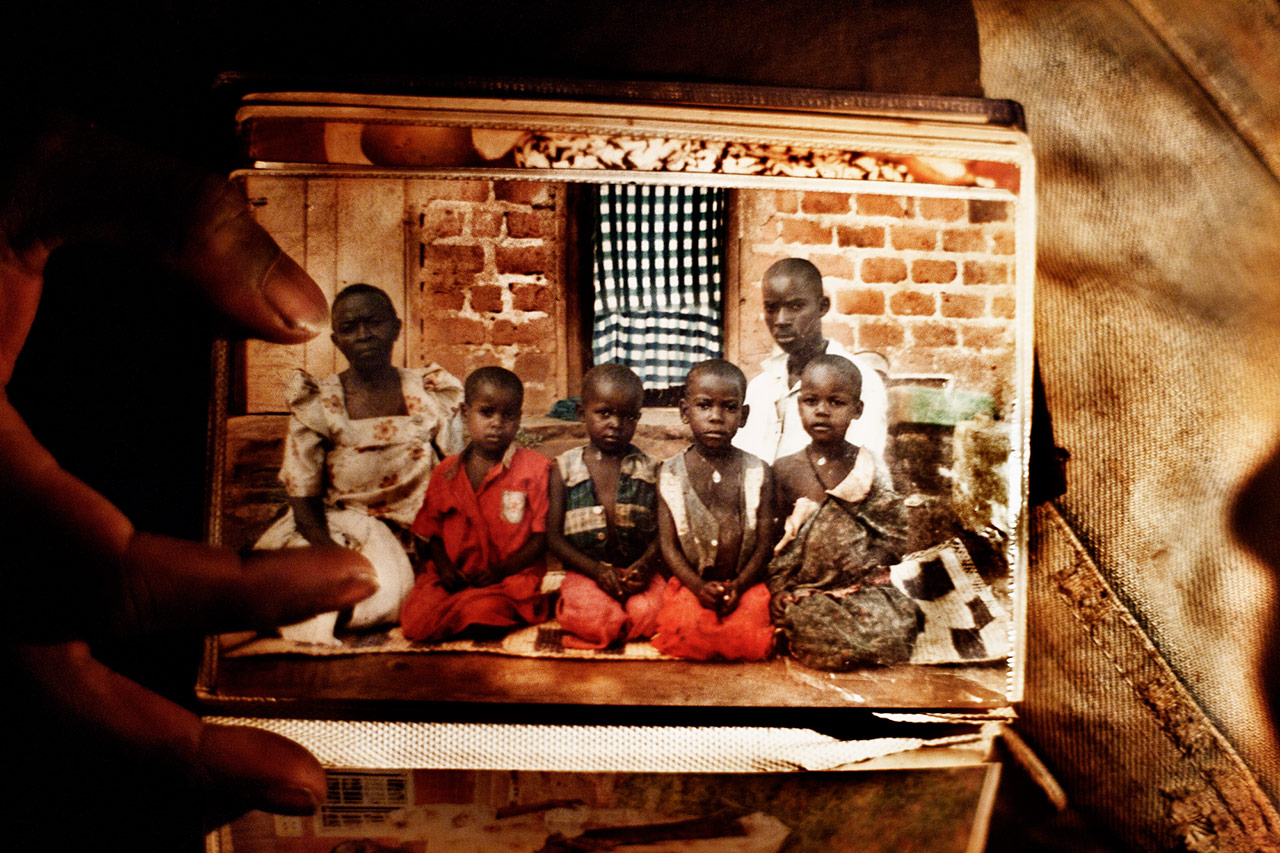

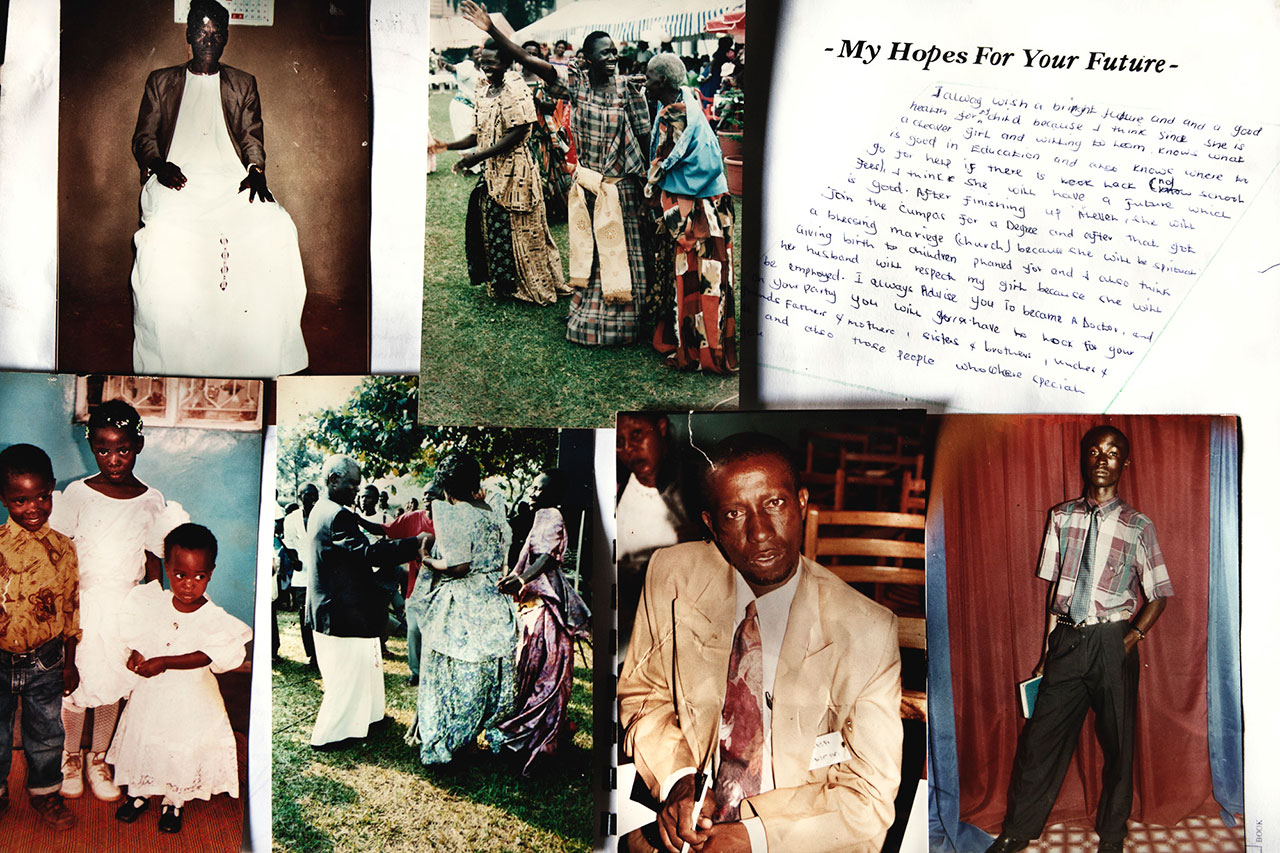

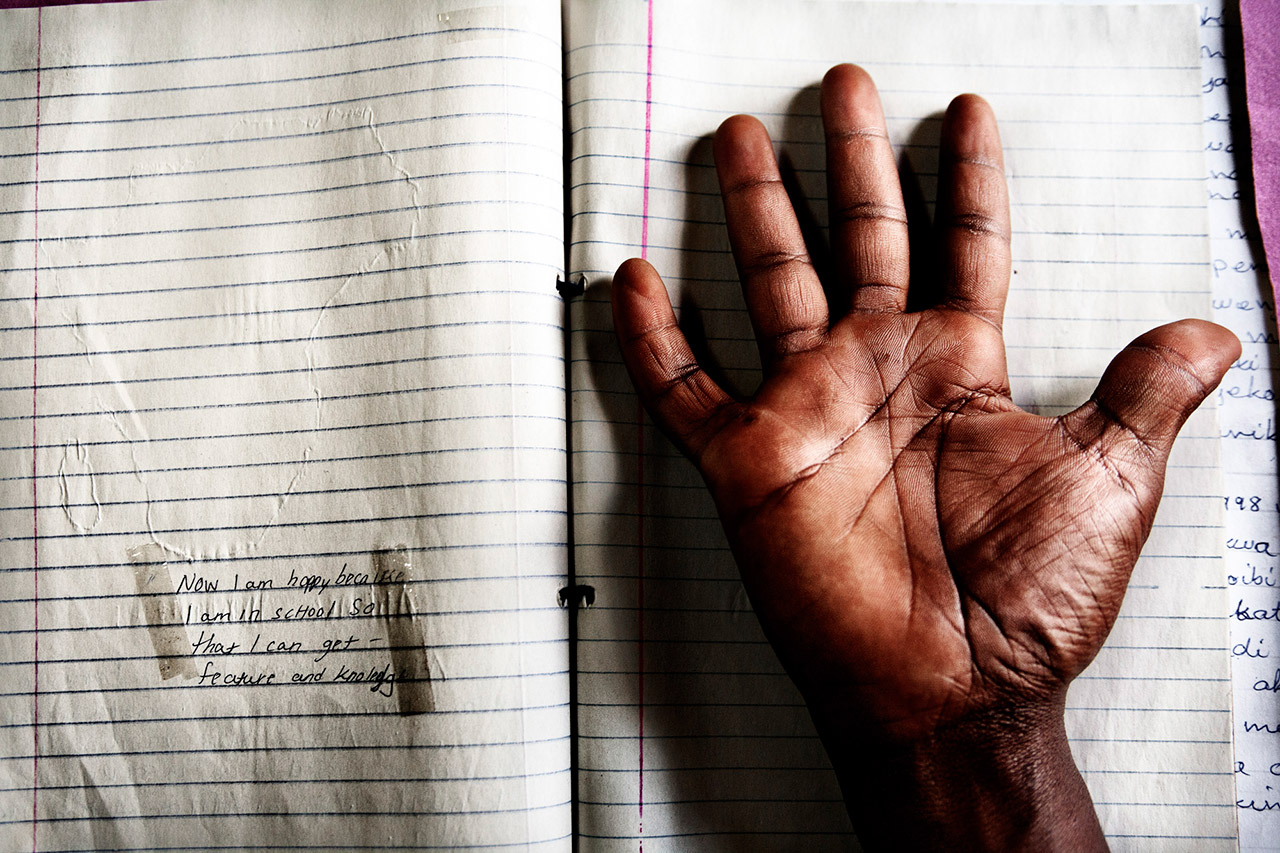

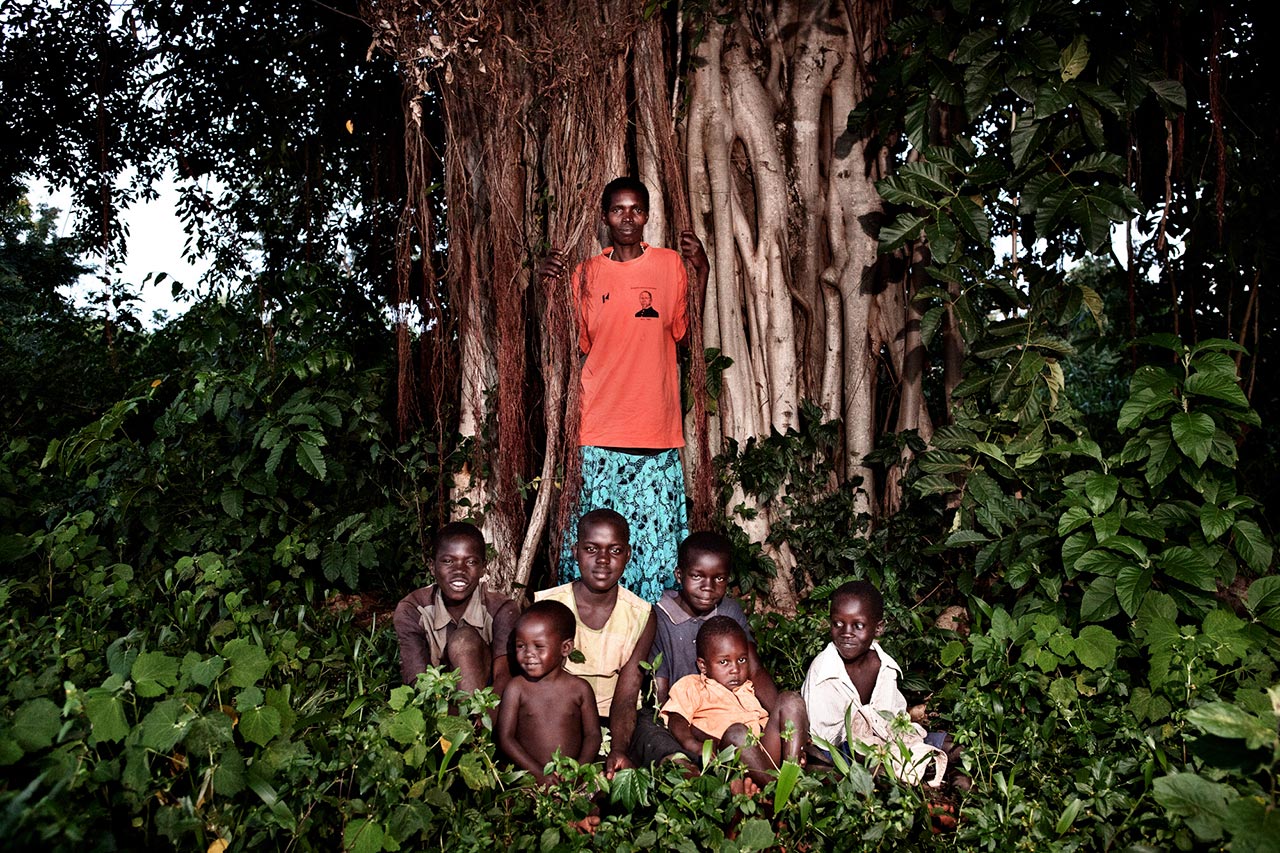

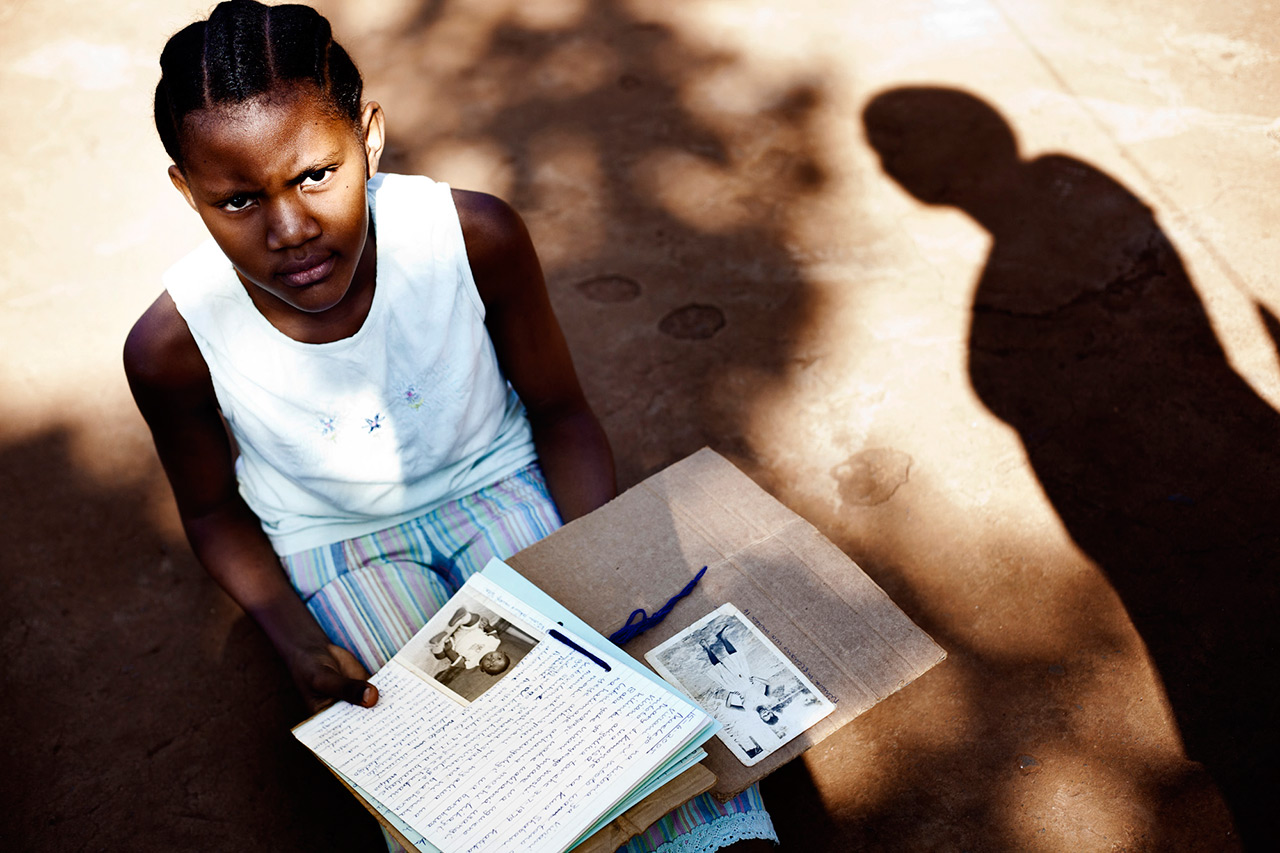

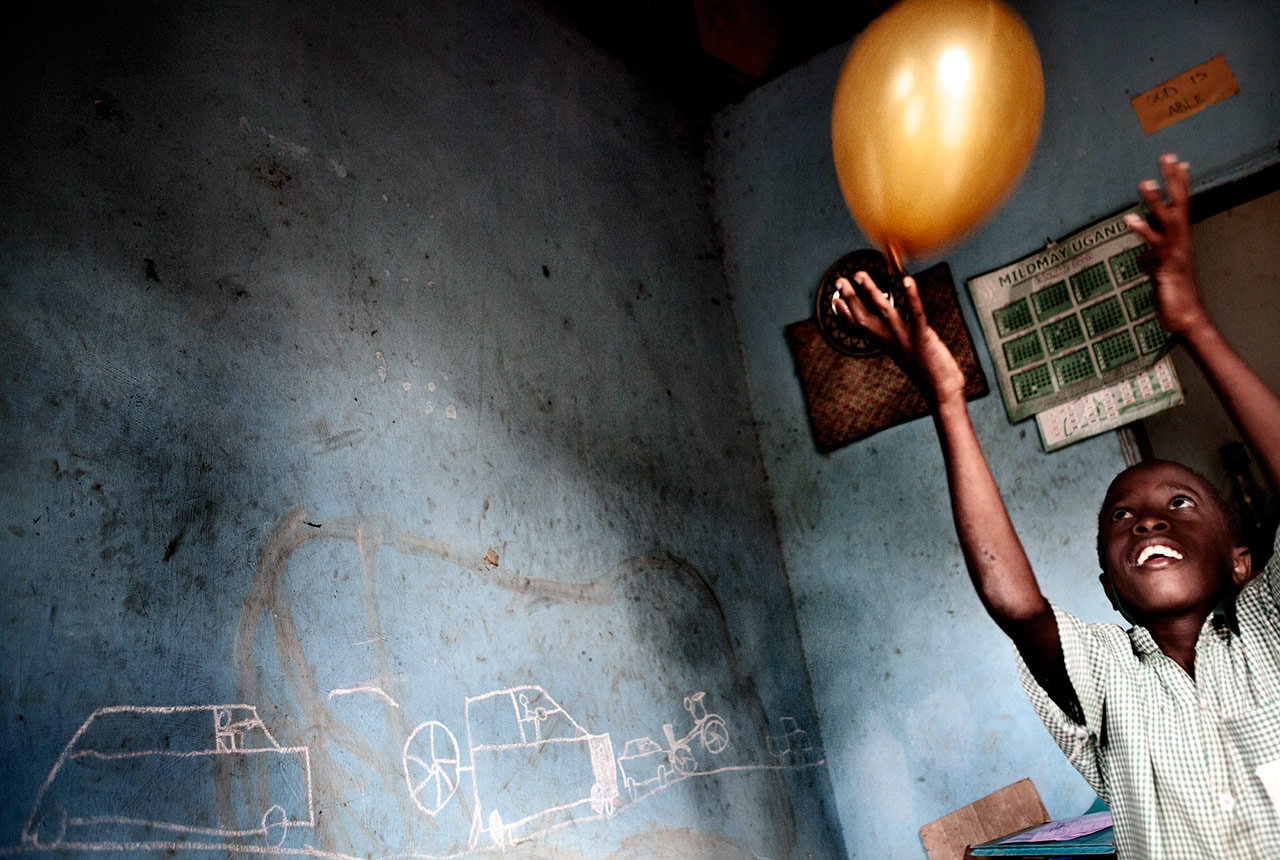

In Uganda, by the beginning of the nineties, corpses kept piling up in the morgues and nobody knew what was going on. During the days when it seemed like hope had escaped that land, a few HIV positive women decided to bring it back, not for them but for their children. That is how NACWOLA (National Community of Women Living with HIV/AIDS) was born, during the International Conference on AIDS held in Amsterdam in 1992. The three founding members died of AIDS during the following years, but their legacy was a ray of light in the darkest days. With the help of European health and psychology professionals, the decided to put in writing what they would never be able to tell their children, and they created the Memory Books. These books are their recollections, they tell us about them and the future they want for their children n pages full of words of care and affection. They are motherhood guides from beyond, survival tutorials for lost children, since over 12% of Sub-Saharan underage population will lose at least one of their parents in the next 12 months, and they will be on their own. As Gladys, the person in charge of the Memory Books project in Luwero, the center of the country, tell us: "They are each special and very personal, in spite of following a common pattern that includes family photos, memories and a family tree. With these books we encourage parents to listen to their children, to talk to them frankly about their disease."

The project is like a big family with members helping each other emotionally and financially in their daily struggle for survival. Mothers, orphans and grandmothers, many of them displaced by the internal war with the LRA (Lord's Resistance Army). In a country where 35% of the population is HIV positive, where there are two million orphans, a country in which polygamy and dowry are common practice, these women are struggling against the AIDS stigma and are not afraid of anything. NACWOLA and the project have given them back hope.

