|

‘DIURNES’: WORKING NOTES

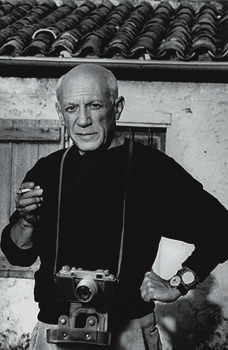

In Paris in June 1994 Picasso photographe 1901-1916, (1) the first in a series of three exhibitions in which the Musée Picasso explored the relationship of the artist with photography, was presented. Picasso emerged as a prolific amateur documenting his own studio and the still lifes that served him there as a model. The images selected for that show provided interesting information about his way of working, but did not give evidence of any particular ambition to express himself through photography. It was probably much later, through his friendship with Brassaï and his intimate relationship with Dora Maar (1936-1945), that Picasso began to take photography more seriously as a creative medium. His most ambitious photographic project was, without doubt, the series of lithographs entitled Diurnes (1962), created in collaboration with the French photographer André Villiers.(2) Villiers and Picasso had known each other for some time. Captivated by Provence, where both of them resided, they decided to create a work together based on sticking cutouts of a typically Picassian fauna and mythology onto landscapes and natural elements photographed by Villiers. This involved, then, combining photograms and conventional photo prints. Photographer and painter shut themselves away in the darkroom Villiers had set up in Lou Blauduc, a superb rented country mansion between Mas Thibert and Salin-de-Giraud in the middle of the Camargue. The herds of horses and fighting bulls that were grazing freely in the countryside around probably inspired many of the compositions. “Diurnes, in short, has all the experimental force of the visual risk-taking of the Surrealists and at the same time the poetic charge of the Mediterranean sensibility, the exaltation of the founts of its aesthetic memory, the magic of its most visionary origins. It’s like the meeting of a shepherd and a mermaid on the trunk of a Buick considered as a readymade” Professor Rosalynd Kroll has wisely written.(3) In Lou Blauduc the two artists produced upwards of fifty originals, thirty of which they chose for the edition of lithographs. Of the rejected prints nothing more was known. It was a great surprise when the art critic of La Dépêche du Midi and professor at the University of Aix-en-Provence, Jean-Pierre d’Alcyr, salvaged the forgotten images. After managing to get the current proprietors of Lou Blauduc to allow him to rummage around in the attic, d’Alcyr found various laboratory utensils, two packets of Agfa photo paper and a third packet of Mimosa photo paper. These packets contained the prints that were never utilized. Many prints are stained or inadequately fixed: others are slightly different versions of those finally chosen. Taken together, however, they allow us to analyse Diurnes from another angle, one that reveals not only the finished results but also the whole work process, the successive phases of selection, the doubts of the two artists, their final agreement.

1.

1. BALDESSARI, Anne: Picasso photographie, 1901-1916, París:

Musée National Picasso, 1994. |