The Rules of Photojournalism Are Keeping Us From the Truth

The ‘frontline’ of Hrushevskogo, from the perspective of the police. The area just behind the concrete barricade was where you needed to have accreditation from the EuroMaidan press office. You can see how narrow the area really was, and where the majority of the photography took place. Central Kiev, Ukraine, 2014.

Just because a photo looks like photojournalism, doesn’t mean it’s Photojournalism.

Photojournalism the ethic, the genre, the act of reportage through story and images, has been hijacked under the guise of “photojournalism” the style — where the style denotes “truth,” objectivity, righteousness, infallibility, etc. At what point did the act of making images subvert the idea of what Photojournalism is and should be?

This is not an argument for pushing aesthetics and technique out the window. Technique is integral to image-making (obviously), but it should service the story first and foremost; the type of image being produced should never dictate the story.

Here are two examples of bad photography from the Orange Revolution, demonstrating the staging element of events. I relied on tropes of grief, joy and “peace” etc. This was the first thing I ever photographed in Ukraine.

Too Slick To Trust

A technically proficient image that looks like those of past photojournalism will catch the eye. A technically proficient image may trick the viewer into thinking he or she is seeing something of substance, of what is commonly referred to as truthful. A technically proficient image meets the media business’ goal for cost-effective public attention.

Commodified imagery threatens photographers’ primary role as storytellers. Amplified technique threatens to dominate the image, and it will lead to picturesque gluttony. We, the news, and our understanding of the news are poorer for it.

These days, the most in-demand news photo is that of happenstance — typically dodged, burned, cropped, dramatized and with “extraneous” details within the frame excised. The photographer’s good intentions of authenticity surrender to economic facility in the clamor for — and shrill claims on — wavering public attention. Image product has been reduced to the glib one-off drama.

