Max de Esteban

ZZ. What led you to appropriation and remix and how are they significant in your work?

M. Appropriation and remix have a long artistic tradition, beginning with Picasso’s collages. As early as the 1920s, Hannah Hoch and the Dadaists used this mode of expression to create major photographic works. In music, for example, from today’s DJs and Pop to Glenn Gould and Miles Davis, the practice of remix, collage and appropriation has been an essential part of their production. What I mean is that as an artistic concept, appropriation and remix are pretty standard and not particularly groundbreaking.

The interesting question is why their aesthetic power has been reasserted in photography precisely now. And I think one possible answer would be the combination of the formal exhaustion of the linear perspective as a photographic representation of the world and the huge impact digitization is having on every aspect of our lives. I would answer your question by turning it around and saying I find it hard to think of a truly relevant form of photography for the world we live in that continues to respect the Eurocentric, reactionary structure of the dark room.

ZZ. What do you mean by Eurocentric and reactionary?

M. The linear perspective, the visual structure resulting from the dark room, is a very particular and ideological way of visualizing the world. Panofsky has a text about it he wrote in 1927, a real classic, that is a pleasure to read.

But what is really remarkable is that it is an exception in art history. In 10,000 years of history, the linear perspective spans only 500 years and is located exclusively in the West. It has never been of interest to Asian, or pre-Columbian or African art ... it is a European way of seeing in a period beginning in the Renaissance and ending in the 19th century.

And this is no coincidence because its ideological content is well known. The linear perspective arranges the world from the point of view of an autonomous individual whose individuality is the world’s principle of meaning. It is pure Descartes. And we all remember Descartes’ Fifth Meditation, which states that since the essence of matter is its extension, geometry is an essential instrument for understanding nature. Modernity can be defined as the advance of abstraction and the prevalence of the quantitative over the qualitative in which the mathematical-scientific order is regarded as the only source of valid knowledge. There is so much contemporary thought that debunks this narrative that I won't repeat it here.

Thus, surprisingly, my earlier comment is still valid. Why should digital photography continue giving priority to a functionally and ideologically devalued visual structure?

ZZ. Why do you think digital photography changes the way we understand appropriation and remix?

M. Digital technologies are leading us towards the radical transformation of our world. By replacing the industrial economy with a bio-cybernetic system, digitization is modifying our environment, our subjectivity and soon, our bodies. This is the technological phenomenon that will define our era and therefore our culture.

Unlike an analog file, a digital file is invisible. It is a code whose visual expression is a translation highly mediated by default algorithms, whose most prominent feature is precisely its immateriality.

This technical structure fits our current era of abstraction and non-referentiality and the digital financialization of the economy. How do we see the world today? We have the answer on our computer and Smartphone screens. What is the essential aspect of the financial economy? The recombination of existing information units to create new information, in other words, “constructive compositing”. Digitization has definitively invalidated linear narrative, the monocular perspective and the author’s “authority”.

ZZ. You attach a great deal of importance to the concept of technology in your work. Could you explain why?

M. We are moving towards a world as a “technological whole”. Technical manipulation has already invaded our bodies, the last frontier, and no-one doubts that having machines inside our bodies will soon become commonplace.

The cyborg raises more complex issues for our species, which, though somewhat deteriorated, continues to maintain the autonomy of the subject as an essential value. Abstraction, digitization and cyborg are three sides of the same coin that heralds our new world, whether we like it or not. In my opinion, reflecting on technology is necessary, urgent and politically essential.

ZZ. And how do you think technology affects the practice of photography?

M. I’d like to point something out. One of the problems of photography is the confusion between technology and use. Writing is a communication technology that serve to draw up a commercial contract and compose a poem by Virgil. It is the same technology but nobody would ever mistake Virgil for a notary. In photography, we tend to combine uses, which creates enormous confusion in critical discourse. Throughout this interview, I have been referring to the use of photography as a means of artistic expression.

The thing is that photography has always been halfway to a cyborg. It is a machine that affects and to some extent determines human power, thought and expression and is therefore an ideal place for reflecting on the issues I mentioned earlier.

To give you an example: How can you visually depict the abstraction of the economy when the material references of wealth have been replaced by a binary code? That’s what I’m doing at the moment and it forces me to rethink what “representation” means in this new visual regime.

Another example: How does the idea of the cyborg affect art categories? That’s the topic I try to get my teeth into in the text “Cyborg Art: art in the bio-cybernetic era”. And there are a thousand other possible ideas that make photography an exciting medium at this particular historical time. The point is that if photographic practice does not take up the challenge raised by contemporaneity, it will be relegated to banality and antique shops.

ZZ. How do you choose the sources you use and what significance do they have for your series?

M. Like nearly everything in life, it is a combination of determination and chance. In my case, too much planning and/or reflection in my work paralyzes me while dreams or rather daydreams are of paramount importance.

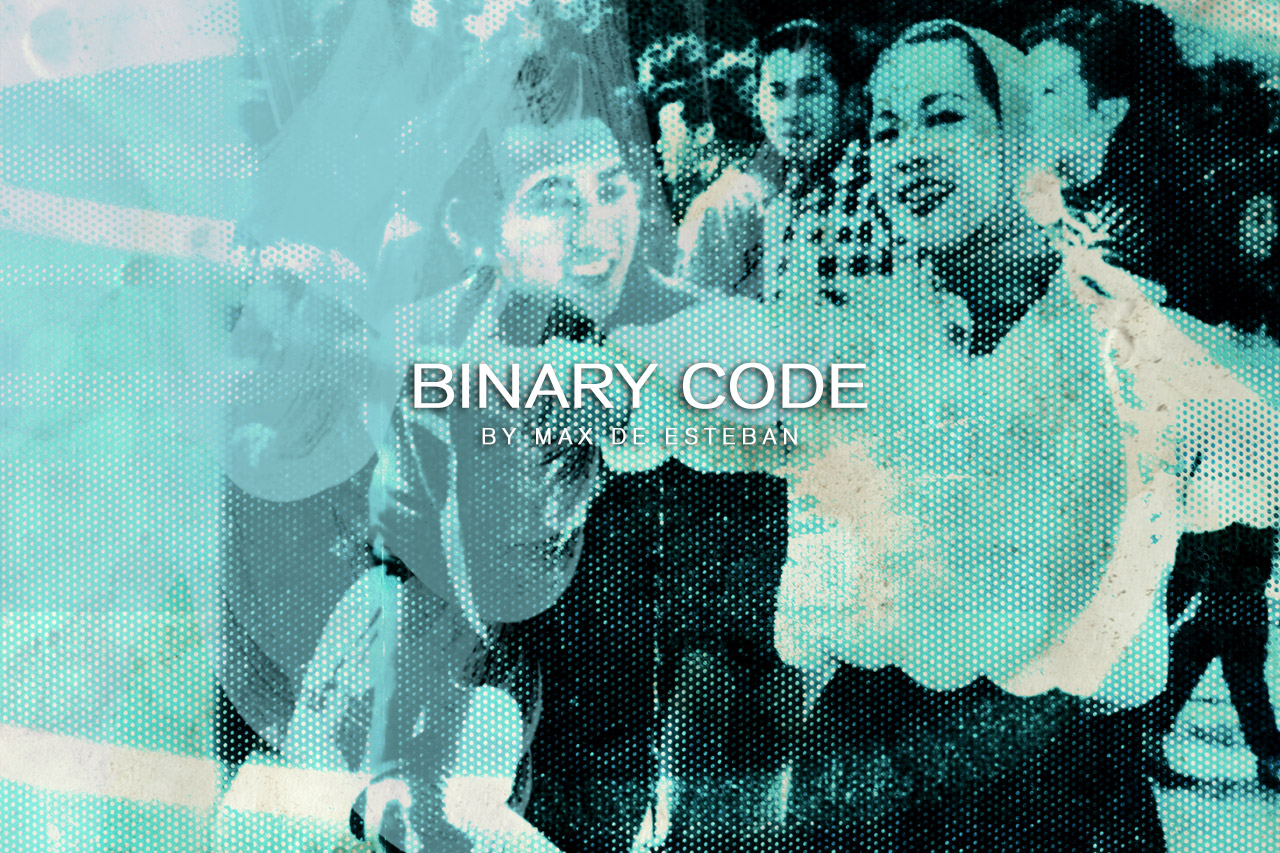

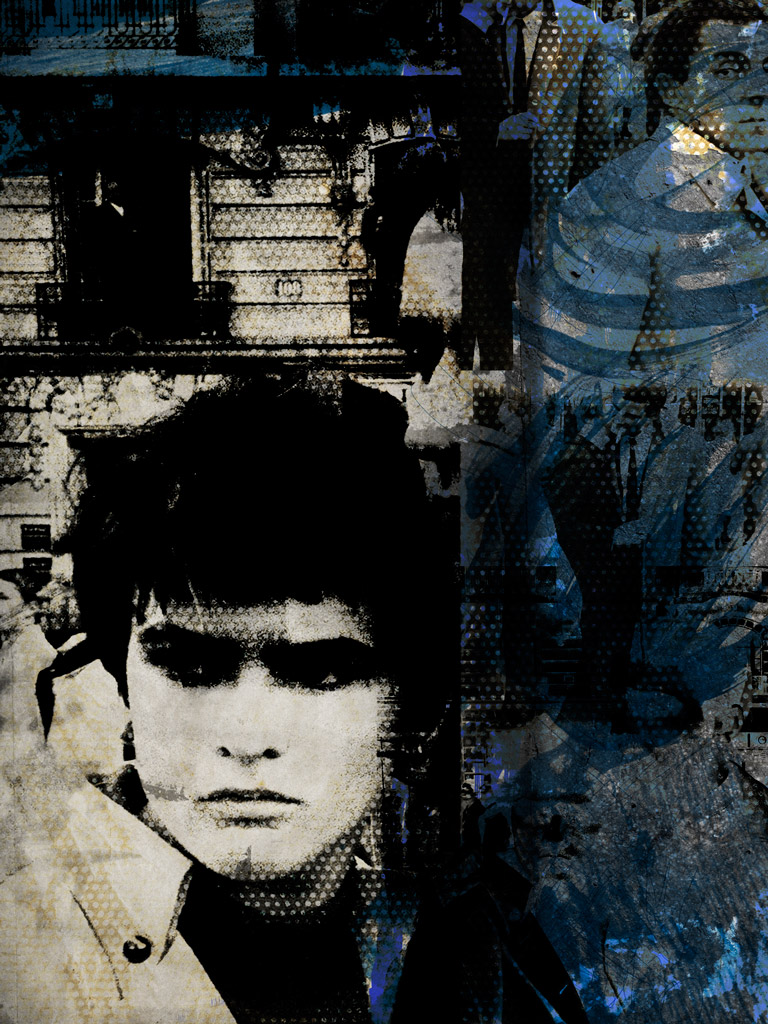

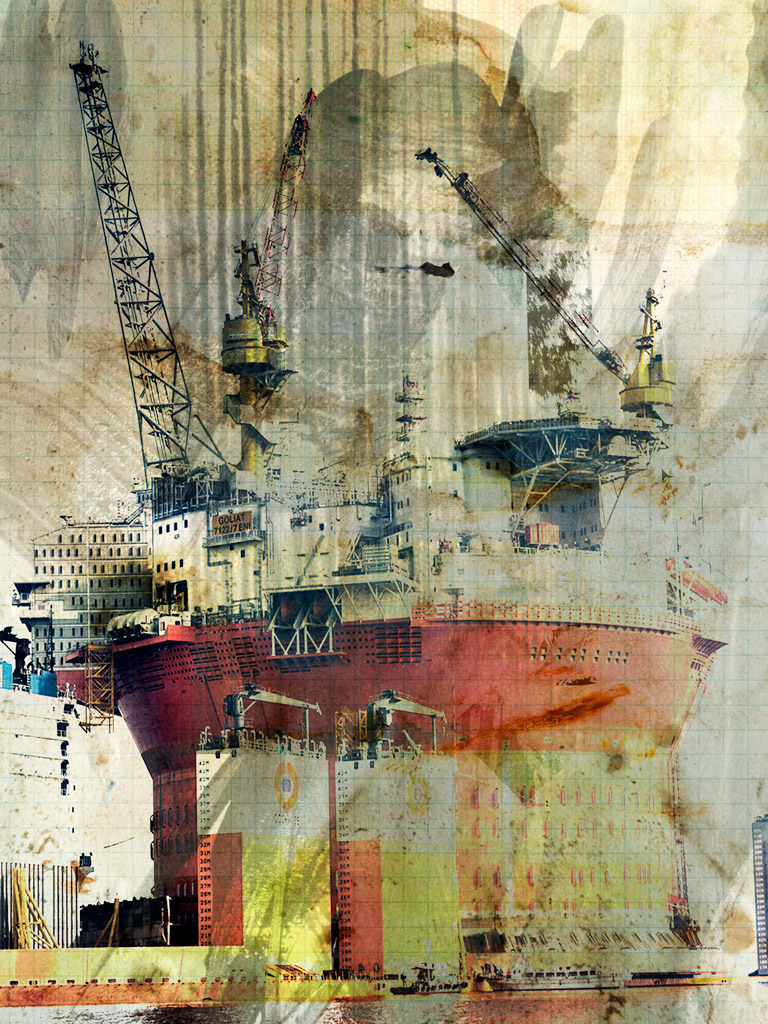

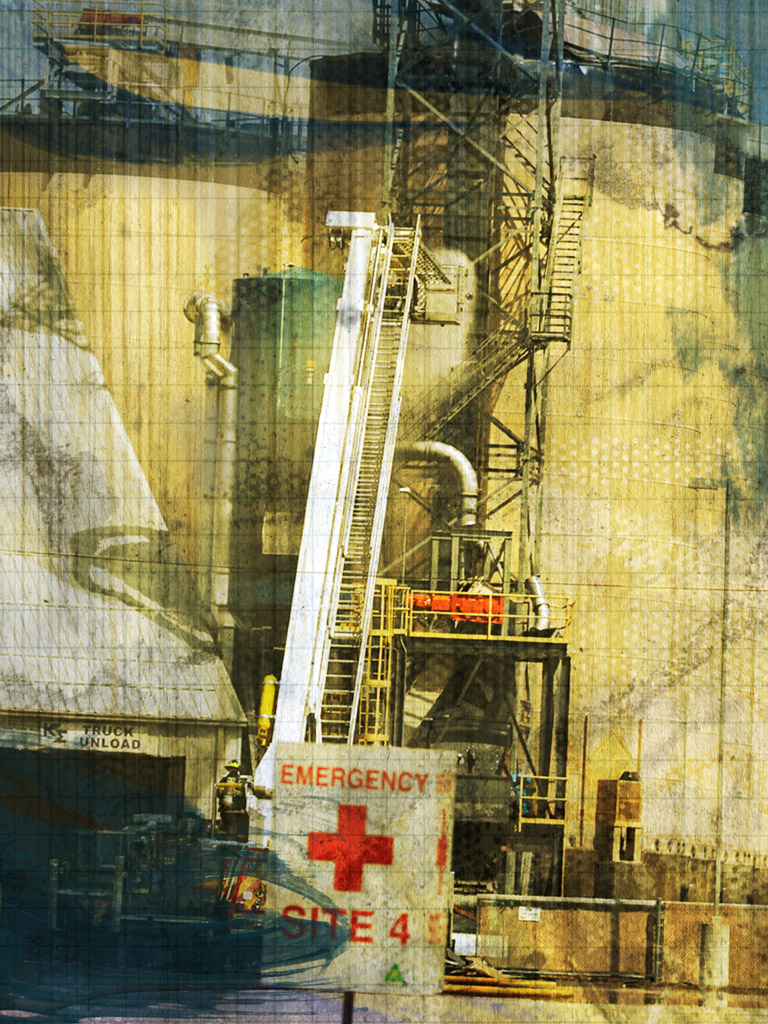

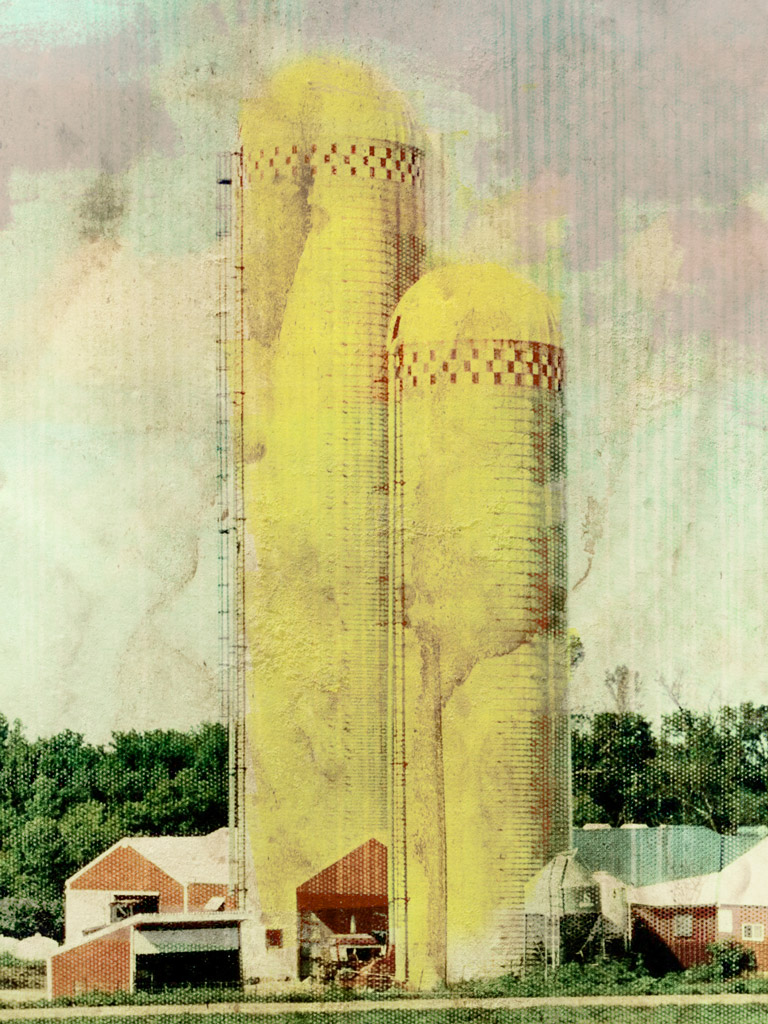

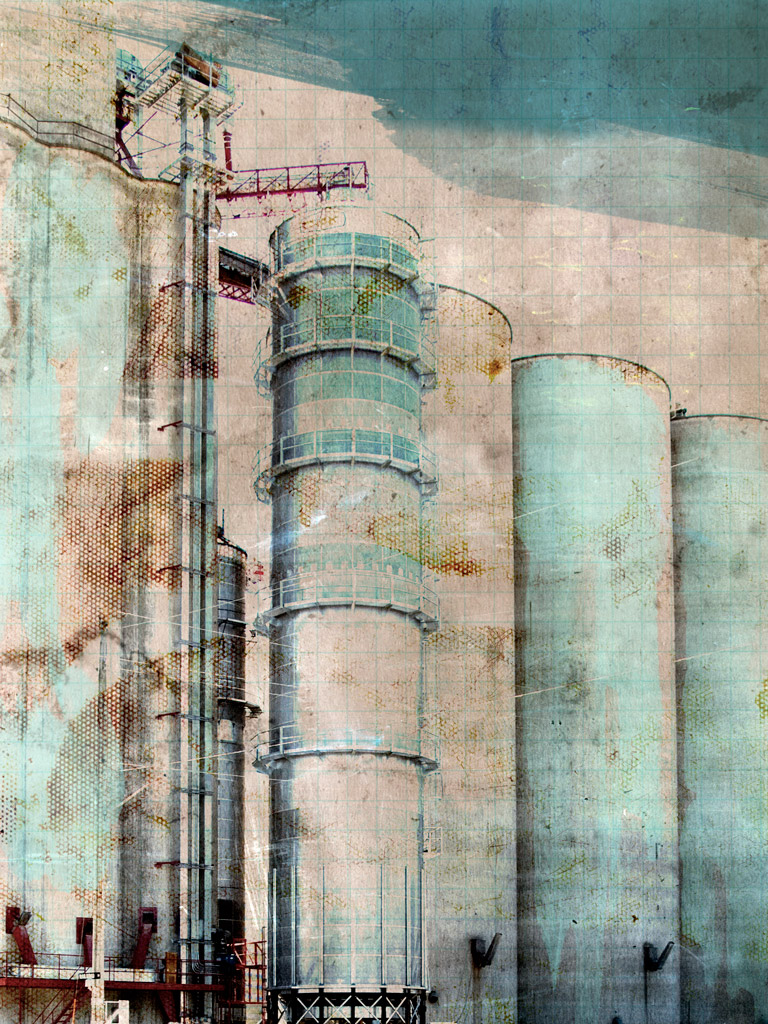

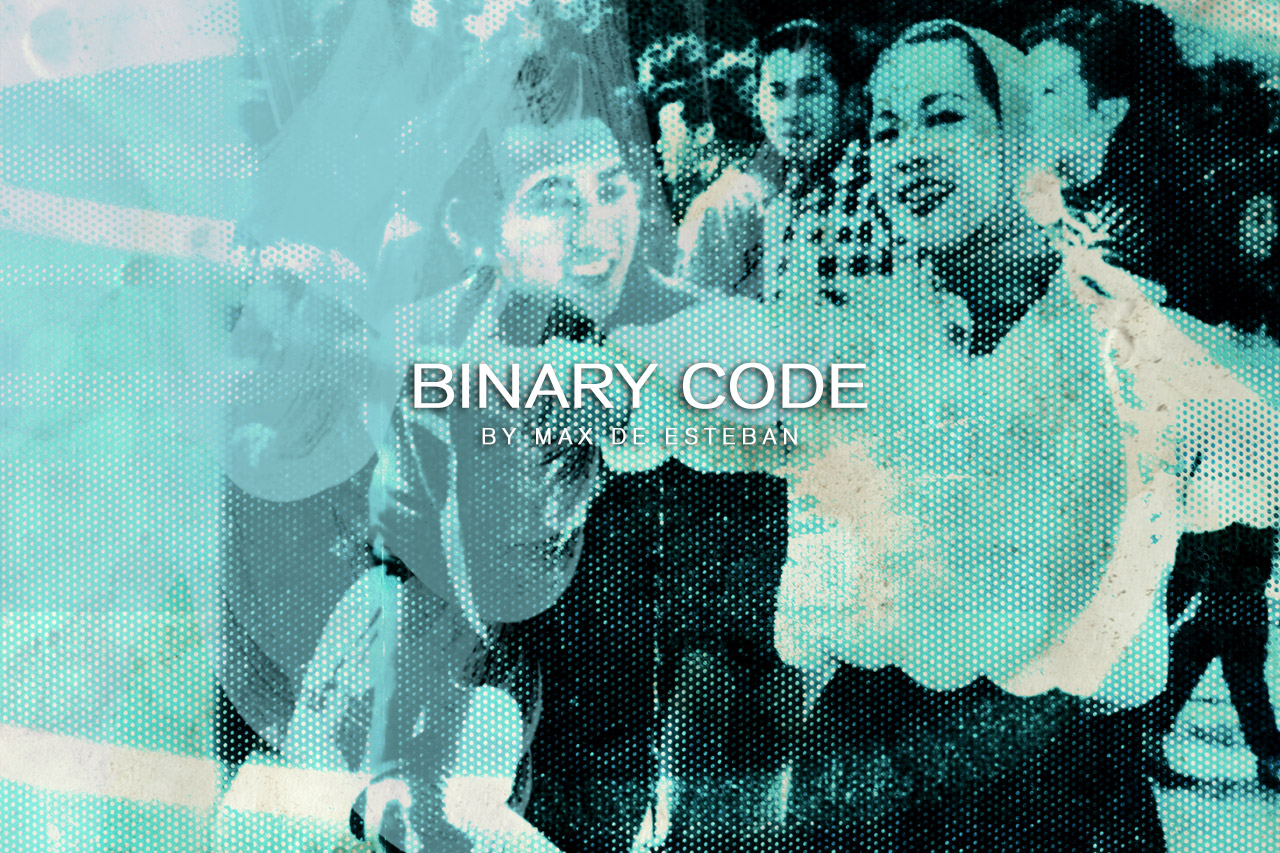

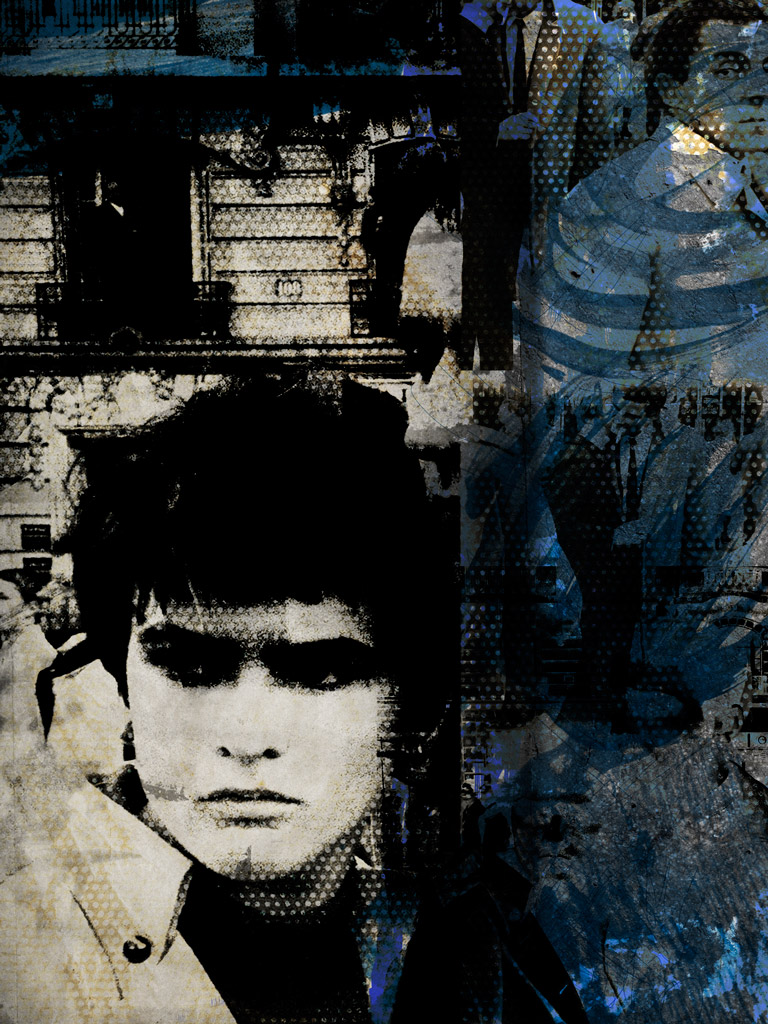

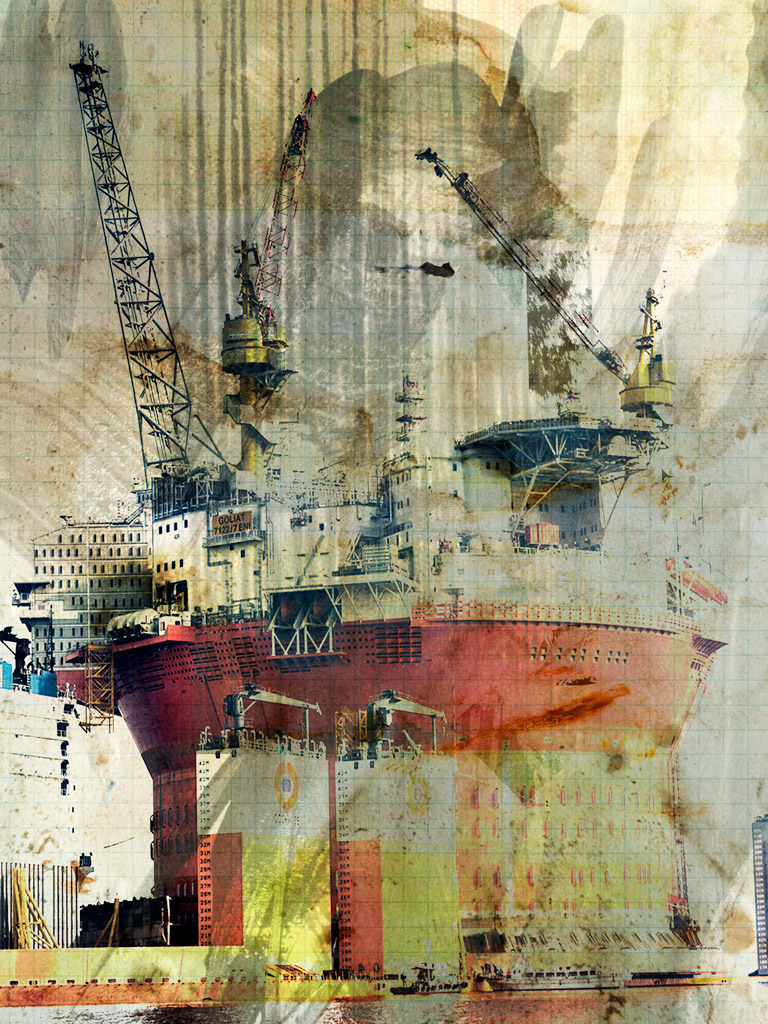

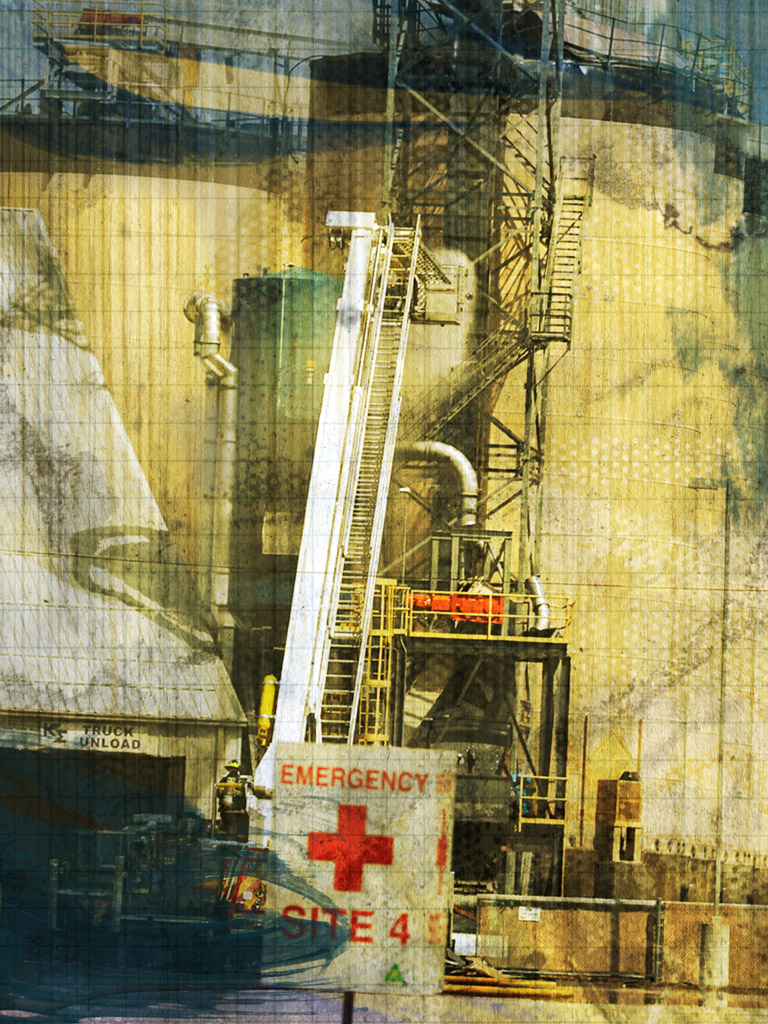

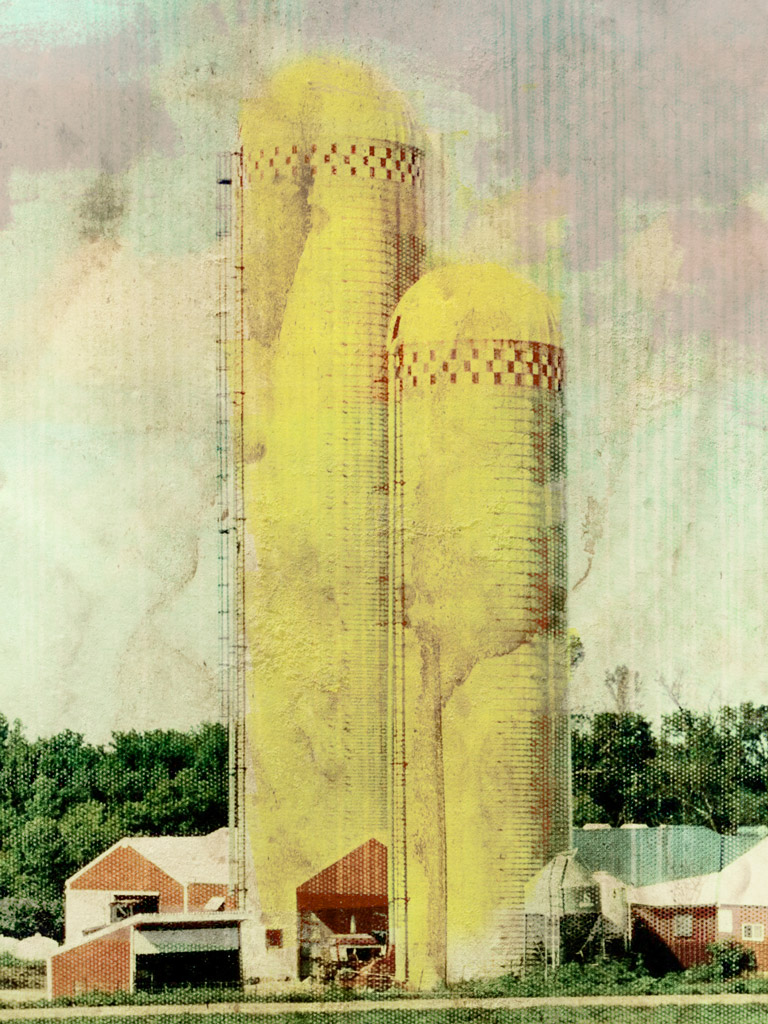

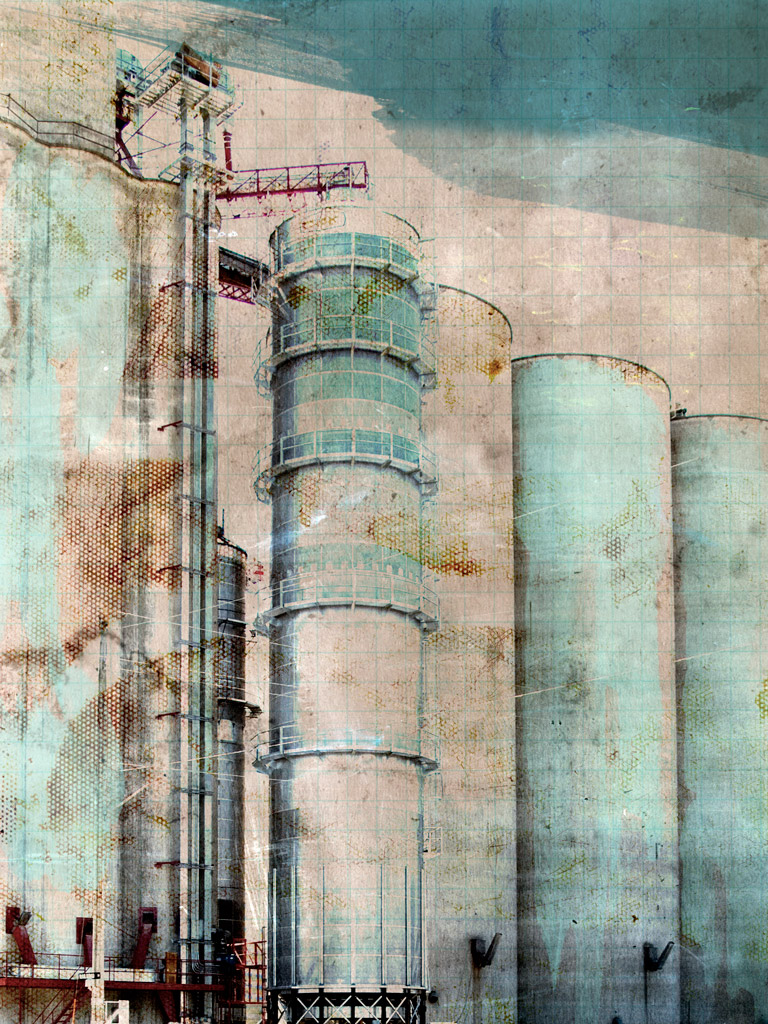

My latest project, called Binary Code, attempts to give visual expression to a world where databases and algorithms determine the ultimate reality, including nature. This is essentially the end of the order of nature as we know it.

