Eric Kim

Eric Kim, "Debunking the “Myth of the Decisive Moment”", Eric Kim Street Photography Blog , May 23, 2014

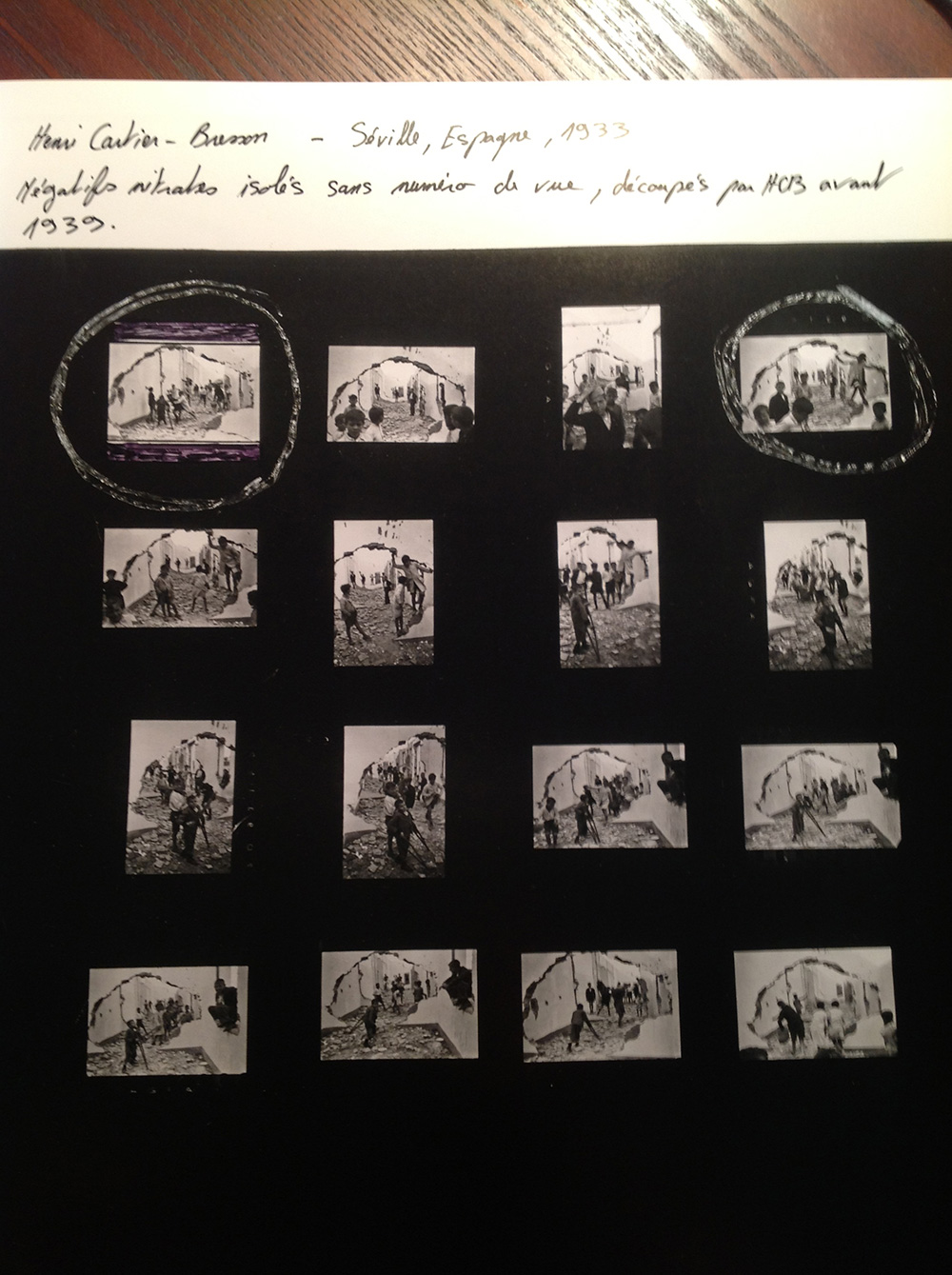

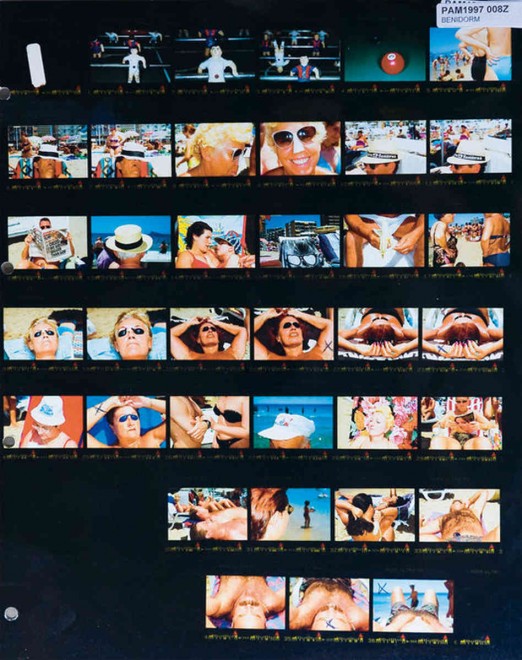

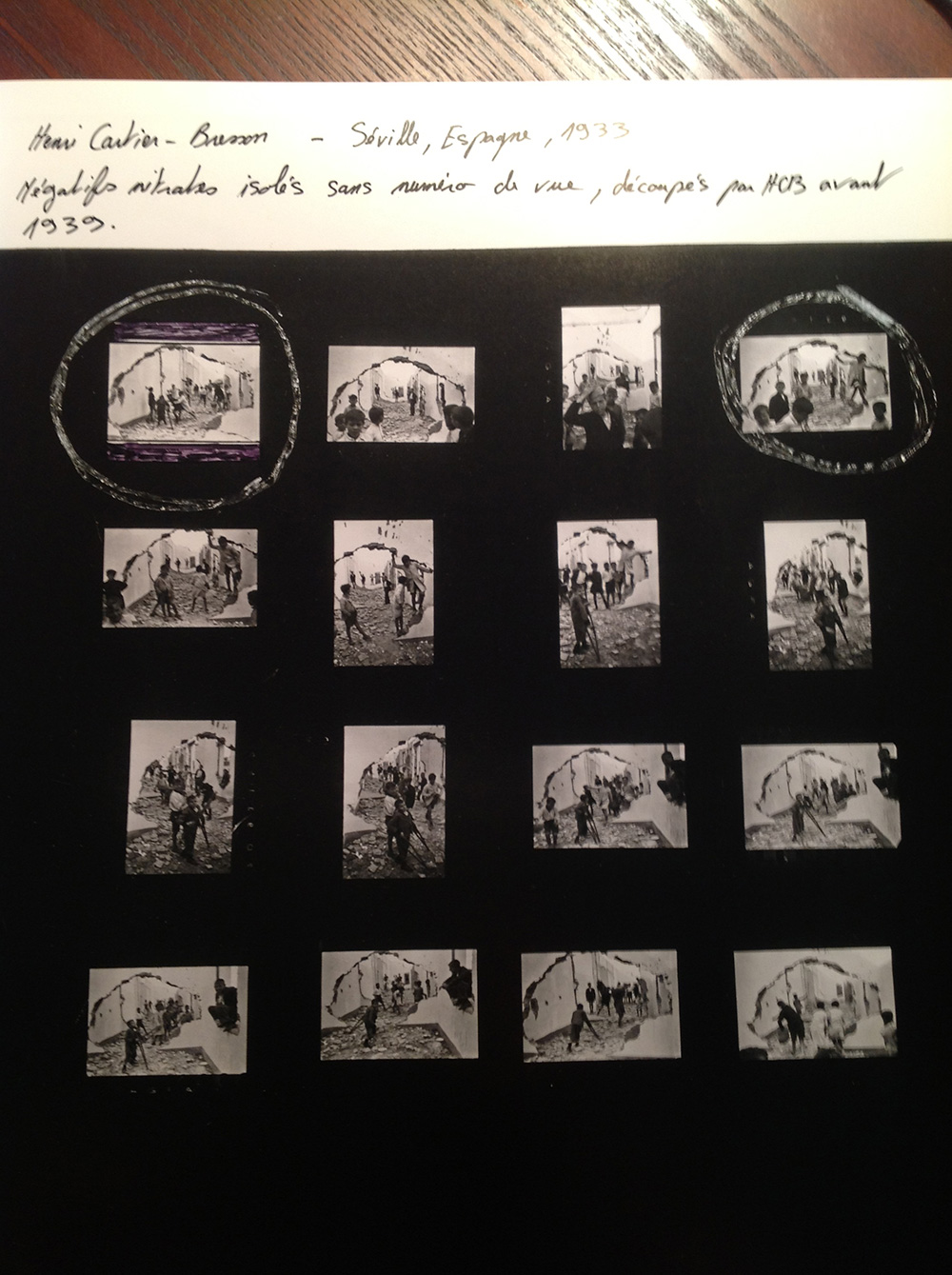

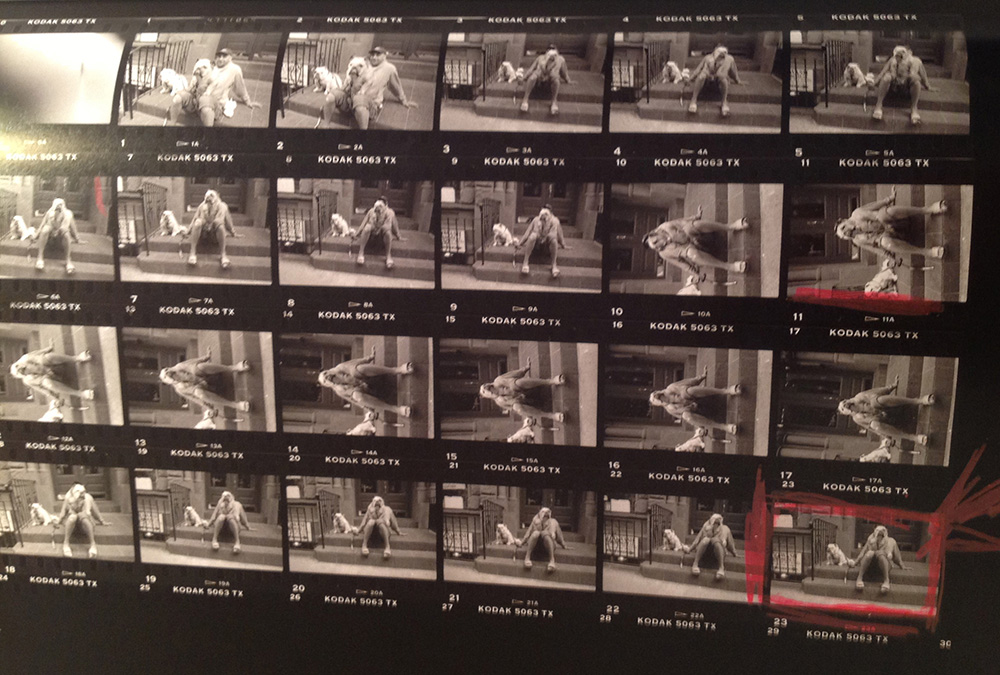

Contact sheet from Henri Cartier-Bresson in Seville, Spain, 1933. © Henri Cartier-Bresson / Magnum Photos

When I started off in street photography, I believed in the “myth of the decisive moment”. What do I mean by that?