*ANHUA is a Chinese term that means what the backlight is only seen. His philosophy rests on a fundamental idea: to "Light" the forgotten. Forgotten for any reason: war, displacement, environmental disaters, threats or violations of human rights. We want to help strengthen communication between associations and NGOs from different geographical areas that have no visible spaces to deliver their work and projects. We see in the documentary reports as a tool to approach different interpretations of our environment and help to change unjust realities. We firmly believe that creativity applied to new ways and audiovisual communication is essential in order to promote social change to disadvantaged or minority communities, and also we want to spread world awareness of these situations in the Western. Giving voice to those that no one wants to hear from the direct involvement and through witness always sincere, promoting cultural, educational and social action.

Alvaro Laiz (León, 1981) Master in Visual Arts de Universidad Pontificia de Salamanca. His photographic work focuses on realities that are often forgotten, in areas like Africa, Asia or Southern America. For Laiz, documentary photography is a tool with which he can approach stories that fascinate or worry him, or stories in which he wants to participate from his point of view. With this mindset he co-founded the ONG An-Hua. His work has been published in media like the Sunday Times Magazine, Forbes, British Journal of Photography, National Geographic o New York Times among others.

Alvaro Laiz (León, 1981) Master in Visual Arts de Universidad Pontificia de Salamanca. His photographic work focuses on realities that are often forgotten, in areas like Africa, Asia or Southern America. For Laiz, documentary photography is a tool with which he can approach stories that fascinate or worry him, or stories in which he wants to participate from his point of view. With this mindset he co-founded the ONG An-Hua. His work has been published in media like the Sunday Times Magazine, Forbes, British Journal of Photography, National Geographic o New York Times among others. David Rangel (Torreblanca de los Caños, Sevilla. 1978) Photographer and documentary filmmaker. His professional activity is related to the film industry for over 14 years. Co-founder of An-Hua in order to publicize the forgotten conflicts and document the social, historical and contemporary changes. Focused its commitment issues and concerns related to human rights, anthropology, economics and environment.

David Rangel (Torreblanca de los Caños, Sevilla. 1978) Photographer and documentary filmmaker. His professional activity is related to the film industry for over 14 years. Co-founder of An-Hua in order to publicize the forgotten conflicts and document the social, historical and contemporary changes. Focused its commitment issues and concerns related to human rights, anthropology, economics and environment.