And for some reason I can’t explain, the whole series consists of images of women and industrial silos. It could be because my files are full of these images which I have always found fascinating although I could also be trying to justify it as the end of a fundamental symbol where the woman and uterus are no longer relevant symbols for representing fertility, reproduction, beauty or nature.

I would like to comment on an aspect that is important for me. The criteria on the basis of which the artist selects an “appropriate” object may vary but the relationship between artist and subject is never univocal. The artist is only one of the parts. The object rebels and fights for its real nature, reacting to manipulation and boycotting it. The sign-object maintains some of its original nature, however much it fights against it. I think this negotiation between idea and reality is what makes appropriation so interesting.

ZZ. How does having sources with such diverse origins affect the narrative and timing of your images?

M. Nothing has different origins. Our only access to reality is mathematics, and quantum physics has eliminated time as an explanatory element for the behavior of elementary particles. Stripping photography of narrative and temporality is a lofty and necessary goal.

Narrative and temporality can be analyzed from many perspectives. For example, for Cyborg art, time is irrelevant because it can accumulate and eliminate modifications from its code indefinitely, meaning that there is no original or copy. Another less visionary example would be the way we experience the Internet today, jumping from one hyperlink to another, breaking up the original narrative structure of a text. Narrative as a mechanism and source of truth only continues to operate in Hollywood.

But it is a complex topic, because with narrative and temporality, what we are talking about is the issue of meaning. Refuting narrative entails resisting a set meaning that permits redemption (here I am referring to Adorno’s famous essay on Beckett). Eluding narrative prevents access to the comfortable world of history and fable.

In Binary Code there is no narrative. There are simply visual objects seeking to reclaim their meaning in their material specificity. Binary code, from its maximum abstraction, creates objects whose significance is drawn from its materiality rather than the code. The disenchantment of modern nature, its non-meaning, does not prevent nature from speaking through our bodies, desires, suffering and needs. By reclaiming the object, this project calls for a return to aesthetic materialism (albeit in an updated form).

If you think about it for a moment, it may also be time to reclaim the Aztec god Ometeotl as a contemporary symbol. Ometeotl, the immanent, invisible and immaterial god who had no temple, is the creator of all dualities (and therefore predates them): time and space, male and female, day and night, matter and spirit, zero and one. He is the creator of everything. Ometeotl is the binary code.

Max de Esteban (Spain). A fine-art photographer. Holds a Graduate degree from UPC, a Master from Stanford University and a PhD from URL. He is a Fulbright Alumni. His work is organized in two distinct bodies: Elegies of Manumission and Propositions. Awards: the 2010 National Award of Professional Photography (Spain)- Gold LUX.[2] and Grand Prix Jury's Special Award, Fotofestiwal 2010, Poland.

Max de Esteban (Spain). A fine-art photographer. Holds a Graduate degree from UPC, a Master from Stanford University and a PhD from URL. He is a Fulbright Alumni. His work is organized in two distinct bodies: Elegies of Manumission and Propositions. Awards: the 2010 National Award of Professional Photography (Spain)- Gold LUX.[2] and Grand Prix Jury's Special Award, Fotofestiwal 2010, Poland.

ZZ. What led you to appropriation and remix and how are they significant in your work?

M. Appropriation and remix have a long artistic tradition, beginning with Picasso’s collages. As early as the 1920s, Hannah Hoch and the Dadaists used this mode of expression to create major photographic works. In music, for example, from today’s DJs and Pop to Glenn Gould and Miles Davis, the practice of remix, collage and appropriation has been an essential part of their production. What I mean is that as an artistic concept, appropriation and remix are pretty standard and not particularly groundbreaking.

The interesting question is why their aesthetic power has been reasserted in photography precisely now. And I think one possible answer would be the combination of the formal exhaustion of the linear perspective as a photographic representation of the world and the huge impact digitization is having on every aspect of our lives. I would answer your question by turning it around and saying I find it hard to think of a truly relevant form of photography for the world we live in that continues to respect the Eurocentric, reactionary structure of the dark room.

ZZ. What do you mean by Eurocentric and reactionary?

M. The linear perspective, the visual structure resulting from the dark room, is a very particular and ideological way of visualizing the world. Panofsky has a text about it he wrote in 1927, a real classic, that is a pleasure to read.

But what is really remarkable is that it is an exception in art history. In 10,000 years of history, the linear perspective spans only 500 years and is located exclusively in the West. It has never been of interest to Asian, or pre-Columbian or African art ... it is a European way of seeing in a period beginning in the Renaissance and ending in the 19th century.

And this is no coincidence because its ideological content is well known. The linear perspective arranges the world from the point of view of an autonomous individual whose individuality is the world’s principle of meaning. It is pure Descartes. And we all remember Descartes’ Fifth Meditation, which states that since the essence of matter is its extension, geometry is an essential instrument for understanding nature. Modernity can be defined as the advance of abstraction and the prevalence of the quantitative over the qualitative in which the mathematical-scientific order is regarded as the only source of valid knowledge. There is so much contemporary thought that debunks this narrative that I won't repeat it here.

Thus, surprisingly, my earlier comment is still valid. Why should digital photography continue giving priority to a functionally and ideologically devalued visual structure?

ZZ. Why do you think digital photography changes the way we understand appropriation and remix?

M. Digital technologies are leading us towards the radical transformation of our world. By replacing the industrial economy with a bio-cybernetic system, digitization is modifying our environment, our subjectivity and soon, our bodies. This is the technological phenomenon that will define our era and therefore our culture.

Unlike an analog file, a digital file is invisible. It is a code whose visual expression is a translation highly mediated by default algorithms, whose most prominent feature is precisely its immateriality.

This technical structure fits our current era of abstraction and non-referentiality and the digital financialization of the economy. How do we see the world today? We have the answer on our computer and Smartphone screens. What is the essential aspect of the financial economy? The recombination of existing information units to create new information, in other words, “constructive compositing”. Digitization has definitively invalidated linear narrative, the monocular perspective and the author’s “authority”.

ZZ. You attach a great deal of importance to the concept of technology in your work. Could you explain why?

M. We are moving towards a world as a “technological whole”. Technical manipulation has already invaded our bodies, the last frontier, and no-one doubts that having machines inside our bodies will soon become commonplace.

The cyborg raises more complex issues for our species, which, though somewhat deteriorated, continues to maintain the autonomy of the subject as an essential value. Abstraction, digitization and cyborg are three sides of the same coin that heralds our new world, whether we like it or not. In my opinion, reflecting on technology is necessary, urgent and politically essential.

ZZ. And how do you think technology affects the practice of photography?

M. I’d like to point something out. One of the problems of photography is the confusion between technology and use. Writing is a communication technology that serve to draw up a commercial contract and compose a poem by Virgil. It is the same technology but nobody would ever mistake Virgil for a notary. In photography, we tend to combine uses, which creates enormous confusion in critical discourse. Throughout this interview, I have been referring to the use of photography as a means of artistic expression.

The thing is that photography has always been halfway to a cyborg. It is a machine that affects and to some extent determines human power, thought and expression and is therefore an ideal place for reflecting on the issues I mentioned earlier.

To give you an example: How can you visually depict the abstraction of the economy when the material references of wealth have been replaced by a binary code? That’s what I’m doing at the moment and it forces me to rethink what “representation” means in this new visual regime.

Another example: How does the idea of the cyborg affect art categories? That’s the topic I try to get my teeth into in the text “Cyborg Art: art in the bio-cybernetic era”. And there are a thousand other possible ideas that make photography an exciting medium at this particular historical time. The point is that if photographic practice does not take up the challenge raised by contemporaneity, it will be relegated to banality and antique shops.

ZZ. How do you choose the sources you use and what significance do they have for your series?

M. Like nearly everything in life, it is a combination of determination and chance. In my case, too much planning and/or reflection in my work paralyzes me while dreams or rather daydreams are of paramount importance.

My latest project, called Binary Code, attempts to give visual expression to a world where databases and algorithms determine the ultimate reality, including nature. This is essentially the end of the order of nature as we know it.

And for some reason I can’t explain, the whole series consists of images of women and industrial silos. It could be because my files are full of these images which I have always found fascinating although I could also be trying to justify it as the end of a fundamental symbol where the woman and uterus are no longer relevant symbols for representing fertility, reproduction, beauty or nature.

I would like to comment on an aspect that is important for me. The criteria on the basis of which the artist selects an “appropriate” object may vary but the relationship between artist and subject is never univocal. The artist is only one of the parts. The object rebels and fights for its real nature, reacting to manipulation and boycotting it. The sign-object maintains some of its original nature, however much it fights against it. I think this negotiation between idea and reality is what makes appropriation so interesting.

ZZ. How does having sources with such diverse origins affect the narrative and timing of your images?

M. Nothing has different origins. Our only access to reality is mathematics, and quantum physics has eliminated time as an explanatory element for the behavior of elementary particles. Stripping photography of narrative and temporality is a lofty and necessary goal.

Narrative and temporality can be analyzed from many perspectives. For example, for Cyborg art, time is irrelevant because it can accumulate and eliminate modifications from its code indefinitely, meaning that there is no original or copy. Another less visionary example would be the way we experience the Internet today, jumping from one hyperlink to another, breaking up the original narrative structure of a text. Narrative as a mechanism and source of truth only continues to operate in Hollywood.

But it is a complex topic, because with narrative and temporality, what we are talking about is the issue of meaning. Refuting narrative entails resisting a set meaning that permits redemption (here I am referring to Adorno’s famous essay on Beckett). Eluding narrative prevents access to the comfortable world of history and fable.

In Binary Code there is no narrative. There are simply visual objects seeking to reclaim their meaning in their material specificity. Binary code, from its maximum abstraction, creates objects whose significance is drawn from its materiality rather than the code. The disenchantment of modern nature, its non-meaning, does not prevent nature from speaking through our bodies, desires, suffering and needs. By reclaiming the object, this project calls for a return to aesthetic materialism (albeit in an updated form).

If you think about it for a moment, it may also be time to reclaim the Aztec god Ometeotl as a contemporary symbol. Ometeotl, the immanent, invisible and immaterial god who had no temple, is the creator of all dualities (and therefore predates them): time and space, male and female, day and night, matter and spirit, zero and one. He is the creator of everything. Ometeotl is the binary code.

Max de Esteban (Spain). A fine-art photographer. Holds a Graduate degree from UPC, a Master from Stanford University and a PhD from URL. He is a Fulbright Alumni. His work is organized in two distinct bodies: Elegies of Manumission and Propositions. Awards: the 2010 National Award of Professional Photography (Spain)- Gold LUX.[2] and Grand Prix Jury's Special Award, Fotofestiwal 2010, Poland.

Max de Esteban (Spain). A fine-art photographer. Holds a Graduate degree from UPC, a Master from Stanford University and a PhD from URL. He is a Fulbright Alumni. His work is organized in two distinct bodies: Elegies of Manumission and Propositions. Awards: the 2010 National Award of Professional Photography (Spain)- Gold LUX.[2] and Grand Prix Jury's Special Award, Fotofestiwal 2010, Poland.Lei Lei + Thomas Sauvin

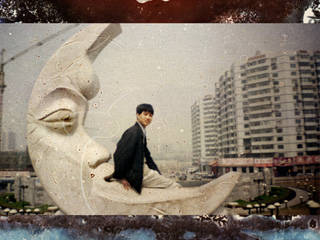

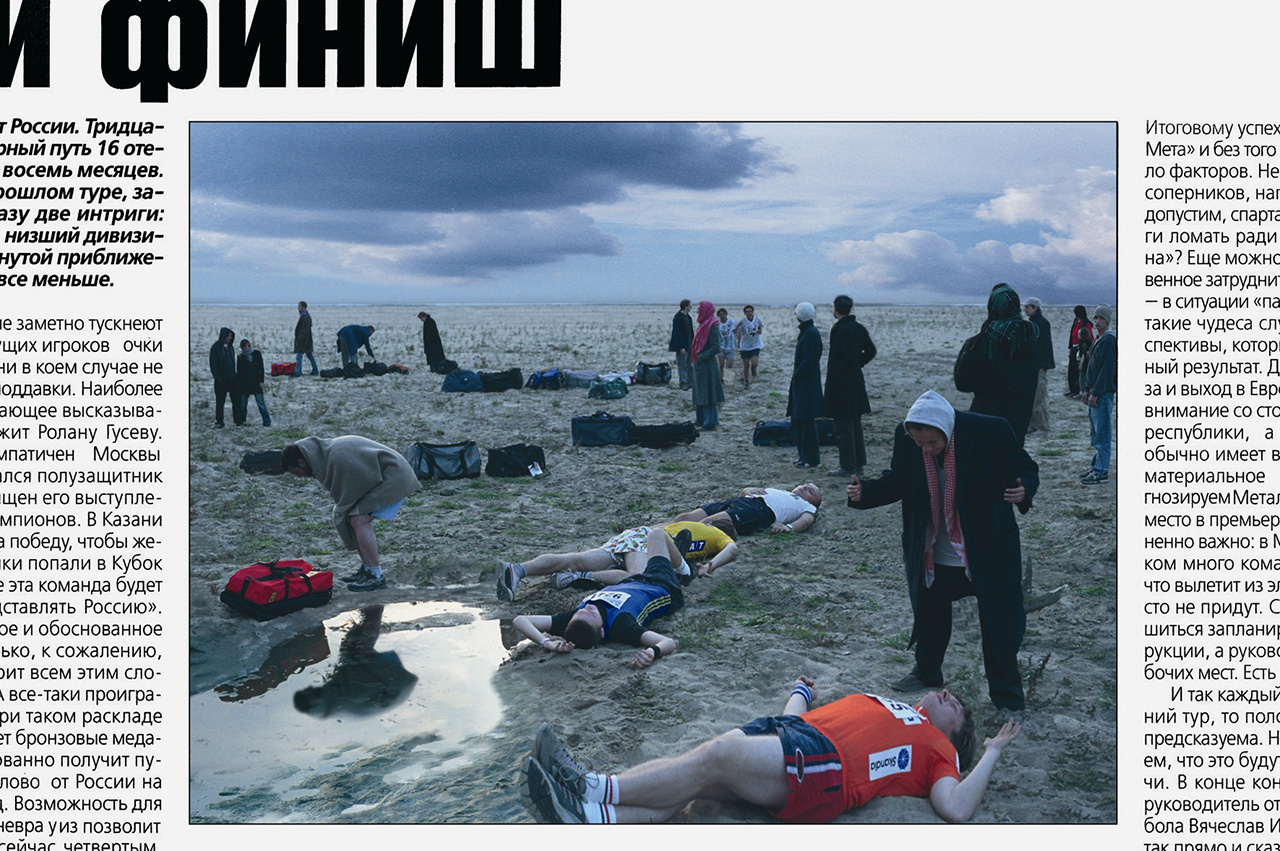

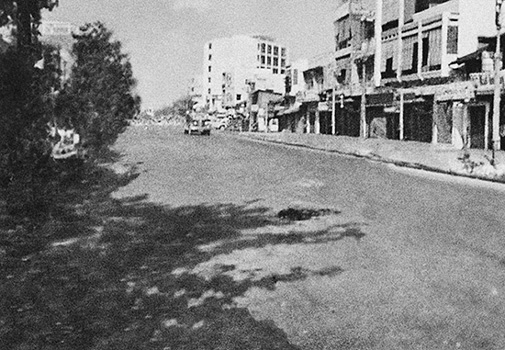

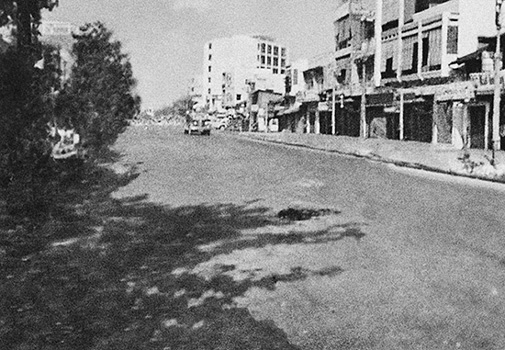

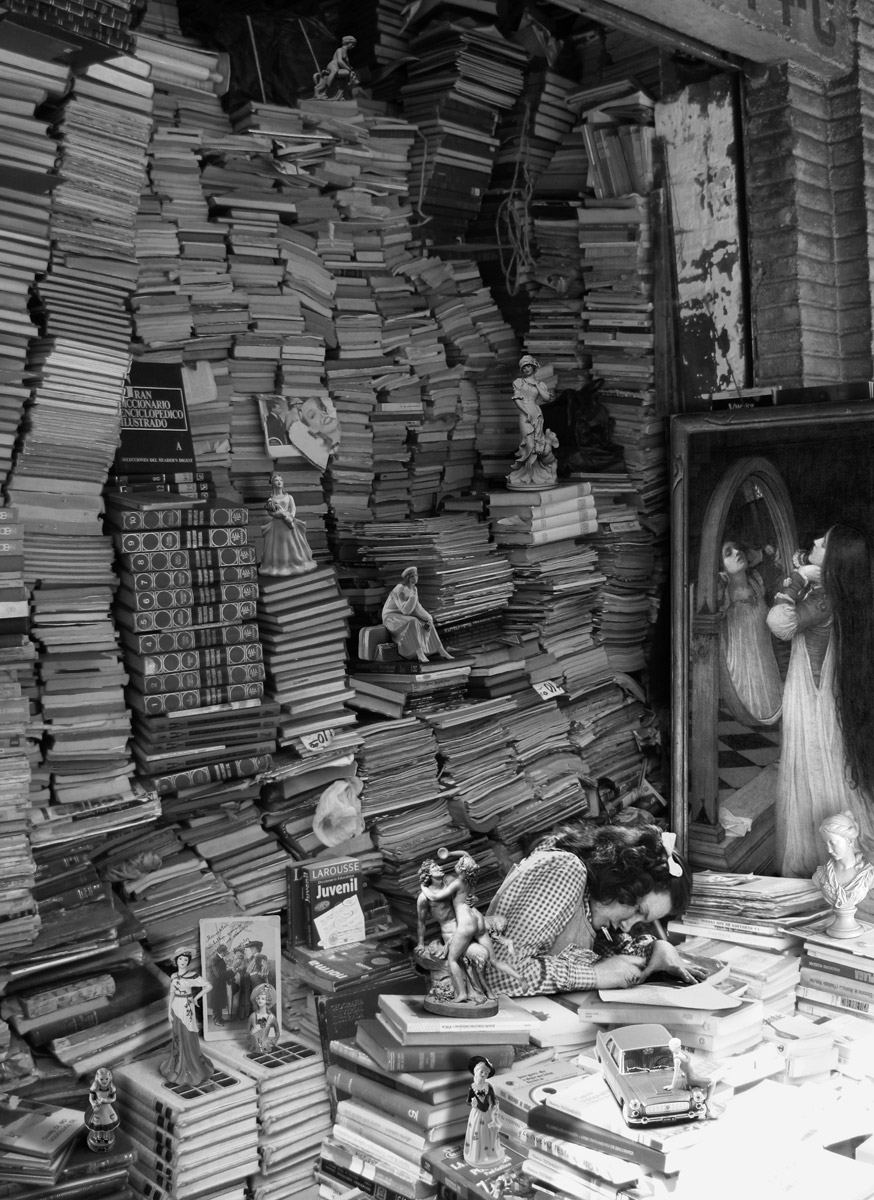

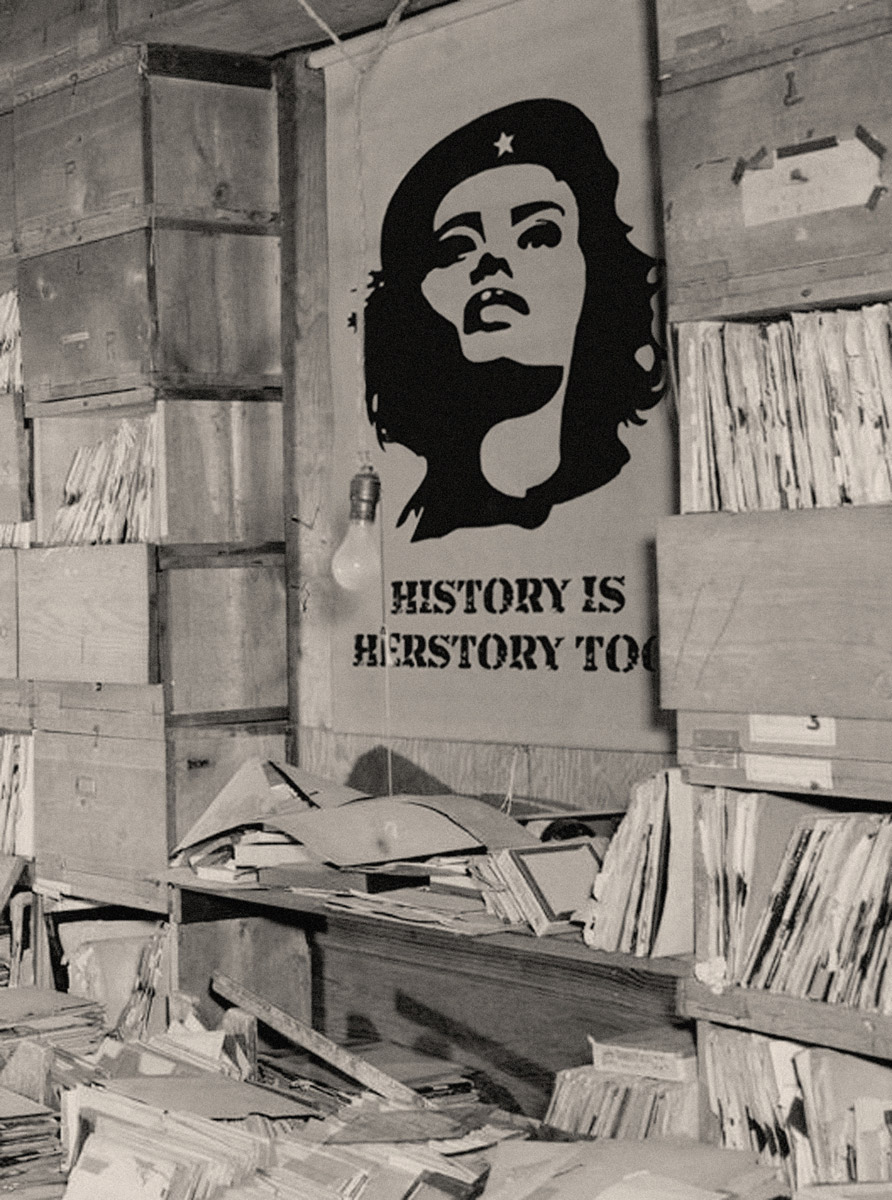

Beijing Silvermine is a project by french photographer Thomas Sauvin to recover the photographic records of the people of Beijing after the Cultural Revolution, from 1985 when photography (mainly 35 mm) became popular in China, until about 2005, when it began to give way to digital photography.

For several years, Sauvin collected negatives (many of them never printed), recovered from a recycling plant on the outskirts of Beijing. After an exhaustive selection and digitization, he has created a fascinating archive with over half a million 35 mm negatives that has become an intriguing record of the public and private lives of the inhabitants of that city. Over the past 20 years, China has experienced unprecedented economic liberalization, which has completely redefined the way people in its cities thrive, travel, eat and enjoy themselves.

This collection of material from anonymous sources has served as the input for editing a collection of photo books and exhibitions, in which Sauvin provides an authorial contribution to the reinterpretation of a form of appropriation, which has even been the starting point for collaborative pieces such as the animation by chinese visual artist Lei Lei, who selected 3,000 of these images to create an audiovisual piece entitled precisely Recycled in 2013. Director Emiliad Guillermine produced a short documentary that bears witness to Sauvin’s experience and his meticulous collection, sorting, editing and digitization of the thousands of images he recovered.

Thus, Sauvin’s work brings us closer to part of the collective memory of current Chinese society, enabling us to understand how it has changed its cultural dynamics in recent years, while providing a new perspective on the experience of the visual appropriation and recycling at a time when the mass production and consumption of images leads us to understand the importance, but above all the enormous authorial possibilities of the editor and curator to generate new discourses.

Thomas Sauvin (Francia) A photography collector and editor who lives in Beijing. Since 2006 he exclusively works as a consultant for the UK-based Archive of Modern Conflict, an independent archive and publisher, for whom he collects Chinese works, from contemporary photography to period publications to anonymous photography. Sauvin has had exhibitions of his work, and published through Archive of Modern Conflict.

Thomas Sauvin (Francia) A photography collector and editor who lives in Beijing. Since 2006 he exclusively works as a consultant for the UK-based Archive of Modern Conflict, an independent archive and publisher, for whom he collects Chinese works, from contemporary photography to period publications to anonymous photography. Sauvin has had exhibitions of his work, and published through Archive of Modern Conflict. Lei Lei (China) An up-and-coming multimedia Chinese animation artist with his hands on graphic design, illustration, short cartoon, graffiti and music also. In 2009 he got a master's degree from Tsinghua University. In 2010, his film This is LOVE was shown at Ottawa International Animation Festival and awarded The 2010 Best Narrative Short. In 2013 his film Recycled was selected by Annecy festival and was the Winner Grand Prix shorts - non-narrative at Holland International Animation Film Festival. In 2014 he is the Jury of Zagreb / Holland International Animation Film Festival. and he was the winner of 2014 asian cultural council grant.

Lei Lei (China) An up-and-coming multimedia Chinese animation artist with his hands on graphic design, illustration, short cartoon, graffiti and music also. In 2009 he got a master's degree from Tsinghua University. In 2010, his film This is LOVE was shown at Ottawa International Animation Festival and awarded The 2010 Best Narrative Short. In 2013 his film Recycled was selected by Annecy festival and was the Winner Grand Prix shorts - non-narrative at Holland International Animation Film Festival. In 2014 he is the Jury of Zagreb / Holland International Animation Film Festival. and he was the winner of 2014 asian cultural council grant.Beijing Silvermine is a project by french photographer Thomas Sauvin to recover the photographic records of the people of Beijing after the Cultural Revolution, from 1985 when photography (mainly 35 mm) became popular in China, until about 2005, when it began to give way to digital photography.

For several years, Sauvin collected negatives (many of them never printed), recovered from a recycling plant on the outskirts of Beijing. After an exhaustive selection and digitization, he has created a fascinating archive with over half a million 35 mm negatives that has become an intriguing record of the public and private lives of the inhabitants of that city. Over the past 20 years, China has experienced unprecedented economic liberalization, which has completely redefined the way people in its cities thrive, travel, eat and enjoy themselves.

This collection of material from anonymous sources has served as the input for editing a collection of photo books and exhibitions, in which Sauvin provides an authorial contribution to the reinterpretation of a form of appropriation, which has even been the starting point for collaborative pieces such as the animation by chinese visual artist Lei Lei, who selected 3,000 of these images to create an audiovisual piece entitled precisely Recycled in 2013. Director Emiliad Guillermine produced a short documentary that bears witness to Sauvin’s experience and his meticulous collection, sorting, editing and digitization of the thousands of images he recovered.

Thus, Sauvin’s work brings us closer to part of the collective memory of current Chinese society, enabling us to understand how it has changed its cultural dynamics in recent years, while providing a new perspective on the experience of the visual appropriation and recycling at a time when the mass production and consumption of images leads us to understand the importance, but above all the enormous authorial possibilities of the editor and curator to generate new discourses.

Thomas Sauvin (Francia) A photography collector and editor who lives in Beijing. Since 2006 he exclusively works as a consultant for the UK-based Archive of Modern Conflict, an independent archive and publisher, for whom he collects Chinese works, from contemporary photography to period publications to anonymous photography. Sauvin has had exhibitions of his work, and published through Archive of Modern Conflict.

Thomas Sauvin (Francia) A photography collector and editor who lives in Beijing. Since 2006 he exclusively works as a consultant for the UK-based Archive of Modern Conflict, an independent archive and publisher, for whom he collects Chinese works, from contemporary photography to period publications to anonymous photography. Sauvin has had exhibitions of his work, and published through Archive of Modern Conflict. Lei Lei (China) An up-and-coming multimedia Chinese animation artist with his hands on graphic design, illustration, short cartoon, graffiti and music also. In 2009 he got a master's degree from Tsinghua University. In 2010, his film This is LOVE was shown at Ottawa International Animation Festival and awarded The 2010 Best Narrative Short. In 2013 his film Recycled was selected by Annecy festival and was the Winner Grand Prix shorts - non-narrative at Holland International Animation Film Festival. In 2014 he is the Jury of Zagreb / Holland International Animation Film Festival. and he was the winner of 2014 asian cultural council grant.