Well, when I first heard of “The Decisive Moment” by Henri Cartier Bresson, I had the wrong impression that he only took one photo of a scene. I imagined Henri Cartier Bresson waltzing into a street scene, carefully aiming his Leica, and taking only one shot and creating masterpieces. I thought he was a demigod– a photographer who somehow had this magic behind his lens.

However if we look at his contact sheets, it is a different story. He (and almost all great photographers) never only take one photo of a great potential scene. Out of Henri Cartier Bresson’s contact sheets, you can see that almost all of his great images required him “working the scene”– taking multiple photos of the same scene at different angles, moments, and perspectives. He hustled hard to get the shots he wanted– and would spend considerable time with his contact sheets, determining which photos he decided were his “best”.

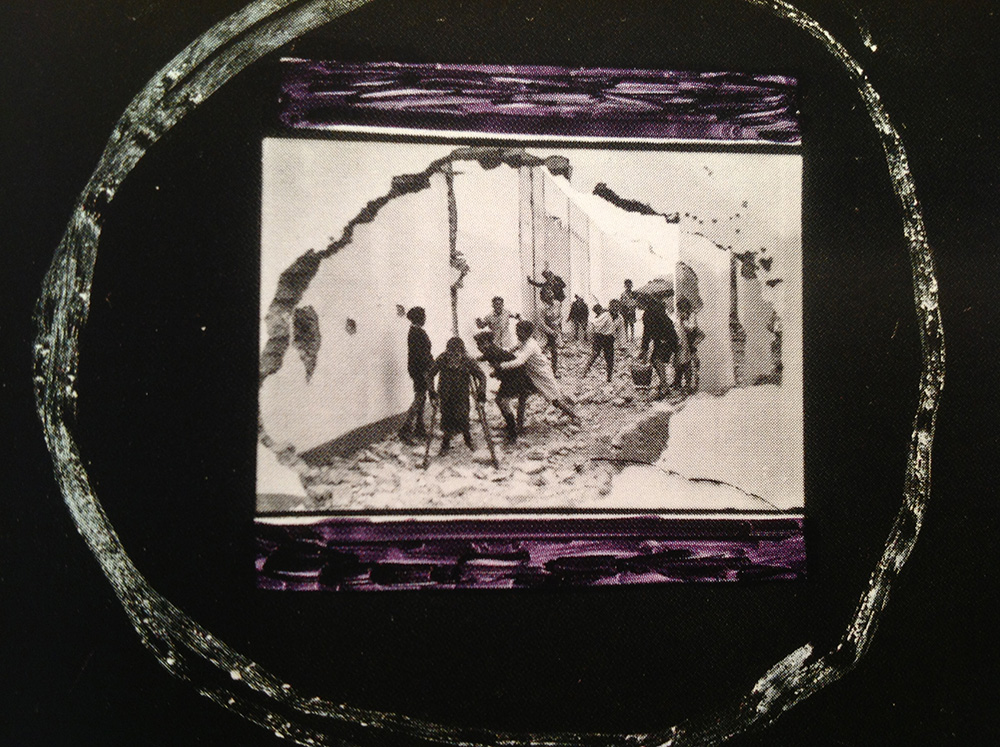

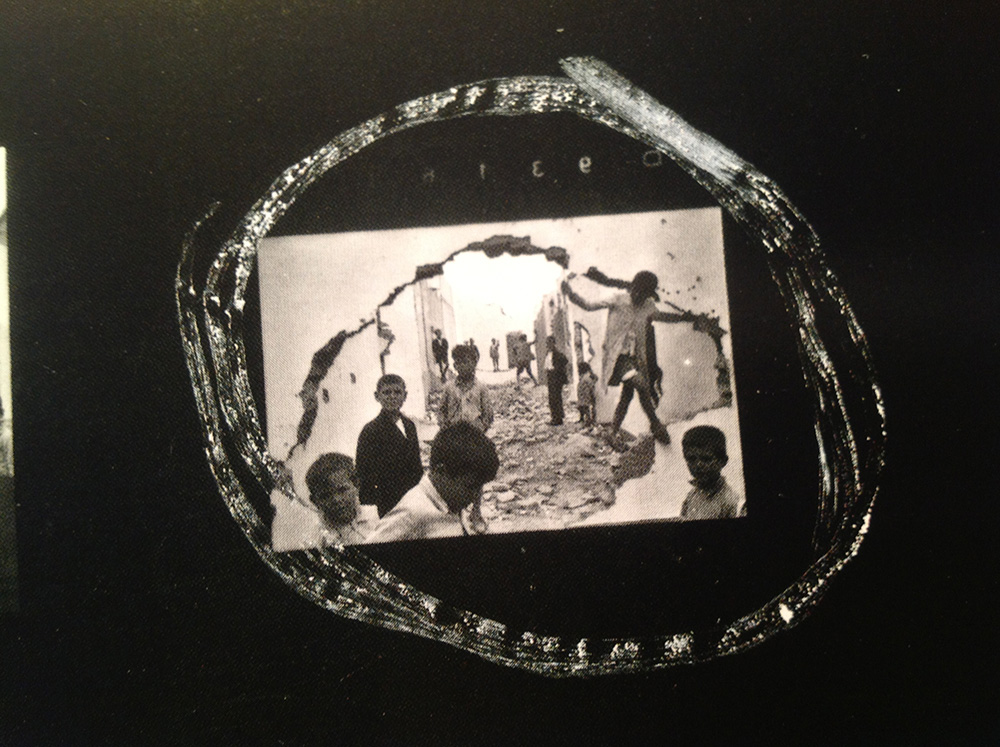

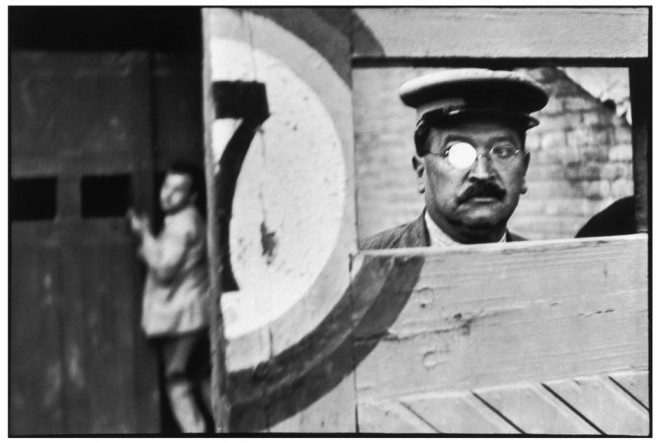

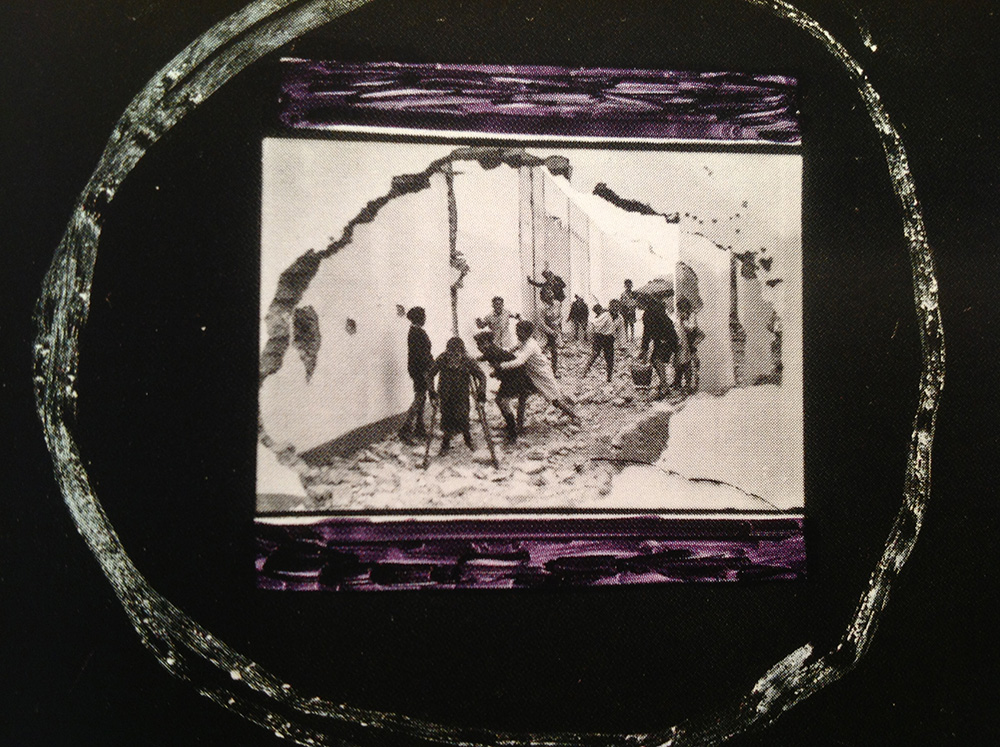

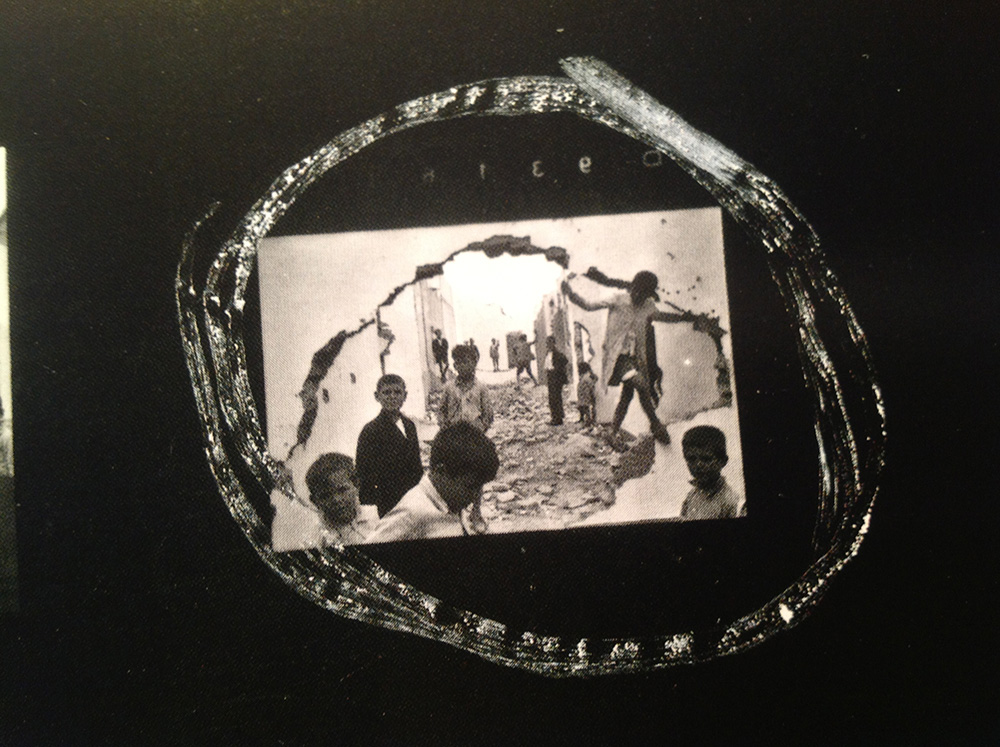

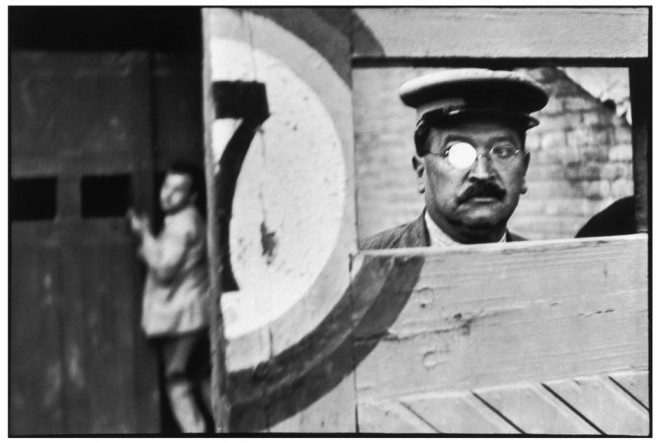

Close-ups of the contact sheet from Seville, by Henri Cartier-Bresson:

One mistake that I see a lot of beginner street photographers is that they only take one photo per scene. I think this is because they too believe in the “myth of the decisive moment” and partly because of the fear that they will be caught taking photographs.

The importance of studying contact sheets

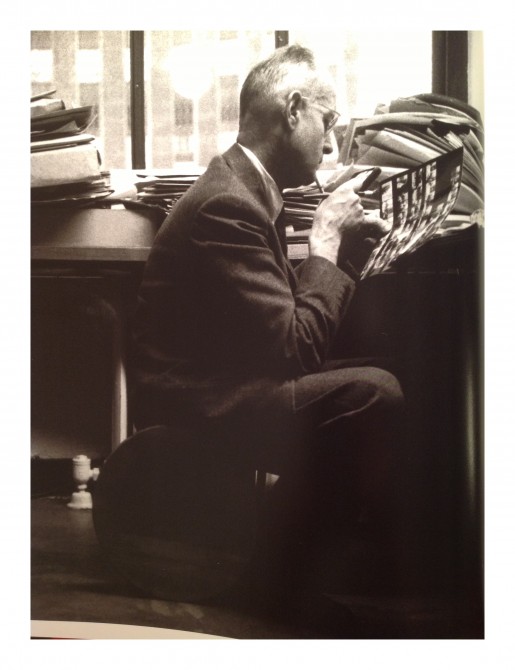

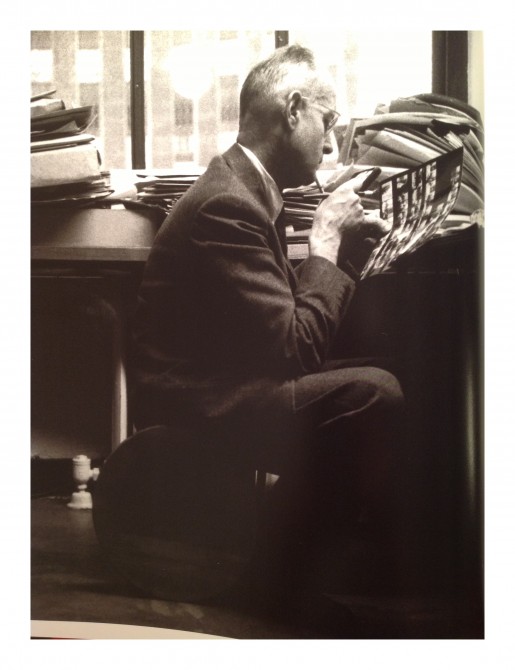

Henri Cartier-Bresson looking at contacts at the New York Magnum Office. 1959. © Rene Burri / Magnum Photos

I have written about contact sheets several times before. For those of you who aren’t familiar with what a contact sheet is it is pretty much a sheet of paper which shows all the photographs a photographer shot on a roll of film. And with this sheet of paper, a photographer can use a loupe (small magnifying glass for the eye) and edit (choose) their favorite images. This was done in the days of the darkroom, and when digital didn’t exist.

Now of course, we have “Lightroom” where we can identify all of our photos of a scene digitally. Instead of having to look at tiny thumbnails, we can now see all of our “almost” photos in full resolution.