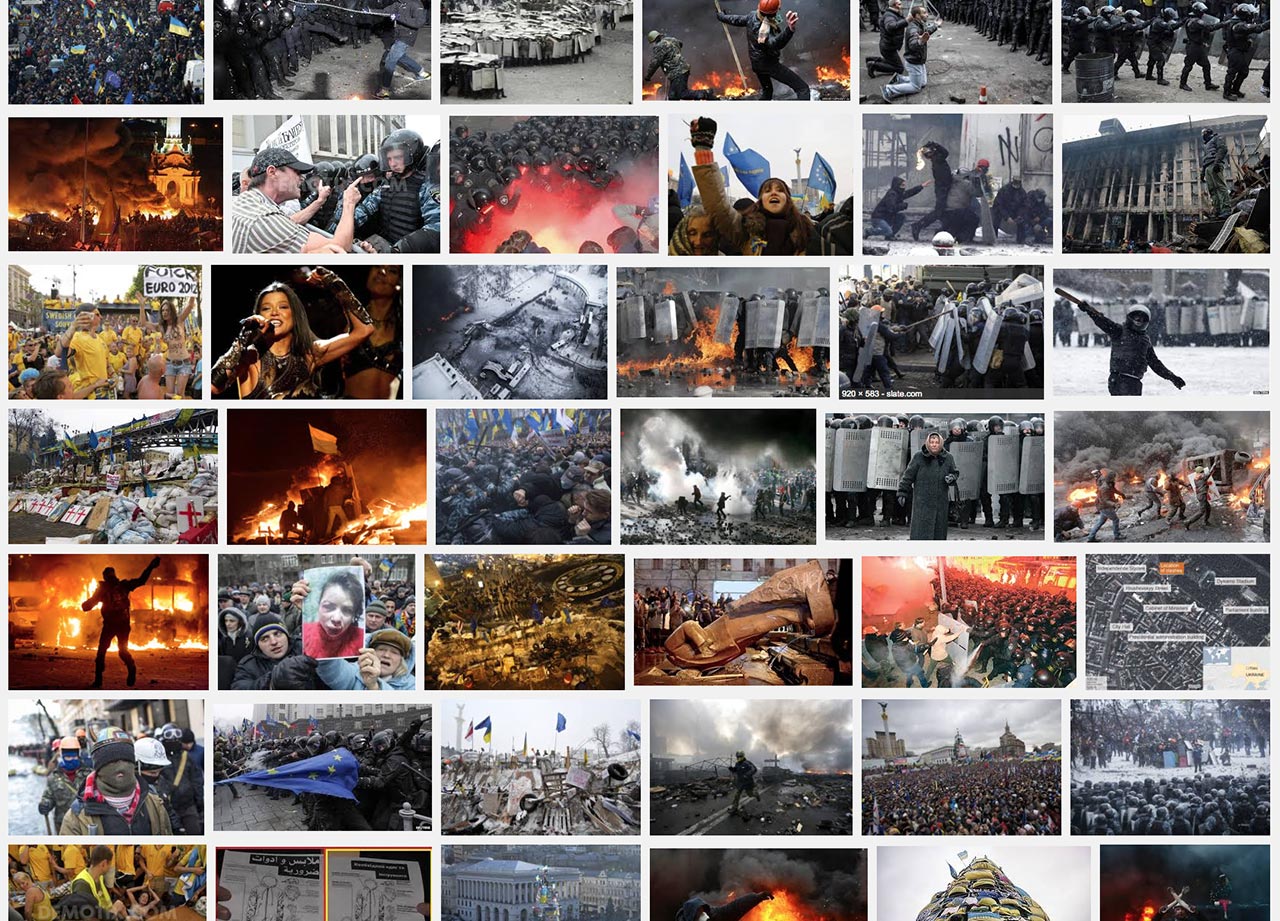

A Google image search for “Kiev Protests.” This contact sheet shows clearly our stranglehold on the ‘imaginary center’ and a total lack of peripheral understanding.

That said, the market demand is not a systematic attack upon journalism, nor a sabotage of democratic press. If only the problems could be so confidently attributed!

No, instead, what we have is a slow degradation of storytelling values in photojournalism. The photographer is rarely employed, nowadays, to tell the story as he or she sees it — the photographer is merely called upon to illustrate another’s account. Such images fail to engage the viewer and fail the larger purpose of the photographer.

We see on our front pages only facsimiles of 90-year-old Leica versions of photos.

Why do we adhere to notions of objectivity in photography? Especially when it crushes creative storytelling from those that hold the camera? Photographers choose where their frame goes. They selectively choose what the audience will see, will believe. Right off the bat, any individual image is deceptive, because there is no peripheral vision. Peripheries provide the greater context. Storytellers may be interested in the periphery, but technical image makers (and the news feeds they keep buzzing) are not.

The Periphery Is Where It’s At

As our world becomes entangled with greater access to other cultures, the professional photojournalism world has, unfortunately, remained fixated on an imaginary centre. As a result, the guidelines of what “makes a good picture” have remained intact. It’s focused on an ideal, the holy grail of the perfect picture, one picture raised above all else.

But what is the use of this philosophic ideal? Marx said that philosophy must relate to everyday experience to be of any use. The perfect picture is a mirage. Allow me to use my experience in Kiev in 2014 to illustrate the point.

I first watched EuroMaidan from afar, on TV, in the papers and the web. Ukraine was a place in which I lived and worked for nearly 10 years. It looked like Kiev was in flames, under siege. I emailed my friends there.

“Vanya, what’s happening, what’s going on?” I asked.

“Ah, Don, it’s okay, just protest on Maidan,” replied Vanya.

“But isn’t Kiev in flames?”

“No, Don, that’s just the news.”

I had to see. Surely something was happening. Of course it was, but not what I had seen on the news.

I’m including this image because it illustrates the scale of the area surrounding EuroMaidan. This is just Maidan Nezalezhnosti (Independence Square), where the speeches, tent city and encampments were located. Below this square is a large shopping mall. It was not uncommon for an event to occur outside, meanwhile people were shopping for jeans at Tommy Hilfiger below. I’m including it because I think it is the type of image that photojournalism too often forgets about.

I’m including this image because it illustrates the scale of the area surrounding EuroMaidan. This is just Maidan Nezalezhnosti (Independence Square), where the speeches, tent city and encampments were located. Below this square is a large shopping mall. It was not uncommon for an event to occur outside, meanwhile people were shopping for jeans at Tommy Hilfiger below. I’m including it because I think it is the type of image that photojournalism too often forgets about.