Lei Lei (China) An up-and-coming multimedia Chinese animation artist with his hands on graphic design, illustration, short cartoon, graffiti and music also. In 2009 he got a master's degree from Tsinghua University. In 2010, his film This is LOVE was shown at Ottawa International Animation Festival and awarded The 2010 Best Narrative Short. In 2013 his film Recycled was selected by Annecy festival and was the Winner Grand Prix shorts - non-narrative at Holland International Animation Film Festival. In 2014 he is the Jury of Zagreb / Holland International Animation Film Festival. and he was the winner of 2014 asian cultural council grant.Zbigniew Libera

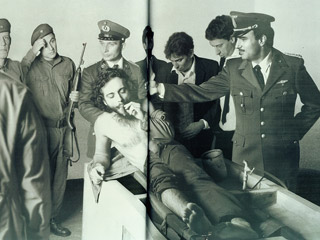

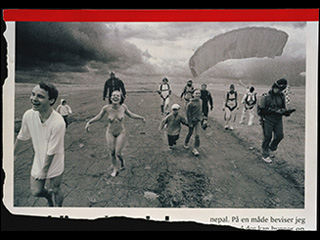

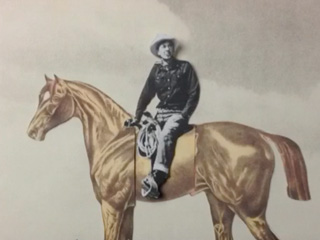

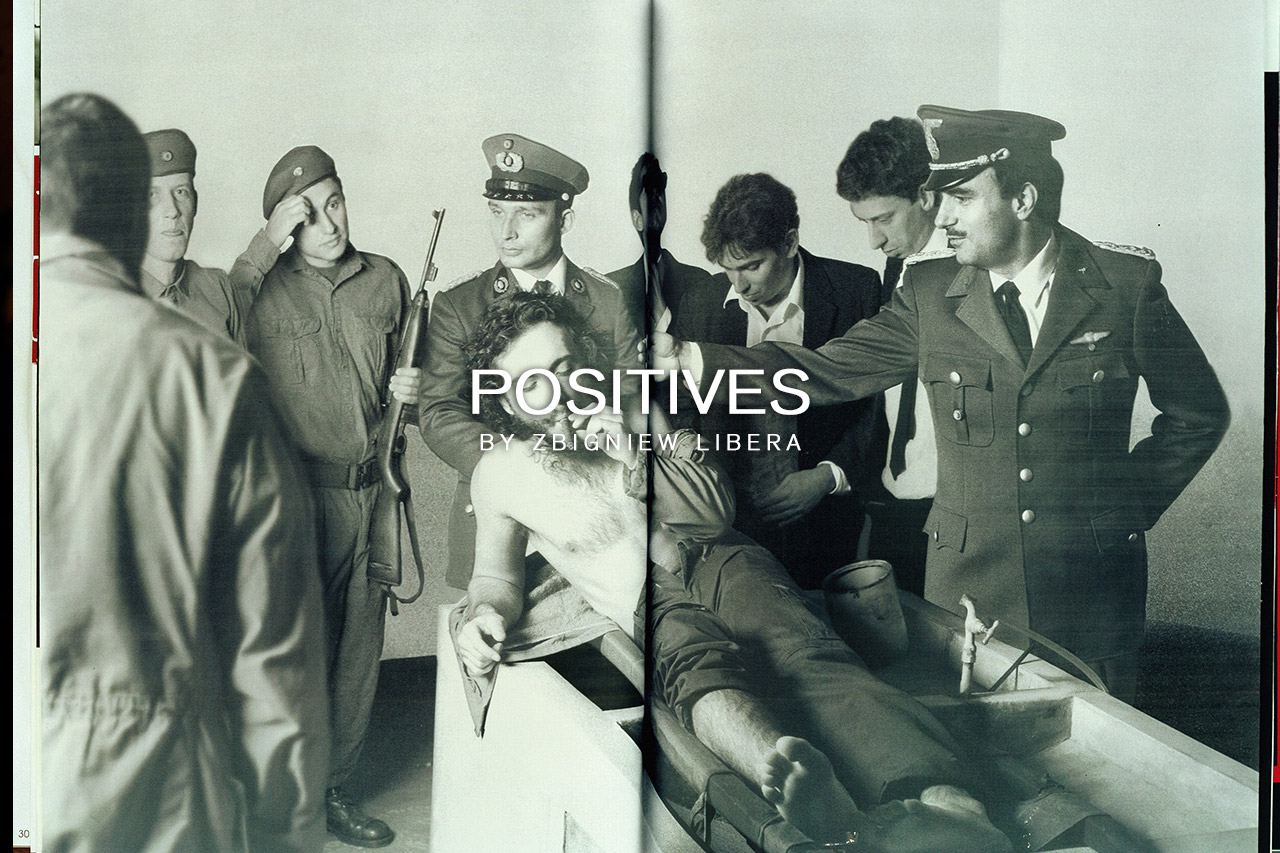

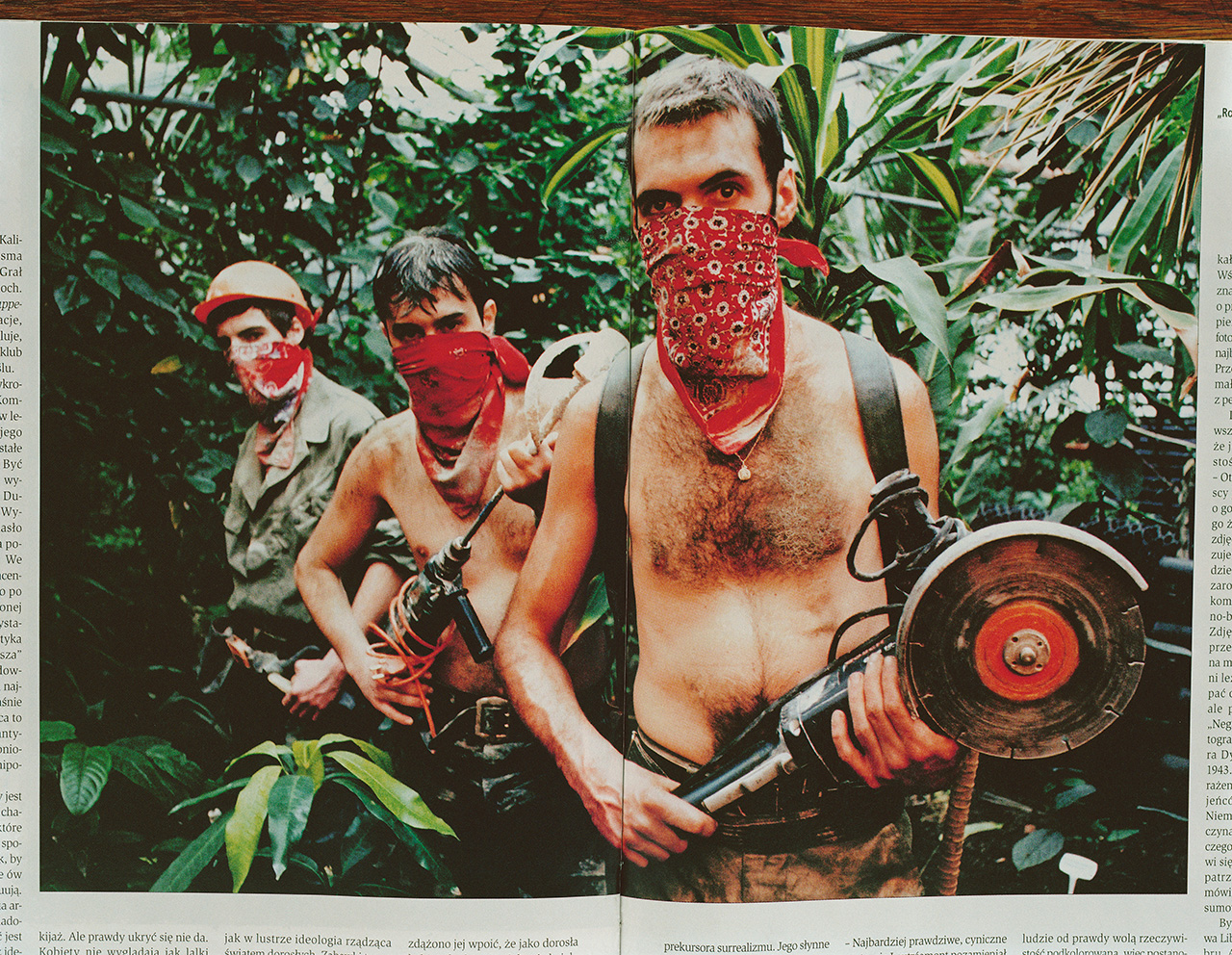

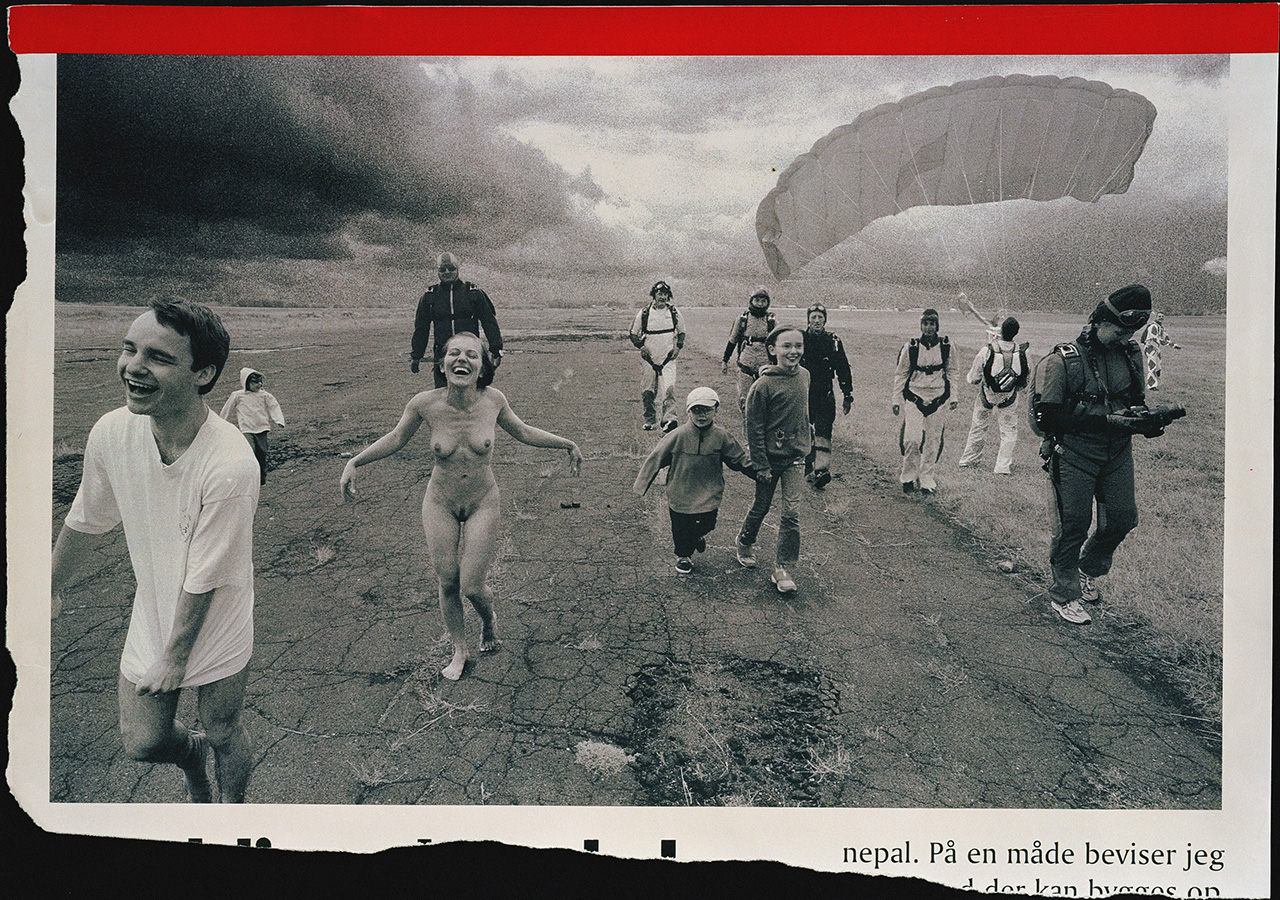

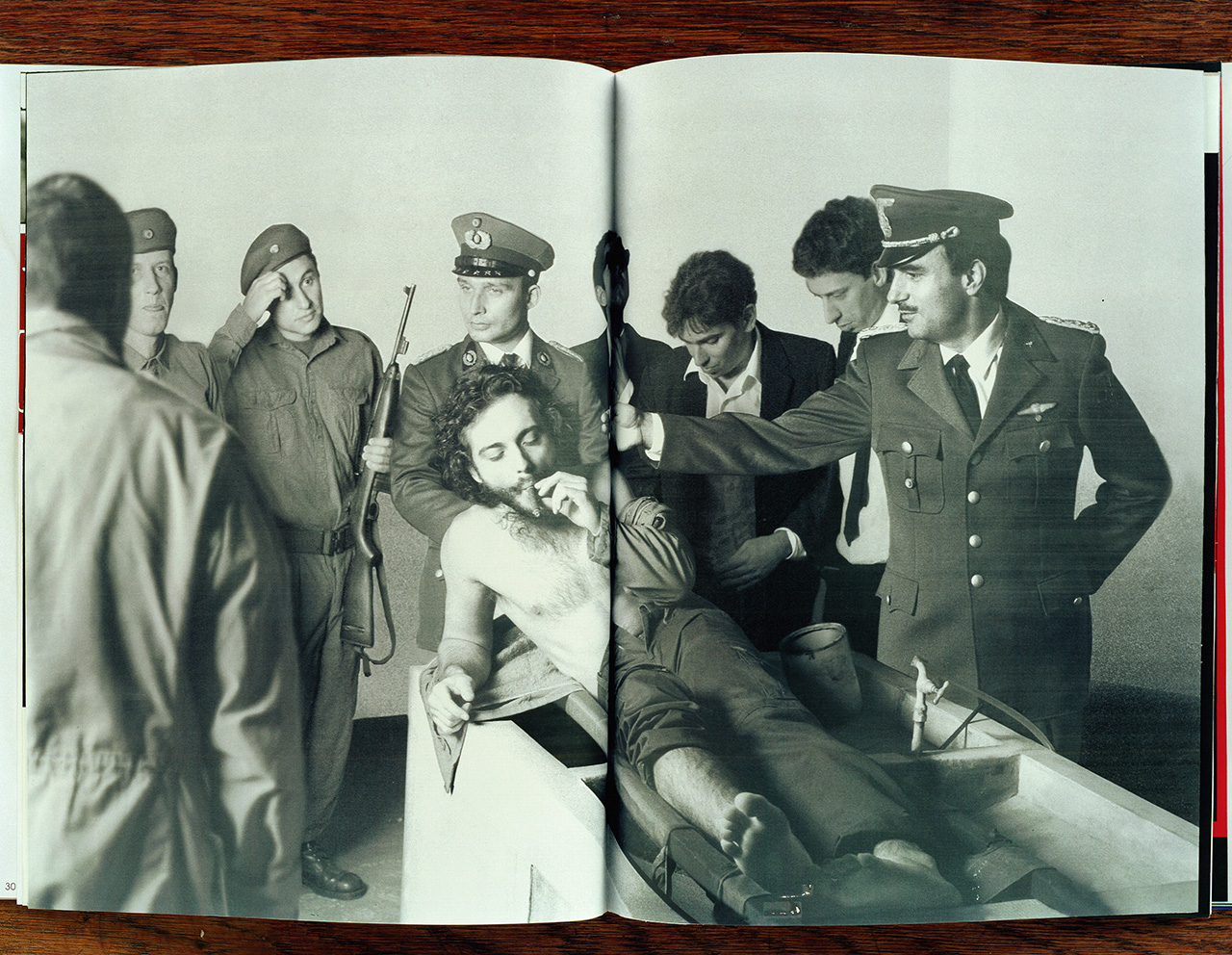

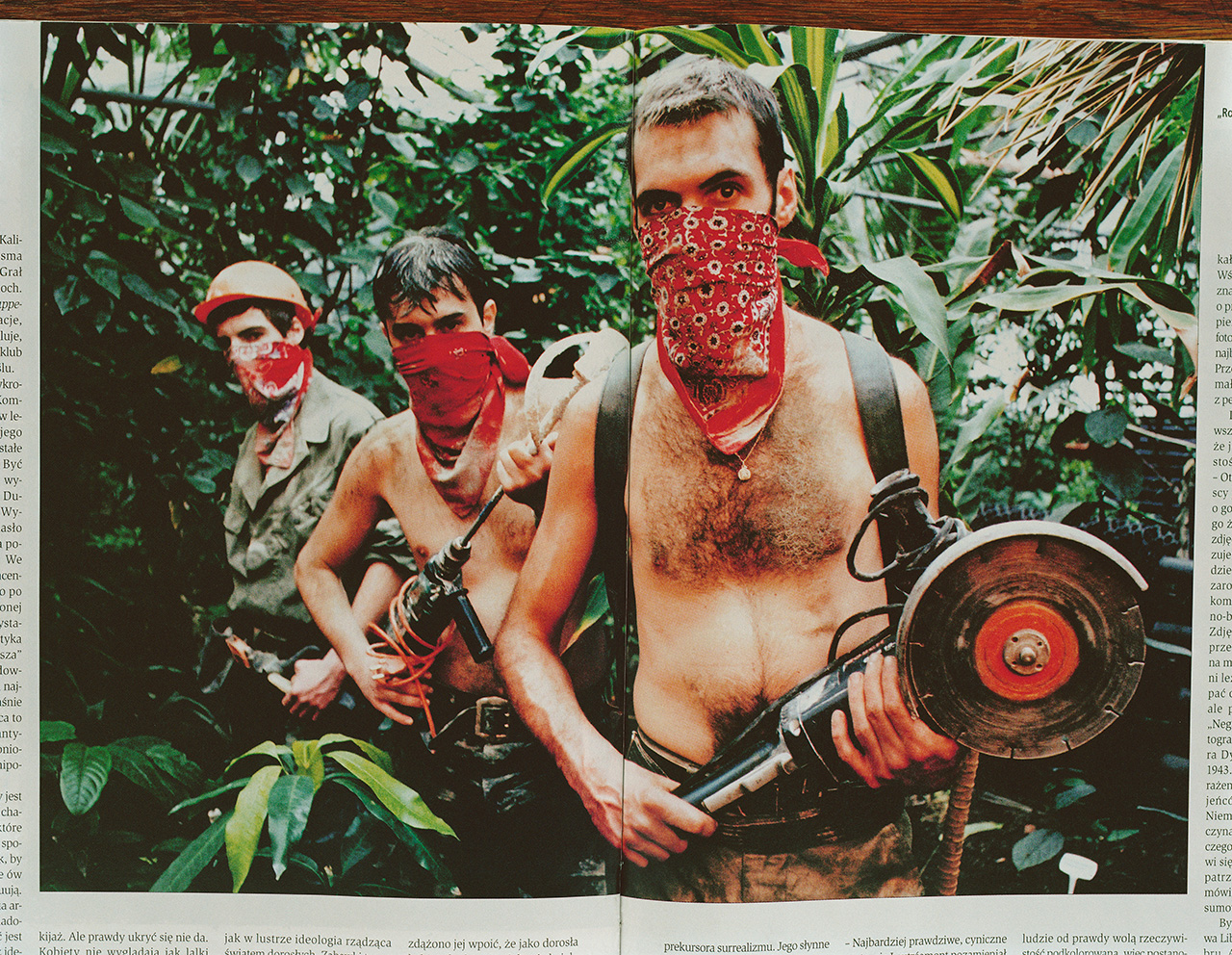

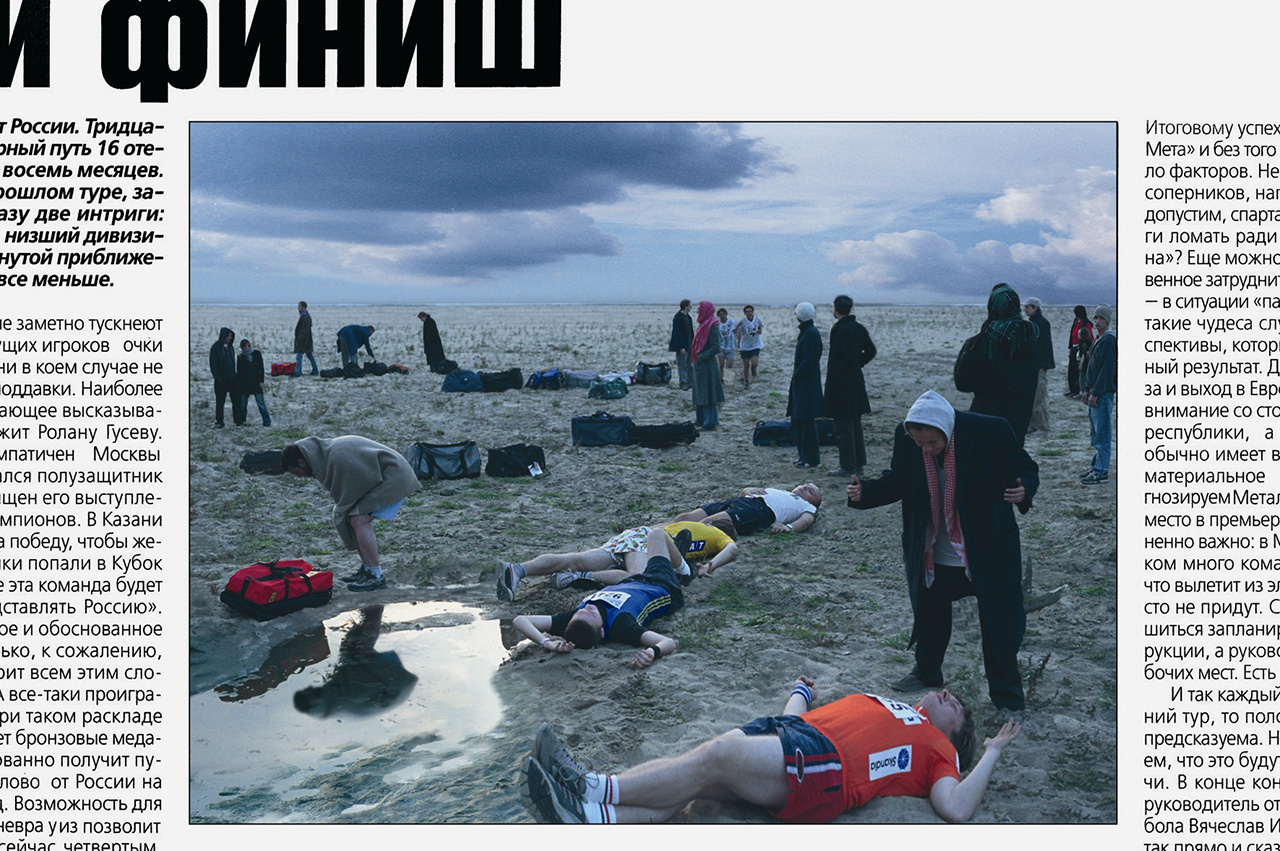

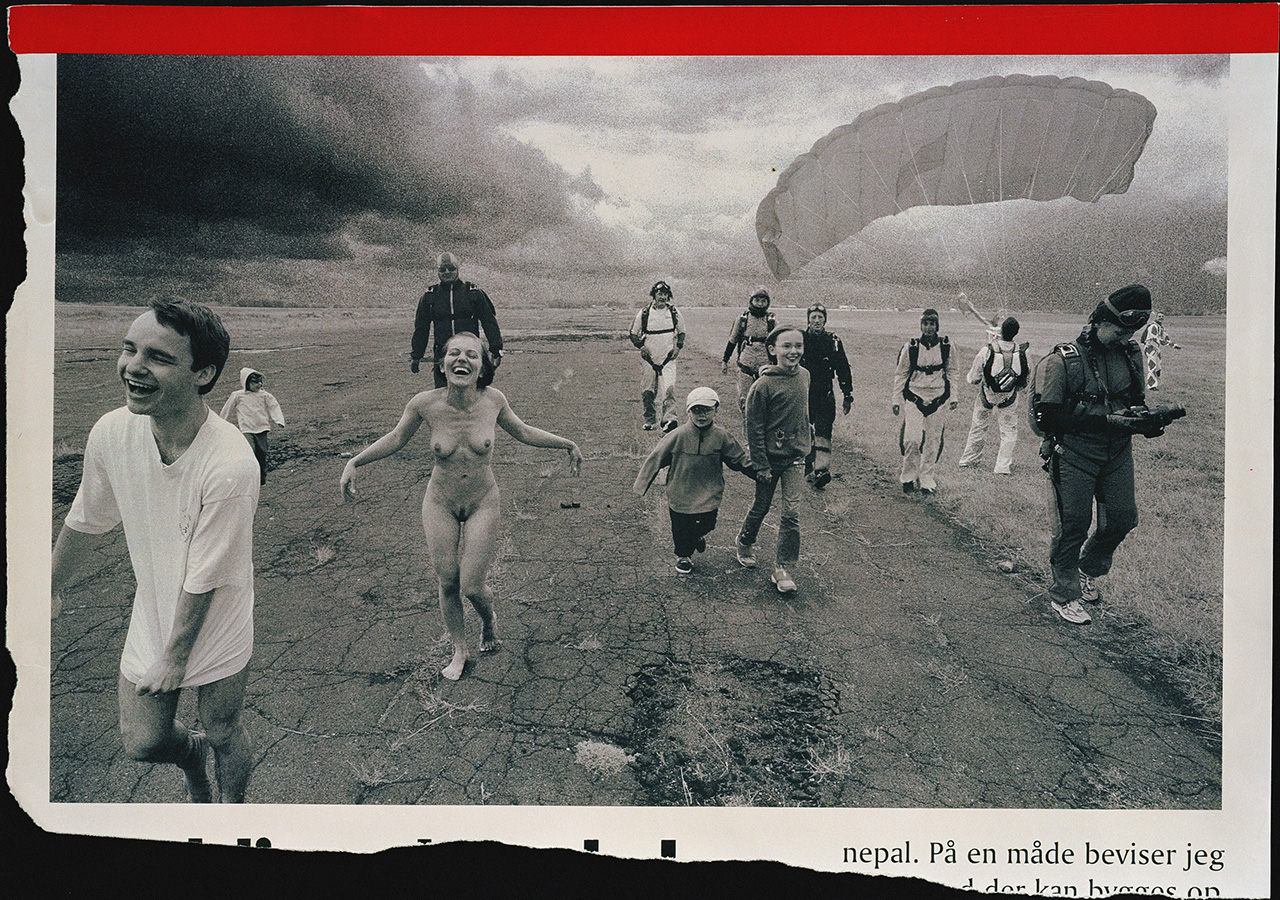

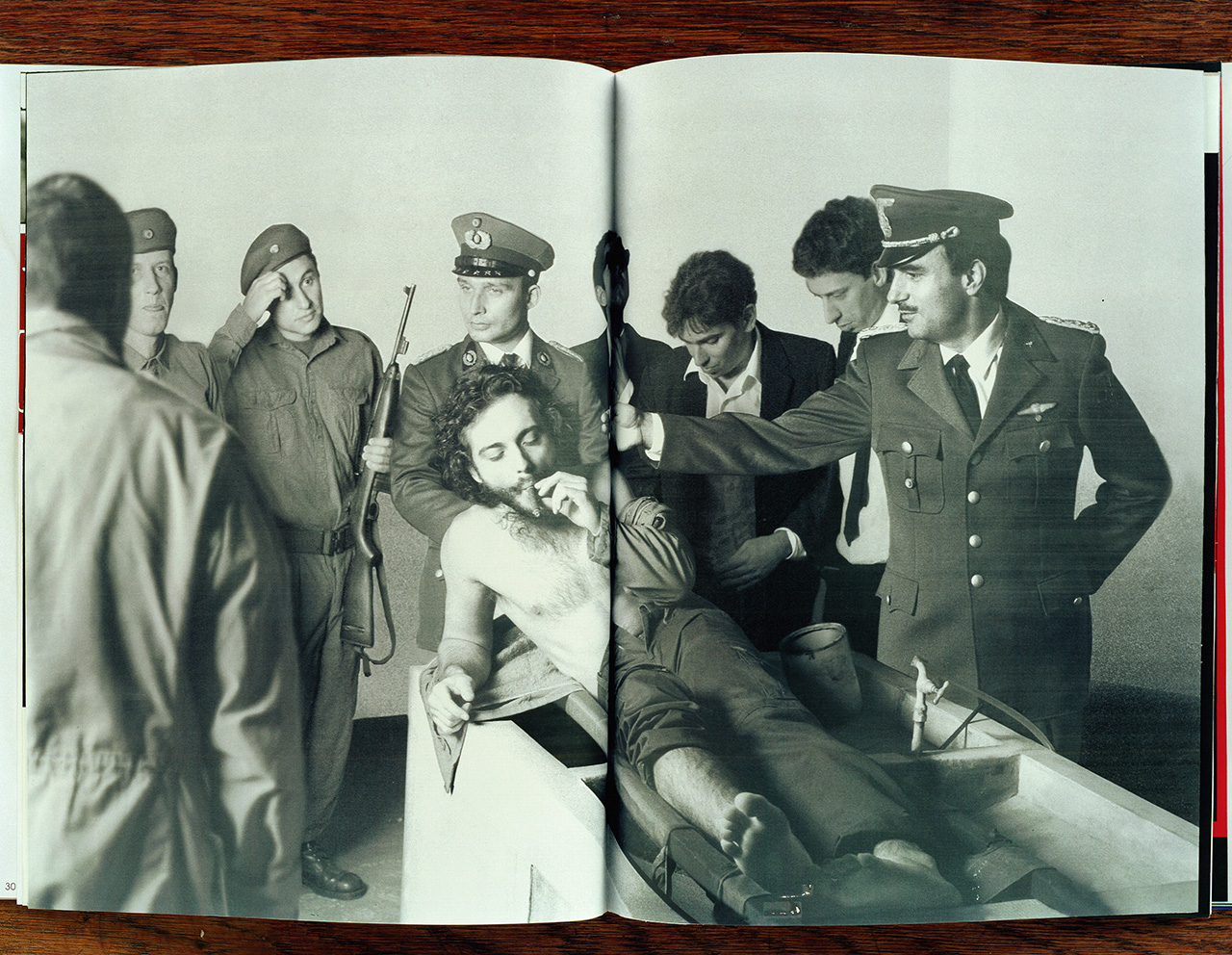

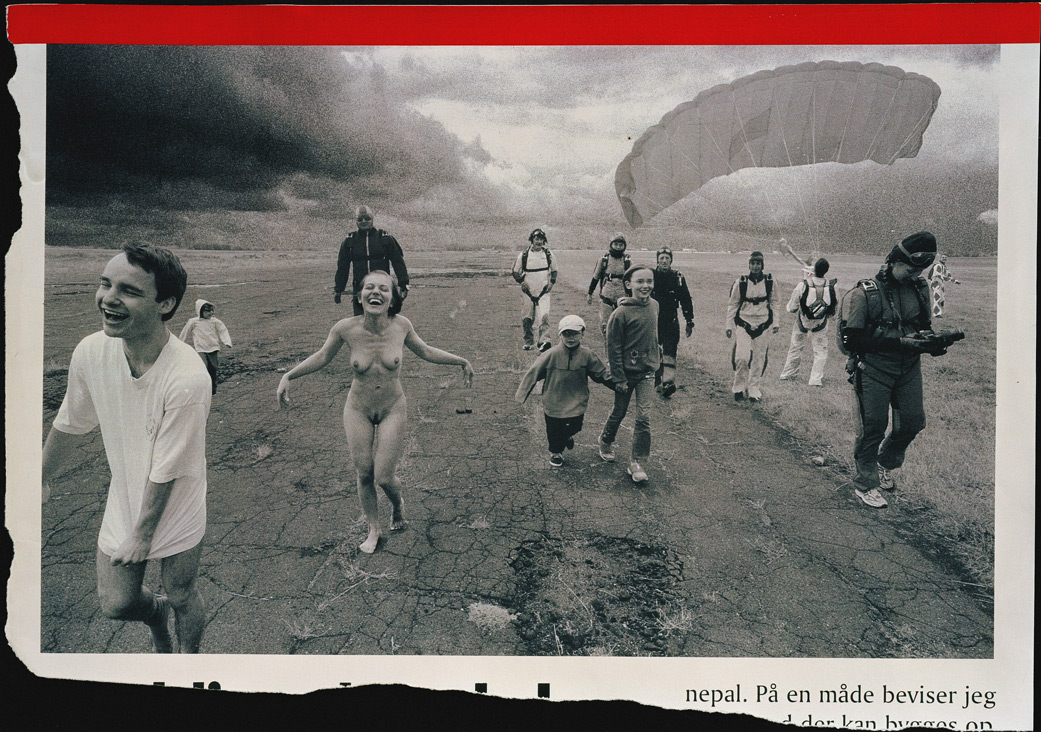

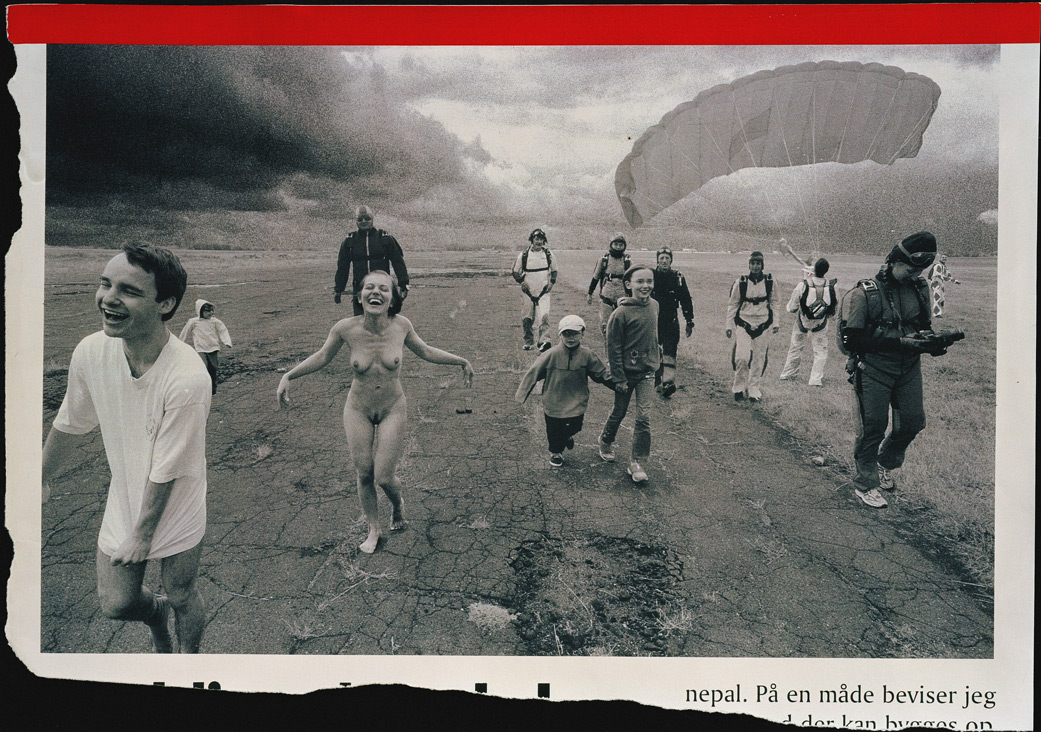

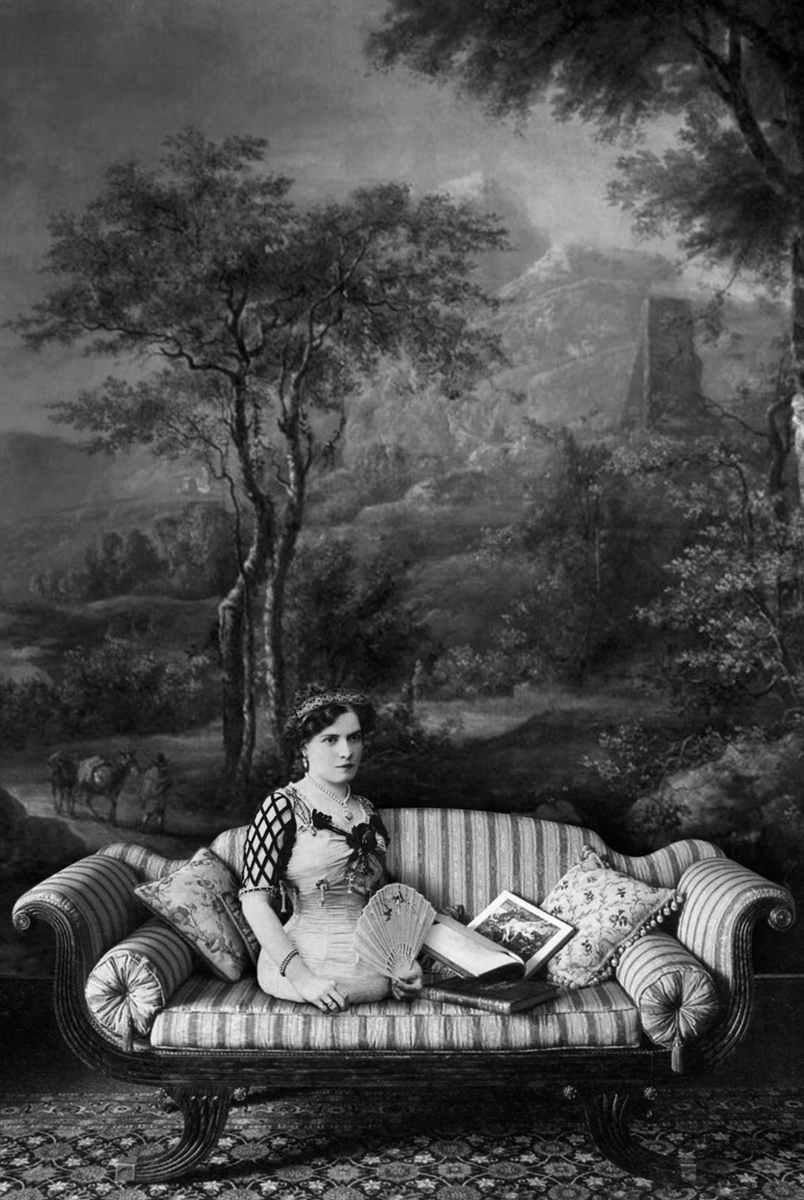

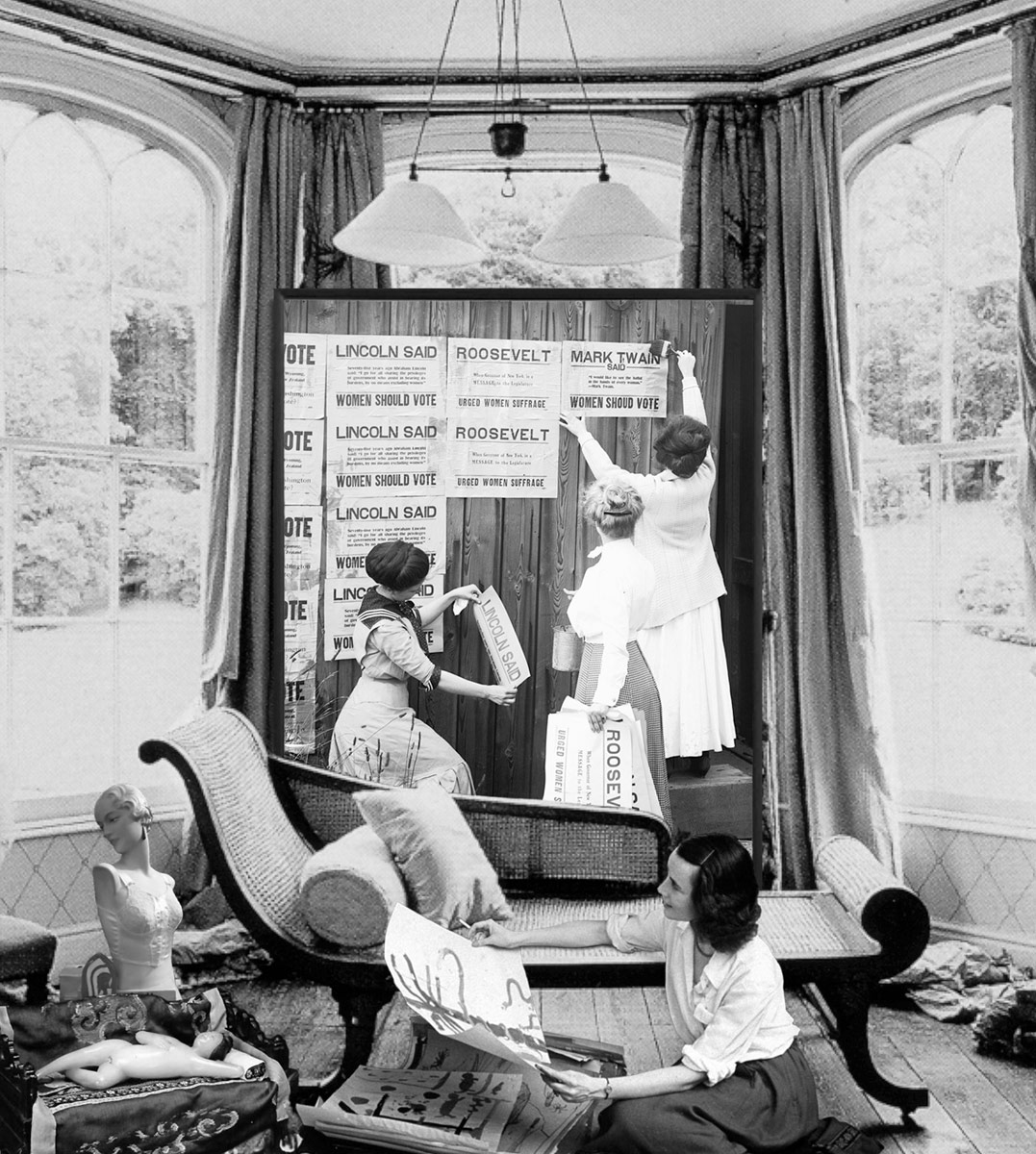

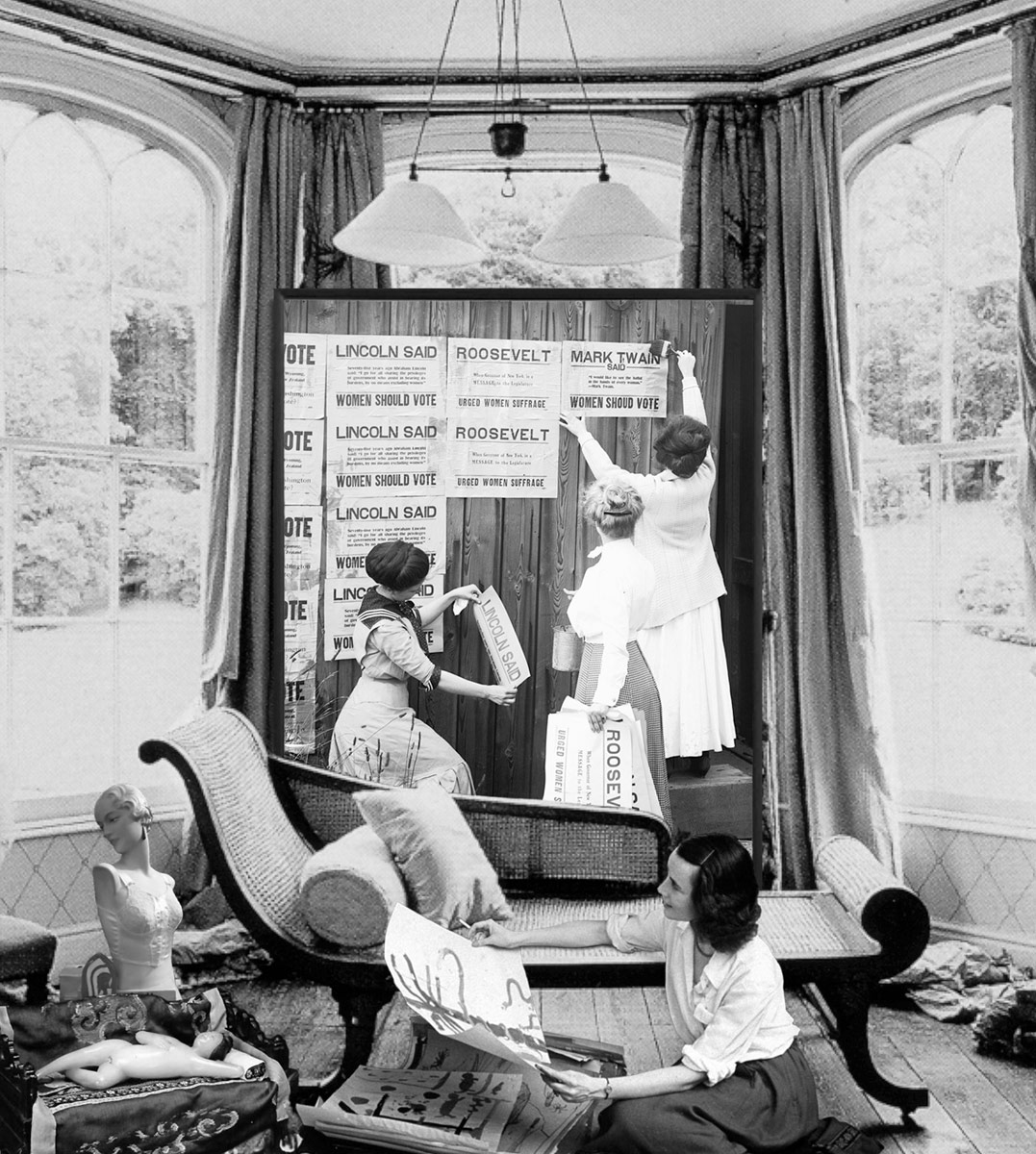

In Positives (2002-2003) famous historical press photos are re-staged, repeating the original in terms of composition, but changing the characters and the general meaning of the captured events, making a positive version of them. Libera comments: "The series is another attempt at playing with trauma. We are always dealing with memorized objects, not the objects themselves. I wanted to employ this mechanism of seeing and remembering and touch upon the phenomenon of memory's afterimages. This is how we actually perceive those photographs [the series "Positives"] - the harmless scenes trigger flashbacks of the brutal originals. I have picked the "negatives" from my own memory, from among the images I remembered from the childhood"

Zbigniew Libera (Poland, 1959) Is one of the most interesting and important Polish artists. His works - photographs, video films, installations, objects and drawings - piercingly and subversively play with the stereotypes of contemporary culture. His shocking video works from the 80s preceded body art by 10 years. In mid-90s, Libera began to create Correcting Devices - objects which are modifications of already existing products - objects of mass consumption. He also designs transformed toys - works that reveal the mechanisms of upbringing, education and cultural conditioning, the most famous of which is Lego Concentration Camp. From that moment on, he is one of the pillar of the so-called critical art. In recent years he has also been preoccupied with photography, especially the specificity of press photography and the ways in which the media shape our visual memory and manipulate the image of history.

Zbigniew Libera (Poland, 1959) Is one of the most interesting and important Polish artists. His works - photographs, video films, installations, objects and drawings - piercingly and subversively play with the stereotypes of contemporary culture. His shocking video works from the 80s preceded body art by 10 years. In mid-90s, Libera began to create Correcting Devices - objects which are modifications of already existing products - objects of mass consumption. He also designs transformed toys - works that reveal the mechanisms of upbringing, education and cultural conditioning, the most famous of which is Lego Concentration Camp. From that moment on, he is one of the pillar of the so-called critical art. In recent years he has also been preoccupied with photography, especially the specificity of press photography and the ways in which the media shape our visual memory and manipulate the image of history.

In Positives (2002-2003) famous historical press photos are re-staged, repeating the original in terms of composition, but changing the characters and the general meaning of the captured events, making a positive version of them. Libera comments: "The series is another attempt at playing with trauma. We are always dealing with memorized objects, not the objects themselves. I wanted to employ this mechanism of seeing and remembering and touch upon the phenomenon of memory's afterimages. This is how we actually perceive those photographs [the series "Positives"] - the harmless scenes trigger flashbacks of the brutal originals. I have picked the "negatives" from my own memory, from among the images I remembered from the childhood"

Zbigniew Libera (Poland, 1959) Is one of the most interesting and important Polish artists. His works - photographs, video films, installations, objects and drawings - piercingly and subversively play with the stereotypes of contemporary culture. His shocking video works from the 80s preceded body art by 10 years. In mid-90s, Libera began to create Correcting Devices - objects which are modifications of already existing products - objects of mass consumption. He also designs transformed toys - works that reveal the mechanisms of upbringing, education and cultural conditioning, the most famous of which is Lego Concentration Camp. From that moment on, he is one of the pillar of the so-called critical art. In recent years he has also been preoccupied with photography, especially the specificity of press photography and the ways in which the media shape our visual memory and manipulate the image of history.

Zbigniew Libera (Poland, 1959) Is one of the most interesting and important Polish artists. His works - photographs, video films, installations, objects and drawings - piercingly and subversively play with the stereotypes of contemporary culture. His shocking video works from the 80s preceded body art by 10 years. In mid-90s, Libera began to create Correcting Devices - objects which are modifications of already existing products - objects of mass consumption. He also designs transformed toys - works that reveal the mechanisms of upbringing, education and cultural conditioning, the most famous of which is Lego Concentration Camp. From that moment on, he is one of the pillar of the so-called critical art. In recent years he has also been preoccupied with photography, especially the specificity of press photography and the ways in which the media shape our visual memory and manipulate the image of history.Annemarie Bas

Zbigniew Libera (Pabianice, 1959) is a Polish artist who is not afraid of pushing boundaries, by creating provocative work that challenges the canonical narratives of our contemporary culture. He is known internationally for his work LEGO (1996), a limited edition of three LEGO sets of a concentration camp, that provoked a media controversy at the Venice Biennale of 1997. The curator of the Polish pavilion, Jan Stanisław Wojciechowski, refused to present it, saying the work treated one of the darkest moments in European civilization in a too frivolous manner.1

LEGO. Zbigniew Libera, 1996.

LEGO. Zbigniew Libera, 1996.

In 2002-2003 Libera made the series Positives, which he described as "another attempt at playing with trauma".2 For this series, he selected traumatic iconic photographs from recent history and made a positive version of them. The photo of a naked Vietnamese girl, running away from the village of Trang Bang after the napalm bombing in 1972, has been changed into a positive image of a nude and smiling woman; a group of concentration camp prisoners have been replaced by smiling figures in striped costumes.3

Positives. Zbigniew Libera, 2002-2003.

Positives. Zbigniew Libera, 2002-2003.

At first sight, we could state that this series is, like LEGO, a too frivolous approach of some of the traumatic episodes of our recent history. Some of the people who went through these horrors are still alive. Is it not disrespectful to confront them with a positive reinterpretation of their suffering? And to what end? What is Libera trying to say with this work? Is he just trying to be controversial or is there a more profound reasoning behind it?

In an interview with Katarzyna Bielas and Dorota Jarecka, from the Polish newspaper Gazeta Wyborcza, Libera said:

It seems to me that nowadays we don’t want to know what reality is like, we want to experience it positively. That’s why the prisoners became inhabitants, those were sad, these are glad. On the other hand it can be the mechanism of Nazi or Soviet propaganda, which changed reality into the set of optimistic slogans.4

On the one hand, it’s true that the market is providing us with a flood of glamorous and positive images. While there are plenty of serious issues asking for our attention —like climate change, armed conflicts, inequality— it is easy to get lost in the latest news about celebrities and fashion trends.5 On the other hand, the opposite is certainly as true, if not more so. Everyday we are flooded by shocking, sad, and negative images of people being decapitated by terrorists and refugees fleeing conflicted areas. Just think of the image of Aylan, the little Syrian boy who drowned in an attempt to reach the shores of Europe. This image was in the news for days and was widely disseminated by the social media. In this case, the so-called harsh reality was not ignored or concealed by optimistic slogans, but rather magnified and used as a moral appeal and tool for political action.

Kid Aylan Kurdi. 2015.

In an interview with Hedvig Turai from Art Margins, Libera gave another, more interesting explanation for Positives:

You have all those traumatic pictures that I am sure no one is able to consume and digest. You cannot live with them (…). I think that people instinctively do not want to look at these pictures, like that of the Vietnamese girl injured by napalm. We have various blocks. And the photo is blocked.6

By confronting us with a positive version of the traumatic photos, Libera hopes to unblock the original negative, so we can feel their impact again.7

One can wonder if everybody is experiencing this psychological block, but if we reflect a little bit more on the idea of iconic photographs being blocked, we could say that there’s also another kind of block which arises over the years, when a photo is used over and over again as an educational and political tool, and has become part of a fixed narrative. We have learned to look and interpret our past through these iconic photographs and it has become difficult to just see them by themselves without thinking of the narratives we’ve constructed around them. In the interview mentioned above, Libera says:

We never see anything for the first time, we always look at an object and we come back to the picture we saw of this object the previous time. We always make one step back into memory, back to the previous picture. We always view our own memories of things, and not the things themselves. It is like one very long permanent journey into our memory. I tried to nail down this process of seeing and remembering.8

What Libera says here about always viewing our memories of things and not the things themselves is certainly true. Personally, when I see the photos on which the positive Residents is based, I immediately recall the education I’ve had about the Holocaust, all the films and books I’ve seen and read about this theme, and the yearly commemorations of the horrors of World War II; and I cannot see these images without thinking about the lesson I was taught: "We cannot let this happen ever again". Although there is nothing wrong with that lesson, it makes you think of the power iconic images have; some more reflection on that wouldn’t be bad.