Contact sheets are the best learning tools for a photographer. You can learn from contact sheets from other photographers, and also from your own contact sheets.

Henri Cartier-Bresson. SPAIN. 1933. Valencia. Note the two versions of the photo he was considering from. This was the best.

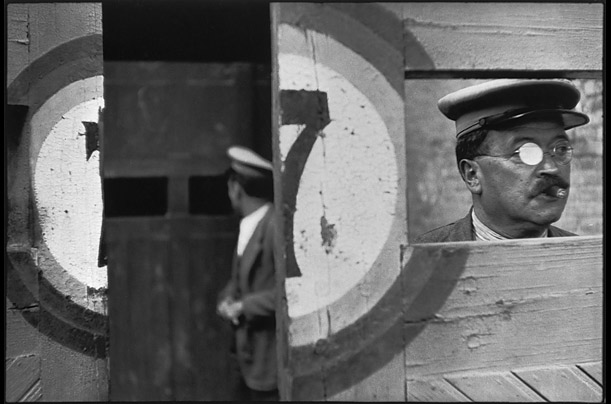

Henri Cartier-Bresson. SPAIN. 1933. Valencia. This image wasn’t as strong as the prior.

Analyzing contact sheets from the masters who came before us is the closest thing we have to reading their minds. We can see how they “worked the scene”– and how they took photos from different perspectives, decided when to hit the shutter, and how many photos they decided to take. Some photographers are able to “nail” their photos in just 5-6 shots, while other photographers will shoot a full roll of 36 photos in just one scene.

Realize that all these master photographers were shooting on film, where it actually cost something to photograph. Now that most of us shoot digitally, there is no excuse for us to not “work the scene” and take many different photos of the same scene.

To learn more about contact sheets, check out my article: “10 Things Street Photographers Can Learn From Magnum Contact Sheets” and also pick up a copy of “Magnum Contact Sheets” on Amazon. It will be the best $100 you will ever spend for your photographic education.

How to “work the scene”

Okay, so we’ve talked about the importance of “working the scene”– and how important it is to take multiple photos of a scene (not just one photo). So how do you exactly “work the scene”?

A few things to clarify:

1. Don’t only just take one photo

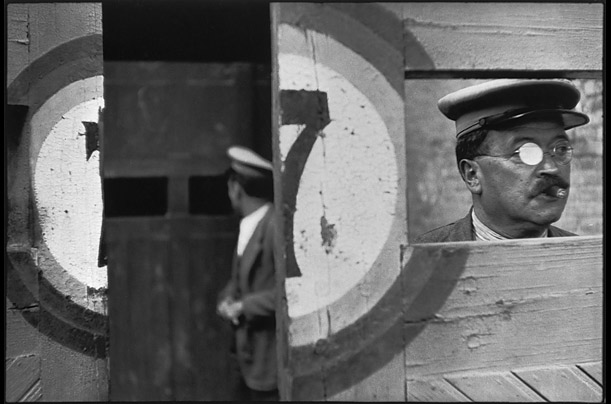

Contact sheet of Elliott Erwitt, “Bulldogs”, New York, 2000. © Elliott Erwitt / Magnum Photos

Once again, it is very tempting to only the one photograph when you see a good scene. When I started off in street photography, I would be deathly afraid of offending people or being “caught in the act” of photographing strangers.

However realize that to make a great photograph, you need to work the scene. You will never know when the “best” decisive moment will occur. In a scene, there are many different great potential “decisive moments”. You generally only know which is the best “decisive moment” afterwards in the editing phase.

“Bulldogs”, New York, 2000. © Elliott Erwitt / Magnum Photos

Even Henri Cartier Bresson once said: “Sometimes you have to milk the cow a lot to get a little bit of cheese.”