The area surrounding EuroMaidan was a vast space. In effect, protestors controlled the extended downtown of the city. Not just Maidan itself, but a vast spread throughout the central core. Upon arrival in Kiev in late January, I went to Maidan, and to the “frontline.” By now, the protestors had consolidated their territory. The frontline was the width of a four-lane street. Defined between apartment blocks on one side and a park on the other, a pinched point.

Police on one side, protestors on the other. Sand bags, two destroyed minibuses, detritus built up into a makeshift barricade. A small strip of No Man’s Land in-between. In order to enter the frontline, a media pass was needed. To get a media pass, you went to the Media HQ, showed your press credentials, signed and got your ticket. That day, I was ticket number 230. 229 accredited press before me.

Theatre Of War

The scene itself was theatre. Here we had the stage of revolution. A police line, protests as the Greek chorus, the set itself was the barricade. There was literally an audience. Grandmothers, parents, kids, teens, workers, passersby, anybody could come and spectate, and they did. Every weekend, thousands of people would stroll and watch. There was a slight hill to the left where you could get a good view overall, hundreds of people amongst the birch trees, watching the protestors sit and wait for something to happen, vigilant, on guard.

The protestors themselves were dressed for a show. Their outfits were kitted together from various leftover pieces found in someone’s homes, a weird montage of hockey player, fighter and knight. Many of the protestors themselves referenced modern media, as they had seen images of protests around the world and from different generations — the Russian Revolution of 1917, Paris ‘68, Vietnam, Kent State, British union strikers of the 1980s, Anti-Iraq protest, Arab Spring and their very own Orange Revolution.

The EuroMaidan protestors had been consumed by TV, by news images repurposed for a new battle, but were now referencing their own protest history. They promised to put on a show, and the media came to participate.

I’m caught in a weird loop where we photograph the protestors, the protestors see what gets photographed, they dress the part and then we photograph them again.

“If I go to a protest, what do I wear?” Simple: just reference the media. Many protestors talked about this.

“We are Mad Max” was the most popular analogy. “We are Knights of the Round Table!” “We are warriors of 1917!” But none of it was real. What was real, was the idea of protest, that people could choose to fight and die for a cause.

The story was real. The story was authentic.

Sergiy Lebedynskyy and Vladyslav Krasnoshchok. From the series EuroMaidan.

Most of the images that came from the EuroMadian protest, however, were not real. Not much of what I read or saw in the media was an honest reaction to the realities of central Kiev.