Residents. Zbigniew Libera.

Coming back to the question if there is more to the work Positives than just controversy, I think we can reasonably answer that in the affirmative, although his method might not be the most sensitive one. The Czech photographer Pavel Maria Smejlik, who is playing a similar game of seeing and remembering with his series Fatescapes (2009-2010), has a more subtle approach: he also selected iconic (war) images but instead of making their positive counterpart, he took out the central motifs and people.9 If we assume that this kind of traumatic images are blocked, this would be another way of unblocking them but then without the initial shock of seeing their positive reinterpretation.

Fatescapes. Pavel Maria Smejkal, 2009-2010.

Whatever one’s personal preference, Libera’s work doesn’t leave one indifferent. Positives challenges us to ask ourselves if we really have observed the iconic photos that surround us and if we’ve reflected upon the narratives connected to them. The dialogue that this series might inspire about the fixed narratives related to these iconic images, is a valuable one that we should have more often.

1. http://articles.latimes.com/1997-05-19/news/mn-60350_1_lego-toys

2. http://raster.art.pl/gallery/artists/libera/prace.htm

3. http://www.artmargins.com/index.php/archive/166-the-artist-does-not-own-his-interpretations-hedvig-turai-in-conversation-with-zbigniew-libera

4. http://maurycy.atlas.com.pl/ang.nsf/0/46CD099B0570C5CBC1256E37004D54D4?OpenDocument

5. Un comentario interesante sobre este fenómeno es “Simple Living “ de Nadia Plesner: http://www.nadiaplesner.com/simple-living--darfurnica1

6. http://www.artmargins.com/index.php/archive/166-the-artist-does-not-own-his-interpretations-hedvig-turai-in-conversation-with-zbigniew-libera

7. http://deruimtemaker.nl/2013/02/27/spelen-met-iconen-uit-de-fotografie/

8. http://www.artmargins.com/index.php/archive/166-the-artist-does-not-own-his-interpretations-hedvig-turai-in-conversation-with-zbigniew-libera

9. http://www.pavelmaria.com/fatescapestext2.html

Annemarie Bas (The Netherlands, 1986), has a Bachelor’s degree in History at the University of Utrecht and a Master’s degree in Cultural History at the same institution. As a historian, she worked as a junior researcher at the Museum of Psychiatry "Het Dolhuys" in Haarlem, The Netherlands. Since 2013, she lives and works in Mexico City. At the moment, she is international liaison at ZoneZero and works as an independent translator.

Annemarie Bas (The Netherlands, 1986), has a Bachelor’s degree in History at the University of Utrecht and a Master’s degree in Cultural History at the same institution. As a historian, she worked as a junior researcher at the Museum of Psychiatry "Het Dolhuys" in Haarlem, The Netherlands. Since 2013, she lives and works in Mexico City. At the moment, she is international liaison at ZoneZero and works as an independent translator.Zbigniew Libera (Pabianice, 1959) is a Polish artist who is not afraid of pushing boundaries, by creating provocative work that challenges the canonical narratives of our contemporary culture. He is known internationally for his work LEGO (1996), a limited edition of three LEGO sets of a concentration camp, that provoked a media controversy at the Venice Biennale of 1997. The curator of the Polish pavilion, Jan Stanisław Wojciechowski, refused to present it, saying the work treated one of the darkest moments in European civilization in a too frivolous manner.1

LEGO. Zbigniew Libera, 1996.

LEGO. Zbigniew Libera, 1996.

In 2002-2003 Libera made the series Positives, which he described as "another attempt at playing with trauma".2 For this series, he selected traumatic iconic photographs from recent history and made a positive version of them. The photo of a naked Vietnamese girl, running away from the village of Trang Bang after the napalm bombing in 1972, has been changed into a positive image of a nude and smiling woman; a group of concentration camp prisoners have been replaced by smiling figures in striped costumes.3

Positives. Zbigniew Libera, 2002-2003.

Positives. Zbigniew Libera, 2002-2003.

At first sight, we could state that this series is, like LEGO, a too frivolous approach of some of the traumatic episodes of our recent history. Some of the people who went through these horrors are still alive. Is it not disrespectful to confront them with a positive reinterpretation of their suffering? And to what end? What is Libera trying to say with this work? Is he just trying to be controversial or is there a more profound reasoning behind it?

In an interview with Katarzyna Bielas and Dorota Jarecka, from the Polish newspaper Gazeta Wyborcza, Libera said:

It seems to me that nowadays we don’t want to know what reality is like, we want to experience it positively. That’s why the prisoners became inhabitants, those were sad, these are glad. On the other hand it can be the mechanism of Nazi or Soviet propaganda, which changed reality into the set of optimistic slogans.4

On the one hand, it’s true that the market is providing us with a flood of glamorous and positive images. While there are plenty of serious issues asking for our attention —like climate change, armed conflicts, inequality— it is easy to get lost in the latest news about celebrities and fashion trends.5 On the other hand, the opposite is certainly as true, if not more so. Everyday we are flooded by shocking, sad, and negative images of people being decapitated by terrorists and refugees fleeing conflicted areas. Just think of the image of Aylan, the little Syrian boy who drowned in an attempt to reach the shores of Europe. This image was in the news for days and was widely disseminated by the social media. In this case, the so-called harsh reality was not ignored or concealed by optimistic slogans, but rather magnified and used as a moral appeal and tool for political action.

Kid Aylan Kurdi. 2015.

In an interview with Hedvig Turai from Art Margins, Libera gave another, more interesting explanation for Positives:

You have all those traumatic pictures that I am sure no one is able to consume and digest. You cannot live with them (…). I think that people instinctively do not want to look at these pictures, like that of the Vietnamese girl injured by napalm. We have various blocks. And the photo is blocked.6

By confronting us with a positive version of the traumatic photos, Libera hopes to unblock the original negative, so we can feel their impact again.7

One can wonder if everybody is experiencing this psychological block, but if we reflect a little bit more on the idea of iconic photographs being blocked, we could say that there’s also another kind of block which arises over the years, when a photo is used over and over again as an educational and political tool, and has become part of a fixed narrative. We have learned to look and interpret our past through these iconic photographs and it has become difficult to just see them by themselves without thinking of the narratives we’ve constructed around them. In the interview mentioned above, Libera says:

We never see anything for the first time, we always look at an object and we come back to the picture we saw of this object the previous time. We always make one step back into memory, back to the previous picture. We always view our own memories of things, and not the things themselves. It is like one very long permanent journey into our memory. I tried to nail down this process of seeing and remembering.8

What Libera says here about always viewing our memories of things and not the things themselves is certainly true. Personally, when I see the photos on which the positive Residents is based, I immediately recall the education I’ve had about the Holocaust, all the films and books I’ve seen and read about this theme, and the yearly commemorations of the horrors of World War II; and I cannot see these images without thinking about the lesson I was taught: "We cannot let this happen ever again". Although there is nothing wrong with that lesson, it makes you think of the power iconic images have; some more reflection on that wouldn’t be bad.

Residents. Zbigniew Libera.

Coming back to the question if there is more to the work Positives than just controversy, I think we can reasonably answer that in the affirmative, although his method might not be the most sensitive one. The Czech photographer Pavel Maria Smejlik, who is playing a similar game of seeing and remembering with his series Fatescapes (2009-2010), has a more subtle approach: he also selected iconic (war) images but instead of making their positive counterpart, he took out the central motifs and people.9 If we assume that this kind of traumatic images are blocked, this would be another way of unblocking them but then without the initial shock of seeing their positive reinterpretation.

Fatescapes. Pavel Maria Smejkal, 2009-2010.

Whatever one’s personal preference, Libera’s work doesn’t leave one indifferent. Positives challenges us to ask ourselves if we really have observed the iconic photos that surround us and if we’ve reflected upon the narratives connected to them. The dialogue that this series might inspire about the fixed narratives related to these iconic images, is a valuable one that we should have more often.

1. http://articles.latimes.com/1997-05-19/news/mn-60350_1_lego-toys

2. http://raster.art.pl/gallery/artists/libera/prace.htm

3. http://www.artmargins.com/index.php/archive/166-the-artist-does-not-own-his-interpretations-hedvig-turai-in-conversation-with-zbigniew-libera

4. http://maurycy.atlas.com.pl/ang.nsf/0/46CD099B0570C5CBC1256E37004D54D4?OpenDocument

5. Un comentario interesante sobre este fenómeno es “Simple Living “ de Nadia Plesner: http://www.nadiaplesner.com/simple-living--darfurnica1

6. http://www.artmargins.com/index.php/archive/166-the-artist-does-not-own-his-interpretations-hedvig-turai-in-conversation-with-zbigniew-libera

7. http://deruimtemaker.nl/2013/02/27/spelen-met-iconen-uit-de-fotografie/

8. http://www.artmargins.com/index.php/archive/166-the-artist-does-not-own-his-interpretations-hedvig-turai-in-conversation-with-zbigniew-libera

9. http://www.pavelmaria.com/fatescapestext2.html

Annemarie Bas (The Netherlands, 1986), has a Bachelor’s degree in History at the University of Utrecht and a Master’s degree in Cultural History at the same institution. As a historian, she worked as a junior researcher at the Museum of Psychiatry "Het Dolhuys" in Haarlem, The Netherlands. Since 2013, she lives and works in Mexico City. At the moment, she is international liaison at ZoneZero and works as an independent translator.

Annemarie Bas (The Netherlands, 1986), has a Bachelor’s degree in History at the University of Utrecht and a Master’s degree in Cultural History at the same institution. As a historian, she worked as a junior researcher at the Museum of Psychiatry "Het Dolhuys" in Haarlem, The Netherlands. Since 2013, she lives and works in Mexico City. At the moment, she is international liaison at ZoneZero and works as an independent translator.Elisa Calore

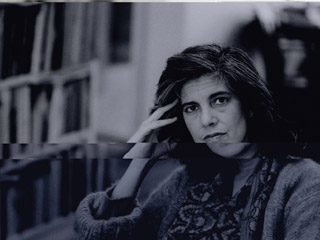

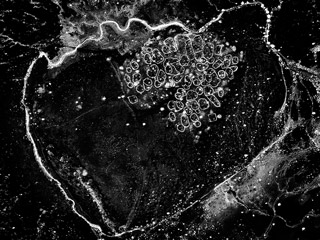

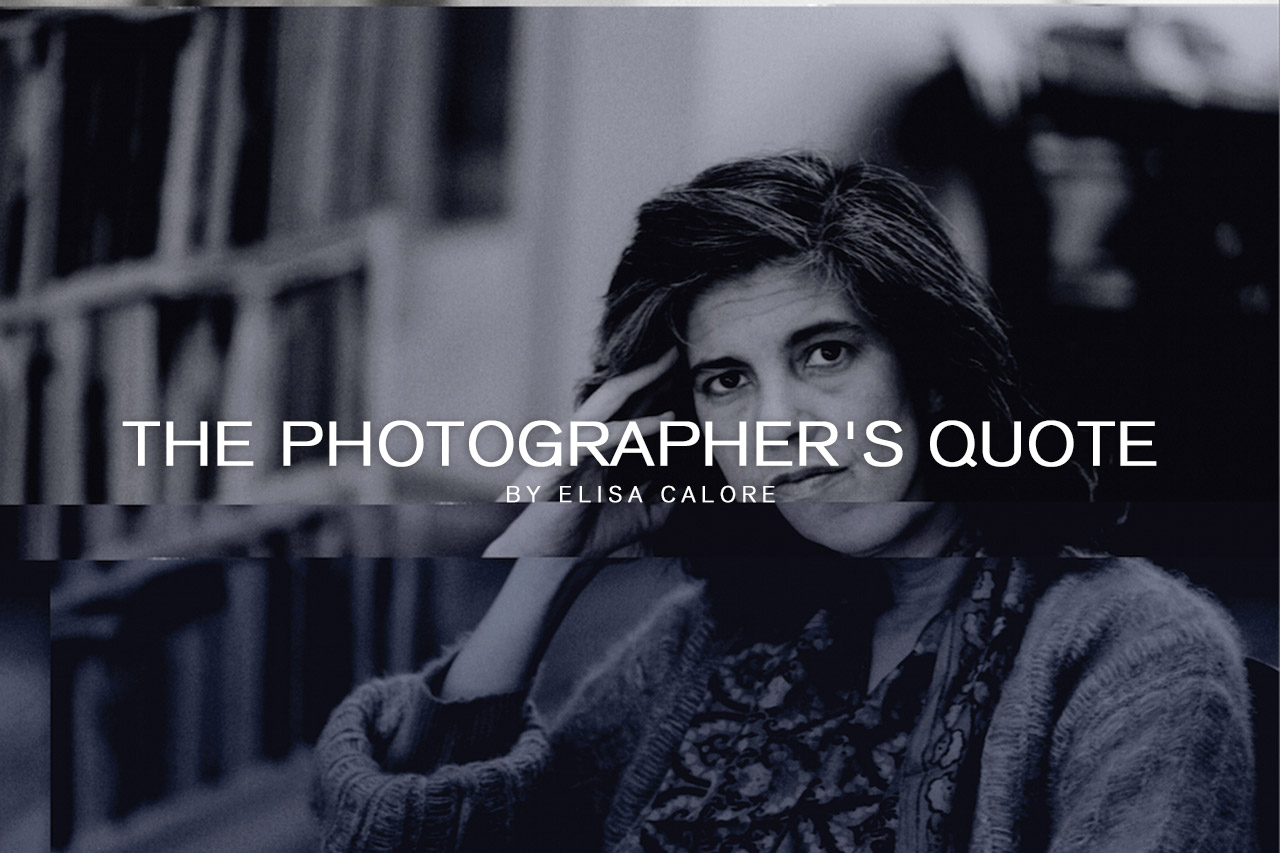

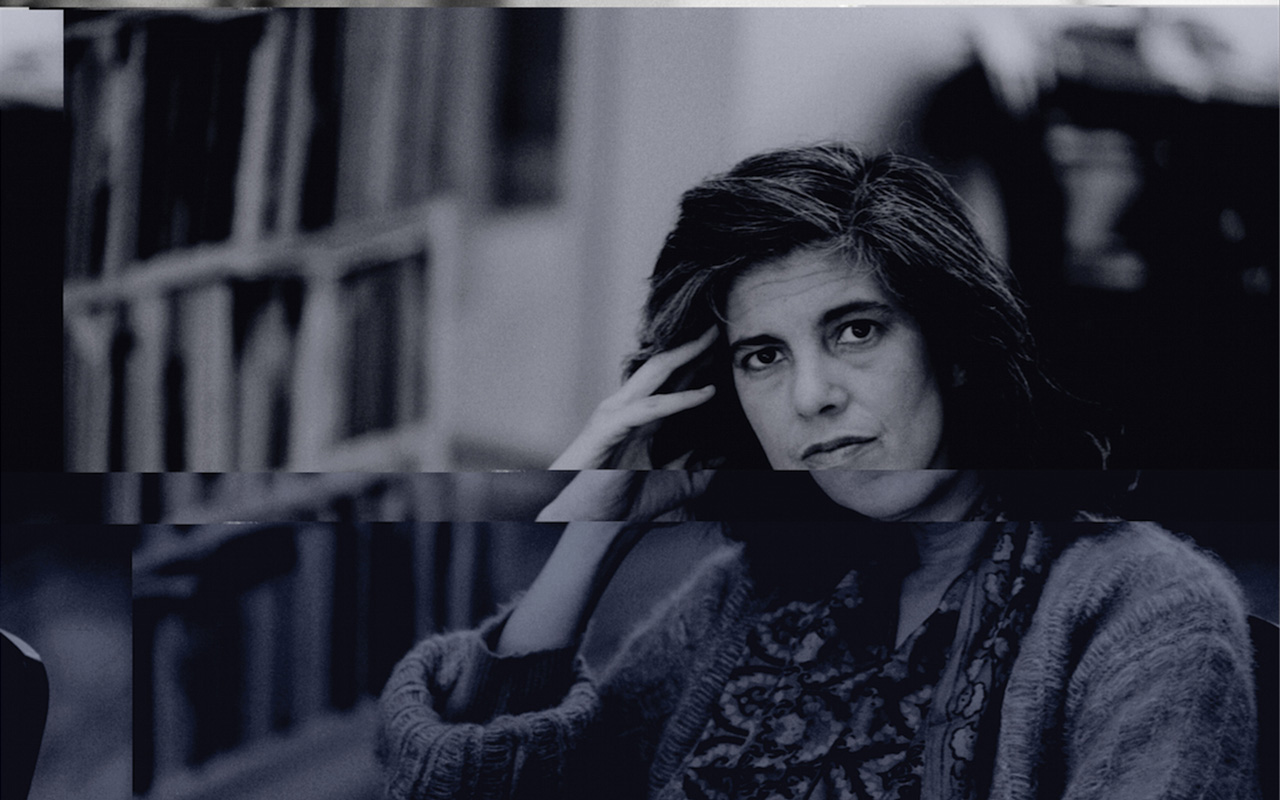

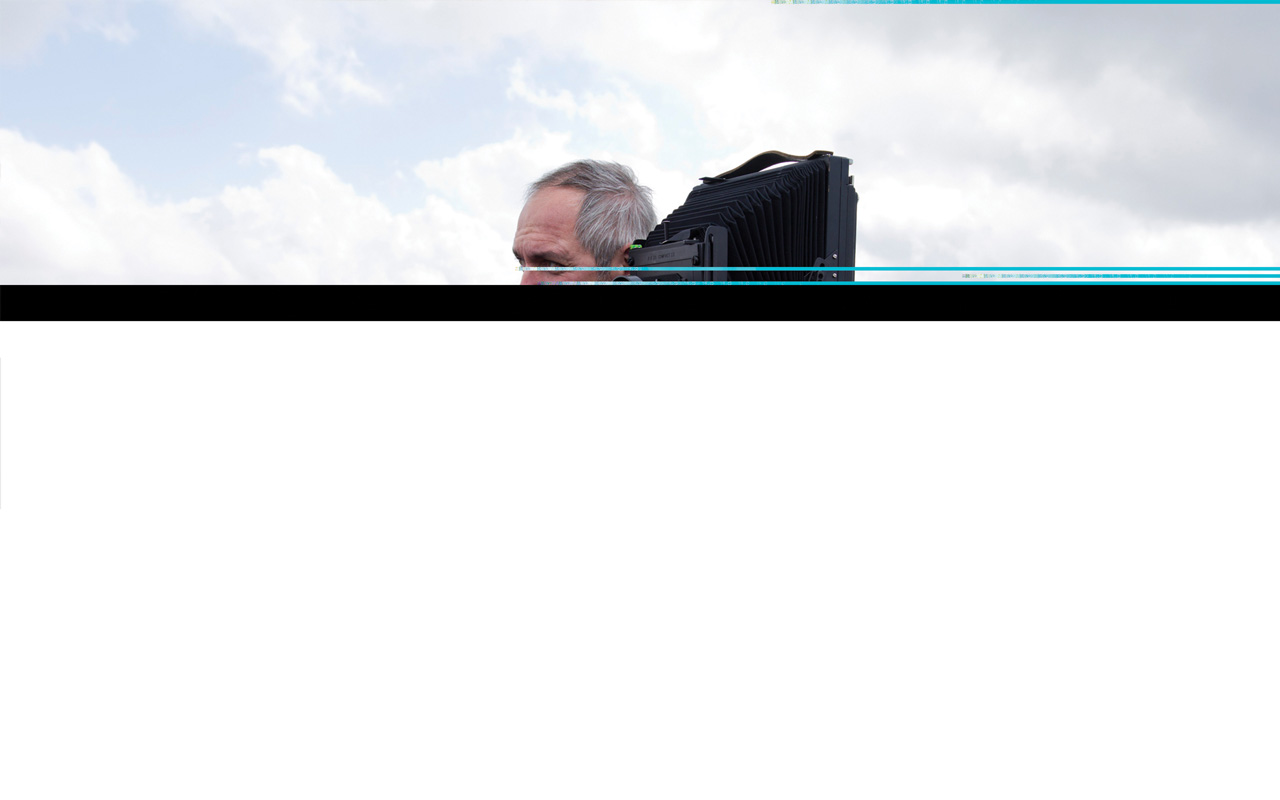

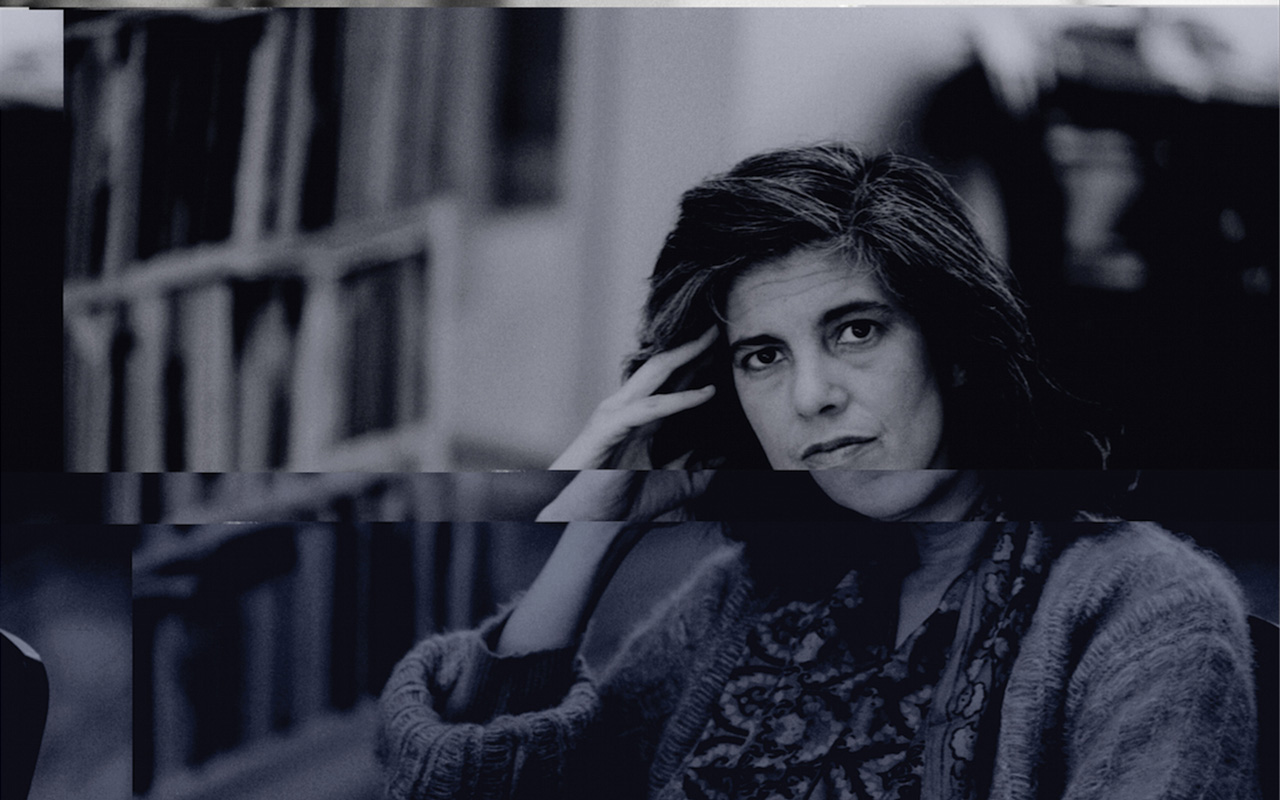

Does a portrait tell something about the person photographed? Does text help us to read a photograph more clearly?