In Uganda, by the beginning of the nineties, corpses kept piling up in the morgues and nobody knew what was going on. During the days when it seemed like hope had escaped that land, a few HIV positive women decided to bring it back, not for them but for their children. That is how NACWOLA (National Community of Women Living with HIV/AIDS) was born, during the International Conference on AIDS held in Amsterdam in 1992. The three founding members died of AIDS during the following years, but their legacy was a ray of light in the darkest days. With the help of European health and psychology professionals, the decided to put in writing what they would never be able to tell their children, and they created the Memory Books. These books are their recollections, they tell us about them and the future they want for their children n pages full of words of care and affection. They are motherhood guides from beyond, survival tutorials for lost children, since over 12% of Sub-Saharan underage population will lose at least one of their parents in the next 12 months, and they will be on their own. As Gladys, the person in charge of the Memory Books project in Luwero, the center of the country, tell us: "They are each special and very personal, in spite of following a common pattern that includes family photos, memories and a family tree. With these books we encourage parents to listen to their children, to talk to them frankly about their disease."

The project is like a big family with members helping each other emotionally and financially in their daily struggle for survival. Mothers, orphans and grandmothers, many of them displaced by the internal war with the LRA (Lord's Resistance Army). In a country where 35% of the population is HIV positive, where there are two million orphans, a country in which polygamy and dowry are common practice, these women are struggling against the AIDS stigma and are not afraid of anything. NACWOLA and the project have given them back hope.

*ANHUA is a Chinese term that means what the backlight is only seen. His philosophy rests on a fundamental idea: to "Light" the forgotten. Forgotten for any reason: war, displacement, environmental disaters, threats or violations of human rights. We want to help strengthen communication between associations and NGOs from different geographical areas that have no visible spaces to deliver their work and projects. We see in the documentary reports as a tool to approach different interpretations of our environment and help to change unjust realities. We firmly believe that creativity applied to new ways and audiovisual communication is essential in order to promote social change to disadvantaged or minority communities, and also we want to spread world awareness of these situations in the Western. Giving voice to those that no one wants to hear from the direct involvement and through witness always sincere, promoting cultural, educational and social action.

Alvaro Laiz (León, 1981) Master in Visual Arts de Universidad Pontificia de Salamanca. His photographic work focuses on realities that are often forgotten, in areas like Africa, Asia or Southern America. For Laiz, documentary photography is a tool with which he can approach stories that fascinate or worry him, or stories in which he wants to participate from his point of view. With this mindset he co-founded the ONG An-Hua. His work has been published in media like the Sunday Times Magazine, Forbes, British Journal of Photography, National Geographic o New York Times among others.

Alvaro Laiz (León, 1981) Master in Visual Arts de Universidad Pontificia de Salamanca. His photographic work focuses on realities that are often forgotten, in areas like Africa, Asia or Southern America. For Laiz, documentary photography is a tool with which he can approach stories that fascinate or worry him, or stories in which he wants to participate from his point of view. With this mindset he co-founded the ONG An-Hua. His work has been published in media like the Sunday Times Magazine, Forbes, British Journal of Photography, National Geographic o New York Times among others. David Rangel (Torreblanca de los Caños, Sevilla. 1978) Photographer and documentary filmmaker. His professional activity is related to the film industry for over 14 years. Co-founder of An-Hua in order to publicize the forgotten conflicts and document the social, historical and contemporary changes. Focused its commitment issues and concerns related to human rights, anthropology, economics and environment.

David Rangel (Torreblanca de los Caños, Sevilla. 1978) Photographer and documentary filmmaker. His professional activity is related to the film industry for over 14 years. Co-founder of An-Hua in order to publicize the forgotten conflicts and document the social, historical and contemporary changes. Focused its commitment issues and concerns related to human rights, anthropology, economics and environment.World Press Photo

World Press Photo helps to nurture the talent and passion of visual journalists who tell stories that can open our eyes and inspire a greater understanding of the world around us. By offering training possibilities and grants to produce stories we strengthen the skills and network of visual journalists in regions where educational opportunities are limited or from where we hardly see stories in the media which are produced by these local visual journalists. Reporting Change was a program in which we focused on North Africa and the visual journalistic community there. The goal was to foster a more authentic, representative portrayal of the region and its people in the wake of the Arab Spring uprisings. When we started the program in 2012 we felt there was a need of training independent visual journalists to tell the world what is going on in their countries and surroundings, from their perspectives, from their eyes.

The two productions, the book and the online interactive experience, Stories of Change celebrates authenticity in visual storytelling. The productions offer a perspective on everyday life in five North African countries through the eyes of a group of visual journalists who were trained by World Press Photo in storytelling skills (both still photography and multimedia). The stories produced cover a wide range of themes and often include those who have been overshadowed by news events. Stories shape information into meaning and are unique and that is what we are facilitating in their creation.

Eefje Ludwig

Manager Education

World Press Photo

|

Amira Fighting for Egyptian Women by Mohamed Hossam |

Zineb Mountain Guide by Abdellah Azizi |

See more stories: storiesofchange.worldpressphoto.org

Mohamed Hossam Eldin was born in Egypt in 1987, and graduated with a BA in journalism from the Akhbar Al-Youm Academy in Cairo in 2008. He works as a photojournalist, and has been with the leading Egyptian daily Al-Masry Al-Youm, in addition to freelancing for AFP. He is with the Anadolu Agency, is a member of the Egyptian Syndicate of Journalists, and is the Egypt coordinator of Photographers for Charity. Eldin has received numerous awards over the past few years, most notably a number of first prizes in the Egypt Press Photo contest.

Mohamed Hossam Eldin was born in Egypt in 1987, and graduated with a BA in journalism from the Akhbar Al-Youm Academy in Cairo in 2008. He works as a photojournalist, and has been with the leading Egyptian daily Al-Masry Al-Youm, in addition to freelancing for AFP. He is with the Anadolu Agency, is a member of the Egyptian Syndicate of Journalists, and is the Egypt coordinator of Photographers for Charity. Eldin has received numerous awards over the past few years, most notably a number of first prizes in the Egypt Press Photo contest. Abdellah Azizi was born in Morocco in 1987, and studied cinematographic lighting techniques at a specialized college in his hometown of Ouarzazate. After further film and editing studies in Casablanca, he worked as camera and lighting assistant on several productions. He now works for a local e-magazine, almaouja.com

Abdellah Azizi was born in Morocco in 1987, and studied cinematographic lighting techniques at a specialized college in his hometown of Ouarzazate. After further film and editing studies in Casablanca, he worked as camera and lighting assistant on several productions. He now works for a local e-magazine, almaouja.comWorld Press Photo helps to nurture the talent and passion of visual journalists who tell stories that can open our eyes and inspire a greater understanding of the world around us. By offering training possibilities and grants to produce stories we strengthen the skills and network of visual journalists in regions where educational opportunities are limited or from where we hardly see stories in the media which are produced by these local visual journalists. Reporting Change was a program in which we focused on North Africa and the visual journalistic community there. The goal was to foster a more authentic, representative portrayal of the region and its people in the wake of the Arab Spring uprisings. When we started the program in 2012 we felt there was a need of training independent visual journalists to tell the world what is going on in their countries and surroundings, from their perspectives, from their eyes.

The two productions, the book and the online interactive experience, Stories of Change celebrates authenticity in visual storytelling. The productions offer a perspective on everyday life in five North African countries through the eyes of a group of visual journalists who were trained by World Press Photo in storytelling skills (both still photography and multimedia). The stories produced cover a wide range of themes and often include those who have been overshadowed by news events. Stories shape information into meaning and are unique and that is what we are facilitating in their creation.

Eefje Ludwig

Manager Education

World Press Photo

|

Amira Fighting for Egyptian Women by Mohamed Hossam |

Zineb Mountain Guide by Abdellah Azizi |

See more stories: storiesofchange.worldpressphoto.org

Mohamed Hossam Eldin was born in Egypt in 1987, and graduated with a BA in journalism from the Akhbar Al-Youm Academy in Cairo in 2008. He works as a photojournalist, and has been with the leading Egyptian daily Al-Masry Al-Youm, in addition to freelancing for AFP. He is with the Anadolu Agency, is a member of the Egyptian Syndicate of Journalists, and is the Egypt coordinator of Photographers for Charity. Eldin has received numerous awards over the past few years, most notably a number of first prizes in the Egypt Press Photo contest.

Mohamed Hossam Eldin was born in Egypt in 1987, and graduated with a BA in journalism from the Akhbar Al-Youm Academy in Cairo in 2008. He works as a photojournalist, and has been with the leading Egyptian daily Al-Masry Al-Youm, in addition to freelancing for AFP. He is with the Anadolu Agency, is a member of the Egyptian Syndicate of Journalists, and is the Egypt coordinator of Photographers for Charity. Eldin has received numerous awards over the past few years, most notably a number of first prizes in the Egypt Press Photo contest. Abdellah Azizi was born in Morocco in 1987, and studied cinematographic lighting techniques at a specialized college in his hometown of Ouarzazate. After further film and editing studies in Casablanca, he worked as camera and lighting assistant on several productions. He now works for a local e-magazine, almaouja.com

Abdellah Azizi was born in Morocco in 1987, and studied cinematographic lighting techniques at a specialized college in his hometown of Ouarzazate. After further film and editing studies in Casablanca, he worked as camera and lighting assistant on several productions. He now works for a local e-magazine, almaouja.comMatthew Hashiguchi

Good Luck Soup

Good Luck SoupIs a transmedia storytelling project documenting and sharing stories of the Japanese American and Japanese Canadian experience after they left the internment camps. The project consists of a feature-length documentary film, titled Good Luck Soup and an interactive, participatory website, Good Luck Soup Interactive. On this website stories will be told through uploaded text and photographs from internment camp victims, or their families, and will be shared through an interactive website and map.

People Aren't All Bad

People Aren't All BadZZ. What has been the reaction of the public to your invitation to participate in your transmedia storytelling project?

MH. We've had a consistently positive response from the Japanese American/Canadian community. Initially, I think many have been nervous about sharing their own stories and experiences, but once we sit down with them and talk about their life, they tend to open up. It's been a form of catharsis, I think, because many people have never discussed their issues or experiences of being Japanese American/Canadian... and some of these things are very difficult topics or thoughts that have been bottled up. So, it's a very emotional experience to share these thoughts and feelings. We haven't yet opened it up to the general public, but again, everyone has been consistently positive, and I have no reason to think the reaction will be any different once its available to all Japanese Americans and Japanese Canadians.

ZZ. What means of publicity are you using or are you planning to use for the diffusion of the project?

MH. Social media will be a huge tool for publicity and marketing. We've already reached and met so many people through Twitter and Facebook, and we'll certainly continue to utilize those outlets. We've been in communication with many Asian American and Asian Canadian organizations that have offered their support once the project is complete, and the opportunity to collaborate with entities such as the Japanese American Citizens League, the Japanese American National Museum and the Nikkei National Museum would be priceless. We're certainly inspired by their mission and view our project as a continuation of what they offer the public.

In addition to the interactive documentary, this project also includes a feature length film. Film festivals will be another great opportunity to screen the film and present the interactive project to an audience.

ZZ. Can you share with us how you have experienced the realisation, dissemination and the reach of the project thus far?

MH. It's been a very gradual and collaborative process, and luckily I have an incredible team of colleagues and friends that have made the realization of this project possible, and without their help, I would not have been able to get this project made. The work load is split up fairly well. Right now, our web-designer/coder (Russell Goldenberg) is building the site. He's the one sitting alone typing away at his computer. Every few weeks, we'll all have a meeting where we discuss the direction of the project... and then Russell goes and brings it to life. Billy Wirasnik, Emily Ferrier and myself and have been in charge of content aggregation. So we're narrowing the aim of the stories and in many cases, going out and finding those stories and individuals. It's a solid collaboration made up of various creative visions, rather than one. And, as the Project Creator, I really enjoy a hands-off approach that allows individuals to run off with an idea and make it their own.

Matthew Hashiguchi (1984). Based in Boston, Massachusetts. After graduating from The Ohio State University in 2007 with a BA in Photojournalism, Matthew went on to work and intern as a multimedia journalist for The Findlay Courier, The Lima News and The Washington Post. In 2008, he returned to school and graduated from Emerson College with an MFA in Visual and Media Art and has since been working as an independent documentary filmmaker and educator, whose work focuses on the diverse cultural, social and ethnic stories of American society. For his film The Lower 9 he has received various awards.