2. Don’t chimp

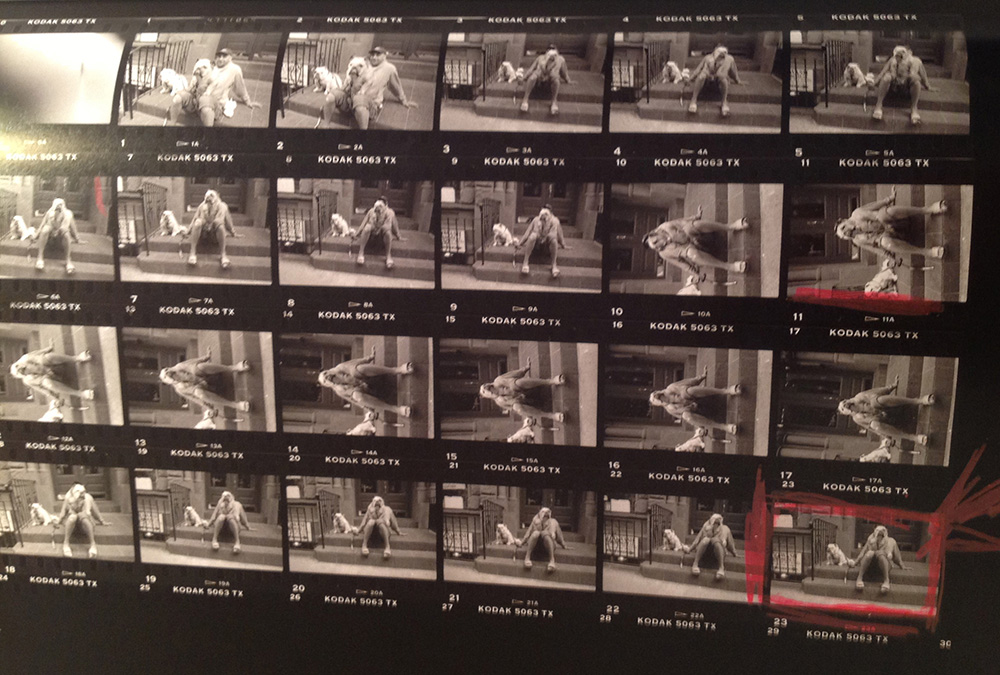

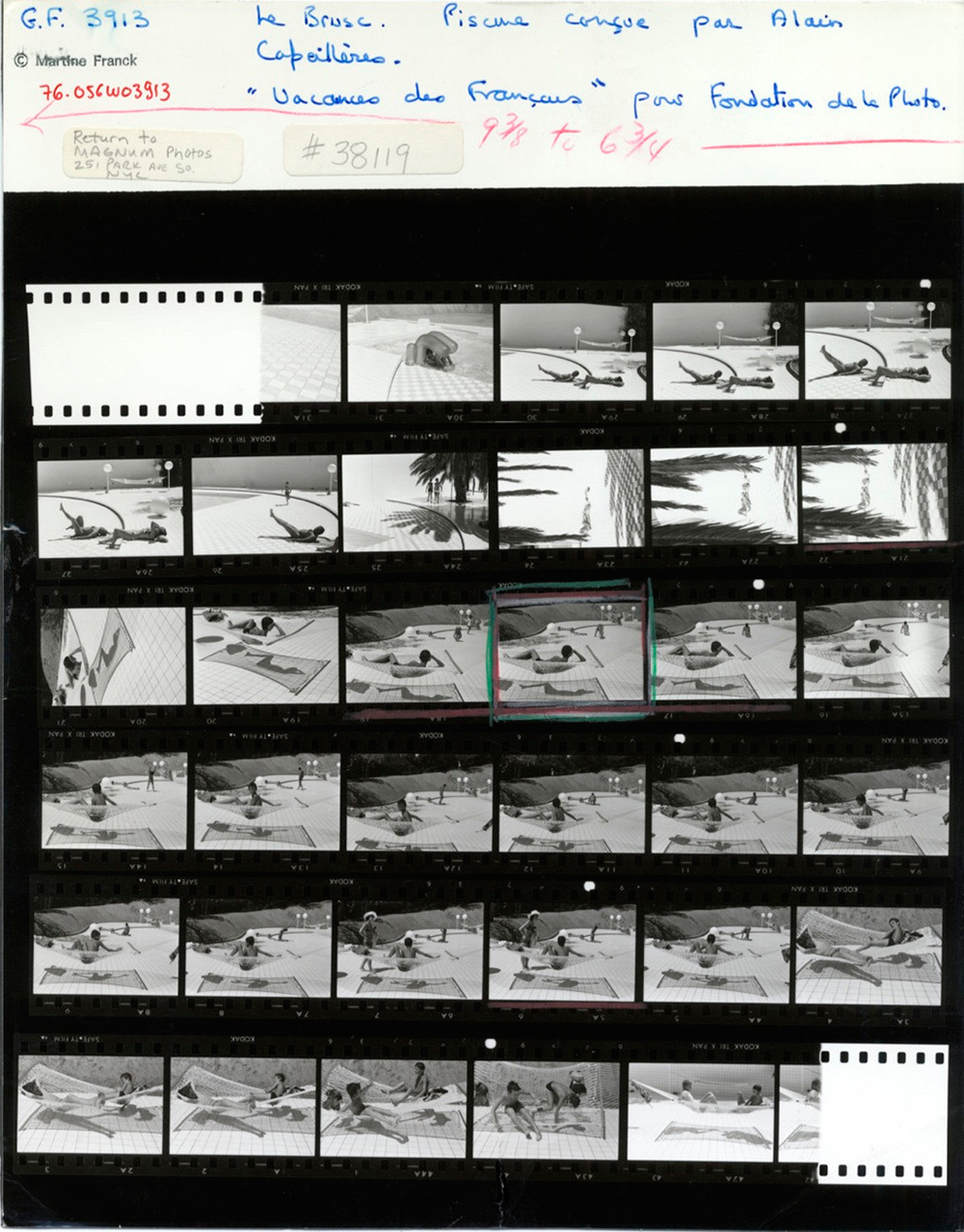

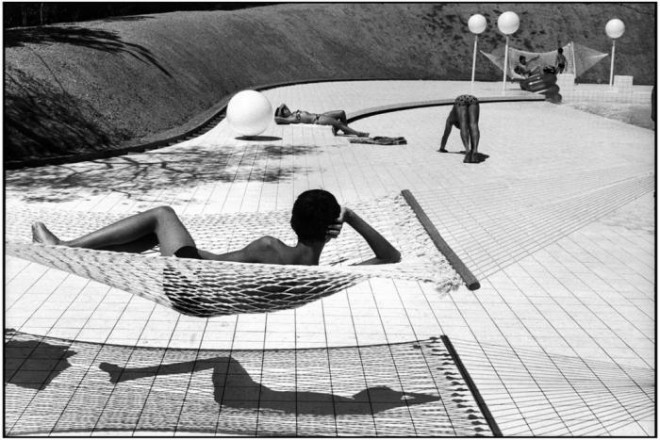

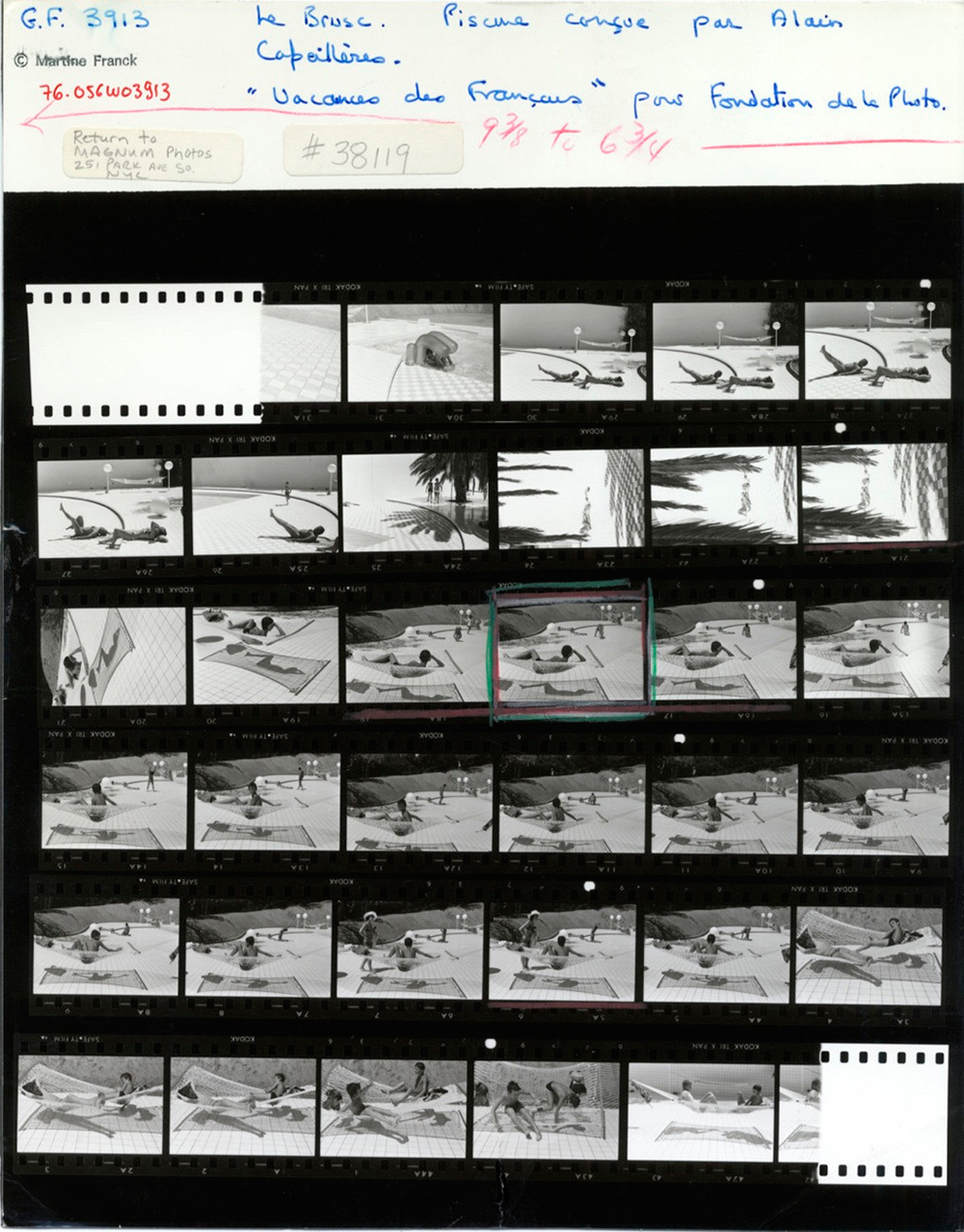

Alain Capeilleres, 1976. © Martine Franck / Magnum Photos.