"To quote out of context is the essence of the photographer's craft” said John Szarkowski in his The Photographer's Eye.

I downloaded portraits of famous photographers and opened them with the program TextEdit. Then I added some of the thoughts of these photographers to the code of their portraits, causing a “literary glitch” that helps us look cautiously at the medium and its relationship with words. The process of elaborating the photos is not coincidental, but a procedure carried out in accordance with the knowledge of the medium, despite the random results.

William Eggleston:

A picture is what it is and I’ve never noticed that it helps to talk about them, or answer specific questions about them, much less volunteer information in words. It wouldn’t make any sense to explain them. Kind of diminishes them. People always want to know when something was taken, where it was taken, and, God knows, why it was taken. It gets really ridiculous. I mean, they’re right there, whatever they are.

Walker Evans:

The photographs are not illustrative. They, and the text, are coequal, mutually independent, and fully collaborative.

Annie Leibovitz:

In a portrait, you have room to have a point of view. The image may not be literally what's going on, but it's representative.

Susan Sontag:

To take a photograph is to participate in another person's mortality, vulnerability, mutability. Precisely by slicing out this moment and freezing it, all photographs testify to time's relentless melt.

Thomas Struth:

For me, making a photograph is mostly an intellectual process of understanding people or cities and their historical and phenomenological connections. At that point the photo is almost made, and all that remains is the mechanical process.

Elisa Calore (Italy, 1982). Designer and researcher in the field of visual and multimedia communication. Her practice has mainly been focused around different aspects of the image: its construction and its use to give it meaning, the social context, the place in which it is positioned, its qualities, its economic value, the cultural negotiation between creators and viewers. Passionate about all matter related to photography, she is the general coordinator of the first edition of PRISMA – Human Rights Photo Contest.

Elisa Calore (Italy, 1982). Designer and researcher in the field of visual and multimedia communication. Her practice has mainly been focused around different aspects of the image: its construction and its use to give it meaning, the social context, the place in which it is positioned, its qualities, its economic value, the cultural negotiation between creators and viewers. Passionate about all matter related to photography, she is the general coordinator of the first edition of PRISMA – Human Rights Photo Contest.

Does a portrait tell something about the person photographed? Does text help us to read a photograph more clearly?

"To quote out of context is the essence of the photographer's craft” said John Szarkowski in his The Photographer's Eye.

I downloaded portraits of famous photographers and opened them with the program TextEdit. Then I added some of the thoughts of these photographers to the code of their portraits, causing a “literary glitch” that helps us look cautiously at the medium and its relationship with words. The process of elaborating the photos is not coincidental, but a procedure carried out in accordance with the knowledge of the medium, despite the random results.

William Eggleston:

A picture is what it is and I’ve never noticed that it helps to talk about them, or answer specific questions about them, much less volunteer information in words. It wouldn’t make any sense to explain them. Kind of diminishes them. People always want to know when something was taken, where it was taken, and, God knows, why it was taken. It gets really ridiculous. I mean, they’re right there, whatever they are.

Walker Evans:

The photographs are not illustrative. They, and the text, are coequal, mutually independent, and fully collaborative.

Annie Leibovitz:

In a portrait, you have room to have a point of view. The image may not be literally what's going on, but it's representative.

Susan Sontag:

To take a photograph is to participate in another person's mortality, vulnerability, mutability. Precisely by slicing out this moment and freezing it, all photographs testify to time's relentless melt.

Thomas Struth:

For me, making a photograph is mostly an intellectual process of understanding people or cities and their historical and phenomenological connections. At that point the photo is almost made, and all that remains is the mechanical process.

Elisa Calore (Italy, 1982). Designer and researcher in the field of visual and multimedia communication. Her practice has mainly been focused around different aspects of the image: its construction and its use to give it meaning, the social context, the place in which it is positioned, its qualities, its economic value, the cultural negotiation between creators and viewers. Passionate about all matter related to photography, she is the general coordinator of the first edition of PRISMA – Human Rights Photo Contest.

Elisa Calore (Italy, 1982). Designer and researcher in the field of visual and multimedia communication. Her practice has mainly been focused around different aspects of the image: its construction and its use to give it meaning, the social context, the place in which it is positioned, its qualities, its economic value, the cultural negotiation between creators and viewers. Passionate about all matter related to photography, she is the general coordinator of the first edition of PRISMA – Human Rights Photo Contest.Regula Bochsler

