Mr. Keller, who organized the 1997 show in Switzerland, recommends that "signatures on Keïta's prints should be checked against those signatures that are known to be authentic."

As for Mr. Kelly, he said he "would never buy a Keïta photograph that was produced by Magnin and Pigozzi." He added, "You don't know how many are out there, you don't know if Keïta authorized the prints and you can't be sure of the signature."

At the coming exhibition, the largest photographs (60 by 48 inches) will be offered in limited editions of three for $18,000 to $22,000, not much above the price at Gagosian eight years ago. Over the same period, some other celebrated photographers' work has quadrupled in price.

But for all the controversy that now surrounds Mr. Keïta, Mr. Kelly seems surprised that there hasn't been more. "If you take this story and substitute the name of Bresson for Keïta, the world would be in an uproar," he said. "So far few have paid attention."

There are many reasons why posterity might regard Cartier-Bresson and Mr. Keïta differently: Cartier-Bresson was white, French and received important European commissions early in his career, whereas Mr. Keïta was a self-taught black African of modest ambitions for whom photography was, most of all, a job. Still, Brian Wallis, the director of exhibitions and chief curator of the International Center of Photography, describes the issue of what to do with new prints from the negatives of any deceased photographer as "one of the most vexing in photography." Sandra Phillips, senior curator of photography at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, pointed out that earlier photographers barely noticed how their work was printed. "It was the image, not the print, that was all important," she said. "Photographers would literally drop their negatives off at magazines or museums and let the editors and curators decide how the photographs were to be developed."

Julia Scully, the former editor of Modern Photography, said that "the idea that the vintage or limited-edition print is of special value has been promoted by collectors and gallery owners, who, having witnessed the recent increase in the market value of photography, seek to protect their investments. When it comes to photography, authenticity is artificial."

As a photograph (or any other work of art) is separated in time from the cultural context in which it originated, the work becomes open to new meanings. This idea, perhaps first articulated in Walter Benjamin's landmark 1931 essay, "The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction," has been embraced by many curators in recent years, leading them away from what Mr. Wallis refers to as the "fetish for the vintage." Instead curators are more open to the new meanings that may emerge from manipulating the originals, even if those meanings are different from - or in direct contrast to - anything the artist had in mind.

The result is ripe with possibilities, but also with contradictions. It is now not uncommon for galleries to put on shows that reflect this postmodern approach but at the same time to charge higher prices for original works.

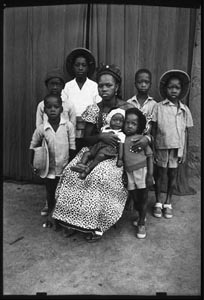

In the case of Mr. Keïta, the original photographs were taken at a significant moment in West African history, amid a great migration from rural to urban areas. His customers, said Mr. Enwezor, were part of that shift: newly arrived in the city, they would mail photographs to relatives who were still in the countryside. The prints were a type of private correspondence. As the formal elements of the photograph - its dimensions, its contrasts and densities - are manipulated, this history of the image, as contained within the photograph, begins to evaporate.

There is, though, another argument, based in the technology of photography, that undermines the concept of photographic authenticity. Charles Griffin, who prints the photographs of Cindy Sherman and Hiroshi Sugimoto, observes that the resolution of photographic negatives is far greater than that of the prints made from them. The negatives, you might say, contain a far greater amount of information than can be shown, placing those who make prints in the position of having to select and suppress the information that will ultimately appear.

And the printer's responsibility in this regard, Mr. Griffin added, has been heightened by the decision of paper companies to reduce the silver content in, and therefore the sensitivity of, photographic papers.

As a result, artists, museums and galleries treat printers in the same way that writers treat good editors, trusting them to add and subtract material from a manuscript to achieve the best result. It was to Mr. Griffin that Mr. Kelly turned when he took over the representation of Seydou Keïta. Because of the respect that the dealer and the association have for Mr. Griffin's work, they have given him great license over the way in which Mr. Keïta's photographs are printed.

Mr. Griffin said that when he attended the 1997 exhibition at the Gagosian Gallery, he was immediately disturbed by a number of factors, especially the extent of the contrast between the blacks and the whites. "Too often," he says, "printers are influenced by the preference wealthy collectors have for highly graphic images." When he was asked later to make prints from Mr. Keïta's negatives, he made a number of important changes, including the decision to "give more emphasis to the ground between the blacks and whites." He has yet to see a vintage photograph of Mr. Keïta's.

Mr. Griffin's observation about the influence of collectors contains a paradox: however much scholars talk about alternative modes of interpretation, the dominant force in the current market is one which makes many re-interpretations look a great deal like the cover of Cosmopolitan - a result that is probably not what Walter Benjamin had in mind.

In the end, the debate over how to make prints from Mr. Keïta's negatives may soon be academic. As a result of the litigation to recover the 921 negatives from Mr. Magnin and Mr. Pigozzi, the association has little money left to preserve those negatives that are in its possession - negatives which, according to Mr. Griffin, are quickly deteriorating. In the end, the controversial prints may be all that is left of Seydou Keïta. And at that point, the postmodern will have become the authentic.

Michael Rips

| Michael Rips is the author of two books,"The Face of a Naked Lady: An Omaha Family Mystery,"and "Pasquale's Nose: Idle Days in an Italian Town". |

|---|

© New York Times

January 22, 2006