Another practical tip to better “work the scene” is to not “chimp”. What is chimping you ask? Well, it is when you look at your LCD screen after you take a photograph. Why do they call that “chimping”? Well, apparently film photographers used to make fun of digital photographers by saying they looked like a bunch of “chimps” (or monkeys) when they would crowd around their LCD screens and show off the photos they just took.

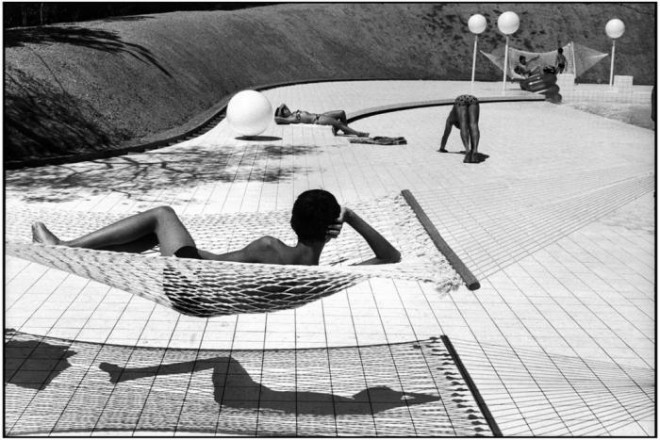

Photo by Martine Franck, Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur region. Town of Le Brusc. Pool designed by Alain Capeilleres, 1976. © Martine Franck / Magnum Photos

So what is so bad about “chimping” anyways? I’ve written an article on why street photographers shouldn’t chimp– but to sum up, chimping kills your flow when you’re out shooting on the streets. Rather than checking your LCD screen several times while working a scene to check for exposure, framing, and what you captured– it is better to just take a lot of photos at different angles and moments and choose the best photos later.

3. Linger

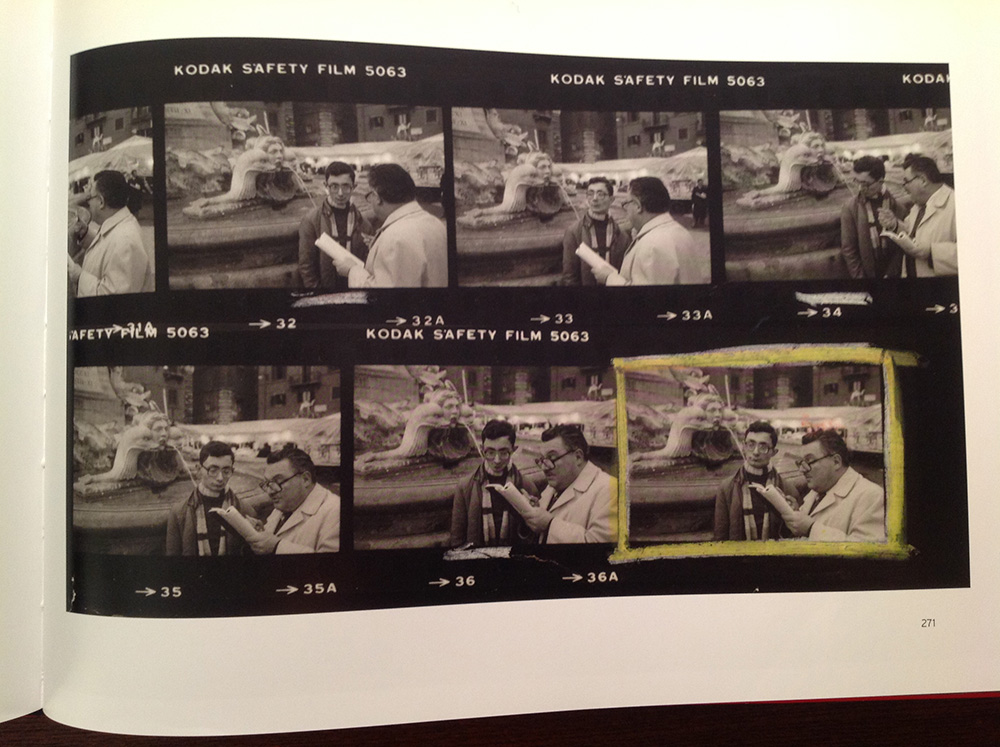

Contact sheet of Richard Kalvar, “Piazza Della Rotonda”. Rome, Italy, 1980. © Richard Kalvar / Magnum Photos

“Lingering” is one of the most difficult things about “working the scene”. Lingering is to “overstay your welcome”. It is generally rude to “linger”. Lingering is like “loitering”– you hang around longer than you should, and people look down on it.

One of the most frequently asked questions I get in my workshops is, “How long should I ‘work a scene’ and linger before I know it’s time to leave, or I got the shot?”

Well, that is the big problem. We have no idea when we either “got the shot” or we’ve hung around “long enough”.

Personally, my philosophy is to be the houseguest that overstays his or her welcome. Did you ever have a friend who asked to stay at your place for a week but ends up staying a few months? Be that guy.

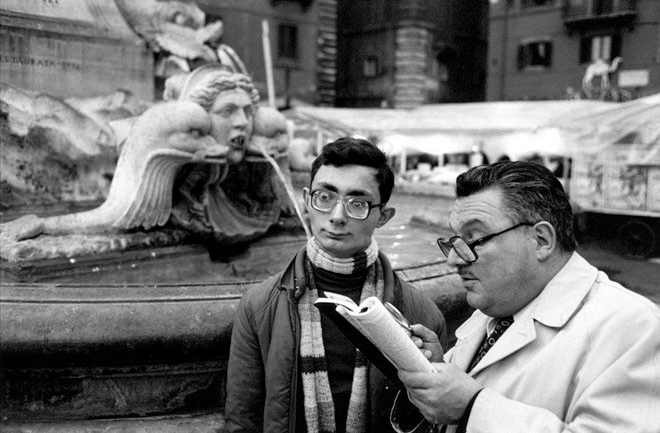

“Piazza Della Rotonda”. Rome, Italy, 1980. © Richard Kalvar / Magnum Photos

The reason I advocate for “overstaying your welcome” is because it is better to linger for a longer period of time because often your best shot will be the last shot. Looking at a lot of contact sheets, especially this image by Richard Kalvar, you see that his best image was at the very end (on his 37th frame, quite lucky). If he didn’t linger around and work the scene, he would’ve never gotten his iconic shot.

Furthermore in street photography, you will only see a great potential scene once in your life. You might see similar scenes, but you will never see the same exact scene with the same exact people, with that background, that light, and that configuration.

So don’t live with regrets, linger around longer than you should– and “overshoot” a scene.

A technique I learned from my friend Charlie Kirk is if you see a great potential scene, hang around and wait a bit longer before you go in and start taking photos. For example, if you see a cool looking guy smoking– linger around him and wait for him to take a puff– then jump in and take a few shots of him inhaling his cigarette.

Lingering is quite painful to do. It is awkward, makes you feel uncomfortable, and might make your subject feel uncomfortable.

One way I get over the awkwardness of lingering and “working the scene” is by pretending I am photographing something behind them and avoiding eye contact. Because I shoot with a 35mm lens, I don’t have to point my camera directly at my subject to get them in the frame.

Another technique is to smile and interact with my subject while photographing them. For example, if I see a good scene, I might start off by shooting candidly– then if my subject makes eye contact with me, I will also make eye contact, smile, keep shooting, and even start chatting with them (hey, you’re looking good!)

4. Look for gestures

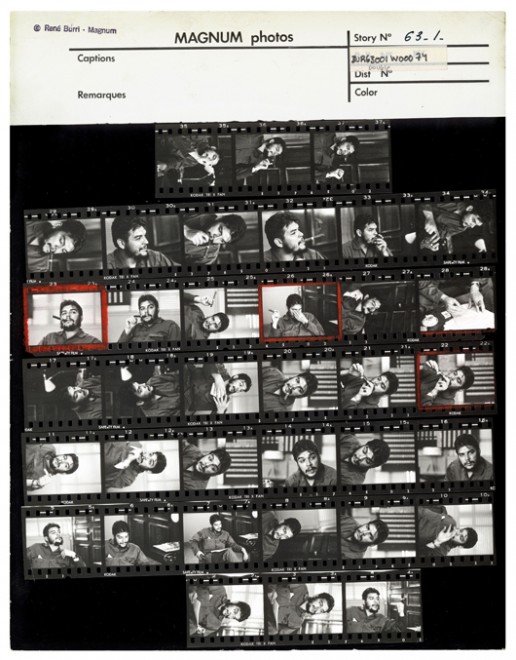

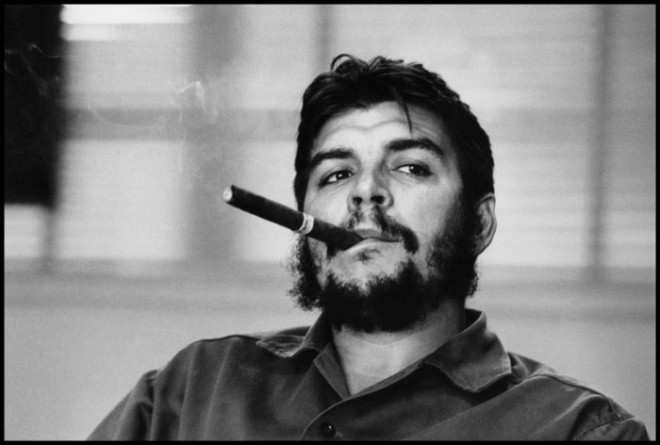

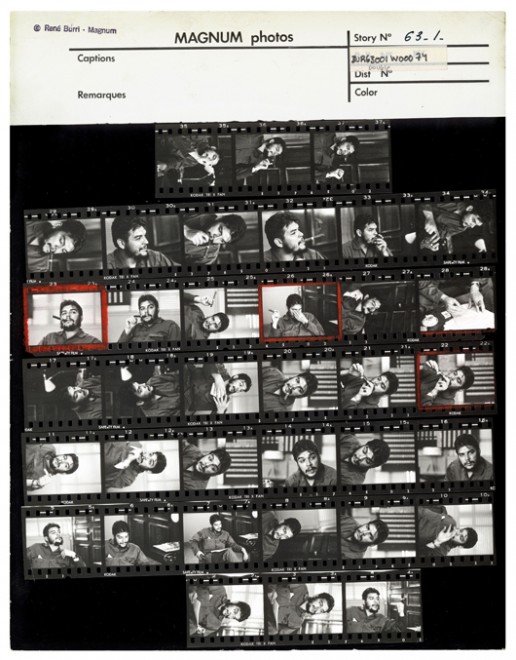

Che contact sheet. © Rene Burri / Magnum Photos

When you are “working the scene”– don’t just put your camera to rapid fire mode and start shooting aimlessly. Rather, be very conscious about when you decide to click the shutter.