Matthew Hashiguchi (1984). Based in Boston, Massachusetts. After graduating from The Ohio State University in 2007 with a BA in Photojournalism, Matthew went on to work and intern as a multimedia journalist for The Findlay Courier, The Lima News and The Washington Post. In 2008, he returned to school and graduated from Emerson College with an MFA in Visual and Media Art and has since been working as an independent documentary filmmaker and educator, whose work focuses on the diverse cultural, social and ethnic stories of American society. For his film The Lower 9 he has received various awards. Good Luck Soup

Good Luck SoupIs a transmedia storytelling project documenting and sharing stories of the Japanese American and Japanese Canadian experience after they left the internment camps. The project consists of a feature-length documentary film, titled Good Luck Soup and an interactive, participatory website, Good Luck Soup Interactive. On this website stories will be told through uploaded text and photographs from internment camp victims, or their families, and will be shared through an interactive website and map.

People Aren't All Bad

People Aren't All BadZZ. What has been the reaction of the public to your invitation to participate in your transmedia storytelling project?

MH. We've had a consistently positive response from the Japanese American/Canadian community. Initially, I think many have been nervous about sharing their own stories and experiences, but once we sit down with them and talk about their life, they tend to open up. It's been a form of catharsis, I think, because many people have never discussed their issues or experiences of being Japanese American/Canadian... and some of these things are very difficult topics or thoughts that have been bottled up. So, it's a very emotional experience to share these thoughts and feelings. We haven't yet opened it up to the general public, but again, everyone has been consistently positive, and I have no reason to think the reaction will be any different once its available to all Japanese Americans and Japanese Canadians.

ZZ. What means of publicity are you using or are you planning to use for the diffusion of the project?

MH. Social media will be a huge tool for publicity and marketing. We've already reached and met so many people through Twitter and Facebook, and we'll certainly continue to utilize those outlets. We've been in communication with many Asian American and Asian Canadian organizations that have offered their support once the project is complete, and the opportunity to collaborate with entities such as the Japanese American Citizens League, the Japanese American National Museum and the Nikkei National Museum would be priceless. We're certainly inspired by their mission and view our project as a continuation of what they offer the public.

In addition to the interactive documentary, this project also includes a feature length film. Film festivals will be another great opportunity to screen the film and present the interactive project to an audience.

ZZ. Can you share with us how you have experienced the realisation, dissemination and the reach of the project thus far?

MH. It's been a very gradual and collaborative process, and luckily I have an incredible team of colleagues and friends that have made the realization of this project possible, and without their help, I would not have been able to get this project made. The work load is split up fairly well. Right now, our web-designer/coder (Russell Goldenberg) is building the site. He's the one sitting alone typing away at his computer. Every few weeks, we'll all have a meeting where we discuss the direction of the project... and then Russell goes and brings it to life. Billy Wirasnik, Emily Ferrier and myself and have been in charge of content aggregation. So we're narrowing the aim of the stories and in many cases, going out and finding those stories and individuals. It's a solid collaboration made up of various creative visions, rather than one. And, as the Project Creator, I really enjoy a hands-off approach that allows individuals to run off with an idea and make it their own.

Matthew Hashiguchi (1984). Based in Boston, Massachusetts. After graduating from The Ohio State University in 2007 with a BA in Photojournalism, Matthew went on to work and intern as a multimedia journalist for The Findlay Courier, The Lima News and The Washington Post. In 2008, he returned to school and graduated from Emerson College with an MFA in Visual and Media Art and has since been working as an independent documentary filmmaker and educator, whose work focuses on the diverse cultural, social and ethnic stories of American society. For his film The Lower 9 he has received various awards.

Matthew Hashiguchi (1984). Based in Boston, Massachusetts. After graduating from The Ohio State University in 2007 with a BA in Photojournalism, Matthew went on to work and intern as a multimedia journalist for The Findlay Courier, The Lima News and The Washington Post. In 2008, he returned to school and graduated from Emerson College with an MFA in Visual and Media Art and has since been working as an independent documentary filmmaker and educator, whose work focuses on the diverse cultural, social and ethnic stories of American society. For his film The Lower 9 he has received various awards.Ehekatl Hernández

There are usually few short films that move away from artificial, cloying stories that at best elicit indifference and trivialize the issue. Even less frequently do we see work that paradoxically does not try to take the easy route, such as the excessive use of visual puns, flashbacks or complex leaps through time to turn it around. At some point, the way stories are told became, on the one hand, complex, foreign and undecipherable, or banal, Manichaean and predictable on the other. In both cases, the message is lost along with any authentic relationship with the viewer.

This is why it is difficult to find work, amidst the maelstrom of films, which is an exception to the rule; I travel because I need to, I return because I love you is one such example. Produced in 2009 by the Brazilian pair Karim Ainouz /Marcelo Gomes, it is a modest piece that uses cinematographic and photographic resources in an exceptional way, giving life to an entirely fresh, direct and human narrative that fluctuates between the genres of Road movies and Storytelling. I travel because I need to, I return because I love you is José Renato’s travel log. Renato was a 35-year-old Brazilian geologist commissioned to build a canal in the Northeast of Brazil. As his fieldwork advances, it becomes clear that Renato shares the emptiness of these places, the same feeling of isolation and abandonment. Thus a parallel inner search begins that is constantly reflected in the landscape of Brazilian plains. The geographic description is not limited to the countryside or the terrain through which he travels; it also describes the people he encounters along the way, so that feelings and passions are also included in his inner travel log.

The use of audiovisual language is outstanding at all times: stills and small sequences recorded on super8, DVCAMs and Hi8 are complemented by photographs, archival images, incidental sound and the occasional, well-chosen track without neglecting the rhythmic, first person voice over (Irandhir Santos). It is a type of inner monologue designed to achieve an honest, naked, personal reflection that addresses misunderstandings between lovers, existential emptiness and solitude. The reflections are occasionally interrupted by the testimonials of those with whom the protagonist exchanges words and experiences, returning the viewer subtly to the documentary genre.

Thus all the elements that make up this piece, running no longer the 75 minutes, become a reel across which clear, honest narrative flows, whose lyricism that alludes to the universal themes of love, innocence, solitude and hope.

In short, I travel because I need to, I return because I love you is a well-rounded piece that could not have been conceived without such a close link between image and narrative. It is a clear example of the explorations and boundaries through which what some people have called photo narrative, can freely flow.

“I travel because I need to, I return because I love you.” Brazil 2009. Director and writer: Karim Ainouz and Marcelo Gomes. Photography: Heloísa Passos. Music Chambarti. Actor: Irandhir Santos. Length: 75 minutes.

Ehekatl Hernández (México, 1975).received a Bachelor’s Degree in Graphic Design from the Escuela Nacional de Artes Plásticas at UNAM in Mexico, and a Master’s Degree in Multimedia Applications from the Universidad Poltécnica de Catalunya in Spain. He has over 15 years’ experience in graphic design and planning, developing and implementing web projects. Hernández has given diploma courses in web design at UNAM. He has spent nine years contributing to the web design and multimedia area at zonezero.com, and also works as a consultant for various companies as well as coordinating the e-learning system of the Virtual Campus of the Pedro Meyer Foundation.

Ehekatl Hernández (México, 1975).received a Bachelor’s Degree in Graphic Design from the Escuela Nacional de Artes Plásticas at UNAM in Mexico, and a Master’s Degree in Multimedia Applications from the Universidad Poltécnica de Catalunya in Spain. He has over 15 years’ experience in graphic design and planning, developing and implementing web projects. Hernández has given diploma courses in web design at UNAM. He has spent nine years contributing to the web design and multimedia area at zonezero.com, and also works as a consultant for various companies as well as coordinating the e-learning system of the Virtual Campus of the Pedro Meyer Foundation.There are usually few short films that move away from artificial, cloying stories that at best elicit indifference and trivialize the issue. Even less frequently do we see work that paradoxically does not try to take the easy route, such as the excessive use of visual puns, flashbacks or complex leaps through time to turn it around. At some point, the way stories are told became, on the one hand, complex, foreign and undecipherable, or banal, Manichaean and predictable on the other. In both cases, the message is lost along with any authentic relationship with the viewer.

This is why it is difficult to find work, amidst the maelstrom of films, which is an exception to the rule; I travel because I need to, I return because I love you is one such example. Produced in 2009 by the Brazilian pair Karim Ainouz /Marcelo Gomes, it is a modest piece that uses cinematographic and photographic resources in an exceptional way, giving life to an entirely fresh, direct and human narrative that fluctuates between the genres of Road movies and Storytelling. I travel because I need to, I return because I love you is José Renato’s travel log. Renato was a 35-year-old Brazilian geologist commissioned to build a canal in the Northeast of Brazil. As his fieldwork advances, it becomes clear that Renato shares the emptiness of these places, the same feeling of isolation and abandonment. Thus a parallel inner search begins that is constantly reflected in the landscape of Brazilian plains. The geographic description is not limited to the countryside or the terrain through which he travels; it also describes the people he encounters along the way, so that feelings and passions are also included in his inner travel log.

The use of audiovisual language is outstanding at all times: stills and small sequences recorded on super8, DVCAMs and Hi8 are complemented by photographs, archival images, incidental sound and the occasional, well-chosen track without neglecting the rhythmic, first person voice over (Irandhir Santos). It is a type of inner monologue designed to achieve an honest, naked, personal reflection that addresses misunderstandings between lovers, existential emptiness and solitude. The reflections are occasionally interrupted by the testimonials of those with whom the protagonist exchanges words and experiences, returning the viewer subtly to the documentary genre.

Thus all the elements that make up this piece, running no longer the 75 minutes, become a reel across which clear, honest narrative flows, whose lyricism that alludes to the universal themes of love, innocence, solitude and hope.

In short, I travel because I need to, I return because I love you is a well-rounded piece that could not have been conceived without such a close link between image and narrative. It is a clear example of the explorations and boundaries through which what some people have called photo narrative, can freely flow.

“I travel because I need to, I return because I love you.” Brazil 2009. Director and writer: Karim Ainouz and Marcelo Gomes. Photography: Heloísa Passos. Music Chambarti. Actor: Irandhir Santos. Length: 75 minutes.

Ehekatl Hernández (México, 1975).received a Bachelor’s Degree in Graphic Design from the Escuela Nacional de Artes Plásticas at UNAM in Mexico, and a Master’s Degree in Multimedia Applications from the Universidad Poltécnica de Catalunya in Spain. He has over 15 years’ experience in graphic design and planning, developing and implementing web projects. Hernández has given diploma courses in web design at UNAM. He has spent nine years contributing to the web design and multimedia area at zonezero.com, and also works as a consultant for various companies as well as coordinating the e-learning system of the Virtual Campus of the Pedro Meyer Foundation.

Ehekatl Hernández (México, 1975).received a Bachelor’s Degree in Graphic Design from the Escuela Nacional de Artes Plásticas at UNAM in Mexico, and a Master’s Degree in Multimedia Applications from the Universidad Poltécnica de Catalunya in Spain. He has over 15 years’ experience in graphic design and planning, developing and implementing web projects. Hernández has given diploma courses in web design at UNAM. He has spent nine years contributing to the web design and multimedia area at zonezero.com, and also works as a consultant for various companies as well as coordinating the e-learning system of the Virtual Campus of the Pedro Meyer Foundation.Jan Rosseel