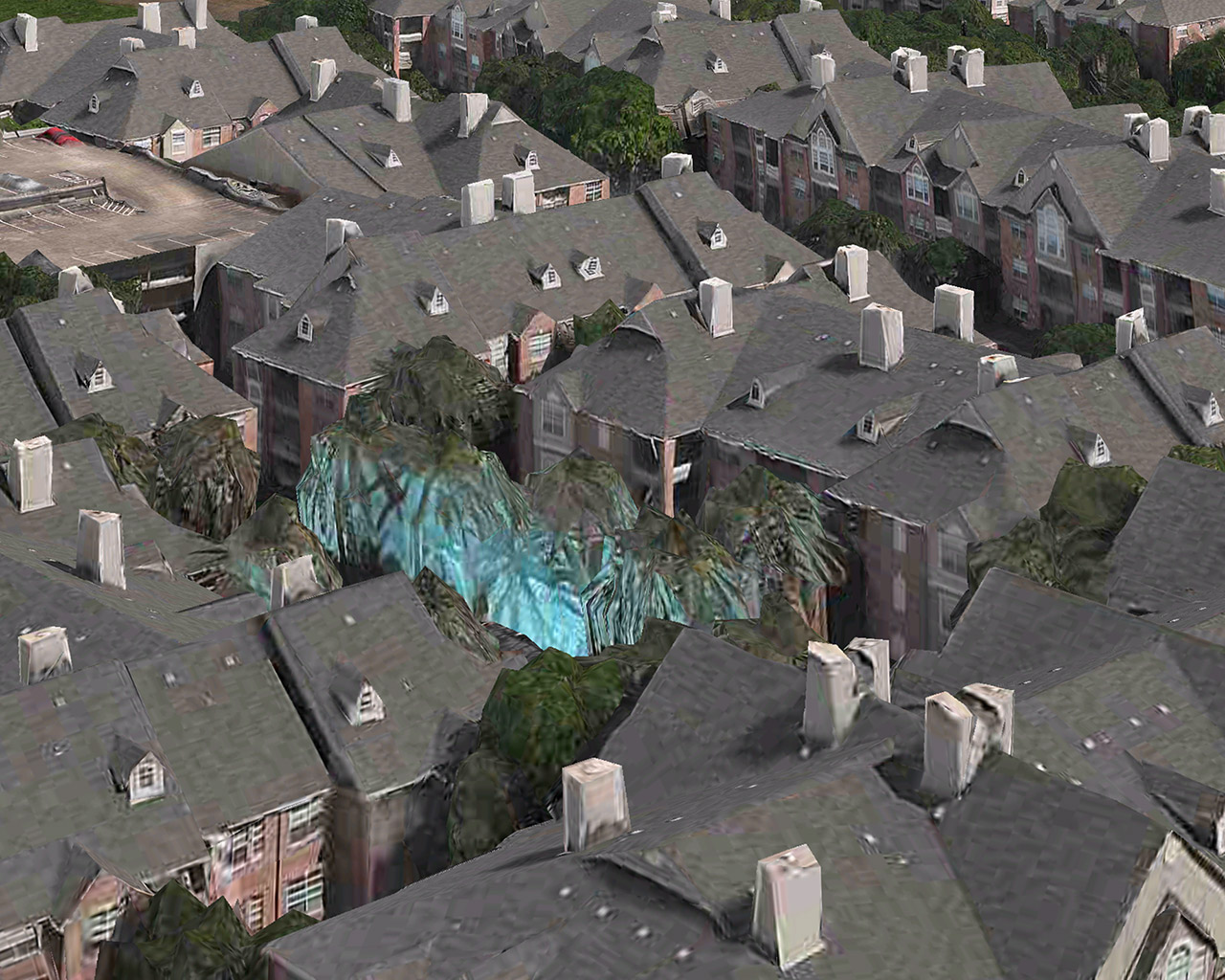

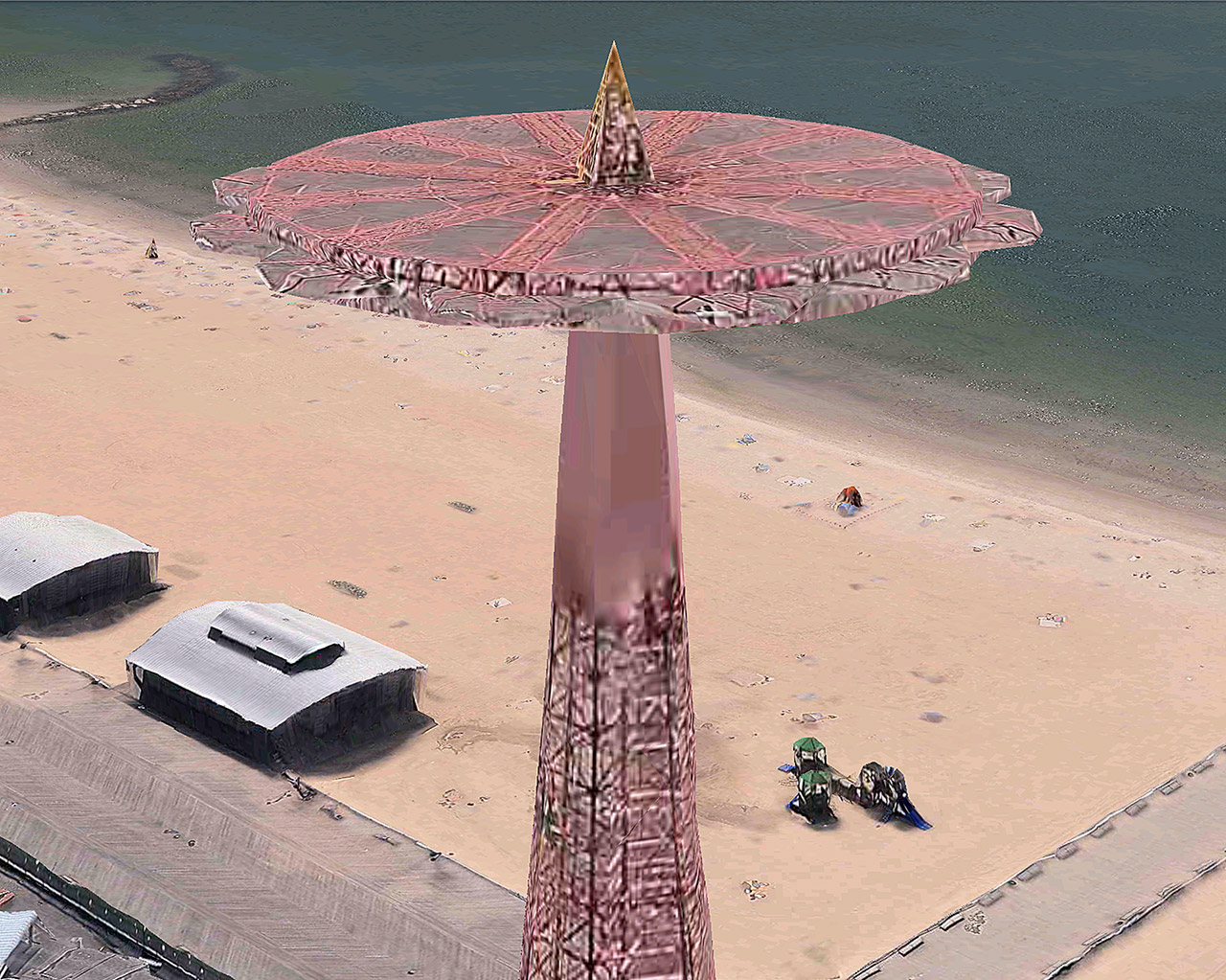

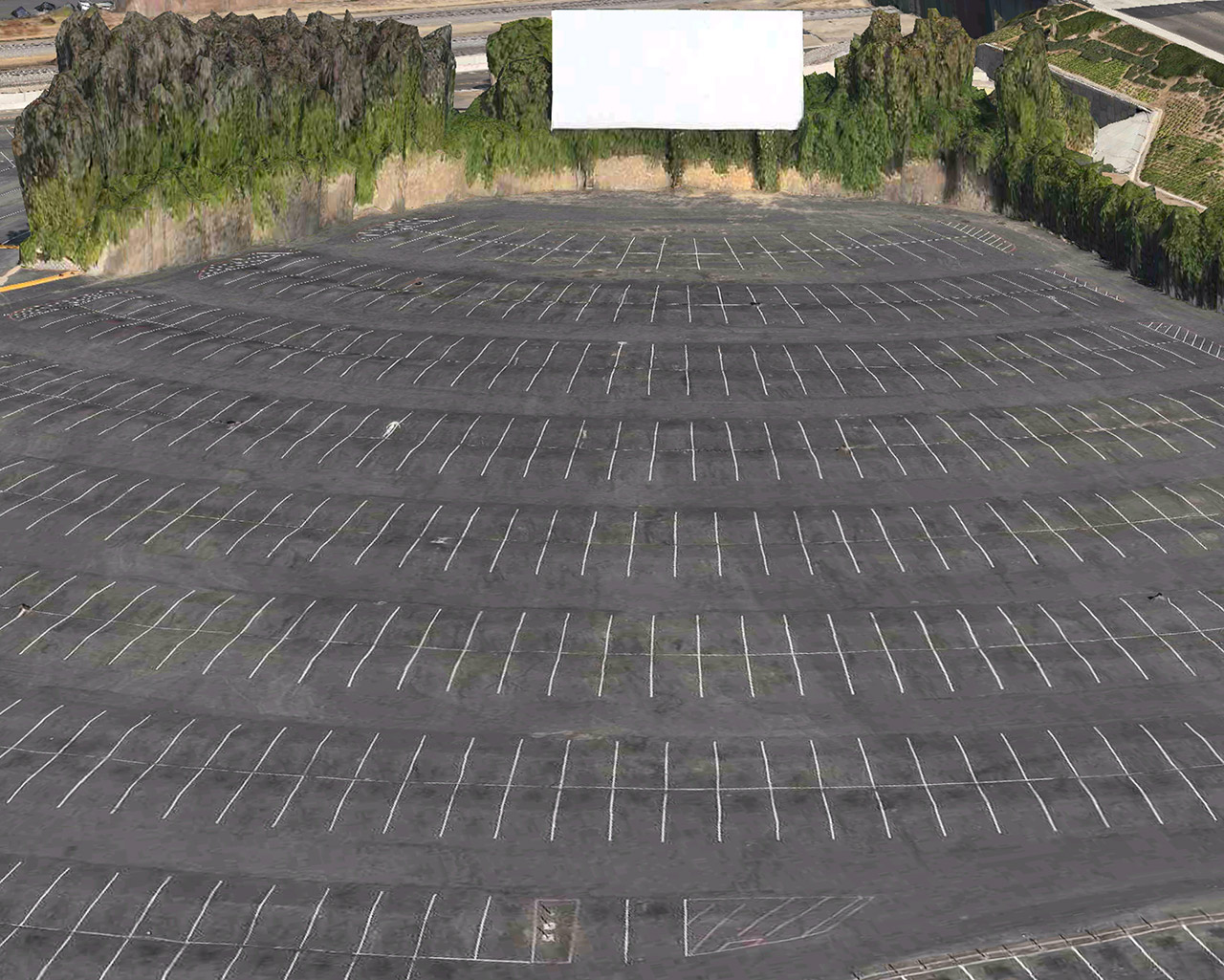

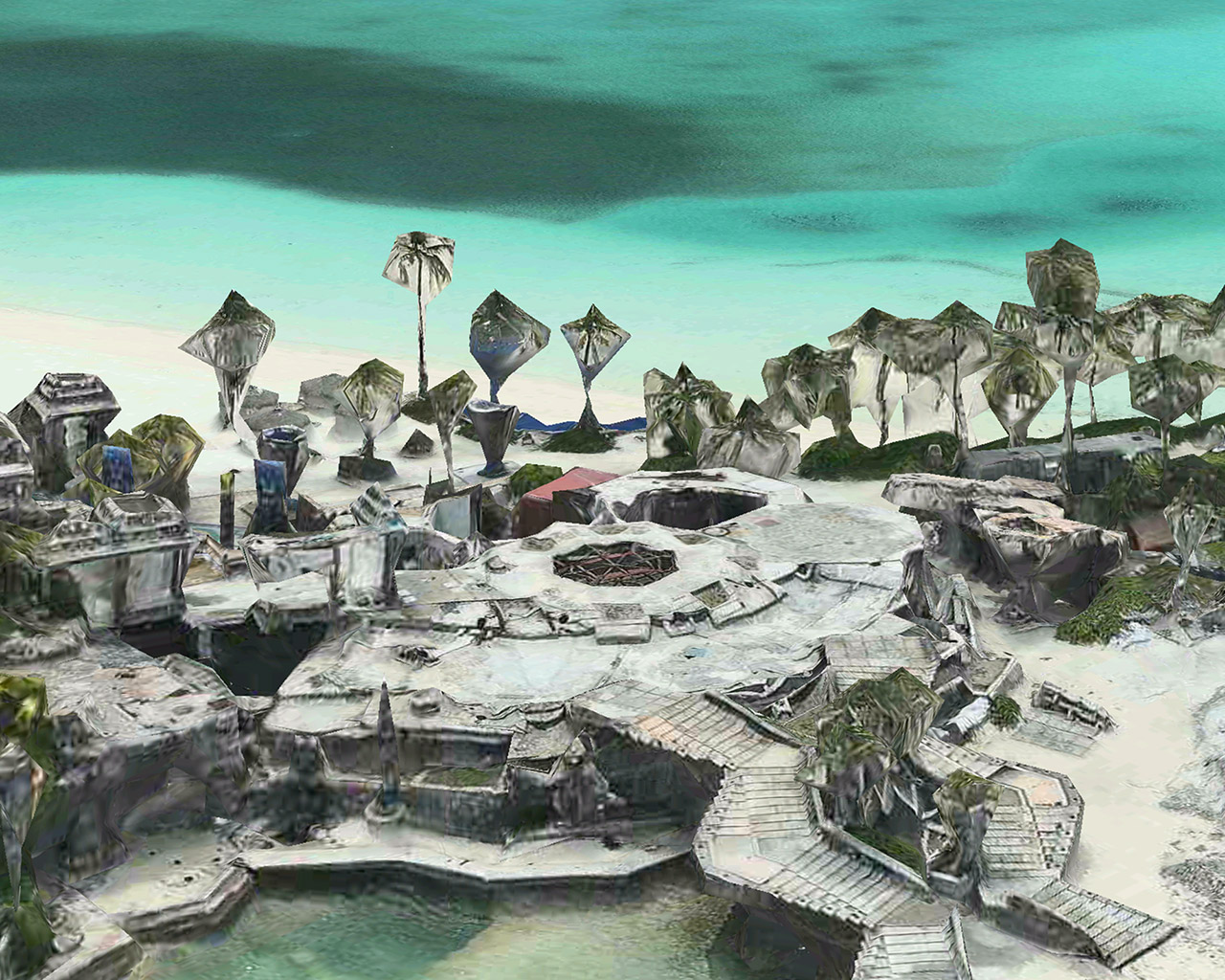

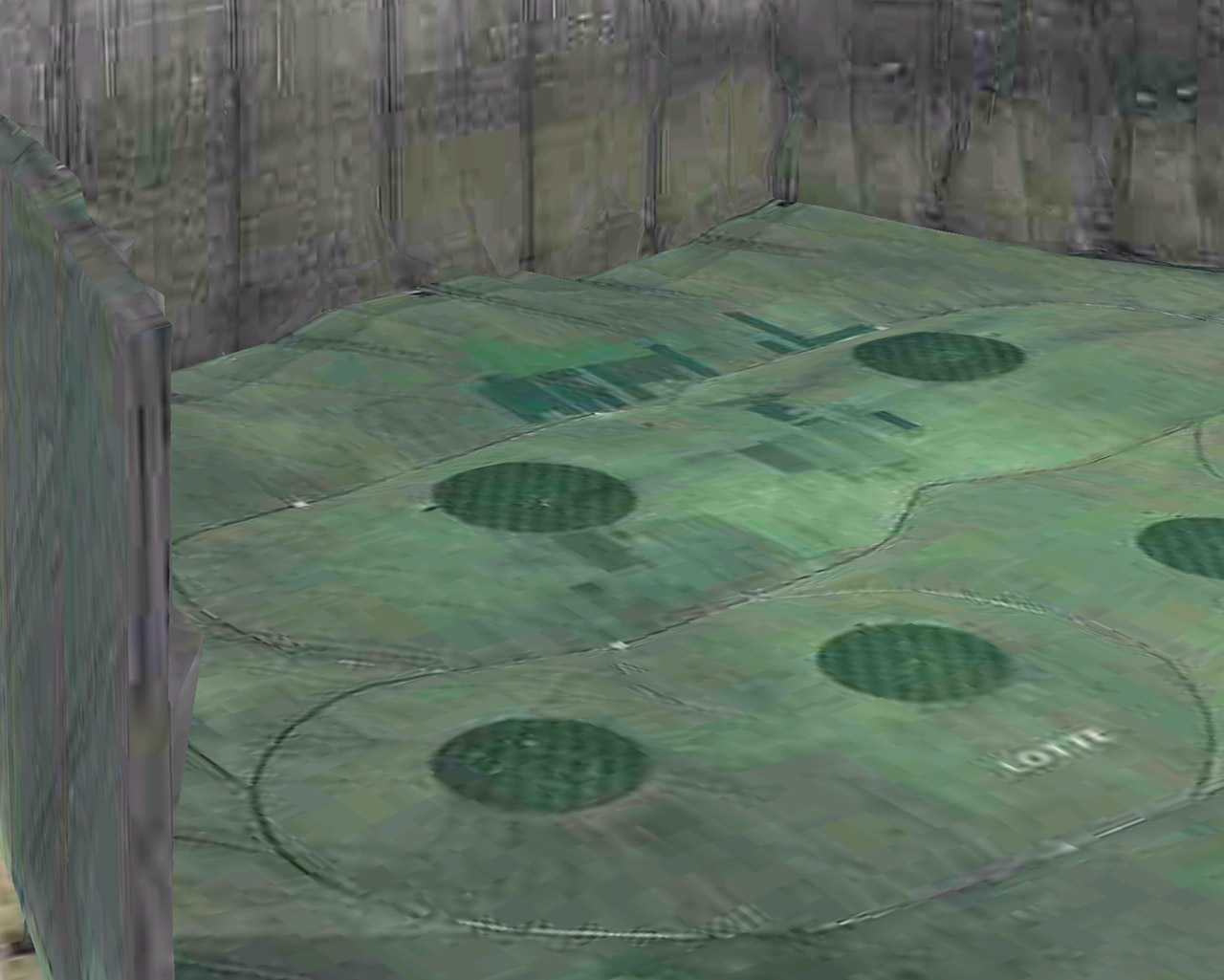

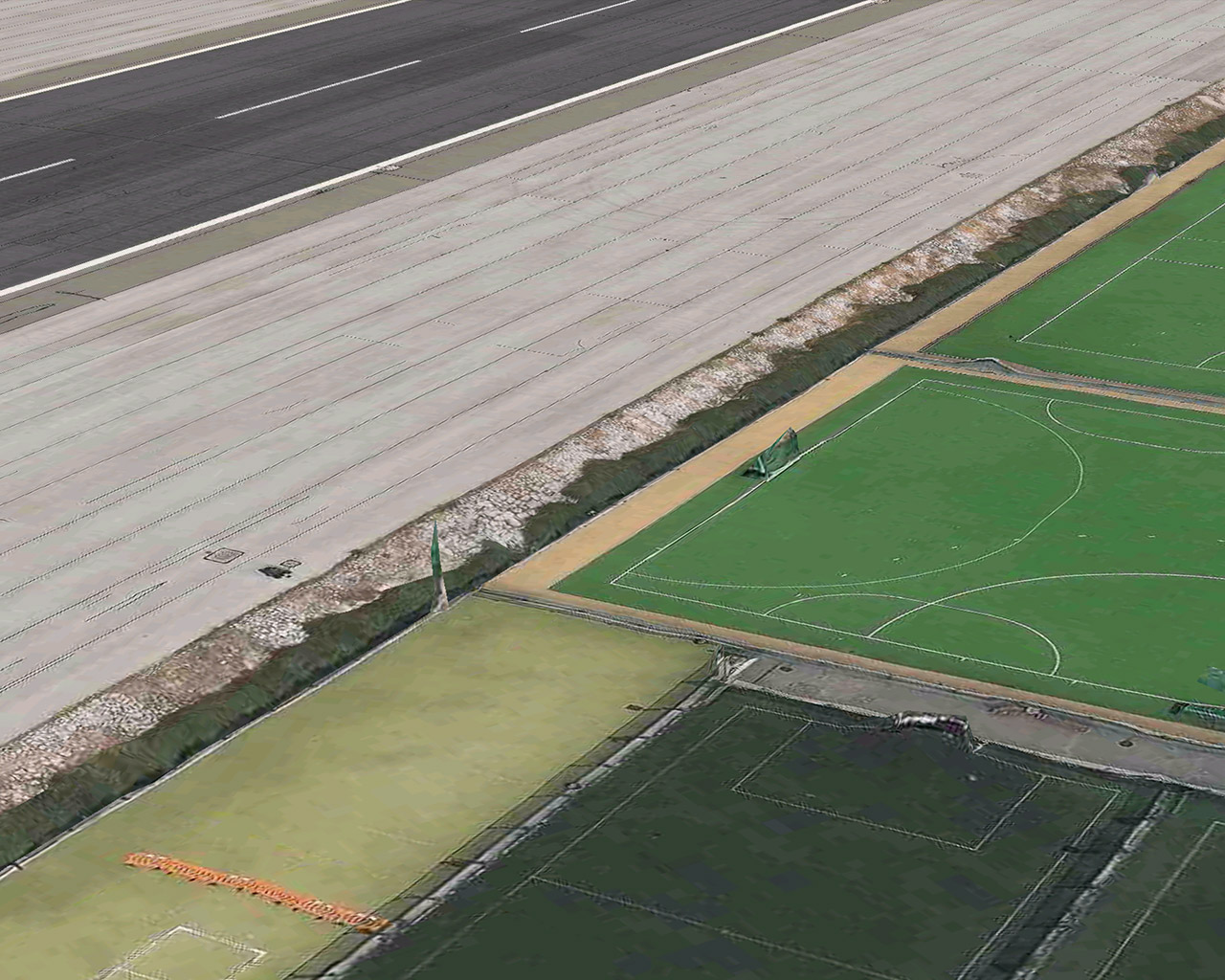

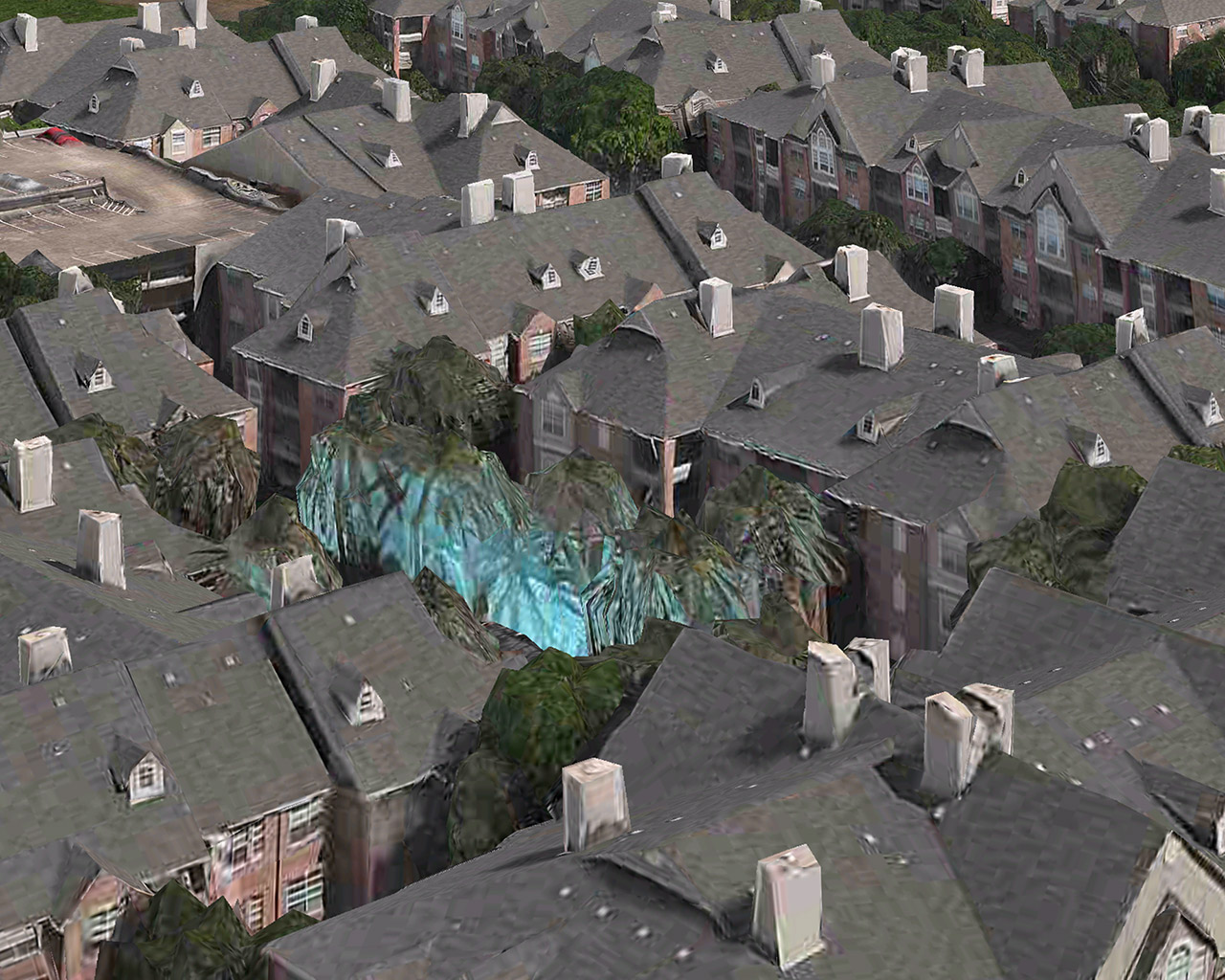

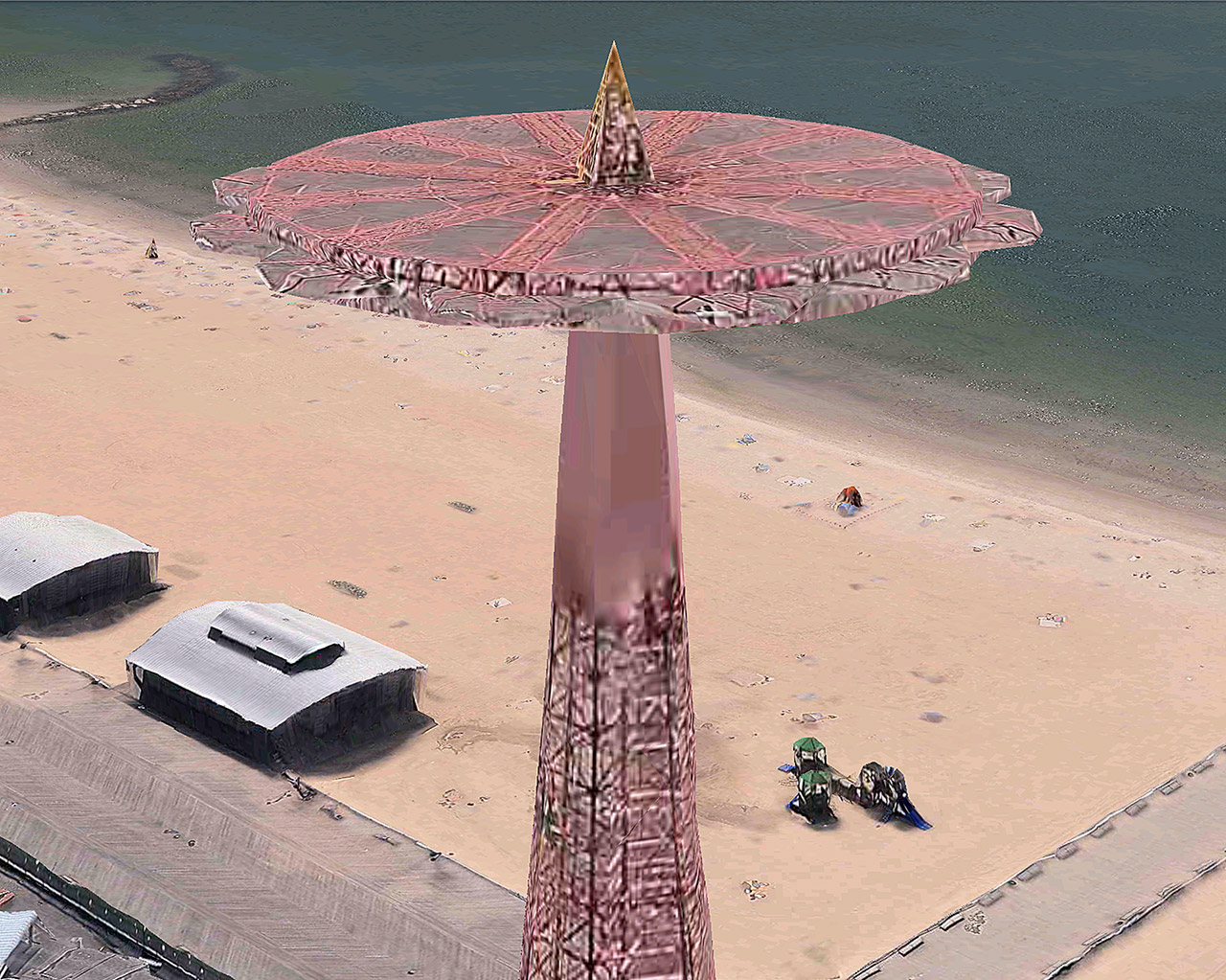

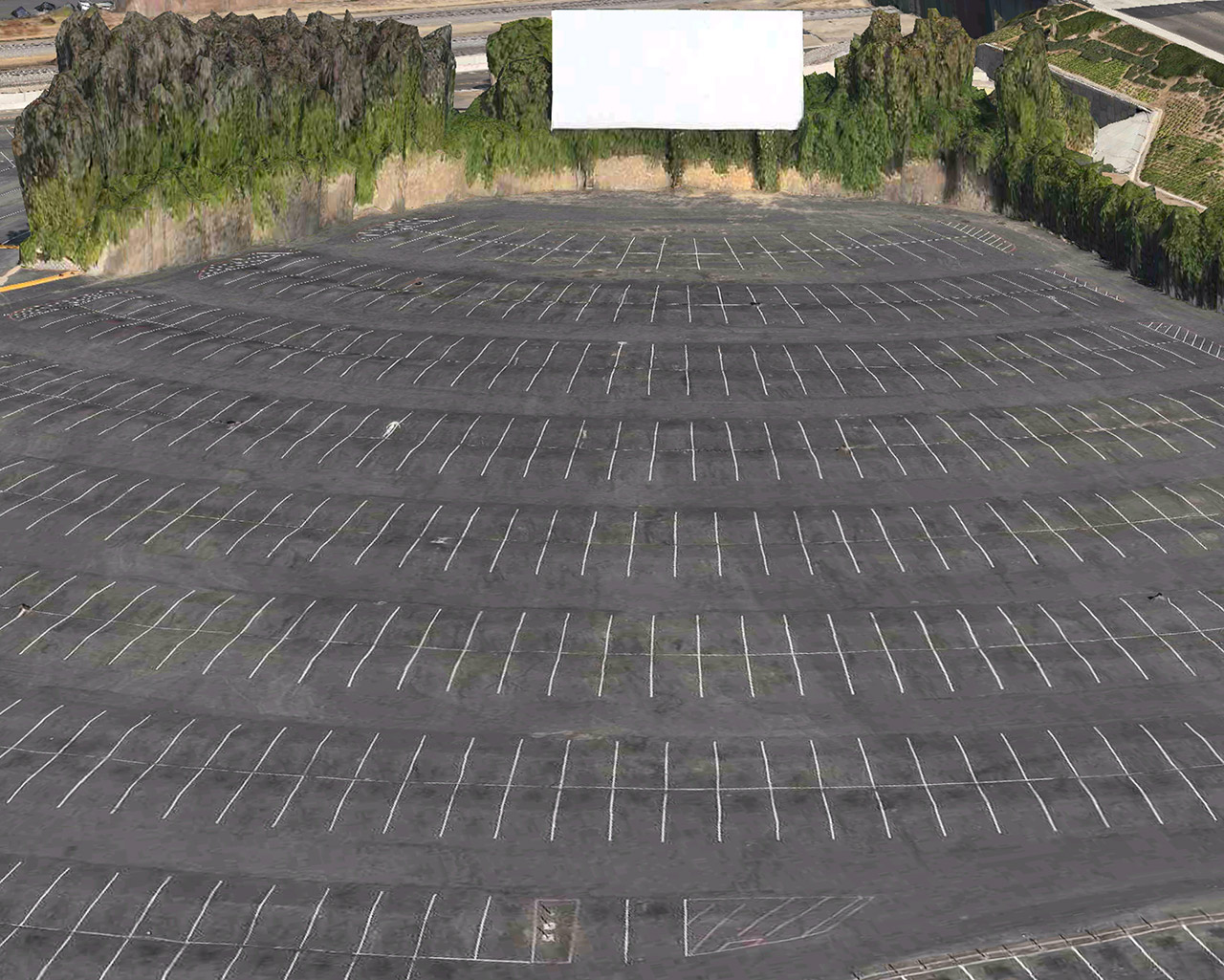

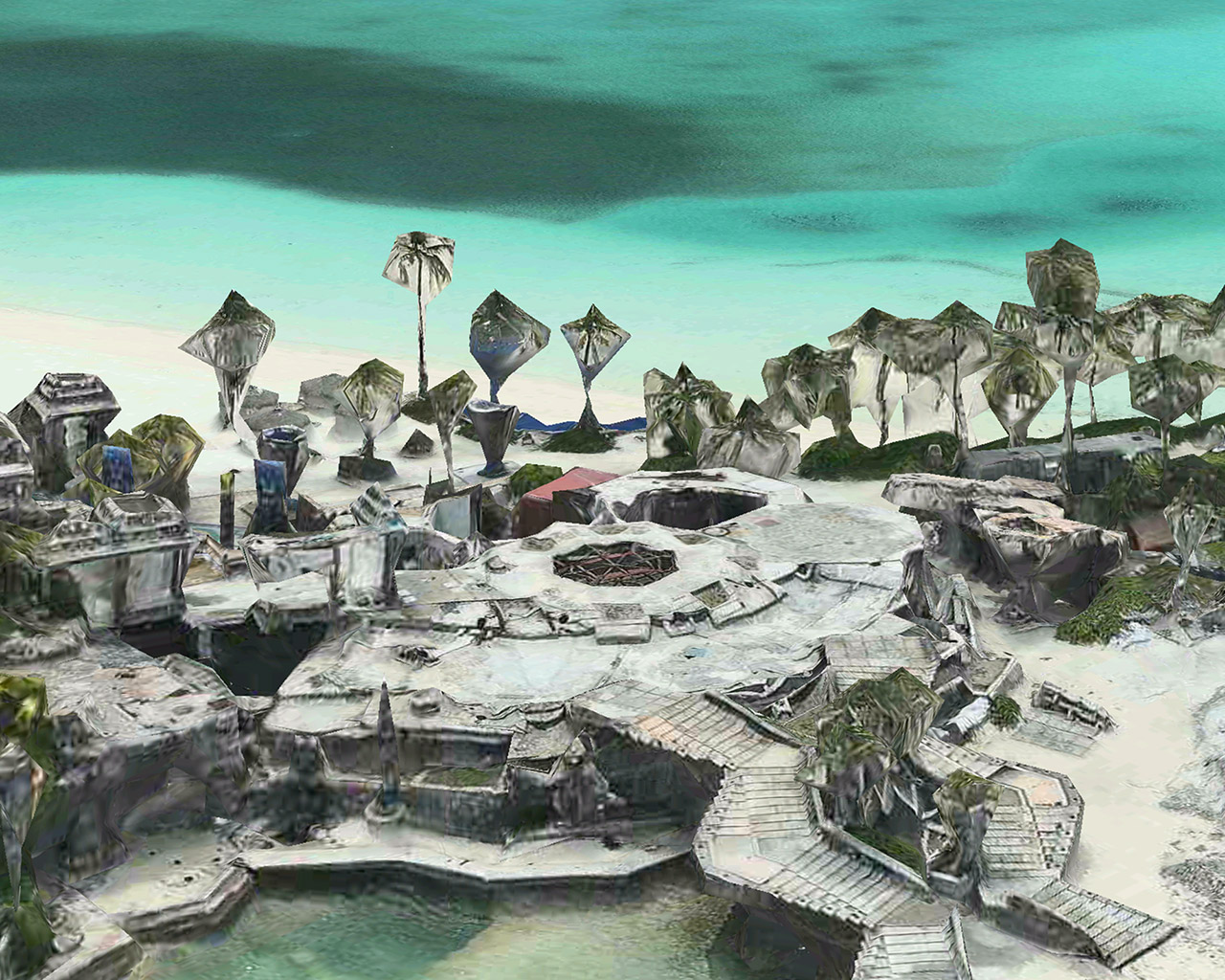

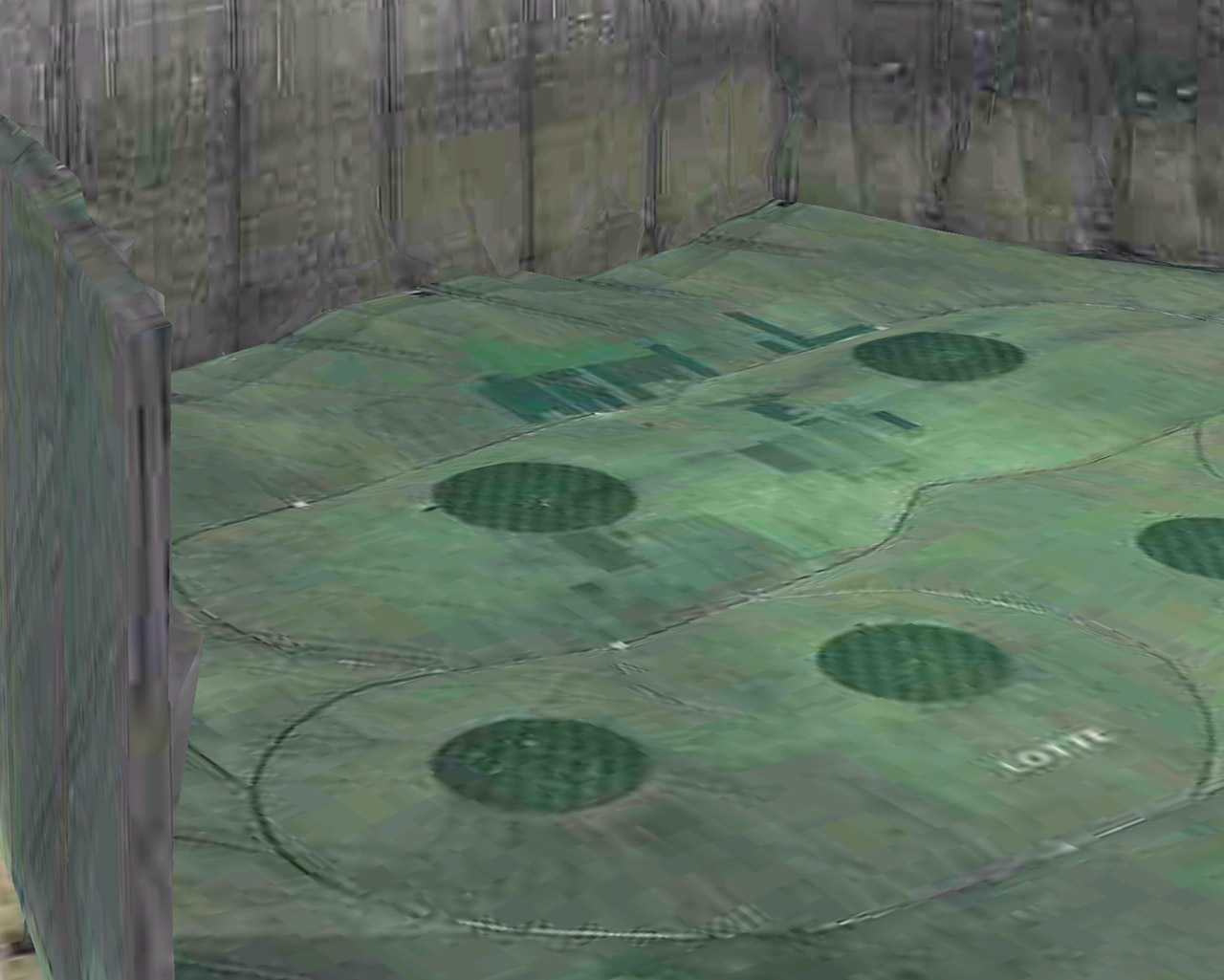

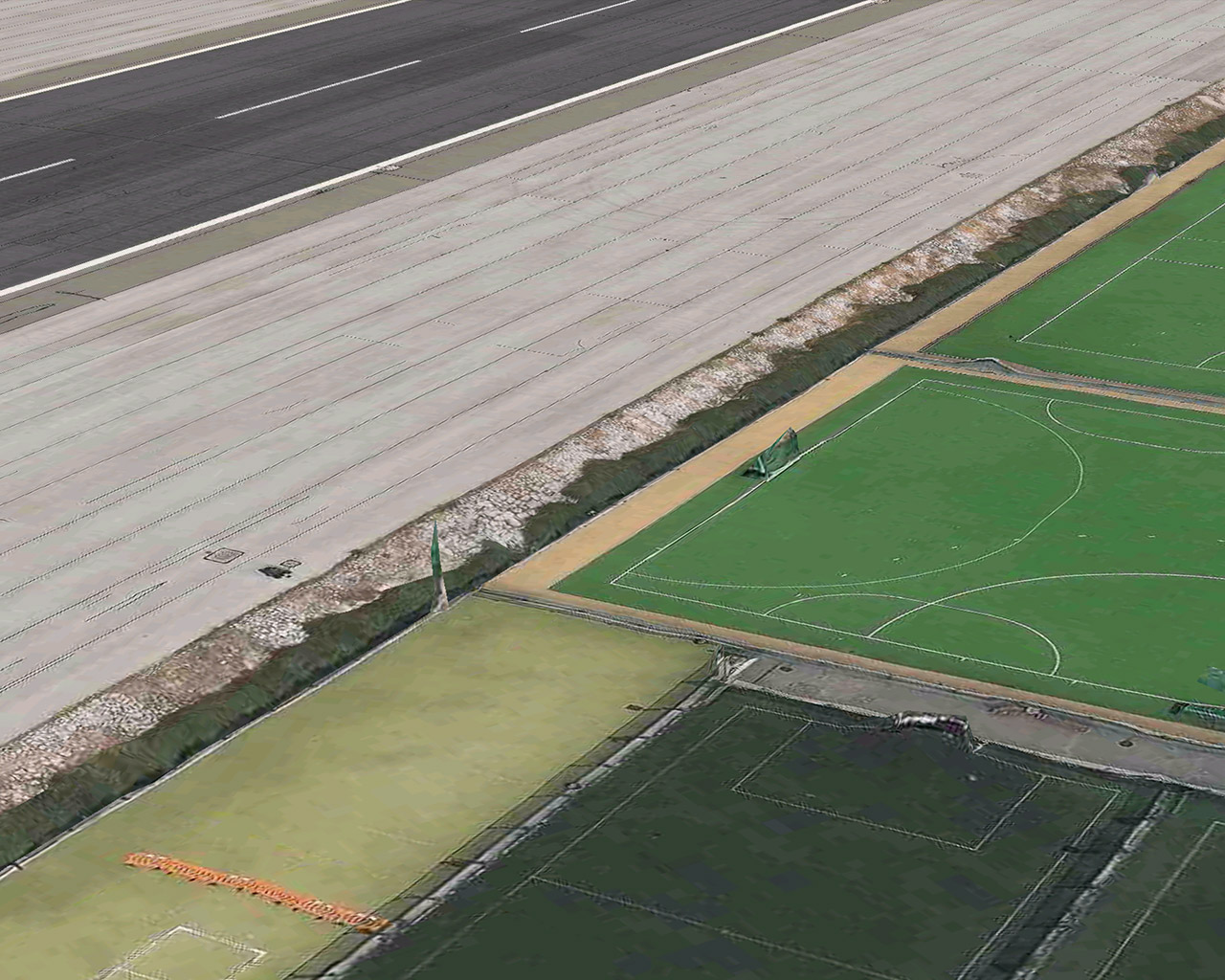

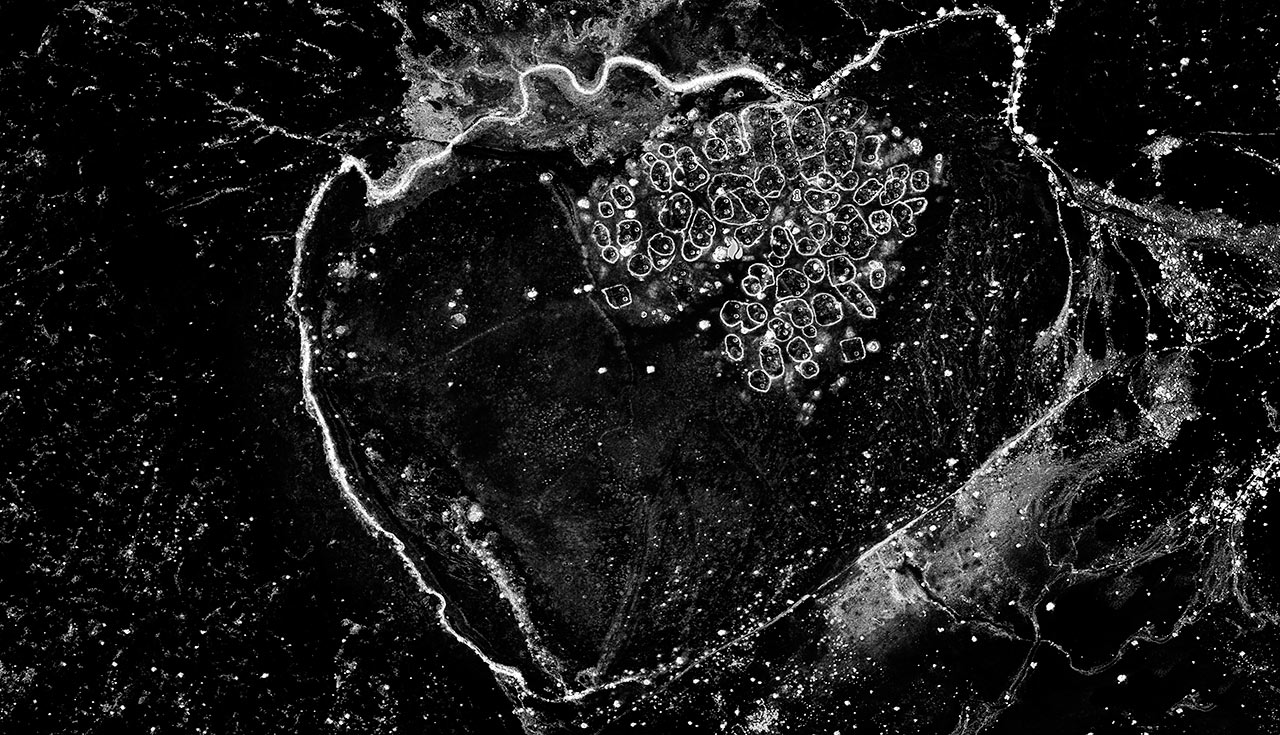

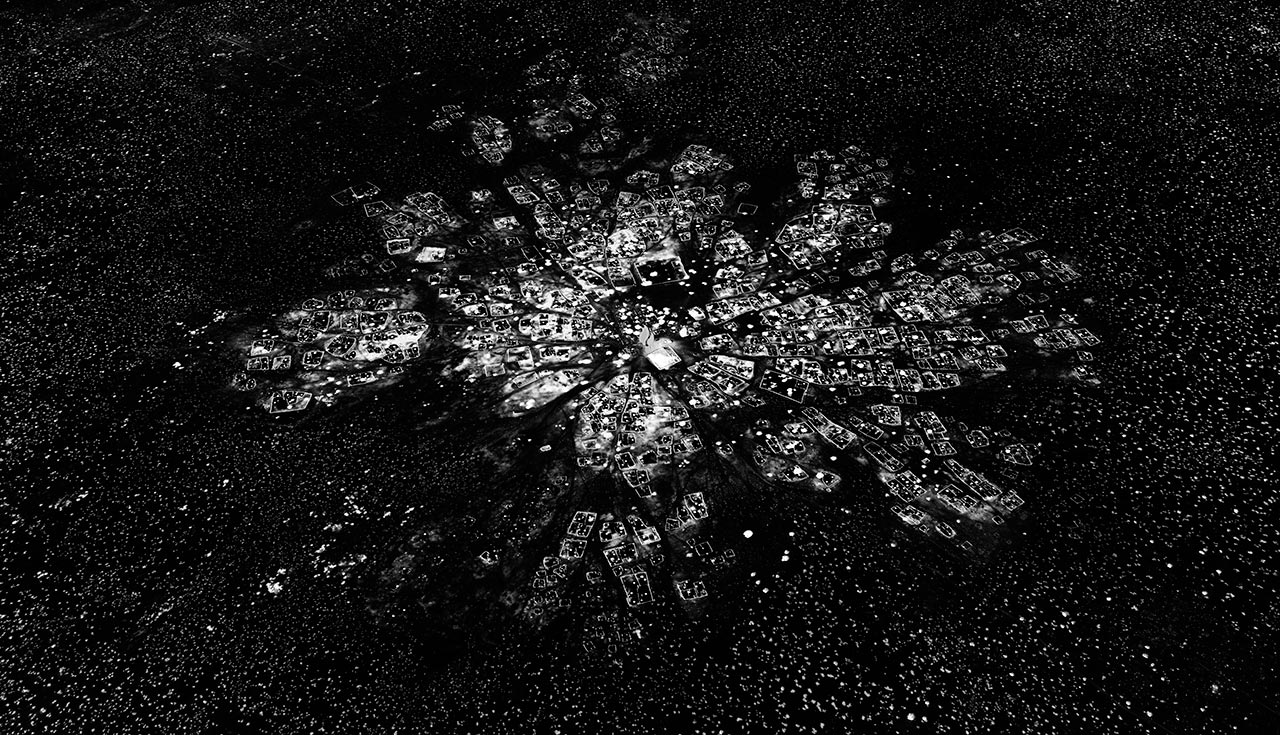

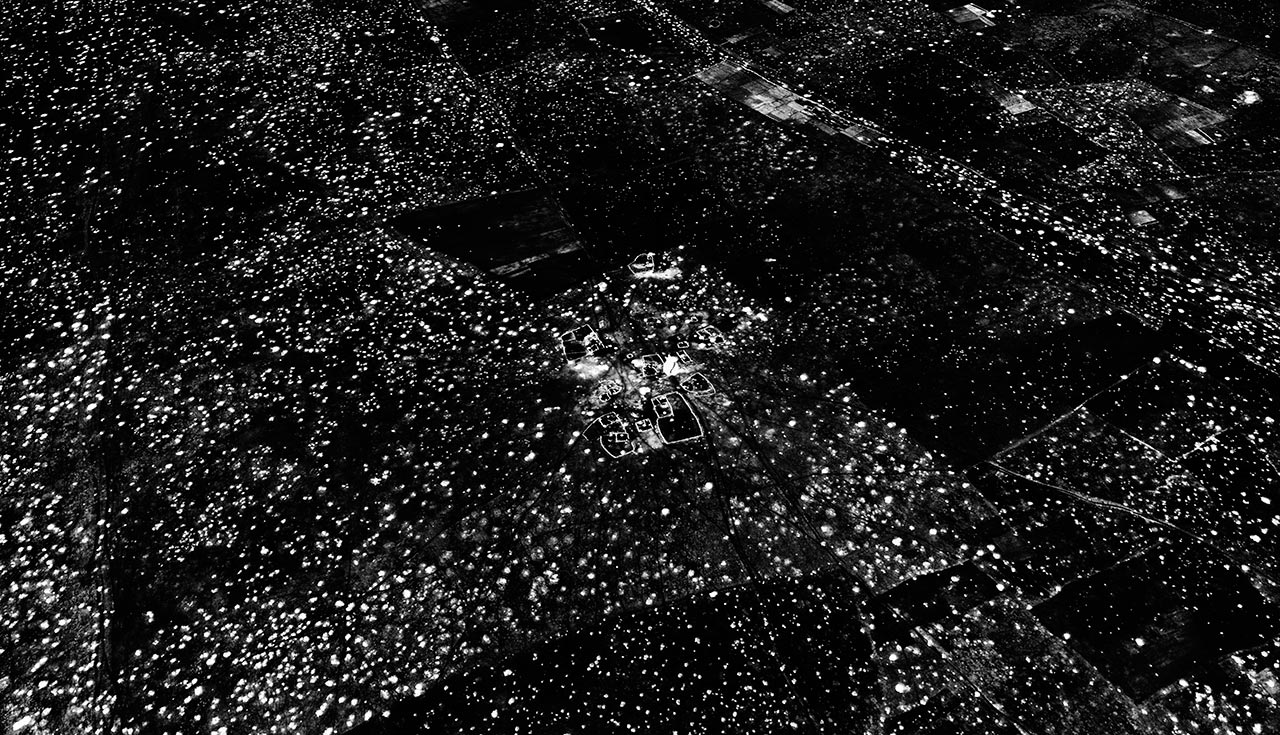

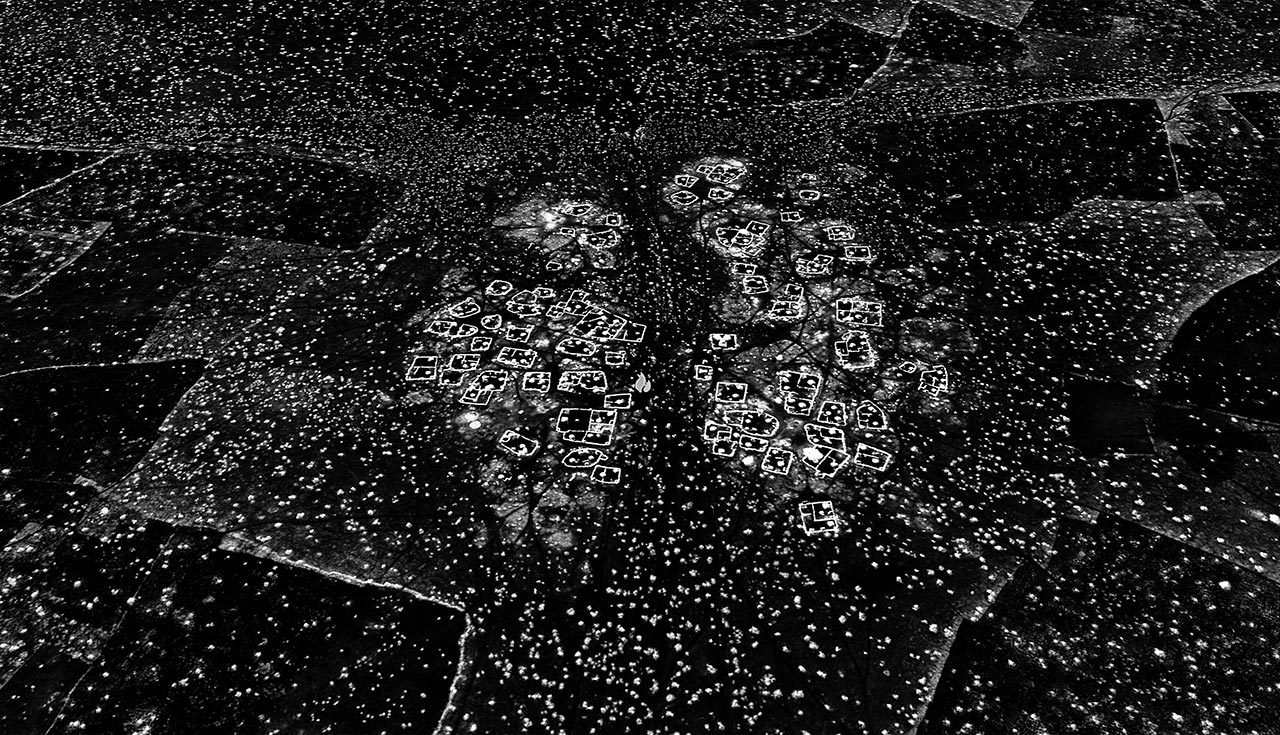

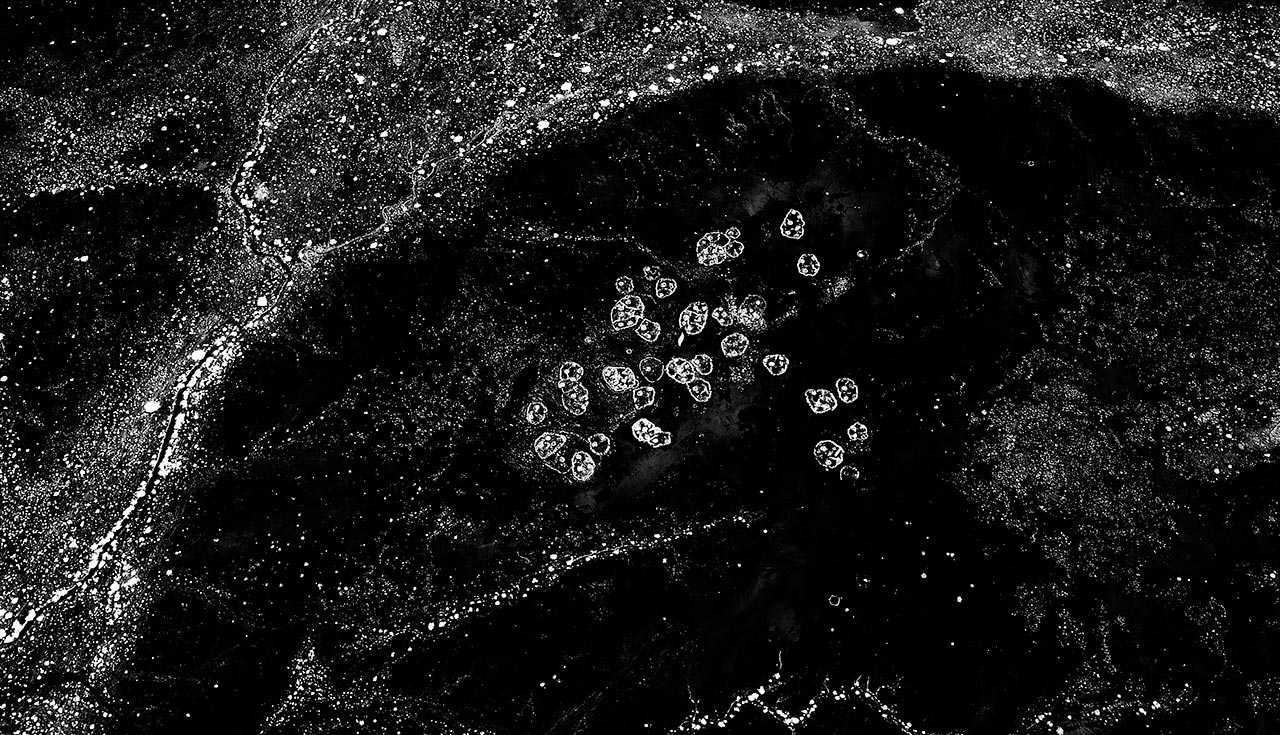

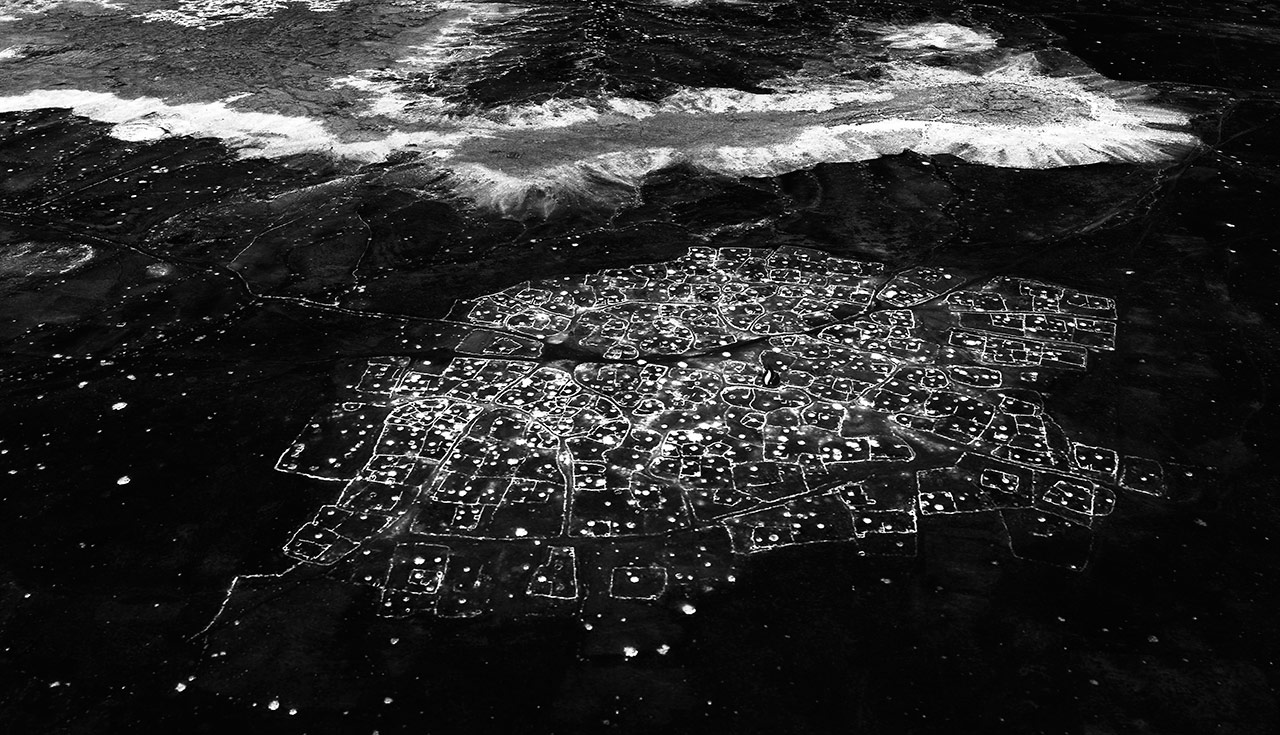

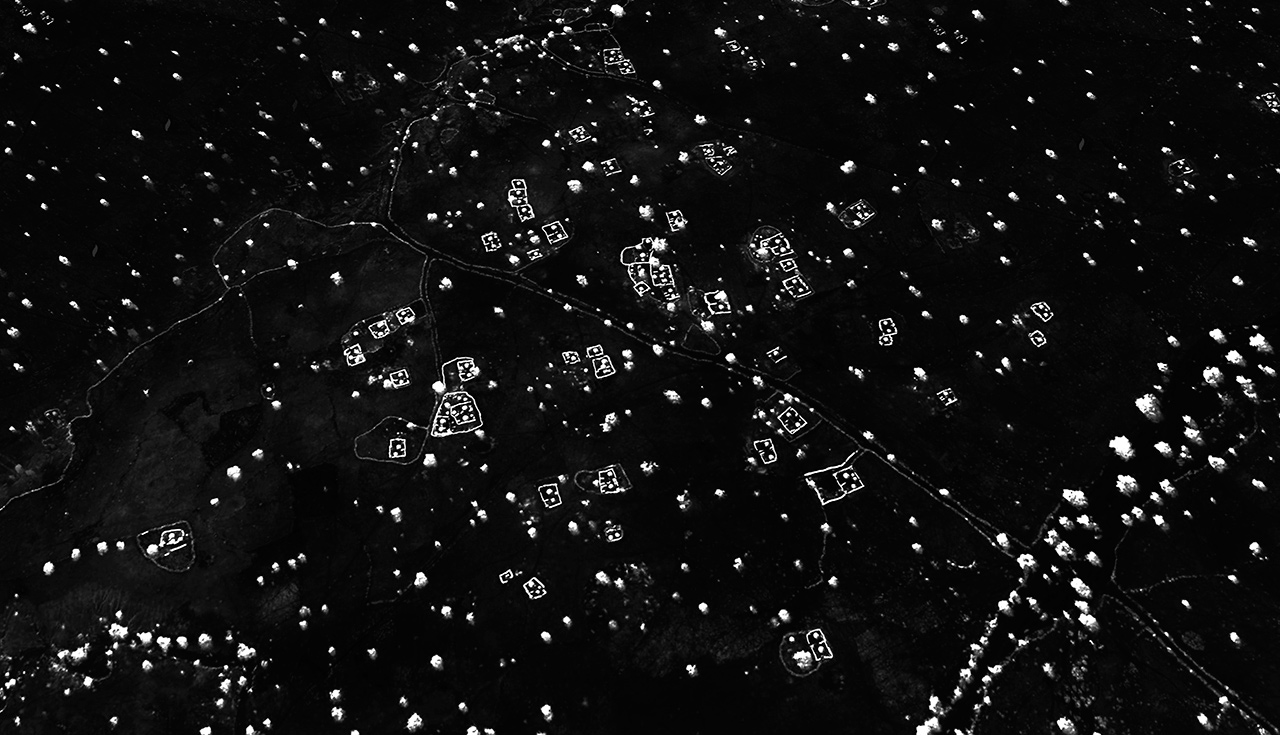

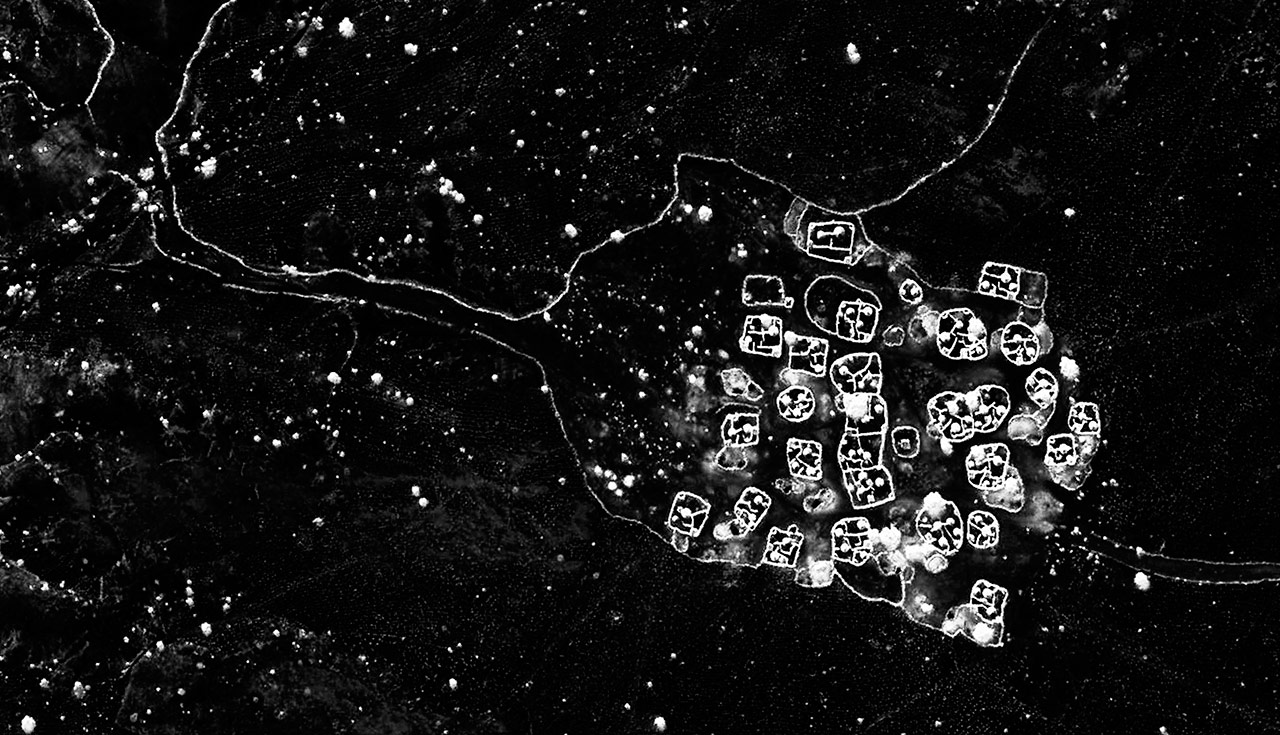

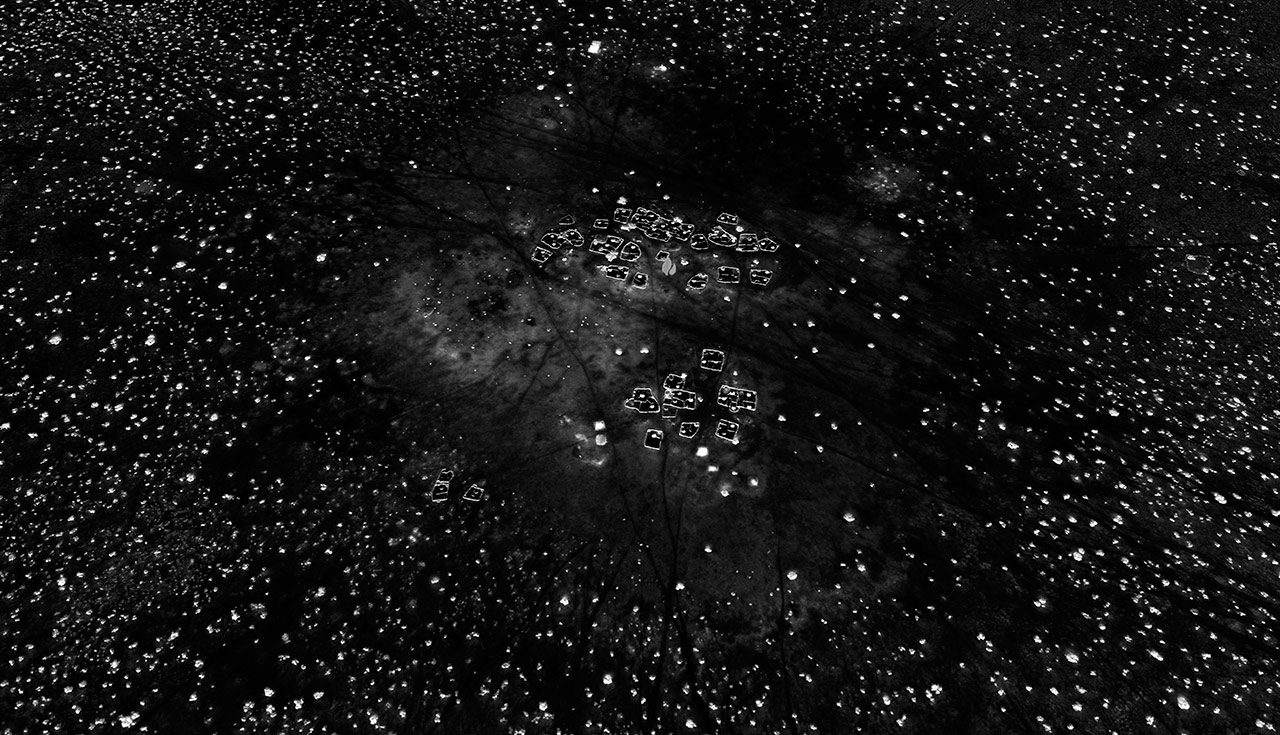

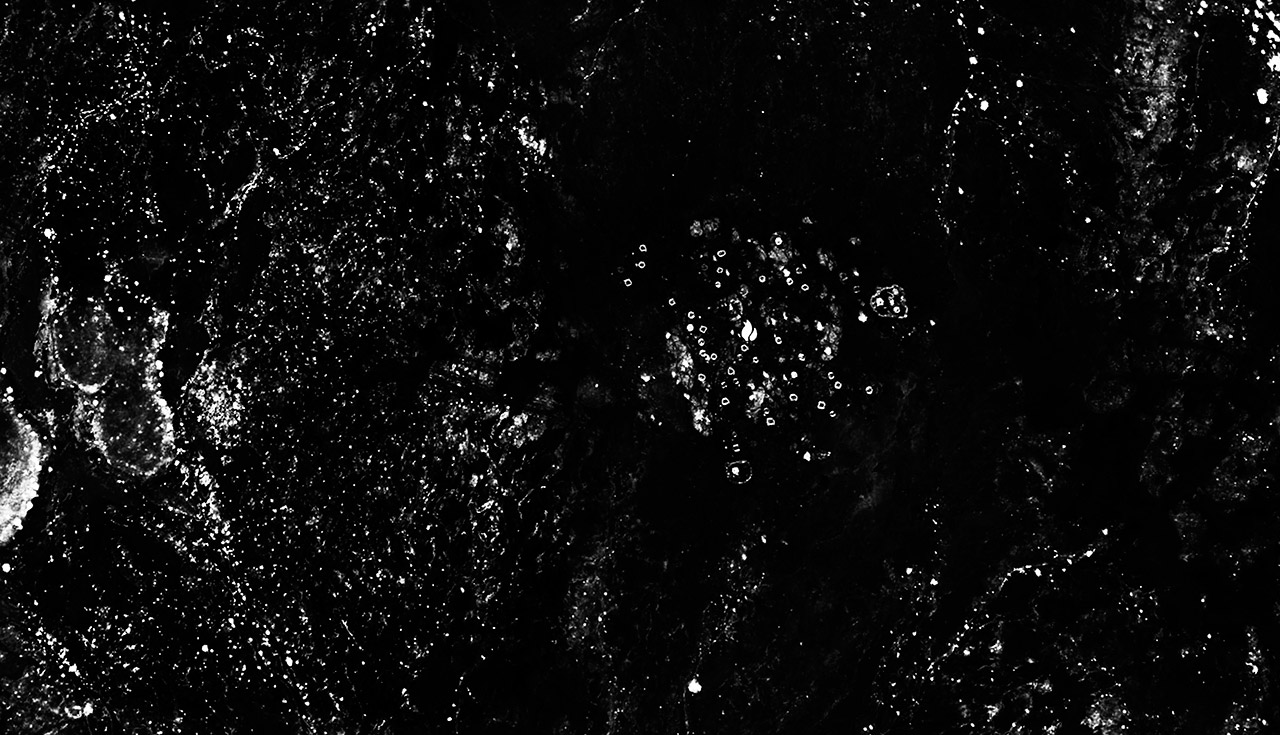

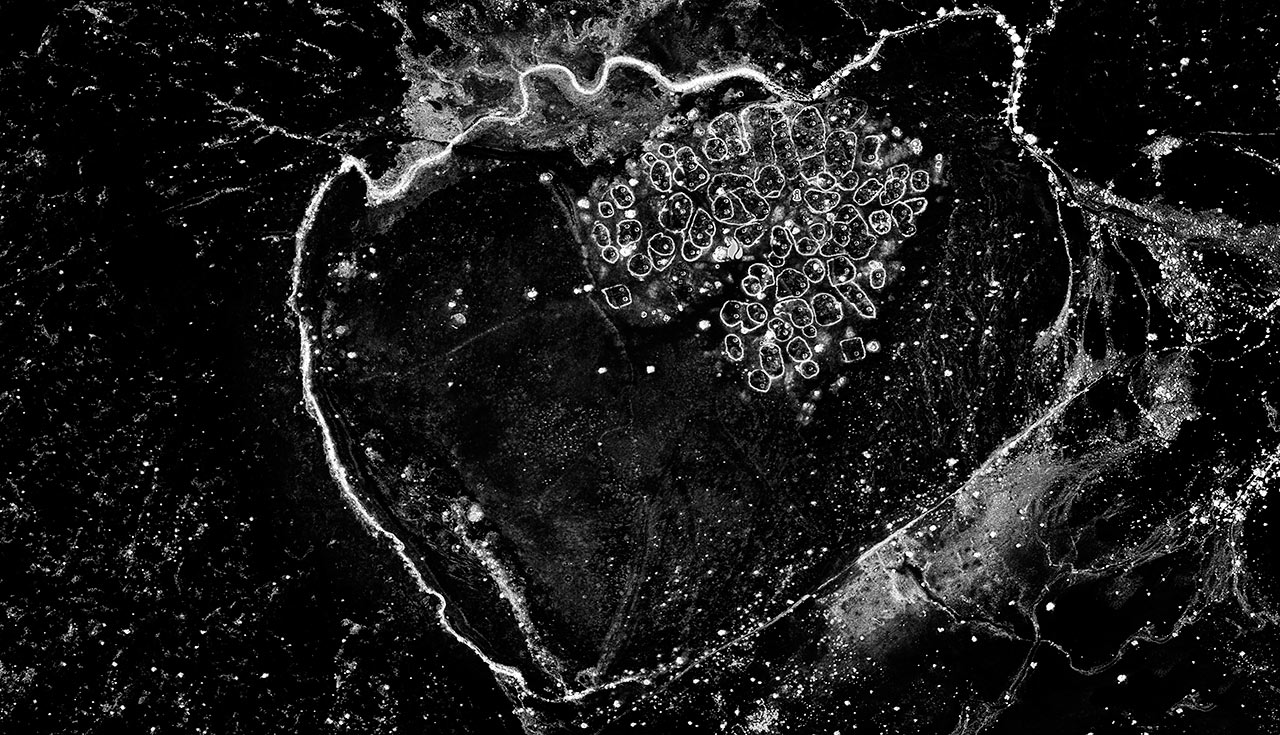

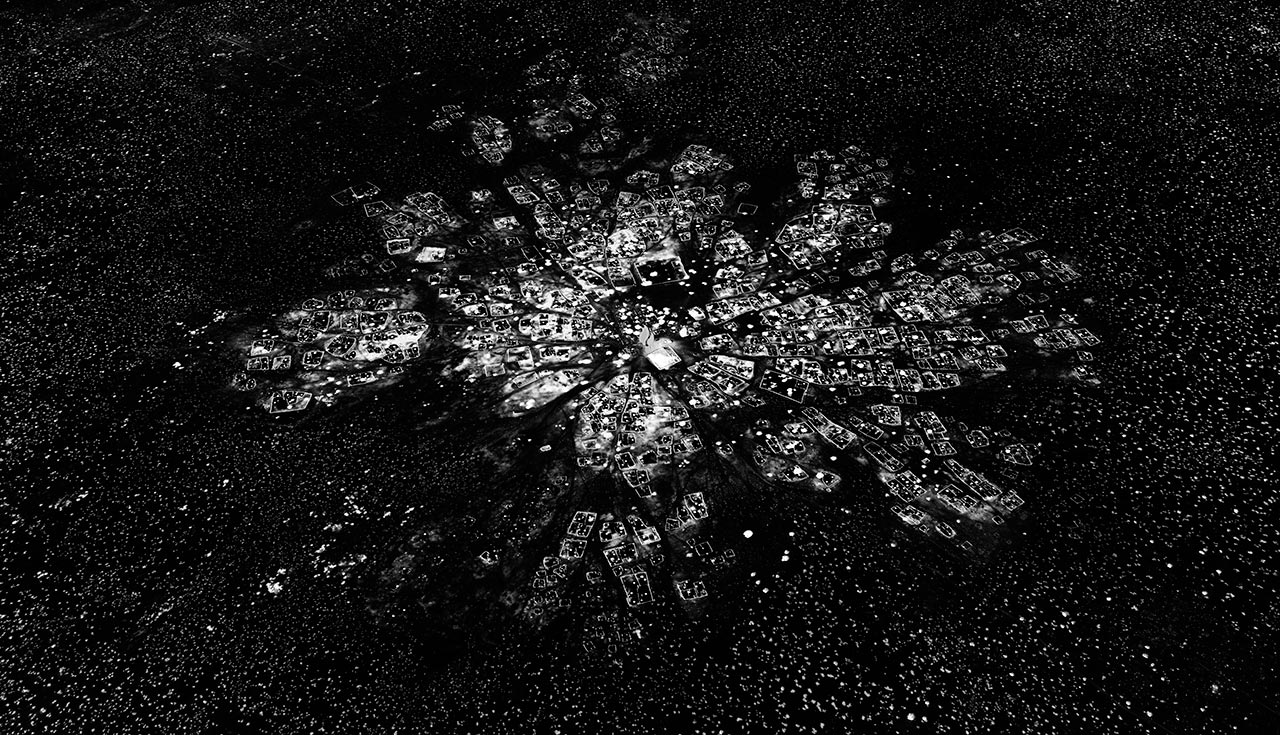

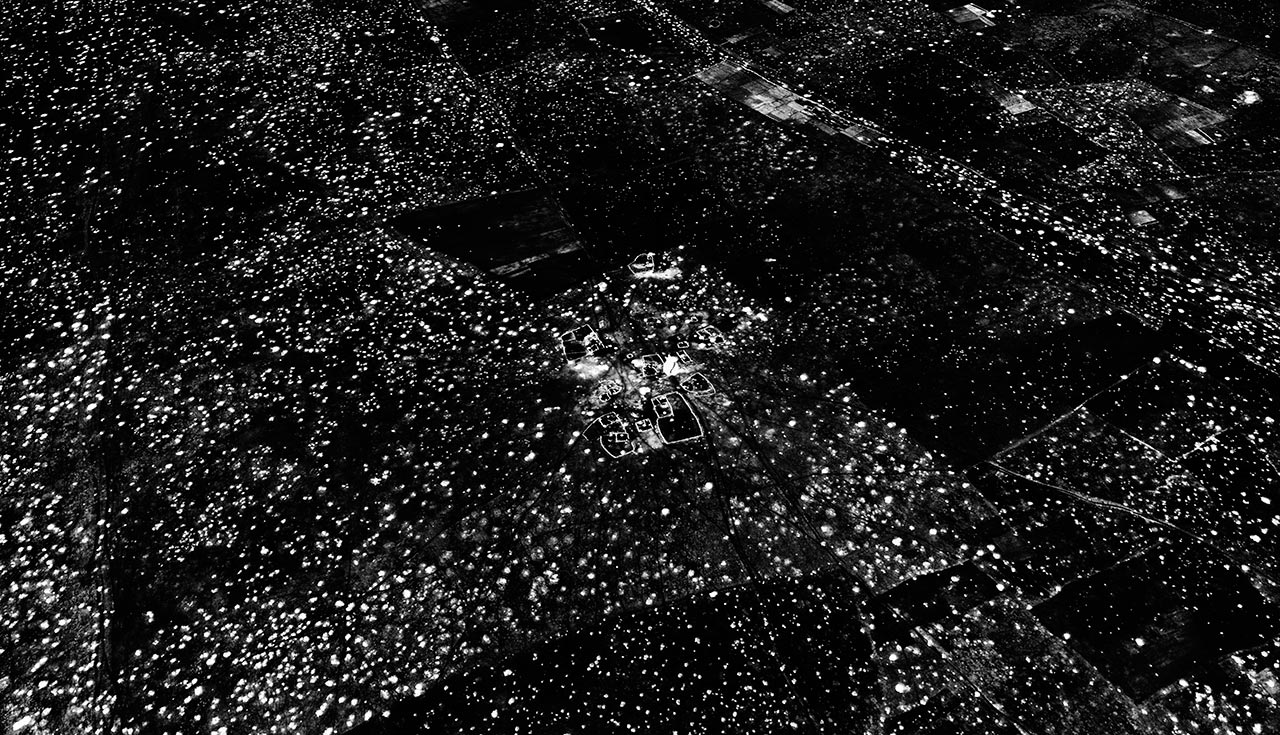

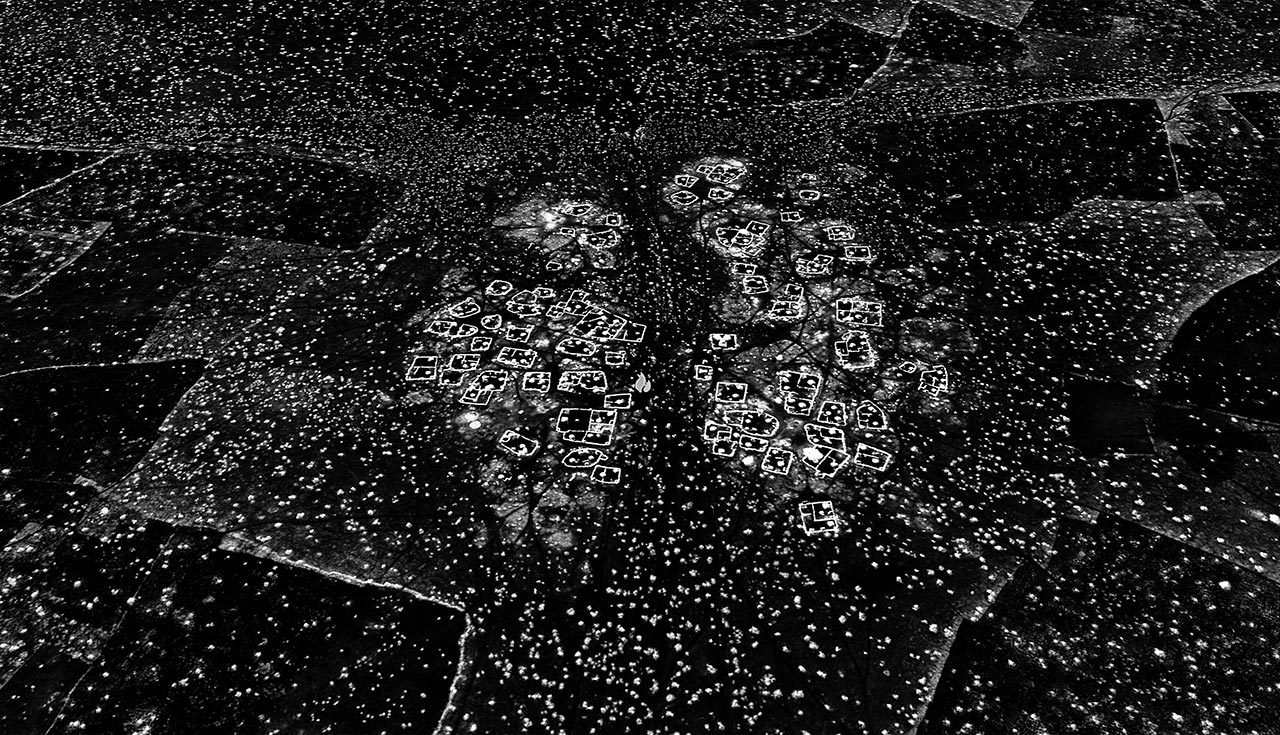

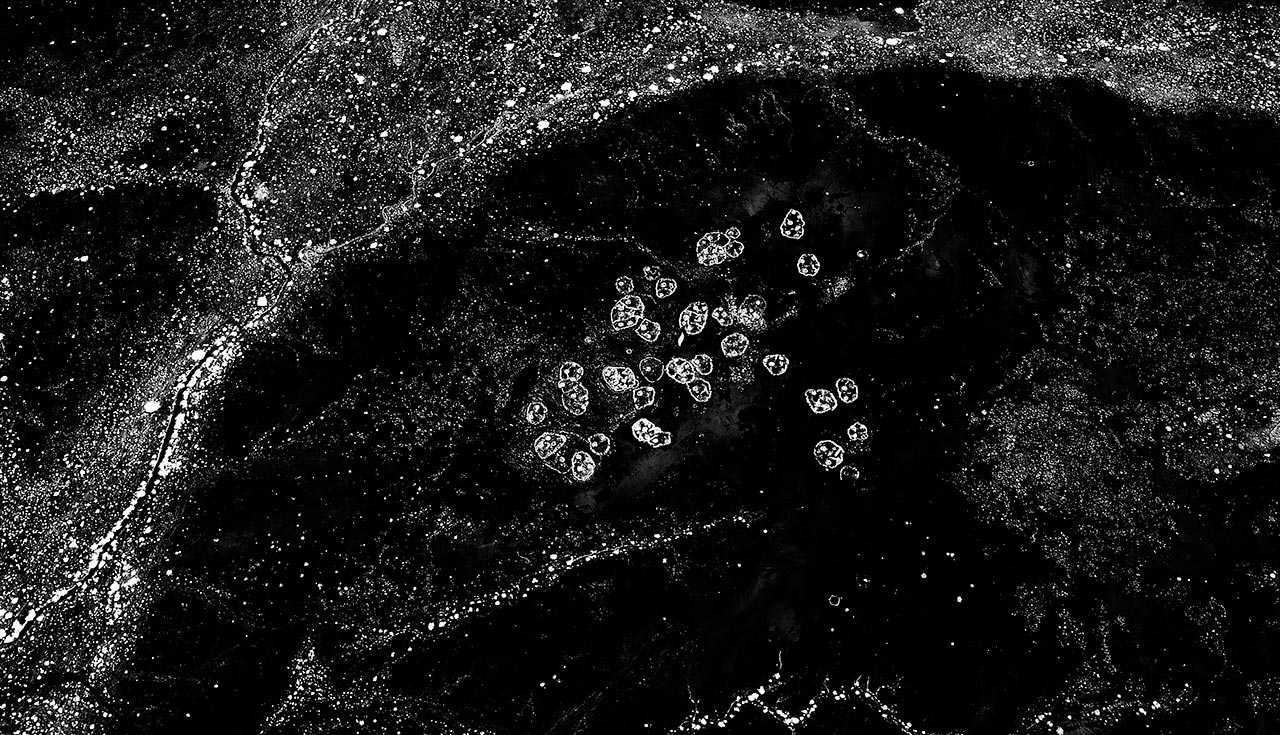

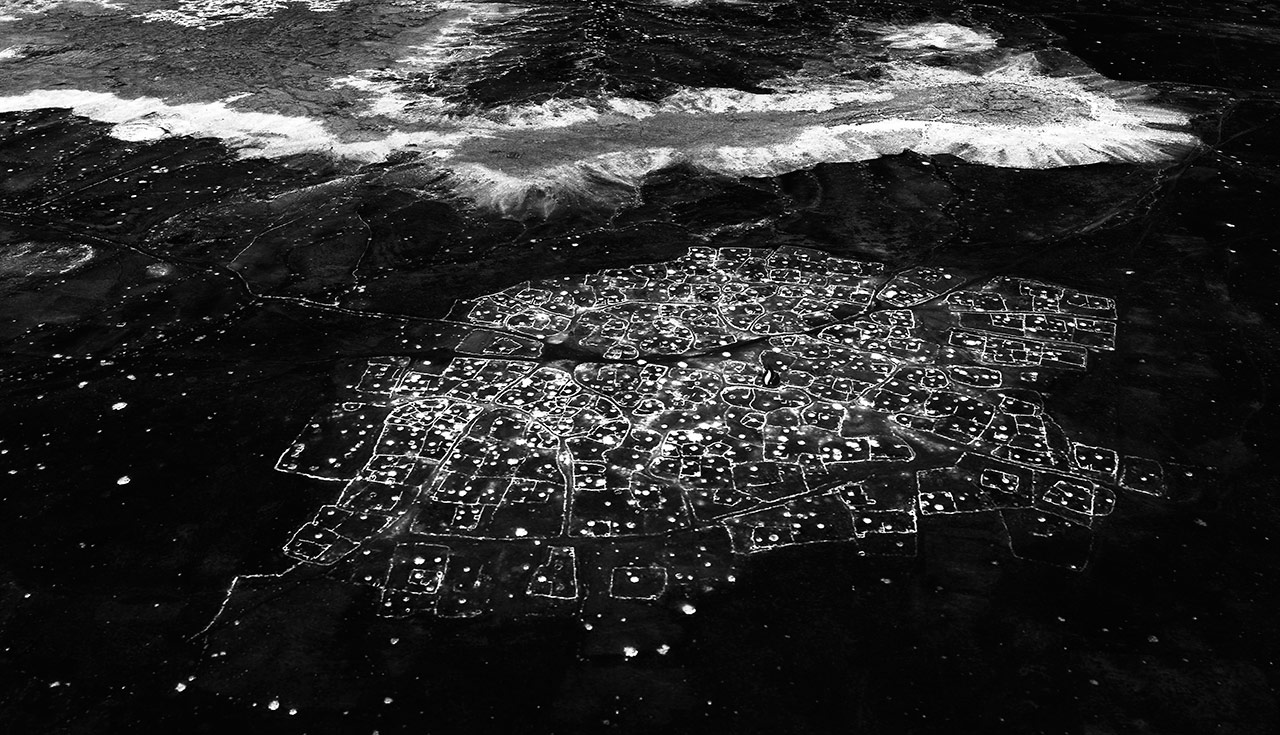

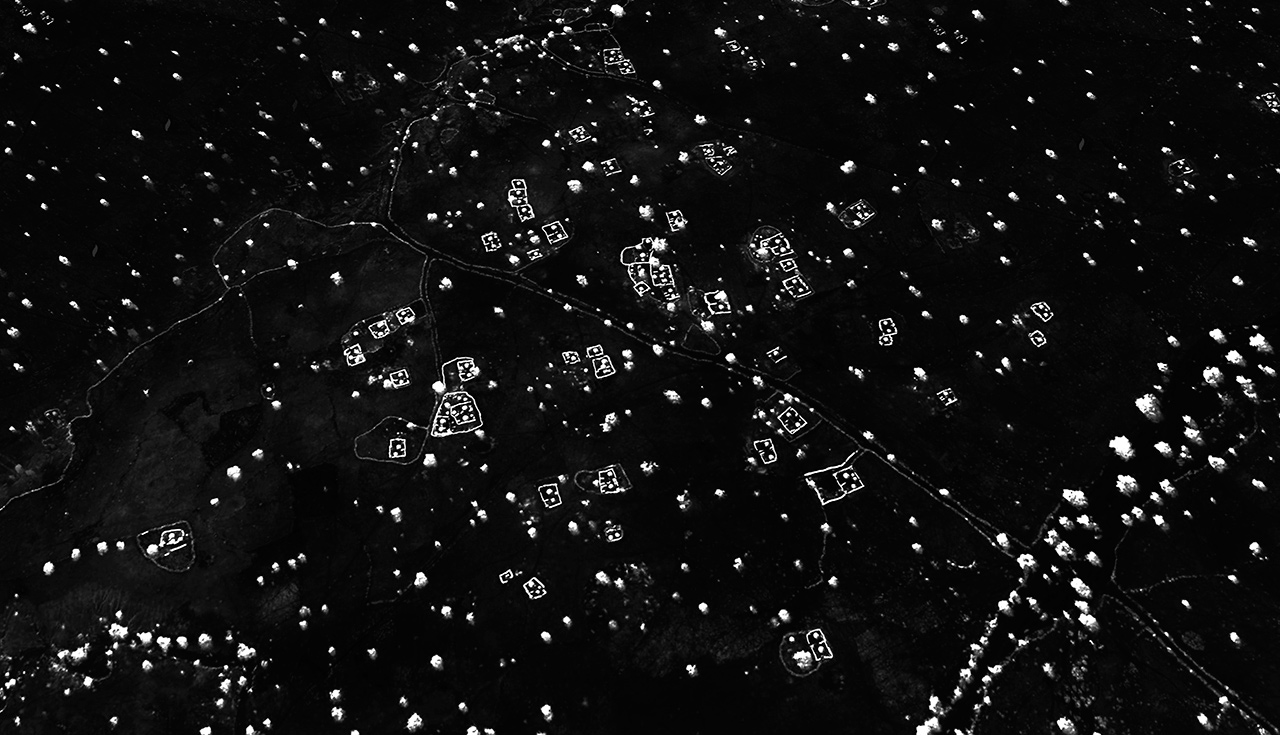

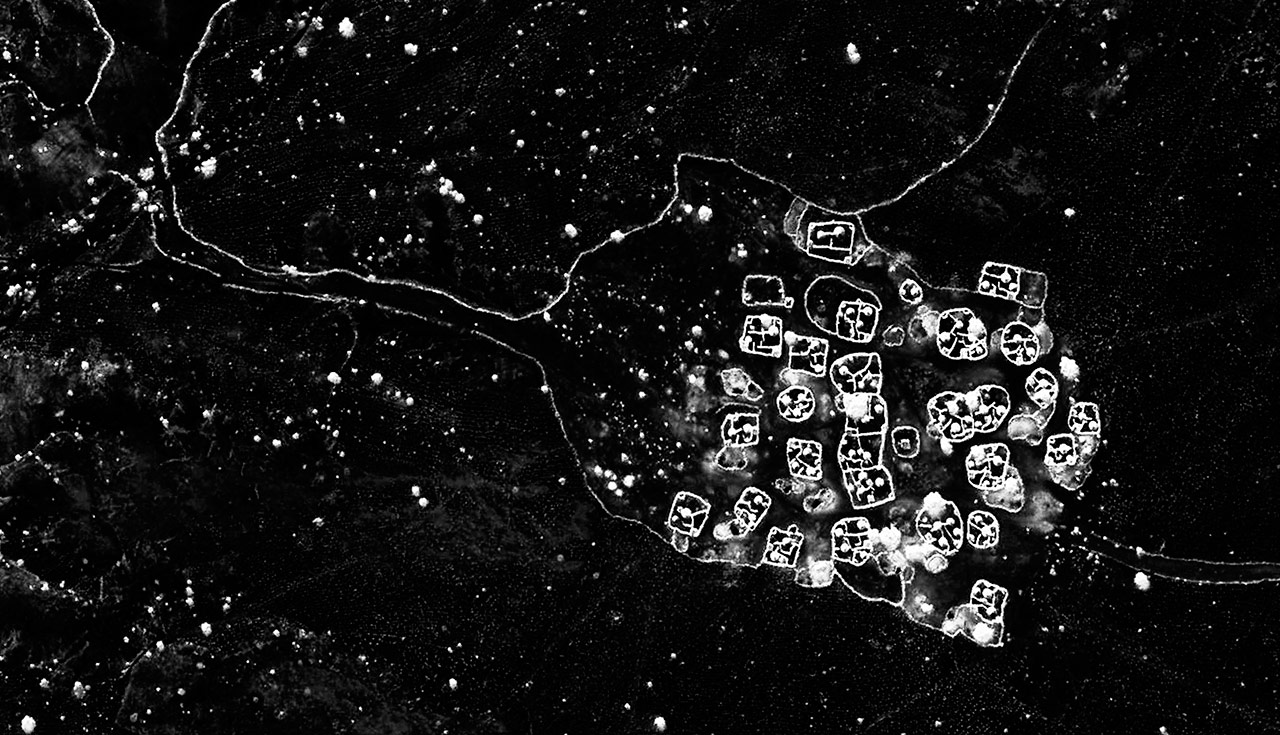

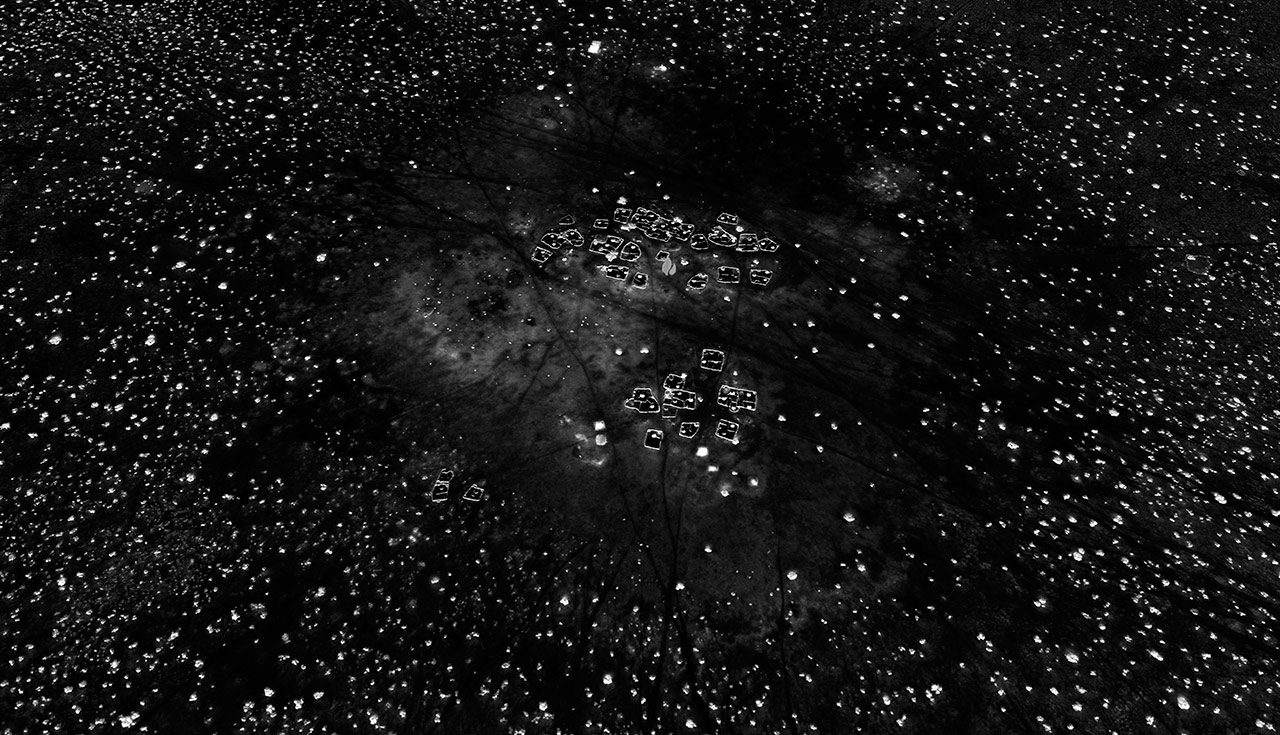

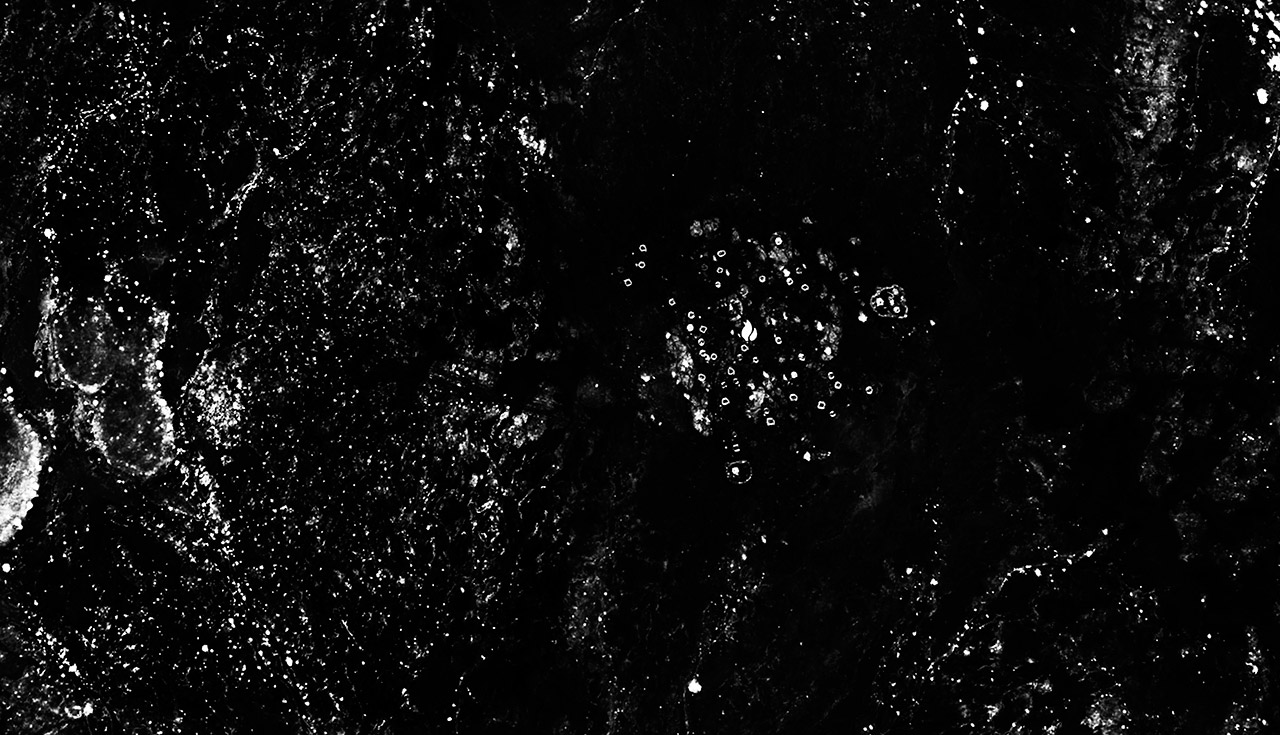

Expeditions into the 3D World of Apple Maps

Since September 2012, Apple has offered a mapping service application developed for its iOS6 operating system. Using a new form of 3D imaging, it displays the centers of mainly American cities. The application’s renderings of buildings and streets have elicited criticism and mockery, since the maps and the corresponding images are not without errors... It is these “errors” that provide the point of departure for the project The Rendering Eye. […]

The Apple Maps program produces cityscapes that are the pure invention of ceaselessly calculating image-generating machines and that show real places even so. These places are simultaneously strange and familiar. Familiar, because they are streets we can walk on, houses we can live in, and intersections we can stand at; yet also strange, because we are denied the pedestrian’s perspective. […]

The fact that Apple is currently working on improving the database of its renderings already heralds the end of the special quality of these images: soon […] the algorithms will have been refined and the visualizations of reality so perfected that these cartographic images will turn into simulated immediacy, and thereby become artlessly mimetic. At that point the 3D renderings will no longer produce a picture, but rather a flat image that will be indistinguishable from a photograph – a photograph which, for its part, will no longer be distinguishable from a rendered image. In light of this anticipated development, the screen shots […] are already a memory of a future past, when computer-generated cityscapes were still “picturesque.” 1

1. For the complete text, see:

http://www.renderingeye.net/projects_content.php?project_id=999&typ=project

Regula Bochsler (Switzerland). Journalist, historian and documentary filmmaker. Regula has focused on an extensive and diverse range of subjects, including the Internet, prostitution, the labor movement, advertising, feminism, media theory, U.S. influence on European culture and numerous other social, cultural and political topics. Among her publications are: The Rendering Eye. Urban America Revisited (Zurich, 2014), Leaving Reality Behind: etoy vs eToys.com & Other Battles to Control Cyberspace (NY, 2002): Co-authored with Adam Wishart and Ich folgte meinem Stern. Das kämpferische Leben der Margarethe Hardegger (2004): I Followed My Star: The Combative Life of Margarethe Hardegger.

Regula Bochsler (Switzerland). Journalist, historian and documentary filmmaker. Regula has focused on an extensive and diverse range of subjects, including the Internet, prostitution, the labor movement, advertising, feminism, media theory, U.S. influence on European culture and numerous other social, cultural and political topics. Among her publications are: The Rendering Eye. Urban America Revisited (Zurich, 2014), Leaving Reality Behind: etoy vs eToys.com & Other Battles to Control Cyberspace (NY, 2002): Co-authored with Adam Wishart and Ich folgte meinem Stern. Das kämpferische Leben der Margarethe Hardegger (2004): I Followed My Star: The Combative Life of Margarethe Hardegger.

Expeditions into the 3D World of Apple Maps

Since September 2012, Apple has offered a mapping service application developed for its iOS6 operating system. Using a new form of 3D imaging, it displays the centers of mainly American cities. The application’s renderings of buildings and streets have elicited criticism and mockery, since the maps and the corresponding images are not without errors... It is these “errors” that provide the point of departure for the project The Rendering Eye. […]

The Apple Maps program produces cityscapes that are the pure invention of ceaselessly calculating image-generating machines and that show real places even so. These places are simultaneously strange and familiar. Familiar, because they are streets we can walk on, houses we can live in, and intersections we can stand at; yet also strange, because we are denied the pedestrian’s perspective. […]

The fact that Apple is currently working on improving the database of its renderings already heralds the end of the special quality of these images: soon […] the algorithms will have been refined and the visualizations of reality so perfected that these cartographic images will turn into simulated immediacy, and thereby become artlessly mimetic. At that point the 3D renderings will no longer produce a picture, but rather a flat image that will be indistinguishable from a photograph – a photograph which, for its part, will no longer be distinguishable from a rendered image. In light of this anticipated development, the screen shots […] are already a memory of a future past, when computer-generated cityscapes were still “picturesque.” 1

1. For the complete text, see:

http://www.renderingeye.net/projects_content.php?project_id=999&typ=project

Regula Bochsler (Switzerland). Journalist, historian and documentary filmmaker. Regula has focused on an extensive and diverse range of subjects, including the Internet, prostitution, the labor movement, advertising, feminism, media theory, U.S. influence on European culture and numerous other social, cultural and political topics. Among her publications are: The Rendering Eye. Urban America Revisited (Zurich, 2014), Leaving Reality Behind: etoy vs eToys.com & Other Battles to Control Cyberspace (NY, 2002): Co-authored with Adam Wishart and Ich folgte meinem Stern. Das kämpferische Leben der Margarethe Hardegger (2004): I Followed My Star: The Combative Life of Margarethe Hardegger.

Regula Bochsler (Switzerland). Journalist, historian and documentary filmmaker. Regula has focused on an extensive and diverse range of subjects, including the Internet, prostitution, the labor movement, advertising, feminism, media theory, U.S. influence on European culture and numerous other social, cultural and political topics. Among her publications are: The Rendering Eye. Urban America Revisited (Zurich, 2014), Leaving Reality Behind: etoy vs eToys.com & Other Battles to Control Cyberspace (NY, 2002): Co-authored with Adam Wishart and Ich folgte meinem Stern. Das kämpferische Leben der Margarethe Hardegger (2004): I Followed My Star: The Combative Life of Margarethe Hardegger.Alejandro Malo

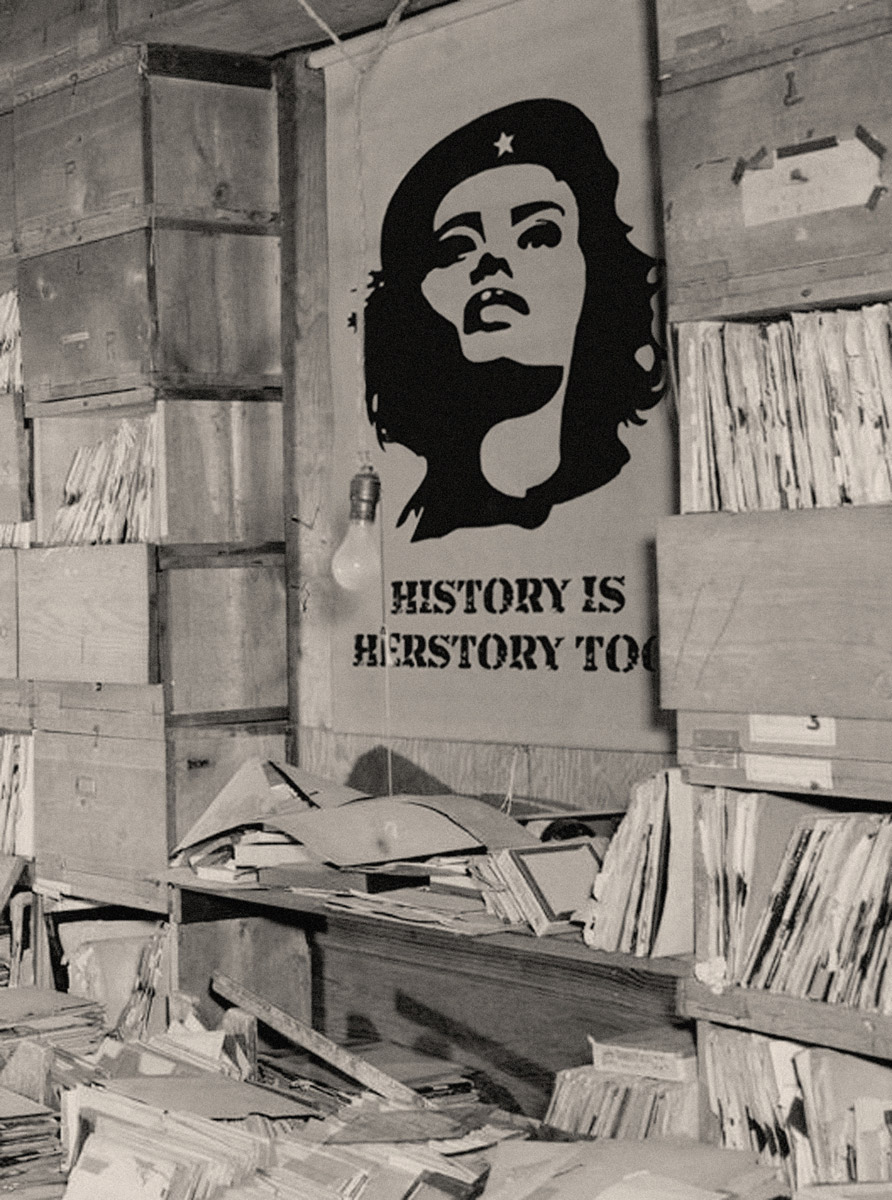

In Postproduction, I try to show that artists' intuitive relationship with art history is now going beyond what we call "the art of appropriation," which naturally infers an ideology of ownership, and moving toward a culture of the use of forms, a culture of constant activity of signs based on a collective ideal: sharing. —Nicolas Bourriaud.