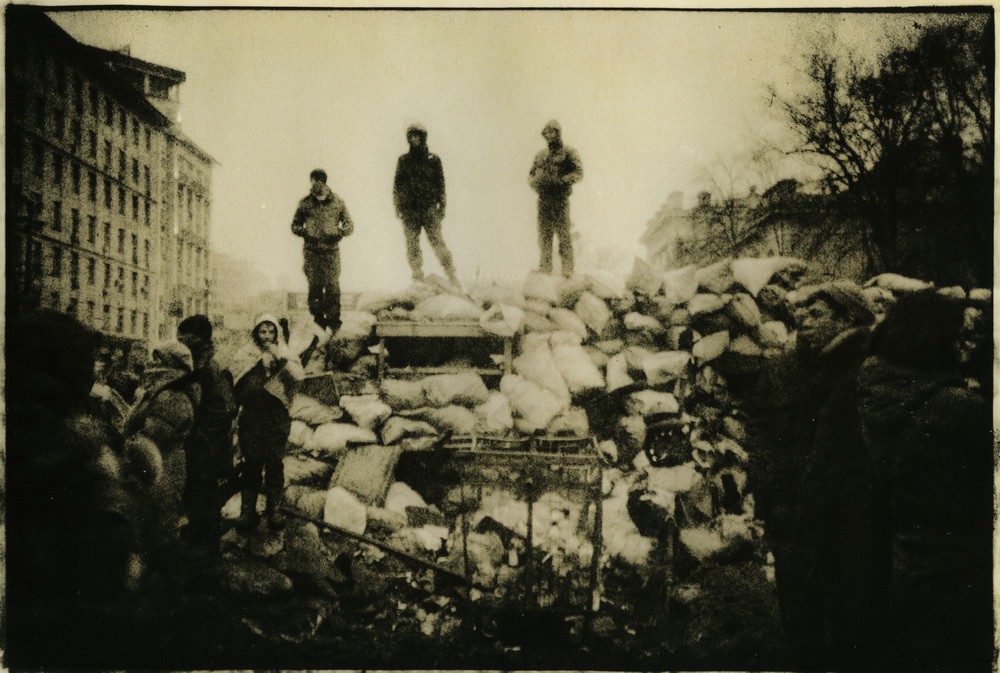

The work that rose above was work that had intent and authorship. Sergiy Lebedynskyy and Vladyslav Krasnoshchok with their book EuroMaidan made an intensely personal and genuine document of the revolt, which didn’t capture the event so much as the feeling, the tactile response to revolution — an authentic look inside what a protest really is. Protest is for cameras, but “protest” is real.

Sergiy Lebedynskyy and Vladyslav Krasnoshchok. From the series EuroMaidan.

And so the photographer who enters the staged play, the theatre of news, has to be wary. Are you participating in the facade of the event, or are you genuinely documenting it? When you photograph the frontline, do you turn around? Do you show the old lady entering her apartment, the couple having coffee, or the tired protestor sleeping? Do you show the audience, the set, and the actors? If not, then it enables the deceit of a staged moment.

A clear focus on intent leads to authorship, honesty, authenticity and story.

Sergiy Lebedynskyy and Vladyslav Krasnoshchok. From the series EuroMaidan.

How Did Technique Come To Replace Story?

From a Marxist perspective, technique may have replaced storytelling on account of capital’s natural inertia and avoidance of risk. Stories and story ideas are subject to budgetary attenuation just as camera parts and travel budgets are. Plastic lenses are cheaper than glass, and anybody can mimic a dodged and burned print with ubiquitous software.

However, there is no cheap substitute for good story-sense and, as such, good story sense gets overlooked.

It’s a given that a photographer has to make something, bound on using the four-sided frame and the small “negative,” armed with variations of the 35mm rangefinder first perfected by Leica 90 years ago. The conventions this technology imposes on story are legion. Look back at documentary photography before the rise of the Leica and you have some invincible variations, limited by technical capability, but still contributing to an evolving, novel language.

Suddenly, within a single generation, that image perfected by Cartier-Bresson and others has frozen solid.

Digital formats gave us technical progress, but no visual progress.

With photojournalism’s suspect history and its acceleration into the technical age, there is now a permanent element of unfaithfulness within the photographic medium. What makes photography faithful is not laborious inquisitions into levels of image-processing. Well, that is part of it, but mostly it is our collective faith in the intent of the story.

Eugene Smith once said: “The honesty lies in my — the photographer’s — ability to understand.” It has nothing to do with aesthetic and technical execution of the photograph, but in the author’s integrity in developing a story.

Love Photographers First, and Photography Second

I’m not saying this to champion photography above all other creative mediums. I’m not saying this to convince you to love an unlovable cheat. I’m saying this so we might support the earnest and inventive storytellers and be damned the others that act the part in our industrial news complex.

The spectrum of storytelling means there is more than one way to photograph a story, just as there are other methods to tell stories — music, film, journalism, literature, poetry, folksong, art and many more. World War I saw journalism at its nadir. Wilfred Owen’s and Siegfried Sassoon’s poetry informed the era because it was the only way to describe the horrors of the trench. Journalists were mouthpieces for the government, rarely going to the line and rarely understanding what the soldiers were experiencing. Immediacy has no claim whatsoever over story. The event should dictate to the author how and what it gets told.

Owens and Sassoon were already literary inclined. However, both poets were raised in the 19th English pastoral tradition, susceptible to the beauty of the land and the simplicity of country life. When the land is suddenly broken into raging pits of bottomless death, how do you react? Owens and Sassoon’s poetry was some of the most incendiary incantations on war ever written. The other “voice” that arose out of WWI was the memoir — a fictitious account based on a real life. Sassoon, again, Memoirs of an Infantry Officer. These works show us the power of artistic license, of deception, of voice, theatre and staging equal to the event.