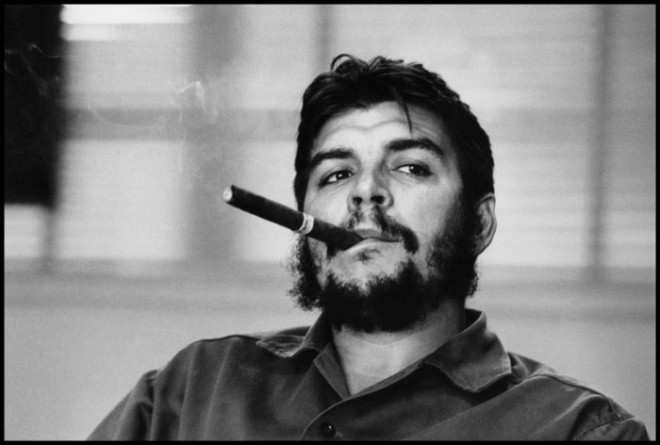

Che Guevara. © Rene Burri / Magnum Photos

Generally I make the decision to click the shutter when I see hand gestures. It can be a gesture of someone covering their face, holding their hands by their sides, or pointing in a certain direction.

Another great tip is to wait for eye contact. Try experimenting taking photos without eye contact, and some photos with eye contact. You never know which photograph will be better. But there is a saying: “eyes are the windows to the soul”– which means if you get eye contact in your street photographs, they can be more intimate and emotional.

5. Keep your feet moving

If you ever watch a boxer, they rarely keep their feet still. The most important thing as a boxer is to never put your heels on the ground. The moment you stop moving is the moment you become a sitting duck– and will be a prime target to be knocked out by your opponent.

Take the same mindset as a street photographer. When working the scene, don’t just keep your feet planted on the ground. Keep your feet moving. Take photos from the left, right, take a step forward, a step backwards. Crouch down. Get different angles and perspectives.

6. Shoot both landscape and portrait photos

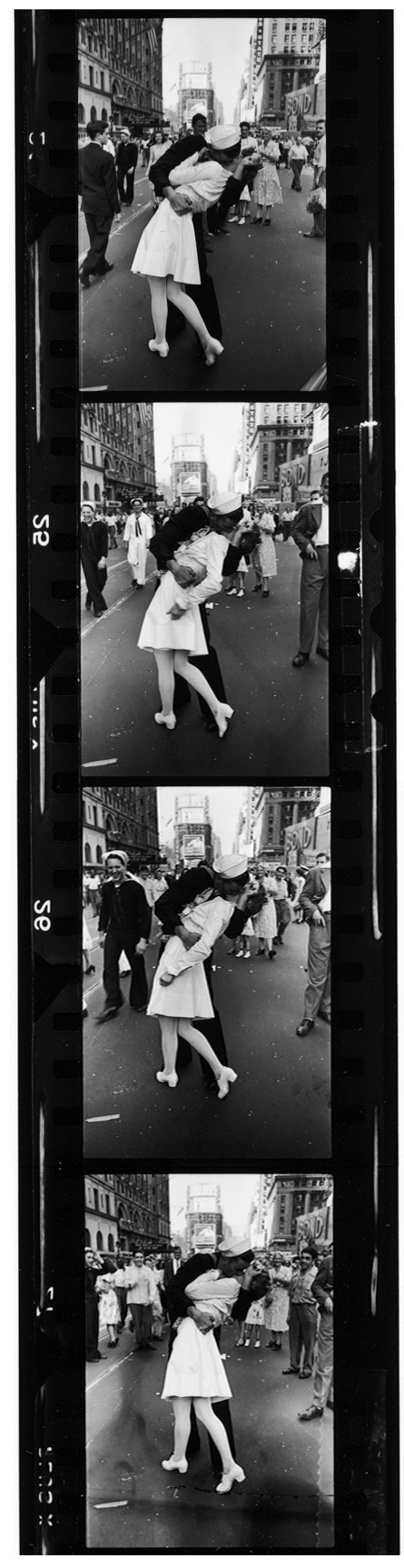

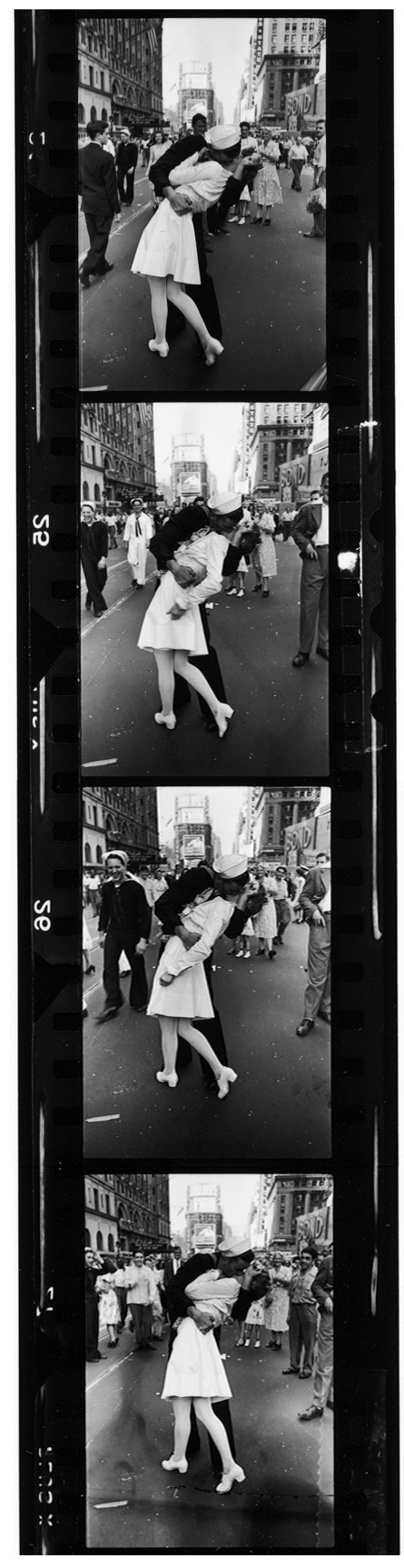

Contac sheet, VJ Day. Photo by Alfred Eisenstaedt

Also when working the scene, try experimenting taking your photos in both landscape (horizontal) and portrait (vertical) modes. When you are in the heat of the moment and see a great street photography scene, it is often difficult to know which is the “better” orientation of your camera for the scene.

So if you have time, try to work out both orientations of your camera– depending on what kind of image you want to create.

7. Be calm and patient

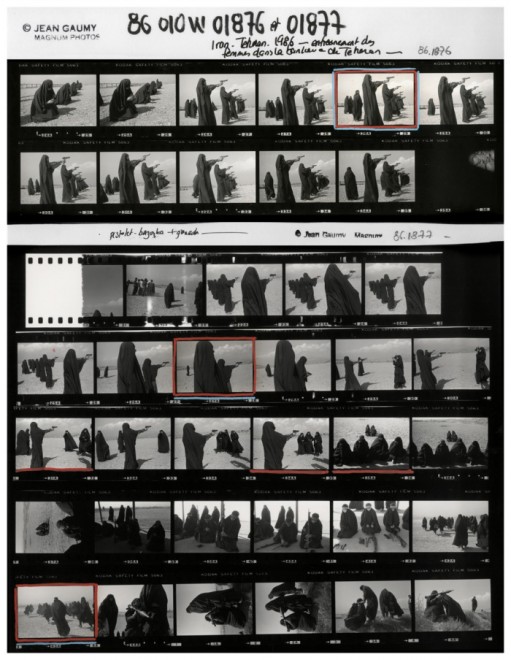

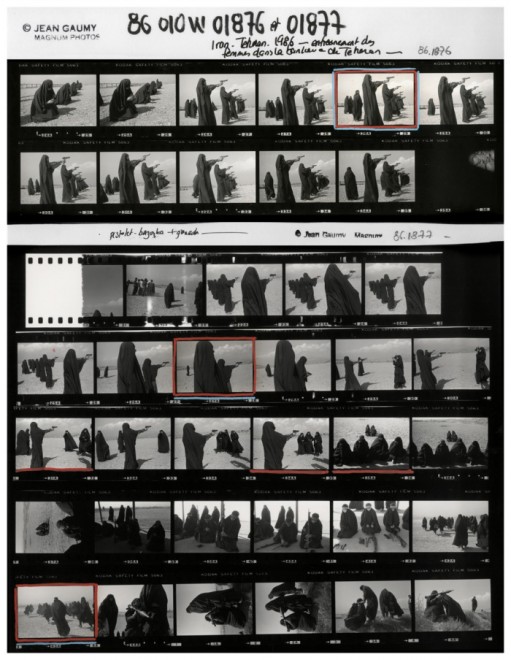

Jean Gaumy, Iran, 1986.

When you are working a scene, remember to try to stay calm and patient. We can sometimes get into a frenzy when working the scene, and trying to get “the shot”. However be calm and patient while you’re shooting– by analyzing when you need to hit the shutter, how close you need to be to your subject to frame them properly, and distracting elements in the background.

Jean Gaumy, Iran, 1986.

When you start off working the scene as a beginner, you might get too much of an adrenaline rush to stay calm and patient when shooting. But realize that with practice be time, you will be more calm and patient when working the scene– which will help you make better rational choices while shooting, and ultimately help you make better images.