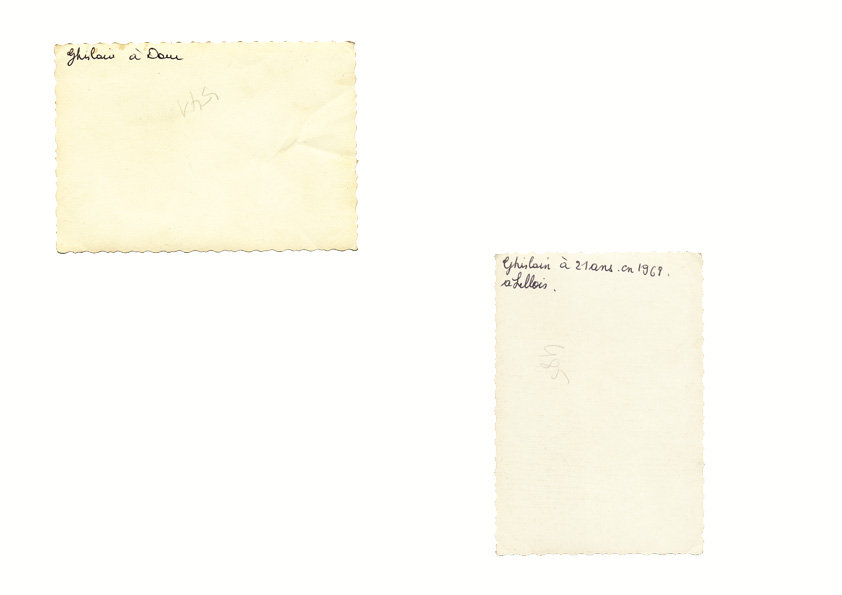

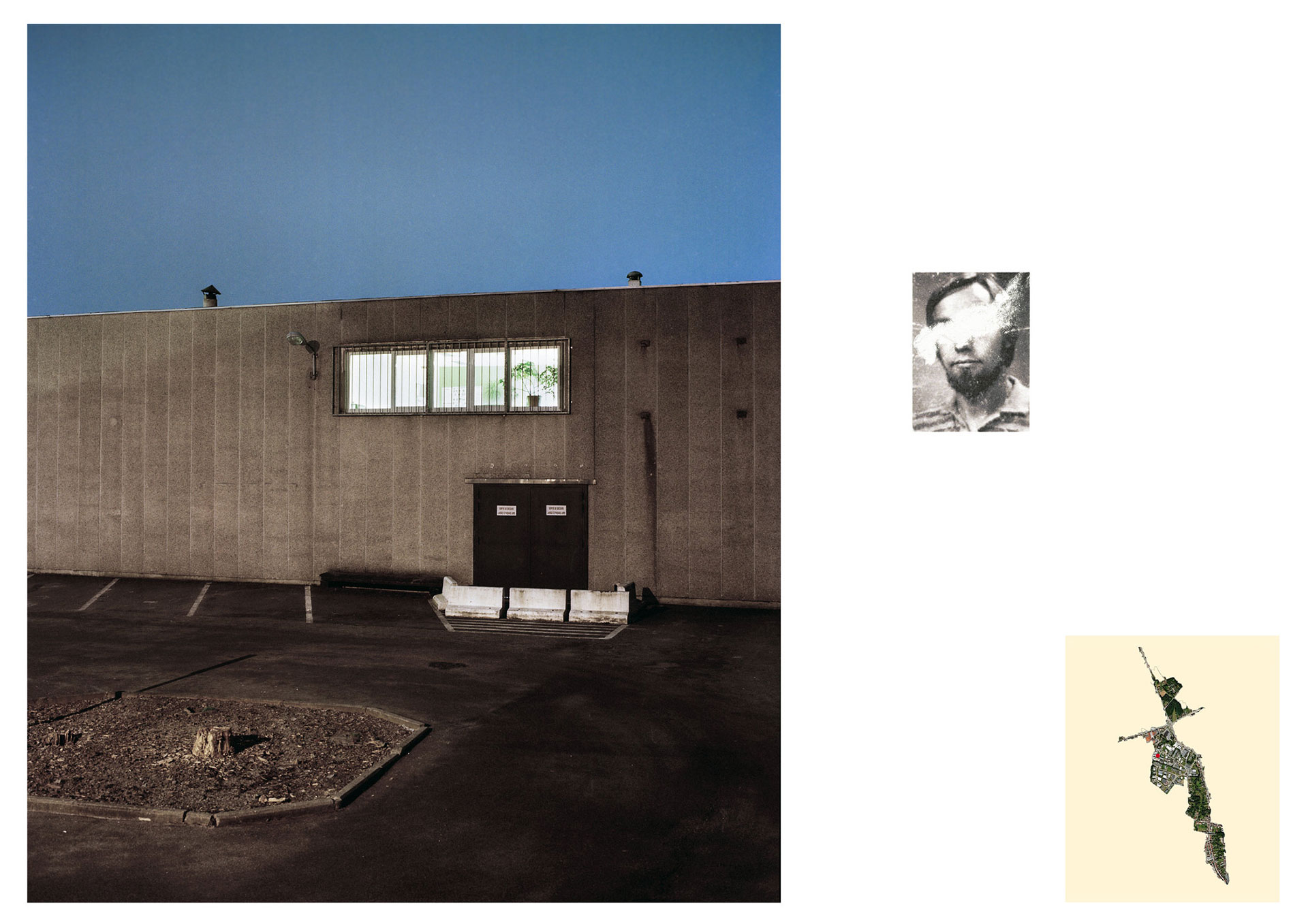

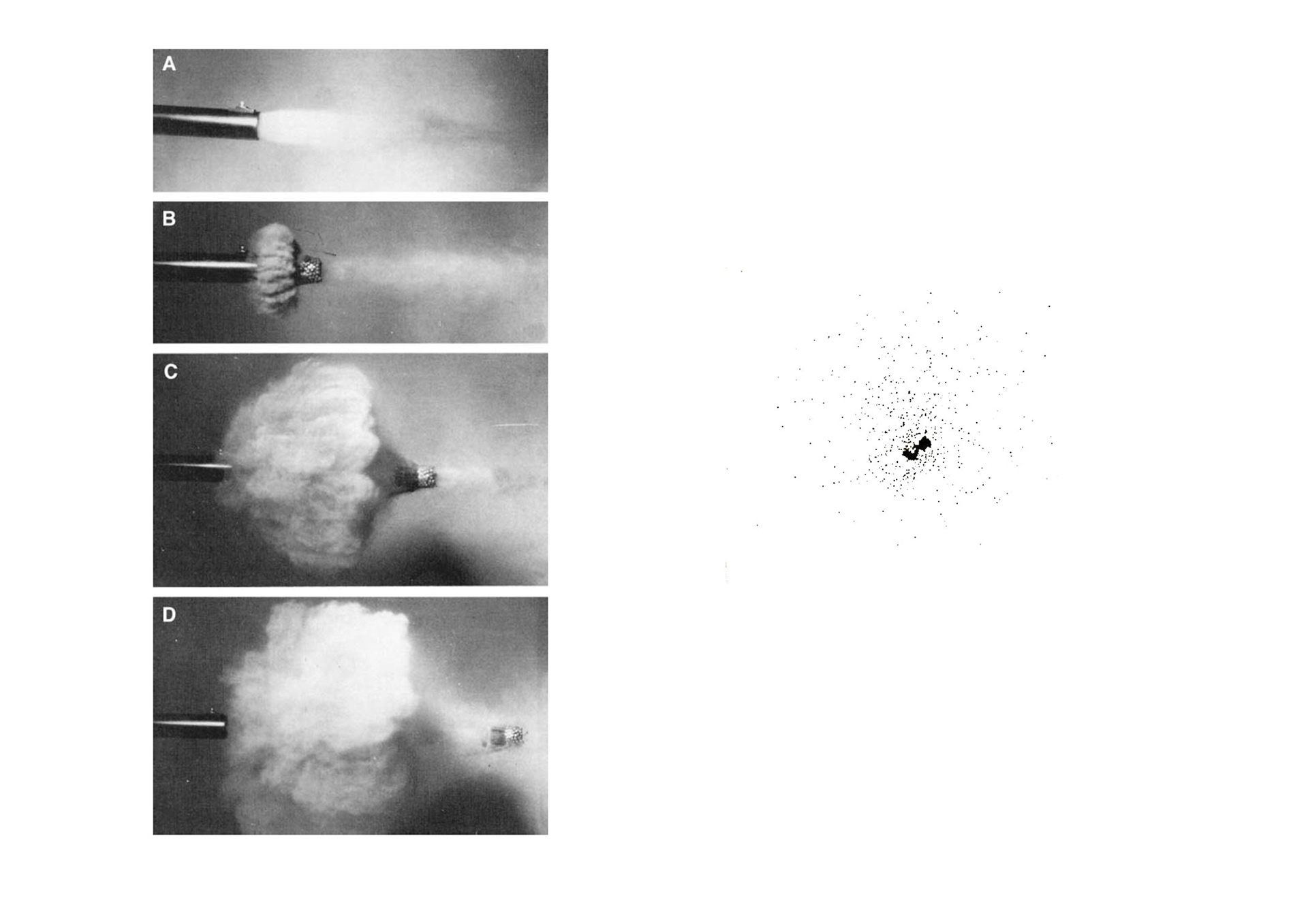

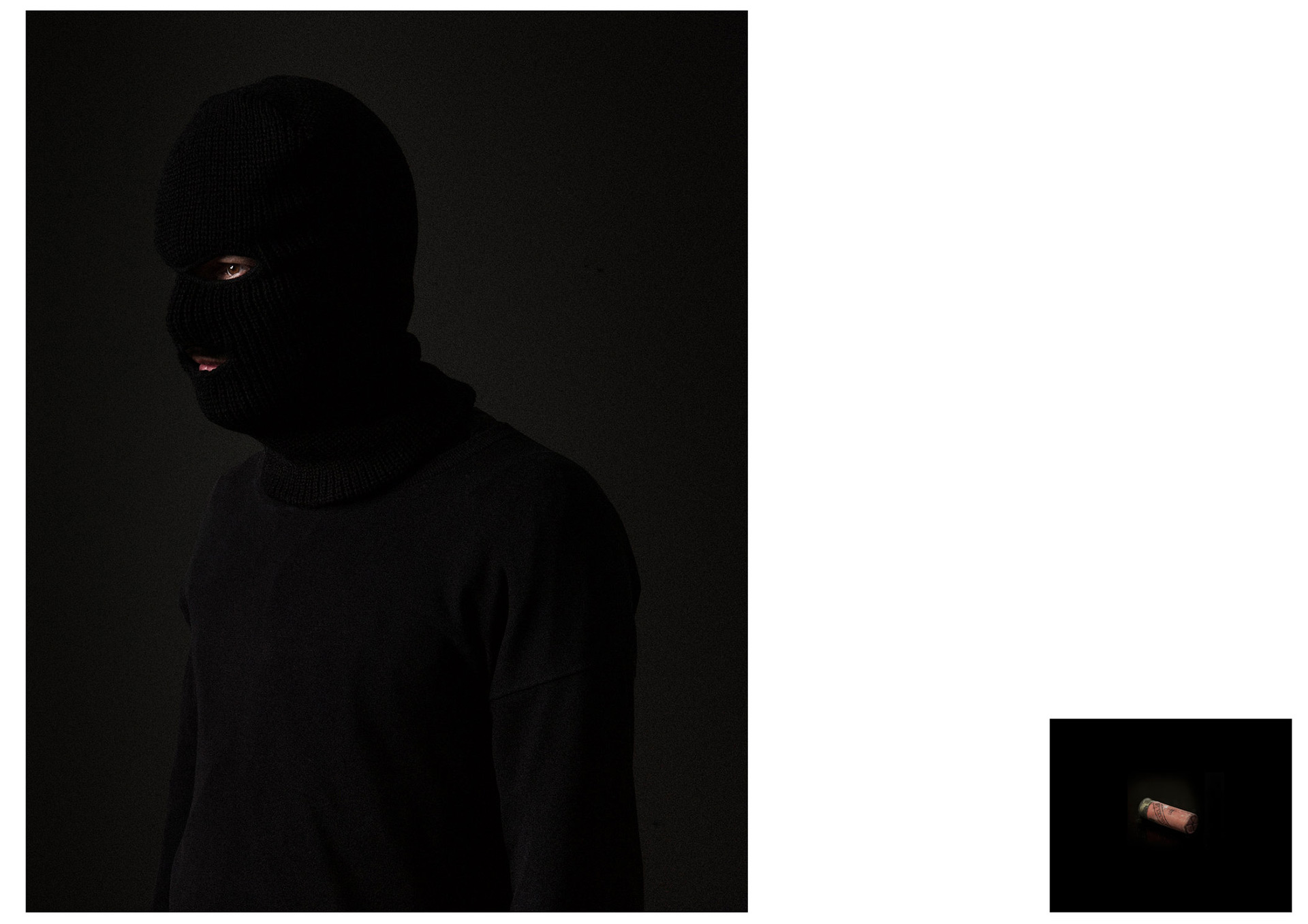

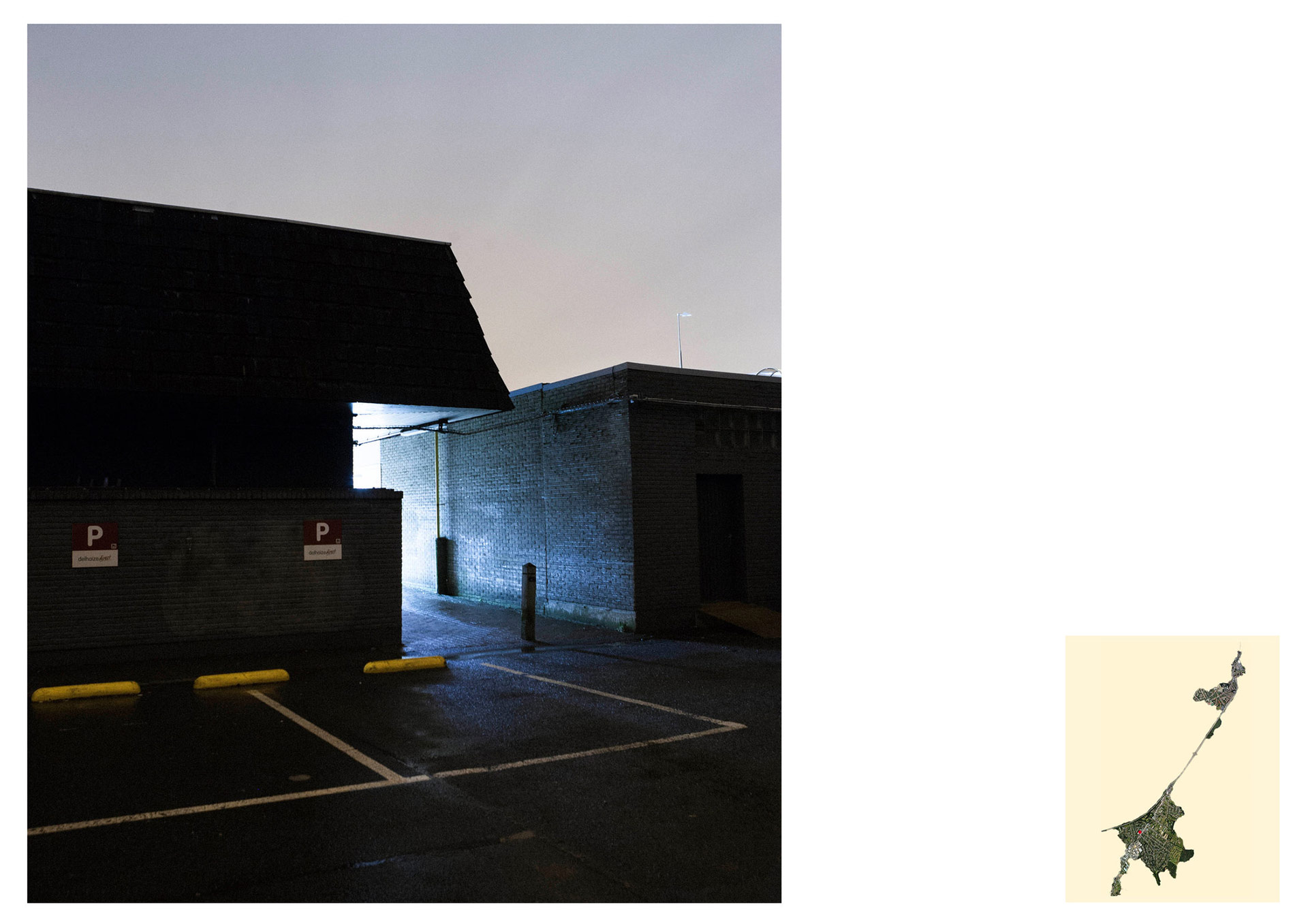

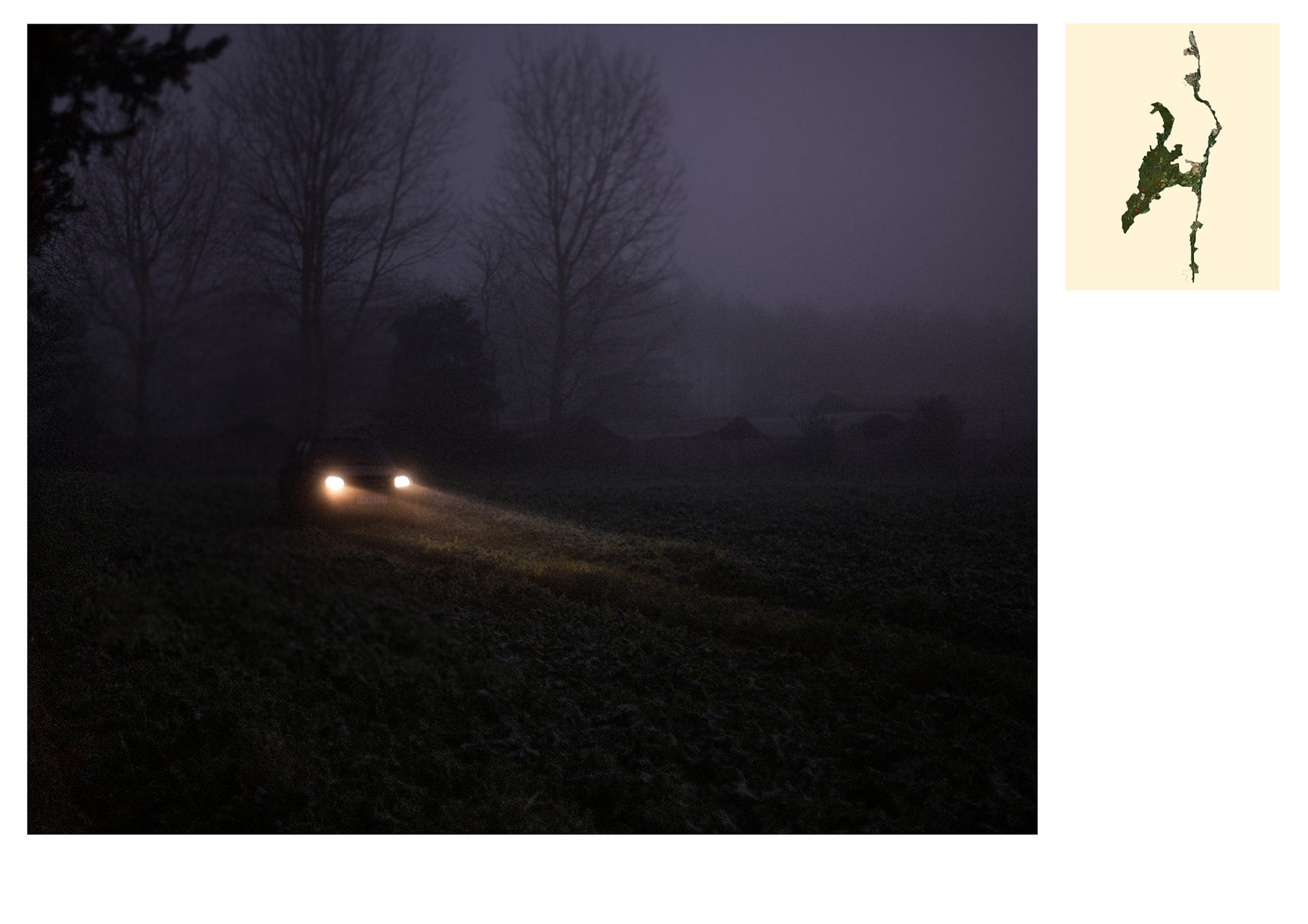