This image is a composite of 9 image files. Look closely and you’ll see one man with a severed head, one man with half a skull and one man dismembered at the waist — not literally, they just appear so due to the stitch I made in post production. I left these anomalies in so as to “prove” that the images are not real. I have nothing to hide. There is much more action here than there was in any single view I had at Maidan. But it’s representative of what it felt like to be there. What we see in media — in mediated forms — is hyper reality. Nothing is real.

This image is a composite of 9 image files. Look closely and you’ll see one man with a severed head, one man with half a skull and one man dismembered at the waist — not literally, they just appear so due to the stitch I made in post production. I left these anomalies in so as to “prove” that the images are not real. I have nothing to hide. There is much more action here than there was in any single view I had at Maidan. But it’s representative of what it felt like to be there. What we see in media — in mediated forms — is hyper reality. Nothing is real.

Time To Break Up

For a long time the marriage between photography and news media was good. The media fed us, clothed us, bathed us. It supported our work and supported our stories. But ad revenues plummeted and the industry collapsed, so too did decorum.

Work for hire. Stagnating day rates. Guarantees gone. Editors’ support gone, 16 pages to showcase a story gone. All of it, within a generation, disassembled.

As our pay-cheques dwindled, our fears of the future rose. Understandably. For decades, “the media” was the premiere showcase for photography. It was a top down organization, they assign, we photograph. It was a simple transaction that produced images. But we didn’t realize it was at the expense of producing stories. The photographer’s role became one of service and of contractor. Our role within the story began to negate the story, as we were seen not as caretakers of the story, but as a tool for it. The “story” was left to someone else.

A fine knife stripped us of a certain vitality, so that in the end any photographer could be hired, perhaps for visual prowess and technical ability … or even just access. In the end it wasn’t about “story,” it became more about framing a given story through pictures.

More examples of my bad photography in 2004 of staged moments in Kiev, Ukraine following the Orange Revolution. The Orange Revolution was quite literally staged; television cameras, lighting, fireworks and other elements of spectacle appeared nightly, ready for prime time.

There have been moments of great reportage and storytelling by photographers, but they’ve emerged in spite of the system and not because of it. Telex Iran (1979) by Gilles Peress is only one example. Suddenly the photographer was once again an empowered storyteller! The mass media wasn’t primary any more and we could see a glimpse of what could be created by a photographer with a clear storytelling intent whose voice determined the outcome of the image, rather than the illusion of photojournalism determining the story. Pictures follow understanding which follows intent.

It is not easy. The media landscape remains full of privy rules and set obligations: “That’s how we do it.”

For the most part, though, we are left to deal with the legacy of a media that used photography too infrequently for the purposes of storytelling, and too often to satisfy economic efficiencies. A story cannot live on it’s own, it needs someone to tell it: this makes for a sublime conflict in today’s media environment. Intent and context are what will make a lasting work.

Today, the photographer, the storyteller, has the control of stories if he or she accepts that responsibility. You can tell a story, and, most importantly, you can show it to the world.

We are not limited to a set of outlets. The outlet is you.

Donald Weber (Canada, 1973). Lives and works in Toronto. Photographer and teacher. He has received numerous awards and fellowships, including a Guggenheim Fellowship, the Lange-Taylor Prize, The Duke and Duchess of York Prize, two World Press Photo Awards, PDN’s 30, was named an Emerging Photo Pioneer by American Photo and shortlisted for the prestigious Scotiabank Photography Prize. His diverse photography projects have been exhibited as installations, exhibitions and screenings at festivals and galleries worldwide including the United Nations, Museum of the Army at Les Invalides in Paris, The Portland Museum and the Royal Ontario Museum.

Donald Weber (Canada, 1973). Lives and works in Toronto. Photographer and teacher. He has received numerous awards and fellowships, including a Guggenheim Fellowship, the Lange-Taylor Prize, The Duke and Duchess of York Prize, two World Press Photo Awards, PDN’s 30, was named an Emerging Photo Pioneer by American Photo and shortlisted for the prestigious Scotiabank Photography Prize. His diverse photography projects have been exhibited as installations, exhibitions and screenings at festivals and galleries worldwide including the United Nations, Museum of the Army at Les Invalides in Paris, The Portland Museum and the Royal Ontario Museum.