8. Focus on the background

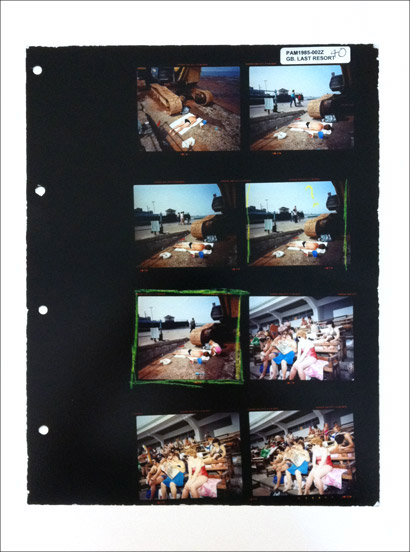

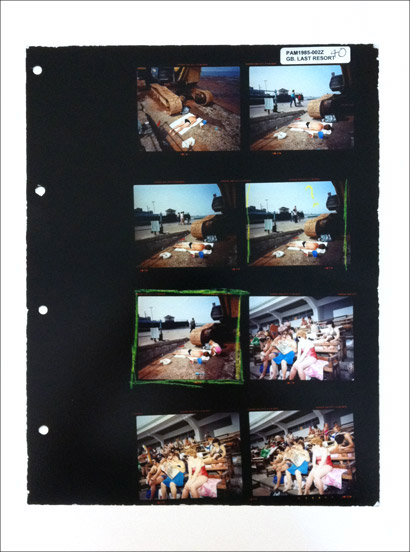

Martin Parr contact sheet from “The Last Resort“

When we are shooting on the streets, we can often focus too much on the subject and not enough on the background.

My advice is once you’ve established who your primary subject (or subjects) are– focus your eyes on the background. Try to get a clean background that doesn’t district– and adds to the scene.

The Last Resort, Photo by Martin Parr

Try to avoid getting random heads, poles, trees, or cars in the background. When you are working the scene, move your feet to get a cleaner background. Messy backgrounds are one of the biggest killers of great potential street photographs.

Conclusion

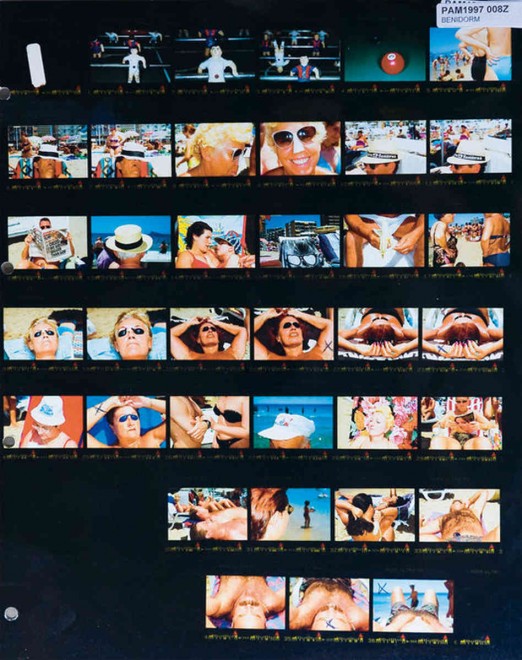

Contact Sheet by Martin Parr from Spain, 1997

To increase your odds of getting “keepers” in street photography, try practicing “working the scene” and lingering longer than necessary. Don’t keep your feet still, always be moving. But at the same time be patient.

Photo by Martin Parr from his “Common Sense” book. Spain, 1997

Also know that by working the scene longer than you need to, it will be strange and awkward. But with time, patience, practice, and a smile– you will be able to overcome this.

Learn more

To learn more, I recommend picking up a copy of “Magnum contact sheets” or reading the in-depth article I wrote on it: “10 Things Street Photographers Can Learn From Magnum Contact Sheets“. Also make sure to check out the “Contact Sheets” section at the Iconic Photos Blog.

If you want to build your confidence in street photography and learn to better “work the scene”– join me at one of my upcoming street photography workshops!

__

LEGAL INFORMATION: ALL THE PHOTOGRAPHS ARE DISPLAYED WITHOUT THE INTENTION OF FINANCIAL GAIN, AS SCIENTIFIC, LITERARY AND/OR ARTISTIC CRITICISM AND/OR RESEARCH, UNDER THE TERMS OF THE CURRENT LEGISLATION CONTAINED IN INTERNATIONAL TREATIES REGARDING COPYRIGHT.

Eric Kim (USA). Lives and works as a photographer in Berkeley, California. His main interest is street photography, to which he has devoted his artistic and educational work. He graduated in sociology from UCLA. Kim gives workshops in several parts of the world, including Canada, Holland, Vietnam, Japan and Australia, and has collaborated in a number of projects with Leica and Samsung. Hs work has been exhibited in Los Angeles and in Leica stores in Singapore, Seoul and Melbourne. and can be seen at: erickimphotography.com

Eric Kim (USA). Lives and works as a photographer in Berkeley, California. His main interest is street photography, to which he has devoted his artistic and educational work. He graduated in sociology from UCLA. Kim gives workshops in several parts of the world, including Canada, Holland, Vietnam, Japan and Australia, and has collaborated in a number of projects with Leica and Samsung. Hs work has been exhibited in Los Angeles and in Leica stores in Singapore, Seoul and Melbourne. and can be seen at: erickimphotography.comEric Kim, "Debunking the “Myth of the Decisive Moment”", Eric Kim Street Photography Blog , May 23, 2014

Contact sheet from Henri Cartier-Bresson in Seville, Spain, 1933. © Henri Cartier-Bresson / Magnum Photos

When I started off in street photography, I believed in the “myth of the decisive moment”. What do I mean by that?

Well, when I first heard of “The Decisive Moment” by Henri Cartier Bresson, I had the wrong impression that he only took one photo of a scene. I imagined Henri Cartier Bresson waltzing into a street scene, carefully aiming his Leica, and taking only one shot and creating masterpieces. I thought he was a demigod– a photographer who somehow had this magic behind his lens.

However if we look at his contact sheets, it is a different story. He (and almost all great photographers) never only take one photo of a great potential scene. Out of Henri Cartier Bresson’s contact sheets, you can see that almost all of his great images required him “working the scene”– taking multiple photos of the same scene at different angles, moments, and perspectives. He hustled hard to get the shots he wanted– and would spend considerable time with his contact sheets, determining which photos he decided were his “best”.

Close-ups of the contact sheet from Seville, by Henri Cartier-Bresson:

One mistake that I see a lot of beginner street photographers is that they only take one photo per scene. I think this is because they too believe in the “myth of the decisive moment” and partly because of the fear that they will be caught taking photographs.

The importance of studying contact sheets

Henri Cartier-Bresson looking at contacts at the New York Magnum Office. 1959. © Rene Burri / Magnum Photos

I have written about contact sheets several times before. For those of you who aren’t familiar with what a contact sheet is it is pretty much a sheet of paper which shows all the photographs a photographer shot on a roll of film. And with this sheet of paper, a photographer can use a loupe (small magnifying glass for the eye) and edit (choose) their favorite images. This was done in the days of the darkroom, and when digital didn’t exist.

Now of course, we have “Lightroom” where we can identify all of our photos of a scene digitally. Instead of having to look at tiny thumbnails, we can now see all of our “almost” photos in full resolution.

Contact sheets are the best learning tools for a photographer. You can learn from contact sheets from other photographers, and also from your own contact sheets.

Henri Cartier-Bresson. SPAIN. 1933. Valencia. Note the two versions of the photo he was considering from. This was the best.

Henri Cartier-Bresson. SPAIN. 1933. Valencia. This image wasn’t as strong as the prior.

Analyzing contact sheets from the masters who came before us is the closest thing we have to reading their minds. We can see how they “worked the scene”– and how they took photos from different perspectives, decided when to hit the shutter, and how many photos they decided to take. Some photographers are able to “nail” their photos in just 5-6 shots, while other photographers will shoot a full roll of 36 photos in just one scene.

Realize that all these master photographers were shooting on film, where it actually cost something to photograph. Now that most of us shoot digitally, there is no excuse for us to not “work the scene” and take many different photos of the same scene.

To learn more about contact sheets, check out my article: “10 Things Street Photographers Can Learn From Magnum Contact Sheets” and also pick up a copy of “Magnum Contact Sheets” on Amazon. It will be the best $100 you will ever spend for your photographic education.

How to “work the scene”

Okay, so we’ve talked about the importance of “working the scene”– and how important it is to take multiple photos of a scene (not just one photo). So how do you exactly “work the scene”?

A few things to clarify:

1. Don’t only just take one photo

Contact sheet of Elliott Erwitt, “Bulldogs”, New York, 2000. © Elliott Erwitt / Magnum Photos

Once again, it is very tempting to only the one photograph when you see a good scene. When I started off in street photography, I would be deathly afraid of offending people or being “caught in the act” of photographing strangers.

However realize that to make a great photograph, you need to work the scene. You will never know when the “best” decisive moment will occur. In a scene, there are many different great potential “decisive moments”. You generally only know which is the best “decisive moment” afterwards in the editing phase.

“Bulldogs”, New York, 2000. © Elliott Erwitt / Magnum Photos

Even Henri Cartier Bresson once said: “Sometimes you have to milk the cow a lot to get a little bit of cheese.”

2. Don’t chimp

Alain Capeilleres, 1976. © Martine Franck / Magnum Photos.

Another practical tip to better “work the scene” is to not “chimp”. What is chimping you ask? Well, it is when you look at your LCD screen after you take a photograph. Why do they call that “chimping”? Well, apparently film photographers used to make fun of digital photographers by saying they looked like a bunch of “chimps” (or monkeys) when they would crowd around their LCD screens and show off the photos they just took.

Photo by Martine Franck, Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur region. Town of Le Brusc. Pool designed by Alain Capeilleres, 1976. © Martine Franck / Magnum Photos

So what is so bad about “chimping” anyways? I’ve written an article on why street photographers shouldn’t chimp– but to sum up, chimping kills your flow when you’re out shooting on the streets. Rather than checking your LCD screen several times while working a scene to check for exposure, framing, and what you captured– it is better to just take a lot of photos at different angles and moments and choose the best photos later.