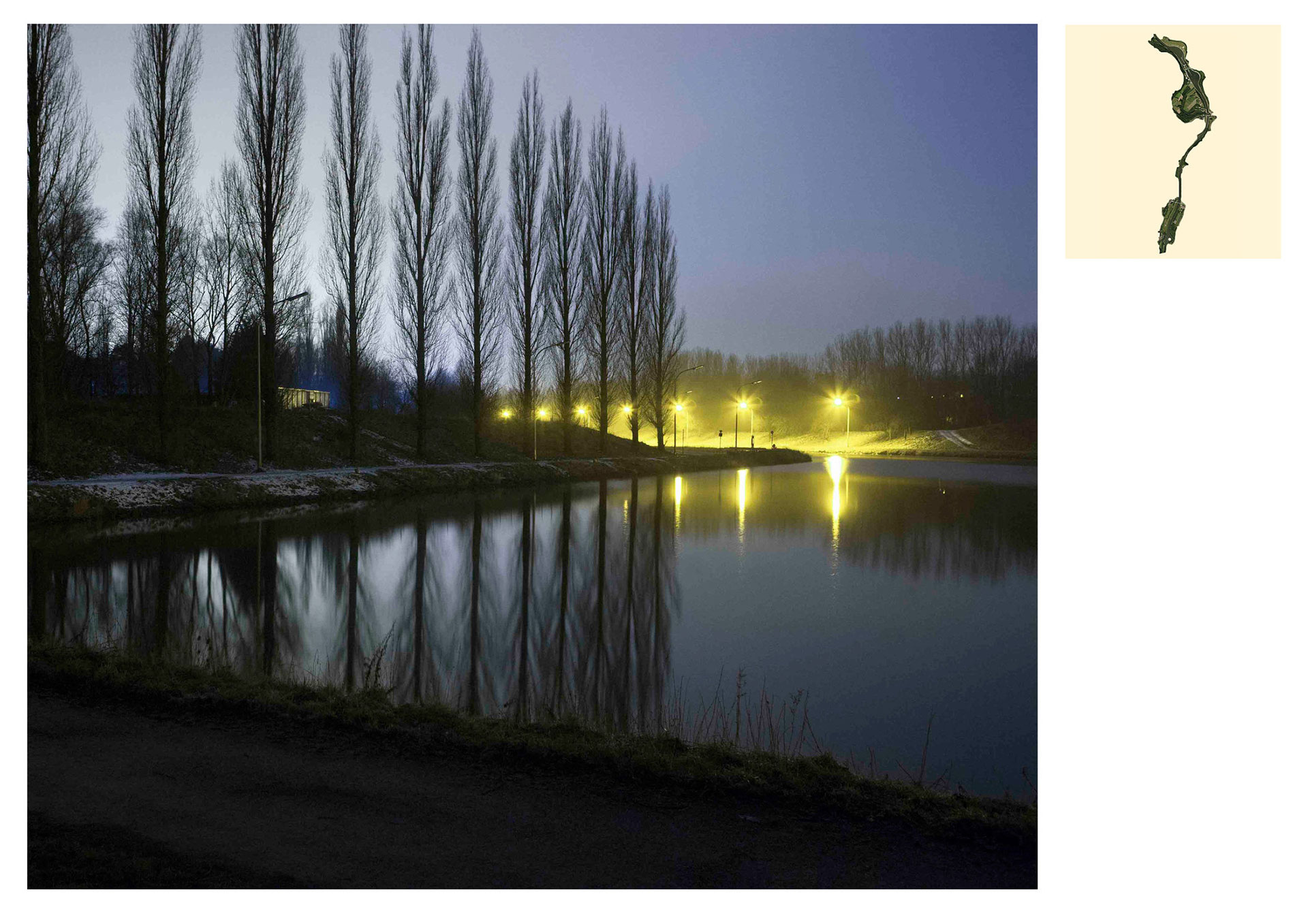

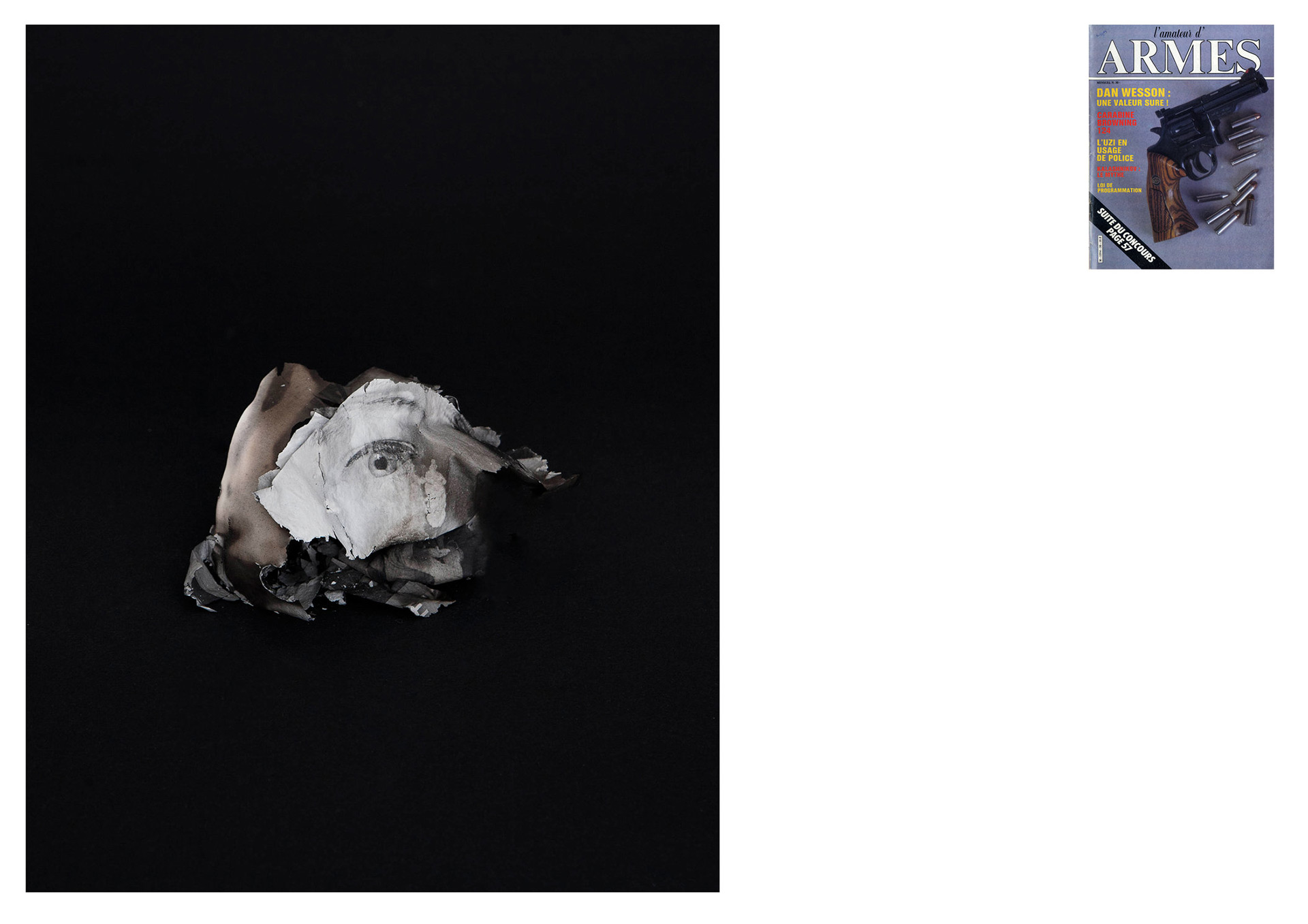

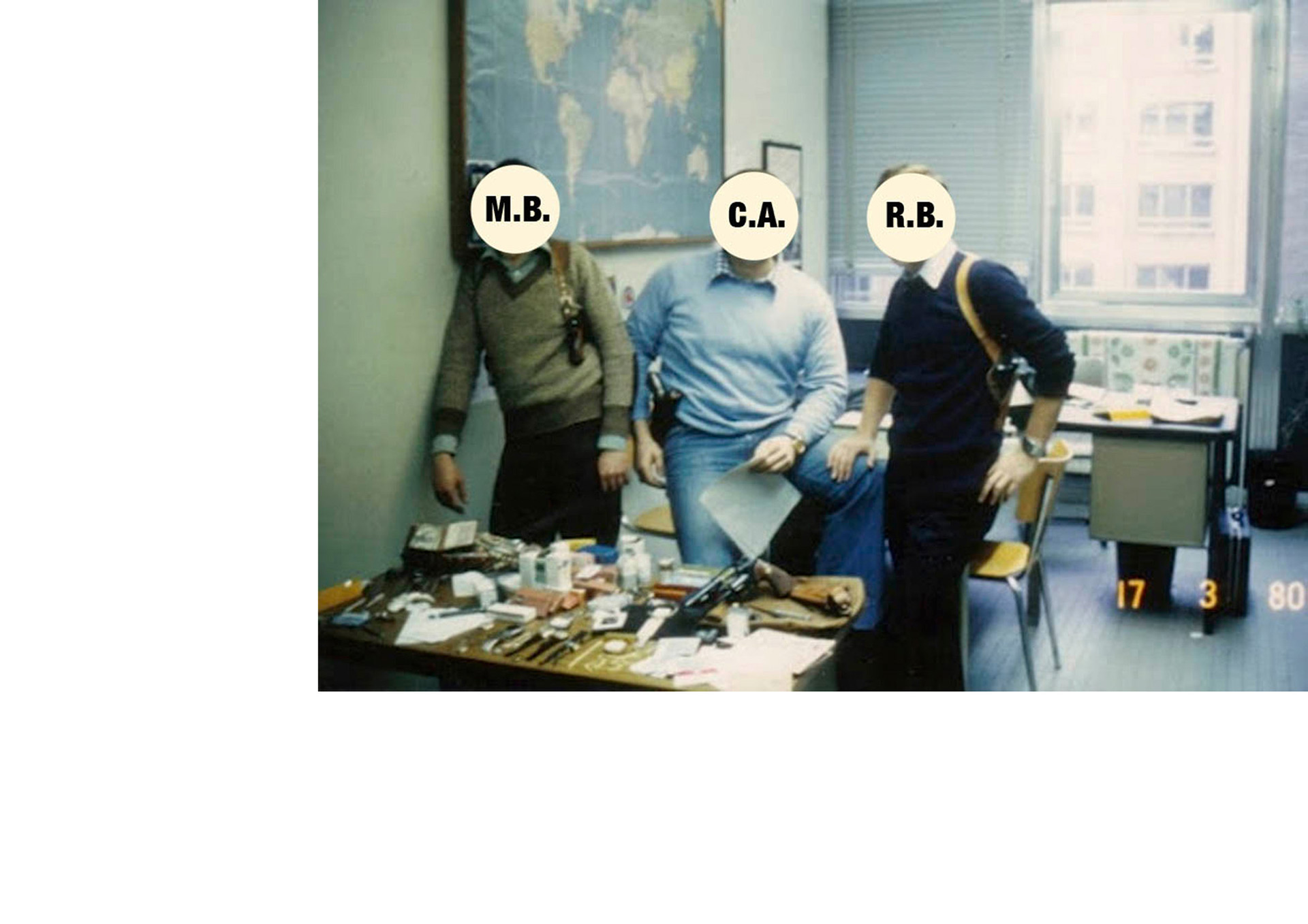

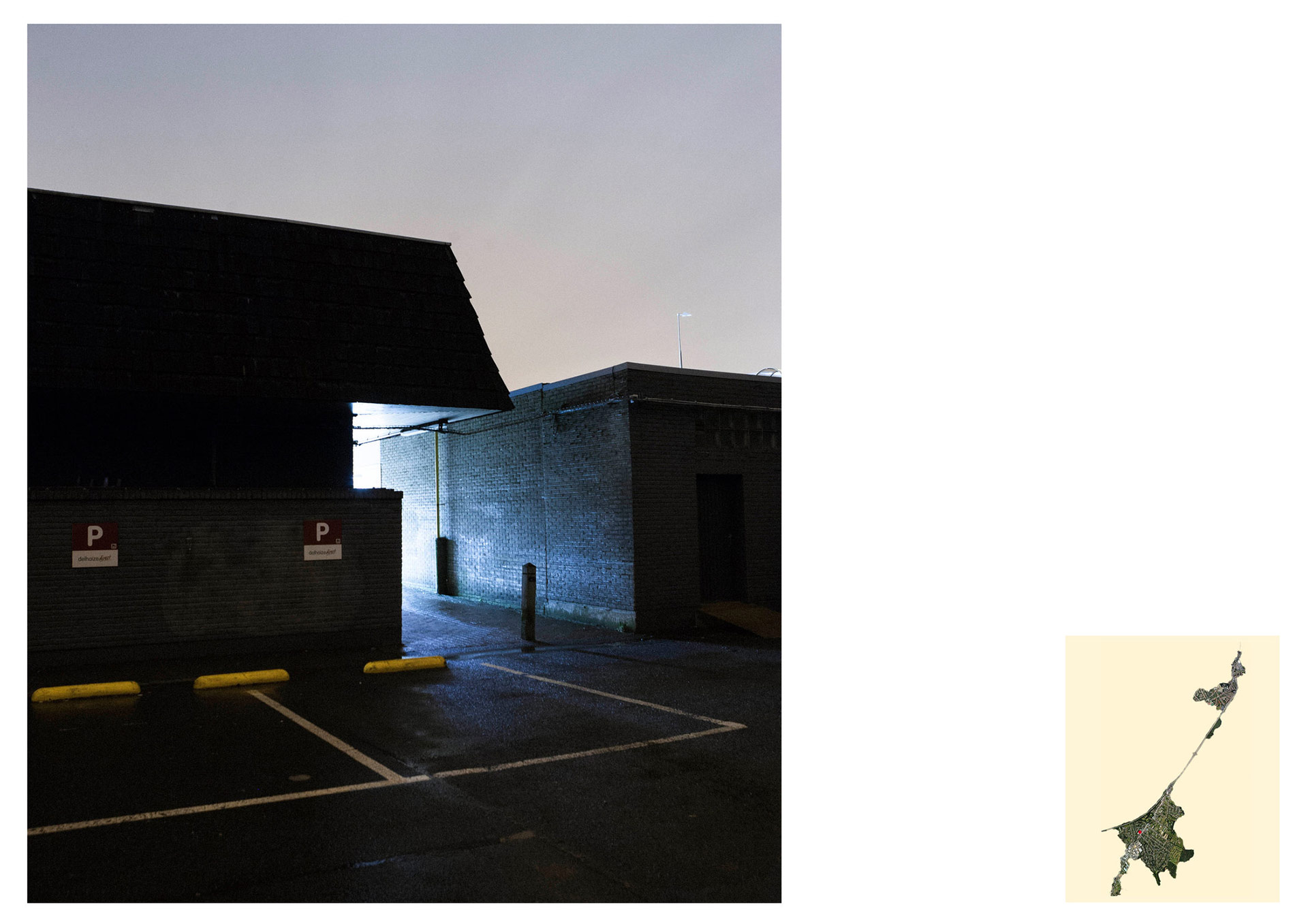

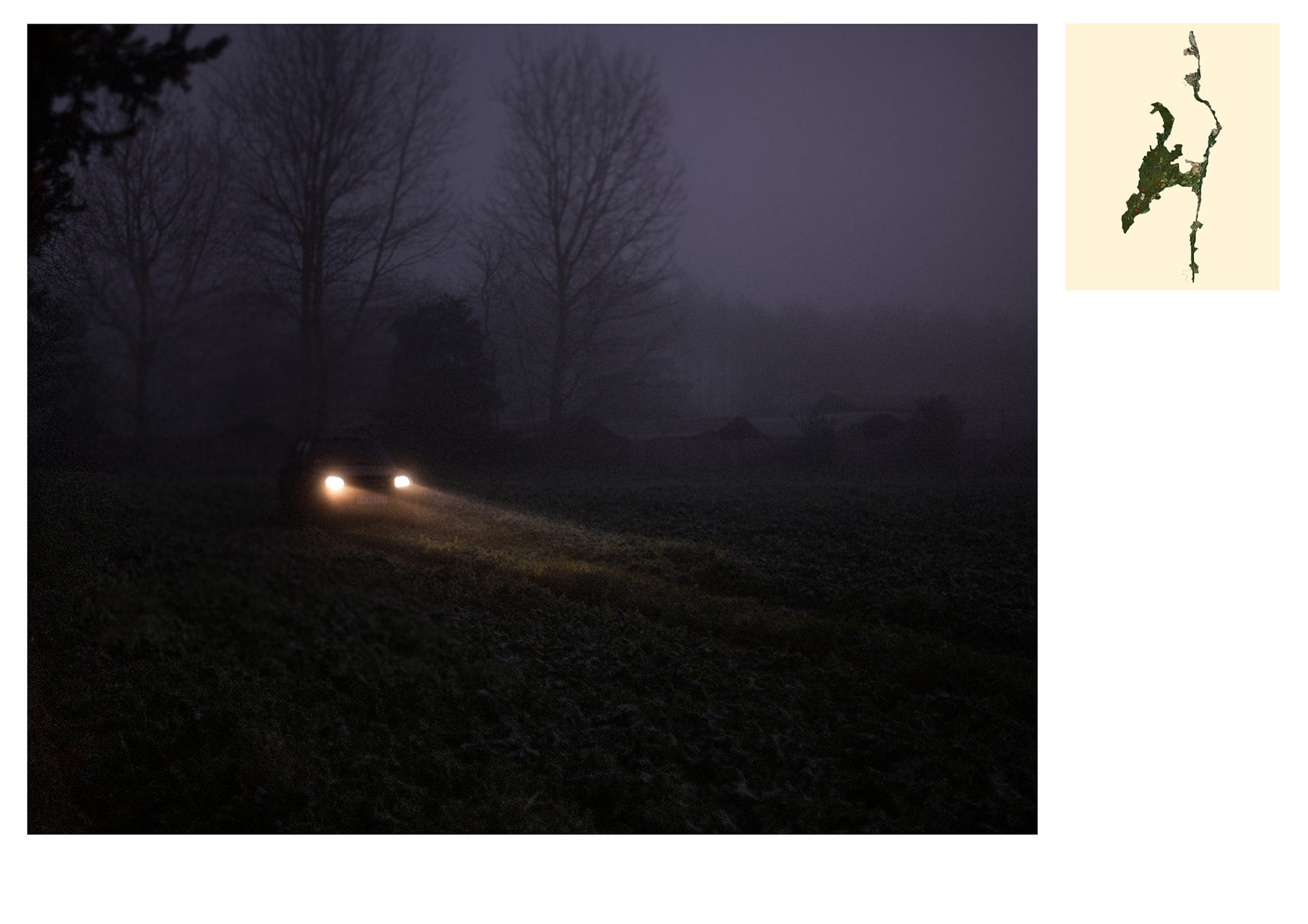

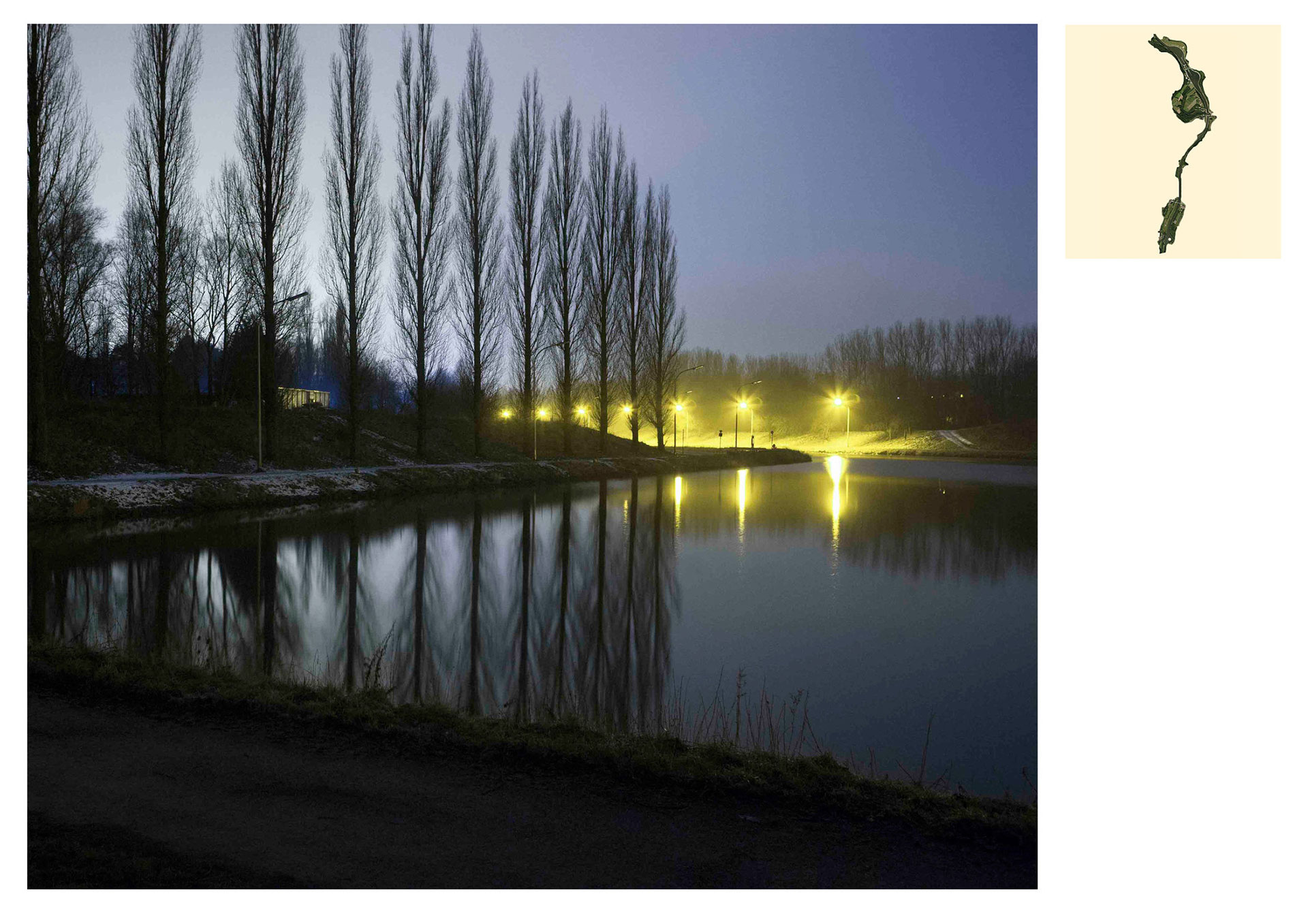