Scene of the film Metropolis by Fritz Lang, 1927.

For some time now, the resource of appropriation in photography has gone from being a subversive and provocative act to being, in many cases, the catch phrase which seeks to associate the prestige of previous artworks and contexts with fresh projects. The very concept of appropriation assumes the possibility of appropriating a material aspect of an image which is becoming more and more intangible. Due to the increasing production, consumption and transformation of images in a digital format, there is now an infinite number of possible reincarnations of not only every photograph, but also of its copies and variants, and of other photographs which it references, parodies or recreates. This never-ending cascade of repetitions and similarities has rendered unnecessary any fight against the concepts of originality and authorship, which only a few decades ago, it seemed essential to question. Originality, at risk of showing itself up with touching naivety, has not evolved from being a different arrangement of very well-known elements. Similarly, authorship hardly ends up as the top hat from which, like a rabbit, a well-edited design made up of materials uploaded from almost indistinguishable references will appear. In such a scenario, what does artwork openly based on somebody else’s material suggest? What question does it raise and what answer does it provide? Or, ideally, what question would it raise and what answer would it give so as not to remain merely a superficial resource?

The first step in formulating a response is to recognize that the boundaries of this practice are imprecise. It is impossible to define the point at which the reinterpretation of archived material or their intervention turns into a practice of visual recycling and rewriting of its meaning. If we add to this catalogue of practices, collages and photo montages, as well as the found footage and the capture of three- dimensional representations (for example, Street View or Apple Maps), then the territory becomes immeasurable. However, perhaps it is this complexity itself that is the first supporting point: a project that is constructed from a remix does not conceal its debt to other sources, and instead demonstrates its aim of proposing a new interpretation of them, albeit in a modest way. This in itself highlights an ethical concern with respect to the rule of images. Here lies a commitment to not only inviting a reflective way of looking at a universe that already exists but also a desire to add meaning to this universe. This leads us to the following conclusion: a project of this kind calls for contextual boundaries to be fixed. In order to create a new meaning it is fundamental to acknowledge previous meanings and references. Whether this is achieved by means of footnotes, marginal notes or definition by the micro universe itself regarding the selection and shots it comprises, or even the sum of a variety of these resources, the result is always one step further away from the original sources.

Finally, making the effort to acknowledge the fact that an image derives from previous artwork and that it aspires to become part of a context allows us to deduce a final characteristic of these designs, a characteristic that we can call the ecology of photographic recycling. In a world in which images are created at an extraordinary pace and in which every image can be disposable, appropriation acknowledges that images can take on new meanings and be enriched by broader meanings. The unstoppable avalanche of production comes face to face with the reasoned observation of reproduction and the modest judgment of post-production. The decreasing value of originality counters analysis, and the curator’s panoramic vision opposes the author’s perspective.

If we admit that in between the practices of appropriation and remix lies a need for ethics and ecology, which themselves require individual assessment and research, perhaps we can better measure the current relevance of the latest designs and recognize the scope of each one. If we accept that this new economy of shared property adds as much economic value as it does symbolic value, perhaps we will then have more factors related to our notions about intellectual property to adjust to a more progressive framework. The questions from the photographic world - in which there is so much to see and so much to understand - are timely and certainly worth acknowledging. Are we capable of doing so?

Alejandro Malo (Mexico, 1972). Lives and works in Mexico and is the director of ZoneZero. Since 1993, he has taken part in various cultural projects and worked as an information technology consultant. He has collaborated in print and electronic publications, and given workshops and conferences on literature, creative writing, storytelling and technology. In 2009, Malo joined the team of the Fundación Pedro Meyer, where he directs the Archives and Technology departments.

Alejandro Malo (Mexico, 1972). Lives and works in Mexico and is the director of ZoneZero. Since 1993, he has taken part in various cultural projects and worked as an information technology consultant. He has collaborated in print and electronic publications, and given workshops and conferences on literature, creative writing, storytelling and technology. In 2009, Malo joined the team of the Fundación Pedro Meyer, where he directs the Archives and Technology departments.[core_state] => 1 [core_access] => 1 [core_metadata] => {"robots":"","author":"Alejandro Malo","rights":"","xreference":""} [core_created_user_id] => 838 [core_created_by_alias] => [core_created_time] => 2015-10-12 06:02:21 [core_images] => {"image_intro":"images\/categories\/apropiacion\/metropolis.gif","float_intro":"","image_intro_alt":"","image_intro_caption":"","image_fulltext":"images\/categories\/apropiacion\/metropolis.gif","float_fulltext":"","image_fulltext_alt":"","image_fulltext_caption":""} [core_modified_time] => 2016-05-19 17:00:34 [core_language] => en-GB [core_catid] => 63 [core_publish_up] => 2015-10-12 06:02:21 [core_publish_down] => 0000-00-00 00:00:00 [content_type_title] => Article [router] => ContentHelperRoute::getArticleRoute [author] => Elisa Rugo [author_email] => elisa@zonezero.com [link] => index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=331:appropriation-and-remix&catid=63&lang=en-GB [displayDate] => 2015-10-12 06:02:21 [event] => stdClass Object ( [afterDisplayTitle] => [beforeDisplayContent] => [afterDisplayContent] => ) [text] =>

In Postproduction, I try to show that artists' intuitive relationship with art history is now going beyond what we call "the art of appropriation," which naturally infers an ideology of ownership, and moving toward a culture of the use of forms, a culture of constant activity of signs based on a collective ideal: sharing. —Nicolas Bourriaud.

Scene of the film Metropolis by Fritz Lang, 1927.

