related article about The Japan's Best Sellers

|

by Aventurina King

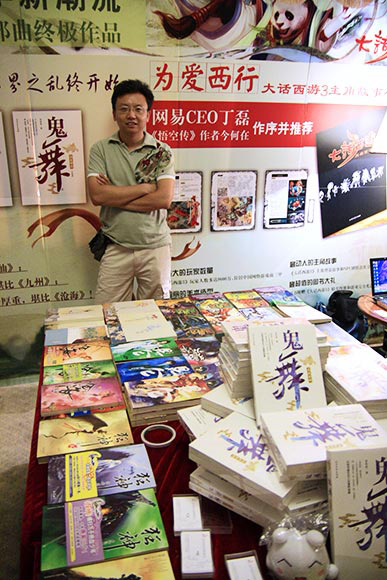

Magic Sword's CEO, Kong Yi, stands behind an unreleased batch of internet novels. Photo: Aventurina King |

Zhang

Muye is a thirty-something office worker who shows up to his

Chinese investment company on time. Yet to millions of Chinese fans,

he is the author of "Ghost Blows Out the Light",

an internet novel viewed more than 6 million times online. It

has sold 600,000 copies in print.

"It's only when I am at work that I can write; when I'm at home,

I can't," says Zhang. His novel, which narrates the travails of

a gravedigger plagued by ghosts, has been acclaimed across China for

its creativity, if not for its critical value. Zhang began writing Ghost

to relax and kill time during slow mornings at his office. "I don't

think of it as literature," Zhang says. "For me it's just

a game."

It's a particularly lucrative game. Zhang is far from unique in China,

where writing and reading novels online has become the hobby of an estimated

10 million youth. Yet unlike the music world, where MP3s are threatening

to kill off CDs, online novels in China are helping physical books fly

off the shelves. Print versions of popular online works sell by the

millions and publishers, as well as authors, are cashing in.

"Novel", the top search term on China's biggest search engine,

Baidu, yields thousands of Chinese literature websites. More than 100,000

amateurs shirk mundane duties to publish their tales of fantasy and

love in installments on these platforms. A handful of anonymous web

authors have seen their pageviews soar into the upper seven digits.

When that happens, print publishers come knocking.

And it's not just print. Companies from almost every entertainment

field, including films and video games, are joining forces, heralding

the next generation of Chinese entertainment empires. The creative

content of one internet novel can be sold to various national entertainment

companies up to five times. A film version of "Ghost Blows

Out the Light" is in

pre-production and many popular internet novels have spawned TV series

and online games.

"The multi-dimensional utilization of copyright in China has just

begun", says Kong Yi, the CEO of Magic Sword, a literary website

whose hit series, Killing Immortals, has sold over a million copies.

Yi and a few friends first hoisted Magic Sword onto the web in 2001

as a literary hobby, using a few shaky borrowed servers. By 2002, it

was ranked in the top 100 websites worldwide on Alexa.com. The borrowed

servers threatened to keel over under the weight of the traffic.

In 2003, Magic Sword became a commercial endeavor. It raised $10,000

from investors, got new servers and finally became its creators' day

job. Then the leading Chinese portal Tom.com bought Magic Sword, making

Yi a millionaire. Magic Sword now has its own halogen-lit offices in

a sprawling forest of glassed buildings just outside Beijing.

Magic Sword is now losing a few thousand dollars every year. Confident

of future success, Kong Yi compensates for this loss with the money

from the acquisition by Tom.com, supplemented by income from ads, fees

paid by readers and a string of copyright sales. (As with other Chinese

literature sites, anyone can publish stories and most of the content

is free, but there is a fee to read the most popular novels.)

Yi's ambitions don't stop there. "I would like to make the company

into an entertainment corporation, one that would include a publishing,

movie production and video game company", with internet novels

at its nucleus, Kong Yi says.

In a virtual world where a company's profit rests on easily reproducible

text, the scramble for control over creative content is fierce. Copy

protection is almost irrelevant: No matter what technology protects an

online novel, pirates looking to siphon traffic to their own site will

simply type the content into another document and upload it.

To keep afloat, companies indulge in their share of borderline activities. One regular task of novel website employees is stealing the authors and the staff of other novel websites, according to an industry insider. Last year, Magic Sword sued website Source of Chinese for posting a free link to Killing Immortals. In an interview, the defendant denied knowing at the time that it was infringing copyright. The court case was settled privately.

The website Source of Chinese is the online platform for the success of Zhang's Ghost Blows Out the Light. It is known within the Chinese publishing industry for its financial muscle and commercial aggressiveness, and commands 80 percent of the market, with more than 80,000 authors, according to Luo Li, the company's business and publishing manager.

Seated before a venti-size Starbucks coffee cup in Shanghai's shiny and bustling Ruggles Mall, Li laid out the workings of his company's success.

From the thousands of novel blogs on Source of Chinese, the site's editors select a few that are good enough to sell in the VIP section.

In the print world, book length is limited by the cost of paper, printing and distribution. On the internet, where production costs are close to zero, length equals profit. VIP readers pay a couple of cents for every thousand characters (a print novel generally has 250,000 characters). Contracted authors are paid seven to 12 dollars per thousand characters, depending on their clout. Zhang Muye gets 12 dollars per thousand.

"Some writers can write 20,000 to 30,000 characters (20 to 30 A4-size pages) in two to three hours per day," says Li. "In three months, if they go fast, they can write more than a million characters. The model is very simple: The more you write, the more money you make."

Consequently, more and more internet authors now prefer web to print publishing. To promote sales, publishing companies often require the author to keep a novel's ending exclusive to its print version. In the past, this had resulted in the online organized demonstrations of angry readers who felt cheated into spending money on the print version. Now, according to Li, the web gives online authors enough confidence and financial support to refuse print-exclusive endings.

Within China's communist dictatorship, this gradual slide of the publishing and entertainment industries toward the web clearly carries political implications. The internet offers a boundless space, relatively sheltered from the rigid control of government censors. The question is whether this degree of expressive freedom will penetrate into the real world.

For the moment, it seems not. Owing to the official ban on superstition, before Ghost Blows Out the Light could be sold in print, Zhang had to go back and erase every single appearance of a supernatural being in his novel.

October,

2007