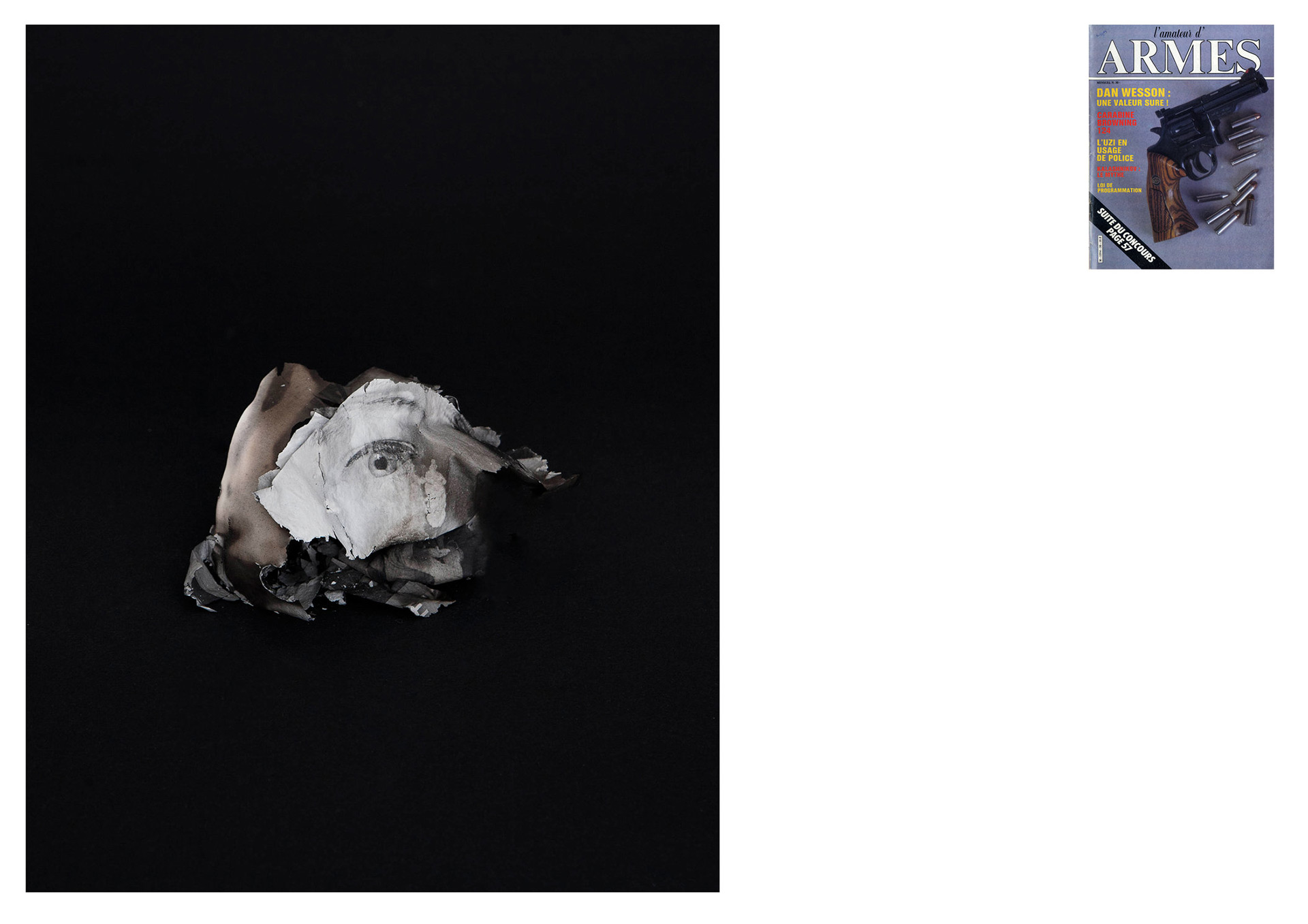

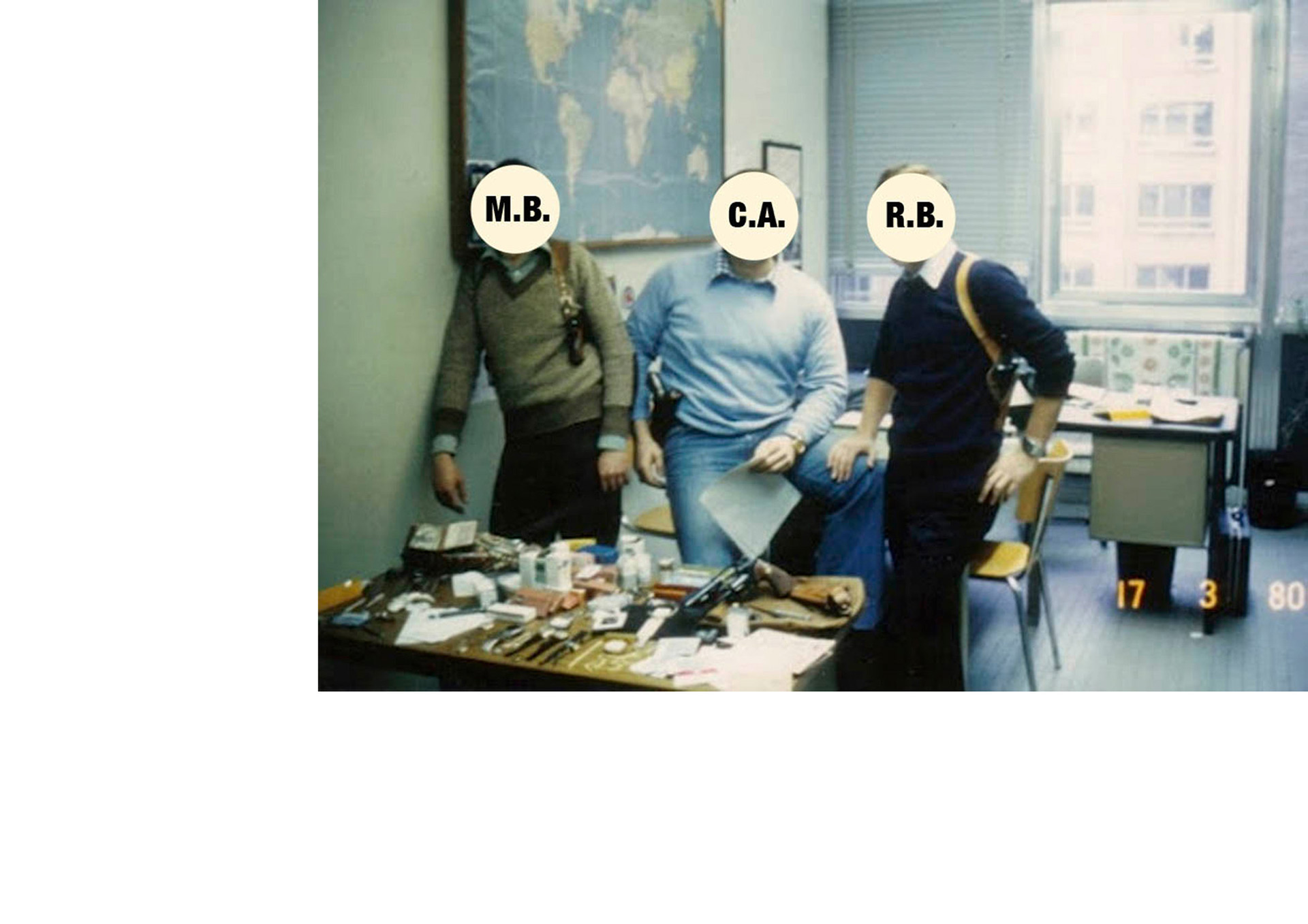

In the autumn of 1985, a series of violent and bloody robberies of Belgian supermarkets abruptly came to an end. A group of unknown criminals, referred to as ´The Gang of Nivelles´, was held responsible for these heinous acts. Between March 1982 and November 1985, the Gang of Nivelles committed twenty-three robberies and other crimes.

In all, twenty-eight people were killed.

My father was one of them.