For some time now, the resource of appropriation in photography has gone from being a subversive and provocative act to being, in many cases, the catch phrase which seeks to associate the prestige of previous artworks and contexts with fresh projects. The very concept of appropriation assumes the possibility of appropriating a material aspect of an image which is becoming more and more intangible. Due to the increasing production, consumption and transformation of images in a digital format, there is now an infinite number of possible reincarnations of not only every photograph, but also of its copies and variants, and of other photographs which it references, parodies or recreates. This never-ending cascade of repetitions and similarities has rendered unnecessary any fight against the concepts of originality and authorship, which only a few decades ago, it seemed essential to question. Originality, at risk of showing itself up with touching naivety, has not evolved from being a different arrangement of very well-known elements. Similarly, authorship hardly ends up as the top hat from which, like a rabbit, a well-edited design made up of materials uploaded from almost indistinguishable references will appear. In such a scenario, what does artwork openly based on somebody else’s material suggest? What question does it raise and what answer does it provide? Or, ideally, what question would it raise and what answer would it give so as not to remain merely a superficial resource?

The first step in formulating a response is to recognize that the boundaries of this practice are imprecise. It is impossible to define the point at which the reinterpretation of archived material or their intervention turns into a practice of visual recycling and rewriting of its meaning. If we add to this catalogue of practices, collages and photo montages, as well as the found footage and the capture of three- dimensional representations (for example, Street View or Apple Maps), then the territory becomes immeasurable. However, perhaps it is this complexity itself that is the first supporting point: a project that is constructed from a remix does not conceal its debt to other sources, and instead demonstrates its aim of proposing a new interpretation of them, albeit in a modest way. This in itself highlights an ethical concern with respect to the rule of images. Here lies a commitment to not only inviting a reflective way of looking at a universe that already exists but also a desire to add meaning to this universe. This leads us to the following conclusion: a project of this kind calls for contextual boundaries to be fixed. In order to create a new meaning it is fundamental to acknowledge previous meanings and references. Whether this is achieved by means of footnotes, marginal notes or definition by the micro universe itself regarding the selection and shots it comprises, or even the sum of a variety of these resources, the result is always one step further away from the original sources.

Finally, making the effort to acknowledge the fact that an image derives from previous artwork and that it aspires to become part of a context allows us to deduce a final characteristic of these designs, a characteristic that we can call the ecology of photographic recycling. In a world in which images are created at an extraordinary pace and in which every image can be disposable, appropriation acknowledges that images can take on new meanings and be enriched by broader meanings. The unstoppable avalanche of production comes face to face with the reasoned observation of reproduction and the modest judgment of post-production. The decreasing value of originality counters analysis, and the curator’s panoramic vision opposes the author’s perspective.

If we admit that in between the practices of appropriation and remix lies a need for ethics and ecology, which themselves require individual assessment and research, perhaps we can better measure the current relevance of the latest designs and recognize the scope of each one. If we accept that this new economy of shared property adds as much economic value as it does symbolic value, perhaps we will then have more factors related to our notions about intellectual property to adjust to a more progressive framework. The questions from the photographic world - in which there is so much to see and so much to understand - are timely and certainly worth acknowledging. Are we capable of doing so?

Alejandro Malo (Mexico, 1972). Lives and works in Mexico and is the director of ZoneZero. Since 1993, he has taken part in various cultural projects and worked as an information technology consultant. He has collaborated in print and electronic publications, and given workshops and conferences on literature, creative writing, storytelling and technology. In 2009, Malo joined the team of the Fundación Pedro Meyer, where he directs the Archives and Technology departments.

Alejandro Malo (Mexico, 1972). Lives and works in Mexico and is the director of ZoneZero. Since 1993, he has taken part in various cultural projects and worked as an information technology consultant. He has collaborated in print and electronic publications, and given workshops and conferences on literature, creative writing, storytelling and technology. In 2009, Malo joined the team of the Fundación Pedro Meyer, where he directs the Archives and Technology departments.[id] => 331 [language] => en-GB [catid] => 63 [jcfields] => Array ( ) ) 1

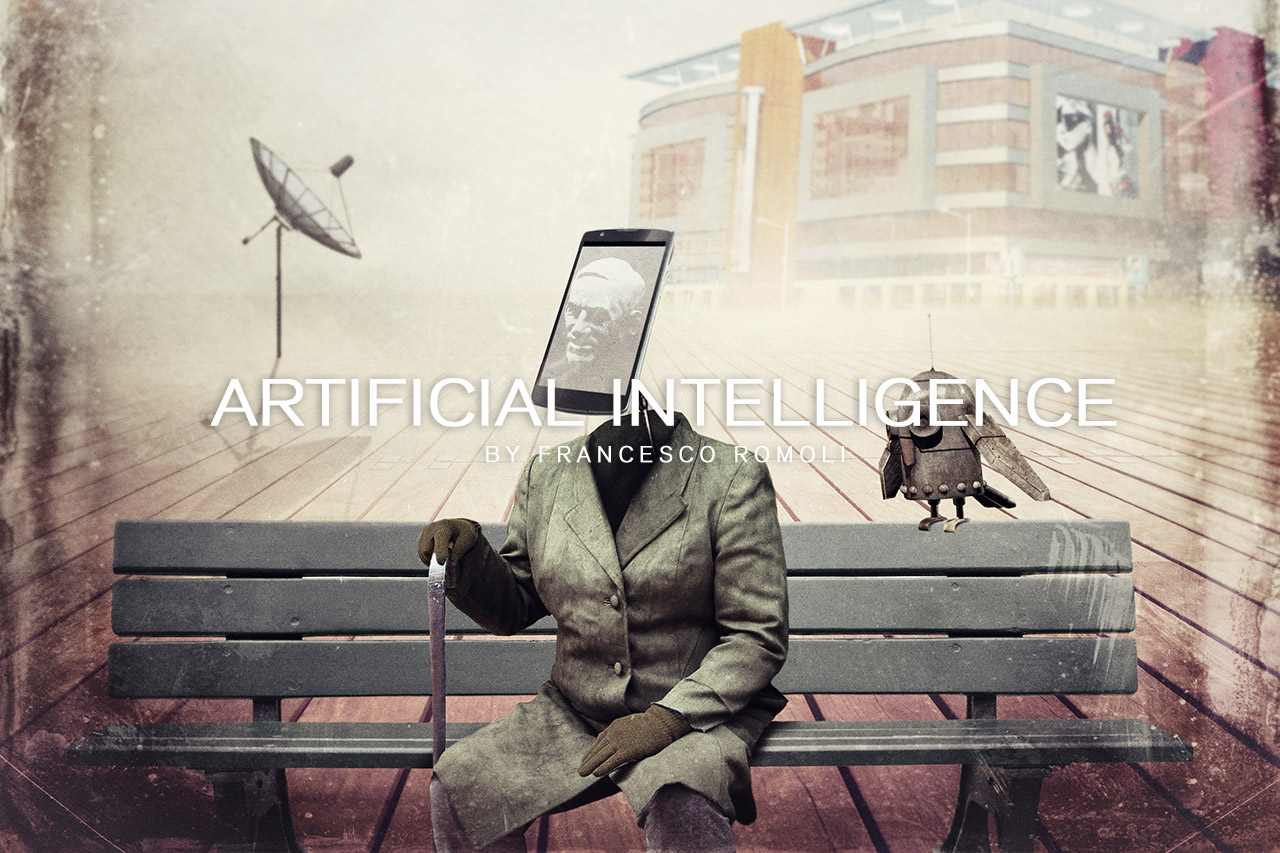

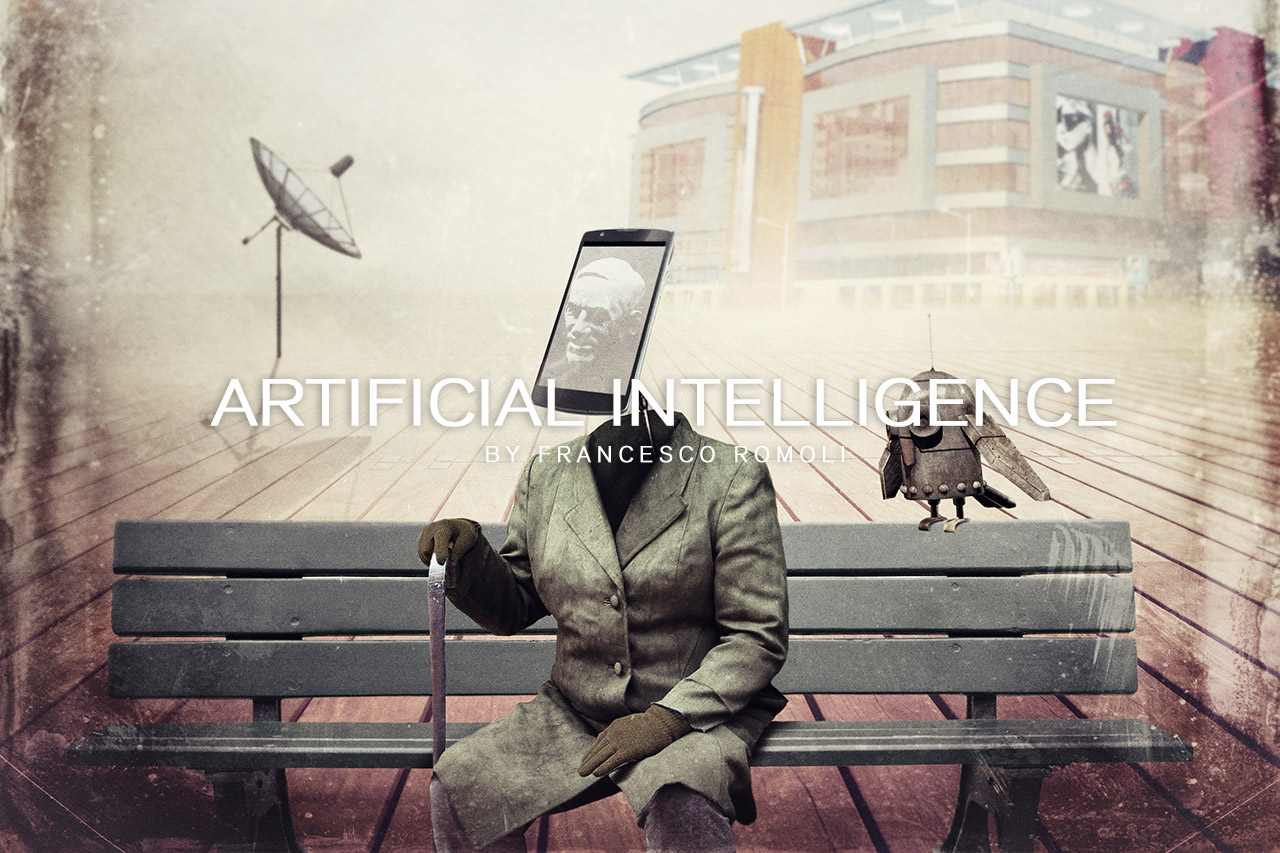

Francesco Romoli

After a period of decline comes the turning point.

The intense light that had been driven away returns.

There is movement, but not caused by violence... The movement is natural, developing spontaneously.

Thus, transformation of the old becomes easy.

The old is discarded and replaced with the new.

Both actions are in keeping with the time; thereby causing no damage.

Francesco Romoli (Pisa, Italy 1977). Always interested in expressive forms of any type at age 14 he began to study guitar and music theory. He falls in love in computers in 1998 and started to work on hacking and net-art. He graduated in 2004 in Pisa in computer science. In 2010 begins to use photoshop for his creations, halfway between graphic design and photography. In 2012 he began studying at the center of contemporary photography Fondazione Studio Marangoni, Florence. His other passions include skydiving and travel.

Francesco Romoli (Pisa, Italy 1977). Always interested in expressive forms of any type at age 14 he began to study guitar and music theory. He falls in love in computers in 1998 and started to work on hacking and net-art. He graduated in 2004 in Pisa in computer science. In 2010 begins to use photoshop for his creations, halfway between graphic design and photography. In 2012 he began studying at the center of contemporary photography Fondazione Studio Marangoni, Florence. His other passions include skydiving and travel.

After a period of decline comes the turning point.

The intense light that had been driven away returns.

There is movement, but not caused by violence... The movement is natural, developing spontaneously.

Thus, transformation of the old becomes easy.

The old is discarded and replaced with the new.

Both actions are in keeping with the time; thereby causing no damage.

Francesco Romoli (Pisa, Italy 1977). Always interested in expressive forms of any type at age 14 he began to study guitar and music theory. He falls in love in computers in 1998 and started to work on hacking and net-art. He graduated in 2004 in Pisa in computer science. In 2010 begins to use photoshop for his creations, halfway between graphic design and photography. In 2012 he began studying at the center of contemporary photography Fondazione Studio Marangoni, Florence. His other passions include skydiving and travel.

Francesco Romoli (Pisa, Italy 1977). Always interested in expressive forms of any type at age 14 he began to study guitar and music theory. He falls in love in computers in 1998 and started to work on hacking and net-art. He graduated in 2004 in Pisa in computer science. In 2010 begins to use photoshop for his creations, halfway between graphic design and photography. In 2012 he began studying at the center of contemporary photography Fondazione Studio Marangoni, Florence. His other passions include skydiving and travel.Jacques Pugin

Where are we?

Night… luminous traces, maybe celestial vaults, an oniric world full of mystery.