3. Linger

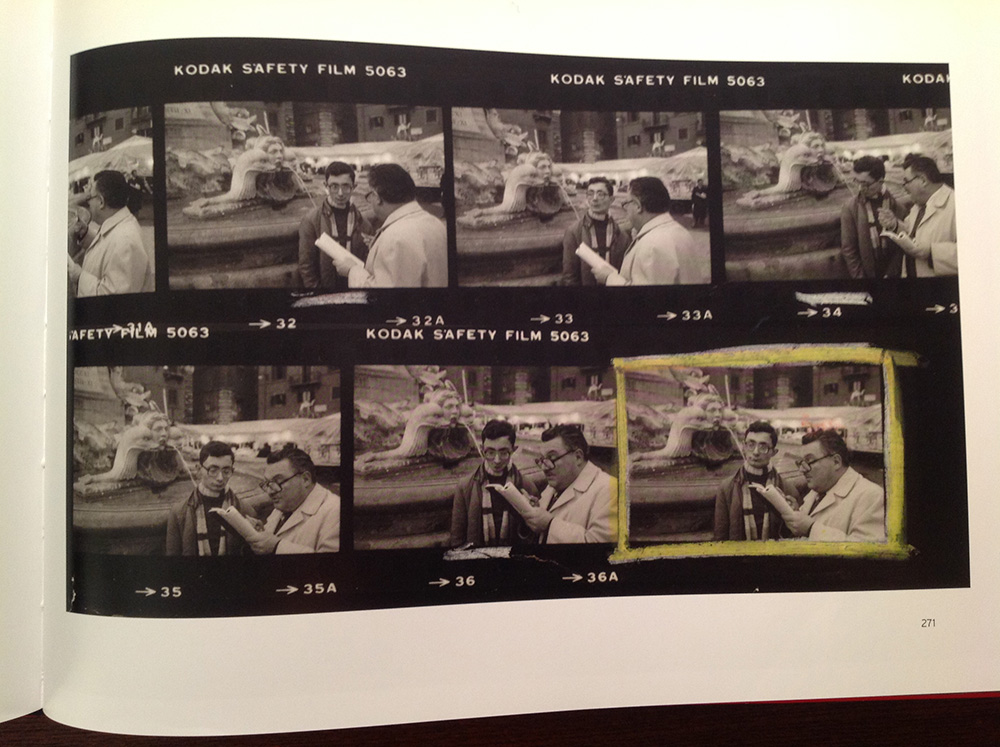

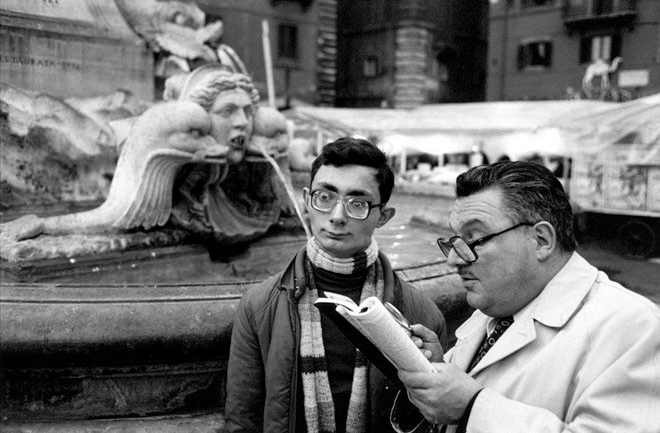

Contact sheet of Richard Kalvar, “Piazza Della Rotonda”. Rome, Italy, 1980. © Richard Kalvar / Magnum Photos

“Lingering” is one of the most difficult things about “working the scene”. Lingering is to “overstay your welcome”. It is generally rude to “linger”. Lingering is like “loitering”– you hang around longer than you should, and people look down on it.

One of the most frequently asked questions I get in my workshops is, “How long should I ‘work a scene’ and linger before I know it’s time to leave, or I got the shot?”

Well, that is the big problem. We have no idea when we either “got the shot” or we’ve hung around “long enough”.

Personally, my philosophy is to be the houseguest that overstays his or her welcome. Did you ever have a friend who asked to stay at your place for a week but ends up staying a few months? Be that guy.

“Piazza Della Rotonda”. Rome, Italy, 1980. © Richard Kalvar / Magnum Photos

The reason I advocate for “overstaying your welcome” is because it is better to linger for a longer period of time because often your best shot will be the last shot. Looking at a lot of contact sheets, especially this image by Richard Kalvar, you see that his best image was at the very end (on his 37th frame, quite lucky). If he didn’t linger around and work the scene, he would’ve never gotten his iconic shot.

Furthermore in street photography, you will only see a great potential scene once in your life. You might see similar scenes, but you will never see the same exact scene with the same exact people, with that background, that light, and that configuration.

So don’t live with regrets, linger around longer than you should– and “overshoot” a scene.

A technique I learned from my friend Charlie Kirk is if you see a great potential scene, hang around and wait a bit longer before you go in and start taking photos. For example, if you see a cool looking guy smoking– linger around him and wait for him to take a puff– then jump in and take a few shots of him inhaling his cigarette.

Lingering is quite painful to do. It is awkward, makes you feel uncomfortable, and might make your subject feel uncomfortable.

One way I get over the awkwardness of lingering and “working the scene” is by pretending I am photographing something behind them and avoiding eye contact. Because I shoot with a 35mm lens, I don’t have to point my camera directly at my subject to get them in the frame.

Another technique is to smile and interact with my subject while photographing them. For example, if I see a good scene, I might start off by shooting candidly– then if my subject makes eye contact with me, I will also make eye contact, smile, keep shooting, and even start chatting with them (hey, you’re looking good!)

4. Look for gestures

Che contact sheet. © Rene Burri / Magnum Photos

When you are “working the scene”– don’t just put your camera to rapid fire mode and start shooting aimlessly. Rather, be very conscious about when you decide to click the shutter.

Che Guevara. © Rene Burri / Magnum Photos

Generally I make the decision to click the shutter when I see hand gestures. It can be a gesture of someone covering their face, holding their hands by their sides, or pointing in a certain direction.

Another great tip is to wait for eye contact. Try experimenting taking photos without eye contact, and some photos with eye contact. You never know which photograph will be better. But there is a saying: “eyes are the windows to the soul”– which means if you get eye contact in your street photographs, they can be more intimate and emotional.

5. Keep your feet moving

If you ever watch a boxer, they rarely keep their feet still. The most important thing as a boxer is to never put your heels on the ground. The moment you stop moving is the moment you become a sitting duck– and will be a prime target to be knocked out by your opponent.

Take the same mindset as a street photographer. When working the scene, don’t just keep your feet planted on the ground. Keep your feet moving. Take photos from the left, right, take a step forward, a step backwards. Crouch down. Get different angles and perspectives.

6. Shoot both landscape and portrait photos

Contac sheet, VJ Day. Photo by Alfred Eisenstaedt

Also when working the scene, try experimenting taking your photos in both landscape (horizontal) and portrait (vertical) modes. When you are in the heat of the moment and see a great street photography scene, it is often difficult to know which is the “better” orientation of your camera for the scene.

So if you have time, try to work out both orientations of your camera– depending on what kind of image you want to create.

7. Be calm and patient

Jean Gaumy, Iran, 1986.

When you are working a scene, remember to try to stay calm and patient. We can sometimes get into a frenzy when working the scene, and trying to get “the shot”. However be calm and patient while you’re shooting– by analyzing when you need to hit the shutter, how close you need to be to your subject to frame them properly, and distracting elements in the background.

Jean Gaumy, Iran, 1986.

When you start off working the scene as a beginner, you might get too much of an adrenaline rush to stay calm and patient when shooting. But realize that with practice be time, you will be more calm and patient when working the scene– which will help you make better rational choices while shooting, and ultimately help you make better images.

8. Focus on the background

Martin Parr contact sheet from “The Last Resort“

When we are shooting on the streets, we can often focus too much on the subject and not enough on the background.

My advice is once you’ve established who your primary subject (or subjects) are– focus your eyes on the background. Try to get a clean background that doesn’t district– and adds to the scene.

The Last Resort, Photo by Martin Parr

Try to avoid getting random heads, poles, trees, or cars in the background. When you are working the scene, move your feet to get a cleaner background. Messy backgrounds are one of the biggest killers of great potential street photographs.

Conclusion

Contact Sheet by Martin Parr from Spain, 1997

To increase your odds of getting “keepers” in street photography, try practicing “working the scene” and lingering longer than necessary. Don’t keep your feet still, always be moving. But at the same time be patient.

Photo by Martin Parr from his “Common Sense” book. Spain, 1997

Also know that by working the scene longer than you need to, it will be strange and awkward. But with time, patience, practice, and a smile– you will be able to overcome this.

Learn more

To learn more, I recommend picking up a copy of “Magnum contact sheets” or reading the in-depth article I wrote on it: “10 Things Street Photographers Can Learn From Magnum Contact Sheets“. Also make sure to check out the “Contact Sheets” section at the Iconic Photos Blog.

If you want to build your confidence in street photography and learn to better “work the scene”– join me at one of my upcoming street photography workshops!

__

LEGAL INFORMATION: ALL THE PHOTOGRAPHS ARE DISPLAYED WITHOUT THE INTENTION OF FINANCIAL GAIN, AS SCIENTIFIC, LITERARY AND/OR ARTISTIC CRITICISM AND/OR RESEARCH, UNDER THE TERMS OF THE CURRENT LEGISLATION CONTAINED IN INTERNATIONAL TREATIES REGARDING COPYRIGHT.

Eric Kim (USA). Lives and works as a photographer in Berkeley, California. His main interest is street photography, to which he has devoted his artistic and educational work. He graduated in sociology from UCLA. Kim gives workshops in several parts of the world, including Canada, Holland, Vietnam, Japan and Australia, and has collaborated in a number of projects with Leica and Samsung. Hs work has been exhibited in Los Angeles and in Leica stores in Singapore, Seoul and Melbourne. and can be seen at: erickimphotography.com

Eric Kim (USA). Lives and works as a photographer in Berkeley, California. His main interest is street photography, to which he has devoted his artistic and educational work. He graduated in sociology from UCLA. Kim gives workshops in several parts of the world, including Canada, Holland, Vietnam, Japan and Australia, and has collaborated in a number of projects with Leica and Samsung. Hs work has been exhibited in Los Angeles and in Leica stores in Singapore, Seoul and Melbourne. and can be seen at: erickimphotography.com